Terri Windling's Blog, page 4

January 1, 2022

New Years Day and fresh starts

Once again I've been asked to re-post this piece, written three years ago, with my heartfelt thanks to the kind readers who remembered and requested it....

Over the last few days, I've been asking friends how they feel about New Year's celebrations, and from my small sampling (mostly of writers and artists) this is what I've learned:

The vast majority answered with the equivalent of a shrug: The New Year's holiday? They could take or leave it. A smaller (but emphatic) group detest it for a variety of reasons: the social pressure to be happy on New Year's eve, the guilt-tripping nature of New Year resolutions, the arbitrary designation of the year's end in the Gregorian calendar, or simply the bad timing of yet another celebration on the heels of Christmas. I found just a small minority who genuinely love New Year's Eve and Day, and I am one of them. In fact, it's my favorite holiday, and so I've been thinking about the reasons why -- especially since I generally mark the changing of the seasons by the pagan, not the Christian, calendar.

I grew up with the Pennsylvania Dutch traditions of my mother's large extended family: nominally Christian, but rich in folklore, folk ways, and homely forms of folk magic. One of those traditions was my mother's practice of taking down the Christmas tree on New Year's day, cleaning the house from top to bottom, and then opening the kitchen door (with a great flourish) to sweep the old year out and welcome in the new: my mother, my great-aunt Clara, and I each taking turns with the broom. Christmas was a hard time for my mother and always ended in tears, but she would rally by New Year's day, relishing the act of making order out of chaos: a woman's ritual, shared only with me and not my half-brothers (my stepfather's sons). Boys doing housework? The very notion was unthinkable in that time and place.

At some point in the midst of all that cleaning, my mother and I would sit down at the kitchen table, eat the last of the kiffles (a traditional cookie made only at Christmas; it is bad luck to eat them past New Year's Day), and talk about plans for the year ahead. These were not New Year's resolutions, exactly; no lists were made, nothing was written down. It was more like a verbal conjuring, a vision of what we'd do differently and better, spoken at the right folkloric time when words held the power of an incantation: the pause between the old year and the new when anything seemed possible.

My mother was a great believer in new beginnings, in a way that was both painful and brave. We moved around a lot when I was young, in search of work for my stepfather, whose alcoholism and violent temper ensured that employment never lasted long. In each new place my mother would mentally sweep her troubles out the kitchen door and make a brand new start: each house, each job, each new school for my young brothers and me would be different and better, she insisted. We would finally settle down.

Since the new house was usually worse than the last, she would set herself to transforming it, ingeniously making small amounts of money go a long, long way: she'd paint our rooms in surprising colors (dictated by the paint choices in the bargain bins); make new curtains in cheap, cheery fabrics edged with bright Ric Rac and Pom Pom trim; scour yard sales for pretty new dishes and lamps (constantly broken in my stepfather's rages). For a while she'd be happy and fiercely optimistic...until the usual troubles caught up with us. There would be fights, and tears, and everything would shatter. My mother would collapse, her husband disappear to the nearest bar. Then she'd pick herself up, we'd move again, and she'd start afresh with quiet courage.

As a kid I moved even more often than my mother. Unwelcome in my stepfather's home, and a regular target of his fists, when things got too bad I was shunted off to my grandmother, or my great-aunt Clara, or some other relative, along with a couple of stints in foster care -- and so I needed my mother's lesson in embracing change rather more than most. Many people from peripatetic childhoods react with a deep dislike of change. My own reaction is a mix of opposites. My childhood has left me with a soul-deep need for home, place, and community -- yet I also love stepping into the unknown and using the act of relocation as a catalyst for transformation and renewal. In this I am my mother's daughter. I like transitions, beginnings, the changing of the seasons, the turning of the calendar's pages. As I wrote in a previous New Year post:

I have a great affection for those moments in time that allow us to push the "re-set" buttons in our minds and make a fresh start: the start of a new year, the start of a new week, the start of a new morning or fresh endeavor. As L. M. Montgomery (author of Anne of Green Gables) once wrote, "Isn't it nice to think that tomorrow is a new day with no mistakes in it yet?"

The American abolitionist Henry Ward Beecher advised: "Every man should be born again on the first day of January. Start with a fresh page." Some people, of course, find a blank page terrifying...but that's something I've never quite understood. I love the feeling of potential inherent in an untouched notebook, a fresh white canvas, even a new computer folder waiting to be filled. It's the same sense of freedom to be found at the start of a journey, when all lies ahead and limits haven't yet been reached.

My mother died from cancer in 2001, at a younger age that I am now, and she never managed to turn those new beginnings into the calm, stable life she craved. The determined optimism she practiced wasn't always entirely admirable. Optimism can also be blind or foolish, and prevent the solving of problems through the refusal to accept reality. A fresh start can only transform a life if it is followed by the hard and clear-eyed work of making substantive change: leaving the violent husband, for example, rather than putting fresh paint on walls that will soon be bloodied once again.

But there were reasons my mother couldn't make those harder changes, so I'm not going to sit in judgement of her now. I'm just going to love her for who she was. Acknowledge her quiet bravery. And appreciate the gifts that she's passed on: kiffles and a broom on New Year's Day. And a love of new beginnings.

Today I will sweep the house. Tomorrow I'll sweep the studio. I'm thinking about what I'll do differently, and better.

The world is full of possibilities.

Pictures: The photographs today are from Queen's Wood, an ancient woodland in London's Muswell Hill: 52 acres of oak and hornbeam trees, abutting Highgate Wood. The pictures were taken during a pre-pandemic Christmas spent with our daughter in London. I recommend "The History and Archaeology of Queen's Wood" by Michael Hacker if you'd like to know more about this beautiful place: a tranquil, magical piece of wild preserved within a bustling cityscape. (Tilly loved it.) The last photo was taken by Howard.

Words: The poem in the picture caption is from Tell Me by Kim Addonizio (BOA Editions, 2000); all rights reserved by the author.

December 27, 2021

Tunes for a Monday Morning

On a cold, wet morning during the last week of the year, I am dreaming of the sea. Our travel plans are limited again due to the latest wave of Covid, but music carries me to the coast and I can almost taste the salt...

Above: "L�� R����il" by the Irish folk duo Zo�� Conway and John Mc Intyre, Irish fiddle/bouzouki player ��amon Doorley, and Scottish singer/songwriter Julie Fowlis. The song -- about new days, fresh starts, grief lifted and hope renewed -- was released as a single last year, and will appear on a forthcoming album inspired by Gaelic poetry of Ireland and Scotland.

Below: "��ran an R��in (The Song of the Seal)" sung by Julie Fowlis, from the Outer Hebrides, backed up by Pep��n de Mu��al��n, Barry Kerr and Rub��n Bada. "It's a traditional Gaelic song," she says, "from the voice of the seal people or selkies -- creatures who were said to shed their seal skin and take on the human form at certain times of the year. Creatures who moved between the parallel worlds of sea and land, but never truly belonging to either. I learned this from the singing of the Rev William Matheson of North Uist/Edinburgh."

Above: "The Song of the Seals" performed by Scottish folksinger Jean Redpath (1937-2014), from her 1978 album of the same name. The song, composed in the early 20th century by Harold Boulton & Granville Bantock, is said to have been inspired by a Hebridean chant used to charm seals (and the selkie folk).

Below: "The Great Selkie of Sule Skerry" (Child Ballad #113), a classic Orcadian song of the seal people performed by the great English folk & jazz singer June Tabor. The song appeared on her solo album Ashore (2011).

Above: "The Mermaid" (Child Ballad #289) performed by Welsh folksinger Julie Murphy for The Mark Radcliffe Folk Sessions (BBC Radio 2, 2015). You'll find a recording of the song on her album Every Bird That Flies (2016).

Below: "Port na bP��cai" performed by Irish folksinger Muireann Nic Amhlaoibh, with Billy Mag Fhloinn. This traditional song from the Blasket Islands of Co. Kerry tells the story of a woman "from across the waves" who has been stolen away by the fairies, never to return.

One more, below: "Fear a' Bh��ta (The Boatman)," a Scots Gaelic song from the late 18th century, recorded by Irish folksinger Niamh Parsons. It was written by S��ne NicFhionnlaigh, from the Isle of Lewis, about her passion for a fisherman from Uig. It's a tragic song about love betrayed...but in real life all ended happily and NicFhionnlaigh married her boatman.

Pictures: The seal-hound and me on the south Devon coast this autumn.

December 25, 2021

Holiday greetings from Myth & Moor

Each year the Donkey Sanctuary in Sidmouth (just south of here on the Devon coast) hosts "Carols by Candlelight" at Christmas time -- though for the last two years, because of the pandemic, the event has been held entirely online. You can watch it in the video above, or go here for additional videos introducing the Sanctuary and its shaggy denizens.

I love the Sanctuary, full of hundreds of donkeys rescued from abuse and neglect or unwanted due to age or illness, now living in comfortable barns and beautiful fields in the rolling hills above the sea. Our family sponsors a 12-year-old donkey named Zena, pictured below. She's the loveliest donkey at Paccombe Farm. Okay, I admit I'm a little biased, but just look at that little sweetie....

Whatever you celebrate at this time of year -- Christmas, Solstice, Yule, Hanukkah, another holiday, or simply making through another year -- we wish you love, light, warmth, magic, abundant creativity, and the support of a good community. You'll always find the latter here at Myth & Moor.

The beautiful donkey sketch above is by illustrator Sean Briggs, who was born on the Pennine hills of West Yorkshire and now lives and works in Buckinghamshire. Please go here to see more of his art.

December 24, 2021

On the night before Christmas....

So our Christmas eve has started with our boiler breaking down, and we're going to be gathered around the old Rayburn stove and the fireplace for warmth. But our daughter is home, the pantry is stocked, and we've got our own little Grumpy Reindeer. so we're good.

Have a very Merry Christmas!

December 22, 2021

The folklore of winter

Each year as Christmas approaches I receive requests to re-post this piece on the tales and folk customs of winter holiday season....

A cold wind howls, stripping leaves off of the trees, and the pathways through the hills are laced with frost. It's time to admit that winter is truly here, and it's here to stay. But Howard keeps the old Rayburn stove in the kitchen well fed, so our wind-battered little house at the edge of the village is cozy and warm. Our Solstice decorations are up, and tonight I'll make a second batch of kiffles: the Christmas cookies passed on through generations of women in my mother's Pennsylvania Dutch family...carried now to England and passed on to our daughter, who may one day pass it to children of her own.

My personal tradition is to talk to those women of the past generations as I roll out the kiffle dough and cut, fill, roll, and shape each cookie: to my mother, grandmother, and old great-aunts (all of whom have passed on now)...and further back, to the women in the family line that I never knew.

Kiffles are a labor-intensive process (as so many of those fine old recipes were), so I have plenty of time to tell the Grandmothers news and stories of the year gone by. This annual ritual centers me in time, place, lineage, and history; it keeps my world turning through the seasons, as all storytelling is said to do. Indeed, in some traditions there are stories that can only be told in the wintertime.

Here in Devon, there are certain "piskie" tales told only in the winter months -- after the harvest is safely gathered in and the faery rites of Samhain have passed. In previous centuries, throughout the countryside families and neighbors gathered around the hearthfire during the long, dark hours of the winter season,  gossiping and telling stories as they labored by candle, lamp, and firelight. The "women's work" of carding, spinning, and sewing was once so entwined with storytelling that Old Mother Goose was commonly pictured by the hearth, distaff in hand.

gossiping and telling stories as they labored by candle, lamp, and firelight. The "women's work" of carding, spinning, and sewing was once so entwined with storytelling that Old Mother Goose was commonly pictured by the hearth, distaff in hand.

In the Celtic region of Brittany, the season for storytelling begins in November (the Black Month of Toussaint), goes on through December (the Very Black Month), and ends at Christmas. (A.S. Byatt, you may recall, drew on this tradition in her wonderful novel Possession.) In early America, some of the Puritan groups which forbade the "idle gossip" of storytelling relaxed these restraints at the dark of the year, from which comes a tradition of religious and miracle tales of a uniquely American stamp: Old World folktales transplanted to the New and given a thin Christian gloss. Among a number of the different Native American nations across the continent, winter is also considered the appropriate time for certain modes of storytelling: a time when long myth cycles are told and learned and passed through the generations. Trickster stories are among the tales believed to hasten the coming of spring. Among many tribes, Coyote stories must only be told in the dark winter months; at any other time, such tales risk offending this trickster, or drawing his capricious attention.

In myth cycles to be found around the globe, the death of the year in winter was echoed by the death and rebirth of the Winter King (also called the Sun King, or Year King), a consort of the Great Goddess  (representing the earth's fertility) in her local guise. The rebirth or resurrection of her consort (representing the sun, sky, or quickening winds) not only brought light back to the world, turning the seasons from winter to spring, but also marked a time of new beginnings, cleansing the soul of sins and sicknesses accumulated in the twelve months passed. Solstice celebrations of the ancient world included the carnival revels of Roman Saturnalia (December 17-24), the Anglo-Saxon vigil of The Night of the Mother to renew the earth's fertility (December 24th), the Yule feasts of the Norse honoring the One-Eyed God and the spirits of the dead (December 25), the Persian Mithric festival called The Birthday of the Unconquered Sun (December 25th), and the more recent Christian holiday of Christmas, marking the birth of the Lord of Light (December 25th).

(representing the earth's fertility) in her local guise. The rebirth or resurrection of her consort (representing the sun, sky, or quickening winds) not only brought light back to the world, turning the seasons from winter to spring, but also marked a time of new beginnings, cleansing the soul of sins and sicknesses accumulated in the twelve months passed. Solstice celebrations of the ancient world included the carnival revels of Roman Saturnalia (December 17-24), the Anglo-Saxon vigil of The Night of the Mother to renew the earth's fertility (December 24th), the Yule feasts of the Norse honoring the One-Eyed God and the spirits of the dead (December 25), the Persian Mithric festival called The Birthday of the Unconquered Sun (December 25th), and the more recent Christian holiday of Christmas, marking the birth of the Lord of Light (December 25th).

Many symbols we associate with Christmas today actually come from older ceremonies of the Solstice season. Mistletoe, holly, and ivy, for instance, were gathered in their magical potency by moonlight on Winter Solstice Eve, then used throughout the year in Celtic, Baltic and Germanic rites. The decoration of evergreen trees can be found in a number of older traditions: in rituals staged in decorated pine groves (the pinea silvea) of the Great Goddess; in the Roman custom of dedicating a pine tree to Attis on Winter Solstice Day; and in the candlelit trees of Norse Yule celebrations, honoring Frey and Freyja in their aspects of Hunter, Huntress, and Protectors of Forests. The Yule Log is a direct descendant from Norse and Anglo-Saxon rites; and caroling, pageantry, mummers plays, eating plum puddings, and exchanging gifts are all elements of Solstice celebrations handed down from the pre-Christian world.

Even the story of the virgin birth of a Divine, Heroic or Sacrificial Son is not a uniquely Christian legend, but one found in cultures all around the globe -- from the myths of Asia, Africa and old Europe to Native American tales. In ancient Syria, for example, a feast on the 25th of December celebrated the Nativity of the Sun; at midnight the sun was born in the form of a child to the Virgin Queen of Heaven, an aspect of the the goddess Astarte.

Likewise, it is interesting to note that the date chosen for New Year's Day in the Western world is a relatively modern invention. When Julius Caesar revised the Roman calendar in 46 BC, he chose January 1 -- following the riotous celebrations of Saturnalia -- as the official beginning of the year. Early Christians condemned the date as pagan, tied to licentious practices, and much of Europe resisted the Julian calendar until the  Gregorian reforms in the 16th century; instead, they celebrated New Year's Day on the 25th of December, the 21st of March, or various other dates. (England first adopted January 1 as New Year's Day in 1752).

Gregorian reforms in the 16th century; instead, they celebrated New Year's Day on the 25th of December, the 21st of March, or various other dates. (England first adopted January 1 as New Year's Day in 1752).

The Chinese, Jewish, Wiccan and other calendars use different dates as the start of the year, and do not, of course, count their years from the date of Christ's birth. Yet such is the power of ritual and myth that January 1st is now a potent date to us, a demarcation line drawn between the familiar past and the unknowable future. Whatever calendar you use, the transition from one year into the next is the traditional time to take stock of one's life -- to say goodbye to all that has passed and prepare for a new life ahead. The Year King is symbolically slain, the sun departs, and the natural world goes dark. Rituals, dances, pageants, and spiritual vigils are enacted in lands around the world to propitiate the sun's return and keep the great wheel of the seasons rolling.

Special foods are eaten on New Year's Day to ensure fertility, luck, wealth, and joy in the year to come: pancakes in France, rice cakes in Ceylon, new grains in India, and cake shaped as boar in Estonia and Sweden, among many others. In my family, we ate the last of those scrumptious kiffles...if they'd managed to last that long. They could not, by tradition, be made again before December of the following year, and so the last bite was always a little sad (and especially delicious). The Christmas tree and decorations were taken down on New Year's Day, and the house was thoroughly cleaned and swept: this was another Pennsylvania Dutch custom, brushing out any bad luck lingering from the year behind, making way for good luck to come.

May you have a lovely winter holiday, in whatever tradition you celebrate, full of all the magic of home and hearth, of oven and table, and of the wild wood beyond.

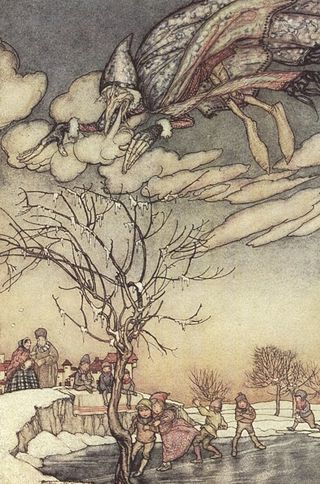

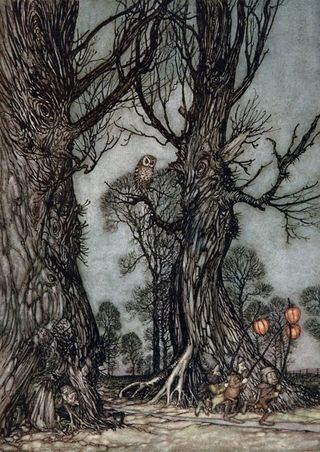

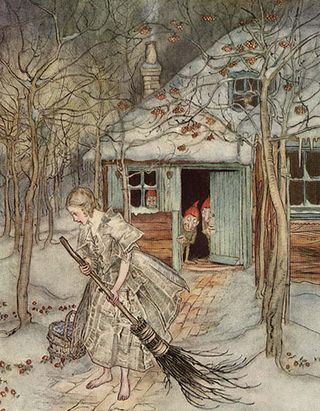

The paintings above are by three great artists of the Golden Age of Book illustration: Arthur Rackham (1867-1939), Edmund Dulac (1882-1953), and Charles Robinson (1870-1937). You'll find titles in the picture captions. (Run your cursor over the images to see them.)

December 21, 2021

On Winter Solstice

Here in the northern hemisphere, as we enter the longest night of the year we are also entering the second winter of the Covid pandemic. The night and the cold seem endless, but the light always does return.

"We are always on a journey from darkness into light," wrote the late Irish poet/philosopher John O'Donohue . "At first, we are children of the darkness. Your body and your face were formed first in the kind darkness of your mother's womb. You lived the first nine months in there. Your birth was the first journey from darkness into light. All your life, your mind lives within the darkness of your body. Every thought you have is a flint moment, a spark of light from your inner darkness. The miracle of thought is its presence in the night side of your soul; the brilliance of thought is born of darkness. Each day is a journey. We come out of the night into the day. All creativity awakens at this primal threshold where light and darkness test and bless each other. You only discover the balance in your life when you learn to trust the flow of this ancient rhythm."

In the mythic sense, we practice moving from darkness into light every morning of our lives. The task now is make that movement larger, to join together to carry the entire world through the long night to the dawn.

The art above is: "Modern Lights, Ancient Flames: Avebury Flames Spirals" by photographer Stu Jenks; ""The Spirit Within" by Karen Davis; "Stray" and "Capturing the Moon" by Jeanie Tomanek. The quote is from Anam Cara (Bantam Books, 1997) by John O'Donhue (1956-2008, Ireland). All right to art and text above are reserved by the artists and John O'Donohue estate.

December 20, 2021

Tunes for the Winter Holidays

There are a lot of good folk albums for the winter holidays (Kate Rusby's Sweet Bells, Emily Smith's Songs for Christmas, Steeleye Span's Winter and Loreena McKennitt's To Drive the Cold Winter Away are all favourites in our house) but for me one CD tops them all: Awake Arise: A Winter Album by Lady Maisery with Jimmy Aldridge & Sid Goldsmith -- a wonderful blend of music and spoken word, and of Christian and pagan folklore.

"Winter is our quietest season," they write. "The winds, the frosts and the raw cold carry echoes of the year that has passed and encourage us to withdraw: to accept the dark and reflect. Our journeys through this time of year are accompanied by a shared imagining of winters past: an ancestral memory of snowy lanes and blazing hearths: of bright winter berries and festive celebrations. These dreams of winter, whether experienced or imagined, anchor us in the season and draw us close together, but they also offer a sense of renewal, encouraging us to look anew towards the rising of spring.

"Awake Arise contains songs, readings and poems that sometimes delve into the dark and sometimes evoke the awakening of a coming year. They tell of the stages of winter, of ancient traditions and customs, of finding hope within the gloom, of love and betrayal, of religion and ceremony, and of seeing our own lives mirrored in the rhythms of the season."

Here is a small sampling from this thoroughly magical album....

Above: "Sing We All Merrily," a song originally collected by Ralph Vaughan Williams in 1918 and reworked here by Hannah James.

Below: "Up in the Morning Early," traditional song collected by Robert Burns, followed by "The Christmas Road" from Laurie Lee's Village Christmas and Other Notes on the English Year.

Above: "Carol Reading/Shortly Before 8:30 PM," followed by "Hail Smiling Morn," a Yorkshire pub carol to banish darkness.

Below: "Da Day Dawn," a Shetland fiddle tune, traditionally played at first light on Christmas morning, followed by "Like as the Thrus in Winter" by Edmond Holmes (1902).

Above: "The Bear Song" by Rowan Rheingans, who says: "This is a song for the turning of the year; some things will return and some things are lost forever."

Below: "Snow Falls," written by John Tams, "a hopeful song of the turning of the seaons and the certainty that from the darkest times the spring will rise again." As we head into our second Covid winter, songs of hope and certainty are welcome indeed.

The wintery fairy tale art above is "The Snow Maiden," "The Wind's Tale" and "Gerda and the Reindeer (from The Snow Queen)" by Edmund Dulac, 1882-1953. Born in France, he emigrated to England early in the 20th century, becoming one of the finest artists in the Golden Age of Book Illustration.

December 17, 2021

The things we lose

So many people I know are struggling with the ache of loss right now -- if not mourning a loved one's death as I am, then the grief that comes from coping with a world pandemic that goes on and on, with climate changes that are escalating, with the unfathomable loss of people, places, and entire species we witness daily. For me, even the small ordinary losses (objects mislaid, papers misplaced, plans cancelled and opportunites missed) seem to bite a little sharper than they used to do, because loss is cumulative. A lost necklace is only a lost necklace, of course, but when such a small thing can bring me to the edge of tears I know it's not an object I am grieving but every damn loss of the last two years.

In her book A Field Guide to Getting Lost, Rebecca Solnit writes:

"It is the nature of things to be lost and not otherwise. Think of how little has been salvaged from the compost of time of the hundreds of billions of dreams dreamt since the language to describe them emerged, how few names, how few wishes, how few languages even, how we don't know what tongues the people who erected the standing stones of Britain and Ireland spoke or what the stones meant, don't know much of the language of the Gabrielanos of Los Angeles or the Miwoks of Marin, don't know how or why they drew the giant pictures on the desert floor in Nazca, Peru, don't know much even about Shakespeare or Li Po.

"It is as though we make the exception the rule, believe that we should have rather than that we will generally lose. We should be able to find our way back again by the objects we dropped, like Hansel and Gretel in the forest, the objects reeling us back in time, undoing each loss, a road back from lost eyeglasses to lost toys and baby teeth. Instead, most of the objects form the secret constellations of our irrecoverable past, returning only in dreams where nothing but the dreamer is lost. They must all still exist somewhere: pocket knives and plastic horses don't exactly compost, but who knows where they go in the great drifts of objects sifting through our world?

"Once I found a locket with a crescent moon and a star spelled out in rhinestones on one face, unreadably intricate initials on another, and two ancient photographs inside, and someone must have missed it terribly but no one claimed it, and I have it still. Another time, traveling down a river in one of the last great wildernesses, a roadless place the size of Portugal, I lost a sock early in the trip and a pair of sunglasses later, and I think of them littering the wilderness so clear of such clutter, there still or found by someone who must have wondered about them as I did the woman with the locket.

"On that trip I leaned over the side of the raft and stared straight down for hours at the floor of the river whose name almost no one knows that flows into another little-known river, stared at thousands of stones sliding by, gray, pink, black, gold, under the clearest water in the whole world, floating for miles and days on water I drank straight out of the river. Material objects witness everything and say nothing. Animals say more. And they are disappearing.

"That things should be lost to our knowledge is one thing, in which we don't know where we are or they are; that things should be lost from the earth is another."

In her wise book Refuge, Terry Tempest Williams writes:

"The eyes of the future are looking back at us and they are praying for us to see beyond our own time. They are kneeling with hands clasped that we might act with restraint, that we might leave room for the life that is destined to come. To protect what is wild is to protect what is gentle. Perhaps the wilderness we fear is the pause between our own heartbeats, the silent space that says we live only by grace. Wilderness lives by this same grace. Wild mercy is in our hands."

Wild mercy for the planet. Wild mercy for ourselves. The dark of the year approaches, dear friends. Let's be kind to each other right now.

The passages above are quote from A Field Guide to Getting Lost by Rebecca Solnit (Viking, 2005) and Refuge: An Unnatural History of Family & Place by Terry Tempest Williams (Pantheon, 2000). All rights reserved by the authors.

A related posts: On the language of loss and love, The writer's god is Mercury, and The dance of joy and grief.

December 16, 2021

On seasons, transitions, and moving forward

Carrying on from Tuesday's post, the second book I've been re-reading this week as a means of coping with grief is The Solace of Open Spaces by Gretel Ehrlich -- a collection of interlinked essays on life in the mountains of Wyoming, where the author settled after the death of the man she'd intended to marry. Ehrlich writes beautifully about land and solitude, about the turn of the seasons and the changes of life. In one essay she describes the waning months of the year in the high mountain country like this:

"The French call the autumn leaf feuille morte. When the leaves are finally corrupted by the frost they rain down into themselves until the tree, disowning itself, goes bald. All through the autumn we hear a double voice: one says everything is ripe, the other says everything is dying. The paradox is exquisite.

"We feel what the Japanese call 'aware' -- an almost untranslatable word that means something like 'beauty tinged with sadness.' Some days we have to shoulder against a marauding melancholy. Dreams have a hallucinatory effect: in one, a man who is dying watches from inside a huge cocoon while stud colts run through deep mud, their balls bursting open, their seed spilling onto the black ground. My reading brings me this thought from the mad Zen priest Ikkyu: 'Remember that under the skin you fondle lie the bones, waiting to reveal themselves." But another day, I ride into the mountains. Against rimrock, tall aspens have the graceful bearing of giraffes, and another small grove, not yet turned, gives off a virginal limelight that transpierces everything heavy....

"Autumn teaches us that fruition is also death; that ripeness is a form of decay. The willows, having stood for so long near the water, begin to rust. Leaves are verbs that conjugate the seasons.

"Today the sky is a wafer. Place on my tongue, it is a wholeness that has already disintegrated; placed under the tongue, it makes my heart beat strongly enough to stretch myself over the winter brilliances to. Now I feel the tenderness to which this season rots. Its defenselessness can no longer be corrupted. Death is its purity, its sweet mud. The string of storms that came to Wyoming like elephants tied trunk to tail falters now and bleeds into stillness."

In another essay, Ehrlich writes of Wyoming's winter months:

"Winter looks like a fictional place, an elaborate simplicity, a Nabokovian invention of rarefied detail. Winds howl all night and day, pushing litters of storm fronts from the Beartooth to the Big Horn Mountains. When it lets up, the mountains disappear. The hayfield that runs east from my house ends up in a curl of clouds that have fallen like sails luffing from sky to ground. Snow returns across the field to me, and the cows, dusted with white, look like snowcapped continents drifting.

"The poet Seamus Heaney said that landscape is sacremental, to be read as text. Earth is instinct: perfect, irrational, semiotic. If I reading winter right, it is a scroll -- the white growing wider and wider like the sweep of an arm -- and from it we gain a peripheral vision, a capacity for what Nabokov calls 'those asides of spirit, those footnotes in the volume of life by which we know life and find it to be good.'

"Not unlike emotional transitions -- the loss of a friend of the beginning of new work -- the passage of seasons is often so belabored and quixotic as to deserve separate names so the year might be divided eight ways instead of four. This fall ducks flew across the sky in great 'V's as if that one letter were defecting from the alphabet, and when the songbirds climbed to the memorized pathways that route them to winter quarters, they lifted off in confusion, like paper scraps blown from my writing room."

Ehrlich relates but does not linger on the death that drove her from New York to Wyoming -- and yet loss and grief are the subtext of every essay in the collection. It's a book about ranching and sheep-herding, yes, but also about the challenge of creating a new life from the ashes of an old. The narrative voice is clear-eyed and unsentimental; it is also reflective and poetic; and the skillful juxtaposition of both modes of writing is one of the reasons I love Ehrlich's work. As she writes in the book's Introduction:

"The truest art I would strive for in any work would be to give the page the same qualities of earth: weather would land on it harshly; light would elucidate the most difficult truths; wind would sweep away obtuse padding. Finally, the lessons of impermanence have taught me this: loss constitutes an odd kind of fullness; despair empties out into an unquenchable appetite for life."

Today's featured artist:

The imagery here is by the great animal photographer Tim Flach, who has "an interest in the way humans shape animals and shape their meaning while exploring the role of imagery in fostering an emotional connection." He is based in London.

The photographs come from Equus (2008), Flach's exquisitely beautiful book on the subject of the horse. His subsequent books are wonderful too: Dog Gods (2010), More Than Human (2012), Evolution (2013), Endangered (2017), Who Am I? (for children, 2019), and Birds (2021).

I urge you to have a look at his website, which not only shows you the breadth of his work but also has one of the best opening pages I've ever seeen....

The photographs above are from Equus by Tim Flach (Abrams, 2008); all rights reserved by the artist. The passages quoted above are from "A Storm, the Cornfield, and Elk," and "The Smooth Skull of Winter," essays published in The Solace of Open Spaces by Gretel Ehrlich (Viking Pengun, 1985); all rights reserved by the author. I also recommend her related books, A Match to the Heart (1994) and Unsolaced (2021).

December 14, 2021

Breaking open

Winter storms are swelling the streams on our hill, and the winter holidays are approaching. It is can be hard to engage with holiday cheer after the death of a loved one, and yet the seasonal rituals are comforting too. To any of you who are also dealing with loss right now -- grieving a family member or friend or animal companion -- I send sympathy and solidarity. My dear relative died six weeks ago, and although the worst of the shock has passed, waves of sorrow still hit with the slightest memory trigger. During such times I am finding sustenance in two favourite books by two remarkable women: Wild Comfort by Kathleen Dean Moore and The Solace of Open Spaces by Gretel Ehrlich. This passage is from Moore's Wild Comfort:

"'There is something infinitely healing in the repeated refrains of nature,' Rachel Carson wrote. 'The assurance that dawn comes after night, and spring after winter.'

"I have never felt this so strongly as I do now, waiting for the sun to warm my back. The bottom may drop out of my life, what I trusted may fall away completely, leaving me astonished and shaken. But still, sticky leaves emerge from bud scales that curl off the tree as the sun crosses the sky. Darkness pools and drains away, and the curve of the new moon points to the place where the sun will rise again. There is wild comfort in the cycles and the intersecting circles, the rotations and revolutions, the growing and ebbing of this beautiful and strangely trustworthy world.

"I settle back on the rock and drag my sleeping bag over my knees. Diffuse light silvers the water; I can just make out a dragonfly nymph that crawls toward the surface with no expectation of flight beyond maybe a tightness in the carapace across its back. No matter how hard it tries or doesn't, there will come a time when the dragonfly pumps the crinkles out of its wings, and there they will be, luminous as mica, threaded with lapis and gold.

"No measure of human grief can stop Earth in its tracks. Earth rolls into sunlight and rolls away again, continents glowing green and gold under the clouds. Trust this, and there will come a time when dogged, desperate trust in the world will break open into wonder. Wonder leads to gratitude. Gratitude into peace."

Where, or how, do you find wild comfort?

The passage quoted above is from Wild Comfort: The Solace of Nature, essays by Kathleen Dean Moore (Trumpeter Books, 2010); all rights reserved by the author.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 710 followers