Terri Windling's Blog, page 8

September 2, 2021

Myth & Moor update

My apologies that there is no Myth & Moor post today. Tilly had an emergency vet visit this morning (don't worry, she's okay now), and the rest of the day was taken up by last-minute packing in order to get Howard off to London tomorrow.

In London, Howard joins his fellow pilgrims for The Pilgrimage for Nature, and they begin their eight-week walk to Glasgow, where they'll be presenting a performance (created during the walk, weaving in the voices and concerns of those met along the way) to the delegates at the UN Climate Change Conference in early November. He's just about ready to go now, but boy-oh-boy it's been a busy day, full of unforeseen challenges.

In London, Howard joins his fellow pilgrims for The Pilgrimage for Nature, and they begin their eight-week walk to Glasgow, where they'll be presenting a performance (created during the walk, weaving in the voices and concerns of those met along the way) to the delegates at the UN Climate Change Conference in early November. He's just about ready to go now, but boy-oh-boy it's been a busy day, full of unforeseen challenges.

Follow this link to see what my courageous husband will be doing for the next 8+ weeks. There are also regular updates on Facebook here; and they will be posting pictures on Instagram. If you're anywhere near the pilgrimage route, please join them if you can...for a day, an hour, whatever you can spare. All are welcome. You can also join the Long Walk digitally if you live far away.

Photographs above: Tilly and me on the beach near Teignmouth on Wednesday. She loved it, and so did I. Oh, to be in the sea again! We've been too long away.

September 1, 2021

Down to the sea

Today I'm following our own local river, the Teign, down to the sea at Teignmouth: not by foot, or canoe, or anything adventurous as that but by car, with Howard's mum and Tilly. We want to catch the last day of Howard's Punch & Judy performance season...and then to walk on the beach and give Tilly a swim before we head home.

I didn't see any of Howard's Punch shows last summer (the picture above was taken the summer before) and haven't been to the ocean since the pandemic began. The particular health issue I deal with is one that renders vaccination less than optimally effective, and I must still be wary in public spaces -- but it's the end of the summer and the crowds have thinned substantially so I'm grabbing my chance. I can't wait for the sight of the sea, and to hear Mr. Punch boasting: "That's the way to do it!"

Myth & Moor will return tomorrow.

August 31, 2021

The Pull of the River

Continuing with recommendations of books on the theme of water:

The Pull of the River by Matt Gaw is an exploration of the UK's waterways "from the smallest tributaries to stent-straight canals and thick arteries that pump toward the sea. Over chalk, gravel, clay and mud. Through fields, woodlands, villages, towns and cities to experience places that might otherwise go unnoticed and perhaps unloved." Travelling in a homemade red canoe, Gaw makes his way down the Waveney, the Stour, the Lark, the Granta, the Colne, the Otter and other rivers -- sometimes alone, but most often with his friend and rowing partner James Treadaway. The text is an aquatic travelogue full of natural, social, and folkloric histories of each waterway; it's also a poignant portrait of a friendship bonded in adventure.

In the book's longest journey, Gaw and Treadaway follow the Thames from the Costwold countryside to the middle of London, starting at the river's unprepossessing source at Thames Head near Kemble. Gaw writes:

"It is trying to rain as we turn off the main road and lope over a muddy track. A miserable, wind-blown drizzle. A mizzle. The path bends past a scrapyard filled with shipping containers and broken-down cars. To the right, the double lines of rail track race each other to the horizon. We cross and head over a stile and past an old wall, shoulder blades of dry stone jammed together and crusted with thick skins of bright white lichen. In front of us the field slopes up to a small copse with a straggling line of old thorns tracking through the centre. And then we see it. A stone, guarded by an old ash: a flecked marble plinth that marks the source of the Thames: 'The Conservation of the River Thames 1857-1974. This Stone Was Placed Here to Mark the Source of the River Thames.'

"Directly in front of it is a small pit lined with stone. There are records that a well stood in Trewsbury Mead as late as the 18th century, surrounded by a wall measuring some eight feet. The wall was demolished, eroded, or shouldered down by cattle, and the well filled in, leaving just this tiny Andy Goldsworthy circle of oolite stone; a font to hold and offer up clear water; a cairn signifying both beginning and end.

"River sources are places of intrigue, portals from the underworld to this world, where water pulses, pumps or just trickles from mysterious beds to glint and dance in the sun. They are places of transition from the dark to the light, the starting point of a symbolic circle that sees a river rise to journey to the sea and return with the rain. In Norse mythology 'Hvergelmir', which means something like 'bubbling boiling spring', is the origin -- the source -- of all living things and the place to which everything will eventually return. But behind all the power and personality there has also been wonder; a sense of human curiousity at how something so great and powerful could spring from something so small. After all, to journey to a source is to go backward -- against the flow."

As they follow the river north and east from Crickdale to Lechlade-on-Thames (not far from William Morris' Kelmscott Manor), Gaw reflects on the mythology and sacred history Britain's inland waters:

"At Castle Eaton, the church of St Mary the Virgin is nearly dipping its toes in the water, its stone gold blushed with pink. A site of Christian worship since the 12th century, it is a place that was probably special for people long before that.

"Rivers have often been connected with the spiritual world, sources of life and death. It's one of the reasons there are so many gods, nymphs and myths associated with them. According to legend, for example, the Wye, the Severn and the River Ystwyth all share the same story: all three were nymphs conceived from must, rain, snowmelt, moss and marsh and born to the Lord of the Mountains, Plynlimon. When the day came for them to leave their home, to set out into the world, Ystwyth headed west, taking the shortest route to the coast, meeting the Irish sea by the town that would take her name. Hafren went next, winding through England and Wales, travelling for long miles before she reached the Bristol Channel; her shimmering route became known as the Severn. But the third daughter, Vaga (the Latin name of Wye and meaning wandering), wanted neither to rush nor spend time in the world of men. Instead she chose a quieter route, whispering through hills and crags, seeking out the wild places where beauty lived on. She sang through the valleys and forests: a song for the porpoising otter; for the salmon; for the curtseying bob of the dipper; for the kingfisher, whose jewelled back she softly kissed. She danced and darted, joyful, serene, all the way to Hafren, who rushed back upstream to meet her and guide her on, towards the sea.

"History overflows with rivers that are regarded either as divinities or possessing other-worldly powers. It should be no surprise that the Thames had the same treatment. No one is quite sure when Old Father Thames was first evoked, but there is plenty to suggest that those living by the river have been paying their dues for hundreds if not thousands of years. An Iron Age shield was dredged from the depths at Battersea in 1875 and ancient votive offerings are still constantly uncovered along the river, picked from the strandline by mudlarks and archaeologists.

"Perhaps its personification as a god, or the creation of myths around it, was a way of understanding the river and its changes; the act of worship an attempt to control or impose order on water that has the power to shape and fertilise land, to give life and to take it away. The divine river helped to make sense of the mystery, the beauty and the destruction of the natural world.

"Some suggest that Old Father Thames has links to other gods. Peter Ackroyd says Father Thames 'bears a striking resemblance to the tutelary gods of the Niles and Tiber'. The Roman river god Tiberinus certainly shares key characteristics with him: the beard, the locks, the aversion to clothes. Ackroyd suggestions that Old Father Thames's hipsterish follicles could represent the braiding channels of the river's flow. But whatever his past, Old Father Thames has come to be a personification of the river in both good times and bad. He has been seen as a revered guardian while also caricatured as a rude and filthy tramp, during the pollution of the 19th century, surrounded by dead fish and rotting livestock, offering up his children Diphtheria, Cholera and Scrofula to those who lived and worked on his waters.

"We continue slowly, taking a left bend, with the sun gilding water that is retreating from the fields. The current, no long funnelled by obstacles, slows to a glugging jog. At Kempsford there is another church named for St Mary, where Edward I, Edward II, Henry IV and Chaucer were all said to have worshipped.

"The arrival of Christianity may have meant the disavowal of the old gods, but the rivers continued to be sacred places, with plenty of churches built on their banks. The Thames is certainly a river of saints. A swelter of them. Birinus, apostle to the Saxons of the west, who baptised converts at Kemble and Somerford Keynes; St Alban, Britain's first Christian martyr, who parted the waters on the way to his execution; St Frithuswith, Frideswide, Frideswith, Fritheswithe, Frevisse, or just Fris, founder of Oxford Priory and patron saint of Oxford University, who summoned a holy spring from the earth. Relics too have found their way to the water's edge, from the spear tip that was said to have punctured Christ, to the skeletal hand of James the Apostle. But on this stretch, it seems that St Mary holds sway. The Mother of God on the mother of rivers."

The Pull of the River is a lovely book, from its start in Roger Deakin territory through beaver sightings in the West County to the final expedition through a Scottish canal. I particularly recommend it to readers unable to make such journeys themselves (for any number of reasons, from pandemic restrictions to disability) but who long to do so nonetheless. I count myself among those readers. There are days when memories of my own wilderness adventures seem like another life altogether, and I fear I'll never get there again. Books like Gaw's, and the other water-themed texts discussed last week, help bring the wild world back to me, and I am exceedingly grateful for it.

The art today is by Sir Stanley Spencer (1891-1959), who was born in Cookham, a small village by the River Thames in Berkshire. Spencer trained at the Slade School of Art in London, served with the Royal Army Medical Corps and the Infantry in World War I, and was an official War Artist in World War II -- but aside from these periods he spent most of life back home in Cookham, paintings gardens, flowers, landscapes, boatyards, village life, and religious paintings in which villagers stood in for biblical subjects.

To see more of his art, please visit the Stanley Spencer Gallery site.

The passages above are from The Pull of the River: A Journey Into the Watery Heart of Britain by Matt Gaw (Elliott & Thompson, 2018). All rights to the text and art above reserved by the author and the artist's estate.

August 30, 2021

Tunes for a Monday Morning

Today's music is by Owen Shiers, a musician native to West Wales who creates under the name Cynefin. "The word ���cynefin��� is swaddled in layers of meaning," Shiers explains. "A Welsh noun with no direct equivalent in English, its origins lie in a farming term used to describe the habitual tracks and trails worn by animals in hillsides. The word has since morphed and deepened to conjure a very personal sense of place, belonging and familiarity."

Shiers is engaged in "a musical mapping project which traces a line from the past to the present -- starting in the Clettwr Valley where I was raised. The result of three years research and work, the project���s aim is to uncover lost voices, melodies and stories, and give a modern voice to Ceredigion���s rich yet fragile cultural heritage. The resulting album, Dilyn Afon/Following A River, presents forgotten and neglected material in a fresh new light. From talking animals and tragic train journeys to the musings of star crossed lovers, farm workers and lonely vagabonds, these songs provide a unique window into the past and to a vibrant oral culture."

Above: "Forgotten Songs of Ceredigion," a lovely little video explaining the project. It was made for a fundraiser in 2018 to help finance the album.

Below: "C��n O Glod I'r Clettwr," the opening song of the finished album, released in 2020. The ballad describes "a life���s journey from birth to death along the banks of the Clettwr River, which starts its journey on the marshland above Talgarreg village and flows into the Teifi near Dolbantau Mill, on the border with Carmarthenshire."

Above: " Y Ddau Farch/Y Bardd A���r Gwcw," two songs with similar lyrical themes of animal communication. The first is a conversation between two stallions; the second is a conversation between a bard and a late returning cuckoo.

Below: "Y Deryn Du." Conversing with birds is a Welsh literary tradition dating from the classical period of Dafydd ap Gwilym, notes Spiers. "Named 'canu llatai' (llatai means love-messenger), such pieces usually involve a love-struck poet sending a bird with messages of love to a sweetheart. What sets this work apart from other llatai songs is that the author has not yet set his heart upon someone; instead the deryn du (a blackbird) acts as an avian dating service, listing all the apparently eligible local women."

Above: "Ffarwel I Aberystwyth," a song conveying the hiraeth (longing) of the sailors as they leave Cardigan Bay, naming the places and people they've left behind. The end section of the track is a fragment from a song, "Hwylio Adre (Sailing Home)," in J. Glyn Davies���s book of Welsh sea songs and shanties.

Below: the video for "Y Fwyalchen Ddu Bigfelen." This is another song, says Spiers, "which features a conversation with a blackbird. It's debatable, however, if the song can be included in the llatai category since the ���beloved��� in question is not a woman, but Wales itself. It is, in essence, a song of hiraeth by a boy who has crossed the border into England and is longing for his homeland, embodied in song by the mellifluous calls of the yellow beaked blackbird."

The painting above is by artist, author, and magic-weaver Jackie Morris, who lives on the coast of Wales. Please visit her website to see more of her extraordinary work.

August 29, 2021

A very short story

Tilly's morning: visiting her friend Old Oak to tell him all her news. She doesn't like going to the vet so often, but she likes coming home the long way by the river. She doesn't like her bitter medicine, but she likes the treats she gets afterwards. She doesn't like seeing Howard packing again, but she likes that he's home with us now. She likes that a lot.

She's seen ponies in the field today, heard a robin singing above the leat, and ate her first blackberries of the season. Last night she had some cheese after dinner, and cheese is her very favourite thing. She hopes Old Oak gets treats like this too.

"I do," he assures his friend. "I get visits from you.

August 27, 2021

Guest Post: Tenderness, the Breaker of Curses

Continuing on with the theme of water, today's Guest Post is by my friend Briana Saussy. Bri is a writer, teacher, and community-maker based in San Antonio, Texas, deeply rooted in the myth & fairy tale tradition. She's the author of Making Magic and Star Child, both of which I highly recommend. In the following piece, she looks at the symbolic, mythic, and magical connection between water and tenderness. After the long, long months of the Covid-19 pandemic, and with the world on fire in too many places both literally and metaphorically, this reminder be tender to ourselves and others is timely indeed. Bri writes:

"To be cursed is to be dried up, devoid of moisture and suppleness, brittle and lacking the essential ingredient of life: fresh, circulating water. The most harmful afflictions of body, mind, spirit, and soul are those that seek to take away, ignore, and otherwise exploit our ability to be tender towards ourselves and towards one another. The remedy for this affliction may take many different forms, but always includes blessing what is tender within you.

"In many different cultures, the evil eye is understood primarily as a 'drying' condition, one in which your money dries up, your health dries up, your fertility and verve for life also dry up. In opposition, to be blessed is to be moist, supple, full of flowing water, clean, bathed, and tender like new shoots of grass, tender like fresh green wood sprouting forth from a tree, tender like the water filled skin of a newborn baby nestled up safely in your arms. Losing one���s tenderness, therefore, is tantamount to losing one���s life.

"The loss of tenderness and thus of life is not difficult to achieve. Let yourself be taken over by anger, envy, jealousy, hatred, and fear, and you will know how easy it is to do. You can observe for yourself the negative consequences of being taken over by these emotions, how they cause a withering and a contraction in your life and relationships. But even so, we may come to doubt the need for tenderness. Why be tender in a world and in a time that seems so often to only reward the tougher-than-nails? How does one cultivate tenderness in the face of violence, bloodshed, and injustice? What is tenderness other than one more vulnerability, easily overcome by those who are 'stronger'? How do we stay tender in times such as these and how do we bless our tender places?

"We bless our tender places by calling in the waters. We call in the waters so that we might cry good and salty tears, make nourishing soup, wash the dust off our clothes, and irrigate the seeds we have planted. So that we may drink of the waters and bathe in them, washing ourselves clean, literally renewing ourselves. We call in the waters from within, reaching deep and accessing the sacred well that may be blocked or polluted, but is simply waiting to be set free, waiting to be cleansed so that it can run, rush, and spring forth from the solid ground of your very life.

"Tenderness -- and the circulating life waters corresponding to it -- points to the deepest parts of our resilient nature. Resilience is a power, and it is what makes for much needed hardiness of life and soul.

"Sometimes it seems that there is no water to call in, no source of nourishment, of life-celebrating and life-protecting magic. But finding the water, finding the sources of life and nourishment, is not an easy task. Especially not when you look around and all you see is hard, sun-baked rock, packed gravel, and too much asphalt.

"I have lived most of my life in desert regions, and so I know from firsthand experience the water that is there, hundreds of feet under the ground and flowing in madly rushing rivers or collected in fathomless lakes. You don���t see it, but it is there. When the territory around looks most inhospitable to tenderness, then you know that you are in exactly the right spot to fill yourself up with all that gives life, all that keeps you supple, all that keeps you tender. You may have to dig for it, you might have to learn to collect it drop by drop from precious rainfalls, you may end up going on a pilgrimage to find it; but it is there, waiting to be called upon.

"To bless tenderness is also to protect it. In desert areas that are hot, arid, and dry, the culture is one of toughness, and even the plants with their prickles and thorns seem to just be waiting for their chance to chew you up and spit you out. If you neglected to look closely, you would be forgiven for thinking that toughness and hardness is all that matters. But soulful seekers do look closer, and what we find are that the plants with the best boundaries are the same that have the most tender, water-filled skins. They give us the blessing way. Find the water, find the sources of life, and when you do, keep them safe; build a good boundary around them. Don���t just let anyone access your tenderness, choose actively and with discernment who and when and where receives the privilege of your softness.

"To bless our tender places is to ask for and gladly accept help. In many cultures there are Gods and Holy Helpers who bring the waters of life, bring the rains, bring the thunderclouds that roll in with their big noise, making the hairs on the back of your neck stand up and reminding you that you are very much alive, creating with every breath you take, holding an infinite cosmos within your very body. We are not islands meant to do it all on our own. We have two-legged and four-legged, winged, clawed, fanged, and finned relatives who are here and ready and willing to help point us in all the right directions; so we look to them and we listen.

"Finally, tenderness is meant to be shared. Like water, it requires a solid vessel, the boundary of the cacti, to keep it stored up safely; but once we are filled up with it we cannot help but overflow. The overflow happens in many ways -- through tears and laughter and deep kisses and long touches, through creative work and vibrant dance, and the sweet sound of the saxophone or drums under the stars. These are all medicines, results from the blessing and safe keeping of your tenderness, that literally spill forth and out into the world much like water, nourishing much like water, and restoring so many that are on the brink of death back into life.

"Tenderness is no small thing. It is, in truth, a source of the greatest strength. It is not the weak spot or the pain point to be covered up, but rather a sign post, the tracks in the snow, that carry you forward to your own headwaters, no matter where it leads. So remember that anytime the flow feels blocked, anytime your skin feels shrunken and life feels too dry, relationships too brittle, and your broken places too yawning and jagged; remember when you feel raw and exposed, vulnerable, or too tender, remember what lessons tenderness has to teach you about your own hardiness, your own deeply resilient nature. It may be time to bless your most tender places and call forth the waters once more."

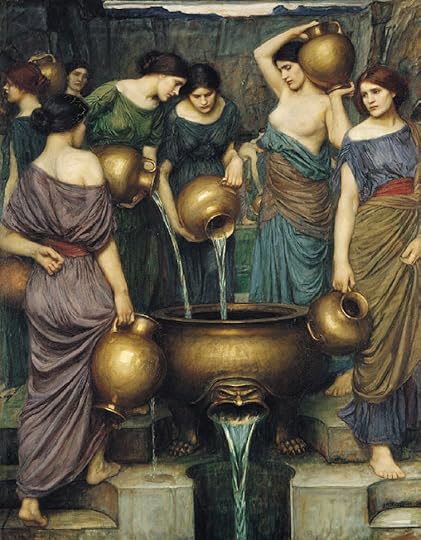

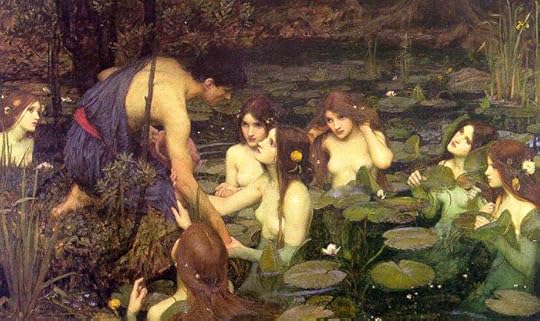

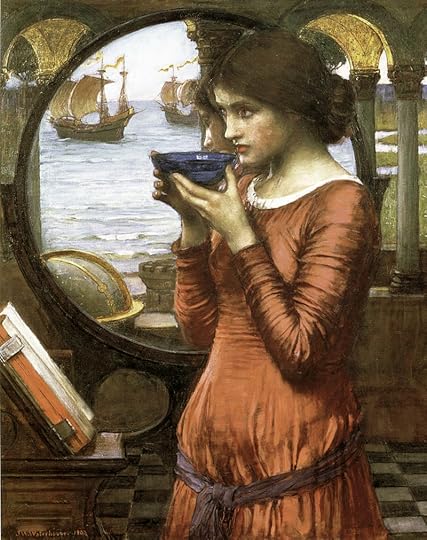

The paintings today are by John William Waterhouse (1849-1917), an English artist in the "Second Wave" of the Pre-Raphaelite movement.

All rights to the text above reserved by Briana Saussy.

Riverwalking

Riverwalking: Reflections on Moving Water was the debut essay collection by the American naturalist and eco-philosopher Kathleen Dean Moore, based in Oregon and Alaska, whose other fine books include Holdfast: At Home in the Natural World, Wild Comfort: The Solace of Nature, and Earth's Wild Music: Celebrating & Defending the Songs of the Natural World.

At the start of Riverwalking, she notes:

"The essays in this collection are river essays because I began to write each one alongside a stream or floating down a river, and so they may still carry the smells of willow and rainbow trout. Drifting on rivers, you know where you will start and you know where you will end up, but on each day's float, the river determines the rate of flow, falling fast through riffles, pooling up behind ledges, and sometimes, in the eddies at the heads of sloughs, curling back upstream in drifts marked by slowly revolving flecks of foam. So, drifting on rivers, I have had time to reflect -- to listen and to watch, to speculate, to be grateful, to be astonished.

"I have come to believe that all essays walk in rivers. Essays ask the philosophical question that flows through time -- How shall I live my life? The answers drift together through countless converging streams, where the move softly below the reflexive surface of the natural world and mix in the deep and quiet places of the mind. This is where the essayist must walk, stirring up the mud."

The twenty essays here invoke a range of different waters and terrains-- most of them in the Pacific Northwest, from the region's high desert to the Oregon coast. Moore reflects on the nature of home by the Willamette River, of grief among the ponderosa pines of the Metolis, of change in the shifting dunes of Bear Creek, of death by the Salish River, of clarity and mystery by the Smohalla.

On the latter subject she writes:

"The word clarity has two meaning, one ancient and the other modern. The Latin word clarus meant clear sounding, ringing out, 'clear as a bell'; so in the ancient world, 'clear' came to mean lustrous, splendid, radiating light. The moon has this kind of clarity when it's full, and so do signal fires and snow and trumpets. But that usage is obsolete. Now 'clear' means transparent, free of dimness or blurring that can obscure vision, free of confusion or doubt that can cloud thought.

"For twenty years, I thought that the modern kind of clarity was all there was, that what I should be looking for was sharp-edged, single-bladed truth, that anything I couldn't understand precisely was not worth understanding -- in fact, may not exist to a rational mind. I am beginning to see that this was a failure in courage. I am beginning to understand that the world is much more interesting than this, that I don't always need to know where I am, that ambiquity swells with possibilities, that possibility is ambiguous, that I miss out on the real chance when I pile rocks at the edge of the river to trap an eddy where the water will stop and come clear while the rest of the river pushes by, boiling, spitting spray, eddying upstream.

"I want to be able to see clearly in both senses of the word. To see clearly in the modern sense: to stop a moment, stock still, and to see through the moment to the landscape as it is, unobstructed, undimmed, each edge sharp, each surface brightly colored, each detail defined, separate, certain, fixed in place and time. These are visions to cherish, like gemstones. But also, every once in a while, to see landscape with ancient clarity: to see a river fluttering, gleaming with light that moves through time and space, filtered through my own mind, connected to my life and what came before and to what will come next, infused with meaning living, luminous, dangerous, lighted from with in."

I love that passage, and was startled by it. For me, clarity in the ancient sense comes easily; it is the modern form that I must consciously cultivate to keep my vision of the world in balance. And that, I suppose, is what makes Moore a scientist by nature; me, a folklorist and fantasist.

We need both ways of seeing, of course. Moore's "stirring of the mud" in these beautiful essays gets the balance between them just right.

Words: The passages quoted above are from Riverwalking by Kathleen Dean Moore (Lyons Press, 1995). The poem in the picture captions is from The Second Four Books of Poems by W. S. Merwin (Copper Canyon Press, 1993). All rights reserved by Moore and the Merwin estate.

Pictures: The photographs are of the River Teign where it winds through our Dartmoor village. The water here is slow and shallow -- perfect for gentle paddling by a recuperating hound. The drawing is "What the Moon Saw" by British book illustrator Helen Stratton (1867-1961).

August 26, 2021

To the River

Continuing with recommendations of books on the theme of water:

In To the River, Olivia Laing walks the River Ouse in Sussex from its source to the sea, mediating on its flora, fauna, mythology, history and literary associations along the way. Chief among the latter is Virginia Woolf, who lived near the river, walked by the river, wrote about the river, and died in the river. Laing's text meanders like the Ouse itself, but keeps bending back to Woolf and her work, and while every part of the book is engrossing her writing on Woolf is particularly captivating and insightful. (There is also very good chapter on Kenneth Grahame and The Wind in the Willows...but I digress.)

In the book's introductory chapter Laing notes:

"That spring I was reading Woolf obsessively, for she shared my preoccupation with water and its metaphors.Virginia Woolf has gained a reputation as a doleful writer, a bloodless neurasthenic, or again as a spiteful, rarefied creature, the doyenne of airless Bloomsbury chat. I suspect the people who hold this view of not having read her diaries, for they are filled with humour and an infectious love for the natural world.

"Virginia first came to the Ouse in 1912, renting a house set high above the marshes. She spent the first night of her marriage to Leonard Woolf there and later stayed at the house to recover from her third in a succession of serious breakdowns. In 1919, sane again, she switched to the other side of the river, buying a cold bluish cottage beneath Rodmell's church tower. It was very primitive when they first arrived, with no hot water and a dank earth closet furnished with a cane chair above a bucket. But Leonard and Virginia both loved Monks House, and its peace and isolation proved conducive to work. Much of Mrs. Dalloway, To the Lighthouse, The Waves and Between the Acts was written there, along with hundreds of reviews, short stories and essays.

"She was acutely sensitive to landscape, and her impressions of this chalky, watery valley pervade her work. Her solitary, often daily, excursions seemed to have formed an essential part of the writing process. During the Asham breakdown, when she was banned from the over-stimulations of either walking or writing, she confided longingly to her diary:

"'What I wouldn't give to be coming through Firle woods, the brain laid up in sweet lavendar, so sane & cool, & ripe for the morrow's task. How I should notice everything, the phrase for it coming the moment after & fitting like a glove; & then on the dusty road, as I ground my pedals, so my story would begin telling itself; & then the sun would be done, & home, & some bout of poetry after dinner, half read, half lived, as if the flesh were dissolved & through it the flowers burst red & white.'

" 'As if the flesh where dissolved' is a characteristic phrase. Woolf's metaphors for the process of writing, for entering the dream world in which she thrived, are fluid: she writes of plunging, flooding, going under, being submerged. This desire to enter the depths is what drew me to her, for though she eventually foundered, for a time it seemed she possessed, like some freedivers, a gift for descending beneath the surface of the world."

Laing begins her long walk at the source of the Ouse, near the village of Slaugham.

"I'd looked at this square of the High Weald on maps for months, tracing the blue lines as they tangled through the hedges, plaiting eastward into a wavering stream. I thought I knew exactly where the water started, but I had not bargained for the summer's swift uprush of growth. At the edge of the field there was a hawthorn hedge and beside it, where I thought the stream would be, was a waist-high wall of nettles and hemlock water dropwort, its poisonous white umbels tilted to the sky. It was impossible to tell whether the water was flowing or whether the ditch was dry, its moisture sucked into the drunken green. I hovered for a minute, havering. It was a Sunday, hardly a car passing. Unless they were watching with binoculars from East End Farm there was no one to see me slip illegally across the field to where the river was marked to start. To hell with it, I thought, and ducked the fence.

"The choked ditch led to a copse of hazel and stunted oak. Here the trees had shaded out the nettles and the stream could be seen, a brown whisper, hoof-stippled, that petered out at the wood's far edge. There was no spring. The water didn't bubble from the ground, rust-tinted, as I have seen it do at Balcombe, ten miles east of here. The source sounded a grand name for this clammy runnel, carrying the runoff from the last field before the catchment shifted toward the Adur. It was nothing more than the furthest tributary from the river's end, its longest arm, a half-arbitrary way of mapping what is a constant movement of water through air and earth and sea.

"It's not always possible to plot where something starts. If I went down on my knees amid the fallen leaves, I would not find the exact spot where the Ouse began, where a trickle of rain gathered sufficient momentum to make it to the coast. This muddy, muddled birth seemed pleasingly appropriate considering the origins of the river's name. There are many Ouses in England, and consequently much debate about the word. The source is generally supposed to be usa, the Celtic word for water, but I favoured the argument, this being a region of Anglo-Saxon settlement, that it was drawn from the Saxon word w��se, from which derives also our word ooze, meaning soft mud or slime; earth so wet as to flow gently. Listen: oooze. It trickles along almost silently, sucking at your shoes. An ooze is a marsh or swampy ground, and to ooze is to dribble or slither. I liked the slippery way it caught at both earth's facility for holding water and water's knack for working through soil: a flexive, doubling word. You could hear the river in it, ooozing up through the Weald and snaking its way down valleys to where it once formed a lethal marsh."

As Laing follows the thickening stream, then the river proper, from the High Weald to the Low, through the South Downs to the coast at Newhaven, she reflects on the land's long history, on writers from Shakespeare to Iris Murdoch, and on the crisis in her own life that propelled her onto her journey. She weaves many stories together, but it is Woolf's, most of all, that pulls her on.

It pulled me on too. I loved To the River, and didn't want it to end.

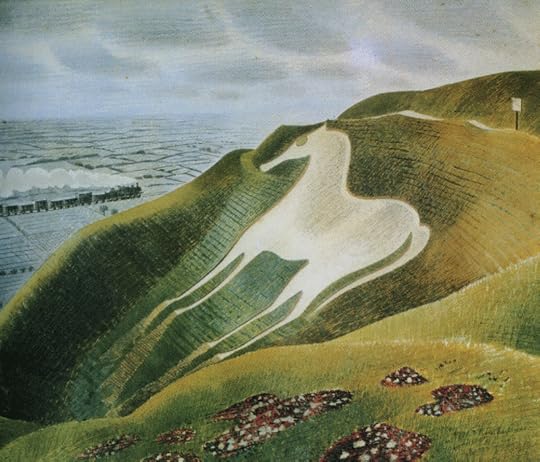

The art today is by the great English painter, designer, illustrator, and wood-engraver Eric Ravilious (1903-1942). He grew up in Sussex, and is now best known for his luminous paintings of the South Downs, but he also found inspiration in urban London, rural Essex, and other corners of England, Wales, and Scotland. Ravilious studied at the Eastbourne School of Art and the Royal Collage of Art, and went on to teach at both of these schools. He married fellow-artist Tirzah Garwood, and the couple raised three children (one of whom was the Devon-based photographer James Ravilious).

Ravilious served as an official War Artist during World War II, chronicling the war at home and abroad. He died while doing this work on an RAF mission in Iceland. His body was never recovered.

Please visit the Eric Ravilious site to learn more about the artist, and to see more of his work.

August 24, 2021

Drifting away in the current

I've been called away from the studio this morning, so I'm afraid there will be no post today. I'll be back tomorrow, bright and early, with more stories and books around the theme of water.

"Water does not resist. Water flows. When you plunge your hand into it, all you feel is a caress. Water is not a solid wall, it will not stop you. But water always goes where it wants to go, and nothing in the end can stand against it. Water is patient. Dripping water wears away a stone. Remember that, my child. Remember you are half water. If you can't go through an obstacle, go around it. Water does."

- Margaret Atwood (The Penelopiad)

The art above is by Arthur Rackham, from his classic illustrations for J.M. Barrie's Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens.

The Secret Knowledge of Water

Last week's posts, from Tuesday onward, were all connected to the theme of water in one way or another: Mr. Punch by the seaside; a riverside walk with Ursula Le Guin; the folklore of wells and springs; and the lush green riverbank of Wind in the Willows. We started this week with water music, and I'd like to carry on by recommending some favourite books containing water in its various forms -- beginning with one from the deserts of the American south-west, where water is scarce, precious, and sacred.

The Secret Knowledge of Water by Craig Child was one of handful of books that sat permanently on my desk when I lived in Arizona: books that served as talismans of all that I loved best about life in the Sonoran desert, and that I would carry with me when I crossed the sea to the wet, green hills of Dartmoor. Child's book begins in the vast wilderness of the Cabeza Prieta on Arizona-Mexico border -- a place I also had the great good fortune to spend time in over the years -- and then moves through a wide variety of desert terrains in northern and southern Arizona, Mexico, and Utah. What I love about the book is not only the author's deep knowledge of and passion for the land, but the way he writes about it in prose that is as poetic as it is instructive. For example, Childs begins his text with this arresting passage:

"My mother was born beside a spring in the high desert, just north of where West Texas and Mexico meet along the River Grande. Born three months premature, she was kept alive in an incubator heated with household lightbulbs. And eyedropper was used for feeding. The water from the spring bathed her and filled her body, tightening each of her cells. It filled the hollow of her bones. Years later, as the water passed from mother to child like fine hair or blue eyes, I grew up thinking that water and the desert were the same.

"Beyond the spring grew pi��on and juniper trees, their wood grossly twisted from years of drought, while here, where my mother was born, cress and moss grew from the spring. A weeping willow, imported from an unfamiliar place, dusted the surface with seeds. I traveled there once, walking up and pushing away the downy willow seeds with the edge of my hand. I dipped two film canisters below the surface. I capped these, and walked back to my truck, and drove away before a stranger could appear from a nearby house to run me off the property.

"I figured the water might come in handy someday. If my mother ever grew ill and her death were near, I would bring this water to her. The spring had kept many people alive before her. It was an essential stopover for Spanish explorers in the 17th and 18th centuries and for whomever traveled the desert for the previous millennia. I would slip its water between her lips, tilting her head up with my palms. Her body might recognize it, the way salmon make sudden turns to follow obscure creeks, the way dragonflies work back to the one water hole held between desert mesas.

"An early memory of the low Sonoran Desert where I was born is of my mother walking me out on a trail. I remember three things, each a snapshot without motion or sound. The first is lush, green cottonwood trees billowing like clouds against the stark backdrop of cliffs and boulders. The second is tadpoles worrying the mud in a water hole just about dry. Each tadpole, like the eye of a raven, waited black and moist against the sun. The third is water streaming over carved rock into a pool clear as window glass. These three images are what defined the desert for me. At an early age it was obvious that water was the element of consequence, the root of everything."

Later in the book, Childs describes the miracle of water in a dry terrain like this:

"Parched land wrinkles to the horizon and in one place, a rock outcrop, a seep emits a drop every minute, a light tap on the rocks below. The drop is sacred. Doled in such apothecary increments, this scarce water is almost deafening, surrounded by total silence, by hot sand fine as confectioners' sugar. It is a single word, a mantra.

"In places it gathers speed, finding pathways, turning from seeps to springs to streams to rivers. To be near such moving water in the desert is like being a vacant concert hall with a solo cellist, like standing on tundra with a grizzly bear. You must listen. You must make eye contact. The water cannot be resisted. Drops become elaborate cadence. The flow becomes song. It burbles from the ground, tumbling down hallways of isolated canyons. Life bends into preposterous shapes to fit inside, plying the narrow thread between drought and flood. Orders are given: you must live a certain way, and do it swiftly, elegantly, because this is a desert, this water is only here, and then a hundred miles of nothing.

"In the Kama Sutra, erotic sounds are said to come in seven categories: the Himk��ra, a light, nasal sound; the Stanita, described as a "roll of thunder"; the hissing K��jita; the weeping Rudita; the S��tkrita, which is a gentle sigh; the painful cry of Dutkrita; and finally the Phutkrita, a violent burst of breath. I have heard all of these in water, and then a hundred others, none of which have been offered titles besides plunk, plash, swish, or splash. I have heard the Phutkrita in the snapping of a tree limb during the sudden upwelling of a flood, and the S��tkrita sigh as that same water slowly spun itself into a downstream eddy. Horse trainers have so many names for horse breeds and colors, and Arctic dwellers have entire dialects for the nature of snow, yet few names have been given specifically to the sound of water. It may be that water is too commonplace. Since it must pass your lips every day, and you wash your hands with it as a habit, it might seem too pedestrian for study. If this is true, if water is so prosaic, come to the desert and listen to moving water. I have been held for days in a single place not because I needed the water, but because I had to listen."

This is a writer after my own heart. I, too, have sat beside water in the desert, unable to tear myself away. Needing to listen. To hear its stories. Like my life depended on it.

The art today is by my friend Stu Jenks, a Virginia-born photographer who has spent many years in southern Arizona. We've known each other for a long time now, ever since we had neighbouring studio spaces in the old Toole Shed art building in downtown Tucson; and to my mind, there's no one who captures the elusive magic of the desert better.

To learn more about his work, please visit Stu's Fezziwig Press and blog Fezziwig Press. You'll also find it here in previous posts, including The Borders of Language and Days of the Dead.

Words: The passages above are from The Secret Knowledge of Water: Discovering the Essence of the American Desert by Craig Childs (Little, Brown & Co, 2000); all rights reserved by the author.

Pictures: The photographs above are by Stu Jenks; all rights reserved by the artist. Titles can be found in the picture caption. (Run your cursor over the images to see them.)

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 710 followers