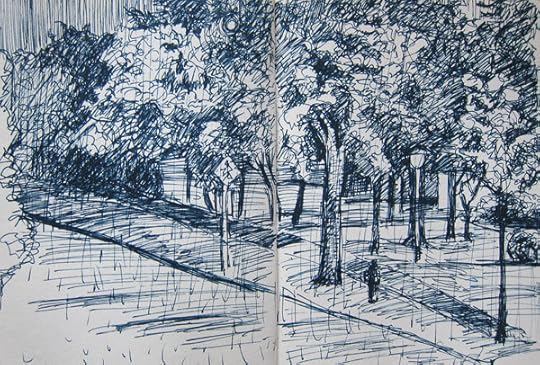

Elizabeth Adams's Blog, page 27

February 18, 2019

Drawing Basics #3: 7 Reasons for Drawing

We all need positive reasons for getting on a creative path, and sticking to it. As I remarked before, there's often a false friend in our heads, making negative comments that can derail us. Even if we can't get rid of that all-too-familiar voice, we're going to learn to tune it out. One of the best ways to do that is to remember all the excellent reasons for taking up this creative pursuit and building it into our daily life.

Here's a list of seven unarguable reasons for drawing:

Almost everyone can learn to enjoy drawing and sketching

Drawing is a way of connecting more deeply to our world and what we see

The brain-hand-eye connection is fundamentally human and physically and psychologically good for us

Drawing is a meditative activity that helps us slow down and re-center

Inspiration is everywhere

Drawing is the ultimate portable activity

Learning to enjoy and appreciate process is easier and more valuable as we get older

To expand on these reasons a little, let's take them one by one.

1. Almost anyone can do it. No, not everyone is going to be Rembrandt. But the basic skills of training one's eyes to understand what they're seeing, the brain to interpret that in two dimensions, and the hand to put it down on paper, is something that can be taught, and most people can get far better at it than they thought possible. It's not a question of tricks, but it's about paying attention to spacial relationships, relative size, shape and form in a new way. There are lots of excellent teachers out there, including on line, but the most important factor is practice. Furthermore, we can all continue to make progress: this is a skill that improves with practice forever. Furthermore, we live at a time when no one thinks that drawings have to be literal or super-realistic representations. You can develop your own style and forget about being judged against some universal standard. That's both freeing, and inclusive for a much larger proportion of people who want to do art.

30,000 year old painting of a hyena from Chauvet Cave, France.

2. Close observation changes our relationship with our world. When we look at something -- a walnut, a doorknob, our own face -- with the intention of drawing it, we simply see it differently. During the process of studying that subject, we connect with it on a different and often deeper level than we ever did before. We will never see that flower or tree or scene again the way we used to, and what we've learned about them through drawing will become embedded in our brain. That, right there, is a major reason why drawing is so valuable. Drawing changes the way that we see.

3. Drawing stimulates the brain in ways that strengthen the neurological system and can even help stave off dementia. It's also a pursuit that is fundamentally human, causing us to use and develop the connections between seeing, using our hands in a skillful way, and thinking. As our lives become more and more digital and less and less manual, we are in danger of losing fundamental aspects of human skill and behavior. Drawing, playing musical instruments, and making things with our hands are all brain- and life-enhancing pastimes not only because they create things of value, but because they touch something deep within the human mind and heart. What will humans be if these skills are lost?

4. It's meditative. So much has been written about the value of slowing down and doing meditative things that I'm not going to go into it here. Drawing puts me into a different zone: when I'm doing it, that's all I'm thinking about, and when I'm finished, I'm calmer because I have been somewhere unlike the daily routine.

5. You don't need to go anywhere special: the inspiration for drawing is all around you, in your home, your place of work, on the metro or busy city street, out in the countryside. We can draw everything from the smallest beetle or blossom to a vast ocean or mountain landscape: the scale and the vision is completely up to you, and it can change with the day or hour.

6. It's completely portable and inexpensive. How many cool things can you do with so little equipment? All you really need is a piece of paper and a pencil or pen - in moments of boredom, I've made many sketches on the backs of programs or napkins, meeting notes, the corner of a placemat. I've never drawn on pieces of music, but I've certainly drawn on the service bulletin or music lists in my choir folder during a less-than-exciting sermon. With a small sketchbook and some relatively inexpensive supplies, you can create a sketching kit that fits in your purse or pocket and can go with you everywhere.

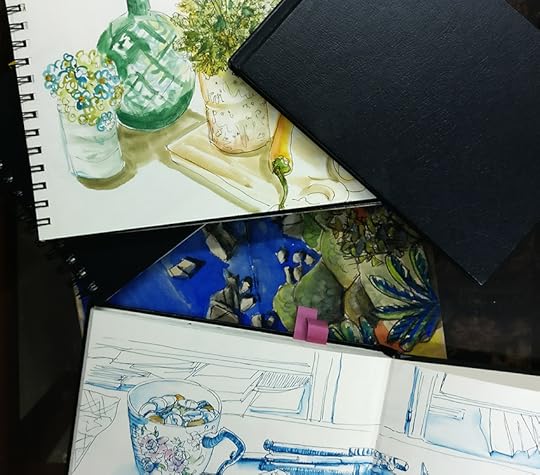

7. Being older helps us to appreciate the process of doing something rather than judging individual results. Though I've been drawing since I was a child, I've found that I appreciate it for itself -- as a process that I enjoy -- a lot more as I've gotten older. I'm less concerned about making a great drawing every time, and more content to explore, try new things, experiment, and also just to document my world and daily life. When you have a regular drawing practice, the sketchbooks begin to form a record, like a journal, and that's very satisfying. The quality of the individual drawings is less important than the accumulation of knowledge and experience, and what those drawings say about your life at the time. But some of them do stand out, and you can look back and see progress and breakthroughs. I've photographed most of my sketches over the past five years or so, because I would really hate to lose my sketchbooks if we ever had a fire or flood, or if one were lost or stolen while I was traveling. I think most artists feel this way. Our sketchbooks are the closest to the bone: they're our private workshop, and hidden within them are often memories or coded, personal hints of whatever was going on in our lives at a certain time. The creation of drawings, over months and years, can become a quiet practice without pressure or angst, but with great personal value. For me it has aspects of spiritual practice; for you it may be something else, but it is on that kind of level, once you stop pressuring yourself to do it perfectly.

February 5, 2019

Drawing Basics 2: Fear of Failure, and How Not To Succumb

Let's get some of the clichés out of the way, up front. Do any of these sound familiar?

"Oh, I can't draw a straight line!"

"I'm not a REAL artist..."

"I used to love to draw as a kid, but my teachers told me I didn't have any talent."

"I don't think I have the patience for it anymore."

"I don't have enough time in my day."

"Oh, I'll never be able to draw like ______."

"I'm afraid my kids/husband/friends would make fun of me."

"I've tried to do it, I've even taken classes, but I get so discouraged."

"I was told I was pretty good once, but then my life got so busy...and now it seems like it's too late."

OK, that's just a sample of the phrases I've heard from wistful would-be or former artists over the years. Maybe it surprises you, but I've said some of the same things to myself. Whenever we consider starting something new and challenging, we're listening first to a positive inner prompting that ranges from a subtle whisper to an insistent, persistent longing. That voice in our head is important, and we need to pay attention. When we're children, we just plunge in and try things, but as older people, that inner voice of longing and desire and attraction is followed immediately by doubts, and arguments aimed at convincing ourselves why failure is likely. That second voice is good at what it does: it's had a lot of practice! We truly are our own worst enemy.

Try to go back to the source of the love and the longing. Where does that prompting come from? Can you remember? Did you like to draw and paint as a child? Do you love looking at art and would like to try to make some? Did you once draw and paint and then gave it up? Why? What happened? Now, when you think about taking up drawing or painting, what is the inner dialogue that follows? Are there discouraging memories that surface, or fears about what might happen if you did try?

Here are seven reasons why I think people give up almost before they've begun. (And of course these apply to many pursuits, not just drawing.)

Comparing ourselves to others.

Expecting good results too quickly

Difficulty enjoying a solitary process while beginning

Difficulty establishing a regular practice

Negative conditioning from childhood or later

Embarrassment, fear of ridicule

Setting unrealistic goals

Now, let's take those apart.

1. Comparing. We all compare ourselves to others, no matter how good we are or how long we've been at it! It's human. But it's also self-defeating. The bottom line is that comparing yourself to yourself is the only helpful comparison, and practice makes you better. You will never improve if you don't do it at all, so there's only one solution: getting started!

2. Lack of Patience. It takes time to develop any skill, and you will need some patience. There's no magic formula, but what I would suggest is to fall in love with the process and the materials. Really enjoy the feeling of the pen or pencil on the paper, or the colors of your paints. Buy some good materials and use them. Enjoying the process of seeing and creating and making is what saves all of us, because we all get discouraged. If you focus too much on the finished product instead of the creative process, you're making it a lot harder for yourself. Yes, look at a lot of art, see what you like and think about why, get inspired, ask professionals for advice. But just keep your eye on the ball, which at the beginning is a regular practice of drawing, ideally every day.

3.Getting through the early stages. OK, you say, that's hard when I feel so clumsy and inept. Right. You might take a class, watch videos, join a sketching group or team up with a partner. Find the parts of the process that are easy to like, like going to a park or botanical garden, or a favorite cafe. Or you can embrace the solitude and the meditative time spent with yourself. Enjoy the realization that you're opening your eyes to seeing things differently, seeing things as an artist! Focus on the seeing, and draw a lot without being too hard on yourself. Draw something simple every day -- don't start with people, or your dog or cat, draw everyday objects with simple shapes, even if it's just your teacup or a piece of fruit! Make it a practice. Over time, you will be surprised, because practice in seeing always pays off, in more ways than just in art.

4. Establishing a Practice. We all accept that playing an instrument requires practice, but I think a lot of people think art is a matter of talent we're born with and arrives sort of fully-formed. In fact, drawing is a discipline; you're training both your eyes and your hands. Even if you get pretty good at it, if you stop for a while you get rusty. So practice is necessary. The trick (as with all forms of exercise) is to make it regular and fun, and then you'll keep at it. We're all different so I can't tell you what will work for you. My most basic advice is to get a sketchbook you like and always have it with you, or else set aside a time when, most days, you're going to spend fifteen minutes or half an hour drawing. Make it something enjoyable, precious and personal, whether that means having a cup of tea or coffee while you draw, or going someplace you especially like -- just carve out that time until drawing becomes a habit and something you look forward to. And as you can see here, it's OK to draw the same things over and over again!

5. Negative conditioning is the hardest thing to overcome. I'm so angry with the adults who discourage people -- from anything -- especially when we're mere children. It is so often more about the adult than the child, but it can scar us for life. Try to listen, instead, to the longing and the love you feel for art and for self-expression. That's the true and original thing, and no one can take it away from you, because it is human and universal. Every time you hear the discouraging, negative voice in your head, try to remember a place or a time when you felt inspired, and hold onto that rather than the negativity. Every one of us not only has a right to be creative, but it is our birthright as human beings. Our individual path is for us to discover, and choose. Overcoming negativity is difficult but possible, and getting on the path is the first step; in fact it's already a victory. (A personal note: I gave up art for five years in my thirties because I was so discouraged by interactions with a teacher whose words and method I didn't understand. I know the effect this kind of negativity can have and how hard it is to recover one's own path.)

6. Ridicule. We are all afraid of making a fool of ourselves! My answer to that is: I'm doing it, I've had the courage to take the risk and try something new, so I'm not going to let people taking potshots from the sidelines faze me. That's their own insecurity talking, or else simple meanness and bullying, and I'm not going to pay attention. If people close to you can't be supportive and understanding, tell them politely but firmly to leave you alone. If the person giving you a hard time is yourself...learn to gently tell that side of yourself to go take a walk, and return to your practice.

7. Unrealistic goals. Watch what you're projecting for yourself; listen to your inner dialogue. If you go into this imagining your work up on the walls of a gallery, with a crowd of admiring people telling you you're wonderful, you've set up a pretty high hurdle. We're fortunate that today we can share work online with friends, and to pursue the things we like to do with far-flung, link-minded people. I think it's a whole lot healthier than expecting to publish best-sellers or have a Carnegie Hall debut, and have gallery shows and sell our work for millions of dollars; very very few people ever achieve that, and frankly it doesn't necessarily mean the work is great. If you keep at it, you will find ways to share your work that are satisfying and rewarding, and you may even sell some -- but go back to point #2: keep your focus on the process and the pleasure of learning and making gradual progress in seeing and creating, which can continue throughout our whole lives.

What do you think? Have I missed anything important in this list?

Next: seven reasons why drawing is absolutely worthwhile.

February 3, 2019

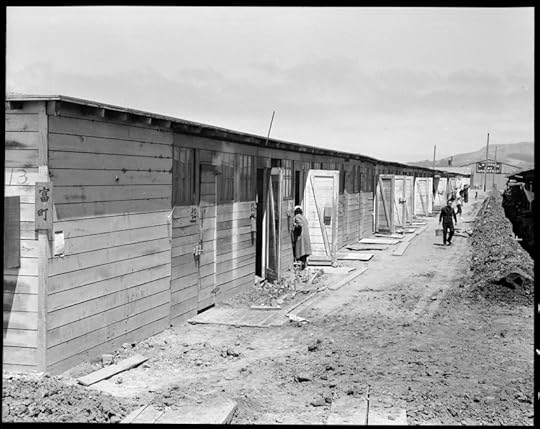

Never forget: Dorothea Lange's repressed photographs of Japanese internment

Dorothea Lange's caption: "May 2, 1942 — Byron, California. Third generation of American children of Japanese ancestry in crowd awaiting the arrival of the next bus which will take them from their homes to the Assembly center."

In 1942, the United States government hired photographer Dorothea Lange to document the rounding-up and internment of Japanese-Americans. But when the military and intelligence officials saw what her humanitarian lens had captured, the photographs were impounded and themselves "incarcerated" in the National Archives, only to be released to public view in 2006.

A desert garden created by professional gardener William Katsuki outside his dwelling in the Manzanar Relocation Center, California, 1942. Photograph by Dorothea Lange

Editor and Lange biographer Linda Gordon of Anchor Editions has published a selection of the photographs in the book Impounded, and writes about them on her blog at Anchor Editions. She is also making a limited number of prints available, with 50% of the proceed going to the NILC and ACLU, for their work on behalf of present-day immigrants. Gordon writes:

Lange worked nonstop for the next months, traveling to many cities and towns around California to document the Japanese people as they prepared for “evacuation,” as they were herded onto buses and trains, and moved into temporary housing in barracks and stables at horse racetracks and fairgrounds across the west coast. She then spent time at Manzanar, one of the largest concentration camps, situated in the eastern desert of Southern California where she continued to document the conditions and the people who were imprisoned. Despite much resistance from the camp authorities and military police, and several constraints on what she could photograph, she produced over 800 photographs during her assignment.

As I looked at Lange's images, of course they led me to consider what not only what they say about power and race, but also about our continuing need to victimize and make inhuman those who represent the "other." How many people in our world today are living in refugee or internment camps, or are forced to live behind walls that separate them from their former homes, lives, and loved ones? And while some groups have the funds and organizations to keep their past suffering in the public eye, most do not. How many will ever receive reparations for what has been done to them? Or will we, in fact, forget, and continue the forgetting?

Lange's caption: "June 16, 1942 — San Bruno, California. This scene shows one type of barracks for family use. These were formerly the stalls for race horses. Each family is assigned to two small rooms, the inner one, of which, has no outside door nor window. The center has been in operation about six weeks and 8,000 persons of Japanese ancestry are now assembled here."

“I remember having to stay at the dirty horse stables at Santa Anita. I remember thinking, ‘Am I a human being? Why are we being treated like this?’ Santa Anita stunk like hell.… Sometimes I want to tell this government to go to hell. This government can never repay all the people who suffered. But, this should not be an excuse for token apologies. I hope this country will never forget what happened, and do what it can to make sure that future generations will never forget.”

— Albert Kurihara, Santa Anita Assembly Center, Los Angeles & Poston Relocation Center, Arizona

January 29, 2019

Sketching & Drawing Basics: Paper

Recently, an Instagram friend asked me for some advice -- he wants to begin drawing more seriously and needed both artistic help, and some suggestions about supplies. It occurred to me that some of the readers here might also enjoy a really basic discussion of how to get started. So I thought I'd write a few posts, expanding on what of what I told my friend.

Two things hold people back who think they might want to draw or paint. The first is fear of failure, which often prevents them from beginning in the first place (or starting again in later life). I'll talk about that in a subsequent post.

The second obstacle is inferior art materials. Beginners often think they don't "deserve" to use artist-grade materials and tools, but unfortunately the result of using student-grade supplies, or those intended for children, is that your work will suffer and look far worse. Inferior tools behave unpredictably, pigments aren't ground evenly or are made of cheap imitation chemicals; cheap paper can be too absorbent or too slick, preventing you from getting the kind of results you've seen in other people's work, through no fault of your own -- except that the beginner doesn't know this. How frustrating and discouraging!

Investing in good materials will actually help you. You don't have to buy top-of-the-line paper and paint and brushes, but you do need to get decent ones. Then you have to actually use them -- even use them up! Fill up that sketchbook with drawings. Use more paint. Splash it around, have fun! Invest in good brushes and pens and learn how to take excellent care of them - they will last many years if you do.

It is almost impossible to make real progress in art if you have inferior tools, so buy the best you can, and try to use them freely. (I say this as someone who has a huge hoard of good paper, collected over a lifetime -- yes, I'm trying to use it up!) But my mother, who was an artist herself, always saw to it that I had good materials, even as a child. She let me use her sable watercolor brushes after I learned how to wash them and store them properly, and she bought me high-quality paper. This made a huge difference when I was learning to paint. So here are some suggestions about the first essential: paper.

Spiral-bound, hard-bound, and soft-cover sketchbooks.

My friend wrote that he was using his child's watercolor set, and a notebook which "might not be right for watercolor." I often see people sketching in little pocket Rhodia pads or other small notebooks. They're OK for a quick felt pen or pencil sketch, but first of all they're too small, and secondly, the paper is simply too smooth. When you try to use watercolor on paper that's too smooth and too light, it buckles, and the pigment runs. If you use it on paper that's too absorbent and fibrous, the pigment sinks in too fast and loses its brilliance; subsequent colors sink into each other and the result is muddy rather than bright and sparkling. Fine watercolor papers are available in pads or blocks from top manufacturers such as Arches and Fabriano; those papers will allow soaking without buckling, and endure a lot of repeated applications of color, as well as scraping and other surface abuse. However, you don't need a dedicated watercolor paper at all for sketching with pen and light watercolor washes.

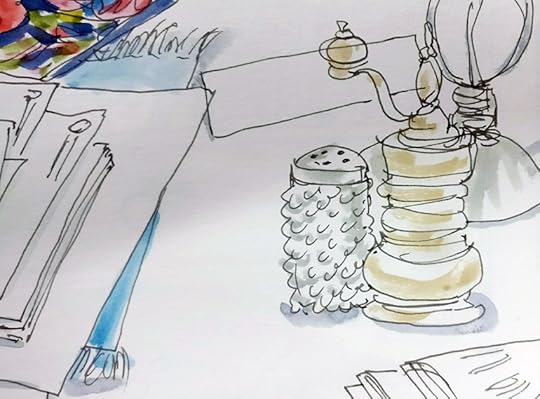

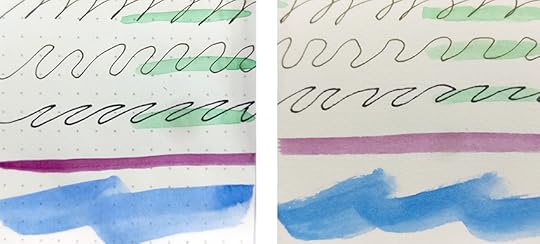

On the left: Fabriano "Misto" - a very smooth, thin paper with dots. Ink lines are sharp, and so are the edges of brush washes. The color stays bright, but the paper buckles. There is almost no absorbency or opacity, but for a smooth paper, it's a nice surface. On the right, Stillman & Birn's "Gamma" - a good cross between a high-quality drawing paper for various dry media, and a watercolor-friendly surface that's absorbent and toothy enough to accept light ink or watercolor washes without buckling, while still retaining the character of the brush strokes.

After a lot of trial and error, I've standardized on Stillman & Birn's sketchbooks. The Gamma series (what I use) has ivory paper; the Alpha series is the same paper, but in bright white. They come hard-bound (like a regular hardcover book) or spiral bound, which lies completely flat; you can also get a soft cover version in some sizes, and the company has recently released a new line with toned papers - grey, beige, and black. Many people also like Moleskine art notebooks. These papers are excellent for pen and for light washes, where you're not going to get it soaking wet. What you want is paper that's not too rough, so your pen can make a clean line, but also not too smooth so it has some absorbency and what's called "tooth" - the ability to accept an ink or pencil line with a bit of drag or resistance, and a bit of texture so that the pigment catches in the little invisible irregularities on the surface. Many watercolor papers are too rough for a good pen line, so if you want to sketch in ink first, and then add some watercolor wash, you want a paper that is not totally smooth, and is designated for "light washes."

A page with heavy ink lines and quite a lot of watercolor - you want your paper to hold up this well.

What size? Your ideal sketchbook will be small enough to carry with you, but not so small as to constrain you. You don't want to draw with cramped fingers and little tiny lines. My standard S&B sketchbooks are spiral-bound hardbacks, 8.5" x 5.5". In my studio I also keep a larger one, 9" x 12". I also use small Global Art Hand Book journals when I have to go smaller and lighter for travelling - these have very nice fabric-covered covers, with an elastic band and a plastic pocket in the back. I like their small square (5.5 x 5.5") and the horizontal landscape format; you might also try the Moleskine art notebook line. I prefer a spiral notebook (because it lies flat, I can work horizontally or vertically, and sheets can be removed) and am particular about the paper, but many people love the Moleskine journals and there are many different formats to choose from. Personally, I think the pocket notebooks in a 3.5" x 5" page size are just too small to allow for free hand movement; they tend to make me work too tightly. On the other hand, if I don't have a sketchbook with me because it was too big to fit in my pocket or bag that day, I often regret it!

The S&B spiral-bound sketchbooks have become my "regular" choice because they are easier to work in and simply nicer than the less-expensive Strathmore or Canson pads found in most art supply stores. There is an undeniable psychological and emotional element to artist supplies. I have used many, many types of journals and sketchbooks, with good paper inside, but have failed to "bond" with them and therefore didn't use them consistently or happily. The S&B sketchbooks suit me, but once I bought one that was hard-bound instead of spiral, and with white paper instead of cream, and I absolutely hated it. The drawings I did weren't as good, I didn't enjoy working in it, and I eventually abandoned it in disgust. The paper was identical! So there's just something extremely personal about the paper we work on, as well as the format and style of sketchbook we use. The paper needs to be good, with the right quality and attributes for the type of work you intend to do (wet, dry, light wash or whatever), but beyond that, it is up to you.

Note: I don't receive, and will never accept, compensation for endorsing any manufacturer's products; these recommendations are completely without strings, or benefit to me!

January 24, 2019

Write!

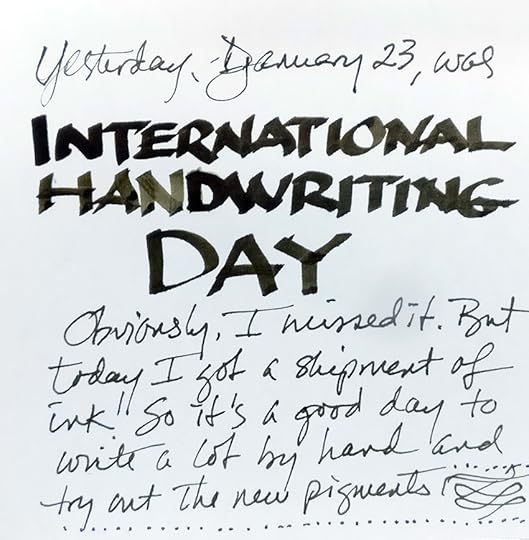

How is your handwriting these days? Mine has really deteriorated, like any other skill that is seldom used. I didn't even know there was a day set aside as "handwriting day" -- sounds like a marketing ploy -- but, as I wrote recently, I've just ordered some new inks and a new fountain pen. I got my ink today, so it felt like the right time to write a bit, and think about handwriting.

My "normal" handwriting is the fast, right-leaning scrawl you see above. It's embarrassing to me to look at letters written by my mother, my grandmother and her sisters, or my great-grandmother, all of whom had beautiful penmanship, and -- I'm afraid -- more patience than I do when writing a letter or a journal entry. Here's the beginning of one from my grandmother, where she excuses her poor penmanship -- as if! -- because she's writing on her lap.

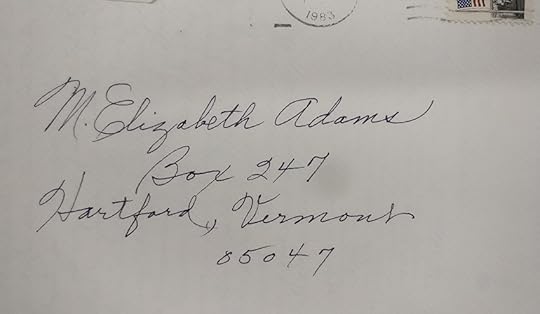

I miss those letters and those correspondences: the anticipation, the thoughtfulness of composing a reply, the slowness of the exchange. I miss finding a real letter in my mailbox in college, or from a faraway boyfriend or close friend. Here's an envelope from my grandmother, addressed to me in Vermont in 1983. Gosh.

It's so beautiful!

I actually made my living for a while as a calligrapher. Those pages of carefully-formed calligraphic scripts don't resemble my handwriting, and they represent a lot of slowing down and patience and slow breathing. For me, handwriting like the examples above is more like talking, and it moves a lot faster. But when I look at the way I write now, i'm shocked. It feels to me like it's time to do some of those breathing exercises, slow down, and write somebody -- maybe myself! -- a letter.

Not that what we write now, by email or even by text, is any less sincere or thoughtful. I still carry on long correspondences with a number of people, and we don't have the patience or the time to do it by snail mail: those days, I'm quite sure, are long gone. But our brains are connected to our hands, and writing is part of what makes us human. We lose those manual dexterity skills at our peril, I think, and I bet that one day scientists will discover that the near-overnight loss of writing by hand, and related skills, affected our brains in some significant ways. I know some of you keep handwritten journals, or write "morning pages" each day. Others draw or sketch. But the time most of us now spend with a pencil or pen in hand is really minimal - for some of us, it barely exists anymore. Do you think it's important? Do you miss it? What takes its place in your life these days?

January 9, 2019

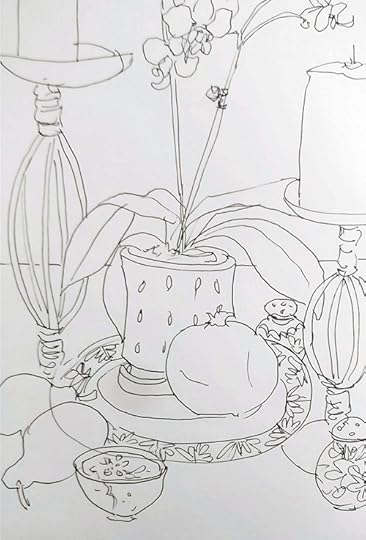

Some recent drawings

Clementine peels and Mexican ceramics.

I'l get back to the travelogue soon, but wanted to share a few drawings from the past month or so.

Succulents and a bowl of green almonds.

Although I didn't manage to do a lot on the trip, I've been drawing pretty steadily since we returned.

Succulents and Knitting.

Yesterday I ordered a new fountain pen, my first in a long time -- it's a Moon Man M2 eyedropper pen. These are pens with barrels that can be filled with an eyedropper, rather than a cartridge or piston system. I've never had one, and thought it would be worth a try at only $20; other users praise the extra-fine nibs on these pens.

Embroidered purse and desk objects.

My favorite pen for drawing or writing is a now-vintage Shaeffer 580 with a beautiful, responsive gold nib, but I'm becoming reluctant to take it with me when I travel. I've never been completely happy with the Lamy Safari I bought as a low-cost alternative: it's easy to fill and use, but the nib is too stiff for me. And while I'm quite happy with my usual Noodler's Lexington Grey ink, I'm also eyeing some other possibilities from Noodler's range of bulletproof (entirely waterproof and bleedproof) inks: possibly a blue-black ("54th Massachusetts"), and a dark khaki ("El Lawrence").

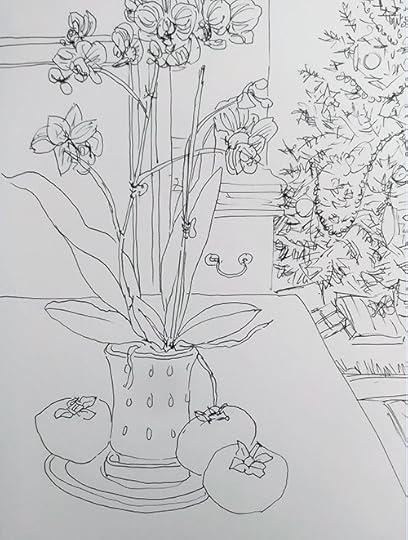

Two versions: Still life with pomegranate, pears, and orchid.

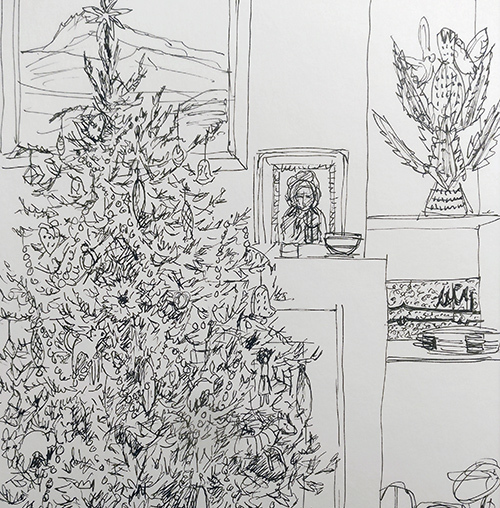

Finally the Christmas tree made its appearance, the pomegranate got eaten and was replaced by persimmons. It's all really very mundane, I just draw whatever's in front of me.

And, below, one more of the tree in front of the fireplace. Montreal has forbidden wood burning and none of us want to pay for the expensive conversions required for gas, so for now, there will be no chestnuts roasting on this one.

We took the tree down yesterday, and there was a snowfall. Outside, the world is white, and inside it looks pretty bare: midwinter has arrived. It would seem like a good time to do some watercolors, just to put some color into life! But I don't mind the monochromatic, graphic quality of winter. Drawing with pen or charcoal often seems more appropriate now, and I think my mood and vision become more focused in response to the weather and the starkness. We'll have at least three more months of it, so it's important to find a way through that embraces the season.

December 31, 2018

Book List - 2018

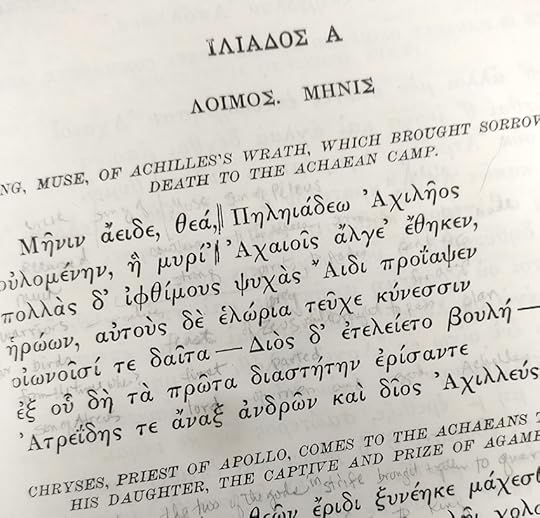

In the past year, I read fewer books than usual, but if anything I thought about them more. The year began with a big project: reading Homer's Odyssey chapter by chapter with two other friends, each of us reading a different translation and discussing them online. As the only one of the three readers with any ancient Greek, I was the one who looked up and struggled through passages we wanted to compare. This not only revived my interest in the language but rekindled my desire to go to Greece, which came true at the end of the year. The final book I'm reading, Mary Renault's Fire from Heaven, is a novelistic treatment of the life of Alexander the Great, whose Macedonian birthplace we visited. There were a number of other classical books, or works inspired by them, in the early part of 2018 - specifically several by Seamus Heaney; Kamila Shamsie's Home Fire, a version of Antigone with an immigrant heroine and her brother, a suspected ISIS terrorist; Alice Oswald's Memorial, a poem that lists all the deaths mentioned in the Iliad, and Daniel Mendelsohn's An Odyssey, about teaching the book to a class that included his own father and then going on a trip with him that recreated the ancient voyage.

Besides this focus, books I particularly enjoyed in the past year were William Finnegan's Barbarian Days, an autobiographical book about surfing that held me riveted from the first to the last page; Cesar Aira's bizarre and miraculous Miracle Cures of Dr. Aira, Michael Ondaatje's luminous latest novel, Warlight, set in post-WWII London,, and Men Without Women, Haruki Murakami's most recent collection of short stories, many of which appeared first in The New Yorker.

The book that impressed me the most was probably The Diaries of Emilio Renzi, Vol 1: The Formative Years, by Ricardo Piglia, one of the greatest of all Latin American writers. When diagnosed with a terminal illness, he spent the last ten years of his life compiling, revising and editing the huge volume of journal notebooks he had kept throughout it under the name of his alter-ego, Emilio Renzi. They are just now being published in English. The concept is monumental, and the writing extremely compelling; for someone like me who has kept journals off and on all her life (including this blog) it was a mind-bending project. Vol 1 covers the years when he was beginning to want to be a writer, through university, and up to the time his first book was published that brought him acclaim -- so it is the diary of a writer becoming a writer. It was a great contrast to last year's mammoth project (Knausgaard). Volume 2, The Happy Years, came out in November, and I look forward to reading it. I followed Vol 1 with one of Piglia's novels, which was great, but confess I liked the journals better. If you like Bolano, you will appreciate these.

Finally, in the fall, Jonathan and I both read William Dalrymple's From the Holy Mountain: A Journey in the Shadow of Byzantium, a memoir of the writer's pilgrimage in the footsteps of 6th-century monk John Moschos who visited Orthodox monasteries all over the Byzantine world of his time. Dalrymple's journey begins on Mt Athos, Greece, takes us to Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Israel and the West Bank, and ends in the Egyptian desert. The book was written in 1997 and chronicled not only where Moschos went, but the lived reality of the same monasteries fourteen centuries later, most of which were, or had been, under attack by other religions and political groups and were currently inhabited by only a handful of monks; his own visits sometimes alerted the authorities and endangered the present monks, who could be accused of harboring a spy. But it was exactly the right book for us to read before our own first trip to see the Byzantine world at closer quarters; I'll be writing about our trip to the ancient monasteries at Meteora, Greece very soon.

As always, I look forward to hearing what you've been reading too, so please post your lists in the comments as well as your reactions to any of what I've said or listed here! And best wishes for happy reading adventures in 2019! I'm anxious to read the next Piglia, as I said, and the new Murakami novel, Killing Commendatore; also on my list is the Alexandria Quartet of Lawrence Durrell, and The Leopard, Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa's novel about Sicily. How about you?

2018 (**=favorites)

Fire from Heaven (Alexander the Great trilogy, Vol 1), Mary Renault

**Men Without Women, Haruki Murakami

A Sort of Life, Graham Greene

**From the Holy Mountain: A Journey in the Shadow of Byzantium, William Dalrymple

Artificial Respiration, Ricardo Piglia

**The Diaries of Emilio Renzi, Vol 1: The Formative Years, Ricardo Piglia

The Sense of Sight, John Berger

Transit, Rachel Cusk

**The Miracle Cures of Dr. Aira, Cesar Aira

Quarantine, Jim Crace

**Warlight, Michael Ondaatje

Memorial, Alice Oswald

In the Night of Time, Antonio Munez Molina

Bel Canto, Ann Patchett

Unreasonable Behavior, Don McCullin

**Barbarian Days: A Surfing Life, William Finnegan

An Odyssey, Daniel Mendelssohn

No Time to Spare, Ursula LeGuin

**Home Fire, Kamila Shamsie

Aeneid Book VI, Seamus Heaney

The Cure at Troy, Seamus Heaney

The Foliate Head, Marly Youmans

**Burial at Thebes, Seamus Heaney

**The Odyssey, Robert Fagles, translator (rereading with friends, each a different translation)

December 24, 2018

A Byzantine Christmas

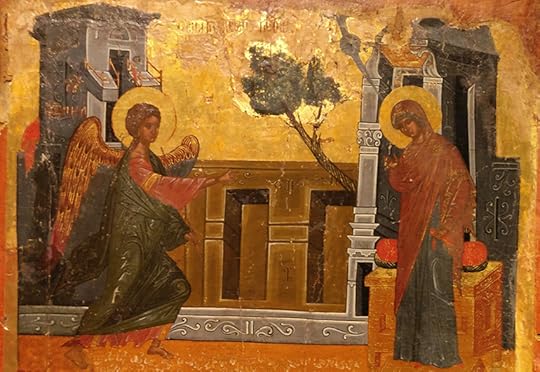

An Annunciation, second half of 16th C.

The Benaki Museum, in Athens, houses an immense personal collection of antiquities and Byzantine art, especially icons from the so-called Cretan School. Although I'm very interested in Byzantine art, I'm starting from a point of knowing very little about it -- it's our trips to Rome, Sicily, and now Greece that have made me want to learn. I apologize that the photographs aren't better - the combination of the lighting in the galleries and gold leaf on the icons made it really hard to avoid reflections and shine.

Annunciation, by Emmanuel Tzanfornaris, late 16th-early 17th C.

For today, though, I'm just going to post some of the icon paintings we saw at the Benaki that had an Advent or Christmas theme, and include a paraphrase of online articles about what this Cretan School actually was.

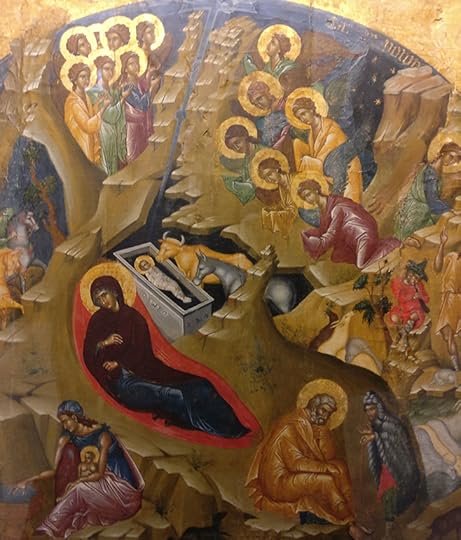

The Volpi Nativity, 1st quarter of 15th C. The baby is laid in a strange coffin-like box with a reclining Virgin and pensive Joseph -- but who are all those other characters?

Virgin and Child Enthroned, by Andreas Ritzos, one of the most famous Cretan painters. Second half of 15th C.

In Greece we repeatedly encountered bitter accounts and evidence of the destruction of Christian art, architecture, and artifacts that occurred when the cities of the Byzantine empire fell to the Ottoman Turks. After Constantinople was taken over by the Turks in 1453, a number of Byzantine scholars and artists fled, especially to Venice.

"The émigrés were grammarians, humanists, poets, writers, printers, lecturers, musicians, astronomers, architects, academics, artists, scribes, philosophers, scientists, politicians and theologians. They reintroduced the teaching of the Greek language to their western counterparts, and brought with them Classical texts that were printed on the first printing presses for Greek books in Venice in 1499. Orthodox Christians in other parts of the Eastern Mediterranean gave money to endow monasteries and allow them to continue their work. One major example was on the island of Crete, which was occupied by the Venetians from 1204 until 1669, and was one of the last Greek islands to have fallen to the Ottoman Turks. The Cretan School of icon-writing became the predominant force in Greek painting during the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries, and helped to supply the demand for Byzantine icons throughout Europe. The Cretan artists developed a particular style of painting under the influence of both Eastern and Western artistic traditions and movements; the most famous product of the school, El Greco, was the most successful of the many artists who tried to build a career in Western Europe, and also the one who left the Byzantine style farthest behind him in his later career.

By the late 15th century, Cretan artists had established a distinct icon-painting style, distinguished by "the precise outlines, the modelling of the flesh with dark brown underpaint and dense tiny highlights on the cheeks of the faces, the bright colours in the garments, the geometrical treatment of the drapery, and, finally the balanced articulation of the composition", "sharp contours, slim silhouettes, linear draperies and restrained movements". (Wikipedia:the Cretan School, and Patrick Comerford, The Cretan School of Icons and its Contribution to Western Art.)

With these beautiful, enigmatic images, I want to wish a Merry Christmas to all of you!

Adoration of the Magi, attributed to Ioannis Permeniatus, first half of 16th century

December 17, 2018

Origins of an Obsession

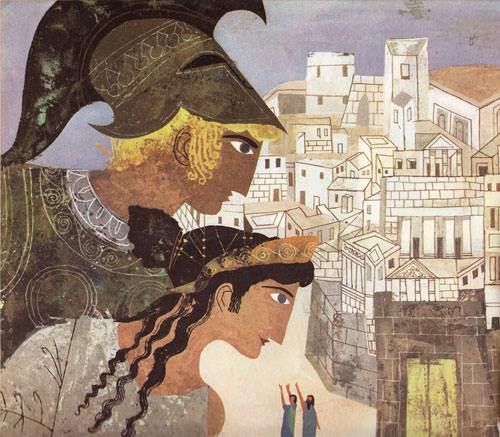

Apollo and Athena look down on Troy. Alice and Martin Provensen, The Iliad and the Odyssey (Golden Books)

When I was 8, my parents went on a trip to Kentucky, leaving me in the care of my maternal grandparents, who lived downstairs. I don't remember the circumstances; it must have had to do with my father's work, but this trip was exceptional. Except for visiting my father's dying brother in Florida, fifty years later, it was the only time my mother ever flew on an airplane. She was asthmatic at a time when that disease was not well-controlled, and travel was difficult and anxiety-provoking for both my parents. But that one time, they went. I remember feeling confused and nervous, but trying to be good about it. And I remember when they came back home, both because I was very glad to see them, and because my mother brought me a special present that she had found in a city bookstore in Louisville.

It was The Golden Book of Myths and Legends, illustrated by Alice and Martin Provensen, and I was instantly captivated. The book also included the tales of Beowulf, the Battle of Roncevaux, Tristram and Iseult, Rustem and Sohrab, and Sigurd of the Volsungs, but the entire first half was devoted to the Greek myths. I pored over the paintings: Prometheus stole fire from heaven; Theseus faced the Minotaur in the Cretan labyrinth; a helmeted Jason fled with the Golden Fleece, Daedalus stood on a rooftop studying the birds. I was already a good reader, but my mother helped me with the text and unfamiliar words, and together we studied the pictures and talked about the stories. She had studied Greek art in college, and showed me how the illustrators had adapted the style of ancient vase paintings to a modern idiom. She pulled out her copy of Bullfinch's Mythology when I wanted to know more. Although she didn't know how to read Greek, she taught me to recite the letters of the alphabet, and how to write the characters, and we talked about the Greek origins of many English words.

That Christmas, my parents gave me the Provensen's illustrated Iliad and Odyssey. My mother read it to me when I was sick in bed, and again we pored over the pictures -- these were even more closely linked to Greek vase paintings. She talked to me about the use of positive and negative space; I traced and copied some of the illustrations. The story and the characters got under my skin and into my head, and stayed there, while the gods and goddesses, in profile, looked down on the warring camps of Greeks and Trojans from the heights of Mt. Olympus, their feuds and jealousies mirroring the behaviors of people I knew. I identified most with grey-eyed Athena, who remained above the love-quarrels by staying a virgin, and encouraged wisdom, intellect, and music as well as being the patron goddess of the Athenians. We read the story countless times, and in spite of my preference for Athena, I always went against her and rooted for the Trojans, knowing it was fated for them to lose, but somehow hoping that my wishes would make the story turn out differently. It was the same when I got to university and enrolled in ancient Greek classes, and, in the second semester, opened my student edition of Homer to the first words of the Iliad. And it's been the same every time since, in every translation: the inevitability of defeat battling with my desire for a different result, as if human fate itself could be held suspended or reversed by the force of my own free will. Much later, I would come to see that the Greeks themselves were concerned with the same questions of fate vs free will, and that it would play a large part in the development of their tradition of tragic drama and exert a profound influence on Christianity, and later western drama and philosophy.

I can't explain the hold that this art and this particular story has had on me, all my life; all I can do is trace it back to its origin. I became a classics major; I almost decided to teach art history or become a conservator of antiquities, but instead became a graphic designer and artist - and I'm convinced to this day that my early study of those vase paintings, and their positive-negative harmony, and the beautiful carved inscriptions of perfectly-balanced Greek letters, had a lot to do with why I became a designer and careful typographer myself, and why my own art has always been concerned with line, and with volume.

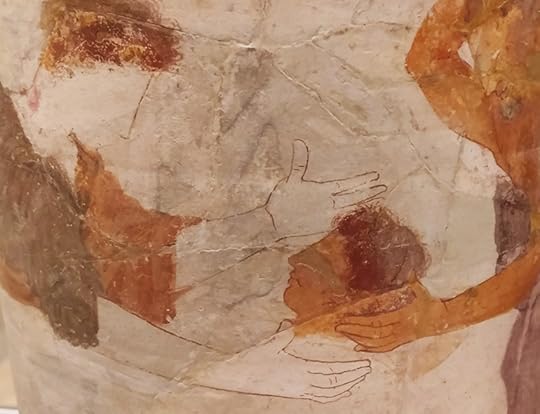

Laying Out of a Young Man in the Family Circle, Attic Greek, around 400 BC, white-ground polychrome lechythos (Altes Museum, Berlin)

One day shortly before J. and I left for Greece in mid-November, I began thinking about my mother, and my eyes suddenly filled with tears: how she would have loved to go! Yet in 83 years, she never left the continental U.S. and, like many people in my travel-averse family, hardly ever traveled far from her rural home. But she traveled the world vicariously through me, and through books and the pages of The New Yorker and New York Times, often sending me clippings about some new archaeological discovery. Now, all these years later, I was finally going there, and she was gone from the earth; I wouldn't even be able to tell her what I saw. That particular morning, the prospect seemed unbearable, and I wept. But later, while packing, I decided to wear one of her silver bracelets throughout the trip, and I spontaneously pulled out a favorite black-and-white photograph of her, and stuck it in the back of my sketchbook. When we arrived in Athens, I put the photograph on the table in front of the mirror, and went up to the roof, and saw the Acropolis and the Parthenon for the first time. She was there with me, then, and in my heart, I told her all about it.

December 14, 2018

Home from a Journey

Dear Readers, apologies for my long silence. I've been away on a trip to Greece, a place I've wanted to visit for an entire lifetime. As the title of this blog implies, I've felt a personal identification with ancient Greece and its stories, gods and goddesses, art and thought. It's what I studied when I was young, and for a while I thought I'd either be a ancient art history professor or a conservator of antiquities. That's not how my life turned out, and part of the reason for this trip was to revisit that earlier self, as well as the place, and see what I thought from a different point in life.

It was a marvelous journey, filled with surprises and adventures not only in the cities of Athens and Thessaloniki, but in the mountains of northern Greece; and not only concerned with ancient history and art, but also with a quest to see and learn more about the Byzantines. We were gone for sixteen days, and started our travels in Berlin, where we visited one of the best collections of ancient Greek vases and sculptures in the world, at the Altes Museum, as well as going to the Reichstag, taking long walks, trying to stay warm (it was almost as chilly as Montreal) and eating some excellent German food. Then we flew to Athens, where we began and ended our travels in Greece.

I have a lot I want to write about, but it's going to have to wait a bit because...Christmas...and singing, and friends and family, as well as some significant responsibilities here at home. The jetlag in this direction, back home, was really fierce, and I've been really busy besides. Today is the first day since returning a week ago that I've had any time to work on my pictures and videos, and I did get them transferred to my computer. So, eventually, there will be more to share here.

Travel completely engages me when I'm there, and then feels almost unreal when return to my own space. And yet, flight makes those sudden shifts in reality possible. I wouldn't call it disorienting, per se, but it is certainly strange to find yourself inhabiting an image like the one above, that you've seen in countless sources, from textbooks to travel videos. We don't go on tours but figure out our itinerary and plans completely from scratch, and unexpected things happen, so during the trips we always feel like we're very heads-up, paying sharp attention; there's a high level of intensity. I try hard to really be in a place -- to feel it and engage with it with all my senses as well as my mind -- and not just be a person behind a camera, capturing moments like trophies. It takes time to think about a significant journey and to see what I've learned and how it has changed me; I'm doing that now and will be doing it for quite a long time. And I already want to go back. There were good reasons why, as a young girl, Greece got under my skin. I see that better now, and am glad I wasn't disappointed by being face to face with the real thing. Yet I also see that I made the right decision to live a less linear and more personally creative life; it was a better fit with who I really am, but in many ways, it has been a reflection of the values and ideals that attracted me to the Greeks in the first place. As a woman, I'm lucky I live now, though, instead of back then.

So, more to come, soon.