Elizabeth Adams's Blog, page 19

August 28, 2020

Hermit Diary 37: Beginning Again, and Again, to Draw

Red ochre on my hand, Anatoliki, Mani Peninsula, Greece.

This week, thanks to a link from Jean Morris, I read an essay by David Farrier at LitHub, titled "On John Berger and Rediscovering Drawing during Lockdown." Some of you might connect with the personal story he relates:

When I was younger, I used to draw. Not particularly well; enough to gain a little praise from adults and peers, although it wasn’t praise that interested me. There was a stillness in drawing that I didn’t find anywhere else. Paul Klee famously called drawing, “taking a line for a walk.” In a way, like walking, it gave me a sharper sense of how my own body occupied space. The close attention to shape and space was grounding. It made me feel both more distinct from my surroundings, and at the same time more a part of them. Knowing that I could draw was a talisman I carried with me, like a pebble in my pocket.

And then, without any clear sense of why, I stopped.

It’s now nearly 20 years since I have drawn out of habit. When my children were small I did plenty of scribbling and doodling with them; twice, I have painted my wife a picture for her birthday. But I have rarely sat down to draw for the sake of it. On the few occasions I have picked up a pencil I retreated after a few sketches. The line was broken. I felt guilty for letting it go, and unable to pick it up again.

As he remarks, the initial appeal of drawing was not in seeking praise, but in finding a sense of groundedness, that he defines as "stillness" and a different sense of self, as both "distinct from his surroundings" and at the same time more connected.

During the lockdown in Edinburgh, he kept thinking about drawing.

Thinking too much about the sudden disconnection from the life I knew before, or about how dramatically the future I had anticipated had changed, brought on a kind of vertigo. Lockdown left me feeling unmoored, and my mind turned often to drawing. I needed the old feeling of being grounded by the line. But still, as the weeks of lockdown went by I didn’t draw.

Instead, I read John Berger’s essays about drawing.

Berger compared the drawn line to music, saying that the line emerges from somewhere and leads you on to someplace new. As a musician, it's always been helpful to me to remember that music is never static; it's always coming from somewhere and going somewhere. As an artist, I agree with Berger too: the drawn line arises and moves forward, and so do I, the draughtsperson. Each drawing takes me somewhere I didn't anticipate, and in some very subtle way, changes me. But during the time when I'm drawing, everything except the line is very still.

“Each mark on the paper is a stepping-stone,” Berger writes, “from which you proceed to the next, until you have crossed your subject as thought it were a river.”

After all those years of not drawing, Farrier finally pulls out an old sketchbook and some charcoals and goes out into the garden. He makes three sketches, and describes them all as "clumsy" but in the third, a branch of tomatoes, he says he "feels something shift."

But then, as Berger wrote, real drawing is both “a clumsiness” and “a constant question.” I realized that drawing is not a pause, but an entry into the complexity and open-endedness of any given moment.

I too felt something shift as I read this essay. It reminded me that drawing is not just something I do, but a place where I go. It's a human activity nearly as old as our species itself. Yes, some of us have greater facility and perhaps greater innate talent, but drawing always improves with practice. I've been fortunate to draw almost continually, all my life, and it's been a great help to me during this period of time. But from what many of you have told me, you're more like the author, who "for years, ... had shied away from drawing because I regretted breaking with it, and as more time passed the gap seemed ever more difficult to bridge."

Regardless of where we begin, or begin again, the place where drawing happens is accessible to everyone, and doesn't need to involve a great deal of self-consciousness or self-criticism. Sometimes all it takes is the courage to makes some marks. The hand, the eye, a stick of charred wood taken from a fire or a lump of ochre picked up from the ground -- this is all we need to take a line on a journey, and be taken by that line to somewhere new.

Basil and Tomatoes, fountain pen on paper, 9" x 6".

August 16, 2020

Hermit Diary 36: Out of the City

For someone who loves the countryside and nature as much as I do, staying in the city this summer has been a real stretch. Usually we would go to the U.S. to visit my father and spend time at the lake, but the border is closed to non-essential travel, and even if we did it, such a trip would mean a month of strict quarantine - two weeks on either side. Staying in hotels or B&Bs seems risky, so overnights away haven't really been considered. I've never been so grateful to live near a large city park, or to have a fairly private terrace that I could fill with plants.

For several weeks, we've been working very hard to clean our studio of everything we're not going to need. This has meant sorting through possessions, tools, supplies, equipment, and the work of our whole professional and creative lifetimes. It's a huge, heavy, and sometimes emotional task that felt almost overwhelming at the beginning, but after steadily putting in several hours a day, day after day, we're getting there. We've sold or given away a lot, recycled or thrown out the rest, and are gradually getting down to the core of what we want and need to keep for the next period of our lives. As you can perhaps imagine, doing this in the middle of a pandemic, very hot weather, and the current worldwide political and social crises has contributed to a roller-coaster of moods, from frustration to encouragement, that we've managed with as much equanimity as we could. However, we've really needed some breaks, and those are coming now in the form of day trips out of the city.

One beautiful day this past week, we decided to drive south toward Vermont and visit a favorite farm that used to be a perennial stop when we were making that trip every fortnight. Earlier in August, we had driven to our favorite fromagerie, Fritz Kaiser, where we bought cheese made from the milk of his herd of Brown Swiss, goats, and something new: water buffalo, which was delicious. Then we swung back to this same farm to buy the first sweet corn of the season.

We love seeing the flat fields of southern Quebec, filled with hay and corn and soybeans; the blowsy summer clouds; the blue skies.

At the farm this time we bought corn, strawberries, and field tomatoes, and then sat at a picnic table beside the barn, eating local ice cream from little paper cups that came with a wooden stick -- when was the last time I'd had one of those?

Then we went into the barn to find the source of the deafening crowing that had punctuated our snack. It was this magnificent Plymouth Rock rooster, who continued to crow while we visited the ducks and geese and chickens...

the rabbits...

...and the sheep and the goats. Watch the video and at the end, you'll hear him too!

August 11, 2020

Hermit Diary 35: Proud

It's Pride Week in Montreal, and although there won't be the usual city-wide festivities, the cathedral held a virtual version of our annual "OutMass" on Sunday evening. The link above is our choir's offering of hope and love, with photographs from last year's Pride parade. This piece of music was written by the British composer Will Todd and made available to musicians worldwide. It was originally written to celebrate the NHS in the early days of the pandemic, and offer some hope and cheerfulness with the rainbow as a symbol, but we felt it was just as appropriate for a dual purpose, acknowledging that the coronavirus is still with us, making events like these as well as the usual closeness between friends impossible, and also as a symbol of Pride.

Just as the service began, our gathering -- which had been advertised and was open to the public -- was Zoom-bombed by a group of anonymous men, who spewed homophobic hate in the most vile way possible. Thanks to the quick reactions of our hosting team, they were removed and the "room" was locked, but of course it was a shock, and distressing. However, the service resumed under the calm leadership of our music director, Jonathan White. The incident was unable to mar the beauty, love, and solidarity of the hour that followed, which was filled with music, spoken word, prayer, reflection, and shared purpose. In fact, I think all the positive qualities of the gathering were actually augmented, and burned into the memories of the people who were present.

When I think of the courage, gentleness, openness, honesty, and calmness of the people of all ages who were gathered, representing all aspects of LGBTQ+ expression as well as their straight allies, and compare it to the cowardice of those who tried to disrupt this beautiful celebration of pride in our human diversity -- and the sanctity of that diversity -- there's really little to say. It's so obvious. Love triumphs over hate.

I'm proud of our community, and extremely proud of and grateful for the friends who planned and prepared this service, and all those who came and stood together on Sunday night. Your strength makes all of us stronger, and I'm glad to be able to help salute you in music and join with you in working for a better, kinder, more just world.

The full service is embedded below. I'd like to call your attention particularly to the section from 26:16 - 32:10, where members of the community offer a litany asking God to "walk with us, grieve with us, and rejoice with us," interposed with Jonathan White singing a Kyrie.

July 28, 2020

Hermit Diary 34: The Transformative Power of Color

A few posts back I wrote that I was struggling to do art. Although I'm not back to my former productivity, it's getting better, and what's helping is color.

When I participate in or host zoom chats, I've tried to be conscious of what kind of visual impression I make. Though I'm not a person with a closet full of bright colored clothing, I've worn a lot more of it this spring and summer. Color always lifts my mood -- most of us respond that way. For some reason, human beings seem to echo or take cues from their environment, and while people in the south have no trouble wearing tropical colors, we northerners are notorious for wearing black, grey, brown and white in the colder months, just when everyone needs color the most. (But we're Canadians -- wouldn't want to stand out too much!) Anyway, all I'm saying is that I've been conscious of the effect of color on my spirits during this pandemic, and when I was trying to get back into doing some artwork, it wasn't linework that drew me in, but pure color.

After these still lives of fruit in straight watercolor, I did the piece below, which began as a drawing and ended up with the addition of watercolor.

Still life with Mycenean cup and Mycenean snail shell. Pen and ink with watercolor, 9" x 6".

I felt better after doing these, and I hope they cheer you, too. What helping you these days? Have you have had any thoughts about color during this time?

July 16, 2020

Hermit Diary 33: 50 Years of Ministry

On Monday I did this interview with Michael Pitts, former Dean of Christ Church Cathedral in Montreal, author of the newest book at Phoenicia Publishing, and a good friend. The next two days were spent on editing, resulting in the video shown above. Michael is a very progressive thinker and theologian who has written a lot about the issues facing the world and the Church -- and he's not someone who's afraid of change. I hope some of you will watch this, even if you're not a religious person, since we talk about issues of justice, the pandemic, doubt and uncertainty, and how mystery and science need to co-exist, not negate each other.

Here's a preview, in case you want a taste of the longer version:

I have to say that I love doing this kind of work, and that learning more about the technical side of video editing has been a pleasure, not a chore. My mind is racing with ideas of how to use live online events and recorded video for effective and creative communication: it's one positive and exciting outcome of our present situation.

July 10, 2020

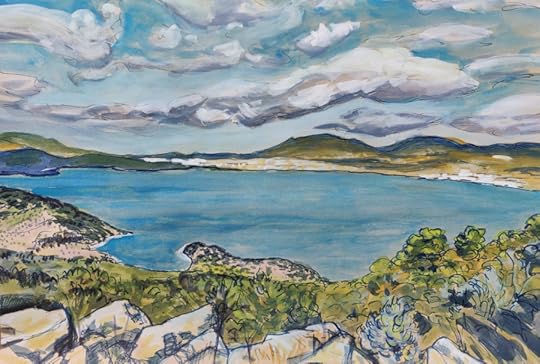

Hermit Diary 32: Sketches from a Greek Roadtrip

Come along with me on the road in Greece, as I try to sketch quickly from the car and during brief stops in-between destinations. (Headphones and full-screen viewing recommended, but it's also fine without.)

And please tell me what you like or don't like about this experimental video, because I'm hoping to do more of them. My videos so far are collected on a new page at my artist website, Studio Cassandra.

Thanks for watching!

June 25, 2020

Hermit Diary 31: Struggling with Art

Olive grove near Thebes, stormy day. May 18.

Since the pandemic and self-isolation began, I've been able to write, to work on publishing projects, to study a language, to practice the piano and sing, to get some daily exercise, to cook. But for some reason, it's been really hard for me to draw or paint, and what was a nearly-daily habit has dwindled to near-nothingness. I want to change that, but I also want to understand why it's been so hard.

Memorial bouquet and drawing for my mother, May 23.

Some of it may be emotional. I've never been someone who does art in order to work out my unhappiness, anxiety or other troubling feeling; that's when I turn to writing or music, or sometimes to repetitive or meditative pursuits like knitting, quilting, or bookbinding. I tend to draw or paint when I feel positive, creative, and focused, as well as when I know I've got a stretch of a few undisturbed hours. I've been surprisingly busy, partly because I've been hosting three Zoom groups each week and participating in several others, and also because of supporting and/or keeping up with many more people than before. But I don't think it's just that. I think most of the time I simply haven't felt I was in a zone where I could, or even wanted to, draw. And that in itself is troubling, and may be an indication that on some psychological level, this thing is taking a toll. Most of my art comes out of a feeling of joy or delight in the natural world or visual characteristics like color and form. I'm in the same small apartment all day, every day, and because we've had such a large number of cases here in Montreal, I keep moving on my early-morning walks; I don't feel particularly comfortable sitting in the park for hours with a sketchbook while lots of people go by. There's not a lot of visual inspiration, but that's just an excuse: there's always a subject to be found.

On the terrace, pen and watercolor (detail)

Beneath it all there's a feeling, both with the pandemic and the heightened awareness of Black Lives Matter, which does matter to me a great deal, that making "beautiful" art in this moment is frivolous, superfluous, socially-irrelevant -- and, at worst, white, privileged, and clueless. This is a dilemma into which many artists in all fields fall at some time, and I can talk my way through it to some extent: art and beauty are always relevant, but especially at difficult times, because the human spirit needs them, and because art affirms who we are at our best. But, oddly, it's a lot easier for me to participate in making a virtual choir video than in filling sketchbook pages with color and line and form. It's not just about me, it's collective, and even though we're singing European classical music, I know from comments received that the performances are a comfort that are appreciated by listeners well beyond our own congregation. It also doesn't feel problematic to write a blog post like this or keep my journal or write letters, where I'm trying to figure things out and to communicate.

Toward Corinth (detail). Pen, ink, gouache on toned paper. May 31.

As for art, though... I appreciated a line that my friend Teju Cole wrote in a New York Times collection of essays about the pandemic: "In these bruising days, any delicately made thing quickens the heart."

In a letter of response to him I wrote:

"I worry that all the delicate things are endangered, frivolous, or irrelevant, and that makes me sad, because I feel we need them more than ever when our hearts are so battered. Recently, inadvertently, I saw a set of collaged photographs of the youngest Black person to be executed in the United States -- it was a 14-year-old boy who looked like a child, being strapped into the electric chair -- I don't remember the year. His eyes were open, frightened, but somehow uncomprehending; it was the most horrific series of images, and I can't get them out of my mind. The cruelty of this country has been, and is, limitless."

Perhaps that is the crux of it: we have all been seeing images and videos that are deeply disturbing, and somehow this affects our visual/mental/emotional processing in general, particularly for those like me who are somewhere on the empath spectrum. I'm able to write about how I feel, I'm able to put my emotions into music, but I'm not willing to make dark, disturbing, or violent art -- and "pretty" art feels superficial -- so instead, I don't make much of any at all.

Loneliness. Still life, pen and ink.

It's been impossible not to notice that some of the blogs and social media feeds I follow seem to ignore current realities entirely. Because we need art, I am 100% in favor of people continuing their practices and their work as much as possible. Many musicians and performers cannot work at all, which is crushing. I realize that many people are just barely coping with day-to-day life right now. Others are, frankly, just as self-centered and self-serving as always. But my own position is less precarious than many, so long as neither my husband nor I get sick. John Kennedy famously said, "To those whom much is given, much is expected," but the original quote is actually from the Gospel of Luke: "From everyone to whom much has been given, much will be required; and from the one to whom much has been entrusted, even more will be demanded". I'm thinking hard about balance and integrity: awareness of -- and rethinking -- my own privilege; willingness to learn and change; compassion for others; leadership and speaking out; re-ordering my life to do what I can to help.

Life is not normal right now. It hasn't been normal, in terms of the pandemic, for at least the past four months: it has been a field of death, suffering, anxiety, grief -- and sacrifice on the part of a great many essential workers. The future, by any measure, looks very difficult. And for people of color, who have been disproportionately affected, and whose historic and present oppression and inequalities are now finally in the public's attention, life has not been what we white people call "normal", perhaps ever. I'm reading Ibram X. Kendi's How To Be an Antiracist and highly recommend it. It's time to learn more, no matter how enlightened or allied we think we already are, and the shift in thinking about race that Kendi presents is crucial. Frankly, that's just the beginning of what we need to do.

So how does my art fit into this picture? I know I'm helped by a regular drawing practice. It centers me, and uses a different part of my brain and spirit; as a meditative practice it's good for me. Likewise, if sharing my drawings and paintings creates a bright spot in someone's day, or encourages someone else to keep a sketchbook, then that's good. For all these reasons it's worth keeping at it. Being an artist is part of my identity, but not all of it -- and maybe it needs to take a back seat for a while. I don't want to be represented exclusively right now by pictures of flowers and gardens, landscapes, or harmonious still lives, unless I have worked to imbue that still life or landscape with additional meaning. It's not who I am, and it's not where I'm at.

June 19, 2020

Hermit Diary 30: Spiritual Inheritance

This entry is cross-posted from the Daily Bread blog at Christ Church Cathedral, for which it was written.

Psalm 92

The righteous will flourish like a palm tree,

they will grow like a cedar of Lebanon;

planted in the house of the Lord,

they will flourish in the courts of our God.

They will still bear fruit in old age,

they will stay fresh and green,

proclaiming, “The Lord is upright;

he is my Rock, and there is no wickedness in him.”

Today, June 19, is my maternal grandmother’s birthday. Born in 1900, she would be an impossible 120 years old today, but actually she did live a very long life, to the age of 92, “still bearing fruit in old age.” If I have an “Anglican” forebear, who somehow gave me my faith and also a willingness to be involved with, and work for, the Church, it was my grandmother.

I grew up my grandparents’ big Victorian house in a sleepy town in rural central New York. They lived downstairs, and my parents and I lived upstairs, but it was essentially one home so far as I was concerned, extending outdoors onto the porches and into my grandmother’s gardens. We lived across from the Episcopal rectory, and the church was next to it, across a street, so in addition to being parishioners, we were neighbors and friends with the priests and their families, who were also in and out of our house all the time. Behind the white-clapboarded, New-England style church was an extensive, centuries-old cemetery where my mother taught me to read the inscriptions on the tombstones, before I ever started school.

My father came from a musical Methodist family; my paternal grandfather was a Methodist minister and my grandmother a devout, white-gloved, conservative minister’s wife who never touched alcohol or played cards but loved music and dramatic reading. My tenor-voiced, irrepressible father had been the wild black sheep of that family of four children, and though I inherited the musical gift, their rigid spirituality didn’t have much appeal.

My maternal grandparents, by contrast, were liberal, worldly, expansive people. I guess you could call them “pillars” of the church: staunch supporters and consistent attendees. My grandfather was a frequent member of the vestry, my grandmother was active in the Episcopal Church Women and the altar guild. I grew up singing in the choir and my family always went to church, but I dropped out of Sunday School after a year; I was constantly questioning what was being said and taught, and having a smart but agnostic mother probably didn’t help.

But somehow, my grandmother’s steady faith became an example. She was outspoken and opinionated; a feminist; a longtime teacher; an avid reader; skilled cook, gardener, and seamstress; and a matriarch who ruled the family from her armchair, knitting basket and New York Times Sunday paper at her side (she did the crossword each week in ink). But also tucked away next to that armchair was her 1928 Book of Common Prayer, and a copy of Forward Day by Day, which she followed and prayed from daily, though I never saw her doing it. Her faith was a private matter, and I don’t remember discussing it with her very much, but even as a little girl, I sensed that it was what guided and steadied her strong ship. I spent many years away from the church, but I never completely stopped believing. I always felt that something from my grandmother had taken hold of me and was stored away inside; when I came back, it was clear to me that it was not only her faith, but her broad, inclusive Anglicanism with its love of language, ritual, and music.

After my grandmother died, my mother approached me one day with something in her hand. “I thought maybe you should have this,” she said, handing me my grandmother’s well-worn prayer book. She was right; of the various things I inherited from her, that little book is the most precious. Inside the cover are three simple prayers written in my grandmother’s Palmer-method handwriting: two for preparation for worship, and one for after: “Grant O Lord that the lessons I have learned may take root in my heart, that I may remain faithful to the confession of my faith, and that I may put my faith to practice in my daily life. Through Jesus Christ our Lord.” And I just noticed today that she had left the frayed black ribbon for marking pages at Psalm 139, my own favorite: “O Lord, thou has searched me out and known me,” which contains perhaps the most beautiful expression of God’s constant presence in all of Scripture. In the most difficult moments of my own life, I’ve often thought of my grandmother, and gratefully felt her strength and steadying presence -- which is, of course, simply feeling God through her.

This pandemic has made us all more aware of age, and the aged among us. It has made older people feel more vulnerable and isolated, and, to some extent, expendable; it has brought the pain of separation from loved ones and the fear and reality of dying alone. Western society is particularly good at discarding rather than respecting its elders and seeing them as a source of strength and wisdom. Navigating life’s challenges from a spiritual perspective really does boil down to “forward day by day”, as trite as it sounds; those who have done it have a great deal to teach us.

I love the image in today’s psalm of the human being flourishing like a palm tree, or a cedar of Lebanon, still bearing fruit in old age and staying fresh and green. So, on the positive side, perhaps this crisis could cause us to consider the ways in which we segregate by age, and how we could do more to encourage spiritual mentorship and friendship, as well as youthful companionship, within our own congregation.

June 15, 2020

Hermit Diary 29: On Journals

Last week, I was invited to participate in an online reading party centered on journals. The host asked us to choose a favorite journal to read from, and for the few days leading up to the gathering, to make some brief notes about what we had chosen and why. As it turned out, I couldn't participate on Sunday, but I ended up with the following notes (not brief at all) and today it occurred to me to post them here.

Friday. A journal to read from. What should it be? I pull out Transtromer’s Baltics, glance at the large spine of Anne Carson’s Nox, think about the Derek Walcott poems I’ve read recently that are diary-like, addressed to the poet himself. Virginia Woolf -- an obvious choice, but no. Then there’s Knausgaard, but what to choose? Or how about his Latin American counterpart Ricardo Piglia, in The Diaries of Emilio Renzi?

I realize with some dismay that one of my favorite journals, Thomas Merton’s The Sign of Jonas, is lent to a friend.

Your request feels pretty personal to me, WM., since practically everything I write is in the form of a journal. I’ve kept diaries since I was very young, and long before I began my blog I kept a paper -- and then digital -- journal, and for a while I even printed out the entries at the end of the year and hand-bound them, interleaved with that year’s correspondence.

Then The Cassandra Pages began, in 2003, and I’ve written it as a personal journal ever since. Then there are journals-within-journals -- a trip to Obama’s inauguration; our first month staying in Montreal; trips to lots of other places; the three-year decline and death of my father-in-law. At the beginning of the pandemic I started what I called A Hermit Diary, on my blog, thinking I would write about life in isolation...an echo of Merton, maybe. In these three months I’ve written 28 entries, each spaced further and further apart. At the beginning there was so much to say, and now, much less, or so it feels to me.

But there’s also another, parallel, private journal on my computer. It begins on April 26, 2004, with a quotation from Merton, a week before we began our move from Vermont to Montreal, and the most recent entry is on January 29 of this year. The wordcount at the bottom says it now contains some 311,414 words. I almost never go back and re-read this journal. (Is it private, even from me?) It’s where I work things out, write down dreams, copy out passages from things I’m reading, letters I’ve written or received. It’s where I complain and worry and try to get my head straight. Once I’ve written through whatever it is, I rarely feel like I want to revisit. And it’s not usually the sort of writing that I would go back and polish and make into a blog entry, or mine for an essay, though sometimes that happens. It’s more like meditation. Or wrestling with the angel who has wounded me.

Saturday. There are so many levels of private vs public, raw vs. honed, in my own journal-writing. This makes me mistrust other people’s published journals a little: how reliable, really, is this narrator we want to see as totally so? In fact, I think we’re rarely seeing the raw, uncalculated, truly private version, even in Knausgaard, though he wants us to think that we are. The skilled and practiced journal-writer who is also a writer is always aware of the possibility of a reader. So I keep coming back to Merton, whose journals influenced mine so much.

Merton’s The Sign of Jonas is a book drawn from his journals; he edited and rewrote what he had already written. It came out a number of years after The Seven Storey Mountain, the book which made him famous, and which he came to abhor. His private journals were published long after his death, and I’ve read them all, but even they were carefully edited. Still, what they reveal is that after years as a cloistered monk, living in silence, devoting hours and hours every day to contemplation, he had become keenly aware of all the games he played when presenting himself on paper, all the tricks of the ego, all the ways in which he sought fame or praise, and disguised and disgusted his true self in the process. He had left the academic world of New York in order to seek God and some sort of personal overhaul. He was aiming at authenticity, transparency, honesty, directness, egolessness... and yet he learned how the very act of writing -- which he couldn’t help, couldn’t give up completely -- became a trap for the ego. He talks about it a lot. This was his huge struggle: the need to say what he saw and felt out of the depths of his contemplative experience, to communicate it to others, and to try to make a difference in a broken world, but how writing can become performance that addictively seeks something else entirely: admiration, praise, fame. Just before his accidental death, Merton wrote this about his vocation: "He struggles with the fact of death, trying to seek something deeper than death, and the office of the monk, or the marginal person, the meditative person or the poet, is to go beyond death even in this life, to go beyond the dichotomy of life and death and to be, therefore, a witness to life."

Merton held up a mirror for many of the struggles I was having in writing and in art and in life, and in that mirror I saw myself, my games, my desires more clearly. The mirror shows the whole room: what we need to throw out, and the bits we should keep, and it’s a process that never ends.

Sunday. So, here’s the beginning of my private journal, April 2004. It’s Merton, writing on January 8, 1949:

In winter the stripped landscape of Nelson County looks terribly poor. We are the ones who are supposed to be poor; well, I am thinking of the people in a shanty next to the Brandeis plant, on Brook Street, Louisville. We had to wait there while Reverend Father was getting some tractor parts. The woman who lived in this place was standing out in front of it, shivering in some kind of rag, while a suspicious-looking anonymous truck unloaded some bootleg coal in her yard. I wondered if she had been warm yet this winter. And I thought of Gethsemani where we are all steamed up and get our meals, such as they are, when meal time comes around, and where I live locked up in that room with incunabula and manuscripts that you wouldn’t find in the home of a millionaire! Can’t I ever escape from being something comfortable and prosperous and smug? The world is terrible, people are starving to death and freezing and going to hell with despair and here I sit with a silver spoon in my mouth and write books and everybody sends me fan-mail telling me how wonderful I am for giving up so much. I’d like to ask them, what have I given up, anyway, except headaches and responsibilities?

Next time I am sulking because the chant is not so good in the choir I had better remember the people who live up the road. The funny thing is, though, they could all be monks if they wanted to. But they don’t. I suppose, somehow, even to them, the Trappist life looks hard!

This follows, written by me sixteen years ago:

It’s a grey, dark day here, and when we woke there was rain pelting against the roof. It’s let up now, and in the bathroom the rainwater is slowing sliding down the incline of the skylight, blurring the silhouettes of the bare-branched treetops. This is the sort of weather that has been depressing me all through the late winter, but today it seems almost indescribably beautiful. It is practically the last day for bare trees; leaf buds are swelling on all the red maples and the honeysuckles are already covered with a cloud of pale green. On the apple tree outside the bedroom window, drops of water hang from the ends of each black twig, daring both gravity and time.

In less than a week, we’re heading to Montreal to live for a month. This will be the longest amount of time I’ve spent in a city in my half-century of life. We’re going as a change from the life we’ve led here, from the house we’ve inhabited for more than 25 years, from the rural countryside, from the particular web of responsibilities and patterns we’ve woven. Besides being urban, Montreal is an international city: proudly and gracefully maintaining its French heritage and a broad ethnic and cultural diversity despite its proximity to the United States and the English-speaking provinces of Canada. It is a mere three-and a half-hours from here, and a world apart.

We’ve been thinking of this month as an experiment. After several years of weekend trips and the occasional week-long stay we want to find out what our commitment to this city really is: how much do we really like living there, and what might that mean for our future? This is what I thought the month was going to be about: practical matters, finding out how we felt, considering some changes and potential investments at this gently teetering point of midlife. Strange, then, that on this wet dark morning I felt, for the first time in several years, a strong call to contemplation. Could it be that part of this journey might be a sort of retreat, bizarre though it seems to retreat to a city? And yet I feel the call so clearly, bidding me to use the coming time and change of place not for distraction and escape, or merely for outward life decisions, but to learn something inner and as yet unrevealed.

For those who believe in God and believe, further, that She has a sense of humor, consider the irony of moving a writer -- especially one steeped in the ultimate contemplativeness of rural Vermont life, complete with clapboard-clad house and vegetable garden, and a pervasive silence punctuated only by bird and cricket -- to the bustle and endless distraction of a city of three million souls for the purpose of contemplation. Funny, even preposterous. But that’s what may be happening. I’ve been on this winding, unpredictable, and largely dusty spiritual path for long enough now to recognize the changes and imperatives when they come -- and for the most part, they have come like this, of the blue.

What immediately fits is the fact that contemplative solitude, for me, is actually easier to find in the city. Having lived my entire life in the fishbowls of small towns, where I cannot step outside my door or buy a bag of carrots without running into someone who knows me, the anonymity of the city is a huge relief. It creates a sense of freedom that is impossible for me here. Perhaps because of living so many years in the country, close to nature, solitude -- for me -- is not dependent on silence, but on being removed from the obligation to talk, interact, and plan. And yet, being a social creature and a moderate extrovert, and knowing that my husband (the opposite) likes to take off for long periods of photographic exploration on his own, I’ve been a little worried about having to deal with too much solitude during an entire month of urban living. “Use it,” I hear now. “It’s a gift.”

June 5, 2020

Hermit Diary 28: Some calm at the end of a wretched week

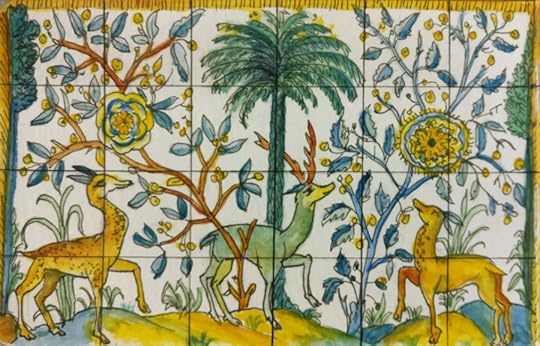

Deer under a palm tree, a watercolor and ink drawing of a tiled panel in Lisbon.

Such a difficult week this has been, full of sorrow, outrage, solidarity, anxiety for the future, and also some glimmers of hope that this might be a turning point.

I will not add any words, as I think this is a time for me, and for most white people, to listen to black voices, and to learn what we need to do (and not do) to be the best allies we can. What I can offer is a little bit of calmness through music, which is maybe the best and most continuous gift I've been able to give others throughout my life. Music has always given back to me, too, in multiples, helping me through the worst and best times.

Not being able to sing together has been one of the most difficult parts of isolation for me, and probably for all choral singers everywhere. Because there's so much danger about viral spreading through singing (though there have recently been some articles saying it may not be quite as bad as we initially thought), it's still going to be ages before congregational and choir singing returns to churches, and before my professional musician friends are back in concert halls. I'm seeing first-hand the financial and emotional toll this is taking on many of them. For congregations who are used to a lot of beautiful music, as most Anglicans are, the loss is keen too.

But where there's a will, there's a way. Our choir has produced its first two virtual choir pieces, and we've got two more in the works. These were presented during live-streamed Zoom services of Christ Church Cathedral, Montreal, and then placed on social media, YouTube, and the church's website, along with a growing library of organ music, music education resources, psalms and hymns, and recorded services. We're finding that the new situation is spawning some new creative responses, and also the surprising gift of being able to share what we do with a much wider, far-flung audience.

Recording your own part as a solo, based on a click track or recorded accompaniment, is totally different from the organic experience of sitting or standing next to your colleagues and making music together -- so much of what happens in live performance has to do with careful preparation combined with listening closely to each other to correct the pitch and watching the conductor for tiny shifts in tempo, dynamics, and feeling. This creates a collective emotional and physical reaction to the actual moment. It is intensely "real-time." In contrast, the way I do the recording is to stand in front of a tripod that holds my phone, which will record the video and audio of me singing, while playing the accompaniment on my computer and listening to it in headphones. Meanwhile I'm holding the score in my hands and yet trying to look at the camera as I would the director. You can see that most of us got better at presenting ourselves visually the second time around.

It's a very weird and self-conscious-making experience! But I've found that this process is showing me aspects of my voice and technique I didn't know, encouraging me to listen harder, practice, and try to improve in subtle and not-so subtle ways. For instance, I can really hear my American accent on certain vowels -- not really desirable! Once we've done several recordings and chosen the best, we each send off our video files, and our music director does the painstaking work of assembling and editing the tracks. The results have been startlingly good, considering how flawed some of us have felt our individual recordings have been. Even though our voices and images have been technically-reassembled, we sound remarkably like our own particular choir. Hearing and seeing these pieces of music, sung by people I care about deeply and haven't seen for months, has really moved me, and members of the congregation say the same. I hope maybe these motets will give you some peaceful moments at the end of this week.

The first, Palestrina's Sicut cervus, is a setting in Latin of the first verses of Psalm 42, "Like as the hart desireth the waterbrooks/so longeth my soul after thee, oh God."

The second piece is a setting of a well-loved hymn, O for a Closer Walk with God, by Charles Villiers Stanford (1852-1924). The original hymn was written by William Cowper in 1769 during the serious illness of an aunt he loved.

![IMG_20200824_111810[13877]_1](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1598711816i/30032478._SX540_.jpg)

![IMG_20200824_111810[13877]_2](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1598711816i/30032479._SX540_.jpg)

![IMG_20200824_111810[13877]_4](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1598711816i/30032480._SX540_.jpg)

![IMG_20200824_111757[13847]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1598711816i/30032481._SX540_.jpg)

![IMG_20200706_161756-01[12462]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1596078790i/29882767._SY540_.jpg)

![15958644993602[12749]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1596078790i/29882768._SX540_.jpg)

![15959462676413[12756]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1596078790i/29882769._SX540_.jpg)

![15958577068221[12743]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1596078790i/29882770._SY540_.jpg)

![15898458619331[8723]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1593157066i/29711728._SX540_.jpg)

![IMG_20200615_100206[11823]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1592381219i/29661449._SX540_.jpg)