Terri Windling's Blog, page 15

May 19, 2021

Wildflower season

I love the spring months here in Devon, when wildflowers turn the woods and fields and hedgerows into Faerieland, scenting the air with their perfume and the echo of ancient stories. The stress of a long, unfolding pandemic becomes a little easier to bear when the land around us is washed with colour and the hills are breathing magic.

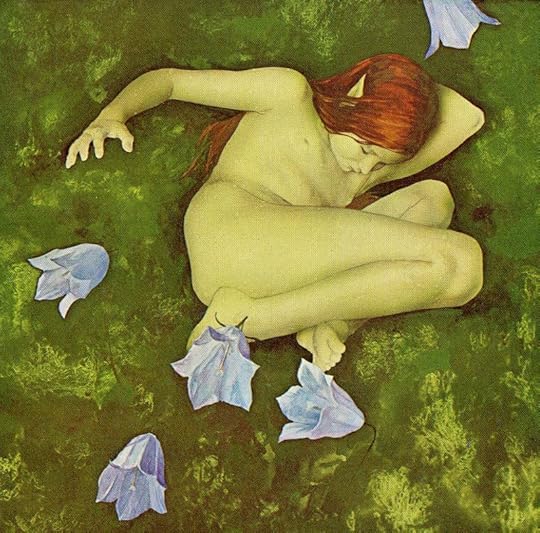

Bluebells are especially loved by faeries, and as such they are dangerous. A child alone in a bluebell wood might be whisked Under the Hill and never seen again, while adults can find themselves lost for days, or years, until the faery spell is broken. Other names the plant is known by: Faery Thimbles, Wood Hyacinths, Harebells (in Scotland, for they grow in fields frequented by hares), and Dead Man's Bells (because the faeries are not kind to those who trample willfully upon them).

Bluebells in the house can be lucky or unlucky, depending on where in British Isles you live. Here in Devon, it's the former: a bouquet of bluebells, picked with gratitude and tended with care, confers the faeries' blessings on the household and "sweetens" spirits sagging after a long winter. Love potions are made of bluebell blossoms, and a bluebell wreath compels the wearer to tell the truth about his or her affections. Despite this association with love, bluebells in Romantic poetry are symbols of loneliness and regret; while in the Victorian's Language of Flowers they represent kindness, humility, and a sense of wonder.

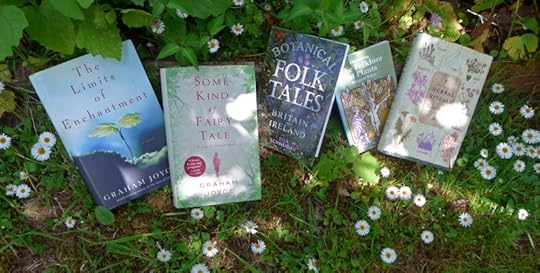

In Some Kind of Fairy Tale, Graham Joyce captured the uncanny magic of a bluebell wood:

"The bluebells made such a pool that the earth had become like water, and all the trees and the bushes seem to have grown out of the water. And the sky above seemed to have fallen down to the earth floor; and I didn't know if the sky was the earth or the earth was water. I had been turned upside down. I had to hold the rock with my fingernails to stop me falling into the sky of the earth or the water of the sky."

Graham's faery novel for adult readers is both magical and sinister, and highly recommended; as is The Limits of Enchantment, a fine novel rich in the folklore of plants and hares.

Wild violets are often associated with the Greek myth of Persephone, for she was out in the fields gathering the flowers when Hades abducted her into the Underworld; they are flowers of change, transition, transformation, and the cycle of death-and-rebirth. In the Middle Ages, the violet represented love that was new, uncertain, changeable or transitory; yet by Victorian times, in the Language of Flowers the violet was a symbol of constancy.

Here in Devon, old country folk are wary of bringing violets (and snowdrops) into the house, for this will curse the farmwife's hens and make them unable to lay. Dreaming of violets is lucky, however, as is wearing the flowers pinned to your clothes...but only if the violets are worn outdoors. Take them off at your doorstep and leave them for the faeries, alongside a bowl of fresh milk.

Primroses guard against dark witchcraft if you gather their blossoms properly: always thirteen or more in a bunch, and never a single flower. On May Day, small primrose bouquets were hung over farmhouse windows and doors to keep black magic and misfortune out, while allowing white magic to enter freely. Primroses were braided into horses' manes and plaited into balls hung from the necks of cows and sheep as protection from piskie mischief on May Day and Beltane.

Hedgewitches made primrose oinment and infusions for "women's troubles" (menstrual cramps) and "melancholy" (depression), while oil of primrose, rubbed on the eyelids, strengthened the ability to see faeries. Primrose wine was a courting gift, proclaiming the giver's constancy -- though by Victorian times, in the Language of Flowers, primroses symbolized the opposite, so a gift of them demonstrated how little you trusted a fickle lover's fine words.

Blue sicklewort (also known as bugle, bugleweed, middle comfrey, and horse & hound) is related to the mint family, and has longed been used as a medicinal herb. The foliage contains a digitalis-like substance, which causes a mild narcotic effect when ingested. In folklore, too, it's a medicine plant, associated with the healing of the body and of hearts broken by sorrow. Once, during a time of great sadness, I felt myself compelled to keep visiting this patch of blue sicklewort in the woods behind my studio. I'd sit on the ground with my coffee thermos and notebooks, finding a strange kind of comfort there. It was only later that I discovered the plant's traditional use as a healer of heartbreak.

The wild orchid is another flower associated with faeries, particularly those who delight in seducing mortals in the woods. It is a plant associated with faery revels, amours, and sensuality. The dried root was a faery aphrodisiac.

The old folk of Devon still know pink stitchwort as "piskie" or "the piskie flower." Anyone who dares to pick them (as I do) is in danger of being piskie-led.

Foxglove, with its long pink and white spires, has long been associated with the faeries. Some scholars believe that ''fox'' is a corruption of ''folk,'' and that the name thus means ''the gloves of the Good Folk'' (the faeries). Foxglove used to be known as goblin's gloves in the mountains of Wales, where the flowers were worn by hobgoblins. In Scandinavian lore, foxglove is associated with both foxes and faeries, for the faeries taught foxes to ring the bell-like flowers in warning when hunters approached.

(We'll look more closely at the folklore of foxgloves next week.)

In her lovely book Botanical Folk Tales of Britain and Ireland, my friend Lisa Schneidau writes:

"I was lucky. I was a little girl growing up in 1970s Buckinghamshire with a mother and grandmother who loved wild plants, and six fields of ridge-and-furrow, green-winged orchid meadow behind our house. I remember when the moon daisies were nearly as tall as me, when we picked field mushrooms from the fairy rings and fried them for breakfast, when I could run through the middle of ancient hawthorne hedgerows and travel by secret ways down to the magic old willow tree over the pond. I remember the carpets of cowslips, the endless butterflies, the quivering quaking grass, and the blackberries in autumn....I inherited an insatiable curiosity for plants of all kinds and, with a vivid imagination as always, I wanted to know the stories: why? what? how does it feel to be a green living plant, a meadowsweet compared to a bee orchid?"

"Flowers lure us into the present moment by the miracle of their beauty," writes another friend, Judith Berger (in Herbal Rituals, a beautiful book about medicine plants through the four seasons). "Watching and waiting for a particular plant to bloom gives birth to patience within us. We slow our rhythm down in order to fully experience the process of flowering; expectancy and excitement deepen hand in hand with our patience. As we observe, we come to see that the full unfolding of the flower petals is the culmination of an unhurried dance in which the flower senses and responds, moment by moment, to the environmental conditions which surround and penetrate it. These conditions include termperature, moisture, light, and shadow, as well as the more subtle influences of sound vibrations, heartful care, and respect.

"In Buddhist poetry, there is a verse which reads: 'I entrust myself to the earth, the earth entrusts herself to me.' To entrust is to place something in another's hands with the confidence that what has been given will be cared for."

And so in the changeable days following winter -- now warm, now cold, now wet, now dry -- I entrust myself to the flowers of our hill: bluebell, primrose, blue sicklewort, white and pink stitchwort, red campion. They all emerge whatever the weather, bursts of color and joy in the rain-soaked hills. They do not wait for a "perfect" day to bloom...and neither must I await the "perfect" time to write, or paint, or to pick up the reins of daily life again after illness and grief knocked me flat earlier this year. Recovering one's health is not like stepping through a gateway into bright sun; there is no clear line between "sick" and "well," only the deep, invisible processes of healing, slowly unfolding day by day. To wait for strength, ease and "perfect" pain-free hours is to wait for life to begin instead of living.

And so in the changeable days following winter -- now warm, now cold, now wet, now dry -- I entrust myself to the flowers of our hill: bluebell, primrose, blue sicklewort, white and pink stitchwort, red campion. They all emerge whatever the weather, bursts of color and joy in the rain-soaked hills. They do not wait for a "perfect" day to bloom...and neither must I await the "perfect" time to write, or paint, or to pick up the reins of daily life again after illness and grief knocked me flat earlier this year. Recovering one's health is not like stepping through a gateway into bright sun; there is no clear line between "sick" and "well," only the deep, invisible processes of healing, slowly unfolding day by day. To wait for strength, ease and "perfect" pain-free hours is to wait for life to begin instead of living.

This is life. This is spring. Bright and beautiful yesterday. Cold, wet, and grey now. Tomorrow, something else again. But full of wildflowers.

Words: The passages quoted above are from Some Kind of Fairy Tale by Graham Joyce (Doubleday, 2012), Botanical Folktales of Britain & Ireland by Lisa Scheidau (The History Press, 2018), and Herbals Rituals by Judith Berger (St. Martin's Press, 1998). The quotes in the picture captions are from a variety of sources, including Discovering the Folklore of Plants by Margaret Baker (Shire Classics, 2008), A Contemplation on Flowers: Garden Plants in Myth & Literature by Bobby J. Ward (Timber Press, 2009) and Hedgerow Medicine by Julie Bruton-Seal & Matthew Seal (Merlin Unwin Books, 2008). All rights reserved by the authors.

Pictures: The paintings, by Brian Froud, are from Faeries by Brian Froud & Alan Lee (Abrams, 1978). All rights reserved by the artist. The photographs were taken when this piece was first written a couple of years ago -- except the final photo, taken yesterday. Tilly is wary of bluebell fairies here, and the dangerous glamour of their fragrant, ephemeral magic.

Seasons, cycles, and Arum maculatum

Beltane has passed, and now the Great Wheel brings us to an enchanting and enchanted time of year, the turning of one season to the next: the liminal space between the quickening spring and the fecundity of summer. In folklore, the days of the In-Between have a particular magical potency. Certain herbs are gathered, following the cycles of the moon. Certain stories are told at this time of the year and no other. Certain flowers and leaves are brought into the house (conferring love, or health, or protection from fairy mischief), while others are best left to the wild, or avoided altogether.

Arum maculatum is a woodland plant in the latter category. Emerging each year just before Beltane, it brings a fresh green cheer to the woods -- and yet it must be treated with care, for touching this plant can cause allergic reactions ranging from mild to severe, and its orange-red berries, beloved by rodents, are poisonous to everyone else.

Arum maculatum is a woodland plant in the latter category. Emerging each year just before Beltane, it brings a fresh green cheer to the woods -- and yet it must be treated with care, for touching this plant can cause allergic reactions ranging from mild to severe, and its orange-red berries, beloved by rodents, are poisonous to everyone else.

I'm terribly fond of them nonetheless, and wait for them eagerly every year, noting their slow emergence as the wild daffodils start to fade. Then, when the weather begins to warm, these lusty plants leap up bold as you please, unfurling their spear-shaped leaves to reveal a fleshy spadix in a pale green hood. Here in Devon, they're known by a number of names: cuckoo-pint, soldiers diddies, priest's pintle, wake robin, willy-lily, stallions-and-mares, and lords-and-ladies, all of them with rude connotations. In America, you probably know them best as Jack-in-the-pulpits.

The folklore attached to Arum maculatum has an equally zesty nature. The plant was associated with Britain's old May Day traditions, which included sexual congress in the fields to ensure the land's fertility. As such, it was deemed a "merry little plant" until Victorian times, and then denounced as devilish, lewd, and symbolic of unbridled sin. (Young girls were warned they must never touch it, because it could make them pregnant.) Herbalists from ancient Greece to medieval Britain extolled the arum's starchy roots for the making of aphrodisiacs, fertility aids, and other medicines focused on the reproductive system, while juice squeezed from the leaves was used for various skin complaints. Due to the arum's toxins, however, great skill was needed to render it safe. In the herb-lore of Wales and the West Country, the secret knowledge of how to to work with the plant came, it was said, from the local fairies -- handed down through mortal families entrusted to use it wisely.

As the days roll on towards Midsummer, the small patch of Armum maculatum in our woods will fade and disappear, leaving only their witchy stumps of toxic berries behind. And then the berries will vanish too, and full summer will be upon us. The brevity of their appearance is one of the things that endears these plants to me. I wait for them, enjoy their company, and then, a heartbeat later, they are gone. The movement of the woodland through its seasons reminds me there is vitality and a wondrous mystery to be found in nature's cycles and circles....

And as someone who works in the narrative arts, I find that I often need that reminder.

And as someone who works in the narrative arts, I find that I often need that reminder.

Narrative, in its most standard form, tends to run in linear fashion from beginning to middle to end. A story opens "Once upon a time," then moves -- prompted by a crisis or plot twist -- into the narrative journey: questing, testing, trials and tribulations -- and then onward to climax and resolution, ending "happily ever after" (or not, if the tale is a sad or ambiguous one). In the West, our concepts of "time" and "progress" are largely linear too. We circle through days by the hours of the clock, years by the months of the calendar, yet our lives are pushed on a linear track: infant to child to adult to elder, with death as the final chapter. Progress is measured by linear steps, education by grades that ascend year by year, careers by narratives that run along the same railway line: beginning, middle, and end.

But in fact, narratives are cyclical too if we stand back and look through a broader lens. Clever Hans will marry his princess and they will produce three dark sons or three pale daughters or no child at all until a fairy intervenes, and then those children will have their own stories: marrying frogs and turning into swans and climbing glass hills in iron shoes. No ending is truly an ending, merely a pause before the tale goes on.

As a folklorist and a student of nature, I know the importance of cycles, seasons, and circular motion -- but I've grown up in a culture that loves straight lines, beginnings and ends, befores and afters, and I keep expecting life to act accordingly, even though it so rarely does. Take health, for example. We envision the healing process as a linear one, steadily building from illness to strength and full function; yet for those of us managing  long-term conditions, our various trials don't often lead to the linear "ending-as-resolution" but to the cyclical "ending-as-pause": a time to catch one's breath before the next crisis or plot twist sets the tale back in motion.

long-term conditions, our various trials don't often lead to the linear "ending-as-resolution" but to the cyclical "ending-as-pause": a time to catch one's breath before the next crisis or plot twist sets the tale back in motion.

Relationships, too, are cyclical. Spousal relationships, family relationships, friendships, work partnerships: they aren't tales of linear progression, they are tales full of cycles, circles, and seasons. The path isn't straight, it loops and bends; the narrative side-tracks and sometimes dead ends. We don't progress in relationships so much as learn, change, and adapt with each season, each twist of the road.

As a writer and a reader, I'm partial to stories with clear beginnings, middles, and ends (not necessarily in that order in the case of fractured narratives) -- but when I'm away from the desk or the printed page (or the cinema or the television screen), I am trying to let go of the habit of measuring my life in a strictly linear way. Healing, learning, and art-making don't follow straight roads but queer twisty paths on which half the time I feel utterly lost...until, like magic, I've arrived somewhere new, some place I could never have imagined.

I want especially to be rid of the tyranny of Before and After. "After such-and-such is accomplished," we say, "then the choirs will sing and life will be good." When my novel is published. When I get that job. When I find that partner. When I lose ten pounds. No, no, no, no. Because even if we reach our goal, the heavenly choirs don't sing -- or if they do sing, you quickly discover it's all that they do. They don't do your laundry, they don't solve all your problems. You are still you, and life is still life: a complex mixture of the bad and the good. And now, of course, the goal posts have moved. The Land of After is no longer a published book, it's five books, a best-seller, a major motion picture. You don't ever get to the Land of After; it's always changing, always shimmering on the far horizon.

I don't want to live after, I want to live now. Moving with, not against, life's cycles and seasons, the twists and the turns, the ups and the downs, appreciating it all.

Today, I walked among the season's wildflowers, chose a few to bring back to the studio -- where they sit on the bookshelves in a pickle jar, glowing as bright as the sun and the moon. At my desk, I work in a linear artform, writing words in a line across a ruled page -- and the flowers remind me that cycles and seasons should be part of the narrative too. Circular patterns. Loops and digressions. Tales that turn and meander down paths that, surprise!, are the paths that were meant all along. Stories that reach resolutions and endings, but ends that turn into another beginning. Again. Again. Tell it again.

Once upon a time...

Words: The poem in the picture captions is from Jay Griffith's unusual and brilliant book on her journey with bipolar disorder, Tristimania (Penguin, 2016). All rights reserved by the authors.

Pictures: The painting above is "Under the Dock Leaves" by Victorian fairy painter Richard Doyle ((1824-1883). The fairy tale drawings are by Helen Stratton, a British illustrator born in India (1867-1961). The charming little mouse is from Emma Mitchell's book Wild Remedy, which I recommend. The photographs of Arum maculatum and bluebells were taken in the woods behind my studio.

May 18, 2021

Myth & Moor update

Due to the UK's Covid lockdowns, we've seen our daughter only once since the pandemic began -- and for a close-knit family, this long year of communicating by Zoom has been rather hard on us all. Victoria lives with her partner in London, but our house on Dartmoor is still her second home -- so she's back with us for couple of weeks now that the lockdown restrictions have eased. Tilly's transcendent joy upon her arrival was a magical thing to behold.

[image error]I'll be in-and-out of the studio over the next two weeks: still writing, but also making the most of our time with Victoria -- including working together on an art project which we will unveil just as soon as it's ready. As a result, my online time will be limited until the end of May. But rather than put Myth & Moor on hiatus, I'm going to re-publish some popular posts from the archives about the folklore of Devon's wildflowers (which I get a lot of requests for at this time of year), sprinkled with some short book recommendations (so that's new material to read here too).

Once again, many thanks to all of you who carry the conversation forward in your comments below each post, which I appreciate so much (especially the poetry). I read it all with great pleasure every evening, even if I don't often have the "spoons" at day's end to respond. And to those who don't comment but show up here day-after-day and month-after-month nonetheless, thank you for being part of this community too. Your interest in books and art and myth and the other things I rattle on about here is what keeps me going.

The drawing above is by John D. Batten, from Joseph Jacob's More Celtic Fairy Tales. Batten was born here in Devon (in Plymouth) in 1860.

May 17, 2021

Tunes for a Monday Morning

I'm focused on music from Ireland (mostly) and Scotland today: old, new, and the old made new. Let's start with a quiet, eerie traditional ballad and move on there....

Above: "My Son David" (also known as "Edward" and "My Son Henry," Child Ballad #13) performed by Atlantic Arc, a new ensemble of musicians and singers from Ireland, Northern Ireland and Scotland, directed by D��nal Lunny. The ensemble members are Graham Henderson (keyboards), Jarlath Henderson (vocals, guitars, pipes, whistles), Sharon Howley (cello), D��nal Lunny (bouzouki, guitar), Aidan O���Rourke (fiddle), Davie Ryan (drums), P��draig Rynne (concertina), Pauline Scanlon (vocals), and Ewen Vernal (bass). The song is Atlantic Arc's first released, filmed in County Clare (2021).

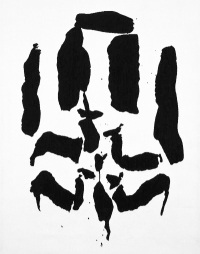

Below: "The T��in," an interpretation of the ancient Irish epic with music by Lorc��n Mac Math��na, contemporary dance by Fearghus �� Conch��ir, and the art of Louis Le Brocquy. The performance was filmed at The Model gallery in Sligo in 2018, with musicians Martin Tourish (piano accordion), Daire Bracken (fiddle) and ��amonn Galldubh (pipes and flute) backing up Mac Math��na's vocals.

Below: "The T��in," an interpretation of the ancient Irish epic with music by Lorc��n Mac Math��na, contemporary dance by Fearghus �� Conch��ir, and the art of Louis Le Brocquy. The performance was filmed at The Model gallery in Sligo in 2018, with musicians Martin Tourish (piano accordion), Daire Bracken (fiddle) and ��amonn Galldubh (pipes and flute) backing up Mac Math��na's vocals.

"The aim of the artists was to give the medieval words of The T��in a physical interpretation combining movement, imagery, and music," Mac Math��na explains. "To give the livid drama of the tale its full breadth with the 'seen' and 'heard' gestures of movement of body, and voice; all in the presence of a selection of Le Brocquys wonderfully animated 'shadows of the text'."

Above: "Abair Liom do R��in (Tell Me Your Secrets)" by Clare Sands, with Steve Cooney and Tommy Sands. "We wrote and recorded the song over three days and nights by candle-light to create a mantra that growls from the belly and sings from the heart," says Sands. "'Abair Liom do R��in' is a transcendent, traditional trance-like ode to Spring." The video, made by visual artists Liadain Ni Bhraon��in and Kasia Kaminska, was filmed in Donegal and has just been released.

Below "The Wild Rover," a traditional song performed by Lankum (brothers Ian & Daragh Lynch, Cormac MacDiarmada, and vocalist Radie Peat), based in Dublin. The song appeared on their album The Livelong Day (2019).

Above: "Blood Moon," an old favourite from the Northern Irish "atmosfolk" duo Saint Sister (Morgan MacIntyre and Gemma Doherty), from their first EP, Madrid (2015). The video was directed by Myrid Carten and Aphra Lee Hill; the young actors are Meabh Parr and Emma White.

Below: "Oh My God Canada," the latest release from Saint Sister. The song will appear on their new album, Where I Should End, due out in June.

And a rousing tune to end with, below:

"Earworm" by The Bonny Men, based in Dublin. The video -- exploring "the tormernt of the creative process" -- was a collaboration between Irish film director Gavin Fitzgerald, choreographer Sib��al Davitt, and The Bonny Men, filmed in a desolate Dublin power station. (In my imagination at least, there's a distinct whiff of Bordertown here.) The song appears on the band's most recent album, The Broken Pledge (2020).

The art today is by Louis Le Brocquy (1916-2012), from his celebrated illustrations for The T��in. All rights reserved by the artist's estate.

May 15, 2021

Books on Books, Part 8

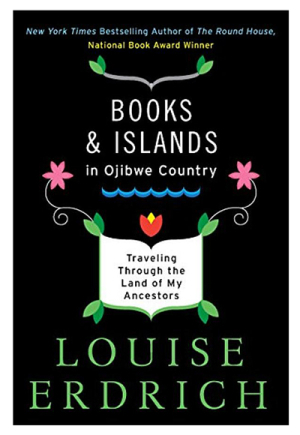

Today, in the last of this series on books about books, there is one final text that I'd like to discuss: Books & Islands in Ojibwe Country: Travelling Through the Land of My Ancestors by Native American author Louise Erdich.

All four of the previous volumes I've recommended have focused on stories for young people, so I wanted to be sure to include a biblio-memoir exploring an adult reading life. Other possibilities came to mind (My Life in Middlemarch by Rebecca Meade, Reading Lolita in Tejran by Azar Nafisi, The Dead Ladies Project by Jessa Crispin, all very good reads), but Books & Islands in Ojibwe Country had to be my choice. I've re-read this little gem of a book more than once since it's 2003 publication, and returned to it again during this pandemic year -- when the tale of Erdrich's travels through the wild lakes of Minnesota and Ontario was a perfect antidote to days confined to bed recovering from Long Covid.

All four of the previous volumes I've recommended have focused on stories for young people, so I wanted to be sure to include a biblio-memoir exploring an adult reading life. Other possibilities came to mind (My Life in Middlemarch by Rebecca Meade, Reading Lolita in Tejran by Azar Nafisi, The Dead Ladies Project by Jessa Crispin, all very good reads), but Books & Islands in Ojibwe Country had to be my choice. I've re-read this little gem of a book more than once since it's 2003 publication, and returned to it again during this pandemic year -- when the tale of Erdrich's travels through the wild lakes of Minnesota and Ontario was a perfect antidote to days confined to bed recovering from Long Covid.

Erdrich, for those who don't know already, is a very fine writer of adult novels, children's fiction, nonfiction, and poetry; she's won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, the National Book Award, the World Fantasy Award, and numerous other honors over her long career. A member the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa, she has a mixed Chippewa/Ojibway, German, and French heritage -- all of which informs her writing in splendid ways. She is also the proprietor of Birchbark Books, an independent bookstore in Minneapolis specializing in Native American literature.

Erdrich begins Books & Islands in Ojibwe Country by explaining its premise:

"My travels have become so focused on books and islands that two have merged for me. Books, islands. Islands, books. Lake of the Woods in Ontario and Minnesota has 14,000 islands. Some of them are painted islands, the rocks bearing signs ranging from a few hundred to more than a thousand years old. So these islands, which I'm longing to read, are books in themselves. And then there is a special island on Rainy Lake that is home to thousands of rare books ranging from crumpling copies of Erasmus in the French and Heloise's letters to Abelard dated MDCCXXIII, to first editions of Mark Twain (signed) to a magnificent collection of ethnographic works on the Ojibwe that might help explain the book-islands of Lake of the Woods.

"I am not traveling alone. First my eighteen-month-old and still nursing daughter and I will pop over the Canada-U.S. border and visit Lake of the Woods and the lands of her namesake, her grandmother. Then we'll dip below the border and travel east to Rainy Lake. We'll put about a thousand miles on our car and several hundred on other people's boats. I'm forty-eight years old and I can't travel aimlessly. I always seem to have a question that I would like to answer. Increasingly, too, it is the same question. It is the question that has defined my life, and the question that most recently has resulted in the questionable enterprise of starting a bookstore. The question is: Books. Why? The islands are really incidental. I'm not much in favor of them. I grew up on the Great Plains. I'm a dry-land-for-hundreds-of-miles person, but I've gotten mixed up with people who live on lakes. And then these islands have begun to haunt me, especially the one with all of the books."

Her journey takes her through "the great mashkiig, or bog, between Red Lake and Lake of the Woods," rich in the traditional plants used by the Ojibwe for healing and sacred purposes, to a small island where Erdrich and little Kiizhikok watch otters play while waiting for the child's father to join them. Eventually Tobasonakwut arrives, packs them into a boat, and takes them into the wild world he'd know as a child growing up on the lake -- before the Canadian government removed his band of Ojibwe from the islands that were their home.

Carrying the reader along on her travels, Erdrich recounts this borderland's long history: the people who once lived there (indigenous and white) and the various ways their stories have come to us -- through oral transmission, through print, through ceremony, through rock paintings that are hundreds and thousands of years old. Erdrich reflects on the Ojibwe language, and on the daily conversation of water, wetlands, and weather. The lake's animals and birds tell stories, whispered into her young daughter's ears.

Carrying the reader along on her travels, Erdrich recounts this borderland's long history: the people who once lived there (indigenous and white) and the various ways their stories have come to us -- through oral transmission, through print, through ceremony, through rock paintings that are hundreds and thousands of years old. Erdrich reflects on the Ojibwe language, and on the daily conversation of water, wetlands, and weather. The lake's animals and birds tell stories, whispered into her young daughter's ears.

Parting ways with Tobasonakwut, Erdrich and Kiizhikok head for the island where Ernest Oberholtzer once lived, and where the enormous library he collected during his lifetime is housed. The island is now managed by a small foundation dedicated to preserving its fragile ecosystem and keeping Oberholtzer's vision alive. He was a close friend to the Ojibwe, Erdrich explains, and now "the foundation honors that relationship by allowing teachers and serious students of the language, as well as one or two Ojibwe writers, to visit on retreat."

Ernest Oberholtzer (1884-1977), known as Ober, was born in Iowa, educated at Harvard, but spent most of his adult life on Mallard Island in the Rainy Lake watershed: exploring, writing, and defending the ecology of the region against dams and industrialization. (To read more about his life, which was colorful and fascinating, go here.) Ober's book collection was legendary: idiosyncratic, extensive, and full of treasures, most of them preserved (or reclaimed) by the foundation and housed on the shelves where Ober left them. Erdrich's description of Mallard Island is delightful. Here's a brief taste:

"On reaching the island, I find I am the last to chose a place to stay. I'm thrilled to find that no one else has decided to sleep at Oberholtzer's house. Though each cabin has its own charm, I've always wanted to stay at Oberholtzer's. I want to stay among what I imagine must have been his favorite books. The foundation has tried to keep the feeling of Ober's world intact, and so the books that line the walls of his loft bedroom were pretty much the ones he chose to keep there, just hundreds out of more than 11,000 on the island. Heavy on Keats, I notice right off, as we enter. Volumes of both the poems and letters. Lots of Shakespeare. A gorgeously illustrated copy of Leaves of Grass....

"We convene to eat in an old 20th century cook's barge used by lumber companies to feed their crews as they ravaged the northern old-growth trees and floated the logs down to the sawmills. Ober had this cook's barge hauled to his island. An old bell signals meals. Original plates and dishes of every charm -- Depression glass, milk glass, porcelains, and sweet old flowery unmatched Royal Doulton china dishes -- crowd the open shelves. A cabin just out front of the cook's barge, hauled here too, was once a floating whorehouse, I am told. Now it houses a piano, and three neat beds. A child has written a sign, tacked to its wall, that advises visitors not to be alarmed if they see things they are unprepared to see -- like spirits. There is supposed to be a spirit family that inhabits this island.

"I'll tell you right off, I don't see hide nor hair of the spirits. But I can't speak for Kiizhikok, with her still open fontanel. They might be talking to her. Or singing her to sleep. Because she sleeps on this island, takes naps of an unprecedented length and then tumbles into sleep beside me as I read long into the night. There is a fever that overcomes a book-lover who has limited time to spend on Ober's island. A fever to read. Or at least to open the books. There is no question of finishing or even delving deeply. I have only days. Among the books, I feel what is almost a long swell of grief, of panic.

"Once the baby is asleep I vault over to Ober's shelves. I first wash and dry my hands -- I just have to. Really, I suppose I should be wearing gloves. Then with a kind of bingeing greed I start, taking one book off the shelves, sucking what I can of it in, replacing it. This goes on for as many hours as I can stand. C.K. Chesterton on William Blake. Ben Jonson's Works in Four Volumes, Oxford University, 1811. Where the Blue Begins by Christopher Morley, illustrated by Arthur Rackham, first edition and first printing. An 1851 copy of The House of the Seven Gables. And The Voyages of Peter Esprit Radisson, Being an Account of His Travels and Experiences Among the North American Indians. A wonderful volume, more recent than most, published in 1943 and transcribed from original manuscripts in the British Museum. I keep reading this last book until, late at night, the loons in full cry, my mosquito coil threading citronella smoke, I have to quit. Knowing I must be alert tomorrow to feed Kiizhikok, I force myself to sleep. But as I drift away with her foot in my hand, I am led to picture an alternate life.

"In my imagined life, there is an enchanted interlude. All children are given a year off from school to do nothing but read (I don't know if they'd actually like this, but in my fantasy my daughters are exquisitely happy). We come to this island. One year is given to me, also, to read. I am not allowed to write. I am forced to do nothing but absorb Oberholtzer's books. Every day, I pluck down stacks of books from the shelves upon shelves tacked up on every wall and level of each of the seven cabins on Ober's island. Slowly, I go through the stacks, reading here and there until I find the book of which I must read every word. Then I do read every word, beneath a very bright lamp. When my brain is stuffed, my daughters and I go swimming, play poker, or eat. Life consists of nothing else."

Jorge Luis Borges famously once said: "I have always imagined that Paradise will be a kind of library."

For me, Paradise might look a lot like Ober's island (minus the mosquitos), and I long to be able to go there and lose myself among his books. At least we can visit through Erdrich's words, and I urge you to give Books & Islands a try. It is insightful, spell-binding, packed with information, and enchants me anew every time I read it.

The art today is by Pat Kruse, a member of the Red Cliff Band of Ojibwe in Wisconsin and a descendent of Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe in Minnesota. Born into a family of birchbark artists, Kruse creates basketry, wall murals and more from birchbark, quill, deer sinew, and other traditional materials. His work can be found the permanent collections of the National Museum of the American Indian-Smithsonian (Washington D.C.), the Science Museum of Minnesota, and the Minnesota Historical Society, among others.

"A birchbarker for over thirty years," he writes, "I am greatly influenced by my mother. Using the skin of the birch tree I remake old-style Ojibwe baskets, sometimes decorating with dyed porcupine quills. I make 'birchbark paintings' using different colors of cut-out birchbark designs, or scrape designs on birchbark to tell stories. Like my ancestors, I harvest birchbark using techniques that do not kill the tree. Having respect for birchbark, I waste nothing."

To see more of Kruse's work, please visit his website.

Words: The passages above are from Books & Islands in Ojibway Country: Traveling Through the Lands of My Ancestors by Louise Erdrich (National Geographic Society, 2003; Perennial, 2014). All rights reserved by the author.

Pictures: The birchbark art above is by Pat Kruse; all rights reserved by the artist. The color photographs of Earnest Oberholtzen's island are by Rosemary Washington, from her lovely account of her Arts Residency on the island in 2017. All rights reserved by the photographer.

May 14, 2021

Myth & Moor update

Oh dear, another day caught up in work deadlines. The final post in the Books on Books sequence is almost done. I'll have it up for you tomorrow. Goodnight all.

Pictures: some little people from my sketchbooks

May 13, 2021

Books on Books, Part 7

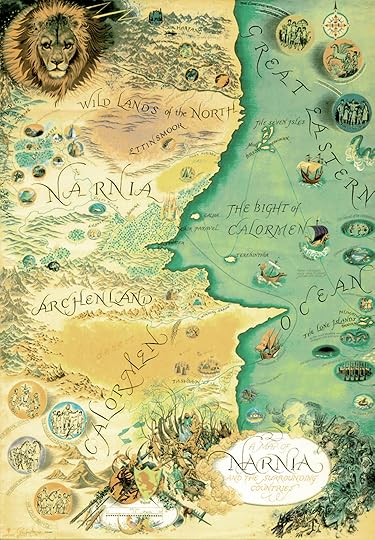

Continuing yesterday's discussion, I'd like to share a bit more from Katherine Langrish's new book, From Spare Oom to War Drobe: Travels in Narnia With My Nine Year-Old Self. Here she discusses The Magician's Nephew, which is the first book in the Narnia timeline (though not the first written or published):

"For those who came to The Magician's Nephew as I did, after reading several of the others first -- this would include most of its original readers -- there is a brisk, fresh energy to the narrative with its new characters and new setting. The first four pages (three minus the illustrations) form a brilliantly economical scene-setting and tell us everything we need to know about Polly and Digory, and Digory's Uncle Andrew, mad Mr. Ketterley. Within another page or so Polly is showing Digory her den in the attic, a dark place behind the cistern where she keeps a box containing various personal treasures, a story she's writing, and of course provisions: apples, and bottles of ginger beer which make the den look satisfactorily like a smugglers' cave.

"Polly is tough, practical, and confident, with a strong sense of self-respect. (And she is the only character in all the Narnia stories who is a writer. I wonder what she wrote about?) She is an excellent partner for the impulsive and more emotional Digory. In his 1998 article for The Guardian, 'The Dark Side of Narnia,' Philip Pullman has complained that in the Narnia books Lewis is guilty (among other crimes) of sending the message 'boys are better than girls.' Possibly it's not fair to take someone to task for an opinion in a newspaper article written so long ago, and some of Pullman's accusations are justifiable, but hardly this one. I cannot see it and never have. To base an accusation of sexism on 'the problem of Susan' alone is to ignore the strength of such different characters as Polly, Lucy, Aravis and Jill -- all gallant, courageous and memorable. I do wonder how recently Mr. Pullman had read the books.

"A little girl myself, I certainly didn't feel excluded or denigrated. The easy, bickering comradeship between Polly and Digory was just what I was used to in E. Nesbit's books. Moreover, Polly sounded like me: I wrote secret stories! With my brother, I loved to make dens -- in hedges, cupboards, in corners of the playground, in barns, in attics, sheds and lean-to's, in patches of waste ground, on building sites. (Pacing stilt-like, ten feet up, across the open floor-joists of a half-completed house, my brother fell across and through them, badly scraping his ribs. We didn't confess.)

"Just as the Bastable children in The Treasure Seekers play detectives and spy on the empty house next door, Polly and Digory explore further down the attic tunnel, hoping to come out in the abandoned house next-door-but-one. They try to calculate how far they will have to go, and I don't notice any nonsense about boys being better than girls: the children are equally and endearingly erratic with their sums, getting different answers, trying again, and even then not getting it right. Their mistake leads them to emerge in the wrong house. Pushing open a little door in the rough brick wall, they see not a barren attic but a comfortably furnished room -- lined, of course, with books. Everything is silent. No one seems to be here. Full of curiosity, Polly puffs out the candle-flame and steps through the door...."

But Katherine, like many other readers, is not forgiving of C.S. Lewis's portrayal of Susan in The Last Battle, the final book of the sequence (and arguably the most flawed):

"At the very end of John Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress, Ignorance, who has followed the hero Christian from the City of Destruction (the world) to the Celestial City on top of Mount Zion (heaven) is refused entry. Instead of keeping to the King's Highway he has taken the by-roads, dodging the hardships and not learning the lessons, so when he comes to the gates he has no passport and is turned away:

"'Then they took him up, and carried him through the air to the door that I saw in the side of the hill, and put him in there. Then I saw that there was a way to hell, even from the gate of heaven, as well as from the City of Destruction.'

"Susan is made an example of by Lewis to illustrate the same point. Her sins, according to her friends, are numerous. Eustace complains that she regards Narnia as a childish game. Jill says Susan's only interested in 'nylons and lipstick and invitations.' Polly -- Polly! -- snarkily accuses Susan of having wasted all her time at school waiting to be the age she is now (is this really the sensible, responsible Susan who was so excellent at swimming and archery?) and predicts that she'll waste the rest of her life trying to stay that age.

"It is a ludicrous prediction: Polly cannot possibly know how Susan will behave for the rest of her life. Even God doesn't judge you until you're dead. What Lewis clearly hopes to convey is that Susan has been lost to worldliness, but it's a sorry try. Nylons? What else did he think a young woman would put on her legs in 1955? The reference to lipstick may have worked (a bit) when I was a pony-mad nine year-old with no conception of ever wanting to use make-up or talk to boys, but it's poor evidence for the eternal damnation of a character who simply seems to have reached adolescence or committed what A.N. Wilson has called 'the unforgiveable sin of growing up.' Lewis has grafted all this on to Susan's character, and the whole thing is trivialised by the shocking indifference of her family and friends as they line up to drop a few catty remarks and dismiss her:

"'Well, don't let's talk about that now,' said Peter. 'Look! Here are lovely fruit trees. Let us taste them.'

"Lovely fruit trees? Huh!"

I had the same reaction to Lewis's betrayal of Susan when I was a child, though I could never have articulated the problem so well; and half a century later, I still feel that same indignation. Susan deserved better. But as for the other girls in the seven Narnia books, to me they were heroes all.

Words: The passage quoted above is from From Spare Oom to War Drobe: Travels in Narnia With My Nine Year-Old Self by Katherine Langrish (Darton, Longman & Todd Ltd, 2021). The Philip Pullman quote is from "The Dark Side of Narnia" (The Guardian, October 1, 1998). All rights reserved by the authors.

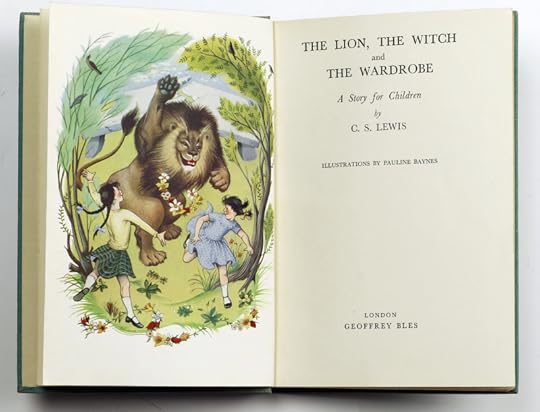

Pictures: The Narnia map and book illustrations above (from The Magician's Nephew and The Last Battle) are by Pauline Baynes (1922-2008). All rights reserved by the Baynes estate.

May 12, 2021

Books on Books, Part 6

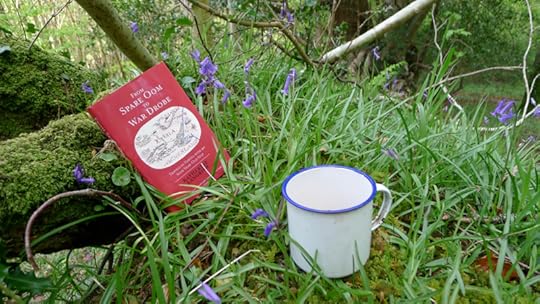

The next volume in our discussion of books about books is From Spare Oom to War Drobe: Travels in Narnia With My Nine Year-Old Self by Katherine Langrish, pictured here in the most Narnia-like place I know: a bluebell wood at the edge of Dartmoor.

I loved The Chronicles of Narnia when I was young, studied C.S. Lewis as an undergraduate, have read countless books by and about him since (from biographies and Inkling studies to Laura Miller's The Magician's Book), and it's fair to ask: do we really need a new book about Narnia? It turns out we do. For me, this journey back into the magic lands I'd known best as a child woke feelings I had lost since then: the intensity of my engagement with Narnia, and my utter belief in it, on that long-ago day when I first tumbled through the wardrobe with Pevensie children.

Katherine Langrish is the author of five fine books for children, a splendid book about fairy tales and the Seven Miles of Steel Thistles blog on folklore, myth, and fantasy; and I can think of no better companion to have in the Woods Between the Worlds. Full disclosure: the two of us are friends, and it happened in an unusual way. In Katherine's words:

Now here is the story of how I had the happy chance to meet Terri Windling. My younger daughter is best friends with her step-daughter, and occasionally, as young people do, she would toss out a small scrap of information about her friend���s family:

"Her step-mum writes."

"Does she? What sort of thing does she write?"

"I don���t really know, but she���s very nice."

So it took me ages to get around to asking more questions. (Note to self: always ask more questions!) Presumably a similar rivulet of information was flowing in the other direction too....Eventually however, the penny dropped."

Honestly, what are the chances that two best friends have mothers who write fantasy, and that it took us such a long time to make the connection? But I digress from the purpose of this post, which is to give you a taste of Katherine's book, and to convey what a rich and necessary read it is for all who love Narnia too.

In the book's Introduction, Katherine writes:

"It is impossible to exaggerate the effect the Narnia stories had on me. I loved them deeply, jealously, selfishly: was so possessive about them that when my mother suggested she might read The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe as a bedtime story to me and my brother, I vetoed it. Aslan would have growled, but I wanted to keep Narnia all to myself. (My brother read them anyway.) Another time I remember saying tentatively to my mother, 'It almost feels as if Narnia is real,' when what I meant was, 'Narnia has to be real,' because the alternative -- that it had no existence except between the pages of a book -- was unbearable. My mother didn't spoil anything for me by telling me that Aslan 'is' Christ. She just replied quietly, 'I think you're meant to feel that way.'

[image error]"Philip Pullman, one of Narnia's most outspoken critics, has suggested children enjoy the series because they lack discrimination: 'Why the Narnia books are popular with children is not difficult to see. In a superficial and bustling way, Lewis could tell a story, and when he cheats, as he frequently does, the momentum carries you over the bumps and potholes. But there have always been adults who suspected what he was up to.'

"It's true that children are generally inexperienced readers, but that doesn't mean they're not sensitive ones. I couldn't have explained it very well when I was nine, but I knew there was a qualitative difference between the pleasure I got from reading the adventures of Enid Blyton, say, and my far deeper love of the Narnia books. Yes, I enjoyed Lewis's storytelling, but the real enchantment lay in the rich silence of the Wood Between the Worlds, the black sky of the city of Charn, the almost unbearable light of the Eastern Sea, the bleak, gusty heights of Ettinsmoor, and the stars falling like prickly silver rain near the end of The Last Battle. These were the things I loved about Narnia, the things that drew me back again and again. When eventually I noticed the Christian messages in the books, they seemed unimportant by comparison.

[image error]"Then decades passed. The books sat on my shelves. Except for reading a couple to my own children, who were more interested in Harry Potter, I didn't return to them even though I write for children myself. Had they simply become so familiar that I didn't feel the need, or had the charm faded? What might they mean to me now?

"I thought I would read them again, remind myself of what had once enchanted me and discover if it still had the power to do so. Over a period of about eighteen months I re-read all the Seven Chronicles, and this too became a labour of love: a personal journey hand-in-hand with my nine year-old self, tracing as many paths as we could through Lewis's thick forest of allusions not only to Christianity, but to Plato, fairy tales, myths, legends, medieval romances, renaissance poetry and indeed to other children's books. There were many things I hadn't noticed when I was nine, but you don't have to know where a thing comes from before you can enjoy it. I never connected the cold queenliness of the White Witch with Hans Christian Andersen's Snow Queen, nor did I realise that, as Queen Jardis, she owes even more to the Babylonian Queen in Edith Nesbit's The Story of the Amulet. Even though I'd read those stories, they remained separate for me. I saw differences where I now see similarities, and both are important. The Lady of the Green Kirtle was fixed in my imagination well before I met the courtly, dangerous, green-clad queen of the fays riding down from the Eildon Tree on her milk-white steed in the ballad of Thomas the Rhymer:

Her shirt was o' the grass-green silk

Her mantle o' the velvet fine.

In fact the land of Narnia owes its character, richness and depth to precisely the heterogenous mix of mythologies and sources of which Tolkien disapproved. It is like The Waste Land, for children."

While others have written insightful texts about Narnia, both laudatory and critical, there are three aspects of Katherine's book that cause me to love it above the rest:

[image error]First, she evokes the sheer wonder of falling into Narnia for the first time, calling up the child in me who loved the books uncritically, alongside the adult reader who appreciates them in a different way. Second, the depth of her Lewis scholarship is evident, but the book is never dry. Katherine unpacks the symbolism of the stories, teases out their influences and references, and explicates their history without disturbing their timeless magic....and that's not an easy thing to do. Third, as a writer herself, she has an interest in the mechanics of the books: what makes them work, what doesn't, and how they relate to other children's fantasy novels written before or since.

Through reading From Spare Oom to War Drobe I have learned some new things about C.S. Lewis, viewed his work from new perspectives, and thought more deeply about the Narnia stories than I have in years. The book made me want to visit the Chronicles again; and, better still, it inspired me to keep on writing, creating my own doors into enchantment.

To learn more about From Spare Oom to War Drobe, I recommend the book launch video below, which contains a terrific interview with Kath by our mutual friend Amanda Craig (whose books I also love).

The art today is by Pauline Baynes (1922-2008), from the first editions of The Chronicles of Narnia (1950-156). You'll find more of it, and more about the artist, in this previous post: Books on Books, Part 2.

Words & pictures: The passage quoted above is from From Spare Oom to War Drobe: Travels in Narnia With My Nine Year-Old Self by Katherine Langrish (Darton, Longman & Todd Ltd, 2021). The Philip Pullman quote is from "The Dark Side of Narnia" (The Guardian, October 1, 1998). All rights to the text and art above reserved by the authors and the artist's estate.

May 11, 2021

Books on Books, Part 5

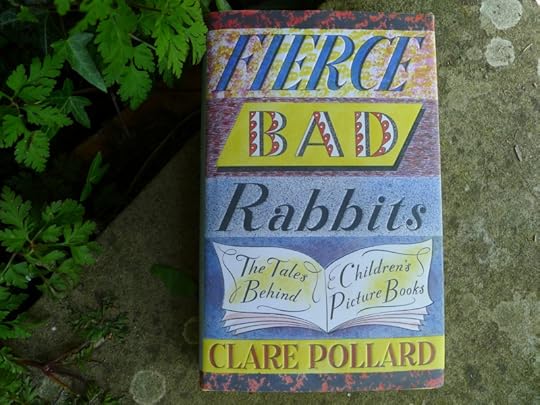

I started this series of post announcing that we'd be looking at four specific "books about books," but we're halfway through the discussion now and I'm going to expand that number to five. In Satuday's post, Lucy Mangan described the special magic of picture books for very young children: the first books that we have read to us, and also the first books we read to ourselves. Clare Pollard has written an excellent volume on the subject: Fierce Bad Rabbits: The Tales Behind Children's Picture Books, and I honestly don't know how it slipped my mind when I sat down to plan this sequence of posts.

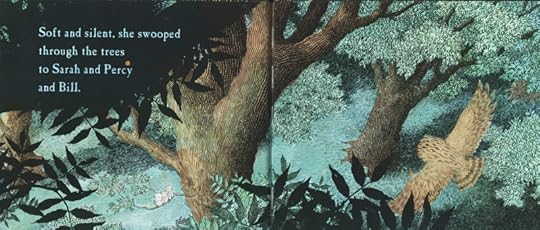

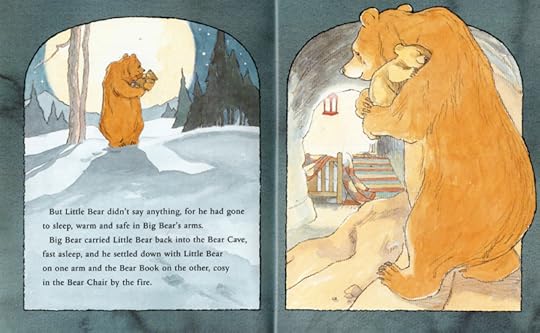

Fierce Bad Rabbits is so good that it's hard to chose a single passage to share with you here, but let's start where we left off on Saturday -- with another tale about owls:

"Owl Babies (1992), written by Martin Waddell and illustrated by Patrick Benson, explores family relationships through absence and presence. Waddell has spoken interestingly about how 'animals are used in picture books because you can make them do things that you wouldn't be able to let children do,' and in Owl Babies the babies are put in a situation that would be impossible to depict in the human world without the mother being reported to social services. They wake in a dark wood and find she has gone, leaving them entirely alone. With their podgy bodies, stumpy wings and flattened, big-eyed faces owls make the perfect avian substitutes for toddlers (hence their ubiquity in books such as I'm Not Scared and WOW! Said the Owl). The three owl babies each react differently, with Sarah trying to be grown-up and sensible, Percy not really helping, and little Bill only able to utter the desperate refrain: 'I want my Mummy!'

"...The interest of the book lies in the question of what your mother does when she's not with you. It is a thought experiment many small children have barely attempted, yet the owl babies spend most of the pages pondering this. Is she hunting? Is she getting them treats ('mice and things that are nice' in Sarah's rhyming phrase)? Is she lost? Has she been caught by a fox?

"The spread on which the owl mother returns shows this, beautifully, from a vantage point high in the treetops. We see her swooping back towards her babies, who are in the distance with their backs towards her, not yet aware their ordeal is over. It says simply, with heartfelt relief: 'And she came.' Waddell has spoken of how originally there was much more text: 'They were the best lines I wrote, but when I saw the image I knew they were redundent.'

"Behind every story, a different story.

"Martin Waddell was born in Belfast in 1941. Just before the Blitz, Waddell's family moved to Newcastle, County Down, beneath the Mountains of Mourne. As a child, life in the area was idyllic, populated by animals and folktales. After his parents split in the 1950s, he moved to London where he signed for Fulham F.C. before realizing he was not going to be able to make his living as a professional footballer. When he turned his hand to writing, he found immediate success with a comic thriller, Otley, made into a film starring Tom Courtenay. Then, in 1969, he married Rosaleen, and they settled back in County Down, and Donaghadee.

"Waddell has described, in an interview with The Independent, how, following the birth of his second son in 1972, a life-altering event occurred. His young family now lived opposite the Catholic Church, and the local UDA would often perform their drill in the street outside. One evening, after he saw a gang of kids hurrying away from the church, Waddell entered the vestry to investigate and saw 'what looked like a wasp's nest' on a chair. The 'nest' lit up. It was a bomb. His first thought after he regained consciousness was that his family were dead. For months afterwards, he would wake up screaming.

"For six years, such was the 'total body shock' he suffered, Waddell couldn't work, so ended up looking after his three small sons at home. In the winter of 1972, they rented a dilapidated house on a rock overlooking the sea, its kitchen often ankle-deep in water. He has said that he was 'given a privilege which very few fathers have: the day-to-day business of looking after the kids. This didn't feel very much like a privilege at the time but it actually led to the richest vein of my own work.' He thought of moving far away but felt too deeply attached to County Down. He watched his children grow up where he had grown up, and where all his stories are set, at the foot of the Mourne Mountains: his precious, vulnerable, only home.

"In 1978 the writing somehow returned. His father has always told him that 'writing books will butter no parsnips,' but Waddell began to draw on his experiences as a father to write picture books.

"By 1988, when his Can't You Sleep, Little Bear? (illustrated by Barbara Firth) won the Smarties Prize, he was an 'overnight' success. Farmer Duck (1991) followed, with pictures by Helen Oxenbury, which she pithily sums up as 'a sort of Animal Farm...for babies.'

"Then came Owl Babies. Waddell has claimed it was written in about three hours after an event in a local supermarket. He came across a small, scared girl standing absolutely still, repeating over and over, 'I want my mummy!' They found her mother eventually, and Waddell had found a story.

"When she returns, the Owl Mother wants to know why there is so much fuss. 'You knew I'd come back.' It is, on one level, a comforting tale, used to reassure children with separation anxiety that they are being irrational.

"But, of course, on another level, Waddell knows their fear is not irrational. And anyway, what was the mother doing? When talking about the book with my friend Hannah, she said that her son is always indignant that the mother doesn't bring back nice juicy mice in her beak. What force of nature made her leave her children, then? From what truth is she protecting them?

"Foxes do indeed prowl outside. The UDA practice; nests explode; wives and babies perish. The father who wakes screaming and the child who shrieks for her mummy both share the same terror."

Fierce Bad Rabbits by Clare Pollard is informative, beautifully written, and thoroughly engrossing. I recommend it highly indeed.

Words & pictures: The passage above is quoted from Fierce Bad Rabbits: The Tales Behind Children's Picture Books by Clare Pollard (Fig Tree/Penguin, 2019); all rights reserved by the author. The illustrations are by Patrick Benson (for Owl Babies), Helen Oxenbury (for Farmer Duck), and Barbara Firth (for Can't Ypu Sleep, Little Bear?). All rights reserved by the artists.

May 10, 2021

Tunes for a Monday Morning

I often start the week with women's voices, so I'm giving men equal time today. The voices lifted here, both solo and in harmony, are raising my spirits on a rain-soaked morning.

Above: "Lovely Molly," a Scottish Travelers' song performed by London-based folksinger & song collector Sam Lee, with Jonah Brody and Joshua Green. The recording was made for the The Lullaby Project in 2016.

Below: "Hares on the Mountain," a traditional English song performed by John Smith, who was born in Essex and raised in Devon. It's from his lovely album Hummingbird (2018).

Above: "The Bothy Lads," performed by the Irish folk duo Ye Vagabonds (brothers Br��an and Diarmuid Mac Gloinn), based in Dublin. They say: "We've always had a great interest in Scottish songs, and the strong connection they have to the Donegal singing tradition -- songs that travelled over and back with seasonal workers for generations until recent times." The video was recorded for Other Voices in 2020.

Below: "My Love's in Germany" performed by the Anglo-Welsh folk trio The Trials of Cato (Tomos Williams, Will Addison, Robin Jones). This traditional Scottish song (with lyrics adapted from an 18th century poem by Hector Macneill) appeared on the their first album, Hide and Hair (2018).

Next, two fine singer/songwriters based in the north of England.

Above: "Seven Hills," written and performed by Greg Russell. The song appeared on Utopia and Wasteland (2018), a collaborative album with Ciaran Algar.

Below: "Lamentations of Round-Oak Waters" (based on the life and poetry of John Clare), written and performed Jim Ghedi. The song is from his powerful new album In The Furrows Of Common Place, with a video filmed in the Outer Hebrides.

Above: "The Poorest Company" performed by Kris Drever, from the Orkney Islands of Scotland. The song was co-written by Drever, Roddy Woomble, and John McCusker, and appeared on their collaborative album Before the Ruin (2013). This solo version was recorded in 2020 during the first UK lockdown. (Here's the earlier version, also beautiful.)

Below: "Row On," performed by Ninebarrow (Jon Whitley and Jay LaBouchardiere ), from Dorset. The lyrics are from a poem found in the log book of a Nantucket whaler in 1846, set to a tune by Dorset musician & storyteller Tim Laycock. The song appeared on Ninebarrow's The Waters and the Wild (2018).

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 710 followers