Terri Windling's Blog, page 142

March 22, 2015

Tunes for a Sunday Morning

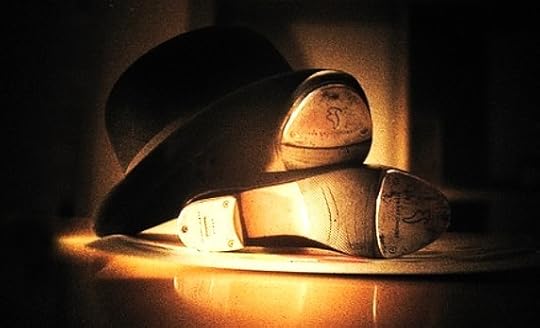

This week's tunes are going up a day early in honor of my music-loving, tap-dancing husband's birthday: foot-taping tunes from France, Germany, England, Greece, and America. ♥

Above, the fabulous French electro-swing band Caravan Palace perform "Rock It For Me" live at Le Trianon in Paris.

Below, "St. James Ballroom" by Alice Francis and her band. Francis comes from Timisoara, Romania and now lives in Cologne, Germany.

Above, "When I Get Low, I Get High," the old Chick Webb/Ella Fitzgerald standard, performed by The Speakeasy Three, a vocal trio from Brighton, England. They are backed up here by The Swing Ninjas, also from Brighton.

Below, Cissie Redgwick, from Yorkshire, England, updates the classic "Gimme That Swing."

Let's add zombies and magic to the mix:

Above, "Black Swamp Village" by The Speakeasies Swing Band from Thessaloniki, Greece.

Below, "Tightrope" by the American soul/rhythm and blues singer Janelle Monáe. She was born in Kansas City, studied in New York and Philadelphia, and now lives in Atlanta.

Oh heck, one more:

"Valentine" by Electric Swing Circus, an adorable young electro-swing/breakbeat/house/dubstep/circus arts band, from Birmingham, England.

I hope this kicks off your week with a smile. If you'd like a little more, try "Bright Lights Late Nights" by the Speakeasy Swing Band (Greece), "That Man" by the great swing and jazz singer Caro Emerald (The Netherlands), and "Suzy" by Caravan Palace (France).

March 20, 2015

The stories that take root

This seems to have become Jeanette Winterson Week on Myth & Moor. (For various reasons, her incisive essays have been much on my mind lately.) So let's end the week with a misty moorland hillside and a passage taken from "Testimony Against Gertrude Stein":

"We mostly understand ourselves through an endless series of stories told to ourselves by ourselves and others. The so-called facts of our individual words are highly colored and arbitrary, facts that fit whatever fiction we have chosen to believe in. It is necessary to have a story, an alibi that gets us through the day, but what happens when the story becomes scripture? When we can no longer recognize anything outside our own reality?

"We have to be careful not to live in a state of constant self-censorship, where whatever conflicts with our world view is dismissed or diluted until it ceases to be a bother. Struggling against the limitations we place on our minds is our own imaginative capacity, a recognition of an inner life often at odds with the internal figurings we spend so much energy supporting.

"When we let ourselves respond to poetry, to music, to pictures, we are clearing out a space where new stories can root, in effect we are clearing a space for new stories about ourselves."

The passage just quoted nails, for me, precisely why we need art in our lives and not just the familiar, repetitive stories of mass entertainment, enjoyable as they may be. Entertainment amuses, distracts, and consoles us, and that has its use and it has its value, but it's not the same use or value of art. Art enlarges us. Transforms us. Heals what is broken inside us. Deepens our understanding of ourselves, each other, and the world around us.

"Art is central to all our lives, not just the better-off and educated, " Winterson once said in an interview. "I know that from my own story, and from the evidence of every child ever born -- they all want to hear and to tell stories, to sing, to make music, to act out little dramas, to paint pictures, to make sculptures. This is born in and we breed it out. And then, when we have bred it out, we say that art is elitist, and at the same time we either fetishize art -- the high prices, the jargon, the inaccessibility -- or we ignore it. The truth is, artist or not, we are all born on the creative continuum, and that is a heritage and a birthright of all of our lives."

March 18, 2015

Life, art, and surrender

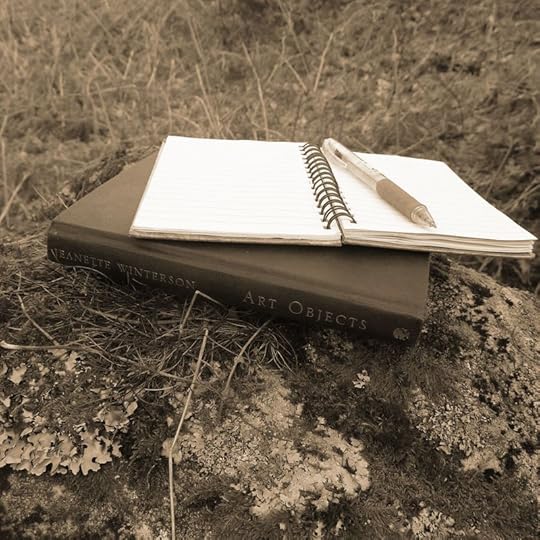

If I had to chose a single quote to encapsulate my view of life and art, this line from Jeanette Winterson's 1995 essay "Art Objects" would be a strong contender:

"I had better come clean now and say that I do not believe that art (all art) and beauty are ever separate, nor do I believe that either art or beauty are optional in a sane society."

Yes. That's it exactly.

"That puts me on the side of what Harold Bloom calls 'the ecstasy of the privileged moment,' " Winterson continues. "Art, all art, as insight, as transformation, as joy. Unlike Harold Bloom, I really believe that human beings can be taught to love what they do not love already and that the privileged moment exists for all of us, if we let it. Letting art is the paradox of active surrender. I have to work for art if I want art to work on me."

Later in this luminous essay she writes: "We know that the universe is infinite, expanding and strangely complete, that it lacks nothing we need, but in spite of that knowledge, the tragic paradigm of human life is lack, loss, finality, a primitive doomsaying that has not been repealed by technology or medical science. The arts stand in the way of this doomsaying. Art objects. The nouns become an active force not a collector's item. Art objects.

"The cave wall paintings at Lascaux, the Sistine Chapel ceiling, the huge truth of a Picasso, the quieter truth of Vanessa Bell, are part of the art that objects to the lie against life, against the spirit, that is pointless and mean. The message colored through time is not lack, but abundance. Not silence but many voices. Art, all art, is the communication cord that cannot be snapped by indifference or disaster. Against the daily death it does not die."

"Naked I came into the world, but brush strokes cover me, language raises me, music rhythms me. Art is my rod and my staff, my resting place and shield, and not mine only, for art leaves nobody out. Even those from whom art has been stolen away by tyranny, by poverty, begin to make it again. If the arts did not exist, at every moment, someone would begin to create them, in song, out of dust and mud, and although the artifacts might be destroyed, the energy that creates them is not destroyed. If, in the comfortable West, we have chosen to treat such energies with scepticism and contempt, then so much the worse for us.

"Art is not a little bit of evolution that late-twentieth-century city dwellers can safely do without. Strictly, art does not belong to our evolutionary pattern at all. It has no biological necessity. Time taken up with it was time lost to hunting, gathering, mating, exploring, building, surviving, thriving. Odd then, that when routine physical threats to ourselves and our kind are no longer a reality, we say we have no time for art.

"If we say that art, all art is no longer relevant to our lives, then we might at least risk the question 'What has happened to our lives?' "

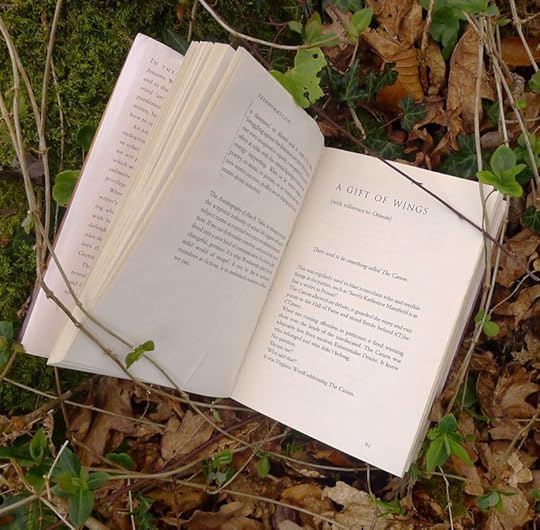

The magic of words

In her essay "A Gift of Dreams," Jeanette Winterson gets to the core of what makes Virginia Woolf's work so compelling, and in doing so she evokes the magic inherent in the arts of writing and reading themselves.

"Unlike many novelists, then and now, she loved words," notes Winterson. "That is she was devoted to words, faithful to words, romantically attached to words, desirous of words. She was territory and words occupied her. She was night-time and words were the dream.

"The dream quality, which is a poetic quality, is not vague. For the common man it is the dream, if at all, that binds together in a new rationale, disparate elements. The job of the poet is to let the binding happen in daylight, to happen to the conscious mind, to delight and disturb the reader when the habitual pieces are put together in a new way.

"Above all, credulity is not strained. We should not come out of a book as we do from a dream, shaking our heads and rubbing our eyes and saying, 'It didn't really happen.' In poetry, in drama, in opera, in painting, in the best fiction, it really does happen, and is happening all the time, this other place where, as strong and compelling as our own daily world, as believable, and yet with a very strangeness that prompts us to recall that there are more things in heaven and earth and that those things are solider than dreams.

"They may prove solider than real life, as we fondly call the jumble of accidents, characters and indecisions that collect around us without our noticing. The novelist notices, tries to make us clearer to ourselves, tries to set the liquid day, and because of this we read novels. We do hope to see ourselves, as much out of vanity as for instruction. Nothing wrong with that but there is further to go and it is this further than only poetry can take us. Like the novelist, the poet notices, focuses, sharpens, but for the poet that is the beginning. The poet will not be satisfied with recording, the poet will have to transform. It is language, magic wand, cast of spells, that makes transformation possible."

The poet does this, yes, and the poetic fiction writer, and especially, I believe, the poets and fiction writers working in the field of Mythic Arts. Casting spells with language and telling tales of transformation are, after all, the very point of this alchemical genre in which elements of poetry, prose, myth, fairy tale, and dream are carefully combined, turning lead, and straw, and language, and life itself into pure gold.

As Ursula Le Guin said in her essay "From Elfland to Poughkeepsie" (in a passage I quote often, because it's just so true):

"Fantasy is a different approach to reality, an alternative technique for apprehending and coping with existence. It is not antirational, but pararational; not realistic but surrealistic, a heightening of reality. In Freud's terminology, it employs primary, not secondary process thinking. It employs archetypes, which, as Jung warned us, are dangerous things. Fantasy is nearer to poetry, to mysticism, and to insanity than naturalistic fiction is. It is a wilderness, and those who go there should not feel too safe. And their guides, the writers of fantasy, should take their responsibilities seriously....A fantasy is a journey. It is a journey into the subconscious mind, just as psychoanalysis is. Like pyschoanalysis, it can be dangerous; and it will change you."

Powerful word magic indeed.

Returning to the essay "A Gift of Wings," Winterson describes Virginia Woolf as a writer who "is not afraid of beauty. She is as sensitive to the natural world as any poet and as physical in response as any lover. She is not afraid of pain. The dark places attract her as well as the light and she has the wisdom to know that not all dark places need light. She has the cardinal virtue of critical courage, sifting her ideas and impressions through a fine riddle of words...."

That, I believe, is what we, too, must strive for. The love of words shared by all good writers and all good readers is the magic that will show us how.

Winterson's essay can be found in her collection Art Objects (1995), Le Guin's in her collection The Language of the Night (1979). And speaking of the magic of language, I highly recommend Lisa Stock's photography series "The Nourishment of Words." It's simply delightful.

Winterson's essay can be found in her collection Art Objects (1995), Le Guin's in her collection The Language of the Night (1979). And speaking of the magic of language, I highly recommend Lisa Stock's photography series "The Nourishment of Words." It's simply delightful.

March 16, 2015

"Into the Woods" series, 37: Elemental Magic

In his famous "Doctrine of the Four Elements," the Greek philosopher Empedocles (5th century BC) divided the world into four elements associated with four divinities: earth (Hera), air (Zeus), fire (Hades), and water (Persephone). These four elemental "roots," wrote Empedocles, comprised not only the physical substance of all matter, but also the spiritual essences that quickened and animated all life forms. The universe, he explained, was comprised of two forces, Love and Strife, which wax and wane in strength. When Love was the dominant force, the four elements were balanced in a Sphere of Unity; but as Strife became dominant, the sphere was broken and the elements were scattered. The single immortal soul of Love was then divided into many, many souls (each containing some measure of Love and Strife), born and reborn into mortal bodies formed from the four elements. Though Strife remains dominant in the world, eventually its power, too, will wane, and Love will be on the rise once again. The elemental sphere will be restored, and the divided souls will meld back into One.

Aristotle later expanded on Empedocles' ideas in his influential Metaphysics. He wrote that all matter and all men are influenced by the qualities of the four elements: earth (dry and cold), air (wet and hot), fire (dry and hot), and water (wet and cold). Warmth and coolness, said Aristotle, are the most powerful of these qualities, making fire (whose primary power is warmth) and water (whose primary power is coolness) the most active and important of the elements. But because these two are opposites, they require the mediating qualities of a  third element (earth or air) in order to unite their properties. The mediating element is called the Harmonia (named after the daughter of Aphrodite and Ares), capable of binding opposites together in order to restore unity and health, to engender transformation, and to enable acts of magic.

third element (earth or air) in order to unite their properties. The mediating element is called the Harmonia (named after the daughter of Aphrodite and Ares), capable of binding opposites together in order to restore unity and health, to engender transformation, and to enable acts of magic.

One ancient way to create such a union was in the Pyria, the Greek equivalent of a Native American sweatlodge -- bringing earth, air, fire, and water together in a ceremonial setting. The Pyria, like a sweatlodge, was made of blankets stretched over a wooden frame. Stones (earth) are heated (fire), then placed in a cauldron inside the Pyria, where water is poured over them, forming steam representing the union of all four elements. As John Opsopaus writes (in Bibliotheca Arcana), the steam "is the (Hot, Wet) Air that unites the opposites. This all takes place in contact with, or even within, the (Cool, Dry) Earth." In Native American sweatlodge ceremonies, the elements of earth, air, fire, and water are also united in the service of prayer, purification, and spiritual transformation. The exact form of the ceremony varies from tribe to tribe, but it is generally common for the activating spirits of the four elements to be respectfully addressed as living beings and honored for their crucial role in sustaining life upon the earth. The hiss of the water on hot stones, sending steam to fill up the dark of the lodge, is said to represent a child's very first breath -- air, earth, water, and fire united as new life begins. The Lakota word for the sweatlodge ceremony, inipi, literally means "to breathe."

The ancient Celts divided the world into three sacred elements, with earth, water, and air as the swirling spirals of the tri-part triskele symbol. The Norse had four primary elements: fire, ice, wind, and wave, to which (some believe) they added four secondary elements: iron, salt, yeast, and venom -- with a ninth element, earth, formed from a combination of all the others. The classic Tarot deck is based on a system  of four, with Coins representing earth, Cups representing water, Swords representing air, and Wands representing fire. The Chinese recognize five basic elements: earth, water, fire, wood, and metal, as does Achaemenid Zoroastrianism in Arabic lands: earth, water, fire, plants, and metal. The Indian Chandogya Upanishad names just three elements: earth, water, and fire.

of four, with Coins representing earth, Cups representing water, Swords representing air, and Wands representing fire. The Chinese recognize five basic elements: earth, water, fire, wood, and metal, as does Achaemenid Zoroastrianism in Arabic lands: earth, water, fire, plants, and metal. The Indian Chandogya Upanishad names just three elements: earth, water, and fire.

In alchemy, the union of fire (masculine) and water (feminine) is one the primary tasks of the art, made possible through the mediating elements of air and earth. Though alchemy is often perceived now only as a crackpot pseudo-science through which men sought to turn lead into gold, mythic scholar Mircea Eliade pointed out (in The Curcible and the Forge) that alchemy as it was practiced long ago was as much a philosophy as a science. Alchemy, according to Eliades, arose from the early Mystery rites of the ancient Craft Guilds of metallurgists and smiths -- which, in many cultures, had initiatory practices similar to those of shamans or wizards. For alchemists through the centuries, transmuting "lead" into "gold" was not a literal but a spiritual process, akin to seeking enlightenment. Alchemical experiments in the laboratory were, on the one hand, an early form of the secular science of chemistry -- but they also had a distinctly sacred aspect, drawing upon Aristotelian, Chinese and other ideas about the sacred qualities of the elements. Alchemists sought to bring the elements together into perfect states of unity as a means of sustaining health, longevity, and spiritual growth.

"I had discovered, early in my researches," wrote William Butler Yeats (in Rosa Alchema, 1913), "that their doctrine was no mere chemical fantasy, but a philosophy they applied to the world, to the elements, and to man himself."

Many other systems of magical belief were also rooted in the four elements. Wizard, witches, and enchanters of all stripes called upon the power of fire (associated with passion), water (the emotions), earth (the body), and air (the mind and imagination), or sought to communicate with magical spirits linked to each element.

Earth elementals included those who lived in caves, barrows and deep underground, and who often had a special facility for working with precious metals. Such creatures appeared in myths and legends worldwide,  including the Coblynau in the hills of Wales, the web-footed Couril guarding the standing stones of Brittany, the various metal-working dwarves of Old Norse legends, the Maanväki of Finland, the Thrussers of Norway, the Karzalek of Poland, the Erdluitle of northern Italy, the Illes of Iceland, the Gandharvas of India, and the Gans of the Apache tribe in the American South-west. Forest fairies of all shapes and sizes were also associated with the element of earth, such as the shy Aziza in the woodlands of West Africa, the Mu of Papua New Guinea, the Shinseen of China, the Kulaks of Burma, the Hantu Hutan of the Malay Peninsula, the Bela of Indonesia, the Patu-Paiarehe of the Maori in New Zealand, the Oakmen of the British Isles, the Silvanni of in woodlands of Italy, the Skogsra (forest spirits) of Sweden, the Ulda of Sámi tales, and the Manitou of the Algonquin tribe in the forests of Canada.

including the Coblynau in the hills of Wales, the web-footed Couril guarding the standing stones of Brittany, the various metal-working dwarves of Old Norse legends, the Maanväki of Finland, the Thrussers of Norway, the Karzalek of Poland, the Erdluitle of northern Italy, the Illes of Iceland, the Gandharvas of India, and the Gans of the Apache tribe in the American South-west. Forest fairies of all shapes and sizes were also associated with the element of earth, such as the shy Aziza in the woodlands of West Africa, the Mu of Papua New Guinea, the Shinseen of China, the Kulaks of Burma, the Hantu Hutan of the Malay Peninsula, the Bela of Indonesia, the Patu-Paiarehe of the Maori in New Zealand, the Oakmen of the British Isles, the Silvanni of in woodlands of Italy, the Skogsra (forest spirits) of Sweden, the Ulda of Sámi tales, and the Manitou of the Algonquin tribe in the forests of Canada.

Air elementals included all manner of winged fairies, sprites, spirits, and sylphs, such as the luminous Soulth of Irish lore, the Star Folk of the Algonquin tribe, the Atua of Polynesia, and the Peri of Persia (said to dine exclusively on perfume and other delicate scents). Creatures who accounted for weather phenomena (mistral winds, whirlwinds, storms, etc.) were also associated with the air element, including the Spriggans of Cornwall, the Vily of Slavonia, the Vintoasele of Serbia and Crotia, and the Rusali of Romania.

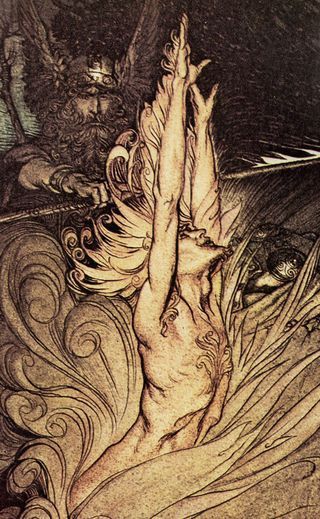

Water elementals were divided between those of the sea and those of fresh water. Salt water elementals included mermaids and mermen, seal people, and sirens of various kinds: the Selchies (Selkies) of western Europe, the Daoine Mara and Fin Folk of Scotland, the Merrows of Ireland, the Nereides of Greece, the Havfreui of Scandinavia, the Mal-de-Mer of Brittany, and Groac’h Vor, a Breton mermaid. Fresh water elementals lived in rivers, lakes, pools, fountains, bogs and marshes, and anywhere else that water was found. These included the nixies and kelpies of English rivers, the Dracs who haunted the rivers of France, the Rhinemaidens of Germany, the  Kludde of Belgium, the Laminak of the Basque region, the Hotots of Armenia, the Judi of Macedonia, the Cacce-Halde of Lapland, the sweet-voiced Nakk of Estonia, and the bashful Nokke who appeared only at dusk and dawn in Sweden.

Kludde of Belgium, the Laminak of the Basque region, the Hotots of Armenia, the Judi of Macedonia, the Cacce-Halde of Lapland, the sweet-voiced Nakk of Estonia, and the bashful Nokke who appeared only at dusk and dawn in Sweden.

The most common type of fire elemental was the salamander, much prized as a spirit-helper by witches, wizards, and alchemists even though they were tricky, quick-tempered creatures, often appearing as blazing sparks of light by those who sought their aid. Also aligned to the fire element were treacherous Djinn of Persian lore, the seductive Muzayyara in Egyptian tales, the Akamu of Japan, and the Drakes or Drachen of western Europe (who resembled streaking balls of fire and smell like rotten eggs). Luminous will-o'-the-wisp type fairies were also classified as fire spirits -- such as the Ellylldan of Welsh marshland, the Teine Sith of the Scottish Hebrides, the Spunkies of southwest England, the Faeu Boulanger of the Channel Islands, the Candelas of Sardinia, and the Fouchi Fatui who haunted marshes, ponds, and cemetaries in northern Italy. The various fairies, brownies, and trolls who guarded hearth fires (the Dĕduška of Russia, the Gabija of Lithuania, the Natrou-Monsieur of France, etc.) could be either malign or beneficent, depending on their country of origin and the circumstances under which they were encountered, but most other fire elementals were exceedingly dangerous and best left alone.

Earth, air, fire, and water: these four elements, in the Western tradition, are the foundation of natural magic, alchemy, philosphophy, modern science, and life itself. "Life is the fire that burns and the sun that gives light," said the Roman philosopher Seneca the Younger. "Life is the wind and the rain and the thunder in the sky. Life is matter and is earth, what is and what is not, and what beyond is in Eternity."

Likewise, an old Navajo prayer honors the elements and our connection to all things formed of them: "The mountains, I become a part of them. The herbs, the flowers, the trees, I become a part of them. The morning mists, the clouds, the gathering waters, I become a part of them. The thunder, the flash of lightning, the sacred fire, I become a part of them. The wind, the cedar smoke, the living breath, I become a part of them. As I rise in the morning, I am part of them. As I pray in the morning, I am part of them. In beauty, I am part of them. In this way, I am part of them. "

Further Reading

Nonfiction (online): Heinz Insu Fenkl examines fire myths in "Fire and the Fire Bringer" and discusses the mythic/linguistic history of "Men and Mud" (Journal of Mythic Arts); I explore water myths in "Water, Wild and Sacred" (Myth & Moor); and David Abram meditates on air in "The Air Aware" (Orion Magazine).

Fiction (print): I highly recommend the "Elemental Logic" series by Laurie J. Marks, which is deeply steeped in elemental magic and folklore. The first three books of the series -- Fire Logic, Earth Logic, and Water Logic -- are now available in beautiful editions from Small Beer Press. (The fourth book, Air Logic, is forthcoming, but each book stands perfectly well on its own.) Marks is writing "imaginary world" fantasy better than just about anyone else these days, inviting comparisons with Ursula Le Guin, Elizabeth Lynn, and C.J. Cherryh for the depth and complexity of her work.

Water and Fire, the first two books in the on-going 'Tales of Elemental Spirits" series by the husband-and-wife team of Peter Dickinson and Robin McKinley, contain delicious short stories by two of the best writers in the fantasy field. A.S. Byatt's Elementals: Stories of Fire and Ice is also enchanting, although the link between the stories and the collection's title is a little less direct. For children, Earth, Fire, Water, Air by Mary Hoffman is a truly splendid gathering of world-wide myths, folktales, poems and musings on the elements and our connection to nature, with lovely illustratons by Jane Ray.

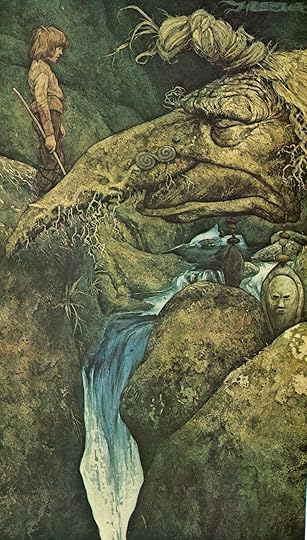

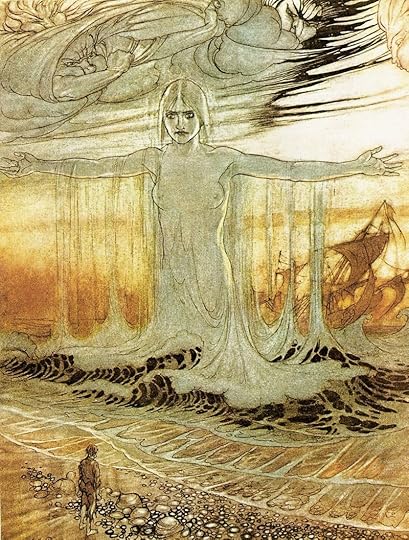

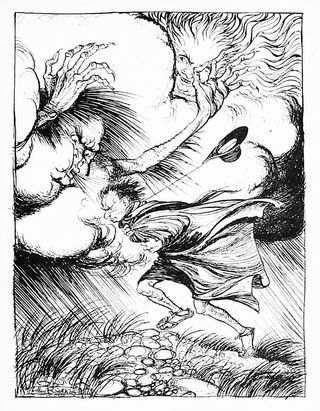

Art above: "The River Teign" by Brian Froud. "The Shipwrecked Man, the Wind, and the Sea" and"The North Wind and the Sun" by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939). "Dreaming" by Brian Froud. The Neolithic triple spiral (triskele) symbol. "The Alchemist" by Edmund Dulac (1882-1953). "Mime Makes a Sword for Sigfried," "Twilight Dreams," "The Rhinemaidens," and "Appear Flickering Fire" by Arthur Rackham. "Will'o the Wisps" by Brian Froud. "Undine" by Arthur Rackham. "Trolls" by John Bauer (1882-1918). The cover art for Fire Logic and Earth Logic is by Kathleen Jennings.

Art above: "The River Teign" by Brian Froud. "The Shipwrecked Man, the Wind, and the Sea" and"The North Wind and the Sun" by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939). "Dreaming" by Brian Froud. The Neolithic triple spiral (triskele) symbol. "The Alchemist" by Edmund Dulac (1882-1953). "Mime Makes a Sword for Sigfried," "Twilight Dreams," "The Rhinemaidens," and "Appear Flickering Fire" by Arthur Rackham. "Will'o the Wisps" by Brian Froud. "Undine" by Arthur Rackham. "Trolls" by John Bauer (1882-1918). The cover art for Fire Logic and Earth Logic is by Kathleen Jennings.

March 9, 2015

The week ahead

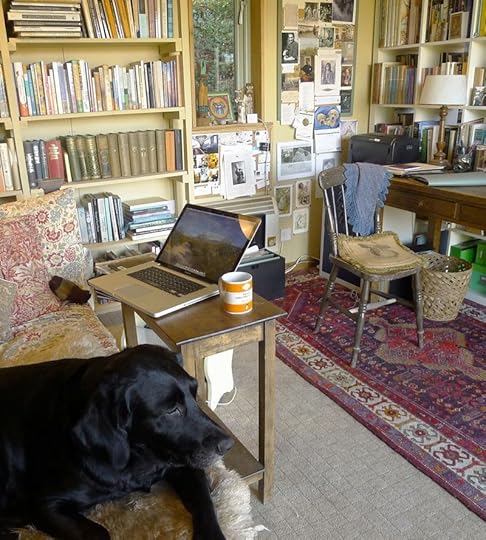

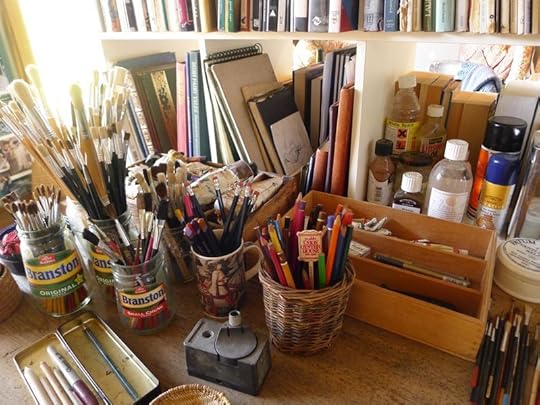

This is an "off line" week for me -- which is something I do periodically in order to keep my digital life in balance with the tactile life of earth underfoot, sky above, and the natural world around us. I'll be diving into a new creative project this week, immersing myself and finding its particular rhythms without interruptions or Internet distractions. Tilly and I will be back on Myth & Moor on Monday, March 16 (and I'll respond to comments left here then).

In the meantime, some reading recommendations:

* "In the Memory Ward" by Adam Gopnik, about Britain's most eccentric library (The New Yorker)

* "Frames of Reference," a good piece on the writing craft by John McPhee (The New Yorker)

* More writing advice: "Writing Women Characters as Human Beings" by Kate Elliot (Tor.com)

* "Thorns in My Throat: Writing Through the Scars," a moving essay by Shveta Thakrar (The Toast)

* "Don't Judge a Book by its Author," a smart, provocative article on book/author labels and "authenticity" by Aminatta Forna (The Guardian)

* "The History of 'Loving' to Read" by Joshua Rothman, a reflection on Deidre Shauna Lynch's Loving Literature: A Cultural History (The New Yorker)

* "Thoughts upon watching people shout people down," on modes of reading and Internet controversy by Elizabeth Knox (Knoxon, via Ellen Kushner)

* "On Not Going Home" by James Wood, a beautiful essay on states of exile in life and literature (The London Review of Books)

* Another take on the subject: "Where is Home?" by Ruth Behar (Aeon Magazine)

* "Rapt: Grieving With Your Goshawk," Kathryn Schulz's review of H is for Hawk by Helen Macdonald (The New Yorker)

* "A Primer on My Favorite Short Story Writer" by A.N. Devers, a short but impassioned piece on the fiction of Kelly Link (Longreads)

* "The Joyful, Gossipy and Absurd Private Life of Virginia Woolf" by Emma Woolf, the author's great-niece (Newsweek)

* "Down and Dirty Fairy Tales," an interview with fairy tale scholar Maria Tatar (Salon)

* "The Reindeer Riders," photographs of the nomadic tribes of Outer Mongolia by photographer and scholar Hamid Sardar-Afkhami (Messynessy Chic)

If you're anywhere near the South West of England, don't forget that Chagword (the Dartmoor literary festival held here in Chagford) is coming up this weekend. There will be book talks and other events for adult, teenage, and young readers -- including Philip Marsden's talk on Rising Ground: The Spirit of Place, and a session with author Geraldine McCaughrean and artist David Wyatt on the creation of Peter Pan in Scarlet. There are still tickets left, but they're going fast!

And speaking of David, he's having a studio clear-out sale of paintings in his Etsy shop right now.

I also want to put in a word for my good friend (and Chagford neighbor) Gary Burdis, creator of Potentials, a one-on-one Life Coaching service. He is open for new clients at the moment -- and I can say from personal experience that his work in this field is extraordinary. Although he's coached a wide range of clients, he's especially good at working with creative people and engaging with issues involving the creative process (goal-setting, creative blocks, etc.). You don't have to live here in Devon for he also does counseling and coaching by Skype, and I recommend him very, very highly.

Have a good week, everyone, and I'll see you again next Monday.

Signs that spring is coming

There are snowdrops in the woods...

...crocus in the church yard...

...and primroses appearing all around the village.

Ponies are drifting down from the moor to birth their foals in the shelter of the Commons.

Lord have mercy, it's been a long winter. And if some of us, battered by its storms, are moving a little slowly now, I think sometimes we need to give ourselves more credit for the fact that we're still moving. Even when creative work is not quite flowing, we show up at our desks each day and push it forward bit by bit, page by page, brush stroke by brush stroke. We haven't give up. We're still on the path....

And the path, sweet Tilly, is everything. So keep on going. I'm right behind you.

March 6, 2015

Friday morning here in Devon

Alas, no Myth & Moor post today, as we've got vet & doctor appointments this morning to make sure everyone at Bumblehill, four-footed and two-footed, is properly on the mend. Comments and poems welcome nonetheless, if this charming picture by Arthur Rackham inspires you to do so.

And here's a poem to share with you: "Fairy-tale Logic" by A.E. Stallings.

March 4, 2015

An ode to animals

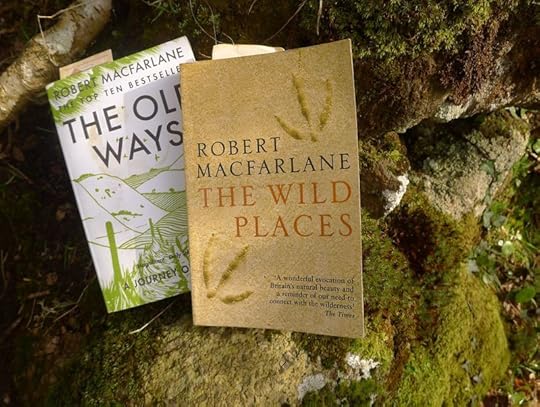

A snow hare encounter from The Wild Places by Robert Macfarlane:

"We began to move steeply uphill, over boggy ground, slipping on bracken and grass. Our clothes, already wet with rain, became slicked with mud. We neared the rocks. Then -- Hares! Hares! Two shouts from John, and two hares breaking cover in the rocks above us, ghosts slipping from the rocks, over the bilberry and heather. Five seconds and they were gone, leaving my heart thumping.

"We walked up into the heart of the tors, alert for more hares. The tors were spread over the rim of the plateau, and they faced twenty clear miles of high moor. At that height, the wind was colossal, hurtling out of the black west, and of such strength that it was impossible to stand straight in it... Looking for cover, we walked up and over a shoulder of the moor, and there, suddenly, were more hares, dozens of them, white against the dark moor, moving in haphazard darts, zizagging and following unpredictable deviations, like particles in a cloud chamber. They must, like us, have been driven away from the rocks by the wind, and come here to the peat-troughs for shelter. Their white fur drew the very last of the light, so that they glowed against the dark moor. One, a big male, still dabbed there and there with brown fur, stopped, glanced back at us over his shoulder, and then spun away into the dark.

"So few wild creatures, relatively, remain in Britain and Ireland: so few, relatively, in the world. Pursuing our project of civilisation, we have pushed thousands toward the brink of disappearance, and many more thousands over that edge. The loss, after it is theirs, is ours. Wild animals, like wild places, are invaluable to us precisely because they are not us. They are uncompromisingly different. The paths they follow, the impulses that guide them, are of other orders. The seal's holding gaze, before it flukes to push another tunnel through the sea, the hare's run, the hawk's high gyres: such things are wild. Seeing them, you are made briefly aware of a world at work around and beside our own, a world operating in patterns and purposes that you do not share. These are creatures, you realise, that live by voices inaudible to you.''

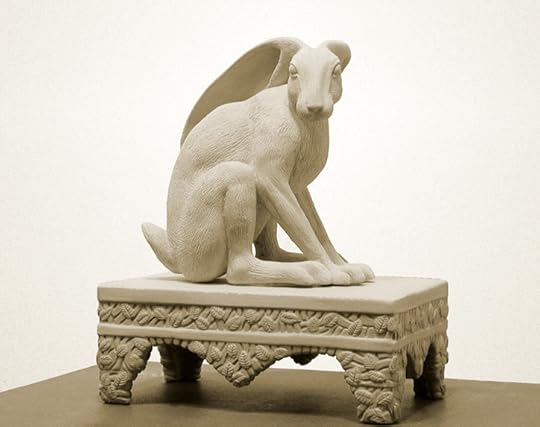

The art in this post is by one of my favorite contemporary sculptors, Tricia Cline, a self-taught artist from northern California who works primarily in porcelain. The top piece here comes from her "Animal Gods" series, and the rest from "The Exiles from Lower Utopia" series.

"This body of work," she says, "is an ode to the Animal, its ability to perceive, and our return to that perception. An animal is its very form. Its function is its form. A dog runs at full speed, a distinct scent or sound alters its direction. The legs, the nose, the ears of the dog are its function, its bliss. When an animal recognizes another animal it reads with an instinctual eye the character in the form -- the essential nature in the form before it. Its text is not a concept about what it’s looking at but a full-bodied response to the shape, smell, movement, and stance of the image in front of it. The language of animals is the language of images. An image is not an idea with a defined meaning, it is itself an animal.

"This is the ode -- to reconnect with our own animal perception is to clarify and heighten our perception of who and what we are in the moment … to go beyond the limited mental concepts of who we think we are ... to an awareness of oneself that is infinitely more vast. The Exiles migrate between the human world and the animal world and carry this awareness on their backs. They are the silent embodiment of this Quest. They understand the language of animals and are self-appointed ambassadors from that world. They are firmly seated, in the language of animals, the language of imagery. They have succeeded by virtue of being."

Visit her website to see more of her work, which is mythic, magical, and thoroughly astonishing.

See the picture captions (by running your cursor over the images) for individual titles of Tricia Cline's sculptures, each one of them conjuring stories and the myths of a forgotten world.

March 3, 2015

True places

Another aspect of the "spirit of place," this time from The Wild Places by Robert Macfarlane:

"In so many of the landscapes I reached on my journeys, I had found testimonies to the affection they inspired. Poems tacked up on the walls of bothies; benches set on lakesides, cliff-tops or low hill passes, commemorating the favourite viewpoint of someone now dead; a graffito cut into the bark of an oak. Once, stopping to drink from a pool near a Cumbrian waterfall, I had seen a brass plaque set directly beneath a rock: 'In memory of George Walker, who so loved this place.' I loved that 'so.'

"These were the markers, I realised, of a process that was continually at work throughout these islands, and presumably throughout the world: the drawing of happiness from landscapes both large and small. Happiness, and the emotions that go by the collective noun of 'happiness': hope, joy, wonder, grace, tranquility and others. Every day, millions of people found themselves deepened and dignified by their encounters with particular places.

"Most of these places, however, were not marked as special on any map. But they became special by personal acquaintance. A bend in a river, a junction of four fields, a climbing tree, a stretch of old hedgerow or a fragment of woodland glimpsed from a road regularly driven along -- these might be enough. Or fleeting experiences, transitory, but still site-specific: a sparrowhawk sculling low over a garden or street, or the fall of evening light on a stone, or a pigeon feather caught on a strand of spider's silk and twirling in mid-air like a magic trick. Daily, people were brought to sudden states of awe by encounters such as these: encounters whose power to move us was beyond expression but also beyond denial. I remember what Ishmael had said in Moby-Dick about the island of Kokovoko: 'It is not down in any map. True places never are.'

"Little is said publicly about these encounters. This is partly because it is hard to put language to such experiences. And partly, I guess, because those who experience them feel no strong need to broadcast their feelings. A word might be exchanged with a friend, a photograph might be kept, a note made in a journal, a line added to a letter. Many encounters would not even attain this degree of voice. They would stay unarticulated, part of private thought. They would return to people as memories, recalled while standing on a station platform packed tightly as a football crowd, or lying in bed in a city, unable to sleep, while headlights of passing cars pan around the room.

"It seemed to me that these nameless places might be in fact more important than the grander wild lands that for so many years had gripped my imagination. Taken together, the little places would make a map that could never be drawn by anyone, but which nevertheless existed in the experience of countless people. I began to make a list in my head of what would be on my own map of private or small scale wild places."

I, too, have an internal map of "true places," including many of the small-scale wild places that I share in the photographs on this blog...as well as one or two special spots, I admit, that I keep just for myself.

And you? What are some of your "true places"? Are they spots you re-visit in daily life...or memories of places and moments past that retain a talismanic potency?

Comments, poems, stories, links to photos or artworks, or any other way that you might care to answer these questions are welcome.

While we're speaking of Robert Macfarlane, if you haven't yet read his article "The World-hoard: ReWilding Our Language of Landscape," published in The Guardian last week, I highly recommend it. It's based on his new boom, Landmarks, which sounds intriguing indeed. If you're in London on March 13th, you can hear Macfarlane talk about it here.

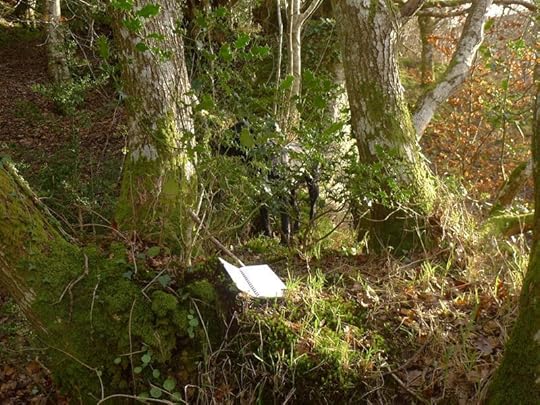

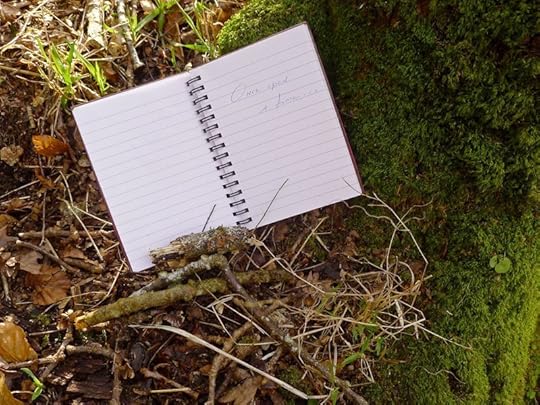

Photographs above: Trees growing on top of the old boundary wall at the edge of the woods, so covered in vegetation that you can barely see the stone wall beneath. The top of the wall is just wide enough to form a little woodland pathway for the Hound, and a nesting place to read, write, or dream for me. The winter woods surrounding us are green with holly, lichen, and moss, lit by an early morning light as thick and sweet as golden syrup.

Photographs above: Trees growing on top of the old boundary wall at the edge of the woods, so covered in vegetation that you can barely see the stone wall beneath. The top of the wall is just wide enough to form a little woodland pathway for the Hound, and a nesting place to read, write, or dream for me. The winter woods surrounding us are green with holly, lichen, and moss, lit by an early morning light as thick and sweet as golden syrup.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers