Terri Windling's Blog, page 18

April 15, 2021

On creative DNA

On Tuesday we were talking about the interplay between finding creative inspiration in others' work and learning to develop a voice or style uniquely our own. Here's choreographer Twyla Tharp's take on the subject, from her useful book The Creative Habit:

"In my early years in New York City, I studied with the choreographer Merce Cunningham. Merce had a corner studio on the second floor at 14th Street and 8th Avenue, with windows on two sides. During breaks in classes, I watched a lot of traffic out of those windows, and I observed that the traffic patterns were just like Merce's dances -- both appear random and chaotic, but they're not. It occurred to me that Merce often looked out of those windows, too. I'm sure the street pattern was consoling to him, reinforcing his discordant view of the world. His dances are all about chaos, and dysfunction. That's his creative DNA. He's very comfortable with chaos and plays with it in all his work. My hunch is that he came to chaos before he came to that studio, but I can't help wondering if maybe he selected the place because of the chaos outside the windows.

"Of course, when I looked out those windows, I didn't see the patterns that Merce did, and I certainly didn't find solace in their discordance. I didn't 'get it' the way he did. I wasn't hard-wired that way. It wasn't part of my creative DNA.

"I believe that we all have strands of creative code hard-wired into our imaginations. These strands are as solidly imprinted in us as the genetic code that determines our height and eye color, except they govern our creative impulses. They determine the forms we work in, the stories we tell, and how we tell them. I'm not Watson and Crick; I can't prove this. But perhaps you also suspect it when you try to understand why you're a photographer, not a writer, or why you always insert a happy ending into your story, or why all your canvases gather the most interesting material at the edges, not the center. In many ways, that's why art historians and literature professors and critics of all kinds have jobs: to pinpoint the artist's DNA and explain to the rest of us whether the artist is being true to it in his or her work. I call it DNA; you may think of it as your creative hard-wiring or personality.

"When I apply a critic's temperament to myself, to see if I'm being true to my DNA, I often think in terms of focal length, like that of a camera lens. All of us find comfort in seeing the world either from a great distance, at arm's length, or in close-up. We don't consciously make that choice. Our DNA does, and we generally don't waver from it. Rare is the painter who is equally adept at miniatures and epic series, or the writer who is at home in both sprawling historical sagas and minimalistic short stories.

"The photographer Ansel Adams, whose black-and-white panoramas of the unspoiled American West became the established notion of how to 'see' nature (and, no small feat, helped spawn the environmental movement in the United States), is an example of an artist who was compelled to view the world from a great distance. He found solace in lugging his heavy camera equipment on long treks into the wilderness or to a mountaintop so he could have the widest view of land and sky. Earth and heaven in their most expansive form was how Adams saw the world. It was his signature, and expression of his creative temperature. It was his DNA.

"Focal length doesn't only apply to photographers. It applies to any artist. The choreographer Jerome Robbins, whom I have worked with and admire, tended to see the world from a middle distance. The sweeping vision was not for him. Robbin's point of view was right there on the stage. Others besides me have noted how often Robbins had his dancers watch someone else dance. Think of his very first ballet, Fancy Free. Boys watch girls. Girls then watch boys. And upstage, the bartender watches everything as if he were Robbins' surrogate. His is the point of view from which the ballet's story is told. Robbins is both observing and observed, safely, at a middle distance.

"It helps to know that Robbins grew up wanting to be a puppeteer, and I think this way of seeing the world -- controlling events from behind the scenes or above, but not so distant that you cannot maintain contact with the action on stage -- pervades almost everything he created. I doubt it was something he chose consciously, but in terms of creative DNA, it was a dominant strand in his work. Check out the film of West Side Story, which Robbins choreographed and co-directed. The story line is famously adapted from Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet -- in other words, it's not his own. Yet even with a borrowed plot, you still see Robbins' impulses coming to the fore, imprinting themselves on the drama and the dancing. Nearly every group scene involves performers being observed. Jets watch Sharks, Sharks watch Jets, girls watch boys, boys watch girls. This is not how Shakespeare did it. But it is Robbins' world view.

"Other artists see the world as if it is one inch from their nose. The novelist Raymond Chandler, whose Philip Marlowe books like Farewell, My Lovely and The Long Goodbye are classics of American hardboiled detective fiction, was obsessed with detail. He works in extreme close-up, a succession of tight shots that practically put us inside the characters' skulls. The plots of his stories are often incomprehensible -- he believed that the only way to keep the reader from knowing whodunit was not to know yourself -- but his eye for descriptive detail was razor-sharp. Here is the opening of his first full-length novel, The Big Sleep:

'It was about eleven o'clock in the morning, mid October, with the sun not shining and a look of hard wet rain in the clearness of the foothills. I was wearing my powder-blue suit, with dark blue shirt, tie and display handkerchief, black brogues, black wool socks with dark blue clocks on them. I was neat, clean, shaved and sober, and I didn't care who knew it. It was everything the well-dressed private detective ought to be. I was calling on four million dollars.'

"Chandler kept lists of observed details from his life and from the people he knew: a necktie file, a shirt file, a list of overheard slang expressions, as well as character names, titles and one-liners he intended to use sometime in the future. He wrote on half-sheets of paper, just twelve to fifteen lines per page, with a self-imposed quota that each sheet must contain what he called 'a little bit of magic.' The 'life' in his stories was in the details, whether his hero Marlowe was idling in his office or in the middle of a brutal confrontation. No long-distance musing the the state of the world. No middle-distance group shots. Just a steady stream of details, piling one one on top of the other, until a character or scene takes shape and a vivid picture emerges. Up close was Chandler's focal length. If some people like to wander through an art museum standing back from the paintings, taking in the effect the artist was trying to achieve, while others need a closer look because they're interested in the details, then Chandler was the kind of museum-goer who pressed his nose up to the canvas to see how the artist applied his strokes. Obviously, all of us look at paintings from each of these vantage points, but we focus best at some specific length along the spectrum.

"I don't mean to get too caught up in observational focal length. It's one facet out of many that makes up an artist's creative identity. Yet once you see it, you begin to notice how it defines all the artists you admire. The sweeping themes of Mahler's symphonies are the work of a composer with wide vision. He sees grand architecture from a distance. Contrast that with a miniaturist like Satie, whose delicate compositions reveal a man in love with detail. (It's only the giants like Bach, C��zanne, and Shakespeare who could work in many focal lengths.)

"But that's the point. Each of us is hard-wired a certain way. And that hard-wiring insinuates itself into our work. That's not a bad thing. Actually, it's what the world expects from you. We want our artists to take the mundane materials of our lives, run it through their imaginations, and surprise us. If you are by nature a loner, a crusader, a jester, a romantic, a melancholic, or any one of a dozen personalities, that quality will shine through your work....A little self-knowledge goes a long way. If you understand the strands of your creative DNA, you begin to see how they mutate into common threads in your work. You begin to see the 'story' you're trying to tell; why you do the things you do (both positive and self-destructive); where you are strong and where you are weak (which prevents a lot of false starts) and how you see the world and your function in it."

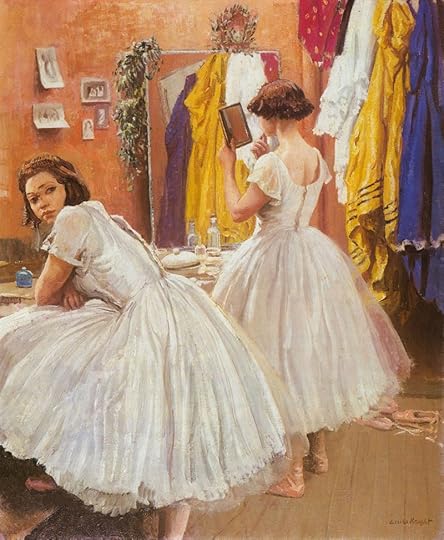

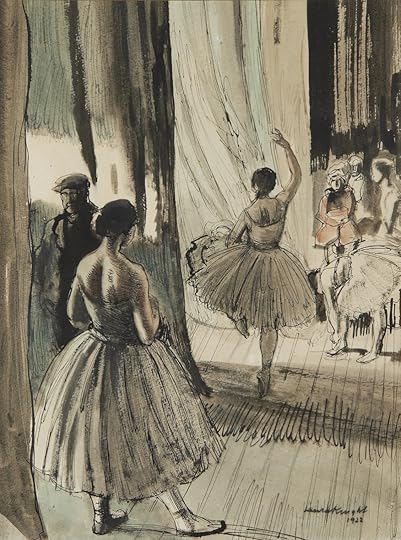

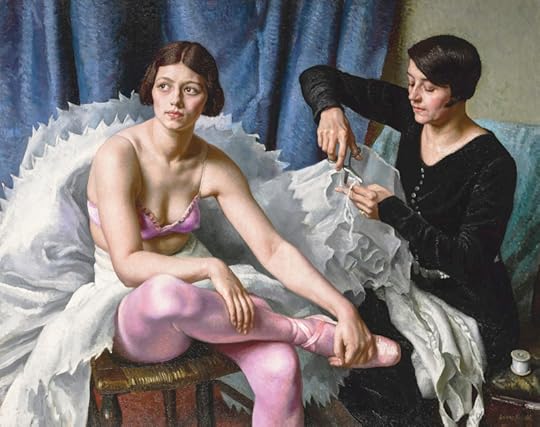

The imagery today is by the great British artist Dame Laura Knight (1877-1970), whose paintings and drawings of ballet dancers, in my opinion, are up there with Degas' dancers in atmosphere and beauty, capturing the aesthetics of her generation.

Born to an impoverished family in Derbyshire, Knight attended the Nottingham School of Art on a scholarship, and went on to become one of the most celebrated painters of her day. With her husband, Harold Knight (a landscape painter and portraitist), she lived in a succession of rural art colonies in Yorkshire, the Netherlands, and Cornwall, gradually moving from realism to a more Impressionist style. At school, she'd been forbidden to attend classes that used nude models (women students were given plaster casts to draw instead), and she insisted on drawing from life thereafter -- which caused consternation in some quarters but never dissuaded her from working as she saw fit.

Knight had a keen interest in lives lived on the margins -- gypsies, circus folk, and other wanderers -- and she traveled across the country with small circus troupes, living and painting in all kinds of conditions. This proved good preparation for her subsequent role as an official War Artist during World War II, documenting daily life on the war's home front and paying particular attention to the role of women in the war effort. Afterwards, she traveled to Germany to paint the Nuremberg war crime trials, then returned to her beloved dance and theatre subjects in the post-war years.

In 1967, Knight wrote to a friend:

"I had what has been called my 90th birthday a week or so ago. It's a bit shattering to suddenly become an antiquity. I don't believe I'm really as old as that, but everyone assures me that it is true. All the same I don't believe them. I'm not going to fall into a decline and I cannot give up hard work or the enjoyment of life itself."

She died two years later, creating art and exhibiting art right up to the very end.

Words: The passage quoted above is from The Creative Habit by Twyla Tharp (Simon & Schuster, 2003); all rights reserved by the author. The poem in the picture captions is from Poetry (April, 2008); all rights reserved by the poet and translator.

Pictures: Backstage paintings of the Ballets Russes during their London seasons by Dame Laura Knight. The final image is a self-portrait, painted by the artist in 1913.

April 13, 2021

Myth & Moor update

My apologies for the lack of a post today. We had a bit of a fright with Tilly, and while I don't want to go into the details here, I'm relieved to say that all is well now, and I'll be back to Myth & Moor tomorrow.

Standing on the shoulders of giants

I've just finished reading Kent Nerburn's Dancing With the Gods: Reflections on Art & Life, and I'd like to pass on a final passage from the book discussing artistic influence -- not as a thing to be wary of but, rather, to be celebrated. He writes:

"One of the great joys of the creative life is getting to live in dialogue with works of genius that have been created by artists who have proceeded us. We observe their work across the barriers of time and space, and they become our brothers and sisters who have walked a path that shows us, however dimly, our own way forward.

"I remember vividly the exhilaration I felt in my teenage years when I first encountered Antoine de Saint-Exup��ry's Night Flight. For the first time, I realized that writing was more than topic sentences and supporting statements. I would hide under my covers at night and try, by lamplight, in my own stumbling way, to create sentences that sang like his.

"And then there was the moment when I came across a stream-of-consciousness passage in John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath that was like no prose I had read before. For weeks, in the hidden pages of my school notebook, I struggled to describe the world around me in the same fragmentary, cinematic manner. The experience came again as I read the works of Carl Sandburg and, later, studied the sculptures of Donatello. These artists spoke to me across time and space and became my secret friends and mentors. In my heart of hearts I dreamed of creating like they could create, and I did what I could to learn the secrets that lived inside their works.

"We who work in the arts stand unashamedly upon the shoulders of those who came before. In the secrecy of our creative lives we try to do what those who have inspire us have done. We trace their lines, we copy their movements; we mimic their prose, we practice their phrasings. Whether with a brush or a chisel, our body or a pen or our voices, we try to enter into their creative decisions by recreating those decisions in our own work.

"It is not mere copying; it is mentoring. It is letting our hands and hearts and minds be guided by theirs. To know how Nureyev achieved the muscularity of his expression, or how Donatello carved a risk, or how Willie Nelson phrased a song, we must attempt it ourselves. We must inhabit the experience and try to make it our own in order to see the choices that were made. We are, in effect letting them become our teachers."

This is exactly what I was trying to get at in an essay of mine, "On Influence," published back in 2011. You can find it here. Ten years on from writing that piece, I'd love to hear your thoughts about artistic influence and the role it has (or hasn't) played in the development of your work.

Words: The passage above is from Dancing With the Gods: Reflections on Life and Art by Kent Nerburn (Canongate, 2018); all rights reserved by the author. The poem in the picture captions is from The Collected Poems of Denise Levertov (New Directions, 2013); all rights reserved by the Levertov estate.

Paintings: Two illustrations by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939) for Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens by J.M. Barrie. Photographs: Tilly stops for her daily visit with her good friend Old Oak.

April 11, 2021

Tunes for a Monday Morning

On a quiet morning in spring, let's starting the day with women's voice....

Above: "May Morning Dew," performed by singer/songwriter Siobhan Miller, from Penicuik, Scotland, accompanied by Kris Drever, Innes White, Megan Henderson, John Lowrie, and Euan Burton. This track appears on her most recent album, All in Not Forgotten (2020).

Below: The title song from the same album.

Above: "My Love is Like a Red Red Rose" performed by singer/songwriter Josienne Clarke, with Ben Walker on guitar, from their album Fire & Fortune (2013). Clarke was raised in West Sussex and now lives in Scotland.

Below: "May the Kindness," written by David Wood and performed by English folksinger and fiddle player Jackie Oates. The song appeared on her third album, Hyperboreans (2009).

Above: "Anchor" by singer/songwriter Emily Mae Winters, who was born in England, raised in Ireland, and is now based in London. The song appeared on her album Siren Serenade (2017).

Below: "One of These Days," performed live for the Shadow Scape Sessions. The song appeared on her album High Romance (2019).

The artwork today is "The Mill" and "Pilgrim in the Garden" by Sir Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898), who was part of the second wave of the Pre-Raphaelite movement. (For an post on the Pre-Raphaelites in relation to the fantasy field, go here.)

April 9, 2021

The stories that take root

We've been talking about the process of art-making this week, and the dark places it can take us to, but not about why we do it, even when the going is hard. I was reminded of this post from the archives, first published here in 2015. (I can't get over how young Tilly looks!) There's nobody better than Jeanette Winterson at explaining why art matters....

From "Testimony Against Gertrude Stein," published in Art Objects by Jeanette Winterson:

"We mostly understand ourselves through an endless series of stories told to ourselves by ourselves and others. The so-called facts of our individual words are highly colored and arbitrary, facts that fit whatever fiction we have chosen to believe in. It is necessary to have a story, an alibi that gets us through the day, but what happens when the story becomes scripture? When we can no longer recognize anything outside our own reality?

"We have to be careful not to live in a state of constant self-censorship, where whatever conflicts with our world view is dismissed or diluted until it ceases to be a bother. Struggling against the limitations we place on our minds is our own imaginative capacity, a recognition of an inner life often at odds with the internal figurings we spend so much energy supporting.

"When we let ourselves respond to poetry, to music, to pictures, we are clearing out a space where new stories can root, in effect we are clearing a space for new stories about ourselves."

The passage just quoted nails, for me, precisely why we need art in our lives and not just the familiar, repetitive stories of mass entertainment, enjoyable as they may be. Entertainment amuses, distracts, and consoles us, and that has its use and it has its value, but it's not the same use or value of art. Art enlarges us. Transforms us. Heals what is broken inside us. Deepens our understanding of ourselves, each other, and the world around us.

"Art is central to all our lives, not just the better-off and educated, " Winterson once said in an interview. "I know that from my own story, and from the evidence of every child ever born -- they all want to hear and to tell stories, to sing, to make music, to act out little dramas, to paint pictures, to make sculptures. This is born in and we breed it out. And then, when we have bred it out, we say that art is elitist, and at the same time we either fetishize art -- the high prices, the jargon, the inaccessibility -- or we ignore it. The truth is, artist or not, we are all born on the creative continuum, and that is a heritage and a birthright of all of our lives."

Amen.

The first quote by Jeanette Winterson is from Art Objects: Essays on Ecstasy & Effrontery (Jonathan Cape, 1996); the second quote is from "Up Front: Talking With Jeanette Winterson" (The New York Times, Dec. 19, 2008). All rights reserved by the author.

On art, risk, and carrying on

Today, here's one last piece on fear, risk, and uncertainty in art-making. It comes from Art & Fear by David Bayles and Ted Orland :

"To make art is to sing with the human voice. To do this you must first learn that the only voice you need is the voice you already have. Art work is ordinary work, but it takes courage to embrace that work, and wisdom to mediate the interplay of art and fear. Sometimes to see your work's rightful place you have to walk to the edge of the precipice and search the deep chasms. You have to see that the universe is not formless and dark throughout, but awaits simply the revealing light of your own mind. Your art does not arrive miraculously from the darkness, but is made uneventfully in the light.

"What veteran artists know about each other is that they have engaged the issues that matter to them. What veteran artists share in common is that they have learned how to get on with their work. Simply put, artists learn how to proceed or they don't. The individual recipe any artist finds for proceeding belongs to that artist alone -- it's non-transferable and of little use to others. It won't help you to know exactly what Van Gogh needed to gain or lose in order to get on with his work. What is worth recognizing is that Van Gogh needed to gain or lose at all, that his work was no more inevitable than yours, and that he -- like you -- had only himself to fall back on.

"Today, more than it was however many years ago, art is hard because you have to keep after it so consistently. On so many different fronts. For so little external reward. Artists become veteran artists only by making peace not just with themselves, but with a whole range of issues. You have to find your work all over again all the time, and to do that you have to give yourself maneuvering room on many different fronts -- mental, physical, temporal. Experience consists of being able to reoccupy useful space easily, instantly.

"In the end, it all comes down to this: you have a choice (or more accurately a rolling tangle of choices) between giving your work your best shot and risking that it will not make you happy, or not giving it your best shot -- and thereby guaranteeing that it will not make you happy. It becomes a choice between certainty and uncertainty. And curiously, uncertainty is the comforting choice."

Photographs: The hound at one of our favourite spots on the hill behind the studio. I often sit and work here in the spring, nested among granite and moss, while Tilly watches ponies and sheep drift through the valley below. By summertime the pathway to these rocks will be impenetrable, swallowed up in bracken and briars. This is a secret place, a faery place, opening up and disappearing again as the seasons turn. Folklore warns us to be careful of such spots lest we, too, vanish under the thorns.

Words & Pictures: The passage above is from Art & Fear: Observations on the Perils (and Rewards) of Art-making by David Bayles and Ted Orland (The Image Continuum, 1993). The poem in the picture captions is from All One Breath by John Burnsides (Cape Poetry, 2014). All rights reserved by the authors. The drawings are by Eleanor Vere Boyle (1825-1916) and Walter Crane (1845-19150.

April 8, 2021

On art, magic, and forgiveness

Following Tuesday's post on losing our way in creative projects, and Wednesday's post on the value of uncertainty, here is more advice for navigating the "Dark Forest" of art-making: when our plans collapse, our path disappears, and we must forge ahead into the unknown.

From Dancing With the Gods: Reflections on Life and Art by Kent Nerburn:

"As a creator, you need to respect, even savour, the magic of accident and care less about what is being lost [ie, the artwork as you'd first imagined it] than what is being born [which is sometimes quite different]. Remember that any work of art, in its becoming, follows the rules of evolution, not the rules of human construction: every form remakes itself as new information is discovered and internalised. Decisions build upon each other, steps lead to further steps. Soon enough the place of beginning is but a distant memory, and you are wandering into a new land where the possibilities are limited only by your courage and talent and imagination.

"When I feel myself lost in the midst of a project, I like to remind myself of the separate skills of the architect and the gardener. The architect designs and builds; he knows the desired outcome before he begins. The gardener plans and cultivates, trusting the sun and weather and the vagaries of chance to bring forth a bloom. As artists, we must learn to be gardeners, not architects. We must seek to cultivate our art, not construct it, giving up our preconceptions and presuppositions to embrace accidents and mystery. Let moments of darkness become the seedbeds of growth, not occasions of fear.

"If you would truly be an artist, you must believe that your art -- whether interpretation, object, or performance -- is bigger than the idea that gave it birth. The moments when you are feeling most lost are simply the moments when your art is seeking new growth. Embrace them. Celebrate them. They are the moments of magic when you are most open to creative possibility.

"And it is magic, when it occurs, that turns cold ideas into living art."

I agree with Nerburn, yet feel we must acknowledge that giving up our initial vision of a piece in order to cultivate its growth can be hard, even painful, to do. The vision in our head is usually so much better than the artwork we actually make: the shining idea brought down to the physical plane, bristling with mortal imperfections. How do we "trust the process" when the process leads from shimmering dream to earthy actuality? Ann Patchett addresses this subject in her essay "The Getaway Car":

"Allan Gurganus taught me how to love the practice [of writing], and how to write in a quantity that would allow me to figure out for myself what I was actually good at. I got better at closing the gap between my hand and my head by clocking in the hours, stacking up the pages. Somewhere in all my years of practice, I don't know where exactly, I arrived at the art. I never learned how to take the beautiful thing in my imagination and put it on paper without feeling I killed it along the way. I did, however, learn how to weather the death, and I learned how to forgive myself for it.

"Forgiveness. The ability to forgive oneself. Stop here for a few breaths and think about this, because it is the key to making art and very possibly the key to finding any semblance of happiness in life. Every time I have set out to translate the book (or story, or hopelessly long essay) that exists in such brilliant detail on the big screen of my limbic system onto a piece of paper (which, let's face it, was once a towering tree crowned with leaves and a home to birds), I grieve for my own lack of intelligence. Every. Single. Time.

"Were I smarter, more gifted, I could pin down a closer facsimile of the wonders I see. I believe that, more than anything else, this grief of constantly having to face down our own inadequacies is what keeps people from being writers. Forgiveness, therefore, is the key. I can't write the book I want to write, but I can and will write the book I am capable of writing. Again and again throughout the course of my life I will forgive myself."

Forgiveness. Faith in ourselves and the work. Acceptance of fear and uncertainty. These are all skills we need to make art, acquired painstakingly over the years. (It is one of the gifts of ageing in this profession.)

The dark of the forest never gets any lighter, but with practice we learn how to see in the dark, and we carry on.

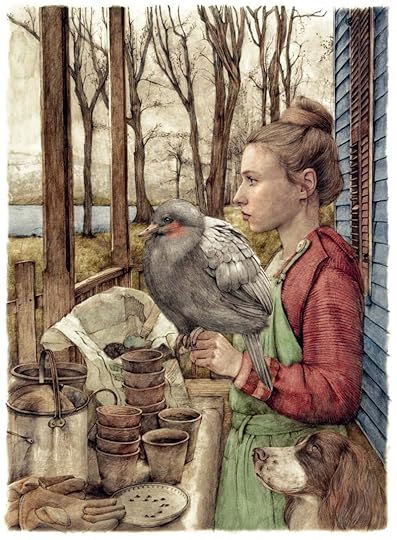

The sumptuous imagery today is by Lizzie Riches, a British painter and muralist whose work is regularly exhibited in London, Paris, New York, Chicago, and further afield. A biography from one of her galleries notes that she "was born in East London in 1950 and grew up near Epping Forest, where she first developed a love of natural history. She went to Camberwell School of Art and to Goldsmiths, but felt out of sympathy with the painting styles of the late sixties and preferred to develop her own visual language. Riches lived for many years in rural Suffolk; however, it was not the landscape that inspired her, but the birds, animals, plants and insects that she found there. Her interests have widened to exotic flora and fauna, and she is particularly fascinated by the relationship between human civilisation and the natural world."

You can see more of her work on the Red Dot Galleries and Portal Painters websites, or on her beautiful Instagram page.

Words: The Kent Nerburn passage above is from Dancing With the Gods (Canongate, 2018). The Ann Patchett passage is from her essay "The Getaway Car," published in her essay collection This is the Story of a Happy Marriage (Harpers, 2013). Both books are highly recommended. All rights reserved by the authors.

Pictures: The paintings above at The Gardener's Assistant, Fauna, Flora, A Personification of the Sense of Hearing, The Rose of Seething Lane, Silvanus: Past Present Future, and A Bird in the Hand by Lizzie Riches; all rights reserved by the artist. Many thanks to Brigit Strawbridge Howard (author of Dancing With Bees) for introducing me to her work.

A related post on gardening & art-making: "Harvesting stories."

April 7, 2021

On art, fear, and the value of uncertainty

Art-making is a magical process; but, as we discussed yesterday, it can also be a challenging one. In the journey from the start to the finish of a project there are problems to solve, questions to answers, errors in planning or technical execution to recognize and resolve, often with deadlines looming and the fearful possibility of failure. Making art requires vision and skill, but it also needs a great deal of faith. Faith in the project. Faith in yourself. And the courage (or stubborn tenacity) to keep on working through the bad days as well as the good.

In Art and Fear, David Bayles and Ted Orland address the perils and rewards of creative work, focusing on the things that hold us back and how to overcome them. What separates artists from ex-artists, they write,

"is that those who challenge their fears, continue; those who don't, quit. Each step in the art-making process puts the issue to the test.

"Fears arise when you look back, and they arise when you look ahead. If you're prone to disaster fantasies, you may even find yourself caught in the middle, staring at your half-finished canvas and fearing both that you lack the ability to finish it, and that no one will understand you if you do.

"More often, though, fears arise in those entirely appropriate (and frequently recurring) moments when vision races ahead of execution. Consider the story of the young student -- well, David Bayles, to be exact -- who began piano studies with a Master. After a few months' practice, David lamented to his teacher, 'But I can hear the music so much better in my head than I can get out of my fingers.'

"To which the Master replied, 'What makes you think that ever changes?'

That's why they're called Masters. When he raised David's discovery from an expression of self-doubt to a simple observation of reality, uncertainty became an asset. Lesson for the day: vision is always ahead of execution -- and it should be. Vision, uncertainty, knowledge of materials are inevitabilities that all artists must acknowledge and learn from: vision is always ahead of execution, knowledge of materials is your contact with reality, and uncertainty is a virue."

Materials, they say, are among the few elements of art-making you can hope to control; but for everything else,

"well, conditions are never perfect, sufficient knowledge rarely at hand, key evidence always missing, and support notoriously fickle. All that you do will inevitably be flavoured with uncertainty -- uncertainty about what you have to say, about whether the materials are right, about whether the piece should be long or short, indeed about whether you'll ever be satisfied with anything you make. Photographer Jerry Uelsmann once gave a slide lecture in which he showed every single image he had created in the span of one year: some hundred-odd pieces -- all but about then of which he judged insufficient and destroyed without ever exhibiting. Tolstoy, in the Age Before Typewriters, re-wrote War & Peace eight times and was still revising galley proofs as it finally rolled onto the press. William Kennedy gamely admitted that he wrote his own novel Legs eight times, and that 'seven times it came out no good. Six times it was especially no good. The seventh time out was pretty good, though it was way too long. My son was six years old by then and so was my novel and they were both about the same height.'

"It is, in short, the normal state of affairs. The truth is that the piece of art which seems so profoundly right in its finished state may earlier have been only inches or seconds away from total collapse. Lincoln doubted his capacity to express what needed to be said at Gettysburg, yet pushed ahead anyway, knowing he was doing the best he could to present the ideas he needed to share. It's always like that. Art is like beginning a sentence before you know its ending. The risks are obvious: you may never get to the end of the sentence at all -- or having got there, you may not have said anything. This is probably not a good idea in public speaking, but it's an excellent idea in making art.

"In making art you need to give yourself some room to respond authentically, both to your subject matter and to your materials. Art happens between you and something -- a subject, an idea, a technique -- and both you and that something need to be free to move. Many fiction writers, for instance, discover early on that making detailed plot outlines can be an exercise in futility; as actual writing progresses, characters increasingly take on a life of their own, sometimes to the point that the writer is as suprised as the eventual reader by what their creations say and do. Laurence Durrell likened the process to driving construction stakes in the ground: you plant a stake, run fifty yards ahead and plant another, and pretty soon you know which way the road will run. E.M. Forster recalled that when he began writing A Passage to India he knew that the Malabar Caves would play a central role in the novel, that something important would surely happen there -- it's just that he wasn't sure what it would be.

"Control, apparently, is not the answer. People who need certainty in their lives are less likely to make art that is risky, subversive, complicated, iffy, suggestive, or spontaneous. What's really needed is nothing more than a broad sense of what you are looking for, some strategy for how to find it, and an overriding willingness to embrace mistakes and surprises along the way. Simply put, making art is chancy -- it doesn't mix well with predictability. Uncertainty is the essential, inevitable and all-pervasive companion to your desire to make art. And tolerance for uncertainty is the prerequisite to succeeding."

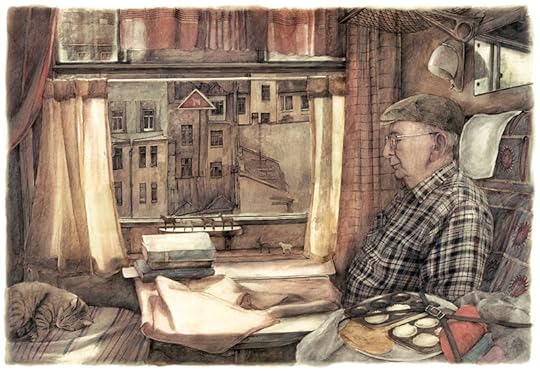

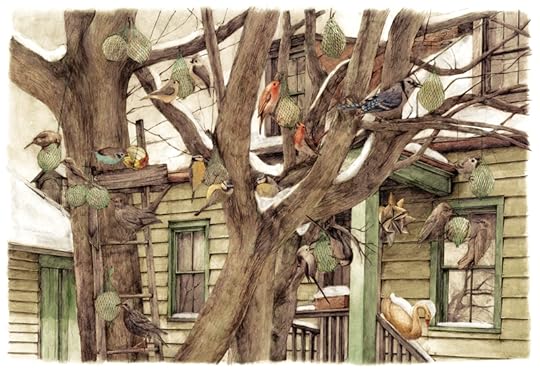

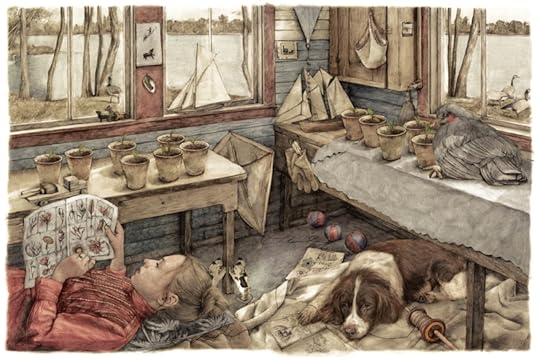

The imagery today is by Sonja Danowski, an artist, author, and illustrator based in Berlin. Her picture books for children and adults include In the Garden, Puppet Theater, Smon Smon, Little Night Cat, Perfume Village, My Family, Mountain Goats, The Grass House, Forever Flowers, The Beginning, and Gifts of the Magi. To see more of her beautifully-rendered work, please visit her website and Instagram page.

Words & pictures: The passages above are from Art & Fear: Observations on the Perils (and Rewards) of Art-making (The Image Continuum, 1993). All rights to the words and art in this post are reserved by the authors and artist.

A related post: "Embracing uncertainty."

Art, fear, and the value of uncertainty

Art-making is a magical process; but, as we discussed yesterday, it can also be a challenging one. In the journey from the start to the finish of a project there are problems to solve, questions to answers, errors in planning or technical execution to recognize and resolve, often with deadlines looming and the fearful possibility of failure. Making art requires vision and skill, but it also needs a great deal of faith. Faith in the project. Faith in yourself. And the courage (or stubborn tenacity) to keep on working through the bad days as well as the good.

In Art and Fear, David Bayles and Ted Orland address the perils and rewards of creative work, focusing on the things that hold us back and how to overcome them. What separates artists from ex-artists, they write,

"is that those who challenge their fears, continue; those who don't, quit. Each step in the art-making process puts the issue to the test.

"Fears arise when you look back, and they arise when you look ahead. If you're prone to disaster fantasies, you may even find yourself caught in the middle, staring at your half-finished canvas and fearing both that you lack the ability to finish it, and that no one will understand you if you do.

"More often, though, fears arise in those entirely appropriate (and frequently recurring) moments when vision races ahead of execution. Consider the story of the young student -- well, David Bayles, to be exact -- who began piano studies with a Master. After a few months' practice, David lamented to his teacher, 'But I can hear the music so much better in my head than I can get out of my fingers.'

"To which the Master replied, 'What makes you think that ever changes?'

That's why they're called Masters. When he raised David's discovery from an expression of self-doubt to a simple observation of reality, uncertainty became an asset. Lesson for the day: vision is always ahead of execution -- and it should be. Vision, uncertainty, knowledge of materials are inevitabilities that all artists must acknowledge and learn from: vision is always ahead of execution, knowledge of materials is your contact with reality, and uncertainty is a virue."

Materials, they say, are among the few elements of art-making you can hope to control; but for everything else,

"well, conditions are never perfect, sufficient knowledge rarely at hand, key evidence always missing, and support notoriously fickle. All that you do will inevitably be flavoured with uncertainty -- uncertainty about what you have to say, about whether the materials are right, about whether the piece should be long or short, indeed about whether you'll ever be satisfied with anything you make. Photographer Jerry Uelsmann once gave a slide lecture in which he showed every single image he had created in the span of one year: some hundred-odd pieces -- all but about then of which he judged insufficient and destroyed without ever exhibiting. Tolstoy, in the Age Before Typewriters, re-wrote War & Peace eight times and was still revising galley proofs as it finally rolled onto the press. William Kennedy gamely admitted that he wrote his own novel Legs eight times, and that 'seven times it came out no good. Six times it was especially no good. The seventh time out was pretty good, though it was way too long. My son was six years old by then and so was my novel and they were both about the same height.'

"It is, in short, the normal state of affairs. The truth is that the piece of art which seems so profoundly right in its finished state may earlier have been only inches or seconds away from total collapse. Lincoln doubted his capacity to express what needed to be said at Gettysburg, yet pushed ahead anyway, knowing he was doing the best he could to present the ideas he needed to share. It's always like that. Art is like beginning a sentence before you know its ending. The risks are obvious: you may never get to the end of the sentence at all -- or having got there, you may not have said anything. This is probably not a good idea in public speaking, but it's an excellent idea in making art.

"In making art you need to give yourself some room to respond authentically, both to your subject matter and to your materials. Art happens between you and something -- a subject, an idea, a technique -- and both you and that something need to be free to move. Many fiction writers, for instance, discover early on that making detailed plot outlines can be an exercise in futility; as actual writing progresses, characters increasingly take on a life of their own, sometimes to the point that the writer is as suprised as the eventual reader by what their creations say and do. Laurence Durrell likened the process to driving construction stakes in the ground: you plant a stake, run fifty yards ahead and plant another, and pretty soon you know which way the road will run. E.M. Forster recalled that when he began writing A Passage to India he knew that the Malabar Caves would play a central role in the novel, that something important would surely happen there -- it's just that he wasn't sure what it would be.

"Control, apparently, is not the answer. People who need certainty in their lives are less likely to make art that is risky, subversive, complicated, iffy, suggestive, or spontaneous. What's really needed is nothing more than a broad sense of what you are looking for, some strategy for how to find it, and an overriding willingness to embrace mistakes and surprises along the way. Simply put, making art is chancy -- it doesn't mix well with predictability. Uncertainty is the essential, inevitable and all-pervasive companion to your desire to make art. And tolerance for uncertainty is the prerequisite to succeeding."

The imagery today is by Sonja Danowski, an artist, author, and illustrator based in Berlin. Her picture books for children and adults include In the Garden, Puppet Theater, Smon Smon, Little Night Cat, Perfume Village, My Family, Mountain Goats, The Grass House, Forever Flowers, The Beginning, and Gifts of the Magi. To see more of her beautifully-rendered work, please visit her website and Instagram page.

Words & pictures: The passages above are from Art & Fear: Observations on the Perils (and Rewards) of Art-making (The Image Continuum, 1993). All rights to the words and art in this post are reserved by the authors and artist.

A related post: "Embracing uncertainty."

April 6, 2021

On art, wilderness, and losing the way

I always carry a book with me on my rambles through the hills with Tilly: not the same books that I read at home (nonfiction in the morning, fiction at night), but something I can read in daily increments on coffee breaks outdoors ... poetry perhaps, or volumes on art-making, or myth, or the natural world. The book in my tattered "walking bag" this week is Kent Nerburn's Dancing With the Gods: Reflections on Life and Art. I can't remember who recommended it; but whoever it was, I'm grateful. It's giving me a lot to think about.

The passage below, for example, discusses that part of the creative process when artists get stuck or lose their way -- which is precisely where I'm at with a certain section of The Moon Wife, my novel-in-progress. I know what ought to happen next, but a vital scene is refusing to unfold, threatening to carry me off in a new direction from the one I'd planned. Matching stubbornness to stubbornness, neither me nor the scene is giving way; and I know very well what I should do now, but I needed these words to remind me:

"No matter what your art form, there is a moment in almost every project when you feel that your work has got away from you. The character you are developing seems false. The story you are writing seems flat and uninteresting. All the choices you have made seem wrong-headed or misdirected and you can see no clear path forward. You are lost in a creative wilderness and you don't know how to escape.

"All of us have known these moments. They are part of the creative process. But that does not make them easier to endure. To feel a vision turn to dust in your hands is a painful experience, and he doubt that sets in is not subject to rational analysis. Is this the moment, you wonder, when my vision has left me? Is this the time when I took on too much, when I went at things from a wrong direction, when I overreached my own capabilities?"

There is no need for panic, writes Nerburn:

"As the French poet Anna de Noailles said, 'It's at midnight that one has to believe in the sun.' But even more, it is when you are in darkness that the moments of magic can happen because these are the moments when you are freed from the shackles of expectations and set free in the fields of creative recovery....

"I have had characters get away from me in writing, sending my plot in directions that made me despair of all my plans and expectations, only to find in the end that the characters, having wrested the story from me, moved it in directions that were at once richer and more complex than I had ever imagined. Every artist who has been working long enough to have had successes and failures can tell similar stories. It is the nature of creation for works to grow and take on lives of their own, often defying the artist's most cherished intentions.

"When this happens, you need to have confidence you are not lost; you are just on the point of new discovery. Your work has climbed out of the shape of your original idea and begun to claim a life of its own. Einstein put it well when he said, 'No worthy problem is ever solved within the plane of its original conception.' "

My husband Howard, working in theatre, often uses the term "the Dark Forest" to refer the time in the art-making process when the creation of a play (or story, or painting) reaches a crisis point: when the path disappears, the idea loses steam, the plot line tangles, that palette muddies, and you can see no way to move forward. This often occurs, just as Nerburn says, right before true magic happens: first there's the crisis, then a breakthrough, an unexpected solution, and the piece comes fully to life.

Howard kept a journal one year while directing a fairy tale play in Porto, Portugal; and somewhere around the middle of the project he wrote this:

"Today I arrived in the middle of the Dark Forest, and the path has almost disappeared. It is scary now, and all the certainties have gone. The cast members are weary, and their ability to come up with interesting work has diminished. Even our opening meditation today felt tired. The Dark Forest. I knew I was heading into it, and, as always, the Forest has its own way of manifesting in each creative project. Perhaps the actors are getting stuck, unable to develop their parts. Perhaps our storytelling has become a little flat, or maybe I'm forgetting important, simple things, like the clear development of the hero's character throughout the play....

"It's difficult to keep my original vision of the piece as I travel through the Dark Forest. I have to trust the vision I had at the start of the work, and that the ideas that have been set in motion will somehow come together. I know that I can't lose faith now, even though at this point in the creative process one often starts to question the show, the cast, and one's own ability.

"I can't turn around. I have to keep going, through this tough period, and find energy from somewhere! I'm reminded of the first day of the pilgrimage I took seven years ago, across the mountains of France and Spain to Santiago de Compostela. I cycled up route Napoleon late in the day, as the sun was setting, knowing that no matter how exhausted I was I had to push on to Roncesvalles. I could not turn back as I was too far along the path -- but if I did not get to the monastery before sundown, I would surely lose my way in the dark and cold; I could die of exposure lost in the Pyrenees. This is the feeling I have now: I'm exhausted, I don't know when the turning point will come, but I have to plough on."

I'm definitely lost in the Dark Forest of my novel. It's an uncomfortable place to be, but I'm not panicking. I know these woods. And after all these years of working with words, I do know what I need to do: Follow the story. Trust the story.

Head into the dark unknown and just plough on.

Words: The passage above is from Dancing With the Gods by Kent Nerburn (Canongate, 2018); all rights reserved by the author. A previous post on the book is here. The poem in the picture captions is from Sands of the Well by Denise Levertov (New Directions, 1996); all rights reserved by the Levetov estate. The poem goes out to all who are working on their own novels (or stories, or poems) today, the words "combining to make waves and ripples" in the great ocean of Story.

Pictures: The fairy tale drawings are by John D. Batten (1860-1932) and H.J. Ford (1860-1941).

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 710 followers