Michelle Ule's Blog, page 102

September 17, 2012

A Walk in Avtar’s Brooklyn

Growing up in southern California, I thought of New York City as an exotic locale of black and white film, bluesy jazz music, glamorous theater and sophisticated books.

Growing up in southern California, I thought of New York City as an exotic locale of black and white film, bluesy jazz music, glamorous theater and sophisticated books.

I’ve visited many times and always have found something new to love.

On our most recent trip, we caught up with our niece Avtar and she took us for a walk through her Brooklyn neighborhood.

Come with us!

Why yes, trees still grow in Brooklyn. They grace the city steets and make the shops feel cooler and more friendly on a summer day.

Brooklyn boasts a multitude of cultures and ethnicities. The Russian Orthodox Church vies with a new condo building to oversee a green park.

Food ranges from Mexican–there were no Mexican restaurants in New York City when we moved upstate in 1978–

to vegetarian.

Decades ago, manufacturing filled Brooklyn and a smokestack still indicates the need for power.

Immigrants could stand on the shores–connected to Manhattan’s sparkling lights by the Brooklyn Bridge–and dream of the same fabulous images I saw from California.

The buildings are not so high here, three or four-stories more the norm, but fire escapes are still necessary.

Buildings include a touch of the whimsical.

Who would look for a baboon in Brooklyn?

Or seek encouragement from an auto shop?

It’s all there in Brooklyn–if you have the eyes to see it on a summer’s day!

September 11, 2012

Appreciating Art–It’s All in the Hands

The summer of my fourteenth year, my family spent ten weeks camping in Europe.

The summer of my fourteenth year, my family spent ten weeks camping in Europe.

My teacher mother (junior high girl’s physical education), saved her income for an entire year. My parents bought a Volkwagen camper bus in Germany and the day after school was out in June, we flew to Europe to pick it up. We returned to Los Angeles the weekend before school started in the fall.

My mother was determined her children would be exposed to culture and that meant art. The music we already had from our father.

But she didn’t know a lot about art, so she arranged for us to visit every significant art museum on the trip.

After the second or third museum, I figured I’d better find something to tell me if a painting was good or not, because I was going to be seeing a lot of them.

Because we began in Frankfurt and headed north, the first art museums featured Dutch masters and German painters. I liked the paintings that seemed to tell stories or that portrayed interesting looking people. But how to tell if a work was good or not?

Hey, art for art’s sake meant I could decide for myself. It needed to speak to me, right? Who cares what others thought?

I decided to focus on hands.

After all, if a painter could make hands look natural–like real hands–he or she probably had some skill.

I was looking at a painting by Hans Holbein, the younger, at the time. He did a fine job.

Holbein was noted for painting portraits of Henry VIII of England and his wives. That’s number three, Jane Seymour, on the right and you can see how he didn’t necessarily glamorize the woman. Her hands look real, too.

One of Holbein’s failures, however, was wife number number four, Anne of Cleves. (It’s easy to remember the wives: One divorced, one beheaded, one died. One divorced, one beheaded, one survived. Anne was a divorcee).

One of Holbein’s failures, however, was wife number number four, Anne of Cleves. (It’s easy to remember the wives: One divorced, one beheaded, one died. One divorced, one beheaded, one survived. Anne was a divorcee).

As a gawky fourteen-year-old wearing horn rimmed glassed and metal braces in 1970 Europe, I only hoped Hans Christian Anderson was right about the ugly duckling (we visited his house in Denmark, too). Anne of Cleves gave me hope. Look how real she looks, other than the odd bodice and the narrow waist. Perhaps he focused too much on her clothes?

Or maybe he felt felt sorry for a homely spinster. Henry VIII took one look at her and arranged the divorce: she was too plain in real life.

Everyone is familiar with Rembrandt but not me until that year. I took to his paintings with gusto: the moody dark colors, the surprising light–usually on a well-worn face– and the desire to portray an interesting person. He was not as adept with hands as Hans Holbein, but he made them interesting.

I took to his paintings with gusto: the moody dark colors, the surprising light–usually on a well-worn face– and the desire to portray an interesting person. He was not as adept with hands as Hans Holbein, but he made them interesting.

Vincent Van Gogh was another find–even I had heard the story of his missing ear. But in his work I found color, vibrancy, and thick enough paint to recognize technique. As I told my children later in life–”you can always tell a Van Gogh because the sky tends to be a little wild.”

His hands, however, weren’t so good.

His hands, however, weren’t so good.

That was okay. By the time we got to France, I had learned to admire other aspects of a painting beyond an artists’ skill with detailing hands.

Several years later, I visited Guadalajara, Mexico with my family. My boyfriend joined us on that trek and admitted he didn’t know much about evaluating art. I introduced him to the concept of hands as an example of an artist’s ability. We paid close attention to hands as we visited galleries and museums, and particularly liked those of Diego Rivera:

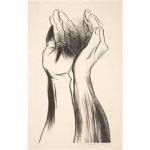

Robert fell in love with a lithograph by Jose Orozco, of interesting hands.

Robert observed about this work: “It reminds me of our sin, offering it up to God for his forgiveness.”

In that way, what he read into the painting is more important than what Orozco meant it to be.

It’s all about the hands–and what we can truly appreciate.

September 6, 2012

Art for Art’s Sake–or Someone Else?

I’m just back from a vacation in New England and New York City. Two of those days I spent at the fabulous Metropolitan Museum of Art. I loved it.

I’m just back from a vacation in New England and New York City. Two of those days I spent at the fabulous Metropolitan Museum of Art. I loved it.

I also thought parts of it absurd.

You know those sections: modern art.

Take the painting at the top of the page. What do you see?

Do you note a color? A shape? Anything else?

Are you surprised to learn the painting is called “Blue Panel?”

How about this sculpture:

I reminds me of paperclips, but it is much larger. Giant paperclips, perhaps. With my arty photo, you also get the shadow which adds depth and power to the sculpture.

Right?

Real title: Tanktotem II. David Smith welded it together in 1953. I have no idea how much the Met spent to obtain it, nor why.

I examined this one for some time, trying to decide if I saw the outstretched arm of an Indian chief pointing to something to the right. He’s wearing a buffalo skin.

Right?

Title: Untitled.

About this time, I’m ready to give up on modern art. I mean, if the artist can’t be bothered to figure out what his painting is about, why should I waste my time on it?

If the artist can’t label his or her painting in a way that makes sense to me, what am I supposed to take away from it? Could the painter at least give me a hint?

I thought I’d be able to figure out this painting when I saw the title. Here it is:

No surprise, the painter is Pablo Picasso. Can you guess what he was trying to say?

The title: Guitar and Clarinet on a Mantlepiece.

I’ve been playing the clarinet for 43 years. I can strum a guitar. I can sort of see the guitar–the strings at least, but where is the clarinet?

All I can figure is the frilled white on the right side mimicks the shape of the silver keys on my instrument.

But what do I know? I’m not an artist.

Cubism, of course, is an attempt to look at an object from several different angles–and express it in a one-dimensional painting. It mimicks the shapes.

It doesn’t do anything for me except make me feel dischordant–I prefer art that soothes and makes me savor it–whether by color, shape, topic or technique.

Cubism confounds and irritates me–probably because it’s so often composed of sharp angles.

We didn’t spent a lot of time in the modern art section of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, but I did get one last photo before we left:

I call it “Orange.” You note the shading of the left to right as the color darkens. What do you think the artist was thinking as she created this?

I can tell you her reaction.

“Oops.”

I took the picture with my I-touch when I caught my finger over the camera lens by mistake.

I think it’s the corner of a dress . . .

I’m not a total plebian. I like many bona fide works of art. I just don’t enjoy modern art.

What about you? Which one of these do you like the best and why?

Or why not?

Art like this has got to be created for somebody . . .

September 3, 2012

The Challenge of a Father in Uniform

When my boyfriend told me he was going back east to interview with Admiral Rickover about joining the nuclear Navy, I told him I would see him in five years.

When my boyfriend told me he was going back east to interview with Admiral Rickover about joining the nuclear Navy, I told him I would see him in five years.

I had a life to lead of my own and I wasn’t interested in a vagabond marriage, much less raising children in a military family.

My boyfriend heard my arguments but headed to Washington D. C. anyway where he accepted the good Admiral’s opportunity. He was sworn into the US Navy the weekend I visited Prague, Czechoslavakia, then a Communist nation.

Love triumped in the end and I married him a year later, figuring I could anything for five years since I was only 21 at the time. We could have children after he completed his tour.

He stayed in the Navy 21 years.

We moved twelve times.

All my children were born in military hospitals.

The first six years of my oldest son’s life was spent with a father coming and going. When he was home he usually was tired. I mowed the lawn for five straight years.

More than anything, I wanted my husband to survive his seagoing days knowing his children well and not losing sight of who he was himself.

I think it worked.

But that meant effort on my part beyond mowing the lawn. I hauled those two older children across the Atlantic Ocean, twice meeting my husband in foreign parts. Not a bad gig, traveling to England and Italy, but I always had small children with me.

For the kids, every outing was an adventure–where would their father turn up next? They’d fling themselves around his knees and hug with joy. They were full of words, stories, and things to show him. “Going to the boat” to join him for dinner on the submarine when he had weekend duty, was a thrill.

I’d stand back to watch, usually with tears in my eyes.

In those early years, I interviewed teenage military children about their relationships with their fathers–what did their mothers do to help them along? What could I do for my kids?

One of our babysitters told us he opened an envelope from his father once that held, besides the letter, toe nail clippings. He laughed. “Weird though that was, it mean our father was alive somewhere and his toe nails were growing. I appreciated getting them.”

Okay.

Another friend told me she took the last tee-shirt her husband wore before he left and spread it on the baby’s crib sheet. “I wanted the baby to ‘imprint’ her father’s scent. This seemed to work.”

We didn’t do any of those things.

But one night before deployment, I put together a photo album with a story that I called “Daddy’s Book.” I thought my toddler might need reassurance. He was so young, what did it mean he wouldn’t see his father for three months?

The book featured pictures of my husband doing his ship leisure-time activities: playing cards, talking on the phone, eating dinner, praying, looking at photos of us. (I didn’t have, nor could I have used, photos of the submarine reactor compartment where he actually worked).

I had pictures to illustrate and some vague sketches.

My husband read the story into a tape recorder that night and the next morning took off for places unknown.

My son turned the pages and listened to that tape every single day his father was gone, sometimes more than once a day.

His father’s voice became the backdrop of our day. “Daddy’s Book,” was his favorite.

When we finally marked off all the squares on the calendar and Daddy returned, the first thing our little boy did was fling the book at him and ask him to read.

Daddy happily read the book aloud with his little boy cuddled close. When he finished, he looked at me and said, “that’s a great story. I’ve never seen it before.”

Daddy happily read the book aloud with his little boy cuddled close. When he finished, he looked at me and said, “that’s a great story. I’ve never seen it before.”

I laughed. “You’ve read that book countless times.”

He raised his eyebrows and I realized the truth. He’d read that book once. His son and I had listened to it countless times.

The interaction of children and their military fathers still moves me. I don’t know if it’s the memory of all those months Daddy’s chair was empty, or a recognition of how much children long for their fathers.

Even now, my eyes tear up when I see children playing with their fathers without supervising mothers.

I remember, oh so well, the challenges of life with a military father.

If you’re in a family with a dad often away from home, how do you make him real to your children? How do you facilitate the bond between them and ensure they know each other individually and not through you?

August 30, 2012

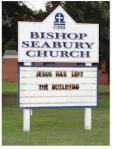

Back to Bishop Seabury: in Tears as Usual?

We’ve been in and out of Groton, Connecticut a handful of times since we moved away in 1986. Every visit, though, has been timed around Sunday morning because I wanted to go “home” to the church that succoured me, taught me, and encouraged me through some of the more difficult times of my life.

We’ve been in and out of Groton, Connecticut a handful of times since we moved away in 1986. Every visit, though, has been timed around Sunday morning because I wanted to go “home” to the church that succoured me, taught me, and encouraged me through some of the more difficult times of my life.

Since leaving Bishop Seabury Episcopal Church to move west, I’d dreamt about worshipping there again. In those dreams, I’m always perplexed as I try to explain why I go to a different church now. Eventually I remember I live on the other side of the country and thus can’t make it.

What a relief I don’t have to feel guilty.

All the same, my heart sings when they say to me, “let’s go to the house of the Lord” in Groton. I can hardly wait to see Bishop Seabury’s congregation once more.

But even when sitting in the pews, I don’t always see the other worshippers. Something about being with that body of Christ, the joy of being there, overwhelms me and I usually spend the entire service in tears.

I’m so happy to be back, I can’t control myself.

Such behavior makes no sense. I haven’t been a member in 26 years–since before the birth of my third child. Most of my military friends have moved; I recognize few people.

And yet, that church body was so important to me. I grew up, both as a person and as a Christian, during my six years there.

God puts the lonely in families and those early years of motherhood when I was a Navy wife left behind on patrol after patrol, I spent a lot of time feeling alone.

The church body reached out to me; took me in on a forsaken Thanksgiving, saved me more than once from housing disasters and loved my toddlers on days I could barely stand them anymore.

They grew my faith in countless challenging sermons, a weekly women’s Bible study, and in friendship outside of the building. They’re among my heroes–people who got me through wild times in one spiritual whole.

Thanks be to God.

The foundation was a firm faith based in prayer and relationship–to each other and to the real high priest of that church: Jesus.

The church body set an example to me of grace under pressure when the Episcopal Diocese strayed from solid Biblical truth. The church body remained in the diocese for one reason: to pray.

Things came to a head several years ago and their prayer ministry folded. They removed themselves from the Episcopal Church and became Bishop Seabury Anglican Church.

Three weeks ago by order of the Connecticut courts, they gave up their church to the Episcopal Diocese and now meet in the ball room of a Groton hotel.

It will be interesting to see if I sob my way through a service in a different location.

But the right Reverend Ronald Gauss said it best on August 5 when services were held for the last time in the church built debt-free by the sacrifices of the parishioners. “The church is the people, not the building.”

Thanks be to God.

August 27, 2012

Revising My History–Why Ever Not?

We had traveled all the way across the country in a Volkswagen bus, visiting friends, relatives and historical sites from Los Angeles to Maine. My favorite spot required a weekend visit because I longed to spend time revisiting our older boys’ birthplace: Groton, Connecticut.

We had traveled all the way across the country in a Volkswagen bus, visiting friends, relatives and historical sites from Los Angeles to Maine. My favorite spot required a weekend visit because I longed to spend time revisiting our older boys’ birthplace: Groton, Connecticut.

My life in those years revolved around our home on a granite ledge beside the US Naval submarine base, the submarine community itself, Bishop Seabury Episcopal Church and the Groton Public Library. I had a whole circuit I drove regularly with our two older boys in tow.

To get the full effect on our way to church that Sunday morning in 1997, we started from the Navy lodge and went past where we once lived.

To get the full effect on our way to church that Sunday morning in 1997, we started from the Navy lodge and went past where we once lived.

Our house was purchased by the Navy base and torn down years before, so it was just the location we paused to admire from the side of the road.

We peered up at the folliage and saw the line of Christmas trees. They were planted by our predecessors high on a granite ledge above Route 12, but one year we’d cut down our tree from our very own yard.

Only my husband and I remembered that Christmas.

The older two children, fourteen and sixteen that year, shook their heads. The younger two were born on the west coast. Our pilgrimage was pre-history to them.

I directed my husband to continue down Route 12, past the mini-mart where I always stopped to buy The New York Times on Sunday mornings (doing the crossword puzzle is still a weekly routine). I directed him to turn left on Gunjywamp Road, through Navy housing, and then the questions began.

I directed my husband to continue down Route 12, past the mini-mart where I always stopped to buy The New York Times on Sunday mornings (doing the crossword puzzle is still a weekly routine). I directed him to turn left on Gunjywamp Road, through Navy housing, and then the questions began.

“How did you know to turn on this road?” one child asked.

“This was the way to church, don’t you remember?” I said.

No.

“There’s Shepherd of the Sea Chapel, we’d visit there from time to time. Remember? How about the Navy Exchange mini-mart?”

No.

“Do you remember the rock walls that run along the north side of the road? Your godparents lived just up this street, J. You played at their house all the time, C. Remember?”

No.

“Is that where they lived?” My husband slowed the car. “I thought we lived closer to them.”

The children stared out the window at the oak trees and stone walls, new scenery to them.

The blood sang in my veins with a joy Icould scarcely contain. Here’s where I rescued the woman with the shopping cart and three children, there’s where we held Bible study. My friend Penny and I homeschooled our preschoolers at that house. The boys rode a snow saucer down the nearby hill.

I could scarcely sit still as the memories flooded with a vibrancy that made me feel years younger. Where had the time gone?

“I’m really sorry, Michelle,” my husband finally said. “But I didn’t really live here those six years. This was where you and the boys lived; I just visited from time to time.”

I stared at him, incredulous. “You don’t remember?”

“Here’s the Gold Star Highway. Which way do I turn?”

My heart sank. “Left. Turn right at the light.”

How could they not remember any of this?

I gazed back at the traitor children, now so grown and forward thinking. C did not remember the first six years of his life?

I was a pregnant twenty-four year-old when we moved to Groton, Connecticut; a pregnant thirty year-old when we left. Most of my twenties were spent in New England relishing the climate, the food, the life.

I was a pregnant twenty-four year-old when we moved to Groton, Connecticut; a pregnant thirty year-old when we left. Most of my twenties were spent in New England relishing the climate, the food, the life.

And no one in the car recalled anything about that time. Well, maybe my husband in his blurry-eyed exhaustion from submarine duty.

Did anyone I loved remember me in the prime of my life?

If they didn’t, was that time wasted?

I decided it was time to do a little revisionist history. After all, who could contradict me?

“Those were such good days,” I began, pointing to the turns as my husband drove. “Dinner was always complete with a protein, vegetables and salad. We always ate on time. Laundry was a breeze and always folded neatly and put away. I read to you children for countless hours [true], and we played all the time. You never cried, I was never cross, my figure was perfect and I always smiled.”

Really?

Hey, if I’m the only one with the memory, I’m going to make it a happy one for me!

Later in that trip we spent time with folks who had vivid stories to tell about how wonderful and beautiful I was during our Groton years.

My husband agreed with them. I’m not so sure about the children . . .

August 23, 2012

Thoughts on Slavery–and Inherited Privilege

When I wasn’t sleeping last night, I finished reading a very interesting book by Thomas Norman DeWolf called Inheriting the Trade: A Northern Family Confronts Its Legacy as the Largest Slave-Trading Dynasty in U.S. History.

When I wasn’t sleeping last night, I finished reading a very interesting book by Thomas Norman DeWolf called Inheriting the Trade: A Northern Family Confronts Its Legacy as the Largest Slave-Trading Dynasty in U.S. History.

As a descendent of 200 years worth of slave owners, I’ve been uneasy with the whole subject of slavery ever since I unearthed the fact during my genealogy research 17 years ago.

I discussed this subject on a blog I wrote last winter. You can read it here.

In DeWolf’s book, he and nine distant cousins traveled the triangle trade route their slaving ancestors exploited to such wealthy ends as late as 140 years ago. Their quest was to examine their possible responsibility for the racism and sorrow that continue to plague our nation because of slavery.

I caught a glimpse of understanding as DeWolf and his cousins struggled to come to terms with their family’s past. Arguging about racism, sexism and the effect of privilege got tedious until DeWolf finally recognized how he personally had benefited just by being a white male.

Bear with me.

I, personally, have a lot of problems, angst, dealing with people who do not respect me for whatever reason.

Think what it would be like to live in a society which automatically assumed you were not worthy of respect just because of the color of your skin.

Some of you may be dealing with that because of your size, your accent, your education, your sexuality, or your church-going habits.

It doesn’t feel good to always be on the defensive about things you may or not be able to control.

What would it be like to grow up in a society where your basic quality is excluded from the marketplace?

How isolated would you feel? How defensive? Think about the things that make your hackles rise. How would you like to have to confront folks who judge you for that every time you walk out your door or turn on your television?

Don’t you think you might have a slight chip on your shoulder as a result?

That’s what DeWolf finally caught about the African-Americans with whom he interacted. He did not know many races in his Oregon community, but he finally began to see that what he assumed, usually unconsciously, about those of a different color probably wasn’t true.

Of course it also works the other way. How would you like to have your abilities, motives, and ethics continually judged, consciously or not, by the greater society in which you lived?

In The Autobiography of Malcom X Alex Haley makes the point that the black family unit has been damaged by what Madison Avenue presents as beauty: a small-framed, blond, blue-eyed, high cheekboned woman with a narrow nose. Or, the antithesis of most African-American women (and many other American women–I don’t look like that either).

When that is held up as beauty and a Black man looks at a Black women, he doesn’t necessarily see beauty. (To his credit) he has to look past what a woman looks like to who she is. Unfortunately, according to Haley writing in the 1960’s, this had a very negative result within the Black community.

When that is held up as beauty and a Black man looks at a Black women, he doesn’t necessarily see beauty. (To his credit) he has to look past what a woman looks like to who she is. Unfortunately, according to Haley writing in the 1960’s, this had a very negative result within the Black community.

We lived in Hawai’i for four years. It’s not like being an African-American in a predominately white society, but it gave us a taste for being judged to the negative by our appearance.

I couldn’t buy clothing in the islands–I’m the wrong everything. The blond blue-eyed neighbor boy was beaten up in school and sent to the ER with a concussion in second grade by classmates who didn’t like what he looked like or how he behaved.

My oldest son was afraid to go to his first high school dance–because he was too tall and none of the pretty petite girls would want to dance with him.

Who would have guessed?

DeWolf struggled with bitterness against the institutional church which condoned and abetted slavery out of his family’s home port of Bristol, RI. He told of walking into the dungeon area of the fort in Ghana where slaves were held before being sent out to his family’s ships. When he looked up before going down, he saw the spire of the church.

No wonder, he concluded, Christianity is such a mess. “They” were complicit in enslaving millions of people.

During the Revolutionary War, 83 of 104 Episcopal priests in Connecticut owned slaves. Thomas Jefferson, of course, is the epitome of hypocrites in this arena.

Reconciliation, social justice, and really examining racism in our country, looks different to me now. I’m still mulling this over, but DeWolf has opened a window and helped me catch a glimpse of the underlying sorrow and unintentioned callousness to a deep injustice.

I’m grateful for that.

I’m also annoyed he did not examine the blood letting expiation of the Civil War, and thus will now write him an e-mail.

But as you go about your day, give a thought to how you may unconsciously be accepting the privilege of your circumstances at the emotional expense of someone else.

Are we not to love one another as Jesus loved us?

August 20, 2012

Crafting a Life Story for a Selected Audience

Once I graduated from college and left Los Angeles, I never lived closer than 350 miles to my parents. My father used to gaze through his telescope at Long Beach Naval Shipyard and wonder why his son-in-law couldn’t get a job there.

Once I graduated from college and left Los Angeles, I never lived closer than 350 miles to my parents. My father used to gaze through his telescope at Long Beach Naval Shipyard and wonder why his son-in-law couldn’t get a job there.

The Long Beach shipyard did not work on submarines and my father knew that, but still, it was galling to watch the Navy ships sail in and out and know his daughter and grandchildren had to live far, far away.

We didn’t have a lot of extra money and in those days telephone calls were expensive. My mother eventually figured out the reason I seldom called had to do with finances, not disinterest, and so she called me. Every Sunday afternoon or evening depending on our particular coast at the time. One of us was either making the traditional Sunday spaghetti dinner or cleaning up.

I loved the freedom of talking to my mother because she wanted to know everything–particularly every detail about her grandchildren. I could brag to her of their brilliance and she would egg me on. I could ask for child rearing advice because I knew she had their best interests at heart. I could tell of my disappointments or discouragements because I knew she would not hold it against me or those grandchildren.

We talked over the phone in ways we seldom did face-to-face. My mother became my friend when I finally grew up enough to recognize I didn’t know it all.

Those phone calls were lifelines in the early years when my husband routinely spent months at sea and I lived with two small children on a granite slab without any neighbors. I could tell my mother about my fears, how I wanted to raise my children, and the ways I cut pennies to the bone to stay home with them.

She understood our life very well and often would send “care packages” of fun for the boys and me. We all were thrilled when the UPS man arrived with a surprise package.

I miss those boxes full of silly fun.

Knowing I’d have an engaged audience on Sunday afternoons, changed the way I saw my day-to-day life. Each event became a series of scenes in the greater play of existence.

“Boy,” I’d think when something noticeable occured, “Mom’s going to love this story when I tell her.”

If the unusual occured early enough in the week, say on Monday or Tuesday, I’d rehearse the tale all week long. I learned a lot about timing and pacing by figuring out how to present my little melodramas in the most interesting ways.

I needed to keep my select audience amused.

My mom’s sense of humor was not as advanced or honed as my husband’s, so if my mother laughed, I knew my husband would guffaw.

I’d write letters to him on Sunday nights.

I had to craft my personal stories, however, because there were corners of my life my parents didn’t want to know about. They didn’t really approve of my church-going enthusiasm and did not want to hear about spiritual experiences. Since my days were wrapped up in small children and most of my friends were from church or Bible study, censorship intervened. I had to plot out what I would say and how–to keep her interest but also to slip in what was truly most important to me after my children and sea-going husband.

Curious how the need to watch 60 Minutes would interrupt those particular tales of derring do. “Look at the time,” she’d say, and I knew I’d stretched my chance too far.

One day my mother died unexpectedly and much too soon.

Sunday afternoons rang empty.

No more surprise boxes came.

I’d lost my audience.

That first year after her death I often caught myself on Sunday afternoons puzzled Mom hadn’t called. I always had my stories ready.

the cadence and rhythm that forms the crafting of tales is imbedded into my daily life by so many years in the telling. I still see the events of my daily life within the context of plots and minor subplots, characters and dialogue. Timing and pacing are important, and so is tailoring the telling to fit the ears of the listener.

Unfortunately, I’ve had to find a different audience.

For whom do you craft the story of your life? When you mentally replay your daily events, whose face or voice are you presenting them to?

Does it make a difference?

August 16, 2012

The Agony of the Navy Ball–Sometimes

As the chief engineer on the oldest submarine in the Atlantic Ocean, my husband had a number of duties I never understood.

As the chief engineer on the oldest submarine in the Atlantic Ocean, my husband had a number of duties I never understood.

As the youngest Lieutenant Commander in the Navy for a couple months in the early 1980s, he had gentlemanly responsibilities that didn’t always make sense–to him.

For example, the Navy ball.

He’s never been a big dancer, but attendance, particularly at the Submarine Birthday Ball, was mandatory. He wore his fancy uniform with the gold cumberbund and bow tie and escorted me–several years.

We probably danced once, for form’s sake, and left it at that.

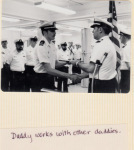

He sure looked terrific in his uniform, however. (And no, that’s not him in the photo above).

One year we bought our tickets to the ball early in the season. The boat wives chatted about our dresses and wondered if our nuclear engineers would dance that year. We had decided to go en masse and enjoy ourselves, no matter what our brilliant (truly!) husbands said or did.

The second Saturday in December would be a sparkling Christmas-type ball and our last wardroom get-together of the year. We were excited.

The week before the ball, however, the submarine unexpectedly deployed with their return date “unspecified,” but most likely in the new year.

Secrecy is like that–you never know and you’re seldom told.

Afterall, loose lips sink ships. (Though that wasn’t a big deal since our boat was a submarine.)

For reasons I can’t remember now, I was the “senior” (as in most experienced) officer’s wife on the boat at the time, and my fellow boat wives’ morale was flagging. “Let’s go without our husbands,” I declared. “We can have a good time, particularly since we already have the babysitters lined up.”

They weren’t so sure.

Several went home to their families for Christmas– an excellent idea–but five of us remained in the area the night of the ball.

I reminded them we had a “duty husband” left behind and he could escort us. That’s Steve up there in the photo with us.

We had our table. We had the sympathy of all the women whose husbands were there. We maintained our pride. We hung in there like good Navy wives and kept our upper lips stiff.

No one asked us to dance.

Most of our husband wouldn’t have danced with us anyway. Did it really matter they were on the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean and not with us?

You tell me.

Of course it did. What a miserable night.

Ten years later, living in Hawaii and looking ahead to yet another Navy Birthday Ball, my husband and his engineer peers decided that year they were going to get their money’s worth.

“We always go to these affairs in our most expensive uniforms and just stand around drinking and telling sea stories,” one of the men complained. “We pay the band, but never dance. Let’s do something different this year.”

I’m so proud of them. On their own initiative, they hired a dance instructor to teach them how to dance and actually spin their wives and girlfriends around the dance floor.

My Navy wife friends were shocked–but delighted. It was almost, dare we say it, romantic?

Maybe you could teach some old engineers new tricks?

We had to take classes and practice. Every Saturday night for five weeks we met at the Navy housing community center with a polished man, a chiffon-draped female partner, and his CD player.

He walked us through the steps, they demonstrated, we laughed and stumbled. Fun evenings.

But some of our dancers had trouble and the instructor got vexed the fourth lesson. “I don’t understand what your problem is. It’s simple, move with the beat, a one and a two and a three and a four. How hard can this be?”

“Math!” One of the engineers shouted. “We can do math!”

The men grabbed us and applied themselves to what they really knew: counting. We were off.

Unfortunately, not everyone practiced between the lessons and the ball, which was held on a tourist ship cruising Waikiki Beach. By the time the band started playing, most of our moves had evaporated from our brains. Certainly we tried, and far more people were on the dance floor that year.

Some were mumbling, “a one and a two.” One ingenious couple had everything written out on 3×5 cards. (Several asked to borrow the cards). A half dozen naval engineers stood on the sidelines discussing the hydraulics and potential engineering problems on the cruise ship.

My guy and I?

We shuffled through the steps we could remember, laughed, and shook our heads.

But at least that year, the ball wasn’t an agony and all the men were home.

Having them home. The best part of all.

Do you know how to dance?

Would you teach us?

August 13, 2012

The Care of Navy Wives in Life and Death

We visited Arlington National Cemetery fifteen years ago, riding a short bus tour through the prestigious spot overlooking Washington D. C.

We visited Arlington National Cemetery fifteen years ago, riding a short bus tour through the prestigious spot overlooking Washington D. C.

We saw the moving tribute to the tomb of the Unknown Soldier, thought about the slap to Confederate General Robert E. Lee–the property belonged to him prior to the War of the Northern Agression. To retaliate for his defection from the Union Army to the Southern, the federal government took over his property and eventually made it into a national cemetery.

Like all military cemeteries, walking among the white tombstones is a sobering affair and as you gaze across the hillsides watching them climb, the magnitude of men and women who have fought and died for our country can feel overwhelming.

I didn’t know anyone buried in the cemetery until we came to a select circle of individuals who had made their mark on American society and the bus discharged us for a few moments.

And there I saw the grave of a man whom my husband had met and who had played a strategic role in my personal life: Admiral Hyman Rickover.

We saluted, of course, and then I walked around to the other side and caught my breath. On the back of Admiral Rickover’s tombstone were two other names: that of his first wife, Ruth, with her life dates and that of his second, Eleonore.

As far as I’ve been able to discern, Eleonore Rickover is still alive and I’m glad to hear it, because she has long been a heroine in a story told to me many years ago.

My friend Gina Plummer was the CO’s wife on a submarine in the 1980′s when one of “her” boat wives came down with cancer. I don’t know where the boat was at the time, probably out to sea (they usually were when crisis hit). This young enlisted wife’s prognosis was challenging and that particular year, they sent her to be treated at Bethesda Military Hospital outside of Washington, D. C.

She knew no one in the area. She was facing cancer surgery and recovery alone and far from home.

Gina called the one person in the area she knew would help, former Navy nurse and wife of the highest ranking nuke: Eleonore Rickover.

Gina explained about the young woman and asked Eleonore (I may call her that, right, since she was the friend of a friend and another Navy wife?) if she could arrange for someone to check on this woman.

Eleonore said of course.

The sailor’s wife came through beautifully, visited every day by a charming woman who cheered her and encouraged her. When the patient was well enough to return home, she asked her helpful visitor, Eleonore, for her address.

Mrs. Rickover had visited and overseen the young woman her entire stay.

My eyes fill with tears as I type because that’s the way of Navy wives. We go out of our way to help each other–even if the relationship is neglible at best.

Thanks for your example of grace, Eleonore.

The Navy takes care of its own, and so do its wives.

Even in death.

Standing in Arlington National Cemetery staring at Admiral Rickover’s tombstone was the first time I realized that as a military wife, I, too, could be buried in a national cemetery. It’s a humbling thought.

I, obviously, haven’t given my life for my country, but I’ve spent a lot of time with men and women willing to do so. For 20 years, I made sure my husband could go to war if necessary, without worrying about his family.

I’m just glad it never came to that.

Thinking about Arlington National Cemetery and visiting Admiral Rickover’s grave, is particularly poignant to me today. “One of my own,” a boat wife from those long ago days on the USS Skipjack, will be buried there soon.

Rest in Peace, Patty.

Thank you.