Terri Windling's Blog, page 129

September 21, 2015

Myth & Moor update

I apologize, dear Readers, for taking so long to participate in the discussions in response to last week's posts. I'm still moving rather s-l-o-w-l-y through this period of physical recovery, and I'm having to strictly limit my online time in order to catch up on all the work that I've missed these last few months. I value the discussions  here a great deal (as well as the extraordinary poems), and I intend to go back and respond properly to it all just as soon as I can. I am reading the comments as they come in, and I'm grateful to all of you who've been keeping the discussion here going.

here a great deal (as well as the extraordinary poems), and I intend to go back and respond properly to it all just as soon as I can. I am reading the comments as they come in, and I'm grateful to all of you who've been keeping the discussion here going.

Tilly is still doing well in her own recovery, and has bounced joyfully back from her operation last month. Today, however, she's on medication for an unrelated infection, so she's moving a little s-l-o-w-l-y this morning too. But as you can see from this picture (taken by my husband), we're managing to get outdoors...and that's the best medicine of all.

Thank you for all your good wishes and prayers for us both.

Tunes for a Monday Morning

The beauty of folk music, for me, is that it has one foot in the past and one foot in the present, as each generation takes up its traditions and crafts something fresh, something old and new all at once. This week's tunes are all new releases from contemporary folk musicians here in the UK.

Above, the title track from Stone's Throw, a new album by Rachel Taylor-Beales (based in Cardiff, Wales) containing her deeply folkloric song-cycle, "Lament Of The Selkie."

"I���d been exploring the character and persona of Selkie," she says, "a shape-shifting seal-woman re-imagined from Orkney folklore, as she struggled to live her life on land away from her natural habitat of the ocean. More and more Selkie���s internal turbulence seemed to echo the real life struggles of people, both in the news headlines and that I met personally. These were the stories of refugees and displaced people, far from home with all the loneliness and chaos, grief and loss that comes with enforced migration. In the legends, in order to marry a Selkie woman her sealskin had to be captured while she was in human form, and kept hidden from her lest she find it and take the opportunity to return to her home in the sea. The woman of the legends, taken out of her natural environment, longing for home, misunderstood by those around her that did not understand her culture or her grief and who knew nothing of her life before she lived on land, became synonymous in my mind with these real time stories of refugees of the last few years. The video was filmed by my artist husband, Bill Taylor-Beales, and features Isla Horton, who achingly portrays a displaced mother separated from home and family."

"I���d been exploring the character and persona of Selkie," she says, "a shape-shifting seal-woman re-imagined from Orkney folklore, as she struggled to live her life on land away from her natural habitat of the ocean. More and more Selkie���s internal turbulence seemed to echo the real life struggles of people, both in the news headlines and that I met personally. These were the stories of refugees and displaced people, far from home with all the loneliness and chaos, grief and loss that comes with enforced migration. In the legends, in order to marry a Selkie woman her sealskin had to be captured while she was in human form, and kept hidden from her lest she find it and take the opportunity to return to her home in the sea. The woman of the legends, taken out of her natural environment, longing for home, misunderstood by those around her that did not understand her culture or her grief and who knew nothing of her life before she lived on land, became synonymous in my mind with these real time stories of refugees of the last few years. The video was filmed by my artist husband, Bill Taylor-Beales, and features Isla Horton, who achingly portrays a displaced mother separated from home and family."

Below, "Hasp" by Stick in the Wheel (based in London), whose new album, From Here, comes out later this month. ���We see [traditional] music as part of our culture," says lead singer Nicola Kearey; "we���re not pretending to be chimney sweeps or 17th century dandies. A lot of people are really disconnected from their past, and this is part of what we���re addressing -- getting people to reconnect with it, and realise there are parallels to be drawn from life 100 or 200 years ago. We make this music because we have to.���

Next:

"Mother You Will Rue Me" (audio only) by Ange Hardy. She wrote the song for Esteesee, an album based on the life and work of Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834), featuring Hardy and other folk musicians. On this track, she's joined by folk veteran Steve Knightley, from Show of Hands.

Hardy explained the genesis of the song in a guest post for Folk Radio UK: "When he was 8 years old Coleridge ran away from home following an argument with his older brother Frank in which Coleridge lunged at him with a knife. Having written a number of songs about my own childhood flight from home there was no way I could ignore this episode of Coleridge���s life.

Hardy explained the genesis of the song in a guest post for Folk Radio UK: "When he was 8 years old Coleridge ran away from home following an argument with his older brother Frank in which Coleridge lunged at him with a knife. Having written a number of songs about my own childhood flight from home there was no way I could ignore this episode of Coleridge���s life.

"After lunging at Frank with a knife, Coleridge���s Mother returned to the room, and fearing he���d be flogged Coleridge fled and hid at the bottom of a hill by the river Otter, reading prayers from a shilling book, hiding beneath a thorn bush and watching the calves in the field. The town crier was called in to rally the search party, and knowing full well the whole of the town was looking for him, Coleridge ended up sleeping in that field all night. In later years Coleridge confessed to thinking with 'inward and gloomy satisfaction' how miserable it must have made his Mother. That���s where the tone of the song came from.

"This song is Coleridge lamenting from beneath a thorn bush, in the cold and the damp. Coleridge wrote in one of his letters 'I felt the cold in my sleep, and dreamt that I was pulling the blanket over me, & actually pulled over me a dry thorn bush, which lay on the hill.' "

And last:

We return to the theme of refugees in a video released last week by folk singer and songwriter Martha Tilston (from Cornwall), whose fine albums I hope you all know. The song was inspired by the refugee crisis here in Europe, written to raise money for M��decins Sans Fronti��res.

Speaking of which, there are two book-related sites raising funds for refugees as well, one set up by the Carnegie Medal winning YA writer Patrick Ness, and one by writer & puppeteer Austin Hackney: Writers 4 Refugees. Please help if you can.

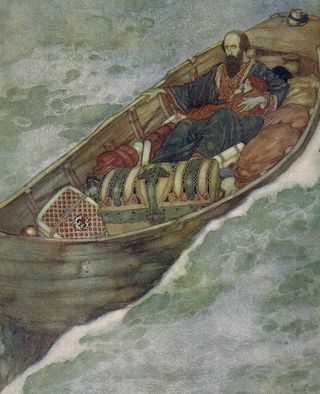

The fairy tale illustrations above are by Arthur Rackham.

September 17, 2015

On illness, 4: Emerging from the Forest

For the final post in this series on illness, I'd like to look at illness's aftermath: that tricky transition from the slow, deep work of recuperation back to the bustling workaday world, the final part of the fairy tale journey when we emerge from the forest at last. In mythic terms, the end of shamanic initiation is not the ascent from the Underworld, re-born and carrying new knowledge and skills from the spirit realm; it's the return to the tribe and the use of those skills in the service of community.

"Contact with the mythic realm, and the knowing that that imparts, changes the very being of the initiate," writes Kat Duff (in The Achemy of Illness); "he or she is never the same again. Perhaps that is why so many sick people come to divide their lives in two: before and after getting sick."

Duff continues: "The final phase of initation -- emergence from the underworld, return, and reintegration into the community -- is a very delicate one, for the incessant activity of the mundane world can be painful, even devastatig to the initiate so sensitized by contact with the mythic realm. Many do not make it. Since I have been getting better in recent months, I have dreamed more than once that I am a bear coming out of hibernation, all groggy and clumsy -- and blinded by the light of day; in the first two dreams I just crawled back into my hole.

"Newly 'hatched' initiates are often protected for a short while , sometimes rocked or suckled like newborns, to help orient them to their new lives. Similarly, people recovering from serious illnesses need a quiet place, a safe haven, where they can gradually recollect themselves and establish a new center of gravity."

"Newly 'hatched' initiates are often protected for a short while , sometimes rocked or suckled like newborns, to help orient them to their new lives. Similarly, people recovering from serious illnesses need a quiet place, a safe haven, where they can gradually recollect themselves and establish a new center of gravity."

I couldn't agree more, and yet our modern society -- obsessed with youth, speed, perfectionist ideals and relentless productivity -- rarely permits the time and practical support for our slow re-orientation to lives that have been profoundly changed by the enormity of what we've just been through.

"Unfortunately," Duff laments, "few of us get that support, as we are pushed by the demands of contemporary living back into the hustle and bustle as soon as we are able. There are debts to be paid, children to be attended to, and jobs that will not wait forever."

In initiatory rites around the world, the initiates return not only schooled in new spiritual knowledge but also carrying sacred gifts, like the tobacco seeds in Tuesday's story. Duff notes that in traditional society these gifts often took the form of new songs or dances. "I suspect," she says, "that these gifts actually ease and ensure a successful reentry by calling forth the body's memory, which is so much more detailed and accurate than words or ideas, of the mythic realities encountered during initiation. Of course, these gifts are also responsibilities; initiates are often required to perform their songs or dances at later dates, for the continued well-being of the community of life. We too need to carry something of what we've experienced back into the world of the living, to remember the dreams, follow the imperatives, or use the powers we have been given by our sojourns in the underworld. That takes courage, clarity of mind, and the willingness to follow one's truth even if others cannot affirm it, especially in our culture, which does not recognize the initiatory role of illness, in fact actively resists it by encouraging us to 'get back to normal.' "

"If we do not carry what we have learned back into the world," Duff continues, "we risk getting sick again, for the energies unused can revert into their destructive forms, in what I consider to be one of the hidden cruelties of illness. It has happened to many people -- including Black Elk. When Black Elk first received his great vision at the ripe age of nine, he knew it was meant to be shared, but he could not figure out how to do that, and so he did not; eight years later he got sick again and was tormented with fears until finally an old medicine man told him that he must do what his vision wanted him to do -- enact the horse dance for his people to see -- and helped him to do it.

"When initiations are successful, the survivors slowly return to their communities with new eyes to see, new ears to hear, and the courage to act upon those perceptions. [After recovering from a heart attack,] Carl Jung went on to do his most important work, explaining that 'the insight I had had, the vision of the end of all things, gave me the courage to undertake new formulations.' [In The Cancer Journals,] Audre Lord spoke of feeling 'another kind of power' growing within her, one that was 'tempered and enduring, grounded in the realities of what I am,' with the determination to 'save my life by using my life in the service of what must be done.' Just as girls are 'grown' into women through their puberty initiation rites, many people who have been seriously ill become what they must become, what they are meant to be, whether that occurs through death or recovery."

"When initiations are successful, the survivors slowly return to their communities with new eyes to see, new ears to hear, and the courage to act upon those perceptions. [After recovering from a heart attack,] Carl Jung went on to do his most important work, explaining that 'the insight I had had, the vision of the end of all things, gave me the courage to undertake new formulations.' [In The Cancer Journals,] Audre Lord spoke of feeling 'another kind of power' growing within her, one that was 'tempered and enduring, grounded in the realities of what I am,' with the determination to 'save my life by using my life in the service of what must be done.' Just as girls are 'grown' into women through their puberty initiation rites, many people who have been seriously ill become what they must become, what they are meant to be, whether that occurs through death or recovery."

"And so, through processes well described by alchemical formulas and initiation rites," Duff concludes, "we are both diminished and enlarged by the agency of our illnesses, and so opened to the possibility of new life. The losses are many and visible; the harvest grain is smaller than the standing stalks, but so much more useful. So Nietzsche observed: 'I doubt that such pain makes us "better"; but I know it makes us more profound...from such abysses, from such severe sickness, one returns newborn, having shed one's skin.' "

"Cancer changes people," writes Doris Brett (in Eating the Underworld). "It is one of those marker events that delineates a 'before' and 'after' in our lives. It forces us to define and redefine ourselves. And then, because the experience of cancer is an extended process and not a static event, it forces us to do it again and again.

"And it is right that we are changed. As with any descent into a feared and terrifying country -- whether it the country of illness or the country of a grieving heart -- we have entered the underworld. And we have eaten its fruit. I remember all the mythical stories of those frightening journeys, and with each one the rule is inviolate. Those who ingest the food of the underworld are bound to it in some way. It is not the binding of instruments of torture and the roastings of hell. Instead, it is the binding of that terrible, clear sight that can only be gained in the depths. The knowledge of ourselves, the knowledge of others. We cannot remain unchanged."

"The end point of the cancer survivor's narrative," writes Brett at the close of her luminous book, "is inevitably the 'what I learned from cancer' finale. We expect it in the way we expect swelling music as the movie ends. It is more than expectation, it is a need. And we need what is learned to be good: 'I learned how loved I am,' 'I learned I am a survivor.' It is a way of waving away the dark; a way of reassuring ourselves; a way of saying that even though it was hard and punishing, it was worth it. It meets our deep and often unspoken need to complete the story; the familiar bedtime story that tells us that everything will be alright in the end.

"When I began my dance with cancer," Brett admits, "I imagined that this is what I would emerge with. That when it was ended, what I would hold in my hand was the silver lining. I imagined that I would be changed, but that was the point at which my imagination failed. All I could imagine was a better, brighter me -- the steel that is finer for having been tempered in the fire.

"What I learned is very different from what I expected to learn. I have learned that I am loved. I learned it from old friends who stood by me, and new friends who helped in unexpected and touching ways....But I have also learned from others that where I thought I was loved, I was not. I have been attacked when I was most vulnerable. I was deserted by those I thought would gladly stay with me.

"I have learned that things turn out well. And that they don't. I have had moments when I thought I would die from the sheer physical beauty of the world. And moments when it merely seemed to mock what was happening to me. I have had wonderful things happen and terrifying things too.

"I have learned that things turn out well. And that they don't. I have had moments when I thought I would die from the sheer physical beauty of the world. And moments when it merely seemed to mock what was happening to me. I have had wonderful things happen and terrifying things too.

"My journey through cancer was supposed to be a simple one, along the lines of St. George fighting the dragon. Instead, it led me to revelations about the underside, the flawedness, of all things -- myself, my family, my friends, my world. Recognizing and accepting these has required far more courage than facing cancer. It is what I never expected; fought hardest to avoid -- and yet perhaps it has been the truest gift to come out of all of this.

"In many ways, it is hard to live in the real world with its lack of delineations, in inequities, its ambiguities. How do you keep going in the face of uncertainty? Not just the uncertainty of mortality, but the day-to-day slogging on your dreams, unsure they will ever come to fruition; the investment in relationships, unsure of what they will turn out to be; the tender nurturing of hopes, aware they may be shattered; the knowledge that nothing is purely one thing or another.

"But it is only by emerging from the shimmering world of make-believe that we have a chance at finding our true lives -- our strength, and with it, our authentic capacity to love. Because love must be about seeing the shadow as well as the light, otherwise it is merely the love of a fantasy, an image created to soothe the wounds in our soul. And strength must involve recognizing one's own fear and vulnerability, but standing up anyway."

Though we are talking here about the end of the journey, the "before" and "after" of a serious illness, for many of us there is no clear "after," but, rather, the ups and downs of a recurring condition, or the slow deterioration of a progressive one, or an illness marked "cured" in a medical file that nonetheless leaves one weakened and vulnerable to others, debilitating in their own right. Each flare up, each descent, is another mythic journey, and it rarely gets any easier with repetition or familiarity. But still we go on. We ascend from the depths. We emerge from the forest. We return to the world with tobacco seeds in our pockets, with new songs to sing and new stories to tell.

This one's mine. And Kat Duff's. And Doris Brett's.

It may be your story too. If so, I wish you well. Be safe. Be strong. Perhaps we'll meet somewhere in the dark woods, and we'll find the path out together.

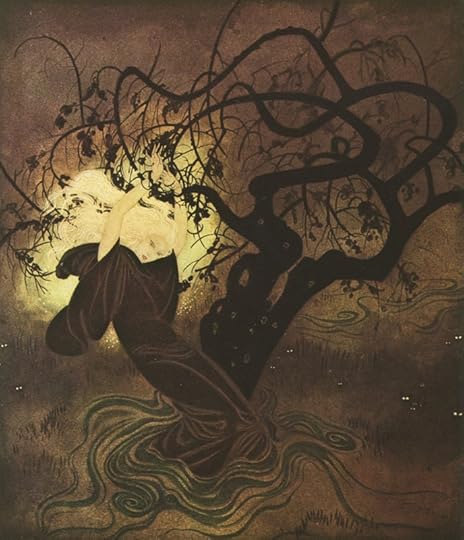

The heart-rendingly beautiful paintings above are by Jeanie Tomanek, based in Georgia. The titles of the paintings can be found in the picture captions. (Run your cursor over the images to see them.) Please visit Jeanie's website or Facebook page to see more of her work. You can also purchase her prints through these Etsy shops: Everywoman Art and Easy Beast Designs. You'll find a lovely interview with the artist here, and a video combining Jeanie's art with the sublime music of Arvo P��rt here.

The heart-rendingly beautiful paintings above are by Jeanie Tomanek, based in Georgia. The titles of the paintings can be found in the picture captions. (Run your cursor over the images to see them.) Please visit Jeanie's website or Facebook page to see more of her work. You can also purchase her prints through these Etsy shops: Everywoman Art and Easy Beast Designs. You'll find a lovely interview with the artist here, and a video combining Jeanie's art with the sublime music of Arvo P��rt here.

On illness, 3: Wild Snails, Shadows, and Grown-Upness 101

Serious illness, like all the important things in life, is rich in paradox, and one its paradoxes is this:

The journey of illness is a deeply personal and profoundly solitary: we are alone in the sickbed, alone in pain, alone in those terrifying moments of being wheeled into the operating room, and alone, ultimately, at the journey's end: whether we're the lucky ones, the survivors exhaustedly surveying the wreckage of our previous lives, or those at the very end of their stories, crossing the threshold from life into death. Yet it is equally true that illness unfolds in a space crowded with other people, stripping us of privacy and self-agency as we depend on doctors, nurses, receptionists, anonymous technicians in distant laboratories and, especially, our dear families and friends, whose own lives must change to make room for The Beast (the illness) now living so awkwardly, ferociously among us.

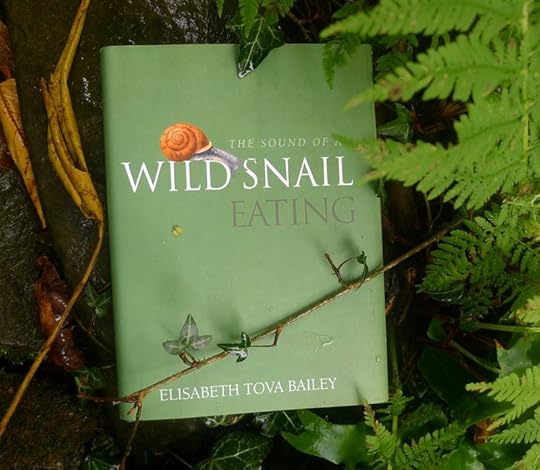

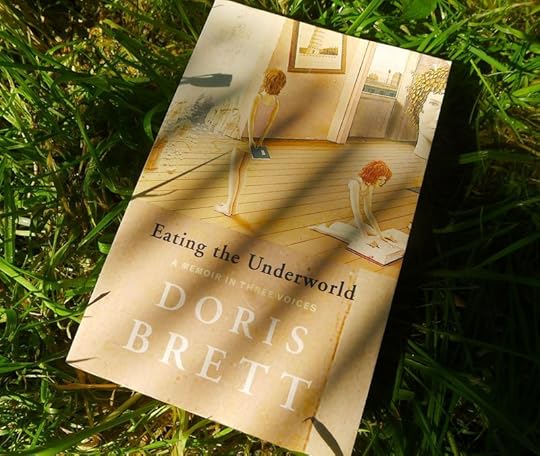

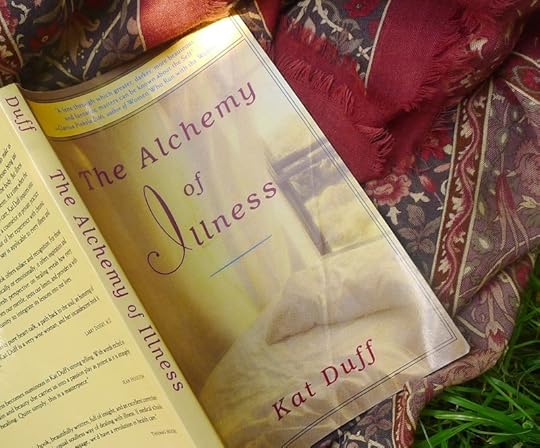

My last two posts have addressed the solitary nature of the descent into the Underworld of illness -- so today, let's look at the other side of the coin. These passages come from three of my favorite "illness memoirs": The Sound of a Wild Snail Eating by Elisabeth Tova Bailey, Eating the Underworld by Doris Brett, and, once again, The Alchemy of Illness by Kat Duff.

Bailey's The Sound of a Wild Snail Eating is an unusual and beautifully crafted book that is part memoir (an account of her life during years bedridden with a semi-paralysing auto-immune disease) and part nature writing (the close observation of the life of a woodland snail who lived in a pot of violets, and then a terrarium, in the confines of Bailey's sick room). She has this to say about her relationship to her friends during her illness -- relationships which, inevitably, changed as she drifted farther and farther from her former life:

"The mountain of things I felt I needed to do reached the moon, yet there was little I could do about anything and time continued to drag me along its path. We are all hostages of time. We each have the same number of minutes and hours to live within a day, yet to me it didn't feel equally doled out. My illness brought me such an abundance of time that time was nearly all I had. My friends had so little time that I often wished I could give them what I could not use. It was perplexing how in losing health I had gained something so coveted but to so little purpose.

"I eagerly awaited visitors, but the anticipation and extra energy of greeting caused a numbing exhaustion. As the first stories unfolded, my spirit held on to the conversation as best it could -- I so wanted these connections to the outside world -- but my body sank beneath waves of weakness. Still, my friends were golden threads randomly appearing in the monotonous fabric of my days. Each visit was a window that opened momentarily into the life I had once known, always falling shut before I could make my way back through. The visits were like dreams from which I awoke once more alone.

"As the snail's world grew more familiar," Bailey notes, "my own human world became less so; my species was so large, so rushed and so confusing. I found myself preoccupied with the energy level of my visitors, and I started to observe them in the same detail with which I observed the snail. The random way my friends moved around the room astonished me; it was as if they didn't know what to do with their energy. They were so careless with it. There were spontaneous gestures of their arms, the toss of a head, a sudden bend into a full-body stretch as if it were nothing at all; or they might comb their fingers unnecessarily through their hair.

"It took time for visitors to settle down. They sat and fidgeted for awhile, then slowly relaxed until a calmness finally spread through them. They began to talk about more interesting things. But halfway through a visit they would notice how little I moved, the stillness of my body, and an odd quietness would come over them. They would worry about wearing me out, but I could see also that I was a reminder of all they feared: chance, uncertainty, loss and the sharp edge of mortality. Those of us with illnesses are the holders of the silent fears of those with good health.

"Eventually, discomfort moved through my visitors, nudging a hand into motion, a foot into tapping. The more apparent my own lack of movement, the greater their need to move. Their energy would turn into restlessness, propelling their bodies into action with a flinging of arms or a walk around the room; a body is not meant to be still. Soon my visitors were off."

Bailey's relationship with her dog changed as well.

"Even at eight years of age," she writes, "her energy was extreme compared to my own. It was incredible that I, too, had once moved through life with such exuberance, with her at my side. From my bed I could give her scraps of my dinner and manage a few stokes of her soft ears. I loved her so, and her intense longing for more made me ache to leap up from my bed, fling open the door to the outside world and escape, the two of us heading, once again, deep into the woods."

Instead, Bailey was forced to lie still, to let time crawl past while her broken body healed. Looking at the door to her room, she wondered, "Was this truly a door I would someday open and walk through, as if walking out into the world were an ordinary thing to do? I would look at the door until it reminded me of all the places I could not go. Then, exhausted and empty from my audacious adventure, I'd make the slow roll back toward the kingdom of the terrarium and the tiny life it contained."

The wild snail, by contrast to her visitors, was slow but purposeful, alone but self-sufficient. "Its curiosity and grace pulled me further into its peaceful and solitary world. Watching it go about its life in the small ecosystem of the terrarium put me at ease."

Eating the Underwood by Australian poet and clinical psychologist Doris Brett is a mythopoetic memoir of her experience with ovarian cancer -- a book I relate to particularly deeply as this is one of the illnesses I've come through as well. Here, Brett writes of her feelings of betrayal when friends she's supported through various crises turn away from her during her own ordeal:

"The fear that cancer inspires cannot be underestimated. Many people cannot bear to think about it, let alone come into regular contact with it and the reminder of their own mortality. Other react in infantile ways, angry that you will no longer be able to be 'mummy' and support them in ways to which they have become accustomed. Others still are so overcome by the anticipated pain of losing you, that they can't bear to have contact with you. Still others don't know what to say to you and so they say nothing and keep away. None of this, of course, makes it any easier on you. It still feels like abandonment."

It was not until long after, Brett writes, that she was able "to think about the choices I made in ringing those particular friends. I have recognized by then that there are other friends whom I didn't ring, who would indeed have come over and given me the support I needed. The friends I turned to for help were the ones I had given the most help to in the past.

"It highlights the shadow of the younger self I thought I'd left behind me; the one who felt she had to be extra good, nurturing and responsible; the one who was there to take care of people, not ask to be taken care of. I recognized the amazed gratitude I still feel if someone, unasked, goes out of their way to do something for me. The astonishment, because I haven't 'earned' it. And I can see that in turning to those friends to whom I had given a great deal, rather than to those with whom I'd had a more equal relationship, I was again bowing to that inner fear."

Later in the book, after time has passed, and after the frightening ups and downs of treatment have led to comparatively safer ground, Brett re-visits the subject with wisdom and compassion:

"I have a renewed appreciation of the friends who have stuck by me. And I am enormously touched by the friends with whom I haven't had much contact previously, who made time to come and see me or phone me. With the ones I felt let down by, it has taken time. I don't think I'll ever be able to trust them in the old way, or be as giving as I used to be with them. I am more clear-eyed. The view is not the view I wanted to see, but it is there and I am finding I can live with it.

"I'm not angry at them anymore, the way I was months ago. I have to recognize the part I played as well, try to understand it. I feel as if I've just taken a compressed course of Grown-Upness 101. Part of me has the slightly dazed expression of the child who's just accommodating the fact that no, the Tooth Fairy doesn't really exist. I am more cynical, not a characteristic I particularly like, but perhaps a more successful one than being too naively idealistic. I am simply more ready, more able, to see things as they really are.

"Because it does feel now as if I am freer to simply take these friends for who they are. I don't want to idealize them but neither to I want to demonize them. It doesn't have to be an either/or situation. I know their flaws. And although I can't imagine that I will want our previous closeness, I can still enjoy a friendship. Not everyone has the capability, or the will, to be there through difficult times -- and perhaps not everyone has to."

In The Alchemy of Illness, Kat Duff -- who suffers from M.E./chronic fatigue -- looks at the subject from a wider culture perspective:

"I have come to realize that many people are deeply disturbed by the fact of my continuing illness," she writes; "they want to help but also need to reassure themselves that disasters like disease can be avoided and, if necessary, easily remedied. Treya Killam Wilber remembered devising theories to explain her mother's colon cancer, only to realize later, when she herself developed cancer, that 'it was really fear -- unacknowledged, hidden fear -- that motivated me to believe the universe made sense and that its forces were more or less within my control. In such a reasonable universe, staying healthy would be a simple matter of avoiding stress or changing my personality or becoming a vegetarian.' It's hard to swallow the fact that we have little or no say over the extent and timing of our illnesses.

"Before the advent of modern medicine, people gave thanks for good health, counting it as an unexpected blessing, as many traditional peoples still do today. (Remember when people simply wished for good health in the New Year?) Buddhist scriptures taught that the bodies we inhabit are fertile ground for all manner of misfortunes, and no sensible person would entertain expectations of well-being unless they were mad. Well, we must be mad, for now we've come to assume well-being, and regard illness as a temporary breakdown of normal 'perfect' health.

"Our concepts of physical and pyschological health have become one-sidedly identified with the heroic qualities most valued in our culture: youth, activity, productivity, independence, strength, confidence, and optimism. Advertisements reflect our picture of health as young, white, slim, athletic...and beaming with 'the cheerful effervescence of a Bernie Siegal or a Louise Hay,' as writer Daniel Harris observed wryly. Even sick people are encouraged to cheer up and be brave, and those who can joke in the midst of obvious agony are revered by all."

Sickness by this definition, Duff points out, "is not only a breakdown of normal health but a personal failure, which explains why many sick people feel so guilty and ashamed....In our infatuation with health and wholeness, illness is onesidedly identified with the culturally devalued qualities of quiet, introspection, weakness, withdrawal, vulnerability, dependence, self-doubt, and depression. If someone displays any of these qualities to a great extent, he or she is likely to be considered ill and encouraged to see a doctor or therapist. In a perversion of recent discoveries of body-mind unity, self-help books encourage sick people to cultivate positive attitudes -- faith, hope, laughter, self-love, and a fighting spirit -- to overcome their diseases. As a result, many sick people are shamed by friends, family, or even their healers into thinking they are sick because they lack these 'healthy' attitudes, even though illnesses often accompany critical turning points in our lives when it is necessary to withdraw, reflect, sorrow, and surrender, in order to make needed changes. Normal life passages , such as birth, adolescence, the crises of middle age, old age, and death, are now treated as illnesses in need of medical intervention, simply because they are often characterized by pain, withdrawal, introspection, and alienation.

" 'In heath,' wrote Virginia Woolf, 'the general pretense must be kept up and the effort renewed -- to communicate, to civilize, to share, the cultivate the desert, to work together by day, and by night to sport. In illness this make-believe ceases... We cease to be soldiers in the army of the upright; we become deserters. They march to battle; we float with the sticks on the stream, helter-skelter with the dead leaves on the lawn, irresponsible and disinterested and able, perhaps the first time in years, to look round, to look up -- to look, for example, at the sky.'

"As Woolf intimates, the withdrawal, inactivity, and alienation of illness threaten the social order, undermining the faith, optimism, attachments, and obligations that keep systems in power -- in the family, workplace, and society at large. In the quiet stillness of the sickbed, where we look up and around rather than straight ahead, another -- truly revolutionary -- perspective emerges."

"Even at my sickess," Duff notes astutely, "when I was spending the majority of daylight hours in bed aching, I knew my illness was showing me facets of truth that I had missed -- we all had missed, it seemed -- and desperately needed."

Like all rites-of-passage, illness and calamity have things to teach us, and stories to tell us. But first we must listen. Then, we must remember. And finally, we must pass them on.

The poem in the picture captions is from The Zen of La Llorona by Native American poet Deborah A. Miranda (Earthworks, 2005); all right reserved by the author. It's a powerful piece about grief inspired by the legend of La Llorona.

The poem in the picture captions is from The Zen of La Llorona by Native American poet Deborah A. Miranda (Earthworks, 2005); all right reserved by the author. It's a powerful piece about grief inspired by the legend of La Llorona.

September 16, 2015

On illness, 2: The Nights to our Days, the Roots to our Trees

I'm going to continue posting on the subject of illness this week, not only because it's been a personal preoccupation in the last few months, but also because this side of life, too, has its myths, its folklore, its cycles and seasons; and even the healthiest among us will come to know its terrain as the story of our lives unfolds. It's a subject, however, that I'm well  aware makes some people deeply uncomfortable, and if you're one of them and prefer to return to Myth & Moor next week, you have my blessing.

aware makes some people deeply uncomfortable, and if you're one of them and prefer to return to Myth & Moor next week, you have my blessing.

One of the most interesting books I've read on this subject (and I've read many) is The Alchemy of Illness by Kat Duff, who shares my own interest in the folkloric, philosophic, and cultural ideas that quietly inform our daily lives, whether we're consciously aware of them or not; and who also finds parallels between illness and tales of descent into the Underworld of myth.

"Illness," Duff writes, "is an upside-down world, a mirror image reversing the assumptions of our normal daily lives. I think of it as the underside of life itself, the night to our days, the roots to our trees. The first thing that happens when I get sick, even before physical symptoms appear, is that I lose my normal interests. A kind of existential ennui rises in my bones like floodwater, and nothing seems worth doing: making breakfast, getting to work on time, or making love. That is when I know I am succumbing to the influence of illness, whether it is a minor cold or a life-threatening case of dysentery. I slip, like fluid, through a porous membrane, into the nightshade of my solar self, where I am tired of my friends, I hate my work, the weather stinks, and I am a failure."

"Under the sway of illness, people, like food, lose their appeal. Simple tasks, such as getting dressed, making meals, or returning phone calls, become difficult, onerous duties we avoid whenever possible. Our tolerances shrink to a narrow span; the juice is too sweet, the refrigerator too loud, the sheets too cold. I used to enjoy listening to the radio while working at my desk, but once I got sick, I could not stand the noise; I felt crowded and exhausted by it. That is why sick people spin cocoons around themselves; I often imagine myself wrapped like a mummy in a thick, fluffy blanket that filters out the invasive noise and smells of daily life.

"We shut the door, pull the shades, and unplug the phone when illness strikes, slipping away from the outer world and its material seductions like a boat drifting out to sea. The detailed terrain of our usual lives fades into a thin line between the vast indifference of sea and sky in the underworld of illness. We have nothing to say or do and want only to be left alone."

"There is, perhaps rightly so, an invisible rope that separates the sick from the well, so that each is repelled by the other, like magnets reversed," Duff continues. "The well venture forth to accomplish great deeds in the world, while the sick turn back into themselves and commune with the dead; neither can face the other very comfortably, without intrusions of envy, resentment, fear, or horror. Frankly, from  the viewpoint of illness, healthy people seem ridiculous, even a touch dangerous, in their blinded busyness, marching like soldiers to the drumbeat of duty and desire.

the viewpoint of illness, healthy people seem ridiculous, even a touch dangerous, in their blinded busyness, marching like soldiers to the drumbeat of duty and desire.

"Their world, to which we once belonged and will again, seems unreal, like some great board game that could fold up at any minute. Carl Jung reported that when he was recovering from a heart attack, the view from his window seemed 'like a painted curtain with black holes in it, or a tattered sheet of newspaper full of photographs meaning nothing.' He despaired of getting well and having to 'convince myself all over again that this was important.' We drop out of the game when we get sick, leave the field, and desert the cause. I often feel like a ghost, the slight shade of a person, floating through the world, but not of it. The rules and parameters of my world are different altogether.

"Space and time lose their customary definitions and distinctions. We drift in a daze and wake with a start to wonder: Where am I? On a train to San Francisco or at Grandmother's house? Maybe both, for opposites coexist in the underworld of illness. We are hot and cold at once, unable to  decide whether to throw off the blankets or pile more on, while something tells us our lives are at stake. Sometimes I feel heavy as a sinking ship, and other times light as a spirit rising from the wreckage. Our worlds shrink down to the four walls of the sick room, then entire universes unfurl themselves in the dust.

decide whether to throw off the blankets or pile more on, while something tells us our lives are at stake. Sometimes I feel heavy as a sinking ship, and other times light as a spirit rising from the wreckage. Our worlds shrink down to the four walls of the sick room, then entire universes unfurl themselves in the dust.

"Time stretches and collapses, warping like a record left in the sun. After living with epilepsy for several years, Margiad Evans wrote, 'Time has come to mean nothing to me: in certain moods it seems I slip in and out of its meshes as a sardine through a herring net.' Ten seconds seems like an hour of torture in acute pain, while a whole lifetime can be squeezed into a few moments as we wake from sleep or fall in a faint. Past and future inhabit the present, like threads so tangled the ends cannot be found. There have been times, in that liminal realm between waking and sleeping, when my life appeared before me in the shifting patterns of a weaving pulled by the corners, or the flickering reflections in an oil slick. What has been and what could be stand side by side without distinction; strange things seem connected."

"Defying the rules of ordinary reality, illness shares in the hidden logic of dreams, fairy tales, and the spirit realms mystics and shamans describe. There is often the feeling of exile, wandering, searching, facing dangers, finding treasures. Familiar faces take on the appearance of archetypal allies and enemies, 'some putting on a strange beauty, others deformed into the squatness of toads,' as Virginia Woolf noted. Dreams assume a momentous authority, while small ordinary things, like aspirin, sunshine, or a glass of water, become charged with potency, the magical ability to cure or poison."

"The traditions of white Western civilization," Duff continues a little later in the book, "have taught us to ignore and deny the sensations, instincts, dreams, and revelations our bodies continually generate to maintain a life-sustaining equilibrium. Now that I am sick, I am appalled to think that I used to respond to tiredness by pushing through it like a bulldozer to get my work done, or swim the full mile no matter what. Our determined efforts to pursue abstract goals and ideals, be it success, enlightenment, social responsibility, or even health, lead us dangerously astray, producing an intoxicating high and false pride that immediately collapse under the onslaught of illness. 'Insidious thing, pride,' wrote Laura Chester during the throws of lupus, to assume you are better, better, better...putting down others in order to feel secure, better than, more righteous, but what a fragile security we build for ourselves, out of sticks and straw, for the first and second little pigs.'

"There is nothing like a serious illness to blow down our fragile houses of sticks and straws. Standing amid the rubble of their lives and thoughts, people with serious illnesses undertake the task of building a new house, a new way of living, one that holds closer to the ground of being, the feedback and teachings of their bodies and souls."

"Illness is the shadow of Western civilization, the antithesis of the rampant extraversion and productivity it so values. As we attempt to exile disease from our world, it persists to haunt us with an ever-menacing guise, and we need it all the more to be whole, to save us from the curse of perfectionism.

"So certain realities remain to plague us. The best of people get sick, and many of those who do all the 'right' things stay sick or die, while others recover for no apparent reason. Epidemics come and go. As soon as we find the cure for one, another arises. We would like to think we can banish disease with rest, exercise, diet, medicine, prayer, or positive attitudes, but few so-called cures are reliable enough to trust, as anyone who has been sick a while can tell you. They're good ways to live, in sickness or health."

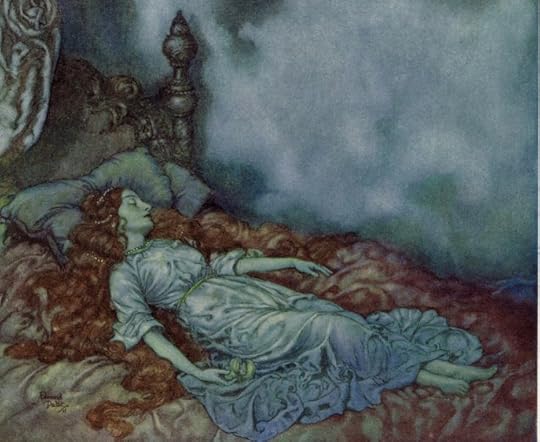

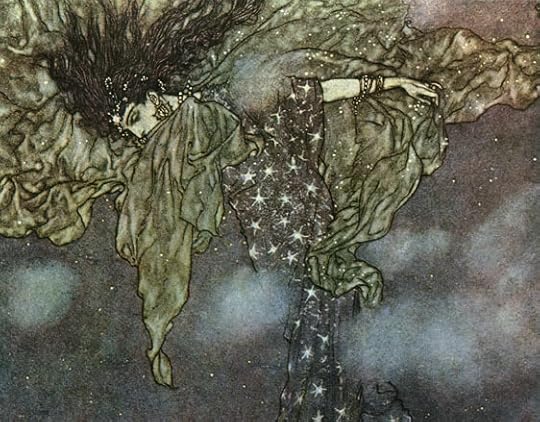

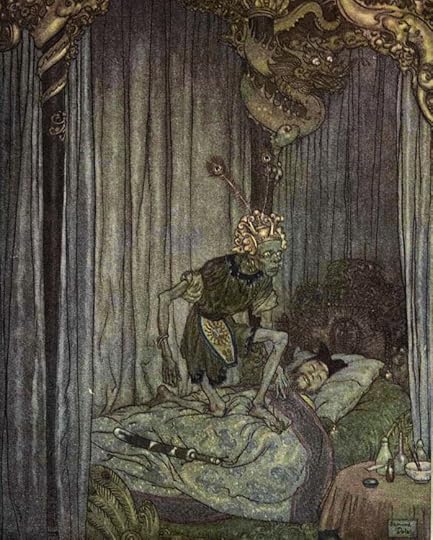

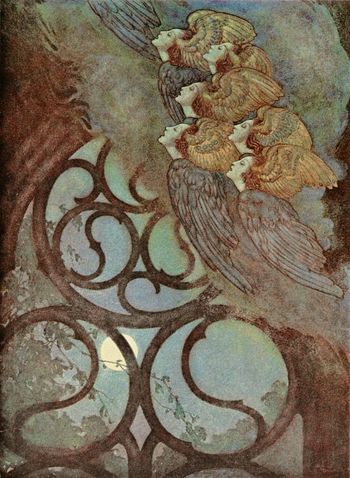

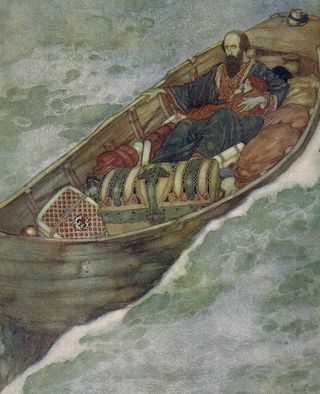

The paintings above are by the great Golden Age illustrator Edmund Dulac (1882 - 1953).

The paintings above are by the great Golden Age illustrator Edmund Dulac (1882 - 1953).

The nights to our days, the roots to our trees

I'm going to continue posting on the subject of illness this week, not only because it's been a personal preoccupation in the last few months, but also because this side of life, too, has its myths, its folklore, its cycles and seasons; and even the healthiest among us will come to know its terrain as the story of our lives unfolds. It's a subject, however, that I'm well  aware makes some people deeply uncomfortable, and if you're one of them and prefer to return to Myth & Moor next week, you have my blessing.

aware makes some people deeply uncomfortable, and if you're one of them and prefer to return to Myth & Moor next week, you have my blessing.

One of the most interesting books I've read on this subject (and I've read many) is The Alchemy of Illness by Kat Duff, who shares my own interest in the folkloric, philosophic, and cultural ideas that quietly inform our daily lives, whether we're consciously aware of them or not; and who also finds parallels between illness and tales of descent into the Underworld of myth.

"Illness," Duff writes, "is an upside-down world, a mirror image reversing the assumptions of our normal daily lives. I think of it as the underside of life itself, the night to our days, the roots to our trees. The first thing that happens when I get sick, even before physical symptoms appear, is that I lose my normal interests. A kind of existential ennui rises in my bones like floodwater, and nothing seems worth doing: making breakfast, getting to work on time, or making love. That is when I know I am succumbing to the influence of illness, whether it is a minor cold or a life-threatening case of dysentery. I slip, like fluid, through a porous membrane, into the nightshade of my solar self, where I am tired of my friends, I hate my work, the weather stinks, and I am a failure."

"Under the sway of illness, people, like food, lose their appeal. Simple tasks, such as getting dressed, making meals, or returning phone calls, become difficult, onerous duties we avoid whenever possible. Our tolerances shrink to a narrow span; the juice is too sweet, the refrigerator too loud, the sheets too cold. I used to enjoy listening to the radio while working at my desk, but once I got sick, I could not stand the noise; I felt crowded and exhausted by it. That is why sick people spin cocoons around themselves; I often imagine myself wrapped like a mummy in a thick, fluffy blanket that filters out the invasive noise and smells of daily life.

"We shut the door, pull the shades, and unplug the phone when illness strikes, slipping away from the outer world and its material seductions like a boat drifting out to sea. The detailed terrain of our usual lives fades into a thin line between the vast indifference of sea and sky in the underworld of illness. We have nothing to say or do and want only to be left alone."

"There is, perhaps rightly so, an invisible rope that separates the sick from the well, so that each is repelled by the other, like magnets reversed," Duff continues. "The well venture forth to accomplish great deeds in the world, while the sick turn back into themselves and commune with the dead; neither can face the other very comfortably, without intrusions of envy, resentment, fear, or horror. Frankly, from  the viewpoint of illness, healthy people seem ridiculous, even a touch dangerous, in their blinded busyness, marching like soldiers to the drumbeat of duty and desire.

the viewpoint of illness, healthy people seem ridiculous, even a touch dangerous, in their blinded busyness, marching like soldiers to the drumbeat of duty and desire.

"Their world, to which we once belonged and will again, seems unreal, like some great board game that could fold up at any minute. Carl Jung reported that when he was recovering from a heart attack, the view from his window seemed 'like a painted curtain with black holes in it, or a tattered sheet of newspaper full of photographs meaning nothing.' He despaired of getting well and having to 'convince myself all over again that this was important.' We drop out of the game when we get sick, leave the field, and desert the cause. I often feel like a ghost, the slight shade of a person, floating through the world, but not of it. The rules and parameters of my world are different altogether.

"Space and time lose their customary definitions and distinctions. We drift in a daze and wake with a start to wonder: Where am I? On a train to San Francisco or at Grandmother's house? Maybe both, for opposites coexist in the underworld of illness. We are hot and cold at once, unable to  decide whether to throw off the blankets or pile more on, while something tells us our lives are at stake. Sometimes I feel heavy as a sinking ship, and other times light as a spirit rising from the wreckage. Our worlds shrink down to the four walls of the sick room, then entire universes unfurl themselves in the dust.

decide whether to throw off the blankets or pile more on, while something tells us our lives are at stake. Sometimes I feel heavy as a sinking ship, and other times light as a spirit rising from the wreckage. Our worlds shrink down to the four walls of the sick room, then entire universes unfurl themselves in the dust.

"Time stretches and collapses, warping like a record left in the sun. After living with epilepsy for several years, Margiad Evans wrote, 'Time has come to mean nothing to me: in certain moods it seems I slip in and out of its meshes as a sardine through a herring net.' Ten seconds seems like an hour of torture in acute pain, while a whole lifetime can be squeezed into a few moments as we wake from sleep or fall in a faint. Past and future inhabit the present, like threads so tangled the ends cannot be found. There have been times, in that liminal realm between waking and sleeping, when my life appeared before me in the shifting patterns of a weaving pulled by the corners, or the flickering reflections in an oil slick. What has been and what could be stand side by side without distinction; strange things seem connected."

"Defying the rules of ordinary reality, illness shares in the hidden logic of dreams, fairy tales, and the spirit realms mystics and shamans describe. There is often the feeling of exile, wandering, searching, facing dangers, finding treasures. Familiar faces take on the appearance of archetypal allies and enemies, 'some putting on a strange beauty, others deformed into the squatness of toads,' as Virginia Woolf noted. Dreams assume a momentous authority, while small ordinary things, like aspirin, sunshine, or a glass of water, become charged with potency, the magical ability to cure or poison."

"The traditions of white Western civilization," Duff continues a little later in the book, "have taught us to ignore and deny the sensations, instincts, dreams, and revelations our bodies continually generate to maintain a life-sustaining equilibrium. Now that I am sick, I am appalled to think that I used to respond to tiredness by pushing through it like a bulldozer to get my work done, or swim the full mile no matter what. Our determined efforts to pursue abstract goals and ideals, be it success, enlightenment, social responsibility, or even health, lead us dangerously astray, producing an intoxicating high and false pride that immediately collapse under the onslaught of illness. 'Insidious thing, pride,' wrote Laura Chester during the throws of lupus, to assume you are better, better, better...putting down others in order to feel secure, better than, more righteous, but what a fragile security we build for ourselves, out of sticks and straw, for the first and second little pigs.'

"There is nothing like a serious illness to blow down our fragile houses of sticks and straws. Standing amid the rubble of their lives and thoughts, people with serious illnesses undertake the task of building a new house, a new way of living, one that holds closer to the ground of being, the feedback and teachings of their bodies and souls."

"Illness is the shadow of Western civilization, the antithesis of the rampant extraversion and productivity it so values. As we attempt to exile disease from our world, it persists to haunt us with an ever-menacing guise, and we need it all the more to be whole, to save us from the curse of perfectionism.

"So certain realities remain to plague us. The best of people get sick, and many of those who do all the 'right' things stay sick or die, while others recover for no apparent reason. Epidemics come and go. As soon as we find the cure for one, another arises. We would like to think we can banish disease with rest, exercise, diet, medicine, prayer, or positive attitudes, but few so-called cures are reliable enough to trust, as anyone who has been sick a while can tell you. They're good ways to live, in sickness or health."

The paintings above are by the great Golden Age illustrator Edmund Dulac (1882 - 1953).

The paintings above are by the great Golden Age illustrator Edmund Dulac (1882 - 1953).

September 15, 2015

On illness, 1: In a Dark Wood

"In the mid-path of my life, I woke to find myself in a dark wood," wrote Dante in The Divine Comedy, marking the start of a quest that will lead to transformation and redemption. Likewise, a journey through the dark of the woods is a common motif in fairy tales: young heroes set off through the perilous forest in order to reach their destiny; or they find themselves abandoned there, cast off and left for dead. The road is long and treacherous, prowled by ghosts, ghouls, wicked witches, wolves, and the more malign sorts of faeries....but helpers also appear on the path: wise crones, good faeries, and animal guides, often cloaked in unlikely disguise. The hero's task is to tell friend from foe, and to keep walking steadily onward.

In older myths, the dark road leads downward into the Underworld, where Persephone is carried off by Hades, much against her will, and Ishtar descends of her own accord to beat at the gates of Hell. This road of darkness lies to the West, according to Native American myth, and each of us must travel it at some point in our lives. The western road is one of trials, ordeals, disasters and abrupt life changes -- yet a road to be honored, nevertheless, as the road on which wisdom is gained. James Hillman, whose theory of "archetypal psychology" drew extensively on Greco-Roman myth, echoed this belief when he argued that darkness is vital at certain periods of life, questioning our modern tendency to equate mental health with happiness. It is in the Underworld, he reminds us, that seeds germinate and prepare for spring. Myths of descent and rebirth connect the soul's cycles to those of nature.

Having spent significant periods of my life in the muffled Underworld of physical disability, tales of the dark wood and myths of descent have a particular resonance for me, of course; but all of us enter the deep dark forest at some point in life or another, and such stories have much to tell us of how to find our way through; not unscathed, but transformed.

In an earlier age, a medicine man, shaman, or herb-wife consulted when my health problems first resurfaced this summer might have told me a story like this one, from the northern mountains of Mexico:

There was a young girl who married an old, old man, who used her ill. He worked her hard, beat her, starved her, and cast her off when she gave him no children, leaving her in the desert with no food, or water, or shelter. The young wife hid in the meager shade of rocks by day when the sun was fierce. By night she walked, crying, for she could not find her way home. The nights were cold. Wolves prowled the hills and carrion birds followed after her. She was hungry, thirsty, weary, and she walked till she could go no further. Lying down by a wide, dry wash, she wrapped herself in her long white skirt. She said, "Let La Huesera (the Bone Woman) take me, for I am spent." She died. Wild animals ate her flesh. Her spirit watched over the white, white bones and knew neither sorrow nor fear.

The bones lay in that secret place until the moon was full once more. And then La Huesera came and put them all in her woven sack. The old woman took the bones up to her cave high in the mountaintops, then laid them out beside her fire. She sat and smoked. She smoked and thought. She smoked and she thought for a long, long time, and then she began to sing.

"Flesh to bone! Flesh to bone! Flesh  to bone!" the Bone Woman sang, and before too long the bones knit back together, covered in flesh. Where the girl had once been red and rough, now she was soft and smooth and plump. Her skin was as gold as daylight and her hair as black as night. La Huesera sang and sang. She blew a puff of tobacco smoke. The young woman's eyes flew opened and she sat up and looked around her.

to bone!" the Bone Woman sang, and before too long the bones knit back together, covered in flesh. Where the girl had once been red and rough, now she was soft and smooth and plump. Her skin was as gold as daylight and her hair as black as night. La Huesera sang and sang. She blew a puff of tobacco smoke. The young woman's eyes flew opened and she sat up and looked around her.

The cave was empty. The ashes were cold. The old Bone Woman had disappeared. All that was left were tobacco seeds and she put them in her pocket.

She left the cave and started for home, following the rising sun. She knew she'd find her village walking this way, and so she did. She came upon her dwelling at last. The place was dark, deserted now. "That old man has died, that poor wife has died, come away from that place," the people said, for they did not recognize the lovely young woman who came to them out of the west. They gave her a name, a fine set of clothes, a new dwelling place, a goat, and a hen. They taught her human speech, for she had forgotten all that she knew. She planted La Huesera's seeds and tended the new plants carefully. In time, she married, and gave her young husband many gold���skinned daughters and black���haired sons, and her children's children's children still grow tobacco in that village today.

There are different versions of this basic story found in cultures the world over, particularly among the oral tales associated with healing rites. In the literal way we approach old folk and fairy tales in our modern world, it might seem just a simple "where tobacco comes from" story, or even a Cinderella variant: a mistreated girl is made beautiful, marries, and lives happily ever after. (I can picture the Disney version, complete with a singing-and-dancing La Huesera.) My gentle husband is not an abusive one, and I certainly didn't come through a summer of illness with sudden supernatural beauty. So why would this tale apply to my recent journey through the dark woods of illness?

Let's look at the tale again, as an ancient curandera (healer) might look.

It doesn't really matter how the girl came to find herself in the desert -- the Mexican equivalent of the mythic greenwood -- for any life change or calamity can trigger events that lead into the dark: Hansel & Gretel's parents abandon them there, Beauty takes her father's place in it, Donkeyskin chooses the dark unknown to  escape a more dreadful fate. The point is that our hero is there, alone, walking by night, miserable, in extremis, removed from the normal rhythms of life...and thus ripe for transformation. It is in the darkest hour of need that the guardian figures in folk tales appear, waiting by the side of the road as the hero stumbles by. In this case, our guide waits long indeed -- she waits until the hero is dead. (It is notable that as the young woman surrenders to her fate, all fear and sorrow leave her.) Like the hideous crones who are faery godmothers in disguise, La Huesera, scavenger of bones, is salvation cloaked in an unlikely form. The old woman carries the bones to a cave in the west, the place of the dead. Dead to her old life, if not to the world, the girl's spirit lingers, watches, and waits. Her patience is rewarded as her broken body is fashioned anew.

escape a more dreadful fate. The point is that our hero is there, alone, walking by night, miserable, in extremis, removed from the normal rhythms of life...and thus ripe for transformation. It is in the darkest hour of need that the guardian figures in folk tales appear, waiting by the side of the road as the hero stumbles by. In this case, our guide waits long indeed -- she waits until the hero is dead. (It is notable that as the young woman surrenders to her fate, all fear and sorrow leave her.) Like the hideous crones who are faery godmothers in disguise, La Huesera, scavenger of bones, is salvation cloaked in an unlikely form. The old woman carries the bones to a cave in the west, the place of the dead. Dead to her old life, if not to the world, the girl's spirit lingers, watches, and waits. Her patience is rewarded as her broken body is fashioned anew.

This "ritual death" is similar to shamanic initiation rites found in tribal cultures around the world. The initiates, in a state of trance, journey into the spirit world -- where their bodies die and are shorn of flesh, the bones picked over by spirits who are then persuaded, if all goes well, to sew them back together, better than new. (If the ceremonial procedure fails, however, an initiate can die in the trance state.) In this story, the young woman can be seen in the role of shamanic initiate. She lies down wrapped in long white cloth, the color of initiation. She leaves her body, returns to it, and finally becomes "twice-born," emerging from the cave (the womb of the Mother Earth) with a sacred gift for her people.

When she returns to her village, she is literally a new woman. She is given a new name, a new dwelling, and must learn to speak all over again. This, too, is common in initiation ceremonies found the world over. In one West African tribe, for instance, young male initiates drink a sacred brew which cause them to lose consciousness, whereupon they are taken into a special place deep in the jungle. When they wakes, they have forgotten their past and must be taught to speak, walk, and feed themselves. They return to the tribe with new names and new roles, transformed from boys into men.

The safe return from the jungle, the forest, the spirit world, or the land of death often marks, in traditional tales, a time of new beginnings -- new marriage, new life, and a new season of plenty and prosperity enriched not only by earthly treasures but those carried back from the Netherworld. Thomas the Rhymer, in the old Scottish ballad, returns to the human world after seven years in the woodlands of Faerie bearing the gift of prophesy, the "tongue that will not lie." Merlin returns from his time of exile and madness in the forests of Wales with magical knowledge and the ability to speak with the animals. Odin hangs in a death-like trance for ten days from the world-tree Yggdrasil, and comes back with the secret of runes from the dark land of Niflheim.

The hero of our story has also survived a great ordeal, a rite-of-passage from a barren life into one of great fecundity -- symbolized not only by marriage and children, but also by the precious tobacco seeds she brings for her people. To a modern audience, tobacco might seem a strange gift to appear in a healing tale since we now associate the plant with addiction, cancer, and death. Yet tobacco was once a sacred plant used only for ritual purpose and prayer -- particularly as old, ceremonial strains had hallucinogenic properties. (Some tribal elders say that it's casual use for non-religious purposes is what makes it so harmful today.)

Rites-of-passage stories like the one above were cherished in pre-literate societies not only for their entertainment value, but also as mythic tools to prepare young men and women for life's ordeals. A wealth of such stories can be found marking each major transition in the human life cycle: puberty, marriage, childbirth, menopause, death. Other rites-of-passage, less predictable but equally transformative, include times of sudden change and calamity such as illness and injury, the loss of one's home, the death of a loved one, etc. These are the times when we wake, like Dante, to find ourselves in a deep, dark wood -- an image that in Jungian psychology represents an inward journey. Rites-of���passage tales point to the hidden roads that lead out of the dark again -- and remind us that at the end of the journey we're not the same person as when we started. Ascending from the Netherworld (that grey landscape of illness, grief, depression, or despair), we are "twice-born" in our return to life, carrying seeds: new wisdom, ideas, creativity and fecundity of spirit.

The poem in the picture captions is "Otherwise" by Jane Kenyon, who was born in Michigan in 1947 and died of leukemia at the age of 48. The poem comes from her collection of the same title (Grey Wolf Press, 1996); all rights reserved by the author's estate. The drawings above are by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939) and Helen Stratton (1867-1961). A closely related post: "Stories are medicine."

The poem in the picture captions is "Otherwise" by Jane Kenyon, who was born in Michigan in 1947 and died of leukemia at the age of 48. The poem comes from her collection of the same title (Grey Wolf Press, 1996); all rights reserved by the author's estate. The drawings above are by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939) and Helen Stratton (1867-1961). A closely related post: "Stories are medicine."

In a dark wood

"In the mid-path of my life, I woke to find myself in a dark wood," wrote Dante in The Divine Comedy, marking the start of a quest that will lead to transformation and redemption. Likewise, a journey through the dark of the woods is a common motif in fairy tales: young heroes set off through the perilous forest in order to reach their destiny; or they find themselves abandoned there, cast off and left for dead. The road is long and treacherous, prowled by ghosts, ghouls, wicked witches, wolves, and the more malign sorts of faeries....but helpers also appear on the path: wise crones, good faeries, and animal guides, often cloaked in unlikely disguise. The hero's task is to tell friend from foe, and to keep walking steadily onward.

In older myths, the dark road leads downward into the Underworld, where Persephone is carried off by Hades, much against her will, and Ishtar descends of her own accord to beat at the gates of Hell. This road of darkness lies to the West, according to Native American myth, and each of us must travel it at some point in our lives. The western road is one of trials, ordeals, disasters and abrupt life changes -- yet a road to be honored, nevertheless, as the road on which wisdom is gained. James Hillman, whose theory of "archetypal psychology" drew extensively on Greco-Roman myth, echoed this belief when he argued that darkness is vital at certain periods of life, questioning our modern tendency to equate mental health with happiness. It is in the Underworld, he reminds us, that seeds germinate and prepare for spring. Myths of descent and rebirth connect the soul's cycles to those of nature.

Having spent significant periods of my life in the muffled Underworld of physical disability, tales of the dark wood and myths of descent have a particular resonance for me, of course; but all of us enter the deep dark forest at some point in life or another, and such stories have much to tell us of how to find our way through; not unscathed, but transformed.

In an earlier age, a medicine man, shaman, or herb-wife consulted when my health problems first resurfaced this summer might have told me a story like this one, from the northern mountains of Mexico:

There was a young girl who married an old, old man, who used her ill. He worked her hard, beat her, starved her, and cast her off when she gave him no children, leaving her in the desert with no food, or water, or shelter. The young wife hid in the meager shade of rocks by day when the sun was fierce. By night she walked, crying, for she could not find her way home. The nights were cold. Wolves prowled the hills and carrion birds followed after her. She was hungry, thirsty, weary, and she walked till she could go no further. Lying down by a wide, dry wash, she wrapped herself in her long white skirt. She said, "Let La Huesera (the Bone Woman) take me, for I am spent." She died. Wild animals ate her flesh. Her spirit watched over the white, white bones and knew neither sorrow nor fear.

The bones lay in that secret place until the moon was full once more. And then La Huesera came and put them all in her woven sack. The old woman took the bones up to her cave high in the mountaintops, then laid them out beside her fire. She sat and smoked. She smoked and thought. She smoked and she thought for a long, long time, and then she began to sing.

"Flesh to bone! Flesh to bone! Flesh  to bone!" the Bone Woman sang, and before too long the bones knit back together, covered in flesh. Where the girl had once been red and rough, now she was soft and smooth and plump. Her skin was as gold as daylight and her hair as black as night. La Huesera sang and sang. She blew a puff of tobacco smoke. The young woman's eyes flew opened and she sat up and looked around her.

to bone!" the Bone Woman sang, and before too long the bones knit back together, covered in flesh. Where the girl had once been red and rough, now she was soft and smooth and plump. Her skin was as gold as daylight and her hair as black as night. La Huesera sang and sang. She blew a puff of tobacco smoke. The young woman's eyes flew opened and she sat up and looked around her.

The cave was empty. The ashes were cold. The old Bone Woman had disappeared. All that was left were tobacco seeds and she put them in her pocket.

She left the cave and started for home, following the rising sun. She knew she'd find her village walking this way, and so she did. She came upon her dwelling at last. The place was dark, deserted now. "That old man has died, that poor wife has died, come away from that place," the people said, for they did not recognize the lovely young woman who came to them out of the west. They gave her a name, a fine set of clothes, a new dwelling place, a goat, and a hen. They taught her human speech, for she had forgotten all that she knew. She planted La Huesera's seeds and tended the new plants carefully. In time, she married, and gave her young husband many gold���skinned daughters and black���haired sons, and her children's children's children still grow tobacco in that village today.

There are different versions of this basic story found in cultures the world over, particularly among the oral tales associated with healing rites. In the literal way we approach old folk and fairy tales in our modern world, it might seem just a simple "where tobacco comes from" story, or even a Cinderella variant: a mistreated girl is made beautiful, marries, and lives happily ever after. (I can picture the Disney version, complete with a singing-and-dancing La Huesera.) My gentle husband is not an abusive one, and I certainly didn't come through a summer of illness with sudden supernatural beauty. So why would this tale apply to my recent journey through the dark woods of illness?

Let's look at the tale again, as an ancient curandera (healer) might look.

It doesn't really matter how the girl came to find herself in the desert -- the Mexican equivalent of the mythic greenwood -- for any life change or calamity can trigger events that lead into the dark: Hansel & Gretel's parents abandon them there, Beauty takes her father's place in it, Donkeyskin chooses the dark unknown to  escape a more dreadful fate. The point is that our hero is there, alone, walking by night, miserable, in extremis, removed from the normal rhythms of life...and thus ripe for transformation. It is in the darkest hour of need that the guardian figures in folk tales appear, waiting by the side of the road as the hero stumbles by. In this case, our guide waits long indeed -- she waits until the hero is dead. (It is notable that as the young woman surrenders to her fate, all fear and sorrow leave her.) Like the hideous crones who are faery godmothers in disguise, La Huesera, scavenger of bones, is salvation cloaked in an unlikely form. The old woman carries the bones to a cave in the west, the place of the dead. Dead to her old life, if not to the world, the girl's spirit lingers, watches, and waits. Her patience is rewarded as her broken body is fashioned anew.

escape a more dreadful fate. The point is that our hero is there, alone, walking by night, miserable, in extremis, removed from the normal rhythms of life...and thus ripe for transformation. It is in the darkest hour of need that the guardian figures in folk tales appear, waiting by the side of the road as the hero stumbles by. In this case, our guide waits long indeed -- she waits until the hero is dead. (It is notable that as the young woman surrenders to her fate, all fear and sorrow leave her.) Like the hideous crones who are faery godmothers in disguise, La Huesera, scavenger of bones, is salvation cloaked in an unlikely form. The old woman carries the bones to a cave in the west, the place of the dead. Dead to her old life, if not to the world, the girl's spirit lingers, watches, and waits. Her patience is rewarded as her broken body is fashioned anew.

This "ritual death" is similar to shamanic initiation rites found in tribal cultures around the world. The initiates, in a state of trance, journey into the spirit world -- where their bodies die and are shorn of flesh, the bones picked over by spirits who are then persuaded, if all goes well, to sew them back together, better than new. (If the ceremonial procedure fails, however, an initiate can die in the trance state.) In this story, the young woman can be seen in the role of shamanic initiate. She lies down wrapped in long white cloth, the color of initiation. She leaves her body, returns to it, and finally becomes "twice-born," emerging from the cave (the womb of the Mother Earth) with a sacred gift for her people.

When she returns to her village, she is literally a new woman. She is given a new name, a new dwelling, and must learn to speak all over again. This, too, is common in initiation ceremonies found the world over. In one West African tribe, for instance, young male initiates drink a sacred brew which cause them to lose consciousness, whereupon they are taken into a special place deep in the jungle. When they wakes, they have forgotten their past and must be taught to speak, walk, and feed themselves. They return to the tribe with new names and new roles, transformed from boys into men.

The safe return from the jungle, the forest, the spirit world, or the land of death often marks, in traditional tales, a time of new beginnings -- new marriage, new life, and a new season of plenty and prosperity enriched not only by earthly treasures but those carried back from the Netherworld. Thomas the Rhymer, in the old Scottish ballad, returns to the human world after seven years in the woodlands of Faerie bearing the gift of prophesy, the "tongue that will not lie." Merlin returns from his time of exile and madness in the forests of Wales with magical knowledge and the ability to speak with the animals. Odin hangs in a death-like trance for ten days from the world-tree Yggdrasil, and comes back with the secret of runes from the dark land of Niflheim.

The hero of our story has also survived a great ordeal, a rite-of-passage from a barren life into one of great fecundity -- symbolized not only by marriage and children, but also by the precious tobacco seeds she brings for her people. To a modern audience, tobacco might seem a strange gift to appear in a healing tale since we now associate the plant with addiction, cancer, and death. Yet tobacco was once a sacred plant used only for ritual purpose and prayer -- particularly as old, ceremonial strains had hallucinogenic properties. (Some tribal elders say that it's casual use for non-religious purposes is what makes it so harmful today.)

Rites-of-passage stories like the one above were cherished in pre-literate societies not only for their entertainment value, but also as mythic tools to prepare young men and women for life's ordeals. A wealth of such stories can be found marking each major transition in the human life cycle: puberty, marriage, childbirth, menopause, death. Other rites-of-passage, less predictable but equally transformative, include times of sudden change and calamity such as illness and injury, the loss of one's home, the death of a loved one, etc. These are the times when we wake, like Dante, to find ourselves in a deep, dark wood -- an image that in Jungian psychology represents an inward journey. Rites-of���passage tales point to the hidden roads that lead out of the dark again -- and remind us that at the end of the journey we're not the same person as when we started. Ascending from the Netherworld (that grey landscape of illness, grief, depression, or despair), we are "twice-born" in our return to life, carrying seeds: new wisdom, ideas, creativity and fecundity of spirit.

The poem in the picture captions is "Otherwise" by Jane Kenyon, who was born in Michigan in 1947 and died of leukemia at the age of 48. The poem comes from her collection of the same title (Grey Wolf Press, 1996); all rights reserved by the author's estate. The drawings above are by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939) and Helen Stratton (1867-1961).

The poem in the picture captions is "Otherwise" by Jane Kenyon, who was born in Michigan in 1947 and died of leukemia at the age of 48. The poem comes from her collection of the same title (Grey Wolf Press, 1996); all rights reserved by the author's estate. The drawings above are by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939) and Helen Stratton (1867-1961).

September 14, 2015

There and back again

Thank you for your patience (and all the kind messages) while I've been out of the studio due to health issues. It's good to be stepping gently back to life and work again, and I'm hoping to resume my regular posting schedule now, health and strength permitting. I'm not exactly dancing on tables yet, so work will be a little slow for a while -- but slow is better than the alternative. Between my health problems and Tilly's operation, what a strange and difficult summer it has been. But the Great Wheel turns and now it is autumn, a new season and a new beginning.