Elizabeth Adams's Blog, page 26

May 18, 2019

A Sketchbook as Bulwark Against the World

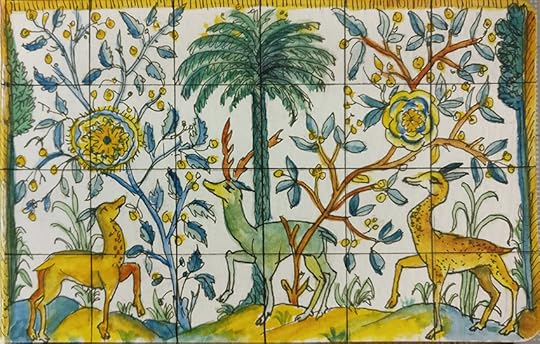

Altar frontal, polychromed faience, 1600-1650, from the Museu de Azulejos in Lisbon

I've kept working on my Lisbon sketchbook. Slowly, I'm realizing that a finished sketchbook like this is an object in itself, but also that the sketches could form the basis for some sort of expanded "book" of words plus art. I have five more pages to go, and then I'll lay it aside for a while and see what it says when I come back to it in a month or two.

What I do see, for sure, is that this has been a centering, grounding project during the cold, late spring, amid so much disheartening news. As I've said here before, my primary path and central mission is to be true to myself, which means doing my level best to be a positive and loving person who keeps creating, and encouraging others to do likewise. There is no better way to counter the destructive negativity of the current political world than to allow creativity and love to flow through ourselves and outward. Yes, it's difficult. Yes it requires digging deep inside ourselves and finding resources we perhaps didn't realize we had. Human life has always included both the worst of times as well as the best of times. We're facing huge challenges, and we each need to do our part, but in order to be effective and resilient, we have to find and embody the light wherever we can, as individuals with our own particular paths and relationships and passions.

Dunes in bloom, and cactus, on the national seashore reserve west of Cascais, Portugal.

I was in the U.S. last weekend for the 50th reunion of Dartmouth students who protested the Vietnam War, occupied the college administration building in 1969, and served prison terms as a result. My husband was not one of those jailed, but he was a close and supportive friend who documented that event and that time period photographically, and was invited to give a slide talk as part of the reunion. During the panel discussions and social times, I learned that nearly all of the fifty-some attendees were people who have spent their lives doing good, being creative, living with others in mind, working for the betterment of society -- and are continuing to do that in spite of the prevailing climate of hate and negativity. I was impressed, proud to be part of the gathering, and often very moved.

As one of them said, "we won some fights and we lost some, but 'success' is not the only measure of whether things are worth doing." And one of the current student activists said to these aging radicals with grey hair and achy joints: "It's not over 'til it's over -- you're still here, and we need you."

There's so much work that needs to be done -- on the climate, on rights for women and minorities, on freedom and justice, against hate speech and white supremacy -- the list is exhaustingly long. None of us can do everything, so just pick one thing, and work on it a little every day, wholeheartedly. Join a group of like-minded others; we can all accomplish more collectively. But do something real - don't just talk or, worse yet, add to the endless complaints on social media. And please, if you're a writer or artist or musician, keep doing your work. In a climate like today that attempts to suck the lifeblood out of creative people, and devalue who we are and what we do, making art can be a radical act. I certainly feel that way about publishing books, and about singing.

In the woods yesterday with friends.

Nobody can be an activist, or in a position of helping and giving, 100% of the time. For me, the other side of the coin of action is contemplation. If I refuse to be defeated or silenced or worn down into depression and paralysis by the negative forces, then I need to find ways to continue to live fully, engage with the world, and to do my work, in spite of everything else. Each of us has a well to go to, when we need to re-center -- maybe it's the woods; a meditation cushion or a church; walking our dog in the park; reading; journaling; or spending time dancing or at a musical keyboard -- whatever it is for us, we need to find that place, know it well, and go there regularly for strength and consolation, not escape.

Can a 3 1/2" x 5" sketchbook, then, be a bulwark against the dark forces of the world? Actually, I'm finding out, it can.

April 30, 2019

Lisbon Travel Journal: A Process and a Search

The Logistics

I went off to Portugal with a new, blank, pocket-size watercolor sketchbook, and the intention of doing as much sketching as I could -- more, I hoped, than I had ever done on a trip. That's what happened -- but, as usual, things got complicated. We planned an itinerary each day, and were on the go most of the time. J. and I walked a lot and for the most part we were always together. This is my choice, even though it conflicts with drawing. Lisbon is beautiful, with many exciting and challenging views, plazas and monuments, and complex perspectives. Still, I found that I didn't want to take too many precious hours out of the day to sit and draw. And when I'm traveling with someone else, it's not fair to ask them to be patient for an hour or more while I sit bent over a sketchbook. My partner -- a photographer -- is really very understanding about this, but we both try not to impose on each other's good nature too much. I sketched before or after some meals in restaurants or cafes, and occasionally at a church or a miradouro -- one of the many "lookouts" scattered at high points around the city. I also did some still life and interior drawings in our apartment in the larger sketchbook I'd brought. Sometimes I did a quick sketch in pen-and-ink on location, and added watercolor in the evening after we were home for the night. But all of this still barely scratched the surface of what could have been recorded in my sketchbook.

After we returned home to Montreal, three weeks ago, I plunged into choir duties for Holy Week and Easter, plus we had a big professional design job to finish up by the end of the month. The sketchbook kept calling to me, though, and when my friend Valeria Brancaforte, a printmaker and painter in Barcelona, suggested that I just use my photographs and my memory to fill out the pages, it was the encouragement I needed. I've tried to do one new drawing every day or two.

The Project

What started as a fairly amorphous idea -- a bunch of random sketches and impressions of a particular place -- became even less clear to me during this trip.

Whenever I've traveled as an adult, throughout the past forty years, I've generally kept some sort of journal. Originally, before computers and long before phones, these journals were mostly words in a small notebook, maybe with a sketch or two. I took pictures with film cameras, and made albums of prints when I got home. Later, this same journalistic process evolved into blog posts. After we moved to Montreal and established a much more functional studio space, my blog -- which had been mostly words and photographs -- became more of an art blog, and I started drawing nearly every day. When I traveled, I still took along notebooks or sketchbooks, but the words went into my computer. Although I was drawing while away, I never tried to make a sketchbook that stood on its own. The sketches, along with words, ended up on my blog.

