Terri Windling's Blog, page 133

July 19, 2015

Tunes for a Monday Morning

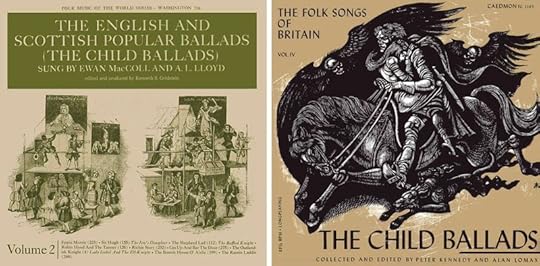

We're starting the week with a clutch of murderous, melancholy, and magical tunes from the British Isles, since after discussing the ballad collections of Francis James Child on Thursday and Friday, what else could we have but ballads this morning?

Above, Scottish singers Caorolyn Allan and Jenny Keldie sing "The Great Selkie of Sule Skerry," Child Ballad No. 113, and explain its meaning on the BBC programme "Scotland's Music, with Phil Cunningham." There are also many other fine recordings of this song, including "The Great Selchie" by American folk singer Judy Collins, "The Grey Silkie" by Scottish folk singer Jean Redpath, "The Great Selkie of Sule Skerry" by English folk singer June Tabor, "The Grey Selchie" by the Irish band Solas, and "The Great Selchie" by Breton harpist C��cile Corbel.

Below, Scottish singer Emily Smith performs "My Darling Boy," a variant of "The Trees Grow High." This classic ballad, I was surprised to learn, doesn't appear in the Child Ballad collections, but it is listed in the Roud Folk Song Index. Other good versions of the song include recordings by Joan Baez, Pentagle, Martin Carthy, and Bright Young Folk (John Boden & Fay Hield).

Next:

"Annachie Gordon," Child Ballad No. 239, performed by The Unthanks, featuring the smoky-voiced singers Rachel and Becky Unthank from Northumbria. Other versions include a classic rendition by the great Irish singer Mary Black, a version adapted for harp by Canadian musician and Celtic music scholar Loreena McKennitt, and a lovely performance of "Annachie" by former members of The Unthanks, Jackie Oates (Jim Moray's sister) & Belinda Hooley.

Fourth:

"Two Sisters," Child Ballad No. 10, sung by Emily Portman, from Glastonbury (audio only). There are many good versions of this song, including Pentangle's classic version "Cruel Sister," Emily Portman's "Twa Sisters," M��av N�� Mhaolchatha's "Wicked Sister," Clannad's "Two Sisters," Loreena McKennitt's "The Bonny Swans," Julie Fowlis' "Wind and Rain" (in Gaelic and English), "Wind and Rain" by the Irish band Altan, and "Wind and Rain" by the American band Crooked Still.

Fifth:

A contemporary take on "Lord Bateman," Child Ballad No. 53, from Jim Moray's lovely album Sweet England (audio only). There's are also gorgeous recordings of the song by Chris Wood, Susan McKeown, and The Askew Sisters, a traditional a cappella version sung by Arthur Knevett, and an Appalachian variant sung by Jean Ritchie.

Sixth:

A very contemporary take on "Lord Randall," Child Ballad No 12, by Roanoke, a new trio from Rome, Italy (Ilaria Paladino, vocals; Nicola Alianellos, guitar; Marcello Puggioni, percussion). For more traditional versions of the song, try Martin Carthy's classic English rendition, Jean Ritche's Appalachian rendition, and Emily Smith's variant, "Lord Donald."

(For another decidedly untraditional performance of a Child Ballad, see Sam Lee's strange and brilliant "The Ballad of George Collins," also known as "Clerk Covill," Child Ballad No. 42.)

And last:

"The Outlandish Knight" (also known as "Lady Isabel and the Elf Knight" and "May Colven"), Child Ballad No. 4, performed by Kate Rusby, from Yorkshire. In addition to the classic Nic Jones rendition (1970), there are also terrific versions by Emily Smith, Kadia, Sileas, and Jon Boden's exuberant band Bellowhead.

If you're up for a little more this morning, I recommend "Why aren't we all folk singers?" -- a TED talk by musician and folk music scholar Fay Hield.

Art by John William Waterhouse (1849-1917)

July 17, 2015

"Into the Woods" series, 41: The Child Ballads (Part II)

In the 1970s, while musicians were rediscovering and reinventing the genre of folk music, writers were rediscovering and reinventing the genre of fantasy fiction. The audience for both of these things overlapped. It���s not hard to understand why. Fantasy writers often work with themes that hark back to the oral tradition���to folktales, myths, and sagas steeped in the lore of our folk heritage. A number of writers who  came to the fantasy field in the late '70s and throughout the '80s -- which is when it solidified as a publishing genre -- were also folk musicians or singers (Ellen Kushner, Charles de Lint, Emma Bull, and Jane Yolen, among others); and music permeated their books. Charles de Lint���s The Little Country, for example, is set among folk musicians in Cornwall. Emma Bull���s War for the Oaks concerns folk-rock musicians in ���80s-era Minneapolis. Jane Yolen wove original ballads into Sister Light, Sister Dark and its sequels. Ellen Kushner retold a classic ballad in her novel Thomas the Rhymer, and created an anthology of magical stories about music, The Horns of Elfland, Other writers also turned to ballads for inspiration, fleshing out the bare bones of song narratives to turn them into stories and novels.

came to the fantasy field in the late '70s and throughout the '80s -- which is when it solidified as a publishing genre -- were also folk musicians or singers (Ellen Kushner, Charles de Lint, Emma Bull, and Jane Yolen, among others); and music permeated their books. Charles de Lint���s The Little Country, for example, is set among folk musicians in Cornwall. Emma Bull���s War for the Oaks concerns folk-rock musicians in ���80s-era Minneapolis. Jane Yolen wove original ballads into Sister Light, Sister Dark and its sequels. Ellen Kushner retold a classic ballad in her novel Thomas the Rhymer, and created an anthology of magical stories about music, The Horns of Elfland, Other writers also turned to ballads for inspiration, fleshing out the bare bones of song narratives to turn them into stories and novels.

One need only dip at random into the pages of Francis James Childs' The English and Scottish Popular Ballads to discover why this material would appeal to writers of magical fiction. There  you���ll find stories like ���Kemp Owyne,��� in which a young woman is turned into a loathsome dragon. Knight after knight comes to slay the beast. The dragon kills them all in turn, with tears of regret on her scaly cheeks. It is only when a knight puts down his sword and kisses her horrible face that the spell is broken and the dragon turns back into a beautiful maiden.

you���ll find stories like ���Kemp Owyne,��� in which a young woman is turned into a loathsome dragon. Knight after knight comes to slay the beast. The dragon kills them all in turn, with tears of regret on her scaly cheeks. It is only when a knight puts down his sword and kisses her horrible face that the spell is broken and the dragon turns back into a beautiful maiden.

In ���The Elfin Knight,��� a girl hears faery music and longs for a supernatural lover. The elf knight appears at her request, but gives her one look and tells her she���s too young. The song becomes a riddling song (similar to ���Parsley, Sage, Rosemary and Thyme���)���though this is a riddling match that is charged with distinctly sexual overtones.

In ���Reynardine,��� a mysterious man seduces a woman as she walks among the hills. The man is a shapechanger, a were-fox. We don���t know what he will do to her in the castle where he steals her away, but our last image of Reynardine is of his sharp teeth gleaming brightly in the twilight.

In ���Clark Sanders,��� seven brothers stand over their sleeping sister and her lover, discussing what they should do to this knight who has stained the family honor. Six of them agree that they should leave the sleeping couple alone, but the seventh takes out his sword and runs it through the  sleeping man���s heart. When the young woman wakes, she finds her love is a bloody corpse beside her. She goes mad with grief, the song ends . . . and then the story is taken up again in another ballad, called ���Sweet William���s Ghost.��� The spirit of the murdered man returns to the girl���s window. She begs him to kiss her, but he will not: ���My mouth it is full cold, Margaret, / It has the smell now of the ground; / And if I kiss thy comely mouth, / Thy days will not be long.���

sleeping man���s heart. When the young woman wakes, she finds her love is a bloody corpse beside her. She goes mad with grief, the song ends . . . and then the story is taken up again in another ballad, called ���Sweet William���s Ghost.��� The spirit of the murdered man returns to the girl���s window. She begs him to kiss her, but he will not: ���My mouth it is full cold, Margaret, / It has the smell now of the ground; / And if I kiss thy comely mouth, / Thy days will not be long.���

This idea that the dead may not touch the living is echoed in ���The Unquiet Grave.��� A maiden sits in a cemetery for twelve months, mourning her lover. Finally the spirit appears and asks, in a rather irritated manner, ���Who sits here crying and will not let me sleep?��� The maiden begs it for one kiss, but she is refused by the revenant: ���O lily, lily are my lips; / My breath comes earthy strong, / If you have one kiss of my clay-cold mouth, / Your time will not be long.���

Not all ballads in the British folk tradition concern magic, faery, or the supernatural. Other common themes are love (usually tragic), death (usually gruesome), and family troubles that make the soap operas of our own age pale by comparison: ���What is that blood on your sword, my son, what is that blood, my dear-o? It���s the blood of my sister, Mother, who I have killed in the greenwood-o. . . .��� (In this song, the brother is trying to avoid discovery of the fact that he���s made his sister pregnant.)

���What I like best about ballads,��� says novelist and short fiction writer Delia Sherman, ���is that they���re plots with all the motivations left out. Why did Young Randall���s stepmother want to poison him? Why choose eels? Why did Randall eat them (especially if they were green and yellow)? There���s a novel there, or at least a short story. Ballads give you classic human situations, and also some decidedly unclassic ones, exploring relationships between lovers, parents, and children, between friends, masters, and servants. Many of them deal with power and powerlessness, which is one of the central themes of fairy tales, too; but it seems to me that ballads are more pragmatic, more realistic, in their denouements. Not every villain gets his/her just deserts. I can imagine a ballad variant of ���Beauty and the Beast��� in which Beauty comes too late and sings a plaintive last verse over the Beast���s body, about how she will sew him a shroud of the linen fine and sit barefoot in the dark all her days, for the love of him she loved too late.���

Of all of the ballads recounted by Child, ���Tam Lin��� has captured the imagination of more fiction writers than any other single ballad, perhaps because of its sensual theme and unusual hero: an independent, courageous, stubborn young woman, pregnant with her woodland lover���s child, determined to save him from the Faery Queen and the unearthly Faery Court. Elizabeth Marie Pope���s classic novel The Perilous Gard set the tale in the courts of Elizabethan Scotland, while Pamela Dean���s Tam Lin used the ballad as the basis of a contemporary coming-of-age tale set among the theater students at a 1960s-era college campus. Alan Garner���s Red Shift -- a subtle, powerful, unforgettable reworking of the ballad���s themes -- rooted the tale in the landscape of northwest England during three inter-linked historical periods. Patricia A. McKillip set her ���Tam Lin��� novel, Winter Rose, in a land reminiscent of medieval England; she also used elements from the ballad ���Thomas the Rhymer��� to create a poetic and enchanting adult faery tale. Catherine Storr's too-little-known "Tam Lin" novel, Thursday, published in 1972, was one of the first to bring faery lore into the modern world. Dahlov Ipcar made interesting use of the ballad in her short novel for children, A Dark Horn Blowing, while Joan Vinge retold the ballad in a straight-forward manner in her lyrical story ���Tam Lin��� (from the anthology Imaginary Lands). Diana Wynne Jones, like McKillip, combined "Tam Lin" and ���Thomas the Rhymer��� in her excellent novel Fire and Hemlock, setting the tale among young classical musicians in modern-day England. An Earthly Knight by Janet McNaughton combined "Tam Lin" with the ballad "Lady Isabel and the Elf Knight" in vivid, darkly magical Young Adult novel set in 12th century Scotland. In addition to these, Liz Lochhead���s long, wry poem ���Tam Lin���s Lady��� (from her collection Dreaming Frankenstein) is well worth seeking out, as is Jane Yolen���s lovely picture book Tam Lin, illustrated by Charles Mikolaycak.

Of all of the ballads recounted by Child, ���Tam Lin��� has captured the imagination of more fiction writers than any other single ballad, perhaps because of its sensual theme and unusual hero: an independent, courageous, stubborn young woman, pregnant with her woodland lover���s child, determined to save him from the Faery Queen and the unearthly Faery Court. Elizabeth Marie Pope���s classic novel The Perilous Gard set the tale in the courts of Elizabethan Scotland, while Pamela Dean���s Tam Lin used the ballad as the basis of a contemporary coming-of-age tale set among the theater students at a 1960s-era college campus. Alan Garner���s Red Shift -- a subtle, powerful, unforgettable reworking of the ballad���s themes -- rooted the tale in the landscape of northwest England during three inter-linked historical periods. Patricia A. McKillip set her ���Tam Lin��� novel, Winter Rose, in a land reminiscent of medieval England; she also used elements from the ballad ���Thomas the Rhymer��� to create a poetic and enchanting adult faery tale. Catherine Storr's too-little-known "Tam Lin" novel, Thursday, published in 1972, was one of the first to bring faery lore into the modern world. Dahlov Ipcar made interesting use of the ballad in her short novel for children, A Dark Horn Blowing, while Joan Vinge retold the ballad in a straight-forward manner in her lyrical story ���Tam Lin��� (from the anthology Imaginary Lands). Diana Wynne Jones, like McKillip, combined "Tam Lin" and ���Thomas the Rhymer��� in her excellent novel Fire and Hemlock, setting the tale among young classical musicians in modern-day England. An Earthly Knight by Janet McNaughton combined "Tam Lin" with the ballad "Lady Isabel and the Elf Knight" in vivid, darkly magical Young Adult novel set in 12th century Scotland. In addition to these, Liz Lochhead���s long, wry poem ���Tam Lin���s Lady��� (from her collection Dreaming Frankenstein) is well worth seeking out, as is Jane Yolen���s lovely picture book Tam Lin, illustrated by Charles Mikolaycak.

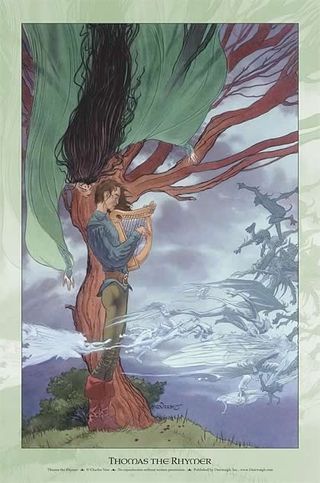

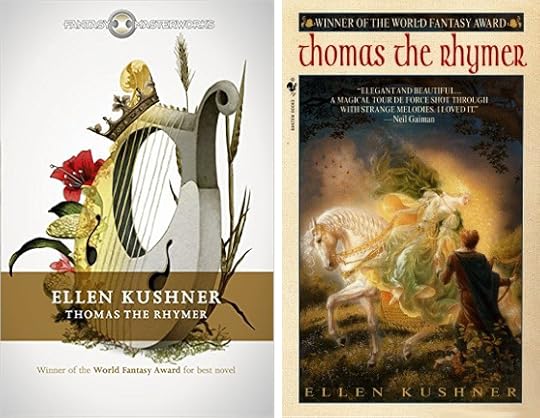

"Thomas the Rhymer" -- the story of a Scottish harper who kisses the Queen of Elfland and then is bound to her service for seven long years -- is another popular tale among fantasy writers and readers. In addition to the McKillip and Wynne Jones books listed above, the ballad inspired Bruce Glassco���s unusual short story ���True Thomas��� (from the anthology Black Swan, White Raven), and was splendidly retold in Ellen Kushner���s Thomas the Rhymer.

"I had to do Thomas," Ellen recalls, "because, like every other writer, I knew Thomas was my story. He holds the mythic power of King Arthur in the hearts of poets: the artist who is literally seduced by his muse, comes closer to her than any human should to the source of his art, and is profoundly changed. He can never be at  home in this world again, and yet he must continue to live in it. That���s how every writer feels, I think. Many writer friends had talked about writing a Thomas story someday, kind of like an actor playing King Lear: it���s a Great Subject that probably should not be tackled in one���s youth. I still feel a little humble about it. I don���t think I���ve written the definitive Thomas; I���ve just written my Thomas, the Thomas who addressed issues that were upon me in those years. Twenty years from now, I might like to do him again."

home in this world again, and yet he must continue to live in it. That���s how every writer feels, I think. Many writer friends had talked about writing a Thomas story someday, kind of like an actor playing King Lear: it���s a Great Subject that probably should not be tackled in one���s youth. I still feel a little humble about it. I don���t think I���ve written the definitive Thomas; I���ve just written my Thomas, the Thomas who addressed issues that were upon me in those years. Twenty years from now, I might like to do him again."

Ellen���s Thomas the Rhymer also drew upon the Child ballads ���The Trees They Do Grow High��� and ���The Famous Flower of Serving Men.��� The latter is the story of a woman whose husband, a knight, is murdered by her own mother. The heroine dons men���s clothes and goes to court, where the king soon falls in love with her���while the murdered knight returns as a white dove shedding blood-red tears through the forest. Delia Sherman used this ballad as the basis of her gender-bending novel Through a Brazen Mirror -- a very fine book that is still too little known.

���I heard Martin Carthy���s version of ���Famous Flower,��� ��� says Delia, ���and it haunted me with questions. If a mother so hated her child, why not just kill her and be done? Perhaps there was more to it than simple hatred. Another question prompted by the ballad had to do with the role of cross-dressing in a medieval culture. A third question could be stated as this: In all these  ballads with girls dressed as boys, the man falls in love with the boy, not the girl. What would happen if he wasn���t relieved to discover his beloved���s true sex? In short, ���Famous Flower��� gave me a beautiful, mysterious narrative framework upon which to hang all my favorite concerns: gender confusion, different kinds of love, the single-mindedness of the mad, foundlings and their origins.���

ballads with girls dressed as boys, the man falls in love with the boy, not the girl. What would happen if he wasn���t relieved to discover his beloved���s true sex? In short, ���Famous Flower��� gave me a beautiful, mysterious narrative framework upon which to hang all my favorite concerns: gender confusion, different kinds of love, the single-mindedness of the mad, foundlings and their origins.���

Patricia C. Wrede���s ���Cruel Sisters��� (from her collection Book of Enchantments) and Gregory Frost���s ���The Harp That Sang��� (from the anthology Swan Sister) are both memorable tales based on ���Cruel Sister��� (a.k.a. ���Twa Sisters���), the ghostly story of a murdered girl and a harp made out of bone. Midori Snyder���s wry urban fantasy story ���Alison Gross��� (from the anthology Life on the Border) is based on the ballad of that title about a man changed to an ugly worm when he spurns the kisses of a witch. A number of works draw upon ���The Grey Selchie,��� a poignant ballad of love and shape-shifting, including Jane Yolen���s ���The Grey Selchie��� (from her collection Neptune Rising), Laurie J. Marks���s ���How the Ocean Loved Margie��� (from The Journal of Mythic Arts, 2004), and Paul Brandon���s evocative, music-filled novel Swim the Moon. In Ghostriders, The Songcatcher, The Ballad of Frankie Silver, The Rosewood Casket, She Walks These Hills, The Hangman���s Beautiful Daughter, and If I Never Return Pretty Peggy-o, Sharyn McCrumb used the themes of traditional ballads from the south-eastern mountains of America to create mystery novels with more than a little magic around the edges. Greer Ilene Gilman���s Moonwise is a fever-dream of a novel brimming with Celtic balladry from every corner of the British Isles; Gilman has an extensive knowledge of the folk tradition and she worked with it here to unique effect.

Artist Charles Vess has listened to and loved old ballads for more than thirty-five years. ���They are great stories,��� he says, ���filled with exactly the things I love to draw best: magic, adventure, romance, suspense, historical settings, the lands of Faerie, and supernatural creatures that range from beautiful to hideous.���

In 1994, Charles conceived the idea of illustrating a series of comics based on traditional folk ballads. He spoke with a number of ballad-loving writers who promised him scripts for the new series, which began with a story by Charles de Lint retelling ���Sovay.��� The series was first published by Green Man Press, and then collected into a beautiful Tor Books edition, along with four additional tales, making thirteen ballad retellings in all -- by Neil Gaiman, Sharyn McCrumb, Midori Snyder, Lee Smith, Elaine Lee, Delia Sherman, Charles de Lint, Jeff Smith, and Emma Bull, plus two retellings by Jane Yolen, and one by Charles Vess himself. The Book of Ballads provides an excellent introduction to traditional ballads for readers not yet familiar with them, and a I highly recommend it.

In an article on Francis James Child published in Sing Out! magazine, Scott Alarik asked folk musician Martin Carthy (one of the greatest modern interpreters of Child ballads) why people should still be singing these ancient ballads today. For the same reasons they sang them long ago, Carthy answers. ���Because they���re fabulous stories; because they tell you immense amounts about people and how they treat each other, trick each other, cheat and chisel and love each other. There���s an extraordinary understanding of humanity in them.���

"You do have to sometimes kick the buggers into life," Carthy continues, "find them a tune, give the lyrics a kick here and there. And they can take it; they���re fabulously resilient. I really do believe there���s nothing you can do to these songs that will hurt them���except for not singing them.���

Contemporary folk musicians have been doing a fine job of ���kicking the buggers into life,��� and so have writers of fantasy fiction for children and adults. I've listed a few of my favorite ballad-inspired novels, stories, and graphic works here. Now, dear readers, I throw the subject over to you: What are some of your favorites?

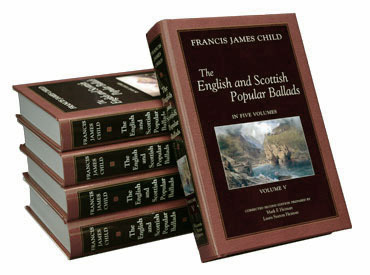

If you're interested in exploring this subject further, I recommend the following: The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, Vol. 1 - 5, by Francis James Child; The Singing Tradition of Child���s Popular Ballads by Betrand Harris Bronson; Bishop Percy���s Folio Manuscript, Ballads and Romances by John W. Hales & Frederick J. Furnivall; Medieval Lyric: Middle English Lyrics, Ballads, and Carols by John C. Hirsh; English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians by Cecil James Sharp; Earth, Air, Fire, Water: Pre-Christian and Pagan Elements in British Songs, Rhymes, and Ballads by Robin Skelton and Margaret Blackwood; Tales, Then and Now: More Folktales As Literary Fictions for Young Adults by Anna E. Altmann & Gail de Vos (which includes sections on fiction derived from "Tam Lin" and "Thomas the Rhymer"); and ���Child���s Garden of Verses: The Life Work of Francis James Child��� by Scott Alarik (Sing Out! Magazine, Vol. 46, #4). Two good articles on line: "Francis James Child's Ballads in the Modern Age" by Stephen D. Winick; and "Alan Garner's Red Shift and the Shifting Ballad of 'Tam Lin' " by Charles Butler.

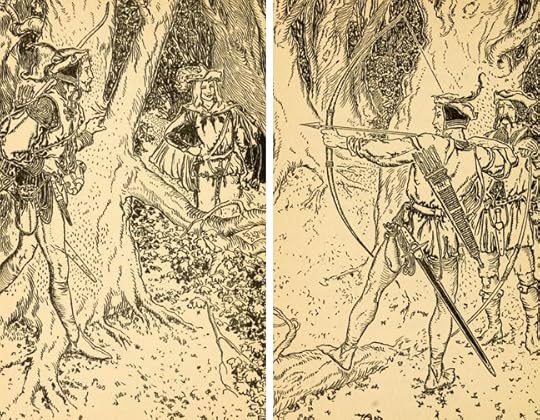

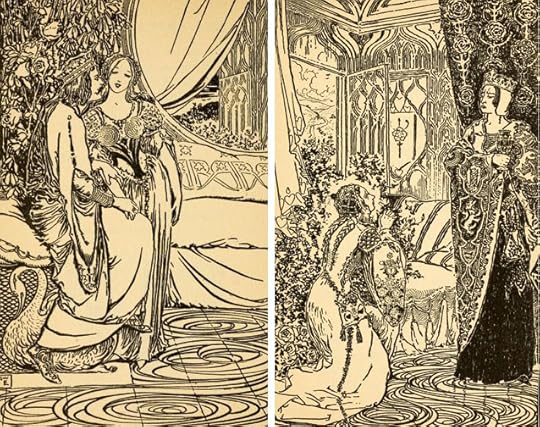

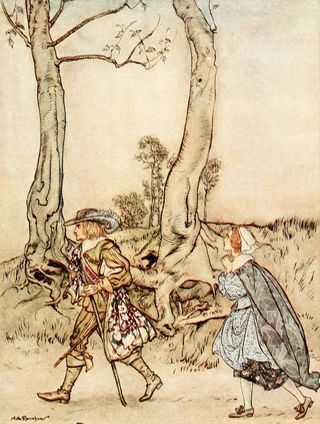

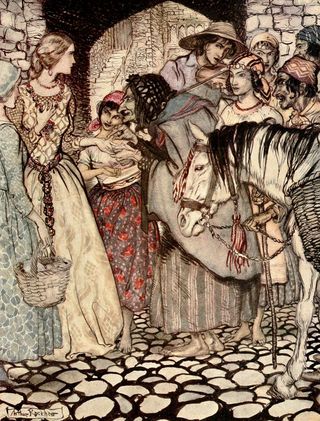

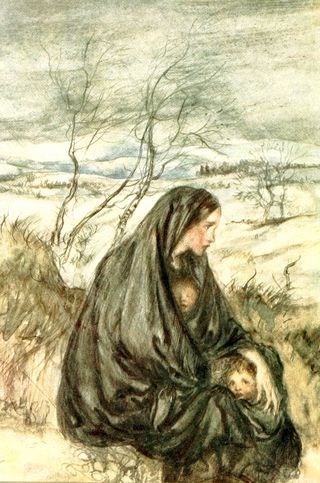

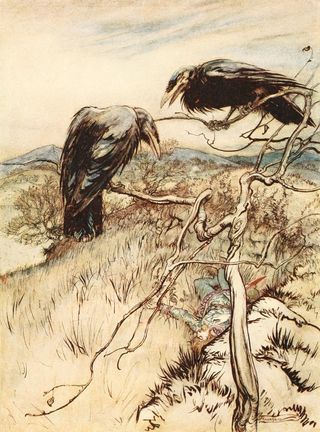

In the video above, Anais Mitchell and Jeffrey Hamer perform "Tam Lin," Child Ballad No. 39, from their album of Child Ballads (2013). The illustrations above are by Arthur Rackham

, from Some British Ballads (1918). The titles are in the picture captions; run your cursor over the images to see them.

July 16, 2015

"Into the Woods" series, 40: The Child Ballads (Part I)

The great folklorist Francis James Child defined what he called the ���popular ballad��� as a form of ancient folk poetry, composed anonymously within the oral tradition, bearing the clear stamp of the preliterate peoples of the British Isles. Ballads, which are stories in narrative verse, are related to folktales, romances, and sagas, with which they sometimes share themes, plots, and characters (such as Robin Hood). No one knows how old the oldest are. It���s believed that they are ancient indeed -- and yet we have few historical records of them older than the sixteenth century. Little is known for certain about how the oldest ballads would have been performed���but most likely they were recited, chanted, or sung without instrumentation. Right up to the twentieth century, ballads were traditionally sung a cappella, although today it is common to hear them accompanied by harp, guitar, fiddle, and other instruments.

Why do we have so few historical records? Because until relatively recently, they weren���t considered important enough to write down. With the rise of literacy, the songs and poems of Britian���s great oral tradition began to fall out of favor -- and ballads that had once been popular among all classes of society were now deemed primitive, pagan, the province of unlettered country folk. Because of this, few attempts were made to preserve ballads prior to the seventeenth century, and thus many were lost or were passed down through the years in fragmentary form. In the eighteenth century, ballad collection was still haphazard and sporadic, and the fruits of such labor were little regarded in academic circles. Universities did not yet consider folklore a respectable area of study, so manuscript collections remained in private hands, easily lost and forgotten.

In 1765, Bishop Thomas Percy came across one manuscript full of fine old ballads being used to light a kitchen fire. He saved them from the flames and published them in his book, Reliques of Ancient English Poetry. Percy���s book was a great success. It was much admired by such English Romantic writers as Coleridge, Southey, Shelley, and Keats, as well as German Romantics like Goethe, Tieck, and Novalis, and sparked much literary interest in the songs and legends of bygone days. Another fan of Percy���s book was the novelist Sir Walter Scott, who collected the ballads of his native Scotland in the early nineteenth century. Scott sat at the center of a circle of poets and antiquarians who were devotees (and romanticizers) of the ancient history of the British Isles. This group did much to popularize the old songs and tales of Scotland, England, and Ireland -- but still no British university would sponsor a proper academic collection of the country���s ballads.

That job fell to an American scholar, Francis James Child of Harvard University, who was urged to take on the subject by his frustrated British colleagues. Child hesitated, somewhat daunted by the immensity of the job at hand, and then he plunged in, devoting the rest of his life to the study of ballads. Beginning in the 1870s, Child set out to track down every extant version of every genuine popular ballad in the English and Scottish traditions. He limited himself to England and Scotland because the ballads of these countries overlapped, whereas Irish ballads were a separate tradition, requiring a depth of knowledge of Ireland���s language and history he didn���t possess. His goal was to publish the collected ballads with notes tracing their histories, relating them to songs and tales to be found in folklore the world over. The result of this remarkable labor was The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, published in five volumes between 1882 and 1898. It���s a work that���s still widely used today, revered by scholars and musicians alike.

That job fell to an American scholar, Francis James Child of Harvard University, who was urged to take on the subject by his frustrated British colleagues. Child hesitated, somewhat daunted by the immensity of the job at hand, and then he plunged in, devoting the rest of his life to the study of ballads. Beginning in the 1870s, Child set out to track down every extant version of every genuine popular ballad in the English and Scottish traditions. He limited himself to England and Scotland because the ballads of these countries overlapped, whereas Irish ballads were a separate tradition, requiring a depth of knowledge of Ireland���s language and history he didn���t possess. His goal was to publish the collected ballads with notes tracing their histories, relating them to songs and tales to be found in folklore the world over. The result of this remarkable labor was The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, published in five volumes between 1882 and 1898. It���s a work that���s still widely used today, revered by scholars and musicians alike.

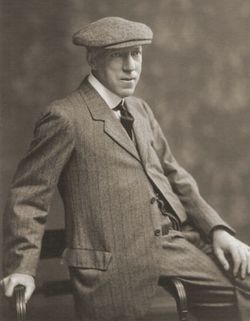

The life of the man behind these famous books is as interesting as the ballads he loved. Born the son of a sailmaker, Child grew up on the docks of Boston harbor -- until his aptitude for learning brought him to the attention of a distinguished Cambridge scholar. The boy was encouraged to transfer from his working-class school to Boston���s Latin School, after which he was sponsored at Harvard, where he graduated at the top of his class. Except for two years of study abroad, Child spent the rest of his life at Harvard, rising to become the first chairman of the newly created department of English. He built his substantial reputation on groundbreaking studies of Chaucer and Spenser, but he also had an abiding love for philology, ancient poetry, folklore, and fairy tales. The latter interests had been whetted during the two years Child spent in Germany, where he���d been exposed to the work of the folklore enthusiasts of the Heidelberg Circle of scholars, which included folk song collectors Clemens Brentano and Achim von Arnim, and the remarkable Brothers Grimm. The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, noted Child���s friend and colleague G. L. Kittredge, ���may even, in a very real sense, be regarded as the fruit of these years in Germany. Throughout his life he kept pictures of Wilhelm and Jacob Grimm on the mantel over his study fireplace.���

The life of the man behind these famous books is as interesting as the ballads he loved. Born the son of a sailmaker, Child grew up on the docks of Boston harbor -- until his aptitude for learning brought him to the attention of a distinguished Cambridge scholar. The boy was encouraged to transfer from his working-class school to Boston���s Latin School, after which he was sponsored at Harvard, where he graduated at the top of his class. Except for two years of study abroad, Child spent the rest of his life at Harvard, rising to become the first chairman of the newly created department of English. He built his substantial reputation on groundbreaking studies of Chaucer and Spenser, but he also had an abiding love for philology, ancient poetry, folklore, and fairy tales. The latter interests had been whetted during the two years Child spent in Germany, where he���d been exposed to the work of the folklore enthusiasts of the Heidelberg Circle of scholars, which included folk song collectors Clemens Brentano and Achim von Arnim, and the remarkable Brothers Grimm. The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, noted Child���s friend and colleague G. L. Kittredge, ���may even, in a very real sense, be regarded as the fruit of these years in Germany. Throughout his life he kept pictures of Wilhelm and Jacob Grimm on the mantel over his study fireplace.���

Child was a textual scholar rather than a field collector, and he put his massive ballad compilation together by seeking out every manuscript copy of ballad material he could lay his hands on, with the help of a small army of fellow scholars searching out songs and fragments of songs throughout the British Isles. Another reason he depended on manuscripts rather than the memories of folk  musicians was that the British popular ballad, in his view, was no longer a living tradition. The ballads he sought were the ancient ones -- not the ���broadside ballads��� that dominated the nineteenth-century folk musician���s repertoire. Broadsheet ballads were authored song lyrics designed to fit traditional tunes, cheaply printed and sold for pennies on street corners from the sixteenth century onward. These were contemporary compositions, rather than ancient poetry from the oral tradition -- though sometimes broadside ballads mimicked the language of much older songs, and determining which was which was a problem Professor Child was both intrigued and vexed by.

musicians was that the British popular ballad, in his view, was no longer a living tradition. The ballads he sought were the ancient ones -- not the ���broadside ballads��� that dominated the nineteenth-century folk musician���s repertoire. Broadsheet ballads were authored song lyrics designed to fit traditional tunes, cheaply printed and sold for pennies on street corners from the sixteenth century onward. These were contemporary compositions, rather than ancient poetry from the oral tradition -- though sometimes broadside ballads mimicked the language of much older songs, and determining which was which was a problem Professor Child was both intrigued and vexed by.

To the dismay of this meticulous scholar, in the absence of clear historical records he was often forced to depend on textual clues and his own best judgment. Fortunately, that judgment was finely honed by his fluency in archaic languages, and his extraordinary knowledge of folklore traditions the world over. He chose, he explained in a letter to a friend, to err on the side of inclusiveness. Where he had lingering doubts about the authenticity of a song variant, he was apt to  include it anyway, along with notes outlining his reservations. His task was greatly complicated by the fact that the ballads of Britain had been so badly recorded and preserved compared with those of other countries such as Denmark. ���The ballads should have been collected as early as 1600,��� he noted sadly; ���then there would have been such a nice crop; the aftermath is very weedy.��� Another complication was that ballads written down and published from the eighteenth century onward had been edited, censored, or ���improved��� by folklore enthusiasts who were literary men, romantics, rather than rigorous academics. The prime example of this was Percy���s famous Reliques of Ancient English Poetry. Child and other folklorists suspected that Percy had altered the text of ballads to suit the literary tastes of his day -- particularly as Percy would not allow an examination of the ballad manuscript in his possession. Working with British scholar F. J. Furnivall, Child was instrumental in persuading Percy���s descendants to finally release this manuscript, which did ideed confirm that Percy had edited and ���improved��� the original ballads.

include it anyway, along with notes outlining his reservations. His task was greatly complicated by the fact that the ballads of Britain had been so badly recorded and preserved compared with those of other countries such as Denmark. ���The ballads should have been collected as early as 1600,��� he noted sadly; ���then there would have been such a nice crop; the aftermath is very weedy.��� Another complication was that ballads written down and published from the eighteenth century onward had been edited, censored, or ���improved��� by folklore enthusiasts who were literary men, romantics, rather than rigorous academics. The prime example of this was Percy���s famous Reliques of Ancient English Poetry. Child and other folklorists suspected that Percy had altered the text of ballads to suit the literary tastes of his day -- particularly as Percy would not allow an examination of the ballad manuscript in his possession. Working with British scholar F. J. Furnivall, Child was instrumental in persuading Percy���s descendants to finally release this manuscript, which did ideed confirm that Percy had edited and ���improved��� the original ballads.

Sifting through the mountain of material he collected, sniffing out alterations and forgeries, Child amassed a group of 305 songs with their roots in the oral tradition, along with variants of each song, sometimes in dozens of alternate versions. The final volume of The English and Scottish Popular Ballads was completed the  year of Child���s death, but he died before writing the book���s introduction, which would have explained his method of selection and given us an overview of his work. Yet even without this, The English and Scottish Popular Ballads was hailed by critics on both sides of the Atlantic and became a cornerstone of modern folklore scholarship. In addition, Child was instrumental in establishing the American Folklore Society, serving as its first president from 1888 to 1889. But sadly, Child did not live to see that movement flower in subsequent years, and he died doubting his work had relevance to a modern age. ���If he���d lived just a little longer,��� says Mark F. Heiman of Loomis House, which published a handsome new edition of The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, ���he would have seen the golden age of the ballad collector and folklorist. He would have seen how important his life���s work really was.���

year of Child���s death, but he died before writing the book���s introduction, which would have explained his method of selection and given us an overview of his work. Yet even without this, The English and Scottish Popular Ballads was hailed by critics on both sides of the Atlantic and became a cornerstone of modern folklore scholarship. In addition, Child was instrumental in establishing the American Folklore Society, serving as its first president from 1888 to 1889. But sadly, Child did not live to see that movement flower in subsequent years, and he died doubting his work had relevance to a modern age. ���If he���d lived just a little longer,��� says Mark F. Heiman of Loomis House, which published a handsome new edition of The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, ���he would have seen the golden age of the ballad collector and folklorist. He would have seen how important his life���s work really was.���

Child���s work went on to inspire a whole new generation of folklorists, men and women who weren���t quite so convinced that the oral tradition was irretrievably dead and gone. One of them was Cecil Sharp, who began collecting English folk songs and dance tunes in the early years of the twentieth century. Sharp was a trained musician, and unlike Child he was also interested in preserving the music of the ballad tradition, rather than viewing ballads primarily as poetry. He noted that the Child ballads were rarely part of the repertoire of the elderly singers he listened to in the countryside; they���d been replaced by broadside ballads and other more recent songs. Sharp wondered if the older ballads might have survived among the British and Scottish settlers in America, particularly among the descendants of settlers in isolated mountain regions, where ���pennysheets��� of modern ballads would not have been available. Between 1914 and 1918, Sharp made two extensive trips through the Appalachian Mountains, collecting over a thousand songs with the aid of his secretary, Maud Karpeles. Sharp and Karpeles discovered that many of the Child ballads were indeed still known and performed in Appalachia, although sometimes the titles and lyrics had changed somewhat in this new setting. Sharp published these ballads in his now-classic English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians, which in turn inspired new folklore studies and new collection efforts throughout the United States.

Child���s work went on to inspire a whole new generation of folklorists, men and women who weren���t quite so convinced that the oral tradition was irretrievably dead and gone. One of them was Cecil Sharp, who began collecting English folk songs and dance tunes in the early years of the twentieth century. Sharp was a trained musician, and unlike Child he was also interested in preserving the music of the ballad tradition, rather than viewing ballads primarily as poetry. He noted that the Child ballads were rarely part of the repertoire of the elderly singers he listened to in the countryside; they���d been replaced by broadside ballads and other more recent songs. Sharp wondered if the older ballads might have survived among the British and Scottish settlers in America, particularly among the descendants of settlers in isolated mountain regions, where ���pennysheets��� of modern ballads would not have been available. Between 1914 and 1918, Sharp made two extensive trips through the Appalachian Mountains, collecting over a thousand songs with the aid of his secretary, Maud Karpeles. Sharp and Karpeles discovered that many of the Child ballads were indeed still known and performed in Appalachia, although sometimes the titles and lyrics had changed somewhat in this new setting. Sharp published these ballads in his now-classic English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians, which in turn inspired new folklore studies and new collection efforts throughout the United States.

Despite the keen interest of folklorists, ballads remained a specialized interest for much of the twentieth century, until the huge folk music revival of the 1960s and ���70s. In those years, Joan Baez, Judy Collins, and other singers recorded ballads from the Child collections, and a Celtic music revival exploded across the British Isles, Brittany, and America. Folk-rock bands like Pentangle, Fairport Convention, and Steeleye Span updated the ballads for a new generation, while singers like Martin Carthy, Frankie Armstrong, Jean Redpath, and June Tabor created an audience for traditional music played in more traditional ways.

Today, that revival is still going strong, with Child ballads performed by Karine Polwart, Kate Rusby, Eliza Carthy, Sam Lee, Josienne Clarke, Jim Moray, Fay Hield & The Hurricane Party, The Imagined Village, Loreena McKennit, and many, many others. (You'll find an online discography here). I particularly recommend Ana��s Mitchell & Jefferson Hamer's terrific album dedicated to Child Ballads, and Jon Boden's Folk Song A Day site.To dig further into this subject, you'll find a lot of good material in the digital archives of the English Folk Song & Dance Society.

I'm going to end today with Mitchell & Hamer performing "Willie's Lady," which is Child Ballad No. 6. Tomorrow, in Part II of this post, we'll look at the ways that writers of fantasy literature have made use of ballad material.

The illustrations above are by George Wharton Edwards, from A Book of Old English Ballads (1896); the titles are in the picture captions. Text for this post was taken from an article I wrote, years ago, for Fantasy Magazine, and from my Introduction to The Book of Ballads by Charles Vess. (More on the latter tomorrow.)

July 15, 2015

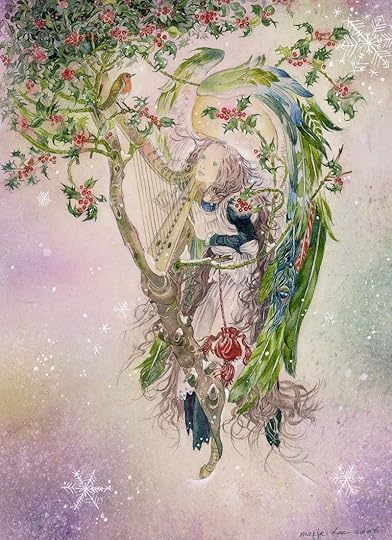

"Into the Woods" series, 39: The Enchanted Harp

A tale from Scotland's Isle of Skye relates how music first came to those lands. A poor youth found a strange instrument (a triangular harp) floating in the waves. He fished it out, set it upright, and the wind began to play the strings -- an eerie, lovely sound the like of which had never been heard. The boy could not duplicate the sound, although he tried for many long days. So obsessed did he become that his widowed mother ran to a wizard (a dubh-sgoilear) to beg him to give her son the skill to play the instrument -- or else to quell his desire  for it. The dubh-sgoilear offered her this choice: he would take away the boy's desire in exchange for the widow's body, or he'd give him the gift of music in exchange for her mortal soul. She chose the later and returned home where she found her son plucking beautiful, heavenly music from the strings of the harp. But the boy was horrified to learn the price his mother had paid for his skill. From that moment on, he began to play music so sad that the birds and the fish stopped to listen. And that, concludes the old Scottish tale, is why the music of the harp sounds poignant to this very day.

for it. The dubh-sgoilear offered her this choice: he would take away the boy's desire in exchange for the widow's body, or he'd give him the gift of music in exchange for her mortal soul. She chose the later and returned home where she found her son plucking beautiful, heavenly music from the strings of the harp. But the boy was horrified to learn the price his mother had paid for his skill. From that moment on, he began to play music so sad that the birds and the fish stopped to listen. And that, concludes the old Scottish tale, is why the music of the harp sounds poignant to this very day.

From Ireland comes another tale about the earliest harp music: Boand was the wife of the Dagda Mor, a deity of the Tuatha De Danann (the faery race of Ireland). As Boand gave birth to the Dagda's three sons, the Dagda's harper played along to ease the woman's labor. The harp groaned with the intensity of the pain as the woman's first child emerged, and so she named her eldest son Goltrai, the crying music. The music made a merry sound as Boand's second son was born, and so she named the child Gentrai, the laughing music. At last the final infant emerged to music that was soft and sweet. She called the child Suantri, the sleeping (or healing) music. These three strains of music are still found in the repertoire of Celtic musicians -- as echoed by the Scots-English ballad recounting the trials of King Orfeo (a harper in the oldest songs, a fiddler in later variants) who played three strains of music before the king of the faery underworld: the notes of joy, the notes of pain, and the enchanted faery reel.

It is interesting to note that the modern revival of interest in traditional folk music, beginning in the 1970s, paralleled the modern revival of interest in fantasy fiction (and the birth of the fantasy publishing genre in the same decade). It is not surprising that the audiences for folk music and fantasy stories overlap, for both art forms are rooted in the lore and legends of our folk heritage. Today, you'll find quite a number of fantasy novels and stories infused with folk music and traditional ballads. Bards and wandering minstrels have long been staple characters in books set in medieval or imaginary lands, and more often than not, a small, hand-held, Celtic style harp is the instrument they play. The quick-witted Morgan of Hed in Patricia McKillip's "Riddlemaster" books, for example, was one of the first (and remains one of the best) harp-toting protagonists in contemporary fantasy fiction. Patricia C. Wrede (The Harp of Imach Thysell), Morgan Llewelyn (Bard), Charles de Lint (Moonheart) and other writers from early days of the fantasy genre created memorable bardic characters, and Ellen Kushner told the quintessential harper tale in her award-winning, balllad-inspired novel, Thomas the Rhymer.

It is interesting to note that the modern revival of interest in traditional folk music, beginning in the 1970s, paralleled the modern revival of interest in fantasy fiction (and the birth of the fantasy publishing genre in the same decade). It is not surprising that the audiences for folk music and fantasy stories overlap, for both art forms are rooted in the lore and legends of our folk heritage. Today, you'll find quite a number of fantasy novels and stories infused with folk music and traditional ballads. Bards and wandering minstrels have long been staple characters in books set in medieval or imaginary lands, and more often than not, a small, hand-held, Celtic style harp is the instrument they play. The quick-witted Morgan of Hed in Patricia McKillip's "Riddlemaster" books, for example, was one of the first (and remains one of the best) harp-toting protagonists in contemporary fantasy fiction. Patricia C. Wrede (The Harp of Imach Thysell), Morgan Llewelyn (Bard), Charles de Lint (Moonheart) and other writers from early days of the fantasy genre created memorable bardic characters, and Ellen Kushner told the quintessential harper tale in her award-winning, balllad-inspired novel, Thomas the Rhymer.

It's not difficult to see why the harp became the instrument of choice in fantasy literature, for it is one that has always been associated with magic. The earliest harps of western Europe were most often made of willow wood, a tree sacred to the Goddess, associated with the cycles of the moon, fertility, and enchantment. The strings of the harp symbolize the mystic bridge between heaven and earth; mankind stands poised in the middle, striving now toward one and now toward the other as represented by the tension of the strings (portrayed in Bosch's painting "The Garden of Delights," where a man hangs from the strings, crucified). The harp has been associated with early pagan religions, its music called "the voice of the gods," although it was later absorbed into the Christian church and the celestial choir.

It was thought that the harp as we know it today originally came from Ireland, spreading across Scotland and Wales and over the Channel to Europe. But in 1992 the music historians Keith Sanger & Alison Kinnaird published Tree of Strings: Crann Nan Tued, a thorough, well-written history of the harp, presenting strong archaeological evidence that the earliest instruments came from Scotland. (The harp is found carved onto Picto-Scottish stones at least 200 to 300 years earlier than pictorial representations elsewhere in the world.) According to Sanger & Kinnaird, these large, floor-standing instruments (triangular in frame, probably strung  with horsehair) passed to Wales sometime between the 6th and 9th centuries during waves of immigration from the north, while the Irish are likely to have come into contact with the harp through their religious communities established in the west of Scotland. When the Irish brought the instrument home, they altered the shape and gave it metal strings. This is the harp we know today as the Gaelic harp or clarsach.

with horsehair) passed to Wales sometime between the 6th and 9th centuries during waves of immigration from the north, while the Irish are likely to have come into contact with the harp through their religious communities established in the west of Scotland. When the Irish brought the instrument home, they altered the shape and gave it metal strings. This is the harp we know today as the Gaelic harp or clarsach.

Sanger & Kinnaird point out that it's not entirely accurate to call the harp a "folk" instrument. For many centuries the harp firmly belonged to the aristocracy; it was not an instrument to be found (like the fiddle and whistle) in a poor man's croft. Harpers were trained and educated; they were esteemed (and esteemed themselves) quite highly compared to other musicians. For common people, the opportunity to hear the music of the harp was rare indeed. In Scandinavia, harps were noble instruments by law; a commoner who dared to play the harp could find himself sentenced to death. This gave the instrument a powerful aura of otherworldliness, surrounding harp music with magical legends and supernatural associations. The ancient Volsunga Saga recounts the death of Gunnar, brother to Sigurd the Dragon-slayer. Thrown into a pit of poisonous snakes by vengeful enemies, Gunnar kept death at bay  by playing a mystical song upon his harp, enchanting the serpents to sleep. For an entire day and night he played, but as the dawn broke over the land his tired fingers fumbled and one snake sunk its poison into Gunnar's hand.

by playing a mystical song upon his harp, enchanting the serpents to sleep. For an entire day and night he played, but as the dawn broke over the land his tired fingers fumbled and one snake sunk its poison into Gunnar's hand.

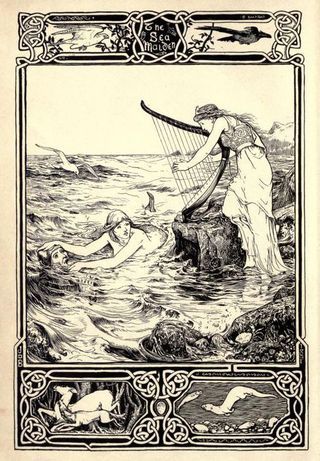

We find other magical harps in countless fairy tales, epic poems, and songs. In a Swedish tale, a young hunter saves his wife from the lust of an arrogant prince by invoking the aid of her wolf-relatives to build him a harp -- a magical harp with which to gain her freedom. In a poem from Iceland (also a ballad from Scotland) one sister drowns another in order to steal the drowning girl's fiance. The body eventually floats to land, where a minstrel makes a harp from the girl's breast bone, strung with her golden hair. When he plays for the murderous sister's wedding, the harp speaks with the dead girl's voice and exposes the bride's treachery. The Scottish harper Glenkindie (like the fiddler Jack Orion) could "harp the fish out of the salt sea, or water out of a stone, or milk out of a maiden's breast though baby had she none." He plays a sleeping spell in order to seduce the daughter in a great lord's hall, but his serving man, in pursuit of the same woman, harps Glenkindie to sleep in turn and steals the maiden away for himself. The sinister Elf Knight uses a similar trick to seduce the Lady Isobel -- but she is a quick-witted young woman and escapes the encounter with her maidenhead intact. Thomas the Rhymer is the most famous harper of Scottish balladry. The Queen of Faery (known to have a fancy for handsome mortal musicians) seduces Thomas and steals him away to Faerieland for seven years. When she sends him home again, it is with the gift (or the curse) of "the tongue that cannot lie."

In Arthurian romance, Tristan disguises himself as a wandering harper when he travels from Cornwall to Ireland, seeking the cure for a poisonous wound inflicted by an Irish hero. It is there he encounters the fair Iseult and determines to win her for his Cornish king, never dreaming that he will come to love her himself, and thereby seal his doom. In Russia, the harp was known as a gusla, the wandering harpist as a guslar. One legend tells of a Tsar who is captured while travelling in the Holy Lands. His brave Tsarita dons men's clothes,  takes up her gusla, and follows his path. Playing before the infidel king, she wins her husband's freedom. The guslars of Russia are comparable to the bards to be found in Celtic lands: trained in archaic poetic modes, severe and highly formal, which were performed as sung recitations while accompanied by the harp. In the British Isles, in ancient times, the bards were held in the highest esteem. They were scholars, historians, genealogists, valued advisors to nobles and kings, and believed to possess certain magical powers; their satires could curse, even kill a man, while their poems of praise lifted fortunes. In Ireland, the fili (a hereditary position requiring at least six years of training in one of the poetic colleges) composed poetry but did not perform it; the reacaire would chant or recite with musical accompaniment from a harper. In Scotland, these three separate positions came together in the person of the bard. While not quite as highly trained as the fili, he nonetheless composed poetry himself, performed, and generally played his own harp.

takes up her gusla, and follows his path. Playing before the infidel king, she wins her husband's freedom. The guslars of Russia are comparable to the bards to be found in Celtic lands: trained in archaic poetic modes, severe and highly formal, which were performed as sung recitations while accompanied by the harp. In the British Isles, in ancient times, the bards were held in the highest esteem. They were scholars, historians, genealogists, valued advisors to nobles and kings, and believed to possess certain magical powers; their satires could curse, even kill a man, while their poems of praise lifted fortunes. In Ireland, the fili (a hereditary position requiring at least six years of training in one of the poetic colleges) composed poetry but did not perform it; the reacaire would chant or recite with musical accompaniment from a harper. In Scotland, these three separate positions came together in the person of the bard. While not quite as highly trained as the fili, he nonetheless composed poetry himself, performed, and generally played his own harp.

Until the 15th and 16th centuries fili and bard used formal syllabic verse. When "amhran" apppeared (one of the basic meters of folk poetry), it swept across Europe and the British Isles, carried by traveling troubadours. As the strict rules of poetry became more relaxed, the role of fili began to disappear -- sped by the political events undermining the Irish and  Highland Scottish social structures. In the early 17th century, the Irish poetic colleges collapsed; in Scotland, the less strict bardic training survived another hundred years. After this, harpers began to take on roles that combined those of the fili and the wandering troubadours. Their status fluctuated, then fell drastically. The British Crown considered traveling harpers to be political subversives; Queen Elisabeth I turned the bards into outlaws, uttering her famous proclamation: "Hang the harpers wherever found." Cromwell joined in by enacted a vicious harp-breaking policy. By the time of the famous 1792 gathering of harpers in Belfast, the proud old profession of bard was virtually extinct; wandering harpers were generally poor men with no alternative means of support -- like the famous blind harper O'Carolan, whose music is still played by harpers today.

Highland Scottish social structures. In the early 17th century, the Irish poetic colleges collapsed; in Scotland, the less strict bardic training survived another hundred years. After this, harpers began to take on roles that combined those of the fili and the wandering troubadours. Their status fluctuated, then fell drastically. The British Crown considered traveling harpers to be political subversives; Queen Elisabeth I turned the bards into outlaws, uttering her famous proclamation: "Hang the harpers wherever found." Cromwell joined in by enacted a vicious harp-breaking policy. By the time of the famous 1792 gathering of harpers in Belfast, the proud old profession of bard was virtually extinct; wandering harpers were generally poor men with no alternative means of support -- like the famous blind harper O'Carolan, whose music is still played by harpers today.

In the early 1800s, harp music and its attendant folklore underwent a public revival, aided by the efforts of the Dublin poet-musician Thomas Moore. Moore wrote poems to Irish folk tunes and published them with tremendous success; his popularity rivalled Byron's and Scott's during his day, and his songs are still sung. In 1810, modern mechanization allowed a new type of harp to be patented which permitted musicians to play in all musical keys. This brought the harp back into classical orchestras and unleashed a flood of new music. The harp become a popular parlor instrument -- particularly among genteel young ladies, who, it was claimed, enjoyed the excuse to flash their slim ankles to admirers.

Even in the area of classical music, the harp had an aura of magic and enchantment. The Victorians, with their strong interest in folklore, spiritualism and the Celtic Twilight, embraced the music of the harp with a fervor that is almost hard to imagine today. A wealth of Victorian "fairy music" for the harp was written, published and performed -- music which eventually fell out of fashion along with the mystical medievalism and Arthurianism of the Pre-Raphaelites, the spiritualism and florid fantasies characterizing the age. Despite its great popularity during its day, the existence of this 19th-century fairy music was nearly forgotten altogether until English harp player Elizabeth-Jane Baldry released her lovely CD, Harp of Wild and Dreamlike Strain: Romantic Victorian Harp Music."

Even in the area of classical music, the harp had an aura of magic and enchantment. The Victorians, with their strong interest in folklore, spiritualism and the Celtic Twilight, embraced the music of the harp with a fervor that is almost hard to imagine today. A wealth of Victorian "fairy music" for the harp was written, published and performed -- music which eventually fell out of fashion along with the mystical medievalism and Arthurianism of the Pre-Raphaelites, the spiritualism and florid fantasies characterizing the age. Despite its great popularity during its day, the existence of this 19th-century fairy music was nearly forgotten altogether until English harp player Elizabeth-Jane Baldry released her lovely CD, Harp of Wild and Dreamlike Strain: Romantic Victorian Harp Music."

Elizabeth-Jane is an old friend and neighbor of mine, living in tiny, magical cottage crowded with harps and books and Pre-Raphaelite prints and movie-making equipment. (She also runs the Chagford Filmmaking Group.) As a harp teacher as well as a performer and composer, she is largely responsible for the fact that there are few places one can walk in the village without hearing someone, somewhere, practicing classical or Celtic harp. With her long dark hair and long skirts she might have stepped from a Rossetti painting herself, and her breadth of knowledge about Victorian culture (and harp music in general) is impressive.

"The fairy music on Harp of Wild and Dreamlike Strain," she says, "is the result of a journey into the Victorian fascination with the transcendental. All the music has lain forgotten in the vast archives of the British Library, and has never before been recorded or even performed in modern times. Its composers, once famous touring virtuosi, are now long dead and forgotten. Most compelling was the discovery that so many elements of the Victorian psyche are distilled in the music: a revolt against Darwinism and the birth of the scientific age, the spectacular rise of the spiritualist movement affecting even the Royal Court, a nostalgia for our rural past as the industrial revolution  tightened its hold, and the rise of the middle classes with their demand for accessible music. Furthermore, the Victorian love affair with Scotland contributed to the popularity of the harp, Scotland's oldest national instrument. There was an interest for the first time in our folk heritage. The erotic imagery of fairies was an obvious outlet for the repressed sexuality of the time. Orgiastic paintings of naked frolics became respectable provided the participants had wings! Fairy music for the harp is the essence of Victorian idealism."

tightened its hold, and the rise of the middle classes with their demand for accessible music. Furthermore, the Victorian love affair with Scotland contributed to the popularity of the harp, Scotland's oldest national instrument. There was an interest for the first time in our folk heritage. The erotic imagery of fairies was an obvious outlet for the repressed sexuality of the time. Orgiastic paintings of naked frolics became respectable provided the participants had wings! Fairy music for the harp is the essence of Victorian idealism."

Elizabeth-Jane unearthed this cache of Victorian fairy music while doing research at the British Library in London. Amazed by both the quantity and the quality of this music, she swiftly made plans to put together a recording of selections from this work. Her CD was recorded on location in the 19th-century ballroom of Buckland Manor: an eighty-five-room country manor house, virtually empty, rising from the Devon countryside like the house in a gothic romance. "As I played," she recalls, "looking out on a hundred acres of untouched parkland on a golden autumn day, the wind gusting, empty urns filled with blown leaves, I felt goose-shivers down my spine . . . knowing this music hadn't been played in a century. The last time it had been performed, the manor's ballroom had just been built."

As she played the rippling notes of "Ondine," a reverie for harp by Georgio Lorenzi (inspired by Baron de la Motte Fouque's tragic story of a  knight and a water-spirit), Elizabeth-Jne heard a distant scream. The recording engineers heard it too and the sound was captured upon the tape. And yet, when investigated, no source for the scream could be found in that empty place. Only later did she discover that a Victorian woman had met her death in that very room, thrown from the balcony by a husband enraged by "extravagant spending."

knight and a water-spirit), Elizabeth-Jne heard a distant scream. The recording engineers heard it too and the sound was captured upon the tape. And yet, when investigated, no source for the scream could be found in that empty place. Only later did she discover that a Victorian woman had met her death in that very room, thrown from the balcony by a husband enraged by "extravagant spending."

The late 20th century revival of interest in harp music was, like the earlier Victorian revival, entwined with an interest in all things folkloric, fantastic and mystical. I was fortunate to be a student in Dublin in the mid-1970s, when the contemporary Celtic music renaissance was first building up its steam -- a thrilling time to see new bands like Clannad adapt the Celtic harp to a new Celtic sound, or to catch sight of The Chieftain's legendary harper Derek Bell in the smokey rooms of an old Dublin pub. The Breton harper Alan Stivell began to build a following about the same time, influencing many of the younger musicians who followed after. Stivell's Renaissance de la Harpe Celtique" is a CD that tops the list of recommendations for anyone interested in Celtic harp music.

There are so many fine harpists working today that it's impossible to list them all here, but any survey of the field should certainly also include Derek Bell, Patrick Ball, Dominig Bouchaud, Robin Huw Bowen, C��cile Corbel, Paul Dooley, Loreena McKennitt, ��ine Minogue, Joanna Newsom, Maire Ni Chathsaigh, Nansi Richards, Kim Robertson, Sileas (Patsy Seddon & Mary Macmaster), Savourna Stevenson, and Robin Williamson. (Despite the proponderence of women harpists today, it should be noted that in the past women harpers were rare, often dismissed and slandered as "loose-living" women. In the Dark Ages it was strictly against the law for women to harp.)

There are so many fine harpists working today that it's impossible to list them all here, but any survey of the field should certainly also include Derek Bell, Patrick Ball, Dominig Bouchaud, Robin Huw Bowen, C��cile Corbel, Paul Dooley, Loreena McKennitt, ��ine Minogue, Joanna Newsom, Maire Ni Chathsaigh, Nansi Richards, Kim Robertson, Sileas (Patsy Seddon & Mary Macmaster), Savourna Stevenson, and Robin Williamson. (Despite the proponderence of women harpists today, it should be noted that in the past women harpers were rare, often dismissed and slandered as "loose-living" women. In the Dark Ages it was strictly against the law for women to harp.)

"O wake once more," Sir Walter Scott once commanded the ancient harps of Scotland. "If one heart throb higher at its sway, the wizard note has not been touch'd in vain. Then silent be no more! Enchantress, wake again!"

More than two hundred years later, the harps are awake, and still making their magic.

Art credits can be found in the picture captions. (Run your cursor over the images to see them.)

Art credits can be found in the picture captions. (Run your cursor over the images to see them.)

Thomas the Rhymer...

I posted my article "The Enchanted Harp" today in honor of one of the finest of harp novels, Thomas the Rhymer by Ellen Kushner -- which has just been re-published in England as part of the prestigious Fantasy Masterworks series.

Based on a classic Scottish fairy ballad (Child Ballad 37), Thomas the Rhymer won The World Fantasy Award and the Mythopoeic Award when it was first published in 1990. It's one of my favourite books in the world, and I highly, highly recommend it.

See not ye that bonny road that winds about the fernie brae? That is the road to fair Elfland, where thou and I this night maun gae....

- from the ballad of Thomas the Rhymer

Go here to read Ellen's thoughts on using Celtic material in fantasy fiction, posted on this blog back in May.

The cover art above is for the Fantasy Masterworks edition (UK) and the most recent of the American editions (illustration by Kinuko Y. Craft).

The cover art above is for the Fantasy Masterworks edition (UK) and the most recent of the American editions (illustration by Kinuko Y. Craft).

July 14, 2015

Morning in the Studio (2015)

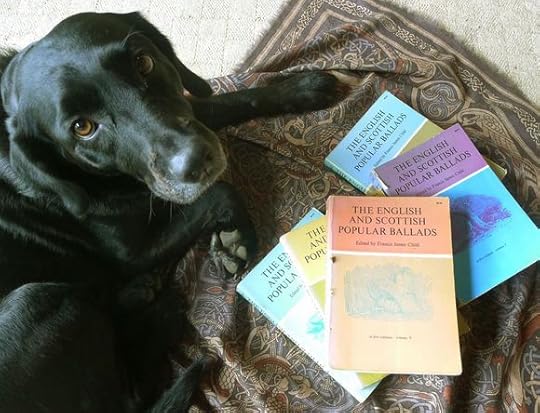

The Hound and I are in the studio again. Not for a full day, as I'm not up to that yet, but at least for a little while, during the quiet hours of a cool, grey Devon morning...which feels like a big step forward after weeks confined to bed.

Tilly has claimed her usual spot on the sofa, with a look that says: I'm not budging from here. She's been coming to work with me all her young life, and she finds it unsettling when the routine changes, as it has these last few weeks. As I write, she lies snuggled close  beside me, her furry black head heavy in my lap, listening to the familiar tapping of computer keys and sighing with contentment.

beside me, her furry black head heavy in my lap, listening to the familiar tapping of computer keys and sighing with contentment.

Today, after weeks of set-backs and disruptions, I find solace in re-visiting

this passage from May Sarton's Journal

of Solitude:

"I have said elsewhere that we have to make myths of our lives, the point being that if we do, then every grief or inexplicable seizure by weather, woe, or work can -- if we discipline ourselves and think hard enough -- be turned into account, be made to yield further insight into what it is to be alive, to be a human being, what the hazards are of a fairly usual, everyday kind. We go up to Heaven and down to Hell a dozen times a day -- at least I do. And the discipline of work provides an exercise bar, so that the wild, irrational motions of the soul become formal and creative."

That is the beauty of art, I think. Not only that the discipline and joy of creation can lift us during hard times, but also that those hard times, too, can feed the work...and spin straw into gold.

Illustration above: Rapunzel by Paul O. Zelinzky

Illustration above: Rapunzel by Paul O. Zelinzky

From the archives: Morning in the Studio (2013)

From "How I Get to Write" by Roxanna Robinson :

"In the morning, I don���t talk to anyone, nor do I think about certain things.

"I try to stay within certain confines. I imagine this as a narrow, shadowy corridor with dim bare walls. I���m moving down this corridor, getting to the place where I can write.

"I brush my teeth, get dressed, make the bed. I avoid conversation, as my husband knows. I am not yet in the world, and there is a certain risk involved in talking: the night spins a fine membrane, like the film inside an eggshell. It seals you off from the world, but it���s fragile, easily pierced.

"....The reason the morning is so important is that I���ve spent the night somewhere else. This is nowhere I can describe exactly, only that it���s mysterious and limitless, a place where the mind expands. Deep, slow currents, far below the surface, shift me in ways I needn���t understand. There is no sound, no scrutiny. Waking, I���m still close to that silent, preconscious, penumbral state, still focussed inward. I���m still in that deep, noiseless place, listening to its voices, very different from those of the outside world."

(The full article is here.)

I read Robinson's piece (on The New Yorker blog) thinking, "Oh my gracious yes, that's it exactly!" -- for I too like to be up and out to the studio before anyone else in the house is awake, climbing the hill from house to studio by the light of the stars. I don't want to speak or be spoken to; I don't want to be jogged from this liminal state; I want to rest on the delicate threshold between the Night World and the Day World just as long as I can.

At this moment as I write, the sky is still dark, the studio hushed with pre-dawn enchantment; the only sounds are the ticking of the clock, water rushing in the stream outside, and a single owl calling from the woods. I compose these morning posts as I drink my coffee, waking (as Agatha Christie's Poirot would say) the "little grey cells" up. But I musn't be too awake, not yet, in order to slide gently into the writing day before the "fragile membrane of the night" has been pierced.

Tilly snuggles up beside me, yawning, dozing, waiting for our morning walk out in the woods. The tap-tap-tap of the computer keys is a familiar, comforting sound to her. She is waiting for the sun, and the click of the laptop closing, and the words: Okay, girl, let's go.

���Outside, there was that predawn kind of clarity, where the momentum of living has not quite captured the day. The air was not filled with conversation or thought bubbles or laughter or sidelong glances. Everyone was sleeping, all of their ideas and hopes and hidden agendas entangled in the dream world, leaving this world clear and crisp and cold as a bottle of milk in the fridge. ���

- Reif Larsen (from The Selected Works of T.S. Spivet)

The paintings above are by Andrew Wyeth (1917-2009). The photograph at the top of the post is of the Kuerner Farmhouse in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, where he often painted. This post first appeared on Jan. 16, 2013.

July 12, 2015

Tunes for a Monday Morning

As those of you who've been reading this blog for a while know, I'm a great believer in art as a force for good, a tonic for the soul, and a potent medicine for healing and change on both the personal and global levels. A previous post, "Stories are Medicine," explored the mythic connection between stories and healing. Today's Monday Tunes all relate to the theme of healing, wholeness, and connection.

In "Manifesto," below, Nahko Bear and his band celebrate the power of music as medicine. Nahko is a singer/songwriter of Apache, Puerto Rican and Filipino heritage, and I'm deeply in love with his work. Raised in Oregon, he now lives in Hawaii. You'll find more of his music in this previous post.

Next: "Connected," from the great blues, soul, and gospel guitarist Eric Bibb. Raised in a musical family in New York City, Bibb now lives with his Finnish wife in Helsinki. You'll find more of his music in this previous post.

Below: "Braided Hair" by 1 Giant Leap -- the music/film/spoken-word project created by the UK musicians Jamie Catto (of Faithless) and Duncan Bridgeman. This intrepid pair traveled all around the world bringing musicians both famous and obscure into a pan-cultural musical collaboration, interspersed with the words of writers, philosphers, spiritual leaders and others. The results are gathered on two albums and DVDs: 1 Giant Leap and What About Me? The video above, featuring Speech, Neneh Cherry and other English, African, Indian, Asian, Australian, and Native American musicians, comes from their first DVD. I've played it here on Myth & Moor before, as it's one of my all-time favorites.

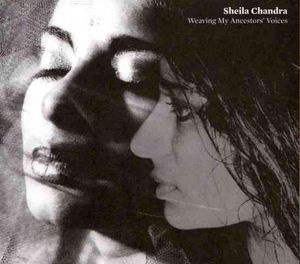

Below: "Ever So Lonely," performed by Sheila Chandra at the WOMAD festival. Chandra's influences range from the Indian and Anglo/Scots/Irish music of her ancestral background to other traditional musics from cultures around the world.

"I think this whole orchestral thing and this pop thing with chords and everything is just this maverick offshoot," she says in an interview with John Schaeffer that ranges from drones to mythic crones to celestial harmonics. "Its kind of an upstart movement, isn't it? That has nothing to do with what our biology dictates, because we drone. As long as we're alive we drone. We emit frequency, from the stapes bone in the middle ear, where apparently we emit the average of all the frequencies that we are, and also the blood rushing in our ears, and I think that stapes bone thing can be heard late at night when you can't sleep and there's this awful high pitched drone which seems really, really loud? I think that's the one it is. So, drones are present so long as we're present, so long as the listener is present. So, it's almost true to say that drones are at the essence of our aliveness."

"I think this whole orchestral thing and this pop thing with chords and everything is just this maverick offshoot," she says in an interview with John Schaeffer that ranges from drones to mythic crones to celestial harmonics. "Its kind of an upstart movement, isn't it? That has nothing to do with what our biology dictates, because we drone. As long as we're alive we drone. We emit frequency, from the stapes bone in the middle ear, where apparently we emit the average of all the frequencies that we are, and also the blood rushing in our ears, and I think that stapes bone thing can be heard late at night when you can't sleep and there's this awful high pitched drone which seems really, really loud? I think that's the one it is. So, drones are present so long as we're present, so long as the listener is present. So, it's almost true to say that drones are at the essence of our aliveness."

And one more:

"Prayers" by Ke Nova, a song inspired by the work of the Native American poet, novelist, and essayist Linda Hogan (whose books I highly recommend). Ke Nova (Kati Gleiser) is a Canadian singer/songwriter and concert pianist known for her creative and academic work at the cutting edge of music technology.

"Our songs travel the earth. We sing to one another. Not a single note is ever lost and no song is original. They all come from the same place and go back to a time when only the stones howled.''

- Louise Erdrich (The Master Butchers Singing Club)

July 8, 2015

Myth & Moor: An updated update

My apologies for the delay in getting back to Myth & Moor. I'm still dealing with health problems -- which are more complicated than I'd initially thought, but being competently dealt with, so please don't worry.

The Hound, at least, is happy that I'm still at home, even if no one else is. Bless her.

Edited on Friday, July 10, to add a further update:

My travel plans have, sadly, been cancelled due to medical restrictions. Han Nolan (National Book Award winner for Dancing on the Edge) has kindly stepped in to take my place as the Writer-in Residence for the Children's Book Writing & Illustration M.F.A. program at Hollins University in Virgina. I wish Han and all the writers, artists, academics, and students at Hollins a wonderful and productive summer session; I truly wish I could be there with you all.

Although I'm confined to home until my health situation improves, I'm planning to resume posting here on Myth & Moor this coming Monday (July 13), strength permitting, so please check back.

And thank you again, dear Readers, for your patience.

Courtyard statue, "The Lady of Bumblehill," by Wendy Froud

Courtyard statue, "The Lady of Bumblehill," by Wendy Froud

Myth & Moor: Update

My apologies for the delay in getting back to Myth & Moor. I'm still dealing with health problems -- which are more complicated than I'd initially thought, but being competently dealt with, so please don't worry. I'll be back just as soon as I can.

The Hound, at least, is happy that I'm still at home, even if no one else is. Bless her.

Courtyard statue, "The Lady of Bumblehill," by Wendy Froud

Courtyard statue, "The Lady of Bumblehill," by Wendy Froud

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers