Edward Feser's Blog, page 88

September 6, 2014

Marmodoro on PSR and PC

Philosopher Anna Marmodoro is an important contributor to the current debate within metaphysics over powers and dispositions, and editor of the recommended

The Metaphysics of Powers

. Recently, at Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews, she reviewed Rafael Hüntelmann and Johannes Hattler’s anthology

New Scholasticism Meets Analytic Philosophy

, in which my paper “The Scholastic Principle of Causality and the Rationalist Principle of Sufficient Reason” appears. What follows is a response to her remarks about the paper.My paper is essentially a set of excerpts from chapter 2 of

Scholastic Metaphysics

. The principle of causality (PC), in what I take to be its core formulation, says that a potency can be actualized only by some already actual cause. (In the paper, and at greater length in the book, I discuss how other formulations follow from this one.) Marmodoro focuses on a section of the paper in which I discuss how a Scholastic might (as some Neo-Scholastic writers did) argue for PC on the basis of the principle of sufficient reason (PSR). Marmodoro quotes a passage from the paper where I summarize this sort of argument as follows:

Philosopher Anna Marmodoro is an important contributor to the current debate within metaphysics over powers and dispositions, and editor of the recommended

The Metaphysics of Powers

. Recently, at Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews, she reviewed Rafael Hüntelmann and Johannes Hattler’s anthology

New Scholasticism Meets Analytic Philosophy

, in which my paper “The Scholastic Principle of Causality and the Rationalist Principle of Sufficient Reason” appears. What follows is a response to her remarks about the paper.My paper is essentially a set of excerpts from chapter 2 of

Scholastic Metaphysics

. The principle of causality (PC), in what I take to be its core formulation, says that a potency can be actualized only by some already actual cause. (In the paper, and at greater length in the book, I discuss how other formulations follow from this one.) Marmodoro focuses on a section of the paper in which I discuss how a Scholastic might (as some Neo-Scholastic writers did) argue for PC on the basis of the principle of sufficient reason (PSR). Marmodoro quotes a passage from the paper where I summarize this sort of argument as follows:[I]f PC were false — if the actualization of a potency, the existence of a contingent thing, or something’s changing or coming into being could lack a cause — then these phenomena would not be intelligible, would lack a sufficient reason or adequate explanation. Hence if PSR is true, PC must be true.

She then comments:

Let us pause to examine the inference from PSR to PC. Is it a valid one? PSR is about what makes the world intelligible to us. It involves reasons we give in our explanations of how things are, or how they happen. But the PC is about causes, not reasons. The two sets are not co-extensive. What makes a state of affairs intelligible may be other than its causes. To show that it has to be limited to its causes would require further argument. It would be interesting to hear more from Feser about how the Scholastics could respond to this critique.

Prof. Marmodoro is in no way polemical and her questions are reasonable ones. However, they also seem to me somewhat odd ones given that, contrary to the impression that she (no doubt inadvertently) conveys, I do address these issues in the paper! The lines from me that she quoted come at the very beginning of the section on PC and PSR, and they merely introducethe topic. They are followed by eight pages of discussion, and there is also about a page and a half of additional material, earlier in the paper and before the section she focuses on, where I discuss the differences between PC and PSR. The lines Prof. Marmodoro quotes from me need to be read in light of all of this material.

One problem with Marmodoro’s remarks is that she seems to be attributing to me things I not only do not say but (as is clear from the larger context) explicitly deny. She says that “the PC is about causes, not reasons. The two sets are not co-extensive. What makes a state of affairs intelligible may be other than its causes.” But I and other Scholastic writers would agree with this. I explicitly distinguish PC and PSR in just the way she does, and I explicitly say in the article that “all causes are reasons in the sense of making the effect intelligible, but not all reasons are causes” (p. 21, emphasis added). Hence when Prof. Marmodoro goes on to say that “to show that [what makes a state of affairs intelligible] has to be limited to its causes would require further argument,” she is certainly correct, but I never said (and would not say) in the first place that what makes a state of affairs intelligible has to be limited to its causes. That is simply not what is at issue among Scholastic writers who would derive PC from PSR.

Thus when Marmodoro later cites these closing lines of my paper:

All rational inquiry, and scientific inquiry in particular, presupposes PSR. But PSR entails PC. Therefore PC cannot coherently be denied in the name of science. It must instead be regarded as part of the metaphysical framework within which all scientific results must be interpreted.

and comments that “the validity of the conclusion however depends on the entailment already questioned,” she is mistaken, because in fact I never asserted the entailment she attributes to me, and indeed would deny it.

It seems to me that what has happened here is that Prof. Marmodoro, reading in isolation the lines from my paper she initially quoted, wrongly supposes that when I say that “if the actualization of a potency, the existence of a contingent thing, or something’s changing or coming into being could lack a cause… then these phenomena would not be intelligible,” I must be conflating “being intelligible” with “having a cause” (even though I explicitly reject such a conflation elsewhere in the paper). But in fact the idea is rather this: A thing could be intelligible in itself rather than by virtue of having a cause -- for example, if it is purely actual rather than a mixture of actuality and potentiality, or if it is necessary rather than contingent. But a potency that is actualized is not purely actual, a contingent thing is not necessary, etc. Hence their source of intelligibility cannot come from their own natures but must lie in something outside them. So in the lines Marmodoro quotes from me, the claim is not that what lacks a cause is not intelligible, but rather that what lacks either a source of intelligibility within itself or a cause is not intelligible.

Another potential problem with Prof. Marmodoro’s discussion is that it might give some readers the impression that I move, hastily and without argument, from considerations about “what makes the world intelligible to us” to a claim about what it is like in itself. And of course, an objection sometimes made against Leibnizian rationalist applications of PSR is that such a move is fallacious. PSR’s demand that things be intelligible to us is (so the objection goes) not something we have reason to suppose the world actually can meet. Even if we couldn’t help but seek for explanations, it wouldn’t follow (the critic says) that they are really there.

But this is another issue I explicitly address in the paper. I discuss the ways in which the Scholastic understanding and application of PSR differs from the Leibnizian rationalist understanding and application of it. I note that PSR can be formulated without making reference to “intelligibility,” citing as an example Maritain’s formulation of PSR as the principle that whatever is, has that whereby it is. I also note that there is, in any event, a conceptual route from claims about “what makes the world intelligible to us” to claims about what it is like in itself provided by the Scholastic principle of the convertibility of the transcendentals. In particular, being and truth are on this view convertible with one another, insofar as they are the same thing considered from different points of view. Being is reality as it is in itself, whereas truth is reality as it is considered by the intellect -- that is to say, it is reality qua intelligible. If the doctrine of the transcendentals is correct, then, every kind of being is in the relevant sense true, in which case every being is intelligible, which is just what PSR says. By the same token, everything that is intelligible is a kind of being. Hence there isn’t the gap between reality’s intelligibility to a mind and what reality is like in itself that the critic of rationalist versions of PSR supposes there to be.

Obviously all of that raises various questions, but the point is that Prof. Marmodoro does not actually address the nearly ten pages worth of argument and exposition I put forward just on the topic of the relationship between PSR and PC (let alone the many other pages devoted to other questions about PC). The one argument she does raise questions about (very politely, it must be acknowledged) is one that I not only did not give, but would reject!

Anyway, interested readers can read the article themselves, or read the longer discussion in chapter 2 of Scholastic Metaphysics from which it was excerpted. And, again, I also commend to them Prof. Marmodoro’s fine anthology.

Published on September 06, 2014 00:07

September 1, 2014

Olson contra classical theism

A reader asks me to comment on this blog post by Baptist theologian Prof. Roger Olson, which pits what Olson calls “intuitive” theology against “Scholastic” theology in general and classical theism in particular, with its key notions of divine simplicity, immutability, and impassibility. Though one cannot expect more rigor from a blog post than the genre allows, Olson has presumably at least summarized what he takes to be the main considerations against classical theism. And with all due respect to the professor, these considerations are about as weak as you’d expect an appeal to intuition to be.Given his emphasis on what he claims we would come to think about the divine nature “just reading the Bible,” you might suppose that Olson’s objections are sola scriptura oriented. However, in a combox remark he says: “I didn't say it's not true just because it's not in the Bible. My argument was that it conflicts with the biblical portrayal of God…” (emphasis added). So, what arguments does Olson give to show that there is such a conflict? None that is not fallacious, as far as I can see.

A reader asks me to comment on this blog post by Baptist theologian Prof. Roger Olson, which pits what Olson calls “intuitive” theology against “Scholastic” theology in general and classical theism in particular, with its key notions of divine simplicity, immutability, and impassibility. Though one cannot expect more rigor from a blog post than the genre allows, Olson has presumably at least summarized what he takes to be the main considerations against classical theism. And with all due respect to the professor, these considerations are about as weak as you’d expect an appeal to intuition to be.Given his emphasis on what he claims we would come to think about the divine nature “just reading the Bible,” you might suppose that Olson’s objections are sola scriptura oriented. However, in a combox remark he says: “I didn't say it's not true just because it's not in the Bible. My argument was that it conflicts with the biblical portrayal of God…” (emphasis added). So, what arguments does Olson give to show that there is such a conflict? None that is not fallacious, as far as I can see.Consider Olson’s populist appeal to what the “ordinary lay Christian, just reading his or her Bible” would come to think. I certainly agree with him that the average reader without a theological education would not only not arrive at notions like divine simplicity, immutability, etc., but would even reject them. But so what? By itself this is just a fallacious appeal to majority. Moreover, Olson does not apply this standard consistently. The average reader might also suppose that God has a body -- for example, that he has legs with which he walks about the garden of Eden in the cool of the day (Genesis 3:8), eyes and eyelids (Psalm 11:4), nostrils and lungs with which he breathes (Job 4:9), and so forth. But Olson acknowledges that God does not have a body. Since Olson gives us no explanation of why we should trust what the ordinary reader would say vis-à-vis divine simplicity, etc. but not trust him where divine incorporeality is concerned, we seem to have a fallacy of special pleading.

One of Olson’s readers points out that Olson himself “repudiate[s] much of the biblical portrayal of God,” such as God’s “commanding capital punishment,” and asks how Olson can do so given his appeal to consistency with scripture. Olson’s response is: “Surely, if you've read me very much, you know the answer -- Jesus.” But of course, that is no answer at all, since whether Jesus would approve of Olson’s position (vis-à-vis capital punishment or classical theism) or that of Olson’s critic is itself part of what is at issue, so that the reply begs the question. (Olson also tells the reader -- who, quite rightly, wasn’t satisfied with Olson’s response -- that the reader intends only “to challenge and argue and harass” Olson and lacks a “teachable spirit.” What Olson does not do is actually answer the reader’s objection.)

Then there is Olson’s characterization of classical theism, which is a straw man. He accuses the classical theist of “start[ing] down the road of de-personalizing” God. But Scholastic classical theists argue that we must attribute intellect and will to God, and these are the essential personal attributes. To be sure, Olson also says that “feelings and emotions are part of being personal,” that classical theism portrays God as “unemotional,” and that “scholastic theology tends to portray the image of God as reason ruling over emotion, being apathetic.” But this is a tangle of confusions. First of all, by itself the claim that “feelings and emotions are part of being personal” just begs the question. Second, the claim that there is some connection between “reason ruling over emotion” and “being apathetic” is just a non sequitur.

Third, the claim that classical theism makes God out to be “unemotional” is ambiguous. If by an “emotion” we mean a state that comes upon us episodically, that varies in its intensity, that has physiological aspects like increased heart rate and bodily sensations, etc., then it is certainly true that the classical theist maintains that God cannot possibly have such states. However, if the insinuation is that classical theism makes God out to be “unemotional” in a way that entails that he cannot be said to love us, to be angry at sin, etc., then that is certainly false. To love is to will the good of another, and for the classical theist God certainly wills our good, acts providentially so that we attain what is good for us, etc. Hence he loves us. The classical theist also holds that God wills that sin be punished, and acts so that those who are unrepentant are in fact punished. Hence he is in that sense wrathful at sin. And so forth. Hardly “apathetic.”

Now, a response sometimes made to this (though not by Olson) is that the “intellect,” “will,” “love,” “wrath,” and the like that the classical theist attributes to God are bloodless and inferior to the thinking, willing, love, anger, etc. that human beings experience. They are (so it is claimed) like the coldly mechanical processes we might attribute to a computer. But this is based on confusion. To see how, consider the following analogies. A vine “seeks” to reach water with its roots and it “tries” to grow toward the light, but of course it does not do so in the way an animal seeks and tries to do things. There is clearly an analogy between the vine’s “seeking” and “trying” and that of the animal, but given the sentience associated with the animal’s seeking and trying, they are, equally clearly, radically different. There is also a clear analogy between the seeking and trying that non-human animals exhibit and that which human beings exhibit, but, no less clearly, the conceptual content that human beings bring to bear on the objects of their seeking and trying make what they are capable of radically different from what the animal does.

Now, given the radical differences between them, there is no way a plant can understand the nature of the “seeking” and “trying” that an animal is capable of, and no way an animal can understand the “seeking” and “trying” that a human being is capable of. But it would obviously be ridiculous for a plant to conclude (if plants could “conclude” anything in the first place) that what the animal does, given its sentience, is inferior to what the plant does. On the contrary, it is superior to what the plant does. Similarly, it would be ridiculous for a non-human animal to conclude (if non-human animals could “conclude” anything in the first place) that what human beings do, given the conceptualization they bring to bear on their acts of seeking and trying, is inferior to what the animal does. On the contrary, it is superior to what the animal does.

But by the same token, it is ridiculous for human beings to think that the divine intellect, the divine will, divine love, etc. must be inferior to ours if God is immutable, impassible, incorporeal, etc. On the contrary, they are unimaginably higher and nobler than our thinking, willing, loving, etc. precisely because they are not tied to the limits of created things. God does not have to reason through the steps of an argument or to make careful observations in order to know something; his love does not vary in intensity given alterations in blood sugar levels, the state of the nerves, over-familiarity, etc.

This does not make him like a computer, because (contrary to the muddleheaded fantasies of computationalists -- which I’ve discussed here, here, here, here, hereand elsewhere) a computer is sub-rational. It is far less than a human intellect, whereas God is far more than a human intellect. When we project our own experiences or machine metaphors onto God as conceived of by the classical theist, we are doing something like what a plant would be doing if it modeled animal sentience on what plants do or on what stones do; or like what an animal would be doing if it modeled human conceptual abilities on what animals do or what plants do. (Imagine a dog saying: “Humans ‘conceptualize’ what they perceive? That’s like what a plant does when it ‘seeks’ the light! How cold and bloodless!” That’s about as clueless as some “theistic personalist” characterizations of classical theism are.)

Hence -- to return to Olson -- when Olson writes that classical theism is “spiritually deadening” and “leaves one cold as ice with God seeming to be unfeeling and anything but relational,” he is aiming his attack at a caricature. He is also arguably committing a fallacy of appeal to emotion, since whether we feel moved by a certain view about God’s nature by itself tells us nothing about whether that view is true or whether the arguments for it are sound.

Similarly irrelevant are the character traits (or purported character traits) of those who defend classical theism. Olson claims that:

[V]irtually all theologians who portray God as unemotional are men and men are often inclined to view emotions as feminine and therefore unworthy of God. Could it be that traditional scholastic theology is infected with a tendency to justify male aversion to emotions…?

Never mind the dubious pop sociology underlying this claim. (The major theistic personalist critics of classical theism -- Plantinga, Swinburne, Hartshorne, Hasker, Basinger, Pinnock, et al. -- are also men; and the Scholastic theologians who hammered out Christian classical theism are also often accused of idolatrous devotion to a woman -- the Blessed Virgin Mary -- and of attributing near-divine authority to an institution conceived of in feminine terms, viz. Holy Mother Church. So should we conclude that theistic personalism constitutes a “boys’ club”? Should we judge the Scholastics to be proto-feminists? These suggestions are silly, but I challenge anyone to show that Olson’s suggestion is any less silly.) The more important point, of course, is that even ifclassical theists were motivated by a “male aversion to emotions,” that wouldn’t show that classical theist arguments are mistaken. To suppose otherwise would be to commit an ad hominem fallacy.

Finally, Olson fails even to consider, much less respond to, the reasons why classical theists have insisted on divine simplicity, immutability, etc. As I have explained many times elsewhere (e.g. at length here), the classical theist argues that if God is in any way composite -- if he is a mixture of actuality and potentiality, for example, or of an essence or nature together with a distinct act of existence, or a substance which instantiates various properties distinct from it -- then he will require a cause of his own, and thus fail to be the first cause of all things (contrary not only to sound philosophical theology but also to biblical revelation). But if he is capable of change or of being affected by anything outside him, then he will be a mixture of actuality and potentiality, and will thus be composite rather than simple, and will thus require a cause of his own. Etc.

Now these are, of course, reasons of the sort that have led philosophical theologians, including Christian philosophical theologians, to deny also that God can be corporeal -- a denial Olson endorses. Olson and other critics of classical theism thus owe us an explanation of why such considerations should not lead us to embrace the rest of the classical theist package, and of how their alternative “theistic personalist” position can avoid making of God a creature in just the way attributing corporeality to him would.

An appeal to what is “intuitive” does not suffice (especially not if backed with fallacious arguments). If the “intuitions” are sound, then it should be possible rationally to justify them with sound arguments -- in which case the intuitions fall away as unneeded. And if there are no good arguments in defense of the intuitions, while there are good (and certainly unanswered) arguments against them, then that is a reason to reject the intuitions rather than the classical theistic claims with which they conflict.

Published on September 01, 2014 16:25

August 26, 2014

Morrissey on Scholastic Metaphysics

At Catholic World Report, Prof. Christopher Morrissey kindly reviews my book

Scholastic Metaphysics

. From the review:

At Catholic World Report, Prof. Christopher Morrissey kindly reviews my book

Scholastic Metaphysics

. From the review:The great strength of Feser’s book is how well it exposes the shortcomings of the speculations of contemporary analytic philosophy about the fundamental structures of reality. The most recent efforts of such modern philosophical research, shows Feser, are remarkably inadequate for explaining many metaphysical puzzles raised by modern science. In order to properly understand the meaning of humanity’s latest and greatest discoveries, such as quantum field theory in modern physics, an adequate metaphysics is urgently required, now more than ever…

Feser has a notable flair for being both witty and engaging and for using entertaining and vivid examples. The book demands much from the reader’s intellectual abilities, but like reading St. Thomas Aquinas himself it is always rewarding and exhilarating. Page after page, insight after insight piles up—so many that if you have any philosophical curiosity at all, you simply cannot stop reading.

End quote. By the way, if you are not familiar with Prof. Morrissey’svarious web pages devoted to topics of interest to regular readers of this blog (such as this one, this one, this one, and this one), you should be. I have found them a very useful resource over the years.

Published on August 26, 2014 16:49

August 21, 2014

Science dorks

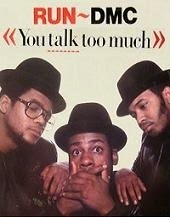

Suppose you’re trying to teach basic arithmetic to someone who has gotten it into his head that the whole subject is “unscientific,” on the grounds that it is non-empirical. With apologies to the famous Mr. Parker (pictured at left), let’s call him “Peter.” Peter’s obviously not too bright, but he thinks he is very bright since he has internet access and skims a lot of Wikipedia articles about science. Indeed, he proudly calls himself a “science dork.” Patiently, albeit through gritted teeth, you try to get him to see that two and two really do make four. Imagine it goes like this:You: OK, Peter, let’s try again. Suppose you’re in the garden and you see two worms crawling around. Then two more worms crawl over. How many worms do you have now?

Suppose you’re trying to teach basic arithmetic to someone who has gotten it into his head that the whole subject is “unscientific,” on the grounds that it is non-empirical. With apologies to the famous Mr. Parker (pictured at left), let’s call him “Peter.” Peter’s obviously not too bright, but he thinks he is very bright since he has internet access and skims a lot of Wikipedia articles about science. Indeed, he proudly calls himself a “science dork.” Patiently, albeit through gritted teeth, you try to get him to see that two and two really do make four. Imagine it goes like this:You: OK, Peter, let’s try again. Suppose you’re in the garden and you see two worms crawling around. Then two more worms crawl over. How many worms do you have now?Peter: “Crawling” means moving around on your hands and knees. Worms don’t have hands and knees, so they don’t “crawl.” They have hair-like projections called setae which make contact with the soil, and their bodies are moved by two sets of muscles, an outer layer called the circular muscles and an inner layer known as the longitudinal muscles. Alternation between these muscles causes a series of expansions and contractions of the worm’s body.

You: That’s all very impressive, but you know what I meant, Peter, and the specific way worms move around is completely irrelevant in any case. The point is that you’d have four worms.

Peter: Science is irrelevant, huh? Well, do you drive a car? Use a cell phone? Go to the doctor? Science made all that possible.

You: Yes, fine, but what does that have to do with the subject at hand? What I mean is that how worms move is irrelevant to how many worms you’d have in the example. You’d have four worms. That’s true whatever science ends up telling us about worms.

Peter: You obviously don’t know anything about science. If you divide a planarian flatworm, it will grow into two new individual flatworms. So, if that’s the kind of worm we’re talking about, then if you have two worms and then add two more, you might end up with five worms, or even more than five. So much for this a priori “arithmetic” stuff.

You: That’s a ridiculous argument! If you’ve got only two worms and add another two worms, that gives you four worms, period. That one of those worms might later go on to be divided in two doesn’t change that!

Peter: Are you denying the empirical evidence about how flatworms divide?

You: Of course not. I’m saying that that empirical evidence simply doesn’t show what you think it does.

Peter: This is well-confirmed science. What motivation could you possibly have for rejecting what we know about the planarian flatworm, apart from a desperate attempt to avoid falsification of your precious “arithmetic”?

You: Peter, I think you might need a hearing aid. I just got done saying that I don’t reject it. I’m saying that it has no bearing one way or the other on this particular question of whether two and two make four. Whether we’re counting planarian flatworms or Planters peanuts is completely irrelevant.

Peter: So arithmetic is unfalsifiable. Unlike scientific claims, for which you can give rational arguments.

You: That’s a false choice. The whole point is that argumentation of the sort that characterizes empirical science is not the only kind of rational argumentation. For example, if I can show by reductio ad absurdum that your denial of some claim of arithmetic is false, then I’ve given a rational justification of that claim.

Peter: No, because you haven’t offered any empirical evidence.

You: You’ve just blatantly begged the question! Whether all rational argumentation involves the mustering of empirical evidence is precisely what’s at issue.

Peter: So you say now. But earlier you gave the worm example as an argument for the claim that two and two make four. You appeal to empirical evidence when it suits you and then retreat into unfalsifiability when that evidence goes against you.

You: You completely misunderstand the nature of arithmetical claims. They’re not empirical claims in the same sense that claims about flatworm physiology are. But that doesn’t mean that they have no relevance to the empirical world. Given that it’s a necessary truth that two and two make four, naturally you are going to find that when you observe two worms crawl up beside two other worms, there will be four worms there. But that’s not “empirical evidence” in the sense that laboratory results are empirical evidence. It’s rather an illustration of something that is going to be the case whatever the specific empirical facts turn out to be.

Peter: See, every time I call attention to the scientific evidence that refutes your silly “arithmetic,” you claim that I “just don’t understand” it. Well, I understand it well enough. It’s all about trying to figure out flatworms and other things science tells us about, but by appealing to intuitions or word games about “necessary truth” or just making stuff up. It’s imaginary science. What we need is real, empirical science, like physics.

You: That makes no sense at all. Physics presupposes arithmetic! How the hell do you think physicists do their calculations?

Peter: Whatever. Because science. Because I @#$%&*! love science.

The Peter principle

Now, replace Peter’s references to “arithmetic” with “metaphysics” and you get the sort of New Atheist type who occasionally shows up in the comboxes here triumphantly to “refute” the argument from motion (say) with something cribbed from The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Physics. And like Peter, these critics are, despite their supreme self-confidence, in fact utterly clueless about the nature of the ideas they are attacking.

Like arithmetic, the key metaphysical ideas that underlie Aristotelian-Thomistic arguments for God’s existence -- the theory of act and potency, the principle of causality, the principle of finality, and so forth -- certainly have implications for what we observe in the empirical world, but, equally certainly, they are not going to be falsified by anything we observe in the empirical world. And like arithmetic, this in no way makes them any less rationally defensible than the claims of empirical science are. On the contrary, and once again like arithmetic, they are presupposedby any possible empirical science.

That by no means entails that empirical science is irrelevant to metaphysics and philosophy of nature. But how it is relevant must be properly understood. How we apply general metaphysical principles to various specific empirical phenomena is something to which a knowledge of physics, chemistry, biology, etc. is absolutely essential. The metaphysical facts about the essence of water specifically, or the nature of local motion specifically, or bacterial physiology specifically are not going to be determined from the armchair. But the most general metaphysical principles themselves are not matters for empirical science to settle, precisely because they concern what must be true if there is to be any empirical world, and thus any empirical science, in the first place.

Hence, consider hylemorphism. Should we think of water as a compound of substantial form and prime matter? Or should we think of it as an aggregate of substances, and thus as having a merely accidental form that configures secondary matter? The empirical facts about water are highly relevant to this sort of question. However, whether the distinctions between substantial and accidental form and prime versus secondary matter have application at all in the empirical world is not something that can possibly be settled by empirical science. In short, whether hylemorphism as a general framework is correct is a question for metaphysics and philosophy of nature, not for empirical science; but how the hylemorphic analysis gets applied to specific cases is very definitely a question for empirical science.

Or consider the principle of finality. Should we think of sublunar bodies as naturally “directed toward” movement toward the center of the earth, specifically, as Aristotle thought? Or, following Newton, should we say that there is no difference between the movements toward which sublunar and superlunar bodies are naturally “directed,” and nothing special about movement toward the center the earth specifically? The empirical facts as uncovered by physics and astronomy are highly relevant to this sort of question. However, whether there is any immanent finality or “directedness” at all in nature is not something that can possibly be settled by physical science. In short, whether the principle of finality is correct is a question for metaphysics and philosophy of nature, not for empirical science; but how that principle gets applied to specific cases is very definitely a question for empirical science.

Or consider the principle of causality, according to which any potential that is actualized is actualized by something already actual. Should we think of the local motion of a projectile as violent, or as natural insofar as it is inertial? Should we think of inertial motion as a real change, the actualization of a potential? Or should we think of it as a “state”? Howwe characterize the cause of such local motions will be deeply influenced by how we answer questions like these (which I’ve discussed in detail hereand elsewhere), and thus by physics. But whether there is some sort of cause is not something that can possibly be settled by physics. In short, whether the principle of causality is true is a question for metaphysics and philosophy of nature, not for empirical science; but how that principle gets applied to specific cases is very definitely a question for empirical science.

Why the theory of act and potency, the principle of causality, the principle of finality, hylemorphism, essentialism, etc. must be presupposed by any possible physical science, is something I have addressed many times, and at greatest length and in greatest depth in Scholastic Metaphysics . The point to emphasize for present purposes is that the arguments for God’s existence one finds in classical (Neoplatonic/Aristotelian/Scholastic) philosophy, such as Aquinas’s Five Ways, rest on general metaphysical principles like these, and not on any specific claims in physics, biology, etc. Hence when examples of natural phenomena are used in expositions of the arguments -- such as the example of a hand using a stick to move a stone, often used in expositions of the First Way -- one completely misunderstands the nature of the arguments if one raises quibbles from physics about the details of the examples, because nothing essential to the arguments rides on those details. The examples are meant merely as illustrations of deeper metaphysical principles that necessarily hold whatever the empirical details turn out to be.

For example, years ago I had an atheist reader who was obsessed with the idea that there is a slight time lag between the motion of the stick that moves the stone, and the motion of the stone itself, as if this had devastating implications for Aquinas’ First Way. This is like Peter’s supposition that the biology of planarian flatworms is relevant to evaluating whether two and two make four. It completely misses the point, completely misunderstands the nature of the issues at hand. Yet no matter how many times you explain this to certain New Atheist types, they just keep repeating the same tired, irrelevant physics trivia, like a moth that keeps banging into the window thinking it’s going to get through it next time.

Of course, often these “science dorks” don’t in fact really know all that much science. They are not, after all, really interested in science per se, but rather in what they falsely perceive to be a useful cudgel with which to beat philosophy and theology. But even when they do know some science, they don’t understandit as well as they think they do, because they don’t understand the nature of an empirical scientific claim, as opposed to a metaphysical or philosophical claim. Just as someone who not only listens to a lot of music but also knows some music theory is going to understand music better than the person who merely listens to a lot of it, so too the person who knows both philosophy and science is going to understand science better than the person who knows only science.

Vince Torley, the Science Guy

Anyway, it turns out that you needn’t be a New Atheist, or indeed even an atheist at all, to deploy the inept “Peter”-style objection. You might have another motivation -- say, if you’re an “Intelligent Design” publicist who is really, reallysteamed at some longtime Thomist critic of ID, and keen to “throw the kitchen sink” at him in the hope that something finally sticks. Case in point: our old pal Vincent Torley, whose characteristic “ready, fire, aim” style of argument we saw on display in a recent exchange over matters related to ID. In a follow-up post, Torley devotes what amounts to 15 single-spaced pages to what he evidently thinks is a massive take-down of the version of the Aristotelian argument from motion (the first of Aquinas’s Five Ways) that I presented in a talk which can be found at Vimeo. (Longtime readers will note that verbose as 15 single-spaced pages sounds for a blog post, it’s actually relatively short for the notoriously logorrheic Mr. Torley.)

Now, what does that argument have to do with ID or the other issues discussed in our recent exchange? Well, nothing, of course. But his motivation for attacking it is clear enough from some of the remarks Torley makes in the post, especially when read in light of some historical context. A quick search at Uncommon Descent (an ID site to which Torley regularly contributes, and where this new post appears) reveals that over the last four years or so, Torley has written at least fifteen (!) Torley-length posts criticizing various things I’ve said, usually about ID but sometimes about other, unrelated matters. (And no, that’s not counting the occasional positive post he’s written about me, nor is it counting critical posts written about me by other UD contributors. Nor is it counting the many lengthy comments critical of me that Torley has posted over the years in various comboxes, both here at my blog and elsewhere.) An uncharitable reader might conclude that Torley has some kind of bee in his bonnet. A charitable reader might conclude pretty much the same thing.

Now, how Torley wants to spend his time is his business, and I’m flattered by the attention. The trouble is that he always seems to think he has scored some devastating point, and gets annoyed when I don’t acknowledge or respond to it. In fact, as my longtime readers know from experience, Torley regularly just gets things wrong -- and, again, at unbelievable, mind-numbing length. (You’ll recall that the last blog post of his to which I replied alone came to 42 single-spaced pages.) There is only so much of one’s life that one can devote to reading and responding to tedious misrepresentations set out in prolix and ephemeral blog posts. As I don’t need to tell most readers, I’ve got an extremely hectic writing and teaching schedule, not to mention a wife, six children, and other family members who have a claim on my time. For some bizarre reason there is a steady stream of people who seem to think this means that I simply must have the time to respond to whatever treatise they’ve written up over the weekend, when common sense should have made it clear that this is precisely the reverse of the truth. In Torley’s case, while I did reply to some of his early responses to my criticisms of ID, in recent years I simply haven’t had the time, nor -- as his remarks have become ever more frequent, long-winded, occasionally shrill, and manifestly designed to try to get attention -- the patience either.

This evidently irks him, which brings us back to his recent remarks about my defense of a First Way-style argument. Four years ago Torley expressed the view that “Professor Feser[‘s]… ability to articulate and defend Aquinas’ Five Ways to a 21st century audience is matchless.” Three years ago he advised an atheist blogger: “I would also urge you to read Professor Edward Feser’s book, Aquinas. It’s about the best defense of Aristotelian Thomism that you are ever likely to read, it’s less than 200 pages long, and its arguments merit very serious consideration. You would be ill-advised to dismiss it out of hand.” Fast forward to the present and Torley’s attitude is mysteriously different. Nowhe assures us, in this latest post, that “the holes in Feser’s logic are sowide that anyone could drive a truck through them” and that the argument “contains so many obvious logical errors that I could not in all good conscience recommend showing it to atheists” (!)

Now, Torley is well aware that the argument I presented in the video is merely a popularized version -- presented before an audience of non-philosophers, and where I had a time limit -- of the same argument I defended in my book on Aquinas. And yet though four years ago he said that my “ability to articulate and defend” that argument is “matchless,” today he says that the “holes” in the argument are “so wide that anyone could drive a truck through them”! Three years ago he told an atheist that what I said in that book (including, surely, what I said about the First Way) is “about the best defense of Aristotelian Thomism that you are ever likely to read” and that atheists “would be ill-advised to dismiss it out of hand”; today he says he “could not in all good conscience recommend showing [Feser’s argument] to atheists”!

What has changed in the intervening years? Well, for one thing, while I am still critical of ID, I no longer bother replying to most of what Torley writes. Hence his complaint in this latest post that “Feser has yet to respond to my critique of his revamped version of Aquinas’ Fifth Way.” Evidently Torley thinks some score-settling is in order. He writes:

[I]f the argument [presented in the Vimeo talk] fails, Feser, who has ridiculed Intelligent Design proponents for years for making use of probabilistic arguments, will have to publicly eat his words… (emphasis in the original)

To be sure, Torley adds the following:

Let me state up-front that I am not claiming in this post that Aquinas’ cosmological argument is invalid; on the contrary, I consider it to be a deeply insightful argument, and I would warmly recommend Professor R. C. Koons’ paper, A New Look at the Cosmological Argument… I note, by the way, that Professor Koons is a Thomist who defends the legitimacy of Intelligent Design arguments. (emphasis in the original)

So, it isn’t the argument itself that is bad, but just my presentation of it -- even though Torley himself has praised my earlier presentations of it! Apparently, the key to giving a good First Way-style argument is this: If in your other work you “defend the legitimacy of Intelligent Design arguments,” then your take on Aquinas is to be “warmly recommended.” But if you have “ridiculed Intelligent Design proponents for years,” then even if your take on Aquinas is otherwise “matchless,” you must be made to “publicly eat your words.” It seems that for Torley, what matters at the end of the day when evaluating the work of a fellow theist is whether he is on board with ID. ID über alles. (And Torley has the nerve to accuse me of a “My way or the highway” attitude!)

Certainly it is hard otherwise to explain Torley’s shameless flouting of the principle of charity. Torley surely knows that the presentation of the argument to which he is responding is a popular version, presented before a lay audience, where I had an hour-long time limit. He knows that given those constraints I could not possibly have given a thorough presentation of the argument or answered every possible objection. He knows that I have presented the argument in a more academic style in various places, such as in Aquinas and in my ACPQ article “Existential Inertia and the Five Ways.” He knows that I have answered various objections to my version of the argument both in those writings and in a great many blog posts. Yet his method is essentially to ignore all that and focus just on what I say in the video itself.

And sure enough, in good “science dork” fashion, Torley complains that the examples I use in the talk “are marred by faulty science.” Hence, in response to my remark that a desk which holds up a cup is able to do so only because it is in turn being held up by the earth, Torley, like a central casting New Atheist combox troll, starts to channel Bill Nye the Science Guy:

How does the desk hold the coffee cup up? From a physicist’s point of view, it would be better to ask: why doesn’t the cup fall through the desk? In a nutshell, there’s a force, related to a system’s effort to get rid of potential energy, that pushes the atoms in the cup and the atoms in the desk away from each other, once they get very close together. The Earth has nothing to do with the desk’s power to act in this way…

In any case, the desk doesn’t keep the coffee cup “up,” so much as away: the atoms comprising the wood of which the desk is made keep the atoms in the cup from getting too close…

[Etc. etc.]

Well, after reading what I said above, you know what is wrong with this. And Torley should know it too, because he is a regular reader of this blog and I’ve made the same point many times (e.g. here, here, here, here, and here). The point, again, is that the scientific details of the specific examples used to illustrate the metaphysical principles underlying Thomistic arguments for God’s existence are completely irrelevant. In the case at hand, the example of the cup being held up by the desk which is in turn being held up by the earth was intended merely to introduce, for a lay audience, the technical notion of an essentially ordered series of actualizers of potentiality. Once that notion is understood, the specific example used to illustrate it drops out as inessential. The notion has application whatever the specific physical details turn out to be. When a physicist illustrates a point by asking us to imagine what we would experience if we fell into a black hole or rode on a beam of light, no one thinks it clever to respond that photons are too small to sit on or that we would be ripped apart by gravity before we made it into the black hole. Torley’s tiresomely pedantic and point-missing objection is no better.

Anyway, that’s what Torley says in the first section of his 15 single-spaced page opus. Torley writes:

For the record, I will not be retracting anything I say in this post. Professor Feser may try to accuse me of misrepresenting his argument, but readers can view the video for themselves and see that I have set it out with painstaking clarity.

…as if stubbornly refusing to listen to a potential criticism somehow inoculates him in advance against it!

Well, don’t worry Vince, I won’t be accusing you of misrepresenting me in whatever it is you have to say in the remainder of this latest post of yours. I haven’t bothered to read it.

Published on August 21, 2014 12:37

August 16, 2014

Carroll on Scholastic Metaphysics

At Public Discourse, William Carroll kindly reviewsmy book

Scholastic Metaphysics: A Contemporary Introduction

. From the review:

At Public Discourse, William Carroll kindly reviewsmy book

Scholastic Metaphysics: A Contemporary Introduction

. From the review: Edward Feser’s latest book gives readers who are familiar with analytic philosophy an excellent overview of scholastic metaphysics in the tradition of Thomas Aquinas…

Feser argues that Thomistic philosophy can expand and enrich today’s metaphysical reflection. His book is an effective challenge to anyone who would dismiss scholastic metaphysics as irrelevant.

Those familiar with Feser’s many books and lively blog will recognize his characteristic vigor and his wide-ranging reading of contemporary and medieval sources. This book is particularly aimed at those trained in the Anglo-American analytical tradition, repeatedly referencing contemporary debates in this tradition…The recovery of scholastic metaphysics depends on the recovery of that understanding of nature and substance that is central to the thought of Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas. That recovery begins, I think, by challenging the historical narrative that tells us that its loss was a necessary feature of the rise of modern science. In his new book, Edward Feser has taken a key step in this important endeavor.

End quote. Bill also has some gently critical remarks about the book. First, he says:

For readers not familiar with contemporary analytical philosophy, Feser’s book, despite its title, is not really an introduction…

That is more or less correct. The book is not a “popular” work. It is meant as an introduction to Scholastic metaphysics for those who already have some knowledge of philosophy, especially analytic philosophy. It is also meant to introduce those who are already familiar with Scholastic philosophy to what is going on in contemporary analytic metaphysics. It is not a book that would be very accessible to those who have no knowledge of philosophy. I would think that most readers who have read Aquinas or The Last Superstition should be able to handle it, though. It is, essentially, a much deeper, more systematic, book-length treatment of the metaphysical ideas and arguments sketched out in chapter 2 of Aquinasand chapter 2 of TLS.

With these aims of the book in mind, let me briefly respond to some of Bill’s other remarks. Bill rightly notes that with many modern readers “there is an a priori disposition to dismiss scholastic metaphysics as a curiosity” based on the assumption that modern science somehow put paid to Aristotelian and Thomistic philosophy once and for all. Adequately to rebut this false assumption requires in Bill’s view that we “argue against it through a historical analysis of its origins,” and that is not the sort of thing I attempt in the book.

Now in fact I do say a little bit by way of historical analysis in the book, e.g. at pp. 47-53, where I discuss how historically contingent and challengeable are the assumptions underlying Humean approaches to causation. But it is true that the book’s approach is more along the lines of the “ahistorical” weighing of ideas and arguments that is common in analytic philosophy. And that is, I think, more appropriate to the specific aims of the book. I show, many times throughout the book, how various specific purportedly science-based objections to Scholastic metaphysical claims hold no water. And of course, I also present many positive arguments for these metaphysical claims. If a critic of Scholasticism wants to refute those arguments, he needs to address them directly rather than toss out vague hand-waving references to science.

Still, I think it is true that the appeal to what the founders of modern science purportedly showed vis-à-vis Aristotelian philosophy (as opposed to Aristotelian science) has a rhetorical force for many readers that is hard to counter even with the best “ahistorical” arguments. So, a historical analysis of the sort Bill advocates is, I agree, essential. I did a bit of that in The Last Superstition, and Bill Carroll’s own work on the history of science, theology, and philosophy is, needless to say, invaluable.

Bill also says:

I also would emphasize the doctrine of creation more than Feser does. It is an important feature in scholastic metaphysics, but there is not even an entry for “creation” in the book’s index… Thomas [Aquinas] thinks that in the discipline of metaphysics one can demonstrate that all that exists has been created by God, and that without God’s ongoing causality, there would be nothing at all.

Bill is right that I do not discuss creation in the book, nor -- contrary to the impression Bill gives in a reference he makes in the review to Aquinas’s unmoved mover argument -- do I say much about natural theology at all. That was deliberate. I wanted to focus in the book on Scholastic approaches to certain “nuts and bolts” issues in metaphysics -- causal powers, essence, substance, and so forth -- that underlie everything else in Scholastic philosophy and have been the subject of renewed attention in analytic philosophy. And I wanted to make it clear that the key notions of Scholastic metaphysics are motivated and defensible entirely independently of their application to arguments in natural theology. (I have, of course, addressed questions of natural theology in several books and articles, and will do so at even greater depth in forthcoming work.)

In any event, I highly recommend Bill’s own work on the subject of creation, including Aquinas on Creation , a translation by Bill and Steven Baldner of some key texts of Aquinas on the subject, together with a long and very useful introductory essay.

Finally, Bill says:

In the beginning of the book, Feser promises to write another book on the philosophy of nature. This will be a welcome addition to his publications. Indeed, a problem that lurks behind the confusion in contemporary philosophy’s encounter with scholastic metaphysics is the loss of the sense of nature that is a characteristic starting point for Aristotle and Thomas. Feser takes up this topic in his chapter on substance, but such a discussion really ought to be conducted first in the philosophy of nature, not in metaphysics. The loss of an understanding of substance, of form and matter, and of similarly foundational ideas are all part of the larger loss of what we mean by nature.

End quote. I agree. I deliberately avoided going in detail into questions about the nature of biological substances in particular, or even chemical substances in particular, precisely because those are topics properly treated in the philosophy of nature rather than metaphysics. All the same, I did say something about these topics, and (as Bill indicates) I say a lot in the book about substance in general and about form and matter. The reason is that these are very definitely metaphysical topics as “metaphysics” is understood in contemporary analytic philosophy. And they needed to be treated at some length in a book aimed at an analytic audience; the book would have seemed oddly incomplete to many contemporary readers without such a treatment, given the other topics addressed. For “philosophy of nature” as a distinct discipline has, unfortunately, virtually disappeared in contemporary philosophy (though there are hopeful signs of a comeback), and its subject matter has been absorbed into metaphysics, philosophy of science, philosophy of biology, philosophy of chemistry, and so forth.

Here I would urge Thomists and other Scholastics always to keep in mind that the typical contemporary academic philosopher simply does not carve up the conceptual territory the way they do. What Scholastics think is covered by “metaphysics,” what they think constitutes a “science,” etc. does not correspond exactly to the way analytic philosophers think about these disciplines (though of course there is overlap). So -- as I think Bill would agree -- for the contemporary Scholastic effectively to communicate with analytic philosophers, he needs to make some concession to contemporary usage and current interests in academic philosophy. In the case of my book, that made an extended treatment of hylemorphism necessary, even though in older Scholastic works that would often have been done in the context of philosophy of nature rather than metaphysics.

Anyway, I thank Bill for his review -- and for his own work, from which I have profited much.

Published on August 16, 2014 11:53

August 12, 2014

You’re not who you think you are

If I’m not me, who the hell am I?

If I’m not me, who the hell am I? Douglas Quaid (Arnold Schwarzenegger) in Total Recall

If you know the work of Philip K. Dick, then you know that one of its major themes is the relationship between memory and personal identity. That is evident in many of the Dick stories made into movies, such as Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?(which was adapted into Blade Runner, definitely the best of the Dick film adaptations); “Paycheck” (the inferior movie adaptation of which I blogged about recently); and A Scanner Darkly(the movie version of which is pretty good -- and which I’ve been meaning to blog about forever, though I won’t be doing so here).

Then there are the short stories “We Can Remember It for You Wholesale” (the first part of which formed the basis of the original Total Recall and its pointless remake), and “Impostor”(the basis of a middling Gary Sinise movie). These two stories nicely illustrate what is wrong with the “continuity of consciousness” philosophical theories of personal identity that trace to John Locke. (Those who don’t already know these stories or movies should be warned that major spoilers follow.)What is it that makes it true that you are one and the same person as your 8-year-old self, despite the bodily and psychological changes that you have undergone since you were that age? What could make it true that someone existing after your death in heaven or hell would be one and the same person as you? Locke’s view, famously, is that neither continuity of your body nor continuity of some Cartesian immaterial substance could suffice in either case. Rather, it is in his view continuity of consciousness, and in particular memory, which does the trick. You remember, or are conscious of, having done what your 8-year-old self did, which is why you are the same person as that 8-year-old. And if someone after your death was conscious of or remembered doing what you are doing now, that person would be the same person as you, so that you could be said to have survived your death.

Butler, Reid, and others since have raised various objections to this account, and philosophers sympathetic to Locke’s basic idea have modified it in various ways to deal with these objections. But the two Dick stories in question offer scenarios which point to what I take to be the key problem with Lockean theories of personal identity.

Start with “We Can Remember It for You Wholesale.” Douglas Quail (renamed “Quaid” in the movie versions) is bored with his humdrum life and decides to visit the REKAL (pronounced “recall”) corporation, which will implant false memories of anything you want them to, make you forget you had them do it, and also plant various pieces of evidence around your house etc. to reinforce the illusion that what you think you remember really happened. Quail’s request is that REKAL implant in him memories of having been a secret agent on a trip to Mars. In the course of beginning the implantation, however, REKAL employees discover that Quail already has repressed but genuine memories of having been a secret agent on Mars -- that he really was such an agent and that his memory of being one has been imperfectly erased. Realizing that it risks getting itself involved in some matter of government intrigue, REKAL tries to disassociate itself from Quail altogether, and as his memories slowly return Quail attracts the attention of government agents, who seek to kill him in order to maintain the cover-up of the work he had been involved in while a spy.

What is of special interest for present purposes is a scene in Dick’s original story where Quail desperately begs the government agents to consider, as an alternative to killing him, a deeper memory wipe than they had attempted in their first, failed effort. Their reply is as follows:

“Turn yourself over to us. And we’ll investigate that line of possibility. If we can’t do it, however, if your authentic memories begin to crop up again as they’ve done at this time, then -- “ There was silence and then the voice finished, “We’ll have to destroy you. As you must understand. Well, Quail, do you still want to try?”

“Yes,” he said. Because the alternative was death now -- and for certain. At least this way he had a chance, slim as it was.

End quote. It isn’t clear just how thorough the proposed memory wipe is supposed to be, but Quail certainly seems willing to let it be complete if necessary. Note the stark, implicit contrast with what a Lockean theory of personal identity would lead us to expect. If Locke were correct, then for a person’s memories to be wiped away and replaced would be, in effect, for that person to go out of existence and for a new and different person to take his place. For Quail, though, such erasure and replacement is precisely a way for the original person to survive. Quail believes that he will still be Quail, that he will still exist, even if he gets a set of false memories, and that continued existence -- rather than continuity of consciousness or memory -- is what matters most to him.

Now consider “Impostor.” In this story, the protagonist (played by Sinise in the movie version) is accused of being an android duplicate of government scientist Spence Olham, sent by the Martian enemy as an infiltrator. On the run, he hopes to find a way to prove that he really isthe true Olham, as he certainly believes himself to be. And he does indeed find a way to convince his pursuers of this. It turns out, however -- as he and his pursuers discover, too late and to their horror (given what the discovery entails in the context of the story) -- that the true Olham is dead and that our protagonist really was an impostor after all. The Martian plot was so perfect that even the infiltrator himself wasn’t “in on it.”

Here the impostor remembers perfectly, or seems to anyway, being Olham, doing the things Olham did, and so forth. He, and eventually others too, are convinced that he really is Olham. He has no memories of being anyone else, nor is there anyone else who has Olham’s memories. A Lockean theory (at least if not heavily qualified in ways that have been explored by Locke’s followers) would seem to entail that he is Olham. And yet he is not. (I put to one side the question of whether a robotic duplicate could in the first place really be said to think or have even pseudo-memories the way we might -- I think a robot could not in fact be said literally to do so -- because that is irrelevant to the present point.)

You might say that what the two stories illustrate is that, contrary to the implications of Locke’s theory, you are not (without qualification, anyway) who you think you are. If Quail’s memories were completely wiped, he would no longer think he is Quail; but he would be Quail. The Olham doppelgänger thinks he is Olham; yet in fact he is not Olham. If the view implicit in Dick’s stories is correct, then who you really are can be different from who you think you are.

I think there is a sense in which this is correct. That might sound like an expression of skepticism, but it is not; quite the opposite. To see why not, consider a parallel example, that of pain and its relationship to behavior like wincing, crying out, etc. Pain and pain behavior are not the same thing, as can be seen from the fact that pain can exist in the absence of the behavior we usually associate with it, and the behavior can exist in the absence of the pain (as when someone is determined to pretend that he is in pain). Thus the behaviorist is incorrect to identify pain with dispositions to behavior of the sort in question. However, the relationship between pain and behavior is nevertheless not a contingent one, as the Cartesian might suppose. As Wittgenstein pointed out, pain behavior is normativelyassociated with pain. Pain and behavior of the sort in question are associated with one another in the standard case, even if there are aberrant cases in which they come apart.

The way a Scholastic metaphysician might put this is to say that behavior of the sort in question (wincing, crying out, etc.) is a proper accident (or “property,” in the technical Scholastic sense) of pain. A proper accident is not part of the essence of a thing, but nevertheless flows from its essence -- the stock example being the capacity for laughter, which is not part of the essence of man as a rational animal, but nevertheless flows from rational animality. Because a proper accident or property flows from the essence, things that have the essence tend to exhibit the proper accident (so that most people laugh from time to time, most dogs have four legs, etc.). But because the proper accidents or properties are distinct from the essence from which they flow, they might fail to manifest themselves if the flow is “blocked” (so that there are occasionally people who rarely if ever laugh, dogs which are missing a leg, etc.). Hence pain behavior in the normal case flows from pain in such a way that the connection between them is not merely contingent, but there can nevertheless be cases where such behavior does not manifest itself. (For discussion and defense of the Scholastic approach to essence and properties, see Scholastic Metaphysics , especially chapter 4.)

Now, in the same way, you might say that memory is something like a proper accident of personal identity (though this would have to be tightened up in a more technical presentation, since accidents are, properly speaking, accidents of substances). That is to say, in the ordinary case, B’s being the same person as an earlier person A is associated with B’s remembering doing the things A did. The connection between memory and identity, as Locke rightly sees, is not merely contingent. Still, there can be cases where the “right” memories don’t manifest themselves even though personal identity is preserved, and this is what a Lockean account misses. Just as behaviorism mistakenly identifies pain with what is really only a proper accident of pain (i.e. pain behavior), so too does Locke identify personal identity with what is really only something like a proper accident of personal identity (i.e. memory).

As to skepticism: Suppose the behaviorist argued that by identifying pain with pain behavior and other mental states with other sorts of behavior, he was solving the problem of skepticism vis-à-vis the existence of other minds. You could never doubt whether another person is in pain, or thinking about the weather, or what have you; as long as pain behavior is present, pain itself is present, since pain just is the behavior. But this would, of course, “solve” the problem of skepticism vis-à-vis other minds only by stripping pain and other mental states of what is essential to them.

Or, to take yet another example, consider Berkeley’s claim that his idealism undermines skepticism about the existence of physical objects. The skeptic says that it might be, for all we know, that there is no table there even if we all have perceptual experiences of seeing the table, feeling it, etc. Berkeley responds that since the table just is(he claims) the collection of our perceptions of it, there can be no doubt that the table is there as long as the perceptions are there. This “solves” the problem of skepticism about the existence of physical objects only by stripping physical objects of the mind-independent ontological status usually thought essential to them.

Similarly, in assimilating personal identity to memory, Locke is in effect doing something parallel to the behaviorist’s assimilation of pain to pain behavior or Berkeley’s assimilation of physical objects to our perceptions of them. And the purported response to skepticism afforded by the assimilation is as bogus in this case as it is in the others. At first glance it might seem that if you are, without qualification, whoever you think you are -- whoever you seem to remember yourself being -- then skepticism about personal identity is ruled out. If Bseems to remember doing what A did, then B is the same person as A and that is that; there would be no gap between memory and identity for the skeptic to exploit. But that would make the Martian impostor identical to the real Olham, and it would mean that the Quail who results from a complete memory wipe and replacement would not really be identical to Quail -- consequences that are as extreme and implausible as the behaviorist’s identification of pain with pain behavior and Berkeley’s identification of physical objects with our perceptions of them.

The Scholastic metaphysician’s distinction between essence and properties allows for a more nuanced and plausible account of the relationship between personal identity and memory -- a consideration which might be taken to be a further argument for that distinction.

Published on August 12, 2014 15:22

August 10, 2014

Around the web

Back from a very pleasant (but exhausting!) week in Princeton. While I regroup, some reading to wind down the summer:

Back from a very pleasant (but exhausting!) week in Princeton. While I regroup, some reading to wind down the summer: Andrew Fulford at The Calvinist International kindly reviews my book Scholastic Metaphysics . Stephen Mumford tweets a kind word about the book. Thanks, Stephen!

It’s bold. It’s new. It’s long overdue. It’s The Classical Theism Project. Check it.

At NDPR, Thomas Williams reviewsThomas Osborne’s new book Human Action in Thomas Aquinas, John Duns Scotus and William of Ockham .

Also at NDPR, David Clemenson reviews Craig Martin’s Subverting Aristotle: Religion, History, and Philosophy in Early Modern Science.Our buddy Mike Flynn on medieval science fiction. (By the way, when you click on the post, take note of the link on the left to Mike’s fine anthology Captive Dreams . I should, perhaps, have been especially keen to call attention to this book when it first came out. The reason why is the same reason why I didn’t. In his short story “Places Where the Roads Don’t Go,” Mike has a character appeal to my work in arguing with another character about AI. Very flattering, but also a little embarrassing! Thanks again, Mike!)

Speaking of science fiction, BuzzFeedconsiders why the Guardians of the Galaxysoundtrack is so shamelessly unhip it’s hip. (As Mordecai on Regular Show would say, sometimes you gotta go insane to out-sane the sane. Know what I’m sayin’?)

Edmund Burke’s influence on politics is examined at Standpoint magazine.

Is your soul Short, Tall, Grande, or Venti? James Chastek suggests a very useful analogy at the always interesting Just Thomism blog.

At another always interesting blog: The Smithy alerts us to some forthcoming books on Scotus.

Uncovering the mysteries of Steely Dan. A pseudo-interview with Becker and Fagen.

I somehow missed this one back in January. Philosopher Stephen Asma explains how teleology has risen from the grave.

Published on August 10, 2014 12:52

August 1, 2014

Haldane on Nagel and the Fifth Way

Next week I’ll be at the Thomistic Seminar organized by John Haldane. Haldane’s article “Realism, Mind, and Evolution” appeared last year in the journal Philosophical Investigations. Thomas Nagel’s book Mind and Cosmos is among the topics dealt with in the article. As Haldane notes, Nagel entertains the possibility of a “non-materialist naturalist” position which:

Next week I’ll be at the Thomistic Seminar organized by John Haldane. Haldane’s article “Realism, Mind, and Evolution” appeared last year in the journal Philosophical Investigations. Thomas Nagel’s book Mind and Cosmos is among the topics dealt with in the article. As Haldane notes, Nagel entertains the possibility of a “non-materialist naturalist” position which: would explain the emergence of sentient and then of rational beings on the basis of developmental processes directed towards their production. That is to say, it postulates principles of self-organization in matter which lead from the physico-chemical level to the emergence of living things, which then are further directed by some immanent laws towards the development of consciousness, and thereafter to reason for the sake of coming to recognize value and act in response to it, a state of affairs which is itself a value, the good of rational life. (p. 107)

As the phrases “directed towards” and “immanent laws” indicate, what Nagel is speculating about is a return to a broadly Aristotelian notion of natural teleology.Three views on natural teleology

As longtime readers of this blog know, an Aristotelian notion of natural teleology contrasts with the sort found in writers like William Paley, and can be illustrated via simple examples. The teleology or “directedness” of a watch towards the end of telling time is extrinsic to the parts of the watch, insofar as there is nothing in the bits of metal and glass that make up the watch by virtue which they inherently serve that end. The time-telling function has to be imposed on them from outside. An acorn, by contrast, is inherently directed towards the end of becoming an oak. That’s just what it is to be an acorn. Whereas the teleology of the watch is extrinsic, the teleology of the acorn is intrinsic. For Aristotle, that is what makes an acorn a natural object whereas a watch is not natural in the relevant sense but artificial. Paley’s view that natural objects are to be thought of on the model of watches and other human artifacts would in Aristotle’s view simply be muddleheaded. Precisely because they are natural -- and thus have immanent rather than extrinsic teleology -- acorns and the like are not like watches.

What explains the teleology of a natural object? The extrinsic teleology of a watch derives entirely from the maker of the watch, so that if natural objects are as Paley says they are, their teleology must derive entirely from some “designer.” For Aristotle, though (as usually interpreted), since the teleology of a natural object follows from its nature, there is no need to look beyond its nature to explain it. That is not because Aristotle denies the existence of God -- on the contrary, he famously argues for the existence of a divine Prime Mover. He just doesn’t think that a thing’s having teleological features is among the things that require a divine cause.

Aquinas takes a third position. In his view, the proximate source of a natural object’s teleological features is just its nature, and in that sense natural teleology is, as Aristotle holds, immanent. But the source of a thing’s nature, and thus the ultimate source of its teleological features, is God, so that in that sense teleology is, as Paley holds, extrinsic.

Aquinas’s position on teleology (or final causality) in this respect exactly parallels his position on efficient causality. On the latter subject, Aquinas maintains, on the one hand, that though created things or “secondary causes” derive their causal power entirely from the divine first cause, these created or secondary causes really are true causes. It really is the sun that melts the ice cube in your drink, it really is the poison oak that gives you a rash, it really is the ointment that speeds up the healing of that rash, and so forth. That is to say, the “occasionalist” view that it is only ever really God who causes anything, with secondary causes being illusory, is one that Aquinas rejects. On the other hand, Aquinas also rejects the view that secondary causes can ever operate even for an instant without God imparting their causal power to them. The notion that secondary causes could so act tends toward deism, which Aquinas would regard as an opposite error from that of occasionalism. Aquinas’s view, known as “concurrentism,” stakes out a middle ground position. (See Fred Freddoso’s important papers on this subject, here, here, and here.)

Aquinas’s views on final causality and efficient causality are closely connected. For Aquinas, the only way to make sense of how it is that an efficientcause A reliably generates a specific effect or range of effects B is if generating B is the end or final cause toward which A is inherently directed. (This is the Scholastic “principle of finality.”) Inherent or intrinsic directedness toward an end thus goes hand in hand with having efficient casual power. If we take the Paleyan view that things have no immanent teleology but only extrinsic teleology, then we are (given Aquinas’s metaphysics of causation) implicitly denying that they have genuine efficient causal power. That would leave the false appearance of their having it a result of God’smaking things happen in such a way that objects seem to have causal power (which is the occasionalist position).

So, to avoid occasionalism, we need to affirm that a natural object’s efficient causal power and its finality or teleology both have a proximate ground in the nature of the object itself, as well as an ultimate ground in the First Cause. This is also what makes natural science possible. Just as both the theist and the atheist can know the efficient causal powers of oxygen, hydrogen, sunlight, ointments, etc. just by studying these things themselves, so too can both the theist and the atheist know the teleological features of things just by studying the things themselves. Both efficient causal power and finality are there to be seen in things, whether or not someone is aware that they could not be there in the first place, even for an instant, unless both features were continuously imparted by the divine First Cause. (Compare: You can see a thing’s reflection in the mirror whether or not you realize that it can only be there even for an instant if there is something beyond the mirror which is being reflected.)

(I discuss final causality and its relation to efficient causality in depth in Scholastic Metaphysics , especially in chapter 2. I discuss and defend Aquinas’s reasons for affirming both a proximate ground of a thing’s finality in its own nature and an ultimate ground in God in my Nova et Vetera article “Between Aristotle and William Paley: Aquinas’s Fifth Way.”)

Nagel and the Fifth Way