Terri Windling's Blog, page 127

October 16, 2015

From the archives: Crossing Over

In the following passage from Brenda Peterson's Build Me an Ark: A Life with Animals, the author is swimming with a dolphin pod on the Florida coast:

" 'Crossover' is a word scientists use to describe dolphins' soaring over seas, their traveling so free and fast, so high-spirited and almost effervescent that their sleek bodies barely skim the waves. The suggestion of splashes from tail and pectoral leaves a luminous wake across the water. For these crossover miles, the dolphins, like their human terrestrial mammal kin, belong more to the element of air than the sea....

"Held in [the dolphins'] fluid embrace, I pulled my arms close against my sides and our communal speed increased... Racing around the lagoon, I opened my eyes again to see nothing but an emerald underwater blur. And then I remembered what I had either forgotten long ago or never quite fully realized. This feeling of being carried along by other animals was familiar.

"Animals had carried me all my life," Peterson continues. "I was a crossover -- carried along in the generous and instructive slipstream of other species. And I had always navigated my life with them in mind, going between the human and animal worlds -- a crossover myself. By including animals in my life I was always engaging with the Other, imagining the animal mind and life. For almost half a century, my bond with animals had shaped my character and revealed the world to me. At every turning point in my life an animal had mirrored or influenced my fate. Mine was not simply a life with other animals, but a life because of animals.

"It had been this way since my beginning, born on a forest lookout station in the High Sierras, surrounded by millions of acres of wilderness and many more animals than humans. Since infancy, the first faces I imprinted, the first faces I ever really loved, were animal."

If you haven't yet read Brenda's luminous work (which includes fiction, essays, memoirs, and anthologies), please do seek it out. Her website is here, and her blog (on books, nature, seal watching and more) is here.

Words:

The post above originally appeared in August, 2012. I'm re-visiting it today in the context of our recent discussions on borders and border-crossing, and also in case newcomers to Myth & Moor are unfamiliar with Brenda's wonderful work. Today's passage comes from her essay collection Build Me an Ark (W.W. Norton, 2001); all rights reserved by the author. Pictures: The drawings & paintings above are "Mermaid in Flight" by Fay Ku, "Sky Pack" by Julianna Swaney, "Fox Confessor" by Julie Morstad, and "Hank" by Carson Ellis. Please visit their websites to see more of their art. All rights to the imagery here reserved by the artists.

October 14, 2015

No post today

Chagford lost one of its own yesterday, and I simply have no words in me. Today, this candle, and this silence, is for our friend, her family, and all who loved her.

"Unable are the loved to die. For love is immortality." - Emily Dickinson

October 13, 2015

Chasing inspiration

In her well-known 2009 TED Talk on the daemons of creativity, Elizabeth Gilbert relates the following story:

"I met the extraordinary American poet Ruth Stone, who's now in her 90s. She's been a poet her entire life. She told me that when she was growing up in rural Virginia, she would be out working in the fields, and she would feel and hear a poem coming at her from over the landscape. She said it was like a thunderous train of air, coming barreling down at her over the landscape, and she'd feel it coming, because it would shake the earth under her feet. She knew that she had only one thing to do at that point, and that was to, in her words, 'run like hell.' And then she would run like hell to the house, chased by this poem; she had to get to a piece of paper and a pencil fast enough so that when it thundered through her, she could collect it, and grab it on the page. Other times she wouldn't be fast enough, so she'd be running and running but she wouldn't get to the house, and the poem would barrel through her and she would miss it. It would continue on across the landscape, looking, as she put it 'for another poet.'

"And then there were times -- this is the piece I never forgot -- where she would almost miss it. So, she's running to the house, and she's looking for the paper, and the poem passes through her...and she grabs a pencil just as it's going through her...and then, she said, she would reach out with her other hand and she would catch it. She would catch the poem by its tail, and she would pull it backwards into her body as she was transcribing on the page. And in these instances, the poem would come up on the page perfect and intact but backwards, from the last word to the first."

Haruki Murakami (as mentioned in a previous post on this subject) is more likely to be chased by his muse than the other way around:

"A short story I have written long ago would barge into my house in the middle of the night, shake me awake and shout, 'Hey, this is no time for sleeping! You can't forget me, there's still more to write!' Impelled by that voice, I would find myself writing a novel."

For Sylvia Lindsteadt, inspiration rises from the land, and her deep, daily engagement with it:

"I've always loved tales of magic, of other worlds, or other times. These are the stories, in one way or another, I've always tried to write. Stories where the edge between girl and tea-plant is thin. Where deserts reflect back dreams. Where women with heron-feet come into bedrooms on storm clouds and demand impossible things. But all through college on the East Coast [of America], so far from the native mountains and seaside of my California upbringing, I couldn't find my voice in those stories. I couldn't find that river-otter, lagoon-slick tangle of joy and purpose, sand-dune belly-sliding and all, that deep abandon, which accompanies the creation of truly meaningful work.

"Then, two summers ago, in the Big Sur mountains with my family, after just having read Gary Snyder's Mountains and Rivers Without End, and while driving past the Point Sur Lighthouse (a truly magical almost-island, fog wrapped and rough, with a lighthouse at the tip), I was knocked over the head with a sudden revelation. THIS place, the place I was born and raised, was my muse. THIS place, these redwood forests, manzanita and oak woodlands, coyote brush and sage chaparral, wild coasts, fire-roads dusty and wide, was my muse...

"[T]he muse is not something intangible that floats through the ether and grabs my shoulders from time to time, spilling inspiration. The muse IS the land. I write to bring stories of place -- that nexus of animal, human, plant, land and weather -- back into our literary and cultural landscape. I write to learn the land I live in and on more deeply, and I write to give voice to the more than human world, both as it intersects with our human lives, and as it exists far beyond, in all of its mystery, in all of its true magic."

Poet Marilyn Krysl explains the process of inspiration like this:

"Writing, whether fiction, poetry, memoir or nonfiction, isn���t something we 'do,' "Writing is something that happens to us.

"The word inspire comes from the Latin inspirare, meaning to breathe. The word means 'to blow upon, to infuse by breathing, to inhale.' So to be inspired is to be graced by inspiration. Where does inspiration come from? It comes from the windy, breathy air that surrounds us -- and without which we could not live.

"We don���t 'do' writing. We are each a 'place' on the earth where from time to time writing happens. How lucky to be chosen to be that place."

Indeed.

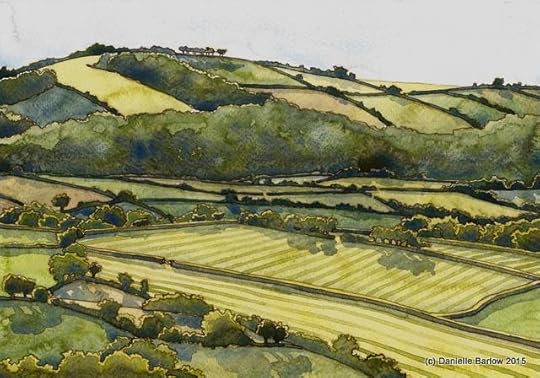

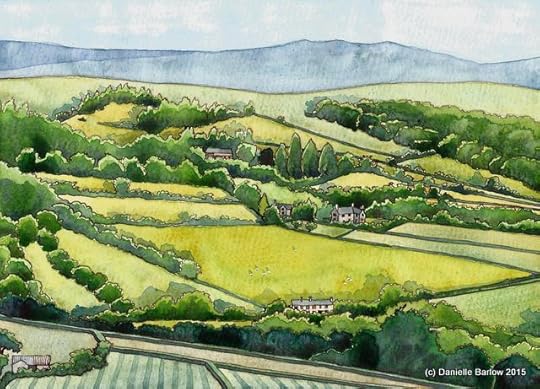

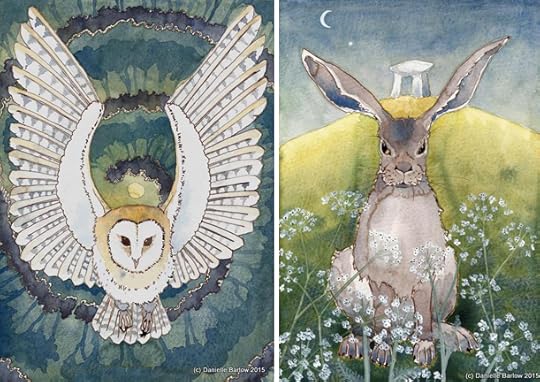

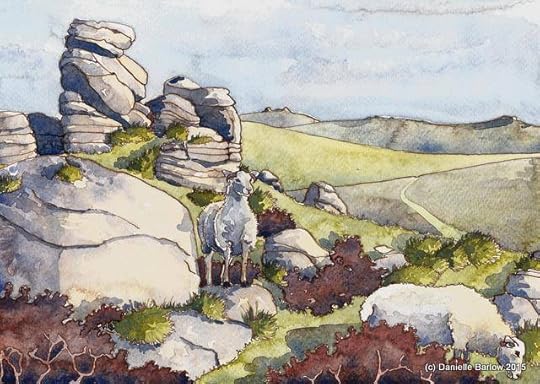

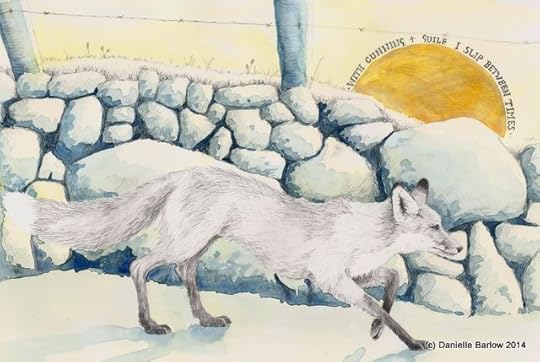

The beautiful watercolor paintings featured here today are by my friend and neighbor Danielle Barlow, whose Muse roams among the fields, farmyards, hedgerows and old stone circles of the Devon landscape. Please visit her lovely blog, Notes from the Rookery, to see more paintings, drawings, and fabric art, as well as magical photographs of her animals, paintings-in-progress, and Dartmoor through the seasons.

You can also follow her work on Facebook and Etsy.

The passage by Elizabeth Gilbert is quoted from "Your elusive creative genius," a TED Talk filmed in 2009 and highly recommended. I confess that I don't remember which article the Haruki Murakami quote comes; I jotted it down when I first read it but didn't list the source. My apologies. The passage from Sylvia Linsteadt comes from her blog post "Of Otters and Words with Roots" (Indigo Vat, July 26, 2012). The quote by Marilyn Krysl is from the poetry page of her website. All rights to the words and pictures above are reserved by their respective creators.

The passage by Elizabeth Gilbert is quoted from "Your elusive creative genius," a TED Talk filmed in 2009 and highly recommended. I confess that I don't remember which article the Haruki Murakami quote comes; I jotted it down when I first read it but didn't list the source. My apologies. The passage from Sylvia Linsteadt comes from her blog post "Of Otters and Words with Roots" (Indigo Vat, July 26, 2012). The quote by Marilyn Krysl is from the poetry page of her website. All rights to the words and pictures above are reserved by their respective creators.

