Terri Windling's Blog, page 14

June 3, 2021

Recommended reading: Why Rebel

Jay Griffiths is one of a handful of writers that I more than admire, I am actively in awe of: writers whose work is so original and so damn good that I just don't know how they do it. Griffith's remarkable books (Wild, Kith, Pip Pip, and Tristimania especially) have stretched my mind, touched my heart, and taught to be perceive the world in new ways. She's braver in her life and prose than I could ever be, and I love her for it.

Her latest publication, Why Rebel, is a small, slim volume of eleven essays published in the "Penguin Special" series. The essays are tied together by the central theme of love for the wild earth, with a clear-eyed look at the forces that undermine our ability to live soulfully and sustainably on this beautiful, ailing planet. I've had my copy for just two weeks and already it's dog-eared, coffee-stained, and scribbled with margin notes. (I carry it on my walks with Tilly, so it's speckled with rain, mud, and leaf-mulch too.)

Griffith's essay "The Forests of the Mind" is one I keep returning to. Here, she discusses the poetic mindset of shamanism, its relationship to art, and the ways that the rise of literalism has eroded our understanding of metaphor, to our great cost. (This is something I've long been worried about too, and I'm glad I'm not the only one.) Shapeshifting, she says, is a metaphorical act performed by shamans and artists both:

"It is part of the repertoire of the human mind, cousin to mimesis, empathy and Keats's 'negative capability,' known to poets and healers since the beginning of time, the beginning of mime. It did not have literal truth, quite obviously, but had 'slanted, metaphoric truth' -- the words I used, when the page was printed, to describe it.

"Shapeshifting is a transgressive experience, a crossing over: something flickers inside the psyche, a restless flame in a gust of wind, endlessly transformative. The mind moves from its literal pathways to its metaphoric flights. Art is made like this, from a volatile bewitchment of self-forgetting and an identification with something beyond. Out of this is born a conviviality with everything alive, the relationship acknowledged and the necessity of its protection vouchsafed....We are what we think, and we humans have a way to become other, in a necessary, wild and radical empathy.

"Shapeshifting involves a willingness to makes mimes in the mind, copying something else. Art, meanwhile, depends on mimesis furthering our desire to know and to understand. In a recent, Ovidian, dance piece, Swan, French dancers performed and danced with live swans, imitating the birds in a mime which alluded to the metamorphosis of all art, and to the artists' ability to lose themselves in order to mirror this something beyond.

" 'But we, when moved by deep feeling, evaporate; we breathe ourselves out and away,' wrote Rilke in his Second Elegy. In making art, the artist expires, breathing themselves out to allow the inspiring to happen, the breathing in of the glinting universal air, intelligent with many minds, electric and on the loose. Artist, shapeshifter, shaman or poet, all are lovers of metamorphosis, all are minded to vision, insight and dream.

"Self-appointed shamanism can reek of cultural appropriation, but even in cultures that have temporarily misplaced their shamanism, the role survives, donning a deep disguise. Joseph Campbell and others believed that artists have taken up the role, and it seems to me that this is true for a particular reason, that both art and shamanism use the realm of metaphor, where emotion is expressed and healing happens. With the metaphoric vision, empathy flows, knowing no borders. Both artist and shaman create harmony within an individual and between the individual and the wider environment, a way of thinking essential for life; poetry works 'to renew life, to renew the poet's own life, and, by implication, renew the life of the people,' wrote Ted Hughes. But ours is an age of lethal literalism which viciously attacks metaphoric insight and all its value...."

Later in the essay she returns to the subject of metaphor:

"If I were asked what is the greatest human gift, I would say it is metaphor. A little boat of metaphor chugs across the seas, carrying a cargo of meaning across the oceans that divide us. Metaphor is how we relate to each other and how our one species attempts to comprehend others. With this gift, humans listen and speak more intensely and the meanings of all things -- ocean or forest, snail or chaffinch -- grow outwards in concentric rings of concentrated word-poems. 'Each word was once a poem,' said Emerson, and 'language is fossil poetry.' So a tulip, for example, ultimately derives from the Turkish word for 'turban.'

"Metaphor works with the legerdemain of the psyche, the lightest of touched to shift the mindscape, transforming one thing into another, leading to new ways of seeing. Metaphor follows Emily Dickinson's injunction to 'tell the truth but tell it slant,' so, slantwise by Saturn-mind running rings around literalism, metaphor is canted incantation, it breathes fact into life, it enchants. And metaphor is the language of the shaman and the artist."

(You can read the full essay online here.)

In subsequent essays, Griffiths turns her gaze on animals, insects, the soil below and the sky above ... on the toxic ideas and forces that threaten them ... and on those courageous souls rebelling on their behalf.

Why Rebel is wise, and fierce, and heart-breaking, and well worth reading. It's good medicine.

Words: The passages above are from Why Rebel by Jay Griffiths (Penguin/Random House, 2021). The poem in the picture captions is from The Woman Who Fell from the Sky by Joy Harjo (WW Norton, 1996). All rights reserved by the authors. Pictures: Morning coffee break down by the leat. The little drawing is by John D. Batten, a fairy tale illustrator from Plymouth, Devon (1860-1932).

Posts discussing Jay Griffiths' previous books & essays include Finding the Way to the Green, The Enclosure of Childhood, Kissing the Lion's Nose, To the Rebel Soul in Everyone, Daily Grace, and Once upon a time.

June 2, 2021

Recommended reading: on fairy tales

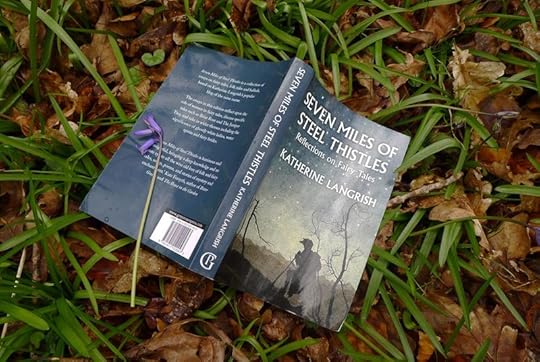

Following on from yesterday's post, for those who would like to read about fairy tales (in addition to literary re-tellings) I highly recommend Seven Miles of Steel Thistles: Reflections on Fairy Tales by Katherine Langrish.

Now while I might seem biased because Katherine is a family friend, in truth I am sharply opinionated when it comes to books about folklore and fairy tales; I was mentored in the field by Jane Yolen, after all, which sets the bar pretty darn high. Thus it is no small praise to say that Seven Miles of Steel Thistles is an essential book for practitioners of mythic arts: insightful, reliable, packed with information...and thoroughly enchanting.

In the book's introduction Katherine writes:

In the book's introduction Katherine writes:

"As a child I was usually deep in a book, and as often as not, it would be full of fairy tales or myths and legends from around the world. I remember choosing the Norse myths for a school project, retelling and illustrating stories about Thor, Odin and Loki. I read the tales of King Arthur, I read stories from the Arabian Knights. And gradually, I hardly know how, I became aware that grown-ups made distinctions between these, to me, very similar genres. Some were taken more seriously than others. Myths -- especially the 'Greek myths' -- were top of the list and legends came second, while fairy tales were the poor cousins at the bottom. Yet there appeared to be a considerable overlap. Andrew Lang included the story of Perseus and Andromeda in The Blue Fairy Book, under the title 'The Terrible Head.' And surely he was right. It is a fairy story, about a prince who rescues a princess from a monster....

"The field of fairy stories, legends, folk tales and myths is like a great, wild meadow. The flowers and grasses seed everywhere; boundaries are impossible to maintain. Wheat grows into the hedge from the cultivated fields nearby, and poppies spring up in the middle of the oats. A story can be both things at once, a 'Greek myth' and a fairytale too: but if we're going to talk about them, broad distinctions can still be made and may still be useful.

"Here is what I think: a myth seeks to make emotional sense of the world and our place in it. Thus, the story of Persephone's abduction by Hades is a religious and poetic exploration of winter and summer, death and rebirth. A legend recounts the deeds of heroes, such as Achilles, Arthur, or C�� Chulainn. A folk tale is a humbler, more local affair. Its protagonists may be well-known neighborhood characters or they may be anonymous, but specific places become important. Folk narratives occur in real, named landscapes. Green fairy children are found near the village of Woolpit in Suffolk. A Cheshire farmer going to market to sell a white mare meets a wizard, not just anywhere, but on Alderley Ledge between Mobberley and Macclesfield. In Dorset, an ex-soldier called John Lawrence sees a phantom army marching 'from the direction of Flowers Barrow, over Grange Hill, and making for Wareham.' Local hills, lakes, stones and even churches are explained as the work of giants, trolls or the Devil.

"Here is what I think: a myth seeks to make emotional sense of the world and our place in it. Thus, the story of Persephone's abduction by Hades is a religious and poetic exploration of winter and summer, death and rebirth. A legend recounts the deeds of heroes, such as Achilles, Arthur, or C�� Chulainn. A folk tale is a humbler, more local affair. Its protagonists may be well-known neighborhood characters or they may be anonymous, but specific places become important. Folk narratives occur in real, named landscapes. Green fairy children are found near the village of Woolpit in Suffolk. A Cheshire farmer going to market to sell a white mare meets a wizard, not just anywhere, but on Alderley Ledge between Mobberley and Macclesfield. In Dorset, an ex-soldier called John Lawrence sees a phantom army marching 'from the direction of Flowers Barrow, over Grange Hill, and making for Wareham.' Local hills, lakes, stones and even churches are explained as the work of giants, trolls or the Devil.

"Fairy tales can be divided into literary fairy tales, the more-or-less original work of authors such as Hans Christian Andersen, George MacDonald and Oscar Wilde (which will not concern me very much in this book), and anonymous traditional tales originally handed down the generations by word of mouth but nowadays usually mediated to us via print. Unlike folk tales, traditional fairy tales are usually set 'far away and long ago' and lack temporal and spatial reference points. They begin like this: 'In olden times, when wishing still helped one, there lived a king...' or else, 'A long time ago there was a king who was famed for his wisdom throughout the land...' A hero goes traveling, and 'after he had traveled some days, he came one night to a Giant's house...' We are everywhere or nowhere, never somewhere. A fairy tale is universal, not local."

Katherine concludes the book's introduction with the reminder that fairy tales, found all around the world, are amazingly diverse and amazingly hardy. "They've been told and retold, loved and laughed at, by generation after generation because they are of the people, by the people, for the people. The world of fairy tales is one in which the pain and deprivation, bad luck and hard work of ordinary folk can be alleviated by a chance meeting, by luck, by courtesy, courage and quick wits -- and by the occasional miracle. The world of fairy tales is not so very different from ours. It is ours."

It is indeed.

There are seven miles of hill on fire for you to cross, and there are seven miles of steel thistles, and seven miles of sea, says the narrator of an old Irish fairy tale.

With this delightful collection of essays as a guide, the journey is worth every step.

The passages by Katherine Langrish in the post above and in the picture captions are from Seven Miles of Steel Thistles (The Greystones Press, 2016); all rights reserved by the author. You can read Katherine's musings on folklore on her blog, also called Seven Miles of Steel Thistles; and learn more about her other books, stories, and essays here.

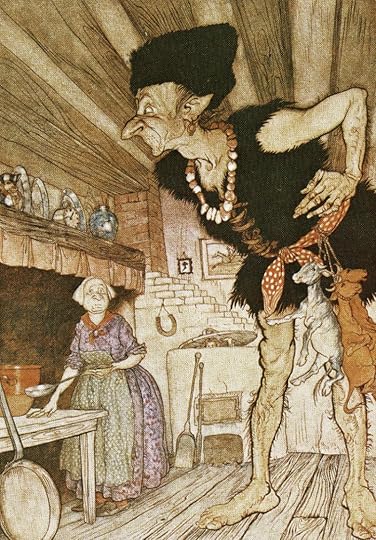

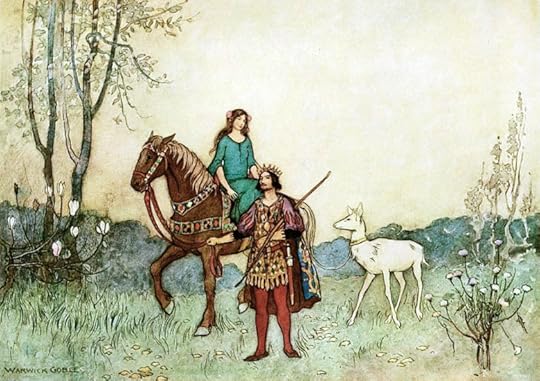

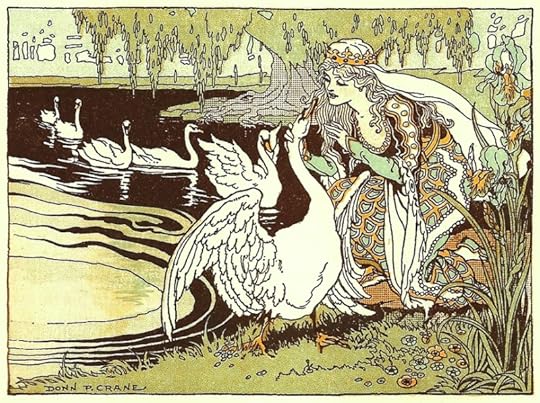

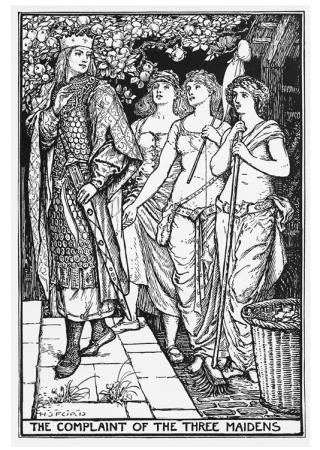

The text of this post was written when Katherine's book was published in 2016, but the illustrations are new today: eight marvellous pictures from the Golden Age of Illustration. From top to bottom they are: The Wind's Tale by Edmund Dulac (1882-1953), Little Red Riding Hood by Margaret Ely Webb (1874-1965), Beauty & the Beast by Walter Crane (1843-1915), The Complaint of the Three Maidens by H.J. Ford (1860-1941), Jack the Giant-Killer by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939), Hans Christian Andersen's The Real Princess by William Heath Robinson (1872-1944), Brother & Sister by Warwick Goble (1864-1943), East of the Sun West of the Moon by Kay Nielsen (1886-1957).

June 1, 2021

Recommended reading: adult fairy tales

Fairy tales, in previous centuries, weren't considered stories for children only. The name "fairy tale" comes from the French conte de f��e, a term coined in 17th century Paris for a literary fashion popular with adult readers. At the heart of the 17th century's profusion of literary fairy tales are the remnants of much older tales from the oral tradition -- mixed with literary influences from medieval romance, and from 16th century Italian publications. French writers from the salons of Paris -- such as Madame D'Aulnoy, Marie-Jeanne L���H�����ritier, Comtesse de Murat, and Charles Perrault -- created complex, enchanting tales still known and enjoyed by readers today (though often in simplified forms) : Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty, Bluebeard, The White Cat, The Discrete Princess, Bearskin, and numerous others. A second wave of French writers added to the genre in the 18th century, including Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve, the original author of Beauty and the Beast.

German writers (especially the Germantics Romantics) took up the literary fairy tale form in the 18th and 19th centuries, creating adult works inspired by previous French and Italian stories mixed with tales from the German folk tradition -- as popularized by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm and their prolific circle of writers and scholars. Also in the 19th century, Denmark's celebrated Hans Christian Anderson created such beloved fairy tales as The Little Mermaid and The Snow Queen; and England's Oscar Wilde penned poignant stories such as The Selfish Giant and The Nightingale and the Rose. By this time, however, fairy tales had become increasingly associated with children. The older, darker stories were cleaned up by Victorian editors and published in the prosperous new market for children's books.

This bowdlerization of fairy tales continued in the 20th century, epitomized by the simple cartoon versions created by Walt Disney. Alas, these simple versions of the tales are the only ones most readers know today -- versions in which the complexity, sensuality, and horror have been carefully toned down, or stripped out altogether. Where once we had stories of active heroines making their own way through the dark of the woods, now we have girls who sit crying in the ashes, awaiting rescue by a rich Prince Charming. Where once Sleeping Beauty was impregnated by her prince, waking all alone at the birth of twins, now she's awakened by a chaste kiss and the tale ends promptly with a wedding.

Despite the pervasive Disney influence, at the end of the 20th century a revival of adult fairy tale literature began (primarily) among three overlapping groups of authors: feminist "mainstream" writers, feminist poets, and writers of fantasy literature. Foremost among them is Angela Carter, whose brilliant re-working of fairy tales, The Bloody Chamber (1979), influenced a generation of writers and did more than other single text to bring fairy tales back into vogue with adult readers.

Four decades later, the revival is still going strong, with many fine authors working with fairy tale themes. The story collections pictured below are by two of the very best of them, Theodora Goss and Veronica Schanoes -- both of whom, it should be noted, are fairy tale scholars as well as excellent writers of fiction.

If Angela Carter were alive today, I have no doubt she'd love Snow White Learns Witchcraft and Burnings Girls as much as I do. Please don't miss these marvelous books.

If you'd like more recommendations of fairy-tale-inspired novels and stories, you'll find them here.

Snow White Learns Witchcraft: Stories & Poems by Theodora Goss was published by Mythic Delirium Books, 2019, and won the 2020 Mythopoeic Award. The Burning Girls & Other Stories by Veronica Schanoes was published by Tor Books this year. Both volumes contain introductions by Jane Yolen, a fairy tale master herself.

The illustrations above are by Angela Barrett, from her beautiful editions of Snow White and Beauty and the Beast. All rights reserved by the artist.

May 29, 2021

Myth & Moor update

It's another three-day holiday weekend here in the UK, and the Bumblehill Studio will be closed through Monday. Myth & Moor will resume on Tuesday, June 1st.

I hope the last days of "the pleasant month of May" are enchanting for you all.

Music above: "The Pleasant Month of May," a traditional song performed by Jackie Oates, from her third album, Hyperboreans (2009).

May 28, 2021

Stories are medicine

For the last two weeks we've been discussing the folklore of spring wildflowers -- including the ways these plants have long been used by healers, herbalists, and hedgewitches to ease or heal afflictions of the body, mind, and spirit. In traditional oral cultures, folk wisdom of this sort was often passed down through stories, rhymes, proverbs, or other mnemonic devices; and in a number of these cultures, the stories themselves were a form of medicine, as necessary to the healing process as any plant-based salve, poultice, brew, or potion.

There has long been a mythic link between storytelling and the healing arts -- so much so that in ancient societies found world-wide storytellers and healers were one and the same. Stories were valued not only for entertainment but also as a means to ensure or restore good health (both physical and mental), and to help overcome ordeals of calamity, grief, or trauma.

There has long been a mythic link between storytelling and the healing arts -- so much so that in ancient societies found world-wide storytellers and healers were one and the same. Stories were valued not only for entertainment but also as a means to ensure or restore good health (both physical and mental), and to help overcome ordeals of calamity, grief, or trauma.

In some shamanic traditions, magical tales are told in a ritual manner to facilitate specific acts of healing. In Korea, for example, a well-known fairy tale called "Shimchong, the Blind Man's Daughter," a variant of Beauty and the Beast, plays a role in traditional healing rites related to eyesight. "The 'patient' is supposed to be healed precisely at the climax of the story," explains Korean-American folklorist Heinz Insu Fenkl, "when Old Man Shim opens his eyes and sees his long-lost daughter."

In Women Who Run With the Wolves, psychologist and folklorist Clarissa Pinkola Est��s writes of the healing powers of Hispanic "trance-tellers" who enter into a trance state "between worlds" in order to "attract" a story to them. Such stories are said to contain the mythic information the listeners most need to hear. "The trance-teller calls on El Duende," says Est��s, "the wind that blows soul into the faces of listeners. A trance-teller learns to be psychically double-jointed through the meditative practice of story, that is, training oneself to undo certain psychic gates and ego apertures in order to let the voice speak, the voice that is older than the stones. When this is done, the story may take any trail....The teller never knows how it will all come out, and that is at least half of the moist magic of the story."

Storytelling also plays an important role in the shamanic practices of Siberia -- where, as in Korea, it is often women who perform the traditional healing rites. "Oral storytelling is the way shamans themselves convey spiritual truths," writes Kira Van Duesen in The Flying Tiger: Women Shamans and Storytellers of the Amur. "Through the power of words and sounds, stories and songs act directly on the listener to bring about healing and spiritual growth. More important than the content of the tales is the process of telling them -- the way a storyteller chooses the tale, the details added or removed, the tone -- all these make storytelling a spiritual act. Stories and songs are not objects or artifacts but living beings."

In many Native American cultures illness indicates that the patient's life, spirit, or relationships have gone out of balance and harmony; a restoration of spiritual balance is required before a physical illness can be cured. Among the Din�� (Navajo), in the high desert of northern Arizona and New Mexico, health and longevity are attained by "walking in beauty," living in harmony within oneself and with the natural world. If this harmony is lost, it can be restored through elaborate, days-long ceremonies during which some of the most ancient, sacred stories of the tribe are chanted and painted in sand. In the traditional lore of the Tohono O'Odham, whose low desert homeland stretches across the Arizona/Mexico border, disease is caused by improper relationships with the bird and animal worlds. The repetition of certain stories and songs brings these relationships back into harmony and the sufferer back to health.

"A people are as healthy and confident as the stories they tell themselves," says British-Nigerian novelist and essayist Ben Okri. "Sick storytellers can make nations sick. Without stories we would go mad. Life would lose it���s moorings or orientation. Even in silence we are living our stories."

Stories are central to the healing practices of the traditional Gaelic culture of Scotland -- of which the leading characteristics, writes Noragh Jones (in Power of Raven, Wisdom of Serpent), "are an instinctive ability to gather healing plants from their own locality when they are sick; a heritage of herbal remedies handed on from mother to daughter which have been tried and tested in everyday situations -- part of the informal education of the household; a sense that illness is some kind of imbalance in the individual, and so mind and body and spirit must be treated as a whole; and a conviction that healing is a spiritual resource as well as a physical process."

Herbalists and hedgewitches of the British Isles once used stories not only as a means to preserve information about the medicinal properties of plants, but also as a method of communication with the spirits of the plants themselves. In trance states induced by ritual fasting, prayer, or the use of hallucinogenic mushrooms, they communed with the plants in order to learn the best ways to gather, preserve, and use them. Likewise, the stories told by Siberian shamans weren't always meant for human ears but for the various plant, animal, and supernatural spirits who aided in their rites of healing.

The medicine men and women of the various indigenous tribes living in the Amazon have long been renown for their deep knowledge of the healing properties of plants, sometimes gained during trances induced by hallucinogenics such as ayahuaska. A relationship must be established between the healer and the plant in question, however. In Plant Spirit Medicine, Eliot Cowan tells the tale of an American friend in the Amazon. The man meets a hunter-shaman who takes him on a long walk through the jungle, pointing out plants and listing the various ways he has used them to heal. The American wants to write this all down, which makes the shaman howl with laughter. No, no, he explains, "that was just to introduce you to some of the plants. If you actually want to use a plant yourself, the spirit of the plant must come to you in dreams. If the spirit tells you how to prepare it and what it will cure, you can use it. Otherwise it won���t work for you."

"There is a plant for everything in the world; all you have to do is find it," an old herb-woman in the Louisiana Bayou told folklorist Ruth Bass in 1920s. And there's a folk story attached to nearly every plant -- as volumes of folklore and herb lore from all around the world can attest. The history of modern medicine is rooted in the history of folk medicine, entwined with myths, folk tales, fairy tales, and the homespun magics of countryside healers.

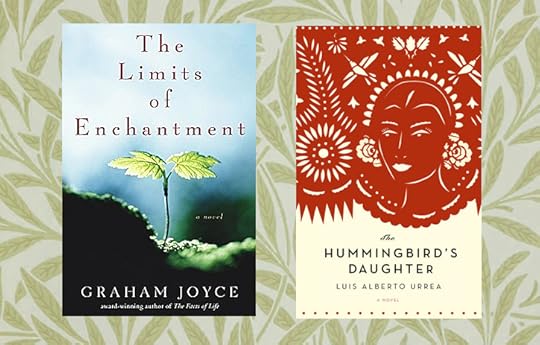

Two excellent novels exploring the connections between folk medicine, myth, spirituality, and the mysteries of the natural world are The Limits of Enchantment by the late Graham Joyce, and The Hummingbird���s Daughter by Luis Alberto Urrea.

The first of these, The Limits of Enchantment, set in the deep green hills of the English countryside in 1966, is a story about a hedgerow healer and midwife, the apprenticeship of her adopted daughter, and their struggle to maintain an ancient way of life in the modern world. The Hummingbird's Daughter, by contrast, is set in the dusty brown hills of northern M��xico in the years before the Mexican Revolution. The novel is based on the real-life story of the author's great-Aunt Teresita, the illegitimate child of a prosperous rancher and a Yaqui Indian girl. Apprenticed to an Indian medicine woman, Teresita demonstrated such miraculous healing powers that her fame spread through northern M��xico, leading to denunciation by the Catholic church and accusations of fomenting an Indian uprising. Both of these novels are coming-of-age stories about young women with remarkable gifts, looking at the ways that indigenous healing traditions are passed through the generations -- and how such gifts are both feared and revered in a world uncomfortable with Mystery.

In a number of Native American traditions, the word "medicine" does not refer to the pills or tonics we take to cure an illness but to anything that has spiritual power, and that helps to keep us "walking in beauty."

Words can be strong medicine. Stories can touch our hearts and souls; they can point the way to healing and transformation. Our own lives are stories that we write from day to day; they are journeys through the dark of the fairy tale woods. The tales of previous travellers through the woods are passed down to us in the poetic, symbolic language of folklore and myth; where we step, someone has stepped before, and their stories can help light the way.

The articles and books cited in this post are: "Simchong, The Blindman's Daughter" and "Storytelling and Healing" by Heinz Insu Fenkl (The Journal of Mythic Arts), Women Who Run With the Wolves: Myths & Stories of the Wild Woman Archetype by Clarissa Pinkola Est��s (Ballentine, 1992), The Flying Tiger: Women Shamans and Storytellers of the Amur by Kira Van Deusen (McGill-Queen's University Press, 2001), Birds of Heaven: Two Essays by Ben Okri (Phoenix, 1996), Power of Raven, Wisdom of Serpent: Celtic Women's Spirituality by Noragh Jones (Floris Books, 1994), Plant Spirit Medicine: A Journey Into the Wisdom of Plants by Eliot Cowan (Granite Publishing, 1996), "Fern Seed - For Peace" by Ruth Bass (Folk-Say: A Regional Miscellany, edited by BA Botkin, U of Oklahoma Press, 1931), The Limits of Enchantment by Graham Joyce (Gollancz, 2005), and The Hummingbird's Daughter by Luis Alberto Urrea (Little Brown, 2005). The poem in the picture captions is from Poetry (March 2021). All rights to the text above reserved by the authors. The ink drawing above is by Helen Stratton (1867-1961).

For a good book of folk stories associated with plants, I highly recommend Botanical Folk Tales of Britain & Ireland by my friend and neighbour Lisa Schneidau. Her latest book, Woodland Folk Tales of Britain & Ireland, is also a treat.

May 26, 2021

The bluebell path

Today, for this sequence of wildflower posts, I'm following Tilly on a bluebell path...which in folklore (as we discussed earlier) is a dangerous thing to do. The bluepath path is the way into Faerie, and doesn't always lead home again.

Like most of the season's wildflowers, bluebells are an ephemeral pleasure, here today and gone tomorrow. If I want to enjoy them fully then I must take the time to be outdoors right now, not wait until the day's chores are finished and studio goals are met. As a working artist tied to schedules and deadlines, my mind often dwelling in the past or the future, the brevity of the bluebell season pulls me back into the immediate present: to this fragrant blue-tinted hillside experienced with all of my senses.

Like every writer, I'm often asked where I find inspiration for my work. There's no single answer to the question, of course, for all kinds of things go into each author's creative mix: our personal histories, experiences, interests, and obsessions, along with the influence of other artists and other works of art. But for me, most of all, inspiration comes from the land: from the folklore-steeped Devon countryside, from the myth-haunted deserts of the American south-west, from the paths I've walked over and over again, creating relationships with the local flora and fauna, and learning their traditional stories.

Ursula K. Le Guin has this to say on the subject of inspiration:

"It's a big question -- where do writers get their ideas, where do artists get their visions, where do musicians get their music? It's bound to have a big answer. Or a whole lot of them. One of my favorite answers is this: Somebody asked Willie Nelson how he thought up his tunes, and he said, 'The air is full of tunes, I just reach up and pick one.'

"For a fiction writer -- a storyteller -- the world is full of stories, and when story is there, it's there; you just reach up and pick it.

"Then you have to be able to tell it to yourself.

"First you have to be able to wait. To wait in silence. Listen for the tune, the vision, the story. Not grabbing, not pushing, just waiting, listening, being ready for it when it comes. This is an act of trust. Trust in yourself, trust in the world. The artist says, 'The world will give me what I need and I will be able to use it rightly.'

"Readiness -- not grabbiness, not greed -- readiness: willingness to hear, to listen carefully, to see clearly and accurately -- to let the words be right. Not almost right. Right. To know how to make something out of the vision; that's what practice is for. Because being ready doesn't mean just sitting around, even if it looks like that's what most writers do; artists practice their art continually, and writing happens to involve a lot of sitting. Scales and finger exercises, pencil sketches, endless unfinished and rejected stories. The artist who practices knows the difference between practice and performance, and the essential connection between them. The gift of those seemingly wasted hours and years is patience andf readiness; a good ear, a keen eye, a skilled hand, a rich vocabulary and grammar. The gift of practice to the artist is mastery, or a word I like better, 'craft.'

"With those tools, those instruments, with that hard-earned mastery, that craftiness, you do your best to let the 'idea' -- the tune, the vision, the story -- come through clear and undistorted. Clear of ineptitude, awkwardness, amateurishness; undistorted by convention, fashion, opinion.

"This is a very radical job, dealing with the ideas you get if you are an artist and take your job seriously, this shaping a vision into the medium of words. It's what I like to do best in the world, and what I like to talk about when I talk about writing. I could happily go on and on about it. But I'm trying to talk about where the vision, the stuff you work on, the 'idea,' comes from, so:

"The air is full of tunes. A piece of rock is full of statues. The earth is full of visions. The world is full of stories.

"As an artist, you trust that."

The world is, indeed, full of stories upon stories...but sometimes I find that the quiet tales of the land, and my owner inner voice, are drowned out by the roar of the stories pressing in from the world outside: the urgent stories of politics, pandemics, economics, ecological crisis, all of them important, all of them overwhelming. On those days when "the world is too much with us," I lace on my boots, head for the hills, and let the roar diminish behind me. We need the quieter stories too...or, at least, I know that I need them. So I follow my dog on the bluebell path, and a different world is restored to me. Call it nature, call it Faerie, call it the place where poems and tales pluck at my sleeve saying: Tell me next. Tilly and I vanish into the blue....

And somehow we always find our way home.

Words: The passage above is from "Where Do You Get Your Ideas From?" by Ursula K. Le Guin, a talk for the Portland Arts & Lectures series, October, 2000, published in The World Spit Open (Tin House Books, 2014). Pictures: Walking the bluebell path.

The folklore of foxgloves

In the edge of the fields and along woodland trails, I see the green leaves of foxgloves begin to unfurl, but it will be some weeks yet before they grow tall and grace the hills with their spires of blooms.

Folklorists are divided on where the common name for Digitalis purpurea comes from. In some areas of the British Isles it's believed be a corruption of "folksglove," associating the flowers with the fairy folk, while in others the plant is also known as "fox fingers," its blossoms used as gloves by the foxes to keep dew off their paws. Another theory suggests that the name comes from the Anglo-Saxon word foxes-gleow, a "gleow" being a ring of bells. This is connected to Norse legends in which foxes wear the bell-shaped foxglove blossoms around their necks; the ringing of bells was a spell of protection against hunters and hounds.

Foxgloves give us digitalin, a glysoside used to treat heart disease, and this powerful plant has been used for heart tonics since Celtic and Roman times. Botanist Bobby J. Ward gives us this account of early foxglove use in his excellent book A Contemplation Upon Flowers:

"An old Welsh legend claims to be the first to proscribe it, because the knowledge of its properties came to the meddygon, the Welsh physicians, in a magical way. The legend is loosely based on the early 13th century historical figure Rhiwallon, the physician to  Prince Rhys the Hoarse, of South Wales. Young Rhiwallon was walking beside a lake one evening when from the mist rose a golden boat. A beautiful maiden was rowing the boat with golden oars. She glided softly away in the mist before he could speak to her. Rhiwallon returned every evening looking for the maiden; when he did not find her, he asked advice from a wise man. He told Rhiwallon to offer her cheese. Rhiwallon did as he was told, the maiden appeared and took his offering. She came ashore, became his wife, and bore him three sons.

Prince Rhys the Hoarse, of South Wales. Young Rhiwallon was walking beside a lake one evening when from the mist rose a golden boat. A beautiful maiden was rowing the boat with golden oars. She glided softly away in the mist before he could speak to her. Rhiwallon returned every evening looking for the maiden; when he did not find her, he asked advice from a wise man. He told Rhiwallon to offer her cheese. Rhiwallon did as he was told, the maiden appeared and took his offering. She came ashore, became his wife, and bore him three sons.

"After the sons grew and the youngest became a man, Rhiwallon's wife rowed into the lake one day and returned with a magic box hinged with jewels. She told Rhiwallon he must strike her three times so that she could return to the mist forever. He refused to hit her, but the next morning as he finished breakfast and prepared to go to work, Rhiwallon tapped his wife affectionately on the shoulder three times. Instantly a cloud of mist enveloped her and she disappeared. Left behind was the bejeweled magic box. When the three sons opened it, they found a list of all the medicinal herbs, including foxglove, with full directions for their use and healing properties. With this knowledge the sons became the most famous of physicians."

Foxglove is a plant beloved by the fairies, and its appearance in the wild indicates their presence. Likewise, fairies can be attracted to a dometic garden by planting foxgloves. Dew collected from the blossoms is used in spells for communicating with fairies, though gloves must be worn when handling the plant as digitalis can be toxic.

In the Scottish borders, foxgloves leaves were strewn about babies' cradles for protection from bewitchement, while in Shropshire they were put in children's shoes for the same reason (and also as a cure for Scarlet Fever). Picking foxglove flowers is said to be unlucky. Here in Devon and Cornwall, this is because it robs the fairies, elves, and piskies of a plant they particularly delight in; in the north of England, foxglove flowers in the house are said to allow the Devil entrance.

In the Scottish borders, foxgloves leaves were strewn about babies' cradles for protection from bewitchement, while in Shropshire they were put in children's shoes for the same reason (and also as a cure for Scarlet Fever). Picking foxglove flowers is said to be unlucky. Here in Devon and Cornwall, this is because it robs the fairies, elves, and piskies of a plant they particularly delight in; in the north of England, foxglove flowers in the house are said to allow the Devil entrance.

In Roman times, foxglove was a flower sacred to the goddess Flora, who touched Hera on her breasts and belly with foxglove in order to impregnate her with the god Mars. The plant has been associated with midwifery and women's magic ever since -- as well as with "white witches" (practitioners of benign and healing magic) who live in the wild with vixen familiars, the latter marked by bells made of foxglove blossoms tied around their necks. In medieval gardens, the plant was believed to be sacred to the Virgin Mary. In the earliest recordings of the Language of Flowers, foxgloves symbolized riddles, conundrums, and secrets, but by the Victorian era they had devolved into the more negative symbol of insincerity.

A lovely old legend told here in the West Country explains why foxgloves bob and sway even when there is no wind: this is the plant bowing to the fairy folk as they pass by. Wherever foxgloves grow in abundance you can be sure it's a place where the fey are present, for these flowers thrive in a loam of old stories, riddles, secrets, and Otherworldly enchantment.

The foxes themselves pad through folklore and myth as mischievous Tricksters in various forms: both clever and foolish, creative and destructive, perfectly civilized and utterly wild. Fox Tricksters appear in the popular tales of many cultures around the world, including Aesop's Fables from ancient Greece, the "Reynard" stories of medieval Europe, the "Giovannuzza" tales of Italy, the "Brer Fox" lore of the American South, and the diverse indigenous stories of North and South America. At the darker end of the fox-lore spectrum, however, we find creatures of a distinctly more dangerous cast: Reynardine, Mr. Fox, kitsune (the Japanese fox wife), kumiho (the Korean nine-tailed fox), and other treacherous shape-shifters.

Fox women appear in many story traditions but they're particularly prevalent across the Far East. Fox wives, writes folklorist Heinz Insu Fenkle (in a good article on the subject) are seductive creatures who "entice unwary scholars and travelers with the lure of their sexuality and the illusion of their beauty and riches. They drain the men of their yang -- their masculine force -- and leave them dissipated or dead (much in the same way La Belle Dame Sans Merci in Keats's poem leaves her parade of hapless male victims).

Fox women appear in many story traditions but they're particularly prevalent across the Far East. Fox wives, writes folklorist Heinz Insu Fenkle (in a good article on the subject) are seductive creatures who "entice unwary scholars and travelers with the lure of their sexuality and the illusion of their beauty and riches. They drain the men of their yang -- their masculine force -- and leave them dissipated or dead (much in the same way La Belle Dame Sans Merci in Keats's poem leaves her parade of hapless male victims).

"Korean fox lore, which comes from China (from sources probably originating in India and overlapping with Sumerian lamia lore) is actually quite simple compared to the complex body of fox culture that evolved in Japan. The Japanese fox, or kitsune, probably due to its resonance with the indigenous Shinto religion, is remarkably sophisticated. Whereas the arcane aspects of fox lore are only known to specialists in other East Asian countries, the Japanese kitsune lore is more commonly accessible. Tabloid media in Tokyo recently identified the negative influence of kitsune possession among members of the Aum Shinregyo (the cult responsible for the sarin attacks in the Tokyo subway). Popular media often report stories of young women possessed by demonic kitsune, and once in a while, in the more rural areas, one will run across positive reports of the kitsune associated with the rice god, Inari."

The "nine-tailed fox" of China and Japan is often (but not always) a demonic spirit, malevolent in intent. It takes possession of human bodies, both male and female, moving for one victim to another over thousands of years, seducing other men and women in order to dine on their hearts and livers. Human organs are also a delicacy for the nine-tailed fox, or kumiho, of Korean lore -- although the earliest texts don't present the kumiho as evil so much as amoral and unpredictable...occasionally even benevolent...much like the faeries of English folklore.

There are fox lovers and wives in the Western tradition, but their tales are less well known; and they tend, by and large, to be better disposed to the men that they take to their beds. Marriage to a fox is challenging at best, for they are not mortal, they are creatures of the wild: mysterious, independent, and not to be tamed nor taken for granted. (My favourite fox woman story of this sort is retold by Dartmoor mythographer Martin Shaw in his brilliant book Scatterlings. )

There are fox lovers and wives in the Western tradition, but their tales are less well known; and they tend, by and large, to be better disposed to the men that they take to their beds. Marriage to a fox is challenging at best, for they are not mortal, they are creatures of the wild: mysterious, independent, and not to be tamed nor taken for granted. (My favourite fox woman story of this sort is retold by Dartmoor mythographer Martin Shaw in his brilliant book Scatterlings. )

In the West, it's the fox men we need to be wary of -- such as Reynardine (in the old folk ballad of that name), a glib and handsome were-fox who lures young maidens to a bloody death. The title character of the fairy tale Mr. Fox, is cousin to the kumiho and Reynardine, with a bit of Bluebeard mixed in for good measure: he promises marriage to a gentlewoman while his lair is littered with her predecessors' bones. Neil Gaiman draws inspiration from the tale in his wry, wicked poem "The White Road" -- while Jeannine Hall Gailey, by contast, takes a more sympathetic view of shape-shifting foxes in "The Fox-Wife's Invitation," written from a kitsune's point of view.

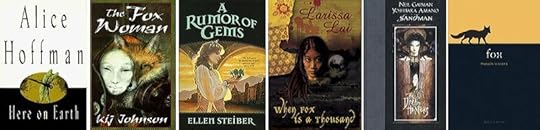

There are a number of good novels that draw upon fox legends -- foremost among them, Kij Johnson's exquisite The Fox Woman, which no mythic fiction reader should miss. I also recommend Neil Gaiman's The Dream Hunters (with the Japanese artist Yoshitaka Amano); Larissa Lai's When Fox Is a Thousand; and Ellen Steiber's gorgeous A Rumor of Gems (as well as her heart-breaking novella "The Fox Wife," published in Ruby Slippers, Golden Tears). Alice Hoffman's disquieting Here on Earth is a contemporary take on the Reynardine/Mr. Fox theme, as is Helen Oyeyemi's Mr. Fox, a complex work full of stories within stories within stories. For younger readers, try the "Legend of Little Fur" series by Isobelle Carmody. And for mythic poetry, I especially recommend She Returns to the Floating World by Jeannine Hall Gailey and Sister Fox���s Field Guide to the Writing Life by Jane Yolen. (More fox tales are listed here.)

For the fox in myth, legend, and lore, try: Fox by Martin Wallen; Reynard the Fox, edited by Kenneth Varty; Kitsune: Japan's Fox of Mystery, Romance, and Humour by Kiyoshi Nozaki; Alien Kind: Foxes and Late Imperial Chinese Narrative by Raina Huntington; The Discourse on Foxes and Ghosts: Ji Yun and Eighteenth-Century Literati Storytelling by Leo Tak-hung Chan; The Fox and the Jewel: Shared and Private Meanings in Contemporary Japanese Inari Worship, by Karen Smythers; and an interesting post on the fox in folklore, literature and art by artist David Hollington.

Although chancy to encounter in myth, and too wild to domesticate easily (in stories and in life), some of us long for foxes nonetheless: for their musky scent, their hot breath, their sharp-toothed magic. "I needed fox," wrote Adrienne Rich:

Badly I needed

a vixen for the long time none had come near me

I needed recognition from a

triangulated face burnt-yellow eyes

fronting the long body the fierce and sacrificial tail

I needed history of fox briars of legend it was said she had run through

I was in want of fox

And the truth of briars she had to have run through

I craved to feel on her pelt if my hands could even slide

past or her body slide between them sharp truth distressing surfaces of fur

lacerated skin calling legend to account

a vixen's courage in vixen terms

Now go softly. Go gently. Go warily. Soon the tall spires of foxgloves will bloom, and then you will know that the Good Folk are near. Look for their gloves discarded on the path. Listen for the sound of foxglove bells. Breathe in the sharp scent of the wild...and go home, changed.

You will dream of foxes.

Art: Pages from The Country Diary of an Edwardian Lady by Edith Holden (1871-1920), "Foxglove Fairy" by Cicely Mary Barker (1875-1973), "Foxglove" by botanical artist Christie Newman, a page from Flora Londinensis by English apothecary & botanist William Curtis (1746-1799), "Foxgloves" by Kelly Louise Judd, "Fox Woman" by Susan Seddon Boulet (1941-1997), "Fox Nest" by Flora McLachlan, "The Princess and the Fox" by H.J. Ford (1860-1941), "The Fox and Ivy" by Jessica Roux, "Crossing an Iced-Over Stream" by Gina Litherland, "The Winter Guest" by David Hollington, a small illustration by Julianna Swaney, "Little Evie in the Wild Wood" by Catherine Hyde, The beautiful fox photographs are by by wildlife photographer Richard Bowler. All rights reserved by the artists.

Words: The Bobby J. Ward passage quotes above is from A Contemplation on Flowers: Garden Plants in Myth & Literature (Timber Press, 2009). All rights reserved by the author. This sequence of wildflower posts is drawn from the Myth & Moor archives (due to current time constraints due to family life). New posts will resume on Tuesday, June 1st.

May 24, 2021

The folklore of nettles

In the fairy tale of "The Wild Swans" by Hans Christian Andersen, the heroine's brothers have been turned into swans by their evil stepmother. A kindly fairy instructs her to gather nettles in a  graveyard by night, spin their fibers into a prickly green yarn, and then knit the yarn into a coat for each swan brother in order to break the spell -- all of which she must do without speaking a word or her brothers will die. The nettles sting and blister her hands, but she plucks and cards, spins and knits, until the nettle coats are almost done -- running out of time before she can finish the sleeve on the very last coat. She flings the coats onto her swan-brothers and they transform back into young men -- except for the youngest, with the incomplete coat, who is left with a wing in the place of one arm. (And there begins a whole other tale.)

graveyard by night, spin their fibers into a prickly green yarn, and then knit the yarn into a coat for each swan brother in order to break the spell -- all of which she must do without speaking a word or her brothers will die. The nettles sting and blister her hands, but she plucks and cards, spins and knits, until the nettle coats are almost done -- running out of time before she can finish the sleeve on the very last coat. She flings the coats onto her swan-brothers and they transform back into young men -- except for the youngest, with the incomplete coat, who is left with a wing in the place of one arm. (And there begins a whole other tale.)

This was one of my favorite stories as a child, for I too had brothers in harm's way, and I too was a silent sister who worked as best I could to keep them safe, and sometimes succeded, and sometimes failed, as the plot of our lives unfolded. The story confirmed that courage can be as painful as knitting coats from nettles, but that goodness can still win out in the end. Spells can broken, and gentle, loving persistence can be the strongest magic of them all.

I grew up with the story, but not with Urtica dioica: "common nettles" or "stinging nettles." I imagined them as dark, thorny, and witchy-looking -- and although they're actually green and ordinary, growing thickly in fields and hedges here in Devon, nettles emerge nonetheless from the loam of old stories and glow with a fairy glamour. It is a plant that heralds the return of spring, a tonic of vitamins and minerals; and also a plant redolent of swans and spells, of love and loss and loyalty, of ancient powers skillfully knotted into the most traditional of women's arts: carding, spinning, knitting, and sewing.

According to the Anglo-Saxon "Nine Herbs Charm," recorded in the 10th century, sti��e (nettles) were used as a protection against "elf-shot" (mysterious pains in humans or livestock caused by the arrows of the elvin folk) and"flying venom" (believed at the time to be one of the four primary causes of illness). In Norse myth, nettles are associated with Thor, the god of Thunder; and with Loki, the trickster god, whose magical fishing net is made from them. In Celtic lore, thick stands of nettles indicate that there are fairy dwellings close by, and the sting of the nettle protects against fairy mischief, black magic, and other forms of sorcery.

Nettles once rivalled flax and hemp (and later, cotton) as a staple fiber for thread and yarn, used to make everything from heavy sailcloth to fine table linen up to the 17th/18th centuries. Other fibers proved more economical as the making of cloth became more mechanized, but in some areas (such as the highlands of Scotland) nettle cloth is still made to this day. "In Scotland, I have eaten nettles," said the 18th century poet Thomas Campbell, "I have slept in nettle sheets, and I have dined off a nettle tablecloth. The young and tender nettle is an excellent potherb. The stalks of the old nettle are as good as flax for making cloth. I have heard my mother say that she thought nettle cloth more durable than any other linen."

"Nettles have numerous virtues," writes Margaret Baker in Discovering the Folklore of Plants. "Nettle oil preceded paraffin; the juice curdled milk and helped to make Cheshire cheese; nettle juice seals leaky barrels; nettles drive frogs from beehives and flies from larders; nettle compost encourages ailing plants; and fruits packed in nettle leaves retain their bloom and freshness.

"Mixing medicine and magic, a healer could cure fever by pulling up a nettle by its roots while speaking the patient's name and those of his parents. Roman soldiers in damp Britain found that rheumatic joints responded to a beating with nettles. Tyroleans threw nettles on the fire to avert thunderstorms, and gathered nettle before sunrise to protect their cattle from evil spirits."

The medicinal value of nettles is confirmed by Julie Bruton-Seal & Matthew Seal in their useful book Hedgerow Medicine:

"Nettle was the Anglo-Saxon sacred herb wergula, and in medieval times nettle beer was drunk for rheumatism. Nettle's high vitamin C content made it a valuable spring tonic for our ancestors after a winter of living on grain and salted meat, with hardly any green vegetables. Nettle soup and porridge were popular spring tonic purifiers, but a pasta or pesto from the leaves is a worthily nutritious modern alternative. Nettle soup is described by one modern writer as 'Springtime herbalism at one of its finest moments.' This soup is the Scottish kail. Tibetans believe that their sage and poet Milarepa (AD 1052-1135) lived solely on nettle soup for many years until he himself turned green: a literal green man.

"Nettle was the Anglo-Saxon sacred herb wergula, and in medieval times nettle beer was drunk for rheumatism. Nettle's high vitamin C content made it a valuable spring tonic for our ancestors after a winter of living on grain and salted meat, with hardly any green vegetables. Nettle soup and porridge were popular spring tonic purifiers, but a pasta or pesto from the leaves is a worthily nutritious modern alternative. Nettle soup is described by one modern writer as 'Springtime herbalism at one of its finest moments.' This soup is the Scottish kail. Tibetans believe that their sage and poet Milarepa (AD 1052-1135) lived solely on nettle soup for many years until he himself turned green: a literal green man.

"Nettles enhance natural immunity, helping protect us from infections. Nettle tea drunk often at the start of a feverish illness is beneficial. Nettles have long been considered a blood tonic and are a wonderful treatment for anaemia, as they are high in both iron and chlorophyll. The iron in nettles is very easily absorbed and assimilated. What cooks will tell you is that two minutes of boiling nettle leaves will neutralize both the silica 'syringes' of the stinging cells and the histamine or formic acid-like solution that is so painful."

At our house, spring is the time for making making nettle pancakes, soups, and breads, rich in the nutrients needed after a long, wet Dartmoor winter. Here's our family recipe for Bumblehill Nettle Soup, which is easy to make and delicious:

First, pick your nettles by pinching off the fresh leaves at the tip of the plant, leaving the plant itself intact. It's best to do this in  the spring when the plants are young and the vitamin content at its highest, before the flowers appear. Rinse your nettle tips in cold water, and cut off any woody bits or thick stems. You need to wear gloves while you handle them, but once the nettles are cooked you can safely eat them without any stinging.

the spring when the plants are young and the vitamin content at its highest, before the flowers appear. Rinse your nettle tips in cold water, and cut off any woody bits or thick stems. You need to wear gloves while you handle them, but once the nettles are cooked you can safely eat them without any stinging.

Melt some butter in the bottom of the soup pot, add a chopped onion or two, and cook slowly until softened.

Add a litre or so of vegetable or chicken stock, with salt, pepper, and any herbs you fancy.

Add 2 large potatoes (chopped), a large carrot (chopped), and simmer until almost soft. If you like your soup thick, use more potatoes.

Throw in several large handfuls of fresh nettle leaves, and simmer gently for another 10 minutes.

Add some cream (to taste), and a pinch of nutmeg. Pur��e with a blender, and serve. (If you happen to have some truffle oil in your pantry, a light sprinkling on the soup tastes terrific.) Use the left-over nettles for tea, sweetened with honey.

You can also throw young nettle leaves into pancake, crepe, scone, biscuit, and bread recipes -- just rinse them, chop them, and blanch them in boiling water (to get the sting out) first. Below, for example: savoury squares of nettle-and-herb flatbread with sea salt, and sweet nettle pancakes. (Savoury nettle pancakes, topped with stir-fried mushrooms, onions, and swiss chard, with crumbled feta cheese, is awfully good too.)

Nettles, folk tales around the world agree, have long been associated with women's domestic magic: with inner strength and fortitude, with healing and also self-healing, with protection and also self-protection, with the ability to "enrich the soil" wherever we have been planted. Nettle magic is steeped in dualities: both fierce and soft, painful and restorative, common as weeds and priceless as jewels. Potent. Tenacious. Humble and often overlooked. Resilient.

And pretty tasty too.

Pictures: The illustrations for "The Wild Swans" fairy tale are by Nadezhda Illarionova, Susan Jeffers, Mercer Mayer, Eleanor V. Abbott, Yvonne Gilbert, Helen Stratton, and Donn P. Crane. The Nettle Coat is by Alice Maher. Words: The quoted passages are from Discovering the Folklore of Plants by Margaret Baker (Shire Classics, 2008) and Hedgerow Medicine by Julie Bruton-Seal & Matthew Seal (Merlin Unwin Books, 2008). All rights reserved by the artists and authors.

Related posts: The folklore of food, and, for more on the Wild Swan fairy tale, Swan's wing. I've written about my personal connection to the fairy tale in "Transformations," but I must give you fair warning that this essay is a dark one.

May 23, 2021

Tunes for a Monday Morning

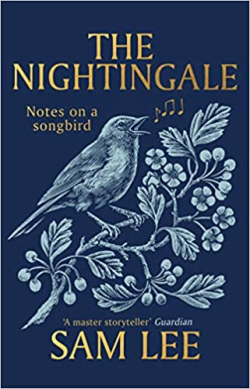

Today's music comes from British folk singer and folk song collector Sam Lee. I'm completely in love with this young man's work, and the wide variety of collaborative projects he instigates or contributes to. If you ever have the chance to see him live, please don't miss it. Sam's recordings of old ballads and Gypsy Traveller songs are wonderful, but hearing them live -- as they are meant to be heard -- is just extraordinary.

Above: A BBC profile of Lee's "Singing With the Nightingales," an annual series of events in which folk, classical, and jazz musicians collaborate with nightingales in their natural habitats. As the website explains, guests at the nightingale gatherings are invited "not just to listen to these birds in ear-tinglingly close proximity, but to share an evening around the fire, delving into your hosts��� and guest musicians' own funds of rare songs and stories." After supper by the fire, the small audience for each event is lead "in silence and darkness into the nightingale���s habitat, not only to listen to these majestic birds, but to share in an improvised collaboration; to experience what happens when bird and human virtuosi converge in musical collaboration." The BBC video above was filmed back in 2017, but the Nightingale project continues -- and Sam has just published a fine book on the subject, which I highly recommend.

Above: A BBC profile of Lee's "Singing With the Nightingales," an annual series of events in which folk, classical, and jazz musicians collaborate with nightingales in their natural habitats. As the website explains, guests at the nightingale gatherings are invited "not just to listen to these birds in ear-tinglingly close proximity, but to share an evening around the fire, delving into your hosts��� and guest musicians' own funds of rare songs and stories." After supper by the fire, the small audience for each event is lead "in silence and darkness into the nightingale���s habitat, not only to listen to these majestic birds, but to share in an improvised collaboration; to experience what happens when bird and human virtuosi converge in musical collaboration." The BBC video above was filmed back in 2017, but the Nightingale project continues -- and Sam has just published a fine book on the subject, which I highly recommend.

Below: "The Garden of England," a re-working of the folk classic "Seeds of Love" (the very first song collected by Cecil Sharpe). It appears on his latest album Old Wow, a collection of old songs molded into new forms for our troubled times. "I feel like we are living in the age of extinction, culturally as well as ecologically,��� he explains in an interview. ���My hope is that by looking to the past we can strengthen our resolve to protect the future. What I���m doing is making the richest compost I possibly can."

Above: A live recording of "The Moon Shines Bright," re-working "Wild Mountain Thyme" and classic Romany folk themes, accompanied by Elizabeth Fraser of the Cocteau Twins. The song appears on Old Wow.

Below: "Blackbird," a traditional British Traveller song peformed in Amsterdam, with Jonah Brody on piano, Joshua Green on percussion, amd Flora Curzon on violin. The song appeared on an earlier album, The Fade in Time.

Above: "The Blind Beggar," performed with Lisa Knapp and Nathaniel Mann at the Foundling Museum in London as part of their Broadside Ballads project. A broadside, the three musicians explain, "is a single sheet of inexpensive paper printed on one side, often with a ballad, rhyme, news and sometimes with woodcut illustrations. Broadside ballads, from the sixteenth to twentieth centuries, contain words and images once displayed and sung daily in Britain���s streets and inns. Although part of living traditions of folksong, popular art and literature, these illustrated printed sheets are now rare and preserved in only a few libraries." In developing the project, they spent time researching the ballads at the Bodleian, and then created new contemporary arrangements for these historic songs.

Below: "Lord Gregory" (Child Ballad #76) performed with the Choir of World Cultures (directed by Barbara Morgenstern) from Berlin.

For more on Gypsy/Traveller songs, see the short film Ballad Lands: Jonny O' the Brine (about Sam's apprenticeship to Scottish Traveller Stanley Robertson); and his talk about how he became involved with the Travellers and their songs as a young Jewish man from London.

May 21, 2021

More wildflower folklore

As the Coronavirus pandemic rolls on -- easing here, rising there, unpredictable everywhere -- I want to share the Devon countryside with all of you are still confined to urban or less wild spaces, along with a little more of the wildflower lore that's rooted in the land below our feet. I love knowing and passing on such things. "Re-storying" the land is, I believe, an important part of re-wilding the land, re-wilding our culture, and re-wilding ourselves.

In the springtime, writes herbalist Judith Berger,

"the earth herself seems overtaken with desire to create for the sake of beauty and joy, unveiling at an astounding rate those creations which were conceived and protected in winter's ground-dark womb. Young, delectable leaves shoot up out of the soil, becoming clorophyll-rich as they soak up the food of the sun's fire. Food and medicine plants carpet the ground abundantly, delighting the eyes and tastebuds with a palette of green hues and an array of distinctive earthy flavors. Daily, as light seeps into the unfurling leaves, the plants grow greener and greener with the blood of the sun. As we ingest these plants, we increase our inner fires and pulse with the blood of life, thus inspired to move through our days with the same abandon as the maiden goddess of spring."

Stitchwort (below), appears in Devon in two distinctive colors: white and pink. Greater stitchwort, with its white star-like blooms, also goes by the name star flower, thunder flower (because picking it will cause a storm), Mother Shimbles, snick needles, and snapjacks (due to the popping sound made by its seed pods as they ripen). Lesser stitchwort, with its small pink flowers, is known as piskie, or piskie flower, here in Devon -- though in fact both kinds of stitchwort are under the special protection of the piskies (our local faery folk). They zealously guard the flowers against hedgewitches, who use them for making medicines and charms of protection against piskie mischief -- including a salve that heals the "side stitches" caused when mortals are hit by elf-shot.

Stitchwort often grows among stands of nettles -- which is certainly one way to protect it from being picked. Nettles themselves are a wonderful plant (despite their sting), prized by witches, cunning men, herbalists, and wild food foragers. In Celtic lore, thick stands of nettles indicate that there are faery dwellings close by, and the sting of the nettle protects against faery enchantment, black magic, and other forms of sorcery. Historically, nettles have had a wide variety of uses, from making medicines to making cloth. "Nettle oil preceded paraffin," notes folklorist Margaret Baker; "the juice curdled milk and helped to make Cheshire cheese; nettle juice seals leaky barrels; nettles drive frogs from beehives and flies from larders; nettle compost encourages ailing plants; and fruits packed in nettle leaves retain their bloom and freshness." Today, many of us still harvest the tender top leaves of nettles in the spring. Rich in iron and vitamins, they are an excellent tonic for the immune system when cooked in soups and stews, or brewed for tea.

(We'll take a closer look at the folklore of nettles in a post next week.)

Germander speedwell ( above), also known as birds-eye or angels-eye, is a flower associated with vision, with magical oinments allowing mortals to see faeries, and with healing afflictions of the eyes -- whether medical or caused by witchcraft. Although largely unmentioned by modern herbalists, it was once considered a valuable plant in hedge-lore here in the West Country. A tea made from its leaves and flower petals is said to be good for coughs (when brewed at strength), or settling the nerves (when brewed more delicately), while also fostering clarity of vision, focus, and purpose.

According to Welsh folklore, wild Welsh poppies (above) don't flourish outside Wales itself -- but in fact they are ubiquitous here in the West Country, and in other parts of the British Isles too. Perhaps they are bigger and brighter in Wales...?

Although the Welsh poppy (Meconopsis cambrica) is somewhat different than the opium poppy (Papaver somniferum), it too is associated with sleep, dreams, the spirit world, and various forms of divination. Yellow poppies must never be brought into the house -- they will cause headaches, storms, or lightning strikes -- but wild poppy seeds placed under a pillow will show a young man or maid their future lover's face, or give the dreamer the answer to any question posed while falling asleep. The seeds can also be carried in one's pocket, or strewn in a circle around one's home, to provide protection from faery enchantments, especially those that cause confusion or memory loss.

The cuckoo flower (above) is said to herald the first cuckoo of spring. It grows in damp, grassy meadows and bogs, its petals tinted pink or lavendar, and is also known by the names lady's-smock, milkmaid, May flower, and fairy flower. Associated with the revels of May, hedgewitches used various parts of the plant for love potions and fertility spells -- as well as for the opposite: charms intended to keep love and fertility at bay. Cuckoo flower teas and tonics restored appetites diminished by poor health, while also aiding digestion, treating survy, and easing bowel complaints. The leaves, when young, are edible, tasting peppery, like cress.

In the folk tradition of the West Country, buttercups (above) are a benificent plant -- associated with the sun, yellow butter and the dairy, and ease in domestic labor. On May Day, farmers rubbed the udders of their cows with buttercup flowers to increase the yield and richness of their milk; this also protected them from theft by faeries -- who were always eager to improve their herds of fairy cattle by interbreeding with cows from mortal fields. Buttercups are toxic to ingest so medicinal use of the plant is limited, although some old herbals suggest that a poulstice made of the crushed flowers and leaves is helpful in relieving colds, coughs, and bronchial complaints. "Buttercup water," made by infusing the flower petals in water heated by the sun, was used to bathe sore eyes, and "sweeten" the complexion. Buttercups are part of Rananculus family, related to spearwort, crowfoot and lesser celandine. It was once believed that swallows fed their young on a diet of these flowers, giving them prophetic abilities and clear sight.

Red campion (above and below) -- also known as ragged-robin or robin flower -- is associated with Robin Goodfellow (or Puck), a faery Trickster who is charming, sly, amoral, and rather dangerous to encounter. In some parts of country, the picking of campion is discouraged, for this invites the faeries' attention -- but here in the West Country, it's a lucky flower. Campion in the house represents the faeries' blessing, provided it's been picked with care and respect. Red campion is not edible, and its herbal use is limited -- but the roots have been used to make a soap substitute, and the flowers for charms and spells to ward against loneliness.

In Norse myth, wild columbine (below) is the flower of Freya, goddess of love, sensuality, and women's independence; in Celtic lore, too, it's a flower associated with women and their Mysteries. Columbine's primary use in hedgerow medicine was as an abortificant: its seeds were ground and mixed wine and other herbs to produce this effect; and then used with wine and a different set of herbs to restore the woman's strength. Also known as Granny's bonnet, lady's shoes, sow wort, and lion's herb, the flower is linked with both the dove and the eagle, with peace and war, and the balancing of opposites: strength in fragility and fragility in strength. Columbine was used for spells invoking courage, wisdom, and clarity in making choices.

Herb Robert (below) is a modest little flower, but it's become one of my favorite sights in the hedgerows...and in our garden too, where it kept appearing in spaces that I'd intended for other things. At first, I confess, I pulled it out as a troublesome weed, until its gentle persistence caused me to look a little closer at this tiny wildflower. I learned that the plant was once much prized by herbalists (and magicians!) in medieval times; and that herbalist today hail its ability to boost the immune system (precisely the thing I most needed). In folklore, according to Margaret Barker, herb Robert is known as "the plant of equality, all its parts being equal and harmonious." It's also another faery plant: its appearance in the garden betokes the blessing of the particular spirits who "quicken" all green living things. The great mystic and herbalist Hildegard of Bingen extolled the virtues of this humble flower, recommending its use (in a powdered form, eaten on bread) to strengthen the blood, balance the mind, and ease all heartbreak.

Valerian (below) is another that has moved itself from the hillside to our garden, rooting firmly in a sunny front slope. "Valerian's botanical name (Valerianna officinalis) comes from the Latin word valere, 'to be strong,' " writes Margaret Baker. "It is said to be a witch-deterrent, to provoke love, and to be a telling aphrodisiac. In the West of England a girl who wore a sprig would never lack lovers." Well. You can't beat that.

In her lovely book Herbal Rituals, Judith Berger envisions the springtime as the Goddess in her maiden aspect:

"In Hebrew the word for life, chai, is also the root of the word meaning wild she-animal, (chaiya), and this is how I see the spring: as a wild, untamed maiden bounding over the dark earth, her footfall touching all life with more life. Hair flying behind her, she leaves in her wake a trail of color, scent, and nourishment, her mood of wicked delight spreading across the ground like green fire. Roused by her passion, the green nations leap toward the sun, brimming with sheer joy, until everywhere we turn our heads we find life unfolding, changing shape, and blossoming, each form in nature dripping with beauty and transformed by the nurture of sun, rain, earth, and air."

Above, the Lady of Bumblehill (a statue made by my friend Wendy Froud) stands in our back courtyard with flowers at her feet. The flowers change a little every year, as Welsh poppies, foxgloves, columbine and other plants self-seed and move about the land. I love these untameable flowers...and so does Tilly. Here she is at just ten weeks old, mesmorized by a hawkweed's bloom. Entranced by its colour. Scenting its magic. And listening closely to its stories.

The passages quoted above are from Herbals Rituals by Judith Berger (St. Martin's Press, 1998) and Discovering the Folklore of Plants by Margaret Baker (Shire Classics, 2008). All rights reserved by the authors.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 710 followers