Terri Windling's Blog, page 7

October 4, 2021

Tunes for a Monday Morning

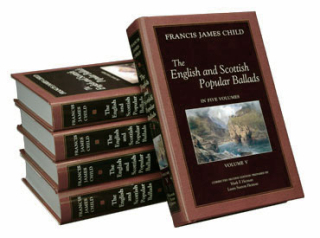

This week, a collection of Child Ballads: traditional songs compiled by American folklorist Francis James Child (1825-1896) in his influential five-volume text, The English and  Scottish Popular Ballads. Professor Child defined the ���popular ballad��� as a form of ancient folk poetry, composed anonymously within the oral tradition, bearing the clear stamp of the preliterate peoples of the British Isles. (If you'd like to know more about Child and his work, I've written about him here.)

Scottish Popular Ballads. Professor Child defined the ���popular ballad��� as a form of ancient folk poetry, composed anonymously within the oral tradition, bearing the clear stamp of the preliterate peoples of the British Isles. (If you'd like to know more about Child and his work, I've written about him here.)

Little is known for certain about how the oldest ballads would have been performed -- but most likely they were recited, chanted, or sung without instrumentation. Right up to the 20th century ballads were traditionally sung a cappella, though now they are performed in a wide variety of ways. Let's start with one well-rooted in the tradition while also modern and delightfully wacky:

Above: "The Fair Flower of Northumberland" (Child Ballad #9) performed by Alasdair Roberts, Amble Skuse, and David McGuinness. It's from their fine collaborative album What News (2018).

Below: "Hind Horn" (Child Ballad #17) performed by The Furrow Collective (Alasdair Roberts again, with Emily Portman, Rachel Newton, and my Modern Fairies colleague Lucy Farrell), from their wonderful new album At Our Next Meeting (2021).

Above: "Mirk Mirk Is This Midnight Hour" (a variant of "Lass of Loch Royal/Lord Gregory" Child Ballad #76) performed by Scottish musician Karine Polwart. It's from her lovely album of ballads, Fairest Floo'er (2007).

Below: "Three Ravens" (a variant of "Twa Corbies," Child Ballad #26) performed by Malinky, based in Scotland. It's from their early album Three Ravens (2002), when the members of the band were Karine Polwart, Steve Byrne, Mark Dunlop, and Kit Patterson.

Above: "Outlandish Knight" (a variant of "Lady Isabel and the Elf Knight," Child Ballad #4), performed by English folk musician Kirsty Merryn. It's from her second album, Our Bright Night (2020).

Below: "My Father Built Me a Pretty Tower" (a variant of "The Famous Flower of Serving Men," Child Ballad #106), performed by the English folk duo The Askew Sisters (Emily and Hazel Askew). You'll find it on their latest album Enclosure (2019), a collection of songs about the relationship between people and place. And just in case you don't know already, Delia Sherman wrote a very magical, gender-bending novel based on "The Famous Flower of Serving Men," titled Through a Brazen Mirror. I highly recommend it.

The art above is by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939).

September 27, 2021

Pilgrims' progress

As regular readers of Myth & Moor will know, three weeks ago my husband Howard set off from the center of London to walk to the UN Conference on Climate Change in Glasgow, a journey of over five hundred miles travelled over nine weeks. He's part of Listening to the the Land: Pilgrimage for Nature, a core group of twenty pilgrims drawn from performance arts, environmental sciences and other walks of life, joined together in their concern for the natural world at this perilous time. They are meeting with farmers and other land workers, earth scientists, environmentalists, and a wide variety of community groups in the towns and villages they pass through, with the aim of weaving their voices into a performance piece presented at COP26. They also welcome all who want to walk beside them for a day, a half-day, an hour. (Information on how to do so here.)

Our good friend Jane Yolen (multi-award winning novelist, poet, and children's book writer) gifted us with a poem for the Nature Pilgrims at the beginning of their long walk -- and in the video above Howard reads her poem, with Jane's permission of course. The setting is the orchard in Oxfordshire where the Pilgrims made their first camp.

In three week since then, the Pilgrims have walked the Ridgeway across Oxfordshire, received a pagan blessing at Uffington and an Anglican blessing at Birmingham Cathedral, walked up Shakespeare's Way in Staffordshire, crossed Cheshire via Alderley Edge (Alan Garner country), were blessed again at The Monastery in Manchester, and are now in Lancashire near Pendle Hill (a site associated with witches and Quakers). They've camped at farms, in fields, in the grounds of stately homes, in green spaces both rural and urban, and even had a few rare nights indoors in welcoming churches.

I've spoken to Howard most days on the road, allowing me to follow the Pilgrims' progress: the tough first week of acclimatising to walking and camping; days of exhilaration since then, but also of practical challenges; nights of conviviality around the fire, but also of aching weariness; deep conviction in the process of pilgrimage punctuated by moments of self-doubt, of hilarity, of sheer exhaustion...the ups and downs that mark any sacred journey, whether actual or metaphorical...and in this case both.

Today, the walkers begin Week Four, heading north into the Lake District. The weather is becoming wetter and colder, the days are drawing in, and the terrain they will be crossing is more challenging than the gentle hills of the midlands. But they are also finding their group rhythm now, allowing them more time to focus on the creative aspects of the project alongside the daily work of the walk itself. The spirit of the land is changing...and the Pilgrims are changing too, individually and collectively, transformed by a walking meditation on fluidity, open-heartedness, and the healing of our planet.

You can get a glimpse of what they're up to on the project's blog, Facebook and Instagram pages -- but please note that it's only a glimpse. Jolie Booth and Anna Lehmann, creators of Listening to the Land, didn't design it as a media event but as a proper old-fashioned pilgrimage: a journey across Britain in slow time, real time, step by step -- an experience of full engagement with the tactile, physical world. In our hyper-connected, media-saturated culture, this alone is a radical act.

If you're interest in what it's like to be a Nature Pilgrim, however, Howard has begun to record a video diary, talking about his experiences en route. You'll find those videos on Facebook here (and you needn't "friend" his page or join Facebook to see them). Comments are welcome, as are words of encouragement to brighten the harder days. He has also just started new pages on Instagram and Twitter, so please give him a follow if you're on either of those platforms.

As Tilly and I walk our own beloved land in the rolling hills of Devon, Howard is often on our minds. I wonder: Where is he now? What is he doing? Is he happy, healthy, getting enough sleep? Tilly's thoughts are more succinct: When is he coming home?

We pray to Mercury, god of the crossroads, to light his way and keep him safe. We pray to the ancient spirits of the British Isles for all his fellow walkers: for their work, their art, their collective intention, their love of the more-than-human world and their commitment to being a voice for change. Below is a photo of the offering we left yesterday at the local Fairy Springs on the Pilgrims' behalf: wildflowers and ripe blackberries, with an old dog's thoughts and a quiet woman's prayers and a whisper of wild poetry....

As I write this, the Pilgrims are walking north. They are walking for all of us.

Please note: The fund-raising campaign for Listening to the Land continues, to replace a final piece of funding that didn't come through at the very last minute. If you can help, by contributing or spreading the word, the crowd-funding page is here.

"Pilgrimage" by Jane Yolen is copyright 2021; all rights reserved by the author. Also, don't miss "Dear Pilgrims," a letter to the Nature Pilgrims written and read by Jackie Morris.

September 20, 2021

Tunes for a Monday Morning

More water songs, fresh and salty....

Above: "Anchor" by singer/songwriter Emily Mae Winters, who was born in England, raised in Ireland, and is now based in London. The song appeared on her album Siren Serenade (2017).

Below: "Great Northern River" performed by the The Unthanks, from Northumbria. They first recorded this song by Teeside musician Graeme Miles for their album Songs from the Shipyards (2012). The live version here is from the compilation album Other Voices, Series 11, Volume 1 (2013).

Above: "Queen of Waters" by the Anglo/Australian folk duo Nancy Kerr & James Fagan, performed at the Bath Festival in 2013. The song can be found on their album Twice Reflected Sun (2010).

Below: "Fragile Water," a magical song by Nancy Kerr, from her solo album Instar (2016).

Above: "Lady of the Sea" by Seth Lakeman, who hails from the other side of Dartmoor. This live version was recorded by Seth and his band in February 2021 for an online concert celebrating the 15th anniversary of the album Freedom Fields. The band members are unlisted on the video, but I recognise my Modern Fairies colleague Ben Nicholls playing bass for the concert.

Below: "Leave Her Johnny," performed by The Longest Johns, a folk & sea shanty band from Bristol, and their Mass Choir Community Video Project produced during the pandemic lockdown last year. "We originally hoped for 100 submissions for this project," they say. "When almost 500 turned up, we had to rethink our plans. It's so amazing to watch this video and see the faces of people still keeping Folk Music and Sea Shanties alive all around the globe. A huge thank you to everyone who took part, and remember to keep singing!"

Let's take a moment and marvel at the amount and diversity of art that has come out of this long, hard pandemic. The human spirit at its best.

The etching above is "Nocturne" by James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903)

September 17, 2021

The voices of the River Dart

The River Dart, which gives Dartmoor its name, begins with two primary tributaries: the East Dart, with its source at Cranmere Pool, and the West Dart, starting north of Rough Tor. They join at Dartmeet, then the Dart flows south past Buckfast Abbey, Dartington and Totnes, turning into a tidal river as it runs to the sea at Kingswear and Dartmouth.

The name of the river most likely derives from the old Celtic Devonian language, meaning something like "river of oaks," "oak stream," or "the sacred place of oak" ... and indeed, stretches of the the Dart still twist through low hills of ancient oak woodland.

I love the Dart...as does Alice Oswald, a widely acclaimed poet and a family friend (her husband and mine run a theatre company together). Some years ago, when Alice was still living on Dartmoor, she walked the river from moorland to estuary to create a book-length poem titled Dart: a gorgeous evocation of the river's history, mythology, and shape-shifting presence in the life of the land.

At the start of the book Alice notes that the poem "is made from the language of people who live and work on the Dart. Over the past two years I've been recording conversations with people who know the river. I've used these records as life-models from which to sketch a series of characters -- linking their voice into a sound-map of the river, a songline from the source to the sea. There are indications in the margins where one voice changes into another. These do not refer to real people or even fixed fictions. All voices should be read as the river's mutterings."

The poem begins with the river's source at Cranmere Pool, seven miles from the nearest road:

Who's this moving alive over the moor?

And old man seeking and find a difficulty.

Has he remembered his compass his spare socks

does he fully intend going in over his knees off the

military track from Okehampton?

keeping his course through the swamp spaces

and pulling the distance around his shoulders

and if it rains, if it thunders suddenly

and all that lies to hand is his own bones?

Tussocks, minute flies,

wind, wings, roots

He consults his map. A huge rain-coloured wilderness.

This must be the stones, the sudden movement,

the sound of frogs singing in the new year.

Who's this issuing from the earth?

The Dart, lying low in darkness calls out Who is it?

trying to summon itself by speaking ...

The walker replies:

An old man, fifty years a mountaineer, until my heart gave out,

so now I've taken to the moors. I've done all the walks, the Two

Moors Way, the Tors, this long winding line the Dart

this secret buried in reeds at the beginning of sound I

won't let go man, under

his soakaway ears and his eye ledges working

into the drift of his thinking, wanting his heart

I keep you folded in my mack pocket and I've marked in red

where the peat passes are the the good sheep tracks

cow-bones, tin-stones, turf-cuts.

listen to the horrible keep-time of a man walking,

rustling and jingling his keys

at the centre of his own noise,

clomping the silence in pieces and I

I don't know, all I know is walking. Get dropped off the military

track from Oakehampton and head down into Cranmere pool.

It's dawn, it a huge sphagnum kind of wilderness, and an hour

in the morning is worth three in the evening. You can hear

plovers whistling, your feet sink right in, it's like walking on the

bottom of a lake.

What I love is one foot in front of another. South-south-west and

down the countours. I go slipping between Black Ridge and White

Horse Hill into a bowl of moor where echoes can't get out

listen

a

lark

spinning

around

one

note

splitting

and

mending

it

and I find you in the reeds, a trickle coming out of a bank, a foal

of a river

From here the "muttering voices" include a fisherman, a forester, a water nymph, the King of the Oak Woods, a tin-extracter, a woolen mill worker, a swimmer, a boatbuilder and many others.

"I'm very interested in water," Alice says. "I'm interested in the way that it is a natural art form -- it actually pictures the world for you. You walk outside, and you are suddenly able to see a flat world reflected in the river. It's almost like nature's way of representing the world to you. But I think perhaps more than that, I'm an incredibly restless person, and I really admire the way water sheds itself all the time. I learn a lot from that. I aim to be as fluid as water if I can be. I don't like settling into one kind of character -- I like to shed myself as I go along."

Dart is a gorgeous book that seems to bubble out of the peat of Dartmoor itself. I urge you to seek it out.

About the imagery in this post:

The first picture above is an aerial view of the Dart (a Wikipedia/Creative Commons photograph).

The others, of the tidal portion of the Dart, were taken by me a few years ago -- during a solitary writing retreat at a waterside cabin loaned to me by good friends.

I lost my heart to the river during those long, quiet days, and the Dart has it still.

The passage quoted above is from Dart by Alice Oswald (Faber and Faber, 2002), winner of the T.S. Eliot Prize for Poetry. All rights reserved by the author.

September 16, 2021

The urban wild

After that unfortunate Long Covid interruption, I'd like to get back to recommending some favourite books on the subject of water. All of the books discussed so far have been set, largely, in the countryside or the wilderness, so today I'd like to recommend two interesting looks at urban waterways: Mudlarking by Lara Maiklem, about the Thames as it passes through London; and Hidden Nature by Alys Fowler, set among the canals of Birmingham.

A mudlark, the Cambridge Dictionary explains, is "someone who searches the mud near rivers trying to find valuable or interesting objects." Although we tend to think of mudlarks as figures out of the 18th and 19th centuries, there are still dedicated mudlarks today, and Lara Maiklem is one of them: irresistibly drawn to the tidal portion of the Thames, scouring the mud to find treasures, curiosities, and cast-offs full of stories about the past. Maiklem explains her unusual vocation like this:

"It amazes me how many people don't realise the river in central London is tidal. I hear them comment on it as they pause at the river wall above me while I am mudlarking below. Even friends who have lived in the city for years are oblivious to the high and low tides that chase each other around the clock, inching forward every twenty-four hours, one tide gradually creeping through the day while the other takes the night shift. They have no idea that the height between low and high water at London Bridge varies from fifteen to twenty-two feet or that it takes six hours to come upriver and six and a half for it to flow back out to sea.

"I am obsessed with the incessant rise and fall of the water. For years my spare time has been controlled by the river's ebb and flow, and the consequent covering and uncovering of the foreshore. I know where the river allows me access early and where I can stay for the longest time before I am gently, but firmly, shooed away. I have learned to read the water and catch it as it turns, to recognise the almost imperceptible moment when it stops flowing seawards and currents churn together briefly as the balance tips and the river is once more pulled inland, the anticipation of the receding water replaced by a sense of loss, like saying goodbye to an old friend after a long-awaited visit.

"Tide tables commit the river's movements to paper, predict its future and record its past. I use these complex lines of numbers, dates, times and water heights to fill my diary, temptations to weave my life around, but it is the river that decides when I can search it, and tides have no respect for sleep or commitments. I have carefully arranged meetings and appointments according to the tides, and conspired to meet friends near the river so that I can steal down to the foreshore before the water comes in and after it's flowed out. I've kept people waiting, bringing in a trail of mud and apologies in my wake; missed the start of many films and even left some early to catch the last few inches of foreshore. I have lied, cajoled and manipulated to get time by the river. It comes knocking on all hours and I obey, forcing myself out of a warm bed, pulling on layers of clothes and padding quietly down the stairs, trying not to wake the sleeping house....

"It is the tides that make mudlarking in London so unique. For just a few hours each day, the river gives us access to its contents, which shift and change as the water ebbs and flows, to reveal the story of a city, its people and their relationship with a natural force. If the Seine in Paris were tidal it would no doubt provide a similar bounty and satisfy an army of Parisian mudlarks; when the non-tidal Amstel River in Amsterdam was recently drained to make way for a new train line, archaeologists recorded almost 700,000 objects, of just the kind we find in the Thames: buttons that burst off waistcoats long ago, rings that slipped from fingers, buckles that are all that's left of a shoe -- the personal possessions of ordinary people, each small piece a key to another world and a direct link to long-forgotten lives. As I have discovered, it is often the tiniest of objects that tells the greatest stories."

Mudlarking is an unusual and thoroughly engaging book, full of the history of the city, of the river, and of the quirky society of mudlarks drawn to the banks of the Thames, past and present. Maiklem is a wonderful raconteur, and a knowledgeable one. If the subject intrigues you, check out her London Mudlark Facebook page for pictures of her adventures and finds, like the one below:

Hidden Nature by Alys Fowler weaves memoir with nature writing, centred on the old canal system of Birmingham in the English West Midlands. It's the story of the unravelling of a heterosexual marriage, of slowly and cautiously coming out as gay, and of the challenge of beginning a new life while standing in shock in the ruins of the old -- something many of us can relate to, even if the particulars of our dramatic life changes are different than the author's.

Longing for solitude and immersion in nature, Fowler daydreams about running away to Bolivia or central Asia, but settles on an adventure closer to home: exploring the Birmingham Canal Network -- in the heart of the city and beyond its borders -- in an inflatable kayak. She romanticises neither the urban canals nor her own life choices, writing honestly and insightfully about each; and yet the resulting story has a raw beauty of its own. Fowler writes:

"The backwaters [of the Icknield Port Loop] fascinated me. At night, I dreamt of returning to it, swimming, running through the water or just floating back down the same stretch that runs after the boatyard. In those dreams I saw everything in great detail.

"Nothing in that stretch was precious, not the abandoned day boats, the rubbish strewn in the water, the wayside weeds or framed views of urban wasteland beyond the broken factory facades. Nature there was a mixture of native and non-native. The weeds were growing straight out of heavy-metal pollution and were stunted or burnt by the effort. None of the trees showed the soft, new green of spring, but instead were flushed already with deficiencies, their trunks scarred by the battle of living there, their branches strewn with ribbons of plastic. As I returned to those images, I was already obsessed with and a little haunted by that landscape. I went back to do the loop again.

"It was as unsettled as I was. Its position was as temporal as mine. It was barely holding itself together: the canal sides were crumbling, the banks bursting with wild things ready to march into the water and claim new ground. That landscape couldn't quite decide what it was. It was wild, but not natural, it was old, but not old enough. Its riches kept changing or floating away. It belonged only to those who cared to claim it, outsiders, tenacious wildlife, the drunken, the homeless, the lost and me.

"I have never been much for joining in or up. I liked people and I liked belonging, but I have always floated between identities. One foot here and the other there, ready to move on if the boundaries seem to be settling into something rigid. I like best the edges of society, of ecosystems, of friendships. I like the place that is both held on to and departed from. And this watery world was just that. For the first time in nine years, I'd found a bit of Birmingham to fall for and all my internal butterflies took flight with excitement.

"I felt the great pull of the unknown, of adventure, setting in: if a place that was just a few miles from the city centre could hold another world so strange and unsettled, what would the past reveal? The pastoral edges of the network didn't pull me half so much as the dirty great industrial heart and its drum-thumping factories."

Much later in the book, Fowler reflects on this passage of her life, and her obsession with the city's waterways while in the midst of seismic life change. She writes:

"Travelling on the canals is to carry out a series of small rituals, to bear witness to the way light changes on the surface of the water or a seed head disperses and where next year's plants will appear. The best journeys are always worth repeating, and that is how I feel about my favourite stretches of the canals. I like those cathedrals of green trees in the suburbs. I like them in the spring when the fresh new green unfurls. I loved them in the autumn when those buttery leaves swirled around my paddle, and how in the stark of winter I see their bare bones swaying in the wind as I feel the chill of the water beneath me.

"I see now that this journey on the water was about finding an external correlation to my inner world, a fluid space that would allow me to make my own changes.

"The canals will change and change again. Those metal hulls will sink or be dragged out, the edges tidied, graffiti removed. I hope there will always be kingfishers and butterflies to watch; I hope later generations will watch herons spear fish and lean over the edge of their boats to peer at pike. I hope that everyone has the sense to leave a little of the edges wild."

We've talked about urban magic in a previous post, and how the cities, too, contain rich pockets of nature and of enchantment. Mudlarking and Hidden Nature, in their different ways, are celebrations this; and of the ways the wild flows through all our lives, no matter where we live.

The art today is one of my favourite American artists, James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), a brilliant colourist whose tonal paintings were both widely admired and deplored by the 19th century art establishment. (His work rarely invited mild reactions, nor did his pugnacious personality.) Whistler was born and raised in New England, but also spent part of his youth in Russia and London due to his father's work as a railroad engineer. He was educated at West Point Military Academy and worked as a military draftsman before deciding to devote himself to art. He then set sail for Paris at the age of 21, where he studied in the atelier of Marc Charles Gabriel Gleyre and fell in with a social circle that included Alphonse Legros, ��douard Manet, and Charles Baudelaire. He eventually settled down in London (around the corner from Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Thomas Carlye), where he spent most of his adult life.

Although today Whistler is perhaps best known for his figurative work (and his iconic portrait of his mother), he also made many paintings, drawings, and etchings of the River Thames over forty years. Art scholar Angeria Rigamonit di Cuto notes: "He began his explorations in the east of London, at Wapping, Limehouse and Greenwich, before moving upriver, his cosmopolitan background and outsider status perhaps easing his access to the mean streets of the docklands (among 'a beastly set of cads', according to his friend George du Maurier)."

You can see more of his distinctive artwork here.

The passages above are quoted from Mudlarking: Lost and Found on the River Thames by Lara Maiklem (Bloomsbury, 2019) and Hidden Nature: A Voyage of Discovery by Alys Fowler (Hodder & Stoughton, 2017); all rights reserved by the authors. The titles of the Whistler paintings and etchings above can be found in the picture captions. (Run your cursor over the images to see them.)

September 14, 2021

The landscape of story

In response to the on-going Pilgrimage for Nature (and getting regular updates from Howard on how the Long Walk is progressing), I've been thinking about climate change and the role we fantasists, folklorists, and storytellers might play in the urgent labor of healing our planet -- not only directly in the form of political activism, but also through our work as mythic artists. I was reminded of these words from "The Dreaming of Place" by storyteller Hugh Lupton:

"The ground holds the memory of all that has happened to it. The landscapes we inhabit are rich in story. The lives of our ancestors have contributed to the shape and form of the land we know today -- whether we are treading the cracked cement of a deserted runaway, the boundary defined by a quickthorn hedge, the outline of a Roman road or the grassy hump of a Bronze Age tumulus. The creatures we share the landscape with have made their marks, too: their tracks, nesting places, slides and waterholes. And beyond the human and animal interactions are the huge, slow geological shapings that have given the land its form. Every bump, fold and crease, every hill and hollow is part of a narrative that is both human and prehuman. And as long as men and women have moved over the land these narratives have been spoken and sung.

"This sense of story being held immanent in landscape is most clearly defined in the belief systems of the Aboriginal peoples of Australia. In Native Australian belief everything that is not 'here and now' is described as having gone 'into the dreaming.' The Aborigines believe that the tangled skein of remembered experience, history, legend and myth that constitutes the past -- that is invisible to the objective eye or the camera -- has not gone away. It is, rather, implicit in the place where it happened, a potentiality. It is a living memory that is held between a place and its people. It is always waiting to be woken by a voice.

"I remember the Irish storyteller Eamon Kelly once telling me that in the parish of County Clare where he grew up, every field had a name, and every field name was associated with a story. To walk from one end of the parish to the other was to walk through a landscape of story. It occurred to me that the same was probably once true for any parish in Britain.

"But today we are forgetting our stories. We have been forgetting them for a long time. Few of us live in the same landscape as our grandparents. The deep knowledge that comes from long familiarity has become a rarity. Places are glimpsed through the windows of cars and trains. Maybe, occasionally, we stride through them.

"What does it mean for a culture to have lost touch with its dreaming? What can we do about it?

"It seems to me that as writers, artists, environmentalists, parents, teachers and talkers, one of our practices should be to enter the Dreaming, that invisible, parallel world, and salvage our local stories. We need to re-charge the landscape with its forgotten narratives. Only then will it regain the sacred status it once possessed. This might involve research into local history, conversations with elders in the community, exploration of regional folktales, ballads and myths...

"And then an intuitive jump into Imagination."

I agree with Lupton on this. And who better placed than those of us in the folklore and fantasy fields (experienced in using the tools of myth and archetype in our art) to contribute to the important work of re-charging, re-enchanting, and re-storying the land?

The passage above by British storyteller, folklorist, and novelist Hugh Lupton is from EarthLines magazine (Issue 2, August 2012). The poem in the picture captions is from The Magicians of Scotland by Ron Butlin (Polygon, 2015). All rights reserved by the authors.

Related posts: Wild stories, Where the wild things are, The logos of the land, The unwritten landscape, Telling the holy, The writer's god is Mercury.

September 13, 2021

Spirits of water

"Naiad, (from Greek naiein, 'to flow'), in Greek mythology, one of the nymphs of flowing water -- springs, rivers, fountains, lakes. The Naiads, appropriately in their relation to freshwater, were represented as beautiful, lighthearted, and beneficent."

- The Encyclopedia Brittanica

Our little Naiad cannot pass a pool of water without plunging in.

The poem in the picture captions is from The Interpreter's House (Issue 59, 2015); all rights reserved by the author.

September 12, 2021

Tunes for a Monday Morning

I'm back in the studio today, not entirely recovered from a Long Covid relapse but doing a little better (touch wood). I'm taking it day by day at the moment -- which may continue to affect the Myth & Moor posting schedule, so please bear with me.

With Howard off on the Pilgrimage for Nature, I've been thinking a lot about climate change; so let's start the week with some songs about, and for, the world around us....

Above: "The Sadness Of The Sea" by singer/songwriter Martha Tilston, based in Cornwall. The song, she says, "was inspired by how I feel when I see the plastic that washes up on the shores near my home. However, it is also a song of thanks to the beauty of our natural world. " It appears on The Tape, the soundtrack album for Tilston's new film of the same name.

Below: "Half Wild" by singer/songwriter Kitty Macfarlane, from Somerset. She writes: "This song is a reminder that we are made of the same matter and mettle as much of the natural world, governed by the same laws and rhythms. We share the sea's chaotic balance of strength and fragility, and like the breaking waves, it's within our power to either leave a mark or to leave no trace." The song can be found on her album of the same name, released earlier this year.

Above: "Undersong" by Salt House (Jenny Sturgen, Lauren MacColl, and Ewan McPherson), based in Scotland. The song appeared on their gorgeous album Undersong in 2018. Their new album, Huam, is just as good.

Below: "Air and Light," from Jenny Sturgeon's exquisite album The Living Mountain (2020) -- inspired by Nan Shepherd's book of the same name, a classic of Scottish nature writing.

Above: "This Forest" by The Rheingans Sisters (Rowan and Anna Rheingans), based in Sheffield. It's from their lovely third album, Bright Field (2018), with animation by Harriet Holman Penney.

Below: "Dina Dukhio" by Balladeste (American violinist Preetha Narayanan and British cellist Tara Franks), from their new album Beyond Breath. The song, they say, "is inspired by a raga-based Indian devotional melody from the Sai Lineage, which in essence translates as ���overcoming sorrow.��� We wanted to explore the idea of ritual and letting go in this film following the experience of the last year and a half." The woodland film is by Tamsin Elliot.

And here's one more, dedicated to Howard and his companions on the Long Walk to the Climate Change Conference in Glasgow:

"Walking Song" by singer/songwriter Jon Boden, based in Sheffield. It's from his remarkable new album Last Mile Home (2021). You'll find the lyrics here.

Photographs: The south Devon coast in early September; and the Nature Pilgrims in Oxfordshire last week (the latter picture by Jolie Booth).

September 6, 2021

Pilgrimage for Nature update

The video above contains the beautiful, beautiful letter written by artist and author Jackie Morris (The Lost Words, Letters for the Earth, etc.) for the pilgrims now walking from London to Glasgow.

Jolie Booth (creator of the pilgrimage) writes: "Jackie Morris kindly gifted us with seven hand-painted labyrinth stones, a hand-drawn illustrated book that she wrote to the pilgrims, which we read out at the opening ceremony in London on Saturday. The Letters to the Earth campaign will be running workshops along our pilgrimage route for different communities to write and deliver their messages for a better future to the leaders of the world as we walk. What gifts! What magic."

Visit the Pilgrimage For Nature blog or Facebook page for further updates, photos, and the like. The project also has Instagram and Twitter pages that are now getting underway. For information on how to participate in the walk, even from far away, go here. And please note that there is a new fund-raiser going to keep the pilgrims on the road all the way to the UN Climate Change Conference in Glasgow (to replace other funding that didn't come through). If you have some pennies to spare, please give them your support.

Above, a photograph of the pilgrims in London on Saturday. Jolie writes: "The bags all packed and ready to go���we finally meet at Tower Hill. We���re filled with excitement and nervousness as we take the step into the unknown. From today we walk north, filled with curiosity and love."

May the weather gods continue to smile on them, may all the pilgrims stay safe in these difficult times, and may the work they are doing on behalf of Mother Earth be fruitful.

For those who worry about Covid safety (and I am one of them!), the pilgrims are in a Covid bubble, testing regularly, and there are protocols in place for meeting and working with others along the route.

September 4, 2021

A further update

I'm having a bit of Long Covid flare-up. No surprise, really. It happens less regularly now than a year ago, but still flares up if I get over-tired...and this last week has been a doozy, between Tilly's emergency vet visits and getting Howard packed up and off on pilgrimage.

Now Howard's on the road, Tilly is doing better, and my body seems to be insisting that I take some time to take care of myself. I'll be back to Myth & Moor very soon, with those final "water book" recommendations and more.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 710 followers