Terri Windling's Blog, page 11

July 23, 2021

Listening to the Land

Listening to the Land is a "pilgrimage for nature" in which a core group of 30 people (artists, performers and storytellers among them) will be walking from London to Glasgow this autumn for the UN Conference on Climate Change.

My husband, Howard, is one of those 30 pilgrims. He'll be setting off from London in early September, walking up the "spine of Albion," and arriving in Glasgow in early November -- an eight week journey covering roughly 500 miles. The group will be holding community meetings and giving creative workshops, talks, and performances in villages, towns, and cities along the way -- listening to the concerns of the people they meet, listening to the land itself, and weaving it all into a performance scheduled for presentation to the UN climate delegates on Monday, the 8th of November.

My husband, Howard, is one of those 30 pilgrims. He'll be setting off from London in early September, walking up the "spine of Albion," and arriving in Glasgow in early November -- an eight week journey covering roughly 500 miles. The group will be holding community meetings and giving creative workshops, talks, and performances in villages, towns, and cities along the way -- listening to the concerns of the people they meet, listening to the land itself, and weaving it all into a performance scheduled for presentation to the UN climate delegates on Monday, the 8th of November.

Listening to the Land has received funding from Arts Council England, and backing from the National Trust, the British Pilgrimage Trust, the Wisdom Keepers, Seed Sisters and other organisations -- but it's a big project, and they need to raise an additional ��4500 this summer. (It's heartening to see they are already half-way there.) If you can help with even a small donation, please visit their Crowdfunding page -- where you can also learn more about the project, and what the additional funds will be used for.

I'm delighted that Howard is doing this...and, I admit, a bit nervous too. It's a long, long journey, and England is in a dark place right now...but we need the light that collective art-making creates, and the subject could not be more urgent. Howard is no stranger to pilgrimage, having already traversed the Camino to Santiago de Compostela through the French and Spanish Pyrenees; and for many years he criss-crossed Europe with his Commedia troupe, so he's used to being on the road in one form or another. This time he'll be walking with colleagues from the Nomadic Academy of Fools, doing fooling practice and performance along the way. Nature, pilgrimage, foolery. How could he possibly miss it?

I have a vested interest in seeing that the pilgrims are fed, so please chip in if you can. (No worries if you can't. It's been a hard year for many. Good wishes and prayers are equally welcome.) The fund-raiser runs for 16 more days.

And the walk itself begins dauntingly soon....

Picture above: Howard and Tilly earlier this week. She's going to miss him so much this autumn, and so will I. But for such a good cause.

On borders and stories

Following on from yesterday's post, here's one more passage from Thin Places by Kerri n�� Dochartaigh, a book about myth, land, language, trauma (both personal and collective) and its healing, and a deep meditation on the nature of borders, physical and internal, seen and unseen. Reflecting again on the "thin places" to be found in the north of Ireland (and elsewhere), she writes:

"My grandfather was born in the same week as the Irish border. He was a storyteller, and his most affecting tales, the ones he gave me that have shaped his life, where about place, about how we relate to it, to ourselves, and to one another. Good seanchaidhthe -- storytellers -- never really tell you anything, though. They sit by the fire in the hearth; they draw the chairs in close; they shut all the windows so the old lore doesn't fall on the wrong ears. They fill the room with a sense of ease, a sense of all being as it should be. The words, when they spill quietly out of the mouth of the one who has been entrusted with them, dance in the space, at one with the flames of the fire. It is, as always, up to those who listen to do with them what they will.

"The stories he shared were fleeting, unbidden; they came and went as quickly as the bright, defiant end sparks of a fire, well on its way to going out. The stories, those glowing embers of words, were about places that were known to hide away, sometimes from all view. As if their locations are to be found in between the cracks, or floating above the grey Atlantic. Places that he mostly didn't even have names for but that he could conjure up as though they were right there in the same room. He called such places 'skull of a shae'. Now, I have come to think of the shae as 'shade', a nod to the almost ghost-like nature he saw such places as having. The places he spoke of seemed to scare him, a wee bit, or maybe it was talking about them that unsettled him. He came from a strict and hard background that allowed very little room for the voicing of much beyond the grind of being alive. I will remember, always, how he spoke of paths, particularly ones he found when walking across the border from Derry into Donegal. Paths on which friends and he had seen and heard things they were never really able to understand.

"The places he spoke of were locations where people felt very different from how they normally do. Places from which people came away changed. In these places you might experience the material and spiritual worlds coming together. Blood, worry and loss might sit together under the same tree as silence, stillness and hope. He spoke, not often but with raw honesty, of places where people had found answers and grace, where they had learned to forgive, where they had made peace and room for healing. Places where a veil is lifted away and light streams in, where you see a boundary between worlds disappear right before your eyes, places where you are allowed to cross any borders and boundaries have no sway. Lines and circles, silence and stillness -- all is as it should be for that flickering gap in time. He never named the places, of course, and the first time he brought me to one -- Kinnagoe Bay -- on a soft, pink August afternoon in the late 1980s, he never spoke of any of this at all. He quietly read his magazine about pigeon racing, poured my granny's tea, and let me be."

If you need any more persuasion to seek out N�� Dochartaigh's remarkable book, I recommend reading her essay "," found online at The Clearing (Little Toller Books).

The art today is from Irish Fairy Tales by James Stephens, illustrated by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939).

The passage quoted above is from Thin Places by Kerri n�� Dochartaigh (Canongate, 2021); all rights reserved by the author. The illustrations by Arthur Rackham were first published by Macmillan in 1920, and are now in public domain.

July 22, 2021

Recommended reading: Thin Places

One of the very best books I've read this year is Thin Places by Kerri n�� Dochartaigh, a volume born from the edgelands between nature writing and memoir, but also well rooted in folklore, myth, and history.

At the core of the text is N�� Dochartaigh's account of growing up in Northern Ireland during the violent years of the Troubles, of her subsequent flight from the land of her birth, and of her eventual return. Although the story is necessarily dark, the telling is made luminous by the author's exquisite prose, shot through with flashes of bright connection to the twinned worlds of myth and nature.

Here's a taste of Thin Places:

"What does it mean to come from a hollowed-out place? From a place that is neck-deep in the saga of loss? ... What effect does where you come from, and what that land has been through, have on the map of your self? How deeply can a person feel the fault lines of their home running through their own veins?

"In Celtic lands it is not unusual to use the landscape as a mnemonic map. Geographical features hold a particular importance for our history, beliefs and culture -- places make up the lines of our very being. There is an understanding that we are part of and not separate from the land we inhabit. Celtic legends place the natural world at the very heart of story, maybe even inside its bones. In such stories things in the natural world can possess a spirit and presence of their own; mountains, rocks, trees, rivers -- all things of the land and the sea -- sing their own lament. Locations can be associated with a particular warrior, hero or deity. Places are tied to stories by threads that uncoil themselves back beyond known history, passed on through oral tradition, only some of which have been written down.

"Amongst these geographical features, whether manmade -- such as ancient mounds and standing stones -- or naturally created features, it is not unusual for some to be associated with the worship of pre-Christian deities. The aos s�� (or aes s��dhe) is an Irish term for a race that is other than human, that exists in Irish, Scottish and Manx mythologies, inhabiting an invisible world that sits in a kind of mirroring with our own. They belong to the Otherworld, Aos S�� -- a world reached through mist, hills, lakes, ponds, springs, loughs, wetland areas, caves, ancient burial sites, cairns and mounds. The island from which I come had no choice, really, than to find a name for these dancing, beating, healing places where the veil between so very many things is thin, where it has been known to lift, right before our humble, grateful eyes.

"The folklore of almost every culture holds room for these liminal spaces -- those in-between spaces -- those unnameable places, not to be found on any map. Are these thin places spaces where we can more easily hear the land, the earth, talking to us? Or are they places in which we are able to feel more freely our own inner selves? Do such places as these therefore hold power?

"We have built up a narrative over many years -- decades, centuries? -- of 'nature' as 'other'. There is so much separation in the language we use with each other; we seek to divide humanity from its own self again and again, and this has naturally bled into how we view the land and water that we share with one another -- and with other species. What do we mean when we talk about 'nature'? About 'place'? I want to know what it all means. I need to try to understand. When we are in a place where the manmade constructs of the world seem as though they have crumbled, where time feels like it no longer exists, that feeling of separation fades away. We are reminded, in the deepest, rawest parts of our being, that we are nature. It is in us and of us. We are not superior or inferior, separate or removed; our breathing, breaking, ageing, bleeding, making and dying are the things of this earth. We are made up of the materials we see in the places around us, and we cannot undo the blood and bone that forms us.

"In thin places people often say they experience being taken 'out of themselves', or 'nearer to god'. The places I return to over and over -- both physically, and in my memory -- certainly do hold the power to make me feel light and hopeful, as though I am not quite of this world. Of much more power, though, is the way in which these places leave me feeling rooted -- as utterly and completely in the landscape as I ever feel, as much a part of it as the bones and excrement that lie beneath my feet, as the salt and silt that course through the water. For me, it is in this that the absolute and unrivalled beauty of thin places lie."

Thin Places is one of those books that I long to buy multiple copies of and gift to everyone I know. It's a beautiful book, and a timely one. I urge you to seek it out.

For another slant on "thin places," have a listen to Philip Marsden on Scotland Outdoors (BBC Sounds) discussing The Summer Isles, his book about the wild western coasts of Ireland and Scotland. Go here for the interview, and start at the 29:50 mark.

The glorious stained glass art today is by Tamsin Abbott, based in rural east Herefordshire. Tamsin received a first class degree in English literature from Stirling University (where she specialised in the medieval period); she then returned to school to study art at Gloucester College of Art and Technology, and trained in stained glass at Hereford College of Art and Design. Her work has been featured in Country Living, on Country File, and is sold in galleries and shops across the UK.

"I have always been influenced (and almost obsessed) by nature," she says, "but most specifically animals, continuously drawing and painting them; for a long time I dreamed of speaking with them, and of being absorbed into their world in a way that seemed more natural to me than this human community. I don���t think I am alone in this as I find that this animal ���spirit��� speaks directly to others too. However, I am also inherently inspired by the idea of myth and legend as well as fairytale and medieval romances, and the sense that our ancestors, who inhabited this land, have left an imprint on it throughout the ages. I also love the idea of the timelessness of the cosmos that overarches everything now as it would have done since time before humanity. It is the intermeshing of all these things that contribute towards my internal universe which I hope manifests in my work.

"I have always been influenced (and almost obsessed) by nature," she says, "but most specifically animals, continuously drawing and painting them; for a long time I dreamed of speaking with them, and of being absorbed into their world in a way that seemed more natural to me than this human community. I don���t think I am alone in this as I find that this animal ���spirit��� speaks directly to others too. However, I am also inherently inspired by the idea of myth and legend as well as fairytale and medieval romances, and the sense that our ancestors, who inhabited this land, have left an imprint on it throughout the ages. I also love the idea of the timelessness of the cosmos that overarches everything now as it would have done since time before humanity. It is the intermeshing of all these things that contribute towards my internal universe which I hope manifests in my work.

"Behind all this inspiration the underlying sense of what I am trying to portray is how much life goes on around us constantly but outside our awareness. Be it a shrew foraging for its young in the hedgerow as we walk by, or a giant spirit dragon that soars above us in the night sky. Conversely, I also wish to capture a sense of the magic of the everyday in my work; the sacred washing line, the reverential bonfire, the glory of a scrap of garden."

To learn more about her work, please visit Tamsin's website, or read an interview with the artist here.

The passage quoted above is from Thin Places by Kerri n�� Dochartaigh (Canongate, 2021); all rights reserved by the author. The stained glass art is by Tamsin Abbott; all rights reserved by the artist.

July 20, 2021

There and back again

I've recently returned from a week of woodland wandering, and I'm still feeling betwixt and between: moving from the mythic realms back into ordinary life (with its own ordinary magic). I've been camping in the hills just south of here as part of Songdreaming for Albion, led by Sam Lee and Chris Salisbury: a deep dive into the folk songs and tales of Dartmoor, listening for the songlines of the moor, and "recalibrating how we engage with the land and converse with our brother/sister nations of plants, trees and beings."

Tales were told. Songs were sung. Food was cooked on open fires and music shared till the midnight hours. Dartmoor blessed us with dry, clear days and star-filled nights (never a given here). Then Howard and Tilly fetched me and brought me over the hills and home.

In myth, the safe return from the woods (or the mountainside, or the spirit world) often marks a time of new beginnings: fresh starts, new paths, or lives newly illuminated by gifts brought back from the Otherland. Thomas the Rhymer, in the old Scottish ballad, returns to the mortal realm after seven years with the Faerie Queen bearing the gift of prophesy. Merlin returns from his time of exile and madness in the forests of Wales with new magical abilities and the gift of speaking with animals. Odin hangs in a death-like trance for ten days from the world-tree Yggdrasil, and comes back with the secret of runes from the dark land of Niflheim. I haven't come back with anything so grand as runes or prophesy -- but songs and dreams and spiderwebs of wild connection are just as precious, and as necessary.

I took no camera, no computer, no phone -- nothing between me and the moss green world -- so I have no photographs from the week to share with you. Instead, the pictures in this post are by my old friend David Wyatt -- who was, until just recently, a neighbour of ours here on the moor. There are many ways into the Dreaming, and art-making is one of them.

Song, as I learned again last week, is another...and perhaps the most direct of all.

The art above: Beech Whisperer, Old Goat's Home, and a rough sketch (in preparation for a painting) by David Wyatt. All rights reserved by the artist.

July 11, 2021

Myth & Moor (and Tilly) update

I'm heading off on a mythic journey this week, exploring the folk songs, folk tales, and folk spirit of Dartmoor with Sam Lee, Chris Salisbury, Charlotte Pulver and other good folks. I'll be offline and out of reach for the duration, but I'll tell you more about it when I get back.

Tilly, meanwhile, is still on the mend; and although she's a lot better and brighter, it's hard for me to leave her. (It's always hard, but especially now.) She'll be here at home, looked after (and terribly spoiled, no doubt) by family members. I'll miss my little black shadow.

Myth & Moor will be return on Monday, 19 July. Have a good week, everyone.

Art by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939) and Charles Robinson (1870-1937).

July 10, 2021

Words and worlds

As a coda to this week's posts on Alison Lurie (focused on her two collections of essays on children's fiction), I'd like to also recommend her final collection, Words and Worlds: From Autobiographies to Zippers (2019). The works gathered in this volume range from personal reflections to explorations of theatre, literature, and clothes (including, yes, zippers) -- plus some pieces on fairy tales and children's books that didn't appear in the previous collections.

The book opens with "Nobody Asked You to Write a Novel," an account of Lurie's long, dispiriting journey to a professional writing career -- a piece so good that I wish she'd left us with a book-length memoir as well. (The title comes from her husband's curt response to her despair when publisher after publisher rejected her early work.) Later, Lurie writes about friends in her literary circle with candor, affection, and a deliciously understated humor. Here, for example, is a brief, bright portrait of Shirley Jackson from an essay on "Witches Old and New":

"Over the years I have met many people who considered themselves to be witches and/or worshippers of a female deity, whom they usually referred to as The Goddess. They were of every age and social class, and of both sexes -- though, as in the witch trials of the 16th and 17th centuries, women predominated. With one exception, all claimed that they were good, or white, witches, and worked only for positive ends. They celebrated the seasons of the year and the power and glory of nature. They cast spells to find lost objects; to bring health, wealth, love, happiness, and peace of mind to themselves and their friends; and occasionally to block the evil or misguided actions of institutions such as the Internal Revenue Service, the Pentagon, and Cornell University.

"The one witch I've known who admitted to a less benign use of her magic arts was the writer Shirley Jackson, best remembered now for her brilliant and frightening short story 'The Lottery.' She did not always claim to be a witch, but she also did not deny it, sometimes giving examples. At one time, she told me, she and her husband, the critic Stanley Edgar Hyman, were extremely annoyed by his publisher, Alfred Knopf. 'Unfortunately, my powers do not extend to New York State,' she informed his secretary and several other acquaintances. 'But let him be warned. If he enters my territory, Vermont, evil will befall him.'

"The warning was passed on; but several weeks later, rashly disregarding it, Knopf took a train to Vermont to go skiing. The first day he was out on the slopes, Jackson said, he fell and broke his leg. After emergency medical treatment, he was helped onto another train and returned to his territory, Manhattan."

Another example comes from her marvellous essay on writer and artist Edward Gorey (1925-2000), a close friend throughout their adult lives. (All of the art in this post is "Ted" Gorey's.) Lurie writes:

"The Doubtful Guest, which was dedicated to me under my married name at the time, Alison Bishop, appeared in 1957. It recalls a remark I made to Ted when John [Lurie's son] was less than two years old. I said that having a young child around all the time was like having a houseguest who never said anything and never left. This, of course, is what happens in the story. The Doubtful Guest appears out of nowhere. It is smaller than anyone else; it has a 'peculiar appearance' at first and does not understand language. As time passes, it becomes greedy and destructive: it tears pages out of books, has temper tantrums, and walks in its sleep. Yet nobody even tries to get rid of the creature. It is just always there. It sits around, or moves from room to room, and it always wears sneakers. The attitude of the other characters towards it remains one of resigned acceptance.

"Who is this Doubtful Guest? The last page of the story makes everything clear:

It came seventeen years ago -- and to this day

It has shown no intention of going away.

"Of course, after about seventeen years most children leave home. The Doubtful Guest is a child, and since the book was published many mothers have recognized this. My own Doubtful Guest left home at eighteen, and now is over sixty. He still comes to visit, but he always has plenty to say, and often I think he leaves too soon, so there is hope for anyone who has this kind of guest in their own home right now."

Lurie, as most readers know, was a Pulitzer-Prize-winning novelist as well as a fine nonfiction writer and scholar. She died in December, 2020, at the age of 94 -- a true loss to the fields of adult and children's literature alike.

The passages above are quoted from "Witches Old and New" and "Edward Gorey" by Alison Lurie, published in Words and Worlds (Delphinium Books, 2019); all rights reserved by the Lurie estate. The art above is by Edward Gorey; all rights reserved by the Gorey estate.

July 9, 2021

Alison Lurie on the modern magic of E. Nesbit

I'd like to end the week with one more passage from Alison Lurie's writings on children's books, this time from her essay on E. Nesbit (1858-1924), published in Don't Tell the Grown-ups: The Subversive Power of Children's Literature:

"Victorian literary fairy tales tend to have a conservative moral and political bias. Under their charm and invention is usually an improving lesson: adults know best; good, obedient, patient, and self-effacing little boys and girls are rewarded by the fairies, and naughty assertive ones are punished. In the most widely read British authors of the period -- Frances Browne, Mrs. Craik, Mrs. Ewing, Mrs. Molesworth, and even the greatest of them all, George MacDonald -- the usual manner is that of a kind lady or gentleman delivering a delightfully disguised sermon. Only Lewis Carroll's Alice books completely avoid this didactic tone....

In the final years of Victoria's reign, however, an author appeared who was to challenge this pattern so energetically and with such success that it is possible now to speak of juvenile literature as before and after E. Nesbit. Although there are foreshadowings of her characteristic manner in Charles Dicken's "Holiday Romance" and Kenneth Grahaeme's The Golden Age, Nesbit was the first to write at length for children as intellectual equals and in their own language. Her books were startlingly innovative in other ways: they took place in contemporary England and recommended socialist solutions to its problems; they presented a modern view of childhood; and they used magic both as a comic device and as a serious metaphor for the power of the imagination. Every writer of children's fantasy of since Nesbit's time in indebted to her -- and so are some authors of adult fiction."

A little later in the text, Lurie returns to the subject of magic in Nesbit's work:

"Though we tend to take it for granted, the importance of magic in juvenile literature needs some explanation. Why, in a world that is so wonderful and various and new to them, should children want to read about additional, unreal wonders? The usual explanation is a psychological one: magic provides an escape from reality or expresses fears and wishes. In the classic folktale, according to this theory, fear of starvation becomes a witch or wolf, cannibalism an ogre. Desire shapes itself as a pot that is always full of porridge, a stick that will beat one's enemies on command, a mother who comes back to life as a benevolent animal or bird. Magic in children's literature, too, can make psychological needs and fears concrete; children confront and defeat threatening adults in the shape of giants, or they become supernaturally large and strong; and though they cannot yet drive a car, they travel to other planets.

"Magic can do all this, but it can do more. In the literary folktale, it becomes a metaphor for the imagination. This is particularly true of Nesbit's stories. The Book of Beasts, for instance, can be read as a fable about the power of imaginative art. The magic volume of its title contains colored pictures of exotic creatures, which become real when the book is left open. The little boy who finds it releases first a butterfly, then a bird of paradise, and finally a dragon that threatens to destroy the country. If any book is vivid enough, this story says, what is in it will become real to us and invade our world for good or evil.

"It is imagination, disguised as magic, that gives Nesbit's characters (and by extension her readers) the power to journey through space and time: to see India or the South Seas, to visit Shakespeare's London, ancient Egypt, or a future Utopia. It will even take them to Atlantis or to a mermaid's castle under the sea. All these places, of course, are the traditional destinations of fantasy voyages, even today. But an imagination that can operate only in conventional fantasy scenery is in constant danger of becoming sentimental and escapist. At worst, it produces the sort of mental condition that manifests itself in plastic unicorns and a Disney World version of foreign countries. True imaginative power like Nesbit's, on the other hand, is strong enough to transform the most prosaic contemporary scene, and comedy is its best ally. Nesbit's magic is as much at home in a basement in Camden Town as on a South Sea island, and it is never merely romantic. Though it grants the desires of her characters, it may also expose those desires as comically misconceived. Five Children and It, for instance, is not only an amusing adventure story but also a tale of the vanity of human -- or at least juvenile -- wishes. The children first want to be 'as beautiful as the day'; later they ask for a sand pit full of gold sovereigns, giant size and strength, and instant adulthood. Each wish leads them into an appropriate comic disaster....

"It is also possible to see the magic in Nesbit's tales as the metaphor for her own art. In many of her fantasies the children begin by using supernatural power in a casual, materialistic way: to get money and to play tricks on people. Gradually they find better uses for magic: in The Story of the Amulet, to unite the souls of an ancient and modern scholar, and at the end of The Enchanted Castle, to reveal the unity of all created things. Nesbit, similarly, first used her talents to produce hack work and pay the bills; only much later did she come to respect her gift and write the books for which she is still remembered.

"Nesbit's magic can also be read as a metaphor for imaginative literature in general. Those who possess supernatural abilities or literary gifts, like the Psammead of Five Children and It, are not necessarily attractive or good-tempered; they may be ugly, cross, or ridiculous. We do not know who will be moved by even the greatest works of art, nor how long their power will last; and the duration and effect of magic in Nesbit's stories in unpredictable in the same way.

Certain sorts of people remain untouched by it, and it is often suspected of being a dream, a delusion, or a lie. The episode of the Ugly-Wuglies also suggests that things carelessly given life by the imagination may become frightening and dangerous; the writer may be destroyed by his or her second-rate creations -- by the inferior work that survives to debase reputation, or by some casual production that catches the popular imagination and types its creator forever.

"Also, though they were written [over a century ago], Nesbit's books express a common anxiety of writers today: that the contemporary world, with its speed of travel and new methods of communication, will soon have no use for literature. As practical Jimmy puts it in The Enchanted Castle: 'I think magic went out when people began having steam engines...and newspapers, and telephones and wireless telegraphing.

[image error]"New as Nesbit's stories are in comparison with most children's books of her period, in some ways they also look back to the oldest sort of juvenile literature, the traditional folktale. They recall the simplicity and directness of diction, and the physical humor, of the folktale rather than the poetic language, intellectual wit, and didactic intention of the typical Victorian fairy tale. Socially, too, Nesbit's stories have affinities with folklore. Her adventurous little girls and athletic princesses recall the many traditional tales in which the heroines have wit, courage, and strength....There is no way of knowing whether E. Nesbit went back to these traditional modes consciously, or whether it was her own attitude toward the world that made her break so conclusively with the past. Whatever the explanation, she managed not only to create some of the best children's books ever written, but to quietly popularize ideas about childhood that were, in her time, extremely subversive. Today, when the words of writers like Mrs. Ewing and Mrs. Molesworth and Mrs. Craik are gathering dust on the shelves of second hand bookshops, her stories are still being read and loved by children, and imitated by adults."

For more about Edith Nesbit herself, who lived a radical and fascinating life, I recommend The Lives and Loves of E. Nesbit by Eleanor Fitzsimons. It is, hands down, the best of the Nesbit biographies. Also, A.S. Byatt's splendid novel The Children's Book owes more than a little to Nesbit, her complicated marriage, and her social circle.

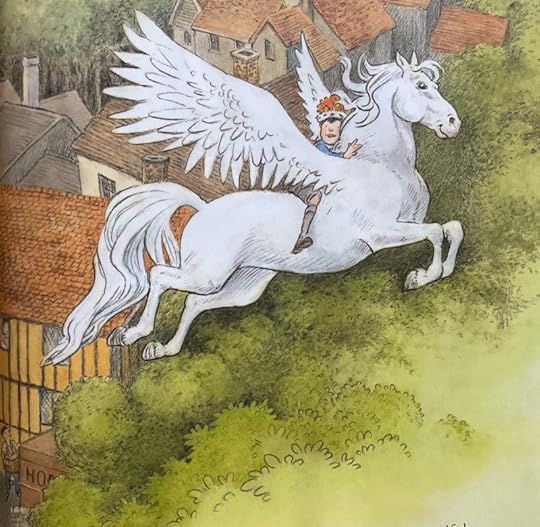

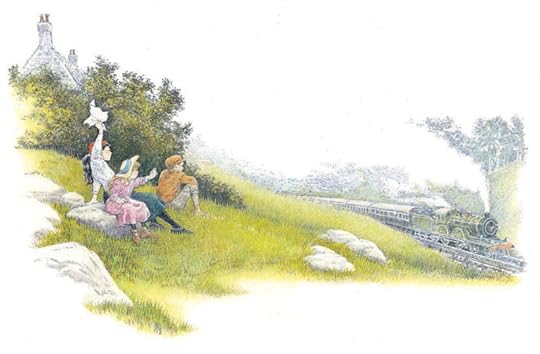

The art today: color illustrations for Nesbit's The Book of Beasts and The Railway Children by Inga Moore; and pen-and-ink drawings by H.R. Millar (1869-1942) from the first edition of Five Children and It (1902).

The passage about is quoted from "Modern Magic" by Alison Lurie, published in Don't Tell the Grown-ups (Little, Brown & Co., 1990). All rights reserved by the Alison Lurie estate. All rights to the color art above reserved by Inga Moore. The H.R. Millar drawings are in Public Domain.

July 8, 2021

Alison Lurie on ''The Oddness of Oz''

Here's another passage from Alison Lurie, this time on the The Wizard of Oz and its sequels by L. Frank Baum (1856-1919). It's from her in-depth essay on Baum, "The Oddness of Oz," originally published in The New York Review of Books and reprinted in Boys and Girls Forever: Children's Classics from Cinderella to Harry Potter:

"Though the Oz books have always been read by children of both sexes, they have been especially popular with girls, and it's not hard to see why. Oz is a world in which women and girls rule; in which they don't have to stay home and do housework, but can go exploring and have adventures. It is also, as Joel Chaston has pointed out, a world in which none of the major characters have a traditional family. Instead, most of them live alone or with friends of the same sex. The Scarecrow stays with the Tin Woodman in his castle for months at a time, while Ozma, Dorothy, Betsy, and Trot all have rooms in the palace of the Emerald City, and Glinda lives in a castle with 'a hundred of the most beautiful girls of the Fairyland of Oz.'

"The appeal of Oz seems even clearer if it is contrasted to that of contemporary books for girls. In the early years of the 20th century, the heroes of most adventure stories were boys; girls stayed home and learned to get on better with their families. If they were rejected children like Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm, or orphans like Anne of Green Gables and Judy in Daddy-Long-legs, they found or established new families. At the end of all these stories, or their sequels, the heroine grew up, fell in love, and got married.

"There was of course already another famous little girl protagonist who had adventures in a magical world: Lewis Carroll's Alice. But from the point of view of most child readers (including me) her experiences were less attractive. Unlike Dorothy and Ozma, who collect loving friends and companions on their journeys, Alice travels alone, and the strange creatures she meets are usually indifferent, self-absorbed, hostile, or hectoring. Rather than helping her, as Dorothy's companions do, they make unreasonable demands: she is to hold a screaming baby, do impossible math problems, and act as a ladies' maid. One or two of the characters seem to wish her well in a helpless way, like the White Knight, whom many readers have seen as a stand-in for Carroll himself. Moreover Wonderland, unlike Oz, turns out to be only a dream.

"Most children, though they may enjoy Alice's adventures, don't want to visit Wonderland, which is full of disappearing scenery and dangerous eccentrics, some of them clearly quite insane. They prefer Oz, where life is all play and no work, and all adventures end happily.

"To some extent Baum's endorsement of escapism was hidden -- disguised as a light-hearted fantasy, with a series of sweet, pretty-little-girl protagonists, the most famous of whom at first declares that all she really wants is to go home to flat, gray Kansas and see her dull, deeply depressed Uncle Henry and Aunt Em again. But, as anyone knows who has read even a few of Baum's later Oz books, Dorothy may return to Kansas after her adventures, but she doesn't stay there very long -- somehow, a natural disaster (shipwreck, earthquake, whirling highways) always appears to carry her

back to Oz and the magical countries that surround it. She spends more and more time there, and has more adventures.

"Finally, in the fifth volume of the series, Dorothy not only moved to Oz permanently, but arranges for Uncle Henry and Aunt Em (whose failing farm is about to be repossessed by the bank) to join her there. Yes, you can escape from your dreary domestic life into fairyland, Baum's books say: you can have exciting but safe adventures, make new friends, live in a castle, never have to do housework or homework, and -- most important of all -- never grow up.

"This subversive message may be one of the reasons that the Oz books took so long to be accepted as classics. For more than half a century after L. frank Baum discovered it in 1900, the Land of Oz had a curious reputation. American children by the thousands went there happily, but authorities in the field of juvenile literature, like suspicious and conservative travel agents, refused to recommend it or even handle the tickets. Librarians would not buy the Oz books, schoolteachers would not let you write reports on them, and the best-known histories of children's books made no reference to their existence. In the 1930s and 1940s they were actually removed from many schools and libraries.

"As a child I had to save my allowance to buy the Oz books, because the local library refused to carry them. This censorship was justified at the time by pointing out that the books were not beautifully written and that the characters were two-dimensional. This is arguable, but it has not prevented many other less stylistically perfect children's books of the period from being admired and recommended. It seems more likely that in the dark years between the first and second waves of American feminism, critics recognized the subversive power of Baum's creation. Not until recently did the Oz books enter the canon."

For me, this passage captures the flavor of Lurie's writings on children's literature perfectly: I constantly find myself arguing with her essays (for example, with her sweeping and America-centric statement that most children prefer the Land of Oz to Wonderland), and yet I constantly learn from her too. She is exasperating and brilliant in equal measure, and I treasure her books despite the number of times I have wanted to chuck them across the room. Thus I highly recommend Boys and Girls Forever, and Lurie's earlier collection of children's literature essays, Don't Tell the Grown-ups. I may not always agree with Lurie's conclusions, but the range of her knowledge is impressive and her prose is delightful.

The charming imagery today is from The Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum, illustrated by Austrian book artist Lisbeth Zwerger (North-South Books, 1996).

The passage about is quoted from "The Oddness of Oz" by Alison Lurie, published in Boys and Girls Forever (Vintage, 2004). All rights to the art and text in this post are reserved by Lisbeth Zwerger and the Alison Lurie estate.

July 7, 2021

Alison Lurie on The Secret Garden

Another writer I've been re-reading recently is novelist and academic Alison Lurie (1926-2020), whose essays on children's literature I sometimes love and sometimes argue with, but always find interesting. Here, for example, is a passage from "Enchanted Forests and Secret Gardens: Nature in Children's Literature," published in Boys and Girls Forever: Children's Classic from Cinderella to Harry Potter:

"When I was seven years old, my family moved to the country, and my perception of the world entirely altered. I had been used to regular, ordered spaces: labeled city and suburban streets and apartment buildings and parks with flat rectangular lawns and beds of bright 'Do Not Touch' flowers behind wire fencing. Suddenly I found myself in a landscape of thrilling disorder, variety, and surprise.

"As the child of modern, enlightened parents I had been told that many of the most interesting characters in my favorite stories were not real: there were no witches or fairies or dragons or giants. It had been easy for me to believe this; clearly, there was no room for them in a New York City apartment building. But the house we moved to was deep in the country, surrounded by fields and woods, and there were cows in the meadow across the road. Well, I thought, if there were cows, which I'd seen before only in pictures, why shouldn't there be fairies and elves in the woods behind our house? Why shouldn't there be a troll stamping and fuming in the loud, mossy darkness under the bridge that crossed the brook? There might even be one or two small hissing and smoking dragons -- the size of teakettles, as my favorite children's author, E. Nesbit, described them -- in the impenetrable thicket of blackberry briars and skunk cabbage beyond our garden.

"No longer a rationalist, I began to believe in what my storybooks said. Suddenly I saw the landscape as full of mystery and possibility -- as essentially alive. After all, this was not surprising: it was the way most people saw the natural world for thousands of years, and it was the way it was portrayed in the stories I loved best."

One of those stories was The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett (1849-1924):

"Consciously or unconsciously, many of the authors of classic children's books are pantheists. For them nature is divine, and full of power to inspire and heal. But while for some nature must be sought in the enchanted forest, for others the magical location is a garden. In their books, to go into a garden is often the equivalent of attending a Sunday service, and gardening itself may become a kind of religious act.

"For Frances Hodgson Burnett, nature was intrinsically healing. She herself was a dedicated gardener, the author of a how-to book about her own garden on Long Island. In her famous children's story The Secret Garden (1911) two extremely neurotic, unattractive, and self-centered children are transformed by a combination of fresh air, do-it-yourself psychology, and, most of all, the discovery and restoration of a long-abandoned rose garden.

"When we meet Mary Lennox in India, she is a sickly, disagreeable child whose selfish, beautiful mother never had any interest in her. No one has ever loved her and and she loves no one. But even then, to amuse herself, she plays at gardening, sticking scarlet hibiscus flowers into the bare earth. Later, after both her parents are dead, she is sent home to England, and then to Misselthwaite Manor on the Yorkshire Moors, which she hates at first sight. Things begin to improve when she is send outdoors to play:

" '...the big breaths of fresh air blown over the heather filled her lungs with something which was good for her whole thin body and whipped some red color into her cheeks and brightened her dull eyes....'

"Eventually Mary discovers the secret garden of the title. For years, like Mary herself, it has been confined and neglected. Then, as winter turns to spring, she begins to restore it, to weed and water and prune and plant, and in the process is herself restored to happiness and health. Later she is assisted in her task by a local boy, Dickon, and by her cousin Colin, who has spent most of his years indoors.

Colin's mother died when he was born, and he has been brought up to believe that he is a crippled invalid. Yet he too is transformed and restored to health in the garden.

"Sometimes in children's books the power of nature is embodied in a character, and Dickon in The Secret Garden is the most famous of these characters. Though he is only twelve years old, rough and uneducated, he is a kind of rural Pan, who spends most of his time, winter and summer, out on the moor. He can charm birds and animals by playing on his pipe, and knows all about plants -- his sister says he 'can make a flower grow out of a brick walk...he just whispers things out o' th' ground.' It is Dickon who teaches Mary and Colin how to bring the secret garden back to life and he is the first to declare that nature has spiritual powers; he calls it Magic.

" 'Everything is made out of Magic,' [Colin says] 'leaves and trees, flowers and birds, badgers and squirrels and people. So it must be all around us.' "

Indeed it is.

The imagery today is from The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett, illustrated by Inga Moore (Walker Books, 2007). Go here for a good interview with this wonderful artist.

The passage about is quoted from Boys and Girls Forever by Alison Lurie (Vintage, 2004). All rights to the art and text in this post are reserved by Inga Moore and the Alison Lurie estate.

July 6, 2021

Recommended reading: The Magician's Book

Last week I met a friend in our village churchyard (an outdoor, Covid-safe setting) to talk about Narnia, prompted by our reading of From Spare Oom to War Drobe: Travels in Narnia With My Nine Year-Old Self by Katherine Langrish, among other C.S. Lewis-related works. During our long, rich conversation, I was reminded of an earlier volume: The Magician's Book: A Skeptic's Adventures in Narnia by Laura Miller, published back in 2008 -- so I went home and pulled the book off the shelf to give it a second read.

In The Magician's Book (as in the new Langrish volume), Miller examines her personal relationship with the Chronicles; explores C.S. Lewis's life and literary influences; and casts a shrewd eye over the underlying themes of the Narnia sequence. The two authors cover similar ground and yet these are two markedly different books -- largely because Miller (raised in California) and Langrish (raised in the north of England) had very different lives as children and are very different writers today: one a literary critic, and one a folklorist and author of children's fiction. Each of the books has its clear strengths and to chose between them comes down to personal taste. For me, the Narnia evoked by Langrish is closer to the land I knew in my own youth -- and yet, reading Miller's text brings strong flashes of recognition too. She is particularly insightful on the differences between Lewis's and Tolkien's work, on the syncretism of Lewis's imagination, and on the influence of William Morris on the early fantasy genre as a whole. The chief difference between these two paeans to Narnia is that Miller views the Chronicles through a distinctly American lens, Langrish through an English one; thus reading their books in tandem makes for a rather interesting conversation between them.

In The Magician's Book (as in the new Langrish volume), Miller examines her personal relationship with the Chronicles; explores C.S. Lewis's life and literary influences; and casts a shrewd eye over the underlying themes of the Narnia sequence. The two authors cover similar ground and yet these are two markedly different books -- largely because Miller (raised in California) and Langrish (raised in the north of England) had very different lives as children and are very different writers today: one a literary critic, and one a folklorist and author of children's fiction. Each of the books has its clear strengths and to chose between them comes down to personal taste. For me, the Narnia evoked by Langrish is closer to the land I knew in my own youth -- and yet, reading Miller's text brings strong flashes of recognition too. She is particularly insightful on the differences between Lewis's and Tolkien's work, on the syncretism of Lewis's imagination, and on the influence of William Morris on the early fantasy genre as a whole. The chief difference between these two paeans to Narnia is that Miller views the Chronicles through a distinctly American lens, Langrish through an English one; thus reading their books in tandem makes for a rather interesting conversation between them.

Having already given you a taste of From Spare Oom to War Drobe, here's a snippet from The Magician's Book. In an early chapter, Miller writes of her young passion for Narnia:

"Do the children who prefer books set in the real, ordinary, workaday world ever read as obsessively as those who would much rather be transported into other worlds entirely? Once I began to confer with other people who had loved the Chronicles as children, I kept hearing stories, like my own, of countless, intoxicated re-readings. 'I would read other books of course,' wrote the novelist Neil Gaiman, 'but in my heart I knew that I read them only because there wasn't an infinite number of Narnia books.' Later, when I had the chance to talk with him about the Chronicles in person, he told me, 'The weird thing about the Narnia books for me was that mostly they seemed true. There was a level on which I was absolutely willing at age six, age seven, to accept them as a profound and real truth. Unquestioned, there was definitely a Narnia. This stuff had happened. These were reports from a real place.'

"Most of us persuaded our parents to buy us boxed sets of all seven Chronicles, but I also saved up my allowance and occasional small cash gifts from relatives to buy a hardcover copy of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, one of the few times in my life I've ever succumbed to the collector's impulse....This was not about obtaining a possession, but about securing a portal. I was not yet capable of thinking about it in this way, but I'd been enthralled by the most elementary of readerly metaphors: A little girl opens the hinged door of some commonplace piece of household furniture and steps through it into another world. I opened the hinged cover of a book and did the same.

"Why did I fall so hard and so completely, and why was a land of fauns and centaurs and talking animals so exactly what I wanted to read about? Not long ago, a friend told me about her nine-year-old daughter's infatuation with Narnia. My friend had grown up loving historical novels about 'prairie girls,' and while she didn't disapprove of her daughter's appetite for fantasy, it baffled her. 'I just don't get it,' she complained.

"If you had asked me at the same age why I liked The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe better than, say, Little Women or any other story that was about lives more like my own, I wouldn't have been able to answer; it seemed crazy to prefer anything else. The best analogy I can make is a corny one, to the film version of The Wizard of Oz and that famous moment when Dorothy ventures out of the drab, black-and-white farmhouse that's carried her all the way from drab, black-and-white Kansas and into the Technicolor of Oz. Who in her right mind would poke her head out for just a sec, then slam the door shut, and shout, 'Take me back to Kansas'?

"Once upon a time, people used to label the kind of book I would come to crave -- the kind 'with magic,' as I usually thought of it -- as escapist. Consequently, readers with this taste often have a chip on their shoulders. Lewis, who enjoyed the occasional H. Rider Haggard adventure or H.G. Wells novel in addition to Anglo-Saxon epics and medieval allegories, wrote several essays defending science fiction and 'fairy tales' from the scornful advocates of stringent realism. I, on the other hand, came up in the age of metafiction, postmodernism, and magic realism; realism no longer commands all the prestige. Lewis's arguments on behalf of fantastic literature feel a bit superfluous to me. Still, I can hazily remember, long ago, having adults -- librarians, friends' parents -- suggest to me that I liked books 'with magic' because I wanted to escape from a reality that, by implication, I lacked the gumption to face. Perhaps this still happens, say, to kids who obsess about Harry Potter. Or perhaps adults are now so thankful to see children reading that they don't quibble with the books they choose.

"Did I use storybooks to get away from my life? Of course I did, but probably no more so than the kids who chose Harriet the Spy instead of books about dragons and witches. (For the record, I read and liked Harrriet the Spy, too.) Insofar as they are stories at all, all stories are escapes from life; all stories are unrealistic, or at least all of the good ones are. Life, unlike stories, has no theme, no formal unity; and (to unbelievers, at least) no readily apparent meaning. That's why we want stories. No art form can hope to exactly reproduce the sensations that make up being alive, but that's OK: life, after all, is what we already have. From art, we want something different, something with a shape and a purpose. Any departure a story might make from real-world laws against talking animals and flying carpets seems relatively inconsequential compared to this first, great leap away from reality. Perhaps that's why humanity's oldest stories are full of outlandish events and supernatural beings; the idea that a story must somehow mimic actual everyday experience would probably have seemed daft to the first tellers. Why even bother to tell a story about something so commonplace?

"There were particular fantastic elements that drew me to Narnia at that age, and they were not always what people associate with fairy tales. I disliked princesses and any other female whose chief occupation was waiting around to be rescued, but I also had no great interest in knights, swords, and combat. The Chronicles, which are relatively free of such elements, spoke to me across a spectrum of yearning. The youngest part of myself loved Narnia's talking animals. The girl I was fast growing into fiercely seized upon the idea of possessing an entire, secret world of my own. And the seeds of the adult I would become revelled in the autonomy of Lewis's child heroes and the adventures that awaited them once they escaped the wearying bonds of grown-up supervision."

"The Chronicles...spoke to me across a spectrum of yearning." That's such a wonderfully concise description of the power of the very best fantasy, pulling us into the worlds we long for without even knowing we do, recognizing them, somehow, from the very moment we step inside. The worlds "with magic": yes, that's what I longed for as a child too.

It's what I long for still. And find, in the realm of story.

Pictures: The paintings are from The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe by C.S. Lewis, illustrated by Michael Hague (Atheneum, 1983). All rights reserved by the artist. The photographs are of the "living churchyard" surrounding our village church, a community bio-diversity project. The church building is 13th century, with substantial portions rebuilt in the 15th.

Words: The passage quoted above is from The Magician's Book by Laura Miller (Little, Brown & Co., 2008). All rights reserved by the author.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 710 followers