Terri Windling's Blog, page 17

April 28, 2021

Ordinary magic

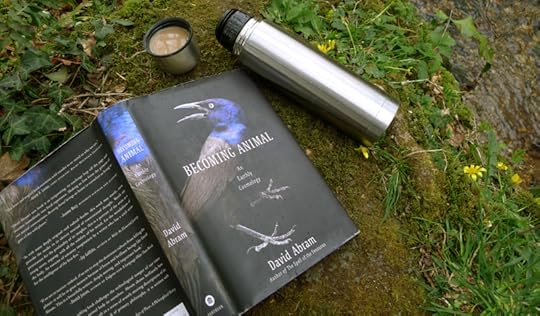

Following yesterday's post on magic and magicians, here's a passage from David Abram's second book, Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology. In this section of the text, he discusses a long journey through the Himalayas meeting with indigenous medicine workers and shamanic practioners -- sharing his own techniques of sleight-of-hand magic while listening, observing, and attuning himself to the local landscape:

"In the course of these first months in the Himalayas I came into contact with several jhankris of very diverse skill, and I lived for several weeks with two of them, a husband and wife who were both highly regarded as healers....The strangest thing about my time with Sonam and his wife, Jangmu, was how deeply I came home to myself during those days and nights. Rather than sampling alien practices and exploring beliefs entirely new to me, it was a quality of my own felt experience that became ever more fascinating, the carnal thickness underlying even my most ephemeral daydreams. From that first evening in their house, I found myself noticing ordinary, physical sensations much more vividly than I had realized was possible....Their home, with its stone walls, had a palpable density that hunkered close as I slept on the mud-caked floor across from Sonam and Jangmu, and when I woke in the morning I seemed to emerge from my private dreams into the wider dreaming of this breathing house nested within the broad imagination of the bouldered hillside.

"My hosts were already at work, whether feeding their few animals or hauling water back from the stream or consulting the spirits regarding the faltering crops of potatoes in a nearby village. Later I would be carrying fallen deadwood gathered from a stand of trees by the far below river, walking up the switchback trail behind Jangmu -- she seeming to float up the steep trail in her bare feet while her back was bent forward, its huge load slung from a single rope tumpline around her forehead, me straining and staggering in my hiking boots with a far smaller stash of fuel under my arms. I remember how completely those walks annihilated any separation of my conscious thoughts from my aching shoulders and my hammering heartbeat and the step and tumble of my legs.

"And herein was the strangeness: the more my consciousness sank into the muscled thickness of my animal flesh, the more I could feel the tangible earth around me swell and breathe and move within itself -- trees, riverbanks, and boulders quietly responding to all the happenings in their vicinity. It seemed the ground itself felt my footsteps and nudged my feet in the most serendipitous directions, ensuring that I'd come across some unexpected event at just the right moment -- that I'd encounter a hawk just as it swerved into a tree to feed its nestlings, or that I'd step into the precise spot to glimpse, through a momentary opening in the monsoon clouds, two mountain goats coupling on the high ridge. As though by dissolving my detached cognitions into the sensory curiosity of my body I had slipped into alignment with the sentience of the land itself. Awakening as this upright, wide-eyed, smooth-skinned thing, I noticed that all the other things around me were also awake.

"It was as profound an experience of magic as any I'd yet tasted, and yet it was entirely ordinary. There was nothing extraordinary about it, not in the least. It was not the encounter with a supernatural dimension that unfurls somewhere beyond my everyday, into which I might elevate myself now and then, but with a dimension always operative beneath my conventional consciousness, a carnal realm where my animal body was engaged in this ongoing interplay with the animate earth.

"Hence I began to feel far more palpably present, and real, to the rocks and shadowed cliffs than I'd felt before. I felt that I was known to these mountains now. This experience -- this awareness of my elemental, thingly presence to the tangible things that surrounded me -- has remained, for me, the purest hallmark of magic, the very signature of its uttermost reality. Magic doesn't sweep you away; it gathers you up into the body of the present moment so thoroughly that all your explanations fall away: the ordinary, in all its plain and simple outrageousness, begins to shine -- to become luminously, impossibly so. Every facet of the world is awake, and you within it.

"The deeper I slid into the material density of the real, the more I found that there was nothing determinate or predictable about existence. Actually, this inexhaustable mystery cannot be domesticated. It is wildness incarnate. Reality shapeshifts."

I highly recommend David Abram's books to those writers and storytellers seeking to invest their words, worlds, and characters with enchantment. He reminds us that magic is all around us in the world that we walk every day.

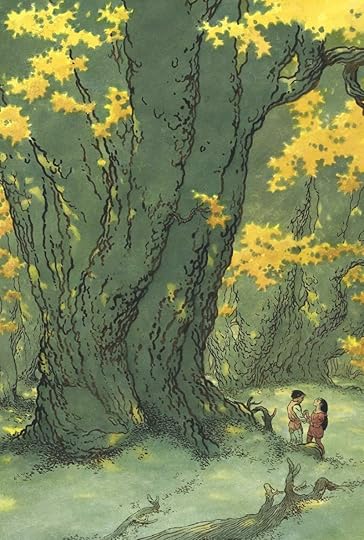

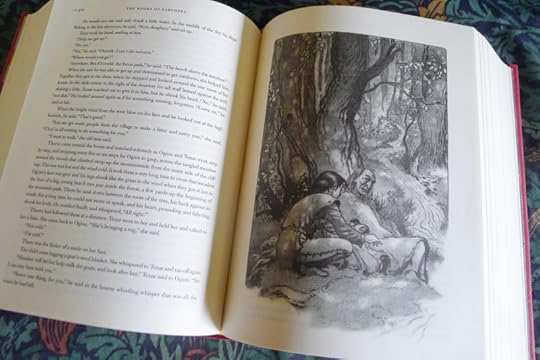

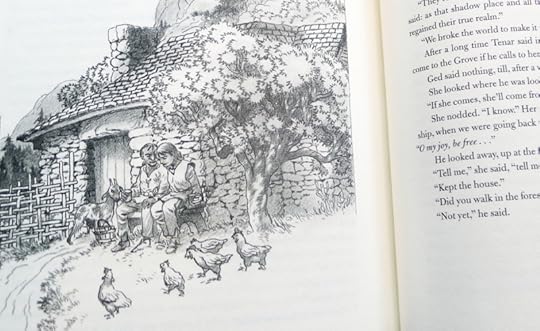

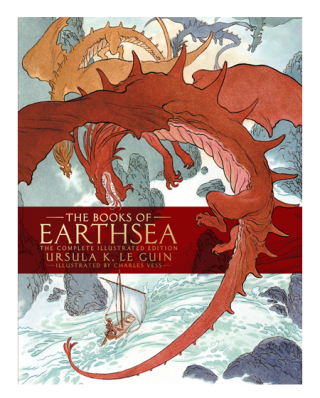

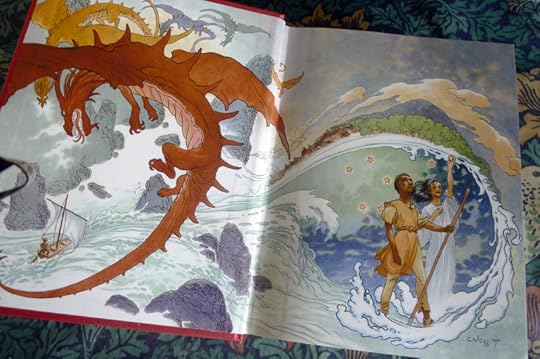

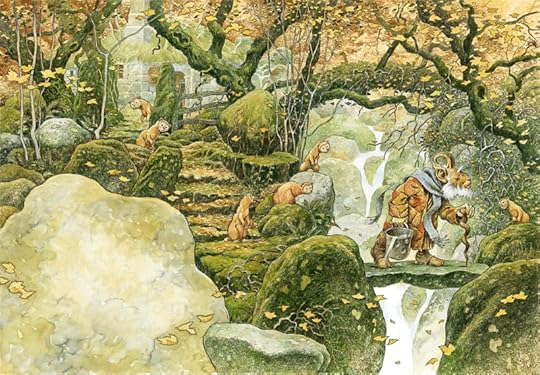

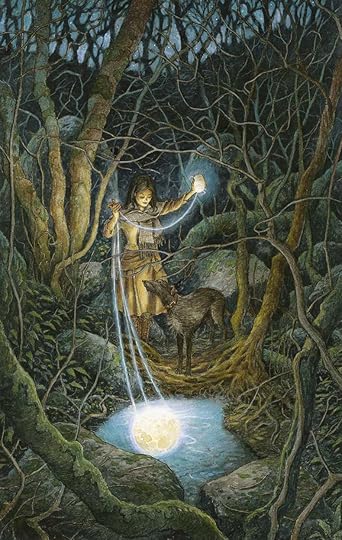

The art day is by Charles Vess, drawn from the magnificent body of work he created for The Books of Earthsea by Ursula K. Le Guin. Charles worked closely with Ursula over four years to create fifty-four illustrations faithful to her vision of the Earthsea archipelago and its denizens -- from wizards and dragons to farmers, sailors, temple-dwellers and kings. The result is a masterwork of mythic fiction and art, a perfect embodiment of word magic.

"I���d pretty much reconciled myself to drawing what she was looking at in her brain," Charles says. "I had no problem with that. She���s particularly brilliant. I really wanted to let her see the world that was in her mind....She envisioned Earthsea as a world mostly comprised of people of colour. It wasn���t just black people, but also Mediterranean or Native American people. All sorts of shades of brown. No one ever put that on a cover. She���d had a lot of fights about that. So, this was an opportunity to gird for battle -- to make the book look the way she���d always envisioned it."

Go here to learn more about the project, here to see some of the sketches made for it, and here to see more Charles' exquisite, unique, and visionary art.

Words & pictures: The passage quoted above is from Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology by David Abram (Pantheon, 2010). The Charles Vess illustrations are from The Books of Earthsea by Ursula K. Le Guin (Simon & Schuster, 20 ). All rights reserved by the author and artist.

April 27, 2021

Word magic

In his fine book The Spell of the Sensuous, David Abram discusses how being a sleight-of-hand magician gave him an entr��e into the world of traditional healers and shamans:

"I traveled to Indonesia on a research grant to study magic; more precisely, to study the relation between magic and medicine, first among the traditional sorcerers, or dukuns, of the Indonesian archipelago, and later among the djankris, the traditional shamans of Nepal. The grant had one unique aspect: I was to journey into rural Asia not outwardly as an anthropologist or academic researcher, but as an itinerant magician in my own right, in hopes of gaining a more direct access to the local sorcerers.

"I had been a professional sleight-of-hand magician for five years, helping to put myself through college by performing in clubs and restaurants throughout New England. I had, as well, taken a year off from my studies in the psychology of perception to travel as a street magician through Europe and, toward the end of that journey, had spent some months in London, working with R. D. Laing and his associates, exploring the potential of using sleight-of-hand magic in psycho-therapy as a means of engendering communication with distressed individuals largely unapproachable by clinical healers. As a result of this work I became interested in the relation, largely forgotten in the West, between folk medicine and magic.

"This interest eventually led to the aforementioned grant, and to my sojourn as a magician in rural Asia. There, my sleight-of-hand skills proved invaluable as a means of stirring the curiosity of the local shamans. Magicians, whether modern entertainers or indigenous, tribal sorcerers, work with the malleable texture of perception. When the local sorcerers gleaned that I had at least some rudimentary skill in altering the common field of perception, I was invited into their homes, asked to share secrets with them, and eventually encouraged, even urged, to participate in various rituals and ceremonies.

"But the focus of my research gradually shifted from a concern with the application of magical techniques in medicine and ritual curing, toward a deeper pondering of the traditional relation between magic and the natural world."

Scott London goes deeper into this aspect of David's work in the following passages from his illuminating intervew, "The Ecology of Magic":

London: You have used the phrase "boundary keeper" to describe the magician. What do you mean by that?

Abram: I discovered that very few of the medicine people that I met considered their work as healers to be their primary role or function for their communities. So even though they were the healers, or the medicine people, for their villages, they saw their ability to heal as a by-product of their more primary work. This more primary work had to do with the fact that these magicians rarely live at the middle of their communities or in the heart of the village. They always live out at the edge or just outside of the village -- out among the rice paddies or in a cluster of wild boulders -- because their skills are not encompassed within the human modality. They are, as it were, the intermediaries between the human community and the more-than-human community -- the animals, the plants, the trees, even whole forests are considered to be living, intelligent forces. Even the winds and the weather patterns are seen as living beings. Everything is animate. Everything moves. It's just that some things move slower than other things, like the mountains or the ground itself. But everything has its movement, has its life. And the magicians were precisely those individuals who were most susceptible to the solicitations of these other-than-human shapes. It was the magicians who could most easily enter into some kind of rapport with another being, like an oak tree, or with a frog.

London: What sort of rapport?

Abram: Every magician that I met had a number of animals or plants or forms of nature that were their close familiars. Just as we speak of the witch's black cat as her "familiar," so in these animistic societies the magician might have crows and frogs and perhaps a certain kind of rubber plant as his familiars. It might also be a certain kind of storm -- a thunder-storm -- a being that, when it appeared in the sky, would tell the magician that it was time to go outside and just gaze at those clouds and learn from them what they might have to teach.

London: In the same way, perhaps, that horses can sense an impending earthquake.

Abram: Right. Other animals function for the magician as another set of senses, another angle from which he can see and hear and sense what's going on in the surrounding ecology, because we are limited by our human senses, our nervous-system, and our two arms and our two legs. Birds know so much more about what's going on in the air, in the invisible winds, than we humans can know. If we watch the birds closely, we can begin to learn about what's going on in the sky and in the air simply by watching their flight patterns.

London: Where do they draw the boundary between magic and reality?

Abram: That boundary is not drawn in traditional cultures. In indigenous, tribal, or oral cultures, magic is the way of the world. There is nothing that is not in some way magic, because the fact that the world exists is already quite a wonder. That it stays existing, that it continually keeps holding itself in existence, this is the mystery of mysteries. Magic is the way of the world. It's that sense of being in contact with so many other shapes of awareness, most of which are so different from our own, that is the basic experience of magic from which all other forms of magic derive.

London: What happens to a culture bereft of magic?

Abram: One thing is that its relation to the natural landscape is tremendously impoverished. In fact, by our obliviousness, by our forgetfulness of all of these other styles of awareness -- the other animals, the plants, the waters -- we have brought about a crisis in the natural world of unprecedented proportions -- not out of any meanness, but simply because we really don't recognize that nature is there. It seems to us, in our culture, to be a kind of passive backdrop against which all of our human events unfold, and it's human events that are meaningful and what happens in nature, well, we don't really notice it, it's not really there. It's not vital. How different that is from the awareness of a magical or animistic culture for whom everything we do as humans is so profoundly influenced by our interactions with the earth underfoot and the air that swirls around us and the other animals.

London: You said that some field biologists are able to capture the essence of magic in their work. I can think of some nature writers who also serve that same function -- people like Peter Mathiessen, Terry Tempest Williams, and Barry Lopez.

Abram: Absolutely. I do think that some of the nature writers are doing an exquisitely important work of magic. They are doing what we might think of as "word magic" -- very carefully taking up the language and trying to use it in new ways, trying to work out how to speak without violating our kinship with the rest of the animate earth.

I agree with David on this, but I would add that there are fantasy writers, storytellers, and mythic artists who are doing the important work of "word magic" too.

Words: The first passage quoted above is from The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-Than-Human World (Vintage, 1997). Scott London's interview appears on London's website here, adapted from the public radio series "Insight & Outlook." All rights reserved by Abram and London. I highly recommend David's two books, pictured above, if you haven't read them already. Both have been influential texts for me over the years.

Pictures: The two ink drawings are by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939). The photographs capture a Dartmoor pony encounter that Tilly and I had earlier this spring. We sat together on old stone wall watching them drift by, one by one. The last pony stopped in front of us, resting her head on my outstretched hand; then she turned and followed the others up the hill. It felt like a blessing.

April 26, 2021

Tunes for a Monday Morning

Above: "Awake Awake," a traditional song performed by English singer/songwriter Maz O'Connor, from her album This Willowed Light (2014). The animation is by Marry Waterson.

Below: "All on a Summer's Evening" by Scottish singer/songwriter Karine Polwart, with sound designer Pippa Murphy, from their stage show and album A Pocket of Wind Resistence (2017). The animation is by Marry Waterson.

Above: "Birds of Passage" by the Scottish folk band Breabach, from their album Frenzy of the Meeting (2018). The animation is by Cat Bruce.

Below: "Pegasi" by American singer/songwriter Jesca Hoop, from her album Memories Are Now (2017). The animation is by Rachel Blumberg.

Above: "In Painter's Light" by Irish singer/songwriter Declan O'Rourke, from his album Arrivals (2020). The animation is by Toby Mortimer.

Below: "Easier" by English folk duo Faeland (Rebecca Nelson and Jacob Morrison), from their album Little Lights (2020). The animation is by Sofja Umarik.

Above: "Buried in Ivy" by English folk duo Honey and the Bear (Lucy and Jon Hart), with Graham Coe, Evan Carson, and Toby Shaer; from their beautiful new album Journey Through the Roke (2021). The animation is by Honey and the Bear.

Photography by Melissa Nolan and Andy Rouse; all rights reserved by the photographers.

April 23, 2021

The Tree Tribe

The thing you need to know, child, is that trees do speak, they do tell tales, they sing when the've a mind to, they are gigglers, gossips, grumblers, cataloguing every ache and pain, and yet they hold no grudges, claim no debts, speak ill of no creature. They have their tempers, yes, tantrums of branches lashed in gusts and gales, but then they come to rest in stillness, spent, humming contentedly. You've heard them, just yesterday. You thought it was only the wind.

The thing you need to know is that each morning every tree stands tall and chants its name, its history, its kinship web and lineage. You've heard them, dear, but thought it was the dawn chorus of birds.

The thing you need to know is that the trees tell stories older than the oldest tales of humankind. By dusk, by night, by starlight, you have marked their midnight murmuring -- you told me so, but thought it was just water rushing through the stream.

The thing you need to know, child, is that trees do speak, in their own language. They mutter in the crackle autumn leaves; they sigh as snow settles at their feet; they utter exquisite arboreal poems as each tender young leaf unfurls; they laugh in shivers of green and gold when tickled by a summer's breeze.

The thing you need to know, child, is that trees do speak, in the tree language. And yes, you will understand their speech one day, root child, sweet sapling.

The beautiful drawings today are by British artist Celia de Serra, who was born in Canterbury in 1973, received a BA in Fine Art and English Literature from Exeter University in 1995, and now exhibits her work extensively throughout the UK. De Serra is a founding member of The Arborealists, a group of contemporary artists dedicated to the subject of trees. Her art has appeared in Under the Greenwood: Picturing the British Tree and other publications.

"I live in the Welsh borders in the hills near Offa���s Dyke," she writes. "I spend a lot of time out and about walking and cycling armed with a Ordinance Survey Map, sketchbook and camera. I look for inspiring places and images that have something about them and an emotional hook. Light is particularly important to me -- the way in which it can transform something small, or illuminate a place in a curious or dramatic way. Always a painter, I returned to drawing several years ago and this has become my primary medium at the moment; I love the directness of drawing, the marks, the tonal variations and the capacity to build up layers and depth without the confusion that colour can sometimes bring to form."

To see more of de Serra's work, visit her website, her Instagram page, and The Arborealists site.

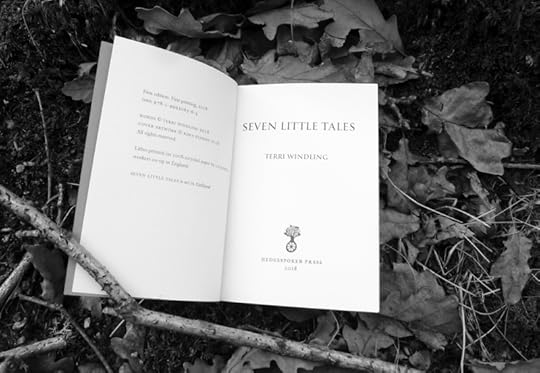

Words: "The Tree Tribe" is one of seven little pieces of mine published in Seven Little Tales (Hedgespoken Press, 2018).

Pictures: The drawings above are: Borderlands, River Valley, Summer Nights, Towards This Place Lightly, Still There, Still Here Too, West Borders, and Flux by Celia de Serra. All rights reserved by the artist.

April 22, 2021

On language and mystery

From "Learning the Grammar of Animacy" by Potawatomi author, educator, and biologist Robin Wall Kimmerer:

"I come here to listen, to nestle in the curve of roots, in a soft hollow of pine needles. To lean my bones against the column of white pine, to turn off the voice in my head until I can hear the voices outside of it. The shhh of wind in the needles. Water trickling over rock, nuthatch tapping, chipmunks digging, beechnut falling, mosquito in my ear and something more, something that is not me, for which we have no language, the wordless being of others in which we are never alone. After the drumbeat of my mother's heart, this was my first language.

"I could spend a whole day listening. And a whole night. And in the morning, without my hearing it, there might be a mushroom that was not there the night before, creamy white, pushed up from the pine needle duff, out of darkness to light, still glistening with the fluid of its passage. Puhpowee.

"Listening in wild places, we witness conversation in a language that is not our own. I think now, that it was a longing to comprehend this language I hear in the woods that led me to science, to learn over the years to speak fluent Botany. Which should not, by the way, be mistaken for the language of plants. In science I did learn another language, of careful observation, an intimate vocabulary that names each little part. To name and describe you must first see, and science polishes the gift of seeing. Science is a beautiful language, rich in particulars, revealing the intricate mechanisms of the world. I honor the strength of that language which has become a second tongue to me. But, beneath the richness of its vocabulary, its descriptive power, something feels missing, the same something that swells around you and in you, when you listen to the world. The pattern of its surface hides an empty center, like a gorgeous tapestry over a scarred wall. Science is a language of distance which reduces a being to its working parts, the language of objects. The language we speak, however precise, is based on a profound error in grammar, which seems to me now, a grave loss in translation from the native languages of these shores.

"My first taste of the missing language was the word puhpowee, on my tongue. I stumbled upon it in a book by Anishnaabe ethnobotanist Keewaydinoquay, a treatise on the traditional uses of fungi by our people. Puhpowee, she explained, translates as 'the forces that causes mushrooms to to push up from the earth overnight.' As a biologist, I was stunned that such a word existed. In all its technical vocabulary, Western science has no such term, no words to hold this mystery. You'd think that biologists, of all people, would have words for life. But, I think in scientific language, our terminology is used to define the boundaries of our knowing. That which lies beyond our grasp remains unnamed. In the three syllables I could see an entire process of close observation in the damp morning woods, of the mystery of their coming, the formulation of a theory for which English has no equivalent. The makers of this word understood a world of being, full of unseen energies which animate the world. I've cherished that word for many years, a talisman, and longed for the people who gave a name to the life force of mushrooms. The language that holds puhpowee is one that I wanted to speak. The word for rising, for emergence, became a signpost for me, when I learned that it belonged to the language of my ancestors."

I recommend reading Kimmerer's essay in full, first published in The Leopold Outlook magazine (Winter 2012) and available online here. These ideas were developed further in her remarkable book Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants (discussed on Myth & Moor here) -- and also in a number of talks and essays such as "Speaking of Nature" (discussed on Myth & Moor here.)

I believe Kimmerer's work has relevance to those of us working in fantasy and mythic arts, for we, too, must learn to speak a language suited to describing Mystery: a language woven from myth, folklore, symbolism, poetry and dream. The fantasist's world is an animate world, shimmering with unseen energies. The grammar and gramarye of its language is every mythic artist's birthright, for the world of Story welcomes us all. It's a tongue that any of us can learn. Enter the forest, or the tale, and listen....

The imagery today is by Alexandra Dvornikova, a contemporary folk artist and illustrator from Saint Petersburg, Russia. She studied print-making, graphics, and art therapy at Saint Petersburg Stieglitz State Academy of Art and Design, and now creates books, cards and prints, fabric designs, animations, and more. She finds inspiration in the Russian fairy tales she heard as a child, as well as masks, music, ritual, nature and ecology, the folklore of animals, mosses and mushrooms, venomous plants, and lonely cabins deep in the woods. To see more of her art, please visit Dvornikova's website and Instagram page.

Words: The passage quoted above is from "The Grammar of Animacy" by Robin Wall Kimmerer (The Leopold Outlook magazine, Winter 2012). all rights reserved by the author.

Related posts: For another look at the language of science contrasted to the language of Story, go here. Other posts on the interesection of science and art are archived here.

Pictures: The paintings by Alexandra Dvornikova are Forest, Fungi, Mushroom Pattern, Lost Land, Forest Treasures, Fire Fox, Mushroom Dress, Mushroom Hat, Mushroom Bed, and Magic. All rights reserved by the artist. Dvornikova's work also appeared in a previous Myth & Moor post: Stepping into story.

April 21, 2021

The magic of words

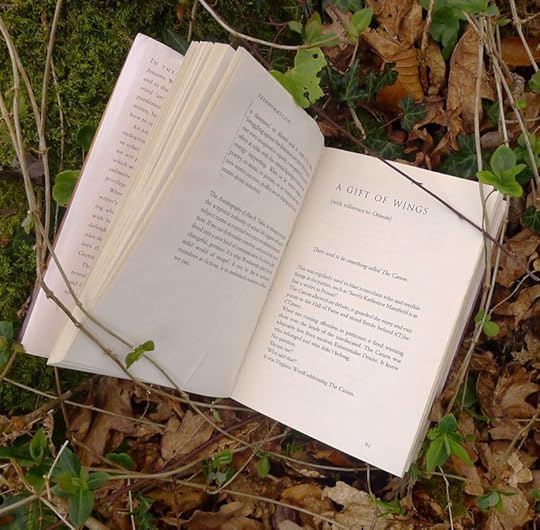

In her essay "A Gift of Wings," Jeanette Winterson gets to the core of what makes Virginia Woolf's work so compelling, and in doing so she evokes the magic inherent in the arts of writing and reading themselves:

"Unlike many novelists, then and now, she loved words. That is she was devoted to words, faithful to words, romantically attached to words, desirous of words. She was territory and words occupied her. She was night-time and words were the dream.

"The dream quality, which is a poetic quality, is not vague. For the common man it is the dream, if at all, that binds together in a new rationale, disparate elements. The job of the poet is to let the binding happen in daylight, to happen to the conscious mind, to delight and disturb the reader when the habitual pieces are put together in a new way.

"Above all, credulity is not strained. We should not come out of a book as we do from a dream, shaking our heads and rubbing our eyes and saying, 'It didn't really happen.' In poetry, in drama, in opera, in painting, in the best fiction, it really does happen, and is happening all the time, this other place where, as strong and compelling as our own daily world, as believable, and yet with a very strangeness that prompts us to recall that there are more things in heaven and earth and that those things are solider than dreams.

"They may prove solider than real life, as we fondly call the jumble of accidents, characters and indecisions that collect around us without our noticing. The novelist notices, tries to make us clearer to ourselves, tries to set the liquid day, and because of this we read novels. We do hope to see ourselves, as much out of vanity as for instruction. Nothing wrong with that but there is further to go and it is this further than only poetry can take us. Like the novelist, the poet notices, focuses, sharpens, but for the poet that is the beginning. The poet will not be satisfied with recording, the poet will have to transform. It is language, magic wand, cast of spells, that makes transformation possible."

The poet does this, yes, and the poetic fiction writer, and especially, I believe, the poets and fiction writers working in fantasy and mythic arts. Casting spells with language and telling tales of transformation are, after all, the very point of this alchemical genre in which elements of poetry, prose, myth, fairy tale, and dream are carefully combined, turning lead, and straw, and language, and life itself into pure gold.

As Ursula Le Guin said in her essay "From Elfland to Poughkeepsie" (in a passage I quote often, because it's just so true):

"Fantasy is a different approach to reality, an alternative technique for apprehending and coping with existence. It is not antirational, but pararational; not realistic but surrealistic, a heightening of reality. In Freud's terminology, it employs primary, not secondary process thinking. It employs archetypes, which, as Jung warned us, are dangerous things. Fantasy is nearer to poetry, to mysticism, and to insanity than naturalistic fiction is. It is a wilderness, and those who go there should not feel too safe. And their guides, the writers of fantasy, should take their responsibilities seriously....

"A fantasy is a journey. It is a journey into the subconscious mind, just as psychoanalysis is. Like pyschoanalysis, it can be dangerous; and it will change you."

Powerful word magic indeed.

Returning to the essay "A Gift of Wings," Winterson describes Virginia Woolf as a writer who "is not afraid of beauty. She is as sensitive to the natural world as any poet and as physical in response as any lover. She is not afraid of pain. The dark places attract her as well as the light and she has the wisdom to know that not all dark places need light. She has the cardinal virtue of critical courage."

That, I believe, is what we, too, must strive for. The love of words shared by all good writers and all good readers is the magic that will show us how.

Winterson's essay can be found in her collection Art Objects (Jonathan Cape, 1995), Le Guin's in her collection The Language of the Night (The Women's Press, 1979). All rights reserved by the authors. Photographs: Words in the wild.

April 20, 2021

Telling stories

In "Hallowed Ground," Chelsea Steinauer-Scudder discusses the importance of myth and story in countering the narratives that foster the ecological destruction of our world. Steinauer-Scudder's essay is focused on the work of theologian Martin Palmer, exploring how the sacred stories of world religion can change the world for the better (or worse) -- but secular stories are powerful too. As storytellers, myth-makers and artists of all stripes, what kind of narratives are we creating? And are we cognizant of their potency? Steinauer-Scudder writes:

"There are Theravada Buddhist monks in Thailand who follow the Buddha���s example of meditating in natural settings, particularly beneath trees; they have a practice of going into the forest during the rainy season of Phansa and building small huts, where they remain for several months to meditate. Traditionally, when the huts appeared, it was understood that human beings were not to disturb or damage the surrounding forest; it became an extension of the monks��� prayers and practice: sacred land.

"Thailand and Cambodia have seen some of the most devastating logging and clear-cutting in a world where 18.7 million acres of forest across the globe are lost to deforestation annually. Between 1961 and 1998, an estimated two-thirds of Thailand���s remaining forest was destroyed. In the 1980s, the logging effort increased and entire forests began to disappear, sometimes in the course of a single day.

"In 1988 the excessive deforestation of a mountainside led to a landslide, exacerbating floods and killing over three hundred people. The monks saw the land suffering and the people suffering as a result. A small number of monks began to reexamine Buddhist scriptures, seeking ways to protect the forests through traditional rituals and teachings. The Buddha taught that all things are interconnected, that the health of the whole is bound to the health of every sentient being. If you harm rivers, trees, animals, soil, you harm yourself. Some of the monks began to intentionally seek out threatened and illegally logged forests for their Phansa meditation, but it became increasingly dangerous for them. Some were assassinated.

"And then one monk began a practice of ordaining trees. After locating the oldest and largest trees in a forest, he -- in the presence of members of his surrounding lay community -- recited the appropriate scripture and then wrapped the trees in traditional orange robes, just as is done for a novice monk. The practice has spread across Thailand and into Cambodia. Most loggers will not commit the taboo of harming a monk, even if that monk is a tree.

" 'We are a narrative species. The faiths are successful because they tell bloody good stories and they adapt them as they go along,' Martin is telling me over a coffee break in Bristol. 'So all across Southeast Asia, there are these trees that have been ordained as monks, and that means that within a sort of half-mile penumbra of that, it���s sacred. There���s no way a Cambodian or a Thai is going to cut down a monk tree.' ARC has worked with monks in Thailand and Cambodia to set up environmental-education centers, trainings, and awareness campaigns. It helped to found ABE, the Association of Buddhists for the Environment, a network of monks and nuns grounded in Buddhist teachings and traditions. 'It���s been very local, very specific [work]. And most of it is built on the fact that, whatever else is gone, a sense that a sacred place is something other still remains.'

"It���s this sense of place and the stories that go along with it, Martin says, that can become catalysts for change. When it comes to addressing ecological degradation and potential collapse, most of us have not been telling the right ones. A transformative story, when told at the right time in the right place, has the ability to alter the course of things. 'There���s only two things that have ever done that successfully in history: art and religion. And for most of history, they���ve been synonymous,' Martin says. ARC works with Jains in India, Shint��ists in Japan, Taoists in China, Jews, Muslims, Zoroastrians���operating on the belief that religion has consistently told humanity���s most enduring stories, that parable can be more effective than science, that myths are more powerful than data.

"As we wend our way through the city, I���m beginning to picture Martin as a real-life, intellectual version of Roald Dahl���s BFG: a lanky, well-intentioned giant who roams the globe, but instead of collecting dreams and delivering them to sleeping children, he is collecting stories. Fables and myths, parables and songs. His life���s work has been to pull forward or uncover narratives from traditions and texts, and support local faith communities in doing the same."

Later in the piece, Steinauer-Scudder adds a note of caution:

"To seek and reveal stories on behalf of others is, in many ways, a fraught strategy; it can carry the odor of imposition when it comes from outside a local culture. But in a time when perhaps the most imposing and pervasive story of all -- consumerism -- is driving species to extinction, deforesting lands, fueling wildfires in the American West, and depleting topsoil and the oceans, one wonders how we can help one another to turn our attention and efforts to different ends. How can we remember that stories, too, have agency? ARC, as an organization, is international, but its lifeblood is comprised of communities around the world, each facing their own version of environmental crisis, each working within the narratives and traditions that have shaped its landscapes and identities. Such stories cannot be arbitrarily deposited. In order to thrive, they need fertile soil, a caring hand, relationship, understanding, shared history. When the conditions are right, they can root themselves or unfurl a new leaf.

���'[Religion is] not the silver bullet,' Martin says. It certainly should not be left to faith communities alone to cultivate the stories that might begin to heal a world in crisis, environmentally and spiritually. But he does believe that religion holds our most enduring stories, told again and again throughout the ages, even when humanity sometimes uses them to destructive ends. Secular communities can look to the faiths as examples of what it means to embody powerful narratives. Religious or no, we can find new ways to tell ancient stories. New language to bring people back to an ancient understanding.

" 'Human beings are capable of extraordinary change if given the space to do it,' says Martin. 'Not by fear, and not by data. But by story.'���

I highly recommend reading Chelsea Steinauer-Scudder's "Hallowed Ground" in full in Emergence Magazine. You'll find it here. The wondrous art today is by our good friend David Wyatt, a great lover of trees and stories. To learn more about his work, go here.

Words: The two passages above are quoted from "Hallowed Ground" by Chelsea Steinauer-Scudder, published in Emergence Magazine (January 15, 2019); all rights reserved by the author. Emergence, by the way, is terrific, if you're not reading it already.

Pictures: The paintings above are Winter Beech, Gidleigh Goat, Fetching Water, Acorn, and Spinning Moonlit by David Wyatt; all rights reserved by the artist.

April 19, 2021

Tunes for a Monday Morning

I haven't been to the Devon coast since the pandemic began and I'm truly missing the sea these days. Let's start the week with some magical music of the sea and shore....

Above: Scottish singer Shiobhan Miller peforms "Selkie," a tradition Orcadian ballad about a human woman who loves a man of the seal people. Miller's beautiful rendition of the song appears on her equally beautiful new album, All is Not Forgotten (2020).

Below: Scottish singer Julie Fowlis performs "��ran an R��in/The Song of the Seal," a traditional Gaelic ballad from the Hebrides. Selkies, she explains, are "creatures who moved between the parallel worlds of sea and land, but never truly belonging to either. " This haunting version of the song was recorded last May, with video footage by Mike Guest.

Above: "Swirling Eddies," a selkie song by musician and music scholar Fay Hield, based in Sheffield -- from her mythical, magical new album Wrackline (2020). While working on this piece, she says,

"I imagined what it would be like to fall in love with the world above water. How it would feel to leave your selkie family, traditions and life in the sea, to be lured onto land. What would it take to make that irresistible leap, to turn your back and step into a new adventure? In a lot of the stories a human steals their skin so they are forced into marriage. In this instance, I wanted to selkie to be intrigued by the human world, to want to come and enter into this new way of being. Exploring the seduction and lure of the ���other���. This includes the male suitor, but places him to one side, focusing more on the world that opens up. The words and tune for ���Swirling Eddies��� came together...through singing over and over, round and round, like the waves going in and out. I wanted the tune to seem dizzying, as she would be in the dancing, and light-headedness of moving into a new environment, feeling airless, or rather, I suppose, waterless."

Below: "Stone's Throw: Lament of the Selkie" by Rachel Taylor-Beales, a musician and activist based in Wales. The song appeared on her poignant album of the same name (2015), which was subsequently turned into a theatre piece. She says:

"I���d been exploring the character and persona of Selkie, a shape-shifting seal woman re-imagined from Orkney folklore, struggling to live her life on land away from her natural habitat of the ocean. Selkie���s internal turbulence seemed to echo the real-life struggles of people in the news headlines, and that I'd met personally: stories of refugees and displaced people, far from home, with all the loneliness and chaos, grief and loss that comes with enforced migration. In the legends, in order to marry a Selkie woman, her sealskin has to be captured while she is in human form and kept hidden from her so she can't go back to sea. The woman of the legends -- taken out of her natural environment, longing for home, misunderstood by those around her who know nothing of her former life -- became synonymous in my mind with the stories of refugees. The video was filmed by my husband Bill Taylor-Beales, and features Isla Horton, who achingly portrays a displaced mother separated from home and family."

Above: "Black Seas" by the London-based iyatra Quartet (Alice Barron, Richard Phillips, Will Roberts, and George Sleightholme). The song is from their album Break the Dawn (2020). The video was filmed by Andrew Spicer.

Below: "Avalon" by Rhiannon Giddens (from North Carolina), with Italian multi-instrumentalist Francesco Turrisi, from their new album They're Calling Me Home (2021). The video, directed by Laura Sheeran, was filmed in Co. Galway, Ireland. The dancers (and choreographers) are Stephanie Dufresne and Mintesinot Wolde.

Selkie painting above: "Messenger of the Water" by my friend and neighbour Danielle Barlow. You can see more of her beautiful work on her website or Instagram page. All rights reserved by the artist. Photograph: On the south Devon coast with Tilly during betters days.

April 17, 2021

How to begin

"The advice I like to give young artists," says painter Chuck Close, "or really anybody who'll listen to me, is not to wait around for inspiration. Inspiration is for amateurs; the rest of us just show up and get to work. If you wait around for the clouds to part and a bolt of lightning to strike you in the brain, you are not going to make an awful lot of work. All the best ideas come out of the process; they come out of the work itself. Things occur to you. If you're sitting around trying to dream up a great art idea, you can sit there a long time before anything happens. But if you just get to work, something will occur to you and something else will occur to you and something else that you reject will push you in another direction. Inspiration is absolutely unnecessary and somehow deceptive. You feel like you need this great idea before you can get down to work, and I find that's almost never the case."

Likewise, novelist Ann Patchett reminds us that in order to write we need to cross the line between thinking about creating and getting down to work. "The journey from the head to the hand is perilous and lined with bodies," she warns. "It is the road on which nearly everyone who wants to write -- and many of the people who do write -- get lost."

Sometimes we put off the moment of actually beginning, getting stuck in the dreaming and planning stage instead -- afraid to start, afraid to commit, afraid to go where the creative process wants to take us. Yet despite fear and doubt, wrote Rollo May in The Courage to Create, we must make the leap, plunge in, begin. "The relationship between commitment and doubt is by no means an antagonistic one," he points out. "Commitment is healthiest when it is not without doubt, but in spite of doubt."

Beginnings are rarely tidy and controlled...nor are they particularly meant to be.

"For me," says Ramona Ausubel, "the first draft is really just a big mud-rolling, dust-kicking, mess-making time in which my only job is to find the story���s heartbeat. I allow myself to invent characters without warning, drop them if they prove to be uninteresting, change the setting in the middle, experiment with point of view, etc. I figure that the body will grow up around the heart, that it���s always possible to bring all the various  elements up and down, sculpt and polish, as long as I���ve got something that matters to me. The second draft (and the third through twentieth, Lord help me) involves getting out the tool belt and thinking like a carpenter. But the first draft is all dirt and water and seeds and, hopefully, a little magic. Of course, this method means that my first draft is almost unreadable. Maybe someday I���ll invent a way of making a slightly cleaner mess, but until then, I try to enjoy the muck."

elements up and down, sculpt and polish, as long as I���ve got something that matters to me. The second draft (and the third through twentieth, Lord help me) involves getting out the tool belt and thinking like a carpenter. But the first draft is all dirt and water and seeds and, hopefully, a little magic. Of course, this method means that my first draft is almost unreadable. Maybe someday I���ll invent a way of making a slightly cleaner mess, but until then, I try to enjoy the muck."

So get it down, those messy first drafts and rough initial sketches, get it down, don't judge, don't polish, don't freeze, don't get stuck endlessly rewriting the first clutch of pages over and over, never progressing any further (a habit I'm all too prone to myself) -- you can edit, fix, fill out, perfect, and pretty it all up later.

"Don't get it right," said the great James Thurber, "just get it written."

Although we've been speaking specifically of painting and writing, the crucial moment of "beginning" is important in all forms of creativity -- and each of us is an artist, a maker, in some aspect of our lives. We make homes and gardens, classrooms and sanctuaries, families and communities; we create meals and letters and blogs and adventures lodged in our children's memories; and we all have things we want and plan to do "someday" that we really ought to just begin.

This quote from Scottish mountaineer William Hutchison Murray (often erroneously attributed to Goethe) is a good one to remember when we stand wavering at the edge of a new project:

"Until one is committed there is hesitancy, the chance to draw back, always ineffectiveness. Concerning all acts of initiative or creation, there is one elementary truth...that the moment one definitely commits oneself, then Providence moves too. All sorts of things occur to help that would otherwise never have occurred. A whole stream of events issues from the decision, all manner of incidents and meetings and material assistance which no man would have believed would have come his way.

"Whatever you think you can do or believe you can do, begin it. Action has magic, grace, and power in it."

It does. As makers, we must trust that magic. Which, of course, means trusting ourselves.

To read more on the process of starting creative work (and on dealing with problem of procrastination), see this previous Myth & Moor post: The rituals of approach.

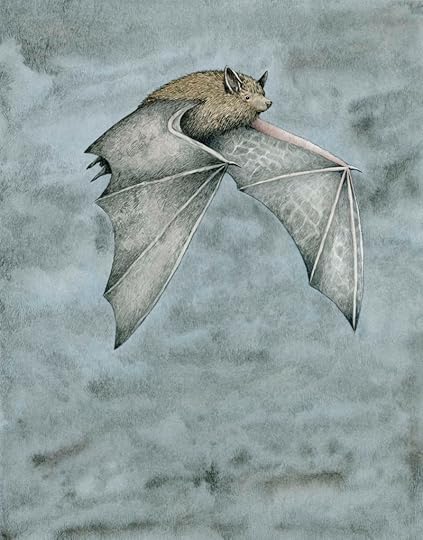

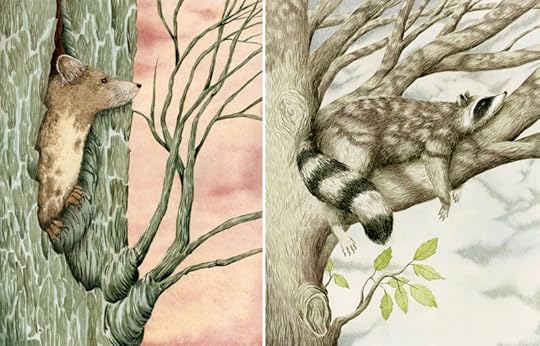

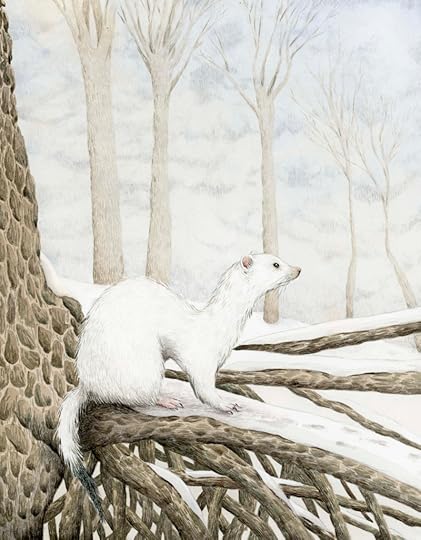

The charming artwork today is by Marieke Nelissen, an illustrator who hails from the Netherlands -- though having lived in Mexico and Costa  Rica as a child, her influences come from a vibrant mix of cultures.

Rica as a child, her influences come from a vibrant mix of cultures.

Nilissen has been drawing animals since she was young, creating fantastical figures and fabulous beasts as well as precise studies from nature. After studying illustrative design in 's-Hertogenbosch, she spent ten years working at a small graphic arts agency before becoming a freelance designer and book illustrator. Her extensive list of publications includes The Prince's Desire, The Wizard of Oz, Stories from De Heksenkeet, The Waterwaacke of Natterlande, Seven Ways to Fall Asleep, The House of Sinterklass, Yokki and the Parno Gry, The Monsterbonsterbulderboek, The Unicorn & Other Fantastic Animals, and Beastly Neighbours.

To see more of her work, visit Nelissen's Le Petit Studio or her Instagram page. You can also find an interview with the artist here, on Cornelia Funke's website.

All rights to the text and art above reserved by the authors and the artist. The final quote, often misattributed, is from The Scottish Himalayan Expedition by W.H. Murray (1951); the last lines paraphrase a couplet of Goethe's.

April 16, 2021

Rituals of beginning

Here are more wise words on the practice of art from The Creative Habit by Twyla Tharp:

"A lot of habitually creative people have preparation rituals linked to linked to the setting in which they choose to start their day. By putting themselves into that environment, they start their creative day. The composer Igor Stravinsky did the same thing every morning when he entered his studio to work: He sat at the piano and played a Bach fugue. Perhaps he needed the ritual to feel like a musician, or the playing somehow connected him to musical notes, his vocabulary. Perhaps he was honoring his hero, Bach, and seeking his blessing for the day. Perhaps it was nothing more than a simple method to get his fingers moving, his motor running, his mind thinking music. But repeating the routine each day in the studio induced some click that got him started.

"I know a chef who begins each day in the meticulously tended urban garden that dominates the tiny terrace of his Brooklyn home. He is obsessed with fresh ingredients, particularly herbs, spices, and flowers. Spending the first minutes of the day among his plants is his ideal creative environment for thinking about new flavor combinations and dishes. He putters about, feeling connected to nature, and this gets him going. Once he picks a vegetable or herb, he can't sit there. He has to head off to the restaurant and start cooking.

"A painter friend I know can't do anything in her studio without propulsive music pounding out of the speakers. Turning it on turns on a switch inside her. The beat gets into a groove. It's the metronome for her creative life.

"A writer friend can only write outside. He can't stand the thought of being chained indoors to his word processor while a 'great day' is unfolding outside. He fears he's missing something stirring in the air. So he lives in Southern California and carries his coffee mug out to work in the warmth of an open porch in his back yard. Mystically, he now believes he is missing nothing.

"In the end, there is no one ideal condition for creativity. What works for one person is useless for another. The only criterion is this: Make it easy on yourself. Find a working environment where the prospect of wrestling with your muse doesn't scare you, doesn't shut you down. It should make you want to be there, and once you find it, stick with it. To get the creative habit, you need a working environment that's habit-forming.

"All preferred working states, no matter how eccentric, have one thing in common: When you enter them, they impel you to get started."

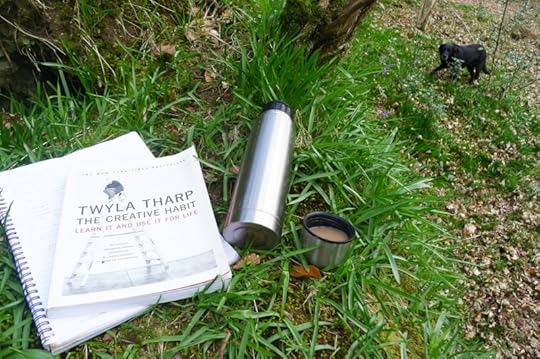

My own morning ritual is to take a walk in the woods behind the studio with Tilly, and then to sit among the trees, by the leat, or up on the hill, with a thermos of coffee, a pen and a journal for scribbling notes, sketches and early-morning ideas ... or else, on those days when I need a lift, with a volume of good poetry instead, which never fails to kickstart my imagination and reignite my love of language.

Tilly sits or prowls nearby until it's time to head home to the studio. Back at my desk, I start the work day by lighting a candle or burning white sage. It's a ritual act of muse-summoning; an offering to the Ancestors (all those previous generations of mythic artists whose footsteps I humbly follow in); and a tangible signal that the workday has begun.

What rituals do you use to start your workday, or to help you cross over from the everyday world into the time-bending realm of creativity? This is a discussion I keep returning to here, as each season brings new work and health challenges, and as I strive to use my time and energy (my spoons) as wisely as I can. Have your own rituals altered over the years? Did you need to make new ones during the pandemic? Or, perhaps, are you one of those contrary souls for whom the very idea of a ritual or routine is anathema?

What helps, what hinders, when you're at your desk or in your studio, and it's time to begin?

Words: The passages above and tucked into the picture captions are from The Creative Habit by Twyla Tharp (Simon & Schuster, 2003); all rights reserved by the author.

Pictures: This is a favourite stopping place in the woods, a nest of green on a crumbling stone wall -- the wall is so old that a whole ecosystem of trees has grown on the top. The wall divides a woodland of oak and pine from the slope of the open hill beyond. It's an in-between place...which folklore reminds us is where magic can be found.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 710 followers