Terri Windling's Blog, page 135

June 12, 2015

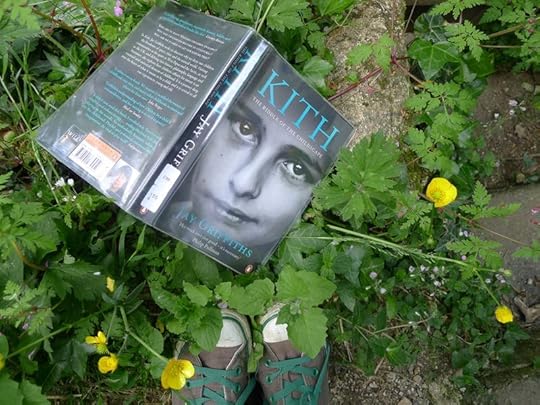

The enclosure of childhood

This week, we've been talking about the ways that childhood is becoming more and more detached from the natural world, and what that might mean for those of us creating fiction and art born out of myth and the mythic landscape. To further the discussion, here's another salient passage from Jay Griffith's fine study of childhood, Kith: The Riddle of the Childscape:

"If there is one word that sums up the treatment of children today, it is enclosure," she writes (alluding to the Enclosure Acts which privatized huge swaths of British common land from the 17th century onward). "Today's  children are enclosed in school and home, enclosed in cars to shuttle between them, enclosed by fear, by surveillance and poverty and enclosed in rigid schedules of time. These enclosures compound each other and make children bitterly unhappy. In 2011, UNICEF asked children what they needed to be happy and the top things were time (particularly with families), friendships and, yearningly, 'outdoors.' Studies show that when children are allowed unstructured play in nature, their sense of freedom, independence, and inner strength all thrive, and children surrounded by nature are not only less stressed but also bounce back from stressful events more readily.

children are enclosed in school and home, enclosed in cars to shuttle between them, enclosed by fear, by surveillance and poverty and enclosed in rigid schedules of time. These enclosures compound each other and make children bitterly unhappy. In 2011, UNICEF asked children what they needed to be happy and the top things were time (particularly with families), friendships and, yearningly, 'outdoors.' Studies show that when children are allowed unstructured play in nature, their sense of freedom, independence, and inner strength all thrive, and children surrounded by nature are not only less stressed but also bounce back from stressful events more readily.

"But there has been a steady reduction in available open spaces for children to play. In the USA, the home turf of children shrank by ninety per cent beween 1970 and 1990. Similarly, in Britain, children have one ninth of the roaming room they had in earlier generations. Childhood is losing its commons. There has also been a reduction in available time, with less than ten per cent of children now spending time playing in woodlands, countryside or heaths, compared to forty per cent who did so a generation ago.

"Although they are themselves part of nature, children are removed from the world of moss and trees, of fur and paw. Children don't need to live in the countryside to have access to nature, and most city children, left to their own devices, can find a bare minimum of what they need in urban parks and gardens, even on the streets. But play is enclosed indoors while outside signs bark at children like Alsatian guard dogs: NO CYCLING. NO SKATEBOARDS. NO BALL GAMES. NO SWIMMING. NO TRESPASSING.

"My later childhood was hollowed by cold and poverty," Griffiths continues, "and that depression which sets up snares in the young psyche, trapping it for life. My early childhood, though, was far happier, in large part because my brothers and I were part of the last generation which was not under house arrest. It was not a rural childhood, but we had a garden, and a few streets away a river ran by the side of the 'wreck,' as we called the recreation ground. It was a wreck. Scruffy. Ignored. Ours. Five minutes' walk away was a park. Two hours away were grandparents who lived by the sea. All the games we had fitted into a bench trunk about six foot by two. We were rich in library books, bicycles and outdoors.

"Outdoors, we could do what we liked. Throwing sticky seeds at each other, gurgling water or chucking it all over someone. Indoors, obviously not, for indoors was where complexity began: 'mine' and 'yours' and the different rules of time. Outdoors was a commons of space and a commons of time, the undivided hours until dark. Outdoors could comprehend all our moods: thoughtful, playful, withdrawn or rampaging. Outdoors was the place for voices other than human."

"Along with everyone else I knew, from the first day of school we walked there. I went with my brothers and friends, a little ragged string of us, taking short cuts that weren't, chatting nonsense, swapping things, eating sweets, making dares, sticking chewing gum on the walls, doing deals, showing off, doing silly walks, shuffling, holding hands, telling secrets, getting the giggles. It was a crucial part of the whole business of childhood. We learned our home territory....There was, of course, safety in numbers. When today so few children are out alone, the venturesome child feels vulnerable indeed. In Britain, in 1971, eighty per cent of all seven- and eight-year-olds went to school on their own. By 1990, this had dropped to nine per cent. In 2010, two children, aged eight and five, cycled to school alone and their headmaster threatened to report their parents to social services. They should have been awarded a medal for allowing their children the freedom which we took for granted and which gave us so much."

"Along with everyone else I knew, from the first day of school we walked there. I went with my brothers and friends, a little ragged string of us, taking short cuts that weren't, chatting nonsense, swapping things, eating sweets, making dares, sticking chewing gum on the walls, doing deals, showing off, doing silly walks, shuffling, holding hands, telling secrets, getting the giggles. It was a crucial part of the whole business of childhood. We learned our home territory....There was, of course, safety in numbers. When today so few children are out alone, the venturesome child feels vulnerable indeed. In Britain, in 1971, eighty per cent of all seven- and eight-year-olds went to school on their own. By 1990, this had dropped to nine per cent. In 2010, two children, aged eight and five, cycled to school alone and their headmaster threatened to report their parents to social services. They should have been awarded a medal for allowing their children the freedom which we took for granted and which gave us so much."

"See, this is my opinion: we all start out knowing magic," says Robert McCammon (in Boy's Life). "We are born with whirlwinds, forest fires, and comets inside us. We are born able to sing to birds and read the clouds and see our destiny in grains of sand. But then we get the magic educated right out of our souls. We get it churched out, spanked out, washed out, and combed out. We get put on the straight and narrow and told to be responsible. Told to act our age. Told to grow up, for God���s sake. And you know why we were told that? Because the people doing the telling were afraid of our wildness and youth, and because the magic we knew made them ashamed and sad of what they���d allowed to wither in themselves."

"Because children grow up," writes Tom Stoppard (in The Coast of Utopia), "we think a child's purpose is to grow up. But a child's purpose is to be a child. Nature doesn't disdain what lives only for a day. It pours the whole of itself into the each moment. We don't value the lily less for not being made of flint and built to last. Life's bounty is in its flow, later is too late. Where is the song when it's been sung? The dance when it's been danced? It's only we humans who want to own the future, too."

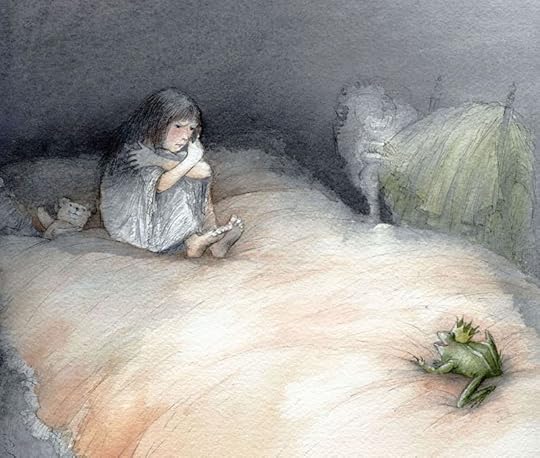

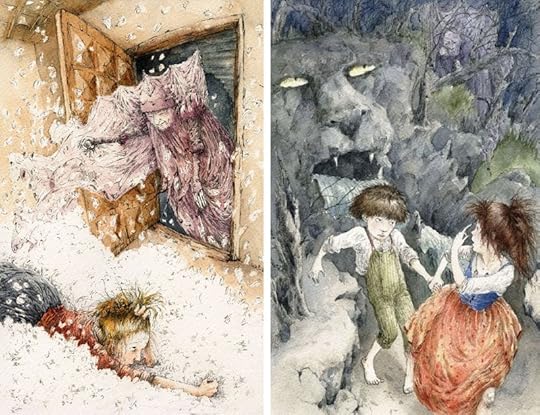

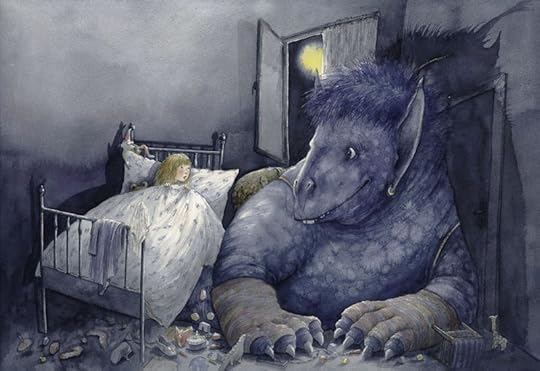

The lovely art today is by the German book illustrator and graphic designer Crista Unzner. Born and educated in Berlin, she has lived in Italy, Mexico, Nicaragua, The Netherlands, and now divides her time between Berlin and the south of France, sharing homes in both places with her husband and their dog. Please visit Crista Unzner's website to see more of her work.

The Jay Griffiths quotes in this post and in the picture captions (run your cursor over the images to see them) are all from Kith: The Riddle of the Childscape (Hamish Hamilton, 2013). I highly recommend reading it in full, along with her previous books Wild: An Elemental Journey and Pip Pip: A Sideways Look at Time.

The Jay Griffiths quotes in this post and in the picture captions (run your cursor over the images to see them) are all from Kith: The Riddle of the Childscape (Hamish Hamilton, 2013). I highly recommend reading it in full, along with her previous books Wild: An Elemental Journey and Pip Pip: A Sideways Look at Time.

June 11, 2015

In the forest, the child. In the child, the forest.

"Zurrumurru -- whisper, in the Basque language -- hush!" writes Jay Griffiths in Kith, her excellent investigation of childhood past and present. "Step from the ordinary noise of the tilled fields or the busy streets into the quiet of the woods. Step across the boundary and the trespass of story will begin. The forest takes a deep breath and through its whispering leaves an incipient adventure unfurls. The quest. In the lull -- not the drowsy lull of a lullaby but the sotto voce of a woodland clearing, scented with story as it is with with wild garlic -- this is the moment of beginning, the pause on the threshold before the journey. So many tales begin here, hard by a great forest....

"Children go to the woods when they need to think about their own stories in their own lives. Tom Sawyer, upset after a quarrel, 'entered a dense wood, picked his pathless way to the center of it, and sat down on a mossy spot under a spreading oak,' with that instinct children have about thinking under -- or in -- oak trees.

"American author Howard Thurman describes a 'unique relationship' he had with an oak tree as a child: 'I could reach down in the quiet places of my spirit, take out my bruises and my joys, unfold them and talk about them. I could talk aloud to the oak tree and knew I was understood.'

"In his often unhappy childhood, the poet John Burnside would spend hours in the woods looking for angels. There, 'another life began...when the perfect moment came, it would take hold of your spirit.' "As a child, Jean Liedloff found a glade and walked 'as though into a magical or holy place, to the center.' There she lay with her cheek on moss. 'It is here,' she thought. 'I felt I had discovered the missing center of things, the key to rightness itself.'

"Children need the woods for their spirits to thrive. A woodland gives children a trustworthy tranquility; it 'calms' the mind, in John Clare's term. Like many children, Clare had an emotional attachment to certain trees. 'We felt thy kind protection like a friend,' he wrote to an elm which was later felled for the Enclosures, in which act, he writes, 'our friendship was betrayed.' A friend of mine was asked, together with his classmates, to plant a tree each in the schoolyard, and although he did not love the school, the tree was like a friend and he tended it for two years. Suddenly, without warning, the school ripped out the trees and tarmacked over the ground for a car park. He was upset, bitterly betrayed.

"Tagore, as a child, befriended a banyan tree, his eyes drawn to the shadow-play in its aerial roots coiling and stretching in green leaf-light which played on the child's imagination: 'It seemed as if into this mysterious region...some old-world dreamland had escaped the divine vigilance and lingered on.' Tagore's friendship with the tree endured. He kept a tryst with the tree all his life, writing to it when he was an adult. Children trust the trees which they befriend and find in trees something as solid, as enduring, as rooted as truth. Trees stand for the deep truths of the psyche which language knows. The words 'tree,' 'endure,' 'tryst,' 'trust,' and 'truth' are all related, sharing a common root in Indo-European languages.

"Many spiritual traditions have long known that trees are good to thing with. The Buddha meditated under a tree and there are many cultural versions of the 'tree of knowledge.' Children have instinctively gone to the woods to reflect, to mull things over, yet so many children today are denied that solid witness of trees which children attest helps them psychologically.

"So common is a child's love for trees, so common a memory in later life, so common the friendship, the consolation and the calm, that its absence is shocking. In the nineties, at a woodland project for children in London, forty children aged seven and eight arrived one morning for a visit. Only two out of the forty had ever been to a woodland before. There should be a word for this lack -- a woodless child, as one speaks of a fatherless child, a homeless or a friendless child. They may live too far from a woodland to get there easily, they may be literally fenced out in woodland privatization, they may be scared off by bogus bogeyman tales, they may worry they wouldn't know what to do without artificial toys and, so often, they don't have the time, those long aerial afternoons of coiling hours and stretching days which, like Tagore's banyan tree, escape the benign vigilance of parents and linger on.

"Whatever the reason, an unwooded childhood is bleak. This, to me, is another part of an answer to the riddle of the childhood today. Children are being given medication for the sorrows of the psyche in greatly increasing numbers and yet at the same time they are denied the soul medicine which has always cared for children's spirits: the woods.

"When utilitarian capitalism looks at the forests, it sees the raw material of timber. But there are raw materials of the child's soul, including reverie, magic, time, transformation, destiny and identity, and the greenwood is a dreamwood for the mind at play. In T.H. White's novel The Sword in the Stone the child King Arthur is educated by Athene (wisdom) into the time of the forest and he dreams the thoughts and conversations of trees. The raw material of time grows here as the Wild Wood of the British imagination grew at the end of the Ice Age. It is ancient and long gone yet it is evergreen in memory. In the forests there is an abeyance of clock-time, a freedom outside time. Elsewhere in the lucky literature of childhood, wood is the raw material of magic, so the wardrobe through which the children reach Narnia is made from wood from an apple tree which itself grew out of an apple pip from Narnia."

"T.H. White's Arthur is sent to the forest to seek his identity; many children find woodlands the right place to go to talk to themselves, to dream themselves into a different being, to effect their changeling masquerades away from the eyes of adults. For under the gaze of others, a child can be forced to hold one form, to keep a single identity, but in woodshade and tree-shadow, a child's spirit can stretch, alter and change; it is always easier to change yourself in the dark."

"In the forest, the child. In the child, the forest. Dwelling well within themselves, children can right wrong turns, can find the clarity of a clearing in the woods. Breath deeply enough the scents of pine, mushroom, moss and beech mast and they will stay with you: listen to the forest attentively enough in childhood and the blackbird will still be singing seventy years on.

"To be 'grounded' and 'well rooted,' to be able to 'stand firm' or 'stand one's ground' and also to 'branch out' and to be as resilient as the willow's lovely sprung strength: terms of psychological health can seem like descriptions of trees. (The word 'resilient' is related to the Latin word for willow, salix.) The woods are the place for the unfolding of mind in a child, like a fiddlehead fern unfolding in the spring, a green mind sprung with resilience, curiosity and story."

The poem in the picture captions comes from A Timbered Choir by Wendell Berry. Related posts: "Wild Children," "Tales of the Forest," "The Dark Forest," "In the Forest of Stories, " and "The Gift of Wonder."

The poem in the picture captions comes from A Timbered Choir by Wendell Berry. Related posts: "Wild Children," "Tales of the Forest," "The Dark Forest," "In the Forest of Stories, " and "The Gift of Wonder."

June 10, 2015

Finding the way to the green

From Kith: The Riddle of the Childscape by Jay Griffiths:

"Every generation of children instinctively nests itself in nature, no matter matter how tiny a scrap of it they  can grasp. In a tale of one city child, the poet Audre Lord remembers picking tufts of grass which crept up through the paving stones in New York City and giving them as bouquets to her mother. It is a tale of two necessities. The grass must grow, no matter the concrete suppressing it. The child must find her way to the green, no matter the edifice which would crush it.

can grasp. In a tale of one city child, the poet Audre Lord remembers picking tufts of grass which crept up through the paving stones in New York City and giving them as bouquets to her mother. It is a tale of two necessities. The grass must grow, no matter the concrete suppressing it. The child must find her way to the green, no matter the edifice which would crush it.

"The Maori word for placenta is the same word for land, so at birth the placenta is buried, put back in the mothering earth. A Hindu baby may receive the sun-showing rite surya-darsana when, with conch shells ringing to the skies, the child is introduced to the sun. A newborn child of the Tonga people 'meets' the moon, dipped in the ocean of Kosi Bay in KwaZulu-Natal. Among some of the tribes of India, the qualities of different aspects of nature are invoked to bless the child, so he or she may have the characteristics of earth, sky and wind, of birds and animals, right down to the earthworm. Nothing is unbelonging to the child.

" 'My oldest memories have the flavor of earth,' wrote Frederico Garc��a Lorca. In the traditions of the Australian deserts, even from its time in the womb, the baby is catscradled in kinship with the world. Born into a sandy hollow, it is cleaned with sand and 'smoked' by fire, and everything -- insects, birds, plants, and animals -- is named to the child, who is told not only what everything is called but also the relationship between the child and each creature. Story and song weave the child into the subtle world of the Dreaming, the nested knowledge of how the child belongs.

"The threads which tie the child to the land include its conception site and the significant places of the Dreaming inherited through its parents. Introduced to creatures and land features as to relations, the child is folded into the land, wrapped into country, and the stories press on the child's mind like the making of felt -- soft and often -- storytelling until the feeling of the story of the country is impressed into the landscape of the child's mind.

"That the juggernaut of ants belongs to a child, belligerently following its own trail. That the twitch of an animal's tail is part of a child's own tale or storyline, once and now again. That on the papery bark of a tree may be written the songline of a child's name. That the prickles of a thornbush may have dynamic relevance to conscience. That a damp hollow by the riverbank is not an occasional place to visit but a permanent part of who you are. This is the beginning of belonging, the beginning of love.

"In the art and myth of Indigenous Australia, the Ancestors seeded the country with its children, so the shimmering, pouring, circling, wheeling, spinning land is lit up with them, cartwheeling into life....

"The human heart's love for nature cannot ultimately be concreted over. Like Audre Lord's tufts of grass,  it will crack apart paving stones to grasp the sun. Children know they are made of the same stuff as the grass, as Walt Whitman describes nature creating the child who becomes what he sees:

it will crack apart paving stones to grasp the sun. Children know they are made of the same stuff as the grass, as Walt Whitman describes nature creating the child who becomes what he sees:

There was a child went forth every day

And the first object he look'd upon, that object he became...

The early lilacs became part of this child...

And the song of the phoebe-bird...

In Australia, people may talk of the child's conception site as the origin of their selfhood and their picture of themselves. As Whitman wrote of the child becoming aspects of the land, so in Northern Queensland a Kunjen elder describes the conception site as 'the home place for your image.' Land can make someone who they are, giving them fragments of themselves."

And yet, Griffiths warns, ''consumer societies are stealing children away from their kith, their family of nature, in a steady alienation. This is not about some luxury, a hobby, a bit of playtime in the garden. This is about the longest, deepest necessity of the human spirit to know itself in nature, and about the homesickness children feel, whose genesis is so obvious but so little examined. Writer on Native American spirituality Linda Hogan describes the term susto as a sickness of soul caused by disconnection from nature and cured by 'the great without.'"

I'm interested in the ways that fantasy literature and mythic arts can address modernity's epidemic of susto, leading us back to the natural world in imagination, and in reality. Indeed, it's my belief that artforms like ours, deep-rooted in myth, folklore, and archetypal symbology, are uniquely suited to do so. I'll be quoting more passages from Kith in the week ahead, as well as adding my own thoughts on the subject; and I invite you all to contribute to the discussion in the Comments below.

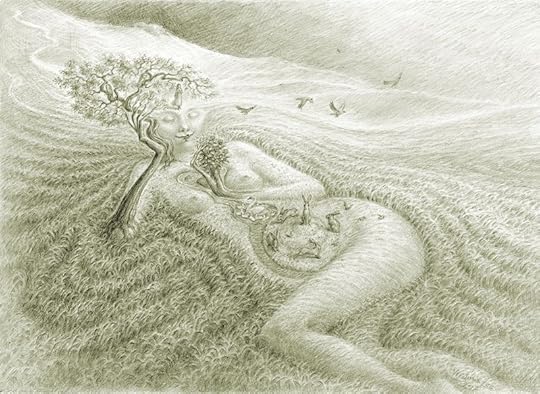

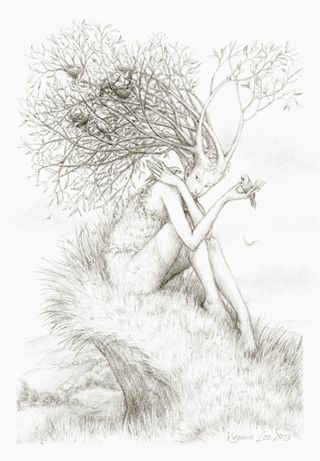

The art in this post is by my friend and neighbor Virginia Lee. To see more of her wonderful, whimsical, exquisitely beautiful paintings, drawings, and sculptures, please visit Virginia's website, mythic arts blog, and Etsy shop.

The pictures of Tilly as a puppy are from 2009; the others were taken in fields bright with buttercups this morning.

The pictures of Tilly as a puppy are from 2009; the others were taken in fields bright with buttercups this morning.

June 9, 2015

Picking Nettles

Parts of this post were first published in May 2012, with additional text and photos added.

Parts of this post were first published in May 2012, with additional text and photos added.

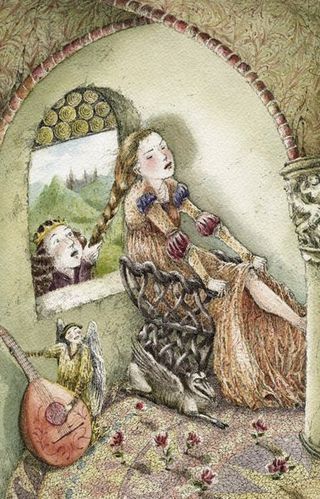

In the fairy tale of "The Wild Swans" by Hans Christian Andersen, the heroine's brothers have been turned into swans by their evil stepmother. A kindly fairy instructs her to gather nettles in a  graveyard by night, spin their fibers into a prickly green yarn, and then knit the yarn into a coat for each swan brother in order to break the spell -- all of which she must do without speaking a word or her brothers will die. The nettles sting and blister her hands, but she plucks and cards, spins and knits, until the nettle coats are almost done -- running out of time before she can finish the sleeve on the very last coat. She flings the coats onto her swan-brothers and they transform back into young men -- except for the youngest, with the incomplete coat, who is left with a wing in the place of one arm. (And there begins a whole other tale.)

graveyard by night, spin their fibers into a prickly green yarn, and then knit the yarn into a coat for each swan brother in order to break the spell -- all of which she must do without speaking a word or her brothers will die. The nettles sting and blister her hands, but she plucks and cards, spins and knits, until the nettle coats are almost done -- running out of time before she can finish the sleeve on the very last coat. She flings the coats onto her swan-brothers and they transform back into young men -- except for the youngest, with the incomplete coat, who is left with a wing in the place of one arm. (And there begins a whole other tale.)

This was one of my favorite stories as a child, for I too had brothers in harm's way, and I too was a silent sister who worked as best I could to keep them safe, and sometimes succeded, and sometimes failed, as the plot of our lives unfolded. The story confirmed that courage can be as painful as knitting coats from nettles, but that goodness can still win out in the end. Spells can broken, and gentle, loving persistence can be the strongest magic of them all.

I grew up with the story, but not with Urtica dioica: "common nettles" or "stinging nettles." I imagined them as dark, thorny, and witchy-looking -- and although they're actually green and ordinary, growing thickly in fields and hedges here in Devon, nettles emerge nonetheless from the loam of old stories and glow with a fairy glamour. It is a plant that heralds the return of spring, a tonic of vitamins and minerals; and also a plant redolent of swans and spells, of love and loss and loyalty, of ancient powers skillfully knotted into the most traditional of women's arts: carding, spinning, knitting, and sewing.

According to the Anglo-Saxon "Nine Herbs Charm," recorded in the 10th century, sti��e (nettles) were used as a protection against "elf-shot" (mysterious pains in humans or livestock caused by the arrows of the elvin folk) and"flying venom" (believed at the time to be one of the four primary causes of illness). In Norse myth, nettles are associated with Thor, the god of Thunder; and with Loki, the trickster god, whose magical fishing net is made from them. In Celtic lore, thick stands of nettles indicate that there are fairy dwellings close by, and the sting of the nettle protects against fairy mischief, black magic, and other forms of sorcery.

Nettles once rivaled flax and hemp (and later, cotton) as a staple fiber for thread and yarn, used to make everything from heavy sailcloth to fine table linen up to the 17th/18th centuries. Other fibers proved more economical as the making of cloth became more mechanized, but in some areas (such as the highlands of Scotland) nettle cloth is still made to this day. "In Scotland, I have eaten nettles," said the 18th century poet Thomas Campbell, "I have slept in nettle sheets, and I have dined off a nettle tablecloth. The young and tender nettle is an excellent potherb. The stalks of the old nettle are as good as flax for making cloth. I have heard my mother say that she thought nettle cloth more durable than any other linen."

"Nettles have numerous virtues," writes Margaret Baker in Discovering the Folklore of Plants. "Nettle oil preceded paraffin; the juice curdled milk and helped to make Cheshire cheese; nettle juice seals leaky barrels; nettles drive frogs from beehives and flies from larders; nettle compost encourages ailing plants; and fruits packed in nettle leaves retain their bloom and freshness.

"Mixing medicine and magic, a healer could cure fever by pulling up a nettle by its roots while speaking the patient's name and those of his parents. Roman soldiers in damp Britain found that rheumatic joints responded to a beating with nettles. Tyroleans threw nettles on the fire to avert thunderstorms, and gathered nettle before sunrise to protect their cattle from evil spirits."

The medicinal value of nettles is confirmed by Julie Bruton-Seal & Matthew Seal in their useful book Hedgerow Medicine:

"Nettle was the Anglo-Saxon sacred herb wergula, and in medieval times nettle beer was drunk for rheumatism. Nettle's high vitamin C content made it a valuable spring tonic for our ancestors after a winter of living on grain and salted meat, with hardly any green vegetables. Nettle soup and porridge were popular spring tonic purifiers, but a pasta or pesto from the leaves is a worthily nutritious modern alternative. Nettle soup is described by one modern writer as 'Springtime herbalism at one of its finest moments.' This soup is the Scottish kail. Tibetans believe that their sage and poet Milarepa (AD 1052-1135) lived solely on nettle soup for many years until he himself turned green: a literal green man.

"Nettles enhance natural immunity, helping protect us from infections. Nettle tea drunk often at the start of a feverish illness is beneficial. Nettles have long been considered a blood tonic and are a wonderful treatment for anaemia, as they are high in both iron and chlorophyll. The iron in nettles is very easily absorbed and assimilated. What cooks will tell you is that two minutes of boiling nettle leaves will neutralize both the silica 'syringes' of the stinging cells and the histamine or formic acid-like solution that is so painful."

Nattadon Nettle Soup

Melt some butter in the bottom of the soup pot, add a chopped onion or two, and cook slowly until softened.

Add a litre or so of vegetable or chicken stock, with salt, pepper, and any herbs you fancy.

Add 2 large potatoes (chopped), a large carrot (chopped), and simmer until almost soft. If you like your soup thick, use more potatoes.

Throw in several large handfuls of fresh nettle tops, and simmer gently for another 10 minutes.

Add some cream (to taste), and a pinch of nutmeg.

Pur��e with a blender, and serve.

If you happen to have some truffle oil in your pantry, a light sprinkling on the soup tastes terrific.

And here are two more good nettle recipes: nettle pancakes and wild nettle bread.

Nettles, folk tales around the world agree, have long been associated with women's domestic magic: with inner strength and fortitude, with healing and also self-healing, with protection and also self-protection, with the ability to "enrich the soil" wherever we have been planted. Nettle magic is steeped in dualities: both fierce and soft, painful and restorative, common as weeds and priceless as jewels. Potent. Tenacious. Humble and often overlooked. Resilient.

And pretty tasty too.

The illustrations for "The Wild Swans" above are by Nadezhda Illarionova, Susan Jeffers, & Yvonne Gilbert. The Nettle Coat is by Alice Maher. Related posts: "Swan's Wing," "Swan Maidens and Crane Wives," "When Stories Take Flight: The Folklore of Birds," and "The Folklore of Food."

The illustrations for "The Wild Swans" above are by Nadezhda Illarionova, Susan Jeffers, & Yvonne Gilbert. The Nettle Coat is by Alice Maher. Related posts: "Swan's Wing," "Swan Maidens and Crane Wives," "When Stories Take Flight: The Folklore of Birds," and "The Folklore of Food."

June 7, 2015

Tunes for a Monday Morning

Today, music from three wonderful women in the American bluegrass/Celtic/roots music scene: Crooked Still's Aoife O'Donovan on guitar and vocals, Nickel Creek's Sara Watkins on fiddle and vocals, and Sarah Jarosz on guitar, banjo, and vocals. They are from Boston, California, and Texas respectively.

Above: Aoife and Sarah perform the traditional ballad "Some Tyrant" at the Telluride Bluegrass Festival, Colorado in 2014.

Below: Aoife, Sara, and Sarah record a cover of John Hiatt's "Crossing Muddy Waters" earlier this year.

Above: Aoife, Sara, and Sarah perform Nina Simone's "Be My Husband," 2015.

Below: Aoife performs her darkly beautiful song "Briar Rose," inspired both by the fairy tale and the Anne Sexton poem of that title. She's backed up by Austin Nevins on guitar and Jacob Silver on double bass, filmed in Hillsborough, North Carolina, 2013.

The paintings and drawings today are studies for the "Briar Rose" panels by Sir Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898).

June 5, 2015

The blessings of the trees

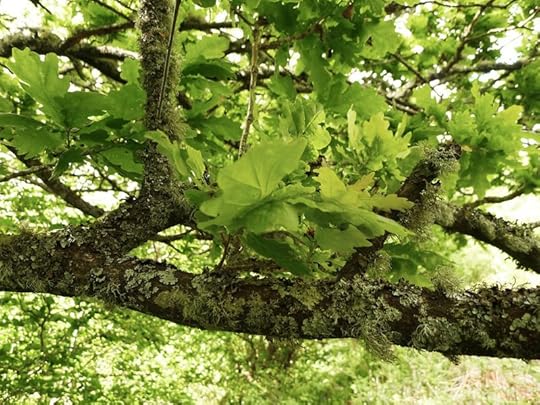

In the comments under Tuesday's post, Stuart asked a question about the oak tree in the first photograph -- and for those who don't always go back to read the comments, I'll repeat the discussion here:

Stuart Hill: Do I spy a piece of red cloth tied to the tree? A wonderfully Pagan practice of course. If it is an example of a Pagan act, it's so nice to know that the original religion of these isles is still being followed in Chagford.

Jane Yolen: Red cloth tied to tree -- pagan? Tell more, Stuart.

Stuart: Cloth (of any colour) tied to trees is an ancient tradition throughout the UK and Ireland. The cloth is a sort of physical representation of a prayer or wish in which the help of Nature Spirits and Deities is asked for. Often the prayer is related to health issues and also fertility, but help for any sort of problem, ambition or need can be sought. Sometimes coin offerings are also made, and the tree in question may stand near a well or spring, though not always. The species of the tree can sometimes be important (particularly hawthorn and oak) though again many species have been associated with the practice. Actually, I think that the West Country where Terri lives, may be one of the places where the tradition continues quite strongly. And I think there may be similar practices throughout the world; perhaps some of the Myth and Moor community could tell us?

Me: The tree in that picture is one of two trees on the hill behind our house known locally as the fairy trees. (An elderly neighbor of mine, back when I lived in Weaver's Cottage, told me the tale. She was both a staunch church goer and a firm believer in fairies.) This is the "female" tree; the "male" tree is not in the photo, although it is close by. The trees stands on two wildflower-covered humped mounds in the interstitial space between the woods and the open hill, and I photograph them only rarely, when I feel I have their "permission." ... Colored ties (cloughties) appear on these trees from time to time, and little offerings on the mounds below them: flowers, pins, and sometimes beans, which folklore tells us is a food beloved by fairies. At the moment, there's also a green cloughtie tied beside the red one. Well spotted, Stuart!

The practice of tying cloughties to sacred trees or fairy trees was once common across the British Isles and Brittany, and continues to this day in certain sacred spots, often close by wells or springs known for their healing properties. (You can read more about healing wells in a previous post:"Water, wild and sacred.") Called cloughties or clouties here in Devon and Cornwall, clooties in Scotland and the north of England, and clotties in Ireland, the term derives from local words for rags or strips of cloth.

Cloughties are sometimes left as gestures of acknowledgement and respect for the spirits of the land, and sometimes as prayers requesting general blessings or specific aid from those same spirits. At healing wells, cloughties may be left as prayers for recovery from afflictions of the body or mind: the cloth is first dipped in the water, pressed against the troubled part of the body (if the sufferer is present), and tied to the tree. The cloth then "takes up" the illness and carries it harmlessly back to wind and earth as the cloughtie slowly weathers over time and disintegrates. Other offerings common to such places are bent pins, flowers, coins, food (usually beans, honeycomb, apples, berries, or freshly baked bread), wine (in a wooden bowl or poured onto the earth), and bread soaked in ale or cider (a custom related to British and Germanic wassailing traditions).

Although at its root the tying of cloughties is a quiet, private act of communion between human beings and the local spirits of the land, in some spots the practice is so well known that it has almost become a tourist attraction -- causing friction between some of the locals who tend such sites (which have often been Christianized) and the tourists, pilgrims, and pagans who fill sacred sites with objects that others see as "litter." Aside from these well known places, however, the holy or magical trees of the West Country are honored in ways so quiet and unobtrusive (and respectful of nonbelievers) that you need sharp eyes to even notice that the cloughtie practice has been carried unbroken right up to modern times.

This is not a practice unique to Europe's pagan and Celtic Christian traditions, of course. Trees are considered sacred in many ancient cultures around the world, and offerings left in or below specials trees (called Holy Trees, Prayer Trees, Wishing Trees, Peace Trees, etc.) can be found in many lands, representing many different beliefs and religions. Here are just a few them (identified in the picture captions):

In a number of Native American traditions, "prayer ties" are created in a ritual manner and left in particular sacred spots, or else in places made sacred by a personal or community ceremony. These are generally made of strips of colored cloth, either red (representing the Red Road of indigenous spirituality) or the four colors of the four directions (the exact colors varying from tribe to tribe), with a pinch of tobacco or sacred herbs knotted in the cloth.

The cottonwood trees at the center of Sundance ceremonies are often wrapped and hung with prayer ties -- sometimes many hundreds of them, each one knotted with individual prayers and blessings. I've attended many Sundances in my time, which are profoundly beautiful and powerful, but I won't include a photograph of a prayer-wrapped Sundance tree in this post, for taking pictures at such ceremonies is generally considered disrespectful. Instead, here's a simple photograph of a string of prayers left anonymously in the wild:

A custom related to the tying of cloughties is the driving of coins into the bark of a tree for luck or increased fertility -- usually a fallen oak, ash, or sycamore, rather than a living tree. Such trees are found not only in the British Isles but also in parts of Africa, the Middle East, and East Asia. In South America, tiny silver milagros (in the shape of afflicted body parts) can be found pinned or tied to special trees, along with offerings of coins, paper money, and cigarettes beneath. Coins are also commonly thrown into holy wells and springs beside cloughtie trees -- a practice that comes down to us in the form of wishing wells and throwing pennies into a fountain for luck.

Trees have been revered since the dawn of time -- both in green, wet lands like the British Isles and in dry, hot lands where their presence is rare and precious. The folkloric customs expressing this reverence were practiced for centuries before being discouraged, even demonized, by the Abrahamic religions -- or else quietly adopted when those practices could not be entirely suppressed. Here in England's West Country, pagan sacred sites were re-dedicated to Christian saints, "well dressing" and other such rites were folded into  seasonal church celebrations, and the wild Green Men of Celtic lore were turned into church carvings representing the resurrection of Christ instead of the seasonal rebirth of nature. Today, when a love of trees is considered ecological or Romantic rather than Satanic, Christians and pagans alike can enjoy the old woodland customs of Britain's folk heritage.

seasonal church celebrations, and the wild Green Men of Celtic lore were turned into church carvings representing the resurrection of Christ instead of the seasonal rebirth of nature. Today, when a love of trees is considered ecological or Romantic rather than Satanic, Christians and pagans alike can enjoy the old woodland customs of Britain's folk heritage.

"For me," wrote the German poet and novelist Herman Hesse, "trees have always been the most penetrating preachers. I revere them when they live in tribes and families, in forests and groves. And even more I revere them when they stand alone....In their highest boughs the world rustles, their roots rest in infinity; but they do not lose themselves there, they struggle with all the force of their lives for one thing only: to fulfill themselves according to their own laws, to build up their own form, to represent themselves. Nothing is holier, nothing is more exemplary than a beautiful, strong tree. When a tree is cut down and reveals its naked death-wound to the sun, one can read its whole history in the luminous, inscribed disk of its trunk: in the rings of its years, its scars, all the struggle, all the suffering, all the sickness, all the happiness and prosperity stand truly written, the narrow years and the luxurious years, the attacks withstood, the storms endured. And every young farmboy knows that the hardest and noblest wood has the narrowest rings, that high on the mountains and in continuing danger the most indestructible, the strongest, the ideal trees grow. "

"A longing to wander tears my heart when I hear trees rustling in the wind at evening," Hesse continues. "If one listens to them silently for a long time, this longing reveals its kernel, its meaning. It is not so much a matter of escaping from one's suffering, though it may seem to be so. It is a longing for home, for a memory of the mother, for new metaphors for life. It leads home. Every path leads homeward, every step is birth, every step is death, every grave is mother. So the tree rustles in the evening, when we stand uneasy before our own childish thoughts: Trees have long thoughts, long-breathing and restful, just as they have longer lives than ours. They are wiser than we are, as long as we do not listen to them. But when we have learned how to listen to trees, then the brevity and the quickness and the childlike hastiness of our thoughts achieve an incomparable joy. Whoever has learned how to listen to trees no longer wants to be a tree. He wants to be nothing except what he is. That is home. That is happiness.���

That is happiness indeed.

Images: The pictures are identified in the captions. (Run your cursor over the images to see them.)

Credits: The local "fairy tree" was photographed by me, and the others are Wiki Commons photographs except the following: the North American prayer ties are from Tangible View, St. Brigid's Well from A Trip to Ireland, and the Green Man carving from The Company of Green Men. The painting (one of mine) is of a tree spirit, sapling child, and story-loving bunny girl. The Herman Hesse quote comes from Trees: Reflections and Poems by Hesse.

Related posts: "Water, sacred and wild," "Wild folklore," "The Folklore of Food," "Stories are Medicine: healing tales in myth, folklore and mythic arts," "Homemade ceremonies," and "The Language of the Earth."

June 3, 2015

Early morning in the greenwood

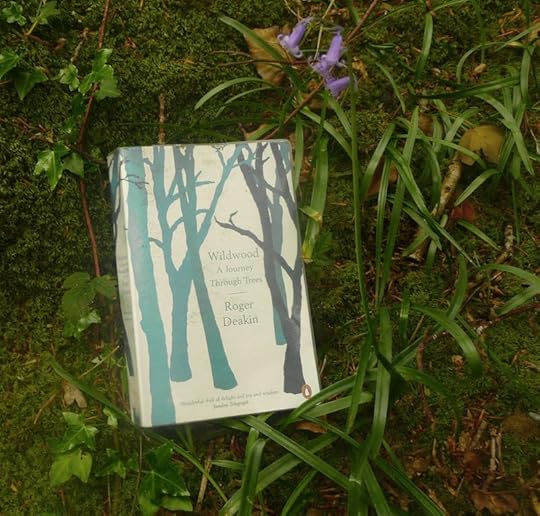

From Wildwood: A Journey Through Trees by Roger Deakin (1943-2006):

"To enter a wood is to pass into a different world in which we ourselves are transformed. It is no accident that in the comedies of Shakespeare, people go into the greenwood to grow, learn and change. It is where you travel to find yourself, often, paradoxically, by getting lost. Merlin sends the future King Arthur as a boy into the greenwood to fend for himself in The Sword and the Stone. There, he falls asleep and dreams himself, like a chameleon, into the lives of the animals and trees.

"In As You Like It, the banished Duke Senior goes to live in the Forest of Arden like Robin Hood, and in A Midsummer Night's Dream the magical metamorphosis of the lovers takes place in a wood 'outside Athens' that is quite obviously an English wood, full of the faeries and Robin Goodfellows of our folklore.

"Pinned on my study wall is a still from Truffaut's L'Enfant Sauvage. It shows Victor, the feral boy, clambering through the tangle of branches of the dense deciduous woods of the Aveyron. The film remains one of my touchstones for thinking about our relations with the natural world: a reminder that we are not so far away as we would like to think from our cousins the gibbons, who swing like angels through the forest canopy, at such headlong speed that they almost fly like the tropical birds they envy and emulate in the music of their marriage-songs at dawn in the tree-tops....

"The Chinese count wood as the fifth element, and Jung considers trees an archetype. Nothing can compete with these larger-than-life organisms for signalling the changes in the natural world. They are our barometers of the weather and of the changing seasons. We tell the time of year by them. Trees have the capacity to rise to the heavens and connect us to the sky, to endure, to renew, to bear fruit, and to burn and warm us through the winter. I know of nothing quite as elemental as the log fire glowing in my hearth, nothing that excites the imagination and the passions quite as much as its flames. To Keats, the gentle cracklings of the fire were whisperings of the household gods 'that keep / A gentle reminder o'er fraternal souls.'

"Most of the world still cooks on wood fires, and the vast majority of the world's wood is used as firewood. In so far as 'Western' people have forgotten how to lay a wood fire, or its fossil equivalent in coal, they have lost touch with nature. Aldous Huxley wrote of D.H. Lawrence that 'He could cook, he could sew, he could darn a stocking and milk a cow, he was an efficient woodcutter and a good hand at embroidery, fires always burned when he had laid them and a floor after he had scrubbed it was thoroughly clean.' As it burns, wood releases the energies of the earth, water and sunshine that grew it. Each species expresses its character in its distinctive habits of combustion. Willow burns as it grows, very fast, spitting like a firecracker. Oak glows reliably, hard and long. A wood fire in the hearth is a little household sun.

"When Auden wrote, 'A culture is no better than its woods,' he knew that, having carelessly lost more of their woods than any other country in Europe, the British take a correspondingly greater interest in what trees and woods they still have left. Woods, like water, have been suppressed by motorways and the modern world, and have come to look like the subconscious of the landscape. They have become the guardians of our dreams of greenwood liberty, of our wildwood, feral, childhood selves, of Richmal Crompton's Just William and his outlaws. They hold the merriness of Merry England, of yew longbows, of Robin Hood and his outlaw band. But they are also repositories of the ancient stories, of Icelandic myths of Ygdrasil the Tree of Life, Robert Graves's 'The Battle of the Trees' and the myths of Sir James Frazer's Golden Bough. The enemies of the woods are always enemies of culture and humanity."

June 2, 2015

Writers and readers, part 2

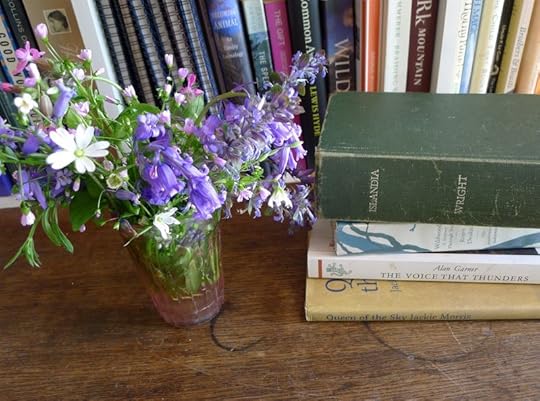

From "Porlock Prizes" by Alan Garner (1979):

"A writer has to live an insoluable paradox. He requires a public, and he can achieve it only by becoming most private. I have been doing nothing else but writing for twenty-three years, and have been published for almost nineteen. For four years no one knew that I was writing, and I had no evidence that I could learn to write. Now, if I were still unpublished, would I still be writing? Yes, I should. A more telling question is whether I would have written the books I have written, in the order I wrote them, and whether they would in all respects be the same books. That is: has recognition, of whatever kind, influenced the development of the work?

"I feel that the books would have emerged as they are, but even more slowly. That is what I feel: and I know that I am wrong."

"The enduring creative act is between the work and the perceiver, and each re-creation says more about the work, and from each re-creation there builds a momentum, which grows to a collaborative response, which I become aware of and am helped by. The help is not so much a deed at a given time but an atmosphere. It is more subtle than applause. Applause tempts the performer to show off, to please, to repeat. All that is damaging. The help I mean is simple. It is the quiet nod, the unostentatious sign that what one does is worthwhile."

"The solitary reader, who may never speak about the experience, by the act of reading adds somehow to the communal response and brings about the environment in which the writer may flourish. Then the privacy of the writer and the isolation of the reader are transcended and become a reciprocal dialogue."

"Porlock Prizes" by Alan Garner can be found in his essay collection The Voice That Thunders. The poem in the picture captions is from Collected Poems, 1943-2004 by Richard Wilbur.

"Porlock Prizes" by Alan Garner can be found in his essay collection The Voice That Thunders. The poem in the picture captions is from Collected Poems, 1943-2004 by Richard Wilbur.

June 1, 2015

Writers and readers

"A book, properly written, is an invitation for a reader to enter: to join with the writer in a creative act: the act of reading. A novel, it has been said, is a mechanism for generating interpretations. If interpretation is limited to what the author 'meant,' the creative opportunity has been missed. Each reading should a unique meeting, leading to a new interpretation. Nor should the writer's duty end at the text.

"Writing is solitary and isolate, but only in execution. I work alone, in an empty room; yet that work, though solitary, is not private. Somewhere, in another place and another time, which will become another here and another now, there will be a communication with another mind. My duty is first to the text, because the writer is, by writing, above all making a claim for excellence. In working the language, as a farmer works the land, we seek to strengthen it against abuse, to protect it against decay, to encourage it towards growth. We hope to leave the language a little better for our writing; and that writing is achieved only in isolation. Yet, at the end, there is always somebody, an unknowable 'you,' whom I wish to reach."

- Alan Garner (The Voice That Thunders)

"The writer, functioning in a magical medium, an abstract medium, does one half of the work, but the reader does the other. The reader's mind becomes the screen, the place, the era. To a large extent, readers create the world from words, they invent the reality they read. Reading therefore is a co-production between writer and reader. The simplicity of this tool is astounding. So little, yet out of it whole worlds, eras, characters, continents, people never encountered before, people you wouldn't care to sit next to on a train, planets that don't exist, places you've never visited, enigmatic fates, all come to life in the mind, painted into existence by the reader's creative powers. In this way, the creativity of the write calls up the creativity of the reader. Reading is never passive."

- Ben Okri (A Way of Being Free)

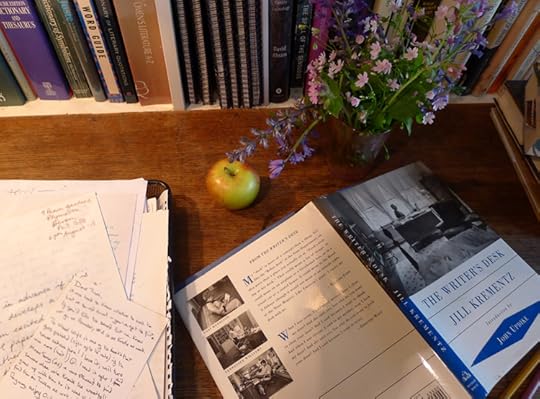

"All sorts of pleasant and intelligent people read my books and write thoughtful letters about them. I don't know who they are, but they are marvelous and seem to live quite independly of the prejudices of advertising, journalism, and the cranky academic world. The room where I work has a window looking into a wood, and I like to think that these earnest, loveable, and mysterious readers are in there." - John Cheever (quoted in The Writers' Desk by Jill Krementz)

"I can't write without a reader. It's precisely like a kiss -- you can't do it alone." - John Cheever (Christian Science Monitor, 1979)

''Books. They are lined up on shelves or stacked on a table. There they are wrapped up in their jackets, lines of neat print on nicely bound pages. They look like such orderly, static things. Then you, the reader come along. You open the book jacket, and it can be like opening the gates to an unknown city, or opening the lid of a treasure chest. You read the first word and you're off on a journey of exploration and discovery.'' - David Almond

May 31, 2015

Tunes for a Monday Morning

I've been on a bit of a Kris Drever marathon lately, so he is the connecting link between all of our songs today. Drever (the son of folk musician Ivan Drever) is a singer/songwriter who performs with the award-winning trio Lau, as well as with a wide variety of other musicians and solo. He was raised in the Orkney Islands off the far north coast of Scotland, and although he's now based in Edinburgh, his songs are often drawn from Orcadian life, landscape, and history.

Above: "Hinba," an original instrumental piece by Lau (Kris Drever on guitar, Martin Green on accordion, and Aidan O'Rourke on fiddle), played in Leeds in 2011. The group's name comes from an Orcadian word meaning "natural light."

Below: Lal Waterson's classic song "Midnight Feast," performed by Lau last year -- accompanied by Aoife O'Donovan, a brilliant young singer/songwriter from Boston.

Above: "Capernaum" by Kris Drever and Irish instrumentalist ��amonn Coyne, performed in 2014.

Below: Drever's beautiful song "The Poorest Company," performed by Drever McCusker Woomble at Celtic Connections in Glasgow, 2009. The trio (Kris Drever on guitar, John McCusker on fiddle, and Roddy Woomble on backing vocals) is accompanied here by Heidi Talbot (from Cherish the Ladies) and Boo Hewerdine. I personally think Drever is proving to be one of the great songwriters of our age.

For more music this morning, there's a previous post on Lau here (which includes Drever's gorgeous song "Ghosts," on the subject of immigration).

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers