Terri Windling's Blog, page 139

April 27, 2015

Living the mythic life

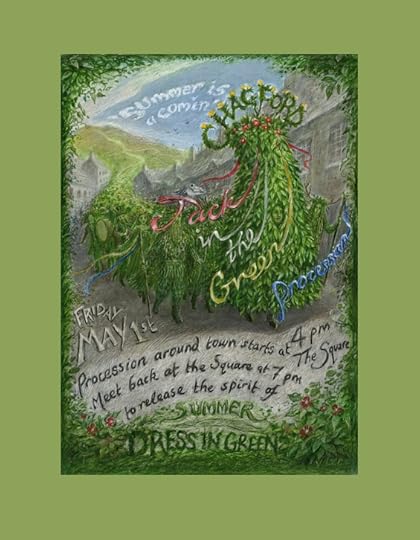

If you're anywhere near Dartmoor on Friday, come help us celebrate May Day in Chagford with a traditional "Jack in the Green" procession, with music by Andy Letcher and friends. Also, if you're an early riser, May Day starts with a sunrise dance up at Haytor by the spooky and wonderful Beltane Border Morris troupe.

Beltane celebrations are making a come-back in Britain, and for those of us for whom myth and folklore are the staff of life, this is good news indeed. The art in the beautiful poster above is by Virginia Lee.

April 26, 2015

Tunes & Words for a Monday Morning

It's been another week of news that pushes us daily closer to despair, from the tragedies in Nepal and off the Italian coast to the horrific scale of police violence against nonwhite Americans, while political campaigners in both the UK and US studiously avoiding speaking civilly, seriously, and honestly of anything that truly matters. So I am pushing back against hopelessness by sharing some of my favorite videos from this year's Bioneers conference -- words rather than music today -- although also a little music to get us started from the conference's opening ceremony. Bioneers, based in New Mexico, is a nonprofit organization founded by Nina Simons and Kenny Ausubel, bringing  scientists, scholars, artists and activists together to "highlight breakthrough solutions for restoring people and planet."

scientists, scholars, artists and activists together to "highlight breakthrough solutions for restoring people and planet."

As an American living abroad, I find it both sad and painful that my country is primarily known outside its borders through facile Hollywood representations, and for the darker, nuttier, Fox-News-amplified side of American life (and foreign policy) -- whereas those of us who have lived there know that the other side of America is equally strong: the land of civil rights, gay rights, passionate feminism, proud union men and women on the picket lines, and a bred-in-the-bone tradition of volunteerism; a land of organic farms and alternative communities and tireless activists on behalf of the North American wild; a land of kind, open-hearted, and generous people from a dizzying number of ethnic backgrounds and cultural traditions. The three speakers here come from my America, not the media's: the leftist, progressive American tradition that formed me; the beautiful, vast, diverse, and deeply complicated land that I still love, warts and all.

Above: Opening music and a few wise words from Native American flutist R. Carlos Nakai. He's from Tucson, and his music never fails to make me homesick for the desert.

Below: Writer, educator, and activist Terry Tempest Williams, from Utah, discuses "A Love That is Wild." She says, "Finding beauty in the broken world is creating beauty in the world we find," and this is so very true.

Above, Robin Wall Kimmerer, biologist and author of Braiding Sweetgrass, discusses "Mishkos Kenomagwen: The Teachings of Grass." Kimmerer is the director of the Center for Native Peoples and the Environment in Syracuse, New York.

Below, educator, activist, and author John A. Powell discusses the need for "Beloved Community." Powell is the head of the Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society at the University of California, Berkeley.

"If we are going to address these issues around climate change, food, health, each other," says Powell, "we have to not only think about how we're related, we have to structure our societies, we have structure our policies, we have to tell our stories, we have to engage a practice that acknowledges our deep connection and our relationships with each other."

And that's where we come in, as Mythic Artists: telling stories. For the land and for each other. Stay strong.

Art above : Sonoran Desert drawings by Charles Vess

April 24, 2015

The Windigo

I don't often post on a Saturday, but I wanted to end the week with one last passage from Robin Wall Kimmerer's Braiding Sweetgrass -- this time dipping into the myth of the Windigo. I was planning to illustrate this post with Windigo illustrations, but I found them all too scary! So instead: the Devon hills, misty and mysterious in the early morning light, and a furry black protector to scare off any monsters in lurking in the bracken.

"The Windigo is the legendary monster of our Anishinaabe people," writes Kimmerer, "the villain of a tale told on freezing nights in the north woods. You can feel it lurking behind you, a being in the shape of an outsized man, ten feet tall, with frost-white hair hanging from its shaking body. With arms like tree trunks, feet as big as snow-shoes, it travels easily through the blizzards of the hungry time, stalking us. The hideous stench of its carrion breath poisons the clean scent of snow as it pants behind us. Yellow fangs hang from its mouth that is raw where it has chewed off its lips from hunger. Most telling of all, its heart is made of ice....This monster is no bear or howling wolf, no natural beast. Windigos are not born, they are made. The Windigo is a human being who has become a cannibal monster. Its bite will transform victims into cannibals too....It is said that the Windigo will never enter the spirit world but will suffer the eternal pain of need, its essence a hunger that will never be sated. The more a Windigo eats, the more ravenous it becomes. Consumed by consumption, it lays waste to humankind."

"Traditional upbringing was designed to strengthen self-discipline, to build resistance against the insidious germ of taking too much. The old teachings recognized that Windigo nature is in each of us, so the monster was created in stories, that we might learn why we should recoil from the greedy part of ourselves. This is why Anishinaabe elders like Stewart King remind us always to acknowledge the two faces -- the light and the dark side of life -- in order to understand ourselves. See the dark, recognize its power, but do not feed it.

"The beast has been called an evil spirit that devours mankind. The very word, Windigo, according to Ojibwe scholar Basil Johnston, can be derived from roots meaning 'fat excess' or 'thinking only of oneself.' Writer Steve Pitt states 'a Windigo was a human whose selfishness has overpowered their self-control to the point where satisfaction is no longer possible.'

"No matter what they call it, Johnston and many other scholars point to the current epidemic of self-destructive practices -- addiction to alcohol, drugs, gambling, technology, and more -- as a sign than Windigo is alive and well. In Ojibwe ethics, Pitt says, 'any overindulgent habit is self-destructive, and self-destruction is Windigo.' And just as Windigo's bite is infectious, we know all too well that self-destruction drags along many more victims -- in our human families as well as in the more-than-human world.

"The native habitat of the Windigo is the north woods, but the range has expanded in the last few centuries. As Johnston suggests, multinational corporations have spawned a new breed of Windigo that insatiably devours the earth's resources 'not for need but for greed.' The footprints are all around us if you know what to look for."

"We are all complicit," notes Kimmerer. "We've allowed the 'market' to define what we value so that the redefined common good seems to depend on profligate lifestyles that enrich the sellers while impoverishing the soul and the earth. Cautionary Windigo tales arose in a commons-based society where sharing was essential to survival and greed in any individual a danger to the whole. In the old times, individuals who endangered the community by taking too much for themselves were first counseled, then ostracized, and if the greed continued, they were eventually banished. The Windigo myth may have arisen from the remembrance of the banished, doomed to wander hungry and alone, wreaking vengence on those who spurned them. It is a terrible punishment to be banished from the web of reciprocity, with no one to share with you and no one for you to care for.

"I remember walking a street in Manhattan, where the warm light of a lavish home spilled out onto the sidewalk on a man picking through the garbage for his dinner. Maybe we've all been banished to lonely corners by our obsession with private property. We've accepted banishment even from ourselves when we spend our beautiful, singular lives on making more money, to buy more things that will feed but never satisfy. It is the Windigo way that tricks us into believing that belongings will fill our hunger, when it is belonging that we crave. On a grander scale, too, we seem to be living in an era of Windigo economics of fabricated demand and compulsive overconsumption. What Native peoples once sought to rein in, we are now asked to unleash in a systematic policy of sanctioned greed.

"The fear for me is far greater than just acknowledging the Windigo within. The fear for me is that the world has been turned inside out, the dark side made to seem light. Indulgent self-interest that our people once held to be monstrous is now celebrated as success. We are asked to admire what our people once viewed as unforgiveable. The consumption-driven mind-set masquerades as 'quality of life' but eats us from within. It is as if we've been invited to a feast, but the table is laid with food that nourishes only emptiness, the black hole of the stomach that never fills. We have unleashed a monster."

Later in her book, Kimmerer discusses how to defeat the Windigo in our midst through the "economy of the commons, wherein resources fundamental to our well-being, like water and land and forests, are commonly held rather than commodified. Properly managed, the commons approach maintains abundance, not scarcity. These contemporary economic alternatives strongly echo the indigenous world view in which the earth exists not as private property, but as a commons to be tended with respect and reciprocity for the benefit of all.

"And yet, while creating an alternative to destructive economic structures is imperative, it is not enough. It is not just changes in policy that we need, but also changes to the heart. Scarcity and plenty are as much qualities of the mind and spirit as they are of the economy. Gratitude plants the seed for abundance.

"Each of us comes from people who were once indigenous. We can reclaim our membership in the cultures of gratitude that formed our old relationship with the living earth. Gratitude is a powerful antidote to Windigo psychosis. A deep awareness of the gifts of the earth and of each other is medicine. The practice of gratitude lets us hear the badgering of marketers as the stomach grumblings of a Windigo. It celebrates cultures of regenerative reciprocity, where wealth is understood to be having enough to share and riches are counted in mutual beneficial relationships. Besides, it makes us happy."

Indeed.

April 23, 2015

A democracy of species

Here's another lovely passage from Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer, weaving together several of the themes that we've been discussing these last few weeks: gift vs. market economies, inter-species relationships, living and working in gratitude, and how to "re-wild" our children in an increasingly urban world.

"Our old farm is within the ancestral homelands of the Onondaga Nation," Kimmerer writes, "and their reserve lies a few ridges to the west of my hilltop. There, just like on my side of the ridge, school buses discharge a herd of kids who run even after the bus monitors bark 'Walk!' But at Onondaga, the flag flying outside the entrance [of the school] is purple and white, depicting the Hiawatha wampum belt, the symbol of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy....Here the school week begins and ends not with the Pledge of Allegiance, but with the Thanksgiving Address, a river of words as old as the people themselves, known more accurately in the Onondaga language as the Words That Come Before All Else. This ancient order of protocol sets gratitude as the highest priority. The gratitude is directed straight to the ones who share their gifts with the world.

"All classes stand together in the atrium, and one grade each week has responsibility for the oratory. Together, in a language older than English, they begin the recitation. It is said that the people were instructed to stand and offer these words whenever they gathered, no matter how many or how few, before anything else was done. In this ritual, their teachers remind them that every day, 'beginning with where our feet touch the earth, we send thanks and greetings to all members of the natural world.' "

The wording of the Thanksgiving Address varies with the speaker, but you can read well known version by John Stokes and Kanawahientun here.

"The Address is, by its very nature of greeting to all who sustain us, long," Kimmerer continues. "But it can be done in abbreviated form or in long and loving detail. At the school, it is tailored to the language skills of the children speaking it.

"Part of its power surely rests in the length of time it takes to send greetings and thanks to so many. The listeners reciprocate the gift of the speaker's words with their attention, and by putting their minds into the place where gathered minds meet. You could be passive and just let the words flow by, but each call asks for the response: 'Now our minds are one.' You have to concentrate; you have to give yourself to the listening. It takes effort, especially in a time when we are accustomed to sound bites and immediate gratification."

"Imagine raising children in a culture in which gratitude is the first priority. Freida Jacques works at the Onondaga Nation School. She is a clan-mother, the school-community liaison, and a generous teacher. She explains to me that the Thanksgiving Address embodies the Onondaga relationship to the world. Each part of Creation is thanked in turn for fulfilling its Creator-given duty to others. 'It reminds you every day that you have enough,' she says. 'More than enough. Everything needed to sustain life is already here. When we do this, every day, it leads us to an outlook of contentment and respect for all of Creation.'

"You can't listen to the Thanksgiving Address without feeling wealthy. And, while expressing gratitude seems innocent enough, it is a revolutionary idea. In a consumer society, contentment is a radical proposition. Recognizing abundance rather than scarcity undermines an economy that thrives by creating unmet desires. Gratitude cultivates an ethic of fullness, but the economy needs emptiness. The Thanksgiving Address reminds you that you already have everything you need. Gratitude doesn't send you out shopping to find satisfaction; it comes as a gift rather than a commodity, subverting the foundation of the whole economy. That's good medicine for land and people alike."

"As Frieda says, 'The Thanksgiving Address is a reminder we cannot hear too often, that we human beings are not in charge of the world, but are subject to the same forces as the rest of life.'

"For me, the cumulative impact of the Pledge of Allegiance, from my time as a schoolgirl to my adulthood, was the cultivation of cynicism and a sense of the nation's hypocrisy -- not the pride it was mean to instill. As I grew to understand the gifts of the earth, I couldn't understand how 'love of country' could omit recognition of the actual country itself. The only promise it requires is to a flag. What of the promises to each other and to the land?

"What would it be like to be raised on gratitude, to speak to the natural world as a member of a democracy of species, to raise a pledge of interdependence? No declarations of political loyalty are required, just a response to a repeated question, 'Can we agree to be grateful for all that is given?' In the Thanksgiving Address, I hear respect toward all our nonhuman relatives, not one political entity, but all of life."

"Cultures of gratitude must also be cultures of reciprocity. Each person, human or no, is bound to every other in a reciprocal relationship. Just as all beings have a duty to me, I have a duty to them. If an animal gives his life to feed me, I am in turn bound to support its life. If I receive a stream's gift of pure water, then I am responsible for returning the gift in kind. An integral part of a human's education is to know those duties and how to perform them.

"The Thanksgiving Address reminds us that duties and gifts are two sides of the same coin. Eagles were given the gift of far sight, so it is their duty to watch over us. Rain fulfills its duty as it falls, because it was given the gift of sustaining life. What is the duty of humans? If gifts and responsibilities are one, then asking, 'What is our responsibility?' is the same as asking 'What is our gift?' It is said that only humans have the capacity of gratitude. That is one of our gifts."

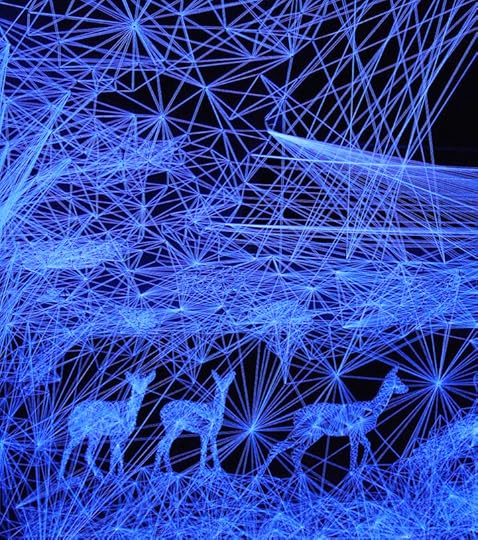

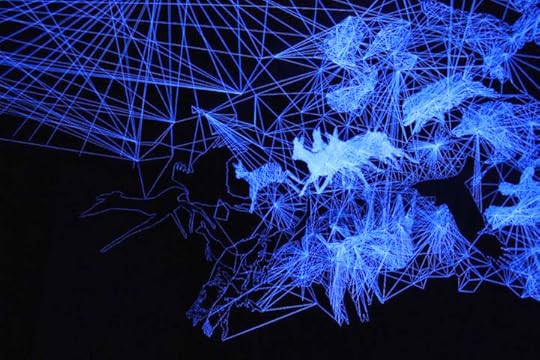

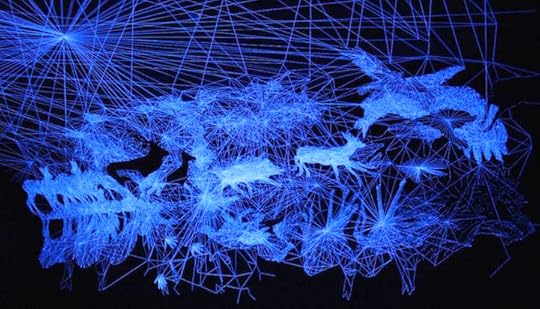

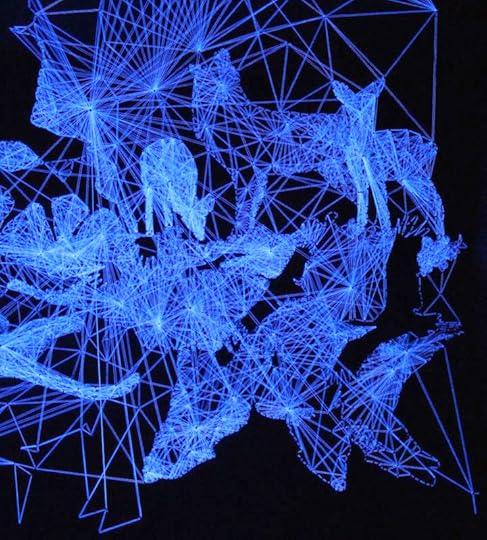

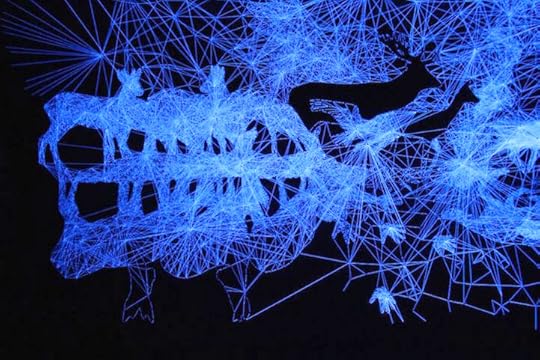

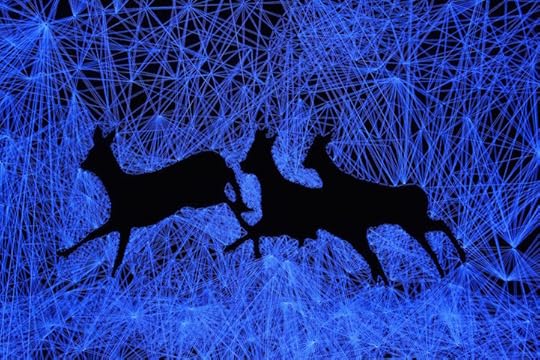

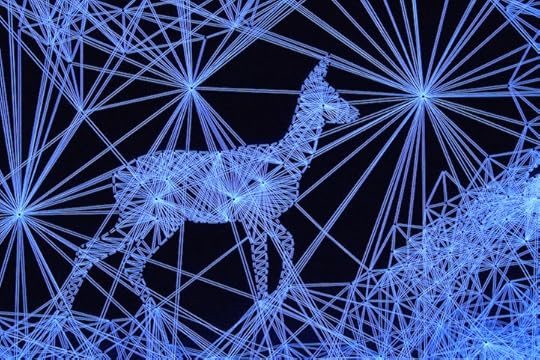

The luminous works of art picture here are from the Stellar Cave series by Julien Salaud, an installation artist from Orléans, France. Each piece, explains Jenny Zhang (on My Modern Met), "is made of cotton thread that is coated in ultraviolet paint, woven into the shapes of stunning creatures, and held down with thousands of nails to form a glowing tapestry that transforms the room into an intergalactic grotto."

Many thanks to Gwenda Bond and Ellen Kushner for introducing me to Julien Salaud's stunning work.

Many thanks to Gwenda Bond and Ellen Kushner for introducing me to Julien Salaud's stunning work.

Bunny Girls and other little people & critters still looking for loving homes

Greta Ward still has some prints of mine left after her big Open Studio sale (thank you and bless you, Greta!), and will be selling them from her beautiful website until the remaining stock runs out. Can you give a little person a home?

While you're on her site, please have a look at Greta's gorgeous work as well; and if your pennies go in that direction instead, I'll be equally pleased.

Another way to buy my prints at moment is via the "Con or Bust" auction, which runs until May 3rd. I've donated four prints, and if you pick them up here, you'll be supporting diversity in the speculative fiction field.

"Ideas are like rabbits. You get a couple and learn how to handle them, and pretty soon you have a dozen." - John Steinbeck

Homemade ceremonies

In Braiding Sweetgrass, Native American author and biologist Robin Wall Kimmerer (of the Potowatomi people) explains how her family was severed from their traditional culture when her grandfather, like so many children of his generation, was taken from home by the U.S. government and sent to the Carlisle Indian School to be "civilized" (a truly shameful chapter of my country's history). It was not until many years later that his descendants reclaimed their language and heritage. Against this painful background, Kimmerer writes movingly of her father's morning ritual when the family camped on the slopes of Tahawus each summer (the Algonquin name for Mount Marcy in the Adirondaks):

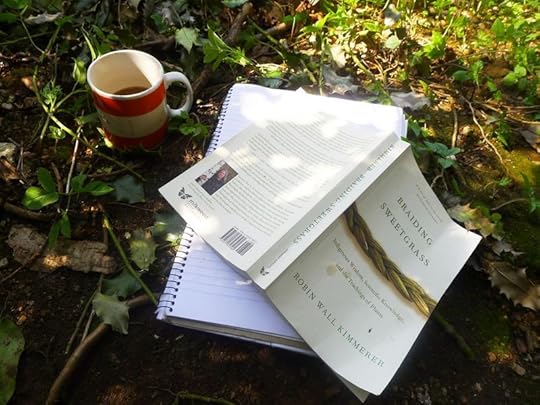

"When he lifts the coffee pot from the stove the morning bustle stops; we know without being told that it's time to pay attention. He stands at the edge of camp with the coffeepot in his hands, holding the top in place with a folded pot holder. He pours coffee on the ground in a thick brown stream. The sunlight catches the flow, striping it amber and brown and black as it falls to the earth and steams in the cool morning air. With his face to the morning sun, he pours and speaks into the stillness, 'Here's to the gods of Tahawus.' "

"I was pretty sure no other family I knew began their day like this," she continues, "but I never questioned the source of those words and my father never explained. They were just part of our life among the lakes. But their rhythm made me feel at home and the ceremony drew a circle around our family. By those words we said, 'Here we are,' and I imagined that the land heard us -- murmured to itself, 'Ohh, here are the ones who know how to say thank you.' "

"Sometimes my father would name the gods of Forked Lake or South Pond or Brandy Brook Flow, wherever our tents were settled for the night. I came to know each place was inspirited, was home to others before we arrived and long after we left. As he called out the names and offered a gift, the first coffee, he quietly taught us the respect we owed these other beings and how to show our thanks for summer mornings.

"I knew that in the long-ago our people raised their thanks in morning songs, in prayer, in the offering of sacred tobacco. But at that time in our family history we didn't have sacred tobacco and we didn't know the songs -- they'd been taken away from my grandfather at the doors of the boarding school. But history moves in a circle and here we were, the next generation, back to the loon-filled lakes of our ancestors, back to the canoes....

"In the same way that the flow of coffee down the rock opened the leaves of the moss, ceremony brought the quiescent back to life, opened my mind and heart to what I knew, but had forgotten. The words and the coffee called us to remember that these woods and lakes were a gift. Ceremonies large and small have the power to focus attention to a way of living awake in the world. The visible became invisible, merging with the soil. It may have been a secondhand ceremony, but...I recognized that the earth drank it up as if it were right. The land knows you, even when you are lost.

"A people's story moves along like a canoe caught in the current, being carried closer and closer to where we had begun. As I grew up, my family found again the tribal connections that had been frayed, but never broken, by history. We found the people who knew our true names. And when I first heard in Oklahoma the sending of thanks to the four directions at the sunrise lodge -- the offering in the old language of the sacred tobacco -- I heard it as if in my father's voice. The language was different but the heart was the same.

"Ours was a solitary ceremony, but fed from the same bond with the land, founded on respect and gratitude. Now the circle drawn around us is bigger, encompassing a whole people to which we again belong. But still the offering says, 'Here we are,' and still I hear at the end of the words the land murmuring to itself, 'Ohh, here are the ones who know how to say thank you.' Today my father can speak his prayers in our language. But it was 'Here's to the gods of Tahawus' that came first, in the voice I will always hear. It was in the presence of ancient ceremonies that I understood that our coffee offering was not secondhand, it was ours."

The power of ceremony, writes Kimmerer, is that "it marries the mundane to the sacred. The water turns to wine, the coffee to a prayer. The material and the spiritual mingle like grounds mixed with humus, transformed like steam rising from a mug into the morning mist. What else can you offer the earth, which has everything? What else can you give but something of yourself? A homemade ceremony, ceremony that makes a home."

I've written before about my own morning rituals, which are solitary ones except for Tilly's presence, and also about how much I prefer that solitude to be undisturbed in the enchanted liminal space between waking up and creative work. We can draw parallels between the rituals of beginning / rituals of approach we employ to facilitate creative work and the morning ritual Kimmerer describes. Ceremony, meditation, creative routines and practices designed to ease us into work, these are all means of acknowledging the transition from one state into another: from sleep into a brand new day, from morning chores and mundane concerns to the focused state of creativity and inspiration.

But there's also an important difference here -- which, I fear, often gets lost when First Nation ceremonies are too-casually adapted by non-native peoples. While the coffee ritual may indeed have helped Kimmerer's father to feel more meditative, centered, and ready to start his day, this therapeutic aspect of the ceremony is not its purpose or focus. Rather, it is an act of gratitude, an acknowledgement of the larger world of which we humans are just one part. There is no ego in the ritual, no self-aggrandizing, no "look at me, look how spiritual I am" -- just the simple, humble act of man offering a humble gift to creation.

In my own morning rituals, gratitude to the land, to our animal neighbors, to the vast nonhuman world plays a crucial part. It is why I write and why I paint: sheer gratitude for being alive, even on -- perhaps especially on -- those mornings when, because of poor health or other difficulties, life feels most burdensome. I want to create not from a place of ego and self-aggrandizement but as a means of gifting stories to the beautiful land that feeds and clothes and houses and sustains me; and to give, as Pablo Neruda once said, "something resiny, earthlike and fragrant in exchange for the gift of human brotherhood."

Some days I succeed, and some days I don't. But each morning I wake up, climb the hill with Tilly, pour steaming coffee from a silver thermos as birdsong greets the sun, and I try again. And again. And again. On the hill, I remember that my place in the world is very small. And very precious. And I'm grateful for it all.

April 21, 2015

Recommended Reading:

I haven't done a reading round-up in a while, so here are my magpie gleanings from hither and yon:

* Jay Griffith's "Hearth: A Thesaurus on Home," a thoroughly gorgeous four-part mediation on the concept of home, highly recommended. (Stay Where You Are)

* Terry Tempest Williams reflects on "The Glorious Indifference of Nature," and also discusses the subject with Jennifer Sahn. (Orion Magazine)

* Jane Shilling's "How Pastoral Writing is Being Redefined" looks at new nature writing in England by Jay Griffiths, George Monbiot, Sylvain Tesson, and Philip Hoare. (The New Statesman)

* Robert Macfarlane explores "The Eeriness of the English Countryside" as expressed by writers and artists from M.R. James to Alan Garner. (The Guardian)

* Jack Zipes explains "How the Grimms Brothers Saved the Fairy Tale." (Humanities)

* A. S. Byatt reviews The Story of Alice: Lewis Carroll and the Secret History of Wonderland by Robert Douglas-Fairhurst. (The Spectator)

* Stephen March contends that genre fiction has become more important than literary fiction. (Esquire Magazine)

* Sherwood Smith analyzes the differences between Jane Austen's fiction and Georgette Heyer's. (Book View Cafe)

* Sherwood Smith analyzes the differences between Jane Austen's fiction and Georgette Heyer's. (Book View Cafe)

* Maev Kennedy on the discovery of Fanny Cornforth's lost grave. (The Guardian)

* Maria Popova spotlights Thinking with Animals: New Perspectives on Anthropomorphism by Lorraine Daston and Gregg Mitman. (Brain Pickings)

* For National Poetry Month, ten poems about animals, many of them mythic in nature:

"The Strange People" by Louise Erdrich, "Fox" by Adrienne Rich, "The Animals in That Country" by Margaret Atwood, "Toad Dreams" by Marge Piercy, "Birthdreams" by Laurie Kutchins,"Deer Dance" by Linda Hogan, "The Girl Who Married a Reindeer" by by Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin, "The Bear's Daughter" by Theodora Goss, "A Poem About the Hounds and the Hares" by Lisel Mueller, and "Mongrel Heart" by David Baker.

* And one audio piece: Elizabeth Knox delivers a knock-out inaugural Margaret Mahy lecture, podcast by Radio New Zealand. I hope you all know The Vintner's Luck, The Angel's Cut, Black Oxen, The Dreamhunter's Duet and Knox's other stunning novels; and the late Margaret Mahy's too for that matter.

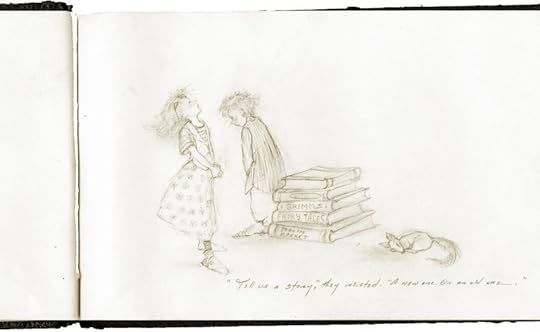

The Library of the Forest

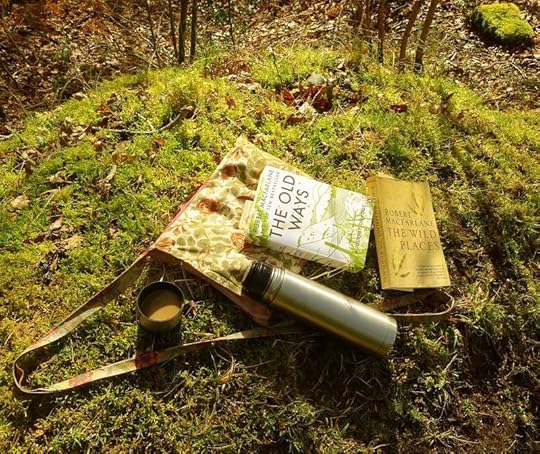

From The Old Ways by Robert Macfarlane:

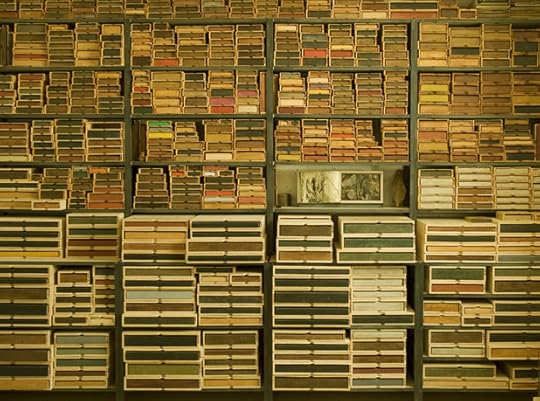

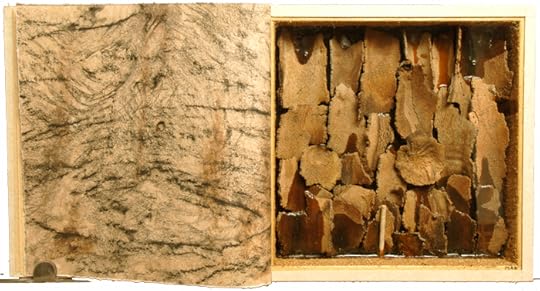

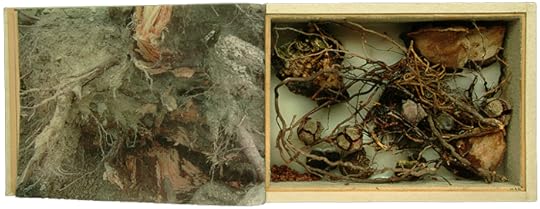

"The library of Miquel Angel Blanco [in Madrid, Spain] is no ordinary library. It is not arranged according to topic and subject, nor is it navigated by means of the Dewey Decimal system. It's full name is the Library of the Forest, La Biblioteca del Bosque. It has so far been a quarter of a century in the making, and at last count it consisted of more than 1,100 books -- though its books are not only books, but also reliquaries. Each book records a journey made by walking, and each contains natural objects and substances gathered along that particular path: seaweed, snakeskin, mica flakes, crystals of quartz, sea beans, lightning-scorched pine timber, the wing of a grey partridge, pillows of moss, worked flint, cubes of pyrite, pollen, resin, acorn cups, the leaves of holm oak, beech, elm. Over the many years of its making, the library has increased in volume and spread in space. It now occupies the entire ground floor and basement of an apartment building in the north of Madrid. Entering the rooms in which it exists feels like stepping into the pages of Jorge Luis Borges story: 'The Library of Babel' crossed with 'The Garden of the Forking Paths,' perhaps....

"The Library of the Forest owes its existence to storm and snow. Between 30 December 1984 and New Year's Day 1985 a severe winter gale struck the Guadarrama Mountains, the sierra of granite and gneiss that slashes north-east to south-west across the high plains of Castille, separating Madrid (to the south) from Segovia (to the north). Thousands of Scots pines that forest the Guadarrama were toppled. For those tempetuous days, Miguel was trapped in his small house in Fuenfría, a southern Guadarraman valley. When at last the storm stopped and the thaw came, he walked up into the valley, following a familiar path but encountering a new world: fifteen-foot-deep drifts of snow, craters and root boles where trees had been felled, sudden clearings in the forest. As he walked, he gathered objects he found along the way: pine branches, resin, cones, curls of bark, a black draughts piece and a white draughts piece. When he returned home to his house he placed the gathered items in a small pine box, lidded the box with glass, sealed the glazing with tar, bound pages to the box with tape and gave the whole a cover of card-backed linen.

"In this way the first book of the library was made. Miguel called that original book-box Deshielo, 'Thaw,' and it became the source from which a stream of works began to flow.

"His manufacturing method is unchanged in its fundamentals. All his book-boxes contain objects he has collected while walking; the results of chance encounters or conscious quests. The found objects are held in place within each box by wire and thread, or pressed into fixed beds of soil, resin, paraffin or wax. Thus mutely arranged, each book-box symbolically records a walk made, a path followed, a foot-journey and its encounters. And the library exists as a multidimensional atlas -- an ever-growing root-map, and a peculiar chronicle of a journey without respite."

"Each of my books records an actual journey but also a camino interior, an interior path."

- Miguel Angel Blanco

Photographs: Early morning coffee break in the Devon hills; and Blanco's Library of the Forest.

Photographs: Early morning coffee break in the Devon hills; and Blanco's Library of the Forest.

April 20, 2015

The "Con or Bust" auction

CON OR BUST

The “Con or Bust” folks are running their annual auction to raise money to help readers, writers, and artists of color attend conferences and conventions in the speculative fiction field. I’ve donated this set of four prints, so if you care to bid on them you’d be contributing to a very good cause, supporting diversity in sff. Or if bidding is beyond your budget right now, you can still help by spreading the word about the Con or Bust auction and the Con or Bust program.

There are lots of other good things (books, art, crafts, etc.) up for auction too – and there’s still plenty of time to donate items yourself. Bidding is open until Sunday, May 3rd.

* Go here for the Con or Bust auction.

* Go here for information on my prints in the auction.

* Go here for information on how to donate items to the auction yourself.

April 19, 2015

Tunes for a Monday Morning

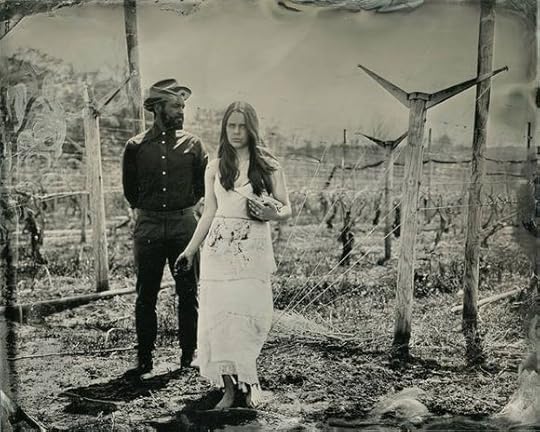

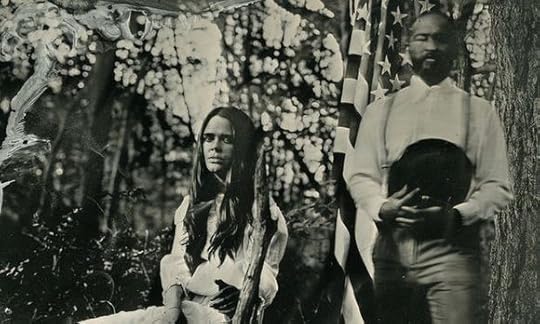

Today, the music of Jus Post Bellum (translation: "justice after war"), an American alt-folk band I've only just started listening too thanks to a recent article in The New Yorker. Based in Brooklyn, New York, the group consists of singer/songwriters Geoffrey Wilson and Hannah Jensen (originally from Minnesota), bassist Daniel Bieber, and drummer Zach Dunham. They've released two albums of "story songs" inspired by dark moments of American history: Devil Winter (2012) and Oh July (2013).

Above: "Abe and Johnny," a song about Abraham Lincoln's assassination by John Wilkes Booth.

Below: "Sharp Was Bending the River," about the Civil War.

Above: "Gimme That Gun" (audio only), another one inspired by the Civil War era.

Below: a beautifully simple version of their song "Measure of a Man," performed by Wilson and Jensen alone. The song starts 25 seconds in, if you want to avoid the annoying A-Sides series intro.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers