Terri Windling's Blog, page 128

October 5, 2015

Tunes for a Monday Morning

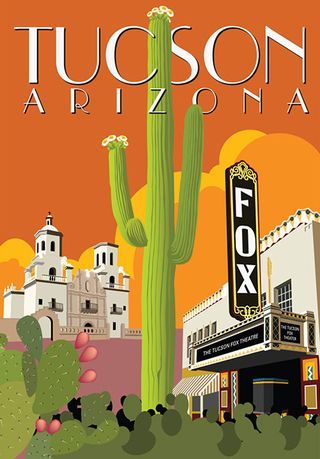

My years of living in Tucson gave me a deep love of the borderlands between southern Arizona and Mexico: the dramatic beauty of the desert landscape, the vibrancy of border culture, the complexity of its history, dark and bright. Tucson itself is a dusty modern city grown out of an old, old city, continuously settled for over 12,000 years, marked by its distinctive blend of Mexican, European, and Native American influences. Today's music comes from a much-loved Tucson band Calexico, founded by Joey Burns and John Convertino, who have been crossing cultural borders for two decades now. Calexico  encapsulates everything I love best about Tucson: the fusion of laconic cowboy and dynamic Mexican styles; the exuberant mix of Sonoran cultural traditions, aesthetics, and languages; and the ever-present dusty heat of the desert, which is almost palpable in the music.

encapsulates everything I love best about Tucson: the fusion of laconic cowboy and dynamic Mexican styles; the exuberant mix of Sonoran cultural traditions, aesthetics, and languages; and the ever-present dusty heat of the desert, which is almost palpable in the music.

Calexico's work has a strong mariachi influence, and they often join with Tuscon's great mariachi bands for hometown gigs. The single best concert I've ever been to in my life was one of these combined performances, at the Rialto Theatre in the spring of 2008: Calexico, two full mariachi bands, and a host of other musicians...there must have been 30-odd musicians on stage by the end, and it's a wonder they didn't blow the roof off the place with their energy, their passion, and their big, bold sound. It was beyond good, it was absolutely sublime, and I was high from it for days. (And sore, too, from hours of dancing.)

Above, the video for "Crystal Frontier," a song about border-crossing containing references to the La Llorona folktale.

Below, Calexico joins Mariachi Luz de Luna onstage in Tucson to perform a classic son jarocho tune, "El Cascabel."

Above, crossing musical borders of another kind: Calexico performs their song "Fortune Teller," backed by the Radio Symphonieorchester Wien and the audience, at ORF Radio Kulturhaus in Vienna, Austria (2012).

Below, Calexico and the Greek band Takim combine musical traditions for the Lizard Sound Sessions in Athens, Greece (2014).

Calexico's latest album, Edge of the Sun, was inspired by the music and culture of Mexico City. The song below, "Cumbia de Donde," is from the new album, performed with Guatemalan singer/songwriter Gaby Moreno a few months ago.

Lordy, this is making me miss Tucson this morning....

If you'd like little more music today, try the new video of Calexico and Neko Case performing "Tapping on the Line," which is also from Edge of the Sun; or "Alone Again," a classic Calexico song performed live in Germany in 2011.

September 30, 2015

The Common Life

From "The Common Life," an essay in Scott Russell Sanders' excellent collection Writing from the Center:

"The words community, communion, and communicate all derive from common, and the two syllables of common grow from separate roots, the first meaning 'together' or 'next to,' the second having to do with barter or exchange. Embodied in that word is a sense of our shared life as one of giving and receiving -- music,  touch, ideas, recipes, stories, medicine, tools, the whole range of artifacts and talents. After twenty-five years with [my wife] Ruth, that is how I have come to understand marriage, as a constant exchange of labor and love. We do not calculate who gives how much; if we had to, the marriage would be in trouble. Looking outward from this community of two, I see my life embedded in ever-larger exchanges -- those of family and friendship, neighborhood and city, countryside and county -- and on every scale there is giving and receiving, calling and answering.

touch, ideas, recipes, stories, medicine, tools, the whole range of artifacts and talents. After twenty-five years with [my wife] Ruth, that is how I have come to understand marriage, as a constant exchange of labor and love. We do not calculate who gives how much; if we had to, the marriage would be in trouble. Looking outward from this community of two, I see my life embedded in ever-larger exchanges -- those of family and friendship, neighborhood and city, countryside and county -- and on every scale there is giving and receiving, calling and answering.

"Many people shy away from community out of a fear that it may become suffocating, confining, even vicious;

and of course it may, if it grows rigid or exclusive. A healthy community is dynamic, stirred up the energies of those who already belong, open to new members and fresh influences, kept in motion by the constant battering of gifts. It is fashionable just now to speak of this open quality as 'tolerance,' but that word sounds too grudging to me -- as though, to avoid strife, we must grit our teeth and ignore whatever is strange to us. The community I desire is not grudging; it is exuberant, joyful, grounded in affection, pleasure, and mutual aid. Such a community arises not from duty or money but from the free interchange of people who share a place, share work and food, sorrows and hopes. Taking part in the common life means dwelling in a web of relationships , the many threads tugging at you while also holding you upright."

"It just may be that the most radical act we can commit is to stay home," says Terry Tempest Williams. "What does that mean to finally commit to a place, to a people, to a community? It doesn't mean it's easy, but it does mean you can live with patience, because you're not going to go away. It also means commitment to bear witness, and engaging in 'casserole diplomacy' by sharing food among neighbors, by playing with the children and mending feuds and caring for the sick. These kinds of commitment are real. They are tangible. They are not esoteric or idealistic, but rooted in the bedrock existence of where we choose to maintain our lives.

"That way we begin to know the predictability of a place. We anticipate a species long before we see them. We can chart the changes, because we have a memory of cycles and seasons; we gain a capacity for both pleasure and pain, and we find the stregnth within ourselves and each other to hold these lines. That's my definition of family. And that's my definition of love."

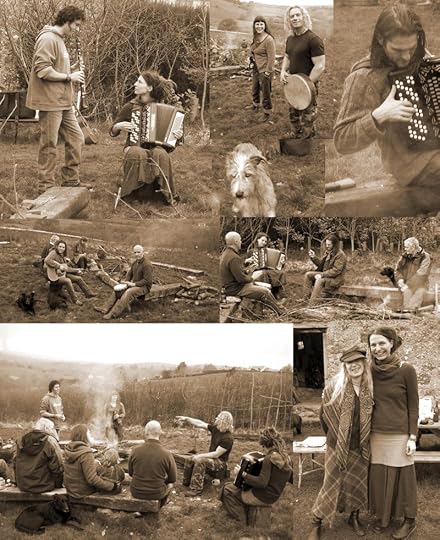

The pictures here, which hold the essence of "community" for me, come from a 2011 post about a neighborhood bonfire on the eve of the Spring Equinox...back when Howard's hair was long, and Rima Staines still had her dreadlocks, and when our beloved friend, folklorist & artist Thomas Hine, was still alive. It feels so long ago now. And it feels like yesterday.

Here's what I wrote about these pictures at the time:

"Music and a bonfire on a Devon hillside to celebrate the spring equinox (Monday, March 21st) in traditional fashion. Musicians: Howard (guitar, accordion, shakers), Steve Dooley (drums), Rima Staines (accordion, clarinet, flute), Tom Hirons (clarinet, guitar), Jason of England (drum), Thomas Hine (fiddle) and Damien Hackney (not pictured, fiddle). Bonfire hosts: Jason and Ruth Olley. Dogs: Tilly, Macha, Warlock, Ash, and Pigsy. Friends, neighbors, parents, grandparents, and children. Food cooked on the fire, painted eggs, and laughter. And a whole lot warmer than it was last time. Spring is finally here."

"It was one of those March days when the sun shines hot and the wind blows cold: when it is summer in the light, and winter in the shade." - Charles Dickens

Words: The passage above by Scott Russell Sanders comes from Writing from the Center (Indiana University Press, 1995). The passage by Terry Tempest Williams comes from an interview by Derrick Jensen in Listening to the Land: Conversations about Nature, Culture, and Ethos (Chelsea Green, 2004). All rights reserved by the authors. Picture: "The Visitors," a watercolor painting by Rima Staines.

Flying off...

I'll be out of the studio on Friday due to family commitments, but back next week with more on the theme of borders, and also on the Handless Maiden folk tale. Have a good weekend.

Drawing above: Bird child and friends.

September 29, 2015

The enclosure of wild time

Just as Commons land creates a physical border between private property and wilderness (discussed here yesterday), traditional carnivals, festivals, and folk pageants create a metaphorical border between the measured clock-time of ordinary life and the "wild time" of the mythic realm. But this cultural Commons has also been effected by Britain's history of Enclosures, as Jay Griffiths explains in the following passage from her book Pip, Pip, a cultural study of time:

"In Britain there were once hundreds of carnivals: blessing-of-the-mead days; hare-pie-scrambling days and cake-and-ale ceremonies; there were Hobby Horse Days and Horn Dance Days, with their pagan hunting associations and symbolic suggestions of fertility rites; there were Well-Dressing days, Cock-Squoiling days (or 'throwing-at-cocks'); there were Doling days and days for 'beating the bounds' of the parish; wassailing the apple trees and playing duck-apple at Halloween; burning the clavie (tar barrel) at new year or 'Hallooing Largesse' (where, in East Anglia, the Lord of the Harvest traditionally led a troup of people to serenade householders, seeking money), all colored the course of the year. Some of these are pre-Christian; some are medieval or later. Many of them have survived in some form -- often as 'just' a children's game.

"At Somerset's Punkie Night, at the end of October, children made punkies (lanterns) out of mangel-wurzels (a large kind of beet) and went knocking on people's doors for money or candles. This was one of the many ancient mischief nights of the year, when children played up gleefully, changing shop signs or taking gates  off hinges:

off hinges:

Give us a light, give us a light.

If you don't you'll get a fright...

is the children's refrain; an ancient threat this, playing a trick if you're not treated. Guisers (children disguising themselves at Halloween) in Scotland sang:

If ye dinnae let us in,

We will bash yer windies in.

"Whuppity Scooorie in Lanark is a festival, believed to have survived from pagan times, during which as much noise as possible was made to scare off evil spirits and protect crops; latterly it is acted out by children who, started by a peal of bells, swing paper balls at each other and scramble for pennies. Up-Helly-Aa is a Shetland Isles festival, dating back to Viking times, when a thirty-foot model Viking ship, complete with banners, shields and a bow of a dragon's head, is taken down to the sea by torchlight, then the torches are flung in and it blazes across the water, representing the dead heroes sent to Valhalla in a burning ship. Garland Day at Abbotsbury in Dorset is a ceremony to bless the fishing boats at the opening of the mackerel fishing season which had strong hints of pagan sacrifice in its thousand-year history, though now it is, like so many other festivals, just a children's game."

"Many festivals chime with the seasons of the agricultural year and of the natural world," notes Griffiths, "the life and death cycle of vegetation as, for example, the Obby Oss on May Day at Padstow in Cornwall, where the Oss dances, dies, resurrects, and dances again. There are festivals marking the death of winter, or bringing in the summer, there are cyclic (and sacrificial) nature-festivals for the corn spirit wherever corn is grown."

"Festival time, traditionally, binds communities together, knitting them to their land, each area tootling its own festive tune, accented with dialect voices specific to certain places and describing a 'vernacular time.' Thus one area's festival calendar could have been different from the calendar of a neighboring locale. Festival-time could further delineate not only the physical geography but also the economic geography of an area, protecting rights of access or land-use, particularly -- in the past -- in such customs as the 'beating of the bounds' of a parish or village."

"The beating of the bounds, or processioning, as Bob Bushaway says in By Rite: Custom, Ceremony and Community in England 1700-1880, 'provided the community with a mental map of the parish...which was the collective memory of the community.' These festivals tied a society to its past, its land and its rights to that land. But, as Bushaway shows, these customs disappeared, up and down the country, as a result of one thing: enclosures."

"Pre-enclosure," Griffiths continues, "other customs concerned with common land, with the rights of gleaning, wood-gathering or access, were vigorously upheld. Cheese-rolling ceremonies, for instance, used festival-time to mark such rights; when the access was denied, so was the festival At Shapwick Marsh at Sturminster Marshall, a 'feast of Sillabub' was held. It was joint-stock merry-making,' so one person might bring the milk of one cow, another the milk of three, while yet another might bring the wine. With the 1845 enclosure, this custom disappeared and many other festivals of commons were outlawed.

"Before enclosures, festivals were vigorously convivial, as numerous chronicles show; they were off-license times, drunken, licentious and rude, ranging from mid-summer ales to apple-tree wassailing, from autumn mead-mowing to May Day liaisons. And the Victorian middle-classes hated it. Just as land was literally fenced off and enclosed, so the spirit of carnival-time was metaphorically enclosed, repressed and fenced in by Victorian morality: no drinking, no bawdiness, no sex. The common -- very vulgar -- character of festival was increasingly outlawed and fenced off from the commoners and turned over to the land-owning middle classes in the form of the queasy, fluttery remains of Victorian festival...The lewd and the loud were disallowed. The acts and the spirit of enclosure tried to suppress the broad, unenclosed, unfettered, unbounded exuberance of the vulgar at large."

"Before enclosures, festivals were vigorously convivial, as numerous chronicles show; they were off-license times, drunken, licentious and rude, ranging from mid-summer ales to apple-tree wassailing, from autumn mead-mowing to May Day liaisons. And the Victorian middle-classes hated it. Just as land was literally fenced off and enclosed, so the spirit of carnival-time was metaphorically enclosed, repressed and fenced in by Victorian morality: no drinking, no bawdiness, no sex. The common -- very vulgar -- character of festival was increasingly outlawed and fenced off from the commoners and turned over to the land-owning middle classes in the form of the queasy, fluttery remains of Victorian festival...The lewd and the loud were disallowed. The acts and the spirit of enclosure tried to suppress the broad, unenclosed, unfettered, unbounded exuberance of the vulgar at large."

The photograph in the first half of this post come from last spring's May Day procession here in Chagford -- where a group of us, led by folk musician & scholar Andy Letcher, are working to revive this old folkloric tradition. That's Andy on the bagpipes, Jason of England as the Jack-in-the-Green, Suzi Crockford as the Queen of May, and my husband Howard as the Obby Oss. The photographs are by Ashley Wengraf, Ian Atherton, Ruth Olley, and Simon Blackbourn. (Run your cursor over the images for picture descriptions and credits.)

"Few festivals are more flamboyantly vulgar than May Day or Beltane," says Griffiths. "One pagan festival which the disapproving church did not -- could not -- colonize, it kept its raw smell of sexual license and its populist grass roots appeal....Beltane was celebrated with huge bonfires, the Lord and the Queen of May (who, in the Middle Ages, was often a man dressed as a woman) and Spring was personified by the Green Man -- the  Wild Man or Jack-in- the-Green. Dressed in leaves, he carried a huge horn. (Enough said.) The Maypole, the phallic pole planted in mother earth, was the key symbol of the day.

Wild Man or Jack-in- the-Green. Dressed in leaves, he carried a huge horn. (Enough said.) The Maypole, the phallic pole planted in mother earth, was the key symbol of the day.

"Then came the Puritans, sniffing the rank sexuality, decrying the Maypole as 'this stinking idol'; and in 1644 the Long Parliament banned all Maypoles. They also objected to the social reversal of carnival [men dressed as women, fools as kings, etc.]; to the Puritans, an attack on the status quo was almost as disgusting as sex. After the Restoration, England's most famous Maypole was erected in London's Strand in 1661; a stonking hundred and thirty feet high, all streamers and garlands, making people wild with delight, it stood for over fifty merry years. But Isaac Newton put a stop to it. In 1717, he bought the Maypole to use as a post for a telescope to penetrate the darkness of the night. In the 19th century, the Victorians infantalized May Day, making it a children's festival to emphasize innocence, of all things.

"But the festival of Beltane and the whole spirit of carnival is robust. Coming from the earth itself, it erupts, whether puritans and politicians like it or not. In rural areas, you can still find Beltane celebrated, complete with Green Men, Maypoles, and Fools."

More information on the history of May Day can be found in this previous post.

Our village is a place where festivals tend to erupt at the drop of a hat, and everyone seems to have well-stocked box of dress-up clothes in their closet. Despite a tiny population (roughly 2500 people, and a whole lot of sheep), Chagford hosts an annual film festival, a music festival, a bi-annual literary festival, a summer carnival, and plenty of other events besides, and kids grow up here thinking it's perfectly ordinary to dance in the streets on a regular basis. Perhaps it's no coincidence that we 've also held on to our Common lands, and many here still gather to "beat the bounds," affirming the boundaries of the parish and the timeless ties of community life.

The photographs below are by Simon Blackbourn, taken just last weekend on the final night of the Chagford Film Festival, celebrating Indian film and dance this year. Please visit Simon's website to see more of his beautiful work.

Pictures: Many thanks to the photographers who allowed their work to appear here. The black-and-white photos and the Film Festival photos are all by Simon Blackbourn; the May Day photos were taken by various folks. You'll find credits in the picture captions (run your cursor over the images to see them). The photos without credits were snapped on the fly by me, on Suzi Crockford's camera. Words: The passage by Jay Griffiths comes from Pip, Pip: A Sideways Look at Time (Flamingo, 1999), highly recommended. All rights to the text & imagery above are reserved by their respective creators.

Pictures: Many thanks to the photographers who allowed their work to appear here. The black-and-white photos and the Film Festival photos are all by Simon Blackbourn; the May Day photos were taken by various folks. You'll find credits in the picture captions (run your cursor over the images to see them). The photos without credits were snapped on the fly by me, on Suzi Crockford's camera. Words: The passage by Jay Griffiths comes from Pip, Pip: A Sideways Look at Time (Flamingo, 1999), highly recommended. All rights to the text & imagery above are reserved by their respective creators.

Enclosure of the Commons: the borders that keep us out

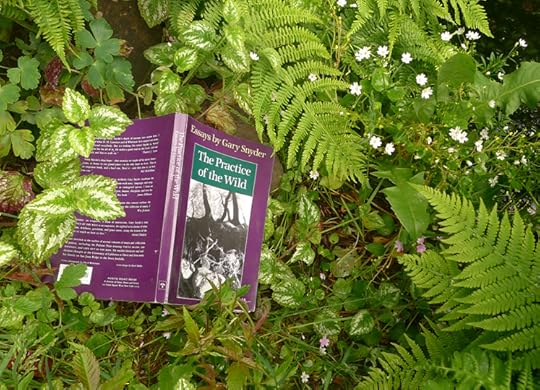

Historically, the Commons straddles the border between private space and unmanaged wilderness. Last week, we looked at the history of the English Commons via a passage from Lewis Hyde's fine book Common as Air. (If you missed it, go here. The text is quoted in the picture captions; run your cursor over the images to read it.) Today, I'd like to dig a little deeper into the subject with the help of Gary Snyder, Jay Griffiths, and George Monbiot.

"There is a well-documented history of the commons in relation to the village economies of Europe and England," writers Synder in his influential book The Practice of the Wild. "In England from the time of the Norman Conquest the enfeoffed knights and overlords began to gain control over many local commons. Legislations (the Statute of Merton, 1235) came to their support. From the 15th century on the landlord class, working with urban mercantile guilds and government offices, increasingly fenced off village-held land and turned it over to private interests. The enclosure movement was backed by big wool corporations, who found profit from sheep to be much greater than that of farming. The wool business, with its exports to the Continent, was an early agribusiness that had a destructive effect on the soils and dislodged peasants. The arguments for enclosure in England -- efficiency, higher production -- ignored social and ecological effects and served to cripple the sustainable agriculture of some districts.

" The enclosure movement was stepped up again in the 18th century," Snyder continues; "between 1709 and 1869 almost five million acres were transferred to private ownership, one acre in every seven. After 1869 there was a sudden reversal of sentiment called the 'open space movement' which ultimately halted enclosures and managed to preserve, via a spectacular lawsuit against the lords of fourteen manors, the Epping Forest.

"Karl Polyani says that the enclosures of the 18th century created a population of rural homeless who were forced in their desperation to become the world's first industrial working class. The enclosures were tragic both for the human community and for natural ecosystems. The fact that England now has the least forest and wildlife of all the nations of Europe has much to do with the enclosures. The takeover of common lands on the European plain also began about 500 years ago, but one-third of Europe is still not privatized. A survival of commons practices in Swedish law allows anyone to enter private farmland to pick berries or mushrooms, to cross on foot, and to camp out of sight of the house....The environmental history of Europe and Asia seems to indicate that the best management of commons land was that which was locally based. The ancient severe and often irreversible deforestation of the Mediterranean Basin was an extreme case of the misuse of the commons by forces that had taken its management away from regional villages."

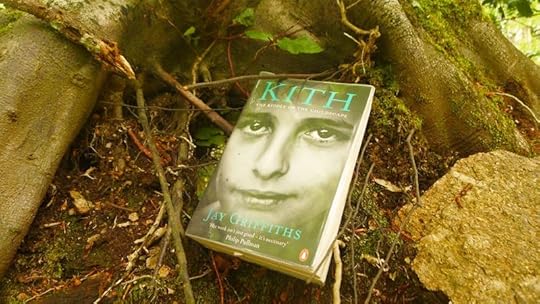

In Kith, her fine book on the cultural history of childhood, Jay Griffiths gives us a more personal view of the Enclosure of the Commons through the eyes of the great 18th century nature poet John Clare, whose heart (and mental health) were broken by the loss of lands he'd roamed as a child in Helpston, Northamptonshire:

"Born in 1793 to a sense of freedom as unenclosed as 'nature's wide and common sky,' John Clare knew that the open air was his to breathe, the open water his to drink and the open land, as far as his knowledge of it extended, his to wander, and he began to write poetry of such lucid openness that it can best be described as light: his poems are translucent to nature, which shines through his work like May sunlight through beech leaves. Clare writes of the land as if he were a belonging of the land, as if it owned him, which is an idea one hears often in indigenous communities. His childhood belonged to that land and to its creatures; he knew them all and felt known in turn. One day, Clare writes, he wandered and rambled 'til I got out of my knowledge when the very wildflowers and birds seemed to forget me.'

"And then, to his utter anguish, came the Enclosures, the acts of cruelty by which the common land was fenced off by the wealthy and privatized for the profit of the few. The Enclosures threw the peasantry into that acute poverty which would scar Clare's own life and mind so deeply."

"Between 1809 and 1820," George Monbiot explains (in an essay on Clare published in 2012), "acts of enclosure granted the local landowners permission to fence the fields, the heaths and woods, excluding the people who had worked and played in them. Almost everything Clare loved was torn away. The ancient trees were felled, the scrub and furze were cleared, the rivers were canalized, the marshes drained, the natural curves of the land straightened and squared. Farming became more profitable, but many of the people of Helpston -- especially those who depended on the commons for their survival -- were deprived of their living. The places in which the people held their ceremonies and celebrated the passing of the seasons were fenced off. The community, like the land, was parcelled up, rationalized, atomized. I have watched the same process breaking up the Maasai of east Africa.

"Clare documents both the destruction of place and people and the gradual collapse of his own state of mind.

Inclosure came and trampled on the grave

Of labour's rights and left the poor a slave ���

And birds and trees and flowers without a name

I sighed when lawless law's enclosure came.

"As Jonathan Bate records in his magnificent biography, there were several possible causes of the 'madness' that had Clare removed to an asylum in 1837: bipolar disorder, a blow to the head, malaria (then a common complaint on the edge of the fens). But it seems to me that a contributing factor must have been the loss of almost all he knew and loved. His work is a remarkable document of life before and after social and environmental collapse, and the anomie that resulted.

"What Clare suffered was the fate of indigenous peoples torn from their land and belonging everywhere. His identity crisis, descent into mental agony and alcohol abuse, are familiar blights in reservations and outback shanties the world over.

"His loss was surely enough to drive almost anyone mad; our loss surely enough to drive us all a little mad. For while economic rationalization and growth have helped to deliver us from a remarkable range of ills, they have also torn us from our moorings, atomized and alienated us, sent us out, each in his different way, to seek our own identities. We have gained unimagined freedoms, we have lost unimagined freedoms -- a paradox Clare explores in his wonderful poem The Fallen Elm."

"The Acts of Enclosure," Griffiths concurs, "signified the enclosure and destructive of [Clare's] spirit as well as the land. Winged for the simplest of raptures, he now limped at the fences erected by the 'little minds' of the wealthy.

"His own psyche had been as open as the footpaths of his childhood, paths which wend their way 'As sweet as morning leading night astray' but with sudden brutality. 'These paths are now stopt -- ' and

Each little tyrant with his little sign

Shows, where man claims, earth glows no more divine.' "

Words: The text today comes from Gary Snyder's seminal essay "The Place, the Region, and the Commons," published in his essay collection The Practice of the Wild (North Point Press, 1990); from "The Patron Saint of Childhood" in Jay Griffith's book Kith: The Riddle of the Childscape (Hamilton Hamish, 2013); and from George Monbiot's essay "John Clare, the poet of the environmental crisis -- 200 years ago," published in The Guardian (July 9, 2012). All rights reserved by the authors. Pictures: The photographs are of Tilly roaming Padley and Nattadon Commons in the edge-lands of our village. The painting is a possible portrait of John Clare, artist unknown, circa 1840.

Words: The text today comes from Gary Snyder's seminal essay "The Place, the Region, and the Commons," published in his essay collection The Practice of the Wild (North Point Press, 1990); from "The Patron Saint of Childhood" in Jay Griffith's book Kith: The Riddle of the Childscape (Hamilton Hamish, 2013); and from George Monbiot's essay "John Clare, the poet of the environmental crisis -- 200 years ago," published in The Guardian (July 9, 2012). All rights reserved by the authors. Pictures: The photographs are of Tilly roaming Padley and Nattadon Commons in the edge-lands of our village. The painting is a possible portrait of John Clare, artist unknown, circa 1840.

September 27, 2015

Tunes for a Monday Morning

In keeping to the theme of "borders," I've been thinking about musical traditions that crossed from one land to another along with immigrants, slaves, and refugees: the folk music of the British Isles, for example, which transformed into bluegrass in the eastern mountains of America, and the African rhythms that turned into American blues and gospel, and then rock-and-roll.

Cajun music is a another good example. The Cajuns of Louisiana are descended from the French (and French M��tis) Acadians who settled the Canadian Maritimes, and were then forcible deported by the British in  the Great Expulsion of 1755���1764. Although they were deported to a wide variety of places (some families split up and sent to different destinations), many of them eventually made their way down to Louisiana, a colony then under French control, where they settled among the French Creoles already living in the area. Cajun music evolved from the French ballads and dance tunes carried south by the Acadians -- as opposed to the multi-ethnic Creole music known as Zydeco, which evolved from a blend of French, African American, Native American, Spanish, and other influences.

the Great Expulsion of 1755���1764. Although they were deported to a wide variety of places (some families split up and sent to different destinations), many of them eventually made their way down to Louisiana, a colony then under French control, where they settled among the French Creoles already living in the area. Cajun music evolved from the French ballads and dance tunes carried south by the Acadians -- as opposed to the multi-ethnic Creole music known as Zydeco, which evolved from a blend of French, African American, Native American, Spanish, and other influences.

Above: Michael Doucet, from the great Cajun band BeauSoleil, performs "Eunice Two-step," a Cajun classic, for the BBC's TransAtlantic Sessions program in 2012, accompanied by Aly Bain, Jerry Douglas, Sharon Shannon, Russ Barenberg, and others. Doucet comes from Lafayette, Louisiana, and has been performing with BeauSoleil since 1977.

Below: "Let's Talk About Drinking, Not About Getting Married" by the Pine Leaf Boys, from southern Lousiana. They've released seven albums to date, the most recent being Danser (2013).

Above: "Les Oiseaux Vont Chante" by The Red Stick Ramblers, from Baton Rouge. The band formed in 1999, released eight wonderful albums of Cajun and Western Swing, and disbanded in 2006. Several members then went on to create The Revelers, along with members of The Pine Leaf Boys.

Below: "Blue Moon Special" performed by The Lost Bayou Ramblers, from Broussard, Arnaudville, and New Orleans, who play an energetic mix of Cajun, Zydeco, Western Swing and Rock-&-Roll -- primarily in French, though this particular song is sung in both French and English. They've released eight albums and EPs, the most recent being Gasa Gasa Live (2014).

I'm afraid my choice of music today (limited to songs for which good videos exist) might give the impression that Cajun musicians are exclusively white and male -- which is not at all the case, although you'll certainly  find a much stronger black presence on the Zydeco end of Lousiana's music scene. Notable women playing Cajun music include Ann Savoy, Lisa Haley, Cheryl Cormier, The Magnolia Sisters, and Rosie Ledet...plus, of course, the great Queen Ida over on the Zydeco side.

find a much stronger black presence on the Zydeco end of Lousiana's music scene. Notable women playing Cajun music include Ann Savoy, Lisa Haley, Cheryl Cormier, The Magnolia Sisters, and Rosie Ledet...plus, of course, the great Queen Ida over on the Zydeco side.

Let's end today with Cedric Watson and his band, Bijou Creole, who play a mix of Cajun and Zydeco. The video below was filmed at the Festival de Pontchartrain earlier this year, where they were joined by D��sir��e Champagne, on vocals and washboard. (The title of the song is unlisted.) Although Watson hails from San Felipe, Texas, he's been immersed in Creole music since he was 19, and is now based in Lafayette, Louisiana. His aim is to "resurrect the ancient sounds of the French and Spanish contra dance and bourr�� alongside the spiritual rhythms of the Congo tribes of West Africa, who were sold as slaves in the Carribean and Louisiana by the French and Spanish," playing everything from forgotten Creole melodies to modern Cajun and Zydeco songs.

Whenever non-Americans casually dismiss American culture based on media-promulgated stereotypes, I always want to ask: "But which America?" Hollywood and Fox News are no more representative of our enormous and diverse country than any of its thousands of other parts. Cajun and Creole culture are America too, and one reason (among many) why I still love it so much.

September 24, 2015

Crossing borders

We human beings are clannish and tribal by nature (as are many other animal species, of course), and in our creation of families and communities that can be a beautiful thing, but our compulsion for drawing boundaries and rigorously patrolling them too often goes a step too far. We see this everywhere, played out on large stages and small, from the geo-political borders of the current refugee crisis, causing anguish for so many, to the painful social borders of our teenage years, separating the cool kids from the losers, the jocks from the nerds, the rich from the poor, the tribe from the Other in a thousand different ways.

In Wednesday's post, Scott Russell Sanders reminded us that fighting for diversity in our social endeavors is not unrelated to conserving the exuberant diversity of the natural world; while on Tuesday, Rob Cowen spoke out for the beauty and vitality of edge-lands and borderlands, where two worlds come together, where the lines between us and the Other blur -- whatever that Other may be.

In the publishing industry, we have a small-stage example of borderlines and border controls, for not only are books categorized and segregated into genres, but those genres are then formed into a class system, with certain works of "serious" literature penned by canonical authors at the very top and other forms of fiction -- "chick lit" or romance, for example -- ranked near the bottom. And woe betide the author who steps outside of his or her class...er, I mean genre.

This is not to say there is no value in categorization, as linguist Eve Sweetser points out in an essay for the Interstitial Arts Foundation:

"Scholars across various schools...agree that the human neural system is a categorization system," writes Sweetser. "It���s evolved to take in stimuli and group them according to similarities and differences that have proven useful to human animals and their ancestors. If we didn���t constantly categorize new stimuli relative to our extant category system, we���d be back to the condition of a newborn -- most things would be  brand-new every, time and we���d have to start over with identifying every new entity we encounter. It���s categorization -- and I mean routinized, established, unconscious categorization -- which lets us know that a chair is a chair, a floor is a floor, a book is a book, so that we can get on with life instead of needing to grab (and probably lick) every new object to see what it���s like.

brand-new every, time and we���d have to start over with identifying every new entity we encounter. It���s categorization -- and I mean routinized, established, unconscious categorization -- which lets us know that a chair is a chair, a floor is a floor, a book is a book, so that we can get on with life instead of needing to grab (and probably lick) every new object to see what it���s like.

"The same is true of art and literature. If I didn���t have genre expectations -- and general expectations based on previously encountered texts -- I would not be a sophisticated reader, able to notice intertextuality, enjoy creativity, differentiate expected from unexpected elements, and helpfully fill in background from traditional expectations about a genre. Caroline Stevermer once told me that male readers of her novel Sorcery and Cecelia [an epistolary novel that borrows from fantasy literature and Regency romance] (co-written with Patricia Wrede), expressed enjoyment of the book���s wit and humor -- but puzzlement over the fact that the authors made it so obvious, so soon, who was going to marry whom. To female readers, more familiar with the romance genre, the obviousness of Wrede and Stevermer���s heroes as matches for the heroines was part of the spoof on that genre. When you see the tall, dark, fascinating but arrogant guy, and sparks flying between him and the heroine, the ending should be predictable. If we didn���t have entrenched categories, we���d have nothing to play with, nothing to play off. It would all be starting over again, every time."

The problem, of course, is not the genre boundary per se, but when those boundary walls are so rigidly enforced that crossing over them is difficult or impossible: when, for example, writers working in children's or genre fiction are routinely passed over for literary prizes, grants, and fellowships, no matter how good or ground-breaking their books may be; or when a mainstream writer attempts to work in a genre of lower status and is viewed as slumming.

This is changing, thank heavens. I no longer dread being asked what I write at literary events; the word "fantasy" no longer provokes an awkward silence and immediate dismissal as an artist of any worth. (To be perfectly honest, this does still happen, but not each and every time, and I count that progress.) Millions of readers have embraced books by J.K. Rowling and Phillip Pullman (among others) without becoming social pariahs, or somehow incapable of reading A.S. Byatt as well. And, best of all, a new generation of writers has grown perfectly comfortable with slipping back and forth among genres, or dwelling in the wild borderlands between them, creating works that gleefully defy expectations and easy categorization. This is precisely the kind of work that the Interstitial Arts Foundation was set up to champion, and I recommend their website, online magazine, and books, if you're not already familiar with them.

Writer and academic Theodora Goss wrote the following piece on literary borders for the IAF, and has kindly given me permission to reprint it here:

Crossing Borders, by Night

by Theodora Goss

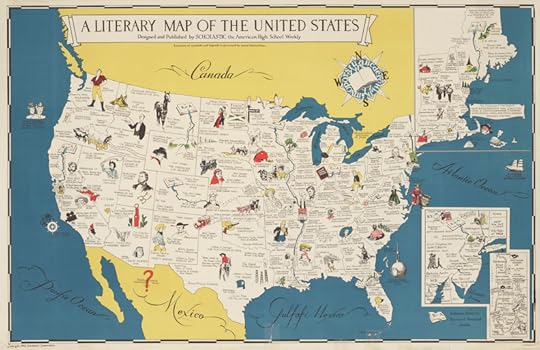

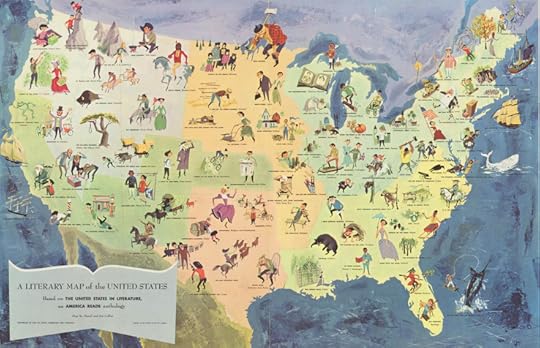

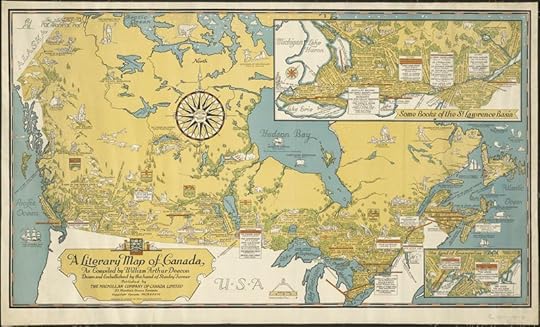

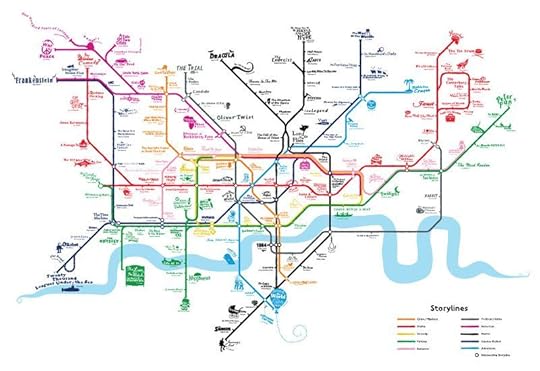

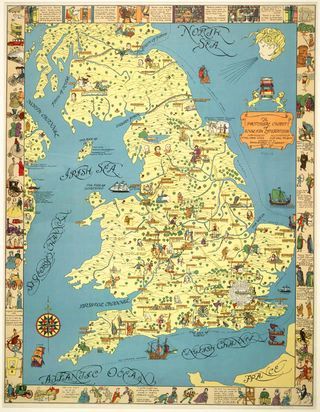

When I was a child growing up in America, I liked to read books with maps: The Wind in the Willows, The Chronicles of Narnia, The Hobbit. These books were contiguous countries. By putting down one and picking up another, I could cross from the River Bank to Middle Earth. I did not know there were borders. No weasel asked for my travel papers, no orc searched my luggage. In literature, at least, you could travel freely.

When I was a child growing up in America, I liked to read books with maps: The Wind in the Willows, The Chronicles of Narnia, The Hobbit. These books were contiguous countries. By putting down one and picking up another, I could cross from the River Bank to Middle Earth. I did not know there were borders. No weasel asked for my travel papers, no orc searched my luggage. In literature, at least, you could travel freely.

Later, as a student studying literature, I was told there were borders indeed: national (English, American, colonial), temporal (Romantic, Victorian, Modern), generic (fantastic, realistic). Some countries (the novel) you could travel to readily. The drinking water was safe, no immunizations were required. For some countries (the gothic), there was a travel advisory. The hotels were not up to standard; the trains would not run on time. Some countries (the romance) one did not visit except as an anthropologist, to observe the strange behavior of its inhabitants.

And there were border guards (although they were called professors), to examine your travel papers as carefully as a man in an olive uniform with a red star on his cap. They could not stop you from crossing the border, but they would tell you what had been left out of your luggage, what was superfluous. Why the journey was a terrible idea in the first place.

And there were border guards (although they were called professors), to examine your travel papers as carefully as a man in an olive uniform with a red star on his cap. They could not stop you from crossing the border, but they would tell you what had been left out of your luggage, what was superfluous. Why the journey was a terrible idea in the first place.

My problem is not with borders, although they are often badly drawn, so that villages within sight of each other, whose inhabitants have intermarried for generations, are assigned to different countries, or Jane Austen, who acknowledged the influence of Ann Radcliffe, is placed in a different tradition.

My problem is with the guards who say, "You cannot cross the border." Because when borders are closed, those on either side experience immobility and claustrophobia, and those who cross them (illegally, by night) suffer incalculable loss.

My aunt has a diplomatic passport. When she crosses the border, she need not wait in line. Her luggage is never searched.

May we all, in life as in literature, be accorded a similar status.

I'd like to conclude today with a passage from an essay by Jeff VanderMeer, pointing out how life itself can be interstitial, "filled with juxtaposed moments that remind us of just how strange and wonderful and full of contradiction the world can be," when we value the borderlands themselves and not just the places that our boundaries divide.

"We talk of borders and interstices, corridors and edges," he writes. "It seems to me that the very act of creating, whether it���s music or fiction or painting, sculptures or performances, is by definition to stand upon the edge, offering the world something that we���ve seen or heard on the other side. Presenting it, we become the bridge, mirror, threshold, messenger: We elect to become the in-between. "

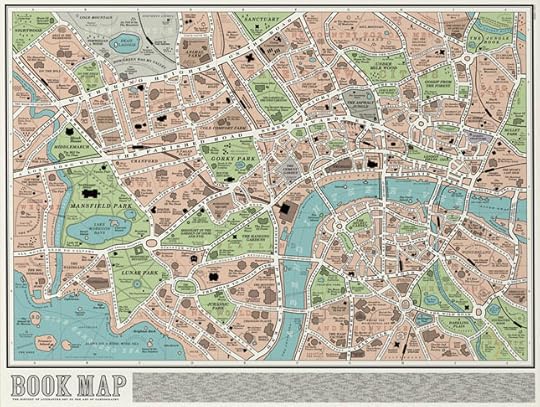

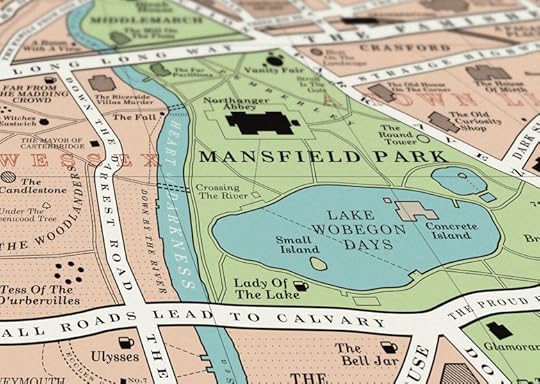

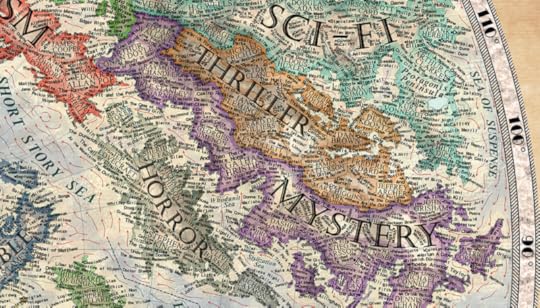

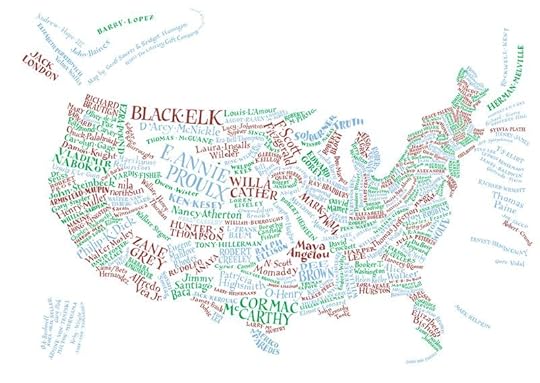

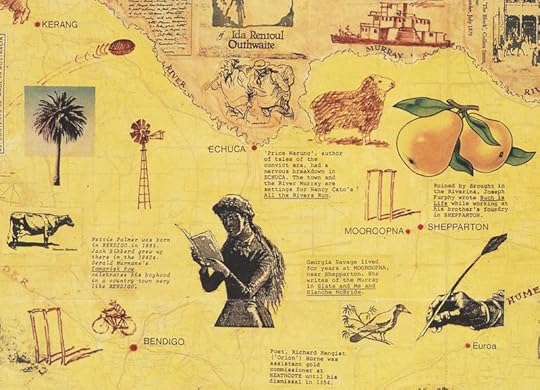

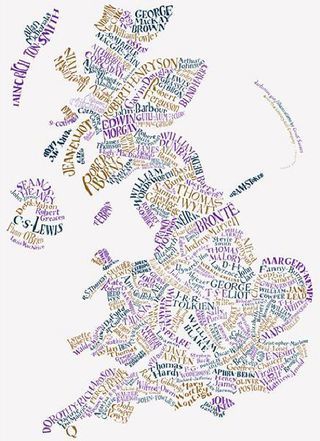

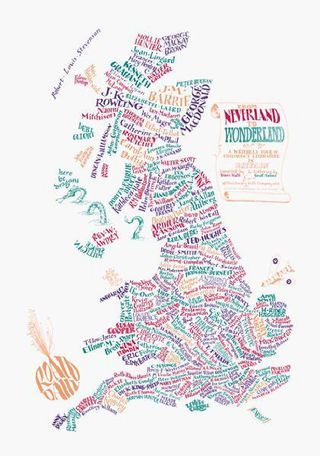

The titles of the maps pictured here can be found in the picture captions, along with artist credits. If you're a fan of maps, I recommend the Bodleian Map Room blog, and the Literary Maps exhibition on the University of Michigan Library site. Next week on Myth & Moor: more on borders, edge-lands, and the folklore of the in-between.

Where dreams are born

For today's post on the subject of edge-lands and borders, I'd like to send you to another web page to listen to a podcast of Ellen Kushner exploring "Borders: The Debatable Lands" in an episode of her award-winning radio program, Sound & Spirit. Here's the episode description:

"Sound & Spirit invites you to walk the Borderlands: a shared space between two worlds, a place where they meet and combine to make something new and vital. Explore the lively music and blend of traditions of the Tex/Mex border [and the English/Scottish border], the misty border between myth and reality where dreams are born, and the borders in our lives when we pass from one stage of life to the next."

Ellen's brilliant series has ended, but past episodes are available online. Go here to have a listen. I also recommend two related episodes of Sound & Spirit, Exile and Homesickness, about those who have crossed over the border and cannot go home again.

Photographs above: Ellen and Tilly in my studio, on one of her many visits to Chagford.

Photographs above: Ellen and Tilly in my studio, on one of her many visits to Chagford.

September 23, 2015

The Blessing of Otters

One of the mythic borderlands I'm especially drawn to (as evidenced by my writing and art over the decades) is the place where humans and animals meet: as neighbors, as cousins who speak each other's language, as shape-shifters in each other's skins.

"Long ago the trees thought they were people," says Tulalip storyteller Johnny Moses, recounting a traditional Native America tale. "Long ago the mountains thought they were people. Long ago the animals thought they were people. Someday they will say, 'long ago the humans thought they were people.' "

In "Voyageur," a gorgeous essay by Scott Russell Sanders, the writer and his daughter watch otters during a camping trip in the geographic borderlands between Minnesota and Ontario. What was it that kept him riveted to the spot, watching the animals with such intense fascination? What did the otters mean to him, and what did he want from them?

In "Voyageur," a gorgeous essay by Scott Russell Sanders, the writer and his daughter watch otters during a camping trip in the geographic borderlands between Minnesota and Ontario. What was it that kept him riveted to the spot, watching the animals with such intense fascination? What did the otters mean to him, and what did he want from them?

Not their hides, not their meat, not even a photograph, says Saunders, "although I found them surpassingly beautiful. I wanted their company. I desired their instruction -- as if, by watching them, I might learn to belong somewhere as they so thoroughly belonged here. I yearned to slip out of my skin and into theirs, to feel the world for a spell through their senses, to think otter thoughts, and then to slide back into myself, a bit wiser for the journey.

"In tales of shamans the world over, men and women make just such leaps, into hawks or snakes or bears, and then back into human shape, their vision enlarged, their sympathy deepened. I am a poor sort of shaman. My shape never changes, except, year by year, to wrinkle and sag. I did not become an otter,  even for an instant. But the yearning to leap across the distance, the reaching out in imagination to a fellow creature, seems to me a worthy impulse, perhaps the most encouraging and distinctive one we have. It is the same impulse that moves us to reach out to one another across differences of race or gender, age or class. What I desired from the otters was also what I most wanted from my daughter and from the friends with whom we were canoeing, and it is what I have always desired from neighbors and strangers. I wanted their blessing. I wanted to dwell alongside them with understanding and grace. I wanted them to go about their lives in my presence as though I were kin to them, no matter how much I might differ from them outwardly."

even for an instant. But the yearning to leap across the distance, the reaching out in imagination to a fellow creature, seems to me a worthy impulse, perhaps the most encouraging and distinctive one we have. It is the same impulse that moves us to reach out to one another across differences of race or gender, age or class. What I desired from the otters was also what I most wanted from my daughter and from the friends with whom we were canoeing, and it is what I have always desired from neighbors and strangers. I wanted their blessing. I wanted to dwell alongside them with understanding and grace. I wanted them to go about their lives in my presence as though I were kin to them, no matter how much I might differ from them outwardly."

Later in essay, Sanders writes about two loons who wake him in the middle of the night, "wailing back and forth like two blues singers demented by love," and the bald eagle who watches their progress down the river from its perch on a dead tree's branch. What did the eagle see, he wonders?

"Not food, surely, and not much of a threat, or it would have flown. Did it see us as fellow creatures? Or merely as drifting shapes, no more consequential than clouds? Exchanging  stares with this great bird, I dimly recalled a passage from Walden that I would look up after my return to the company of books: 'What distant and different beings in the various mansions of the universe are contemplating the same one at the same moment! Nature and human life are as various as our several constitutions. Who shall say what prospect life offers to another? Could a greater miracle take place than for us to look through each other's eyes for an instant?'

stares with this great bird, I dimly recalled a passage from Walden that I would look up after my return to the company of books: 'What distant and different beings in the various mansions of the universe are contemplating the same one at the same moment! Nature and human life are as various as our several constitutions. Who shall say what prospect life offers to another? Could a greater miracle take place than for us to look through each other's eyes for an instant?'

"Neuroscience may one day pull off that miracle," Sanders continues, "giving us access to other eyes, other minds. For the present, however, we must rely on our native sight, on patient observation, on hunches and empathy. By empathy, I do not mean the projecting of human films onto nature's screens, turning grizzly bears into teddy bears, crickets into choristers, grass into lawns; I mean the shaman's leap, a going out of oneself into the inwardness of other beings.

"The longing I heard in the cries of the loons was not just a feathered version of mine, but neither was it wholly alien. It is risky to speak of courting birds as blues singers, of diving otters as children taking turns on a slide. But it is even riskier to pretend we have nothing in common with the rest of  nature, as though we alone, the chosen species, were centers of feeling and thought. We cannot speak of that common ground without casting threads of metaphor outward from what we know and what we do not know.

nature, as though we alone, the chosen species, were centers of feeling and thought. We cannot speak of that common ground without casting threads of metaphor outward from what we know and what we do not know.

"An eagle is other, but it is also alive, bright with sensation, attuned to the world, and we respond to that vitality wherever we find it, in bird or beetle, in moose or lowly moss. Edward O. Wilson has given this impulse a lovely name, biophilia, which he defines as the urge 'to explore and affiliate with life.' Of course, like the coupled dragonflies that skimmed past our canoes or like osprey hunting fish, we seek other creatures for survival. Yet even if biophilia is an evolutionary gift, like the kangaroo's leap or the peacock's tail, our fascination with living things carries us beyond the requirements of eating and mating. In that excess, that free curiosity, there may be a healing power. The urge to explore has scattered humans across the whole earth -- to the peril of many species, including our own; perhaps the other dimension of biophilia, the desire to affiliate with life, could lead us to honor the entire fabric and repair what has been torn."

In the concludion of his essay, Sanders points out that the fellowship of all creatures "is more than a handsome metaphor. The appetite for discovering such connections is also entwined in our DNA. Science articulates in formal terms affinities that humans have sensed for ages in direct encounters with wildness. Even while we slight or slaughter members of our own species, and while we push other species toward extinction, we slowly,  painstakingly acquire knowledge that could enable us and inspire us to change our ways. Only if that knowledge begins to exert a pressure in us, and we come to feel the fellowship of all beings as potently as we feel hunger and fear, will we have any hope of creating a truly just and tolerant society, one that cherishes the land and our wild companions along with our brothers and sisters.

painstakingly acquire knowledge that could enable us and inspire us to change our ways. Only if that knowledge begins to exert a pressure in us, and we come to feel the fellowship of all beings as potently as we feel hunger and fear, will we have any hope of creating a truly just and tolerant society, one that cherishes the land and our wild companions along with our brothers and sisters.

"In America lately, we have been carrying on two parallel conversations: one about respecting human diversity, the other about preserving natural diversity. Unless we merge those conversations, both will be futile. Our efforts to honor human differences cannot succeed apart from our effort to honor the buzzing, blooming, bewildering variety of life of earth. All life rises from the same source, and so does all fellow feeling, whether the fellow moves on two legs or four, on scaly bellies or feathered wings. If we care only for human needs, we betray the land; if we care only for the earth and its wild offspring, we betray our own kind. The profusion of creatures and cultures is the most remarkable fact about our planet, and the study and stewardship of that profusion seems to me our fundamental task."

The sculptures pictured here are by the New Mexican artists Gene & Rebecca Tobey, who worked for years in a fertile partnership creating scuptures, paintings, and drawings inspired by nature and the mythic symbolism of the North American continent. (The titles of the pieces can be found in the picture captions.) Gene died of leukemia in 2006, but Rebecca carries on their beautiful work. Please visit the Tobey Studios website to see more of their collaborative art, and the Rebecca Tobey website for her current pieces.

The text quoted today comes from "Voyageurs," an essay in Writing from the Center by Scott Russell Sanders (Indiana University Press, 1997), highly recommended. All rights reserved by the author.

The text quoted today comes from "Voyageurs," an essay in Writing from the Center by Scott Russell Sanders (Indiana University Press, 1997), highly recommended. All rights reserved by the author.

September 22, 2015

On the border

Over these last months, I've been thinking a lot about edge-lands, borders, and liminal spaces, about myths of thresholds, transitions, and transformations. It's a reverie inspired by a number of different things: reading Kith by Jay Griffiths, Common Ground by Rob Cowen, Common as Air by Lewis Hyde, Meadowland by John Lewis-Stempel, and John Hupton's novel The Ballad of John Clare; re-visiting essays by Barry Lopez, Sergio Troncoso, Alan Garner and others; and working on a new story for the "Borderland" series -- all while moving through the amiguous edge-world of illness and disability.

This week's posts will focus on edge-lands and borders: physical, spiritual, and metaphorical. I'm not entirely sure where this journey is going to take us; we won't known until we've arrived. But first we must find our way through the borderlands: passing from highways to holloways and street lamps to starlight...wading through "rivers as red as blood" into Faerie...stepping through wardrobes to Narnia and crossing the hilltops to Shangri-La...although we might find the twilight lands on the borders themselves are the most interesting of all.

In his book Common Ground (which I highly recommend), Rob Cowen turns a naturalist's eye to a small patch of woodlands and fields usually dismissed as unremarkable: the neglected scrublands on the border of his Yorkshire town, where the regimented streets of housing peter out and the countryside begins.

"For many years," he tells us, "I had sought out and written about the wilderness encountered in more expected places: the rarefied national park, the desolate moor, the distant mountaintop, the sweeping coast, but I'd forgotten there is something deeper about the blurry space surrounding us where humans and nature meet. One word stayed with me: layers. Even before I'd started the process of investigating it in any depth I was aware that this edge-land was a crossing point where countless histories lay buried. There were its human narratives, the records of our long tangling with the land -- colonisation, hunting, farming, war, industry and urbanisation -- but these were only part of the story. Emeshed in every urban edge is also the continuous narrative of the subsistence of nature, pragmatic and prosaic, the million things that survive and even thrive in the fringes. This little patch of common ground was precisely that: common. And all the richer for it."

In his provocative essay "The Trouble With Wilderness," William Cronan, too, speaks up for the value of landscapes that are not remote and dramatic, nor pristine and untouched by the human hand.

"When we visit a wilderness area, " he argues, "we find ourselves surrounded by plants and animals and physical landscapes whose otherness compels our attention. In forcing us to acknowledge that they are not of our making, that they have little need or no need of our continued existence, they recall for us a creation far greater than our own. In the wilderness, we need no reminder that a tree has its own reasons for being, quite apart from us. The same is less true in the gardens we plant and tend ourselves: there it is far easier to forget the otherness of the tree. Indeed, one could almost measure wilderness by the extent to which our recognition of its otherness requires a conscious, willed act on our part. The romantic legacy means that wilderness is more a state of mind than a fact of nature, and the state of mind that today most defines wilderness is wonder. The striking power of the wild is that wonder in the face of it requires no act of will, but forces itself upon us -- as an expression of the nonhuman world experienced through the lens of our cultural history -- as proof that ours is not the only presence in the universe.

"Wilderness gets us into trouble only if we imagine that this experience of wonder and otherness is limited to the remote corners of the planet, or that it somehow depends on pristine landscapes we ourselves do not inhabit. Nothing could be more misleading. The tree in the garden is in reality no less other, no less worthy of our wonder and respect, than the tree in an ancient forest that has never known an ax or saw -- even though the tree in the forest reflects a more intricate web of ecological relationships....Our challenge is to stop thinking of such things according to a set of bipolar moral scales in which the human and nonhuman, the unnatural and the natural, the fallen and unfallen, serve as our conceptual map for understanding and valuing the world. Instead, we need to embrace the full continuum of a natural landscape that is also cultural, in which the city, the suburb, the pastoral and the wild each has its proper place, which we permit ourselves to celebrate without needlessly denigrating the others. We need to honor the Other within and the Other next door as much as we do the exotic Other that lives far away -- a lesson that applies as much to people as it does to (other) natural things."

To return to Rob Cowen's insightful and beautiful book:

"Once upon a time the edges were the place we knew best," he writes. "Times were hard and spare but the margins around homesteads, villages and towns sustained us. People grazed livestock and collected deadfall for fuel. Access and usage became enshrined as rights and recognised in law. Pigs trotted through trees during 'pannage' -- the acorn season from Michaelmas to Martinmas -- certain types of game were hunted for the table and heather and fern were cut for bedding. Mushrooms, fruits, and berries. Mushrooms, fruits and berries would be foraged and gathered for winter; honey taken from wild beehives; chestnuts hoarded, ground and stored as flour. The fringes provided playgrounds for kids and illicit bedrooms for lovers. Whether consciously or not, these spaces kept us in time and rooted to the rhythms of land and nature. Feet cloyed with clay, we oriented ourselves by rain and sun, day and night, seasons, the slow spinning of stars.

"Humans are creatures of habit," Cowen continues; "we all still go to the edges to get perspective, to be sustained and reborn. Recreation is still re-creation after a fashion, only now it occurs in largely virtual worlds. Clouds, hyper-real TV shows, 3D films, multiplayer games, online stores and social media networks -- these are today's areas of common ground, the terrains where people meet, work, hunt, play, learn, fall in love even. Ours is a world growing yet shrinking, connected yet isolated, all-knowing but without knowledge. It is one of breadth, shallowness and endless swimming through cyberspace. All is speed and surface. Digging down deeper into an overlooked patch of ground, one that (in a global sense at least) few people will ever know about and even fewer visit, felt like the antithesis to all of this. And it felt vitally important. You see, I still believe in the importance of edges. Lying just beyond our doors and fences, the emeshed borders where human and nature collide are microcosms of our world at large, an extraordinary, exquisite world that is growing closer to nature every day. These spaces reassert a vital truth: nature isn't just some remote mountain or protected park. It is all around us. It is us."

Words: The passage by Rob Cowen is from the introduction to Common Ground (Hutchinson/Random House, 2015). The passage by William Cronan is from "The Trouble With Wilderness" (Environmental History, 1995). The quotes in the picture captions are from Common as Air: Revolution, Art & Ownership by Lewis Hyde (Farrar, Straus, & Giroux, 2010). All rights to these texts are reserved by their authors. Pictures: Our own village, Chagford, still has its public commons, which is widely used and cherished. Meldon Hill, pictured here, and the land just below it are on common ground, with the village beyond nestled in a mix of private and public fields.

Words: The passage by Rob Cowen is from the introduction to Common Ground (Hutchinson/Random House, 2015). The passage by William Cronan is from "The Trouble With Wilderness" (Environmental History, 1995). The quotes in the picture captions are from Common as Air: Revolution, Art & Ownership by Lewis Hyde (Farrar, Straus, & Giroux, 2010). All rights to these texts are reserved by their authors. Pictures: Our own village, Chagford, still has its public commons, which is widely used and cherished. Meldon Hill, pictured here, and the land just below it are on common ground, with the village beyond nestled in a mix of private and public fields.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers