Terri Windling's Blog, page 3

February 7, 2022

Tunes for a Monday Morning

Wassailing was once a mid-winter folk custom found all across the British Isles. Today it still survives as a living tradition in some rural communities (particularly here in the West County), and it is currently enjoying a contemporary revival in numerous others.

There are two distinct forms of wassailing: door-to-door or under the trees. The first takes place in the run-up to Christmas and is related to the custom of carolling: wassailers go house to house singing wassail songs, collecting coins, drink, or food in their wassail bowls. The second kind of wassail generally happens some time in January and involves the "waking" and blessing of apple trees to ensure a good harvest in the year ahead. These ceremonies can be simple or lavish, taking place by day or by night, sober and family-friendly or drunken and raucous. What they share in common are traditional wassail songs and stories, the custom of leaving toast in the trees (a gift for the robins or spirits) and blessing the roots with last year's apple juice or cider, and making noise (with drums, or guns, or pots-and-pans) to wake the trees and call back the sun. To learn more, read Jude Roger's recent article on wassailing in The Guardian, or see The Tradfolk Wassail Directory on the Tradfolk website.

There are two distinct forms of wassailing: door-to-door or under the trees. The first takes place in the run-up to Christmas and is related to the custom of carolling: wassailers go house to house singing wassail songs, collecting coins, drink, or food in their wassail bowls. The second kind of wassail generally happens some time in January and involves the "waking" and blessing of apple trees to ensure a good harvest in the year ahead. These ceremonies can be simple or lavish, taking place by day or by night, sober and family-friendly or drunken and raucous. What they share in common are traditional wassail songs and stories, the custom of leaving toast in the trees (a gift for the robins or spirits) and blessing the roots with last year's apple juice or cider, and making noise (with drums, or guns, or pots-and-pans) to wake the trees and call back the sun. To learn more, read Jude Roger's recent article on wassailing in The Guardian, or see The Tradfolk Wassail Directory on the Tradfolk website.

Here in Chagford, our wassail in mid-January was a daylight affair under the apple trees of a community field, full of stories and songs and children blessing the trees with juice from the wassail cup. Down the road, in the village of Lustleigh, was a wilder wassail gathering by the light of the moon, with black-clad Border Morris dancers waking the trees their sticks and their cries and their pounding feet. I love both kinds of wassailing, dark and bright: celebrating the seasons, nature's bounty, and the bonds of community.

The video above looks at the history of wassailing and other winter folk rituals -- filmed by BBC Bristol in 1977, and featuring music by the Albion Band.

Below is a Cornish variant of a well-known wassail song performed by Lady Maisery (Hannah James, Rowan Rheingans, Hazel Askew), with Jimmy Aldridge and Sid Goldsmith. It's from Awake Arise: A Winter Album (2019).

Above: "The Apple Tree Man" performed by John Kirkpatrick with Rosie Cross, Georgina Le Faux, Michael Gregory, Jane Threlfall, and Carl Hogsden, on their album Wassail!: A Celebration of an English Midwinter (1998).

Below: "The Gloucestershire Wassail" performed by Magpie Lane on their album Wassail!: A Country Christmas (2009).

Above: "Homeless Wassail," a contemporary wassail by the Canadian trio Finest Kind (Ian Robb, Ann Downey, and Shelley Posen). The song can be found on Robb's album Music for a Winter's Eve (2012).

Below: "Sugar Wassail" performed the great Waterson-Carthy band (Norma Waterson, Martin Carthy, and their daughter Eliza Carthy, with Tim van Eyken), from Holy Heathens and the Old Green Man (2006). It's poignant to listen to their music right now after the death of Norma a week ago, at the age of 82. This legendary singer (and legendary family) shaped the field of English folk music as we know it today and her loss has broken hearts all around the world, including mine.

One more video to end with: a short clip of Beltane Border, our local Border Morris side, performing at a wassil celebration at The Old Chuch House Inn at Torbyran. We are so lucky to have this group on Dartmoor, keeping the seasons turning....

Imagery above: a drawing of the Apple-Tree-Man by Alan Lee, two photographs from Chagford's wassail: storytelling and children blessing the trees, and morris dancing by Dartmoor's Beltane Border.

February 3, 2022

The cure for susto

The Radiant Life of Animals by Chickasaw novelist, poet, and essayist Linda Hogan is a gorgeous collection of poetry and prose about the tenor of our daily relationship with the more-than-human world -- including wolves, crows, foxes, bears, mountain lions and horses, as well as the land that sustains us all and nurtures us body and soul.

In the book's Introduction she writes:

"A geography of spirit, an individual and collective tribal soul, originates with the larger geography of nature, of the ecosystem in which we live. For tribal peoples, this has always been a constant. The animal realm, sacred waters, and surrounding world in all its entirety is an equal to our human life. We are only part of it, and such an understanding offers us the bounty and richness of our world, one to be cared for because it is truly the being of the human....

"Nature is even now too often defined by people who are separated from the land and its inhabitants. In our time, with our lives, we usually include primarily only a majority of the developed world. Such a life is one that carries and creates the human spirit with more difficulty. Too rarely do we understand that the soul lies at all points of intersection between human consciousness and all the rest of nature. With our bodies and selves, skin is hardly a container. Our boundaries are not solid; we are permeable; therefore, even as solitary dreamers we are still rooted in the greater soul outside of us. If we are open enough, strong enough, to connect with the surrounding world, we are capable of becoming something greater than what we are merely within our own selves."

Soul loss, Hogan explains, is what happens when our relationship with the nonhuman world becomes frayed:

"In contemporary North American Latino communities, soul loss is called susto. It is a common condition in the modern world. Susto probably began when, as in many religions, the soul was banished from nature, when humanity withdrew from the world. There became only two things, extremes viewed from our point of understanding -- human and nature, animate and inanimate, sentient and not.

"This was the moment when the soul first began to slip away and crumble.

"In the reversal of and healing from soul loss, Brazilian tribal members who tragically lost their land and place in the world and now dwell in the city often visit or at least reimagine nature in order to become whole again and have their souls returned to them. Anthropologist Michael Harner wrote about the healing methods among Indian people who were forcibly relocated to urban slums, usually from the rain forests. The healing ritual most often takes place in the forest at night, as the person is returned, if only for a while, to the land he or she once knew. The people are often cured through their renewed connections, their 'vision of the river forest world, including visions of animals, snakes, and plants.' This connection brings back the soul that has returned to these places. Unfortunately, in our time, these homes in the forests may now only be ghosts of what they once were.

"The cure for susto, soul sickness, is not found in books. It is written in the bark of a tree, in the moonlit silence of night, along the bank of a river, and in the voice. This cure is outside our human selves, but it becomes the thread that connects the outer world with our own."

The marvellous, spirited sculptures today are by British ceramicist Sophie Woodrow. She graduated with a BA in Studio Ceramics from Falmouth College of Art in Cornwall, and is now based in Bristol. Woodrow's work is informed by her love of natural history and a fascination with the Victorians' relationship to nature: the ways they both embraced and feared new theories of evolution, while often misapprehending them. Her sculptures "are not visitors from other worlds, but the ���might-have-beens��� of this world," as she seeks to "assemble creatures from the strange notions of what we define as ���nature��� and of each other as people ��� as ���other���."

To see more of her art, please visit Woodrow's Instagram page, and the Messums Wiltshire gallery site.

The text above is from The Radiant Lives of Animals by Linda Hogan (Beacon Press, 2020). All rights to the text and art in the post reserved by the author and artist. Some related posts: The language of the animate earth, On language and mystery, and The philosophy of compassion.

February 2, 2022

Animal Medicine

Come into Animal Presence

by Denise Levertov

Come into animal presence.

No man is so guileless as

the serpent. The lonely white

rabbit on the roof is a star

twitching its ears at the rain.

The llama intricately

folding its hind legs to be seated

not disdains but mildly

disregards human approval.

What joy when the insouciant

armadillo glances at us and doesn't

quicken his trotting

across the track into the palm brush.

What is this joy? That no animal

falters, but knows what it must do?

That the snake has no blemish,

that the rabbit inspects his strange surroundings

in white star-silence? The llama

rests in dignity, the armadillo

has some intention to pursue in the palm-forest.

Those who were sacred have remained so,

holiness does not dissolve, it is a presence

of bronze, only the sight that saw it

faltered and turned from it.

An old joy returns in holy presence.

The art today is by American ceramicist Caroline Douglas, who received a BFA from the University of North Carolina and has worked in clay for over forty years, inspired by mythology, fairy tales, dreams and the antics of animals and children. Since sustaining a serious injury in 2000, Douglas has been exploring the relationship between healing and creativity in her dual roles as artist and teacher:

"Our imaginations are sacred," she explains. "At the deepest level, they can put us in touch with the collective unconscious that we all share. I create in clay a version of my intentions and dreams. Making something real in physical form makes it real on many levels. In my classes we travel a journey of transformation and exploration through art to find a deeper place, a more fulfilling place -- that place where stillness reigns and time stretches out and magic has its way with us. It is an alchemy of sorts, a turning of lead into gold. "

Please visit the artist's website to see more of her deeply magical work.

The art above is by Caroline Douglas; all rights reserved by the artist. The names of the individual sculptures can be found in the picture captions. (Run your cursor over the images to see them.)

The poem above is by Denise Levertov (1923-1997), from Poems 1960-1967 (New Directions, 1983). All rights reserved by the Levertov estate.

February 1, 2022

Let me be a good animal

Every time I announce I'm back in the studio, and back to a steady work schedule again, a cold wind tears right through my days and scatters all my careful plans....or at least that's what chronic illness feels like: a weather system rattling the windows...threatening to uproot the trees...then blowing over, leaving a hush and clear blue sky till the next storm comes.

Illness, like weather, is elemental. It strips us down to our animal selves: to the physicality of flesh and bone, the primacy of rest and food, and the mystery of healing processes flowing through the blood and psyche. When I'm too low to write, or paint, or even climb the hill to the studio, I take a deep breath and pray: Let me be a good animal today.

And then I bundle up warm, batten down the hatches, and wait for the storm to break.

I've been been repeating this little prayer for so long that I'd forgotten where it first came from: Let me be a good animal today. An American author, an essayist, someone in the SouthWest, but who? It took a bit of diligent searching to find the reference among my books...and here it is, from High Tide in Tucson by Barbara Kingsolver:

"For each of us -- furred, feathered, or skinned alive -- the whole earth balances on the single precarious point of our own survival. In the best of times, I hold in mind the need to care for things beyond the self: poetry, humanity, grace. In other times, when it seems difficult merely to survive and be happy about it, the condition of my thought tastes as simple as this: let me be a good animal today. I've spent months at a stretch, even years, with that taste in my mouth, and have found that it serves. [...]

"Every one of us is called upon, probably many times, to start a new life. A frightening diagnosis, a marriage, a move, loss of a job or a limb or a loved one, a graduation, bringing a new baby home: it's impossible to think at first how this will all be possible. Eventually, what moves it all forward is the subterranean ebb and flow of being among the living.

"In my own worst seasons I've come back from the colorless world of despair by forcing myself to look hard, for a long time, at a single glorious thing: a flame of red geranium outside my bedroom window. And then another: my daughter in a yellow dress. And another: the perfect outline of a full, dark sphere behind the crescent moon. Until I learned to be in love with my life again. Like a stroke victim retraining new parts of the brain to grasp lost skills, I have taught myself joy, over and over again.

"It's not such a wide gulf to cross, then, from survival to poetry. We hold fast to the old passions of endurance that buckle and creak beneath us, dovetailed, tight as a good wooden boat to carry us onward. And onward full tilt we go, pitched and wrecked and absurdly resolute, driving in spite of everything to make good on a new shore. To be hopeful, to embrace one possibility after another -- that is surely the basic instinct. Baser even than hate, the thing with teeth, which can be stilled with a tone of voice or stunned by beauty. If the whole world of living has to turn on the single point of remaining alive, that pointed endurance is the poetry of hope. The thing with feathers.

"What a stroke of luck. What a singular brute feat of outrageous fortune: to be born to citizenship in the Animal Kingdom. We love and we lose, go back to the start and do it right over again."

We do indeed.

The beautiful imagery today is by Polish illustrator Joanna Concejo, who studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Poznan and now lives in Paris. Her art has been exhibited in galleries across Europe, as well as at the Bologna Children's Book Fair and ILUSTRARTE in Portugal; and her books have been published in France, Italy, Spain, Poland and South Korea. The Lost Soul, a children's book with text by Nobel Prize winner Olga Tokarczuk, was published in an English translation by Antonia Lloyd-Jones last year.

"Inspiration is not something I seek," she says, "it is more a state of availability in life, an openness to things that happen to me, to the encounters I have, to images, landscapes, to everything I can see, hear, touch....I am often surprised myself by what I do. It is often very unconscious."

To see more of her work, visit the artist's Instagram page, or the Toi Gallery website.

The text above is from High Tide in Tucson: Essays from Now or Never (HarperCollins 1995); all rights reserved by the author. The pictures are by Joanna Conjo; all rights reserved by the artist.

January 31, 2022

Tunes for a Monday Morning

I'm starting the week with some favourite songs featuring animals and birds, in which our old friend Mr. Fox will certainly make an appearance....

Above: "Hare Spell," Fay Hield's wonderfully eerie ballad of animal-human shapeshifting. First created for the Modern Fairies project, Fay's lyrics are taken from an actual spell by a 17th century Scottish witch. "Isobel [Gowdie] was tried in 1662 during the witchcraft trials," she explains, "and her confession gives a clear account, seemingly uncoerced, into her activities with the devil and visiting the king of the fairie. She includes several spells and chants used to conduct her own magic, including this spell to turn the utterer into a hare to do the devil���s work." Go here to read about the creation of the song (and the magical way the music was formed); go here to listen to an answering song about shapeshifting from the hare's point of view (with gorgeous lyrics by poet Sarah Hesketh); and go here to read more about witch-hares in the folklore tradition. You can also listen to a radio play crafted around Fay's song: Hare Spell Part One and Part Two.

Above: "Hare Spell," Fay Hield's wonderfully eerie ballad of animal-human shapeshifting. First created for the Modern Fairies project, Fay's lyrics are taken from an actual spell by a 17th century Scottish witch. "Isobel [Gowdie] was tried in 1662 during the witchcraft trials," she explains, "and her confession gives a clear account, seemingly uncoerced, into her activities with the devil and visiting the king of the fairie. She includes several spells and chants used to conduct her own magic, including this spell to turn the utterer into a hare to do the devil���s work." Go here to read about the creation of the song (and the magical way the music was formed); go here to listen to an answering song about shapeshifting from the hare's point of view (with gorgeous lyrics by poet Sarah Hesketh); and go here to read more about witch-hares in the folklore tradition. You can also listen to a radio play crafted around Fay's song: Hare Spell Part One and Part Two.

Below: "Three Ravens" (a variant of "Twa Corbies," Child Ballad 26), performed by Dorset folk duo Ninebarrow (Jon Whitley and Jay LaBouchardiere). The song appeared on their album Releasing the Leaves (2016).

Above: "The White Hare," a traditional song performed by folk (and rock) musician Jack Sharp, from Bedfordshire. It comes from his solo album Good Times Older (2020).

Below: "I am the Fox," written and performed by Nancy Kerr (from London) and James Fagan (from Sydney, Australia). It's appeared on Myth & Moor before, but I never get tired of this one....

Above: "Daddy Fox," a traditional song performed by the a capella folk quartet The Witches of Elswick (Becky Stockwell, Gillian Tolfrey, Bryony Griffith and Fay Hield), from their album Out of Bed (2003).

Below: "The Fox," another variant of the same song performed by the Galway quartet We Banjo 3 (Enda Scahill, Fergal Scahill, Martin Howley, David Howley), with Sharon Shannon on accordion. This is another one I return to often. Surely the door in the video is one of the portals to Bordertown....

Let's end, as we began, with another song from Fay Hield's exquisite album Wrackline (2020): a re-working of an American ballad that gives the death of the Old Grey Goose its due. The performance is from the Wrackline album launch, with Sam Sweeney on fiddle, Rob Habron on guitar, and Ben Nicholls on bass. To read Fay's thoughts about the song and the folklore of anthropomorphism, go here.

Let's end, as we began, with another song from Fay Hield's exquisite album Wrackline (2020): a re-working of an American ballad that gives the death of the Old Grey Goose its due. The performance is from the Wrackline album launch, with Sam Sweeney on fiddle, Rob Habron on guitar, and Ben Nicholls on bass. To read Fay's thoughts about the song and the folklore of anthropomorphism, go here.

The art today is by Vancouver-based illustrator Julie Morstad. To see more of her work, go here.

January 13, 2022

Intimate Companions

I'm working on another "fox" piece for you, but I wasn't able to complete in time for posting today. Let me leave you with this instead: a poem I found in the leaf mulch of the woods. Stories come from the damnedest places.

Art by Adrienne Segur (1901-1981), from The Golden Book of Fairy Tales.

January 12, 2022

Fox stories

Following on from yesterday's post on the fox in myth, legend, and mythic arts, I'd like to take a second look at fox imagery in poetry.

There are so many fine poems about foxes that I could fill the page attempting to list them all, but some of the very best include: "The Fox" and "Straight Talk from Fox" by Mary Oliver, "Vixen" and "Fox Sleep" by W.S. Merwin, "The Thought Fox" by Ted Hughes, "February: The Boy Breughel" by Norman Dubie, "The Fox Bead in May" (based on Asian "9-tailed fox" folklore) by Hannah Sanghee Park, "The Fox Smiled, Famished" by Mike Allen, "Michio Ito's Fox & Hawk" by Yusef Komunyakaa, and "Three Foxes by the Edge of the Field at Twilight" by Jane Hirshfield (tucked into the picture captions; run your cursor over the images to read it)...in addition to the fox poems quoted in yesterday's post, and A.A. Milne's charming children's poem about three foxes who don't wear sockses.

My favorite fox poems of all, however, are by the great American poet Lucille Clifton (1936-2010), whose work "emphasizes endurance and strength through adversity, focusing particularly on African-American experience and family life." Here's the first of them:

telling our stories

by Lucille Clifton

the fox came every evening to my door

asking for nothing. my fear

trapped me inside, hoping to dismiss her

but she sat till morning, waiting.

at dawn we would, each of us,

rise from our haunches, look through the glass

then walk away.

did she gather her village around her

and sing of the hairless moon face,

the trembling snout, the ignorant eyes?

child, i tell you now it was not

the animal blood i was hiding from,

it was the poet in her, the poet and

the terrible stories she could tell.

The second poem is an absolute stunner: "A Dream of Foxes," written in six parts. You'll it find here.

The gorgeous fox photographs today are by British wildlife photographer Richard Bowler.

"I've been passionate about the natural world all my life," Richard says. "This interest led me into angling, to get closer to a world hidden beneath the surface of a river or lake. Angling took me all over the world, to places well off the beaten track, North, South and Central America, the Indian ocean and my particular favourite, Africa. It was on these trips that I felt the need to learn how to capture what I was seeing with the camera. Soon taking pictures became much more important than catching fish, and now I'm much more likely to be found holding a camera than a fishing rod. I hope through my photographs to show the character of the animal and, through that, to make people care."

Words: The poem above is from The Terrible Stories by Lucille Clifton (BOA Editions, 1996). The poem in the picture captions is from Each Happiness Ringed by Lions by Jane Hirshfield (Bloodaxe Books, 2005). All rights reserved by the authors.

Pictures: The photographs are by Richard Bowler, and the little drawing, "Fox Child & Friend," is from one of my sketchbooks. All rights reserved by the artists.

January 11, 2022

A Skulk of Foxes

The folkloric fox found trotting through the "Reynardine" ballad in yesterday's post came to us in mischievous Trickster guise: both clever and foolish, creative and destructive, perfectly civilized and utterly wild. Trickster foxes appear in old stories gathered from countries and cultures all over the world -- including Aesop's Fables from ancient Greece, the "Reynard" stories of medieval Europe, the "Giovannuzza" tales of Italy, the "Brer Fox" lore of the American South, and stories from diverse Native American traditions...

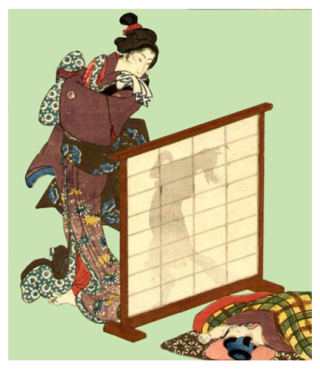

...but at the darker end of the fox-lore spectrum we find creatures of a distinctly more dangerous cast: Reynardine, Mr. Fox, kitsune (the Japanese fox wife), kumiho (the Korean nine-tailed fox), and other treacherous shape-shifters.

Fox women populate many story traditions but they're particularly prevalent across the Far East. Fox wives, writes Korean-American folklorist Heinz Insu Fenkl, are seductive creatures who "entice unwary scholars and travelers with the lure of their sexuality and the illusion of their beauty and riches. They drain the men of their yang -- their masculine force -- and leave them dissipated or dead (much in the same way La Belle Dame Sans Merci in Keats's poem leaves her parade of hapless male victims).

Fox women populate many story traditions but they're particularly prevalent across the Far East. Fox wives, writes Korean-American folklorist Heinz Insu Fenkl, are seductive creatures who "entice unwary scholars and travelers with the lure of their sexuality and the illusion of their beauty and riches. They drain the men of their yang -- their masculine force -- and leave them dissipated or dead (much in the same way La Belle Dame Sans Merci in Keats's poem leaves her parade of hapless male victims).

"Korean fox lore, which comes from China (from sources probably originating in India and overlapping with Sumerian lamia lore) is actually quite simple compared to the complex body of fox culture that evolved in Japan. The Japanese fox, or kitsune, probably due to its resonance with the indigenous Shinto religion, is remarkably sophisticated. Whereas the arcane aspects of fox lore are only known to specialists in other East Asian  countries, the Japanese kitsune lore is more commonly accessible. Tabloid media in Tokyo recently identified the negative influence of kitsune possession among members of the Aum Shinregyo (the cult responsible for the sarin attacks in the Tokyo subway). Popular media often report stories of young women possessed by demonic kitsune, and once in a while, in the more rural areas, one will run across positive reports of the kitsune associated with the rice god, Inari."

countries, the Japanese kitsune lore is more commonly accessible. Tabloid media in Tokyo recently identified the negative influence of kitsune possession among members of the Aum Shinregyo (the cult responsible for the sarin attacks in the Tokyo subway). Popular media often report stories of young women possessed by demonic kitsune, and once in a while, in the more rural areas, one will run across positive reports of the kitsune associated with the rice god, Inari."

(To read Heinz's full essay on "Fox Wives & Other Dangerous Women," go here.)

There are fox wives in Western folklore as well, but rather fewer of them, and they tend to be more benevolent creatures: skittish and shy, or mysterious and wild, but fond of their human partner. An exception to this general rule can be found in the r��ven stories of Scandinavia, where the fox-women who roam the forests of northern Europe are portrayed as heart-stoppingly beautiful, fiercely independent, and extremely dangerous.

In a musical composition inspired by these legends, the Swedish/Finnish band Hedningarna sings:

In a musical composition inspired by these legends, the Swedish/Finnish band Hedningarna sings:

Fire and frost are in your eyes

are you a woman or a fox?

Wild and sly you hunt in time of darkness

long sleeves hide your claws

with your prey you play

your mouth is red with blood.

The "nine-tailed fox" of China and Japan is often (but not always) a demonic spirit, malevolent in intent. It takes possession of human bodies, both male and female, moving for one victim to another over thousands of years, seducing other men and women in order to dine on their hearts and livers. Human organs are also a delicacy for the nine-tailed fox, or kumiho, of Korean lore -- although the earliest texts don't present the kumiho as evil so much as amoral and unpredictable...occasionally even benevolent...much like the faeries of English folklore.

In the West, it's the fox-men we need to beware of -- such as Reynardine in the old folk ballad, and Mr. Fox in the fairy tale of that name. Mr. Fox is cousin to both Reynardine and the nine-tailed fox with a bit of Bluebeard thrown in for good measure, promising marriage to a gentlewoman while his lair is littered with her predecessors' bones. Neil Gaiman drew inspiration from the tale when he wrote his wry, wicked poem "The White Road":

There was something sly about his smile,

his eyes so black and sharp, his rufous hair. Something

that sent her early to their trysting place,

beneath the oak, beside the thornbush,

something that made her

climb the tree and wait.

Climb a tree, and in her condition.

Her love arrived at dusk,

skulking by owl-light,

carrying a bag,

from which he took a mattock, shovel, knife.

He worked with a will, beside the thornbush,

beneath the oaken tree,

he whistled gently, and he sang,

as he dug her grave, that old song...

shall I sing it for you, now, good folk?

(To read the full poem, go here.)

Jeannine Hall Gailey, by contrast, casts a sympathetic eye on fox shape-shifters, writing plaintively from a kitsune's point of view in "The Fox-Wife's Invitation":

These ears aren't to be trusted.

The keening in the night, didn't you hear?

Once I believed all the stories didn���t have endings,

but I realized the endings were invented, like zero,

had yet to be imagined.

The months come around again,

and we are in the same place;

full moons, cherries in bloom,

the same deer, the same frogs,

the same helpless scratching at the dirt.

You leave poems I can���t read

behind on the sheets,

I try to teach you songs made of twigs and frost.

you may be imprisoned in an underwater palace;

I'll come riding to the rescue in disguise.

Leave the magic tricks to me and to the teakettle.

I've inhaled the spells of willow trees,

spat them out as blankets of white crane feathers.

Sleep easy, from behind the closet door

I'll invent our fortunes, spin them from my own skin.

Although chancy to encounter in myth, and too wild to domesticate easily (in stories and in life), some of us long for foxes nonetheless, for their musky scent, their hot breath, their sharp-toothed magic. "I needed fox," wrote Adrienne Rich:

Badly I needed

a vixen for the long time none had come near me

I needed recognition from a

triangulated face burnt-yellow eyes

fronting the long body the fierce and sacrificial tail

I needed history of fox briars of legend it was said she had run through

I was in want of fox

And the truth of briars she had to have run through

I craved to feel on her pelt if my hands could even slide

past or her body slide between them sharp truth distressing surfaces of fur

lacerated skin calling legend to account

a vixen's courage in vixen terms

(Full poem here.)

Ah, but Fox is right here, right beside us,

Jack Roberts answers, a little warily:

Not the five tiny black birds that flew

out from behind the mirror

over the washstand,

nor the raccoon that crept

out of the hamper,

nor even the opossum that hung

from the ceiling fan

troubled me half so much as

the fox in the bathtub.

There's a wildness in our lives.

We need not look for it.

(Full poem here.)

There are a number of good novels that draw upon fox legends -- foremost among them, Kij Johnson's exquisite The Fox Woman, which no fan of mythic fiction should miss. I also recommend Neil Gaiman's The Dream Hunters (with the Japanese artist Yoshitaka Amano); Larissa Lai's When Fox Is a Thousand; and Ellen Steiber's gorgeous A Rumor of Gems (as well as her heart-breaking novella "The Fox Wife," published in Ruby Slippers, Golden Tears). Alice Hoffman's disquieting Here on Earth is a contemporary take on the Reynardine/Mr. Fox theme, as is Helen Oyeyemi's Mr. Fox, a complex work full of stories within stories within stories. For younger readers, try the "Legend of Little Fur" series by Isobelle Carmody. And for mythic poetry, I especially recommend She Returns to the Floating World by Jeannine Hall Gailey and Sister Fox���s Field Guide to the Writing Life by Jane Yolen.

More fox tales are listed here. Please add your own favourites in the Comments below.

For the fox in myth, legend, and lore, try:

Fox by Martin Wallen; Reynard the Fox, edited by Kenneth Varty; Kitsune: Japan's Fox of Mystery, Romance, and Humour by Kiyoshi Nozaki; Alien Kind: Foxes and Late Imperial Chinese Narrative by Raina Huntington; The Discourse on Foxes and Ghosts: Ji Yun and Eighteenth-Century Literati Storytelling by Leo Tak-hung Chan; The Fox and the Jewel: Shared and Private Meanings in Contemporary Japanese Inari Worship, by Karen Smythers....

And, best of all, Reynard the Fox by Anne Louise Avery, which I'll talk more about in a forthcoming post. Picture credits: Identification of the foxy art above can be found in the picture captions; run your cursor over the images to see them. Words: The passage by Heinz Insu Fenkl is from "Fox Wives & Other Dangerous Women," published in The Journal of Mythic Arts (1998); "The White Road" by Neil Gaiman and "The Fox-Wife's Invitation" by Jeannine Hall Gailey are also from JoMA (1998 and 2008); "Fox" by Adrienne Rich is from Fox: Poems 1998-2000 (Norton, 2003); and "Dream Fox" by Jack Roberts is from Tar River Poetry (2007). All rights to the art & text above are reserved by their respective creators.

Picture credits: Identification of the foxy art above can be found in the picture captions; run your cursor over the images to see them. Words: The passage by Heinz Insu Fenkl is from "Fox Wives & Other Dangerous Women," published in The Journal of Mythic Arts (1998); "The White Road" by Neil Gaiman and "The Fox-Wife's Invitation" by Jeannine Hall Gailey are also from JoMA (1998 and 2008); "Fox" by Adrienne Rich is from Fox: Poems 1998-2000 (Norton, 2003); and "Dream Fox" by Jack Roberts is from Tar River Poetry (2007). All rights to the art & text above are reserved by their respective creators.

January 10, 2022

Tunes for a Monday Morning

On a foggy winter's morning on Dartmoor, let's start with appropriately atmospheric music and go from there....

Above: "The Fog," composed and performed by Spiers & Boden (John Spiers on melodica, Jon Boden on fiddle), from their fine new abum Fallow Ground (2021). In addition to the Spiers & Boden albums and their solo work, both musicians were founding members of Bellowhead -- which is reuniting for a one-off tour later this year.

Below: "Reynardine," also from the new album. This one's a traditional English ballad about a dangerous fox shape-shifter, related to the Mr. Fox fairy tale. (See Neil Gaiman's poem "The White Road" for another take on the Reynardine/Mr. Fox/Robber Bridegroom motif.)

Above: "The Birth of Robin Hood" (Child Ballad #102), performed by Spiers & Boden on their fifth album, Vagabond (2010).

Below: "Princess Royal" from fiddler Sam Sweeney (with Louis Campbell, Jack Rutter, and my Modern Fairies colleague Ben Nicholls). Sweeney was also a member of Bellowhead, and now performs with the folk trio Leveret. "Princess Royal" appears on his beautiful solo album Unearth Repeat (2020).

Above: "Sheath and Knife" (Child Ballad #16), performed by Rachael McShane & The Cartographers (Matthew Ord and Julian Sutton) on their ballad-filled album When All Is Still (2018). McShane, too, is a Bellowhead alumnus.

Below: "The Molecatcher," a traditional song (with a new melody) from the same album.

And after that winding road of songs we really ought to end with some classic Bellowhead.

Below: "New York Girls," a modern take on an old sea shanty, performed live in 2011. This one goes out to all my women friends and publishing colleagues in NYC. It's a long, long way from there to Dartmoor...but once a New York Girl, always a New York Girl. (And yes, I can dance the polka.)

January 1, 2022

Happy New Year!

Tilly's morning: following the trail into a new year full of myth, magic, and adventure. We wish you a gentle transition from the old year to the new, with plenty of enchanted pathways to mosey along....

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 710 followers