Elisabeth Storrs's Blog, page 21

September 14, 2012

Dying for Rome - Tarpeia

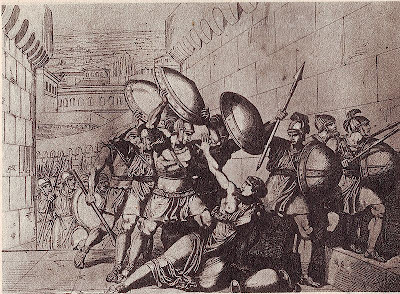

The Death of Tarpeia

The Death of TarpeiaThe tales of famous Roman women such as Lucretia and Virginia serve to reinforce the stereotypes of the ‘matron’ and the ‘virgin’ as exemplars of Roman virtues. Both these women died tragically: one defending her family’s honour by suiciding, the other murdered by her father for the same purpose. Their deaths were seen as catalysts for rebellion against oppressive and corrupt rulers. However, these women were not the instigators of great social reform. They gained fame as victims while their men were hailed as heroes for spurring the Roman people to oust the defilers of their wife or daughter.

There is another girl of Roman legend whose death led to victory over one of Rome’s enemies. Her name was Tarpeia. Yet she is not remembered as a martyr but as a traitor; not as virtuous but venal.

Early regal Rome was basically a township located on a few of the seven hills which eventually comprised the great city. The Romans were always scrapping with their neighbours. The nearby Sabine tribe was at constant loggerheads with King Romulus as both peoples fought over the same territory. The conflict reached its climax when the Roman monarch devised a ruse whereby the Sabines’ daughters were abducted to provide wives to his men. The incident became known as the Rape of the Sabines . As a result, King Tatius gathered his army outside the Capitoline Hill to reclaim the women and conquer Rome.

The Rape of the Sabine Women - Nicolas Poussin

Tarpeia was the daughter of the governor of the Capitoline citadel. One day, when she journeyed outside the city walls to fetch water for a sacrifice, she spied the enemy troops lying in wait. Legend goes that she was dazzled by the sight of the heavy golden bracelets and fine jewelled rings that the men wore. Sensing her greed, the Sabine king bribed her to open the citadel gates so that a party of his men could enter. The price she demanded for betraying her people was to be given what the soldiers ‘wore on their shields arms.’

Alas, poor Tarpeia. Her fate was to serve as a lesson to all who sought profit over loyalty to Rome. After she allowed the Sabine warriors to gain passage into the city, they turned and killed her. Instead of showering her with golden bracelets and rings, they struck her with the shields they bore on their left arms, heaping the weight upon her until she was crushed. For even the enemy found her treachery repellent.

Once inside the citadel, the Sabines quickly overran the surprised occupants, forcing the Romans to retreat to the Palatine Hill. The girl’s perfidy, though, did not cause utter defeat. Stung by the duplicity, Romulus called upon the gods to deliver Rome’s land back to its rightful people. With renewed spirits his army advanced upon the foe.

Strangely enough, the bloodshed was stopped from an unexpected source. The kidnapped Sabine women, who’d now become Roman mothers, appealed to both sides to unite instead of waging war. Here, for the first time, women were the authors of change. The kidnapped women rose above the crime committed against them and persuaded their Sabine fathers and Roman husbands that there was advantage in joining forces. As a result, Rome’s population doubled and its defences were reinforced against the next wave of Latin tribes who sought to seize Roman land. However, we know none of these Sabine women’s names. They were anonymous even though influential.

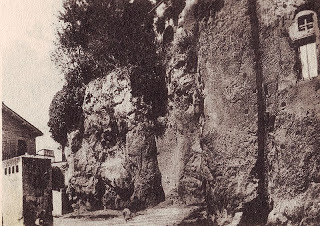

Legend tells us that Tarpeia’s body was buried beneath a cliff on the southern summit of the Capitoline. Towering 25 metres above the Forum this site forever bears her name. And for centuries afterwards, all notorious traitors were thrown from the Tarpeian Rock, a fate worse than death because it carried the stigma of shame.

The Tarpeian Rock

Historians have chronicled numerous, complex accounts of male Roman politicians, generals and traitors but there only a few stories of famous Roman women. Their stories are morality tales to be handed down from generation to generation. Whether a paragon of virtue or the epitome of disgrace, Tarpeia, Virginia and Lucretia will always remain cyphers – dying for Rome, not living to lead revolution.

Images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons and Russian Wikipedia

Elisabeth Storrs

Subscribe to Triclinium - Sign up for email subscription at the bottom of the page or click the RSS feed button on the sidebar.

Published on September 14, 2012 04:17

August 10, 2012

On Inspiration: Interview with M Louisa Locke

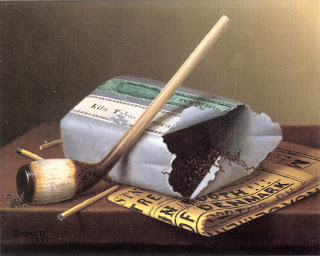

A Smoke Backstage - William Harnett

A Smoke Backstage - William Harnett My guest today is M. Louisa Locke, a retired U.S history professor who has recently published the first two books in a series about Victorian San Francisco, Maids of Misfortune and Uneasy Spirits , both best-selling historical mysteries on Kindle. Locke blogs frequently on self-publishing, is a featured contributor to Publetariat, and is on the Board of Directors of the Historical Fiction Authors Cooperative. She lives in San Diego with her husband, a dog and two cats, and she is working the third book in her series, Bloody Lessons. You can find more about her work on her website and follow her on twitter and facebook.

What or who inspired you to first write?I have wanted to be a writer since I was about 12; I even put writing as my career goal in my senior high school yearbook. As a rather shy and solitary child, I found books provided me with solace, widened my understanding of the world, and entertained me, and I couldn't imagine anything better than to do something that would bring the same kind of joy to others. While I eventually pursued a different profession, getting a doctorate in history and becoming a college history professor, I never lost my dream of being a writer. So, when I semi-retired from teaching, I pulled out a draft of a book I had been working on for years and rewrote and published it. This book, Maids of Misfortune, set in 19th century San Francisco, weaves in the details I had learned in writing my doctoral dissertation on working women in the American west into a light romantic historical mystery, and it has been unexpectedly successful. It may have taken me fifty years to realize my dream, but it has certainly been worth the wait.

What is the inspiration for your current book?Uneasy Spirits, the sequel to Maids of Misfortune, was inspired by my curiosity about 19th century Spiritualism (the belief that the dead--as spirits--could communicate with the living.) While I hadn't written about this phenomena in my dissertation, when doing my research I couldn't help but notice the substantial number of females who advertised in the local San Francisco papers in the 1880s that they were clairvoyants, fortune tellers, and trance or spiritual mediums. In Maids of MisfortuneI had already made my series protagonist, Annie Fuller, pretend to be a clairvoyant, so that she could use her business expertise to make money (something Victoria Woodhull and her sister, two radical women of the period, had done successfully.) But I also knew that Spiritualism was a popular 19th century religious belief that was taken seriously by educated middle class Victorians, and, as I researched it, I discovered it was also the route that a number of women used to become active feminists. Yet there were numerous stories of "spirit mediums" who were clearly frauds, using the naive beliefs of many to bilk them of money. I wanted to write a book that would illuminate not just these fraudulent practices (with the fun of rigged séances, etc.) but also would examine the reasons why people embraced these beliefs, leaving it to the reader to answer the question of whether or not any of the spiritualists of the time might be the real deal.

Is there a particular theme you wish to explore in this book?Because I am dealing with a time period of transition for women, (who were beginning to enter the professions in unprecedented numbers, winning the vote in western states, yet being treated as frail sex objects in ridiculous corsets and bustles), one of the themes for all my stories is the difficulty of being an independent woman in the Victorian era. Most of my female characters are independent because they have to be, they are from the working classes, or widowed, and they must support themselves financially. In the case of Annie Fuller, the disaster of an earlier marriage has led her to be particularly wary of losing her hard won financial independence, but it also has made it difficult for her to ask for help, develop an honest relationship with the man who loves her, and even trust her friends. So throughout my series a common theme is the difficulties for both men and women in balancing individual personal freedom with the demands of friendship and family within the context of rigid social mores. (This sounds so serious-but the truth is this theme lends itself to fun arguments between the two protagonists, Annie Fuller and Nate Dawson, and a good deal of suspense.)

What period of history particularly inspires or interests you? Why?The period that most interests me is the late 19th century and early 20th century (broadly 1870-1920), which encompasses the late Victorian and the early Progressive eras in U.S. history. As mentioned above, this was a period of incredible economic, social, and political change, that included two terrible depressions (1870s and 1890s), the rise of modern industrial monopolies, corrupt politics, and a series of reform movements that became the foundation of many of the institutions we take for granted today in America––kindergartens, a juvenile court system, conservation, women's suffrage, the secret ballot (known back then as the Australian Ballot!) child labour laws, work place safety rules, etc.

As a woman who came of age in the period of the 1950s and 1960s and was active in the civil rights and feminist movements, I found this period disconcertingly familiar when I began to study it in graduate school. I was particularly interested in how women of that period, like women of my generation, negotiated the difficult tasks of balancing home, family, and work in a society that was either overtly against the idea of equal rights for women or more subtly undermined it by continuing to expect that women would be the primary care takers of the nation's children and elderly.

What resources do you use to research your book/s?I am fortunate in that I have a doctoral dissertation that I had researched and wrote for 5 years entitled "'Like a Machine or an Animal': Working Women of the Far West at the end of the Nineteenth Century" to fall back on when I need details about my time period or San Francisco. I also have the books I accumulated while writing that dissertation and later when I began to teach U. S. Women's history as a college professor. However, what I love about writing now is the resources that exist on the internet. Materials that I had had to get through inter-library loan, or go to archives to read in person (1880 San Francisco Chronicle, memoirs and diaries, historical maps, etc) are now often accessible on line. And, since I don't live in San Francisco, I can also look at google street view to remind me of the terrain my characters would be traveling through as they go from place to place.

Which authors have influenced you?My earliest influence were the Regency Romances of Georgette Heyer that I began to read in high school, when I ran out of books by Jane Austen. I would hope that people who read my books would recognize my homage to the kind of social commentary mixed with romance and humour that these books had. In graduate school I discovered Dorothy Sayers and her Harriet Vane-Peter Whimsy books, particularly Gaudy Night, and these books became the model for how to write literate, thoughtful mysteries with amateur sleuths who are also romantic leads. Ellis Peter's Brother Cadfael mysteries set the standard for the historical mystery sub-genre for me, and Tony Hillerman's mysteries set in New Mexico and featuring Native American characters taught me the importance of place and character-driven plots to a successful mystery. There are obviously excellent contemporary authors I could draw on, but these above were my earliest teachers.

What do you do if stuck for a word or a phrase? Let it go; it usually comes to me later. I like to rewrite, so there is always another chance to come up with the right one.

Is there a particular photo, piece of art, poetry or quote that strikes a chord with you? Why?

While I don't usually use art as a form of inspiration (besides having a variety of music playing in the background while I write) there was one artist who proved to be an inspiration for a character in my first mystery, Maids of Misfortune. When I wrote the first draft of this book in the late 1980s, I decided that one of my characters (Jeremy Voss the murder victim's son) was going to be a unique but misunderstood painter. For some reason, I recalled several paintings I saw at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City a decade earlier, where the artist had worked in a style of extreme realism. This was before the internet provided a handy way of looking up almost anything, so I didn't even know the name of the artist, or the style, but these paintings (and the monumental box sculptures by Louise Nevelson) were the only works of art I remembered from that visit to the museum. From my vague memory of these realistic still life paintings I created my description of Jeremy Voss's work.

Recently, when I was working on rewriting Maids of Misfortunefor publication, I decided to see if I could figure out who the paintings were by, what the name of the style was, and if it was at all realistic that my young artist working in the 1870s would paint in a similar style. What I discovered as I did my research on the internet absolutely delighted me. The style is called Trompe l'oeil, and, while it was a style with a long history, the most famous modern artist to work in the style was a19th century American artist named William Harnett. When I looked up what works of his were in the Metropolitan Museum at the time when I visited, there were the paintings I had remembered. Even more astounding, Harnett had done these paintings in the late 1870s and 1880s, which fit perfectly into my time line! So those paintings I saw almost 40 years ago ended up being an important inspiration for my writing.

By the way, I also searched and found pictures of those Louise Nevelson

"boxes" that I had remembered so well, and I found that at least one of them had been donated to the Museum just a few years before my visit. Who knows, maybe those boxes will show up in some of my future work as well.

[image error] Still Life: Violin and Music - William Harnett

What advice would you give an aspiring author?My main advice is to write the stories you would want to read. You are going to have to live with the world and characters you create for a long time, so make sure you enjoy the process. Second, make sure you develop a team of people (and this should include professional writers-perhaps as part of a writers group) who will be willing to read your work and comment on it honestly as you begin the process of rewriting and editing. Whether you are planning on submitting to an agent or editor to go the traditional publishing route or you are planning to self-publish, your work is going to have to be a mature and polished as it can if it is going to bring you success.

What is your next project?I am just starting to outline my third book, Bloody Lessons, which will continue my series on Victorian San Francisco mysteries. While Maids of Misfortune featured details on the experiences of domestic servants, and Uneasy Spirits explored 19th Century spiritualists, this third book will look into the teaching profession––the most popular profession for middle class women and one of the few that provided a living wage for females in the period. In doing my research I have begun to discover that many of the problems that teachers are facing today were very prevalent in 1880 California (public attacks on teachers' salaries, rising class sizes, inadequate funding, and controversies over text book content and the role of religion in the schools) as well as a number of juicy scandals that have provided me with lots of inspiration as I plot this new book.

In this sequel to Maids of Misfortune, it is the fall of 1879 and Annie Fuller, a young San Francisco widow, has a problem. Despite her growing financial success as the clairvoyant Madam Sibyl, Annie doesn’t believe in the astrology and palmistry her clients think are the basis for her advice.

Kathleen Hennessey, Annie Fuller’s young Irish maid, has a plan. When her mistress is asked to expose a fraudulent trance medium, Arabella Frampton, Kathleen is determined to assist in the investigation, just like the Pinkerton detectives she has read about in the dime novels.

Nate Dawson, up-and-coming San Francisco lawyer, has a dilemma. He wants to marry the unconventional Annie Fuller, but he doesn’t feel he can reveal his true feelings until he has a way to make enough money to support her.

In Uneasy Spirits, this cozy, romantic novel of suspense, Annie delves into the intriguing world of 19th century spiritualism, encountering true believers and naïve dupes, clever frauds and unexplained supernatural phenomena.

She will soon find there are as many secrets as there are spirits swirling around the Frampton séance table. Some of those secrets will threaten the foundation of her career as Madam Sibyl and the future of her relationship with Nate Dawson, and, in time, they will threaten her very life itself.

Thanks Mary Louisa for sparing the time to share a little of your life here. You are an inspiration and great support to indie authors. Hurry up and finish Bloody Lessons.

You can buy the first two books in the Victorian San Franscisco Mysteries at Amazon.

Maids of Misfortune Amazon US , Amazon UK

Uneasy Spirits Amazon US, Amazon UK

Images of William Harnett's paintings courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Elisabeth StorrsSubscribe to Triclinium - Sign up for email subscription at the bottom of the page or click the RSS feed button on the sidebar.

Published on August 10, 2012 04:32

August 3, 2012

Review: The Absolutist by John Boyne

It is always shocking to be reminded that the majority of those sent to war are boys. The Absolutist, by John Boyne, brings this home with a poignant telling of the cruelties that soldiers wreak upon each other; not just against their enemies but also within their own ranks.

Tristan returns from the Great War to peace-time England. He is about to turn twenty one but he has already suffered and seen horrors over his four years on the battlefields of France. It has been long enough time to consider him as a man. And long enough time to acquire demons that haunt him.Tristan’s story spans memories of his childhood through to the time immediately after the war. It is made clear that he has long been troubled, having been shunned by his family before embarking on military training at Aldershot. His travails continue during his time in the trenches of the Somme where he is impelled into a world gone mad, and where savagery reigns.

In such a situation, the concept of not doing your duty to King and Country, namely ‘going over the top’ to enter into a lottery of survival in ‘no man’s land’ will not be brooked. Conscientious objectors, however, are not spared the threat of death. Required to act as medics, they must also face the perils of battle. Furthermore they are reviled and subject to the brutality of others who fail to comprehend their ethos. They are called ‘feathermen’ because those who judge them as cowards give them white feathers as a symbol of a lack of bravery.

Tristan’s best friend, Will, has been executed as a traitor. Feeling obliged to return Will’s letters to his sister, Marian, the young veteran also struggles with a guilty secret he feels he must confess to her. Boyne maintains the reader’s attention by a skilful unravelling of this mystery. The readers is drawn to the story of the two young friends who gain comfort from each other when forced to cope with the unfamiliar regime of basic training and then the terror of mortal combat. I found the slow progression of this relationship to be compelling as the explanation is revealed as to why Will has decided to become an absolutist – a man who not only lays down his arms but refuses to do any act that contributes to the war effort. An act that is regarded as treason with the penalty of death by firing squad.

The choices that the two friends face are monumentally terrifying. They are expected to act like men yet they are only boys whose emotions are raw and confused. As such The Absolutist is an odd coming-of-age story as much as an examination of the hypocrisy and futility of war. Most of all, the novel forces the reader to consider the nature of cowardice and courage. Will is portrayed as brave even though branded as a traitor while Tristan, physically valiant, grapples with his own failure to make a stand.

Boyne’s style is flowing and engrossing, and his depiction of the lives and mores of those fighting during that ‘war to end all wars’ is vivid and real. The ending, though, was disappointing as the reader is finally shown an aging Tristan, tormented by his memories and choices. It may well have been best if the author had left him as a callow youth steeling himself to confront the truth of betrayal, loss and courage – and the assessment of whether he was a featherman after all.

Elisabeth Storrs

Subscribe to Triclinium - Sign up for email subscription at the bottom of the page or click the RSS feed button on the sidebar.

Published on August 03, 2012 04:05

July 13, 2012

On Inspiration: Interview with Nicole Alexander

On The Wallaby Track - Frederick McCubbins

On The Wallaby Track - Frederick McCubbinsMy guest today is Nicole Alexander, a fellow Aussie author who shares the sources of her inspiration with us. In the course of her career Nicole has worked both in Australia and Singapore in financial services, fashion, corporate publishing and agriculture. A fourth generation grazier, Nicole returned to her family’s mixed agricultural property west of Goondiwindi in the mid-1990s. She is currently the business manager there and has a hands-on role in the running of the property. Nicole has a Master of Letters in creative writing and her poetry, travel and genealogy articles have been published in Australia, America and Singapore. Nicole is recognised as Australia’s Bush Storyteller. Her rural fiction novels, The Bark Cutters (shortlisted for the Australian Book Industry Awards Newcomer of the Year 2011) and A Changing Land are Top Ten bestsellers and are available in Australia, New Zealand, Germany, America and Canada.

Nicole's rural literature combines a wonderful mix of modern and historical characters with story lines that are compelling. Her new book, Absolution Creek, is set 1920's Australia. As I love historical fiction, I'm glad she has veered firmly into past times.

What or who inspired you to first write?

I became intrigued by the craft after I was approached to contribute to a non-fiction work in celebration of Australia’s bicentenary celebrations in 1988. What is the inspiration for your current book? The idea for the narrative for Absolution Creek came from a story my grandfather told my father in the 1940s. While travelling across the Garah plains an area some forty kilometres to the east of our rural property (I live northwest of Moree on the NSW/QLD border) a young child travelling with family fell from the rear of a dray and was never found. Unfortunately such events were not uncommon in the eighteenth and nineteenth century in rural Australia when roads were barely formed tracks and travelling was arduous.

Is there a particular photo, piece of art, poetry or quote that strikes a chord with you? Why? I am a lover of a great many paintings and poems, however I am a fan of the Australian impressionists, in particular, Frederick McCubbin and Tom Roberts. Their ability to intrude upon their internal narratives, with the external is magical.

A Break Away - Tom Roberts

Is there a particular theme you wish to explore in your book? Redemption for past acts committed and identity are the major themes of Absolution Creek. The quest for salvation, at many levels, is the driving force behind the narrative.

What period of history particularly inspires or interests you? Why? I have always had a great interest in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, in particular rural Australia. As a fourth generation grazier I marvel at the hardship and isolation that settlers endured as they carved a place for themselves in the Australian bush.

What resources do you use to research your book/s? I’m fortunate in that I am able to draw on a large amount of archival material from my own family history. Paddock books and station diaries from the late 1800s, mail-order catalogues (which my own family ordered from) and magazines from the 1920s and a plethora of incidental material. Absolution Creek begins at the time of the construction of the Sydney Harbour bridge, so I haunted the state library of NSW for a number of days searching archival material. I was particularly interested in the displacement of whole suburbs when initial construction work began on the bridge’s approaches.

Which authors have influenced you? Ernest Hemingway for his sparse prose and David Malouf for his ability to render the human condition in such an emotive yet recognisable way.

What do you do if stuck for a word or a phrase? I tend to leave a blank and return to it later.

What advice would you give an aspiring author? Three words, perseverance, passion and patience. Once you have your story on paper writing is all about redrafting. What is your next project? I’m currently working on a novel set during WW1, however, it’s early days as yet …

In 1923 nineteen-year-old Jack Manning watches the construction of the mighty Harbour Bridge and dreams of being more than just a grocer’s son. So when he’s offered the chance to manage Absolution Creek, a sheep property 800 miles from Sydney, he seizes the opportunity. But outback life is tough, particularly if you’re young, inexperienced and have only a few textbooks to guide you. Then a young girl, Squib Hamilton, quite literally washes up on his doorstep – setting in motion a devastating chain of events…

Forty years later and Cora Hamilton is waging a constant battle to keep Absolution Creek in business. She’s hindered, however, by her inability to move on from the terrible events of her past, which haunt her both physically and emotionally.

Only one man knows what really happened in 1923. A dying man who is riding towards Absolution Creek, seeking his own salvation…

From the gleaming foreshores of Sydney Harbour to the vast Australian outback, this is a story of betrayal and redemption and of an enduring love which defies even death. Absolution Creek will be released in September 2012.Nicole's books can be found here. Thanks so much, Nicole, for sharing your thoughts with us and best of luck with Absolution Creek.

And why not read one of Nicole's books for AWW2012 ?

Elisabeth Storrs Subscribe to Triclinium - Sign up for email subscription at the bottom of the page or click the RSS feed button on the sidebar.

Published on July 13, 2012 04:44

July 2, 2012

In praise of Elizabeth Lhuede, Australian Women Writers and The Stella Prize

I recently attended The Stella Prize lunch at the Sydney Writers’ Festival which was hosted by The Hoopla e-zine. The event was sold out. Apart from one brave male, I found myself in a room packed with an assortment of published women writers, book clubs and writers’ groups who had gathered to be entertained by Wendy Harmer, and listen to five fabulous Australian women authors, namely, Tara Moss, Di Morrissey, Anne Summers, Anita Heiss and Anna Krien.

The purpose of the lunch was to support the inaugural Stella Prize which has been set up to counter gender bias against women writers and rival other literary awards such as The Miles Franklin. The Miles Franklin Award is named after Stella Miles Franklinwho was compelled to write under a male pseudonym in order to be published at the turn of the 20th century. Sadly, despite being founded by a female, few women have been awarded this leading accolade. The Stella Prize (also named after the same author) will hopefully raise awareness of this imbalance.

If successful, the Stella Prize will recognise the cream of our country’s literary talent but what about women writers in general? And women readers? To her great credit, Elizabeth Lhuede of Australian Women Writers litblog has set up the Australian Women Writers Challenge 2012 to address this. The objective of the challenge (in Elizabeth’s words) is ‘to help counteract the gender bias in reviewing and social media newsfeeds that occurred throughout 2011 by actively promoting the reading and reviewing of a wide range of contemporary Australian women’s writing.’

I understand that her goal came from Elizabeth’s realisation (following upon a blogpost by Tara Moss) that a majority of women are nominating books written by men as their top reads. In other words, women are as guilty as the next person in failing to recognise the contribution Australian women authors are making to the literary landscape.

So what is involved in the challenge? It’s simple. Read and review Australian women writers throughout the National Year of Reading in 2012 then set up a link on Elizabeth’s blog. At last count there were 362 readers who’ve registered for the challenge. And 896 reviews posted!

Elizabeth has also given the opportunity for women authors to bolster their profiles by inviting them to post a review of a book outside their own genre. I was very excited to be able to do so by reviewing Josephine Pennicott’s Poet’s Cottage. Many thanks, Elizabeth, for inviting me to contribute.

As for the Stella Prize lunch, a trivia quiz with 18 questions was conducted as a way of adding interest to the proceedings. (It was diabolically difficult - or at least I thought it was!) The winner, who had correctly answered 16 of the questions, was duly given her prize. I don’t think she was asked her name. It was only later that I discovered it was Elizabeth Lhuede.

The irony of this was not lost on me. Here was a modest woman, a writer, who was making an enormous effort to assist The Hoopla’s own fantastic goal of advancing Australian women’s writing and the Stella Prize. And yet she went unrecognised. So I’m doing it now in a small way. Well done, Elizabeth. Thanks for all your hard work!

You can follow AusWomenWriters on Twitter and Facebook.

Enormous credit should also go to Shelleyrae at Book'd Out litblog who is a prodigious blogger and tireless reviewer for the challenge. Follow her on Twitter and Facebook or join her Goodreads discussion group on AWW2012.

And don’t forget to join the AWW2012 Challenge!

2 July 2012 by Elisabeth Storrs

Subscribe to Triclinium - Sign up for email subscription at the bottom of the page or click the RSS feed button on the sidebar.

Published on July 02, 2012 03:26

May 13, 2012

On Inspiration: Interview with Rebecca Lochlann

[image error] Gustav Klimt: 'Love'

The source of writer's inspiration always intrigues me. More so when a novelist writes historical fiction and is drawn to write of past times. Today my guest is Rebecca Lochlann, author of The Child of Erinyes Series.

[image error]

In her teens and early twenties, Rebecca began envisioning an epic story, a new kind of myth, one built upon the foundation of the Greek classics and continuing through the centuries right up into the present and future.This has become her life’s work, although she didn’t exactly intend it to be that way when she started.

The Child of the Erinyes series is mythic fantasy fiction, “loads of testosterone, slaughter, and crazy magic” (with a dose of romance.) The Year-god's Daughter is her first novel: Book One of The Child of the Erinyes Series. The Thinara King has just been released in both digital and paperback forms, and the third book, In the Moon of Asterion, will be available by the end of the year.

Rebecca has always believed that certain rare individuals, either blessed or tortured, voluntarily or involuntarily, are woven by fate or the Immortals into the labyrinth of time, and that deities sometimes speak to us through dreams and visions, gently prompting us to tell their lost stories. Who knows? It could make a difference.

What or who inspired you to first write and when did you start? That question takes me back many years, though I remember writing my first stories like it was yesterday. I was quite young: six or seven. I remember feeling like all at once, my tight, small, restricted world had opened up into a veritable universe, because my imagination, which no one could control or take away from me no matter how much they might want to, was given life and freedom. (Rather like the main protagonist of The Yellow Wallpaper?) I guess it was my mother who started me down this long and winding road; from the beginning, she encouraged her children to read. She took us to the library like clockwork every weekend. I still remember the wonderful quiet hours and bookish smell of that neighborhood library. It was magical. (Those old hard covers: does anything smell better? I don’t think so.)

Is there a particular photo, piece of art, poetry or quote that strikes a chord with you? Why? Many, actually: one that pops into my mind is Gustav Klimt’s “Love.” I do weave fantasy into my fiction—maybe even a little magical realism. That painting inspires an entire story—perhaps multiple stories. It seems to combine my beloved myths, romance, fantasy, the many varied faces of love, and the living, observant magic of trees. Another would be “The Oracle Of Delphi,” painted by John Collier, along with his “Lilith.” [image error]John Collier: 'Priestess of Delphi'

The Thinara King is the second book in a series. What was the inspiration for this series and how many books can we look forward to reading? When I first learned about the amazing civilization that existed on Crete for thousands of years, and I read the conjectures about how Crete could have been the dominant influence upon the West (rather than Athens) had it not met its mysterious end, I began envisioning what our world would be like if that had happened. How would we be different? It’s hard to know, since what we truly do understand of Crete is miniscule. Nobody knows for sure if Crete was a matriarchal society, (Those who state so emphatically that this would have been “impossible” are biased by some kind of personal prejudice, I think) but I chose to write it that way, which naturally led into the “what-ifs” for our present day. I had help in this idea, partially from Robert Graves, who figured that the term “Minos,” for so long attached to a king, was probably originally a title attached to a woman: either a queen or priestess—some sort of important female. I took that idea and ran with it.

Is there a particular theme you wish to explore in this book? Growth. Change. Preparation through adversity. Throughout the series, Aridela takes on the guise of the ancient trinity, “maiden,” “mother,” and “crone.” In the Bronze Age trilogy segment, she is the “maiden,” the immature innocent girl. Yes, she has been educated, but no amount of formal education can teach a young girl emotional maturity. She begins this long journey as your typical spoiled, sheltered ten-year-old child. The first boy she gives her heart to is Menoetius, a flawless youth of seventeen, but after he returns to the Greek mainland her memories of him fade. By the time she’s sixteen, she has followed in the footsteps of her countrymen and is obsessed with all things beautiful, as are most of the Cretans. Now a woman, she falls in love again, this time with Lycus, a beautiful Cretan bull leaper, and then with Chrysaleon, an equally beautiful Mycenaean. Yes, Aridela is shallow. How could she believably be anything else with the upbringing she’s had? Not only has she always been given whatever she wants, she has this aura of divinity which makes people treat her with awe; rumors claim she would make a better queen than her older sister. Aridela has no fear. No doubts. She is “confidence, epitomized.” Which pretty much guarantees she’ll be a poor leader.

Aridela lacks the qualities so important in a ruler and even more important in a girl chosen by Goddess Athene to travel through time and become her spokesperson. Humility. Caution. Compassion. The internal growth that disappointment, sorrow, loss and grief usually inspires. Aridela has been allowed to run free and be spoiled because her future is not considered as important as her sister’s. The Thinara King strips her of all that. In The Thinara King, this spoiled, shallow child is changed profoundly, taken down to her emotional skeleton. The only question is, will she survive it? Maybe not, and certainly not without help.

What period of history particularly inspires or interests you? Why? The Bronze Age certainly, which is the setting for the first three books of my series, but also the Victorian Age. I find both an absolute wealth of interesting people, myths, and events. So many fascinating people lived during the Victorian Age, and so many fascinating things happened. The Bronze Age captures my imagination partly because it’s not so well known; everything everyone believes about it is really just conjecture, mostly put together from pottery shards! That gives a writer the freedom to explore “what ifs.” The fourth, fifth, and sixth books are set in Scotland; I conducted years of research into the Highland myths and culture for those books, and discovered just how ancient, rich, and complex the Scottish tradition is. It’s more interwoven with the Bronze Age Cretan society than one might think. For instance: there are conjectures that the well-known Celtic goddess Morrigan or “The Morrígu,” was another name for Athene—the Cretans traded with the early British tribes, and no doubt they shared their beliefs. I’m also intrigued by Norse myths and culture, but haven’t really had the time to explore it. Maybe one day.

[image error] John Collier: 'Lilith'

What resources do you use to research your book/s? I have thousands of books, written by archaeologists, historians, speculative writers, mythologists and novelists. All have inspired me. The Internet, of course, has been invaluable in the last few years: but when I started, there were no personal computers. It was all longhand construction and books. It took a long time for the Internet to become a valuable partner in my writing. For many years it just wasn’t there or there wasn’t much to find on it. Consequently, I have relied mostly on books, maps, helpful local people, and travelling to/exploring the settings on my own.

Which authors have influenced you? Patricia A. McKillip is one of the greatest influences. She doesn’t write historical fiction, but her fantasy and her way of weaving words expands my mind. For the same reason, Peter S. Beagle will always linger at the top of my inspiration list, along with Yevgeny Zamyatin. Anita Diamant taught me that historical fiction doesn’t have to be dry or boring. The Red Tent is one of my all time favorite books. Authors like Anne Kent Rush and Charlotte Perkins Gilman have inspired me to think of women in new ways. My eyes and mind were initially opened by Anne Kent Rush, later by Riane Eisler, Robert Graves, Anne Baring, Carl Kerényi, and Marija Gimbutas. All these knowledgeable, generous authors were instrumental in helping me find my voice, my imagination, and the courage to explore the “what ifs.” What do you do if stuck for a word or a phrase? This has been happening to me more and more of late. It’s actually a little concerning. I remember when I could write for hours with hardly a pause. Now it seems like I find myself pausing more, searching for that one perfect word, although this may have more to do with the editing process rather than the creative process. I adore my thesaurus. Even if I can’t find the actual word I originally wanted, the choices make everything possible—I often find something better. Sometimes entire scenes can give me grief: I have been known to utilize dreams to help me with those. Athene steps in and provides the answers.

What advice would you give an aspiring author? Patience.

What is your next project? I am putting the polish to book number three in my Bronze Age segment: In the Moon of Asterion. It is the culmination of the story of Aridela, Chrysaleon, and Menoetius. Everything comes to a head as Chrysaleon fights to save his own life, Menoetius struggles with his obligations, loyalties, and desires, and Aridela confronts profound truths that explode everything she thought she knew. The scene is set for the continuation of the series in a very different time and place.

Ash, earthquakes and tsunamis devastate Crete and all the surrounding islands. The will of the survivors fades as their skies remain dark, frost blackens the crops, and nothing they do seems to cool the rage of the Immortals. Young Aridela faces an arduous task: reviving the spirit of her people and rebuilding her country's defenses. In the wake of the Destruction, she and Chrysaleon are closer than ever—knowing he must die in a few short months becomes torturous agony. How can she put this man she loves so much to death? Yet if she doesn't, she risks drawing even more divine anger down upon Crete's innocents.

Ash, earthquakes and tsunamis devastate Crete and all the surrounding islands. The will of the survivors fades as their skies remain dark, frost blackens the crops, and nothing they do seems to cool the rage of the Immortals. Young Aridela faces an arduous task: reviving the spirit of her people and rebuilding her country's defenses. In the wake of the Destruction, she and Chrysaleon are closer than ever—knowing he must die in a few short months becomes torturous agony. How can she put this man she loves so much to death? Yet if she doesn't, she risks drawing even more divine anger down upon Crete's innocents.More threats loom on the horizon—Greek kingdoms see a weakened Crete as easy prey. Chrysaleon faces his own demons as he feels the shadow of death over his shoulder. Will he thwart his fate? No other man ever has.

The Thinara King is book two of The Child of the Erinyes series.

You can purchase Rebecca's books at:The Thinara King at Amazon: http://tinyurl.com/6pm5oz2 The Year-god’s Daughter at Amazon: http://alturl.com/zhqydThe Thinara King at Barnes and Noble: http://tinyurl.com/7j6m8tb

Thanks so much Rebecca for sharing your journey with me.

13 May 2012 by Elisabeth Storrs

Subscribe to Triclinium - Sign up for email subscription at the bottom of the page or click the RSS feed button on the sidebar.

Published on May 13, 2012 18:09

April 27, 2012

Review: Birds Without Wings by Louis De Bernieres

A dense, enthralling and terrifying novel that describes man's inhumanity to man in the first few decades of the 20th century in Turkey, Greece and the Balkans.

A dense, enthralling and terrifying novel that describes man's inhumanity to man in the first few decades of the 20th century in Turkey, Greece and the Balkans.It is a sprawling saga with its genesis in the peaceful village of Eskibahce in the south west of Turkey. Here Turkish Muslims and Greek Christians have lived for centuries side by side, bemused by each other's idosyncracies but basically tolerant of each other. I was introduced to a plethora of characters whose foibles were gently exposed and whose failings were never as great as the politicians who controlled their lives from distant Istanbul and Ankara.

The microcosm of this village reflects the tribulations that face all those living in the Ottoman state. I followed the journey of two friends - one a Greek Christian, the other a Turkish Muslim who are separated by war and endure different horrors as one fights the Gallipoli campaign and the other is forced to act as a slave worker.

The Gallipoli campaign of First World War holds particular resonance for Australians. The date of the landing is marked by us as an anniversary to remember our fallen war dead. It was a bloody, futile disaster where too many young men were sacrificed on both Allied and Turkish sides. I had only heard the history of the invaders rather than the invaded. De Bernieres takes the reader into the trenches, to the stink and cold and heat and ordure as well as the pointlessness and brutality.

Having survived the Great War, the Greeks and Turks then embarked on the War of Independence which marked the demise of the Ottoman Empire and the birth of modern Turkey. Millions were killed in a cruel conflict which only fuelled continuing enmity - the never-ending need to avenge and gain retribution for depravities and slaughters that both sides perpetrated. The solution to determine 'peace' was a partition: Greek Christians (who had been born and bred in Turkey) were uprooted and sent to Greece while the Turkish Muslims living in Greece were sent to Turkey. The sorrow and bewilderment of these displaced persons is once again portrayed by De Bernieres in the depiction of the townsfolk who become the pawns of these two warring countries.

I recently visited Turkey where I visited one of the 'ghost towns' where Greek Christians were removed. It was a poignant experience as I wandered through the ruins where weeds flourished and goats grazed, and an owl had made its nest in the rafters of the empty Coptic church.

Birds Without Wings was often hard going due to the density of the writing and the sheer scale of the history it described but the language is beautiful and the journey worth it due to the sympathy I felt for the wonderful cast of characters in the little town of Eskibahce.

Published on April 27, 2012 03:21

March 27, 2012

The Realm of The Dead: Afterlife in the Ancient World

Suzanne Adair, author of Camp Follower and many other novels has featured this guest post in Relevant History on her blog The British are Coming Y'all.

Suzanne Adair, author of Camp Follower and many other novels has featured this guest post in Relevant History on her blog The British are Coming Y'all. The ancient Greeks believed in an underworld to which the souls of the dead journeyed. It was known by names such as Hades or Erebus which have become synonymous with the concept of 'Hell'. The Underworld was a structured place. The souls of the dead were sent to various realms based on how they were judged: blameless heroes to Elysium, the evil to Tartarus and those who were neither good nor bad to the Fields of Asphodel. To safely travel from the world of the living to that of Hades, the soul needed to cross the Styx (the River of Hate) on a boat steered by a grim ferryman known as Charon. The cost of the trip was a gold coin and it was the custom of mourners to place one in the deceased's mouth to ensure safe passage.

Although the Romans came to adopt a belief in Hades in imperial times, the religion of early Rome did not envisage that an individual would experience an afterlife. Instead it was believed that the souls of the dead joined an amorphous mass of spirits known as the Dii Manes or the 'Kindly Ones'. The name is ironic because these spirits were considered fearful and needed to be placated by the relatives of the deceased in case they rose to torment them. Calling them a flattering name was therefore an attempt at appeasement.

Of course a belief in an afterlife is common to many ancient societies. My research revealed another civilisation existing in Italy from archaic times with a complex codex which provided guidance on how a person could live forever. That civilisation was Etruria and its people were known as the Etruscans.

The Etruscans were a race that lived in the area of Tuscany, Umbria and Lazio but whose influence spread from the Po Valley in the north to Campania in the south. They were the sworn enemies of the Romans whose fledging republic was still scrapping with its Latin neighbours while the Etruscans were establishing a trade empire across the Mediterranean. Indeed, the Romans were as austere and insular as the Etruscans were sophisticated and cosmopolitan.

Although recent archaeological digs are revealing more about the Etruscans, they have often been dubbed 'mysterious' because none of their literature has survived other than remnants of ritual texts. Most of what we know about them is from Greek or Roman historians (their enemies) who wrote centuries after Etruria had been destroyed. However, we can gain a glimpse of their own perspective through their fantastic tomb art which also serves as a rich vein of inspiration for episodes within my books. In fact a good deal of what is known about Etruscan architecture and daily life comes from their incredibly ornate tombs which replicated the houses of the living with their lintels and doorframes, tables and couches—even clothes hanging from hooks on the walls. Treasure was also included together with all the necessities to ensure a comfortable life such as plates and utensils and food, and a host of slave statuettes to serve the spirits of the dead.

From this funerary art it is apparent that the Etruscan's afterlife was not so much an underworld as an 'Afterworld' or 'Beyond'. In this realm, the character of Charon also appears. He is known as 'Charun' and is a gatekeeper rather than a ferry man. The dead were also met at the entrance to the Beyond by a winged demoness named Vanth. One tomb painting depicts her as wearing a tiny pleated skirt, short hunting boots and a baldric crossing bare breasts. An eye is painted upon each arch of her wings. The two snakes twisting around her hint at her potential menace should she deny assistance to the traveller. She is often portrayed as holding a key and a torch to guide the dead. In one tomb she is shown holding a scroll of names which suggests there may have been some form of judgment day as was the case in Hades.

The souls of the Etruscan dead faced a perilous journey over land and sea where monsters and other demons lurked. The fiercest of these was the winged Tuchulcha with its donkey's ears, vulture's beak, grey-blue rotting flesh and two spotted snakes coiled around its arms. And the final destination should such terrors be overcome? A sumptuous banquet with their ancestors.The fear that the soul might fall prey to such dangers led the Etruscans to perform rigorous rituals and sacrifices to enable them to transform into lesser gods known as Dii Animales. Achieving such a status ensured their place at the banquet and possibly gave them the chance to return to receive ritual honours and assist their descendants.

The belief that blood sacrifice was necessary to placate the anger of the dead and to protect their souls in the transition to the afterlife led to dark practices. In the 'Phersu' game a masked man would set a slavering hound onto a hooded prisoner to rip the victim apart. This type of human sacrifice was later adopted by the Romans in lavish gladiatorial games held to celebrate the funerals of the powerful.

The heroine of The Wedding Shroud is a young Roman girl, Caecilia, who is married to an Etruscan nobleman to seal a truce between their warring cities. The lure of obtaining immortality in the afterlife tempts her to question her own people's belief in the bleak world of the Kindly Ones. In time, though, Caecilia comes to realise there is a price to be paid to obtain salvation. This dilemma is only one of the conflicting moralities and beliefs with which she must struggle when determining whether her future lies with Rome or Etruria.

As for the philosophy of an afterlife it is interesting to consider that modern man, whether religious or sceptical, still questions what lies beyond the grave and whether judgment awaits there.

The image is of Charun, the demon whom the Etruscans believed awaited those who entered the Beyond after death. It is only one of the demons depicted in scenes of the Afterlife within the Francois Tomb in Vulci, Italy.

Published on March 27, 2012 17:47

January 15, 2012

Pomegranates and Silphium: Fertility Control in the Ancient World

[image error]

Tracy Falbe, author of The Rhys Chronicles Series, has featured this guest post on her blog, Her Ladyship's Quest

Childbirth is dangerous. The Western world often forgets this. The advances made in medicine and mothercraft to improve the mortality rates of both mother and babies have been remarkable but are now taken for granted. So too the use of effective forms of contraception. Many forget that the development of the 'Pill' only occurred in the 1960s. And it can be argued that the introduction of oral contraceptives gave impetus to the feminist movement as women were at last given the opportunity to plan their pregnancies as well as their careers.

Women of the ancient world did not have access to such sophisticated medicine, instead they relied on more humble forms of contraception. I was absorbed when researching the methods that were used in classical Greece, Rome and Etruria when writing my novel, The Wedding Shroud.

My protagonist is a young, innocent Roman girl who is married to an Etruscan man to seal a truce between two warring cities. Caecilia discovers her husband's society offers independence, education and sexual freedom to women. Such freedoms, however, do not excuse her from the duty of bearing children. In her quest to delay this destiny she learns that there are two plants that can offer her a chance to avoid falling with child: pomegranate and silphium.

Pomegranates were associated with the myth of Persephone and the vegetation cycle. Persephone was the child of Zeus and Demeter, the goddess of the harvest. When Hades, God of the Underworld, abducted her daughter, Demeter was so grief stricken she left the earth barren. Zeus intervened and demanded Hades release Persephone. Hades grudgingly agreed but before the maiden left his realm she ate part of a pomegranate, the fruit of the underworld. As a result Persephone was bound to return to her husband for one third of the year. And so, during those months of winter, Demeter refused anything to grow.

Ancient physicians such as Hippocrates, Soranus and Dioscorides prescribed the seeds and rind of the pomegranate to prevent conception but details of the preparation or the quantities used are unknown. There is mention of the fruit being eaten while some sources state that the seed pulp was used on pessaries. It is uncertain, though, whether this was for contraceptive or abortive purposes. Strangely enough, in the Etruscan wedding ceremony the bride holds a pomegranate as a symbol of fecundity. It is ironic that the same image could also signify the potential for a woman to prevent pregnancy.

Although the efficacy of pomegranates is inconclusive (there is mention of studies showing reduced fertility in rats and guinea pigs after ingesting the fruit) there is another plant that may have been more effective - silphium.

Silphium was a member of the giant fennel family. The plant was rare, growing in the dry climate of northern Africa (modern Libya). The pungent resin from silphium's stems and roots was known as laserpicium and was used as an additive which gave food a rich distinctive taste. It was also used to treat coughs, sore throats and fevers. More importantly it was used as a contraceptive.

The crop became the main commodity of Cyrene, a city colonized by the Greeks in C7th BCE. The wealth brought from exporting silphium to the rest of the ancient world led Cyrene to recognize its importance by stamping its coins with an image of the plant. One coin even depicted a woman touching the plant and pointing to her womb.

Silphium must have been relatively effective because it became extinct presumably because demand outstripped supply. Another member of the fennel family, asafoetida, was then cultivated although it was less effective. ( It was also cheaper.) This plant has survived and gives Worcestershire sauce its characteristic flavour.

Soranus recommended women use about a chick pea's size of silphium juice dissolved in water once a month. It is clear that he also considered it had abortive effects, as did Dioscorides.

Modern testing of asafoetida and other plants from its genus has established they have notable anti-fertility effects.

There was a veritable pharmacopia of other plants used by women of the ancient world too: wild carrot, rue and penny royal to name a few. Cedar resin plugs were another method.

The effectiveness of all these natural remedies were far from effective as can be evidenced by the fact that the average life expectancy of women of the iron age was approximately 27-30 years of age. The mortality rate was high due to both maternal and infant deaths in childbirth. And we cannot forget, either, the barbarous act of killing girl children.

The image is that of Persephone holding a pomegranate as painted by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (12 May 1828 – 9 April 1882) who founded the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in 1848 with William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais.

For more information on fertility control in the ancient world, I recommend reading John M Riddle's Eve's Herbs: A History of Contraception and Abortion in the West.

Tracy Falbe, author of The Rhys Chronicles Series, has featured this guest post on her blog, Her Ladyship's Quest

Childbirth is dangerous. The Western world often forgets this. The advances made in medicine and mothercraft to improve the mortality rates of both mother and babies have been remarkable but are now taken for granted. So too the use of effective forms of contraception. Many forget that the development of the 'Pill' only occurred in the 1960s. And it can be argued that the introduction of oral contraceptives gave impetus to the feminist movement as women were at last given the opportunity to plan their pregnancies as well as their careers.

Women of the ancient world did not have access to such sophisticated medicine, instead they relied on more humble forms of contraception. I was absorbed when researching the methods that were used in classical Greece, Rome and Etruria when writing my novel, The Wedding Shroud.

My protagonist is a young, innocent Roman girl who is married to an Etruscan man to seal a truce between two warring cities. Caecilia discovers her husband's society offers independence, education and sexual freedom to women. Such freedoms, however, do not excuse her from the duty of bearing children. In her quest to delay this destiny she learns that there are two plants that can offer her a chance to avoid falling with child: pomegranate and silphium.

Pomegranates were associated with the myth of Persephone and the vegetation cycle. Persephone was the child of Zeus and Demeter, the goddess of the harvest. When Hades, God of the Underworld, abducted her daughter, Demeter was so grief stricken she left the earth barren. Zeus intervened and demanded Hades release Persephone. Hades grudgingly agreed but before the maiden left his realm she ate part of a pomegranate, the fruit of the underworld. As a result Persephone was bound to return to her husband for one third of the year. And so, during those months of winter, Demeter refused anything to grow.

Ancient physicians such as Hippocrates, Soranus and Dioscorides prescribed the seeds and rind of the pomegranate to prevent conception but details of the preparation or the quantities used are unknown. There is mention of the fruit being eaten while some sources state that the seed pulp was used on pessaries. It is uncertain, though, whether this was for contraceptive or abortive purposes. Strangely enough, in the Etruscan wedding ceremony the bride holds a pomegranate as a symbol of fecundity. It is ironic that the same image could also signify the potential for a woman to prevent pregnancy.

Although the efficacy of pomegranates is inconclusive (there is mention of studies showing reduced fertility in rats and guinea pigs after ingesting the fruit) there is another plant that may have been more effective - silphium.

Silphium was a member of the giant fennel family. The plant was rare, growing in the dry climate of northern Africa (modern Libya). The pungent resin from silphium's stems and roots was known as laserpicium and was used as an additive which gave food a rich distinctive taste. It was also used to treat coughs, sore throats and fevers. More importantly it was used as a contraceptive.

The crop became the main commodity of Cyrene, a city colonized by the Greeks in C7th BCE. The wealth brought from exporting silphium to the rest of the ancient world led Cyrene to recognize its importance by stamping its coins with an image of the plant. One coin even depicted a woman touching the plant and pointing to her womb.

Silphium must have been relatively effective because it became extinct presumably because demand outstripped supply. Another member of the fennel family, asafoetida, was then cultivated although it was less effective. ( It was also cheaper.) This plant has survived and gives Worcestershire sauce its characteristic flavour.

Soranus recommended women use about a chick pea's size of silphium juice dissolved in water once a month. It is clear that he also considered it had abortive effects, as did Dioscorides.

Modern testing of asafoetida and other plants from its genus has established they have notable anti-fertility effects.

There was a veritable pharmacopia of other plants used by women of the ancient world too: wild carrot, rue and penny royal to name a few. Cedar resin plugs were another method.

The effectiveness of all these natural remedies were far from effective as can be evidenced by the fact that the average life expectancy of women of the iron age was approximately 27-30 years of age. The mortality rate was high due to both maternal and infant deaths in childbirth. And we cannot forget, either, the barbarous act of killing girl children.

The image is that of Persephone holding a pomegranate as painted by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (12 May 1828 – 9 April 1882) who founded the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in 1848 with William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais.

For more information on fertility control in the ancient world, I recommend reading John M Riddle's Eve's Herbs: A History of Contraception and Abortion in the West.

Published on January 15, 2012 14:56

December 30, 2011

'Handwritten' - A Treasure Trove

Over the Christmas break I had the chance to attend the 'Handwritten' exhibition at the Australian National Library. What a mind blowing experience!

This extraordinary exhibition features 100 unique manuscripts from the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin (Berlin State Library). There are letters and manuscripts dating from the past 10 centuries written by the lions of literature, religion, science, music, exploration and philosophy.

Where do I start?

The vividness of the inks and gold leaf of biblical illuminations painted 1000 years ago were amazing. And the precision of the perfectly aligned script was testament to the austerity, discipline and devotion of the monks who must have laboured over such masterpieces.

Here was Dante's Divine Comedy before me, separated only by a sheet of glass. And more - documents written by Galileo, Goethe, Dickens, Newton, Michelangelo (a receipt for services rendered), Machiavelli and Napoleon all in a row to be inspected in the hushed atmosphere and low light of the library. In a way it was lucky that most of the documents were not in English otherwise I would have had other visitors getting irritated at me hogging the exhibit space! Even so I still managed to linger over a few: a letter from the explorer Livingstone speaking of his desire to return into the dark interior of Africa, one from James Cook describing the suitability of a ship for voyaging, and Albert Einstein expressing his concern that his science should be used for peace.

What struck me most was the neatness of the writing of the earliest examples. These men took care with their words and were practised in perfecting communication. The initial greetings were always gracious even when the content was to dispute or reason with their correspondents. However, it seemed to me that as the exhibition moved into examples from more recent times, the authors' handwriting became less mannered, even careless, hinting at the personality of the writer based on the size or formation of their letters or their less uniform style .

Then there were the musical scores. These were beautifully presented with the relevant composition playing as you examined the notations. Beethoven's 5th Symphony lay in front of my eyes. The bars of tiny black minims, crotchets and quavers dancing across the page. More poignant, though, was the little notebook he used when his deafness prevented him from understanding those around him. On one page his doctor wrote questions ruled off by pencil lines. Beethoven's responses are lost to us as he did not reply in writing. The one sided conversation piqued my curiosity as well as my sympathy.

And my favourite? A letter from Heinrich Schliemann protesting the authenticity of his discovery of Priam's treasure at Troy. As I have researched this archoelogist's (and entrepeneur's) life for one of my novels, I was intrigued to see first hand evidence of his defence of the find.

There were more, of course: Curie, Darwin, Kaftka, Dostoyevsky, Haydn, Kant, Marx, Nietzsche, Nightingale, Nobel, Pasteur and Watt …too many to rave about. Why not go and take a look yourself if you have the chance. http://www.nla.gov.au/node/2314

And what of the writers, philosophers and inventors of today? With the advance of technology and its varied media will future generations be able to view such a treasure trove? Can the Word Document and PDF of modern times provide the same allure? Somehow the sterility of typeface can't compare with handwriting. Many of the documents in the exhibit were in a foreign language and yet the character of the author shone through in ink and paper without any need for translation. The printed page alone could provide no such clues.

I usually handwrite a first draft before moulding and editing a chapter on the screen. I find ideas flow when putting pen to paper but with my atrocious writing and the ease of typing, cutting and pasting there is no way I could present a polished version without my trusty computer. And I am a strong advocate for email and Facebook being methods of communication as valid as any handwritten letter. Yet the sight of all those manuscripts has made me ponder, and even lament, the prospect of a future where children are no longer taught longhand and all letters are seen as some oddity of the past.

Published on December 30, 2011 04:04