Terri Windling's Blog, page 141

April 2, 2015

This wee Easter bunny is a gift for you, Gentle Readers...

This wee Easter bunny is a gift for you, Gentle Readers, with my permission to download it and print it out if you're so inclined. I'll be out of the studio and offline over the long holiday weekend, and back on Tuesday.

April 1, 2015

Storytelling and wild time

"The trajectory of life, the concept of universal death, conditions our thinking," writes Penelope Lively in her most recent memoir, Ammonites & Leaping Fish: A Life in Time. "We require things to end, to mirror our own situation. I have had much to do with endings, as a writer of fiction. The novel moves from start to finish, as does the short story; at the outset, the conclusion lurks -- where is this thing going? how will I wrap it up? how will I give it a satisfactory shape? You are looking to supply the deficiencies of reality, to provide order where life is a matter of contingent chaos, to suggest theme and meaning, to make a story that is shapely where life is linear.

" 'Tick-tock': Frank Kermode's famous model of what we call a plot, an organization that humanizes time by giving it form.'The need to give significance to simple chronology.' All such plotting presupposes and requires that an end will bestow upon the whole duration and meaning.'This is the satisfaction of a successful work of fiction -- the internal coherence that reality does not have. Live as lived is disordered, undirected and at the mercy of contingent events.

"We have a need for narrative, it seems. A life is indeed a tick-tock: birth and death with nothing but time in between. We go to fiction because we like a story, and we want our lives to have the largesse of story, the capacity, the onward thrust -- we not only want, but need, which is why memory is so crucial, and without it we are lost, adrift in a hideous eternal present....

"We cannot but see the trajectory from youth to old age as a kind of story -- my story, your story -- and the backward gaze of old age is much affected by the habits of fiction. We look for the sequential comforts of narrative -- this happened, then that; we don't care for the arbitrary. My story -- your story -- is a matter of choice battling with contingency: 'The best-laid schemes o' mice an' men...' We are well aware of that, but the retrospective view would still like a bit of fictional elegance. For some, psychoanalysis perhaps provides this -- explanations, understandings. Most of us settle for the disconcerting muddle of what we intended and what came along, and try to see it as some kind of whole.

"That said, it remains difficult to break free of the models supplied by fiction. ' The preference for progress is a basic assumption of the Bildungsroman and the upward mobility story, and an important component of much comedy, romance, fairy tale,' writes Helen Small in her magisterial investigation of old age as viewed in philosophy and literature, The Long Life. ' It is also an element in the logic of tragedy: one of the reasons tragedy (certain kinds, at least) is painful is that it affronts the human desire for progress.' We are conditioned by reading, by film, by drama, with, it occurs to me, long-running television soaps being the only salutary reminder of what real life actually does -- it goes on and on as a succession of events until the plug is pulled; we should note the significance of Coronation Street and EastEnders. We want some kind of identifiable progress, a structure, and the only one is the passage of time, the notching up of decades until the exit line is signalled."

In contrast to linear clock-time, through which we in the industrialized West have learned to view our lives and construct our stories, Jay Griffiths describes "mythic time" and "wild time" in her wide-ranging book Pip Pip: A Sideways Look at Time:

"Mythic stories talk time out of mind, charm and trick time, clogging or stretching it: fables make time fabulously paradoxical, a stubborn blot on the face of clock-time but true to the time of the psyche, where past, present and future are kaleidoscoped. Time can run anti-clockwise so the youngest child succeeds where the oldest fails, the dawn can be wiser than the dusk and birds can tell the future. Certain periods of time -- three days, a year and a day, seven years and a hundred years -- are enchanted. In these archetypal tales all over the world, 'sensible' time disappears into a wrinkle; a person dips into a fairy hill or disappears for a night with dwarves, but on their return finds that, Rip Van Winklish, a hundred ordinary years have passed.

"The Inuit tell tales which begin 'long ago, in the future,' which is a beautiful expression of mythic time playing trickster to linear, logical conceptions. But all fairy tales play with time, from 'Once upon a time' to 'lived happily ever after.' Once tells of a past eternal, but the eternity it refers to is also a charmed present, just at one remove from now. French folk tales can begin 'Il y a une fois,' meaning some time ago, while il y a actually means 'there is.' This is the eternal-present tense , an enchanted present-continuous, a time in the past that still exists. The present, 'now and ever after,' is the present continuing, life everlasting, and even though the individual action is narrated and complete -- 'that's all folks' -- yet life goes on, ever after, back in the now.

"Mythic stories face death, time's most ferociously fearful aspect, and charm the sting out of it for this reason: the individual tale ends, myths imply, so the individual life story must end in death, but the life of the species lives from ever-before to ever-after. The consolation of life's continuing is most explicit in this Aboriginal Dreamtime myth: 'And so death comes, but life always returns.' Their transcendence of death is achieved in part by the archetypal nature of the characters of myths and folk tales; the totemic Dreamtime figures, the Jack and Jill of folk tales, even the Everyman of Morality Plays. Further, the tales themselves become 'immortal,' living stories retold from generation to generation in an oral culture, from ceilidh to corroboree."

Jeanette Winterson notes that as Western clock-time and lives speed up, urged ever faster by the restless, relentless gods of productivity, profit, and technology, this speed seeps into our narrative arts; and she makes a plea for letting fiction, and life, unfold at a more natural pace.

"Nobody would would expect to play a piece of music at twice the speed of the score and be able to enjoy it," she writes. "Yet, in literature this is happening all the time. The reader chooses the pace without taking the trouble to first pick up the rhythm. To get used to a writer's rhythm, to move with a writer's own beat, needs a little more time. It means looking at the opening pages carefully. It can be helpful to read them out loud. Much of the delight everyone gets from radio adaptations of the classics is a straightforward delight in pace. The actors read much more slowly than the eye passes, especially the eye habituated to scanning the daily papers and skipping through the magazines. It is just not possible to read literature quickly. Neither poetry nor poetic fiction will respond to being rushed....It seems so obvious, this question of pace, and yet it is not. Reviewers, who can never waste more than an hour with a book, are the most to blame. Journalism encourages haste; haste in the writer, haste in the reader, and haste is the enemy of art. Art, in its making and in its enjoying, demands long tracts of time. Books, like cats, do not wear watches.

"Over and above all the individual rhythms of music, pictures and words, is the rhythm of art itself."

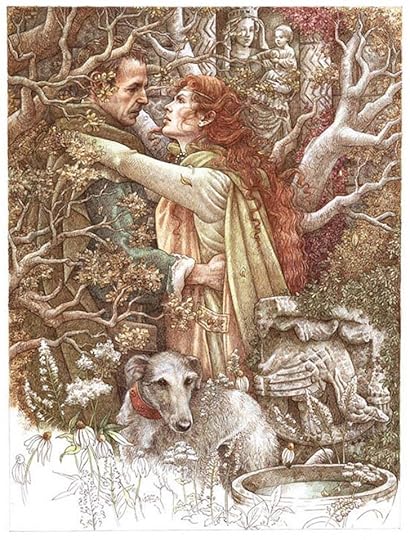

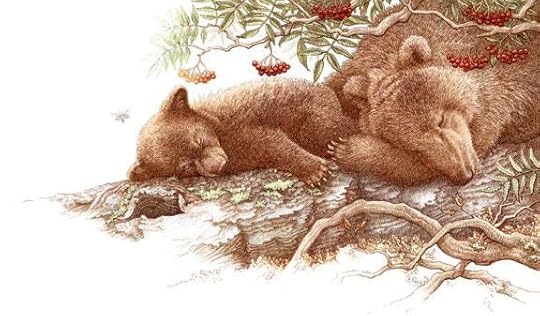

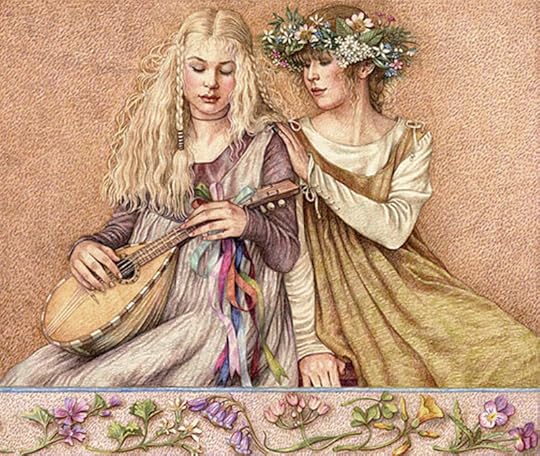

The art here today, with its gentle and timeless rhythm, is by the award-winning Britist artist and illustrator Anne Yvonne Gilbert. Raised in Northumberland (in north-east England), Gilbert studied at Newcastle College and the Liverpool College of Art, and has worked as an illustrator and graphic artist since the late 1970s. She has published many beautiful children's books; provided cover art for fantasy classics by Diana Wynne Jones, Ursula K. Le Guin, Peter Dickinson, and John Crowley, among others; and designed everything from album covers to postage stamps -- working primarily with colored pencils and inks. (She considers herself more of a "drawer" than a painter.) I recommend her lovely illustration blog if you'd like to know more about her creative process.

Text sources: Ammonites & Leaping Fish by Penelope Lively (Pengiun Books, 2014); Pip Pip by Jay Griffiths (HarperCollins, 1999), and Art Objects by Jeanette Winterson (Random House, 1995).

Where the wild things are

From Sylvia Lindsteadt's fine essay "Turning Our Fairy Tales Feral Again" (written for The Dark Mountain Project and reprinted in Resilience):

"Humans are storytelling creatures. We need story, we need deep mythic happenings, as much as we need food and sun: to set us in our place in the family of things, in a world that lives and breathes and throws us wild tests, to show us the wildernesses and the lakes, the transforming swans, of our own minds. These minds of ours, after all, are themselves wild, shaped directly by our long legacy as hunters, as readers of wind, fir-tip, animal trail, paw-mark in mud. We are made for narrative, because narrative is what once led us to food, be it elk, salmonberry or hare; to that sacred communion of one body being eaten by another, literally transformed, and afterward sung to.

"The narratives we read, and watch, and tell ourselves about the relationship between humans and nature have cut out the voices of all wild things. They’ve cut out the breathing world and made us think we are alone and above. If these narratives don’t change -- if the elk and the fogs don’t again take their places and speak -- all manner of policies, conservation efforts and recycling bins won’t be worth a damn. We live in a world where, despite our best intentions, the stories we read -- literary, fantasy, science fiction, mystery, horror, poetry -- are almost wholly human-centric. Wild places and animals and weather patterns are stage sets, the backdrop, like something carved from plywood and painted in. They have no voice, no subjective truth. In our dominant narratives, we are not one of many peoples -- grass people, frog people, fox people -- as the Hupa Indians of the Klamath River region say. We are the only people.

"This makes sense on one level, as we live in a world in which we believe the only things that are truly and wholly animate are ourselves. Mostly all of what we have been taught is predicated on this assumption. On another level, this is complete lunacy, complete insanity. At what point did we loose the sense of stories and myths actually arising from the world around us, its heartbeats, its bloodflows, its bat-eared songs?"

(Read the full piece here.)

"At some point, one asks, 'Toward what end is my life lived?' " writes Diane Ackerman in The Rarest of the Rare: Vanishing Animals, Timeless Worlds. "A great freedom comes from being able to answer that question. A sleeper can be decoyed out of bed by the sheer beauty of dawn on the open seas. Part of my job, as I see it, is to allow that to happen. Sleepers like me need at some point to rise and take their turn on morning watch for the sake of the planet, but also for their own sake, for the enrichment of their lives. From the deserts of Namibia to the razor-backed Himalayas, there are wonderful creatures that have roamed the Earth much longer than we, creatures that not only are worthy of our respect but could teach us about ourselves.”

"Storytellers ought not to be too tame," Ben Okri advises in his inspiring essay collection A Way of Being Free. "They ought to be wild creatures who function adequately in society, They are best in disguise. If they lose all their wildness, they cannot give us the truest joys."

"When we walk, holding stories in us, do they touch the ground through our footprints?" asks Sylvia Linsteadt. "What is this power of metaphor, by which we liken a thing we see to a thing we imagine or have seen before -- the granite crag to an old crystalline heart -- changing its form, allowing animation to suffuse the world via inference? Metaphor, perhaps, is the tame, the civilised, version of shamanic shapeshifting, word-magic, the recognition of stories as toothed messengers from the wilds. What if we turned the old nursery rhymes and fairytales we all know into feral creatures once again, set them loose in new lands to root through the acorn fall of oak trees? What else is there to do, if we want to keep any of the wildness of the world, and of ourselves?"

"The word 'feral' has a kind of magical potency," said T. H. White (in a letter to a friend, 1937).

And it does indeed.

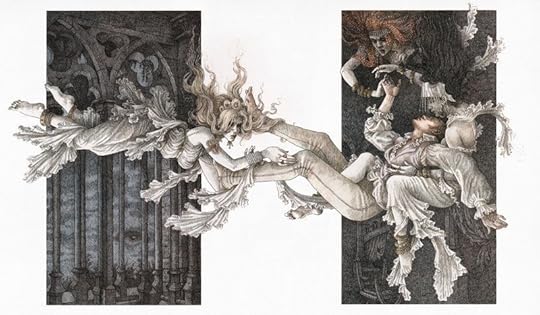

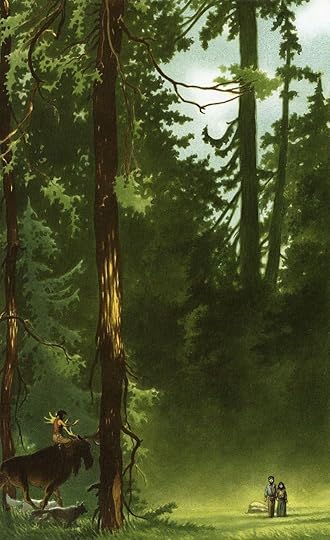

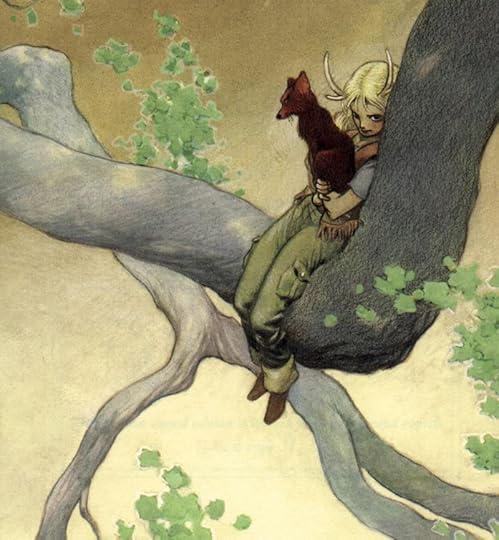

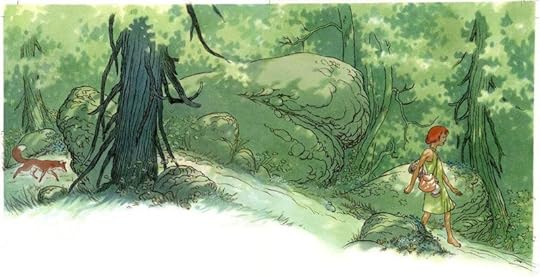

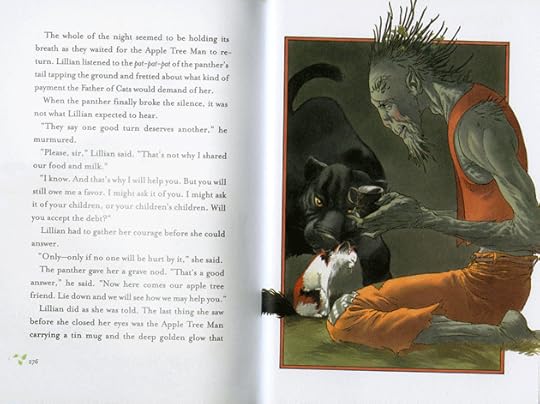

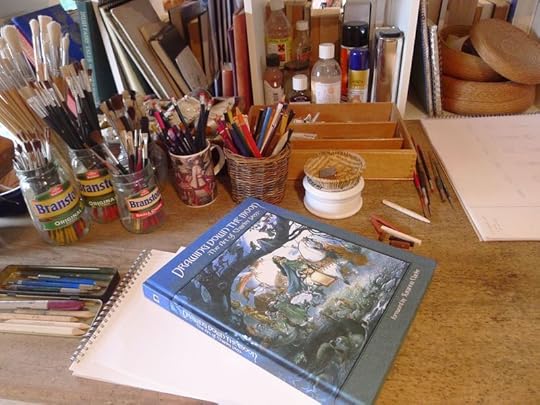

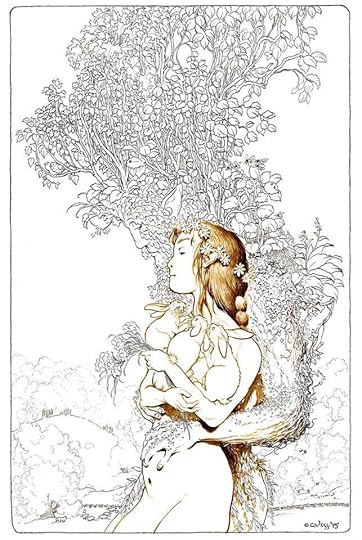

The gloriously wild art here is by Charles Vess, of course -- one of the great storytellers and mythic artists of our age. Charles and I grew up together in the fantasy field in New York City in the 1980s; he now lives and works in wild hills of rural Virginia. I highly recommend Dark Horse Books' beautiful publication Drawing Down the Moon: The Art of Charles Vess, along with his many illustrated books and comics. Please visit Charles' Green Man Press website to see more his art.

Artworks above: ''She Came Out of the Forest Like a Ghost," two works in progress: ''The Winter King'' & ''The King of the Summer Country and His Bride of Flowers," and illustrations for "Medicine Road" and "The Cats of Tanglewood Forest" by Charles de Lint.

Artworks above: ''She Came Out of the Forest Like a Ghost," two works in progress: ''The Winter King'' & ''The King of the Summer Country and His Bride of Flowers," and illustrations for "Medicine Road" and "The Cats of Tanglewood Forest" by Charles de Lint.

March 30, 2015

Telling our stories

“I believe in all human societies there is a desire to love and be loved, to experience the full fierceness of human emotion, and to make a measure of the sacred part of one's life. Wherever I've traveled -- Kenya, Chile, Australia, Japan -- I've found the most dependable way to preserve these possibilities is to be reminded of them in stories. Stories do not give instruction, they do not explain how to love a companion or how to find God. They offer, instead, patterns of sound and association, of event and image. Suspended as listeners and readers in these patterns, we might reimagine our lives." - Barry López (About This Life)

"I come from a long line of tellers: mesemondok, old Hungarian women who tell while sitting on wooden chairs with their plastic pocketbooks on their laps, their knees apart, their skirts touching the ground...and cuentistas, old Latina women who stand, robust of breast, hips wide, and cry out the story ranchera style. Both clans storytell in the plain voice of women who have lived blood and babies, bread and bones. For them, story is a medicine which strengthens and arights the individual and the community." - Clarissa Pinkola Estés (Women Who Run With the Wolves)

"Make up a story.

"Narrative is radical, creating us at the very moment it is being created. We will not blame you if your reach exceeds your grasp; if love so ignites your words they go down in flames and nothing is left but their scald. Or if, with the reticence of a surgeon's hands, your words suture only the places where blood might flow. We know you can never do it properly -- once and for all. Passion is never enough; neither is skill. But try. For our sake and yours forget your name in the street; tell us what the world has been to you in the dark places and in the light. Don't tell us what to believe, what to fear. Show us belief's wide skirt and the stitch that unravels fear's caul."

- Toni Morrison (Nobel Prize acceptance speech, 1993)

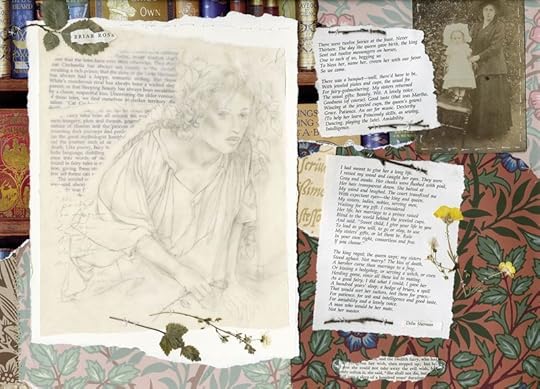

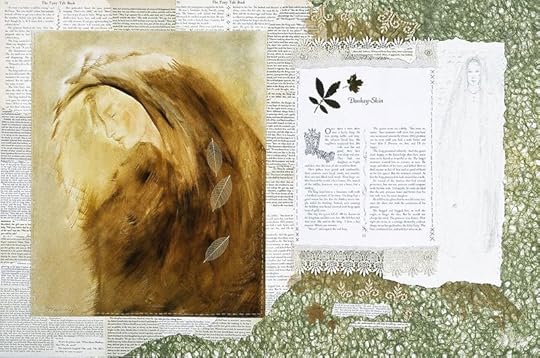

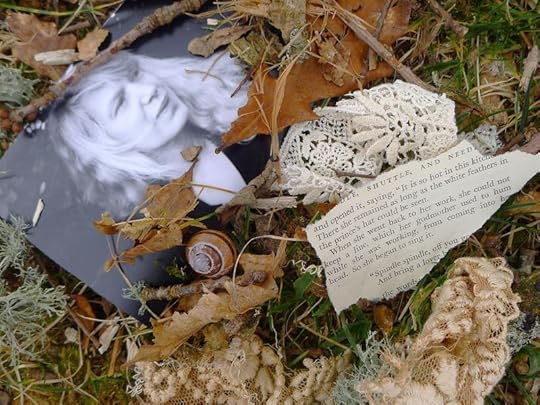

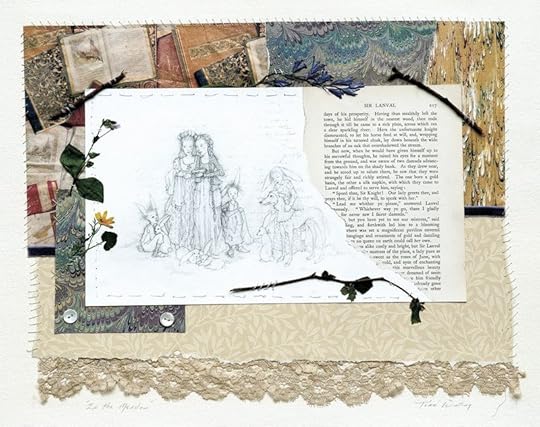

The poems tucked into the picture captions are "Caraboose" © 1999 by Delia Sherman (read the full poem here), "Donkeyskin" © by Midori Snyder © 2001, and "Once Upon a Time,' She Said" by Jane Yolen, all rights reserved. My collages above are: "Briar Rose," "Donkeyskin," and "In the Meadow." Recommended reading: "Susan Sontag on Storytelling" by Maria Popova. (Brain Pickings)

The poems tucked into the picture captions are "Caraboose" © 1999 by Delia Sherman (read the full poem here), "Donkeyskin" © by Midori Snyder © 2001, and "Once Upon a Time,' She Said" by Jane Yolen, all rights reserved. My collages above are: "Briar Rose," "Donkeyskin," and "In the Meadow." Recommended reading: "Susan Sontag on Storytelling" by Maria Popova. (Brain Pickings)

Tunes for a Monday Morning

Today, four songs from the great John Renbourn, whose music was the soundtrack of my adolescence -- introducing me and many others of my generation to the Early Music and folk ballads of the British Isles. John died last week, at aged 70, but his music will certainly live on. (There's a really lovely tribute by Peter Paphrides here.)

Raised in London and Surrey, John studied classical and medieval musical until his interest veered to folk and blues during his college years in London. While playing at Les Cousins and other Soho folk clubs, he met and teamed up with another brilliant, folk-obsessed young guitarist, Bert Jansch. Their first album together, Bert and John (1966), pioneered an Early Music and jazz inflected folk style that they called "folk baroque."

Bert and John then went on to create the hugely influential folk band Pentangle, with vocalist Jacqui McShee, bass player Danny Thompson, and drummer Terry Cox. The group's name, representing its five members, came from the device on Sir Gawain's shield in the Middle English poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.

Over the next thirty years, John founded two more bands, The John Renbourn Group and The Ship of Fools, in addition to collaborating with other musicians and touring and recording extensively on his own. He released over two dozen albums, from John Renbourn in 1965 to Live in Italy in 2006. For more information, visit the John Renbourn website.

Above, John's legendary guitar skills are evident in "Rosslyn," recorded in the early 1970s. He makes it look so easy....

Below, Pentangle performs "The House Carpenter" (a.k.a. "The Daemon Lover," Child Ballad 243) on British television in 1970. The song is introduced by Bert, with John playing citar and Bert on banjo. This mix of world music rhythms and instruments with traditional English folk material was highly unusual (and controversial) at the time, and was a very early forerunner of the mixed-tradition, mixed-genre world music bands and performers prevalent today, from Loreena McKennitt to The Imagined Village.

Above, "The Trees They Do Grown High" (audio only), from Pentangle's third album, Basket of Light (1969).

Below, in a rare recording from the 1960s, Pentangle performs the Anglo-American spiritual "Will the Circle Be Unbroken" -- a fitting song to end on, I think. Goodbye, John, and thank you for all that you gave us, and all that you've left us.

The photograph of John at the top of this post was taken in 1970; the photo at the bottom is more recent, taken by his home in a converted chapel on the Scottish borders. If you'd like a little more music from Pentangle and The John Renbourn Group this morning, go here.

March 26, 2015

From the archives: Why One Writes

"Why one writes is a question I can answer easily, having so often asked it of myself. I believe one writes because one has to create a world in which one can live. I could not live in any of the worlds offered to me — the world of my parents, the world of war, the world of politics. I had to create a world of my own, like a climate, a country, an atmosphere in which I could breathe, reign, and recreate myself when destroyed by living. That, I believe, is the reason for every work of art." - Anaïs Nin (The Diaries, Volume 5)

"Life isn’t about finding yourself. Life is about creating yourself." - George Bernard Shaw

...And so I create a world in which I can live through stories and pictures of spirited landscapes steeped in Mystery, music, and quiet acts of women's magic. I create myself every day here in the hills amid old stone walls and buttercup fields, out of scraps of paper and fragments of verse and morning coffee and dreams underfoot and books and bees and brambles and briar roses and a black dog at my side.

"A writer is dreamed and transfigured into being by spells, wishes, goldfish, sillouettes of trees, boxes of fairy tales dropped in the mud, uncles' and cousins' books, tablets and capsules and powders...and then one day you find yourself leaning here, writing on that round glass table salvaged from the Park View Pharmacy--writing this, an impossibility, a summary of who you came to be where you are now, and where, God knows, is that?" - Cynthia Ozick

Why, it's here. Where I am. Where you are. Right now.

Text first posted June 12, 2012. Caption poem, 2014. Story photographs, 2015; Tilly in the buttercup field, 2012.

Text first posted June 12, 2012. Caption poem, 2014. Story photographs, 2015; Tilly in the buttercup field, 2012.

Living by stories

"In a fractured age, when cynicism is god, here is a possible heresy: we live by stories, we also live in them. One way or another we are living the stories planted in us early or along the way, we are also living the stories we planted -- knowingly or unknowingly -- in ourselves. We live the stories that either give our lives meaning, or negate it with meaninglessness. If we change the stories we live by, quite possibly we change or lives." - Ben Okri (A Way Of Being Free)

Images above: Illustrations for J.M. Barrie's Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939).

Images above: Illustrations for J.M. Barrie's Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939).

Art, the marketplace, and narrative loss

Ever since reading Sara Maitland's lovely book Gossip From the Forest, I've been haunted by a passage in which she reflects on the ways that fairy tales have been diminished not only by the loss of the ancient wild-wood which was their natural habitat, but also by the loss of the oral storytelling tradition within our families, our communities, and our media-saturated culture.

"The whole tradition of storytelling is endangered by modern technology," she laments. "Although telling stories is a very fundamental human attribute, to the extent that psychiatry now often treats 'narrative loss' -- the inability to construct a story of one's own life -- as a loss of identity or 'personhood,' it is not natural but an art form -- you have to learn to tell stories. The well-meaning mother is constantly frustrated by the inability of her child to answer questions like 'What did you do today?' (to which the answer is usually a muttered 'nothing' -- but the 'nothing' is cover for 'I don't know how to tell a good story about it, how to impose a story shape on the events'). To tell stories, you have to hear stories and you have to have an audience to hear the stories you tell.

"Oral story telling is economically unproductive -- there is no marketable product; it is out with the laws of patents and copyright; it cannot easily be commodified; it is a skill without monetary value. And above all, it is an activity requiring leisure -- the oral tradition stands squarely against a modern work ethic....Traditional fairy stories, like all oral traditions, need the sort of time that isn't money."

Jeanette Winterson comes at the subject of "narrative loss" from another direction in her essay "Writer, Reader, Words," discussing the ways that stories shaped by the rapid rhythms of the entertainment media impact stories created for the printed page, to the diminishment of literary arts. Her stance is not an elitist one for it is abundantly clear in Winterson's work that she believes that art belongs to everybody -- but she does resist the push to view literature as simply another form of entertainment and for writers to measure their worth in sales figures, clicks, and mass popularity.

"Readers who don't like books that are not printed television, fast on thrills and feeling, soft on the brain, are not criticizing literature," she writes, "they are missing it altogether. A work of fiction, a poem, that is literature, that is art, can only be itself, can never be anything else. Nor can anything else substitute for it. The serious writer cannot be in competition for sales and attention with the bewildering range of products from the ever expanding leisure industry. She can only offer what she has ever offered: an exceptional sensibility combined with an exceptional control over words.

"How many people want that? Proportionally as few as ever but art is not for the few but for the many, and I include those who would never pick up a serious fiction or poem and who are uninterested in writing. I believe that art puts down its roots into the deepest hiding places of our nature and that its action is akin to the action of certain delving plants, comfrey for instance, whose roots can penetrate far into the subsoil and unlock nutrients that would otherwise lie out of reach of shallower bedding plants. In the haste of life and the press of action it is difficult for us to examine our feelings, to express them coherently, to express them poetically, and yet the impulse to poetry which is an impulse parallel to civilization, is a force toward that range and depth of expression. We do not want a language as a list of basic commands and exchanges, we want to handle matter far more subtle.

"When we say, 'I haven't got the words,' the lack is not in the language nor in our emotional state, it is in the breakdown between the two. The poet heals that breakdown and not only for those who read poetry. If we want a living language, a language capable of expressing all that is called upon to express in a vastly changing world, then we need men and women whose whole self is bound up in that work with words."

In our own field of mythic fiction and fantasy, I cherish the fact that the honorable craft of storytelling has been kept alive during times when realist literature too often consisted of stylistic exercises in navel gazing by and for the privileged classes (if you'll forgive that blunt assessment, and thank heavens it's changing) -- but in valuing the skill it takes to tell a good story we mustn't then run off in the opposite direction and forget the "art" in our art form altogether. Our field is wide enough to accommodate both, entertainment and literature; and wise enough, at its best, to value the strengths and forgive the weaknesses of each. But it must be noted that the economic and technological climate re-shaping the publishing industry is geared to one sort of fiction and not the other; it is not a friend of poeticism, experimentation, and the slower rhythms that art-making and art-appreciating (in fantasy or any other genre, realism included) tend to require.

Many fantasy books that cross my desk these days (sent by publishers seeking quotes or reviews *) are entertainment products, not literature; and I hasten to add that it was ever thus. Literature is rare, true art is rare, and entertainment serves a human need too. The fine craft of making artful entertainment is one that is worthy of our respect; and the line between art and entertainment has never been so firmly drawn as some critics insist. But what I find different in my reading now is a greater preponderance of novels written with the episodic structure, "beats," and dialogue of lowbrow film and television writing -- works, in other words, disconnected from the long, rich history of the literary form. Maybe I'm simply showing my age here, but I find this trend distinctly dismaying. If I want television, I'll go to television; I turn to books for what language alone does best; and even when I seek them for entertainment, then I'd like that entertainment to have at least a nodding acquaintance with the literary arts.

These days, it seems to me, not only are the "artful" novels harder to find, but also those sly, clever, wonderful books that borrow from both camps, entertainment and art; and the writers I used to count on to create them are looking increasingly hungry and harried, so busy now keeping the wolf from the door that "art" seems to be a luxury left only to those already well fed. Now, I acknowledge that it has always been difficult to make one's living writing artful"mid-list" books (i.e., books with reliable but modest sales) -- but with the mid-list shrinking everywhere, "hard" is becoming "impossible" for too many of our most interesting writers.

Should we care about this small group of writers, producing work for a small group of readers? If I, personally, don't read so-and-so, and if the market has denied so-and-so the crown of mass popularity, is it any concern of mine whether he or she can still write and still publish? My answer to both questions is a resounding yes -- because we're not just individual readers, we're members of a community; and art, and questions of art, are important to our community as a whole.

There are books that will never become best-sellers that are nonetheless vital to the health of our field: novels that expand the language of the fantastic, novels published far ahead of their time (blazing the trails that others will follow, often with a commercial success denied the early pioneers), challenging novels that demand as much from the reader as they did from the writers who made them. I propose that we should care about such writers, the Living National Treasures of our genre, if we care about fantasy literature at all. And if we do, then we must also care about the budding young artists of the next generation: the ones who aren't going to write the next Twilight and flourish on the best-sellers lists, but who just might, with right encouragement and support, create the next Alphabet of Thorn or Little, Big.

At a time when art is increasingly referred to as "content," and content is a thing we now expect to be quick, disposable, and cheap (or free), I find myself distinctly worried about those young artists...and the not-so-young artists, too. I'm worried about how they will pay for groceries, for tools, for healthcare (if they live in the U.S.), and for the precious hours and hours needed to create innovative work...and my worry here is entirely selfish, because I want to read all those books that won't exist if there's no infrastructure to support them.

I like well-crafted entertainment as much as anyone, but I need the other kind of books -- the ones that shake up my ideas, stretch my heart, and heal my wounded soul -- and if they're not being made because the makers are working at Starbucks, then my life has been diminished. All our lives have been diminished.

There are, of course, no simple answers to this, but the topic is one worth pondering, for if we depend on the marketplace for solutions, we know all too well how art will fare. My own small attempt to give art a helping hand is to seek out unfamiliar books and authors, to stretch myself beyond my usual reading comfort zone. And to stop being shy about talking about our art as an art, and about doing so with passion and conviction, in a marketplace culture more comfortable with books as products and authors as brands, with ironic detachment as protective armor against the selling out of our very souls. Every time I buy a challenging book instead of sticking to familiar "comfort reading," that's another penny in an artist's pocket....and while the value of what those books give me cannot be measured in dollars and pounds, those pennies add up and put groceries on the table. It's all I can do, but it's something, and I do it.

Had I a fairy wand to wave, I would give the artists in our field equal access to MacArthur Genius Grants and all the other grants, fellowships, residencies, and working retreats that largely bypass English-language writers working in nonrealist traditions -- or else, if segregation by genre must persist, the establishment of a similar, well-funded network of resources for artists working in nonrealist forms. Mind you, if I had a fairy wand I would first bless every child born with a love of reading.

And now I've rambled on long enough. (But hey, at least I've rambled with passion!) What are your thoughts on art-making and the marketplace, and how can might we improve the relationship between the two? Some suggested reading as part of this conversation: The Gift by Lewis Hyde (on art in a market economy) and The People's Platform by Astra Taylor (on how the arts, and other fields, have been impacted by digital technology).

* Dean and Jason, don't worry, I don't mean you! I'm loving your books and quotes are forthcoming.

* Dean and Jason, don't worry, I don't mean you! I'm loving your books and quotes are forthcoming.

March 25, 2015

Among the pines

I'm working on a long post for tomorrow, but in the meantime, this:

''To me, literature is a calling, even a kind of salvation. It connects me with an enterprise that is over two thousand years old. What do we have from the past? Art and thought. That's what lasts. That's what continues to feed people and give them an idea of something better: a better state of one's feelings, or simply the idea of a silence in one's self that allows one to think or to feel. Which to me is the same thing.''

- Susan Sontag (New York Times interview, 1992)

''Hard times are coming, when we’ll be wanting the voices of writers who can see alternatives to how we live now, can see through our fear-stricken society and its obsessive technologies to other ways of being, and even imagine real grounds for hope. We’ll need writers who can remember freedom -- poets, visionaries -- realists of a larger reality.''

- Ursula K. Le Guin (National Book Award acceptance speech, Nov. 2014)

March 23, 2015

Signs of spring

Flowers in the courtyard.

Primroses in the garden.

Tadpoles in the frog pond.

Ponies in the field.

Wild daffodils emerging in the woods.

Tilly in the sunshine on the studio bench...

...and words filling up my notebooks again.

The long winter is over. The sap is rising, and it's time, once more, for creativity to flow.

"And the day came when the risk to remain tight in a bud was more painful than the risk it took to blossom." - Anaïs Nin (The Diaries)

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers