Terri Windling's Blog, page 9

August 23, 2021

Tunes for a Monday Morning

Down by the river, down by the shore....

Above: "Rivermouth" by Rising Appalachia (sisters Leah Song and Chloe Smith), who draw inspiration from the folk, bluegrass, and blues of their native Georgia and New Orleans. "We've been working with Mississippi River, Gulf, and Klamath water protectors for years," they say, "and have branched out to form alliance with Waterkeepers around the world working towards preserving drinkable, fishable, swimmable water everywhere. We hope this song and this collaboration with WaterKeeper Alliance will strengthen awareness of water protection efforts worldwide and encourage us all to speak for the wild inside and out."

Below: "The Mississippi Woman" by Maz O'Conner, a singer/songwriter with Irish roots who grew up in the wilds of the English Lake District. The song, a waterside creation story, appeared on O'Conner's early album This Willowed Light (2014).

Above: "Riverside" by Agnes Obel, a Danish singer/songwriter based in Berlin. It appeared on her first album, Philharmonics (2010).

Below: "Swimming the Longest River" by singer/songwriter Olivia Chaney, who was born in Italy and grew up in Oxfordshire. The song appeared on her EP of the same name (2015). Her most recent solo album is Shelter (2018), and it's a beauty.

Above: "Blackwaterside," a traditional song with complicated roots, containing elements from Irish traveller songs, the English ballad "The False Young Man," and 19th century broadside ballads, popularised in the 20th century folk revival by Bert Jansch and Anne Briggs. It's sung here by Irish musician Cara Dillon, who has loved the song since she was young.

Below: "Clyde Water" (Child Ballad #216) performed by American singer/songwriter Anais Mitchell. This dark ballad originated in Scotland -- but it is part of the American folk tradition too, having been carried across the Atlantic by Scottish immigrants. The song appeared on Mitchell's fine album Child Ballads (2013), created with Jefferson Hammer. This performance was filmed for the Live From Here program in 2016.

Abobe: "Blue Heron" by American singer/songwriter and bluegrass musician Sarah Jarosz, performed on the Live from Here program in 2017. The song appeares on her new album The Blue Heron Suite (2021).

Below, to end with: "Rivers Run," an old favourite by Scottish singer/songwriter Karine Polwart, filmed in an improptu backstage performance with Steven Powart and Inge Thomson. The song appeared on her album This Earthly Spell (2008).

Painting above: "My Soul is an Enchanted Boat" by Walter Crane (1845-1915).

August 19, 2021

Alberto Manguel on The Wind in the Willows

From "Return to Arcadia" by Alberto Manguel:

"Several times, during a long life of reading, I���ve been tempted to write an autobiography based solely on the books that have counted for me. Someone once told me that it was customary for a Spanish nobleman to have his coat of arms engraved on his bedhead so that visitors might know who it was who lay in a sleep that might always be his last. Why then not be identified by my bedside favourites, which define and represent me better than any symbolic shield? If I ever indulged in such a vainglorious undertaking, a chapter, an early chapter, would be given over to The Wind in the Willows. I can���t remember when I first read The Wind in the Willows, since it is one of those books that seem to have been with me always, but it must have been very early on, when my room was in a cool, dark basement and the garden I played in boasted four tall palm trees and an old tortoise as their tutelary spirit. The geography of our books blends with the geography of our lives, and so, from the very beginning, Mole���s meadows and Rat���s river bank and Badger���s woods seeped into my private landscapes, imbuing the cities I lived in and the places I visited with the same feelings of delight and comfort and adventure that sprang from those much-turned pages. In this sense, the books we love become our cartography.

"In 1888, John Ruskin gave a name to the casual conjunction between physical nature and strong human emotions. ���All violent feelings���, he wrote, ���produce in us a falseness in all our impressions of external things, which I would generally characterize as the ���Pathetic Fallacy���.��� Kenneth Grahame magnificently ignored the warning. The landscape of Cookham Dene on the Thames (where he lived and which he translated into the world of Mole and Rat, Badger and Toad) is, emotionally, the source and not the result of a view of the world that cannot be distinguished from the world itself. There may have been a time when the bucolic English landscape lay ignored and untouched by words, but since the earliest English poets the reality of it lies to a far greater extent in the ways in which it has been described than in its mere material existence. No reader of The Wind in the Willows can ever see Cookham Dene for the first time. After the last page, we are all old inhabitants for whom every nook and cranny is as familiar as the stains and cracks on our bedroom ceiling. There is nothing false in these impressions."

"...The Wind in the Willows begins with a departure, and with a search and a discovery, but it soon achieves an overwhelming sense of peace and happy satisfaction, of untroubled familiarity. We are at home in Grahame���s book. But Grahame���s universe is not one of retirement or seclusion, of withdrawal from the world. On the contrary, it is one of time and space shared, of mirrored experience. From the very first pages, the reader discovers that The Wind in the Willows is a book about friendship, one of those English friendships that Borges once described by saying that they ���begin by precluding confidences and end by forgoing dialogue���. The theme of friendship runs through all our literatures. Like Achilles and Patroclus, David and Jonathan, Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, Ishmael and Queequeg, Sherlock Holmes and Watson, Rat and Mole reflect for each other discovered identities and contrasting views of the world. Each one asserts for the other the better, livelier part of his character; each encourages the other to be his finer, brighter self. Mole may be lost without Rat���s guidance but, without Mole���s adventurous spirit, Rat would remain withdrawn and far too removed from the world. Together they build Arcadia out of their common surroundings; pace Ruskin, their friendship defines the place that has defined them.

If The Wind in the Willows was a sounding-board for the places I lived in, it became, during my adolescence, also one for my relationships, and I remember wanting to live in a world with absolute friends like Rat and Mole. Not all friendships, I discovered, are of the same kind. While Rat and Mole���s bonds are unimpeachably solid, their relationship equally balanced and unquestioned (and I was fortunate enough to have a couple of friendships of that particular kind), their relationship with Badger is more formal, more distanced ��� since we are in England, land of castes and classes, and Badger holds a social position that requires a respectful deference from others. (Of the Badger sort, too, I found friends whom I loved dearly but with whom I always had to tread carefully, not wanting to be considered overbearing or unworthy.)

"With Toad, the relationship is more troubling. Rat and Mole love Toad and care for him, and assist him almost beyond the obligations of affection, in spite of the justified exasperation he provokes in them. He, on the other hand, is far less generous and obliging, calling on them only when in need or merely to show off. (Friends like Toad I also had, and these were the most difficult to please, the hardest to keep on loving, the ones that, over and over again, made me want to break up the relationship; but then they���d ask for help once more and once more I���d forgive them.)

"Toad is the reckless adventurer, the loner, the eternal adolescent. Mole and Rat begin the book in an adolescent spirit but grow in wisdom as they grow in experience; for Toad every outing is a never-ending return to the same whimsical deeds and the same irresponsible exploits. If we, the readers, love Toad (though I don���t) we love him as spectators; we love his clownish performance on a stage of his own devising and follow his misadventures as we follow those of a charming rogue.

"But Mole and Rat, and even Badger, we love as our fellow creatures, equal to us in joy and in suffering. Badger is everyone���s older brother; Rat and Mole, the friends who walk together and mature together in their friendship. They are our contemporaries, reborn with every new generation. We feel for their misfortunes and rejoice in their triumphs as we feel and rejoice for our nearest and dearest. During my late childhood and adolescence, their companionship was for me the model relationship, and I longed to share their d��jeuners sur l���herbe, and to be part of their easy complicit�� as other readers long for the love of Mathilde or the adventurous travels of Sinbad.

"The Wind in the Willows cannot be classed as a work of pure fantasy. Grahame succeeds in making his creatures utterly believable to us. The menageries of Aesop or La Fontaine, G��nter Grass or Colette, Orwell or Kipling, have at least one paw in a symbolic (or worse, allegorical) world; Grahame���s beasts are of flesh, fur and blood, and their human qualities mysteriously do not diminish, but enhance, their animal natures. As I���ve already said, with every rereading The Wind in the Willows lends texture and meaning to my experience of life; with each familiar unfolding of its story, I experience a new happiness. This is because The Wind in the Willows is a magical book. Something in its pages re-enchants the world, makes it once again wonderfully mysterious."

Words: The passage quoted above is from "Return to Arcadia" by Alberto Manguel, published in Slightly Foxed (Issue 34, Summer 2012). The poem in the picture captions is from Poetry (July/August 2009). All rights reserved by the authors.

Pictures: The art above (from top to bottom) is "Ratty and Mole" by Inga Moore, "Mole" by Ernest Shepard, "Ratty and Mole on the River" by Inga Moore, "The Riverside Picnic" by Arthur Rackham, "Toad and Mole" by Chris Dunn, "Mole's House" and "Lounging About" by Chris Dunn, "Mole and Ratty" by Inga Moore. All rights reserved by the artists.

Water, Wild and Sacred

For this week's Folklore Thursday theme of wells and rivers....

On a bright, clear morning some years ago, during the long, lovely days leading up to summer solstice, Wendy Froud and I drove through the lanes to the village of Callington in Cornwall (the county just to the west of Devon). We parked at the edge of a farmyard and followed what was then an overgrown footpath to Dupath Well (originally "Theu Path" Well)...a deeply magical place buried in the green of the Cornish countryside.

Like other holy wells in Devon and Cornwall, the spring that runs through Dupath Well is believed to have been a sacred site to Celtic peoples in the distant past, its older use now overlaid with a gloss of Christian legendry. At one time, this spring may have sat in a woodland grove of oak, rowan and thorn ��� trees sacred to the island's indigenous religions. In 1510, a group of Augustinian monks claimed the Dupath site for their own use, enclosing the spring in a small well house made out of rough-hewn granite. This was a common fate for many of the ancient pagan sites in the West Country. Unable to dissuade the local people from visiting their sacred places in nature, Christian authorities simply took them over, building churches where standing stones once stood and baptisteries over sacred springs, cutting down ceremonial groves and putting woodhenges to the torch. There are many, many wells like Dupath Well, scattered all over the West Country --- some of them covered and some still in use -- often named now for the Saints and associated with their miraculous lives. But scratch the surface of these legends and the palimpsests of older tales emerge: stories of fairies and piskies, the knights of King Arthur, and the old gods of the land.

Like other holy wells in Devon and Cornwall, the spring that runs through Dupath Well is believed to have been a sacred site to Celtic peoples in the distant past, its older use now overlaid with a gloss of Christian legendry. At one time, this spring may have sat in a woodland grove of oak, rowan and thorn ��� trees sacred to the island's indigenous religions. In 1510, a group of Augustinian monks claimed the Dupath site for their own use, enclosing the spring in a small well house made out of rough-hewn granite. This was a common fate for many of the ancient pagan sites in the West Country. Unable to dissuade the local people from visiting their sacred places in nature, Christian authorities simply took them over, building churches where standing stones once stood and baptisteries over sacred springs, cutting down ceremonial groves and putting woodhenges to the torch. There are many, many wells like Dupath Well, scattered all over the West Country --- some of them covered and some still in use -- often named now for the Saints and associated with their miraculous lives. But scratch the surface of these legends and the palimpsests of older tales emerge: stories of fairies and piskies, the knights of King Arthur, and the old gods of the land.

Inside the tiny, chapel-like building erected over Dupath Well, the water pools in a shallow trough carved from a single granite slab. The air is thick, heavy with shadows, and with the ghosts, perhaps, of men and women drawn to this spot for many centuries. The stones are worn where they once knelt and prayed to the Virgin Mary, or to the Lady of the Waters. That day, on the bottom of the trough lay a handful of copper coins, a modern custom of making wishes that is not so very different from the older practice of throwing pins (associated with women's labor and magic) into a spring to ask for the water spirit's blessing. Wendy placed a small offering of wildflowers by the water -- which, too, is an ancient practice, recalling a time when it was the land itself our ancestors thanked for the gift of water, and of life itself.

Today, with clean water piped directly into our homes and largely taken for granted, it takes a leap of imagination to consider how precious water would have been to those who fetched it daily from the riverside or village well. Deeply dependent on good local water sources, it's only natural that our ancestors would have revered those places where pure, life-sustaining water emerged like magic from the depths of the earth. Water plays a central role in myth, folk tales, fairy lore, and sacred stories not only here in the rain-soaked British Isles but all around the globe -- particularly, of course, in arid lands where the gift of water is most precious.

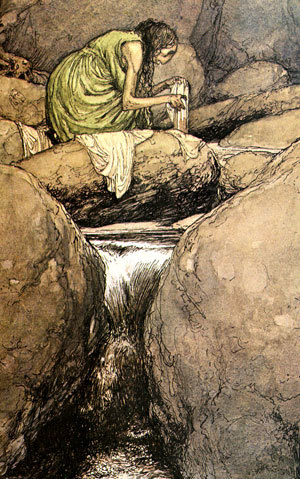

Many cultures associate water with women: with the Goddess, or with several goddesses, or a variety of female nature spirits. The !Kung of Botswana, for example, attribute the mythic origin of water to women, granting all women special power over water in all its form. All-mother, in an Aboriginal myth from northern Australia, arrived from the sea in the form of a rainbow serpent with children (the Ancestors) inside her. It was All-mother who made water for the Ancestors by urinating on the land, creating lakes, rivers and water holes to quench their thirst. The "living water" (running water) of springs and natural fountains is particularly associated in ancient mythological systems with women, fertility and childbirth. Greek wells and fountains were sacred to various goddesses and had miraculous powers ��� such as the fountain at Kanathos, in which Hera regained her virginity each year. Greek springs were the haunts of water nymphs, elemental spirits shaped like lovely young girls. (The original meaning of the Greek word for spring was "nubile maiden.") In Teutonic myth, the wild wood-wife (a kind of forest fairy) who loves the hero Wolfdietrich is transformed into a human girl when she's baptized in a sacred fountain. The Norse god Odin seeks wisdom and cunning from the fountain of the nature spirit Mimir; he sacrifices one of his eyes in exchange for a few precious sips of the water. In Celtic legend, the salmon of knowledge swims in a sacred spring or pool under the shade of a hazel tree; the falling hazelnuts contain all the wisdom of the world, swallowed by the fish.

Many cultures associate water with women: with the Goddess, or with several goddesses, or a variety of female nature spirits. The !Kung of Botswana, for example, attribute the mythic origin of water to women, granting all women special power over water in all its form. All-mother, in an Aboriginal myth from northern Australia, arrived from the sea in the form of a rainbow serpent with children (the Ancestors) inside her. It was All-mother who made water for the Ancestors by urinating on the land, creating lakes, rivers and water holes to quench their thirst. The "living water" (running water) of springs and natural fountains is particularly associated in ancient mythological systems with women, fertility and childbirth. Greek wells and fountains were sacred to various goddesses and had miraculous powers ��� such as the fountain at Kanathos, in which Hera regained her virginity each year. Greek springs were the haunts of water nymphs, elemental spirits shaped like lovely young girls. (The original meaning of the Greek word for spring was "nubile maiden.") In Teutonic myth, the wild wood-wife (a kind of forest fairy) who loves the hero Wolfdietrich is transformed into a human girl when she's baptized in a sacred fountain. The Norse god Odin seeks wisdom and cunning from the fountain of the nature spirit Mimir; he sacrifices one of his eyes in exchange for a few precious sips of the water. In Celtic legend, the salmon of knowledge swims in a sacred spring or pool under the shade of a hazel tree; the falling hazelnuts contain all the wisdom of the world, swallowed by the fish.

Ritual washing in water, or immersion in a pool, has been part of various religious systems since the dawn of time. The priests of ancient Egypt washed themselves in water twice each day and twice each night; in Siberia, ritual washing of the body ��� accompanied by certain chants and prayers ��� was (and still is) a vital part of shamanic practices. In Hindu, ghats are traditional sites for public ritual bathing, an act by which one achieves both physical and spiritual purification. In strict Jewish household, hands must be washed before saying prayers and before any meal including bread; in Islam, mosques provide water for the faithful to wash before each of the five daily prayers. In the Christian tradition, baptism is described by St. Paul as "a ritual death and rebirth which simulates the death and resurrection of Christ." According to mythologist Mircea Eliade, "Immersion in water symbolizes a return to the pre-formal, a total regeneration, a new birth, for immersion means a dissolution of forms, a reintegration into the formlessness of pre-existence; and emerging from the water is a repetition of the act of creation in which form was first expressed."

The idea of regeneration through water is echoed in tales around the world about fountains and springs with miraculous powers. Indigenous stories in Puerto Rico, Cuba, and Hispaniola all described a magical Fountain of Youth, located somewhere in the lands to the north. So pervasive were these stories that in the 16th century the Spanish conquistador Ponce de Leon actually set out to find it once and for all, equipping three ships at his own expense. He found Florida instead.

One Native American story describes a Fountain of Youth created by two hawks in the nether-world between heaven and earth -- but this fountain brings grief as those who drink of it outlive their children and friends, and eventually it's destroyed. In Japanese legends, the white and yellow leaves of the wild chrysanthemum confer blessings from Kiku-Jido, the chrysanthemum boy who dwells by the Fountain of Youth. These leaves are ceremonially dipped in sake to assure good health and long life. In the Alexander  Romances, Alexander sets off to find the fabled Fountain of Life in the Land of Darkness beyond the setting sun. The prophet Khizr is Alexander���s guide, but the two take separate forks in the road. It is Khizr, not his master, who finds the fountain, drinks the water, and obtains knowledge of god. Khizr is still venerated in modern India, in both Hindu and Muslim traditions. In Muslim practices, Khizr is honored by lighting lamps and setting them on little boats afloat on rivers and ponds.

Romances, Alexander sets off to find the fabled Fountain of Life in the Land of Darkness beyond the setting sun. The prophet Khizr is Alexander���s guide, but the two take separate forks in the road. It is Khizr, not his master, who finds the fountain, drinks the water, and obtains knowledge of god. Khizr is still venerated in modern India, in both Hindu and Muslim traditions. In Muslim practices, Khizr is honored by lighting lamps and setting them on little boats afloat on rivers and ponds.

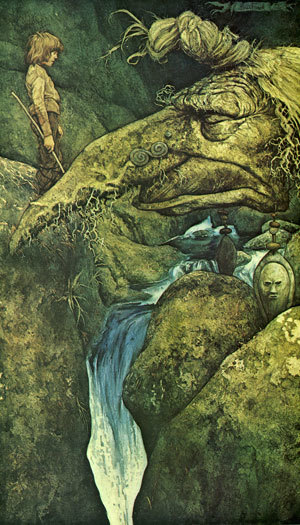

In fairy tales, heroes are sent on long journeys to the Well at the End of the World, or to springs in the dark heart of the forest, ordered to retrieve a vial of the Water of Life, usually for a wicked fairy. A few drops from this water confers beauty, wisdom, fluency in the language of animals, and/or immortality. Sometimes the heroes partake of the water themselves, deliberately or accidently, and sometimes they bring the vial back intact. The fairy drinks, expecting to gain more power, and is cleansed of her wickedness instead. Other wells in fairy tales contain enchanted frogs, talking heads, imprisoned trolls, and fearsome looking snakes who turn out to be wise and good. But beware of old women who linger by the well, for they are usually fairies in disguise, and cranky. You've been warned.

To the ancient peoples of the West Country, certain waters were deemed to have healing properties and thus were under divine protection. The famous hot spring at Bath in Somerset (the county just to the east of Devon) was dedicated to a Celtic goddess local to the place. When the Romans took the hot springs over and built the temple complex we know today, Sulis was linked with their goddess Minvera to become Sulis Minerva. Chalice Well in Glastonbury, also in Someset, is reputed to be among the oldest of continually used holy wells in all of Europe; archaeological evidence suggests it has been a sacred site for at least two thousands years. Even the standing stones and circles of Britain are generally found near wells or running water.

As Christianity spread, more and more springs were built over with chapels and well houses, and the groves around them removed. Devon and Cornwall, in particular, were deemed to be troublesome bastions of paganism. In the 5th century, a canon issued by the Second Council of Arles stated: "If in the territory of a bishop infidels light torches or venerate trees, fountains, or stones, and he neglects to abolish this usage, he must know that he is guilty of sacrilege." Yet pagan beliefs proved harder to eradicate than the sites themselves, for in the 10th, 11th and 12th centuries a stream of edicts were issued from church authorities denouncing the worship of "the sun or the moon, fire or flood, wells or stones or any kind of forest tree."

Over time, however, pagan and Christian practices slowly blended together, and holy wells all over Great Britain were celebrated with Christian festivals that fell on the old pagan holy days. On the Isle of Man, for example, holy wells are frequented on August 1st, a day sacred to the Celtic god Lugh. August 1st is Lammas in the Christian calendar, but the older name for the holiday, Lugnasad, was still in use on the island until late in the 19th century. In Scotland, the well at Loch Maree is dedicated to St. Malrubha but its annual rites -- involving the sacrifice of a bull, an offering of milk poured on the ground, and coins driven into the bark of a tree -- are pagan in origin. The custom of "well dressing" is another Christian rite with pagan roots. During these ceremonies (still practiced in Derbyshire and other parts of Britain), village wells are decorated with pictures made of flowers, leaves, seeds, feathers and other natural objects. In centuries past, the wells were "dressed" to thank the patron spirit of the well and request good water for the year to come; now the ceremonies generally take place on Ascension Day, and the pictures created to dress the wells are biblical in nature.

The Christian tales attached to springs and wells are often as magical as any to be found in Celtic lore. Wells were said to have sprung up where saints were beheaded or had fought off dragons, or where the Virgin Mary appeared and left small footprints pressed into the stone. Over the Channel in Brittany (which has linguistic and mythic connections to the West Country) "granny wells" dedicated to St. Anne (so called bcause Anne was the mother of Mary, and therefore the grandmother of Christ) were attributed with particular powers concerning fertility and childbirth. According to one old Breton legend, St. Anne settled there in her old age, where she was visited by Christ before she died. She asked him for a holy well to help the sick people of the region; he struck the ground three times, and the well of St. Anne-e-la-Palue was created.

The Christian tales attached to springs and wells are often as magical as any to be found in Celtic lore. Wells were said to have sprung up where saints were beheaded or had fought off dragons, or where the Virgin Mary appeared and left small footprints pressed into the stone. Over the Channel in Brittany (which has linguistic and mythic connections to the West Country) "granny wells" dedicated to St. Anne (so called bcause Anne was the mother of Mary, and therefore the grandmother of Christ) were attributed with particular powers concerning fertility and childbirth. According to one old Breton legend, St. Anne settled there in her old age, where she was visited by Christ before she died. She asked him for a holy well to help the sick people of the region; he struck the ground three times, and the well of St. Anne-e-la-Palue was created.

Up until the 19th century, the holy wells of the West Country were still considered to have miraculous properties, and were visited by those seeking cures for disease, disability, or mental illness. Some wells were famous for offering prophetic information ��� generally determined through the movements of the water, or leaves floating upon the water, or fish swimming in the depths. At some wells, sacred water was drunk from circular cups carved out of animal bone (an echo of the cups carved out of human skulls by the ancient Celts). Pins (usually bent), coins, bits of metal, and flowers are common well offerings; and rags (called clouties) are tied to nearby trees, the cloth representing disease or misfortune left behind as one departs. (For more on cloutie trees, go here.)

Some wells, known as cursing wells, were rather less beneficent. The curses were made by dropping special cursing stones into the well, or the victim's name written on a piece of paper, or a wax effigy. At the famous cursing well of Ffynnon Elian, up in Wales, one could arrange for a curse by paying the well's  guardian a fee to perform an elaborate cursing ritual. A curse could also be removed at this same well, for a somewhat larger fee.

guardian a fee to perform an elaborate cursing ritual. A curse could also be removed at this same well, for a somewhat larger fee.

In the mid-19th century, Thomas Quiller-Couch (father of Sir Arthur Thomas Quiller-Couch) became interested in the history of holy wells; he spent much of his life wandering the wilds of his native Cornwall seeking them out. Extensive notes on this project were discovered among his papers after his death, and in 1884 The Ancient and Holy Wells of Cornwall was published by the antiquarian's daughters, Mabel and Lillian. More recently, folklorist Paul Broadhurst re-visited the sites documented by Quiller Couch, and in 1991 he published Secret Shrines: In Search of the Old Holy Wells of Cornwall, an informative guide to the many wells still to be found in the Cornish countryside.

In addition to sites dedicated to Celtic goddesses and Christian saints, Broadhurst discovered crumbling old wells half-buried in ivy, bracken and briars inhabited by spirits somewhat less exalted: the piskies (fairies) of Cornish folklore. Wells under the protection of the piskies are not wells to be trifled with, for the piskies will take their revenge on any who dare to disturb their homes. A farmer decided to move the stone basin at St. Nun's Well (also known as Piskey's Well), with the intention of using it as a water trough for his pigs. He chained the stone to two oxen and pulled it the top of a steep hill ��� whereupon the stone broke free of the chains, rolled downhill, made a sharp turn right, and settled back into its place. One of the ox died on the spot, and the farmer was struck lame.

All running water, not just spring water, can prove to be the haunt of fairies, for crossing over (or through) running water is one of the ways to enter their realm. Here in Devon and Cornwall, one still finds country folk who avoid running water by dusk or dark -- for the spirits who inhabit water can be troublesome, even deadly. The water spirit of the River Dart, for instance, is believed to demand sacrificial drownings, leading  to the well-known local rhyme: "Dart, Dart, cruel Dart, every year she claims a heart." The water-wraithes up in Scotland are thin, ragged, and invariably dressed in green, haunting riversides by night to lead travelers to a watery death. In the Border Country between Scotland and England, the Washer by the Ford wails as she washes the grave clothes of those who are about to die -- similar to the dreaded Bean-Sidhe (Banshee) of Irish legends. The Bean-nighe, found in both Highland and Irish lore, is somewhat lesser known: a dangerous little fairy with ragged green clothes and webbed red feet. If you can get between the Bean-nighe and her water source, however, she is obliged to grant three wishes and refrain from doing harm. Jenny Greenteeth is a river hag also known as Peg Powler or a grindylow. She's an English fairy who specializes in dragging children ino stagnant pools. The Welsh water-leaper, called Llamhigyn Y Dwr, is a toad-like fairy who delights in tangling fishing lines and devouring any sheep who fall into the river. The fideal is a fairy who haunts lonely pools and hides herself in the grasses by the water; the glaistig, half-woman and half-goat, tends to lurk in the dark of caves behind waterfalls. Both are native to Scotland, but are known to roam as far south as Wales. The loireag of the Hebrides is a gentler breed of water fairy, although, as a connoisseur of music, even she can prove dangerous to those who dare to sing out of tune. In Ireland, the Lady of the Lake bestows blessings and good weather to those who seek her favor; in some towns she is still celebrated (or propitiated) at mid-summer festivals. Her name recalls the Lady of the Lake of Arthurian lore, who gave King Arthur his sword and now guards his body as he sleeps in Avalon.

to the well-known local rhyme: "Dart, Dart, cruel Dart, every year she claims a heart." The water-wraithes up in Scotland are thin, ragged, and invariably dressed in green, haunting riversides by night to lead travelers to a watery death. In the Border Country between Scotland and England, the Washer by the Ford wails as she washes the grave clothes of those who are about to die -- similar to the dreaded Bean-Sidhe (Banshee) of Irish legends. The Bean-nighe, found in both Highland and Irish lore, is somewhat lesser known: a dangerous little fairy with ragged green clothes and webbed red feet. If you can get between the Bean-nighe and her water source, however, she is obliged to grant three wishes and refrain from doing harm. Jenny Greenteeth is a river hag also known as Peg Powler or a grindylow. She's an English fairy who specializes in dragging children ino stagnant pools. The Welsh water-leaper, called Llamhigyn Y Dwr, is a toad-like fairy who delights in tangling fishing lines and devouring any sheep who fall into the river. The fideal is a fairy who haunts lonely pools and hides herself in the grasses by the water; the glaistig, half-woman and half-goat, tends to lurk in the dark of caves behind waterfalls. Both are native to Scotland, but are known to roam as far south as Wales. The loireag of the Hebrides is a gentler breed of water fairy, although, as a connoisseur of music, even she can prove dangerous to those who dare to sing out of tune. In Ireland, the Lady of the Lake bestows blessings and good weather to those who seek her favor; in some towns she is still celebrated (or propitiated) at mid-summer festivals. Her name recalls the Lady of the Lake of Arthurian lore, who gave King Arthur his sword and now guards his body as he sleeps in Avalon.

Chalice Well in Glastonbury is one of several sites where the Holy Grail is reputed to be hidden. At the foot of ancient Glastonbury Tor is a lovely garden where one can drink the red-tinged water of well ��� colored, according to legend, by the blood of Christ carried in the Grail. Although the well's association with Arthur may be (as some Arthurian scholars suggest) a legend of recent vintage, archaeological excavations in the 1960s established the site's antiquity ��� and the place manages to retain a tranquil, mystical atmosphere despite now doing dual duty as a sacred site and a tourist attraction. One often finds small offerings in the circle around the well's heavy lid: flowers, feathers, stones, small bits of cloth tied to a near-by tree . . . the old pagan ways still quietly practiced by many people to this day.

In North America, numerous springs, wells, and pools are sacred to land's First Nations. In such holy places one also finds offerings similar to those by Chalice Well: feathers, flowers, stones, sage, tobacco, small carved animal forms, scraps of red cloth tied to trees, and other tokens of prayer. The Native American sweat-lodge ceremony uses water sprinkled over red-hot rocks to create the steam that is called the "breath of life"; the lodge itself is the womb of mother earth in which one is washed clean, purified and spiritually reborn. In Native American Church ceremonies, a pail of Morning Water is traditionally carried and prayed over by a woman before being sent sun-wise around the circle to be shared by all. Water is sacred through its absence in the four-day Sundance ceremony, or the ritual of Crying for a Vision; after four days without water (or food), the first drop on the tongue is a potent reminder to be thankful for this precious gift from mother earth.

Some years ago at the Mythic Journeys conference in Atlanta, Tom Blue Wolf of the Eastern Lower Muscogee Creek Nation spoke of the need to cherish the wild waters of our lands -- particularly now, as water tables world-wide diminish at alarming rates. ���Once upon a time,��� he said, ���the Chattahoochee River was known to the people here as the source of life. Every morning we would go to the water and fill ourselves with gratitude, and thank the Creator for giving us this source of life. We would honor it throughout the day. At that time, water was known as the Long Man. It came from a place that has no beginning, and goes to a place that has no end. But now, for the first time in the history of our people, we can see the end of water.���

Some years ago at the Mythic Journeys conference in Atlanta, Tom Blue Wolf of the Eastern Lower Muscogee Creek Nation spoke of the need to cherish the wild waters of our lands -- particularly now, as water tables world-wide diminish at alarming rates. ���Once upon a time,��� he said, ���the Chattahoochee River was known to the people here as the source of life. Every morning we would go to the water and fill ourselves with gratitude, and thank the Creator for giving us this source of life. We would honor it throughout the day. At that time, water was known as the Long Man. It came from a place that has no beginning, and goes to a place that has no end. But now, for the first time in the history of our people, we can see the end of water.���

At the same conference, mythologist Michael Meade spoke of the ancient symbolism of water and its mythic role in our lives today. ���Of the elements (which some people count as four, and others count as five), water is the element for reconciliation. Water is the element of flow. When water goes missing, flow goes missing. The ancient Irish used to say that there are two suns in the world. One you see rise in the morning. The other is very deep in the earth, and it���s called the black sun or inner sun. It���s a hot fire in there; no one knows how hot. The earth is roughly seventy per cent water because of that hidden sun inside. When the water goes down, the earth heats up too much ��� part of the global warming that���s happening everywhere. It happens inside people also, because people are like the earth. People are seventy per cent water like the earth, and people have a hidden sun ��� or else we wouldn���t be ninety-six degrees when its forty degrees outside. Everyone in the world is burning, and the water in the body keeps that burning from becoming a fever. What happens literally also happens emotionally and spiritually, so when people forget how to carry water and how to use water to reconcile, you get an increasing amount of heated conflict, as we���re seeing around the world today. ���In many cultures it���s the elders who carry the water, because elders are the peace-bringers. When a culture can���t remember or imagine peace on its streets or how to negotiate peace, it means its elders have forgotten what to do, how to carry water.���

As an elder now myself, I try to remember these words and carry water with respect.

I'll give Margaret Atwood the last words today, from her mythic novel The Penelopiad. They are words that rustle like wind in my ears as Tilly and I follow the cold, clear stream winding through our own beloved piece of woods:

"Water does not resist. Water flows. When you plunge your hand into it, all you feel is a caress. Water is not a solid wall, it will not stop you. But water always goes where it wants to go, and nothing in the end can stand against it. Water is patient. Dripping water wears away a stone. Remember that, my child. Remember you are half water. If you can't go through an obstacle, go around it. Water does.���

The paintings above are: Wendy Froud as "Lady of the Waters" by Brian Froud, "Circe Invidiosa" & "The Danaides" by John William Waterhouse, a water faery by Brian Froud, a Bean-nighe by Alan Lee, "Arthur in Avalon" & "The Last Sleep of King Arthur" by Sir Edward Burne-Jones, and The River Teign (which flows through Chagford) by Brian Froud. The photographs of wells, springs, and baths above come from various British heritage sites. Please look in the picture captions for identifcation. (Run your cursor over the pictures to see the captions.) All rights reserved by the artists and photographers. The text for this post has been adapted from three previous articles of mine published in: Folkroots, The Journal of Mythic Arts, and Masaru Emoto's anthology, The Healing Power of Water.

August 18, 2021

Ursula Le Guin on imagination

In my reading life, I've been bouncing back and forth between fiction and memoir-tinged nonfiction lately, thinking about the difference between them (in terms of the writing craft), and about the tricksy place where the line between them falls. I was reminded of this passage from Words Are My Matter by Ursula K. Le Guin, and so I'll share them with you:

"In workshops on story writing, I've met many writers who want to work only with memoir, tell only their own story, their experience. Often they say. 'I can't make up stuff, that's too hard, but I can tell what happened.' It seems easier to them to take material directly from their experience than to use their experience as material for making up a story. They assume they can just write what happened.

"That appears reasonable, but actually, reproducing experience is a very tricky business requiring both artfulness and practice. You may find you don't know certain important facts or elements of the story you want to tell. Or the private experience so important to you may not be very interesting to others, requires skill to make it meaningful, moving, to the reader. Or, being about yourself, it gets all tangled up with ego, or begins to be falsified by wishful thinking. If you're honestly trying to tell what happened, you find facts are very obstinate things to deal with. But if you begin to fake them, to pretend things happened in a way that makes a nice neat story, you're misusing imagination. You're passing invention off as fact: which is, among children at least, called lying.

"Fiction is invention, but it is not lies. It moves on a different level of reality from either fact-finding or lying.

"I want to talk here about the difference between imagination and wishful thinking, because it's important both in writing and in living. Wishful thinking is thinking cut loose from reality, a self-indulgence that is often merely childish, but may be dangerous. Imagination, even in its wildest flights, is not detached from reality: imagination acknowledges reality, starts from it, and returns to enrich it. Don Quixote indulges his longing to be a knight till he loses touch with reality and makes an awful mess of his life. That's wishful thinking. Miguel Cervantes, by working out and telling the invented story of a man who wishes he were a knight, vastly increased our store of laughter and human understanding. That's imagination. Wishful thinking is Hitler's Thousand-Year Reich. Imagination is the Constitution of the United States.

"A failure to see the difference is in itself dangerous. If we assume that imagination has no connection with reality but is mere escapism, and therefore distrust it and repress it, it will be crippled, perverted, it will fall silent or speak untruth. The imagination, like any basic human capacity, needs exercise, discipline, training, in childhood and lifelong.

"One of the best exercises for the imagination, maybe the very best, is hearing, reading, and telling or writing made-up stories. Good inventions, however fanciful, have both congruity with reality and inner coherence. A story that's mere wish-fulfilling babble, or coercive preaching concealed in a narrative, lacks intellectual coherence and integrity: it isn't a whole thing, it can't stand up, it isn't true to itself.

"Learning to tell or read a story that is true to itself is about the best education a mind can have."

Words: The passage above is from "Making Up Stories," published in Words Are My Matter: Writings About Life & Books by Ursula K. Le Guin (Small Beer Press, 2016). The poem in the picture captions is from High Country (Sandstone Press, 2015). All rights reserved by the authors.

Pictures: A walk by the river near Belstone on Dartmoor, with Howard and the hound.

A river of words

I've been bouncing back and forth between fiction and memoir-tinged nonfiction lately, thinking about the difference between them (in terms of the writing craft), and I was reminded of this passage from Words Are My Matter by Ursula K. Le Guin:

"In workshops on story writing, I've met many writers who want to work only with memoir, tell only their own story, their experience. Often they say. 'I can't make up stuff, that's too hard, but I can tell what happened.' It seems easier to them to take material directly from their experience than to use their experience as material for making up a story. They assume they can just write what happened.

"That appears reasonable, but actually, reproducing experience is a very tricky business requiring both artfulness and practice. You may find you don't know certain important facts or elements of the story you want to tell. Or the private experience so important to you may not be very interesting to others, requires skill to make it meaningful, moving, to the reader. Or, being about yourself, it gets all tangled up with ego, or begins to be falsified by wishful thinking. If you're honestly trying to tell what happened, you find facts are very obstinate things to deal with. But if you begin to fake them, to pretend things happened in a way that makes a nice neat story, you're misusing imagination. You're passing invention off as fact: which is, among children at least, called lying.

"Fiction is invention, but it is not lies. It moves on a different level of reality from either fact-finding or lying.

"I want to talk here about the difference between imagination and wishful thinking, because it's important both in writing and in living. Wishful thinking is thinking cut loose from reality, a self-indulgence that is often merely childish, but may be dangerous. Imagination, even in its wildest flights, is not detached from reality: imagination acknowledges reality, starts from it, and returns to enrich it. Don Quixote indulges his longing to be a knight till he loses touch with reality and makes an awful mess of his life. That's wishful thinking. Miguel Cervantes, by working out and telling the invented story of a man who wishes he were a knight, vastly increased our store of laughter and human understanding. That's imagination. Wishful thinking is Hitler's Thousand-Year Reich. Imagination is the Constitution of the United States.

"A failure to see the difference is in itself dangerous. If we assume that imagination has no connection with reality but is mere escapism, and therefore distrust it and repress it, it will be crippled, perverted, it will fall silent or speak untruth. The imagination, like any basic human capacity, needs exercise, discipline, training, in childhood and lifelong.

"One of the best exercises for the imagination, maybe the very best, is hearing, reading, and telling or writing made-up stories. Good inventions, however fanciful, have both congruity with reality and inner coherence. A story that's mere wish-fulfilling babble, or coercive preaching concealed in a narrative, lacks intellectual coherence and integrity: it isn't a whole thing, it can't stand up, it isn't true to itself.

"Learning to tell or read a story that is true to itself is about the best education a mind can have."

Words: The passage above is from "Making Up Stories," published in Words Are My Matter: Writings About Life & Books by Ursula K. Le Guin (Small Beer Press, 2016). The poem in the picture captions is from High Country (Sandstone Press, 2015). All rights reserved by the authors. Pictures: A walk by the river near Belstone on Dartmoor, with Howard and the hound.

August 17, 2021

That's the way to do it: Punch & Judy

Howard is back on the Devon seafront this month performing traditional Punch & Judy puppet shows in Teignmouth, Dawlish, and other coastal towns. Though does this every summer with his pitch-partner Tony Lidington (a performer and academic specialising in historic British seaside entertainments), these live shows are particularly popular now after the long, dreary months of pandemic restrictions. This year, Tony and Howard initiated an apprenticeship programme to teach young drama students the arts of traditional outdoor theatre. They've been getting a lot of press attention -- which inevitably raises questions about Punch & Judy, its history, and its relevance to modern audiences. Here's a post I wrote about Howard and Mr. Punch that may answer some of those questions....

At the back of our garden, up against the woods, is the two-room cabin where Howard has his office and a small theatre studio. My own studio is not far away, so I often hear a variety of sounds drifting over the hedge between us: it might be accordion or mandolin practice one moment, lines declaimed from Shakespeare the next...or the odd "swazzle" voice of the classic English puppet Mr. Punch: a sound which initially sent Tilly into fits of barking until she finally figured out that it was just Howard at work.

Howard has loved Mr. Punch since his university days, when he wrote his thesis on the puppet's history -- so once he became a professional puppeteer he began work on his own Punch & Judy show. But then other theatre projects claimed his time, and the Punch puppets were all boxed away... until the morning I came downstairs to find them grinning at me from a chair.

For much of that summer, Howard's studio was transformed into a puppetry workshop. There were carpentry tools, lumber, and swathes of red-and-white striped cloth crowding the practice room; tiny puppet clothes hang from our washing line; and more and more puppets staring at me when I walked through our livingroom.

I confess I was never a big fan of Punch & Judy or of slap-stick comedy in general before I met Howard -- whose life has been devoted to the European form of masked theatre known as Commedia dell'Arte, which is very slapstick, and very funny, and which won me over with its mix of ridiculous pratfalls and sly, wry intelligence. Howard helped me to see the mythic roots of such comedy in Trickster tales and Dionysian revels, in the sacred anarchy of traditional carnaval and rural folk pageantry. As I learn more and more about the roots of comedy from Howard, I find myself fascinated by lines of connection between the various forms of mask/puppet theatre and folk use of these arts in ritual form: in the Jack-in-Greens and Obby Osses of England, in the ceremonial clowns of North America's indigenous peoples, and in other folk rites and sacred traditions all across Europe and around the globe.

The ritualized slapstick violence of Punch & Judy is problematic today, however, for we tend to "read" the story in a literal fashion, interpreting the action as domestic abuse, when it is best understood metaphorically, as the unleashing of childlike "naughtiness," mayhem, and gleeful anarchy. Mr. Punch is a Trickster figure: a manifestation of Trickster's sly delight in violating all social norms and constraints, brazenly knocking down every authority figure...which is precisely why children love him. The challenge for performers today is to craft a story that conveys this same archetypal spirit of contrariness and cheeky anarchy without tacitly condoning violence, domestic or otherwise, in the real world. Howard's re-telling of the Punch & Judy story treads this line carefully, without losing the glorious mayhem that gives children such delight. (See Emma Windsor's post on the subject on the Puppet Place News blog.)

The ritualized slapstick violence of Punch & Judy is problematic today, however, for we tend to "read" the story in a literal fashion, interpreting the action as domestic abuse, when it is best understood metaphorically, as the unleashing of childlike "naughtiness," mayhem, and gleeful anarchy. Mr. Punch is a Trickster figure: a manifestation of Trickster's sly delight in violating all social norms and constraints, brazenly knocking down every authority figure...which is precisely why children love him. The challenge for performers today is to craft a story that conveys this same archetypal spirit of contrariness and cheeky anarchy without tacitly condoning violence, domestic or otherwise, in the real world. Howard's re-telling of the Punch & Judy story treads this line carefully, without losing the glorious mayhem that gives children such delight. (See Emma Windsor's post on the subject on the Puppet Place News blog.)

"It was in the early 1990s," Howard recalls, "while I was working at Norwich Puppet Theatre, that I began to carve my own Mr. Punch. Later, at the Little Angel Theatre in London, I carved several of the other characters found in classic Punch & Judy shows. I'm a puppet director and performer, not a maker, but the P&J characters are fairly simple and I wanted to try my hand at making them myself -- working in the Little Angel workshop under the  eye of master carver Lyndie Wright. I made Judy, Joey, the Baby, the Policeman, the Devil...but I never finished the full set. Other theatre work intervened, and Punch went into a storage box. Years later, when I moved to Devon, the box disappeared into a dark corner of the attic.

eye of master carver Lyndie Wright. I made Judy, Joey, the Baby, the Policeman, the Devil...but I never finished the full set. Other theatre work intervened, and Punch went into a storage box. Years later, when I moved to Devon, the box disappeared into a dark corner of the attic.

"Then, in the spring of 2016, I attended an excellent Punch & Judy workshop at the Little Angel, run by Professor Glynn Edwards (aided and abetted by Professor Clive Chandler) -- and when I came home, I searched the attic and rescued Punch from the dust and cobwebs. I'd dreamed of performing a Punch & Judy show for a long, long time, and now I was determined to do it -- but I had to work slowly, between other jobs, and the process spread over another two years: first finishing the puppets, then building the booth, and finally developing and practicing the show.

"I was lucky to have some expert help. My mother, a retired theatre costume designer, made all of the puppets' clothes, and covered the booth in traditional candy-striped fabric. The booth has to be light and portable, quick to assemble and disassemble, and her clever design of the booth's fabric cover allows for easy removal. I used a simple wooden frame for the stage, until our friend David Wyatt -- a multi-award-winning book illustrator -- stepped in. David generously designed and painted the glorious sign that crowns the booth today.

"I then took my P&J booth on the road for trial performances in various public and private settings: learning the mechanics of the back-stage action, discovering all the ways that it could go wrong (in one show I swallowed the swazzle!), exploring each puppet's character and finding the rhythm and movement of the show.

"Highlights along the way included some wild off-grid performances with Hedgespoken Storytelling Theatre, birthday shows for Dark Crystal designer Brian Froud and fantasy novelist Delia Sherman, and two years' of performances at the Shambala Festival's Puppet Parlour. This summer I worked as the official Punch & Judy man for Teignmouth beach -- performing on a classic seafront pitch with Tony Liddington and his hilarious Flea Circus.

"I love contrary, naughty Mr. Punch, and the way he makes children scream with laughter, and plenty of adults as well. Despite all the entertainments on offer in our complex, fast-paced, digital world, these simple objects of cloth and wood, and a funny swazzle voice, can still create magic."

If you'd like to know more about the history of Punch & Judy, I recommend "That's the Way to Do It!" on the Victoria & Albert Museum website, curated to honor the show's 350th anniversary in 2012 -- a date based on the first known puppet play in England to contain a version of Mr. Punch, recorded by Samuel Pepys in 1662. He noted seeing it in Covent Garden, writes the V&A's curator,

"performed by the Italian puppet showman Pietro Gimonde from Bologna, otherwise known as Signor Bologna: 'Thence to see an Italian puppet play that is within the rayles there, which is very pretty, the best that ever I saw, and a great resort of gallants.'

"Bologna was one of many entertainers who came to England from the continent following the restoration of the monarchy in 1660. Unlike today���s Punch & Judy, performed with glove puppets in canvas booths with the audience outside, Bologna used marionettes -- puppets with rods to their heads and strings or wires to their limbs ��� and performed within a transportable wooden shed, and as such would have been quite a novelty. Pepys was so delighted by the show that he brought his wife to see it two weeks later, and in October 1662 Bologna was honoured with a royal command performance by Charles II at Whitehall, where a stage measuring 20ft by 18ft was set up for him in the Queen���s Guard Chamber. The king rewarded ���Signor Bologna, alias Pollicinella��� with a gold chain and medal, a gift worth ��25 then, or about ��3,000 today. Other Italian puppeteers appeared in London, and on 10 November 1662 Pepys took his wife to see another show in a booth at Charing Cross performing: 'the Italian motion, much after the nature of what I showed her at Covent Garden.'

"Pepys usually referred to the shows as Polichinello, a name relating to Punch���s roots in the Italian Commedia dell���Arte, where masked actors improvised comic knockabout plays around a number of stock characters, and Polichinello was the subversive, thuggish character whose Italian name Pulcinella or Pulliciniello may have developed from the word pulcino, or chicken, referring to the character���s beak-like mask and squeaky voice.

"Punch���s characteristic voice comes from the use of a reed retained at the back of the Punchman���s (or Professor's) mouth, calling for expert alternation of reed use when Punch is talking to other characters. In Britain the reed is called a swazzle, and in France a sifflet-pratique. Its most common Italian name was pivetta, but also sometimes strega, or witch, and franceschina, after Franchescina, one of Punch���s wives in the Commedia dell���Arte who had a voice like a witch. Swazzles are made of thin metal today, but bone or ivory were formerly used, each equally tricky to master and easy to swallow.

"Mr. Punch made himself thoroughly at home in Britain during the 18th century. His wife was the shrewish Dame Joan who made his life a misery, and his hunched back and pot belly became more pronounced. The marionette Punch was the celebrity disrupting the action in puppet plays all around the country, in established puppet theatres and in fairground booths where puppets were a popular feature of all the great fairs and small country wakes throughout the century."

Marionette shows were expensive to operate, however, "and by the end of the 18th century glove puppet versions of the Punch show, performed in small portable booths became a familiar sight on city streets and country lanes instead."

"With Punch���s move from marionette stage to portable booth came new clothes and new companions. By 1825 we hear in Bernard Blackmantle���s The English Spy of his wife being called Judy instead of Joan: ���old Punch with his Judy in amorous play,��� and of Punch���s having a Toby the dog, usually played by a real dog.

A role for Tilly, perhaps...?

Punch & Judy shows were not just for children in past centuries. As the V&A curator notes:

Aspects of the comedy such as the marital strife between Punch and Judy, and in Piccini���s show the relationship between Punch and his girlfriend Pretty Polly, obviously struck a chord with many adult members of the audience. Punch was a well known celebrity with the satirical magazine named after him in London in 1841, children���s picture books published based on his shows, and images of him proliferating on all manner of household artefacts, from doorstops to baby���s rattles.

"As today, some censured the shows for Punch���s violent behaviour, but Punch & Judy found an ally in Charles Dickens, whose novels include several references to the shows. Dickens defended them as enjoyable fantasy that would not incite violence:

" 'In my opinion the Street Punch is one of those extravagant reliefs from the realities of life which would lose its hold upon the people if it were made moral and instructive.' "

Or as Mr. Punch himself would say, "That's the way to do it!"

For more information on Punch & Judy, visit the V&A's Punch & Judy pages, Punch & Judy Online, and the Punch & Judy Fellowship. For puppetry in general, see The Curious School of Pupptry (where Howard teaches), the Puppet Place News blog, Puppeteers UK, and The Centre for Research on Objects & Puppets in Performance.

The art above is credited in the picture captions. (Run your cursor over the images to see them.) Some of my text comes from a previous post in the summer of 2016, when Howard began to put his Punch & Judy show together. All rights to the text quoted from the V&A website reserved by the V&A Museum, London, 2012.

August 16, 2021

Tunes for a Monday Morning

I woke up to a choir of late-summer birdsong this morning, so here's a collection of "bird songs" to start the week.

Above: "The Eagle" by Scottish musicians Jenny Sturgeon and Inge Thomson, from their collaborative stage show and album Northern Flyway (2014): an audio-visual production exploring the ecology, folklore, symbolism and mythology of birds. The music "draws on the field recordings of birdsong expert Magnus Robb, on Sturgeon��'s background as a bird biologist, and on Thomson��s home turf of Fair Isle, Shetland." It's a gorgeous album.

Below: "Union of Crows" by Salt House (Jenny Sturgeon, Lauren MacColl, Ewan MacPherson), based in Scotland. The song, written by Ewan, appears on the band's latest album, Huam (2020), which is highly recommended. Huam is a Scottish word meaning "the moan of an owl in the warm days of summer."

Above: "Jenny Wren" by singer, songwriter and folk music scholar Fay Hield (co-creator of the Modern Fairies project), performed with Sam Sweeney, Rob Habron, and Ben Nicholls. This is an original song rooted in the folk tradition, drawing on the "problematic pregnancy" theme in British balladry. Fay discusses this theme and the process of writing "Jenny Wren" here. The song appears on her deeply magical album Wrackline (2020), also highly recommended.

Below: "The Magpie," a song compiled from magpie superstitions and rhymes, performed by The Unthanks (Rachel and Becky Unthank), from Northumbria. The song appeared on their album Mount the Air (2015), and is performed here that same year.

Above: Sydney Carter's "The Crow on the Cradle," performed by the English vocal harmony trio Lady Maisery (Hannah James, Hazel Askew, Rowan Rheingans). The song appeared on their second album, Mayday (2013).

Below: "Little Sparrow" by Leyla McCalla, an American classical, folk, and Delta blues musician of Haitian heritage. The song appears on her fine solo album A Day for the Hunter, A Day for the Prey (2016).

Above: "Cuckoo," a traditional British ballad performed by The Rheingans Sisters (Rowan and Anna Rheingans), from the Peak District. The song appeared on their second album Already Home (2019).

Below: "Cuckoo" is also part of the North American song tradition. This variant of the ballad is performed by Rising Appalachia (sisters Leah Song and Chloe Smith), who draw inspiration from the folk, bluegrass, and blues of their native Georgia and the vibrantly multi-cultural music traditions of New Orleans.

From dawn to dusk, two final "bird songs" to end with:

Above: "Waiting for the Lark," a traditional song performed by folksinger and fiddle player Jackie Oates, from Staffordshire. The song appeared on her fifth solo album, Lullabies (2013).

Below: "Nest," written by Canadian folk, bluegrass, and blues musician Ruth Moody. The song appeared on her first solo album The Garden (2010).

...up in these wild skies...we'll greet the moonrise...when the day is spent....

The digital collages above are by Christian Schloe; all rights rserved by the artist. To see more of Schloe's work, go here.

For a post on the folklore of birds, go here.

August 9, 2021

I'm away with the fairies this week...

Actually I'm away at a long-delayed-by-the-pandemic family gathering. I'll be back next week, and Myth & Moor will resume with a post on Monday, August 17th.

Tilly, meanwhile, is doing well. We're still waiting on one lab result, but the others have been encouraging. The hair on her tummy (where it was shaved for tests) is starting to grow in and she continues to be a little trooper. Alas, I'm the one under the weather now, but we're hoping this gentle week with family will bring my strength back too.

In lieu of this week's posts, here's a bit of recommended reading gathered from hither and yon:

~Hope.docx by Sabrina Orah Mark, from her brilliant fairy tale column, Happily (Paris Review)

True to Nature, nature authors on the children's books that inspired them, by Melissa Harrison (The Guardian)

Pippi and the Moomins, as an antidote to fascism, by Richard W. Orange (Aeon)

Six Questions for Charlotee McConaghy, author of Once There Were Wolves (Orion)

The Joy of Being Animal by Melanie Challenger (Aeon)

Animal Agents by Amanda Rees (Aeon)

What the Animal World Can Teach Us About Human Nature, a conversation between Carl Safina and Nick McDonell (Literary Hub)

Plants Feel Pain and Might Even See, an excerpt from Peter Wohlleben's new book The Heartbeat of Trees (Nautilus)

An interview with Robin Wall Kimmerer, author of Braiding Sweetgrass (The Guardian)

Can Reading Make You Happier?, an essay on bibliotherapy by Ceridwen Dovey (The New Yorker)

Typos, tricks and misprints, an essay on the weirdness of English spelling by linguist Arika Okrent (Aeon)

Laurie Lee's Loving Letters to a Secret Daughter by Vanessa Thorpe (The Guardian)

His Fair Lady, a fascinating piece on George Bernard Shaw's wife by Donna Ferguson (The Guardian)

The Wyrd Ones, a conversation between Robert Macfarlane and Johnny Flynn (Literary Hub)

And to listen to:

Robert Macfarlane on Desert Island Disks (BBC Radio 4)

Kyle Whyte and Jay Griffiths in conversation, discussing indigenous cultures and climate change (Literary Hub)

Jeff VanderMeer and Lili Taylor in conversation, on books, birds, and beauty (Literary Hub)

An interview with Melissa Febos, author of the devastating new essay collection Girlhood (Literary Hub)

Katherine Langerish at the Glasgow Centre for Fantasy and the Fantastic, discussing her fine new book on C.S. Lewis's Chronicles of Narnia

Honouring the Ancestors, an episode in the "Wise Women: The Vicar and the Witch" podcast (the witch here being my friend and Dartmoor neighbour Suzi Crockford)

An interview with Hedgespoken's Tom Hirons (another good Dartmoor friend), Episode 16 on Sharon Blackie's podcast This Mythic Life

The classic fairy paintings above are by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939).

August 5, 2021

The Dark Forest

"In the mid-path of my life, I woke to find myself in a dark wood," writes Dante in The Divine Comedy, beginning a quest that will lead to transformation and redemption. A journey through the dark of the woods is a motif common to fairy tales: young heroes set off through the perilous forest in order to reach their destiny, or they find themselves abandoned there, cast off and left for dead. The path is hard to find and treacherous, prowled by wolves, ghosts, and wizards...but helpers, too, appear along the way: good fairies, wise elders, and animal guides, usually cloaked in unlikely disguises. The hero's task is to tell friend from foe, and to keep walking steadily onward.

The Dark Forest is not the merry greenwood of Robin Hood legends, or a Disney glade where dwarves whistle as they work, or a National Park with walkways and signposts and designated camping sites; it's the forest primeval, true wilderness, symbolic of the deep, dark levels of the psyche; it's the woods where giants will eat you and pick your bones clean, where muttering trees offer no safe shelter, where the faeries and troll folk are not benign. It's the woods you may never come back from.

"The woods enclose," writes Angela Carter in The Bloody Chamber. "You step between the fir trees and then you are no longer in the open air; the wood swallows you up. There is no way through the wood anymore; this wood has reverted to its original privacy. Once you are inside it, you must stay there until it lets you out again for there is no clue to guide you through in perfect safety; grass grew over the tracks years ago and now the rabbits and foxes make their own runs in the subtle labyrinth and nobody comes.... "

"I stood in the wood," Patricia McKillip tells us in Winter Rose. "Now it was a grim and shadowy tangle of thick dark trees, dead vines, leafless branches that extended twig like fingers to point to the heartbeat of hooves. The buttermilk mare, eerily, eerily pale in that silent wood, galloped through the trees;  tree boles turned toward it like faces. A woman in her wedding gown rode with a man in black; he held the reins with one hand and his smiling bride with the other. She wore lace from throat to heel; the roses in her chestnut hair glowed too bright a scarlet, mocking her bridal white���When they stopped, her expression began to change from a pleased, astonished smile, to confusion and growing terror. What twilight wood is this? she asked. What dead, forgotten place?"

tree boles turned toward it like faces. A woman in her wedding gown rode with a man in black; he held the reins with one hand and his smiling bride with the other. She wore lace from throat to heel; the roses in her chestnut hair glowed too bright a scarlet, mocking her bridal white���When they stopped, her expression began to change from a pleased, astonished smile, to confusion and growing terror. What twilight wood is this? she asked. What dead, forgotten place?"

The goblins of the glen, in Christina Rossetti 's great poem "Goblin Market," are thoroughly dangerous creatures. When young Laura buys but will not eat their fruit...

"Lashing their tails

They trod and hustled her,

Elbow���d and jostled her,

Claw���d with their nails,

Barking, mewing, hissing, mocking,

Tore her gown and soil���d her stocking,

Twitch���d her hair out by the roots,

Stamp���d upon her tender feet,

Against her mouth to make her eat."

To know the woods and to love the woods is to embrace it all, the light and the dark -- the sun dappled glens and the rank, damp hollows; beech trees and bluebells and also the deadly fungi and poison oak. The dark of the woods represents the moon side of life: traumas and trials, failures and secrets, illness and other calamities. The things that change us, temper us, shape us; that if we're not careful defeat or destroy us...but if we pass through that dark place bravely, stubbornly, wisely, turn us all into heroes.

"The sense of secrets, silence, surprises, good and bad, is fundamental to forests and informs their literatures," notes Sara Maitland in Gossip from the Forest. "In fairy stories this is sometimes simple and direct: Hansel and Gretel get lost in the woods, and then suddenly they come upon the gingerbread house. Snow White runs in terror through the forest and suddenly stumbles upon the dwarves' cottage; characters spending scary nights in or under trees suddenly see a twinkling light -- and they make their laborious way towards it without having any idea what they will find when they arrive.....

"The forest is about concealment and appearances are not to be trusted. Things are not necessarily what they seem and can be dangerously deceptive. Snow White's murderous stepmother is truly the 'fairest of them all,' The wolf can disguise himself as a sweet old granny. The forest hides things; it does not open them out but closes them off. Trees hide the sunshine; and life goes on under the trees, in thickets and tanglewood. Forests are full of secrets and silences. It is not strange that the fairy stories that come out of the forest are stories about hidden identities, both good and bad."

Appearance deceive in the dark of the woods. You must beware of the helpful wolf by the path, of the beautiful woman who asks for a kiss, of the cozy little house with its door standing open, a meal on the table, and its owner nowhere in sight. No matter how tired you are, warns Lisel Mueller (in her poem "Voice from the Forest"), do not enter that house, do not eat the bread, do not drink the wine: "It is only when you finish eating and, drowsy and grateful, pull off your shoes, that the ax falls or the giant returns or the monster springs or the witch locks the door from the outside and throws away the key."

But if you must enter, Neil Gaiman advises (in his poem "Instructions"), be courteous. And wary. "A red metal imp hangs from the green���painted front door, as a knocker, do not touch it; it will bite your fingers. Walk through the house. Take nothing. Eat nothing."

Those last words are important. Folk tales from all over the world warn that eating the food of a witch, a demon, a djinn, a troll, an ogre, or the faeries can be a dangerous proposition. You might owe your youngest child in return, or be bound to your host for the rest of your life. Likewise, don't kiss the beautiful woman who offers you a meal and a bed in her sumptuous chateau hidden deep in the woods. By morning light she'll be a monster, and her house but a pile of rocks and bones.

And yet, despite all the fairy tale warnings, sometimes we're compelled to run to the dark of the woods, away from all that is safe and familiar -- driven by desperation, perhaps, or the lure of danger, or the need for change. Young heroes stray from the safe, well-trodden path through foolishness or despair...but perhaps also by canny premeditation, knowing that venturing into the great unknown is how lives are tranformed. When Gretel walks into the woods, writes Andrea Hollander Budy (in her poem "Gretel," from The House Without a Dreamer), "she means to lose everything she is. She empties her dark pockets, dropping enough crumbs to feed all the men who have touched her or wished." In Ellen Steiber's "Silver and Gold," Red Riding Hood is asked to explain how she failed to distinguish her grandmother from a wolf. "It's complicated," she answers. "Sometimes it's hard to tell the difference between the ones who love you and the ones who will eat you alive." But what she doesn't say is that if the wolf comes again, she will surely follow. Why? Carol Ann Duffy answers in her poem "Little Red-Cap" (from The World's Wife): "Here's why. Poetry. The wolf, I knew, would lead me deep into the woods, away from home, to a dark tangled thorny place lit by the light of owls." To the place of poetry and adventure. The place where the hard and perilous work of transformation begins.

Sara Maitland compares the transformational magic in fairy tales to the everyday magic that turns caterpillars into butterflies. "[S]omething very dreadful and frightening happens inside the chrysalis," she points out. "We use the word 'cocoon' now to mean a place of safety and escape, but in fact the caterpillar, having constructed its own grave, does not develop smoothly, growing wings onto its first body, but disintegrates entirely, breaking down into organic slime which then regenerates in a completely new form. It goes as a child into the dark place and is lost; it emerges as the princess, or proven hero. The forest is full of such magic, in reality and in the stories."

My husband Howard, a theatre director, uses the term "the Dark Forest" to refer to the part of the art-making process when we've lost our way: when the creation of a story or a painting or a play reaches a crisis point...when the path disappears, the idea loses steam, the plot line tangles, the palette muddies, and there is no way, it seems, to move forward. This often occurs, interestingly enough, right before true magic happens: first the crisis, then a breakthrough, an unexpected solution, and the piece comes to life. In a journal he wrote some years ago, while creating a fairy tale play in Portugal, he noted:

"Today I arrived in the middle of the Dark Forest, and the path has almost disappeared. It is scary now, and all the certainties have gone. The cast members are weary, and their ability to come up with interesting work has diminished. Even our opening meditation today felt tired. The Dark Forest. I knew I was heading into it, and, as always, the forest has its own way of manifesting in each creative project. Perhaps the performers are getting stuck and are unable to develop their parts. Perhaps it's that our storytelling has become flat, or that I'm neglecting some simple but crucial aspect of the directorial process. Or maybe it's all of these things....

"Today I arrived in the middle of the Dark Forest, and the path has almost disappeared. It is scary now, and all the certainties have gone. The cast members are weary, and their ability to come up with interesting work has diminished. Even our opening meditation today felt tired. The Dark Forest. I knew I was heading into it, and, as always, the forest has its own way of manifesting in each creative project. Perhaps the performers are getting stuck and are unable to develop their parts. Perhaps it's that our storytelling has become flat, or that I'm neglecting some simple but crucial aspect of the directorial process. Or maybe it's all of these things....

"It's difficult to keep my original vision of the piece as I travel through the forest. I have to trust the vision I had at the start of the work, and that the ideas that have been set in motion will somehow come to fruition. I know that I can't lose faith now, even though at this point in the creative process one often starts to question the show, the cast, and one's own ability. I can't turn around. I have to keep going, through this tough period, and find energy from somewhere.

'I'm reminded of the first day of the pilgrimage I once took to Santiago de Compostela, biking alone across the Pyranees of France and Spain. I cycled up route Napoleon late in the day, as the sun was setting, knowing that no matter how exhausted I was I had to push on to Roncesvalles. I couldn't turn back, I was too far along the path -- but if I didn't get to the monastery before sundown, I could lose my way in those cold, dark mountains, even die of exposure. It's a similar feeling that I have now: I'm exhausted, I don't know when the turning point will come, but I have to plough on."

So what should we do when we're in the Dark Forest, creatively or personally? Perservere. As Howard says, plough on. The gifts of the journey are worth the hardship, as writer & writing teacher Elizabeth Jarrett Andrew notes: