Michelle Ule's Blog, page 101

October 23, 2012

Seeds to be sown

My children were fascinated by dinosaurs and we spent many hours reading about them, seeing them “without the skin on” at museums, and practicing those elaborate names.

My children were fascinated by dinosaurs and we spent many hours reading about them, seeing them “without the skin on” at museums, and practicing those elaborate names.

Like many people, they wanted to know what happened to them? Why did God make dinosaurs if their only role was to die long before people could interact with them?

Over at Reasons to Believe, Astrophysicist/apologist Hugh Ross points out the death of all those dinosaurs oh so many millenium ago, is the reason we have oil on the planet today. If God had not created those dinosaurs to live and die when they did, we wouldn’t be driving petroleum-based engine cars nor have all those advantages of plastic.

God looked ahead to your needs and mine. Before men and women ever walked the earth, God prepared the planet for us.

I thought about God’s provision this week when seeds of a surprising conversation sown years ago came to fruition. I recognized a truth about my life I hadn’t seen before.

I’ve told the story before of the challenges I faced when my husband was the chief engineer of the oldest submarine in the Atlantic Ocean. You can read about that angst here.

When my husband first attended submarine school we were warned, “the best way to prepare to be a good Navy wife is to learn how to become a widow.” The admiral advising us twenty-somethings had been the Casualty Assistance and Calls Officer (CACO) when the USS Thresher broke apart and the crew drowned. The horror of women unprepared to care for their families never left him.

That’s one of the reasons military wives tend to be independent women who can take care of themselves. We have to.

So, we balance the check books, mow the lawn, and fill the car with gas. I’m sure many of you do the same.

These tasks were easy for me because my “love language” (see Gary Chapman’s excellent The Five Love Languages) is acts of service. That’s how I show people I love them, by serving them and trying to meet their–even unexpressed–needs.

Shortly after my husband retired, however, I found myself in a Bible study with a group of lovely civilian women–none of whom ever filled their cars with gas.

A minor thing, but it astounded me. All those husbands who went to the gas station, “just because.”

Amazing.

My Navy wife friends howled when I told them of this element in “the real world.”

I didn’t think about it again until the other day when a newly-married friend marveled her groom voluntarily filled her car with gas. I laughed and told the story of those Bible study women long ago, but sudenly found myself weeping.

“Why, Lord?” I asked.

Immediately, a flash of Connecticut.

I saw, suddenly, what I had lacked all those years ago.

We often can discover our love language–the need we have to see love expressed to us–by how we express it to others.

Acts of service, for me.

All those years ago, no one was available to serve me–not in a monumental way, but in the small things: mowing the lawn, fixing broken appliances, filling the car with gas.

I did all that and more, but without any neighbors and with a husband gone 85% one year, only the little boys saw my life and they, well, were little boys needing serving themselves.

By the time my life in Connecticut ended, my “love tank,” –my sense of being loved– was empty.

It had nothing to do with my husband’s love for me–that was never in question–but by the intangible way I felt loved (or not).

There was no one to serve me in the minor ways my soul craved.

When you determine your love language (acts of service, touch, gift giving, words of affirmation and quality time), ask if your “tank” is regularly being filled by the people in your life.

If not, how are you behaving to get that need met?

If you’re alone, how can you interact with people to get some of those needs responsibly “tanked up?”

That’s part of the secret of a close group of military wives. Anne bailed me out of the hospital. I babysat so MaryLynn could coach a woman through childbirth. Jan brought me eggs during a snow storm. Countless people prayed for me. Recognize those acts of service?

I love those women and feel close to them even today.

Because of the seeds sown in that Bible study all those years ago, watered by a friend’s question about love languages last week, and the sharing of a charmed newlywed, I finally can understand the ache of those Connecticut years.

Just like God used dinosaurs to prepare a more comfortable life for us, he used sharing in a Bible study years ago to prepare my heart to understand a piece of my past.

I’m thankful.

What’s your love language? How is it best filled?

October 18, 2012

The Wrong Type of Book for Difficult Times (at least for me)

Photo by Sarah Browning/Flickr

I wrote a blog post earlier this week for Books & Such Literary Agency discussing the momentous books I read during momentous times. I listed off the mostly non-fiction stories that kept me occupied through the births of my children, my honeymoon and other significant moments. You can read the post here.

I’ve written before about “comfort novels,” books read when I didn’t want to belabor my brain too hard or when I needed a fast escape I could trust. That post is here.

Interestingly, I cannot recall what I was reading when my parents, grandparents, and in-laws died. I draw a blank in the library department at every death in my family.

I’m thinking of this now because eight friends have lost family members since June. I’ve spent a lot of time contemplating death, weeping with those who weep, and remembering good times with people no longer walking the earth.

Something about death–the ending of life–puts more minor experiences into perspective and, I think, makes it harder to appreciate “art” that exacerbates the wound rather than tries to heal.

And that includes books.

Last night I picked up a current best-selling book, Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn.

I hated this book. I can see how clever it is. I recognize the writing craft. I can admire how Flynn put the book together, but I’m not going to finish it.

After 125 pages, I gave up and read the ending. I don’t need to spend anymore time with it.

But why?

I’ve been a lay counselor most of my adult life. I’ve heard and continue to hear, many tragic stories. I volunteer with an organization that helps people in crisis. I want to save, I don’t want to destroy. The books I write have difficult things in them, but they’re full of hope by the end. I can’t live my life any other way.

Gone Girl is a mystery, a clever one, but its hero and heroine are vicious, nasty people who drink too much, swear too much, and waste their lives. It’s painful for me to read, particularly during a time when so many people I care about are suffering from the loss of a much loved spouse.

The counselor me kept shoving aside the reader me. I couldn’t get past, “can this marriage be saved?” to pay attention to what was happening to the plot. After awhile, I realized that if they didn’t want to change and have a happier life, there was no point in me continuing. So I read the ending and shut the book.

The ubiquitous “they” say you can tell a sophisticated wine drinker from a novice by the color of wine. I prefer white wine, which the wine afficionados explain makes me a novice or juvenile drinker because I need a sweeter drink.

Okay.

Maybe I’m just a novice reader, then, preferring at least some ray of hope by the end of the story. If not, what is the point of reading it? I’ve got enough real life drama going on around about me, I don’t need to spend my time with fiction characters who prefer to wallow in pain rather than change their lives.

That sounds a little snippy from someone writing a Civil War novel full of tragedy. But in my novel people are dealing with a war thrust upon them, trying to find ways to survive with a modicum of happiness. They’re not using their grim circumstances to take pot shots at the people they allegedly love.

I’m interested in how people deal with difficult times–how they find the strength of character to get through events beyond their control and come out with some degree of peace.

Perhaps I feel that way because that’s the way I live my own life.

What about you? What types of books do you like to read when life is very hard?

October 16, 2012

Maybe I Can’t Go Home Again?

Someone once said about life, “the happiest times are when your children are young.”

I had young children for a long time–30 years–so mine has been a happy life, but I like to revisit happy places and one of them was Monterey, California.

When my husband finished a three and a half year tour on the oldest submarine in the Atlantic Ocean,we moved west to Naval Postgradute School for him to earn his master’s degree.

Everyone agrees, PG School is one of the best billets in the Navy.

Thank you, American taxpayers.

Military folks were home and merely going to school. That meant dinner could be eaten with both parents, you could plan vacations, and even expect the dads to be there for the birth of their children.

We joked about ‘the requisite La Mesa baby;” seemingly every family gave birth while living in La Mesa housing.

Including us.

Living in simple units on a flat hill–a mesa–above Monterey’s fog belt, we savored full time family life. Teachers from the community vied to teach at La Mesa School–the children were respectful, had two devoted parents and the non-military parents volunteered constantly.

I’d never lived in such an organized community, before.

All the kids played soccer because dads were home to coach. La Mesa boasted the largest cub scout troop in California. It took all day to run the Pinewood Derby on six tracks–with one reserved for parents to keep actual competition limited to the boys.

(The airdale parents would take their son’s wooden cars into the wind tunnel to check for aerodynamics. That was simply unfair . . . )

But last week as I drove up the hill–the one my husband faithfully rode his bike up every day coming home–I saw LaMesa has changed. Instead of the “” houses the Navy built everywhere, large modern homes often two stories high, dotted the lots.

I recognized the street names–I’d walked those blocks religiously during our years there–but the neighborhood did not look the same.

I got so disoriented, I stopped my car and when a La Mesa mom approached–pushing the requisite baby in a stroller and walking her dog–I got out and asked if I could stroll with her.

“I used to live here,” I explained. “And I’d like to know how La Mesa has changed. I can show you my ID card . . . “

She explained about new homes, the busy child care center, and the happiness of having dad around. She was delivering a surprise Halloween treat to a neighbor, “see, we still have traditions here.”

Military life now includes e-mail, Skype, and cell phones with international coverage. Those are positives and I’m thankful.

But it still has long deployments, combat situations and lonely family members left behind. Children still want to touch their parents.

When we came to my old address, I felt a stab. My modern friend explained the military is taking pains to make housing more like what families could get on “the outside,” now.

To do that, though, means tearing down the old and building the new.

They didn’t start with our house, but it’s gone.

The air is the same, as are the pines ringing the housing area. Streets bear familiar names and the baseball diamond hasn’t changed at all. The mini-mart has a neon light but the trees have been trimmed. You can still hear the barking sea lions from down at the Monterey wharf.

The modern wife ruffled her toddler’s hair as we stopped in front of her very nice duplex. “It’s a great place to live and we’re happy.”

Even if I couldn’t go home again, I was glad to hear it.

October 12, 2012

A Life in Chapters

Perhaps it would have been different if I’d married, moved to a new home and stayed there. Instead, we wed in southern California and then drove across the country to Orlando, Florida. Six months later, a burly crew packed up our household goods and shipped them to Ballston Spa, New York where we were introduced to seasons for the first time.

Perhaps it would have been different if I’d married, moved to a new home and stayed there. Instead, we wed in southern California and then drove across the country to Orlando, Florida. Six months later, a burly crew packed up our household goods and shipped them to Ballston Spa, New York where we were introduced to seasons for the first time.

Before the dust could even settle, 90% of our possessions went into storage and we camped in a chilly summer cottage on the bank of the Niantic River. I saw it snow for the first time in Connecticut. Four months later we encountered snow drifts piled six feet high when we drove through Chicago on our way west.

My husband gave me an ultimatum at Mare Island: a baby or a cat. I took the feline and fifteen months later had to figure out how to move her and a pregnant me across country in a non-air conditioned car in July.

This time we stayed six years in Groton, Connecticut, where we also picked up a couple boys.

Pregnant again, I stuffed the same cat into her cage, surrounded the children with books and small toys, and drove back across the country. This time my husband joined us, skidding in from South American three days before departure.

In Monterey, California we welcomed a third son and for thirty months, savored both a father in the house full-time and grandparents in the same time zone. From there we went to Silverdale, Washington where God, in his wisdom, suggested a little girl to shake up the household.

She was a year old when we got our final set of orders: Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. We foolishly adopted a feral cat there and four years later retired to Ukiah, California which is about as far removed as you can get from Honolulu cultural.

We inherited a dog in Ukiah.

Four years after that, we picked up yet again and moved to our present location, also in northern California but not quite so rural. The thirteenth move, apparently, was the lucky one. We’ve been here eleven years.

And therein lies the problem.

Up until this house, I could mentally keep track of time by where we lived. The children’s growth is measured not on a permanent door post, but in memories of a specific culture and the activities. Apple picking met Connecticut in the fall, rainy days were Seattle, paintball and poison oak hallmarked Ukiah. The Alaska vacation came during the rugged Pacific Northwest years; European hunts for dad were flips across the Atlantic out of New England. I-5 meant Monterey up until the California permance–and now all those trips stun into one.

Volcanos and beaches and the scent of frangipani mark the boys growing four inches in one year and me not noticing because the shorts didn’t need hemming. Fresh corn, thirty minutes off the stalk, was Ballston Spa and Florida, well, we didn’t go outside much the first six months we were married.

When I look through the photo albums, I recognize the baby by the background: the furniture, the scenery, the house. Memories fit neatly into chapters of time, divided into scenes with dialogue touched by the local vocabulary, eh? The titles are the cities where we lived and while each could be an entire volume of its own, they fall under the umbrella, the story, of our life.

2001 to the present, however, is a lovely blur of consistency and now I need an index.

My dad died in 2002, but what year did my third son graduate from high school? We bought our car three days after the second son got married, but what year was that? When did we return to Alaska? What made us travel to Virginia whatever year we went? Can anyone remember when the first dog died and we got the second? By the way, how old is Suzie?

Recognizing our rhythm and laughing that since God was used to us moving every four years, we tried to fool him into thinking we had moved by remodeling parts of the house. I’m pretty sure we altered the kitchen in 2005, but what year did we refresh the bathroom?

It doesn’t matter, God got the joke and we’re still here, confounded on how to move again if the Navy isn’t behind it.

Life isn’t divided so neatly anymore and since I can’t peg routine life events on location, my brain spins trying to make a connection.

Help me.

It comes down to this genuine question: how do normal people keep track of time, or at least their family’s history, when the scenery doesn’t change much?

October 8, 2012

Fortunata’s Year of Weddings

My Sicilian grandmother Fortunata (“good fortune”) lived on an isolated farm in southern California and every outing was an event. Naturally, she was interested in her grandchildren, particularly those four granddaughters. Born in 1901, Grammy wanted her girls to find good men and settle down.

My Sicilian grandmother Fortunata (“good fortune”) lived on an isolated farm in southern California and every outing was an event. Naturally, she was interested in her grandchildren, particularly those four granddaughters. Born in 1901, Grammy wanted her girls to find good men and settle down.

My three female cousins had no trouble attracting members of the opposite sex and they charmed my grandmother with their traits. Barbara was a perky girl with curly dark hair and a delightful smile. Joan was more matter-of-fact and precise, a baton twirler in a dazzling costume who also mastered the handcrafts my grandmother loved. Robin was the charming baby of the quartet who lived not far away and adored Grammy’s cooking.

And then there was me, number three.

Tall, gawky, horn-rimmed glasses on my nose and braces on my teeth, I towered above her. I could sew, but a crochet hook was beyond my ability. I prefered books, history and dreaming. She smiled politely and wrung her hands about the non-existant swains.

“Don’t worry about me, Grammy.” I finally said. “I’ll be the last one married and I’m perfectly happy about that.”

She shook her head and crocheted me a tablecloth, anyway.

You can imagine the shock, however, the Thanksgiving of my senior year in college when I announced my engagement. My cousins were not married; what was I doing stealing all the nuptial thunder?

Grammy was thrilled.

My mother had ingrained in me at a young age that I could not get married until I graduated from college. I actually thought it was a law in California until I entered high school and started meeting non-college-graduate married couples. For that reason, we planned our wedding for the following October after my graduation and my finacee’s commissioning as a naval officer.

Shortly after Christmas, Barbara went to Las Vegas and got married. The family celebrated and Grammy gloated: two granddaughters married in one year, what joy!

A month or so later, my Aunt Arly called Mom. “When is Michelle getting married?”

“October 8.”

“Wonderful! Robin is engaged and they’re planning their wedding for September 10!”

My chagrinned mother called with the news. “She’s getting married before you!”

“Great,” I said. “I’ll be able to go to her wedding.” We were moving to Florida right after ours.

“True,” Mom agreed. “But you don’t feel like she’s stealing your thunder?”

Thunder? Since family members no coubt considered it a miracle the bookworm had found a husband, thunder wasn’t a concern to me!

Three granddaughters getting married! God had been good to Fortunata!

And better news, Barbara was expecting a baby! How could life be any more rich?

Aunt Rosie called Mom a few weeks later. “When is Michelle getting married?”

“October 8.”

“How about Robin, do you know when she’s getting married?”

Suspicious, Mom answered slowly. “September 10, why?”

“This will be perfect. Joan is getting married September 24!”

And so it was that we spent an entire summer having showers: one baby and three wedding. Grammy’s crochet hook and knitting needles went into overdrive. The mothers and Joan discussed fabrics, receptions and where to get a good deal.

And so it was that we spent an entire summer having showers: one baby and three wedding. Grammy’s crochet hook and knitting needles went into overdrive. The mothers and Joan discussed fabrics, receptions and where to get a good deal.

Every other week for a month, we gathered to celebrate first Robin’s marriage to Rick, Joan’s to Bob, and finally mine to Robert.

When I noticed Robin wearing a pair of pantaloons at her wedding, I inquired into them. They had been Grammy’s.

You’re supposed to wear something borrowed, right? That’s Grammy and me laughing at the top.

I got the last word, though, when I kissed my Sicilian grandmother and said. “I told you I’d be the last one married.”

Happy anniversary to Robert, with a nod to Barbara, Robin and in memory of Joan, Mom, Rosie, Arly and, of course, Fortunata.

October 4, 2012

Thank You, the Massie Family of Writers

Like many people, I viewed the movie Dr. Zhivago with fascination and became an instant fan. I loved the story so much as a fourteen year old, I prefered to remain in our Volkswagen campervan reading Boris Pasternak’s book, rather than visit the palace of Versailles.

Like many people, I viewed the movie Dr. Zhivago with fascination and became an instant fan. I loved the story so much as a fourteen year old, I prefered to remain in our Volkswagen campervan reading Boris Pasternak’s book, rather than visit the palace of Versailles.

I’ve never been back to visit King Louis XIV’s palatial home outside Paris, but I’ve seen Dr. Zhivago countless times.

Fourteen is a good age to find a passion, and from Pasternak’s book, I went on a quest over the following four years reading Russian history–particularly the Romanov version. It was only a matter of time before I found, and fell in love with, Robert K. Massie’s Nicholas and Alexandra.

In the dizzy days of late adolescence when life awaits and true romance only beckons, I read about the jewels, furs, snow and the dramatically lost lives of displaced Russian royalty at every opportunity. I envied Robert K. Massie’s finding the aging memoirs of Russians counts and princesses in the New York Public Library and slitting the pages with a pen knife he carried in his briefcase.

While Massie had no patience for the possible mysterious escape of youngest Romanov daughter Anastasia, the idea fired my imagination. I wrote a prize-wining short story based on the tale my senior year of high school. (DNA testing has since proved Anastasia did not escape and the woman, Anna Anderson, who claimed to be her for so many years was, indeed, a Polish factory worker.)

During my sophomore year of college, I wrote a book review for the UCLA Daily Bruin about the memoir Journey by Robert K. and Suzanne Massie. This book told of the backstory to their original personal interest in Russian history: their son’s hemophillia.

During my sophomore year of college, I wrote a book review for the UCLA Daily Bruin about the memoir Journey by Robert K. and Suzanne Massie. This book told of the backstory to their original personal interest in Russian history: their son’s hemophillia.

Bob, the son, was my age and I read the gripping tale with fascination. I even made my mother read it because I wanted her to see the life the Massies gave their brilliant son and his sisters: a life full of interesting people, education, and four years in Paris.

Mom recognized my yearning for an educated, international life, and merely commented, “We’re not that kind of people.”

Now as I look back, I wonder if desperate parents dealing with a suffering bleeding son rang a little too close to home for her.

Inspired by the Massie family’s difficulties, I became a blood donor. I’ve given enough pints of blood over the last 38 years that I have tracks on my arms and scarred veins.

In June, 1978 I watched the Harvard graduation on PBS where Alexander Solzhenitsyn had quite a few pointed things to say. I loved hearing the muttering Russian language and certainly appreciated the Nobel Laureate’s point of view.

I continued reading in the Russian-translated canon after I became an adult–working my way through Nabokov (I hated Lolita) and adoring Olga Ilyin’s White Road (which I wrote about here).

I continued reading in the Russian-translated canon after I became an adult–working my way through Nabokov (I hated Lolita) and adoring Olga Ilyin’s White Road (which I wrote about here).

The week after I came home from the hospital with my first child, I got a copy of Robert K. Massie’s next volume: Peter the Great. Engrossed in the book, I nursed my newborn for hours, hardly wanting to break away from the absorbing story.

It remains one of the finest biographies I’ve ever read. I wrote Massie a fan letter, in response to which he sent me a postcard.

Suzanne Massie, meanwhile, become a russophile herself and was well-known for her talks, insights and books about Russian. I’ve got a copy of her beautiful, Land of the Firebird: The Beauty of Old Russia on my bookshelf. In it, I read a history of the Romanov influence on Russia through the lens of art, music, poetry and literature.

Shortly thereafter, my mother and I revisited Journey. Two of my maternal cousins and I were pregnant when we learned my maternal uncle’s mysterious life-long ”bleeding” problem was a mild form of hemophillia. We became well-versed on the subject when I gave birth to a third son. Fortunately, none of my children inherited hemophillia.

But I thought of the Massie’s son through the years and in 1999, looked him up on the Internet. What had become of such a promising man, particularly in the age of HIV? Hemophiliacs were affected in a disproportionate way to the rest of society.

Bob Massie not only was alive, but he had become a medical curiosity. As one of the few people in the history of HIV research to have developed an immunity to the disease, Massie the son was the focus of a program on PBS’ Nova. (The transcript can be read here.) His story is one of amazing courage, fantastic educational opportunities, important international work, and his ministry as an Episcopal priest.

He’s also a fine writer like his parents and last night I finished reading Bob Massie’s A Song in the Night: A Memoir of Resillience. The opening chapters remember a childhood of suffering and hoping for a brighter future. The middle discussed his fascination with a foreign country: South Africa, and the difference he made in helping people understand apartheid. He took his magnificent gifts, overcame enormous odds by the grace of God, and made his personal knowledge of suffering serve a good purpose for the lives of others.

I’m grateful for the insight Bob Massie gave me through his book and that reminded me of the enormous debt I owe his parents. The family has enriched my intellect, inspired blood donations, served as an example of how to raise my own bright children, and given me many hours of enjoyment.

The works of Robert K. Massie, Suzanne Massie and Bob Massie, changed my life.

Thanks.

Did anything grip your imagination as a teenager and carry you into a different place, time and culture?

October 2, 2012

Thank You, Edith Schaeffer

I selected purple stock and variagated magenta and white carnations the other day at the grocery store and happily arranged them in a glass vase when I got home.

I selected purple stock and variagated magenta and white carnations the other day at the grocery store and happily arranged them in a glass vase when I got home.

I love stock’s scent and when I stood back to admire the flowers, I thought of Edith Schaeffer.

I buy flowers because of a now 98-year-old widow living in Switzerland, who fashioned a comfortable home for her husband and family–not to mention countless visitors.

Edith Schaeffer taught me about gracious home -making. From her books and articles, I discovered it often is the small touches that can change the atmosphere in a home for the better.

I grew up the daughter of a matter-of-fact teacher more interested in getting the family fed than pausing to make dinner actually look good. Vegetables always went from the stove to the table, still in their pot. Leftovers were stuck in the refrigerator willy–nilly, sometimes still in their original pans and often to be resurrected in their dessicated state the next night for dinner.

It wasn’t my mother didn’t like good food and fine dining. She simply didn’t have time for gracious living while she was trying to make a living.

I had more time than she did when my children were growing up, and I lived in a circle of military wives, many of whom were better versed in making a home than I was.

I could admire their “suites” of furniture (what did that mean?), and their matching dishes (we all had matching dishes the first years of our marriages), but I had never paid any attention to throw cushions or the purpose of crystal.

Besides, shouldn’t Christians be more interested in simple living than extravagant expenditures?

As one of the founders of L’Abri, Edith Schaeffer insisted there was more to life than just making-do. She wrote of putting together a beautiful tray of food for her husband–a tray that included not just the tea cup, but a small pitcher of milk, the tea pot, a lovingly prepared snack, and perhaps a posy.

As one of the founders of L’Abri, Edith Schaeffer insisted there was more to life than just making-do. She wrote of putting together a beautiful tray of food for her husband–a tray that included not just the tea cup, but a small pitcher of milk, the tea pot, a lovingly prepared snack, and perhaps a posy.

Son Frank Schaeffer now dismisses the importance of those trays, but for me at the time they constituted an example of adding beauty to the humdrum. Life didn’t have to be utilitarian, it could have a simple touch of something special.

At Edith Schaeffer’s instigation, I broke out the cloth napkins- my mother never used anything but paper napkins at home–and put the wedding napkin rings into service. I tossed a table cloth across the table and put the vegetables in an actual serving bowl.

Sure, I had more dishes to wash as my mother would have pointed out, but dining felt more like dining than eating, now. The leftovers went into plastic anyway.

From Edith and her sisters in gracious living, I learned the knack of taking a leftover and turning it into something else. No gnawing on dry hard roast beef for my kids, I chopped the (still moist from the tupperware) leftover meat and turned it into Shepherd’s Pie.

My children grew up never suspecting another way. They always passed serving bowls, not hot pots, at the dinner table and flowers in the house were a part of their childhood.

All because of Edith Schaeffer.

Thanks.

What writers have influenced even simple ways you live?

September 28, 2012

A Tale of Two Churches

The real body of Christ

As mentioned before, we recently visited our “home” church in Groton, Connecticut: Bishop Seabury now-Anglican Church.

They were evicted from their church building in early August and decamped to a local hotel for services. We visited on the third Sunday in their new locale.

The service was set up in a lovely ball room, padded chairs facing a makeshift altar. The processional came in, as always, with assistants in albs and the presiding priest wearing the same white robe with a green stole about his neck.

We didn’t have the leather-bound Book of Common Prayer–apparently the books had to remain with the church building–but we did have the order of service and the songs printed on a stapled-together booklet.

We knew all the music.

I confess, even though we haven’t been official members of this church body in 26 years, I glanced around looking for familiar people. I knew the Venerable Rev. Ronald Gauss would not be there–we had emailed beforehand–but I was surprised at the number of people I did recognize.

And blessing of all–they recognized me!

I rejoiced when we said that morning, “let us go to the house of the Lord,” with the good folks of Bishop Seabury.

I sighed with pleasure to worship our God with them in an unfamiliar setting.

And we threw out arms about each other when our sisters and brothers in Christ welcomed us home.

Thanks be to God.

Oh, and the church body? They are doing beautifully. More than one said, “the church is the body of Christ, the fellowship of believers, the people. A building is just a building.”

Amen.

A week later, we were at a completely different worship service. At the recommendation of friend Pastor Bill Giovannetti, we visited the Brooklyn Tabernacle.

Oh, my.

Bill pastors his own 4000 member Neighborhood Church in Redding, California, but he thought I might appreciate a glimpse of an even larger church. Since we regularly worship with at most 300 people, he was correct.

Brooklyn Tabernacle

Their services aren’t held in a conventional building either, but when you have 16,000 members, you need a big auditorium.

Nowhoused in the former Carleton Theater theater, it featured a stage on which sat some 150 or so singers. The Brooklyn Tabernacle Choir has won Grammy awards, and they were in full voice, though casually dressed, Labor Day weekend.

I’ve never attended a worship service with so many people–easily over a thousand–and the singing enveloped us with so many voices. With the choir on stage, the sound felt almost physical as it rolled towards us. I could practically feel my bones shivering!

In particular, “It is Well with My Soul” had such an enormous emotional element to it, I cried. The calling chorus–the choir singing “It is Well,” while we responded with the same, reverberated with enormous power.

It was so well with my soul by the end of that, when Pastor Cymbala told us to hug the person next to them, I stretched for the beautiful black woman beside me and hugged her tight–leaving my tears on her cheeks!

Pastor Al Toledo from the Chicago Tabernacle preached to the point and practically on Romans 12, one of my favorite passages. I took notes!

We left the Brooklyn Tabernacle nearly as energized as we had left Bishop Seabury. It just showed us, that as the Bishop Seabury people know so well–it’s the people, the God, the worship, that is most important on Sunday mornings.

A building is just a building, but the body of Christ is the people responding to their God!

Amen!

September 24, 2012

A Little Chagall Art Mystery–part 2

Well, if your aunt asked you to explore the possibility of a painting being the work of a famous painter, what would you do?

(See the last post for background).

There’s the painting. It has no artist’s signature. It requires a visit to at least New York and possibly Paris.

Are you in? Do you want to find out?

My niece was willing to help, but the painting never got to Paris. Cathleen and I started worrying about what would happen if Avtar crossed international borders carrying a framed piece of paper in and came out with the work of a master. Would there be duty to pay?

We researched and checked and ultimately the painting did not get to my niece in time to go to Paris. Once Avtar did receive it in New York this spring, Chagall’s granddaughter advised her to get the Paris Committee to rule.

They did.

No. It is not a real Chagall.

Bummer.

I should have realized how many forgeries exist from well-known painters of the last century. Salvador Dali was famous for signing his large signature on all sorts of empty canvases before his death. The idea was, since the signature was real, his students could paint in Dali’s distinctive manner and command high prices.

Dali, however, may have had some compunction at the last–his signature is so different in so many different ways–115 in all–now no one can tell an authentic signature from a later one.

I met two young men once who were just back from the Tahitian south seas islands where French artist Paul Gaugin went native. They had met several of his descendents and paid them to produce ”primitive” paintings in the style of their grandfather.

“Genuine Gaugins!” the young men explained, trying to make me understand why someone would pay a lot of money for artwork that looked, well, pretty primitive to me.

“Genuine Gaugins!” the young men explained, trying to make me understand why someone would pay a lot of money for artwork that looked, well, pretty primitive to me.

How do you tell if a painting you like is really painted by a famous painter?

Does it matter?

Only if you’re paying a lot of money.

The fact is, I liked the faux Chagall painting no matter who actually painted it.

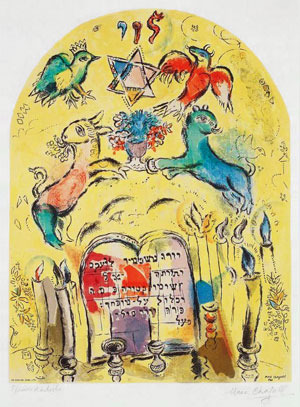

Here’s a real one with a provenance. Do you see similarities? The asking price starts at $25,000. No wonder some one might be tempted to copy it.

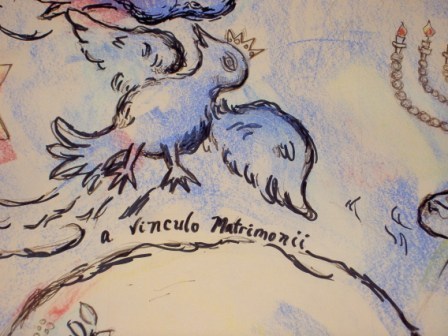

The Chagall we’ve been working with had similar details to this real one. Closer examination showed pencil markings on the paper used by whomever painted it. We were curious from the start, however, by those words painted in the middle: vinculo matrimonii.

The term “vinculo matrimonii” is a Latin term meaning “from the bonds of marriage.” Attempts to find more information on the Internet refer to divorce a vinculo matriomnii–in which the bonds are severed. But this doesn’t look like a divorce document to me.

One of my relatives suggested it could be akin to a Jewish ketubah–a highly decorated nuptial agreement used in some Jewish weddings.

Nice try, but ketubahs, even ones stylized after the works of Marc Chagall, include detailed writing. This one just has the two Latin words and the potential for something written on the Ten Commandments-type plaque.

We like the idea, though, of a link to marriage.

The table could be an altar, the circular lines above the table could indicate the traditional canopy for a Jewish wedding. Certainly the menorah and the star of David suggest a Hebraic tradition.

We’re not Jewish, but we appreciate the history–onto which my Christianity is considered to be grafted in according to Romans 11.

In the meantime, no matter who the painter turns out to be, we just like the painting. So we bought it from the Redwood Gospel Mission and had it framed.

It’s our anniversary, after all, and we love a piece of art with a story behind it.

What do you think this painting might be about? Who might have painted it and why?

September 21, 2012

A Little Art Mystery–in the Style of Marc Chagall

I stopped to visit my friend Cathleen at the Redwood Gospel Mission last fall. She oversees special donations to the mission’s thrift shop.

I stopped to visit my friend Cathleen at the Redwood Gospel Mission last fall. She oversees special donations to the mission’s thrift shop.

On her desk was a painting.

“I’ll take it,” I said.

It was the first time I’ve ever said something like that upon first laying eyes on a painting.

For those of you with any art background, who do you think the painter might be?

“It looks like a Chagall,” I said.

Cathleen smiled like a satisfied cat. “We think it may be a Chagall, and no, not yet.”

And such is the beginning of, not madness exactly, but a quest.

The painting is unsigned, but it has many characteristics of the work of Marc Chagall, a Russian-French painter from the last century (he died in 1985). I’m not an art historian, but even I could see them.

Look at this Chagall–do you see similarities?

How about this one?

“How do you determine who painted it?” I asked.

Most significant paintings have a “provenance” (from the French word provenir–”To come from”), a carefully documented list of owners to verify ownership and ensure people do not unwittingly purchase a forgery. As it turns out, there’s an entire website about Marc Chagall forgeries.

Who knew there was such a big business?

This particular painting–it’s a watercolor about 16 inches by 22 inches–was donated to the Redwood Gospel Mission when a local resident’s home was dismantled following a death. Because it wasn’t the usual type of donation–clothing, housewares or appliances–Cathleen received it and was trying to determine if the painting should be evaluated, and thus sold, at a higher than normal price.

“We’ve sent a letter and photos of the painting to the San Francisco Musem of Modern Art. They told us they could not make a determination and suggested we contact Bella, Chagall’s granddaughter, who lives in New York City,” Cathleen explained.

Bella is very busy and doesn’t have time to look at every potential Chagall, so she recommended they contact the committee in Paris. If they thought it might be a “real” painting by her grandfather, she’d take a look.

“Do you know anyone in Paris by any chance?” Cathleen asked.

As a matter of fact, I did. My art major niece was spending a semester abroad in Paris.

“Do you think we could send the painting to her and then she could walk it into the Chagall Committee in Paris to ask them to evaluate the painting?” Cathleen’s eyes danced.

“Possibly, but a better choice would be her sister who is going to visit in early December. She could hand carry it.”

“Great idea.” Cathleen nodded. “Where does the sister live?”

Now it was my turn to smile. “New York City.”

Cathleen’s eyes lit up. “If she lives in New York, do you think she would mind stopping in and seeing Chagall’s granddaughter with the painting? And if the granddaughter wasn’t interested, she could just say she was taking it on to the committee in Paris.”

This is the subject line on the e-mail I sent my niece Avtar:

“A Mission–hopefully not impossible–in NYC and Paris; are you up for a possible adventure?”

But then I had second thoughts and I included the following:

“I realize this sounds like the opening chapter in a spy novel–you know beautiful young woman gets a mysterious request from an elderly aunt about a work of art– but I have NO reason to think this might be dangerous.

“But then, isn’t that what they all say?”

Well, what would you do if your aunt asked you?