View of the Targus River and Castelo de Sao Jorge

During these same years, in the craft world, scrapbooking became a thing, while artists took it one step farther, making personal journals that combined elements of scrapbooks, sketching, and handwritten journaling, and teaching others to do it. Online, we saw the rise of the wildly popular urban sketching movement, with talented artists holding international seminars on techniques for drawing architecture, urban landscapes, and people. Local groups of avid sketchers have sprung up in many cities. These travel and urban journals are personal too, often combining words and paper ephemera along with pen-and-ink or watercolor sketches. People share their work not only in local groups but on personal and group blogs, and social media.

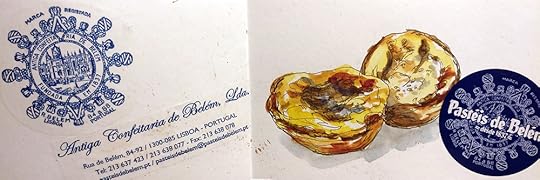

Natas (Portuguese custard tarts) in pen-and-ink and watercolor, with stickers and packaging from Pasteis de Belém.

All of this is fantastic, I think -- it's brought new methods of creative self-expression, as well as community, to a great many people. I've certainly been influenced by some of these trends, and they've found expression on my blog, but until I decided to make one cohesive paper journal of this trip, I hadn't thought it through. What exactly was I trying to do? What was this thing I was making?

The Targus River from the Alfama (the old Moorish quarter)

The drawings in my large sketchbook were not confusing: they were black-and-white line drawings done in my familiar style. I had made a somewhat subconscious decision to do the small pocket sketchbook pages entirely in color. But in what style? Good question! The answer that emerged was that I didn't have one -- at least, no style I was completely happy with. Most of the first pages were done with pen-and-ink, followed by watercolor washes. Sometimes the line felt too heavy for the small pages, giving a cartoon-like feeling. At other times, when I managed to stay looser, the result was more pleasing to me. I thought I'd try working in direct watercolor, over a lightly sketched pencil drawing. I did the two landscape sketches (above) over the rooftops looking toward the Lisbon harbor, as a comparison. Both were nice: they're just very different in feeling and even in purpose.

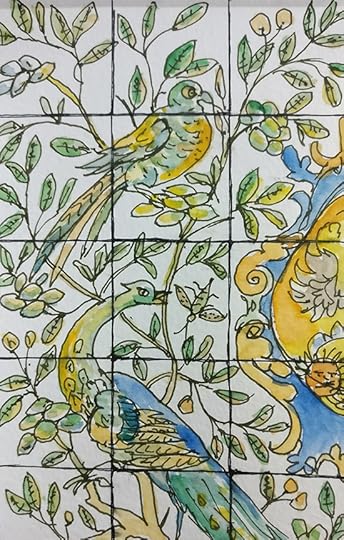

When drawing tiles or ceramics, using line work made a lot of sense, and seemed effective. For sculpture or landscape, I wasn't so sure. I kept going back and forth between the two.

Madonna and Child at Igresa de São Domingos

Halfway through the trip I decided that this was the real purpose of the project: to explore and search out a style that I liked, or perhaps to refine two different styles for different purposes.

I did two full-spread seascapes using watercolor alone, and began to feel a little more satisfied. Both were too contrasty, and I struggled with the Moleskine paper, which is really not very high quality, but they had more feeling, depth, and emotion than ones that began with a pen line. Was it ridiculous, I wondered, to spend so much time on an 11" x 3.5" sketch, when I could have worked much larger on excellent paper, and gotten a much better result?

Calçada do Combro, with tram lines overhead.

Then there was the problem of perspective. For years I avoided drawing buildings, even though I've studied perspective and know the basic rules -- I thought it bored me, but really I lacked the necessary patience. Doing complicated urban drawings of buildings and rooftops, which I'd first tried last year in Mexico City, gave me more confidence. In Lisbon, with its hills and endless angles, I tried to pay more attention, and take the time to get the drawing approximately right, but I was also learning how much to leave in and what to leave out to create an evocative impression and satisfying sketch rather than an architectural rendering.

In spite of all my second-guesses and self-criticism, the sketchbook itself was beginning to fill out, the pages adding up to a record and impression of what I had seen. I didn't have this from any other trip we had taken. So I kept going, determined to finish a standalone, completed book, rather than abandoning it mid-stream. Some pages would just work better than others; that was fine with me. It could contain a variety of styles. In the end, it would be a record of my own search and struggle, as much as it was a record of a place.

Dinner at the apartment: salad, fruit, and vinho verde.

A modern travel sketchbook can be so many things -- there are no rules. The most satisfying ones, to me, have a developed, personal style, but their "tone" varies just as much as we artists vary in personality; that's part of what makes them so cool and interesting. Some are detailed and architecturally accurate, some much looser; some are whimsical and playful. Some focus on food, or buildings, or people; some use more or less color or pen line; some incorporate a lot of ephemera. In the end, it's all up to the maker.

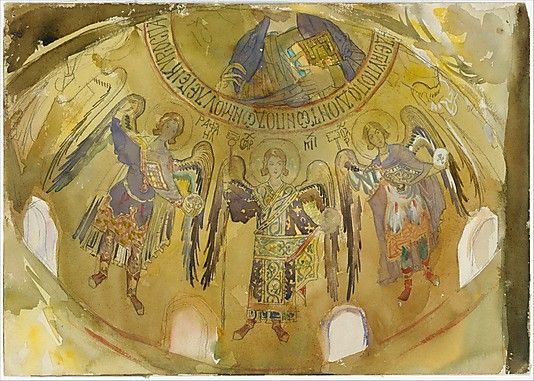

John Singer Sargent, Ceiling of Palatine Chapel, Palermo, Sicily, watercolor, 1897

But what did I most want to do? A few days ago, I spent some time in the library looking at some John Singer Sargent watercolors I hadn't seen before, including his travel sketches from Sicily. Back in 1897, he had sketched altar retablos, wall mosaics and pavements that I too had admired and photographed 120 years later. I felt a flash of connection and recognition, as well as gratitude, as I pored over his masterpieces. Each sketch, no matter how loose or unfinished, was worthy of framing. They confirmed my gut-level instinct: I was most interested in trying to follow in the footsteps of artists like Sargent -- whether that took the form of a book of paintings and drawings, perhaps to use later with words, or loose sheets intended as standalone paintings, or sketches that could form the basis for later paintings.

This, on balance, is the most important thing the process has showed me: that at least part of the time, I want to aim high and do something more serious, partly because I feel the press of years: I don't have unlimited time.

Like anything worth doing, drawing and painting require discipline and practice, and also passion. I really love to draw, and always have. Developing a lively pen-and-ink style, with or without color, has been a priority for me, and it's fun. Likewise, direct watercolor is a medium I love, even though it's technically difficult, and very easy to ruin. Better paper is a requirement. In the future, maybe I'll end up binding sketchbooks for myself to use, with the paper I like best -- I can guarantee that the traveling artists of the 1800s and early 1900s were not using cheap sketchbooks. I need to take my own advice, and use the best materials I can afford.

I was happy with the first direct watercolor I did after revisiting Sargent's. It took twenty pages to get to this point; I've got another ten to fill.

April 29, 2019

Comment Question

Have any readers had trouble commenting here, such as writing a comment and then the comment not showing up? I would appreciate it if you could send me an email at cassandra (dot) pages (at) gmail (dot) com if this happens, telling me what happened and which browser you're using. Thanks.

April 20, 2019

Why is 3-D Compassion So Hard?

Pieta, Igresa de Sao Domingos, Lisbon.

Holy Week has coincided this year with the fire at Notre-Dame, and the resulting debate about what the billionaires and governments of the world should be supporting. Each day, I've read the arguments on social media and op-ed pages. Every night, I've gone to the Anglican cathedral where I sing, put on my red cassock and white surplice, and participated in ancient liturgies that commemorate a great miscarriage of justice 2,000 years ago, when the powers of religious establishment and the government of the time came together to crush the leader of a movement whose teaching was based on entirely different values, and different authority. Thursday was the observation of the Passover supper when Jesus established the practice of the Eucharist, knowing he would die soon; on this night he told his followers that he was giving them a new commandment, more important than all the Jewish laws: "Love one another as I have loved you." If you do this, he said, I will know that you are my disciples. Sitting in a dark church hearing those words, it's impossible not to feel like an utter failure -- as his disciples often were, too. Loving was not enough to save Jesus from death. And yet, trying (and failing, and trying again) to keep that simple commandment has been enough to form the basis of my entire life, and many other people's lives. Lent is an annual time to think about this more intentionally, and Holy Week is its culmination. These seasons of penitence are not about guilt; they're about Love: seeing what blocks us from loving better, and committing to a renewed sense of love for all people, and for the world in all of its failings and ugliness, and its beauty and miraculous joys.

The gasps of genuine shock and dismay that accompanied our first awareness that an 800-year-old medieval cathedral was burning were shortly followed by self-serving comments by French politicians, hoping to use it as a unifying point in a society fragmented by racism and division. Hatred of the Catholic Church came next; many people didn't realize (or take the time to find out) that the French state owns Notre Dame, not the Catholic Church or the Vatican. Then, when French billionaires came forward with enormous pledges for the reconstruction, social media really heated up. In the UK, there were cries of "Where were the billionaires when Grenfell Tower burned?" In the US, it was "Where were they when the black churches burned?" We were admonished for not caring enough about Yemen, or Aleppo. Internationally, pictures were posted of dead coral reefs, with the poignant and appropriate caption "Rebuild this Cathedral!"

Every one of these reactions is understandable and, to my mind, worthy. What bothers me is that we don't seem able to hold them all together, without shaming those who expressed sadness at the loss of irreplaceable architecture and art. As my friend Dick Jones said, "We don't seem capable of 3-D compassion." The reaction to the Notre Dame fire was only one example of this phenomenon.

When I lived in Vermont, for many years I was part of a grassroots activist group working to revitalize our poor neighborhood. Early on, we went door-to-door canvassing the residents, most of whom lived in run-down rental apartments. When we asked them what should be our priorities, they named things like better sidewalks, playgrounds, streetlights and safety, but the overwhelming consensus was on the need for beauty: they wanted trees and flowers, places to sit and see something other than the pavement and poverty that created a sense of shame and isolation. And they wanted to know their neighbors; they wanted a sense of community. It took time, and some grants from the local government and the state to accomplish some of those things, but building community and creating a more beautiful environment began immediately, from within ourselves and our own resources, not from outside. It is not either/or. Human beings need dignity and respect, they need decent housing, food and work, they need education and equal opportunity for their children, clean water, and health care. We also have an innate desire for beauty, whether it is found in nature, or in the arts. Somehow, we have to find a balance where we can hold all these human needs together, and have compassion and zeal whenever they are threatened or destroyed.

We are living in depressing and frustrating times, surrounded by increasing economic inequality and government inaction on the most pressing issues that affect all of humanity, such as climate change and the health of the oceans -- and nothing that we do to demand change seems to have an effect; the forces arrayed against the common people seem overwhelming, just as they did 2,000 years ago. So it's not at all surprising that people's anger is directed at powerful institutions, like the Catholic Church, or wealthy individuals who choose to give their money to a high-profile cause. These outbursts of frustration point out conflicts of priorities, but they also fail to acknowledge the many philanthropic individuals and small and large organizations who are already working tirelessly and often almost anonymously to support the environment, scientific and medical research, racial and ethnic inequality, the arts and education, and many other causes.

More than that, though, I am concerned about the division created among good people through the tactic of shaming. The Left is particularly susceptible to this, and it's incredibly destructive. Ironically, the same people who totally get "Black Lives Matter" and were outraged when conservatives countered with "Blue Lives Matter" or "All Lives Matter" are doing the exact same thing when they insist that their cause is more worthy, and others should be ashamed of their own feelings.

Shame never brings people together, or creates lasting change of heart. We are individuals; each of us is drawn to different aspects of life, and it's natural for us to put our emotions and energy there; these proclivities should be complementary, not competitive. Some of us are meant to be guardians of the arts, or of children, or the elderly, or nature, or of immigrants, or of animals, or of human history...the list is long, because human beings and human culture are varied and complex.

I come back to that neighborhood group. At our very first meeting, which happened after a shooting, a lot of anger was expressed at "the authorities." People blamed the schools, the police, the town government, and they clearly expected these outside institutions to step in and fix the problems. But as we talked more, we began to see that if we waited for that, we might wait forever: we had to start within our own community, with ourselves, and with what we had in common. We had to talk to each other, ask questions, express our hopes and fears, get to know each other's strengths and limitations, and work together. In other words, we needed to "love one another."

It's worth remembering, perhaps, that medieval cathedrals were not built by like modern-day skyscrapers by multi-national corporations, or even by wealthy centralized church institutions. They were built by people who came together to try to do something greater than themselves that lifted their spirits and short lives above the difficulties of feudal societies beset by plagues and wars that spared no one. Yes, wealthy donors gave money, and so did peasants, each according to their abilities, and all were able to see the progress and feel part of a great process that would extend well beyond their own lives. It still astounds us that these huge works of art were built essentially by hand, and have lasted through the centuries.

The point is not that a western cathedral is inherently more precious or worthy than art of any other part of the world, or more important than insuring the safety and well-being of the neediest among us, or rebuilding black churches, or caring for the oceans. It is that human beings can do astonishing things when they work together, and when we decide to make love of something greater than our own selves a priority. The question for each of us is where we want to put our energy, and how to care for one another during these difficult times so that we can actually work together for the common good.

April 15, 2019

Goodbye, Beloved Piano

The year is 2006; my friend Jon Appleton, composer and professor, and I are at his piano in Jon's former home in Vermont. These pictures were taken before my husband and I moved to Montreal and several years before Jon moved to Hawaii, taking his piano with him. Jon and I look quite a bit younger; the piano, of course, always looks just the same. It's an 1895 Steinway B, and is my favorite instrument among those I've had the pleasure of playing.

Jon loves to give dinner parties, and during those evenings back in Vermont he'd often sit at the piano and play for a while, before or after the meal. Sometimes it was serious, but there was always some goofing around too. If other musicians were present, which was often the case, he'd get them to play or sing something. That's where I met the master shakuhachi player Kojiro Umezaki, several Russian friends of Jon's, and many other people who came through town and stopped to visit their former teacher, friend and colleague -- Jon traveled widely, and had musical friends from all over the world.

My husband was a student at Dartmouth College around the time Jon first came there as a professor, so they knew each other, but our acquaintance deepened when we began doing design and advertising work in the 1980s for New England Digital, the developer and manufacturer of the Synclavier, one of most successful music synthesizers. The hardware and software geniuses behind the Synclavier were Sydney Alonso and Cameron Jones, and Jon was the musical adviser. These three were the founders of the company, but Jon didn't stay on as an active business partner -- instead he became a pioneer in electro-acoustic music, composing and performing on the Synclavier all over the world, and developing an influential electro-acoustic music program and state-of-the-art studio for study at Dartmouth. In the summers, New England Digital hosted a summer seminar for users, with technical workshops by the company staff, and concerts and lectures at Dartmouth given by invited guests and Synclavier users such as Lorrie Anderson, Pat Metheny, Oscar Peterson, and John McLaughlin. There was always a picnic at Jon's house where everyone could talk and mingle. Needless to say, it was an exciting time, and we were fortunate to have been involved in it.

I think it was after those years, and after New England Digital had gone out of business, when Jon and I really got to be close friends. in spite of the fact that his international reputation was based on his electro-acoustic compositions and recordings, Jon was a classically-trained pianist who had been a prodigy as a child, but suffered from stage fright and eventually gave it up in favor of composing. All the while he was doing the electronic music, he kept practicing piano for his own pleasure, and wrote compositions that he termed "neo-classical." As we began to know each other better, he learned that I was a serious amateur piano student, and we would talk about classical piano music, sharing favorite recordings and listening together. It was hard for him to get me to play, though, because I was very shy about it and, I'm sure, intimidated. I hated giving recitals and had always had trouble with nerves during solo performances -- my hands would shake and sweat. But Jon understood this, and he kept after me, in a gently encouraging way. For some reason, I also felt drawn to his beautiful piano, and rarely visited him without touching the keys, but seldom sat down to actually play.

The breakthrough was four-hand piano music. Jon loved playing four-hand pieces, and he had composed some marvelous works for his friends Julia and Galina Turkina, a famous Russian four-hand duo in Moscow. He gave me a couple of books of much-easier four-hand pieces and suggested that I learn one part, and we could try playing them together. I'd heard him play four-hand with other people, and I was secretly dying to try it, so I dutifully took the scores home and practiced, and the next time I was up at his house -- not at a big party -- we played. It was such fun, I began to relax and enjoy it. Jon was, as always, very encouraging. "Don't worry about the mistakes!" he'd say. "You play really well! Just have fun!" Of course, nobody could be harder on themselves than he was -- he hated making mistakes! But over time, largely because of his help (I had a very good teacher but she wasn't nearly as kind or gentle as Jon) I gained confidence, and eventually I was able to play in front of other people, both four-hand pieces and on my own -- things like Brahms Intermezzi, Scarlatti sonatas, or Bach Partitas that I'd been working on in my lessons. Sometimes I brought my flute, and Jon would play the piano part. He loved Scarlatti's piano sonatas, and Bach, and we often played favorite passages for each other and talked about the technical difficulties. We worked hard on a suite of four four-hand pieces he had written called Quatre regards sur le Parc du Roy d'Espagne, and hoped to perform it as a farewell party Jon gave for us at his house when we moved to Montreal, but the birth of his grandson intervened. Eventually, I would produce three CDs of Jon's music through Phoenicia Publishing, including his Scarlatti and Couperin Doubles.

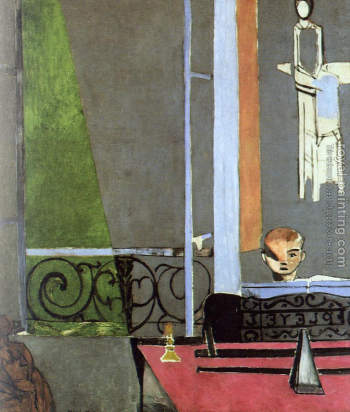

Almost all of Jon's neo-classical compositions were composed at his Steinway, and one of my great pleasures during those years was hearing the latest progress he'd made on a composition, and sometimes sitting down to play through parts of it myself -- that's what's going on in these pictures (all taken by my husband Jonathan Sa'adah.) The painting in the background is by Matt Bucy, and to the right in the upper pictures is a print by Matisse. I like how this third picture reminds me of Matisse's own "Piano Lesson," minus the rather ominous but universal figure of the teacher in the background!

I always loved playing that instrument. It had the rich, warm sound that older Steinways are known for, and a fairly light action that made it easier to play music like Scarlatti or Bach than on my own stiffer-actioned Schimmel upright; plus, it had personality -- it's a fine piece of woodworking, and always occupied a central place in Jon's home; it felt like a member of his family, to be greeted and touched and given its share of attention during any visit, to which it responded by helping to make beautiful music and nurture relationships between people.

A few days ago, Jon posted a video on FB in which he says goodbye to his beloved piano, which he is donating to his alma mater, Reed College. The movers were coming later to pick it up. Now in his 80s, and having had some health problems, he says he's not composing anymore, and soon he's moving from Hawaii back to a smaller apartment in Vermont. I read his news about the piano with bittersweet sadness. Because I witnessed the relationship he had with this instrument firsthand, I know how painful it must be for him to let it go, while I also know he's glad to have found a good home for it. I'm also a little wistful because it means I'll never play it again myself. So, along with Jon, I wish this beloved instrument a safe trip to its new home, and I hope many generations of Reed students will appreciate it and perhaps sense a little of the history and love that have been absorbed by those keys. As Jon says in his poignant video, "Goodbye, old friend."

April 8, 2019

Lisbon, Incomplete

Something about this picture embodies the last two weeks spent in that city better than all the tiled façades and wrought iron balconies and pastel loveliness, more than the hilly streets and clanging trams, and much more than the throngs of tourists eating their natas, and buying shoes and clothing from international fashion shops. Beneath all of that is a melancholy solitude that is difficult to glimpse or grasp, but seems as deeply embedded in the city's spirit as the two-inch chunks of black and cream stone, laid in geometric patterns, that pave the sidewalks and plazas: installed originally, I learned, by prison work crews.

The tradition of fado, and the now-overused Portuguese word saudade... these seem increasingly exploited as commercial expressions, losing meaning rather than being an entry into the soul of the place and the people. Saudade, which has no English equivalent, means a longing for an absent something or someone who may never return; saudade brings both happy and sad feelings, but it is more than nostalgia. It is described as "the state of mind that has subsequently become a 'Portuguese way of life'': a constant feeling of absence, the sadness of something that's missing, wistful longing for completeness or wholeness and the yearning for the return of what is now gone, a desire for presence as opposed to absence." Fernando Pessoa, the greatest of Lisbon's poets, wrote an unfinished work called The Book of Disquiet:

"The fragmentary, the incomplete is of the essence of Pessoa's spirit. The very kaleidoscope of voices within him, the breadth of his culture, the catholicity of his ironic sympathies – wonderfully echoed in Saramago's great novel about Ricardo Reis – inhibited the monumentalities, the self-satisfaction of completion. Hence the vast torso of Pessoa's Faust on which he laboured much of his life. Hence the fragmentary condition of The Book of Disquiet, which contains material that predates 1913 and which Pessoa left open-ended at his death. As Adorno famously said, the finished work is, in our times and climate of anguish, a lie." --George Steiner

So, I walked. Where do all those kilometers of pattern lead? I wondered. To the plazas, certainly, but then they wind out, up another hill, into a narrow maze of streets, curving out and down again to the edge of the sea, along the edges of buildings the color of marigolds, lavender, sky, up into the maze again. It is a city that leads the walker to walk, but toward what? Toward incompleteness itself, perhaps. The image at the top of this post shows the only conclusion I found: a place where the pattern changed into green growth and light, at the end of a small dark tunnel.

I also kept a journal with some drawings, which I'm still adding to; I'll probably share them here as time goes on. But I struggled with making art there. I had the sense that drawing and photographing were, to some extent, futile -- I left Lisbon feeling that it was impossible to capture its essence, because we cannot capture incompleteness, absence, and longing, even in the present age where the emphasis is on having a "complete experience", of checking items off a list, taking selfies at the proscribed spots to prove we were there. The Time Out Market, a concept that was first tried in Lisbon, is a perfect example: the tourist doesn't need to discover anything for him or herself; they can just go to a centrally-located and packaged "destination market" -- an upscale food court where a curated selection of restaurants and shops have stalls with the same signage, the same style, offering a sample of their wares, with long tables for seating in the center of the space. It's enticing and exciting on the first visit; on the second, not quite so much. All major cities will soon have these markets, and they will all look alike, too.

Better then, perhaps, to write in fragments, like Pessoa, or to express feelings in music, or simply to reflect on experience in solitude. Even as a brief visitor, I sensed Lisbon's elusive, melancholic undercurrent, and I find I'm appreciating it even more now that I am home.

March 19, 2019

Fitting It In

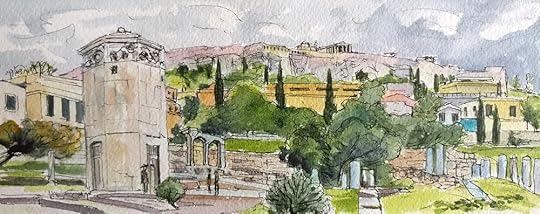

The Tower of the Winds, Athens, the Roman Agora. Watercolor and fountain pen, 9" x 4".

We've been super-busy lately, with a large professional design job that came to us unexpectedly, an upcoming book for Phoenicia, taxes, and various other personal and volunteer responsibilities. I've also had some more dental surgery, oh joy. I've felt like I haven't had any sustained time to do artwork, but in spite of that, I've managed to fit in a few drawings or other projects. It's important to my sanity to keep a creative practice going, so I'm glad to see the evidence when I look back through my photos from the past couple of weeks.

The drawing above was a test of a landscape-format Arches watercolor block, done one evening from photographs I took in Athens. We're going to be taking another trip soon, and I've been trying to get my art supplies together. I still don't have the ideal travel sketchbook; my hardcover Stillman&Birns is just too heavy to carry around in a purse all day, and the smaller sketchbook is a bit too small for serious sketching. So that's a dilemma to solve in the future.

Paints are easier. Here's a sketchbook sketch of my current palette, with some ideas for changes. In the end, I couldn't buy a small tube of perylene maroon locally, but was happy with the mixtures I was able to achieve from my basic palette of colors. All I'm doing is swapping out the Cadmium red for Quinacridone Burnt Orange -- a very beautiful intense burnt sienna that is full of light on its own but different from Quinacridone Gold, and forms lovely darks when mixed with deep blues. (Thanks to Liz Steel, who's always tinkering with her watercolor palette on her thoughtful and well-annotated urban sketching blog, and Jane Blundell, an online expert in watercolor pigments and mixing.)

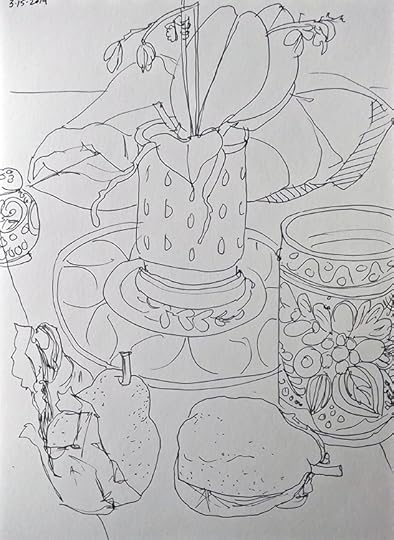

And there have been a few drawings. Here's one of my father-in-law's small Nefertiti-head with the houseplants we're coaxing through the winter, and a still-life of two pears wrapped in paper and the orchid pot that seems to keep reappearing in many of my drawings this winter, because of it's pride-of-place on the table where we eat.

But the most fun I've had making things lately happened on the day before Ash Wednesday, called variously "Shrove Tuesday", "Fat Tuesday" or "Mardi Gras", when the cathedral traditionally holds a pancake and sausage supper. I don't think many Anglicans fast during Lent, so this won't be the last time they see fat or meat for a while, but it's a nice tradition to observe anyway. This year, the dean suggested that we wear masks to make it more fun. I spent an afternoon making these two for J. and me to wear, and they came out in a sort of Viennese style, with the gold beaks. I've never been big on dressing-up, but this event was a lot of fun and I loved making these masks!

I hope that you can see signs of spring wherever you live (unless you're in the southern hemisphere) and are able to do whatever keeps your spirits up!

March 11, 2019

An Open Lenten Letter to my Bishop

How should our diocese respond to the Anglican Communion's refusal to Invite same-sex spouses to Lambeth?

Dear Bishop Mary,

This week we observed the beginning of Lent together at the cathedral, with prayer, a solemn liturgy, beautiful music. During the Ash Wednesday service, and as you placed the ashes on my forehead, I found myself reflecting on a sermon sent to me earlier in the day by my sister-in-law.

The author, Fr. James Weiss of Boston College, wrote: "What to give up for Lent? The answer is simple: Anything that gets in the way of loving. Lent is not a negative, it is a positive. What do you need to give up in order to love better?" This simple but difficult suggestion encouraged me to think about personal answers, as I struggle with my own crankiness and emotional fatigue at the end of a long winter here in Montreal. But I also thought about what it means for us as a community. How can we love others -- especially the marginalized among us -- more fully and unconditionally? How can we, as a diocese, lead the way toward "loving better?" Where are the obstacles in our path, and what can we do to recognize and surmount them?

Bishop Gene Robinson preaching to a full church at the first OutMass held at Christ Church Cathedral, Montreal, in July 2006

One issue where we, as a diocese, have made great progress, has been toward full acceptance of LGBTQ+ persons. Like you, I am a straight white woman who has been blessed with a lifelong marriage to the person I love, the right to which was never questioned by anyone. Because of my many privileges, I have always felt it was incumbent on me to fight for the right of all people to full equality, and especially the right to love and marry whomever they choose. As the author of the 2006 biography of Bishop Gene Robinson (who became my own bishop in New Hampshire) I was involved early in this debate within the Anglican Communion and Episcopal Church. After we moved from the U.S. to Montreal, I was proud of our cathedral, and later the diocese, for taking a strong leadership role in moving us forward toward openness, inclusion and acceptance, to the point where this is barely an issue anymore among us. So it was with dismay that I heard that that same-sex spouses will not be invited to the dicennial Lambeth Conference of Anglican Bishops in England in 2020. You will be attending as our representative. What should our response be? Can we send a message with you that conveys all the growth and love that has been shown over this past decade and more here at home -- that explains that we have given up the things that get in the way of loving?

I appreciated the statement by Archbishop Thabo Makgoba of Cape Town, calling on all bishops to attend regardless of their differences on sexuality: 'Whether you agree with where the communion is, whether you don't agree, come and express your difference in this beautiful space which is a gift from God. Don't just stay at home and say "I'm not going". Even so, some African bishops have said that they will not attend, presumably because they have disagreed with the ordinations of gay bishops and, in some cases, of women.

This letter is not a request for you or other Canadian bishops to boycott the conference, it is an appeal to you and to our Diocese to use this Lenten period as a time of reflection on how we feel, and prayerfully consider what our response should be. For my own part, I cannot call myself a follower of the Gospel, and then exclude anyone.

I hope that other members of this diocese will not just respond on social media, but write to you or communicate to their representatives on the Diocesan Council how they feel about this issue. I hope that a response can be crafted that is consistent with the message of love with which we are trying to shape our lives, and which we show to the world. And this last is important: the world we live in and represent has moved on, society has moved on. The Church should lead on moral and ethical issues, but instead it tends to lag behind, or to take positions which are widely seen as wishy-washy at best and hypocritical at worst. As attendance declines, and young people in particular look for role models and ways of engaging positively with a chaotic, confusing and destructive secular world, we must lead and do so publicly.

With thanks for your leadership, and very best wishes for a fruitful Lenten journey --

Elizabeth (Beth) Adams

February 28, 2019

The Best Thing I've Read about "Roma"

"Roma" exposes Mexico's darkest secret,

by Marcela Garcia in the Boston Globe

Such an excellent essay by Marcel Garcia. A number of people I've talked to may have liked this movie, but when we've talked about it in more depth, it's like we've seen two different films. That's always possible with a book or film, of course, but in this case, and at this particular time in history, I've found the dissonance quite disturbing.

It always bothers me that so many people think they already know all there is to know (or all they want to know) about the complex cultures south of the American border, when they actually know very little. I'm probably hyper-sensitive because I too was quite ignorant before I started going to Mexico and learning about it myself; I wasn't even sure I wanted to go, except that I knew there was a tradition of art that I wanted to see firsthand. Now I wonder how I could have been so limited. Where does this ignorance come from? Is it because we are inundated with media "information" and mass culture through Hollywood films and TV, and equate that with real knowledge? Is it because most people don't travel to Latin America beyond the resort beaches? Is it because so few of us form real friendships with people from different cultures, religions and ethnicities than ourselves, where we are willing to actually listen to and learn from the truth of their lived experience? Perhaps most people simply don't want to be stretched in this direction because it also requires looking at oneself.

I've now been to Mexico City for six extended periods of time, and have relationships with a number of Latin American friends. Yet with every visit and conversation, as with people from every culture different from mine, I realize how little I knew, and still know. Of course I've become uncomfortably aware of my own privilege, and ability to travel and come back to my far easier North American life. But it's a lot more than that. I want to be as open as possible when I see a film or read a book or talk to someone, as well as when I'm traveling, so that I am able to learn. I don't want to live in a North American bubble and take it with me everywhere I go. We all do that to some extent, but dropping it consciously seems to be more than most people want to do.

I also know firsthand how uncomfortable this process can be. I've been doing it for my entire adult life, partly because I married outside my culture, but also because of a longstanding desire for knowledge of otherness and for being stretched. I know everyone doesn't share this, or feel that the reward of growing wiser is worth the pain of feeling uncomfortable, hurt, misunderstood, or being in the minority, where we suddenly have to listen and accept different ways, and not be in a position of control or power. I get it. Most of us prefer to stay in our own tribe, however narrowly or broadly we define that. The world is moving in a different direction, though, and we can either accept that, understand our own privilege, and change -- or fight against it, which I see so-called liberals doing just as much as conservatives, when it involves actually confronting one's own stereotypes and sense of entitlement or superiority. It's one thing to oppose building a wall, or separating families, and entirely another to actually learn what is beyond that border, or who those families are, or our own complicity in the systems that have made them want to leave -- perhaps for a life of domestic servitude in America.

Roma confronts racism in Mexican culture, but it also asks us to look within. So I was grateful for Garcia's insights and explanations about her own culture, and the lens through which North America has viewed both Mexico and this particular film. I'm grateful she took the time to write this piece.

February 23, 2019

Exploring Delphi on Paper

In the last two weeks, I've been making some drawings and small paintings of Delphi, trying to explore what made it such a special place for me. What do you do with ruins? We're undoubtedly influenced by all those 19th century travelers to the Middle East and Mediterranean. I saw a lot of them in museums on this trip: here's an example by Jean N. de Chacaton, a view of the Parthenon painted in the mid-1800s.

It's tempting to try to draw the monuments accurately and make pretty travel pictures, especially when the light is so clear and graphic as it is in these places. I always find myself sidetracked in that direction, and it's enjoyable to do detailed drawings and watercolors, or even fast sketches as a record of a place. But sometimes there's something more that feels like it wants to be expressed, and the actual "stones" seem somewhat peripheral to that.

So I started out, as I often do, with a detailed drawing that came before I was even thinking about doing a series. In fact, it was during the making of this first ink drawing that I began thinking about the essence of this particular place and how to express it. But it's often a circuitous route to an answer, and even then, there are multiple possibilities, because a landscape is complex, and so is our emotional response to it. There are physical elements of that landscape that affect how we view it; there is the weather and atmosphere; there are the people we're with, or not; events that happen while we're there -- and there is whatever we bring with us: knowledge of history, reading we've done or things we've been told, or perhaps a completely blank slate; things that happened on our journey there; expectations; the mood and physical state we're in on that particular day. Finally, certain places seem imbued with the events that have happened there and the people who have been there before us. Delphi is certainly such a place. Some people are more receptive to that than others, and that receptiveness may vary with different times or circumstances: arriving at the same time as two noisy busloads of school children is a big difference from being alone at a site.

It's a process to sort through all of that in order to find a personal response and find a way to express it simply and clearly through art, or writing, or any other creative form. A teacher once suggested, when I spoke of my confusion and difficulties with this, "search it out through drawing." I've tried to follow that advice, and I still find the process challenging, but now more fascinating than confusing. Often, as here, I have no clear idea where I'm going at the beginning. By drawing the reality of the subject, I start to edge closer. Certain forms may stand out, or become more important, or perhaps I notice lines in the scene that lead toward or away from each other. I may begin to remember things I had forgotten about how I felt. Recalling the scene through drawing it may tell me something I didn't "hear" when I was there. It is a process similar to a type of dream analysis, where in a quiet meditative state we revisit a dream and the characters who appeared in it, and have a waking conversation with them. When we pay close attention a second or third or fourth time, certain elements drop away as unimportant, and others come to the fore; we begin to identify with certain people or elements. It's also true that whatever answers we get may be partial; a month or a year or even longer may elapse, and then fresh insights might come.

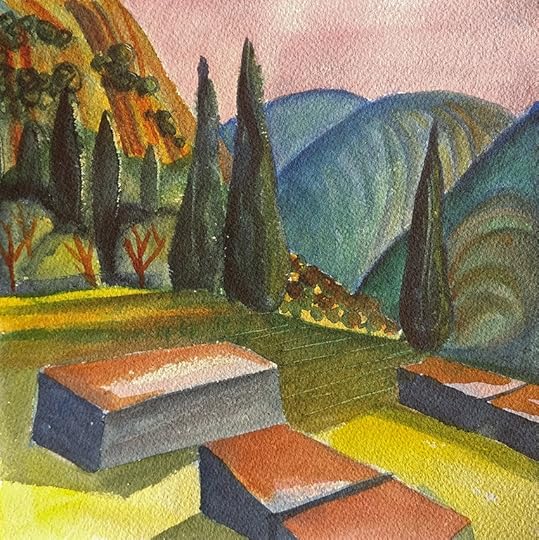

This charcoal sketch came next. Obviously I was starting to hone in one the trees and the way they create a unique vertical punctuation on the side of steep mountains that form a series of interlacing triangles.

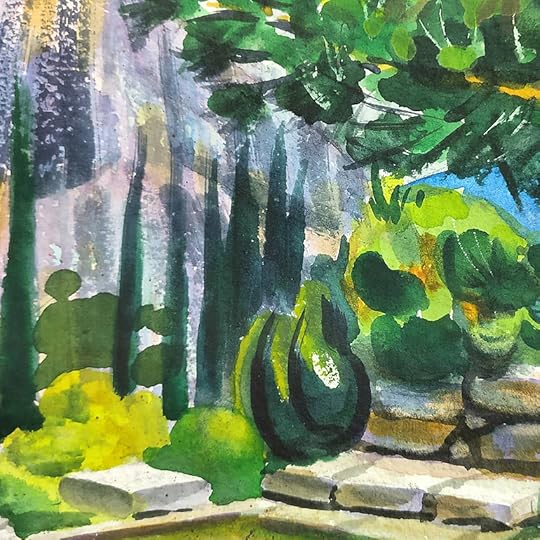

This gouache study followed later the same morning. It crops into the scene in the charcoal drawing to emphasize the trees -- are they cedars or cypresses? -- and adds some minimalistic color. The rocks from the ruin in the foreground are present, but downplayed. I liked this sketch a lot and felt it showed a new direction that could go toward either a print or a painting. That was confirmed when I posted it on Instagram and got an immediate direct message from a friend whose instincts I trust: " I love this." I replied: "It's so...nothing...and yet..." and he responded, "It's all there." Then I asked myself, OK, if "it's all there" -- WHAT have I put there? Old rocks, cedars, mountains, sky. Simple shapes. And what about these non-colors? Why do they work? Because they are harmonious. But in order to figure that out, I had to deviate some more.

Next I used watercolor on rough Arches paper. The full sheet is above, and a cropped detail below that I think is the "real" picture and contains most of what I was aiming for.

I love the saturated color and the freedom of the brushstrokes, for themselves, but the result is pretty unreal for this context.

Delphi, I was beginning to understand, was in a spectacular setting on the side of Mount Parnassus, but its overall feeling was very quiet and "inner." That came across better in monochrome or subdued colors, which I used in the next iteration, the gouache above. I was also getting interested in the shapes on the sides of the mountains.

That was followed by another watercolor. I like it, but felt both of these were too pretty and didn't say much beyond that. The full view kept looking like a postcard.

Then I did another bright watercolor, above, from memory, simplifying and stylizing the shapes. This one seems to have possibilities too. Historically, the monuments here would have been painted in bright primary colors - we tend to forget that. A friend who is Greek wrote to me that she liked it a lot: "Beautiful, those light lines on the cypresses. And the expressive colors feel more apt in uniting the landscape with its wild, somewhat extravagant past than the usual soft watercolors which mainly just point out the natural beauty of the Mediterranean landscape."

Finally, last night, I did a brush drawing in ink and indigo watercolor, also from memory. The single, rather Munch-like tree, standing alone, comes perhaps closest so far to my feelings about the place. I also return to that early gouache, and can see better why it works. I'm getting closer, but I'm not finished yet.

What's made the greatest impression on me is the Greek sense of place -- they had an unerring ability to choose particular sites for their cities, and within them, for their temples, theatres, meeting places, dwellings and tombs. I've only understood this by being in those places myself; you simply can't feel that from books or slideshows in art history classrooms. When you are actually there, you see why they chose a particular site: regardless of the centuries that have passed, usually you can still see the view that they saw, feel the wind off the ocean or glimpse the water or a mountain in the distance; you have a sense of what they felt was special or sacred in that place. This uncanny ability to sense what is special about a place, and use it for its full effect, seems equal to me to their architectural skill, or mastery of balance and harmony.

For the Greeks, Delphi was the center of the universe. Kings traveled in person from all the city-states, including the islands, to consult the Pythia, the Delphic oracle in the temple, and they built treasuries on the side of the hill to house part of the spoils won in battle, as a gift to the gods. Mount Parnassus is remote, and far from the sea; at 2,457 m (8,061 ft) it is one of the highest mountains in Greece, sacred to Apollo and Dionysus, and it was also the home of the Muses, who inspired poetry, art, and dance. Delphi is located far up on its slopes. It was a real journey for us to get there, in a modern car, on winding mountain roads. I can hardly imagine what it took for ancient people to make that journey and arduous climb; clearly it was of vital spiritual and political importance to them.

Oracle of Delphi: King Aigeus in front of the Pythia. 440-430 BC, drinking cup, Attic red-figure, Kodros Painter. (Berlin, Altes Museum)

But going there myself, I could see and feel why they thought it was so special. On the way up, we drove hairpin turns, stopping once for a shepherd with his flock of goats, the bells around their necks tinkling, their hooves clicking and scrambling on the loose rocks. We passed through the narrow winding streets of the town of Delphi, perched precariously on the slope, and back into the wilderness to the ancient site, from which you see no signs of human habitation. It's spectacular and wild: from the steep rocky slope with its pines and cedars, you look down across a deep rugged valley. Hawks and owls and crows must have been common then as now, the wind blows, the dark cedars punctuate the sky, and you climb the same paths, past the market and the treasuries, up toward the man temple where the oracle gave her riddles, and even higher to the theatre. Of course, what was once a busy mecca is deserted except for tourists. I tried to imagine a bustling marketplace, smoke rising from sacrificial fires, human voices everywhere: that was difficult. But there was something about the place itself that hadn't tumbled with the stones, and had perhaps even preceded them. Standing on the ridge above the main temple, I tried to imagine coming there any of the grand buildings had even been built. Who were the people who identified this place and first called it sacred? Perhaps what I was seeing and feeling now was closer to what they felt. I kept hearing the cry of a hawk as it circled and rose in the mountain thermals, and then plunged down into the deep valley we can had come from. Above us was snow, the inaccessible realms of the gods. Closer by, in a glade in the woods, near a rushing spring, perhaps the Muses still danced: it wasn't hard to imagine.