Terri Windling's Blog, page 144

February 19, 2015

The sun has returned...

...for the moment, at least...and the Hound is back in her hills again. Perched on her rock, she reads news in the wind with the twitch of her nose and the cocking of her ears. I sit close by, my skirt tucked beneath me, a book of poems in my lap, coffee in a tin cup. Today's poem, Tilly, is this one. Hush now, stay close, and listen.

Another rainy day in the studio...

...and the Hound lies disconsolate, for she was hoping for a long walk in the hills. Don't worry, Tilly, the rain will stop and walks will come. In the meantime, let me read you a poem -- about love and loss (as we've been talking about this week), and the wild world. And the falling of the rain.

February 18, 2015

Bowing to the birds

Today, an especially beautiful passage from Arctic Dreams by Barry Lopez describing tundra life in the western Brooks Range of Alaska:

"On the evening I am thinking about -- it was breezy there on the Ilingnorak Ridge, and cold; but the late-night sun, small as a kite in the northern sky, poured forth an energy that burned against my cheekbones -- it was on that evening that I went on a walk for the first time among the tundra birds. They all build their nests on the ground, so their vulnerability is extreme. I gazed down at a single horned lark no bigger than my fist. She stared back as resolute as iron. As I approached, golden plovers abandoned their nests in hysterical ploys, artfully feigning a broken wing to distract me from the woven grass cups that couched their pale, darkly speckled eggs. Their eggs glowed with a soft, pure light, like the window light in a Vermeer painting.

"I walked on to find Lapland longspurs as still on their nests as stones, their dark eyes gleaming. At the nest of two snowy owls I stopped. These are more formidable animals than plovers. I stood motionless. The wild glare in their eyes receded. One owl settled back slowly over its three eggs, with an aura of primitive alertness. The other watched me -- and immediately sought a bond with my eyes if I started to move.

"I took to bowing on these evening walks. I would bow slightly with my hands in my pockets, towards the birds and the evidence of life in their nests -- because of their fecundity, unexpected in this remote region, and because of the serene arctic light that came down over the land like a breath, like breathing.

"I remember the wild, dedicated lives of the birds that night and also the abandon with which a small herd of caribou crossed the Kokolik River to the northwest, the incident of only a few moments. They pranced through like wild mares, kicking up sheets of water across the evening sun and shaking it off on the far side like huge dogs, bloom of spray that glittered in the air around them like grains of mica.

"I remember the press of light against my face. The explosive skitter of calves among the grazing caribou. And the warm intensity of the eggs beneath these resolute birds. Until then, perhaps because the sun was shining in the very middle of the night, so out of tune with customary perception, I had never known how benign sunlight could be. How forgiving. How run through with compassion in a land that bore so eloquently the evidence of centuries of winter."

I like to chose an author for a major re-read each winter -- by which I mean not the general re-reading that I'm always doing (in between reading books that are new to me, of course), but digging out a writer's entire backlist and reading it all at once. This kind of immersion creates a very different experience than my first encounter with those same books -- which, if the author is contemporary, took place more gradually over time as each text was written and published. Last year, you may recall, I was re-engaging with Terry Tempest William's work (oh, what a glorious re-read that was!), and this year it's Barry Lopez, starting (unchronologically, but because it's winter) with Arctic Dreams.

I find myself reading unusually slowly, savoring every page, every paragraph of his writing, which is poetic and precise in equal measure. In Japan, masters of various art forms are honored as National Living Treasures. Here in the West, surely Barry Lopez is one of ours.

Photographs above: snowy owl, golden plover with her clutch of eggs, Lapland larkspur, Lapland larkspur chick in a tundra nest, a caribou herd crossing the tundra, caribou crossing a river, a frisky caribou calf, and a golden plover nest on the tundra. The caribou herd on the tundra and the golden plover nest are by the wildlife photographer and activist Joel Satore, whose work I highly recommend. The other wildlife images come from Audubon and Arctic wildlife sites, photographers uncredited.

February 17, 2015

Animal People

After yesterday's long essay, I thought something a bit lighter would be nice for today: the whimsical, wonderful watercolor paintings of Akitaka Ito, based in Tokyo, Japan.

Ito was born in Kamakura, Kanagawa Prefecture in 1979, graduated from Tama Art University (Department of Graphic Design) in 2003, and has been a member of the Tokyo Illustrators Society since 2009.

You can see more of his enchanting work on his website, and on Tistory.

"Every animal is a tradition, and together they are a vast part of our heritage as human beings. No animal completely lacks humanity, yet no person is ever completely human. By ourselves, we people are simply balls of protoplasm. We merge with animals through magic, metaphor, or fantasy, growing their fangs and putting on their feathers. Then we become funny or tragic; we can be loved, hated, pitied, and admired. For us, animals are all the strange, beautiful, pitiable, and frightening things that they have ever been: gods, slaves, totems, sages, tricksters, devils, clowns, companions, lovers, and far more."

- mythic scholar Boria Sax (from The Mythical Zoo: An Encyclopedia Of Animals In World Myth, Legend, And Literature)

"We poetically construct our identity as human beings, together with our values, largely through reciprocal relationships with animals. They provide us with essential points of reference, as well as illustrations of the qualities that we may choose to emulate or avoid in ourselves. Any major change in our relationships with animals, individual or collective, reverberates profoundly in our character as human beings, in ways that go far beyond immediately pragmatic concerns. When a species becomes extinct, something perishes in the human soul as well."

- Boria Sax (from The Mythical Zoo)

"Our perfect companions never have fewer than four feet." - Colette

February 16, 2015

Little Deaths

It's a rather lengthy post today, for I'd like to share an essay I wrote recently on the subject of change, loss, aging, and myths of death and regeneration....

Winter

The earth now lies through nights drenched

in the still dark benediction of the rain

and dusky houses and branches stand out bleak

each day in mist, in white, and in the rustling wet.

All, all is rich and restful, with heavy

and secret and rich growth finding its way

through warm soil to every leaf and shoot

and binding everything – near, far – mysteriously

with moisture, fruitfulness, and great desire

- till one clear afternoon suddenly we see

the glistening grass, the tenderly rising grain

and know that life is served by rest.

How could I ever have thought of summer

as richer than this season’s mystery?

Van Wyk Louw's poem "Winter" has become a touchstone for me during the dark part of the year, for it reminds me not to measure my days by action and accomplishment only; it reminds me that life is also "served by rest," and that winter is the natural time for retreat, hibernation, and introspection. I seem to need a lot of rest these days -- obstensively because I am healing from an illness, but my spirit is in need of rest and healing too: of time in the dark, in the underworld of the psyche. It is winter. It is not yet time to bloom.

One year ago I was in Arizona closing down the Endicott West Arts Retreat, which was my last and longest home in the desert, and the final home of my American life. The closing of E-West was anticipated, planned for, and accomplished in the best possible way -- and yet I mourned its lost, and I've continued to mourn with each new season of the passing year. In folk wisdom it is said that the sharpest phase of grief must be weathered for a full year and a day, and I find this prescript strangely accurate, as though loss must be carried through all four seasons before its weight begins to lighten and life goes on.

I didn't, however, expect to be quite so rattled that E-West had come to its end. "It's just a life change," I tell myself firmly, exasperated by the strength and persistence of the feeling. "You wanted to move to Devon full-time. For heaven's sake, no one has died."

But, in fact, someone has died: the person I used to be in Arizona. My desert self. My younger self, who seems so different than the woman I am now, for she was physically stronger and thus quicker, bolder,  more intrepid in adventure than I am today...if also less wise, less tempered, less steady: the gifts of age and experience. That young woman is inside of me, of course, but I am not her; I will never be her again; and packing up my last home in the desert brought me face to face with this "little death."

more intrepid in adventure than I am today...if also less wise, less tempered, less steady: the gifts of age and experience. That young woman is inside of me, of course, but I am not her; I will never be her again; and packing up my last home in the desert brought me face to face with this "little death."

For many months I have carried the weight of loss like stones in the lining of my pocket -- stones rubbed smooth by handling -- finding comfort in their feel, their rattling sound, their familiarity. But eventually we must empty out our pockets, for life is full of these "little deaths" and if grief is left to accumulate, then the garment of our soul becomes threadbare, misshapen, and our spirit just as heavy as the stones. Death, as myth constantly reminds us, is not an end point but a station one passes through as life turns on the Great Wheel of renewal: each self (representing the stages of our lives) dies so that the next one can be born; death and birth, endlessly repeated. We can't move forward (with our lives, our art) without these endings, these little deaths, these acts of letting go, which create the space for new ideas and fresh momentum.

In the mythological calendar, the passage from winter into spring is the perfect time for giving stones back to the earth. The Corn King/Year King/Winter King has died, and will be re-born with the greening of the hills: a virile young consort for the Goddess, his seed ensuring the land's fecundity...until he, too, withers with the dying of the year and emerges again next spring.

This ancient theme of an agricultural king who dies and regenerates each year is reflected in the traditional British folksong of John Barleycorn:

There was three men come out of the West

Their fortunes for to try

And these three men made a solemn vow

John Barleycorn must die.

They ploughed, they sowed, they harrowed him in

Throwing clods all on his head

And these three men made a solemn vow

John Barleycorn was dead.

They've left him in the ground for a very long time

Till the rains from heaven did fall

Then little Sir John's sprung up his head

And so amazed them all

They've left him in the ground till the Midsummer

Till he's grown both pale and wan

Then little Sir John's grown a long, long beard

And so become a man . . .

(Read the full lyrics and hear the song here. )

Mythic scholars have linked John Barleycorn to Beowa (the Anglo-Saxon god of barley, grain, and agricultural), and to Byggvir (the Norse god of barley, grain, and the art of milling), for similar stories of sacrifical death and resurrection are associated with all three figures.

One of the best known stories of death and re-birth is the Greek myth of Persephone, who was the daughter of Demeter, goddess of grain, fertility, and patroness of marriage. (Demeter's name derives from "spelt mother," spelt being an early form of wheat.) When Persephone is abducted to the Underworld by Hades (god of the dead), her mother's grief causes the seasons to stop, love-making to cease, and all living things to fail to grow...until Zeus intervenes and Persephone is returned, but only for six months of each year. The girl has eaten pomegranate seeds in Hell, binding her to Hades in the autumn and winter. Each spring, she returns to her mother, and the greening of the earth begins anew.

The veneration of Demeter, Persephone, and the cosmic cycle of death and re-birth was at the core of the Eleusinion Mysteries, whose initiatory rites took place each year just as the crops were sown. Beginning in an old cemetery in Athens, the participants walked in procession all the way to Eleusis, stopping at certain places along the route to shout obscenities. (This was in honor of Iambe, an old woman who's earthy stories had made Demeter laugh during her season of sorrow.) In Eleusis, the initiates fasted for a day (as Demeter did during her period of grief), then broke their fast with a special medicinal brew of barley water and mint. Little is known about the final rituals as the participants (sometimes several thousands of them) gathered together in the sect's great hall, for it was strictly forbidden for such sacred things to be spoken of in public.

Demeter, often pictured wearing a wreath of wheat or corn, has much in common with Selu, the Corn Mother of the Cherokee Nation, also associated with agriculture, fertility, and the sanctity of marriage. When her grandsons break a strict taboo and spy on Selu's mysteries, she tells them she will have to leave them and die -- but that even in death she will look after them, provided they restore the harmony they have broken by performing certain rituals. "Clear a circle of land in front of the house," she says. "Take my body and drag it seven time around the circle. Then you must keep watch all night and see what happens."

The boys follow their grandmother's instructions, and from the places where Selu's blood speckles the ground comes the very first crop of corn, a sacred food which is still an important staple of the People today. In some versions of the story, however, the lazy boys clear only a small piece of land, and drag Selu's body only twice around the circle, which is why corn doesn't grow everywhere and we must work hard to cultivate it.

Many carnival celebrations around the world are rooted in older pagan rites honoring the passage from winter to spring: anarchic, riotous affairs in which laughter and satire are given a social outlet and a sacred context. Alan Weisman described carnaval as it's still practiced in the villages of northern Spain:

"In Laza, the event is known by its Galician name, entroido: introduction, entry. Elsewhere in Spain and Europe where it is still observed, and in Latin America, where it has been transplanted, it is called carnaval. Centuries ago, when Christianity superimposed its holy calendar on the cycles of nature, the formerly pagan celebration became a brief, sanctioned burst of scheduled excess before 40 somber days of Lenten abstinence and repentance. (One theory holds that the word carnaval derives from 'carne va'—'there goes the meat.') Lent concludes with Easter, the celebration of Christ's Resurrection, coinciding handily with the spring equinox -- resurrection of the pagan sun god."

This, notes Alan, is the one time of year when authority figures are ignored, or mocked, and the people reign. "Power is concentrated in the masks thundering by, borne by the sons of the village itself, lashing the crowd ever harder. Priest and politician alike must hide or be pummeled with insult and ridicule; the world is turned upside-down and shaken until the established order cracks loose. Anything is possible, everything is allowed: Humans transform themselves into animals; males become females; peons strut like kings. Social station is scorned, decorum is debunked, blasphemy goes unblamed. In neighboring villages, normally sober citizens drench each other with buckets of water; in Laza, they sling rags soaked in mud until everyone is reduced to muck. Bags appear containing ashes, flour, and -- most prized of all -- fertilizer crawling with red and black ants. A frenzy erupts; the air fills with stinging, fragrant grime, coating everyone with the earth's sheer essence. Men and women throw each other to the ground and roll in the street. With any luck, the heavens will be shocked and the new season jarred awake. Then, once again, day can steal hours back from the night, vegetation will arouse from hibernation, spring will heave aside winter, and what was dead can live again."

(To read Alan's full article, go here.)

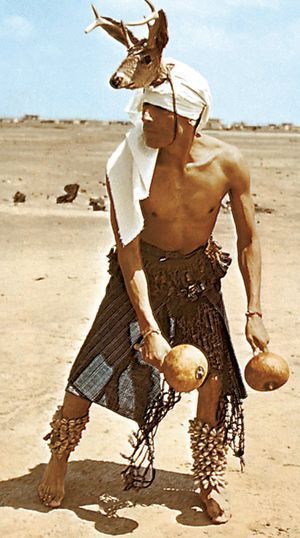

Re-enactment of the mythic cycle of death and re-birth can still be found in many sacred traditions, from the ritual practices of Siberian shamans to the Easter pageants of Christianity. In the Border region of southern Arizona, where Mexican American, Native American and Euro-American cultures all come together, the Easter ceremonies of the Yaqui (Yoeme) tribe contain a fascinating mix of spiritual traditions (similar to those of the Mayo and other tribes of northern Mexico). Private rituals practiced in the months between Christmas and Easter, most intensively during the weeks of Lent, culminate in a public drama enacting an unusual version of Christ's Passion, blending ancient Yaqui mystical beliefs with 17th-century Spanish Catholicism. The "three Marys" (figures of the Blessed Virgin) are  guarded in an open-sided church by hymn-singing women, matachins (a dance society of men and boys), pahkola dancers (a kind of holy clown), and the deer dancer -- an enchanted figure from the old Yaqui "religion of the woods." Opposing them are the forces of Judas: faceless fariseos, dressed in black, and chapayekas wearing elaborate masks, strings of rattles, and painted wooden swords.

guarded in an open-sided church by hymn-singing women, matachins (a dance society of men and boys), pahkola dancers (a kind of holy clown), and the deer dancer -- an enchanted figure from the old Yaqui "religion of the woods." Opposing them are the forces of Judas: faceless fariseos, dressed in black, and chapayekas wearing elaborate masks, strings of rattles, and painted wooden swords.

These dark figures march and dance around the church for many days and nights...and eventually, on the last day before Easter, they attack. The church bells ring, the deer dancer leaps, the faithful pelt the dark forces with flowers. The watching crowds throw flowers and confetti, shouting "Gloria! Gloria! Gloria!" The dark ones fall back, regroup, march...and then attack once more. Again they're driven back. On the third attack they are overcome by the forces of good: by songs, prayers, armloads of flowers. They strip off weapons, black scarves and masks (subsequently burned on a huge bonfire), and relatives drag the exhausted men back into the safety of the church -- a ritual resurrection, dedicating new lives to the forces of good.

The deer and pahkola dancers have been incorporated into this ritual, yet come from the tribe's pre-Christian past. They are, in one sense, shamanic figures, able to cross over the borders between the human world of the Baptised Ones, the modern Yaqui, to the flower world of the ancestors, a magical people called the Surem.

When we look at traditional folktales, it's striking how many address the subject of loss. A sizeable number of tales begin with the loss of a parent, a sibling, a fortune, a home, or an identity -- and only rarely does that which is missing return again at the end of the story. Instead, loss is the catalyst that leads to transformation.

The older versions of fairy tales were unflinching in their portrayal of calamity: kings abruptly beggared, queens dying young, children orphaned, cursed, and disowned. In The Handless Maiden, the heroine's hands are cut off at the wrist by her own father. The subsequent story of her journey through the world, rendered nearly helpless by her loss and yet still possessed of kindness and courage, speaks to everyone who has ever felt the wound of a loved one's betrayal. In The Seven Ravens, retold by the Brothers Grimm, seven princes lose their humanity due to their  father's carelessness. Salvation comes from their young sister, who bravely suffers a loss of her own: she must cut off her little finger to make the key to unlock their prison. Beauty gives up her home and future to save her father from a beast; Cinderella is transformed by the loss of her mother from a coddled daughter to a kitchen drudge, until the simple loss of a shoe transforms her again and she becomes a princess. Sleeping Beauty loses one hundred years of life; her parents lose a precious daughter as the vines grow high and her bedchamber is shrouded in roses and silence.

father's carelessness. Salvation comes from their young sister, who bravely suffers a loss of her own: she must cut off her little finger to make the key to unlock their prison. Beauty gives up her home and future to save her father from a beast; Cinderella is transformed by the loss of her mother from a coddled daughter to a kitchen drudge, until the simple loss of a shoe transforms her again and she becomes a princess. Sleeping Beauty loses one hundred years of life; her parents lose a precious daughter as the vines grow high and her bedchamber is shrouded in roses and silence.

These were tales, in their older forms, meant for adult audiences, not the nursery; and in some of them, the depiction of grief and loss is sharp and brutal. This is particularly true of the literary fairy tales of Hans Christian Andersen, which were beloved by adult readers across Europe in Andersen's lifetime. Here, unlike Disneyfied fairy tales today, we're never assured of a happy ending; here, the Little Mermaid is forgotten by her prince, the Brave Tin Soldier melts in the stove, and the Little Matchgirl dies alone, frozen by the breath of winter.

Though children also experience grief (and sometimes love the saddest of tales), the subject of loss as a literary theme becomes more and more resonant as we age -- as the passing years bring with them the inevitable loss of friends and family members; of homes and jobs; of innocence; of wild lands lost to development and memories lost to the ravages of time; of the many things we cling to, mourn in passing, and learn to live without.

"To live in this world," advised poet Mary Oliver, "you must learn to do three things: to love what is mortal; to hold it against your bones knowing your own life depends on it; and, when the time comes to let it go, to let it go."

Like myth, the great fantasy tales of our day have much to tell us about "loving what is mortal" and letting it go. Tolkien's Lord of the Rings, for example, and Ursula Le Guin's early "Earthsea" books, revolve around the adventures of young heroes -- but loss, change, and the impact of life's "little deaths" are also major themes. (In "Earthsea," the aging of the heroes is beautifully explored as the series progresses.)

Ellen Kushner -- who entered the fantasy field, like me, as a young writer/editor in the 1980s -- has pointed out that our generation of fantasists is now middle-aged or beyond. "Our concerns are different now," she muses. "If we stick to writing fantasy, what are we going to do? Traditionally, there's been the coming-of-age novel, and the quest novel, which is the finding of self. We're past the early stages of that. I can't wait to see what people do with the issues of middle-age in fantasy. Does fantasy demand that you stay in your adolescence forever? I don't think so. Tolkien's books are not juvenile. The Lord of the Rings is about losing things you've loved, which is a very middle-aged concern. Frodo's quest is a middle-aged man's quest, to lose something and to give something up, which, as you age, is what you start to realize is going to happen to you. Part of the rest of your life is learning to give things up."

Learning to give things up....

I'm thinking now of my last night at Endicott West, saying goodbye to a place that had held so much of my life and so many of my dreams. I'd wanted to let it go lovingly, gracefully, and I was surprised by just how hard that was. The ghost of my younger self stood beside me, growing thinner, paler, more insubstantial with every moment that passed.

My partners and I lit one last blaze in the campfire circle beneath the stars, and thanked the spirits in the old tribal way: with sage, cedar, and the desert tobacco that I'd grown and cured on that beautiful land. Then we popped the cork on a bottle of champagne and reminisced about the days of building the Retreat, acknowledging all the blessing we'd received there, all the blessing we'd carry on from it. This is what I wanted to take back home to Devon: this good fellowship and these good memories, not the stony weight of loss and grief for a phase of life that had reached its natural end. But of course we don't control these things. Grief comes when it will, and takes the time it takes, and there's no short-cut to moving through it. Grief must be honored. It's the heart's clear measure of the value of what we've loved, and what we've lost.

"In my own worst seasons," wrote our former E-West neighbor Barbara Kingsolver (in her essay collection High Tide in Tucson), "I've come back from the colorless world of despair by forcing myself to look hard, for a long time, at a single glorious thing: a flame of red geranium outside my bedroom window. And then another: my daughter in a yellow dress. And another: the perfect outline of a full, dark sphere behind the crescent moon. Until I learned to be in love with my life again. Like a stroke victim retraining new parts of the brain to grasp lost skills, I have taught myself joy, over and over again.''

Well, I've not been in "despair" exactly, I've just been feeling a little bit...off. Blame it on poor health. Blame it on the weather, which is wet and cold, unlike the winters of the desert. Blame it on exhaustion; I've been carrying these stones for a full year and a day, and it's time to put them down.

Here in Devon, it's been a long grey winter...but every now and then the sun breaks through. I put on muddy boots, whistle for the dog, and we squelch our way through hills that glimmer "in the rustling wet" (to quote Van Wyk Louw's poem) like the saturated colors of a watercolor painting. These colors remind me that grief will pass. Winter will pass. The months, the seasons, the Great Wheel will turn. I have re-learned joy many times before, and I am simply doing it one more time. The land that is now my home lifts and sustains me.

And spring is coming.

Image credits and descriptions are in the picture captions. Run your cursor over the pictures to see them. This essay is dedicated to Ellen & Delia.

Image credits and descriptions are in the picture captions. Run your cursor over the pictures to see them. This essay is dedicated to Ellen & Delia.

Tunes for a Monday Morning

Over the last few weeks I've posted videos by some of the younger generation of musician-activists who impress me so much (Mary Lambert, Rising Appalachia), and here, today, is my favorite one them all, a young man whose music often reduces me to tears: Nahko Bear (singer-songwriter, guitarist, pianist), with his band Medicine for the People. I'm deeply in love with his two albums (On the Verge and Dark As Night), and admire the tireless work he is doing on behalf of environmental organizations, indigenous rights organizations, and young people everywhere.

Nahko was born of mixed Apache/Mohawk, Puerto Rican and Filipino heritage, adopted and raised by a conservative white family in Oregon, and now divides his time between Oregon and Hawaii. He has used his music to explore and heal the trauma of his origins (he was conceived through rape, and his biological father was later murdered), finding true "medicine" in art, nature, and Spirit -- a medicine that he passes on in a remarkably joyful way. He takes identity politics to its next healing step: a pride in his mixed-race ancestry and up-bringing (which he has in common with an ever-increasing number of culturally mixed young Americans) combined with a respect for women, a belief in the power of community, and an embrace of all good-hearted people as part of his tribe, no matter what their background. If you'd like to learn more, his bio is here, and you can read a good interview with Nahko here.

Above: The video for Nahko's song "Great Spirit."

Below: The video for "Black as Night."

Below: A very simple man-with-guitar performance of Nahko's lovely song "Wash It Away," filmed beside a creek at the Wanderlust Festival.

"Everyone, no matter what their cultural background, has a right to discover the sacred in nature; to heal and be redeemed spiritually by nature; and to revere the ancestors. We are all haunted and saved by our memories." - Martha Brooks (Bone Dance)

And last: The exuberant video for "Me and Mr. Washington."

If you'd like a little more music this morning, you could also try "Father Mountain," "Creation's Daughter" with Sandra Fay, and a charming informal duet with Rising Appalachia's Leah Song.

Thank you, Great Spirit, for Nahko Bear and his friends and collaborators. We've been waiting for them, it seems, a long, long time. Circle up, warriors, circle up. Mitakuye Oyasin.

February 13, 2015

On St. Valentine's Day

''To love at all is to be vulnerable. Love anything and your heart will be wrung and possibly broken. If you want to make sure of keeping it intact you must give it to no one, not even an animal. Wrap it carefully round with hobbies and little luxuries; avoid all entanglements. Lock it up safe in the casket or coffin of your selfishness. But in that casket, safe, dark, motionless, airless, it will change. It will not be broken; it will become unbreakable, impenetrable, irredeemable. To love is to be vulnerable.''

''To love at all is to be vulnerable. Love anything and your heart will be wrung and possibly broken. If you want to make sure of keeping it intact you must give it to no one, not even an animal. Wrap it carefully round with hobbies and little luxuries; avoid all entanglements. Lock it up safe in the casket or coffin of your selfishness. But in that casket, safe, dark, motionless, airless, it will change. It will not be broken; it will become unbreakable, impenetrable, irredeemable. To love is to be vulnerable.''

- C.S. Lewis (The Four Loves)

''Being deeply loved by someone gives you strength, while loving someone deeply gives you courage.''

- Lao Tzu

Happy St. Valentine's Day to my husband and family (near and far), and to all of you and your loved ones too. If you'd like to read about the folklore of valentines, go here.

Pictures above: "Kimberley Tree People, Norfolk" and "Prickly Cactus Fairies, Arizona" from my sketchbooks. Howard, Tilly and me on the north Devon coast (photo taken by our daughter).

Pictures above: "Kimberley Tree People, Norfolk" and "Prickly Cactus Fairies, Arizona" from my sketchbooks. Howard, Tilly and me on the north Devon coast (photo taken by our daughter).

February 12, 2015

At the gates of dawn

1

Before this world existed, the holy people made themselves visible

by becoming clouds, sun, moon, trees, bodies of water, thunder

rain, snow, and other aspects of this world we live in. That way,

they said, we would never be alone. So it is possible to talk to them

and pray, no matter where we are and how we feel. Biyázhí daniidlí,

we are their little ones.

2

Since the beginning, the people have gone outdoors at dawn to pray,

The morning light, adinídíín, represents knowledge and mental awareness.

With the dawn come the holy ones who bring blessings and daily gifts,

because they are grateful when we remember them.

3

When you were born and took your first breath, different colors

and different kinds of wind entered through your fingertips

and the whorl on top of your head. Within us, as we breathe,

are the light breezes that cool a summer afternoon,

within us the tumbling winds that precede rain,

within us sheets of hard-thundering rain,

within us dust-filled layers of wind that sweep in from the mountains,

within us gentle night flutters that lull us to sleep.

To see this, blow on your hand now.

Each sound we make evokes the power of these winds

and we are, at once, gentle and powerful.

(from "Sháá Áko Dahjiníeh: Remember They Things They Told Us,"

published in Saánii Dahataal: The Women are Singing, University of Arizona Press)

Tapahonso is the Poet Laureate of the Navajo Nation, whose lands spread across Utah, Arizona, and New Mexico. You can read a lovely interview with her here.

Photographs: Woodland gate, early morning; and Tilly with a snowflake on her brow. Gentle and powerful.

Photographs: Woodland gate, early morning; and Tilly with a snowflake on her brow. Gentle and powerful.

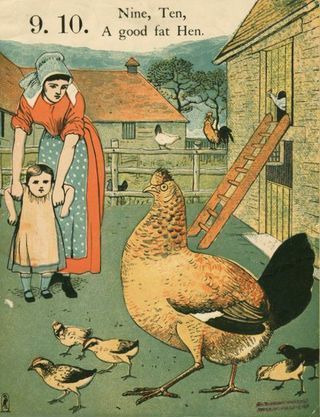

Hen Wives, Spinsters, and Lolly Willowes

In the colored fairy books of Andrew Lang (The Red Fairy Book, The Blue Fairy Book, etc.), there is a figure who has always intrigued me: the Hen Wife, related to the witch, the seer, and the herbalist, but different from them too: a distinct and potent archetype of her own, an enchanted figure beneath a humble white apron. We find her dispensing wisdom and magic in the folk tales of the British Isles and far beyond (all the way to Russia and China): a woman who is part of the community, not separate from it like the classic "witch in the woods"; a woman who is married, domesticated like her animal familiars, and yet conversant with women's mysteries, sexuality, and magic.

Mythic writer Sharon Blackie described the Hen Wife like this on her blog Singing Over the Bones:

"If you look up the definition of ‘henwife’ in most dictionaries, you’ll find it given as something along the lines of ‘woman who keeps poultry’. But that isn’t it at all: a henwife is so much more than that, as so many folk and fairytales from Ireland and Scotland show. In those tales, the henwife is often a herbalist or a healer, and is  always synonymous with the Wise Old Woman archetype: the Cailleach personified. Think, for example, of the fine Scottish tale ‘Kate Crackernuts’, about the henwife and her cauldron of wisdom. Or the old Irish tale about three sisters, ‘Fair, Brown and Trembling’. The fact that the henwife also keeps hens is part and parcel of this archetype, but although the heroine of the story may go to her looking simply for eggs, she always comes away with rather more than she bargained for."

always synonymous with the Wise Old Woman archetype: the Cailleach personified. Think, for example, of the fine Scottish tale ‘Kate Crackernuts’, about the henwife and her cauldron of wisdom. Or the old Irish tale about three sisters, ‘Fair, Brown and Trembling’. The fact that the henwife also keeps hens is part and parcel of this archetype, but although the heroine of the story may go to her looking simply for eggs, she always comes away with rather more than she bargained for."

Colleen Szabo, writing in Cabinet des Fées, views the Hen Wife through a Jungian lens. She is, says Szabo, "a combination of the old bird goddesses and the figure we now call 'witch'; a crone or wise woman who knows of the inner life, of natural processes and developments, of all their alchemical magic. She is also a keeper of knowledge about a woman’s sexuality; the old tradition of a 'hen’s night' is currently being revived. In that tradition, the night before a wedding, older and wiser hen-wives teach the wife-to-be about sexuality, including pregnancy, all of which falls within the overall category of creative power, of course. Whatever our creative genres might be, their products can always be symbolized by the metaphor of the child, including our creative efforts to renew and transform ourselves."

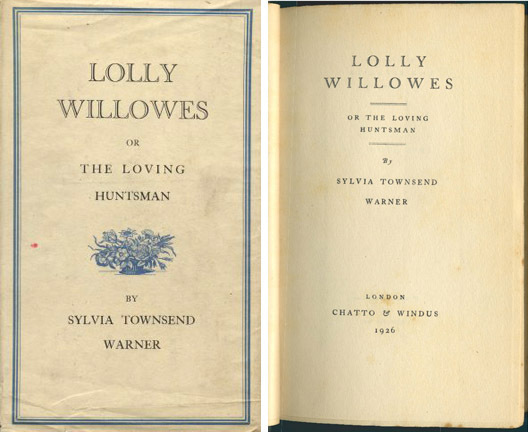

My favorite depiction of the Hen Wife is in this gorgeous passage from the novel Lolly Willowes by Sylvia Townsend Warner (1893-1978):

"Laura never became as clever with the birds as Mr. Saunter. But when she had overcome her nervousness, she managed them well enough to give herself a great deal of pleasure. They nestled against her, held fast in  the crook of her arm, while her fingers probed among the soft feathers and rigid quills of their breasts. She liked to feel their acquiescence, their dependence upon her. She felt wise and potent. She remembered the henwife in fairy tales, she understood now why kings and queens resorted to the henwife in their difficulties. The henwife held their destinies in the crook of her arm, and hatched the future in her apron. She was sister to the spaewife, and close cousin to the witch, but she practiced her art under cover of henwifery; she was not, like her sister and her cousin, a professional. She lived unassumingly at the bottom of the king's garden, wearing a large white apron and very possibly her husband's cloth cap; and when she saw the king and queen coming down the gravel path she curtseyed reverentially, and pretended it was eggs they had come about. She was easier to approach than the spaewife, who sat on a creepie and stared at the smoldering peats till her eyes were red and unseeing; or

the crook of her arm, while her fingers probed among the soft feathers and rigid quills of their breasts. She liked to feel their acquiescence, their dependence upon her. She felt wise and potent. She remembered the henwife in fairy tales, she understood now why kings and queens resorted to the henwife in their difficulties. The henwife held their destinies in the crook of her arm, and hatched the future in her apron. She was sister to the spaewife, and close cousin to the witch, but she practiced her art under cover of henwifery; she was not, like her sister and her cousin, a professional. She lived unassumingly at the bottom of the king's garden, wearing a large white apron and very possibly her husband's cloth cap; and when she saw the king and queen coming down the gravel path she curtseyed reverentially, and pretended it was eggs they had come about. She was easier to approach than the spaewife, who sat on a creepie and stared at the smoldering peats till her eyes were red and unseeing; or  the witch, who lived alone in the wood, her cottage window all grown over with brambles. But though she kept up this pretense of homeliness she was not inferior in skill to the professionals. Even the pretence of homeliness was not quite so homely as it might seem. Laura knew that the Russian witches live in small huts mounted upon three giant hen's legs, all yellow and scaly. The legs can go; when the witch desires to move her dwelling the legs stalk through the forest, clattering against the trees, and printing long scars upon the snow.

the witch, who lived alone in the wood, her cottage window all grown over with brambles. But though she kept up this pretense of homeliness she was not inferior in skill to the professionals. Even the pretence of homeliness was not quite so homely as it might seem. Laura knew that the Russian witches live in small huts mounted upon three giant hen's legs, all yellow and scaly. The legs can go; when the witch desires to move her dwelling the legs stalk through the forest, clattering against the trees, and printing long scars upon the snow.

"Following Mr. Saunter up and down between the pens, Laura almost forgot where and who she was, so completely had she merged her personality into the henwife's. She walked back along the rutted track and down the steep lane as obliviously as though she were flitting home on a broomstick."

I first discovered Sylvia Townsend Warner's fiction through Kingdoms of Elfin (a collection of the adult fairy stories as dry and fizzy as the best champagne), but Lolly Willowes, when I first read it back in my 20s, seemed altogether different. I'm embarrassed now to admit that I found the novel slight and unmemorable, almost twee; and it wasn't until a recent re-reading that I finally understood it as the masterpiece it is. I was just too young for Lolly Willows, and  too ignorant of the social context in which Townsend Warner was writing in the 1920s: the restricted lives of "spinisters" in Victorian and Edwardian England.

too ignorant of the social context in which Townsend Warner was writing in the 1920s: the restricted lives of "spinisters" in Victorian and Edwardian England.

"The issue that the novel tackles head-on is that of gender," explains another Townsend Warner fan, contemporary British novelist Sarah Waters. "In the 1910s and 20s British sexual mores were shaken up as never before: the war saw women taking on new jobs, gaining new responsibilities and freedom, and, though the majority of the jobs were savagely withdrawn with the return to peace, many of the liberties remained; in 1918, partly as a recognition of their contribution during the years of conflict, women were at last granted the vote. For the first decade of its life, however, the new franchise was an incomplete one, available only to women over 30 who were also householders or married to householders (which meant that single women such as Laura, middle-aged but financially dependent on male relatives, remained without it), and there was still huge pressure on women to conform to social norms.

"The recent tragic loss of so many young male lives had inflamed existing tension over the idea of the 'surplus woman' and, with postwar anxiety about British 'racial health' prompting celebrations of family life and maternity, the spinster -- a benign if dowdy figure in 19th-century culture -- was being subtly redefined as a social problem. The popularisation of Freudian ideas about sexual repression only added to her woes, pathologising elderly virgins as chronically unfulfilled. Many novelists of the period responded to this – some, such as Clemence Dane, with representations of emotionally vampiric single women, which reinforced the new stereotypes, but others, such as Radclyffe Hall, Winifred Holtby and Vera Brittain, with more sensitivity to the pressures faced by ageing, unmarried daughters, and more sympathy for them in their efforts to follow non-traditional paths. Two fascinating novels that particularly resemble Lolly Willowes, and which Townsend Warner could be said effectively to have rewritten, are W.B. Maxwell's Spinster of this Parish (1922) and F.M. Mayor's The Rector's Daughter (1924).

"Like Townsend Warner, Maxwell and Mayor chose as their subjects unmarried women of the late-Victorian age -- that is, the final generation to have assumed as a matter of course that its single daughters would remain in the family home, dutifully servicing the needs of senior relatives. Again like her, they produced novels that are intensely alive to the contrast between the unglamorous exteriors of their 'old maid' heroines and the women's actual, deeply passionate, emotional lives. But the titles of the three novels reveal a significant difference. As phrases, 'spinster of this parish' and 'the rector's daughter' testify to the ways in which women are often occluded by social and familial roles. Lolly Willowes, by contrast, is a statement of individuality. Laura's journey, too, is very different from that of Maxwell's and Mayor's heroines, the former of whom spends decades as the unacknowledged mistress of a celebrated explorer, and is finally rewarded by marriage to him, while the latter dies after a short but 'useful' life, with her passionate love for a clergyman unfulfilled.

"For the first half of Townsend Warner's novel, Laura looks set to follow their example. A tomboy in childhood, she is soon 'subdued into young-ladyhood,' and after the death of her parents she joins the London household of her unimaginative brother, Henry, where she becomes the spinster 'Aunt Lolly,' slightly pitied, slightly patronised, but 'indispensable for Christmas Eve and birthday preparations' -- an embodiment, in other words, of an old-fashioned female tradition for which her up-to-the-minute niece,  Fancy, who has driven lorries during the war, has fine, flapperish contempt. But Laura has depths unsuspected by her deeply conventional relatives, and with her move to Great Mop she grows ever more subversive. She quietly rejects her family. She refuses to be defined by her relationships with men. She breaches the social barriers between gentry and working people. And, though she enjoys being part of the Great Mop community, her intensest pleasures are solitary ones. Again looking forward to Virginia Woolf, the novel asserts the absolute necessity of 'a room of one's own', and Laura gains a clear-sighted understanding of the combined financial and cultural interests that serve to keep women in domestic, dependent roles: 'Society, the Law, the Church, the History of Europe, the Old Testament . . . the Bank of England, Prostitution, the Architect of Apsley Terrace, and half a dozen other useful props of civilisation' have robbed her of her freedom just as effectively as have her patronising London relatives. It is this analysis that informs her conversation with Satan near the end of the novel, in which she unfolds her memorable vision of women as sticks of dynamite, 'long[ing] for the concussion that may justify them.' If women, Townsend Warner implies, are denied access to power through legitimate means, they will turn instead to illegitimate methods -- in this case to Satan himself, who pays them the compliment of pursuing them and then, having bagged them, performs the even more valuable service of leaving them alone."

Fancy, who has driven lorries during the war, has fine, flapperish contempt. But Laura has depths unsuspected by her deeply conventional relatives, and with her move to Great Mop she grows ever more subversive. She quietly rejects her family. She refuses to be defined by her relationships with men. She breaches the social barriers between gentry and working people. And, though she enjoys being part of the Great Mop community, her intensest pleasures are solitary ones. Again looking forward to Virginia Woolf, the novel asserts the absolute necessity of 'a room of one's own', and Laura gains a clear-sighted understanding of the combined financial and cultural interests that serve to keep women in domestic, dependent roles: 'Society, the Law, the Church, the History of Europe, the Old Testament . . . the Bank of England, Prostitution, the Architect of Apsley Terrace, and half a dozen other useful props of civilisation' have robbed her of her freedom just as effectively as have her patronising London relatives. It is this analysis that informs her conversation with Satan near the end of the novel, in which she unfolds her memorable vision of women as sticks of dynamite, 'long[ing] for the concussion that may justify them.' If women, Townsend Warner implies, are denied access to power through legitimate means, they will turn instead to illegitimate methods -- in this case to Satan himself, who pays them the compliment of pursuing them and then, having bagged them, performs the even more valuable service of leaving them alone."

(I highly recommend reading Water's full essay, "Sylvia Townsend Warner: the neglected writer," published by The Guardian.)

I think if I was teaching Lolly Willowes today, I would first ask students to read Singled Out by Virginia Nicholson, an absolutely engrossing book about single women in Britain between the wars, which I can't recommend highly enough. (All of Nicholson's books on social history are just terrific.) It's also interesting to read Townsend Warner's fiction with some knowledge of her fascinating life as a feminist, leftist, and lesbian (she was in a long-term relationship with fellow writer Valentine Ackland) at a time when this was far from the norm for respectable "lady writers." She loved living in the countryside, and some of her best stories take place in rural settings -- but they are so much more than charming tales of villages and vicarages; beneath the mannered surface they contain a biting wit, deep wisdom, and sharp social critique, à la Jane Austen. There's a good biography of Townsend Warner by Claire Harman, plus various volumes of the author's correspondence, and a lovely memoir by Townsend Warner's wife (or so she'd be acknowledged today), Valentine Ackland.

And this brings us back to the Hen Wife -- that figure of magic who dwells comfortably among us, not off by the crossroads or in the dark of the woods; who is married, not solitary; who is equally at home with the wild and domestic, with the animal and human worlds. She is, I believe, among us still: dispensing her wisdom and exercising her power in kitchens and farmyards (and the urban equivalent) to this day -- anywhere that women gather, talk among themselves, and pass knowledge down to the next generations.

And Hen Husbands? What is their role in folklore, fairy tales, and daily life? I confess I do not know. Those are Men's Mysteries, hidden and ancient, and not for the likes of me to speak of....

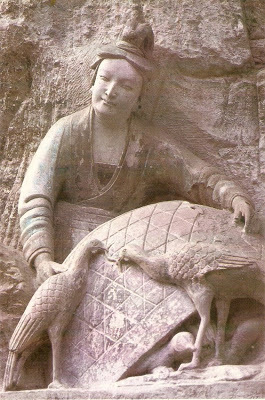

The art above is: a folktale illustration by Ukranian artist Vladislav Erko; "The Hen Wife" by Scottish printmaker Helen G. Stevenson (circa 1930s); a Danzu carving of a Chinese hen wife; "The Hen Wife" by English painter Charles Sims (1872-1928); a nursery rhyme illustrated by English painter & designer Walter Crane (1845-1915); "Baba Yaga" (from Russian folklore) by my Chagford neighbor Rima Staines; a Mother Goose illustration, artist unknown; a photograph of Sylvia Townsend Warner; the first edition of Lolly Willowes; a stereotypical Victorian image of a spinster by English painter Walter Dendy Sadler (1854-1923); an 18th century spinster by Thomas Cheesman (1760-1834) - reminiscent of the fact that the term was once used for all women who spin, card, and weave, rather than as a pejorative term for unmarried women; a decoration by Walter Crane (1845-1915); and "Samurai Chicken Defender" by my Chagford neighbor David Wyatt, from his "Local Characters" series.

The art above is: a folktale illustration by Ukranian artist Vladislav Erko; "The Hen Wife" by Scottish printmaker Helen G. Stevenson (circa 1930s); a Danzu carving of a Chinese hen wife; "The Hen Wife" by English painter Charles Sims (1872-1928); a nursery rhyme illustrated by English painter & designer Walter Crane (1845-1915); "Baba Yaga" (from Russian folklore) by my Chagford neighbor Rima Staines; a Mother Goose illustration, artist unknown; a photograph of Sylvia Townsend Warner; the first edition of Lolly Willowes; a stereotypical Victorian image of a spinster by English painter Walter Dendy Sadler (1854-1923); an 18th century spinster by Thomas Cheesman (1760-1834) - reminiscent of the fact that the term was once used for all women who spin, card, and weave, rather than as a pejorative term for unmarried women; a decoration by Walter Crane (1845-1915); and "Samurai Chicken Defender" by my Chagford neighbor David Wyatt, from his "Local Characters" series.

February 10, 2015

Back in the hills at dawn

From "Knowing Our Place," published in Small Wonder by Barbara Kingsolver:

"In the summer of 1996 human habitation on earth made a subtle, uncelebrated passage from being mostly rural to being mostly urban. More than half of all humans now live in the cities. The natural habitat of our species, then, officially, is steel, pavements, streetlights, architecture, and enterprise -- the hominid agenda.

"With all due respect to the wondrous ways people have invented to amuse themselves and one another on paved surfaces, I find this exodus from the land makes me unspeakably sad. I think of children who will never know, intuitively, that a flower is a plant's way of making love, or what silence sounds like, or that trees breathe out what we breathe in....

"Barry Lopez writes that if we hope to succeed in the endeavor of protecting natures other than our own, 'it will require that we reimagine our lives....It will require of many of us a humanity that we've not yet mustered, and a grace we were not yet aware we desired until we had tasted it.'

"And yet no endeavor could be more crucial at this moment. Protecting the land that once provided us with our genesis may turn out to be the only real story there is for us. The land still provides our genesis, however we might like to forget that our food comes from dank, muddy earth, and that the oxygen in our lungs was recently inside a leaf, and that every newspaper or book we pick up...is made from the hearts of trees that died for the sake of our imagined lives. What you hold in your hands [when you hold a book] is consecrated air and time and sunlight and, first of all, place. Whether we are leaving it or coming into it, it's here that matters, it is place. Whether we understand where we are or don't, that is the story: To be here or not to be.

"Storytelling is as old as our need to remember where the water is, where the best food grows, where we find our courage for the hunt. It's as persistent as our desire to teach our children how to live in this place that we have known longer than they have. Our greatest and smallest explanations for ourselves grow from place, as surely as carrots grow from dirt. I'm presuming to tell you something that I could not prove rationally but instead feel as a religious faith. I can't believe otherwise.

"A world is looking over my shoulder as I write these words; my censors are bobcats and mountains. I have a place from which to tell my stories. So do you, I expect. We sing the song of our home because because we are animals, and an animal is no better or wise or safer than its habitat and its food chain. Among the greatest of all gifts is to know our place."

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers