Elizabeth Adams's Blog, page 20

May 30, 2020

Hermit Diary 27: A Summer Already Ablaze

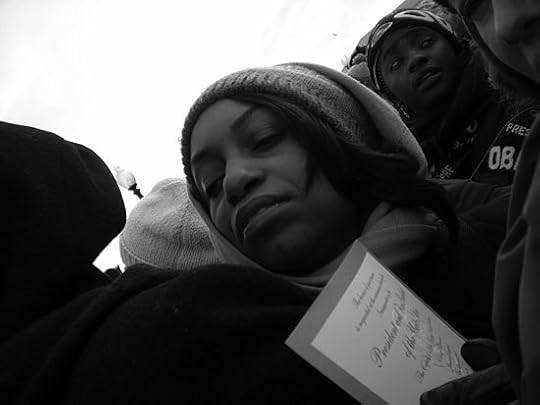

At Barack Obama's inauguration, Washington D.C., January 2009

The year was 1968. On April 4, Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated. Two months later, in June, Robert F. Kennedy, the U.S. senator and former attorney general who had campaigned for civil rights his entire career, was also killed by an assassin. The Vietnam War was raging; the country deeply divided, angry, and hopeless. After Dr. King died, riots erupted in all the major cities, and continued. Like 2020, 1968 was also an election year. The Democratic convention, held in Chicago in August, was the scene of a massive clash between 10,000 anti-war demonstrators and 23,000 National Guardsmen, called in by Chicago Mayor Richard Daley. Later, the independently-headed "Walker Report," appointed to study and report on what had happened, said:

"...(there was) unrestrained and indiscriminate police violence on many occasions, particularly at night. That violence was made all the more shocking by the fact that it was often inflicted upon persons who had broken no law, disobeyed no order, made no threat. These included peaceful demonstrators, onlookers, and large numbers of residents who were simply passing through, or happened to live in, the areas where confrontations were occurring."

“Individual policemen, and lots of them, committed violent acts far in excess of the requisite force for crowd dispersal or arrest. To read dispassionately the hundreds of statements describing at firsthand the events of Sunday and Monday nights is to become convinced of the presence of what can only be called a police riot.”

I was 16 then and already a committed activist; I remember it all very well. The summer of 1968 was when it all boiled over, but the violence continued right through 1970, when the Kent State Massacre -- in which four innocent students were shot and killed -- finally seemed to mark a turning point in the protests against the war. Those of us who were alive then cannot forget Richard Nixon's unpalatable policies, and how his rightwing, law-and-order rhetoric fueled these confrontations -- but Donald Trump is orders-of-magnitude worse.

In spite of all that has happened since, no period of time I've experienced has come close to matching the frustration, anger, tension, fear, suffering, and deep sadness of those years, until now. 2020 is going to go down in history too. And it's going to be a long, hot summer.

Fifty years, and it feels like white people have learned nothing. Nothing. When are we going to wake up and make not only the systemic changes that need to happen, but start to address the wrongs that have been done? Will there EVER be a Truth and Reconciliation process in the United States? I very much doubt it, not with governments like the present one, which encourage and promote hatred, seek to turn their own people against each other, and have empowered and emboldened right-wing white supremacists, fascists, and the most conservative elements within police, military, and border-control forces. But the roots of racism in America run so deep that not even a black president of impeccable character and eloquence could make significant inroads against it. Now, not only do we have police killing blacks on the streets, and a justice system stacked against them, we have black and ethnic minority people dying in hugely disproportionate numbers from the virus, while they also serve in a disproportionate number of low-paying and dangerous jobs in health care and the service sectors -- not to mention the countless other injustices to which they are subject.

Here in Canada, I've observed the Truth and Reconciliation process with the indigenous community. Although America has perpetrated even more injustices, including genocide, against its native people, this did not feel like "my" issue when I moved here; because of the time when I grew up, I was more concerned, more familiar, and more invested in the struggles for civil rights, women's rights, peace and nuclear disarmament, gender equality, and the rights of immigrants and religious and ethnic minorities -- all of which had been major issues in the United States during my lifetime. But I have seen the painful steps toward truth-telling and reconciliation here, as well as in South Africa, and I believe that this is the ONLY way to begin to redress the wrongs that have been done, and to bring a society into greater understanding.

Yet in Canada, in spite of believing that we're better than our neighbors to the south, we have our share of racism and hatred, especially directed against Muslims and Jews. Just this week, in one of the worst attacks in recent memory, a synagogue here in Montreal was violently ransacked, its religious objects desecrated -- a Torah had been cut up and stuffed into a toilet -- the floors covered in red paint, and the walls with antisemitic graffiti.

Meanwhile, the poor, and people of color and of ethnic minorities are dying at higher rates of COVID-19, while they fill a greater number of poorly-paid service and health care jobs. The same Quebec government which recently threw out three years of immigrant applications just had the gall to start a new fast-track program for immigrants who are willing to come here and work in the deplorable care homes for the elderly, where the virus has spread like wildfire, resulting in 80% of the deaths in the province. The message is clear: we didn't want you before, but now we need you to take care of us, so we'll make you a deal.

We white people of conscience have no choice: we have to stand for justice and against racism in all of its forms, against violence, against oppression, and for equality for all people regardless of race, religion, gender, or sexual preference. And you know what? It is not the job of black people, or Muslims, or Jewish people, Asians, Arabs, or any other minority group, to educate us about why their lives matter, and what needs to be done. It's our job, and we had damn well better get on with it.

May 29, 2020

Hermit Diary 26: Down to the Sea in Ships

This entry is cross-posted from Daily Bread, the blog of Christ Church Cathedral, Montreal. The painting is Dutch Fishing Boats in a Storm by J.M.W.Turner, 1801.

They that go down to the sea in ships, that do business in great waters;

These see the works of the Lord, and his wonders in the deep.

For he commandeth, and raiseth the stormy wind, which lifteth up the waves thereof.

They mount up to the heaven, they go down again to the depths: their soul is melted because of trouble.

They reel to and fro, and stagger like a drunken man, and are at their wit's end.

Then they cry unto the Lord in their trouble, and he bringeth them out of their distresses.

He maketh the storm a calm, so that the waves thereof are still.

Then are they glad because they be quiet; so he bringeth them unto their desired haven.

-- Psalm 107: 23-30 (KJV)

Psalm 107, appointed for Evening Prayer today, is a true poem, immensely satisfying not only for its message of deliverance from various sorts of trouble but also for its use of language. In sections of about 8 lines each, we hear about four different groups of people in danger: “Some wandered in desert wastes / finding no way to an inhabited town”; “Some sat in darkness and in gloom / prisoners in misery and in irons;” “Some were sick[through their sinful ways / and because of their iniquities endured affliction.” Finally, we meet the sailors: “Some went down to the sea in ships / doing business on the mighty waters.”

Each of these four groups is, or becomes, lost in some way, which the psalmist describes, but by the end of the eight lines, the Lord has led them out of their trouble into safe haven. The whole psalm is wonderful in its repetition and vivid description, but the best-known lines are those quoted above, about sailors who go to sea, only to be tossed and terrified by winds and waves, but are saved when the Lord calms the storm and brings them safely home.

The King James Bible gave us the familiar English wording: “They that go down to the sea in ships.” But throughout the centuries since the psalm was written, to the life of Jesus of Nazareth, to the era of exploration, and right up to the middle of the 20th century, when air travel became common, the basic concept resonated. People have always known what it means to go to the sea in ships, face the intense danger that claims many lives, and they’ve always been grateful for reaching safe harbour.

It’s not surprising that Henry Purcell (1659-1695), living in a great age of seafaring, felt compelled to set these words to music; his is a chamber music setting for bass, alto (or counter-tenor), two violins and organ.

But the setting better known to Anglicans today is the one linked above, written by Herbert Sumsion (1899-1995). It was brought to our cathedral choir two years ago by Rob Hamilton, co-interim-music director, who remembered it fondly from his own days as a boy chorister. Most of us had never sung it before, but we too had fun with its evocation of calm seas, then the storm, and the sailors “staggering like drunken men” before the calm is restored again.

I asked our music director Jonathan White for some additional insights about the composer and what might have influenced him to write this piece.

“Sumsion was heavily embedded in the English choral tradition,” he told me, “spending practically his entire musical life at Gloucester Cathedral, all the way from being a chorister as a child to being Director of Music for almost 40 years. This is a late work from his career -- 1979 -- and we know it was written as a commission. He may well have known Purcell’s own setting of the text as this was also a period of ‘rediscovery’ of older music. Sumsion was well acquainted with composers like Elgar, Howells, Vaughan Williams, Holst. Howells and his circle were central in reviving the Renaissance composers – Byrd, Tallis, Gibbons etc – and Purcell likely also formed part of this. Britten and his circle were very interested in Purcell, for example.”

Jonathan went on to say that he didn’t know of any other Sumsion anthems quite as dramatic as this one:

“It’s a very evocative anthem, with a rippling accompaniment that is clearly designed to convey the ebb and flow of the waves, that follows a great arc, building to a dramatic climax before ebbing away again. This, of course, is a trajectory that you can see in many Renaissance works (think of the Tallis O sacrum convivium that does just that, the Palestrina Agnus Dei from the Missa brevis…) but I wouldn’t necessarily say it’s directly connected to that period of music – it could just be a coincidence.”

As I listened to Sumsion’s anthem again, I thought about how we often forget that Montreal was once a seafaring city, except maybe when we attend a concert at the Chapelle Notre-Dame-de-Bon-Secours in the Old Port -- once known as the “seafarers’ church” -- and see all the handcarved wooden ship models hanging from the ceiling: offerings of thanksgiving made by sailors. A great many of our ancestors, including mine, arrived on the shores of the New World by boat, often enduring horrendous trips during which survival was not at all certain. Sometime, visit the Marguerite Bourgeoys Museum next to the Chapelle Bon-Secours, and listen to the recording of a letter written during a terrifying voyage from France to the nascent colony of Ville-Marie around 1653 (four years before Purcell was born.)

But you don’t need to be a seafarer to find a contemporary resonance in the psalm and the anthem. The arc of the text and music also mirror the uncertain journey we’re going through today -- and express clearly how grateful we will be if and when the waters feel calm again, and we’re home, on dry land, in “our desired haven.”

May 26, 2020

Hermit Diary 25: Susan Rothenberg and the essence of things

Susan Rothenberg, a very fine painter, died last week at the age of 75. I knew of her but didn't know the breadth of her work particularly well; this video touched me. Some of the animal images remind me of Lascaux and other cave paintings, and many of them have a quality -- like those prehistoric drawings -- that speaks to me in the present moment.

She said in a 2005 interview, “If you don’t know what you’re doing out here in the South West, in this kind of isolation, if you don’t understand that you’re supposed to have work and a purpose to every day, you’re going to float off into the stratosphere or move very quickly back to an urban center.”

Gemini.

What I like especially about her work is that all of it feels closely informed by drawing. She must have drawn all the time. She made prints, she painted. But all of these disciplines informed the others, and you can see it in the finished works. There's a lot to learn from here.

The American art critic and curator Robert Storr said this about Rothenberg's drawings:

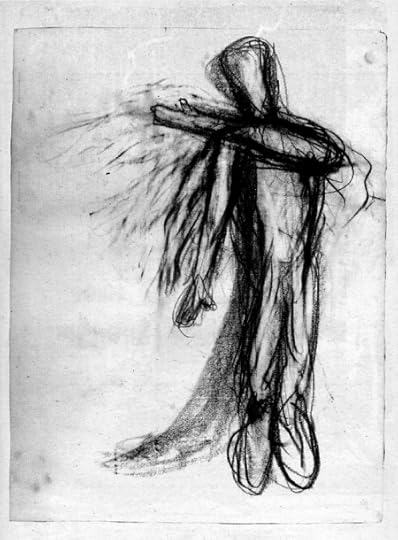

"...fundamentally, drawing is as much a matter of evocation as it is of depiction, of identifying the primary qualities of things in the world and transposing them without a loss of quiddity. This at any rate is what drawing has been for Rothenberg."

Untitled, pencil on paper, 1983

May 19, 2020

Hermit Diary 24: Remembering Patrick Wedd

A year ago today, the music world lost a great man and musician, Patrick Wedd, who had retired a year before as organist and music director at Christ Church Cathedral Montreal but whose reputation extended well beyond Canada. It was a personal loss for me, too: in addition to feeling incredibly fortunate to have sung with him for more than a decade, and to have had the privilege of sitting near the organ bench watching him play, Patrick was a dear friend.

Nick Capozzoli, our present assistant organist, had worked under Patrick for several years and became interim co-music director during the year after Patrick's retirement. Nick is one of the finest organists of his generation, following in Patrick's footsteps. As a tribute to his teacher and mentor, Nick put together this video, published today. The music is one of Patrick's favorite hymns, being sung in the crowded cathedral during his memorial service, and the photographs of Patrick and our choir were taken on several occasions by the diocesan photographer, Janet Best. At the end, our soprano section takes off in a descant written by Patrick for the final verse of the hymn.

--

On Thursday, Donald Hunt, former assistant organist here in Montreal, and now director of music at Christ Church Cathedral Victoria, will present Olivier Messiaen's l'Ascension as a live-streamed concert in memory of Patrick Wedd. The movements will be interspersed with meditations on the scriptural verses to which they refer, by several of Patrick's clerical friends and colleagues. The links for that are here: To tune in live: https://www.facebook.com/MusicCCCVictoria/live_videos/

To watch on demand after the live stream: https://vimeo.com/user12422383

--

The worst part about the current crisis for me personally, other than intense sadness about the loss of life worldwide, has been the loss of making music with others through singing. Added to that is the growing awareness that, because singing is one of the most dangerous activities, it may be a very long time before we can return to it. I was already fearing that I might be getting toward the end of my time as a choir singer, though I waffle back and forth about that. Now, in my worst moments, I wonder if I will ever return to it, after a lifetime of being in church and cathedral choirs.

However, our choir has just produced their first virtual-choir video, and we're working on two more which I'll share with you here when they're completed. It's a bizarre and quite self-conscious process, where you record your own part, solo, while listening to a backing track on headphones. The tracks were then assembled by our music director, Jonathan White, and the resulting video recording sounded remarkably like us -- the way our own particular voices blend and sound together. This video was played during the cathedral's Zoom service last Sunday morning, and a number of parishioners told me they were very moved to hear and see the choir again.

Patrick was one of the least technological people I've known in my life, but I know he would have been delighted. His focus was always on producing the best music possible and sharing it widely. He'd be happy to know that we're finding new ways to continue singing, continue performing, and bringing this tradition of liturgical music to people at a time when it particularly matters.

May 13, 2020

Hermit Diary 23: Work

Vlatadon Monastery, Thessaloniki, Greece

[This essay is cross-posted from "Daily Bread", the blog of Christ Church Cathedral, Montreal.]

In this strange period we’re experiencing, time itself seems to have changed. The indistinguishable days go by in a blur, without the structure of our former schedules. Some of us are out of work; others are adapting to working in completely different ways; suddenly we’re faced with tasks we’ve avoided for years, or spending huge amounts of time getting food and cooking it. Ironically, although we all supposedly have “more time,” it’s often hard to feel like we’re getting much done. It’s harder to focus, harder to stick to a routine, harder to make decisions and work effectively. Sometimes it’s even hard to sleep, or get out of bed in the morning…and there seems to be no end to this in sight.

Today, in Paul’s First Letter to the Thessalonians, we find what seems to be a difficult message. The Apostle asks the brothers and sisters of the early Christian community to “acknowledge those who work hard…to hold them in highest regard because of their work.” Frankly, we don’t even need to hear this from Paul in order to feel guilty, because we’ve lived for years in a society that constantly dins into us the value of work and accomplishment, even to the point where we are defined by those things.

But as I looked deeper, I decided this passage could be read differently, and that it contains hope and encouragement for us today.

Please come along with me to Thessaloniki for a few minutes. In 2018, my husband and I visited that fascinating city in northeastern Greece, on the Aegean, not far from the Turkish border. Thessaloniki feels eastern. It’s filled with ancient Orthodox churches built during the Byzantine period; monks and priests stride through the streets in their black robes, and across from the Church of Hagios Demitrios, where the martyr-saint Demitrius is buried, are icon-painting workshops and shops glittering with gilded icons and mosaics, satin vestments, brass crosses, candlestands and candelabras, Eucharistic vessels, incense and prayer beads, and holy books. The scents of hot wax and myrrh pervade the churches; worshippers whose feet are muffled by the wall-to-wall rugs make the rounds of the sanctuaries, kissing the icons, crossing themselves, praying before the relics of martyrs, and lighting handmade beeswax candles that range from tiny tapers to pillars four feet tall.

When Paul arrived here two millenia ago, Thessaloniki was already a large city filled with people of many different races and cultures as befitted its location at the crossroads of east and west. It was also the seat of the Roman governor of Macedonia. The intensity of Paul’s preaching led to the birth of the city’s Christian community. After several weeks, his presence created such a disturbance that he and his friend Silas were forced to escape at night, climbing down the city walls of Thessaloniki at the exact place where the Vlatadon Monastery was later built.

The Vlatadon monastery chapel.

Jonathan and I visited the monastery on a beautiful bright day. The remains of the ancient city walls, circling the top of an imposing hill above the sea, are just beyond the grounds of the monastery, which is still home to a community of monks. There’s a small garden and orchard; pens for chickens, geese and peacocks; a goat or two; and an ancient chapel with Byzantine frescoes on the dimly-lit walls, the unrestored figures defaced with hammer marks made by the Ottoman invaders who tried to destroy all human images.

Just below and to the east, there’s a spring where Paul supposedly stopped to drink, and it’s still a place of pilgrimage. I stood and looked out at the same view of the Aegean that Paul must have seen, and walked over to touch the old bricks and rocks of the original city wall. At such moments, history comes very close.

In his letter to the nascent community, Paul not only appreciates those who “work hard,” but goes on to advise these early Christians to encourage and help one another, avoid division and blame, and try to do what is good for their own community, but also for others.

I think Paul is talking here not only about the hands-on work of providing food and shelter and other necessities, but the work of being and building community. And it strikes me that during this most unusual time, that is the work to which we are being called, too. Many people have spoken about how our cathedral’s Zoom services have, paradoxically, brought us closer to one another: we see our fellow parishioners, and the clergy, face-to-face and in our own homes; we’re meeting people we didn’t know, deepening existing relationships, finding new ways of worshipping and communicating, and gathering in small groups to talk and share, support one another, and learn. Many of us are doing this same “work” in a more secular context, too, as we explore new ways of bringing far-flung family and friends together, and do collaborative projects.

If Paul and Silas were forced to flee Thessaloniki under cover of darkness, we can be sure that life was not easy for their followers. As many have noted, there are parallels between the early Christian communities, for whom gathering was forbidden and fraught with danger, and our present predicament as worshiping Christians who cannot meet. Paul’s advice seems meant for us too: “encourage the disheartened, help the weak, be patient with everyone.” And he reminds us not to look inward exclusively, but to see the needs outside our own community — as we certainly have been doing — when he writes: “strive to do what is good for each other and for everyone else.” Regardless of how long our isolation lasts, perhaps we might worry less about how much work we’re getting done, in the traditional sense, and think more about building relationships, and the strength and resilience of our community, for whatever lies ahead.

Hermit Diary 25: Work

Vlatadon Monastery, Thessaloniki, Greece

[This essay is cross-posted from "Daily Bread", the blog of Christ Church Cathedral, Montreal.]

In this strange period we’re experiencing, time itself seems to have changed. The indistinguishable days go by in a blur, without the structure of our former schedules. Some of us are out of work; others are adapting to working in completely different ways; suddenly we’re faced with tasks we’ve avoided for years, or spending huge amounts of time getting food and cooking it. Ironically, although we all supposedly have “more time,” it’s often hard to feel like we’re getting much done. It’s harder to focus, harder to stick to a routine, harder to make decisions and work effectively. Sometimes it’s even hard to sleep, or get out of bed in the morning…and there seems to be no end to this in sight.

Today, in Paul’s First Letter to the Thessalonians, we find what seems to be a difficult message. The Apostle asks the brothers and sisters of the early Christian community to “acknowledge those who work hard…to hold them in highest regard because of their work.” Frankly, we don’t even need to hear this from Paul in order to feel guilty, because we’ve lived for years in a society that constantly dins into us the value of work and accomplishment, even to the point where we are defined by those things.

But as I looked deeper, I decided this passage could be read differently, and that it contains hope and encouragement for us today.

Please come along with me to Thessaloniki for a few minutes. In 2018, my husband and I visited that fascinating city in northeastern Greece, on the Aegean, not far from the Turkish border. Thessaloniki feels eastern. It’s filled with ancient Orthodox churches built during the Byzantine period; monks and priests stride through the streets in their black robes, and across from the Church of Hagios Demitrios, where the martyr-saint Demitrius is buried, are icon-painting workshops and shops glittering with gilded icons and mosaics, satin vestments, brass crosses, candlestands and candelabras, Eucharistic vessels, incense and prayer beads, and holy books. The scents of hot wax and myrrh pervade the churches; worshippers whose feet are muffled by the wall-to-wall rugs make the rounds of the sanctuaries, kissing the icons, crossing themselves, praying before the relics of martyrs, and lighting handmade beeswax candles that range from tiny tapers to pillars four feet tall.

When Paul arrived here two millenia ago, Thessaloniki was already a large city filled with people of many different races and cultures as befitted its location at the crossroads of east and west. It was also the seat of the Roman governor of Macedonia. The intensity of Paul’s preaching led to the birth of the city’s Christian community. After several weeks, his presence created such a disturbance that he and his friend Silas were forced to escape at night, climbing down the city walls of Thessaloniki at the exact place where the Vlatadon Monastery was later built.

The Vlatadon monastery chapel.

Jonathan and I visited the monastery on a beautiful bright day. The remains of the ancient city walls, circling the top of an imposing hill above the sea, are just beyond the grounds of the monastery, which is still home to a community of monks. There’s a small garden and orchard; pens for chickens, geese and peacocks; a goat or two; and an ancient chapel with Byzantine frescoes on the dimly-lit walls, the unrestored figures defaced with hammer marks made by the Ottoman invaders who tried to destroy all human images.

Just below and to the east, there’s a spring where Paul supposedly stopped to drink, and it’s still a place of pilgrimage. I stood and looked out at the same view of the Aegean that Paul must have seen, and walked over to touch the old bricks and rocks of the original city wall. At such moments, history comes very close.

In his letter to the nascent community, Paul not only appreciates those who “work hard,” but goes on to advise these early Christians to encourage and help one another, avoid division and blame, and try to do what is good for their own community, but also for others.

I think Paul is talking here not only about the hands-on work of providing food and shelter and other necessities, but the work of being and building community. And it strikes me that during this most unusual time, that is the work to which we are being called, too. Many people have spoken about how our cathedral’s Zoom services have, paradoxically, brought us closer to one another: we see our fellow parishioners, and the clergy, face-to-face and in our own homes; we’re meeting people we didn’t know, deepening existing relationships, finding new ways of worshipping and communicating, and gathering in small groups to talk and share, support one another, and learn. Many of us are doing this same “work” in a more secular context, too, as we explore new ways of bringing far-flung family and friends together, and do collaborative projects.

If Paul and Silas were forced to flee Thessaloniki under cover of darkness, we can be sure that life was not easy for their followers. As many have noted, there are parallels between the early Christian communities, for whom gathering was forbidden and fraught with danger, and our present predicament as worshiping Christians who cannot meet. Paul’s advice seems meant for us too: “encourage the disheartened, help the weak, be patient with everyone.” And he reminds us not to look inward exclusively, but to see the needs outside our own community — as we certainly have been doing — when he writes: “strive to do what is good for each other and for everyone else.” Regardless of how long our isolation lasts, perhaps we might worry less about how much work we’re getting done, in the traditional sense, and think more about building relationships, and the strength and resilience of our community, for whatever lies ahead.

May 3, 2020

Hermit Diary 22: Forsythia

Parc Lafontaine, Montreal, May 1 2020, gouache and pencil in Moleskine pocket sketchbook

Forsythia

It caught my eye a while ago, lit up

against the gloom of the woods

in the corner of a wild field,

the pulsing color of caution.

And now that I have spent a little time

on this stone wall watching its fire

flare out of the earth

I begin to think about the long chronicle of forsythia

how these same flowers have blazed

through the centuries,

roused from the ground by the churning of spring.

I would rather not look around the next

corner of the year to see how this will die,

its lights going out,

its bare, arcing branches

waving like whips in the bitter wind.

So I sit facing the past,

letting my feet dangle over the wall,

beating time against stone with my heels

as the long gray clouds roll over me.

Remember how Arnold by the Channel

thought of Sophocles who must have heard

the same shore-sounds long ago,

walking by the edge of the Aegean?

Well, I am holding in the palm of my thoughts

all the others who once were stopped,

like me, by this brightness,

this sulfuric cry for help:

women in tunics, women gathered by a well,

men in feathers, men swimming by a river,

all speaking languages I will never know,

saying the different words for its color

as I feel the syllables of yellow form in my mouth

and hear the sound of yellow fill the morning air.

-- Billy Collins

April 27, 2020

Hermit Diary 21: A drawing

In real life, it took about fourteen minutes to do this fountain-pen drawing of objects on the top of my desk: a miniature orchid in a Wedgewood pot, a dish of seed pods, pine cones and a snail shell, jars of brushes and a feather. I hope you'll enjoy watching it take shape on the page in an abbreviated version. The final drawing is shown at the end.

It's kind of odd to view the process speeded-up, because when I draw everything slows down a great deal; time barely moves, and I'm sure my breathing and heart rate slow too. However, I didn't think anyone would want to sit through nearly a quarter of an hour of video, even though it would convey the contemplative aspect much better. On the other hand, I've always been fascinated by time-lapse photography and condensed footage, so there's that too.

I'll try this with some other art media in the future. Maybe I can get a slightly better angle next time that shows the whole page straight-on.

April 24, 2020

Hermit Diary 20: The Martyrs' Call to Us

Cross-posted from Daily Bread, the blog of Christ Church Cathedral, Montreal

Today is set aside by the Anglican Church in remembrance of the Christian martyrs of the 20th (and 21st) centuries. The book For All the Saints in our sacristy gives short biographies of just a few modern Christian martyrs: the Burmese martyrs of the 1940s; European Christian martyrs against Nazism; African Christian martyrs killed during independence movements; North and South American martyrs for racial and social justice. One of the suggested readings for today is an address given by Archbishop Oscar Romero of El Salvador (pictured at left) shortly before he died in 1980. I’d like to quote and reflect upon Romero’s words because I think they have relevance for us today. He begins:

Today is set aside by the Anglican Church in remembrance of the Christian martyrs of the 20th (and 21st) centuries. The book For All the Saints in our sacristy gives short biographies of just a few modern Christian martyrs: the Burmese martyrs of the 1940s; European Christian martyrs against Nazism; African Christian martyrs killed during independence movements; North and South American martyrs for racial and social justice. One of the suggested readings for today is an address given by Archbishop Oscar Romero of El Salvador (pictured at left) shortly before he died in 1980. I’d like to quote and reflect upon Romero’s words because I think they have relevance for us today. He begins:

"I am going to speak to you simply as a pastor, as one who...has been learning the beautiful but harsh truth that the Christian faith does not cut us off from the world but immerses us in it, that the Church is not a fortress set apart from the city. The Church follows Jesus who lived, worked, battled and died in the midst of a city... It is in this sense that I should like to talk about the political dimension of the Christian faith..."

Whether we see the “Church-as-fortress” metaphorically or literally, the coronavirus crisis has forced us out of our cathedral building, and into a different type of relationship as a church community within this city where we live. On our Zoom screens is an array of faces into which we look, and which gaze back at us from our widely-separated homes. Rather than being one body in one place, we are being shown in a new way that we are diverse members of one body.

"Our Salvadoran world is no abstraction. It is a world made up mostly of men and women who are poor and oppressed...it is the poor who tell us what the city is, and what it means for the Church really to live in that world."

Montreal in 2020 is not El Salvador. Most of us would not say that “our world is mostly poor and oppressed” -- but the current health crisis is revealing significant inequalities even in the most developed and wealthiest societies, and between those societies and the much poorer parts of the world. So instead, perhaps we can speak about “the poor and marginalized.”

Some New York State senators recently wrote: “The novel coronavirus has been called a ‘great equalizer. While it is true that anyone can contract the virus and this crisis reaches all of us in some way, it is absolutely not true that the harm it causes is distributed equally."

In Europe and in North America, it is becoming clear that social disadvantage is a predictor of mortality. The reasons include poverty, low-paid jobs in high-risk sectors, less access to health care and supplemental insurance, greater dependence on public transportation, and other inequalities that result in poorer overall health, greater risk of infection and of more critical illness once infected. Some of these people at risk are also living in inter-generational, crowded home situations, where illness is more easily transmitted to the more vulnerable members, as opposed to the living situations of people with higher income, more space, and a wider range of options.

In the UK, and in American cities such as New York and Chicago, statistics already show that people from racial and ethnic minority groups are over-represented among the coronavirus deaths, by significant percentages. We do not yet have similar ethnic/racial statistics for Montreal, but we do know that while the early cases were greater in wealthier parts of the city where people were returning from travels, the virus is now spreading faster in lower-income areas. And the disastrous conditions in our long-term care facilities not only point to disparities in the care of the elderly vs. the regular population, and possibly to ageism in the allocation of funds and oversight, but also to the fact that the people employed to care for our elderly often come from disadvantaged populations themselves and are typically underpaid.

When asked about what has gone wrong in Canadian extended-care system, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said just yesterday that “one of the takeaways about the extended-care situation is that those who are caring for the elderly and vulnerable are, themselves, vulnerable -- often financially-vulnerable people being paid poor wages and living and working in situations that have made them vulnerable to infection.”

And it is not only in facilities for seniors that we are seeing these kinds of issues worldwide: the virus is showing the harsh reality of life in prisons, in homeless shelters or the street, in refugee camps and detention centers.

"...the Church has placed itself at the side of the poor and has undertaken their defense. The Church cannot do otherwise, for it remembers that Jesus had pity on the multitude. But by defending the poor it has entered into serious conflict with the powerful..."

Here in Canada, we are so fortunate to be part of a society with basic protections for all, and, unlike Oscar Romero, we do not have to battle unresponsive political systems that exist only to protect the wealthy and powerful. However, the coronavirus is shining a light on certain dark places where inequalities do exist, and where change needs to occur.

We tend to think of martyrs as people who have died for their faith, but really, they are people who lived for their faith, choosing that path willingly, and inspiring others to do likewise. Remarkable things can often come out of bad situations. On this day of remembrance, perhaps we can consider not only new ways to be a Church community committed to supporting one another, but in how we look outward. We already have a long history of helping the vulnerable and working for change through the cathedral’s Social Service Society, and more recently, the Social Justice and Environmental Action Group, and in our ongoing work and witness for sexual diversity, freedom, and rights. How good it would be if even more of us were inspired by this pandemic to advocate for the elderly, the imprisoned or detained, the homeless, the refugees, and the vulnerable and underpaid workers, and to proclaim all these missions more openly to our city and society.

April 22, 2020

Hermit Diary 19: A Spade

![IMG_20200422_110100[2]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1587627452i/29341221._SX540_.jpg)

Poetry...why does it speak to some of us and not to others? A particular, or peculiar, wiring in the language center of the brain, perhaps, that gains satisfaction and pleasure from words being applied slantwise to ideas, or to forms that have concrete shapes but stand for other things?

Poetry has accompanied me my whole life, maybe because so much of it was read to me when I was young by my grandmother and aunts and mother, maybe also because I grew up with the language of the Book of Common Prayer in my head, plus innumerable lyrics and hymns and songs. Poetry and Music are sisters, and I've turned to them in all the difficult times and sleepless nights of my life. I read a lot of poetry and write very little; I accepted the fact long ago that I'm a prose writer with lyrical tendencies. Over the years I've become an experienced editor of poetry, which requires a different set of skills.

During this crisis I've been pulling one book at a time from my poetry shelves and delving into it over a period of days. Searching might be a better word -- for kindred spirits, and expressions of emotion and lived experience that feel resonant with my own. There aren't going to be literal parallels because this particular crisis is unprecedented, and that's not what I'm looking for. It's more a search for people who also walked in some sort of darkness but faced it squarely, and found meaning in it, or in spite of it.

That's different than looking for naive hope, or painting pretty pictures as a distraction. I'm grateful for all the beauty and hopefulness I see or am able to create, don't get me wrong. As a writer and thinker, I just don't seem to be able to avoid talking or writing or reading about the ignorance, cruelty, heartlessness, and sheer evil that are going on, especially in America; or the risks and sacrifices of the largely anonymous and often poorly paid people providing critical services; or the immense sadness that comes from this massive worldwide loss of life -- life in every sense of the word.

I wish it were different, but I'm not particularly optimistic about the future; we humans don't learn very well from history or our own mistakes, and most of us are primarily selfish and focused on the short-term. Nevertheless, love is always present, and where there's love, we can also find light and hope. Naive liberalism will get us nowhere; the forces arrayed against it are too great, and too entrenched in most of our societies and governments. I think it's actually more hopeful to avoid wishful thinking and instead see things as they actually are -- and find ourselves and our way forward centered within that reality. As Thomas Merton wrote, we need to cultivate the capacity to hold the darkness and the light together, simultaneously, because that is the way the world actually is. Certain poetry does that, and music, and some people also do it -- usually very quietly -- in the way they live their lives.

During these weeks of isolation I started out reading some Renaissance poetry -- Shakespeare, John Donne. Then fast-forwarded to recent decades, especially Seamus Heaney, Tomas Transtromer, and Derek Walcott. Lately I've been reading from my collection of post-war Polish poets: Zbigniew Herbert, Tadeusz Rosewicz, Czeslaw Milosz, Wislawa Szymborska, Adam Zagajewski. After this maybe I'll turn back to the Russians: Akhmatova and Mandelstam and their compatriots who wrote under Stalin, and their heirs, like Joseph Brodsky. Or go all the way back to the Greeks.

Here's Czeslaw Milosz, writing after the death of his fellow poet Tadeusz Rosewicz. It's not the most cheerful elegy. I apologize. But it gets at what I'm trying to say.

Rosewicz

he took it seriously

a serious mortal

he does not dance

he lights two thick candles

sits before a mirror

amused by his face

he does not indulge

in the frivolity of form

in the comic abundance

of human beliefs

he wants to know for sure

he digs in black soil

is both the spade and the mole

cut in two by the spade