Terri Windling's Blog, page 134

July 4, 2015

Re-posted from the archives: Happy 4th of July!

Happy Birthday to the beautiful, maddening, complicated, tragic, incredibly friendly and unbelievably diverse country I come from.

I grew up with John Mellencamp's music, and it embodies for me the essence of that particular slice of left-leaning working-class America that my Pennsylvania brothers and I come from: those big-hearted, union-joining, hard-working, open-minded, racially/culturally mixed, quick-witted, generous-spirited men and women that are the backbone of so many communities all across the country. (Mellencamp himself has done a lot of work for rural poverty issues and is one of the founders of Farm Aid.) These tunes go out to all of my brothers. Drink a beer for me today.

Above, Mellencamp's "Our Country" video from 2006. (Preach it, John!) Below, classic Mellencamp from the '80s.

And a related post that seems appropriate today: "Thoughts About Home."

June 29, 2015

Update

Dear Readers, it may be another week, or a bit longer, before I can return to Myth & Moor. I haven't actually left home yet, having been grounded by a bad case of flu. Travel has thus been postponed (not cancelled) until I'm fully back on my feet. I'll get back to blogging just as soon as I can, and thank you for your patience in the meantime.

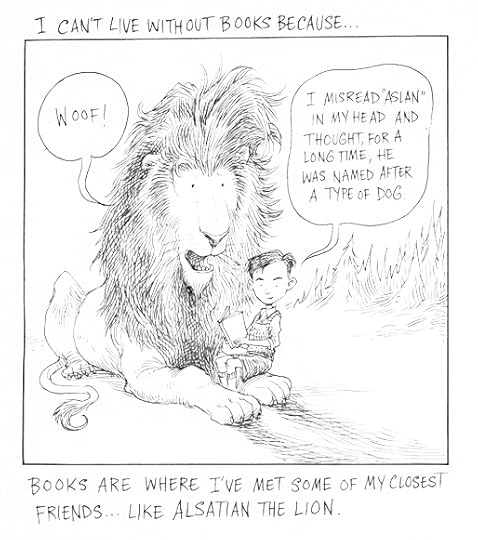

Despite being stuck in bed this week, looking at the world through window glass, words printed in ink on the cream-colored pages of a book have carried me back into the woods (and far beyond), and I find that magical. Flu is short, and passing, but art is long. And it is potent medicine.

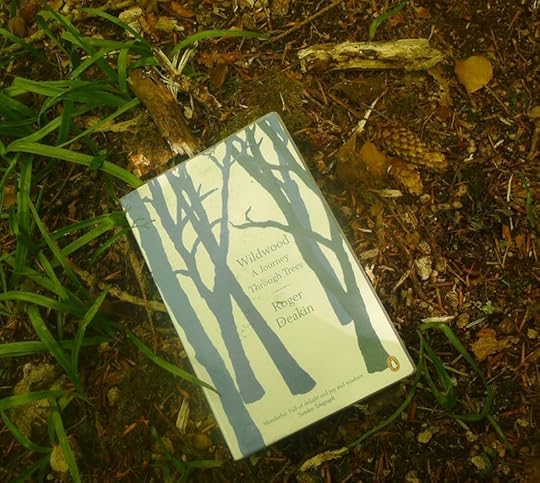

I've been re-reading old favorites (which is easier than first-time reading when fever rages), from Roger Deakin's Wildwood to Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials trilogy, Alan Garner's Red Shift, and Jane Yolen's The Magic Three of Solatia. Next up: diving into Patricia McKillip's backlist. Even flu has a silver lining.

"What an astonishing thing a book is," Carl Sagan once remarked. "It's a flat object made from a tree with flexible parts on which are imprinted lots of funny dark squiggles. But one glance at it and you're inside the mind of another person, maybe somebody dead for thousands of years. Across the millennia, an author is speaking clearly and silently inside your head, directly to you. Writing is perhaps the greatest of human inventions, binding together people who never knew each other, citizens of distant epochs. Books break the shackles of time. A book is proof that humans are capable of working magic."

Related post: "Books, The Beast, and Me"

Related post: "Books, The Beast, and Me"

June 18, 2015

Flying off...

I'm about to head off to Hollins University in Virginia, where I'll be the writer-in-residence at the excellent Children's Book Writing & Illustrating M.F.A. program this year. I feel quite honored to be joining an an extraordinary faculty of writers, artists, and academics to discuss the practice of this important art form with M.F.A. students.

I'll be off-line while I travel and settle in, and then Myth & Moor will resume from the beautiful Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia (where Annie Dillard wrote Pilgrim at Tinker Creek) -- so please check back in a week or so.

"Why do you go away? So that you can come back. So that you can see the place you came from with new eyes and extra colors. And the people there see you differently, too. Coming back to where you started is not the same as never leaving." - Terry Pratchett (A Hat Full of Sky)

Dear Readers,

Due to work and travel, I'll be off-line for the next week or so, but I'll be back soon.

"Why do you go away? So that you can come back. So that you can see the place you came from with new eyes and extra colors. And the people there see you differently, too. Coming back to where you started is not the same as never leaving." - Terry Pratchett (A Hat Full of Sky)

The wild sky

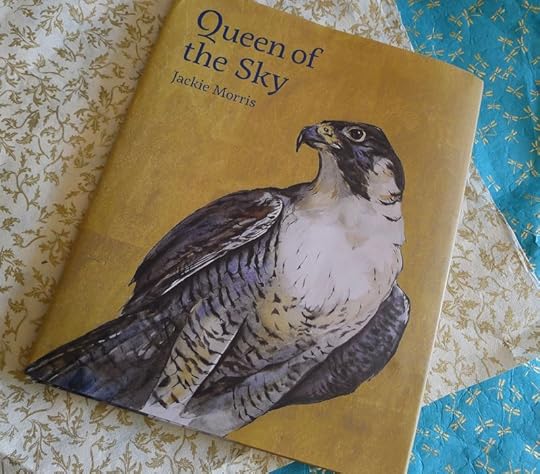

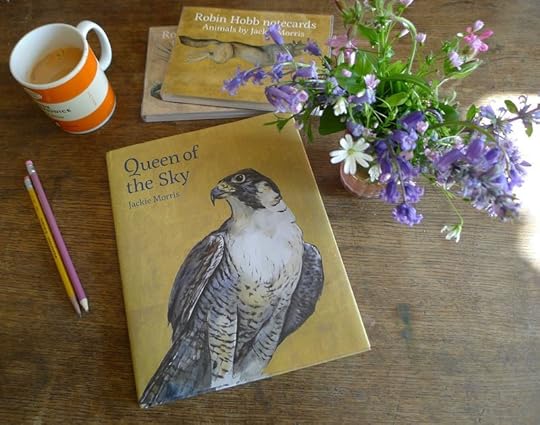

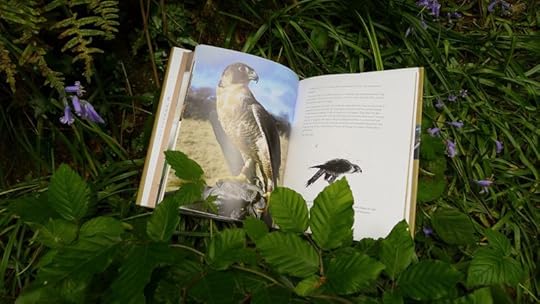

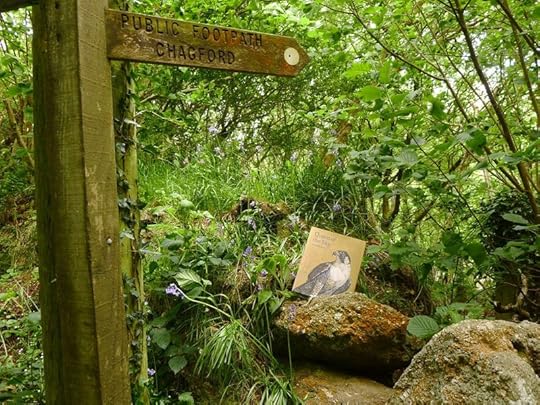

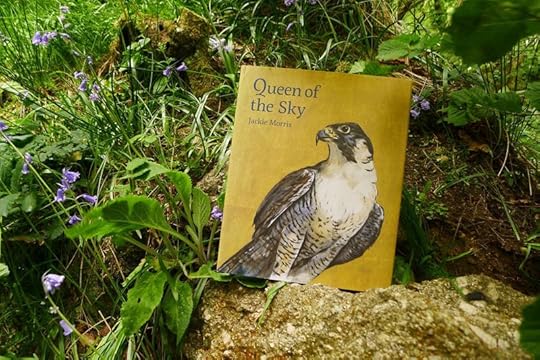

A few weeks ago, a package came in the mail. Inside, beautifully wrapped in beautiful paper was a beautiful book. Beautiful. I keep using that word. It's the only word that will do. The book was from author and artist Jackie Morris, who lives on the coast of Wales, and it tells the tale of an injured peregrine falcon rescued by her friend and neighbor Ffion Rees.

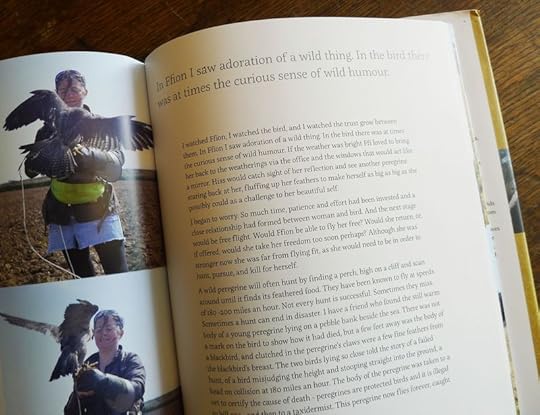

Jackie explained the genesis of the book in an article for The Guardian: "Ffion is head skipper for a boat company. She had fished the bird out from the sea having witnessed her fall...Over the next few months my wonderful friend brought this sick bird back to health and then to flying fitness. With patience, care and love she worked, building trust until this wild thing would fly to her fist at a whistle. And all the time I watched and I drew and I painted her progress, from the sick bird in the kitchen to the free flying falcon, learning the shape and the color of the hawk."

I'm ending the week with Jackie's book because it brings together so many of the different things we've been talking about lately on Myth & Moor: the importance of wild country and wild creatures in our lives; the places we turn to for kith and kin; and the ways that those of us working in the arts can express our connection to the natural world, thereby helping young people (and old people too) to find their own connections, their own personal pathways into the wild.

"I came to Pembrokeshire for the love of a man," writes Jackie. "Then I fell in love with the land." She'd found her kith, and there she's been rooted ever since, with her paints and books and children and animals in a house by the sea.

"Peregrines are simply mesmerizing," writes Nicola Davies in the book's introduction. "It's easy to be obsessed with such a creature.Reading J.A. Baker's book The Peregrine as a girl, I understood Baker's passion for the birds, his compulsion to follow and watch them. But I understood their meaning for him too: they were his conduit to the whole natural world, the living metaphor of the landscape and the seasons.

"We humans need to feel that connection. We need to feel the tug of the umbilical cord which ties us to the Earth. Through feeling it we connect better with each other just as babies learn to love through their first bond with their mother."

"I have loved birds ever since I began, as a child, to notice these little people of the air around me," writes Jackie. "I would walk with my dad and he would tell me their names and show me how to find their secret, hidden nests. He took me to see Kes at the cinema when I was older, and then I found A Kestral for a Knave by Barry Hines, the book on which the film was based. Though I was slow to catch the knack of reading I loved stories and I made my way through this slim volume. The Once and Future King and The Goshawk by T.H. White held my imagination. If I ever thought of myself as an adult it was as one who lived alone in a cottage in a wood with a hawk and a hound and a horse for company.

"The curious geography of my mind is filled with tales of birds; trickster ravens, thieving magpies, women with fine slate feather cloaks who turn into falcons when they wrap their cloaks around them, and swan women. Birds have threaded their flight through the backgrounds of my books, from redwings in The Snow Whale to lapwings in The Cat and the Fiddle, as I painted in winter while outside my studio the stark, cold fields filled with lapwings."

Queen of the Sky is a wonderful book (I confess it made me cry), weaving text, paintings, and photographs with wind and waves, feather and fur. It's a story about friendship -- between women, between species; and a story about the land, and love, and loss.

Books, it seems to me, are very magical things. Smooth white paper, printed and bound, has lifted the wings of a Welsh peregrine and carried her here to the moorlands of Devon...and beyond, to places and people that will never otherwise witness the prayer of her flight. This, to me, is what art is for. It makes the world larger, and brighter, and wilder; and it tells our stories, human and nonhuman alike.

Related posts: "When Stories Take Flight: The Folklore of Birds"," Bowing to the Birds," "T.H. White: A Rescued Mind."

Related posts: "When Stories Take Flight: The Folklore of Birds"," Bowing to the Birds," "T.H. White: A Rescued Mind."

June 17, 2015

Kith and kin

In a final post inspired by Jay Griffith's Kith: The Riddle of the Childscape, I'd like to look at the ways that some people's lives are defined by attachment to the place they come from, whereas others (in increasing numbers) live uprooted from their original place, or un-rooted in any place at all.  The world has always had its wanderers, of course -- but the balance has shifted in modern times, with more of us in motion than staying put. As we move, and move, and move again, can we genuinely root ourselves in each new place, learn the language of each land's flora and fauna, its myths and folklore, its unique spirit? Or are we doomed to transient, restless lives in which the voices of the land, of the plant world and our animal neighbors, are ones we can no longer hear?

The world has always had its wanderers, of course -- but the balance has shifted in modern times, with more of us in motion than staying put. As we move, and move, and move again, can we genuinely root ourselves in each new place, learn the language of each land's flora and fauna, its myths and folklore, its unique spirit? Or are we doomed to transient, restless lives in which the voices of the land, of the plant world and our animal neighbors, are ones we can no longer hear?

In discussing the Aboriginal culture of Australia, which, like most indigenous cultures, is deeply rooted in the land, Jay Griffiths writes:

"From song, from dream, from elements of earth and water, spirit-children are imminent in the land. They are left there by the Ancestors of the Dreaming, who sang their way across the land, leaving an imprint of music like an aural footstep. And sometimes a woman who has already physically conceived a child chances to step in that same footstep, and, if she does, part of the song and the spirit-child leap up into her so she feels a quickening, sharp as an intake of breath at a kick within, sweet as a night surprised by song. Sometimes it is the father who, seeing something unusual -- a particularly large fish or an animal behaving strangely -- may know it as an indication of a spirit-child. Or a man walking by a lake may find a spirit-child jumping into his mind, which he will send in a dream to his wife, inseminating the spirit-child within her. Then the Lawmen, the knowers of the songline which the mother or father was on, can tell which stanzas of the song belong to that child, its conception totem and, in that sinuous reflexivity of belonging, its quintessential home.

"To be born is, in Latin, nasci, and the word is related to natura, so birth, nature, the laws of nature and the idea of an essence are related. It is as if the language itself has embedded birth in the natural world. In the Amazon, people say childbirth should always take place in forest-gardens so that the condensed energy of the plants can nourish the child. In New Guinea, future generations are called 'our children who are still in the soil' and when I was in West Papua, the western half of the island, I was told that in the Dani language the expression for digging potatoes is the same as that for giving birth to a child. Women say they can sometimes hear the unearthed potatoes, which are always handled gently, calling out to them, the land singing things into being to be mothered into the world.

"Legends of childhood across the world suggest whole landscapes lit with incipience. Everywhere is potential, beginningness. It may be the inheld energy of an acorn or the liquid and endless possibilities of water; it may be the fattening of a potato in the secret earth or the leaping of a salmon that is the child Taliesin -- in whatever form it takes, the land itself is kindling children.

"In indigenous Australian culture," Griffiths continues, "there is a common idea that the land is a mentor, teacher, and parent to a child. People talk of being 'grown up by' their land; their country as kin. So do English-speakers -- without quite realizing it. A child may be looked after by its 'kith and kin,' we say, as if both terms meant family or relations. Not so. 'Kith' is from the Old English cydd, which can mean kinship but which in this phrase means native country -- one's home outside the house -- but no one I have ever met has known that meaning. This sense of belonging has nothing whatsoever to do with a nation state or political homeland, but rather with one's immediate locale, one's square mile, the first landscape that we know as children. W.H. Auden wrote of this as 'Amor Loci,' the love of his childhood landscape. Kith kindles the kinship which children so easily feel for the natural world and without that kinship, nature also loses out, bereft of the children who grow up to protect it."

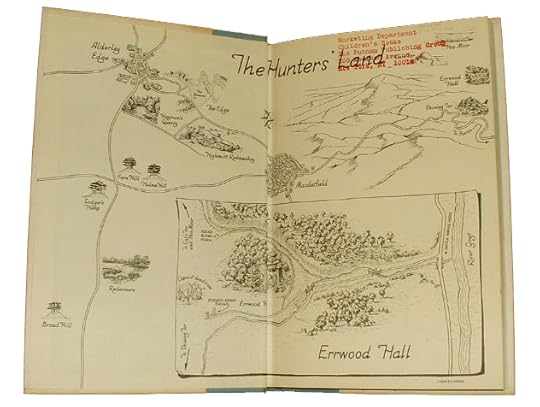

Novelist Alan Garner's "kith" is in Cheshire in the north-west England, where Garners have lived for centuries. As a descendant of rural craftsmen, he was the first of his family to attend a private grammar school, and then to go on to Oxford University. "My family," he writes (in The Voice That Thunders), "was, in the abstract, delighted that I was going to 'get an education,' just as I might have been going to get a car. For them it was a concrete object. None of us was prepared for its effect. That deep but narrow culture from which I came could not share my excitement over the wonders of the deponent verb. To them, it was an attach on their values, an attempt to make them feel inferior. A shocking alienation resulted, which we could not resolve."

At the end of his education, Garner sits on a stump by an old stone wall (built by his great-great-grandfather, Robert Garner) and ponders his future. His education has made it impossible for him to live as his father and grandfather lived, but the strength of his kith-ties makes the life of an Oxford don, living far from the soil of Cheshire, impossible too. What is the answer?

"It was staring me in the face. It was Robert's wall. On it was carved his banker mark, the rune Tyr, the boldest of the gods. When the Aesir went to bind Fenriswolf with the rope Gleipnir, which was made of the sound of a cat's footsteps, the beard of a woman, the roots of a mountain, the longings of a bear, the voices of fishes and  the spittle of birds, Fenris would not allow himself to be bound unless one of the Aesir put his right hand in Fenris' mouth as a token of goodwill. Only Tyr was willing to do so. And when Fenris was bound, and helpless, he bit Tyr's hand off at the wrist, which is still called the wolf's joint. But had Robert known this? Was it a part of the Craft and Mystery of his trade? Or was it simply that an arrow is easy to carve? Yet he had got the proportions of it right; and we are all left-handed.

the spittle of birds, Fenris would not allow himself to be bound unless one of the Aesir put his right hand in Fenris' mouth as a token of goodwill. Only Tyr was willing to do so. And when Fenris was bound, and helpless, he bit Tyr's hand off at the wrist, which is still called the wolf's joint. But had Robert known this? Was it a part of the Craft and Mystery of his trade? Or was it simply that an arrow is easy to carve? Yet he had got the proportions of it right; and we are all left-handed.

"I loved Oxford, but it was not the wall. The wall was mine. Oxford was not mine. The rune was mine. It claimed me. Whatever it was that I was going to do with my life, it would have to be done here. This was my unique place. I owned it, and it owned me. There is no word in English to express the relationship. In Russian, the word is rodina; in German, Heimat. And there, on the tree stump, by my great-great-grandfather's rune and wall, I saw my rodina, my Heimat. This is what I must serve, as no one else could. This is the integration of my divided selves....So, after a period of reflection, at three minutes past four o'clock on the afternoon of Tuesday, 4 September, 1956, I began to write a novel, The Weirdstone of Brisingamen, and I have been writing ever since."

For writers like Garner, with a deep sense of belonging to an ancestral landscape, the creation of art rooted in and expressive of that landscape can be an almost sacred calling...but what about the rest of us in this fast-paced, foot-loose, transient world: immigrants, exiles, travelers, nomads, incomers of one form or another?

Katherine Paterson addressed this question in her essay "Where is Terabithia?":

Katherine Paterson addressed this question in her essay "Where is Terabithia?":

"Flannery O'Connor, whose words about writing have meant a great deal to me, has said that writing is incarnational. By incarnational we mean that somehow the word or the idea has taken on flesh, has become physical, actual, real. We mean that the abstract idea can be percieved by the way of the senses. This immediately makes fiction different from other kinds of stories. The fairy tale begins, 'Once upon a time,' thus clearly signaling its intent to escape the actual and the everyday, but a novel takes its life from the petty details of its geography, history, and culture.

"This is one of the reasons that writers like Flannery O'Connor and Eudora Welty and William Faulkner move us so powerfully. Their roots are planted very deep in a particular soil, and they grow up and reach out from that place with a strength unknown to most writers. It is also the reason why a writer like Pasternak would refuse the Nobel Prize rather than leave Russia. For Russia, despite her terror and oppression, was the soil from which his genius sprang, and he feared that if he left her, he would leave behind his ability to write.

"What happens, then," asks Paterson, "to a writer without roots -- who is not grounded in a particular place? When I was four years old, we left 'home,' and I've never been back since. Indeed, I couldn't go back if I wanted to because the house in which we lived was torn down so that a bus station could be built on the site. Since I was four, I've lived in three different countries and seven states at about thirty different addresses. I was once asked as part of an imaginative exercise to remember in detail the house I had grown up in. I nearly had a mental breakdown on the spot. But the fact that I have no one place to call home does not make me feel that place in fiction is unimportant. On the contrary, it convinces me that I must work harder than any almost any writer I know to create or re-create the world in which a story is set and grows if I want to make a reader believe it."

Many of us today have no kith, no rodina, no ancestral place. Or we had one once, but lost it long ago. Or we've been transplanted into new soil, our roots still shallow, our claim still tenuous. Or we are homesick for a home we never actually had; for the idea of home, and of truly belonging.

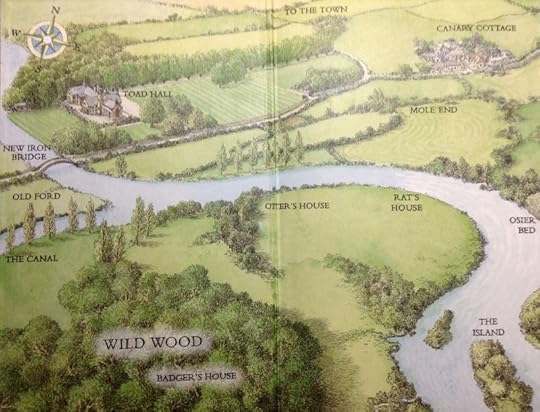

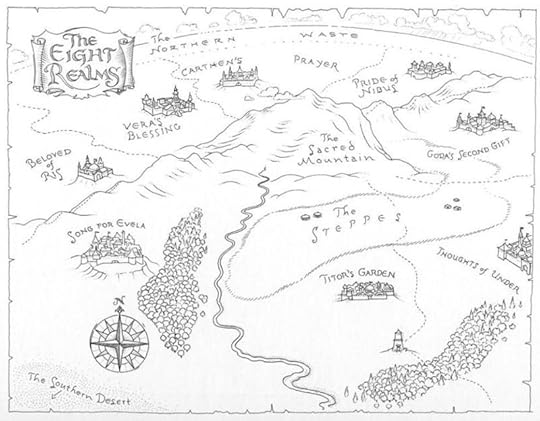

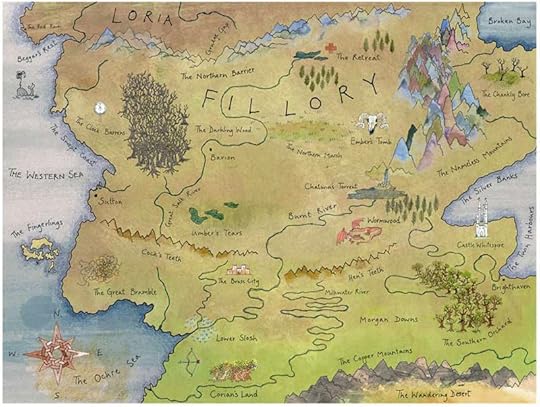

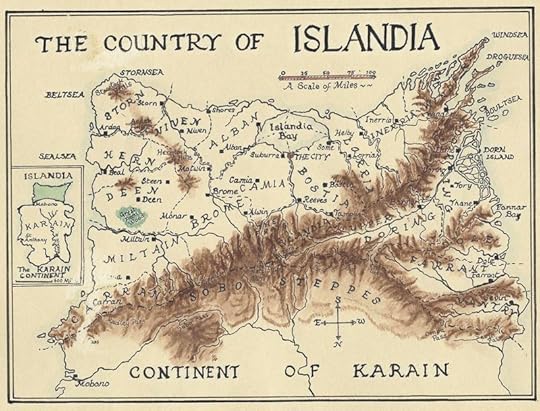

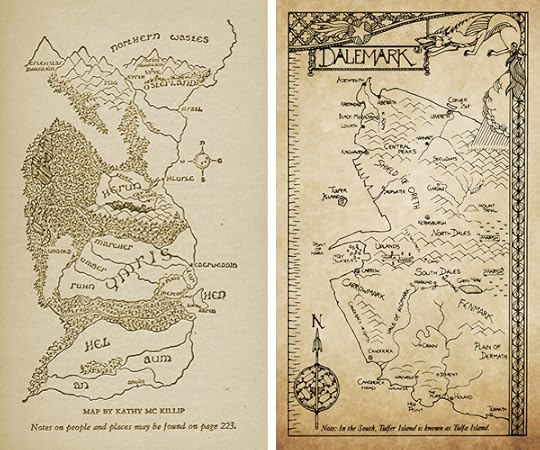

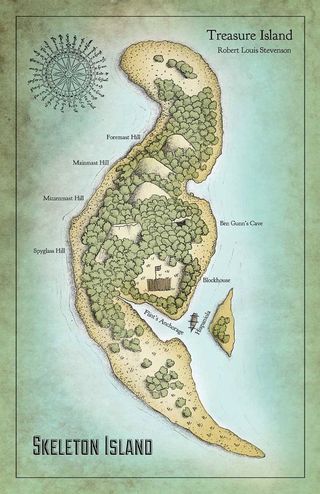

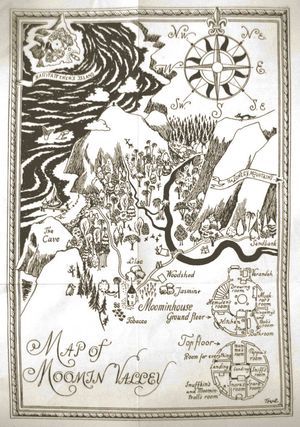

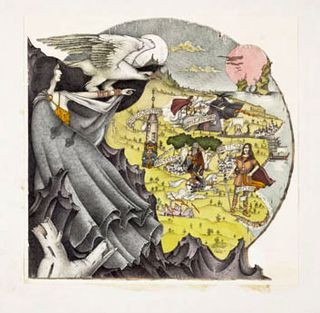

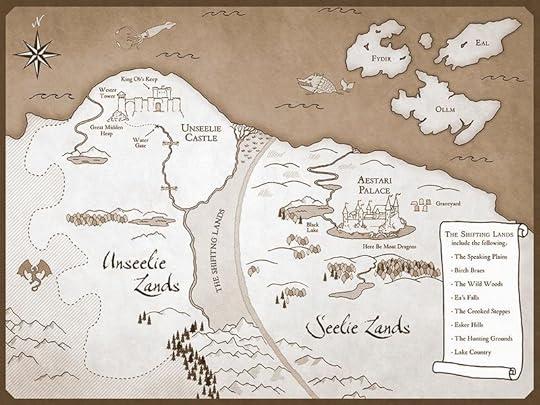

That's how it was for me for many years, until I crossed the ocean to Devon and, to my eternal surprise, its rain-drenched hills whispered in my ears: Welcome home. You've come at last. We've been waiting and waiting, and now you're here. Before, I'd found my home in the world only in the pages of certain books, and in the earth-colored tones of certain works of art: in Earthsea and Islandia, Rhyhope Wood and on the island of Hed, among Burne-Jones' briar roses and Arthur Rackham trees with goblins stirring at their roots. Those imaginary lands are as precious to me now as they were in my kithless, unmoored youth, and they formed me as much as any "real" place. They are real places. Or rather, I should say that they are true places, which is even better; and which, of course, is precisely why I able to take shelter inside them. Some kiths exist in the physical world, and some only in the imagination. But all of them are real. All of them matter. All of them place us, nourish us, and give us the stories we most need.

That's how it was for me for many years, until I crossed the ocean to Devon and, to my eternal surprise, its rain-drenched hills whispered in my ears: Welcome home. You've come at last. We've been waiting and waiting, and now you're here. Before, I'd found my home in the world only in the pages of certain books, and in the earth-colored tones of certain works of art: in Earthsea and Islandia, Rhyhope Wood and on the island of Hed, among Burne-Jones' briar roses and Arthur Rackham trees with goblins stirring at their roots. Those imaginary lands are as precious to me now as they were in my kithless, unmoored youth, and they formed me as much as any "real" place. They are real places. Or rather, I should say that they are true places, which is even better; and which, of course, is precisely why I able to take shelter inside them. Some kiths exist in the physical world, and some only in the imagination. But all of them are real. All of them matter. All of them place us, nourish us, and give us the stories we most need.

Now, as a writer and artist myself, my aim is to fashion, as Anais Nin once put it, "a world in which one can live"... out of words and paint, out of myth and life, out of rain, wind, earth and flame. I want to tell stories born of my love for Devon, but also for the Arizona desert and the lands I wandered during the homeless years: Narnia, Gramarye, Dorimare, Eldwold, Prydain, Dalemark, the Earthsea Archipelago, Vandarei, Tredana, the Old Kingdom, Dorn Island, and so many others. Most of all I, too, want to create landscapes and storyscapes so real, so vivid, so true that they might whisper in a weary traveler's ear:

Welcome home. You've come at last. We've been waiting and waiting, and now you're here.

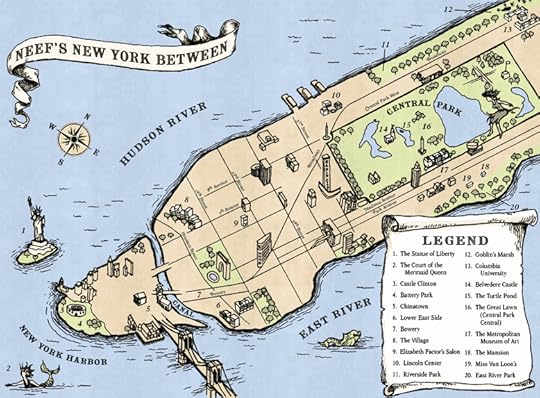

Map titles are in the picture captions. (Run your cursor over the images to see them.)

Map titles are in the picture captions. (Run your cursor over the images to see them.)

June 16, 2015

The hum

I'm working on a long post for tomorrow, so today, just an oak tree, Tilly, and this:

"Pythagoras considered that the sun, moon and planets all emitted a unique hum -- orbital resonance -- and that the quality of life on earth reflects the tenor of celestial sounds. The proportions, in the movements of the sun and moon and earth and other planets, are a form of music -- this is the ancient idea of the music of the spheres -- this music which is literally inaudible but a harmony nonetheless. A harmony of maths. A harmony of spirit. Listen very carefully and you won���t hear it.

"Boethius...thought that the music of the spheres had two corollaries, not just the music of singers and players but the music of the body. Listen very carefully and you might just perhaps hear the gentle hum of your animal body, the human purring-home in the bone-house."

- Jay Griffiths ("Hearth: A Thesaurus of Home")

Kissing the lion's nose

I'm going to stay with Jay Griffith's juicy book Kith: The of Childscape for two more posts, the first on subject of children and animals:

"That children love animals is a manifest truth," writes Griffiths, "and they also seek love from them. So crucial are animals to children's happiness that in a significant UNICEF study of childhood well-being children specified that pets were one of the top four most important things for their happiness. 'I want a kitten...a puppy...a horse,' children clamor for years, and this is perhaps only the most audible part of their love. Children talk wordlessly to their pets, taking a dog in their arms or, upset, burying their faces in a cat's fur and crying. They whisper secrets to their pets and feel understood by them. Children want to talk with the animals, eat with them, curl up with them and think with them, for children intuitively understand that animals are guides for the mind in metaphor-making."

"Children's authors, peopling their books with animals, know that children are fascinated by tales of crossing the species-fences, and the stories work carnally, suggesting a nuzzling sensuality, fostering a child's animal nature and answering a longing deep within children to be suckled by earthmilk, pressing their faces into the warm flank of horse, lion or wolf, breathing in the spicy messageful air of animals, falling asleep in their paws.

"Aslan. To run your fingers through his golden mane, to see 'the great, royal, solemn, overwhelming eyes,' to feel that humming, purring warmth and its ferocious power; 'whether it was more like playing with a thunderstorm or playing with a kitten,' the children cannot say. The writer Francis Spufford recalls a tender trespass of his childhood when he was suddenly seized with the desire for Aslan and reached his face up to a poster of the lion on his bedroom wall. Stealthily, heart-feltedly, he kissed the lion's nose. From early childhood, I remember that feeling, wanting to nudge myself into the musk and silage, the mushroom, rust and grass of an animal's den, wanting to know with my whole body the felt world of fur and pawpads and to feel the animal world in its fullness, its yawls, hackles and green-scent, to be batted by the paws of the furred earth, my senses drunk with it, living in the whiskey of animality. And to kiss the lion's nose.

"There's a fox in the garden. Those words would thrill us to the core. My brothers and I would crowd to the window in pressed silence, breathless, excited and honored that something so wild might bestow on us for a  flickering moment its feral presence. Birds and animals come into our lives as 'guests,' say Mohawk tales, and people must treat them well....

flickering moment its feral presence. Birds and animals come into our lives as 'guests,' say Mohawk tales, and people must treat them well....

"Animal-helpers snuffle in the hedges of fairy tales and they feather the tree-tops with bird-advice. In the nick of time, the winged lion or armored bear swerve into stories. If the fairy tale hero treats an animal kindly, it offers its skills, pecking out grain or tracking a scent beyond human guesswork.

"Creatures are friends to the psyche of a child. When Henry Old Coyote, from the Crow nation, was a boy, his grandfather would wake him early to listen to the birds and encouraged the child to know the exuberant joy of this bird medicine and to keep it inside him all day. I'm told that in Tamil Nadu, India, a child suffering nightmares may be cured by walking under an elephant's belly, being blessed by Ganesh. The nightmares, knowing better than to contend with an elephant, beat a retreat."

" 'In the old days the animals and the people were very much the same...They thought the same way and felt the same way. They understood each other,' says Simon Tookoome, an Inuit elder, recalling a belief common to many indigenous cultures. As a child, he adopted animals, including a caribou which followed him everywhere like a dog, and, at different times, five wolves."

"One strange peculiarity of modern childhood in the West is its estrangement from the animal world and the consequent silence of that world, its unmessaged, listless, speechless vacancy. Poet Gary Snyder speaks of the necessity to 'Bring up our children as part of the wildlife,' but the dominant culture treats wildlife as insignificant to children's happiness, which, as children themselves know, is a terrible oversight. Children's classics such as Anna Sewell's Black Beauty and Michael Morpurgo's mesmerizing War Horse touch the hearts of millions of children as they willingly listen to the experience of creatures other than human."

"Shape-shifting is an epistemology, a way for people to increase their sensitivities, to perceive the world with an imaginative leap, to feel through the body of another, metaphorically. Pueblo Indian children, from three years old, transform themselves into antelope and deer, they don fox skins, deer hooves or parrot feathers. In rituals and dances, through lyrics, choreography and costume, the child embodies earth-knowledge -- of corn and cloud, of sun and lightning, of buffalo and skunk -- and steps through the looking glass. Animal nature is another side of human nature, a mirror, by twilight, by twolight, where the twinnedness of those myths is reflected....

"Through a relationship with animals, we human add to the repertoire of our senses the beady alertness of a bird, the scent-subtlety of a mole, the smooth-swum escape of the fish. This the apprenticeship which children gleefully follow, given half a chance."

I certainly would have followed it as a child, being one of those kids with no interest in dolls, but who carried stuffed animals everywhere, in lieu of the real thing. And now as an adult, in my writing, art and life I've been making up for lost time ever since: seeking "the whiskey of animality," to use Jay Griffith's wonderful phrase, and kissing lion's noses. Or at least my dog's. Which is honestly just as good.

The images in this post are Elena Shumilova, who has become known around the world for her photographs of her sons and other children and animals on a farm in rural Russia. To see more of her lovely work, go here.

Related posts: Wild Neighbors, The Speech of Animals, "Word Magic, and The Animals That We Are."

Related posts: Wild Neighbors, The Speech of Animals, "Word Magic, and The Animals That We Are."

And some lovely recent news:

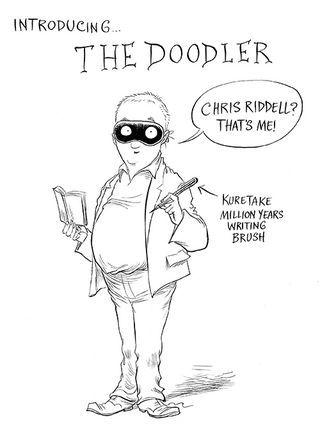

Author and artist Chris Riddell has

Author and artist Chris Riddell has

been named as the UK's new Children's Laureate. He is the country's ninth laureate, following Malorie Blackman. Blackman, during her term, was a staunch supporter of our country's libraries -- at a time when a disgraceful number of them have been closed or are under threat -- and Riddell has vowed to be the same, bless him.

"I am humbled to take on this role," he says," after the giants that have come before me. I want to put the joy of creativity, of drawing every day, of having a go and being surprised at what one can achieve with just a pencil and an idea at the heart of my term as Laureate. I want to make sure people have fun whilst addressing fundamental issues I care about passionately."

June 14, 2015

Tunes for a Monday Morning

It is so quiet on this misty June morning that I can hear the distant church bells ring, while the village in the green valley below our hill is slowly waking. Tilly, too, is sleepy this morning, gently snoring on the studio couch beside me....

In this hushed early morning atmosphere, only the right music will do; so I've chosen four sublime songs by Josienne Clarke & Ben Walker, the classically-trained folk duo from London. Walker plays guitar like an angel, and Clarke has been described as this generation's Sandy Denny -- although as much as I loved Denny's music I'd argue that Clarke's range is larger, stretching from Early Music to folk and beyond. (Go here for Clarke's cover of Denny's "Fotheringay," a song about Fotheringhay Castle, where Mary Queen of Scots was imprisoned.) Clarke & Walker's most recent album is Nothing Can Bring Back the Hour, and I highly recommend it.

First, Clarke & Walker's beautiful rendition of "Weep You No More Sad Fountains" by the English Renaissance composer John Dowland, performed at the Cecil Sharpe House in London.

Next, a traditional folk song: "The Banks of the Sweet Primroses." The video was filmed at the BBC Radio 2 Folk Music Awards earlier this year.

Third, a performance of "Tangled Tree," an original song by Clarke. The video was filmed for the Blue Room Sessions in the Netherlands.

And last, "Anyone But Me," performed at The Courtyard, a cross-genre music venue in London which pairs emerging artists with an in-house chamber orchestra and choir.

Have a good morning, and an inspired week.

For tunes about childhood, in honor of the discussions we've been having here in the last week, go here.

For tunes about childhood, in honor of the discussions we've been having here in the last week, go here.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers