Terri Windling's Blog, page 16

May 8, 2021

Books on Books, Part 4

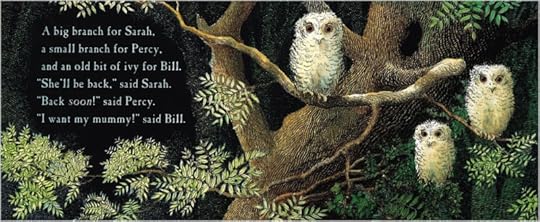

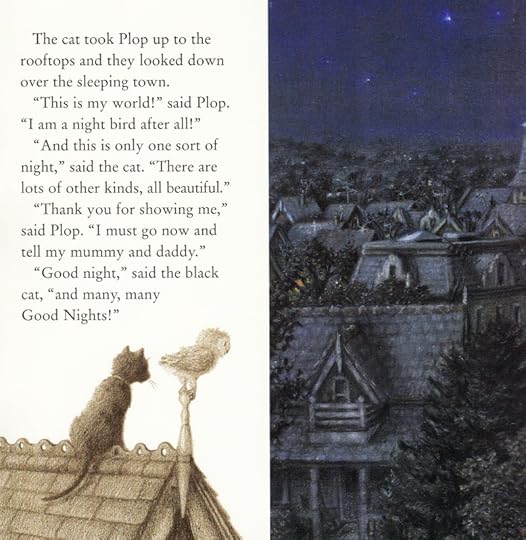

Here's one more post on Lucy Mangan's Bookworm: A Memoir of Childhood Reading before I move on to the next of the four books under discussion. The passage below appears earlier in the text, where Mangan writes about the books that turned her into a reader as a very young child. One of them was The Owl Who Was Afraid of the Dark by Jill Tomlinson (1968), the story of a young barn owl named Plop who wants to be a day bird:

"It was with The Owl Who Was Afraid of the Dark that I truly fell in love with the act of reading itself. I had adored being read to, enjoyed the stories, but the ability to take a book off a shelf, open it up and translate it into words and sounds and pictures in my head, to start that film rolling all by myself and keep it going as long as I pleased (or at least until the next meal, bedtime or other idiotically unavoidable marker of time's relentless passage in the real world was announced) -- well, that was happiness of a different order. When I was reading, the outside world fell away completely and required the application of physical force to break my concentration. Though my mother, as one for whom fiction could never assume any kind of reality, never believed me (any more than she would believe in the years to come that her children were hungry, thirsty or tired outside appointed hours) I never deliberately ignored her calls to come to lunch or dinner or to start cleaning my teeth and get ready for bed. Like every bookworm before or since, I simply and genuinely didn't hear them. Wherever I was with a book -- on the sofa, on my bed, on the loo, in the back seat of a car -- I was always utterly elsewhere.

"Adults tend to forget -- or perhaps never appreciated in the first place if lifelong non-readers themselves -- what a vital part of the process re-reading is for children. As adults, re-reading seems like backtracking at best, self-indulgence at worst. Free time is such a scarce resource that we feel we we should be using it only on new things.

"But for children, re-reading is absolutely necessary. The act of reading itself is still new. A lot of energy is still going into the (not so) simple decoding of words and the assimilation of meaning. Only then do you get to enjoy the plot -- to begin to get lost in the story. And only after you are familiar with the plot are you free to enjoy, mull over, break down and digest all the rest. The beauty of a book is that it remains the same for as long as you need it. It's like being able to ask a parent or teacher to repeat again and again some piece of information or point of fact you haven't understood with the absolutely security of knowing that he/she will do so infinitely. You can't wear out a book's patience.

"And for a child there is so much information in a book, so much work to be done within and without. You can identify with the main or peripheral character (or parts of them all). You can enjoy the vicarious satisfaction of their adventures and rewards. You also have a role to play as interested onlooker, able to observe and evaluate participants' reactions to events and to each other with a greater detachment, and consequent clarity sometimes, than they can. You are learning about people, about relationships, about the variety of responses available to them and in many more situations and circumstances (and at a faster clip) than one single real life permits. Each book is a world entire. You're going to have to take more than one pass at it.

"What you loose in suspense and excitement on re-reading is counterbalanced by a greater depth of knowledge and an almost tangibly increasing mastery over the world. I was not frightened of the world like Plop. But now I knew that some people could be. This was useful. I could be more sympathetic to people who suffered from the same affliction in the real world, and I could also dimly and in a more complicated way understand why some people might find it difficult to understand fears I had that they did not share. The philosopher and and psychologist Riccardo Manzotti describes the process of reading and re-reading as creating both locks and the keys with which to open them; it shows you an area of life you didn't even know was there and, almost simultaneously, starts to give you the tools with which to decipher it.

" 'There is hope for a man who has never read Malory or Boswell or Tristram Shandy or Shakespeare's Sonnets,' C.S. Lewis once wrote. 'But what can you do with a man who says he "has read" them, meaning he has read them once and thinks that this settles the matter?' Exactly. The more you read, the more locks and keys you have. Re-reading keeps you oiled and working smoothly, the better to let you access yourself and others for the rest of you life.

"I don't mean to place too much of a burden on Plop's tiny feathered shoulders, but if we were able some day to trace back a person's development of kindness, toleration or compassion, or their willingness to entertain an alternate point of view, or lifestyle or decision -- how much of it all wouldn't come back to a myriad of such tiny moments as learning that others can be afraid of the dark? In 1932, the French scholar and admirable optimist Paul Hazard wrote a book called Les Livres, Les Enfants et Les Hommes in which he reckoned children would learn about each other through books and that eventually this would end conflict. So far at least it hasn't quite worked out like that, but the point he was making -- that as soon as you begin to read, you begin to cultivate empathy, if only at first in the very smallest of ways -- stands."

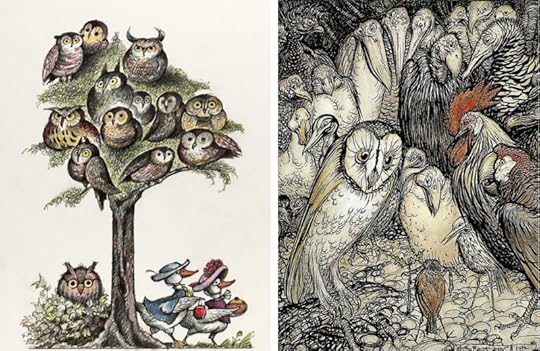

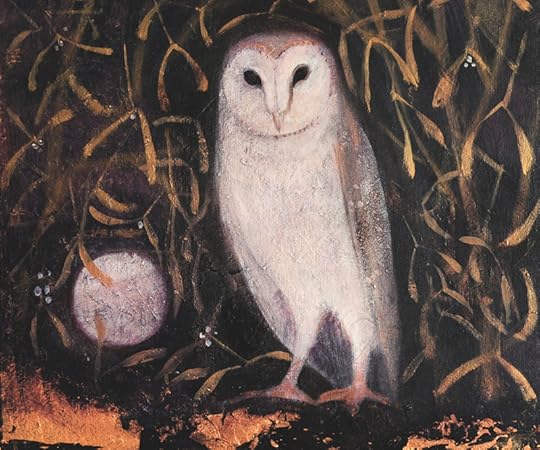

The art today (from top to bottom): Owl and Moon by Angela Harding, The Owl Who Was Afraid of the Dark cover art by Paul Howard, owl illustrations by Maurice Sendak and Petra Brown, Martin Waddell's Owl Babies illustrated by Patrick Benson, a printed page from Owl Babies, A Parliament of Owls by Eric Carle, Aesop's The Owl and the Birds illustrated by Arthur Rackham, a page from The Owl Who Was Afraid of the Dark illustrated by Paul Howard, Jane Yolen's Owl Moon illustrated by John Schoenherr, an owl and fox painting by Jackie Morris, Wise Old Owl and The Owl and the Pussycat by Chris Dunn, and The First Star Gleaming by Catherine Hyde.

Two related posts (in case you missed them): In praise of re-reading -- why it's valuable for adult readers too, and The stories we need -- on learning empathy (or, rather, how I learned empathy) from children's books.

The "Books on Books" series of posts will resume on Tuesday (after the usual Monday music post). Tilly and I wish you all a very good weekend.

Words & pictures: The passage quoted above is from Bookworm: A Memoir of Childhood Reading by Lucy Mangan (Penguin, 2018). All rights to the text and art above reserved by the author and artists.

May 7, 2021

Books on Books, Part 3

Today's "book about books" is Lucy Mangan's Bookworm: A Memoir of Childhood Reading (2018). Having made the mistake of picking it up directly after The Child That Books Built (discussed here), I confess that I had an initial resistance to Mangan's breezier style of writing, but her delightful book soon won me over. Like Spufford's volume, Bookworm blends an account of the author's childhood with bibliographic text full of information on classic books, authors, and publishing history. Her tone is witty and she wears her scholarship lightly, but her depth of knowledge about children's fiction is sound; I learned some new things about favourite books, and discovered plenty of new ones here too.

Mangan's strength is her ability to convey the urgent, vibrant intensity of the relationship children can have with their books. For some kids, of course, books are optional; they get their daily dose of stories through television, games, and other forms of transmission. Mangan acknowledges these alien souls, but it's her fellow bookworms she addresses here: those of us for whom books were (and are) as necessary as water and food. Books, to a bookworm, aren't just ink on the page; they are living presences who share the ups and downs of our lives. They befriend us, console us, startle and change us, tickle us, frighten and devastate us. They feed hungers we didn't know we had and heal wounds we didn't know needed healing.

For a taste of Bookworm, here's a passage describing young Lucy's introduction to Tom's Midnight Garden, during Story Time at her school -- doled out bit by bit as her teacher reads it aloud at the end of each school day:

"Not until the day's work was complete would [Mrs. Pugh] begin. So I spent every day for months in and agony -- or was it an ecstasy? -- of waiting and most of 1984 wishing a short but painful death on my fellow nine- and ten-year-olds who kept delaying us by mucking about and cutting into the twenty-five minutes...on which my day's happiness had come to depend.

"Because the story of Tom Long, who is sent away to stay with relatives while his brother is ill, is exquisite. Lonely and bored, Tom discovers that when the grandfather clock in the communal hallway -- on whose casing is carved the words from Revelation: 'Time no longer' -- strikes thirteen, the magnificent garden that once belonged to the house before it was divided up into flats is restored to it -- along with the equally lonely Hatty who used to play there as a child and who becomes Tom's midnight companion. Tom gradually realises that he is returning to the 19th century, but it takes a visit from his convalescing brother, who accompanies him on one of his nocturnal adventures, to make him realise that time in the garden is moving on and Hatty is growing up. One night, he at last becomes as invisible to her as he has been to everyone else in her world. Soon after that, the garden disappears too and it is almost time for Tom to go home.

"There is one last twist, which I'm not going to spoil for you, partly because I cannot bring myself to rob you of its power and pleasure by badly summarising it, and partly because if I had to learn, through Mrs. Pugh's meagre apportionments, the painful lesson of deferred gratification, I am most certainly going to force the experience on to others too, whenever I can.

"At the time, however, I was so locked in a battle of wills with my teacher that I restrained myself from asking my father to buy the book for me so that I could read on ahead. But as soon as Mrs. Pugh had turned the final page, I dragged him down to Dillons so that I could read the whole thing for myself -- in one sitting, free from the desire to stab Darren Jones in the heart with his ever-clattering pencil -- a process that yielded a better sense of the finely honed shape of the book and its careful, masterly pacing and let me linger over the beauty of the prose and the wealth of possibilities offered by its suggestion that the past and the present could merge into each other if only you knew where to look. And there were no nasty surprises as the shop -- not only was the book still in print, it was still Mrs. Pugh's edition that was on sale, with its properly glossy green cover, Susan Einzig's beautiful illustrations inside and out.

"I see now and delight in the fact that those tortured days of waiting meshed beautifully with the mood of the book. My own hungry anticipation mirrored Tom's impatient wait for his nightly doses of magic perfectly.

"More profoundly, I responded to the sense of longing -- for companionship, for adventure, for people and places long vanished -- that permeates the whole of Tom's Midnight Garden. My distance from it -- again, being read to is far, far better than nothing but it does not compare to reading to yourself -- gave me a heightened sense of how impossible it is to absorb the books we love as fully as we want to. I bet even the Maurice Sendak fan who ate the card the writer sent him felt a sense of anticlimax afterwards.

"We can read, and read, and read them but we can never truly live there. It is an approximation so close that it borders on the miraculous, for sure, and -- unless perhaps you are an actor, and a good actor at that -- there is nothing else that even comes near it, which is what keeps the bookworm going. But still -- you are not in Narnia. You are not actually beneath the floorboards with the Clocks. You are not roaming the prairies with Laura, Mary, Ma and Pa. And yet...and yet...Tom's Midnight Garden is suffused with the pain and the pleasure of yearning. Even as he's playing contentedly in the garden with Hatty before his brother arrives, its nightly appearance and morning disappearance already points to its evanescence. There is always a suggestion that everything is in flux, that nothing can last. The best we can hope for it to live there for a while. And accept that if yew hedges and towering trees cannot endure, happiness too is best understood as fleeting.

"C.S. Lewis once discussed the concept of Sehnsucht -- German for what we would call 'yearning'* - and reckoned this 'unconsolable longing' in the human heart 'for what we know not' was an intimation of the divine. 'If I discover within myself a desire which no experience in this world will satisfy,' he says in Mere Christianity, 'the most probable explanation is that I was made for another world.'

"But perhaps we're more often just made for reading. Each book was to me another world, and none more so than Tom's Midnight Garden, then or now. Because I have re-read it countless times since Mrs. Pugh closed the covers for the final time, and within three pages I am my ten-year-old self again. Within six I am with Tom in his 1950s world and after that we are both in the Victorian garden again with Hatty and the yew trees and hedges that preceded and will outlast them all. I still believe, deep in my heart, that if I wake up at the right moment one night, I, too, will be able to step out of this world and all its inconsolable longings and run wild forever in the gardens of the past. But the best I can do is live there again for a while. Which is, almost, enough. After all, if you are as close to something as you were in childhood, then you have your childhood back again, don't you? Time no longer."

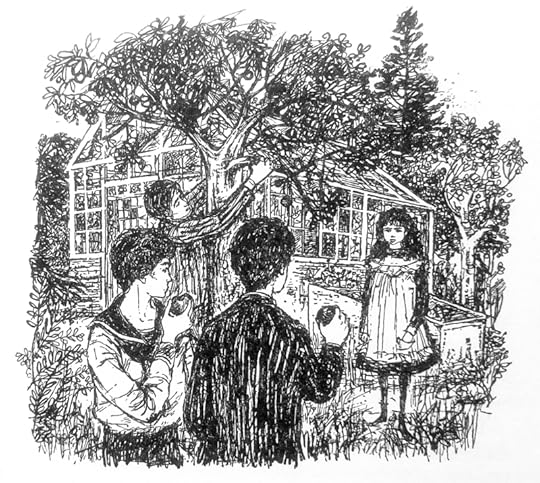

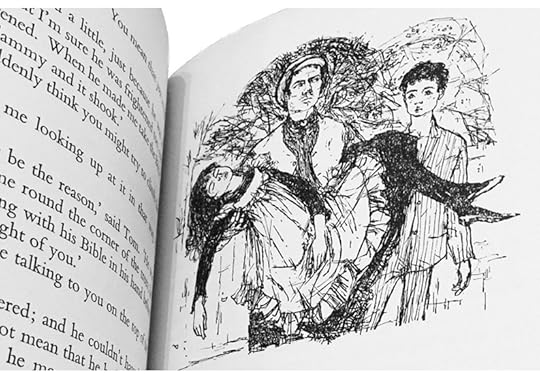

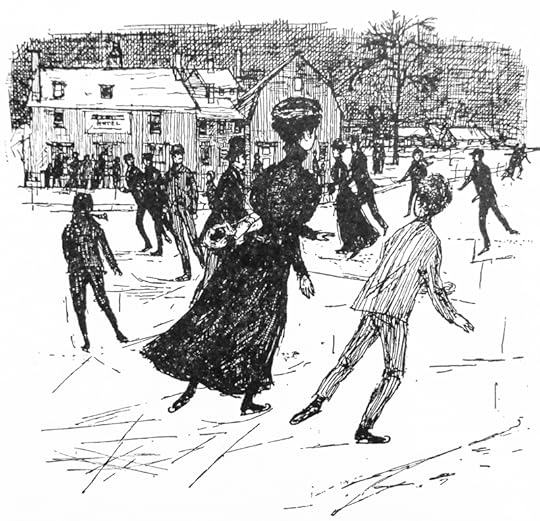

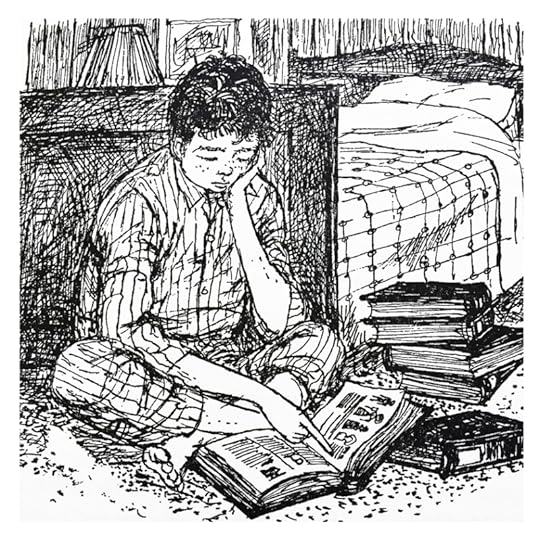

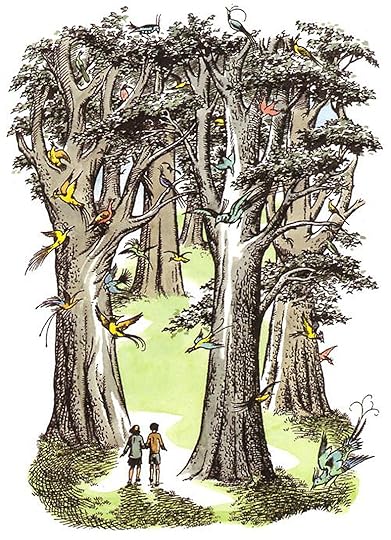

The illustrations here, of course, are by Susan Einzig for Tom's Midnight Garden. Einzig (1922���2009) was born to an affluent Jewish family in Dahlem, Berlin, and studied art at the age of 15 at the Breuer School of Design. Two years later, as World War II loomed, she traveled to England on a Kindertransport train. Her brother and, later, her mother managed to join her in England, but her father died in the Theresienstadt concentration camp.

Einzig studied illustration and wood engraving at the Central School of Arts & Crafts before being evacuated from London to Yorkshire, she then worked in an aircraft factory and as a technical draughtsman for the War Office. At the end of the war, she painstakingly built a successful career as a illustrator, painter, and lecturer. She produced many book illustrations over the years, beginning with art for Norah Pulling's Mary Belinda and the Ten Aunts (1945) and Mrs. Richard's Mouse (1946) -- but she's perhaps known for her later work, including illustrations for Charlotte Bront��'s Jane Eyre (1962) and E. Nesbit's The Bastables (1966). Regarding her now-classic pictures for Tom's Midnight Garden, she said: "I had been to see the children���s-book editor at Oxford University Press, who looked at my work and seemed very unsure about it. However, she gave me Philippa Pearce���s manuscript to try to see if I could do it. I did two or three drawings and took them to show her, and then she asked me to do the book....I was paid just a hundred pounds for the whole thing."

Einzig also taught art at Chelsea School of Art & Design for more than thirty years, associated with a number of the leading artists of her day, and raised at least one child on her own. (Some biographical accounts list two.) For more information on this remarkable woman, go here and here.

* Though as you might expect with such a porous, abstract concept it has slightly different connotations from our word -- theirs means something more like 'life longings', particularly for a home, or homelike place that you have not necessarily experienced, or for something unnameable and indefinable. - L.M.

Words & pictures: The passage quoted above is from Bookworm: A Memoir of Childhood Reading by Lucy Mangan (Penguin, 2018). The cover art is by Laura Barrett; you can can see more of her lovely work here. The rest of the art today is from Tom's Midnight Garden by Philipa Pearce, illustrated by Susan Einzig (Oxford University Press, 1958). All rights to the text and art above reserved by the author and the artists.

May 6, 2021

Myth & Moor update

Oh no! I'm up against a deadline and ran out of time to post today! I'll be back again tomorrow with the next installment of "Books on Books."

Sketchbook pictures: "Merry little pranksters" and "Two Graces"

May 5, 2021

Books on Books, Part 2

Continuing the discussion begun yesterday....

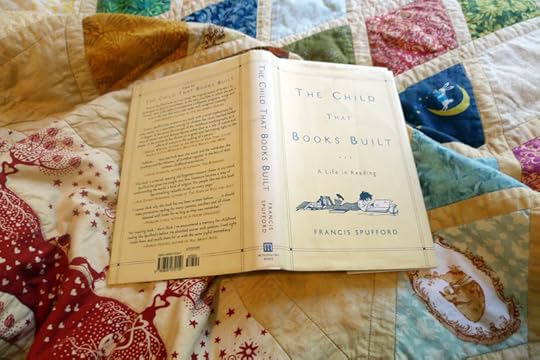

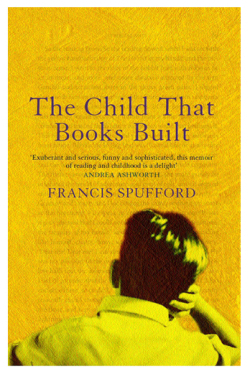

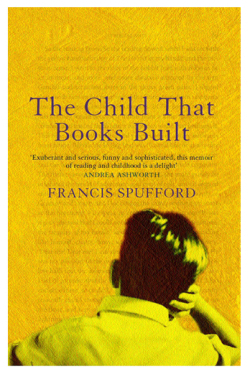

In The Child That Books Built, Francis Spufford recalls the children's tales that sparked his love of reading, and of writing:

"My favorite books were the ones that took books' implicit status as other worlds, and acted on it literally, making the window of writing a window into imaginary countries. I didn't just want to see in books what I saw anyway in the world around me, even if it was perceived and understood and articulated from angles I could never have achieved; I wanted to see things I never saw in life. More than I wanted books to do anything else, I wanted them to take me away. I wanted exodus. "

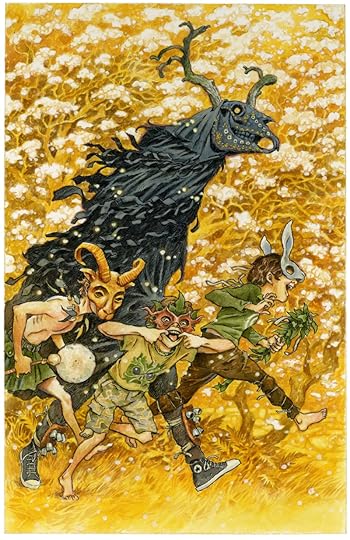

But there's a difference, he notes, between stories set entirely in an imaginary world and stories that start in our own world but then take you to another.

"Earthsea and Middle Earth were separate. You traveled them in imagination as you read Le Guin and Tolkien, but they had no location in relation to this world. Their richness did not call you at home in any way. It did not lie just beyond a threshold in this world that you might find if you were particularly lucky, or particularly blessed.

"I wanted there to be the chance to pass through a portal, and by doing so pass from rusty reality with its scaffolding of facts and events into the freedom of story. If, in a story, you found that one panel in the fabric of the workaday world that was hinged, and it opened, and it turned out that behind the walls of the world flashed the gold and peacock blue of something else, and you were able to pass through, that would be a moment in which all the decisions that had been taken in this world, and all the choices that had been made, and all the facts that had been settled, would be up for grabs again: all possibilities would be renewed, for who knew what lay on the other side?

"And once opened, the door would never be entirely shut behind you either. A kind of mixture would begin. A tincture of this world's reality would enter the other world, as the ordinary children in the story -- my representatives, my ambassadors -- wore their shirts and sweaters amid cloth of gold, and said Crumbs! and Come off it! among people speaking the high language of fantasy; while this world would be subtly altered too, changed in status by the knowledge that it had an outside. E. Nesbit invented the mixing of the worlds in The Amulet, which I preferred, along with the rest of her magical series, to the purely realistic comedy of the Bastables' adventures in The Treasure Seekers and its sequels. On a grey day in London, Robert and Anthea and Jane and Hugh travel to blue sky through the arch of the charm. The latest master of worlds is Philip Pullman. Lyra Belacqua and her daemon walk through the aurora borealis in the first book of the Dark Materials trilogy; in the next, a window in the air floats by a bypass in the Oxford suburbs; in the third installment, access to the eternal sadness of the land of the dead is through a clapped-out, rubbish-strewn port town on the edge of a dark lake.

"As I read I passed to other worlds through every kind of door, and every kind of halfway space that could work metaphorically as a threshold too: the curtain of smoke hanging over burning stubble in an August cornfield, an abandoned church in a Manchester slum. After a while, I developed a taste for transitions so subtle that the characters could not say at what instance the shift had happened.

"In Diana Wynne Jones's Eight Days of Luke, the white Rolls-Royce belonging to 'Mr. Wedding' -- Woden -- takes the eleven-year-old David to Valhalla for lunch, over a beautiful but very ordinary-seeming Rainbow Bridge that seems to be connected to the West Midlands road system. I liked the idea that borders between the worlds could be vested in modern stuff: that the green and white signs on the motorways counting down the miles to London could suddenly show the distance to Gramarye or Logres.

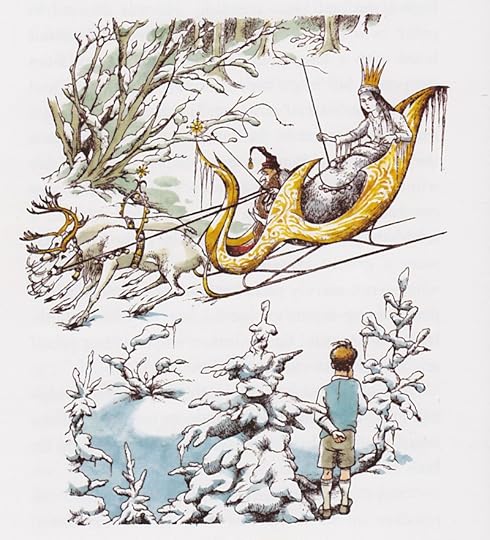

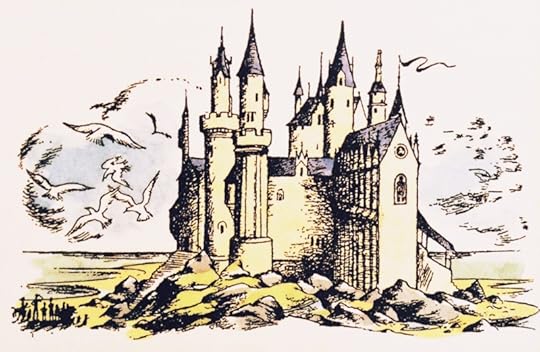

"But my deepest loyalty was unwavering. The books I loved best all took me away through a wardrobe, and a shallow pool in the grass of a sleepy orchard, and a picture in a frame, and a door in a garden wall on a rainy day at boarding school, and always to Narnia. Other imaginary countries interested me, beguiled me, made rich suggestions to me. Narnia made me feel like I'd taken hold of a live wire. The book in my hand sent jolts and shimmers through my nerves. It affected me bodily. In Narnia, C.S. Lewis invented objects for my longing, gave form to my longing, that I would never have thought of, and yet they seemed exactly right: he had anticipated what would delight me with an almost unearthly intimacy. Immediately I discovered them, they became the inevitable expressions of my longing. So from the moment I first encountered The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe to when I was eleven or twelve, the seven Chronicles of Narnia represented essence-of-book to me. They were the Platonic Book of which other books were more or less imperfect shadows. For four or five years, I essentially read other books because I could not always be re-reading the Narnia books."

Lev Grossman was also ensorcelled by Narnia as a boy. In a fine essay on the subject he writes:

"The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe is a powerful illustration of why fantasy matters in the first place. Yes, the Narnia books are works of Christian apology, works that celebrate joy and love -- but what I was conscious of as a little boy, if not in any analytical way, was the deep grief encoded in the books. Particularly in the initial wardrobe passage.

There���s a sense of anger and grief and despair that causes Lewis to want to discard the entire war, set it aside in the favor of something better. You can feel him telling you -- I know it���s awful, truly terrible, but that���s not all there is. There���s another option. Lucy, as she enters the wardrobe, takes the other option. I remember feeling this way as a child, too. I remember thinking, 'Yes, of course there is. Of course this isn���t all there is. There must be something else.'

"How powerful it was to have Lewis come along and say, Yes, I feel that way, too.

"But I bristle whenever fantasy is characterized as escapism. It���s not a very accurate way to describe it; in fact, I think fantasy is a powerful tool for coming to an understanding of oneself. The magic trick here, the sleight of hand, is that when you pass through the portal, you re-encounter in the fantasy world the problems you thought you left behind in the real world. Edmund doesn���t solve any of his grievances or personality disorders by going through the wardrobe. If anything, they're exacerbated and brought to a crisis by his experiences in Narnia. When you go to Narnia, your worries come with you. Narnia just becomes the place where you work them out and try to resolve them.

"The whole modernist-realist tradition is about the self observing the world around you -- sensing how other it is, how alien it is, how different it is to what���s going on inside you. In fantasy, that gets turned inside out. The landscape you inhabit is a mirror of what���s inside you. The stuff inside can get out, and walk around, and take the form of places and people and things and magic. And once it���s outside, then you can get at it. You can wrestle it, make friends with it, kill it, seduce it. Fantasy takes all those things from deep inside and puts them where you can see them, and then deal with them."

In her delightful book Bookworm: A Memoir of Childhood Reading, Lucy Mangan reflects on the fourth book in the series, Prince Caspian:

"The Pevensies return to the magical kingdom to find that hundreds of years have passed, civil war is dividing the kingdom and Old Narnians (many dwarves, centaurs, talking animals, the dryads and hamadryads that once animated the trees, and other creatures) are in hiding. The children must lead the rebels against their Telmarine conquerors. The warp and weft of Narnian life is seen up close, in even more gorgeously imagined detail than the previous books. Lucy, awake one night in the thick of the forest that has grown up since she was last in Narnia, feels the trees are almost awake and that if she just knew the right thing to say they would come to Narnian life once more.

"It mirrored exactly how I felt about reading, and about reading Lewis in particular. I was so close...if I could just read the words on the page one more time, I could animate them too. The flimsy barriers of time, space and immateriality would finally fall and Narnia would spring up all around me and I would be there, at last."

Lucy Mangan's Bookworm is the second of "books on books" I am recommending this week. Like Spufford's The Child That Books Built, Mangan's Bookworm combines a bibliographic text with childhood memoir in order to look at the ways books act on us in our earliest years. More on this tomorrow.....

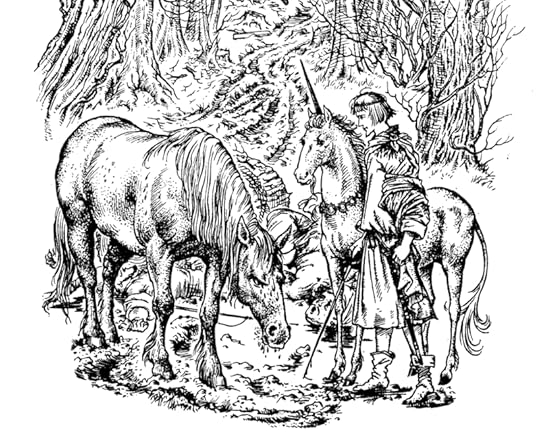

The art today is by Pauline Baynes (1922-2008), from the first editions of The Chronicles of Narnia (1950-156).

Baynes was born in Sussex and spent her early childhood years in northern India, where her father worked with the Indian Civil Service. At the age of five, however, Baynes' mother took her children back to England (leaving their father, ayah, and pet monkey behind) -- a traumatic rupture that haunted the artist for the rest of her life. After miserable periods in strict convent and boarding school, she was allowed to move to the Farnham School of Art at age 15, where she formed her desired to become an illustrator of children's books. She clung to this goal through further studies at the Slade School of Art and Oxford. The war intervened, and the Woman's Voluntary Service sent Baynes to work as model-maker with the Royal Engineers in Falmouth Castle, and then to draw maps and naval charts for the Admiralty in Bath. A colleague from this period belonged to a family firm that published children's books, and it was through this connection that Baynes received her first illustration commissions.

Baynes was born in Sussex and spent her early childhood years in northern India, where her father worked with the Indian Civil Service. At the age of five, however, Baynes' mother took her children back to England (leaving their father, ayah, and pet monkey behind) -- a traumatic rupture that haunted the artist for the rest of her life. After miserable periods in strict convent and boarding school, she was allowed to move to the Farnham School of Art at age 15, where she formed her desired to become an illustrator of children's books. She clung to this goal through further studies at the Slade School of Art and Oxford. The war intervened, and the Woman's Voluntary Service sent Baynes to work as model-maker with the Royal Engineers in Falmouth Castle, and then to draw maps and naval charts for the Admiralty in Bath. A colleague from this period belonged to a family firm that published children's books, and it was through this connection that Baynes received her first illustration commissions.

After the war, Baynes built a solid career creating book cover art and interior illustrations, most notably for J.R.R. Tolkien's tales of Middle-Earth, and the C.S. Lewis' journeys into Narnia. (She had a close friendship with Tolkien throughout his life, whereas her relationship with Lewis was professional and distant.) She also illustrated texts by Hans Christian Andersen, The Brothers Grimm, Rudyard Kipling, George MacDonald, Mary Norton, Arthur Ransome, Alison Uttley, Richard Adams, and many others over the years -- winning the Kate Greenaway Medal for her illustrations to Grant Uden's A Dictionary of Chivalry in 1968.

Baynes worked from her book-crammed study in Surrey, her desk looking out to a high-hedged garden, her beloved dogs sprawled at her feet. She continued illustrating books until the day she died at the age of 85.

The passages above are from The Child That Books Built: A Life in Reading by Francis Spufford (Henry Holt & Co, 2002); "Confronting Reality by Reading Fantasy" by Lev Grossman (The Atlantic, August 2014); and Bookworm: A Memoir of Childhood Reading by Lucy Mangan (Penguin, 2018). All rights to the text and art above reserved by the authors and the artist's estate.

May 4, 2021

Books on Books

Howard and I have been dealing with Long Covid since catching a mild dose of the virus last spring -- and although (touch wood) we're both getting better, my studio hours are still limited as I find my way back to health and strength. But when illness robs us of productivity, breaking down our usual routines, slowing time down to a crawl, it also gives us unexpected gifts -- and for me, that gift is the time read.

Okay, I'd rather be writing, painting, doing, not watching the world through a fever haze, or experiencing life through a printed page -- but on those days when my body fails I'm grateful to books, and to all those who write them.

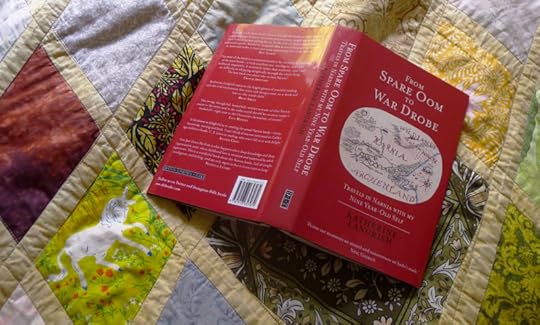

Reading having played a big part in my life for many reasons in addition to health, I have a particular fondness for books about books. Here are four I particularly recommend:

The Child That Books Built: A Life in Reading by Francis Spufford. Bookworm: A Memoir of Childhood Reading by Lucy Mangan. Books & Island in Ojibwe Country: Traveling Through the Land of My Ancestors by Louise Erdrich. From Spare Oom to War Drobe: Travels in Narnia With My Nine-Year-Old Self by Katherine Langrish.

All four weave literary studies with memoir; all four explore the author' s personal relationship with books; all four examine the ways that stories form us, effect us, and define us. I'm planning to discuss them all this week, starting today with The Child That Books Built.

I first read Spufford's book in 2002, the year of its original publication, and what struck me then was the unusual nature of its composition: childhood memoir mixed into literary and publishing history, with digression into cognitive science and child psychology in relation to story. In the intervening years, writers of memoir have expanded the form in so many ways that the structure of Spufford's book has lost its radical edge; I find that I have to remind myself that his memoir was a pioneering text. That said, it is still a cracking good read. Spufford is roughly the same generation I am and grew up with many of the same children's books on his shelves. He also has a taste for fantasy, and discusses the genre with knowledge and love. Although his writing on fairy tales relies too much (for this reader) on the disputed psychoanalytic theories of Bruno Bettleheim, his passion for all things magical wins me over nonethless, along with his poignant exploration of a childhood in which finding doors into other worlds was merciful and necessary.

I first read Spufford's book in 2002, the year of its original publication, and what struck me then was the unusual nature of its composition: childhood memoir mixed into literary and publishing history, with digression into cognitive science and child psychology in relation to story. In the intervening years, writers of memoir have expanded the form in so many ways that the structure of Spufford's book has lost its radical edge; I find that I have to remind myself that his memoir was a pioneering text. That said, it is still a cracking good read. Spufford is roughly the same generation I am and grew up with many of the same children's books on his shelves. He also has a taste for fantasy, and discusses the genre with knowledge and love. Although his writing on fairy tales relies too much (for this reader) on the disputed psychoanalytic theories of Bruno Bettleheim, his passion for all things magical wins me over nonethless, along with his poignant exploration of a childhood in which finding doors into other worlds was merciful and necessary.

Here's a passage from Spufford's introduction to give you a sense of the book as a whole:

"I began my reading in a kind of hopeful springtime for children's writing. I was born in 1964, so I grew up in a golden age comparable to the present heyday of J.K. Rowling and Philip Pullman, or to the great Edwardian decade when E. Nesbit, Kipling, and Kenneth Graham were all publishing at once. An equally amazing generation of talent was at work as the 1960s ended and the 1970s began. William Mayne was making dialogue sing; Peter Dickinson was writing the Changes trilogy; Alan Garner was reintroducting myth into the bloodstream of daily life; Jill Paton Walsh was showing that children's perceptions could be just as angular and uncompromising as adults; Joan Aiken had begun her Dido Twite series of comic fantasies; Penelope Farmer was being unearthly with Charlotte Sometimes; Diana Wynne Jones's gift for wild invention was hitting its stride; Rosemary Sutcliffe was just adding the final uprights to her colonnade of Romano-British historical novels; Leon Garfield was reinventing the 18th century as a scene for inky Gothic intrigue. The list went on, and on, and on. There was activity everywhere, a new potential classic every few months.

"Unifying this lucky concurrence of good books, and making them seem for a while like contributions to a single intelligible project, was a kind of temporary cultural consensus: a consensus both about what children were and about where we all were in history. Dr. Spock's great manual for liberal, middle-class child-rearing had come out at the beginning of the Sixties, and had helped deconstruct the last lingering remnants of the idea that a child was clay to be molded by a benevolent adult authority. The new orthodoxy took it for granted that a child was a resourceful individual, neither ickily good nor reeking of original sin. And the wider world was seen as a place in which a permanent step forward toward enlightenment had taken place as well. The books my generation were offered took it for granted that poverty, disease and prejudice essential belonged in the past. Postward society had ended them.

"As the 1970s went on, these assumptions would lose their credibility. Gender roles were about to be shaken up; the voices that a white, liberal consensus consigned to the margins of consciousness were about to be asserted as hostile witnesses to its nature. People were about to lose their certainty that liberal solutions worked. Evil would revert to being an unsolved problem. But it hadn't happened yet; and till it did, the collective gaze of children's stories swept confidently across past and future, and across all international varieties of the progressive, orange-juice-drinking present, from Australia to Sweden, from Holland to the broad, clean suburbs of America.

"For me, walking up the road aged seven or eight to spend my money on a paperback, the outward sign of this unity was Puffin Books. In Britain, almost everything written for children passed into the one paperback imprint. On the shelves of the children's section in the bookshop, practically all the stock would be identically neat soft-covered octavos, in different colors, with different cover art, but always with the same sans serif type on the spine, and the same little logo of an upstanding puffin. Everything cost about the same. For 17p -- then 25p and then 40p as the 1970s inflation took hold -- you could have any one of the new books, or any of the children's classics, from the old ones like The Wind in the Willows or Alice to the new ones that were only a couple of decades into their classichood, like the Narnia books (C.S. Lewis had died the year before I was born, most unfairly making sure I would never meet him).

"If you were a reading child in the UK in the Sixties or Seventies, you too probably remember how securely Puffins seemed, with the long, trust-worthy descriptions of the story inside the front cover, always written by the same arbiter, the Puffin editor Kaye Webb, and their astonishingly precise recommendation to 'girls of eleven and above, and sensitive boys.' It was as if Puffin were part of the administration of the world. They were the department of the welfare state responsible for the distribution of narrative. And their reach seemed universal: not just the really good books you were going to remember forever, but the nearly good ones too and the completely forgettable ones that at the time formed the wings of reading and spread them wide enough to enfold you in books on all sides."

A little later in the Introduction, Spufford lays out the premise of his memoir:

"I have gone back and read again the sequence of books that carried me from babyhood to the age of nineteen, from the first fragmentary stories I remember to the science fiction I was reading at the brink of adulthood. As I reread them, I tried to become again the reader I had been when I encountered each for the first time, wanting to know how my particular history, in my particular family, at that particular time, had ended up making me into the reader I am today. I made forays into child psychology, philosophy, and psychoanalysis, where I thought those things might tease out the implications of memory. With their help, the following chapters recount a path through the riches that were available to English children of the 1960s and 1970s, and onward into the reading of adolescence. It is the story (I hope) of the reading my whole generation of bookworms did; and it is the story of my own relationship with books; both. A pattern emerged, or a I drew it: a set of four stages in the development of that space inside where writing is welcomed and reading happens. What follows is more about books that it is about me, but nonetheless it is my inward autobiography, for the words we take into ourselves help to shape us. "

It is a premise Spufford amply fulfills in this moving and insightful volume.

Words: The passage above is from The Child That Books Built: A Life in Reading by Francis Spufford (Henry Holt & Co, 2002); all rights reserved by the author. Previous posts that discuss The Child That Books Built include "In the Forest of Stories" (2013) and "Built by Books" (2014). Pictures: The art is identified in the picture captions. (Run your cursor over the images to see them.) All rights reserved by the artists.

Books on books

Howard and I have been dealing with Long Covid since catching a mild dose of the virus last spring -- and although (touch wood) we're both getting better, my studio hours are still limited as I find my way back to health and strength. But when illness robs us of productivity, breaking down our usual routines, slowing time down to a crawl, it also gives us unexpected gifts -- and for me, that gift is the time read.

Okay, I'd rather be writing, painting, doing, not watching the world through a fever haze, or experiencing life through a printed page -- but on those days when my body fails I'm grateful to books, and to all those who write them.

Reading having played a big part in my life for many reasons in addition to health, I have a particular fondness for books about books. Here are four I particularly recommend:

The Child That Books Built: A Life in Reading by Francis Spufford. Bookworm: A Memoir of Childhood Reading by Lucy Mangan. Books & Island in Ojibwe Country: Traveling Through the Land of My Ancestors by Louise Erdrich. From Spare Oom to War Drobe: Travels in Narnia With My Nine-Year-Old Self by Katherine Langrish.

All four weave literary studies with memoir; all four explore the author' s personal relationship with books; all four examine the ways that stories form us, effect us, and define us. I'm planning to discuss them all this week, starting today with The Child That Books Built.

I first read Spufford's book in 2002, the year of its original publication, and what struck me then was the unusual nature of its composition: childhood memoir mixed into literary and publishing history, with digression into cognitive science and child psychology in relation to story. In the intervening years, writers of memoir have expanded the form in so many ways that the structure of Spufford's book has lost its radical edge; I find that I have to remind myself that his memoir was a pioneering text. That said, it is still a cracking good read. Spufford is roughly the same generation I am and grew up with many of the same children's books on his shelves. He also has a taste for fantasy, and discusses the genre with knowledge and love. Although his writing on fairy tales relies too much (for this reader) on the disputed psychoanalytic theories of Bruno Bettleheim, his passion for all things magical wins me over nonethless, along with his poignant exploration of a childhood in which finding doors into other worlds was merciful and necessary.

I first read Spufford's book in 2002, the year of its original publication, and what struck me then was the unusual nature of its composition: childhood memoir mixed into literary and publishing history, with digression into cognitive science and child psychology in relation to story. In the intervening years, writers of memoir have expanded the form in so many ways that the structure of Spufford's book has lost its radical edge; I find that I have to remind myself that his memoir was a pioneering text. That said, it is still a cracking good read. Spufford is roughly the same generation I am and grew up with many of the same children's books on his shelves. He also has a taste for fantasy, and discusses the genre with knowledge and love. Although his writing on fairy tales relies too much (for this reader) on the disputed psychoanalytic theories of Bruno Bettleheim, his passion for all things magical wins me over nonethless, along with his poignant exploration of a childhood in which finding doors into other worlds was merciful and necessary.

Here's a passage from Spufford's introduction to give you a sense of the book as a whole:

"I began my reading in a kind of hopeful springtime for children's writing. I was born in 1964, so I grew up in a golden age comparable to the present heyday of J.K. Rowling and Philip Pullman, or to the great Edwardian decade when E. Nesbit, Kipling, and Kenneth Graham were all publishing at once. An equally amazing generation of talent was at work as the 1960s ended and the 1970s began. William Mayne was making dialogue sing; Peter Dickinson was writing the Changes trilogy; Alan Garner was reintroducting myth into the bloodstream of daily life; Jill Paton Walsh was showing that children's perceptions could be just as angular and uncompromising as adults; Joan Aiken had begun her Dido Twite series of comic fantasies; Penelope Farmer was being unearthly with Charlotte Sometimes; Diana Wynne Jones's gift for wild invention was hitting its stride; Rosemary Sutcliffe was just adding the final uprights to her colonnade of Romano-British historical novels; Leon Garfield was reinventing the 18th century as a scene for inky Gothic intrigue. The list went on, and on, and on. There was activity everywhere, a new potential classic every few months.

"Unifying this lucky concurrence of good books, and making them seem for a while like contributions to a single intelligible project, was a kind of temporary cultural consensus: a consensus both about what children were and about where we all were in history. Dr. Spock's great manual for liberal, middle-class child-rearing had come out at the beginning of the Sixties, and had helped deconstruct the last lingering remnants of the idea that a child was clay to be molded by a benevolent adult authority. The new orthodoxy took it for granted that a child was a resourceful individual, neither ickily good nor reeking of original sin. And the wider world was seen as a place in which a permanent step forward toward enlightenment had taken place as well. The books my generation were offered took it for granted that poverty, disease and prejudice essential belonged in the past. Postward society had ended them.

"As the 1970s went on, these assumptions would lose their credibility. Gender roles were about to be shaken up; the voices that a white, liberal consensus consigned to the margins of consciousness were about to be asserted as hostile witnesses to its nature. People were about to lose their certainty that liberal solutions worked. Evil would revert to being an unsolved problem. But it hadn't happened yet; and till it did, the collective gaze of children's stories swept confidently across past and future, and across all international varieties of the progressive, orange-juice-drinking present, from Australia to Sweden, from Holland to the broad, clean suburbs of America.

"For me, walking up the road aged seven or eight to spend my money on a paperback, the outward sign of this unity was Puffin Books. In Britain, almost everything written for children passed into the one paperback imprint. On the shelves of the children's section in the bookshop, practically all the stock would be identically neat soft-covered octavos, in different colors, with different cover art, but always with the same sans serif type on the spine, and the same little logo of an upstanding puffin. Everything cost about the same. For 17p -- then 25p and then 40p as the 1970s inflation took hold -- you could have any one of the new books, or any of the children's classics, from the old ones like The Wind in the Willows or Alice to the new ones that were only a couple of decades into their classichood, like the Narnia books (C.S. Lewis had died the year before I was born, most unfairly making sure I would never meet him).

"If you were a reading child in the UK in the Sixties or Seventies, you too probably remember how securely Puffins seemed, with the long, trust-worthy descriptions of the story inside the front cover, always written by the same arbiter, the Puffin editor Kaye Webb, and their astonishingly precise recommendation to 'girls of eleven and above, and sensitive boys.' It was as if Puffin were part of the administration of the world. They were the department of the welfare state responsible for the distribution of narrative. And their reach seemed universal: not just the really good books you were going to remember forever, but the nearly good ones too and the completely forgettable ones that at the time formed the wings of reading and spread them wide enough to enfold you in books on all sides."

A little later in the Introduction, Spufford lays out the premise of his memoir:

"I have gone back and read again the sequence of books that carried me from babyhood to the age of nineteen, from the first fragmentary stories I remember to the science fiction I was reading at the brink of adulthood. As I reread them, I tried to become again the reader I had been when I encountered each for the first time, wanting to know how my particular history, in my particular family, at that particular time, had ended up making me into the reader I am today. I made forays into child psychology, philosophy, and psychoanalysis, where I thought those things might tease out the implications of memory. With their help, the following chapters recount a path through the riches that were available to English children of the 1960s and 1970s, and onward into the reading of adolescence. It is the story (I hope) of the reading my whole generation of bookworms did; and it is the story of my own relationship with books; both. A pattern emerged, or a I drew it: a set of four stages in the development of that space inside where writing is welcomed and reading happens. What follows is more about books that it is about me, but nonetheless it is my inward autobiography, for the words we take into ourselves help to shape us. "

It is a premise Spufford amply fulfills in this moving and insightful volume.

Words: The passage above is from The Child That Books Built: A Life in Reading by Francis Spufford (Henry Holt & Co, 2002); all rights reserved by the author. Previous posts that discuss The Child That Books Built include "In the Forest of Stories" (2013) and "Built by Books" (2014). Pictures: The art is identified in the picture captions. (Run your cursor over the images to see them.) All rights reserved by the artists.

May 1, 2021

Up the May!

Happy Beltane to you all. The glorious picture is by David Wyatt, based on past May Day ceremonies here in Chagford (pre-pandemic). I long for such celebrations to return....

David, alas, has absconded to Wales, and we miss him terribly already.

Myth & Moor update

It's a three-day holiday weekend here in the UK. The hound and I will be back in the studio, and back to Myth & Moor, on Tuesday. I hope your long weekend is peaceful and creative.

April 30, 2021

Speaking with animals

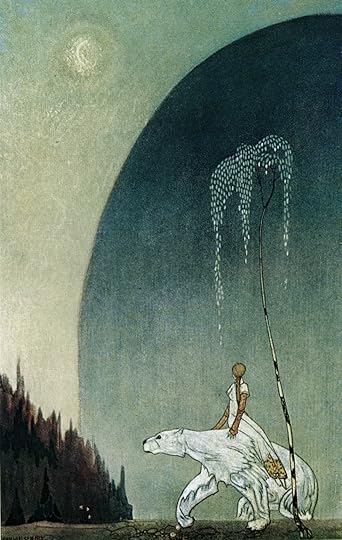

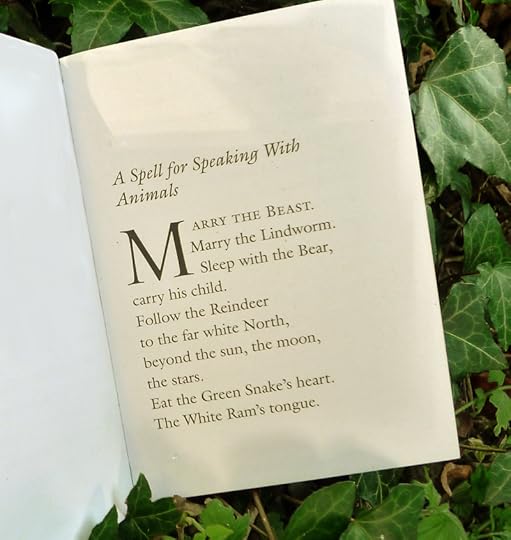

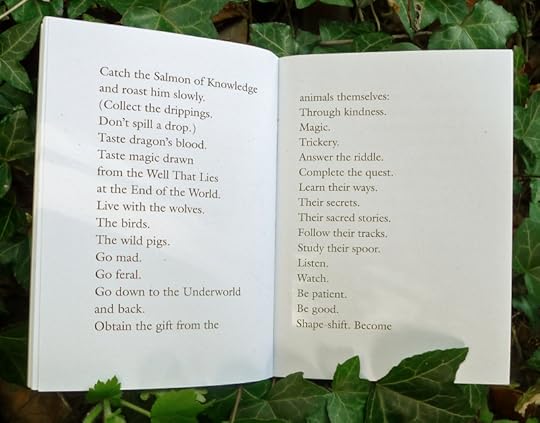

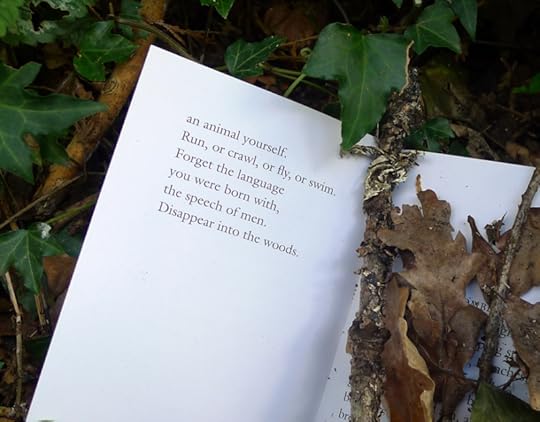

"A Spell for Speaking With Animals" is one of seven little pieces of mine published in Seven Little Tales (Hedgespoken Press, 2018). For an essay on the folklore behind the poem, see: "The Speech of Animals."

The art today is by four artists from the Golden Age of Book Illustration: East of the Sun, West of the Moon by Kay Nielsen (Danish, 1886-1957), Brother and Sister by Edmund Dulac (French/British, 1882-1953), The Lady and the Lion by Arthur Rackham (British, 1867-1939), and Poor Little Bear by John Bauer (Swedish, 1882-1918).

April 29, 2021

The broader conversation

Today, another passage from David Abram's Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology. Like Robin Wall Kimmerer (in last Thursday's post), David argues for a "language of animacy" to better reflect the interrelation between us and the natural world. Our conception of language as a purely human gift is much too limited, he says:

"All things have the capacity for speech -- all beings have the ability to communicate something of themselves to other beings. Indeed, what is perception if not the experience of this gregarious, communicative power of things, wherein even ostensibly 'inert' objects radiate out of themselves, conveying their shapes, hues, and rhythms to other beings and to us, influencing and informing our breathing bodies though we stand far apart from those things? Not just animals and plants, then, but tumbling waterfalls and dry riverbeds, gusts of wind, compost piles and cumulous clouds....Our own chatter erupts in response to the abundant articulations of the world: human speech is simply our part of a much broader conversation.

"It follows that myriad things are also listening, or attending to various signs and gestures around them. Indeed, when we are at ease in our animal flesh, we will sometimes feel that we are being listened to, or sensed, by earthly surroundings. And so we take deeper care with our speaking, mindful that our sounds may carry more than a merely human meaning and resonance. This care -- this full-bodied alertness -- is the ancient ancestral source of all word magic. It is the practice of attention to the uncanny power that lives in our spoken phrases to touch and sometimes transform the tenor of the world's unfolding."

The sense of inhabiting an articulate landscape, David notes,

"is common to indigenous, oral people on every continent. Like tribal people I've lived with elsewhere, most of my Pueblo friends here in the [American] Southwest are curiously taciturn and reserved when it comes to verbal speech. (When I'm with them I become painfully aware of how prolix I can be, prattling on about this and that for minutes on end.) Their reticence is not due to any lack of facility with English, for when they do speak their phrases have an uncommon precision and potency. It is a consequence, rather, of their habitual expectation that spoken words are heard, or sensed, by the other presences that surround. They talk, then, only when they have good reason to, choosing their words with great care so as not to offend, or insult, the other beings that might be listening....

"Few of us today feel any such constraints in our speaking. Human language, for us moderns, has swung in on itself, turning its back on the beings around us. Language is a human property, suitable only for communication with other persons. We talk to people; we do not talk to the ground underfoot. We've largely forgotten the incantatory and invocational use of speech as a way of bringing ourselves into deeper rapport with the beings around us, or of calling the living land into resonance with us. It is a power we still brush up against whenever we use our words to bless or to curse, or to charm someone we're drawn to. But we wield such eloquence only to sway other people, so we miss the greater magnetism, the gravitational power that lies within such speech. The beaver gliding across the pond, the fungus gripping a thick tree trunk, a boulder shattered by its tumble down a cliff or the rain splashing upon those granite fragments -- we talk about such beings, about the weather and the weathered stones, but we do not talk to them. Entranced by the denotive power of words to define, to order, to represent the things around us, we've overlooked the songful dimension of language so obvious to our oral ancestors. We've lost our ear for the music of language -- for the rhythmic, melodic layer of speech by which earthly things overhear us.

"How monotonous our speaking becomes when we speak only to ourselves! And how insulting to other beings -- to foraging blackbears and twisted old cypresses -- that no longer sense us talking to them, but only about them, as though they were not present in our world. As though the clear-cut mountainside and the flooding creek had no sensations of their own -- as though they had no flesh by which to feel the vibrations of our speaking. Small wonder that rivers and forests no longer compel our focus or our fierce devotion. For we talk about such entities only behind their backs, as though they were not participant in our lives.

"Yet if we no longer call out to the moon slipping between the clouds, or whisper to the spider setting the silken struts of her web, well, then the numerous powers of this world will no longer address us -- and if they still try, we will not likely hear them. They withdraw from our attentions, and soon refrain from encountering us when we're out wandering, or from visiting us in our dreams. We can no long avail ourselves of their perspectives or their guidance, and our human affairs suffer as a result. We become ever more forgetful in our relations with the rest of the biosphere, an obliviousness that cuts us off from ourselves, and from our deepest sources of sustenance."

For further reading on this subject, see these previous posts: "The Language of the Animate Earth" and "The Logos of the Land (living, working, and writing fantasy while rooted in place)." I recommend both of David's books: The Spell of the Sensuous and Becoming Animal, his Alliance for Wild Ethics website, and Robin Wall Kimmerer's lovely essay The Language of Nature.

Words: The passage quoted above is from Becoming Animal by David Abram (Pantheon Books, 2010). The poem in the picture captions is from Alive Together: New and Selected Poems by Lisel Mueller (Louisiana State University Press, 1996). All rights reserved by the authors.

Pictures: The photographs are of Dartmoor ponies grazing at the bottom of our hill. They are semi-wild, coming down from the moor to give birth in our valley every spring. I counted six foals among the herd -- some of them bold and some of them shy -- plus plenty of pregnant mares, so there are still more foals to come. The ink drawings are by British book artists Honor Charlotte Appleton (1879-1951) and Helen Stratton (1867-1971).

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 710 followers