On the care and feeding of daemons and muses

"If we go all the way back to the ancient world," writes Lewis Hyde in Common Air, "to the old bardic and prophetic traditions, what we find is that men and women are not thought to be authors so much as vessels through which other forces act and speak. Norse legends tell of a spring at the root of the World Tree whose water bubbles up from the underworld, carrying the dissolved memories of the dead. Odin drank from it once; that cost him an eye, but nonetheless empowered him to bestow on worthy poets the mead of inspiration. Homer is not the 'author' of the Odyssey; he disappears after the first line: 'Sing in me, Muse, and through me tell the story....' Hesiod's voice is not his own; in The Theogony he has it from the muses of Mount Helicon and in Works and Days from the muses of Pieria. Plato presents no ideas that he himself made up, only the recovered memory of things known before the great forgetting we call birth.

"Creativity in ancient China was not self-expression but an act of reverence toward earlier generations and the gods. In the Analects, Confucius says, 'I have transmitted what was taught to me without making up anything of my own. I have been faithful to and loved the Ancients.' "

As Hyde explained in an earlier book, The Gift:

"The task of setting free one's gifts was a recognized labor in the ancient world. The Romans called a person's tuletary spirit his genius. In Greece it was called a daemon. Ancient authors tell us that Socrates, for example, had a daemon who would speak up when he was about to do something that did not accord with his true nature. It was believed that each man had his idios daemon, his personal spirit which could be cultivated and developed. Apuleius, the Roman author of The Golden Ass, wrote a treatsie on the daemon/genius, and one of the things he says is that in Rome it was the custom on one's birthday to offer a sacrifice to one's own genius. A man didn't just receive gifts on his birthday, he would also give something to his guiding spirit. Respected in this way the genius made one 'genial' -- sexually potent, artistically creative, and spiritually fertile.

"According to Apuleius," he continues, "if a man cultivated his genius through such a sacrifice, it would become a lar, a protective household god, when he died. But if a man ignored his genius, it became a larva or a lemur when he died, a troublesome, restless spook that preys on the living. The genius or daemon comes to us at birth. It carries with us the fullness of our undeveloped powers. These it offers to us as we grow, and we choose whether or not to accept, which means we choose whether or not to labor in its service. For the genius has need of us. As with the elves, the spirit that brings us our gifts finds its eventual freedom only through our sacrifice, and those who do not reciprocate the gifts of their genius will leave it in bondage when they die.

"An abiding sense of gratitude moves a person to labor in the service of his daemon," Hyde concludes. "The opposite is properly called narcissism. The narcissist feels his gifts come from himself. He works to display himself, not to suffer change. An age in which no one sacrifices to his genius or daemon is an age of narcissism. The 'cult of the genius' which we have seen in this century has nothing to do with the ancient cult. The public adoration of genius turns men and women into celebrities and cuts off all commerce with the guardian spirits. We should not speak of another's genius; this is a private affair. The celebrity trades on his gifts; he does not sacrifice to them. And without that sacrifice, without the return gift, the spirit cannot be set free. In an age of narcissism the centers of culture are populated with larvae and lemurs, the spooks of unfulfilled genii."

Stephen King takes a more irreverent approach to daemons and muses in "The Writing Life":

"There is indeed a half-wild beast that lives in the thickets of each writer's imagination. It gorges on a half-cooked stew of suppositions, superstitions and half-finished stories. It's drawn by the stink of the image-making stills writers paint in their heads. The place one calls one's study or writing room is really no more than a clearing in the woods where one trains the beast (insofar as it can be trained) to come. One doesn't call it; that doesn't work. One just goes there and picks up the handiest writing implement (or turns it  on) and then waits. It usually comes, drawn by the entrancing odor of hopeful ideas. Some days it only comes as far as the edge of the clearing, relieves itself and disappears again. Other days it darts across to the waiting writer, bites him and then turns tail.

on) and then waits. It usually comes, drawn by the entrancing odor of hopeful ideas. Some days it only comes as far as the edge of the clearing, relieves itself and disappears again. Other days it darts across to the waiting writer, bites him and then turns tail.

"There may be a stretch of weeks or months when it doesn't come at all; this is called writer's block. Some writers in the throes of writer's block think their muses have died, but I don't think that happens often; I think what happens is that the writers themselves sow the edges of their clearing with poison bait to keep their muses away, often without knowing they are doing it. This may explain the extraordinarily long pause between Joseph Heller's classic novel Catch-22 and the follow-up, years later. That was called Something Happened. I always thought that what happened was Mr. Heller finally cleared away the muse repellant around his particular clearing in the woods.

"On good days, that creature comes out of the thickets and sits for a while, there in one's writing place. If one is in another place, it usually comes there (often under duress; most writers find their muses do not travel particularly well, although Truman Capote said his enjoyed motel rooms). And it gives. Some days it gives a little. Some days it gives a lot. Most days it gives just enough. During the year it took to compose my latest novel, mine was extraordinarily generous, and I am grateful.

"Okay," King admits, "that's the lyric version, so sue me. You'd lose. It's not untrue, just lyrical. It's told as if the writing were separate from the writer. It's probably not, but it often feels that way; it feels as if the process is happening on two separate levels at the same time. On one, at this very moment, I'm just sitting in a room I call my writing room. It's filled with books I love. There's a Western-motif rug on the floor. Outside is the garden. I can see my wife's daylilies. The air conditioner is soft, soft -- white noise, almost. Downstairs, my oldest grandson is coloring, and cupboards are opening and closing. I can smell gingerbread. Laura Cantrell is on the iTunes, singing 'Wasted.'

"This is the room, but it's also the clearing," writes King. "My muse is here. It's a she. Scruffy little mutt has been around for years, and how I love her, fleas and all. She gives me the words. She is not used to being regarded so directly, but she still gives me the words. She is doing it now. That's the other level, and that's the mystery. Everything in your head kicks up a notch, and the words rise naturally to fill their places. If it's a story, you find the scene and the texture in the scene. That first level -- the world of my room, my books, my rug, the smell of the gingerbread -- fades even more. This is a real thing I'm talking about, not a romanticization. As someone who has written with chronic pain, I can tell you that when it's good, it's better than the best pill.

"But there's no shortcut to getting there. You can build yourself the world's most wonderful writer's studio, load it up with state-of-the-art computer equipment, and nothing will happen unless you've put in your time in that clearing, waiting for Scruffy to come and sit by your leg. Or bite it and run away."

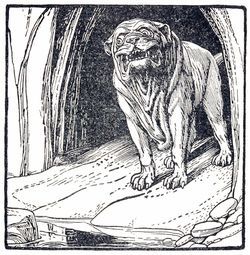

Words: The passages by Lewis Hyde are from Common As Air: Revolution, Art, & Ownership (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2010) and The Gift: Creativity & the Artist in the Modern World (Vintage, 1983). The passage by Stephen King is from "The Writing Life" (The Washington Post, October 1, 2006). The poem excerpt in the picture captions is from "October" by Audre Lorde, Chosen Poems, Old & New (W.W. Norton, 1982). All rights reserved by the authors. Pictures: The drawing is by John D. Batten (1860-1932). The photographs were taken a couple of weeks back on a walk with Howard & Tilly by the River Teign, near Fingle Bridge.

Words: The passages by Lewis Hyde are from Common As Air: Revolution, Art, & Ownership (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2010) and The Gift: Creativity & the Artist in the Modern World (Vintage, 1983). The passage by Stephen King is from "The Writing Life" (The Washington Post, October 1, 2006). The poem excerpt in the picture captions is from "October" by Audre Lorde, Chosen Poems, Old & New (W.W. Norton, 1982). All rights reserved by the authors. Pictures: The drawing is by John D. Batten (1860-1932). The photographs were taken a couple of weeks back on a walk with Howard & Tilly by the River Teign, near Fingle Bridge.

Related posts: "Mud and the Muse," "On Artistic Inspiration," and "One of Those Days."

October 12, 2015

Recommended reading and viewing

In several posts over the last couple of weeks we discussed the history of the Enclosures here in Britain (in which millions of acres of Common land were transferred into private hands for the profit of the few), and how this affected folkloric traditions dependent on the Commons and communal ways of living.

The selling off of the UK's public lands, resources, and services continues to this day, of course. I recommend "Pete," a short video by Matt Hopkins that has just been posted on the Aeon Magazine site, looking at the loss of communal spaces and affordable housing in London -- and how this effects young people, including those making attempting to make their living in the arts. Which is never easy at the best of times....

Real England by Paul Kingsnorth, one of the founders of The Dark Mountain Project, is well worth a read on the subject of modern Enclosures too.

October 11, 2015

Tunes for a Monday Morning

I've chosen the music of Scottish singer/songwriter Karine Polwart this week, simply because her albums have been in heavy rotation in my studio lately. I love her blend of original and traditional tunes, the political and social concerns she brings to her work, and the way that even her most contemporary songs contain the old rhythms of folk poetry.

Above: "Cover Your Eyes," a beautiful and heart-breaking piece performed by Polwart and her band at the Shrewbury Folk Festival in 2012. The song comes from her fifth album, Traces, and she explains its genesis in the video above.

Below: a performance of "Sorry," a song she wrote for her fourth album, An Earthly Spell. Polwart is accompanied here by her usual touring partners: Steven Polwart (her brother) and Inge Thomson, as well as Signy Jakobsdottir on percussion. The video is taken from her DVD, Here's Where Tomorrow Starts, filmed on the Scottish Borders in 2011.

Above: "The Fire Thief," written for the BBC Radio Ballads project in 2006 and performed on Scottish television in 2010. Though steeped in the language of old folk balladry and changeling tales, it's a song about the AIDs virus -- a haunting melding of past and present.

Below: an impromptu performance of her lovely song "River's Run" (which appeared in a previous post in 2013. It brought back sweet memories to revisit it this morning.) Polwart is accompanied by Steve and Inge once again, filmed in Surrey in 2009.

One last piece:

The Cairn String Quartet, from Glasgow, perform their version of Polwart's "Tears For Lot's Wife," in 2013. The song comes from her fifth album, Traces, and you can hear the original here.

If you'd like a little more music this morning, try Polwart's "The Tongue That Cannot Lie" (a song that always reminds me of the fate of Thomas the Rhymer); and her rendition of The Wife of Usher's Well, a ghostly Child Ballad from the Scottish Borders. The latter piece is on Polwart's third album, Fairest Floo'er, consisting primarily of traditional songs and ballads, and absolutely splendid.

October 8, 2015

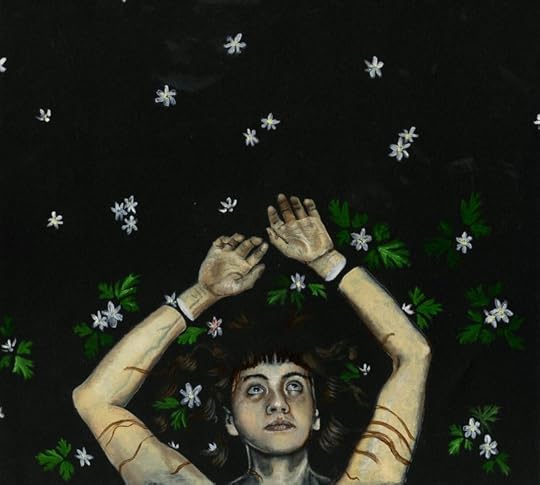

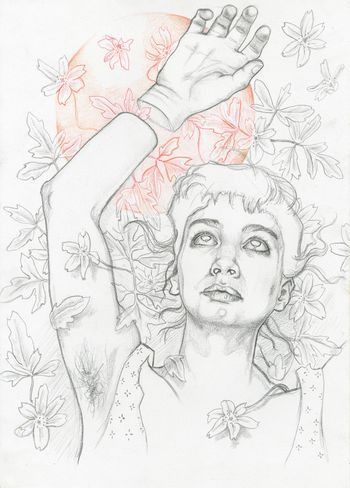

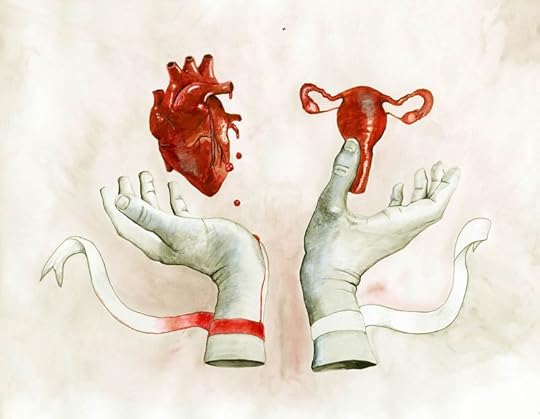

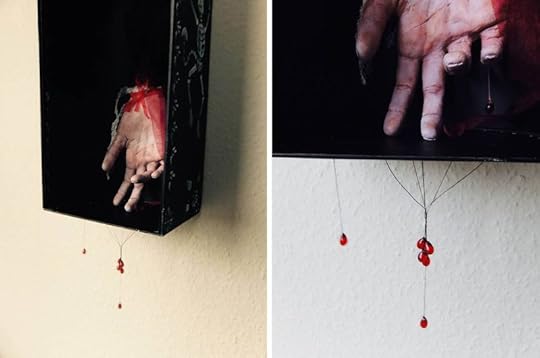

The Handless Maiden: an art project by Nomi McLeod

The Handless Maiden is a powerful fairy tale known by a number of names in cultures around the world: The Girl With No Hands, The Girl With Silver Hands, and The Armless Maiden, among others. In this Guest Post, mythic artist Nomi MacLeod discusses the genesis of the extraordinary work you see here. If you're unfamiliar with the Handless Maiden story, you can read the Brothers Grimm version online on the SurLaLune Fairy Tales site. - Terri

by Nomi McLeod

I first encountered the Handless Maiden when I was 29, and

pregnant for the second time.

It still strikes me as odd that I was

an adult before I encountered the tale; I sat thinking, 'How is it that I've never heard this before?' The imagery reminded me at once of Shakespeare's Lavinia from Titus Andronicus -- raped, mutilated

and left (seemingly) utterly powerless: she can neither

speak nor write, lacking both

tongue and hands.

The particular version I sat

listening to was delivered by storyteller Martin Shaw. After hearing his rendition, I sought out written versions of 'The Handless Maiden' and discovered many variants. Some of them spoke to me even more clearly, some less so.

Like Lavinia, who finds a way to spell out the names of her attackers, the Maiden of the story gradually regains her power. Her hands grow back -- gradually, in Martin Shaw's re-telling, and by a sudden miracle in other versions.

What for me was particularly poignant was that the Maiden's hands, and therefore her autonomy and power, are restored after she becomes a mother.

As I first sat listening to the story, I was almost 20 weeks pregnant. This was the exact gestation at which my first baby, a little girl, had died in my womb. To say her death and stillbirth left me wounded does  little to convey my grief, nor the psychic disturbance the events caused me. The loss of my unborn child made me starkly aware of how little control a woman has over the processes of gestation and birth. For me, the imagery of the handless mother resonated perfectly with my experience of pregnancy after the loss of my first baby. As well as being an awe-inspiring, often beautiful experience, pregnancy has a darker side, one often not spoken about. Whether or not a woman has lost a baby, during pregnancy she is highly likely to experience times of fear about this possibility, and anxiety about birth, her body, her change in status, her relationship to a partner and/or the world at large.

little to convey my grief, nor the psychic disturbance the events caused me. The loss of my unborn child made me starkly aware of how little control a woman has over the processes of gestation and birth. For me, the imagery of the handless mother resonated perfectly with my experience of pregnancy after the loss of my first baby. As well as being an awe-inspiring, often beautiful experience, pregnancy has a darker side, one often not spoken about. Whether or not a woman has lost a baby, during pregnancy she is highly likely to experience times of fear about this possibility, and anxiety about birth, her body, her change in status, her relationship to a partner and/or the world at large.

After my second pregnancy resulted in the birth of a healthy daughter, I was overjoyed. Yet all I experienced remained unresolved. To explore my feelings, I made a puppet of the Maiden and her baby, which you can see here on Clive Hicks-Jenkins' Puppet Challenge blog.

The image of the Maiden, mutilated, handless (read: powerless) with her child, spoke deeply to that part of my mind which responds to symbols and magic.

I found I could not stop with just the one puppet. I began to make more images from the story, using mediums I rarely use (oils, printing, sculpture), and even materials I had not considered before, such as prints on birch bark...

...as I explored the symbolic nature of the Maiden's wanderings in the forest.

My image-making culminated in a representation of the moment when the young mother's hands miraculously grow back. In the version of the story which spoke most strongly to me, she has been exiled to the woods with her newborn child. Breastfeeding, and thirsty, she attempts to stoop to a river and drink. Her baby slips from her handless grasp and falls into the water. Forgetting her mutilation in her panic and despair, she plunges her stumps into the water. Her hands grow back and she saves her child.

I could not save my first baby. But through the mothering of my second, and the making of art, I find that, slowly, slowly, my hands are growing back.

About the artist: Nomi McLeod is a multi-media artist and aerialist who lives here in Devon, on the other side of our village, with her partner (musician and author Andy Letcher) and their child. "I work a lot with self portraiture," she writes, "imagining, dreaming and reflecting on my life and my place in it. The natural world, mortality and the connection between these two are a constant source of inspiration." To see more of her beautiful work, please visit her Air and Parchment blog -- or, if you're anywhere near Bristol, UK, you can also see it in the "When Death Comes" exhibition, which runs through Sunday. Please note that a ll rights to the text and art above are reserved by the artist.

About the fairy tale: For more information on The Handless Maiden (and its variants), see my previous post, "The Armless Maiden and Forest Sanctuary," and Midori Snyder's very fine essay, "The Armless Maiden and the Hero's Journey."

"Into the Woods" series, 42: Twilight Tales

Between the setting of the sun and the black of night, dusk is a potent, magical time, for in its eerie half-light (according to folklore found around the globe) one can cross the borders dividing our mundane world from supernatural realms.

When I was a child, I longed to discover a doorway into Faerieland or a wardrobe leading to Narnia...and I actually attempted to find one, in the twilight hour of a midsummer's eve. I remember it still: sitting huddled in the shadows, escaping the chaos of a troubled home, determined to conjure a portal to a magic realm by sheer force of will. I failed, of course. But like many children hungry for a deeper connection with the spirit-filled unknown, what I couldn't find in New Jersey that night I discovered in the pages of fantasy books...and, later, in the study of folklore and a life-time of wandering the landscape of myth.

My younger self may have been in the wrong place, but I'd instinctively managed to chose the right time, for twilight, according to British and other folk tales, contains powerful magic.

"Anytime that is 'betwixt and between' or transitional is the faeries' favorite time," says painter and mythographer Brian Froud. "They inhabit transitional spaces: the bottom of the garden, existing in the place  between man-made cultivation and wilderness. Look for them in the space between nurture and nature, they are to be found at all boarders and boundaries, or on the edges of water where it is neither land nor lake, neither path nor pond. They come when we are half-asleep. They come at moments when we least expect them; when our rational mind balances with the fluid irrational."

between man-made cultivation and wilderness. Look for them in the space between nurture and nature, they are to be found at all boarders and boundaries, or on the edges of water where it is neither land nor lake, neither path nor pond. They come when we are half-asleep. They come at moments when we least expect them; when our rational mind balances with the fluid irrational."

In myth, it is rarely easy to cross from the human world to the Otherlands, whatever those Otherlands may be: Faerie, Tir-na-nog, the Spirit World, the Underworld and the Realm of the Dead. Gods and guardians of the threshold are the border guards who will either stamp your passport or block your way -- such as Janus, the god of doorways, gateways, passages, beginnings and endings in Roman mythology; or Cardea, with whom he is often paired, the goddess of door-hinges, domestic thresholds, passageways of the body, and liminal states. According to Robert Graves' mad and brilliant book, The White Goddess, Cardea was propitiated at weddings by lighting torches of hawthorne, her sacred tree, for she had the power "to open what is shut; and shut what is open." (She was thus associated with virginity, virginity's end, and, consequently, with childbirth.)

A wide variety of guardian figures around the world (gods, faeries, supernatural spirits) regulate passage through mystic thresholds, and access to sacred groves, glens, springs and wells. Some of them guard whole forests and mountains, while others protect individual trees,  hills, stones, bridges, crossings, and crossroads. Myth and folklore tells us these guardians can be appeased, tricked, outwitted, even slain -- but usually at a price which is somewhat higher than one wants to pay.

hills, stones, bridges, crossings, and crossroads. Myth and folklore tells us these guardians can be appeased, tricked, outwitted, even slain -- but usually at a price which is somewhat higher than one wants to pay.

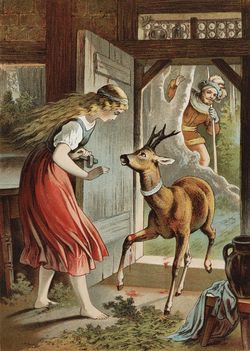

Sometimes it is the land itself preventing casual passage across mythic boundaries. In the Scottish ballad "Thomas the Rhymer," a river of human blood stands between Faerieland and the mortal world, and Thomas must pay the price of seven years servitude to make that crossing. In the Germany fairy tale "Brother and Sister," an enchanted stream must be crossed three times in the siblings' flight through the deep, dark woods. They are sternly warned not to stop and drink -- but the brother breaks this magical taboo and is transformed into a deer. In other tales, one princess must climb seven iron mountains to reach the land where her love is imprisoned; another must trick the winds into carrying her where her feet cannot. A magical hedge of thorns is the boundary between Sleeping Beauty's castle and the everyday world, and it cannot be penetrated until time, blood, and prophesy all stand aligned.

Trickster is a rare mythic figure who crosses borders and boundaries with ease. In his various guises around the globe (Hermes, Mercury, Loki, Legba, Maui, Monkey, Anansi, Coyote, Raven, Manabozho, Br'er Rabbit, Puck, etc.) he moves back and forth between the realms carrying messages, stealing fire and cattle, making mischief on both sides of the border, dancing in the borderlands between, and (in his role of Psychopomp) leading the dead in their journey to the Underworld or the Spirit Lands.

Tricksters, Lewis Hyde points out, "are the lords of in-between. A trickster does not live near the hearth; he does not live in the halls of justice, the soldier's tent, the shaman's hut, the monastery. He passes through each of these when there is a moment of silence, and he enlivens each with mischief, but he is not their guiding spirit. He is the spirit of the doorway leading out, and of the crossroad at the edge of town (the one where a little market springs up). He is the spirit of the road at dusk, the one that runs from one town to another and belongs to neither. There are strangers on that road, and thieves, and in the underbrush a sly beast whose stomach has not heard about your letters of safe passage....

"Travellers used to mark such roads with cairns," Hyde continues, "each adding a stone to the pile in passing. The name Hermes once meant 'he of the stone heap,' which tells us that the cairn is more than a trail marker -- it is an altar to the forces that govern these spaces of heightened uncertainty, and to the intelligence needed to negotiate them. Hitchhikers who make it safely home have somewhere paid homage to Hermes."

Many fantasy novels grow from the desire to go beyond the fields we know or to find the hidden door in the hedge. Unlike Tolkien's Lord of the Rings or Le Guin's Earthsea books, set entirely in invented landscapes, these tales cross the border from ordinary life into Otherworlds of magic and wonder -- a device used most famously in C.S. Lewis's Chronicles of Narnia, but also in Andre Norton's Witchworld books, Pamela Dean's Secret Country series, Joyce Ballou Gregorian's Tredana trilogy, Charles de Lint's Moonheart, Phillip Pullman's His Dark Materials trilogy (although Lyra's Oxford, or Will's, aren't exactly our own), and numerous others. There are also those books in which movement across the border goes in the opposite direction, spilling magic from the Otherworld into our own, such as Robert Holdstock's Mythago Wood series, Patricia McKillp's Solstice Wood, and William Hope Hodgson's The House on the Borderlands (1908). In his classic novel The King of Elfland's Daughter (1924), the great Irish fantasist Lord Dunsany focused on the borderland itself: the tricksy, shifting landscape squeezed between the mortal and magical realms -- a device that was then irreverently updated by the Bordertown urban fantasy series, with its motorcycle-riding and rave-dancing elves, humans, and halflings in a crumbling city at the edge-lands of Faerie.

Magical Realist works on the mainstream shelves also make use of border-crossing themes. Rick Collignon's The Journal of Antonio Montoya, Pat Mora's House of Houses, Alfredo Vea Jr.'s La Maravilla, Kathleen Alcala's Spirits of the Ordinary, and Susan Power's The Grass Dancer are all extraordinary books where the membrane between the worlds of the living and the dead is thin and torn; as is Leslie Marmon Silko's wide-ranging refutation of borders, The Almanac of the Dead. In Thomas King's Green Grass, Running Water, Trickster crosses easily from the mythic to modern world; while in Antelope Wife by Louise Erdrich these worlds are stitched together in the intricate patterns of Indian beadwork.

As myth, folklore, and fairy tales remind us, the border between any two things is a traditional place of enchantment: a bridge between two banks of a river; the silvery light between night and day; the liminal moment between dreaming and waking; the motion of shape-shifting transformation; and all those interstitial realms where cultures, myths, landscapes, languages, art forms, and genres meet.

We cross the border every time we step from the mundane world to the lands of myth; from mainstream culture to the pages of a mythological study or a magical tale. As a folklorist and fantasist, I cannot resist an unknown road or an open gate. I'm still that child on a midsummer's eve, willing magic into existence.

Words: The quote by Brian Froud is from a conversation I noted down when I was editing his book Good Faeries, Bad Faeries (Simon & Schuster, 1998). The quote by Lewis Hyde is from his excellent book Trickster Makes This World: Mischief, Myth, & Art (Farrar, Straus, & Giroux, 1998). Pictures: Art credits can be found in the picture captions. (Run your cursor over the images to see them.) All rights to the text and imagery above is reserved by their respective creators. Related posts: At the Death of the Year and The Madness of Art.

Words: The quote by Brian Froud is from a conversation I noted down when I was editing his book Good Faeries, Bad Faeries (Simon & Schuster, 1998). The quote by Lewis Hyde is from his excellent book Trickster Makes This World: Mischief, Myth, & Art (Farrar, Straus, & Giroux, 1998). Pictures: Art credits can be found in the picture captions. (Run your cursor over the images to see them.) All rights to the text and imagery above is reserved by their respective creators. Related posts: At the Death of the Year and The Madness of Art.

October 7, 2015

The borderlands we inhabit

''I am in between. Trying to write to be understood by those who matter to me, yet also trying to push my mind with ideas beyond the everyday. It is another borderland I inhabit. Not quite here nor there. On good days I feel I am a bridge. On bad days I just feel alone.''

- Sergio Troncoso (Crossing Borders)

- Sergio Troncoso (Crossing Borders)

There are always moments when one feels empty and estranged.���

Such moments are most desirable,

���for it means the soul has cast its moorings and is sailing for distant places.

���This is detachment --

when the old is over and the new has not yet come. ���

If you are afraid, the state may be distressing,

���but there is really nothing to be afraid of. ���

Remember the instruction:

���Whatever you come across -���

���go beyond."

- ������Nisargadatta Maharaj

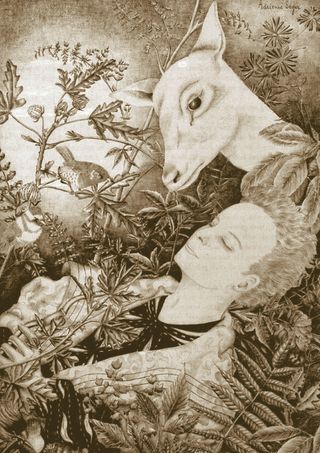

The exquisite drawing above is "Beauty and the Beast" by Virginia Lee.

The exquisite drawing above is "Beauty and the Beast" by Virginia Lee.

October 6, 2015

The borders of language

In the video above, "Between Two Worlds," the wonderful Bill Moyers (whom you may remember from his program on Joseph Campbell, The Power of Myth) interviews a friend of mine from back in my Tucson days: Luis Alberto Urrea, who now lives with his wife and children up north, in Illinois. Born in Tijuana, Mexico, Luis writes about the U.S./Mexico border region better than just about anyone, forming that work into fiction, nonfiction, and poetry, all of it highly recommended. (You'll find a discussion of his luminous novel The Hummingbird's Daughter in this previous post.)

In featuring this interview, I don't want to veer our exploration of borders into the contentious realm of immigration politics -- an important topic in its own right, but one that falls beyond the purview of this blog. Rather, what I want to spotlight here are the ways that writers (and other artists) use their gifts in response to the world around them: whether it's Elif Shafak telling stories of her Turkish childhood, or Miquel Angel Blanco preserving the old lore of Spain in his library of trees, or Rachel Taylor-Beales reinterpreting selkie myths to reflect on modern tales of exile and displacement, or Jackie Morris following a falcon's journey to the human world and back into the wild.

As writers and artists we use words and paint (among other materials) to witness and re-create the world -- whether we do this directly as journalists and creators of Realist works, or indirectly (but subtly and deeply) through the symbolism of Fantasy and Mythic Arts.

In his 1998 essay "Nobody's Son," Luis had this to say about the border-crossing nature of words themselves:

"Home isn't just a place, I have learned. It is also a language. My words not only shape and define my home. Words -- not only for writers -- are home. Still, where exactly is that?

"Jimmy Santiago Baca reminds us that 'Hispanics' are immigrants in our own land. By the time time Salem was founded on Massachusetts Bay, any number of Urreas had been prowling up and down the Pacific coast of our continent for several decades. Of course, the Indian mothers of these families had been here from the start.'

"Forget about purifying the American landscape," Luis continues, "sending all those ethnic types back to their homelands. Those illegal humans. (A straw-hat fool in a pickup truck once told my Sioux brother Duane to go back where he came from. 'Where to?' Duane called. 'South Dakota?')

"The humanoids are pretty bad, but how will we get rid of all those pesky foreign words debilitating the United States?

"Those Turkish words (like coffee). Those French words (like maroon). Those Greek words (like cedar). Those Italian words (like marinate). Those African words (like marimba).

"English! It's made up of all these untidy words, man. Have you noticed?

"Native American (skunk), German (waltz), Danish (twerp), Latin (adolescent), Scottish (feckless), Dutch (waft), Caribbean (zombie), Nahuatl (ocelot), Norse (walrus), Eskimo (kayak), Tatar (horde) words! It's a glorious wreck (a good old Viking word, that).

"Glorious, I say, in all its shambling mutable beauty. People daily speak a quilt of words, and continents and nations and tribes and even enemies dance all over your mouth when you speak. The tongue seems to know no race, no affiliation, no breed, no caste, no order, no genus, no lineage. The most dedicated Klansman spews the language of his adversaries while reviling them."

"I love words so much," Luis concludes. "Thank god so many people lent us theirs or we'd be forced to point and grunt. When I start to feel the pressure of the border on me, when I meet someone who won't shake my hand because she has suddenly discovered I am half Mexican (as happened with a landlady in Boulder), I comfort myself with these words. I know how much color and beauty we Others add to the American mix."

Over here in the old world of Europe, it's both easy and fashionable to look down one's nose at the crass racism of Little Sister America...and yet the immigration and refugee crisis unfolding on European borders is not so very different.

In Britain, as in America, there are those demanding that "they" be sent back where they came from (whoever "they" may be, Syrian children or Polish carpenters); and there are those reaching out a helping hand; and there are those going about their daily lives pretending none of it is happening...not necessarily due to hard-heartedness, but, sometimes, to sheer exhaustion from what their daily lives entail.

A question that often arises in our various discussions on this blog is: What, as artists, can we do about _____ ? Whatever _____ may happen to be: displaced people fleeing war and poverty, hungry families in Foodbank queues here at home, vanishing animal habitats, oceans ailing...forests falling to the ax...and on and on and on. I have no simple answer, for it's a question I still ask myself, in one way or another, almost every damn day. But what I do know is this:

I believe that the ability to create (in any form, whether at the desk or easel -- or in the kitchen, the garden, the community hall) -- is a gift, and gifts are meant to be passed on. They are meant to be used, to be of use, and that's a geis, a wyrd, I do not take lightly.

Some of use our gifts in the direct service of activism; others, in the indirect service of creating "beauty in a broken world" (to use Terry Tempest William's phrase), as a means of lifting hearts, mending spirits, and reminding us of what we're fighting for. Either way, it is important, I think, to be mindful of what we're putting out into the world. Art can envision, conjure, build, bind, heal, witness, dignify, and illuminate. It can also destroy, distract, diminish, deflect, justify, obfuscate, and lie.

"I don't think writers are sacred," Tom Stoppard once said, "but words are. They deserve respect. If you get the right ones in the right order, you might nudge the world a little..."

And so it bears thinking about just what direction we are nudging it in.

Like Luis Urrea, Terry Tempest Williams is a writer skilled in placing "the right words in the right order," such as these, which are tacked above my desk:

"Bearing witness to both the beauty and pain of our world is a task that I want to be part of. As a writer, this is my work. By bearing witness, the story that is told can provide a healing ground. Through the art of language, the art of story, alchemy can occur. And if we choose to turn our backs, we've walked away from what it means to be human."

The beautiful art here, as you may have recognized, is by the Tucson-based photographer Stu Jenks. The top five photographs were taken in northern and southern Arizona; the lower seven in Devon and Cornwall while he was visiting us in 2013. Please go to Stu's blog to learn more about his art, music, and books.

Between Two Worlds appeared on American Public Television in 2012, and can be found online in the Moyers & Company archives. The passage by Luis Alberto Urrea comes from his essay collection

Nobody's Son

(The University of Arizona Press, 1998). The quote by Tom Stoppard is from his play

The Real Thing

(1982). The quote from Terry Tempest Williams comes from an interview in

Listening to the Land: Conversations About Nature Culture and Eros

by Derrick Jensen (Chelsea Green, 2004); you can read a longer passage from the interview here. All rights to the video, text, and imagery above are reserved by their creators.

Between Two Worlds appeared on American Public Television in 2012, and can be found online in the Moyers & Company archives. The passage by Luis Alberto Urrea comes from his essay collection

Nobody's Son

(The University of Arizona Press, 1998). The quote by Tom Stoppard is from his play

The Real Thing

(1982). The quote from Terry Tempest Williams comes from an interview in

Listening to the Land: Conversations About Nature Culture and Eros

by Derrick Jensen (Chelsea Green, 2004); you can read a longer passage from the interview here. All rights to the video, text, and imagery above are reserved by their creators.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers