Elizabeth Adams's Blog, page 18

December 11, 2020

Hermit Diary 47. Talismans

I made this little video in response to a prompt: What are the talismans that have gotten you through these months? What will you be taking with you into the New Year? (Thank you, wmc.)

November 21, 2020

Hermit Diary 46. Missing the Sea

Growing up in central New York State conditioned me to fields, forests, lakes, hills and river valleys. I was five when I had my first glimpse of the ocean, from New York harbor, but I wasn't actually on the ocean until I was 10, when my parents went on a deep-sea fishing trip off the coast of Maine with another couple and their son. We took off in a fishing boat and everything was fine until we anchored far offshore -- you could no longer see land -- and began to fish for cod with heavy-duty rods. I loved to fish and was excited to see dolphins, which we hadn't expected. My father and I hooked one large fish and were trying to reel it in when I began to feel the bobbing boat under my feet, and in just a few more minutes I was heaving my breakfast over the side. It was perhaps 9 in the morning, and I was wretchedly sick for the next six hours; when we finally got back to land I had trouble walking to the car, and vowed I'd never go out on the ocean again.

But some sort of fascination remained, and eventually got the better of me; my husband and I spent two summer vacations in Maine with friends of our own, and I was able to explore tidal pools and beaches on foot, and sheltered coves from a canoe. I've spent time on the Atlantic in South Carolina, Florida, New York and many parts of New England; the Pacific in California; the other side of the Atlantic in Cornwall and Portugal; the cold North Sea in Iceland and the warm Mediterranean in Italy, Sicily, and Greece. Oddly, during the pandemic, my thoughts have turned again and again to the sea. The other day in my studio, I pulled out a box of shells and other beach artifacts, and made these watercolor and ink drawings. All the shells here are from Block Island, off the coast of Rhode Island, where generous friends of ours have a house that we've been invited several times to visit. I spent happy hours on a rocky beach picking up odds and ends of seaweed, feathers, shells, crab carcasses, glass, and pebbles, knowing someday I'd want to draw them.

It made me happier to make these pictures, to escape into textures and colors that reminded me of places where I was both tranquil and curious. I know so little about the ocean, really. I'm in awe of its majesty and respect its power, and I'm drawn to its magnetically repetitive waves, its changeability, and the life it holds. As much as I love the calm, pastoral landscapes of my childhood, and find the woods and streams and lakes familiar enough to be unafraid there, day or night -- I know enough woodlore to probably survive quite a while in such an environment, if uninjured and warm enough -- my ignorance and unfamiliarity about the ocean keep me healthily cautious and aware. I like ferry trips, but I'm always a little nervous about getting seasick again, and the idea of an oceanic disaster seems more frightening to me than any air flight. I'd never go on an open-ocean cruise. Nevertheless, on the other side of every ferry trip there's always been something fascinating, and so much to see on the passage between, that I've forgotten my fears.

So why have I been thinking about the sea so much? I'm not sure. Some is wistfulness about not being able to travel, and wondering if I'll ever go back to some of the places I love, but I think it's more elemental than that. Maybe it's just a desire to sit and watch the waves crashing on the rocks, taking away my thoughts as I follow each wave like a breath, and then another: a desire for that renewal coming from somewhere I can't see, imagine, or understand.

November 7, 2020

Hermit Diary 45. Microcosm

I've made terrariums since I was a little girl. These miniature worlds fascinated me, perhaps because they reflected the natural places where I often played with my dolls: the mossy crevices between tree roots; the lush gardens of moss and lichens and fungi growing on stumps and dead trees in the woods, the little glades of clubmosses, ferns, wildflowers, and tiny tree seedlings in spots that caught a bit more light in the understory. In the fall, my mother and I would go on a gathering walk, collecting these small lifeforms for a terrarium that would stay green through the long winter, often in an old aquarium tank that no longer held water well enough for fish.

My husband and I recently brought all our plants inside for the winter, and, for the first time, set up grow-lights and humidifiers to help them out and increase the range of plants we could maintain during the days of short, dim northern light -- and also to help ourselves endure and enjoy what promises to be our own long winter captivity in a small apartment. We have an area for herbs, we've got orchids and begonias and many houseplants, and another place for cacti and succulents, all of which seem, so far, to be thriving.

![IMG_20201107_095733[15741]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1604839844i/30351339._SX540_.jpg)

The plants in a woodland terrarium are very different from these: mosses and ferns are primitive plants that reproduce by spores rather than flowering; lichens are composite organisms of a fungus living in symbiotic relationship with algae or cyanobacteria. Mosses are non-vascular plants that have been around for 470 million years; ferns, which have a vascular system, first appear in fossils in the Devonian period, 360 million years ago. Today, primitive plants persist in environments on the planet that reflect early conditions on earth: at the volcanic rift valley of Thingvellir, in Iceland, I spent one of the happiest days of my life exploring the riches of that tundra landscape where mosses and a wide variety of lichens thrive on volcanic rock. In geologic history, slow-growing mosses like these absorbed CO2 and dissolved the underlying rock, releasing chemicals into the atmosphere that caused marine die-offs and C02 absorption that ultimately led to the formation of the polar ice caps. Today, the reverse is happening.

My field-biology mentor, Herm Weiskotten, increased my knowledge of these species during the years I worked with him in the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. A botanist by heart, he loved nothing more than primitive plants, and we roamed central New York together in search of rare clubmosses and maidenhair spleenworts and other specialized plants to be grown in terrariums for our educational exhibits, or carefully transplanted into limestone outcrops or acidic woodland environments on our interpretive trails. One of my most precious possessions is a bent and water-damaged Peterson Field Guide to the Ferns and Clubmosses with Herm's name in the front, and several pressed fern fronds between the pages: he gave it to me after a misadventure where we both fell into the water of some remote bog.

I haven't had a terrarium for years, but as the leaves came down and the weather turned colder, I kept thinking about making one. We have a perfect glass bowl that originally held miniature succulents, a gift from our friend Jenny. Last weekend I brought it home from the studio, lined the bottom with stones and charcoal, added a layer of woody soil, and started gathering moss from northern sides of buildings on the city streets. Yesterday I went for a walk up on Mount Royal, the large hill we Montrealers call "the mountain", where I hoped to find a greater variety of potential inhabitants. It was a warm day, and I was happy being in the woods; I left the regular paths and wandered through the blanket of fallen leaves, checking out fallen tree limbs and moss-covered boulders, climbing higher and higher to where I thought I'd be able to find some lichens. After an hour or two, I came back down to my bicycle and the city with my small backpack holding treasures: mosses, a liverwort, grey-green and chartreuse lichens, a tiny shelf fungus, bits of shale and birch bark, a small fern.

This small and symbolic act has a lot to do with the election. As I’ve worried and waited, my thoughts keep returning to two issues in particular: the struggles of blacks, people of color, and migrants, and the peril facing our climate. The damage already done to both by the current administration is incalculable, but four more years could be irreparable.

I’ve lived a long time, and recognize that, like the lichens, my life continues to exist in a delicate balance with the other lives on our planet -- human, animal, plant, single-celled organisms, bacteria, and those, like viruses, that inhabit a shadowy zone between the animate and inanimate.

The terrarium is not a sealed, balanced, self-sufficient and self-perpetuating biodome, but a micro-environment for which I’m responsible: it can succumb easily to mold, drought, or neglect. As such, it’s a microcosm of the responsibility we bear for everything and everyone more vulnerable than we are, and thus subject to our destructiveness, indifference, and self-interest.

In the end, I find I care less about the survival of the human race than about the survival of biodiversity: the extinction of species at our hands has always cut me to the heart. I shudder to imagine a future for human beings that involves artificial environments or other planets where "trees" and "animals" only exist in giant, controlled biodomes isolated from a toxic exterior. The climate crisis will dwarf anything we’ve experienced so far, increasing human migration and threatening every remaining species as well as the air we breathe and the water we drink. The election of an American president who respects science and understands what we’re facing is perhaps one step back from the precipice, but we haven’t a moment to lose. This little world will remind me of that fact every day; unlike the larger one, I can hold it in my hands, admire its fragile beauty, and try to give it what it needs.

October 31, 2020

Hermit Diary 44. Lockdown Language Learning

When coping with this interminable disruption to our lives, daily routines help -- so say the psychologists. I've tried. Predictably, some routines have been more successful than others. Daily exercise gets maybe a B, that is, after my Achilles tendonitis got better - which also required a daily routine of PT stretches and tendon massage. I've done almost no strength training, though, just walking. Practicing the piano barely rates a C, though I've been doing better lately. I've read a lot, and will give myself a A for that. Cooking with some energy and ingenuity. Drawing and artwork, OK, but not every day by any means. Meditation? Yoga? Nope. Writing has been tough. I've tried to give myself some fun -- each day I do the NY Times mini crossword and several days a week I do the Spelling Bee puzzle, putting the answers on a spreadsheet and looking them up the next day, because I'm too cheap to buy a games subscription to the Times. I've been getting dressed (jeans and a top or sweater at least) every day, taking care of my non-professionally-cut hair, putting on earrings and even a little lipstick, because without that basic self-care I know I'm lost.

![16041903361210[15114]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1604229051i/30318730._SY540_.jpg) But where I've apparently been the most diligent is on Duolingo. When I passed the 300-day streak mark, I went back to figure out what date I started -- it was right at the end of last December. I've "studied" several languages on Duolingo over the years: French, Spanish, a bit of Italian and German. When I began this time, we had recently come back from Greece, and I decided to study some modern Greek, since I still remembered some ancient Greek from my college days but had been frustrated while traveling by my ability to "read" signs but say practically nothing. Then, in early March, the pandemic began. Somewhere right around there, I switched to Latin, and did the whole course on Duolingo, which is short and easy, and only comprises three checkpoints. Then I went back to the Greek and have kept it up every day since, using only three or four "streak freezes" to protect my streak in case I forget.

But where I've apparently been the most diligent is on Duolingo. When I passed the 300-day streak mark, I went back to figure out what date I started -- it was right at the end of last December. I've "studied" several languages on Duolingo over the years: French, Spanish, a bit of Italian and German. When I began this time, we had recently come back from Greece, and I decided to study some modern Greek, since I still remembered some ancient Greek from my college days but had been frustrated while traveling by my ability to "read" signs but say practically nothing. Then, in early March, the pandemic began. Somewhere right around there, I switched to Latin, and did the whole course on Duolingo, which is short and easy, and only comprises three checkpoints. Then I went back to the Greek and have kept it up every day since, using only three or four "streak freezes" to protect my streak in case I forget.

The app reminds you, occasionally, "15 minutes of Duolingo a day can teach you a language. What can 15 minutes of social media do?" Well, the latter phrase makes is a good point, but can you really learn a language this way? I wasn't so sure. I had learned some basic Spanish on Duolingo that definitely helped during our travels to Mexico City, and the French lessons clarified my weak areas in that language. Starting essentially from scratch with the Greek (I knew the alphabet so that wasn't an obstacle, but very few words or phrases) I was barely able to tell if the conjugations and declensions bore any relationship to ancient Greek, because Duolingo doesn't teach you that way. Different concepts are presented, sort of without you realizing it, under the subject heading of, say, "Animals" or "Clothing." Nobody says, "the third person singular of the verb to have is such-and-such", you just get sentences like "The woman has a child" and "The boy has a dog" until you've got it, and then "I have a husband" and "I have a cat" introduce the first-person singular form of the verb, also without telling you, or asking you to memorize a conjugation. In fact, you're never shown a verb table, or how to decline nouns, adjectives, or pronouns. Nobody tells you the rules, and nobody tells you the exceptions; you just have to figure it out by making mistakes and puzzling over the correct answer. For someone who has studied languages the traditional way, I found myself doubting I was learning anything except how to say inane and useless things like "My pet is a hamster."

So at first I got frustrated, which is why I switched languages. In the meantime, I ordered a modern Greek grammar book and a small dictionary/phrase book. After I finished the Latin lessons, I went back to the Greek. To my surprise, I actually remembered some of what I'd learned, and then started being a bit more methodical about it: writing notes, keeping lists of vocabulary, and making flash cards. I also started studying the basic grammar, just to get a better idea what the rules were -- sentence order, for one thing, and pitfalls for English speakers like the fact that modern Greek requires articles before most nouns, including first names: "the Eleni" instead of just "Helen."

In Duolingo, the first two practice levels (of five) for each skill or subject area don't require you to do difficult listening exercises, or write much Greek translation either from written English sentences, or from audio Greek. I progressed through two and a half checkpoints, going through the first two levels of each skill. Then, doubting myself, I went back to the beginning and started trying to complete all five levels -- and it got a lot harder, very fast. However, my retention started to improve, and my listening skills took a leap forward: modern Greek pronunciation is completely different from what I had learned from my classics profs.

So, am I learning, with my 15 minutes a day? Yes, slowly, just because I've been at it for a long time now. I'm not impressed with my concentration or overall effort. It's the persistence and repetition that have paid some benefits.

I remember at the beginning of the pandemic how people were saying, "Oh, with all this time, we ought to be able to write that novel, learn a language, study classical guitar, read Ulysses or War and Peace..." and then, when our concentration went to hell, our sleep became terrible, we fought with our partners or kids or became consumed by loneliness and confinement, and we didn't even know what day it was -- that was when we got obsessed by the news and started riding a rollercoaster of anxiety and depression, amid other days that felt more normal and optimistic. A lot of us felt guilty or confused about why we couldn't seem to do the things that we thought we were going to do -- I had hoped to finish writing a book, for instance, and I'm nowhere close. A friend sent me an article written by someone funny, who was trying to express her depression and lack of motivation, and she describes herself telling her therapist, 'I feel like I should be learning Portuguese" and the therapist says, "Don't you DARE learn Portuguese!" And no matter how well we may have managed in one area, I bet most of us feel like that in many others, and wish somebody would just say, "Don't you dare...!" and let us off our self-hung hook.

My sister-in-law, a retired academic who's gifted in languages, is studying Arabic for the third time in her life, and this time it's finally taking hold. She's taking a rigorous online course, and working on it for many many hours a day, and I think that's fantastic. But I can't do that, and don't really want to. Fifteen minutes a day works for me, and I've made enough progress that when I see a Greek sentence I know the parts of speech I'm seeing, even if I don't know the words, and my vocabulary is growing. Will I ever use it? Who knows. I think what this exercise has shown me is that the little-bit-every-day approach does pay off over time in language study, just as it does in a drawing practice. A seemingly daunting but desired goal is broken down into manageable little bits, and you commit to it, try not to get discouraged and give up, and eventually you see you've actually made progress. That's all.

But we're not all the same. Also at the beginning of the pandemic, someone created a humorous set of twelve staged photos showing people of different Zodiac signs reacting to the new reality. One person was in pajamas all day, another was happily boozing, another in a cleaning frenzy, and so on. And there was my sign, Virgo, looking neatly pulled together, at her desk, working away. Great. I'm not a believer in astrology, though I do have many of the characteristics thought to be "typical" for a Virgo. What I appreciated, besides the humor, was not that Virgos are organized, annoying workaholics, but that it illustrated so clearly how different we all are -- a fact that's been borne out throughout this thing and that is totally OK. "Don't you dare learn Portuguese!" you Gemini - it will make you miserable!

So, I'm curious how it's played out for you. What has worked, and what hasn't? And are you beating yourself up or accepting yourself as you are, because, honestly, having compassion and gentleness for ourselves is the first and most important practice of all. Then, only then, maybe you can find 15 minutes a day to practice something else.

October 16, 2020

Hermit Diary 43. Moving Inside

We call him "Mr Fang"

The days are getting shorter, the nights are colder, and there's already been a frost out in the countryside. This past weekend we disassembled our terrace plantings, and brought most of the plants inside. For the first time since living here, we've set up full-spectrum LED grow lights and are keeping most of our plants here at home rather than overwintering them in our studio. We have one area for succulents, another for culinary herbs, two others for our many houseplants that live outside in the summer, including some geraniums and begonias in the hope that they'll keep flowering. We thought both the plants and the additional light might help our mood and brighten the rooms where we're now spending so many of our waking hours. After only a few days it already makes a big difference.

Of course the proximity to all those shapes and textures inspires drawing! One of our most spectacular plants is the aptly-named Kalanchoe beharensis "Fang", at the top of this post, a gift from our friend and excellent gardener Guylaine.

Last Saturday I cut off the dragon wing begonias, which had grown to a huge size, before bringing them inside, and put the flowering stems in vases:

Last fall I'd done the same thing, and went back to look at the watercolor/ink drawing in my previous sketchbook. Maybe I'll manage to do another watercolor this year before the gorgeous crimson and hot pink flowers all fade.

And in another still-life painting, I tried to catch the last of the sweet pea blossoms, of which I had so few this summer, but the flowers got way too fussy:

Sweet peas in a Syrian glass vase, and a pebble. 6" x 9."

The best part of the painting is the lower section, with no plants at all!

October 10, 2020

Hermit Diary 42. A Greek Hillside,Pigments, and a Thorny Problem

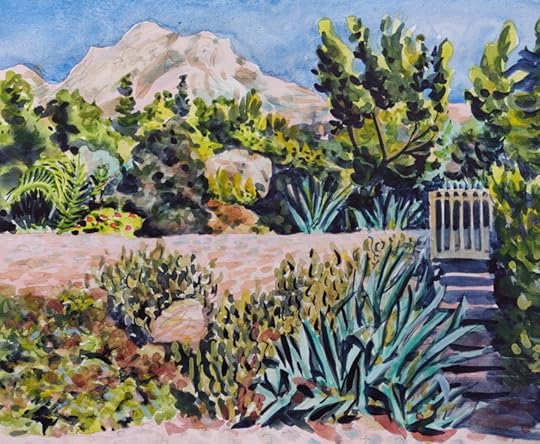

Greek Hillside with Blue Agaves. Watercolor in sketchbook, 11.5" x 8.5".

The painting above is where I ended up after working more on the previous sketch (below).

Here are a few details closer to life size:

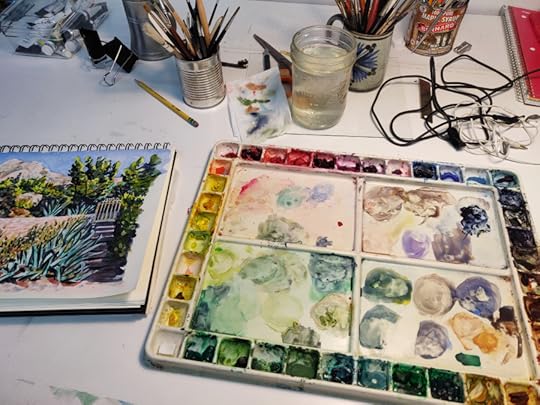

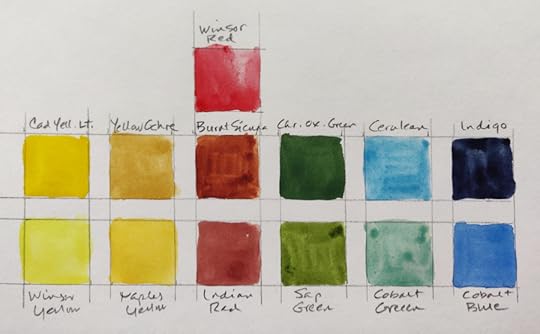

A regular reader here asked, a while back, if I'd post about my palette and what colors I'm using. Unlike the compact travel box I often use at home or outdoors, I used my large studio watercolor palette for this one.

However, as is often the case, I didn't use more than a few colors! But some of them were different from what I'd normally have on hand when traveling. Here they are:

I don't usually use cobalt green, but with the addition of a little cerulean blue it gave the perfect pigment for the agaves. The painting was begun with very transparent washes using highly dilute Winsor red, Winsor yellow, sap green, cobalt green, and other greens/yellows/olives/ochres mixed using Winsor yellow, cobalt blue, yellow ochre. I find that in order to unify the colors across a landscape painting, it helps to use the same blues as the sky (cobalt blue here) and to continue mixing the greens and earth colors with a limited pigment palette, rather than using raw colors "out of the tube," as one-off appearances on the page. The olive colors are made with blue and yellow, with the addition of a little red -- a much livelier and more transparent way to get greyer greens than by using a opaque green like the chromium oxide, which is an enormously useful color, but it can get muddy immediately when other colors are added to it.

The darks were all mixed with Indigo as a base; Indanthrone blue would have been another choice, whcih kept these areas quite transparent and luminous. A slightly dirtied (greyed) cerulean blue was used for the shadows on rocks and hills.

As the under layers begin to build up, then you can add some opaque pigments along with the more transparent pigments ones. Here I chose chromium oxide green, Indian red, cadmium yellow, and Naples yellow. If you look at this detail of the vegetation in the foreground of the painting, you can see the opaque mixtures on top of the darks -- but those have to be added when the dark areas are quite dry!

I added some pencil lines for texture and form.

This sketch seems to be another example of my lifelong obsession with the thorny problem of how to depict the varieties of natural vegetation and growth which often form an almost abstract pattern that also teems with life. It's often what draws me to a particular scene, and that certainly was the case with this hillside. Van Gogh is the only artist who went after this problem, in both drawings and paintings, in a way that I identify with. Somehow, I keep going back to it, and maybe I should just give in and pursue that challenge as obsessively as he did. It's particularly difficult to capture in watercolor, but the spontaneity of the medium also mimics life in a way that none of the others can do.

October 7, 2020

Hermit Diary 41. Searching the Landscape

I can't leave Montreal, at least until the end of the month, because a new lockdown was imposed on October 1, so there is no question of driving out into the country to see the fall foliage, visiting a natural area, or going apple picking, let alone visiting Vermont or the Adirondacks. I'm fortunate to be able to see trees and fall color from my window, and to have begonias, geraniums, nasturtiums and sweet peas blooming on our terrace, but I still have a persistent sense of being trapped -- as so many of us do.

It helps to turn to images of places I love. A couple of weeks ago I re-explored a garden we visited at the Ex Convento del Carmen (former Carmelite convent) in the Mexico City suburb of San Angel, and made a few drawings and watercolor sketches. The first drawing is below, and that's a watercolor of the same basic view at the top of this page.

From a different position, 90 degrees to the left, this is a massive stone seat with the convent walls behind:

One afternoon at the studio, I was looking through last year's Instagram posts and came across a watercolor of Delphi that I'd forgotten, and it struck me as much better than I remembered. I searched and searched through my sketchbooks until I finally found it in a drawer in the flat file -- I hadn't remembered that it was painted on a scrap of extra-heavyweight Arches watercolor paper -- my favorite surface to use -- and that's perhaps why it came out well. I'm always surprised how certain materials seem to inspire a better effort, while using others that may be just as good but somehow don't feel quite right to me personally always seems to end up with a lesser result. Originally I had cropped it much tighter; I don't know what I was thinking. Anyway, I cut a matte, put a frame on it and brought it home so I can remember that extraordinary day, everyday.

Yesterday I started on another subject, a hillside in Greece with blue agaves and cacti, and if it ever stops raining, I'll walk back up to the studio and finish that one, or work on the same idea in another medium.

As you can probably see, these watercolors are getting looser, less realistic, and more expressive -- but often I still do a fairly realistic black-and-white drawing first to work out the shapes and compositional relationships -- plus, I just like to draw. There are few activities that feel more absorbing, and even though I've done it all my life, it always feels like magic to start with a blank sheet of paper and end up with a representation of something observed and a record of that particular time and place and state of mind.

Drawing, more than any other art activity, also connects me to all the artists who've filled sketchbooks and made drawings. I feel my eyes travel from the object to the paper and back again, without much conscious thinking, as my hand somehow -- I don't pretend to understand it -- translates that seeing into lines and forms. Even when the drawing doesn't come out particularly well, it still seems like a little quiet miracle that human beings try to do this, and have always done it: "I sat here, I was still, I looked, I used my hands and eyes and made this." Maybe there's some hope for us after all.

October 5, 2020

Hermit Diary 40. Devoid.

Tonight I'm reeling with anger at the despicable remarks of the desperate and reckless narcissist who is president of the United States. Apparently, to him, people who have died of COVID are like those dead, maimed and captured soldiers he called "losers." And not only have his inaction and denial caused the deaths of tens of thousands of Americans, he's now blatantly risking the lives of those who've been closest to him. We hear about the staff members who've been exposed and tested positive, but what about the White House chambermaids who clean up after his family, the janitors and handymen, the secretaries and mail clerks and security people, the cooks and servers, pilots and drivers, to only mention a few? What are their names? What kind of medical care will they receive?

For those of us who have known people who died of this virus or are suffering either because of its longterm or indirect effects -- loss of work and security, lack of healthcare or insurance, displacement, grief, loss, separation, prolonged and intense loneliness -- the president's words are utterly revolting. But you don't have to have a direct connection to the pandemic's victims be an empathetic person, to see what has happened in the world because of it, as well as in so many other areas of cruelty, neglect, violence and suffering that this administration has caused and encouraged. I've never witnessed a leader and band of syncophants so devoid of empathy and compassion; it sickens me.

I don't wish death or this virus on anyone, including any of them: I want to see the Republicans resoundingly defeated in November and for the present inhabitant of the White House to go to court and be convicted. I want to see them fail to confirm their Supreme Court nominee. Whether any of that will happen or not, none of us know. Let us not demean ourselves by wishing ill on others, but let's not delude ourselves either. They will stop at nothing until the bitter end, and I'm sure we haven't seen the last twist in this tortuous road.

Meanwhile, it's even more imperative to take care of ourselves and each other.

September 21, 2020

Hermit Diary 39. Deer and Nasturtiums

Like everyone I know, I've been thinking a lot about Ruth Bader Ginsburg: saddened by her death, immensely grateful for her life, concerned about the future. If there's one legacy I'm sure she wanted to leave with us, it is that we must be just as courageous and determined as she was, and never give up, even in the face of enormous obstacles and opposition.

As 2020 continues to throw challenges at us, both in the world sphere and in our personal lives, how do we keep going? It all felt like too much several months ago! But keep going we must. For me, that means going back to the wells that nourish me. My wells may be different from yours, but they include music, art, books, and nature, all of which have an aspect of contemplative practice. Being with people is also nourishing, and like you, I've had to adjust the ways in which that can happen. It's not ideal, but cutting myself off from friends and family doesn't work at all, so I've gotten used to seeing people (mostly) online, and am grateful for it. I've decreased my social media activity a great deal, and it's definitely had a beneficial effect on my mental health and equanimity, slowing and quieting my mind as well as giving me more time.

The first leaves are beginning to turn here in Montreal, though it will be another month before they've fallen. The air and especially the nights are chilly, but the sun is bright and warm. Spending some time with these nasturtiums cheered me up. I look at my cat and realize she is just living in each moment; the nasturtiums, like the lilies of the field, "neither toil nor spin", and they certainly have way less awareness than the cat, but are simply beautiful for their brief lives. The other day, during a visit to a national park near the city, we had an encounter with a doe grazing in the forest: she reminded me of the deer on this little Greek pot.

Obviously we must try to protect the life on our planet, and each other, and work toward governmental responsibility and change, but we also need to take care of ourselves and find ways to take breaks from the spinning, obsessive anxiety that is so pervasive right now. No one can live, and certainly not contribute to solutions, within a constant barrage of negativity and anxiety. So I need these moments, which remind me how much of life is still beautiful, graceful, and quiet.

How are you doing, and where do you find some solace these days?

August 31, 2020

Hermit Diary 38. The times are out of joint: Seamus Heaney, Ballymurphy, and Kenosha

Yesterday I was reminded by Teju Cole that it was the anniversary of the death of Seamus Heaney.

This morning, as I sat with the cat and the peaceful light, I took down my copy of Heaney's North (1975), which is both about the idea of North, and Northern Ireland. Opening the book at random, I read “Whatever You Say Say Nothing”

The poem begins:

I’m writing just after an encounter

With an English journalist in search of ‘views

On the Irish thing’. I’m back in winter

Quarters where bad news is no longer news,

Where media-men and stringers sniff and point,

Where zoom lenses, recorders and coiled leads

Litter the hotels. The times are out of joint

But I incline as much to rosary beads

As to the jottings and analyses

Of politicians and newspapermen

Who’ve scribbled down the long campaign from gas

And protest to gelignite and sten,

Who proved upon their pulses ‘escalate’,

‘Backlash’ and ‘crack down’, ‘the provisional wing’,

‘Polarization’ and ‘long-standing hate’.

Yet I live here, I live here too, I sing...

and it ends:

O land of password, handgrip, wink and nod,

Of open minds as open as a trap,

Where tongues lie coiled, as under flames lie wicks,

Where half of us, as in a wooden horse

Were cabin’d and confined like wily Greeks,

Besieged within the siege, whispering morse.

--

This morning from a dewy motorway

I saw the new camp for the internees:

A bomb had left a crater of fresh clay

In the roadside, and over in the trees

Machine-gun posts defined a real stockade.

There was that white mist you get on a low ground

And it was deja-vu, some film made

Of Stalag 17, a bad dream with no sound.

Is there life before death? That’s chalked up

In Ballymurphy. competence with pain,

Coherent miseries, a bite and sup,

We hug our little destiny again.

Then I opened the precious book to the page with Heaney's inscription (to the original owner, a man in Toronto), my left hand holding the curl of the facing page flat, and thought: his hand held this book just like that, before his pen touched the paper, on a day in March 1986 when he was still very much alive.

I hadn’t read the news yet; I wanted a few more minutes of the soft light on the oxalis and spirea, the seeping red of the begonia blooms, the slightly heavy lift of coffee to lips. Better, I thought, to listen to the poet speak of humanity’s endless appetite for conflict, while he manages, genius that he is, to work in Shakespeare and the Greeks, the Russian camps, the endless clamouring for news on the way to Ballymurphy or Kenosha, and have his company this morning as I “hug my little destiny.”

I copied out the poem and wrote this far. Then I looked up the details about “Ballymurphy.”

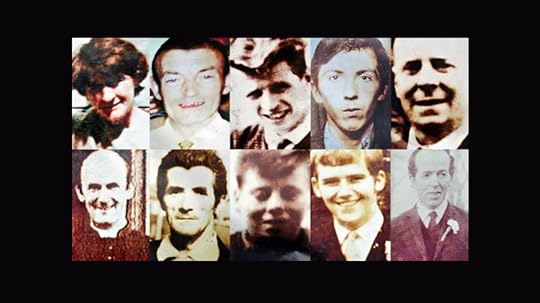

Eleven civilians were killed in the Ballymurphy massacre in August, 1971, by members of the Parachute Regiment of the British Army, which had already been in Northern Ireland since 1969. Britain had just launched “Operation Demetrius” which had the objective of interning without trial anyone suspected of being a member of the Provisional Irish Republican Army.

Members of the regiment said that as they entered Ballymurphy, they were shot at and returned fire. An account by Mike Jackson, who later became head of the British Army, stated that those killed in the shootings were Republican gunmen. This account was emphatically denied by the Catholic families of the people killed, all of whom were civilians. They included a Catholic priest, Father Hugh Mullan, who was trying to aid a wounded man, reportedly waving a white flag as he did so, and a woman, Joan Connolly, who was standing near the army base and then was left lying in a field for hours without medical attention, where she died.

None of the soldiers were held accountable and there was no investigation at the time.

45 years later, in 2016, an inquest was requested by the Lord Chief Justice of Northern Ireland. Funding for the inquest was “deferred” by the ruling party, and hearings did not begin until 2018. The last witnesses were heard in March 2020 after 100 days of testimony. A report is expected “in the coming months.”

--

Now, I’ll summon the courage to turn to today's news.

![IMG_20201029_160908-01[15094]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1606067141i/30414129._SY540_.jpg)

![IMG_20201104_162101-01[15156]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1606067141i/30414130._SX540_.jpg)

![IMG_20201104_162101-01[15156]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1606067141i/30414131._SX540_.jpg)

![IMG_20201106_203859[15739]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1604839844i/30351338._SX540_.jpg)

![IMG_20201107_103644[15740]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1604839844i/30351341._SX540_.jpg)

![IMG_20201107_142144[15746]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1604839844i/30351342._SX540_.jpg)

![15981129901731[13838]_c](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1602973250i/30251294._SY540_.jpg)

![16027204042860[14928]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1602973250i/30251295._SY540_.jpg)

![IMG_20200927_101515_01-01[14941]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1602973250i/30251297._SY540_.jpg)

![IMG_20200927_101515_01-01[14941]_b](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1602973250i/30251298._SX540_.jpg)

![16020214543910[14806]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1602401758i/30222195._SY540_.jpg)

![IMG_20201008_153258-03-01[14835]_b](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1602401758i/30222197._SX540_.jpg)

![IMG_20201008_153258-03-01[14835]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1602401758i/30222200._SX540_.jpg)

![15990888604572[13979]_b](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1602158595i/30208611._SX540_.jpg)

![15989719474210[13977]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1602158595i/30208612._SX540_.jpg)

![15995154300490[14821]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1602158595i/30208613._SX540_.jpg)

![16016756034400[14820]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1602158595i/30208614._SY540_.jpg)

![16020214543910[14806]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1602158595i/30208615._SY540_.jpg)

![IMG_20200915_201914-01[14091]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1600845773i/30142007._SY540_.jpg)

![IMG_20200915_203313-02[14092]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1600845773i/30142008._SY540_.jpg)

![IMG_20200915_201914-01-01[14090]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1600845773i/30142009._SY540_.jpg)

![IMG_20200831_105502[13965]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1598972500i/30046379._SX540_.jpg)

![IMG_20200831_083900[13963]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1598972500i/30046380._SX540_.jpg)