Edward Feser's Blog, page 85

January 16, 2015

2015 Aquinas Workshop

Mount Saint Mary College in Newburgh, NY will be hosting the Fifth Annual Philosophy Workshop on the theme “Aquinas and the Philosophy of Nature” from June 4-7. The speakers will be William Carroll, Fr. James Brent, Alfred Freddoso, Michael Gorman, Jennifer Frey, Edward Feser, Candace Vogler, John O’Callaghan, and Fr. Michael Dodds. More information here.

Mount Saint Mary College in Newburgh, NY will be hosting the Fifth Annual Philosophy Workshop on the theme “Aquinas and the Philosophy of Nature” from June 4-7. The speakers will be William Carroll, Fr. James Brent, Alfred Freddoso, Michael Gorman, Jennifer Frey, Edward Feser, Candace Vogler, John O’Callaghan, and Fr. Michael Dodds. More information here.

Published on January 16, 2015 09:51

January 11, 2015

Post-intentional depression

A reader asks me to comment on novelist Scott Bakker’s recent Scientia Salon article “Back to Square One: toward a post-intentional future.” “Intentional” is a reference to intentionality, the philosopher’s technical term for the meaningfulness or “aboutness” of our thoughts -- the way they are “directed toward,” “point to,” or are about something. A “post-intentional” future is one in which we’ve given up trying to explain intentionality in scientific terms and instead abandon it altogether in favor of radically re-describing human nature exclusively in terms drawn from neuroscience, physics, chemistry, and the like. In short, it is a future in which we embrace the eliminative materialist position associated with philosophers like Alex Rosenberg and Paul and Patricia Churchland.Bakker acknowledges that since giving up on intentionality entails giving up the mind, indeed the self, the consequences of eliminativism seem dire:

A reader asks me to comment on novelist Scott Bakker’s recent Scientia Salon article “Back to Square One: toward a post-intentional future.” “Intentional” is a reference to intentionality, the philosopher’s technical term for the meaningfulness or “aboutness” of our thoughts -- the way they are “directed toward,” “point to,” or are about something. A “post-intentional” future is one in which we’ve given up trying to explain intentionality in scientific terms and instead abandon it altogether in favor of radically re-describing human nature exclusively in terms drawn from neuroscience, physics, chemistry, and the like. In short, it is a future in which we embrace the eliminative materialist position associated with philosophers like Alex Rosenberg and Paul and Patricia Churchland.Bakker acknowledges that since giving up on intentionality entails giving up the mind, indeed the self, the consequences of eliminativism seem dire:You could say the scientific overthrow of our traditional theoretical understanding of ourselves amounts to a kind of doomsday, the extinction of the humanity we have historically taken ourselves to be. Billions of “selves,” if not people, would die -- at least for the purposes of theoretical knowledge!

Here, as Bakker notes, he is echoing Jerry Fodor, who in Psychosemantics wrote:

[I]f commonsense intentional psychology really were to collapse, that would be, beyond comparison, the greatest intellectual catastrophe in the history of our species; if we’re that wrong about the mind, then that’s the wrongest we’ve ever been about anything. The collapse of the supernatural, for example, didn’t compare; theism never came close to being as intimately involved in our thought and our practice -- especially our practice -- as belief/desire explanation is… We’ll be in deep, deep trouble if we have to give it up.

I’m dubious, in fact, that we can give it up; that our intellects are so constituted that doing without it (I mean really doing without it; not just philosophical loose talk) is a biologically viable option. But be of good cheer; everything is going to be all right. (p. xii)

Fodor’s certainly correct, both about the consequences of eliminativism, and about everything’s nevertheless being all right. Or at least, everything’s going to be all right for commonsense intentional psychology; for scientism and materialism, not so much. For we cannot possibly be wrong about commonsense intentional psychology. We know that eliminativism must be false. We needn’t worry about suffering post-intentional depression because there’s no such thing as our ever being post-intentional. But scientism and materialism really do entail eliminativism or post-intentionalism. Hence they must be false too.

This is, of course, ground I’ve covered in great detail in several places. There is, for example, the very thorough critique I’ve given of Rosenberg’s book The Atheist’s Guide to Reality and some of his other writings in a series of posts. I there show that none of the arguments for eliminativism is any good, and that eliminativism cannot solve the incoherence problem -- the problem of finding a way to deny the existence of intentionality without implicitly presupposing the existence of intentionality.

Bakker tells us that, though he once found the objections to eliminativism compelling, he now takes the post-intentional “worst case scenario” to be a “live possibility” worthy of exploration. It seems to me, though, that he doesn’t really say anything new by way of making eliminativism plausible, at least not in the present article. Here I want to comment on three issues raised in his essay. The first is the reason he gives for thinking that the incoherence problem facing eliminativism isn’t serious. The second is the question of why, as Bakker puts it, we are “so convinced that we are the sole exception, the one domain that can be theoretically cognized absent the prostheses of science.” The third is the question of why more people haven’t considered “what… a post-intentional future [would] look like,” a fact that “amazes” Bakker.

Still incoherent after all these years

Let’s take these in order. In footnote 3 of his article, Bakker writes:

Using intentional concepts does not entail commitment to intentionalism, any more than using capital entails a commitment to capitalism. Tu quoque arguments simply beg the question, assume the truth of the very intentional assumptions under question to argue the incoherence of questioning them. If you define your explanation into the phenomena we’re attempting to explain, then alternative explanations will appear to beg your explanation to the extent the phenomena play some functional role in the process of explanation more generally. Despite the obvious circularity of this tactic, it remains the weapon of choice for great number of intentional philosophers.

End quote. There are a couple of urban legends about the incoherence objection that eliminativists like to peddle, and Bakker essentially repeats them here. The first urban legend is the claim that to raise the incoherence objection is to accuse the eliminativist of an obvious self-contradiction, like saying “I believe that there are no beliefs.” The eliminativist then responds that the objection is as puerile as accusing a heliocentrist of self-contradiction when he says “The sun rose today at 6:59 AM.” Obviously the heliocentrist is just speaking loosely. He isn’t really saying that the sun moves relative to the earth. Similarly, when an eliminativist says at lunchtime “I believe I’ll have a ham sandwich,” he isn’t really committing himself to the existence of beliefs or the like.

But the eliminativist is attacking a straw man. Proponents of the incoherence objection are well aware that eliminativists can easily avoid saying obviously self-contradictory things like “I believe that there are no beliefs,” and can also go a long way in avoiding certain specific intentional terms like “believe,” “think,” etc. That is simply not what is at issue. What is at issue is whether an across-the-boardeliminativism is coherent, whether the eliminativist can in principle avoid all intentional notions. The proponent of the incoherence objection says that this is not possible, and that analogies with heliocentrism and the like therefore fail.

After all, the heliocentrist can easily state his position without making any explicit or implicit reference to the sun moving relative to the earth. If he needs to, he can say what he wants to say with sentences like “The sun rose today at 6:59 AM” in a more cumbersome way that makes no reference to the sun rising. Similarly (and to take Bakker’s own example) an anti-capitalist can easily describe a society in which capital does not exist (e.g. a hunter-gatherer society). But it is, to say the least, by no means clear how the eliminativist can state his position in a way that does not entail that at least some intentional notions track reality. For the eliminativist claims that commonsense intentional psychology is falseand illusory; he claims that eliminativism is evidentially supportedby or even entailed by science; he proposes alternative theories and models of human nature; and so forth. Even if the eliminativist can drop reference to “beliefs” and “thoughts,” he still typically makes use of “truth,” “falsehood,” “theory,” “model,” “implication,” “entailment,” “cognitive,” “assertion,” “evidence,” “observation,” etc. Every one of these notions is also intentional. Every one of them therefore has to be abandoned by a consistent eliminativist. (As Hilary Putnam pointed out decades ago, a consistent eliminativist has to give up “folk logic” as well as “folk psychology.”)

To compare the eliminativist to the heliocentrist who talks about the sunrise or the anti-capitalist who uses capital is, if left at that, mere hand waving. For whether these analogies are good ones is precisely what is at issue. If Bakker or any other eliminativist wants to give a serious reply to the incoherence objection, what he needs to do is to put his money where his mouth is and show us exactly how the eliminativist can do what the heliocentist or anti-capitalist can do. He needs to show us exactly how the eliminativist position can be stated in a way that makes no appeal to “truth,” “falsehood,” “theory,” “entailment,” “observation,” or anyother intentional notion. The trouble is that no eliminativist has ever done so. Even eliminativists usually don’t claim that anyone has done it. They just issue promissory notes to the effect that someday it will be done. But since whether it can be done is precisely what is at issue, this response just begs the question. (Readers who haven’t yet done so are encouraged to read Rosenberg’s paper “Eliminativism without Tears”and my three-part reply to it, here, here, and here. Rosenberg’s essay is the most serious and thorough attempt I know of to grapple with the incoherence problem. As I show, it fails dismally.)

The second urban legend Bakker perpetuates is the claim that the incoherence objection itself somehow begs the question. The way the Churchlands illustrate this purported foible of the incoherence objection is to compare the objector to someone who claims that modern biologists contradict themselves by denying the existence of élan vital. The Churchlands imagine such a person saying something like: “If élan vital didn’t exist, you wouldn’t be alive and thus wouldn’t be around to deny its existence! So you cannot coherently deny it.” As the Churchlands rightly note, this objection begs the question, since whether élan vital is required for life is precisely what is at issue. And the incoherence objection raised against the eliminativist is, the Churchlands claim, similarly question-begging.

But the parallel is completely bogus. The reason the imagined élan vitalobjection fails is that the concept of being alive and the concept of élan vital are logically independent. We can coherently describe something being alive without bringing élan vital into our description. Hence it would require argumentation to show that élan vital is necessary for life; this cannot simply be assumed. Things are very different in the case of the dispute about eliminativism. Here, what is at issue is precisely whether the relevant concepts are logically independent. In particular, what is at issue is whether the eliminativist can coherently speak of “truth,” “falsehood,” “evidence,” “observation,” “entailment,” etc. while at the same time denying that there is such a thing as intentionality. If he can give us a way of doing so, then he will have shown that the analogy with the élan vital example is a good one. But if the eliminativist does not do so, then he is the one begging the question. But, as I have just noted, eliminativists in fact have not done so. So, once again it is really the eliminativist, and not his critic, who is engaged in circular reasoning.

Another way to see how hollow Bakker’s charge of circular reasoning is is to consider some parallel cases. Take the verificationist claim that a statement is meaningful only if it is verifiable. Notoriously, this principle seems to undermine itself, since no one has been able to explain how it can be verified. Suppose a verificationist accused his critics of begging the question in raising this objection. What could possibly be the basis for such an accusation? If the verificationist had given us some account of how his own principle could be verified, and the critic simply ignored this account but still accused the principle of verifiability of being self-undermining, thenthe verificationist would have a basis for claiming that the objection begs the question. But since the verificationist has not given us such an account, any claim that his critics beg the question against him would be groundless, and their objection stands.

Similarly, if eliminativists had given us some account of how they can coherently state their position without making use of any intentional notions whatsoever, and if their critics had nevertheless simply ignored this account and raised the incoherence objection anyway, thenthe charge that the critics beg the question would have some foundation. But this is not in fact what has happened. Eliminativists have not given an account of how they can state their position without using any intentional notions at all; typically they just wave away the problem by saying that it will be solved when neuroscience has made further advances. But in the absence of such an account, the charge that those who raise the incoherence objection beg the question is groundless. (Again, Rosenberg has come closest to trying to answer the objection head on. I have not ignored this attempt but rather answered it in detail, as the posts linked to above show.)

Another parallel: “Analytical” or “logical” behaviorism holds that talk about mental states can be translated into talk about behavior or dispositions to behavior. To say that “Bob believes that it is raining” is shorthand for saying something like “Bob will say that it is raining if he is asked, is disposed to go to the closet and grab an umbrella before leaving the house, etc.” One well-known problem with this view is that no one has been able to show how talk about mental states can be entirely replaced by talk about behavior and dispositions to behavior. In the example just given, it will be true that “Bob will say that it is raining if he is asked, is disposed to go to the closet and grab an umbrella before leaving the house, etc.” only if it is also true that Bob intends to tell us what he really thinks, desires to stay dry, etc. That is to say, if we analyze the one mental state (the belief that it is raining) in terms of behavior, the behavior itself has to be analyzed in terms of further mental states (such as the intention to say what one is really thinking and the desire to stay dry), and thus the problem is only pushed back a stage. And as it turns out, if we give a behavioral analysis of the intention and desire in question, the problem just recurs again. So it looks like no successful thoroughgoing behaviorist analysis can be carried out.

Now suppose the analytical behaviorist responds: “But this objection just begs the question, since we analytical behaviorists say that such an analysis can be given!” Obviously this would be a silly objection. The critic of analytical behaviorism has given a reason to think the analysis cannot be carried out, while the analytical behaviorist has failed to show that it can be carried out. So, until the analytical behaviorist succeeds in carrying out such an analysis, his charge that his critic begs the question will be groundless.

Similarly, critics of eliminativism have given reasons for concluding that the eliminativist needs to make use of notions which presuppose intentionality, so that no coherent statement of the eliminativist position can be carried out. To rebut this charge, it will not do for the eliminativist merely to accuse his critic of begging the question. The eliminativist has to provide the analysis his critic claims cannot be provided. Merely insisting, dogmatically, that it can be provided and someday will be provided is not good enough to rebut the incoherence charge. The eliminativist has actually to show us how to do it. Until he does, he is in the same boat as the verificationist and the analytical behaviorist. (Not a good boat to be in, since verificationism and analytical behaviorism are about as dead as philosophical theories get.)

The “lump under the rug” fallacy

Bakker wonders why we are “so convinced that we are the sole exception, the one domain that can be theoretically cognized absent the prostheses of science.” After all, other aspects of the natural world have been radically re-conceived by science. So why do we tend to suppose that human nature is notsubject to such radical re-conception -- for instance, to the kind of re-conception proposed by eliminativism? Bakker’s answer is that we take ourselves to have a privileged epistemic access to ourselves that we don’t have to the rest of the world. He then suggests that we should not regard this epistemic access as privileged, but merely different.

Now, elsewhere I have noted the fallaciousness of arguments to the effect that neuroscience has shown that our self-conception is radically mistaken. For instance, in one of the posts on Rosenberg alluded to above, I respond to claims to the effect that “blindsight” phenomena and Libet’s free will experiments cast doubt on the reliability of introspection. Here I want to focus on the presuppositionof Bakker’s question, and on another kind of fallacious reasoning I’ve called attention to many times over the years. The presupposition is that science really has falsified our commonsense understanding of the rest of the world, and the fallacy behind this presupposition is what I call the “lump under the rug” fallacy.

Suppose the wood floors of your house are filthy and that the dirt is pretty evenly spread throughout the house. Suppose also that there is a rug in one of the hallways. You thoroughly sweep out one of the bedrooms and form a nice little pile of dirt at the doorway. It occurs to you that you could effectively “get rid” of this pile by sweeping it under the nearby rug in the hallway, so you do so. The lump under the rug thereby formed is barely noticeable, so you are pleased. You proceed to sweep the rest of the bedrooms, the bathroom, the kitchen, etc., and in each case you sweep the resulting piles under the same rug. When you’re done, however, the lump under the rug has become quite large and something of an eyesore. Someone asks you how you are going to get rid of it. “Easy!” you answer. “The same way I got rid of the dirt everywhere else! After all, the ‘sweep it under the rug’ method has worked everywhere else in the house. How could this little rug in the hallway be the one place where it wouldn’t work? What are the odds of that?”

This answer, of course, is completely absurd. Naturally, the same method will not work in this case, and it is precisely because it worked everywhere else that it cannot work in this case. You can get rid of dirt outside the rug by sweeping it under the rug. You cannot get of the dirt under the rug by sweeping it under the rug. You will only make a fool of yourself if you try, especially if you confidently insist that the method must work here because it has worked so well elsewhere.

Now, the “Science has explained everything else, so how could the human mind be the one exception?” move is, of course, standard scientistic and materialist shtick. But it is no less fallacious than our imagined “lump under the rug” argument.

Here’s why. Keep in mind that Descartes, Newton, and the other founders of modern science essentially stipulated that nothing that would not fit their exclusively quantitative or “mathematicized” conception of matter would be allowed to count as part of a “scientific” explanation. Now to common sense, the world is filled with irreducibly qualitativefeatures -- colors, sounds, odors, tastes, heat and cold -- and with purposes and meanings. None of this can be analyzed in quantitative terms. To be sure, you can re-define color in terms of a surface’s reflection of light of certain wavelengths, sound in terms of compression waves, heat and cold in terms of molecular motion, etc. But that doesn’t capture what common sense means by color, sound, heat, cold, etc. -- the way red looks, the way an explosion sounds, the way heat feels, etc. So, Descartes and Co. decided to treat these irreducibly qualitative features as projections of the mind. The redness we see in a “Stop” sign, as common sense understands redness, does not actually exist in the sign itself but only as the quale of our conscious visual experience of the sign; the heat we attribute to the bathwater, as common sense understands heat, does not exist in the water itself but only in the “raw feel” that the high mean molecular kinetic energy of the water causes us to experience; meanings and purposes do not exist in external material objects but only in our minds, and we project these onto the world; and so forth. Objectively there are only colorless, odorless, soundless, tasteless, meaningless particles in fields of force.

In short, the scientific method “explains everything else” in the world in something like the way the “sweep it under the rug” method gets rid of dirt -- by taking the irreducibly qualitative and teleological features of the world, which don’t fit the quantitative methods of science, and sweeping them under the rug of the mind. And just as the literal “sweep it under the rug” method generates under the rug a bigger and bigger pile of dirt which cannot in principle be gotten rid of using the “sweep it under the rug” method, so too does modern science’s method of treating irreducibly qualitative, semantic, and teleological features as mere projections of the mind generate in the mind a bigger and bigger “pile” of features which cannot be explained using the same method.

This is the reason the qualia problem, the problem of intentionality, and other philosophical problems touching on human nature are so intractable. Indeed, it is one reason many post-Cartesian philosophers have thought dualism unavoidable. If you define “material” in such a way that irreducibly qualitative, semantic, and teleological features are excluded from matter, but also say that these features exist in the mind, then you have thereby made of the mind something immaterial. Thus, Cartesian dualism was not some desperate rearguard action against the advance of modern science; on the contrary, it was the inevitable consequence of modern science (or, more precisely, the inevitable consequence of regarding modern science as giving us an exhaustive account of matter).

So, like the floor sweeper who is stuck with a “dualism” of dirt-free floors and a lump of dirt under the rug, those who suppose that the scientific picture of matter is an exhaustive picture are stuck with a dualism of, on the one hand, a material world entirely free of irreducibly qualitative, semantic, or teleological features, and on the other hand a mental realm defined by its possession of irreducibly qualitative, semantic, and teleological features. The only way to avoid this dualism would be to deny that the latter realm is real -- that is to say, to take an eliminativist position. But as I have said, there is no coherent way to take such a position. The eliminativist who insists that intentionality is an illusion -- where illusionis, of course, an intentional notion (and where no eliminativist has been able to come up with a non-intentional substitute for it) -- is like the yutz sweeping the dirt that is under the rug backunder the rug while insisting that he is thereby getting rid of the dirt under the rug.

That the modern understanding of what a scientific explanation consists in itself generates the mind-body problem and thus can hardly solve the mind-body problem has been a theme of Thomas Nagel’s work from at least the time his famous article “What is it like to be a bat?” was first published to his recent book Mind and Cosmos . As we saw in my series of posts responding to the critics of Nagel’s book, those critics mostly completely missed this fundamental point, cluelessly obsessing instead over merely secondary issues about evolution.

Like Nagel, I reject Cartesianism, and like Nagel, I think a reconsideration of Aristotelianism is the right approach to the metaphysical problems raised by modern science -- though where Nagel merely flirts with Aristotelianism, I would go the whole hog. I would say that although science gives us a correctdescription of reality, it gives us nothing close to a complete description of reality, not even of material reality. It merely abstracts those features of concrete material reality that are susceptible of investigation via its methods, especially those features susceptible of quantitative analysis. Those features of reality that are not susceptible of such investigation are going to be known by us, if at all, only via metaphysical investigation -- specifically, I would argue, via Aristotelian-Thomistic metaphysics.

Be all that as it may, in the present context it cuts absolutely no ice merely to appeal to “what science has shown” about the other, non-human aspects of reality, as a way of trying to establish the plausibility of a radically eliminativist re-conception of human nature. For the issues are metaphysical, and science only ever “shows” anything of a metaphysical nature when it has already been embedded in a larger metaphysical framework -- in the case of eliminativism, in a naturalistic metaphysical framework. But to appeal to such a framework is, from the point of view of Aristotelians and other non-naturalists, merely to beg the question.

Hands-free onanism

Bakker asks: “What would a post-intentional future look like? What could it look like?,” and he says that it “regularly amazes” him that this question hasn’t been explored in greater depth. But it really should not amaze him. After all, nobody bothers exploring in depth what a world in which round squares existed would be like. One reason for this is that there could, even in principle, be no such thing as a world where round squares existed, since the very notion is incoherent. We can’t explore the idea in depth because we can’t explore it at all.

Of course, nobody takes the idea of a round square seriously, whereas some people take eliminativism seriously. But the problem is similar. You can’t explore the idea of a post-intentional world in depth until you’ve first shown that the idea even makes sense at all. That is to say, you first have to solve the incoherence problem. And as I’ve said, nobody has done that. Of course, we can write stories in which people say things like “There is no such thing as intentionality” and in which people treat each other as if they didn’t possess mental states. But that is no more impressive than the fact that we can write stories in which people say things like “Round squares exist” and in which they attribute both straight and curved lines to the same geometrical figures. The former no more involves imagining a “post-intentional future” than the latter involves imagining a world with round squares. In both cases, all we’re really imagining is a world where people say odd things. But that’s no different, really, from the actualworld, where all sorts of people say odd things (insane people, members of strange religious sects, eliminativists, etc.).

So, though its critics might be tempted to write off the project of imagining a post-intentional future as just so much “mental masturbation,”it really doesn’t even rise to that level. After all, there’s no such thing as paralytic onanism -- onanism of the literal sort, that is -- since paralysis rules out the anatomical preconditions of onanism. Similarly, onanism of the mental sort would require, as a precondition, the mental -- exactly what the eliminativist rules out. The closest he’ll ever get to imagining a post-intentional future is not through active fantasy, but rather a dreamless sleep.

Published on January 11, 2015 16:40

January 5, 2015

Best of 2014

At Catholic World Report, a panel of contributors lists the best books they read in 2014.

Scholastic Metaphysics: A Contemporary Introduction

was named by three of them: Mark Brumley, President and CEO of Ignatius Press; Christopher Morrissey, Professor of Philosophy at Redeemer Pacific College (who reviewed the book in CWR not too long ago); and Fr. James V. Schall, SJ, Professor Emeritus at Georgetown University. Very kind!2014 is over but scholastic metaphysics is forever and Scholastic Metaphysics is still available. Some other reactions to the book:

At Catholic World Report, a panel of contributors lists the best books they read in 2014.

Scholastic Metaphysics: A Contemporary Introduction

was named by three of them: Mark Brumley, President and CEO of Ignatius Press; Christopher Morrissey, Professor of Philosophy at Redeemer Pacific College (who reviewed the book in CWR not too long ago); and Fr. James V. Schall, SJ, Professor Emeritus at Georgetown University. Very kind!2014 is over but scholastic metaphysics is forever and Scholastic Metaphysics is still available. Some other reactions to the book:“Wonderful. [Feser’s] a very clear writer [and the book] tells a compelling story” Stephen Mumford, Professor of Metaphysics in the Department of Philosophy, University of Nottingham

“An excellent overview of scholastic metaphysics in the tradition of Thomas Aquinas… [and] an effective challenge to anyone who would dismiss scholastic metaphysics as irrelevant” William Carroll, Thomas Aquinas Fellow in Theology and Science at Blackfriars Hall, Oxford and member of the Faculty of Theology and Religion of the University of Oxford

“A welcome addition for those interested in bringing the concepts, terminology and presuppositions between scholastic and contemporary analytic philosophers to commensuration” Paul Symington, Associate Professor of Philosophy , Franciscan University of Steubenville, in Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews

Published on January 05, 2015 10:52

January 2, 2015

Postscript on plastic

What better way is there to start off the new year than with another blog post about plastic? You’ll recall that in a post from last year, I raised the question of why old plastic -- unlike old wood, glass, or metal -- seems invariably ugly. I argued that none of the seemingly obvious answers holds up upon closer inspection. In particular, I argued that the “artificiality” of plastic is not the reason, both because there are lots of old artificial things we don’t find ugly and because there is a sense in which plastic is not artificial.

What better way is there to start off the new year than with another blog post about plastic? You’ll recall that in a post from last year, I raised the question of why old plastic -- unlike old wood, glass, or metal -- seems invariably ugly. I argued that none of the seemingly obvious answers holds up upon closer inspection. In particular, I argued that the “artificiality” of plastic is not the reason, both because there are lots of old artificial things we don’t find ugly and because there is a sense in which plastic is not artificial.On the question of why old plastic is ugly, a novel possible answer is suggested by a passage in Donald Fagen’s book Eminent Hipsters . Fagen writes:

A lot of the malls and the condos are much nicer now than when I was a kid in postwar New Jersey, at the beginning of all that. But, like many of my generation, I’m afraid I’m still severely allergic to all that “plastic,” both the literal and the metaphorical. In third world countries, lefties associate it with the corporate world and call its agents “the Plastics.” Norman Mailer went so far (he always went so far) as to believe that the widespread displacement of natural materials by plastic was responsible for the increase in violence in America. Wood, metal, glass, wool and cotton, he said, have a sensual quality when touched. Because plastic is so unsatisfying to the senses, people are beginning to go to extremes to feel something, to connect with their bodies. We are all, Mailer thought, prisoners held in sensual isolation to the point of homicidal madness. (p. 130)

As with pretty much everything Mailer said, the only sane reaction is: “Seriously?” The idea that plastic has anything to do with an increase in the murder rate is obviously too stupid for words. However, the suggestion that plastic lacks the sensual appeal that wood, glass, etc. have might seem plausible.

But it isn’t, really. Think of small children, who are the most sensation-oriented of human beings and whose taste for plastic is pretty obvious. Some of my most vivid memories from childhood have to do with the strange appeal certain plastic toys had. There was, for example, that Fisher Price Milk Bottle set that so many kids in the late 60s and early 70s cut their teeth on. I’ll be damned if that orange bottle in particular doesn’t still look pretty good. Even adults chew on plastic all the time -- pen caps, straws, the frames of their glasses, etc.

So, once again it’s Mailer 0, Reality 1. My own suspicion is that the correct explanation of the ugliness of at least the most extreme cases of ugly old plastic -- such as the detritus that washes up on beaches -- might lie in a consideration raised in another post from last year, on technology. Recall that from the point of view of Aristotelian metaphysics, the distinction between what is “natural” and what is “artificial” is more perspicuously captured by the distinction between what has a substantial form and what has a merely accidental form. For some man-made things (e.g. new breeds of dog, plastic) are “natural” in the sense of having a substantial form, even though the usual examples of man-made things (e.g. tables, chairs, machines) have only accidental forms. And some “natural” things (e.g. a random pile of stones) have merely accidental forms, even though the usual examples of natural objects (e.g. plants, animals, water, gold) have substantial forms. (Full story, as usual, in Scholastic Metaphysics .)

Now, things having substantial forms are metaphysically more fundamental, since accidental forms presuppose substantial forms. But as I noted in the post on technology just linked to, in a high tech society, the metaphysical priority of the “natural” world (in the sense of the world of things having substantial forms or true Aristotelian “natures” or essences) is less manifest, since in everyday life in such a society, we are surrounded by objects whose raw materials are so highly processed that it is their accidental forms rather than the underlying substantial forms that “hit us in the face.” Furthermore, many of these objects consist of materials -- such as plastic -- which have substantial forms and are thus in an Aristotelian sense “natural,” but nevertheless don’t have the “feel” of being natural in the way wood or stone do, since unlike those substances, they don’t occur “in the wild.” So, in a high tech society, the forms of things we encounter in everyday life -- the order they exhibit -- can easily seem to be all of the “accidental” kind (in the technical Aristotelian sense), and in particular of the man-made kind.

Now, consider what happens when something having an accidental form but nevertheless made out of manifestly natural (in the sense of substantial-form-having) materials decays -- an old castle or wooden shack, say, or a tank rotting in Truk lagoon. The accidental forms disappear, but the underlying substantial forms only become more evident. This may be the reason they don’t seem ugly, and can even seem beautiful. For as Aquinas says, “beauty properly belongs to the nature of a formal cause.” As the relatively superficial accidental forms give way, but the very well-known to us and metaphysically deeper substantial forms of things like stone, wood, and metal become more manifest, the objects seem no less beautiful.

Contrast that with objects made out of plastic. Here the raw materials also have a substantial form, as all raw materials underlying accidental forms do. However, it is a kind of material -- and thus a kind of substantial form -- which does not occur “in the wild” but takes much human effort to bring into being. Hence it doesn’t have the feel to us of a natural kind of stuff. It is also a very protean stuff. There is no one shape, texture, or color that plastic tends to have. So, it can seem that the only form -- the only order -- a plastic object has is the kind we have imposed on it for our particular purposes. When it loses that -- as when a plastic toy becomes seriously damaged or a plastic bottle melted or a plastic plate brittle and missing pieces -- it can intuitively seem like something having no “formal cause” or principle or order at all. And thus it seems ugly.

If this explanation is right then it would seem to follow that if plastic occurred “in the wild” in the way that stone, metal, and wood do, we might tend to find decaying plastic objects no more ugly than we do decaying wood, metal, or stone objects. It would be hard to test that implication, since we just know too much about plastic ever to get it to seem like a wild kind of stuff on all fours with rocks, wood, etc. But maybe Fagen would disagree. He laments that, unlike people at the time Mailer was commenting, “the Babies seem awfully comfortable with simulation, virtuality, and Plasticulture in general” -- where by “Babies” he means the “TV Babies” born after about 1960, for whom television has been “the principal architect of their souls.” So, perhaps the Babies, or the babies of the Babies, or maybe the babies of the babies of the Babies, will eventually come to see broken old plastic the way people have always seen old stone and wood. Maybe yellowing cracked plastic lawn furniture will become a regular sight in high end antique shops, and old broken pocket calculators and telephones will become highly sought-after conversation pieces for the coffee table.

Nah…

Published on January 02, 2015 20:03

December 29, 2014

Causality, pantheism, and deism

Agere sequitur esse (“action follows being” or “activity follows existence”) is a basic principle of Scholastic metaphysics. The idea is that the way a thing acts or behaves reflects what it is. But suppose that a thing doesn’t truly act or behave at all. Would it not follow, given the principle in question, that it does not truly exist? That would be too quick. After all, a thing might be capable of acting even if it is not in fact doing so. (For example, you are capable of leaving this page and reading some other website instead, even if you do not in fact do so.) That would seem enough to ensure existence. A thing could hardly be said to have a capacity if it didn’t exist. But suppose something lacks even the capacity for acting or behaving. Would it not follow in that case that it does not truly exist?To affirm that conclusion without qualification would be to endorse what Jaegwon Kim calls Alexander’s Dictum: To be real is to have causal powers. (The dictum is named for Samuel Alexander, who gives expression to the idea in volume 2 of Space, Time, and Deity. Kim has discussed it in many places, e.g. here.)

Agere sequitur esse (“action follows being” or “activity follows existence”) is a basic principle of Scholastic metaphysics. The idea is that the way a thing acts or behaves reflects what it is. But suppose that a thing doesn’t truly act or behave at all. Would it not follow, given the principle in question, that it does not truly exist? That would be too quick. After all, a thing might be capable of acting even if it is not in fact doing so. (For example, you are capable of leaving this page and reading some other website instead, even if you do not in fact do so.) That would seem enough to ensure existence. A thing could hardly be said to have a capacity if it didn’t exist. But suppose something lacks even the capacity for acting or behaving. Would it not follow in that case that it does not truly exist?To affirm that conclusion without qualification would be to endorse what Jaegwon Kim calls Alexander’s Dictum: To be real is to have causal powers. (The dictum is named for Samuel Alexander, who gives expression to the idea in volume 2 of Space, Time, and Deity. Kim has discussed it in many places, e.g. here.) Even if one thinks this too strong -- say, on the grounds that Platonic Forms might exist but be causally inert -- one might still endorse a more restricted version of Alexander’s Dictum. One might hold, for example, that for material objects to be real, they must have causal powers. Trenton Merricks endorses something like this restricted version of Alexander’s principle in arguing for an eliminativist position vis-à-vis inanimate macrophysical objects ( Objects and Persons , p. 81). He argues that for a macrophysical object such as a baseball or a stone to be real, it must have causal powers. And yet (so he claims) it is only the microphysical parts of such purported objects -- their atoms, say (though “atoms” is for Merricks just a placeholder for whatever the appropriate micro-level objects turn out to be) -- that are really doing all the causal work. Baseballs, stones, and the like do not as such really cause anything. Hence baseballs, stones, and the like do not really exist. It is only atoms arranged baseballwise, atoms arranged stonewise, etc. that exist. (Merricks does not draw the same eliminativist conclusion about living things. At least conscious living things doin his view have causal powers over and above those of their microphysical parts, and maybe other living things do too.)

I certainly don’t agree with Merricks’ eliminativist conclusion. (See Scholastic Metaphysics , chapter 3, especially pp. 177-84. As longtime readers might have already noticed, it is, from an Aristotelian point of view, telling that even Merricks thinks that at least the divide between the non-sentient and the sentient, and perhaps between the inorganic and the organic, mark breaks in nature where explanations exclusively in terms of microphysics give out.) But in my view, the problem with his position is not his commitment to a variation on Alexander’s Dictum -- a variation I think is essentially correct.

The thesis that for a material object to be real, it must have causal powers is the key to understanding how occasionalism tends toward pantheism. Occasionalism is the view that God is not merely the First Cause -- “first” in the sense of being the source of the causal power of other, secondary causes -- but the only cause. Common sense supposes that it is the sun that melts a popsicle when you leave it on the table outside; in fact, according to occasionalism, it is God who melts popsicles, ice cubes, and the like, on the occasion when they are left in the sun. You blame fungus for the dry rot that destroyed the wall in your garage; in fact, according to occasionalism, it is God who causes dry rot, on the occasion when fungus is present. And so forth. Neither the sun, nor fungus, nor anything other than God really has any causal power, on this view. It is only God who is ever really doing anything. Thus, the activity that we attribute to material objects must really be attributed to God.

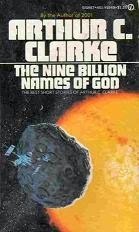

But if this is true, and if it is also true that for a material object to be real, it must have causal powers, then material objects aren’t even real. Only God is real. So, if occasionalism is true, then there is a sense in which, when you think you are observing the sun melting a popsicle, or a baseball shattering a window, or what have you, what you are really observing is just God in action, and nothing more than that. Compare Merricks’ view that what we call a baseball shattering a window is “really” nothing more than just atoms arranged baseballwise causing the scattering of atoms that had been arranged windowwise. Just as, on Merricks’ view, baseballs and windows dissolve into arrangements of atoms, so too on occasionalism the world essentially dissolves into God, which leaves us with a kind of pantheism. You might say that, given occasionalism, “the sun,” “fungus,” “stone,” “baseballs,” etc. are really just nine billion names of God (with apologies to Just to be clear, Merricks does not even discuss occasionalism and pantheism, much less defend them. But the parallel between his argument for eliminativism about inanimate macrophysical objects and occasionalism is instructive. Consider now another aspect of Merricks’ position, and a parallel with another view about God’s relation to the world. Merricks argues that if (say) a baseball played any causal role in the shattering of a window over and above the role played by its atoms, then the shattering would be “overdetermined,” insofar as the atoms alone are sufficient to bring about this effect. But we should assume that no such overdetermination exists unless we have special reason to affirm it. The baseball would be a fifth wheel, an unnecessary part of the causal story. So we should eliminate it from the story. Only the atoms are real.

Once again, I certainly don’t agree with Merricks’ eliminativist conclusion. But the problem has to do with his assumption that the microphysical level is metaphysically privileged (an assumption I criticize in Scholastic Metaphysics). We need not take issue with Merricks’ rejection of overdetermination. (Note that the issue of “overdetermination” has nothing to do with causal determinism. The idea is just that if a cause A suffices all by itself to explain an effect E, the assumption that there was some further cause B involved would make E overdetermined in the sense of having more causes than are necessary to account for it. Whether the relationship between A and E is one of deterministic causation, specifically, is not at issue.)

Now, consider deism, which in its strongest version holds that God brought the world into existence but need not conserve it in being. Any view which allows that the world could at least in principle exist apart from God’s continuous conserving action essentially makes of him something like the baseball in Merricks’ metaphysics. In Merricks’ view, the atoms that make up the purported baseball are really doing all the causal work, and the baseball is a fifth wheel that would needlessly overdetermine the atoms’ effects. Similarly, if the natural world is, metaphysically, such that it could in principle carry on apart from God’s sustaining causal activity, then God is a fifth wheel. His sustaining the world in being would be an instance of overdetermination. Hence, just as the baseball should in Merricks’ view be eliminated from the causal story, so too is God bound to drop out of the causal story given the view that the world might in principle carry on from moment to moment without him. Just as occasionalism tends toward pantheism, deism tends toward atheism. If God does everything, then everything is God; if God does nothing, then nothing is God. (Once again, Merricks himself doesn’t address any of these theological issues. I’m just using his views for purposes of comparison.)

So, the theist is well advised to steer a middle course between occasionalism and deism, and that is of course exactly what concurrentism-- defended by Aquinas and other Scholastics -- aims to do. According to concurrentism, natural objects have real, built-in causal power, but it cannot be exercised even for an instant unless God “concurs” with such exercise as a cooperating cause. Some analogies: Given its sharpness, a scalpel has a power to cut that a blunt piece of wood does not; still, unless the surgeon cooperates in its activity by pushing it against the patient’s flesh, it will not in fact cut. Given its red tint, a piece of glass has a power to cause the wall across from it to appear red; but unless light cooperates by shining through it, the glass will not in fact do so. Similarly, created or secondary causes cannot exercise their powers unless God as First Cause cooperates. Because these powers are “built into” natural objects (as the sharpness is built into the scalpel or the tint built into the glass) occasionalism is avoided. Because the powers cannot operate without divine concurrence, deism is avoided.

Not all models of God’s relationship to the world adequately convey this middle ground concurrentist position. For example, comparing God’s relationship to the world to the soul’s relationship to the body would have obviously pantheistic (or at least panentheistic) implications. As I have argued many times, thinking of the world as a kind of machine and God as a machinist is also a very bad model. Of course, the world is in some ways like a machine. For example, machines can be very complex, and the world is very complex. And God is in some ways comparable to a machinist. For example, machinists are intelligent and God is intelligent. But that does not suffice to make the machine/machinist analogy a good one, all things considered. After all, God is also in some ways comparable to a soul, and the world is in some ways comparable to a body. For example, like a soul, God is spirit rather than matter; like a body, the world is an integrated system. But the soul/body analogy is still a very bad analogy for the relationship between God and the world (at least from a classical theist point of view), and the machine/machinist analogy is also a very bad one.

As I have argued elsewhere (for example, in my Nova et Vetera article “Between Aristotle and William Paley: Aquinas’s Fifth Way”), the machine/machinist analogy has bothoccasionalist and deist implications. The deist implications are easy to see. Machines chug along automatically, and can continue to do so even if the machinist dies. Hence if the world is like a machine, it is not metaphysically necessary that there be a machinist. Naturally, “design arguments” for the existence of the machinist are at best merely probabilistic inferences. And naturally, one can, like Laplace, make the case that the machinist hypothesis is unnecessary. Whether it is or not, though, such a machinist would not be the God of classical theism, since for the classical theist the world could not even in principleexist for an instant apart from God’s conserving activity.

To see the occasionalist implications requires introducing a further concept. For many Scholastic theorists of causal powers, and for many non-Scholastics too, the notion of a causal power goes hand in hand with the notion of immanent finality. That is to say, a causal power is inherently “directed toward” some particular outcome or range of outcomes as to a final cause. To appeal to some of my stock examples, the phosphorus in the head of a match is inherently “directed toward” generating flame and heat, an acorn is inherently “directed toward” becoming an oak, and so on. If this were not the case, the fact that efficient causes exhibit the regularity they do -- the fact that their effects are typically of a specific sort rather than random -- would not be intelligible. In short, efficient causality presupposes final causality. Hence if a material thing had no inherent finality or “directedness” toward an end, it would have no inherent or “built-in” causal power either. (Once again, see Scholastic Metaphysics, especially pp. 92-105, for the full story.)

Now the “mechanical world picture” of the early moderns was more than anything else a rejection of Aristotelian immanent or “built-in” finality or teleology. There is, on this picture, no directedness or finality inherent in the material world. Any final causality or teleology we might attribute to it is really only in the mind of some observer (whether human or divine), extrinsic to the material world itself. Unsurprisingly, the early moderns also tended toward what Brian Ellis has called a “passivist” view of nature -- that is to say, a view of natural objects as passive or devoid of any intrinsic causal power. On this view, natural objects behave in the way they do not because of any intrinsic tendencies but because God has simply stipulated that they will so behave, where his stipulations are enshrined in “laws of nature.” The view of the world as a kind of artifact -- as, for example, a watch, with God as watchmaker -- is suggested by, and reinforces, this non-teleological and passivist conception of nature. Just as the time-telling function of a watch is entirely extrinsic to the bits of metal that make up a watch, so too is all teleology or finality entirely extrinsic to the natural order.

This picture of things is implicitly occasionalist. If the finality or directedness is really all in God and in no sense in the world, then (given the thesis that causal power presupposes immanent finality) causal power is really all in God and in no sense in the world. And thus the view is also implicitly pantheist. For if a material thing has no causal power, then (given the variation on Alexander’s Dictum we’ve been considering), it isn’t real. In short: No immanent finality, no causal powers; no causal powers, no material objects; so, no immanent finality, no material objects. To abandon an Aristotelian philosophy of nature is thus implicitly to abandon nature. What we taketo be nature is really just God in action. (Homework exercise: Relate this absorption of the world into God to the tendency in modern theology to absorb nature into grace.)

And so, unsurprisingly, while some of the moderns went in a deist or even atheist direction, others went in a radically anti-materialist and even pantheist direction. Hence the occasionalism and near-pantheism of Malebranche, the outright pantheism of Spinoza, the idealism of Leibniz and Berkeley, and the absolute idealism of post-Kantian philosophy.

Of course, the machine analogy is often used by people who have no deist, occasionalist, or pantheist intent -- for example, by Paley and other defenders of the “design argument,” and by contemporary “Intelligent Design” theorists. And the analogy has an obvious popular appeal, since the “God as watchmaker” model is much easier for the man on the street to understand than the Scholastic’s appeal to act and potency, essentially ordered causal series, and so forth. But metaphysicallythe analogy is superficial. Indeed, it is a theological mess. Its implications are not more widely seen because those who make use of it typically do not think them through, being satisfied if the analogy serves the apologetic needs of the moment. (As I have pointed out many times, it is the metaphysical and theological problems inherent in this analogy, rather than anything to do with evolution per se, that underlie Thomistic misgivings about ID theory.)

To reason from the world to God is to reason from natural substances to their cause. If the reasoning is to work, one had better have a sound metaphysics of causality and a sound metaphysics of substance. The machine analogy, and other views which explicitly or implicitly deny inherent causal power to natural substances, reinforce a bad metaphysics of causality and of substance.

Published on December 29, 2014 17:11

December 26, 2014

Martin and Murray on essence and existence

The real distinction between a thing’s essence and its existence is a key Thomistic metaphysical thesis, which I defend at length in

Scholastic Metaphysics

, at pp. 241-56. The thesis is crucial to Aquinas’s argument for God’s existence in De Ente et Essentia, which is the subject of an eagerly awaited forthcoming book by Gaven Kerr. (HT: Irish Thomist) One well-known argument for the distinction is that you can know thing’s essence without knowing whether or not it exists, in which case its existence must be distinct from its essence. (Again, see Scholastic Metaphysics for defense of this argument.) In his essay “How to Win Essence Back from Essentialists,” David Oderberg suggests that the argument can be run in the other direction as well: “[I]t is possible to know that a thing exists without knowing what kind of thing it is. (Such is our normal way of acquiring knowledge of the world.)” (p. 39)

The real distinction between a thing’s essence and its existence is a key Thomistic metaphysical thesis, which I defend at length in

Scholastic Metaphysics

, at pp. 241-56. The thesis is crucial to Aquinas’s argument for God’s existence in De Ente et Essentia, which is the subject of an eagerly awaited forthcoming book by Gaven Kerr. (HT: Irish Thomist) One well-known argument for the distinction is that you can know thing’s essence without knowing whether or not it exists, in which case its existence must be distinct from its essence. (Again, see Scholastic Metaphysics for defense of this argument.) In his essay “How to Win Essence Back from Essentialists,” David Oderberg suggests that the argument can be run in the other direction as well: “[I]t is possible to know that a thing exists without knowing what kind of thing it is. (Such is our normal way of acquiring knowledge of the world.)” (p. 39)Which brings to mind this old Saturday Night Liveskit with Steve Martin and Bill Murray:

(Transcript here.) An SNL skit illustrating a key theme of Thomistic metaphysics? Not so surprising given that Martin was a philosophy major and Murray is a fan of the Latin Mass.

Published on December 26, 2014 11:24

December 23, 2014

Christmastime reading for shut-ins

Just announced: The Institute for Thomistic Philosophy.

Just announced: The Institute for Thomistic Philosophy. At Public Discourse, William Carroll gives us the scoop on Thomas Aquinas in China.

At Anamnesis, Joshua Hochschild asks: What’s Wrong with Ockham?

Philosopher Roberto Mangabeira Unger and physicist Lee Smolin have just published The Singular Universe and the Reality of Time: A Proposal in Natural Philosophy . In an interview, Smolin addresses the question: Who will rescue time from the physicists?In related news, io9 reports that scientists admit that they need philosophers.

Forthcoming from Stephen Mumford and Rani Lill Anjum: What Tends to Be: Essays on the Dispositional Modality. Details trickling out via Twitter, here, here, here, and here.

Philosopher Robert Koons has a blog: The Analytic Thomist.

Mathematician and philosopher James Franklin has a page at Academia.edu. And, if you didn’t already know of it, a homepage.

At Scientia Salon, Massimo Pigliucci on Dupré, Fodor, Hacking, Cartwright, reductionism, and the disunity of the sciences.

Stephen Boulter reviews John Marenbon’s Oxford Handbook of Medieval Philosophy at Philosophy in Review.

Check out The Journal of Analytic Theology.

Roger Scruton on the shock of the new, the power of kitsch, and the meaning of conservatism.

Published on December 23, 2014 19:08

December 20, 2014

Knowing an ape from Adam

On questions about biological evolution, both the Magisterium of the Catholic Church and Thomist philosophers and theologians have tended carefully to steer a middle course. On the one hand, they have allowed that a fairly wide range of biological phenomena may in principle be susceptible of evolutionary explanation, consistent with Catholic doctrine and Thomistic metaphysics. On the other hand, they have also insisted, on philosophical and theological grounds, that not every biological phenomenon can be given an evolutionary explanation, and they refuse to issue a “blank check” to a purely naturalistic construal of evolution. Evolutionary explanations are invariably a mixture of empirical and philosophical considerations. Properly to be understood, the empirical considerations have to be situated within a sound metaphysics and philosophy of nature.For the Thomist, this will have to include the doctrine of the four causes, the principle of proportionate causality, the distinction between primary and secondary causality, and the other key notions of Aristotelian-Thomistic (A-T) metaphysics and philosophy of nature (detailed defense of which can be found in

Scholastic Metaphysics

). All of this is perfectly consistent with the empirical evidence, and those who claim otherwise are really implicitly appealing to their own alternative, naturalistic metaphysical assumptions rather than to empirical science. (Some earlier posts bringing A-T philosophical notions to bear on biological phenomena can be found here, here, here, here, and here. As longtime readers know, A-T objections to naturalism have absolutely nothing to do with “Intelligent Design” theory, and A-T philosophers are often very critical of ID. Posts on the dispute between A-T and ID can be found collected here.)

On questions about biological evolution, both the Magisterium of the Catholic Church and Thomist philosophers and theologians have tended carefully to steer a middle course. On the one hand, they have allowed that a fairly wide range of biological phenomena may in principle be susceptible of evolutionary explanation, consistent with Catholic doctrine and Thomistic metaphysics. On the other hand, they have also insisted, on philosophical and theological grounds, that not every biological phenomenon can be given an evolutionary explanation, and they refuse to issue a “blank check” to a purely naturalistic construal of evolution. Evolutionary explanations are invariably a mixture of empirical and philosophical considerations. Properly to be understood, the empirical considerations have to be situated within a sound metaphysics and philosophy of nature.For the Thomist, this will have to include the doctrine of the four causes, the principle of proportionate causality, the distinction between primary and secondary causality, and the other key notions of Aristotelian-Thomistic (A-T) metaphysics and philosophy of nature (detailed defense of which can be found in

Scholastic Metaphysics

). All of this is perfectly consistent with the empirical evidence, and those who claim otherwise are really implicitly appealing to their own alternative, naturalistic metaphysical assumptions rather than to empirical science. (Some earlier posts bringing A-T philosophical notions to bear on biological phenomena can be found here, here, here, here, and here. As longtime readers know, A-T objections to naturalism have absolutely nothing to do with “Intelligent Design” theory, and A-T philosophers are often very critical of ID. Posts on the dispute between A-T and ID can be found collected here.) On the subject of human origins, both the Magisterium and Thomist philosophers have acknowledged that an evolutionary explanation of the origin of the human body is consistent with non-negotiable theological and philosophical principles. However, since the intellect can be shown on purely philosophical grounds to be immaterial, it is impossible in principle for the intellect to have arisen through evolution. And since the intellect is the chief power of the human soul, it is therefore impossible in principle for the human soul to have arisen through evolution. Indeed, given its nature the human soul has to be specially created and infused into the body by God -- not only in the case of the first human being but with every human being. Hence the Magisterium and Thomist philosophers have held that special divine action was necessary at the beginning of the human race in order for the human soul, and thus a true human being, to have come into existence even given the supposition that the matter into which the soul was infused had arisen via evolutionary processes from non-human ancestors.

In a recent article at Crisis magazine, Prof. Dennis Bonnette correctly notes that Catholic teaching also requires that there be a single pair from whom all human beings have inherited the stain of original sin. He also rightly complains that too many Catholics wrongly suppose that this teaching can be allegorized away and the standard naturalistic story about human origins accepted wholesale.

The sober middle ground

Naturally, that raises the question of how the traditional teaching about original sin can be reconciled with what contemporary biologists have to say about human origins. I’ll return to that subject in a moment. But first, it is important to emphasize that the range of possible views consistent with Catholic teaching and A-T metaphysics is very wide, but also not indefinitely wide. Some traditionalist Catholics seem to think that the willingness of the Magisterium and of contemporary Thomist philosophers to be open to evolutionary explanations is a novelty introduced after Vatican II. That is simply not the case. Many other Catholics seem to think that Pope St. John Paul II gave carte blanche to Catholics to accept whatever claims about evolution contemporary biologists happen to make in the name of science. That is also simply not the case. The Catholic position, and the Thomist position, is the middle ground one I have been describing. It allows for a fairly wide range of debate about what kinds of evolutionary explanations might be possible and, if possible, plausible; but it also rules out, in principle, a completely naturalistic understanding of evolution.

Perhaps the best-known magisterial statement on these matters is that of Pope Pius XII in his 1950 encyclical Humani Generis. In sections 36-37 he says:

[T]he Teaching Authority of the Church does not forbid that, in conformity with the present state of human sciences and sacred theology, research and discussions, on the part of men experienced in both fields, take place with regard to the doctrine of evolution, in as far as it inquires into the origin of the human body as coming from pre-existent and living matter -- for the Catholic faith obliges us to hold that souls are immediately created by God. However, this must be done in such a way that the reasons for both opinions, that is, those favorable and those unfavorable to evolution, be weighed and judged with the necessary seriousness, moderation and measure, and provided that all are prepared to submit to the judgment of the Church…

When, however, there is question of another conjectural opinion, namely polygenism, the children of the Church by no means enjoy such liberty. For the faithful cannot embrace that opinion which maintains that either after Adam there existed on this earth true men who did not take their origin through natural generation from him as from the first parent of all, or that Adam represents a certain number of first parents. Now it is in no way apparent how such an opinion can be reconciled with that which the sources of revealed truth and the documents of the Teaching Authority of the Church propose with regard to original sin, which proceeds from a sin actually committed by an individual Adam and which, through generation, is passed on to all and is in everyone as his own.

The pope here allows for the possibility of an evolutionary explanation of the human body and also, in strong terms, rules out both any evolutionary explanation for the human soul and any denial that human beings have a single man as their common ancestor. This combination of theses was common in Thomistic philosophy and in orthodox Catholic theology at this time, and can be found in Neo-Scholastic era manuals published, with the Imprimatur, both before 1950 and in the years after Humani Generis but before Vatican II.

For example, in Celestine Bittle’s The Whole Man: Psychology, published in 1945, we find:

[T]he evolution of man’s body could, per se, have been included in the general scheme of the evolutionary process of all organisms. Evolution would be a fair working hypothesis, because it makes little difference whether God created man directly or used the indirect method of evolution…

Whatever may be the ultimate verdict of science and philosophy concerning the origin of man’s body, whether through organic evolution or through a special act of divine intervention, man’s soul is not the product of evolution. (p. 585)

George Klubertanz, in Philosophy of Human Nature(1953), writes:

Essential evolution of living things up to and including the human body (the whole man with his spiritual soul excluded…), as explained through equivocal causality, chance, and Providence, is a possible explanation of the origin of those living things. The possibility of this mode of origin can be admitted by both philosopher and theologian. (p. 425)

Klubertanz adds in a footnote:

There are some theological problems involved in such an admission; these problems do not concern us here. Suffice it to say that at least some competent theologians think these problems can be solved; at any rate, a difficulty does not of itself constitute a refutation.

At the end of two chapters analyzing the metaphysics of evolution from a Thomistic point of view, Henry Koren, in his indispensible An Introduction to the Philosophy of Animate Nature (1955), concludes:

[T]here would seem to be no philosophical objection against any theory which holds that even widely different kinds of animals (or plants) have originated from primitive organisms through the forces of matter inherent to these organisms and other material agents…

Even in the case of man there appears to be no reason why the evolution of his body from primitive organisms (and even from inanimate matter) must be considered to be philosophically impossible. Of course… man’s soul can have obtained its existence only through a direct act of creation; therefore, it is impossible for the human soul to have evolved from matter. In a certain sense, even the human body must be said to be the result of an act of creation. For the human body is made specifically human by the human soul, and the soul is created; hence as a human body, man’s body results from creation. But the question is whether the matter of his body had to be made suitable for actuation by a rational soul through God’s special intervention, or if the same result could have been achieved by the forces of nature acting as directed by God. As we have seen… there seems to be no reason why the second alternative would have to be an impossibility. (pp. 302-4)

Adolphe Tanquerey, in Volume I of A Manual of Dogmatic Theology (1959), writes:

It is de fide that our first parents in regard to body and in regard to soul were created by God: it is certain that their souls were created immediately by God; the opinion, once common, which asserts that even man’s body was formed immediately by God has now fallen into controversy…

As long as the spiritual origin of the human soul is correctly preserved, the differences of body between man and ape do not oppose the origin of the human body from animality…

The opinion which asserts that the human body has arisen from animality through the forces of evolution is not heretical, in fact in can be admitted theologically…

Thesis: The universal human race has arisen from the one first parent Adam. According to many theologians this statement is proximate to a matter of faith. (pp. 394-98)

Similarly, Ludwig Ott’s well-known Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma, in the 1960 fourth edition, states:

The soul of the first man was created immediately by God out of nothing. As regards the body, its immediate formation from inorganic stuff by God cannot be maintained with certainty. Fundamentally, the possibility exists that God breathed the spiritual soul into an organic stuff, that is, into an originally animal body…

The Encyclical “Humani generis” of Pius XII (1950) lays down that the question of the origin of the human body is open to free research by natural scientists and theologians…

Against… the view of certain modern scientists, according to which the various races are derived from several separated stems (polygenism), the Church teaches that the first human beings, Adam and Eve, are the progenitors of the whole human race (monogenism). The teaching of the unity of the human race is not, indeed, a dogma, but it is a necessary pre-supposition of the dogma of Original Sin and Redemption. (pp. 94-96)

J. F. Donceel, in Philosophical Psychology(1961), writes:

Until a hundred years ago it was traditionally held that the matter into which God for the first time infused a human soul was inorganic matter (the dust of the earth). We have now very good scientific reasons for admitting that this matter was, in reality, organic matter -- that is, the body of some apelike animal.

Aquinas held that some time during the course of pregnancy God infuses a human soul into the embryo which, until then, has been a simple animal organism, albeit endowed with human finality. The theory of evolution extends to phylogeny what Aquinas held for ontogeny.

Hence there is no philosophical difficulty against the hypothesis which asserts that the first human soul was infused by God into the body of an animal possessing an organization which was very similar to that of man. (p. 356)

You get the idea. It is in light of this tradition that we should understand what Pope John Paul II said in 1996 in a “Message to the Pontifical Academy of Sciences.” The relevant passages are as follows:

In his encyclical Humani Generis (1950), my predecessor Pius XII has already affirmed that there is no conflict between evolution and the doctrine of the faith regarding man and his vocation, provided that we do not lose sight of certain fixed points…

Today, more than a half-century after the appearance of that encyclical, some new findings lead us toward the recognition of evolution as more than an hypothesis. In fact it is remarkable that this theory has had progressively greater influence on the spirit of researchers, following a series of discoveries in different scholarly disciplines. The convergence in the results of these independent studies -- which was neither planned nor sought -- constitutes in itself a significant argument in favor of the theory…

[T]he elaboration of a theory such as that of evolution, while obedient to the need for consistency with the observed data, must also involve importing some ideas from the philosophy of nature.

And to tell the truth, rather than speaking about the theory of evolution, it is more accurate to speak of the theories of evolution. The use of the plural is required here -- in part because of the diversity of explanations regarding the mechanism of evolution, and in part because of the diversity of philosophies involved. There are materialist and reductionist theories, as well as spiritualist theories. Here the final judgment is within the competence of philosophy and, beyond that, of theology…

Pius XII underlined the essential point: if the origin of the human body comes through living matter which existed previously, the spiritual soul is created directly by God…

As a result, the theories of evolution which, because of the philosophies which inspire them, regard the spirit either as emerging from the forces of living matter, or as a simple epiphenomenon of that matter, are incompatible with the truth about man.

End quote. Some traditionalists and theological liberals alike seem to regard John Paul’s statement here as a novel concession to modernism, but it is nothing of the kind. The remark that evolution is “more than an hypothesis” certainly expresses more confidence in the theory than Pius had, but both Pius’s and John Paul’s judgments on that particular issue are merely prudential judgments about the weight of the empirical evidence. At the level of principle there is no difference between them. Both popes affirm that the human body may have arisen via evolution, both affirm that the human soul did not so arise, and both refuse to accept the metaphysical naturalist’s understanding of evolution. John Paul II is especially clear on this last point. As you would expect from a Thomist, he rightly insists that evolutionary explanations are never purely empirical but all presuppose alternative background metaphysical assumptions. Hence he notes that a fully worked out theory of evolution “must also involve importing some ideas from the philosophy of nature” and that here “the final judgment is within the competence of philosophy and, beyond that, of theology” -- not empirical science per se. And as Bonnette notes, the Catechism issued under Pope John Paul II essentially reaffirms, in the relevant sections (396-406), the traditional teaching that the human race inherited the stain of original sin from one man.

Neither those conservative Catholics who would in principle rule out any evolutionary aspect to human origins, nor those liberal Catholics who would rule out submitting the claims made by contemporary evolutionary biologists to any philosophical or theological criticism, can find support in the teaching of either of these popes.

Monogenism or polygenism?

But again, how can the doctrine of original sin be reconciled with what contemporary biology says about human origins? For the doctrine requires descent from a single original ancestor, whereas contemporary biologists hold that the genetic evidence indicates that modern humans descended from a population of at least several thousand individuals.