Terri Windling's Blog, page 143

March 2, 2015

The spirit of place

In his excellent new book Rising Ground, Philip Marsden tramps across the moor and through the woods of Cornwall in search of the "spirit of place," discussing the history and mythology of this ancient land along the way. From Bodmin Moor to Tintangel and Land's End, he explores the many faces of the county: the natural landscape, the sacred landscape, the working landscape of miners and farmers, the Cornwall of antiquarians and artists, and the "spirit of place" as experienced by the author himself, who has lived there for many years.

At the core of the book is Marsden's renovation of a remote farmhouse at the edge of Ruan Creek (a "creek" being a tidal channel or estuary and not a small stream, as Americans use the term). The surrounding woods have reclaimed the crumbled stones of an older settlement, and now Marsden and his family settle in to write a new chapter in the land's long story.

"Our children had been been given a picture book called A Street Through Time: A 12,000-year Journey Along the Same Street," he tells us. "On the first page is a Mesolithic settlement, on the next a Neolithic one, and so on. Every time you turn the page there is the same topography, the same river and the same hill -- but everything else changes. The forest is cut back, huts appear and disappear, defences come and go; early on, a barrow and a stone circle pop up on the hill, fall out of use, and are swallowed up again by the forest; an Iron Age fort becomes a Roman fort among whose ruins a medieval castle is built which is burned down during the Civil War and whose broken walls, on the final page, serve as a visitor attraction. The foreground of the last page is a frenetic scene with cars on the road, planes in the air, wine bars in basements, pedestrians on mobile phones and on the river, a small dredger and a couple in a rowing boat.

"I imagined a version of that narrative here, on the tidal section of the Upper Fal. The first pages would be similar: the shoreside attracting early settlers, the tumulus in our field, the Roman garrison up-river at Golden Mill, the castles at Ruan Lanihorne and Tregony, the church at Lamorran. On the late medieval page, in our little creek, a couple of punts are pulled up on the shingle. A lugger is bringing in maunds of mussels. A small settlement stands on the shore, a scatter of barns and cottages and stock-pens ringed by the enclosure of the demesne lands. The stream drives a small mill. At the center of the scene is a medieval manor -- mullioned windows and high chimneys, and beside it a chapel. The next page is the late eighteenth century: the manor house in poor repair, only partly inhabited, but a new quay on the creek, with a lane running down to it and several people disembarking from a small coaster. Bales of goods lie on the shingle. In the woods across from the river they are felling oak, stripping the bark for the newly expanded tannery.

"It is at this point that our version diverges from the steady modernising in the picture book. The next page here, the mid-nineteenth century, would show the buildings in ruin, and only a much smaller house, our house, among the old walls. Otherwise, the scene is emptying of people, emptying of river traffic. The silting process is beginning to accelerate. On the following pages there are fewer and smaller coasters, then none at all. The quays fall into disrepair, the lime-kilns disappear. The track is less used. There is some activity in the woods, where timber is still taken for the tannery in Grampound, but that comes to an end in the later twentieth century. On the last page are just trees and mud flats, and a cluster of roofs in the wooded emptiness of the valley."

In Marsden's vision, all of Cornwall is a palimpsest, a page over-written by history: readable here, indecipherable there, but beautiful in its layering. Even the section of the county ravaged by clayworks has its stories and its poetry, and the final chapters of the book -- on Lyonesse and the Isles of Scilly -- are pure poetry themselves. It's an unusual book, falling somewhere in the interstices between nature writing, travel writing, history and memoir. By the end, you feel as if you've walked across Cornwall too, and that's a trip worth taking.

If you happen to be within striking distance of Dartmoor, Philip Marsden will be speaking at Chagword, our village's literary festival, on Saturday, March 14 -- and I believe there are still some tickets left. Perhaps I'll see some of you there.

Photographs above: Tilly and I explore the spirit of place in our own Devon hills.

Photographs above: Tilly and I explore the spirit of place in our own Devon hills.

March 1, 2015

Tunes for a Monday Morning

This morning let's step back in time with the help of Oni Wytars, the early music ensemble directed by Marco Ambrosini and Peter Rabanser. The ensemble performs trans-European and Arabic music from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, exploring the ways these traditions have intersected over the centuries. Though the group is based in Germany, its members come from many countries and play a wide range of traditional instruments, including the vielle, rebec, pochette, nyckelharpa, hurdy-gurdy, oud, baglama, harp, shawm, chalumeau, and babgpipes.

Above and below: "Tre Fontane" and "Saltarello," from 14th century Italy.

Above: "Nani, Nani," a Sephardic lullaby beautifully sung by Belinda Sykes.

In addition to her work with Oni Wytars, Sykes is also a medieval music scholar and the director of the English/Israeli/Irish/Arabic ensemble Joglaresa. I highly recommend their 2014 album Nuns and Roses: Medieval Songs of Sin & Subversion (how can you resist that title?), and their other fine albums as well.

It's difficult to find anything but snippets of Joglaresa's music in video form, but here's one lovely recording from 2009 (below): "Al Ahavatcha," a Sephardic song by Spanish-Hebrew poet Rabbi Yehuda Halevi, performed in London. The lead vocalist is Jeremy Avis -- who, coincidentally, used to live here in Chagford. In those days (when we were all so much younger!) he performed with my friend Katy Marchant's early music group, Daughters of Elvin.

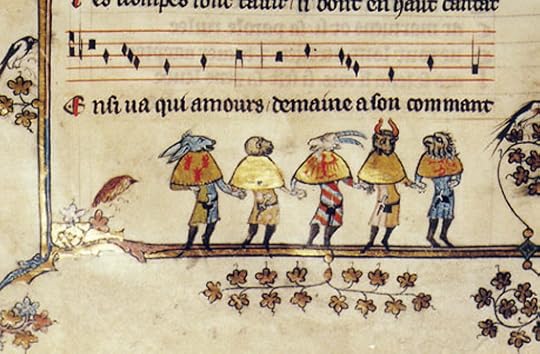

Images above: dancers and mummers from medieval manuscripts.

Images above: dancers and mummers from medieval manuscripts.

February 26, 2015

The magic of hope

From "Myth and History in Fantasy Literature," a lovely essay by O.R. Melling:

"At the heart’s core of fantasy literature lies the infinite possibility of dreams. Whether it presents alternate worlds in outer or inner space, alternate forms of life beyond humanity, alternate realities beyond our own, this genre speaks not to the limited self but to the limitless spirit. The well from which it draws its inspiration -- be it established myth or the capacity for myth-making -- is that which Joseph Campbell calls ‘the lost forgotten living waters of the inexhaustible source.’

"Fantasy literature of the high tradition is a song of hope. It whispers a simple message: as long as the spirit is intact, nothing is broken irreparably. It is idealistic in both the conventional and the Platonic sense and can therefore be a nourishing source for the idealism of youth. Young people are by nature idealistic as, regardless of the hardships they may have already endured, they do not have the accumulation of failures which every adult has gathered through time and experience.

"We as adults can react to youth’s spirit in either a negative or positive way. We can envy or resent their innate optimism and we can discourage it with cynicism, or even actively try to break it. Or we can nurture and encourage that fiery seed in the hopes that this generation might actually win. This generation may not inevitably lose their dreams to disillusionment or defeat. Gottfried von Strassburg, the 13th century author of Tristan, wrote of his work: ‘I have undertaken a labour, a labour out of love for the world, to comfort noble hearts.’

"Fantasy literature is often considered to be simply a form of escapist fiction. Firstly I do not feel that ‘escaping’ is necessarily valueless in itself. As anyone who needs a holiday will attest, escaping can be a form of psychological and psychic regeneration as necessary as sleep. But I would also maintain that anything which encourages dreams and aspirations of a better self or a better world, anything which ‘comforts noble hearts’, is hardly an escape from reality. Rather, it can be an aid to survival and a source of strength, as well as a possible vehicle for improvement. And, as Tolkien pointed out, ‘a living mythology can deepen rather than cloud our vision of reality.’ "

February 25, 2015

The magic of art

"I have always been interested in the way that elements of stories twine and combine. At school I had an art teacher, a great influence on me, who disliked man-made objects unless they were old and showed the effects of time and wear; she loved all natural things. I share this attitude and it plays a large part in my writing. I'm fascinated by the ambiguity of man's relationship to the huge, mysterious universe around him; how, on the one hand, we make ourselves little boxes and think to exist safely and snugly in them; on the other, we extend our knowledge further and further into the limitless void; and yet from time to time these opposites collide and produce astonishing results."

- Joan Aiken (1924-2004)

"[W]hen the modern mythmaker, the writer of literary fairy tales, dares to touch the old magic and try to make it work in new ways, it must be done with the surest of touches. It is, perhaps, a kind of artistic thievery, this stealing of old characters, settings, the accoutrements of magic. But then, in a sense, there is an element of theft in all art; even the most imaginative artist borrows and reconstructs the archetypes when delving into the human heart. That is not to say that using a familiar character from folklore in the hopes of shoring up a weak narrative will work. That makes little sense. Unless the image, character, or situation borrowed speaks to the author’s condition, as cryptically and oracularly as a dream, folklore is best left untapped."

- Jane Yolen (from Touch Magic)

"The dignity of the artist lies in his duty of keeping awake the sense of wonder in the world."

- Marc Chagall (1887-1985)

"My first thought, as a child, was that the artist brings something into the world that didn't exist before, and that he does it without destroying something else. A kind of refutation of the conservation of matter. That still seems to me its central magic, its core of joy."

- John Updike (1932-2009)

Pictures above: the gate, stile, and boundary wall at the bottom of our hill. The poem in the picture captions was first published in Poetry, January 2002; all rights reserved by the author.

Pictures above: the gate, stile, and boundary wall at the bottom of our hill. The poem in the picture captions was first published in Poetry, January 2002; all rights reserved by the author.

February 24, 2015

In the Story Made of Dawn: on magic and magicians

In his excellent book The Spell of the Sensuous, David Abram discusses how being a sleight-of-hand magician gave him an entrée into the world of traditional healers and shamans:

"I traveled to Indonesia on a research grant to study magic," he writes; "more precisely, to study the relation between magic and medicine, first among the traditional sorcerers, or dukuns, of the Indonesian archipelago, and later among the djankris, the traditional shamans of Nepal. The grant had one unique aspect: I was to journey into rural Asia not outwardly as an anthropologist or academic researcher, but as an itinerant magician in my own right, in hopes of gaining a more direct access to the local sorcerers. I had been a professional sleight-of-hand magician for five years, helping to put myself through college by performing in clubs and restaurants throughout New England. I had, as well, taken a year off from my studies in the psychology of perception to travel as a street magician through Europe and, toward the end of that journey, had spent some months in London, working with R. D. Laing and his associates, exploring the potential of using sleight-of-hand magic in psycho-therapy as a means of engendering communication with distressed individuals largely unapproachable by clinical healers. As a result of this work I became interested in the relation, largely forgotten in the West, between folk medicine and magic.

"This interest eventually led to the aforementioned grant, and to my sojourn as a magician in rural Asia. There, my sleight-of-hand skills proved invaluable as a means of stirring the curiosity of the local shamans. Magicians, whether modern entertainers or indigenous, tribal sorcerers, work with the malleable texture of perception. When the local sorcerers gleaned that I had at least some rudimentary skill in altering the common field of perception, I was invited into their homes, asked to share secrets with them, and eventually encouraged, even urged, to participate in various rituals and ceremonies.

"But the focus of my research gradually shifted from a concern with the application of magical techniques in medicine and ritual curing, toward a deeper pondering of the traditional relation between magic and the natural world."

Scott London goes deeper into this aspect of David's work in the following passages from his illuminating intervew, "The Ecology of Magic":

London: You have used the phrase "boundary keeper" to describe the magician. What do you mean by that?

Abram: I discovered that very few of the medicine people that I met considered their work as healers to be their primary role or function for their communities. So even though they were the healers, or the medicine people, for their villages, they saw their ability to heal as a by-product of their more primary work. This more primary work had to do with the fact that these magicians rarely live at the middle of their communities or in the heart of the village. They always live out at the edge or just outside of the village -- out among the rice paddies or in a cluster of wild boulders -- because their skills are not encompassed within the human modality. They are, as it were, the intermediaries between the human community and the more-than-human community -- the animals, the plants, the trees, even whole forests are considered to be living, intelligent forces. Even the winds and the weather patterns are seen as living beings. Everything is animate. Everything moves. It's just that some things move slower than other things, like the mountains or the ground itself. But everything has its movement, has its life. And the magicians were precisely those individuals who were most susceptible to the solicitations of these other-than-human shapes. It was the magicians who could most easily enter into some kind of rapport with another being, like an oak tree, or with a frog.

London: What sort of rapport?

Abram: Every magician that I met had a number of animals or plants or forms of nature that were their close familiars. Just as we speak of the witch's black cat as her "familiar," so in these animistic societies the magician might have crows and frogs and perhaps a certain kind of rubber plant as his familiars. It might also be a certain kind of storm -- a thunder-storm -- a being that, when it appeared in the sky, would tell the magician that it was time to go outside and just gaze at those clouds and learn from them what they might have to teach.

London: In the same way, perhaps, that horses can sense an impending earthquake.

Abram: Right. Other animals function for the magician as another set of senses, another angle from which he can see and hear and sense what's going on in the surrounding ecology, because we are limited by our human senses, our nervous-system, and our two arms and our two legs. Birds know so much more about what's going on in the air, in the invisible winds, than we humans can know. If we watch the birds closely, we can begin to learn about what's going on in the sky and in the air simply by watching their flight patterns.

London: Where do they draw the boundary between magic and reality?

Abram: That boundary is not drawn in traditional cultures. In indigenous, tribal, or oral cultures, magic is the way of the world. There is nothing that is not in some way magic, because the fact that the world exists is already quite a wonder. That it stays existing, that it continually keeps holding itself in existence, this is the mystery of mysteries. Magic is the way of the world. It's that sense of being in contact with so many other shapes of awareness, most of which are so different from our own, that is the basic experience of magic from which all other forms of magic derive.

London: What happens to a culture bereft of magic?

Abram: One thing is that its relation to the natural landscape is tremendously impoverished. In fact, by our obliviousness, by our forgetfulness of all of these other styles of awareness -- the other animals, the plants, the waters -- we have brought about a crisis in the natural world of unprecedented proportions -- not out of any meanness, but simply because we really don't recognize that nature is there. It seems to us, in our culture, to be a kind of passive backdrop against which all of our human events unfold, and it's human events that are meaningful and what happens in nature, well, we don't really notice it, it's not really there. It's not vital. How different that is from the awareness of a magical or animistic culture for whom everything we do as humans is so profoundly influenced by our interactions with the earth underfoot and the air that swirls around us and the other animals.

London: You said that some field biologists are able to capture the essence of magic in their work. I can think of some nature writers who also serve that same function -- people like Peter Mathiessen, Terry Tempest Williams, and Barry Lopez.

Abram: Absolutely. I do think that some of the nature writers are doing an exquisitely important work of magic. They are doing what we might think of as "word magic" -- very carefully taking up the language and trying to use it in new ways, trying to work out how to speak without violating our kinship with the rest of the animate earth.

* * *

I agree with David on this, but I would add that there are mythic fiction writers who are doing the important work of "word magic" too.

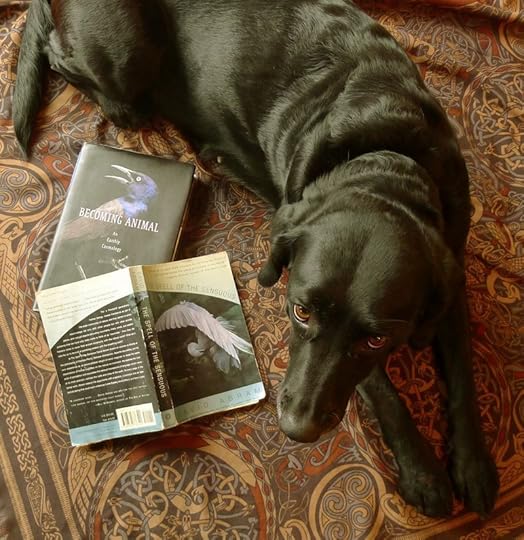

I recommend reading Scott London's interview in full, and I also highly recommend David's two books if you haven't come across them already: The Spell of the Sensuous and Becoming Animal. Photographs above: climbing the hills at dawn in golden post-rain light.

I recommend reading Scott London's interview in full, and I also highly recommend David's two books if you haven't come across them already: The Spell of the Sensuous and Becoming Animal. Photographs above: climbing the hills at dawn in golden post-rain light.

Under the Skin of the World: on myth and magic

"The ancient world was full of magic," writes novelist C.J. Cherryh. "Most everyone north and northwest of the Mediterranean believed that standing barefoot on the earth gave you special knowledge, that the prickling feeling at the back of your neck meant watchers in the wood, and that running water cleansed supernatural flaws.

"True magic, magic as our ancestors practiced it, contained very little concept of good or evil as the modern world understands such terms. The ancient world understood powers, and Powers, and believed that if you should trespass beyond the natural and convenient boundaries of your birth and natural status, as very little prevents you from doing, you must enter into the natural and convenient boundaries of Something Else...which may resent your presence, may be curious about you, or may deal with you in ignorance perilous to both. On the one hand, that ancient belief encouraged the timid to stay by their own firesides. On the other, it placed no barriers of class or skill or gender between the adventuresome and the adventure.

"That was the real ancient world -- a period in which I have some background," Cherryh continues. "My study in university was the ancient Mediterranean, and that interest led me into both Egyptian and Celtic lore, which led... everywhere, ultimately.

"What can the ancient world offer a modern world that has encroached so recklessly into the deep forests and the sea, and by ax and fire and iron brought the Powers of domestic fields up against those of the wild places? It can offer encounter, strange meetings with the not-evil, not-good, and an examination of one's own actions. It can teach one to look under bushes and beside trails, and listen in the Wild and not chatter. It can teach us what our ancestors knew: that you can't divide nature into good and evil, that you can't speak to the earth politely if you've only gone shod and on concrete, and that you can't know the wild countryside if you roar through it in glass and steel on asphalt ribbons.

"The ancient world can teach us, too, as Virgil suggested, 'Forsan et haec olim meminisse iuvabit,' that adventures are most pleasant to contemplate not while rain is dripping down one's neck, but when one is safe and warm at home, and confident of supper."

"I believe in the power of myth to inform our lives and illuminate our common path," says novelist Stephen R. Lawhead. "Unfortunately, the myths we receive at long remove are often so sullied and shopworn that their power has ceased to flow. As a writer, I find I spend considerable time and effort trying to rescue the mythic spirit of the stories I tell, and then restore both shape and substance to their rightful prominence so that the myth's inherent power can flow....

"The myths and legends of long ago are meant to show us who we are and what we may become, and to point out the pitfalls along the way to our final destination. We are travelers on a spiritual journey. There are guides and spirits along the way to befriend us -- if our eyes are open and our hearts are willing."

Pictures above: The waterfall on our hill, running fast with winter rain, green even in the cold months with moss, lichens, ferns and holly.

Pictures above: The waterfall on our hill, running fast with winter rain, green even in the cold months with moss, lichens, ferns and holly.

On myth and magic

"The ancient world was full of magic," writes novelist C.J. Cherryh. "Most everyone north and northwest of the Mediterranean believed that standing barefoot on the earth gave you special knowledge, that the prickling feeling at the back of your neck meant watchers in the wood, and that running water cleansed supernatural flaws.

"True magic, magic as our ancestors practiced it, contained very little concept of good or evil as the modern world understands such terms. The ancient world understood powers, and Powers, and believed that if you should trespass beyond the natural and convenient boundaries of your birth and natural status, as very little prevents you from doing, you must enter into the natural and convenient boundaries of Something Else...which may resent your presence, may be curious about you, or may deal with you in ignorance perilous to both. On the one hand, that ancient belief encouraged the timid to stay by their own firesides. On the other, it placed no barriers of class or skill or gender between the adventuresome and the adventure.

"That was the real ancient world -- a period in which I have some background," Cherryh continues. "My study in university was the ancient Mediterranean, and that interest led me into both Egyptian and Celtic lore, which led... everywhere, ultimately.

"What can the ancient world offer a modern world that has encroached so recklessly into the deep forests and the sea, and by ax and fire and iron brought the Powers of domestic fields up against those of the wild places? It can offer encounter, strange meetings with the not-evil, not-good, and an examination of one's own actions. It can teach one to look under bushes and beside trails, and listen in the Wild and not chatter. It can teach us what our ancestors knew: that you can't divide nature into good and evil, that you can't speak to the earth politely if you've only gone shod and on concrete, and that you can't know the wild countryside if you roar through it in glass and steel on asphalt ribbons.

"The ancient world can teach us, too, as Virgil suggested, 'Forsan et haec olim meminisse iuvabit,' that adventures are most pleasant to contemplate not while rain is dripping down one's neck, but when one is safe and warm at home, and confident of supper."

"I believe in the power of myth to inform our lives and illuminate our common path," says novelist Stephen R. Lawhead. "Unfortunately, the myths we receive at long remove are often so sullied and shopworn that their power has ceased to flow. As a writer, I find I spend considerable time and effort trying to rescue the mythic spirit of the stories I tell, and then restore both shape and substance to their rightful prominence so that the myth's inherent power can flow....

"The myths and legends of long ago are meant to show us who we are and what we may become, and to point out the pitfalls along the way to our final destination. We are travelers on a spiritual journey. There are guides and spirits along the way to befriend us -- if our eyes are open and our hearts are willing."

Pictures above: The waterfall on our hill, running fast with winter rain, green even in the cold months with moss, lichens, ferns and holly.

Pictures above: The waterfall on our hill, running fast with winter rain, green even in the cold months with moss, lichens, ferns and holly.

February 23, 2015

The weather of creativity

One minute, the snow is falling fast: fat flakes dissolving at the ground's warm touch.

In the next minute, the sun returns to light up the green valley below.

The weather report reads: Changeable.

And we are changeable too. As we write, as we paint, as we create we move from joy to despair and back a hundred times. The creative process is not a straight road but a precarious path of mist and snow, formed out of our attention, intention, and the tension between two opposite states. We step onto the path as warily as Wily E. Coyote stepping out into thin air...but unlike him, we can look down. Far below, our loved ones, mentors, ancestors, and community of mythic artists, past and present, stand arm-in-am to catch us if we fall.

We won't fall. You won't fall. So trust the path.

And keep on going.

Tilly's poem for the day: "Nunaqtigiit," by Inuit poet Joan Kane.

February 22, 2015

Tunes for a Monday Morning

Something a little different today: the music of Inuit "throat singer" Tanya Tagaq.

As a recent article in The New Yorker explains: "In her work, which includes collaborations with Björk and the Kronos Quartet, Tagaq uses breath and, more recently, vocalized shrieks and moans. She is known throughout Canada (her home is in Yellowknife, in the Northern Territories), and she won the 2014 Polaris Prize, beating out Drake and Arcade Fire. The album, Animism, has just been released Stateside -- her first U.S. record.

"Tagaq's mother was born and raised in an igloo on Baffin Island, in Nunavut Territory, but Tagaq, whose father is British and Polish, grew up in a house, in Cambridge Bay. She didn't hear throat singing until her mother gave her a cassette of two Inuit women doing it in the traditional manner, as a duet. 'I heard the land in the voices,' Tagaq explained." She then set out to learn how to throat sing herself -- first as a personal obsession, and then in professional performance from 2003 onwards, exploring the sound in combination with other musical forms from classical compositions to jazz and hip-hop.

In the video above, the singer discusses and demonstrates the tradition she's working in.

The video below chronicles the creation of "A String in Her Throat," her 2011 collaboration with The Kronos Quartet.

And last:

"Tungijuq," a short film directed by Paul Raphaël and Félix Lajeunesse (2009). They describe it as "an organic expression of Inuit culture and traditional practices, featuring throat singer Tanya Tagaq as she goes through a transformation from human to animal."

It's strange, magical, and (be forewarned) a little bloody. Not our usual Monday morning fare, but haunting and deeply rooted in myth.

February 19, 2015

The subtle element of time

Here's another lovely passage from Arctic Dreams by Barry Lopez, this one on the nature of time:

"Long, unpunctuated hours pass for all creatures in the Arctic. No wild frenzy of feeding distinguishes the short summer. But for the sudden movement of chasing wolves and bolting caribou, the gambols of muskox calves, the scamper of an arctic fox, the swoop of a jaeger, the Arctic is a long, unbroken bow of time. Twilight  lingers. There are no summer thunderstorms with bolts of lightning. The ice floes, the caribou, the muskoxen, all drift. To lie on your back somewhere on the light-drowned tundra of an Ellesmere Island valley is to feel that the ice ages might have ended but a few days ago. Without the holler of contemporary life, that constant disturbance, it is possible to feel the slope of time, how very far from Mesopotamia we have come.

lingers. There are no summer thunderstorms with bolts of lightning. The ice floes, the caribou, the muskoxen, all drift. To lie on your back somewhere on the light-drowned tundra of an Ellesmere Island valley is to feel that the ice ages might have ended but a few days ago. Without the holler of contemporary life, that constant disturbance, it is possible to feel the slope of time, how very far from Mesopotamia we have come.

"We move at such a fast clip now. We draw up geological charts in a snap, showing the possibilities for oil in Tertiary rocks in the Sverdrup Basin beneath Ellesmere's tundra. We delineate the life history of the ground squirrel. We list the butterflies: the sulphers, the arctics, a copper, a blue, the lesser fritillaries. At a snap. We enumerate the plants. We name everything. Then we fold the charts and the catalogs, as if, except for a stray fact or two, we were done with a competent description. But the land is not a painting; the image cannot be completed this way.

"Lying on your back on Ellesmere Island on rolling tundra without human trace, you can feel the silence stretching all the way to Asia. The winter face of a muskox, its unperturbed eye glistening in a halo of snow-crusted hair, looks at you over a cataract of time, an image that has endured through all the pulsations of ice.

"You can sit for a long time with the history of man like a stone in your hand. The stillness, the pure light, encourage it."

Jay Griffiths has this to say on the subject of time in her engrossing book on the subject, Pip Pip:

"Amongst many peoples, 'Time' is a matter of timing. It involves spontaneity rather than scheduling, sensitivity to a quality of time. Unclockable. The San Bushmen of the Kalahari do not plan when to hunt, but rather ‘wait for the moment to be lucky', reading and assessing animal patterns, looking for the 'right' time. Timing for many indigenous peoples, for example, the Ilongot of the Philippines, is variable and  indeterminate and unpredictable. Time is a subtle element where creativity and improvisation, flexibility, fluidity and responsiveness can flourish. People's responses to timing issues are subtle and graceful. But the dominant culture, far from respecting these socially graceful ideas of time, chooses to refer disparagingly to being 'on Mexican time,' 'on Maori time', 'on Indian time.'

indeterminate and unpredictable. Time is a subtle element where creativity and improvisation, flexibility, fluidity and responsiveness can flourish. People's responses to timing issues are subtle and graceful. But the dominant culture, far from respecting these socially graceful ideas of time, chooses to refer disparagingly to being 'on Mexican time,' 'on Maori time', 'on Indian time.'

"What subverts the dead hand of the dominant clock? Life itself. The elastic, chancy, sensitive times chosen for hunting depend on living things: how the living moment smells. There is a 'biodiversity of time' imaged in cultures around the world, time as a lived process of nature. There is a scent-calendar in the Andaman forests, star-diaries for the Kiwi peoples of New Guinea and Aboriginal Australians who begin the cultivation season when the Pleiades appear. In Rajasthan a moment of evening is called 'cattle-dust time,' the Native American Lakota people have the 'Moon of the Snowblind.' One indigenous tribe in Madagascar refers to a moment as 'in the frying of a locust.' The English language still remembers time intrinsically connected to nature, doing something 'in two shakes of a lamb's tail' or the (arbitrary and sadly obsolete) phrase 'pissing-while.'

"For nature shimmers with time; and interestingly, many areas rich in myth and indigenous history are shown to be places of high biodiversity; living history, life at its liveliest. Both past and present equally vivacious, in a vital land."

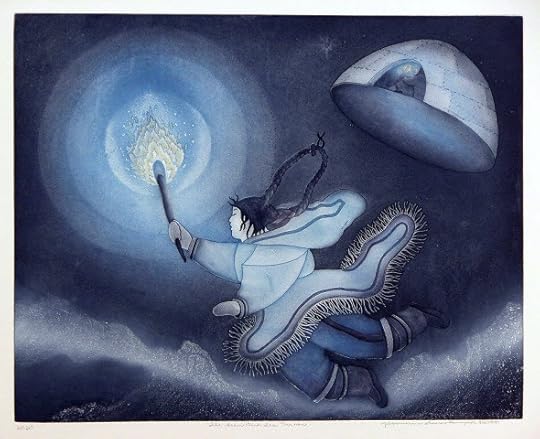

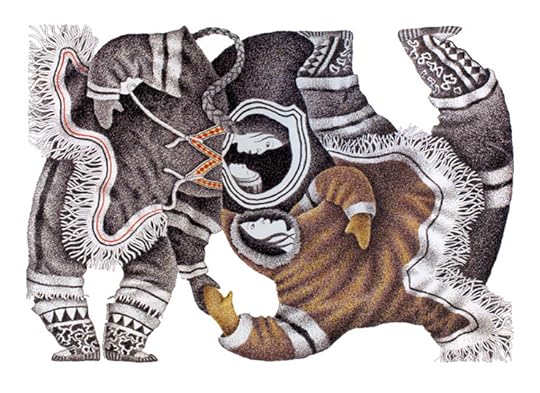

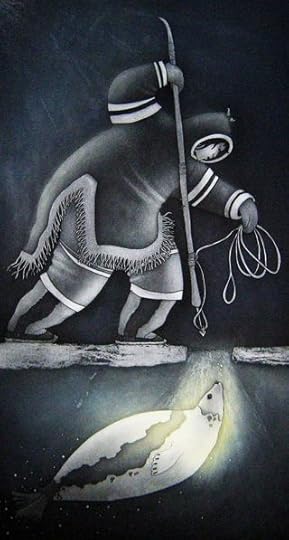

The art today is by the contemporary Inuit painter and printmaker Germaine Arnatauyck. Born near Igloolik, Nunavut in 1946, Arnatauyck was raised in a traditional hunting camp, educated at a Catholic mission school, then studied fine art at the University of Manitoba, graphic art at Algonquin College in Ottawa, and printmaking at Arctic College in Nunavut. Her work is inspired by Inuit myth, particularly women's stories. "I never questioned being an artist," she says. "I guess I was lucky. It seemed I knew exactly what I wanted to be."

The titles of Arnatauyck's prints can be found in the picture captions.

The titles of Arnatauyck's prints can be found in the picture captions.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers