Terri Windling's Blog, page 140

April 16, 2015

From the archives:

I'm hunkering down to catch up on work and correspondence today, so here's a post from the archives that seems worth a revisit, addressing as it does some of the topics we've been discussing of late....

"The beauty of the earth is the first beauty," writes Irish poet and philosopher John O'Donohue, whose wise books I return to again and again. "Millions of years before us the earth lived in wild elegance. Landscape is the first-born of creation. Sculpted with huge patience over millenia, landscape has an enormous diversity of shape, presence, and memory. There is poignancy in beholding the beauty of landscape: it often feels as though it has been waiting for centuries for the recognition and witness of the human eye. In the ninth Duino Elgy, Rilke says:

Perhaps we are here in order to say: house,

Perhaps we are here in order to say: house,

bridge, fountain, gate, pitcher, fruit-tree, window...

To say them more intensely than the

Things themselves

Ever dreamed of existing.

"How can we ever know the difference we make to the soul of the earth? Where the infinite stillness of the earth meets the passion of the human eye, invisible depths strain towards the mirror of the name. In the word, the earth breaks silence. It has waited a long time for the word. Concealed beneath familiarity and silence, the earth holds back and it never occurs to us to wonder how the earth sees us. Is it not possible that a place could have huge affection for those who dwell there? Perhaps your place loves having you there. It misses you when you are away and in its secret way rejoices when you return. Could it be possible that a landscape might have a deep friendship with you? that it could sense your presence and feel the care you extend towards it? Perhaps your favourite place feels proud of you. We tend to think of death as a return to clay, a victory for nature. But maybe it is the converse: that when you die, your native place will fill with sorrow. It will miss your voice, your breath and the bright waves of your thought, how you walked through the light and brought news of other places. Perhaps each day our lives undertake unknown tasks on behalf of the silent mind and vast soul of nature. During its millions of years of presence perhaps it was also waiting for us, for our eyes and our words. Each of us is a secret envoi of the earth.

"We were once enwombed in the earth and the silence of the body remembers that dark, inner longing. Fashioned from clay, we carry the memory of the earth. Ancient, forgotten things stir within our hearts, memories from the time before the mind was born. Within us are depths that keep watch. These are depths that no words can trawl or light unriddle. Our neon times have neglected and evaded the depth-kingdoms of interiority in favour of the ghost realms of cyberspace. Our world becomes reduced to an intense but transient foreground. We have unlearned the patience and attention of lingering at the thresholds where the unknown awaits us. "

"'We are here to abet creation and to witness it, to notice each thing so each thing gets noticed," Annie Dillard concurs. "Together we notice not only each mountain shadow and each stone on the beach but we notice each others beautiful face and complex nature so that creation need not play to an empty house.''

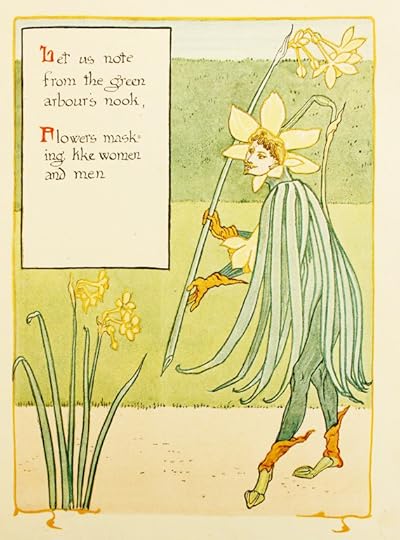

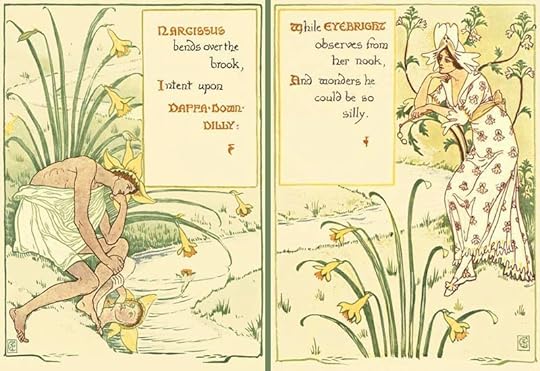

Pictures above: Daffodils in the village churchyard, and Tilly among the wild daffodils in our woods, spring 2013. The illustrations are by Walter Crane, published in Flowers from Shakespeare's Garden (1909). The John O'Donohue quotes are from Beauty: The Invisible Embrace (2004), the Annie Dillard quote is from an article in Life Magazine (1988), and the Robert Macfarlane quote is from The Old Ways (2012).

Pictures above: Daffodils in the village churchyard, and Tilly among the wild daffodils in our woods, spring 2013. The illustrations are by Walter Crane, published in Flowers from Shakespeare's Garden (1909). The John O'Donohue quotes are from Beauty: The Invisible Embrace (2004), the Annie Dillard quote is from an article in Life Magazine (1988), and the Robert Macfarlane quote is from The Old Ways (2012).

Little People Looking For a Good Home

I’m absolutely delighted that Greta Ward will be selling prints of mine at her Open Studio in Tucson, Arizona this weekend, including the little people pictured in this post, and a few lonely animal spirits as well. For more info on Tucson’s Open Studio weekend, go here.

If you’re interested in prints but you’re nowhere near Tucson, she’s also selling them by post through her website, while the limited supply of them lasts. Follow this link if you’re interested...and while you’re on Greta’s site, be sure to take a look at her absolutely gorgeous work too.

Can you give some little people a good home….?

The sense of wonder

"As a child, one has that magical capacity to move among the many eras of the earth," writes Valerie Andrews in A Passion for this Earth; "to see the land as an animal does; to experience the sky from the perspective of a flower or a bee; to feel the earth quiver and breathe beneath us; to know a hundred different smells of mud and listen unselfconsciously to the soughing of the trees."

But as Jay Griffiths cautions in her lastest book, Kith: The Riddle of the Childscape (which I'm reading now and highly recommend): "Children have been exiled from their kith, their square mile, a land right of the human spirit. Naturally kindled in green, they need nature, woodlands, mountains, rivers and seas both physically and emotionally, no matter how small a patch; children's spirits can survive on very little, but not on nothing. Yet woodlands are privatized ... while even the streets -- the commons of the urban child -- have been closed off to them."

What can we do to bring them back to the wild? Both the wild in the landscape and the wild in themselves?

"By suggestion and example, I believe children can be helped to hear the many voices about them," ecologist Rachel Carson wrote in The Sense of Wonder (published posthumously in 1965)."Take time to listen and talk about the voices of the earth and what they mean -- the majestic voice of thunder, the winds, the sound of surf or flowing streams."

Carsons words were important back in the '60s, and they are even more so today. As Alan Dyer states in "A Sense of Adventure" (Resurgence Magazine, Sept/Oct 2004):

"Children the world over have a right to a childhood filled with beauty, joy, adventure, and companionship. They will grow toward ecological literacy if the soil they are nurtured in is rich with experience, love, and good examples."

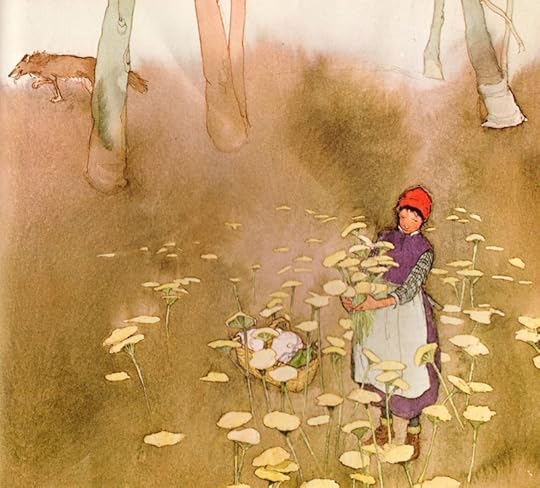

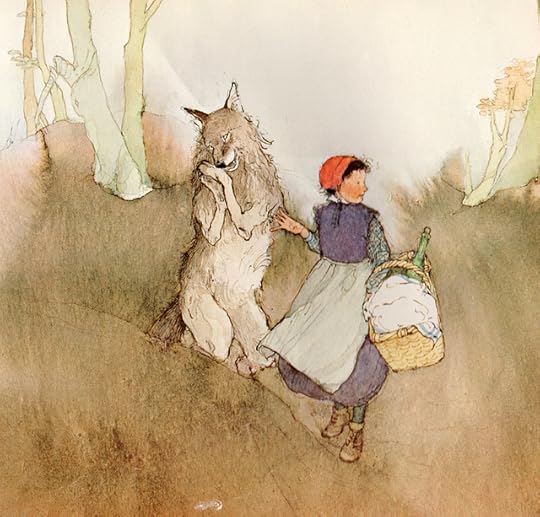

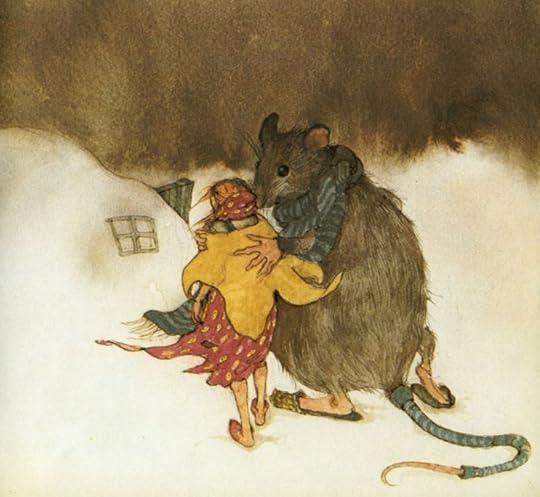

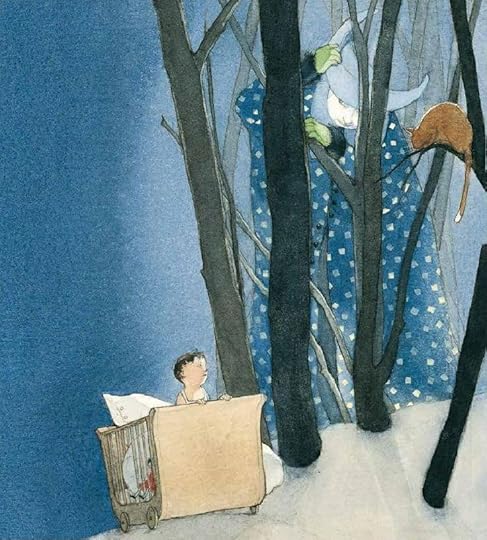

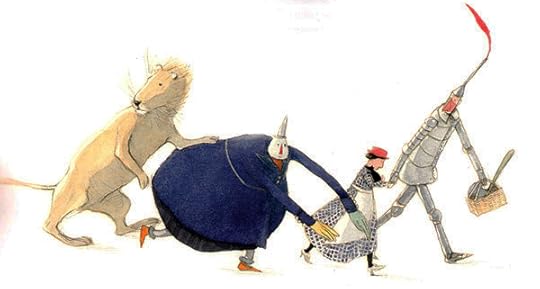

The paintings today are by one of my all-time favorite artists, the extraordinary Lisbeth Zwerger. Born in Vienna, Austria in 1954, she studied at the Applied Arts Academy in that city and has been illustrated  children's books since 1977, winning the prestigious Hans Christian Andersen Medal for "lasting contributions to children's literature" in 1990. Zwerger has very little web presence of her own, but you can find examples of her art on Pinterest and Tumblr -- or better still, go to her glorious books, including many fine illustrated editions of fairy tales by the Grimms, Andersen, and Oscar Wilde; classics such as Alice in Wonderland, The Wizard of Oz, The Nutcracker, and A Christmas Carol; and a very lovely art book, The Art of Lisbeth Zwerger -- which sits paint-stained and much-thumbed-through near my own drawing board, a constant source of inspiration.

children's books since 1977, winning the prestigious Hans Christian Andersen Medal for "lasting contributions to children's literature" in 1990. Zwerger has very little web presence of her own, but you can find examples of her art on Pinterest and Tumblr -- or better still, go to her glorious books, including many fine illustrated editions of fairy tales by the Grimms, Andersen, and Oscar Wilde; classics such as Alice in Wonderland, The Wizard of Oz, The Nutcracker, and A Christmas Carol; and a very lovely art book, The Art of Lisbeth Zwerger -- which sits paint-stained and much-thumbed-through near my own drawing board, a constant source of inspiration.

April 15, 2015

Children in the woods

From "Children in the Woods" by Barry Lopez:

"My wife and I do not have children, but the children we know, or children whose parents we are close to, are often here. They always want to go into the woods. And I wonder what to tell them. In the beginning, years ago, I think I said too much. I spoke with an encyclopedic knowledge of the names of plants or the names of birds passing through the season. Gradually I came to say less....

"I remember once finding a fragment of a raccoon's jaw in an alder thicket. I sat down alongside the two children with me and encouraged them to find out who this thing was -- with only the three teeth still intact in a piece of the animal's maxilla to guide them. The teeth told by their shape and placement what this animal ate. By a kind of visual extrapolation its size became clear. There were other clues, immediately present, which told, with what I could add of climate and terrain, how its broken jaw came to be lying there. And tiny tooth marks along the jaw's broken bone edge told of a mouse's hunger for calcium. We set the jaw back and went on."

"I think that children know that nearly anyone can learn the names of things; the impression made on them at this level is fleeting. What takes a lifetime to learn, they comprehend, is the existence and substance of myriad relationships: it is the relationships, not the things themselves, that ultimately hold the human imagination.

"The brightest children, it has often struck me, are fascinated by metaphor -- with what is shown in the set of relationships bearing on the raccoon, for example, to lie quite beyond the raccoon. In the end you are trying to make clear to them that everything found at the edge of one's senses -- the high note of the winter wren, the thick perfume of propolis that drifts downward from the spring willows, the brightness of woodchips scattered by the beaver -- that all this fits together. The indestructibility of these associations conveys a sense of permanence that nurtures the heart, that cripples one of the most insidious of human anxieties, the one that says, you do not belong here, you are unnecessary.

"Whenever I walk with a child, I think how much I have seen disappear in my own life. What will there be for this person when he is my age? If he senses something ineffable in the landscape, will I know enough to encourage it? -- to somehow show him that, yes, when people talk about violent death, spiritual exhileration, compassion, futility, final causes, they are drawing on forty thousand years of human meditation on this -- as we embrace Douglas firs, or stand by a river across whose undulating back we skip stones, or dig out a camas bulb, biting down into a taste so much wilder than last night's potatoes.

"The most moving look I ever saw from a child in the woods was on a mud bar by the footprints of heron. We were on our knees making handprints beside the footprints. You could feel the creek vibrating in the silt and sand. The sun beat down heavily on our hair. Our shoes were soaking wet. The look said: I did not know until now that I needed someone much older to confirm this, the feeling I have of life here. I can now grow older, knowing it need never be lost."

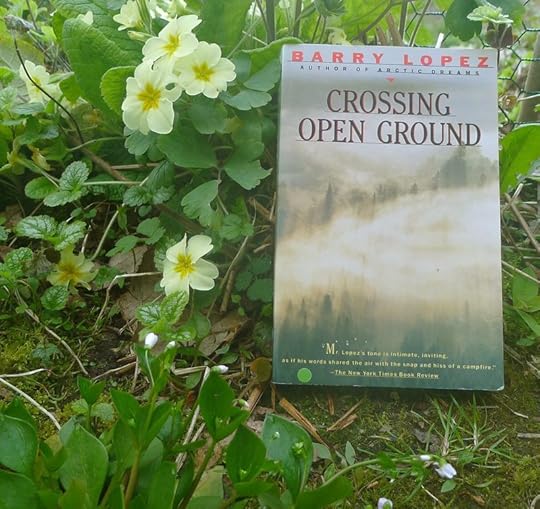

You can read this lovely, insightful essay in full in Lopez's essay collection Crossing Open Ground.

Related posts: children in the woods from a folkloric perspective: "Wild Children," and Cornelia Funke on the importance of wilderness in children's lives: "The Gift of Wonder."

Related posts: children in the woods from a folkloric perspective: "Wild Children," and Cornelia Funke on the importance of wilderness in children's lives: "The Gift of Wonder."

April 13, 2015

Wild Daffodils

Escape

When we get out of the glass bottles of our own ego,

and when we escape like squirrels turning in the

cages of our personality

and get into the forests again,

we shall shiver with cold and fright

but things will happen to us

so that we don't know ourselves.

Cold, unlying life will rush in,

and passion will make our bodies taut with power,

we shall stamp our feet with new power

and old things will fall down,

we shall laugh, and institutions will curl up like

burnt paper.

- D.H. Lawrence (1885-1930)

(from The Complete Poems of D.H. Lawrence,

Wordsworth Poetry Library, 1994)

"It seems that there is a virtue and a wisdom in keeping some things beyond our reach: that the protection of wilderness itself is imperative....We have touched, and are consuming, everything. The world is very old, and we are so new. I like the feeling of awe -- what the late writer Wallace Stegner called 'the birth of awe' -- in beholding wild country not reduced by man. I like to remember that it is wild country that gives rise to wild animals; and that the marvelous specificity of wild animals reminds us to wake up, to let our senses be inflamed by every scent and sound and sight and taste and touch of the world. I like to remember that we are not here forever, and not here alone, and that the respect with which we behold the wild world matters, if anything does.''

- Rick Bass (The Wild Marsh)

“In motivating people to love and defend the natural world, an ounce of hope is worth a ton of despair." - George Monbiot (Feral)

April 12, 2015

Tunes for a Monday Morning

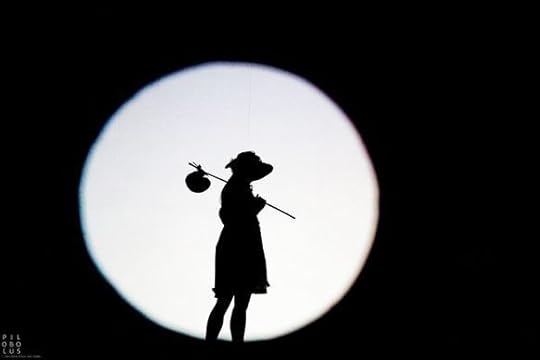

This morning's videos feature dance and movement of various kinds, beginning with "Transformation" from Shadowland, a show devised and performed by Pilobolus Dance Theatre, based in Connecticut. Created in collaboration with writer Steven Banks and composer David Poe, Shadowland is "a fusion of shadow theatre, illusion and dance using dynamic screens, where exotic creatures and beautiful images are magically conjured seemingly out of thin air."

Below, "Myth and Infrastructure" by Miwa Matreyek, an animator and performance artist from Los Angeles, with music by Anna Oxygen, Mirah, Caroline Lufkin, and Mileece. Matreyek describes her work as "an exploration of shadow and animation and themes of domestic spaces, dream-like vignettes, large and small cities, magical powers. I feel like it’s really based on me being a night owl and working in the middle of the night that feels like it could last forever -- creating little secrets and being inspired by what’s around me." It's a magical piece -- and becomes truly amazing about one third of the way in, so please stick with it.

Above, a poignant and strangely beautiful video for "Wandering Star” by the alt rock band Poliça (Minneapolis), directed by Eugene Lee Yang (Los Angeles), with choreography by Yemi AD (Czech Republic). In this twist on the Greek myth of Pygmalion, an elderly artist, alone in her studio, is surrounded by memories of past paintings and loved ones who come to life, rousing her from emotional slumber. (I particularly love the moment when she's embraced by the last of the single dancers, who I imagine to be a representation of her younger self.) "I’ve forever been fascinated by the fanciful prospect of art observing us," says Yang, "similar to the old adage, 'if these walls could talk'…or in this case, if these paintings could dance. I am a fervent believer that dance is the body’s way of communicating when the voice cannot."

Below, Sergei Polunin (Kherson, Ukraine) dances to "Take Me to Church" by Hozier (Wicklow, Ireland), in a gorgeous video directed by multi-media artist David LaChapelle (Los Angeles), with choreography by Jade Hale-Christofi (North London). Polunin was a principal dancer with the British Royal Ballet and now dances with the Stanislavsky and Nemirovich-Danchenko Moscow Academic Music Theatre and the Novosibirsk Opera and Ballet Theatre. Compared to the layered complexities of the other videos, the power of this one is in its simplicity: just light, mist, and the human body in motion.

April 9, 2015

Knowing the world as a gift

I'm reading a book now that several of you here have recommended, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teaching of Plants by Native American author and biologist Robin Wall Kimmerer, which is especially interesting in light of our current conversation on art and the marketplace.

Kimmerer references Lewis Hyde's important work on the distinction between market and gift economies (The Gift: How the Creative Spirit Transforms the World) -- but she comes to his ideas from an unusual direction, discussing the difference between these two ways of thinking from a botanical and ecological perspective rather than an artistic one. Strawberries are one example she gives of the gift economy operating in botanical form: the small, sweet wild strawberries she gathered freely from the fields when she was a child, a wild gift from the bounty of Mother Earth, as opposed to larger, less tasty strawberries farmed as monocrops, packaged in plastic, and shipped around the globe to be sold at supermarkets in every season.

"It's funny," she notes, "how the nature of an object -- let's say a strawberry or a pair of socks -- is changed by the way it has come into your hands, as a gift or as a commodity. The pair of wool socks that I buy at the store, red and gray striped, are warm and cozy. I might feel grateful for the sheep that made the wool and the worker who ran the knitting machine. I hope so. But I have no inherent obligation to those socks as a commodity, as private property. There is no bond beyond the lightly exchanged 'thank yous' with the clerk. I have paid money for them and our reciprocity ended the minute I handed her the money. The exchange ends once parity has been established, an equal exchange. They become my property. I don't write a thank-you note to JCPenny.

"But what if those very same socks, red and gray striped, were knitted by my grandmother and given to me as a gift? That changes everything. A gift creates ongoing relationship. I will write a thank-you note. I will take good care of them and if I am a very gracious granddaughter I'll wear them when she visits even if I don't like them. When it's her birthday, I will surely make her a gift in return. As Lewis Hyde notes, 'It is the cardinal difference between gift and commodity exchange that a gift establishes a feeling-bond between two people.' Wild strawberries fit the definition of a gift, but grocery store berries do not. It's the relationship between producer and consumer that changes everything."

"I'm a plant scientist and I want to be clear," Kimmerer continues, "but I'm also a poet and the world speaks to me in metaphor. When I speak of the gift of berries, I do not mean that Fragaria virginiana has been up all night making a present just for me, strategizing to find out exactly what I'd like on a summer morning. So far as we know, that does not happen, but as a scientist I am well aware of how little we do know. The plant has in fact been up all night assembling little packets of sugar and seeds and fragrance and color, because when it does so its evolutionary fitness is increased. When it is successful in enticing an animal such as me to disperse its fruit, its genes for making yumminess are passed on to the ensuing generations with a higher frequency than those of the plant whose berries were inferior. The berries made by the plant shape the behaviors of the dispersers and have adaptive consequences.

"What I mean of course is that our human relationship with strawberries is transformed by our choice of perspective. It is human perception that makes the world a gift. When we view the world this way, strawberries and humans alike are transformed. The relationship of gratitude and reciprocity thus developed can increase the evolutionary fitness of both plant and animal. A species and a culture that treat the natural world with respect and reciprocity will surely pass on genes to ensuing generations with a higher frequency than the people who destroy it. The stories we choose to shape our behaviors have adaptive consequences.

"In the old times, when people's lives were so directly tied to the land, it was easy to know the world as a gift. When fall came, the skies would darken with flocks of geese, honking 'Here we are.' It reminds the people of the [Potowatomi] Creation story, when the geese came to save Skywoman [the first human]. The people are hungry, winter is coming, and the geese fill the marshes with food. It is a gift and the people receive it with thanksgiving, love and respect.

"But when food does not come from a flock in the sky, when you don't feel the warm feathers cool in your hand and know that a life has been given for yours, when there is no gratitude in return -- that food may not satisfy. It may leave the spirit hungry while the belly is full. Something is broken when the food comes on a Styrofoam tray wrapped in slippery plastic, a carcass of a being whose only chance at life was a cramped cage. That is not a gift of life; that is a theft.

"How, in our modern world, can we find our way to understand the earth as a gift again, to make our relations with the world sacred again? I know we cannot all become hunter-gatherers -- the living world could not bear our weight -- but even in a market economy, can we behave 'as if' the living world were a gift?

"There are those who will try to sell the gifts...but refusal to participate is a moral choice. Water is a gift for all, not meant to be bought and sold. Don't buy it. When food has been wrenched from the earth, depleting the soil and poisoning our relatives in the name of higher yields, don't buy it.

"In material fact, wild strawberries belong only to themselves. The exchange relationships we choose determine whether we share them as a common gift or sell them as a private commodity. A great deal rests on that choice. For the greater part of human history, and in places in the world today, common resources were the rule. But some invented a different story, a social construct in which everything is a commodity to be bought and sold. The market economy story has spread like wildfire, with uneven results for human well-being and devastation for the natural world. But it is just one story we have told ourselves and we are free to tell another, to reclaim the old one.

"One of these stories sustains the living systems on which we depend. One of these stories opens the way to living in gratitude and amazement at the richness and generosity of the world. One of these stories asks us to bestow our gifts in kind, to celebrate our kinship with the world. We can choose. If all the world is a commodity, how poor we grow. When all the world is a gift in motion, how wealthy we become."

In the Mythic Arts field, we are all storytellers -- whether we work with words or paint or clay or sound or the movement of our bodies and the breath in our throats. And as storytellers, it behooves us think about the kinds of stories we're telling -- as well as about the ways we tell them, the ways we receive them, and the ways we pass them on to keep the gift in motion. There is no simple means of exempting our art from the strictures of the market economy while we live in a market-centered world, not if we depend on our work to pay the rent and put food on the table. But, as Kimmerer notes, our relationship to things, whether strawberries or stories, is transformed by our choice of perspective. When we come to "know the world as a gift," then we also come to know art as a gift, moving from hand to hand to hand, creating relationships "of gratitude and reciprocity."

And that, as Kimmerer says so sweetly and succinctly, changes everything.

The photographs here were taken at the Wallabrook, close to Scorhill stone circle. The large river stone with the hole in it, known as the Tolmen Stone, was believed to cure various ailments (arthritis and infertility in particular) in any who passed through it; it was also prescribed as a purification ritual for unfaithful wives. The single-slab clapper bridge nearby dates at least to the Elizabethan era (when we have the first record of it) and probably much earlier. The photograph of me, Howard, & Tilly is by Helen Mason; the rest are mine.

The photographs here were taken at the Wallabrook, close to Scorhill stone circle. The large river stone with the hole in it, known as the Tolmen Stone, was believed to cure various ailments (arthritis and infertility in particular) in any who passed through it; it was also prescribed as a purification ritual for unfaithful wives. The single-slab clapper bridge nearby dates at least to the Elizabethan era (when we have the first record of it) and probably much earlier. The photograph of me, Howard, & Tilly is by Helen Mason; the rest are mine.

April 8, 2015

Tension, balance, and walking in beauty

Howard & Tilly approaching the Scorhill stone circle

Howard & Tilly approaching the Scorhill stone circle

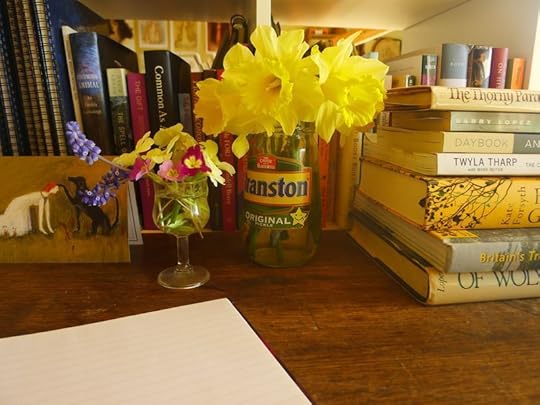

While thinking about our discussion of "art and the marketplace" last week, I came across the following passage from Daybook: The Journal of an Artist by the American abstract sculptor and color field artist Anne Truitt (1921-2004) -- who, despite major recognition in the form of museum shows and prestigious fellowships, still found it difficult to support herself and her three children through making art.

"I don't know why I seem to be able to make what people call art," she writes. "For many long years I struggled to learn how to do it, and I don't even know why I struggled. Then, in 1961, at the age of forty, it became clear to me that I was doing work I respected within my own strictest standards. Furthermore, I found this work respected by those whose understanding of art I valued. My first, instinctive reaction to this new situation was, if I'm an artist, being an artist isn't so fancy because it's just me. But now, thirteen years later, there seems more to it than that. It isn't 'just me.' A simplistic attitude toward the course of my life no longer serves.

"The 'just me' reaction was, I think, an instinctive disavowal of the social role of the artist. A life-saving disavowal. I refused, and still refuse, the inflated definition of artists as special people with special prerogatives and special excuses. If artists embrace this view of themselves, they necessarily have to attend to its perpetuation. They have to live it out. Their time and energy are consumed for social purposes. Artists then make decisions in terms of a role defined by others, falling into their power and serving to illustrate their theories. The Renaissance focused this sole attention on the artist's individuality, and the focus persists today in a curious form that on the one hand inflates artists' egoistic concept of themselves and on the other places them at the mercy of social forces on which they become dependent. Artists can suffer terribly in this dilemma.

"It is taxing to think out and then maintain a view of one's self that is realistic. The pressure to earn a living confronts a fickle public taste. Artists have to please whim to live on their art. They stand in fearful danger of looking to this taste to define their work decisions. Sometime during the course of their development, artists have to forge a character subtle enough to nourish and protect and foster the growth of the part of themselves that makes art, and at the same time practical enough to deal with the world pragmatically. They have to maintain a position between care of themselves and care of their work in the world, just as they have to sustain the delicate tension between intuition and sensory information.

"This leads to the uncomfortable conclusion that artists are, in this sense, special because they are intrinsically involved in a difficult balance not so blatantly precarious in other professions. The lawyer and the doctor practice their callings. The plumber and the carpenter know what they will be called upon to do. They do not have to spin their work out of themselves, discover its laws, and then present themselves turned inside out to the public gaze."

Indeed.

The photographs here were taken at Scorhill, a Bronze Age stone circle on the open moor past Chagford and Gidleigh. From its center, the sun balances and sets on the largest stone on Midsummer's Eve. Whatever else it may be, it's also a work of art, holding age, time, and stillness in an embrace of sky and granite.

As I go among the stones, I recall Gretel Ehrlich's words from The Solace of Open Spaces: "The truest art I would strive for in any work would be to give the page the same qualities as earth: weather would land on it harshly, light would elucidate the most difficult truths; wind would sweep away obtuse padding." I think Truitt would have agreed with this...as do I, though I make art that is, on the surface, quite different from hers.

When we turn to leave that timeless place, I whisper a prayer I learned long ago from the Navajo people of my own country: Beauty above us. Beauty below us. Beauty in the four directions. May we walk in beauty. May we walk in beauty.

All of us are artists as we create our lives, our families, our communities. All of us balance the conflicting demands of the marketplace and our deep, earth-centered selves. On Scorhill, the noise and flash of the consumer world disappears, and there is only this, granite and sky. There is only this, and it is enough.

May we walk in beauty. May we walk in beauty.

April 7, 2015

The Dog's Tale

The Dogs Tales are a series of posts in which Tilly has her say....

When I take my Person out walking in the woods it is my job to scout the path ahead, to lead us through the dark of the forest and bring us safely home again. With my good, furry ears and my keen, clever nose, I pick up on all the news of the forest: of foxes and badgers who have passed this way...squirrels rattling high above us in the trees...fine spiders' silk spun from leaf to leaf...coarse sheeps' wool caught in the bramble thorns...and the distinctive scent of the hillside's fairies: sweet, pungent, mushroomy and sour, all at once.

But what kind of fairies? Friends or foes? I sniff more closely, but I can't quite tell. Shy moss fairies, kindly root fairies, giggly fungi fairies: all these I do not mind. But the winged ones, buzzing through the air like overgrown bees, are tricksy, and they bite.

I follow their spoor through oak and ash, all the way to the forest boundary wall. The stink of fairies is overwhelming, and yet my Person walks on without concern. She's a gentle, absent-minded creature, unaware of danger. I must guard her closely.

Now fairies, as you know, love boundaries and borders; they love places that lie betwixt and between; and so the wall is riddled with fairy burrows and the evidence of fairy hands and fairy feet. I climb the wall, push my sensitive snout into the ivy, and find moss fairies curled in beds of lichen, green and plump and fast asleep. A root fairy, brown and wrinkled as a walnut, peers up with eyes the pale green of new leaves.

But this is not the danger I've been scenting. My hackles rise and I don't know why. My Person is drifting up the path behind me when I hear the buzz of fairy wings....

Suddenly a fairy swarm surrounds me, visible only as sparks of light, and I bark in warning: Stay back! Stay back! These are not the slow, soft creature of root and soil but the quick, sharp spirits of the forest canopy: shifty, capricious, and volatile. They bear no love for the Canine Tribe, and their fondness for mortals cannot be trusted.

My tail is pulled, my ears are tweaked, and sharp little fairy teeth nip my flanks. I growl and snap. I crunch. I swallow. I've eaten a fairy! I've eaten a fairy!

Uh oh. I've eaten a fairy. And my Person will not be pleased.

The swarm, taking fright, vanishes into the forest. The moss fairies snore. The root fairy smiles. My Person is safe now. She whistles and we walk on.

She never needs to know.

Spring on Dartmoor

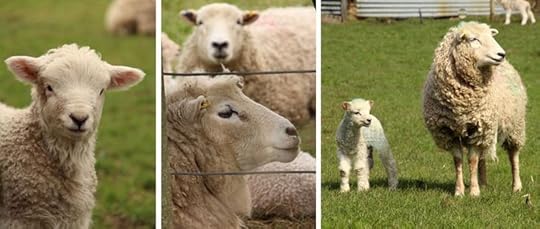

Here on Dartmoor, which is sheep country, we know that spring is truly here when the lambs are gamboling in the fields. These photographs of whiteface sheep and their lambs were taken by my friend Helen Mason on a Dartmoor farm on Easter morning.

When the Animals

by Gary Lawless

When the animals come to us

asking for our help

will we know what they are saying?

When the plants speak to us

in their delicate, beautiful language

will we be able to answer them?

When the planet herself

sings to us in our dreams,

will we be able to wake ourselves and act?

"When Animals" by Gary Lawless was published in First Sight of Land (Blackberry Books, 1990); "Nass River" by Robert MacLean (in the picture captions) was published in In a Canvas Tent (Sono Nis, 1984); all rights reserved by the authors. Helen Mason's photographs have appeared previous on Myth and Moor here and here.

"When Animals" by Gary Lawless was published in First Sight of Land (Blackberry Books, 1990); "Nass River" by Robert MacLean (in the picture captions) was published in In a Canvas Tent (Sono Nis, 1984); all rights reserved by the authors. Helen Mason's photographs have appeared previous on Myth and Moor here and here.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers