Edward Feser's Blog, page 92

March 23, 2014

Dharmakīrti and Maimonides on divine action

Here’s a juxtaposition for you: the Buddhist philosopher Dharmakīrti (c. 600 - 660) and the medieval Jewish philosopher Moses Maimonides (1138 - 1204). Both had interesting things to say about divine action, Dharmakīrti from the point of view of a critic of theism and Maimonides from the point of view of a theist committed to “negative theology.”

Here’s a juxtaposition for you: the Buddhist philosopher Dharmakīrti (c. 600 - 660) and the medieval Jewish philosopher Moses Maimonides (1138 - 1204). Both had interesting things to say about divine action, Dharmakīrti from the point of view of a critic of theism and Maimonides from the point of view of a theist committed to “negative theology.” Theism of a sort reminiscent of Western philosophical theology has its defenders in the history of Indian philosophy, particularly within the Nyāya-Vaiśeșika tradition. In particular, one finds in this tradition arguments for the existence of īśvara (the “Lord”) as a single permanent, personal cause of the world of intermittent things. The debate between these thinkers and their Buddhist critics parallels the dispute between theists and atheists in the West. (To map the Indian philosophical traditions onto those of ancient Greece, you might compare the Buddhist position to that of Heraclitus, the Advaita Vedanta position of thinkers like Shankara (788 - 820) to that of Parmenides, and Indian theism to Aristotle’s Unmoved Mover. But the similarities should not be overstated.)Dharmakīrti’s critique of theistic arguments is usefully surveyed by Roger Jackson in his 1986 article “Dharmakīrti's Refutation of Theism” (from Philosophy East and West Vol. 36, No. 4). In response to arguments from intermittent things to a permanent cause, Dharmakīrti objects:

How, if an entity is a cause,(But is said) sometimes to be

A non-cause, can one assert in any way

That a cause is a non-cause? One cannot so assert.

Jackson comments:

Successive causality and noncausality poses a problem because the causal entity posited by the theist, īśvara, is permanent. He cannot, therefore, change from moment to moment, and if he is asserted to be causal, then he must always be causal, and can never become noncausal, for that would entail a change in nature, an impossibility for a permanent entity… Simultaneous causality and noncausality poses a problem, because īśvara is a single entity, yet is being furnished with contradictory qualities at one and the same time. Contradictory properties cannot be predicated of a single, partless entity at one and the same time, and if these properties are reaffirmed, then īśvara cannot be single, but must be multiple. Īśvaracannot, thus, be a creator of intermittent entities. (pp. 330-31)

The objection can be read as a dilemma, to the effect that īśvara either acts successively or he acts simultaneously, and each possibility leads to an unacceptable conclusion. Start with the first horn of the dilemma. If īśvara acts successively, then since intermittent things sometimes exist and sometimes do not, that means that he is sometimes causing them and sometimes not causing them. That in turn entails that he undergoes change, in which case he is not the permanent entity he is supposed to be. To put the point in Western terms, if īśvara is sometimes not causing intermittent things and then sometimes is causing them, then he goes from potency to act and is thus not immutable.

Now the Western classical theist will say that the divine first cause of things must be eternal or outside of time and thus does not act successively. Rather, he causes the world of intermittent things in a single timeless act. This brings us to the second horn of the dilemma posed by Jackson in expounding Dharmakīrti. If īśvara timelessly causes intermittent things (as the Western classical theist would put it), then he simultaneously causes an intermittent thing (insofar as he is what makes it true that such a thing exists at the times when it does exist) and does not cause it (insofar as he refrains from making it true that it exists at the times when it does not exist). But then we are making contradictory attributions to īśvara, insofar as we say both that he is causing and that he is not causing. And to avoid this contradiction by making these attributions of two different causes would be to abandon the unity attributed to īśvara.

There is a fallacy here, though, which can be seen by comparison with the following example. Suppose I am drawing a line across the top of a piece of paper, but that at the same time I am not drawing a line at the bottom of the paper. So I am both drawing and not drawing at the same time. Is there a contradiction here? No, because I am not both drawing and not drawing in the same respect. There would be a contradiction only if it were said that I am both drawing a line at the top of the page and also at the same time not drawing a line at the top of the page. But that is not what is being said. What is being said is that I am drawing a line at the top of the pageand at the same time not drawing a line at the bottom of the page, and there is no contradiction in that.

Similarly, suppose we say that īśvara timelessly causes an intermittent being A that exists from 8 am until 9 am. Then he is not causing it to be the case that A exists before 8 am or after 9 am but is causing it to be the case that A exists between 8 am and 9 am. There would be a contradiction here only if it were being claimed either that īśvara both causes and does not cause A to exist between 8 and 9 am, or if it were being claimed that īśvara both causes A to exist before 8 am and does not cause A to exist before 8 am, or if it were being claimed that īśvara both causes A to exist after 9 am and does not cause A to exist after 9 am. But of course none of these things is being claimed. What is claimed is rather that īśvara causes the existence of something that exists during the interval in question but not before or after it, and there is nothing contradictory in that.

More can be said -- which brings us to Maimonides, who, though he certainly did not have Dharmakīrti in mind, says things that imply a response to the objection under consideration. Maimonides famously holds that we cannot make affirmative predications of God but only negative predications. We can say what God is not but not what he is. What about attributions of actions to God, as when we say that God shows mercy to us? For Maimonides these should be understood as assertions not about God’s essence but rather about his effects. To say that God shows mercy is to say that his effects are like the effects a merciful human agent would produce.

Now, consider the suggestion that a diversity of effects implies diversity in the cause -- in particular, that it implies either numerically distinct causes (which, in the case of divine action, would conflict with monotheism) or a distinction of parts (which would conflict with divine simplicity). Dharmakīrti might be read as putting forward such an objection, if we interpret him as saying that insofar as īśvara both produces intermittent things and does not produce him, then we have to say either that there is more than one divine cause (one which causes intermittent things and one which does not) or distinct parts within īśvara (a part which causes intermittent things and a part which does not).

Maimonides (though, again, he is obviously not addressing Dharmakīrti himself!) responds to this sort of objection, in his Guide of the Perplexed , using the analogy of fire:

Many of the attributes express different acts of God, but that difference does not necessitate any difference as regards Him from whom the acts proceed. This fact, viz., that from one agency different effects may result, although that agency has not free will, and much more so if it has free will, I will illustrate by an instance taken from our own sphere. Fire melts certain things and makes others hard, it boils and burns, it bleaches and blackens. If we described the fire as bleaching, blackening, burning, boiling, hardening and melting, we should be correct, and yet he who does not know the nature of fire, would think that it included six different elements, one by which it blackens, another by which it bleaches, a third by which it boils, a fourth by which it consumes, a fifth by which it melts, a sixth by which it hardens things--actions which are opposed to one another, and of which each has its peculiar property. He, however, who knows the nature of fire, will know that by virtue of one quality in action, namely, by heat, it produces all these effects. If this is the case with that which is done by nature, how much more is it the case with regard to beings that act by free will, and still more with regard to God, who is above all description. (Book I, Chapter 53)

So, just as effects as diverse and indeed opposed as bleaching and blackening, hardening and melting, can be produced by one and the same cause, heat, so too can a radical diversity of effects be produced by a divine cause which is absolutely simple and unique. And (we might add, applying the point on Maimonides’ behalf to Dharmakīrti’s objection) just as heat will effect some things in one of the ways named while affecting others not at all, so too does the same absolutely simple God cause it to be the case that a thing exists at one point while not causing it to be the case that it exists at some other point.

Maimonides considers a related objection in Book II, Chapter 18, to the effect that “a transition from potentiality to actuality would take place in the Deity itself, if He produced a thing only at a certain fixed time.” Maimonides says that “the refutation of this argument is very easy,” for a transition from potency to act need occur only in things made up of form and matter. (Aquinas would add that it could occur in something immaterial but still composed of an essence together with a distinct act of existence, viz. an angel.) To suppose that since the material things of our experience go from potential to actual when they produce a temporally finite effect, so too would God have to go from potential to actual in order to produce a temporally finite effect, is to commit a fallacy of accident. All the philosophy professors who have ever lived or who are likely ever to live have been under ten feet tall, but it doesn’t follow that every philosophy professor must necessarily be under ten feet tall. And even if the causes with which we are directly aware in experience produce their effects by virtue of moving from potency to act, it doesn’t follow that every cause must necessarily move from potency to act.

(I have considered related objections in this post and this one.)

Published on March 23, 2014 19:34

March 21, 2014

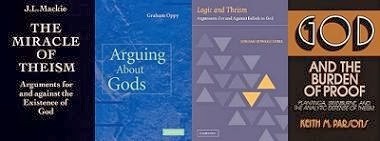

I was wrong about Keith Parsons

Longtime readers know that Prof. Keith Parsons and I have not always gotten along. Some years ago he famously expressed the view that the arguments of natural theology are a “fraud” that do not rise to the level of a “respectable philosophical position” worthy of “serious academic attention.” I hit back pretty hard at the time, and our subsequent remarks about each other over the years have not been kind. I had come to the conclusion that Prof. Parsons was unwilling to engage seriously with the best arguments of natural theology. But I am delighted to say that I was wrong. Prof. Parsons has said that his earlier remarks about the field were “unfortunate”and “intemperate and inappropriate, however qualified.” He has shown admirable grace and good sportsmanship in his willingness to bury the hatchet despite how heated things had been between us. And he has most definitely engaged seriously with the arguments of traditional natural theology in our recent exchange. I take back the unkind remarks I have made about him in the past. He is a good guy.

Longtime readers know that Prof. Keith Parsons and I have not always gotten along. Some years ago he famously expressed the view that the arguments of natural theology are a “fraud” that do not rise to the level of a “respectable philosophical position” worthy of “serious academic attention.” I hit back pretty hard at the time, and our subsequent remarks about each other over the years have not been kind. I had come to the conclusion that Prof. Parsons was unwilling to engage seriously with the best arguments of natural theology. But I am delighted to say that I was wrong. Prof. Parsons has said that his earlier remarks about the field were “unfortunate”and “intemperate and inappropriate, however qualified.” He has shown admirable grace and good sportsmanship in his willingness to bury the hatchet despite how heated things had been between us. And he has most definitely engaged seriously with the arguments of traditional natural theology in our recent exchange. I take back the unkind remarks I have made about him in the past. He is a good guy. Keith is now wrapping up his side in our initial exchange. If you have not done so already, give it a read. In the near future we will have an exchange on the subject of atheism and morality. I look forward to it. Keith has also expressed to me his admiration for the quality of the comments readers have been making on our exchange. I agree, and I thank the readers both of my blog and of Keith’s blog over at Secular Outpost.

Published on March 21, 2014 11:27

March 16, 2014

Stop it, you’re killing me!

In an op-ed piece in The New York Times, Ferris Jabr of Scientific American kindly informs us that nothing is really alive, not even Jabr himself or his readers. Fairly verbose for a dead guy, he develops the theme at length -- not by way of giving an explicit argument for his claim, so much as by putting forward considerations intended to make it appear something other than the killer joke it seems on its face to be.

In an op-ed piece in The New York Times, Ferris Jabr of Scientific American kindly informs us that nothing is really alive, not even Jabr himself or his readers. Fairly verbose for a dead guy, he develops the theme at length -- not by way of giving an explicit argument for his claim, so much as by putting forward considerations intended to make it appear something other than the killer joke it seems on its face to be. The routine is familiar, even if Jabr’s thesis is a bit more extreme than that of other biological reductionists. There’s no generally agreed upon definition of life; there are borderline cases such as viruses; living and non-living things are all made up of the same kinds of particles; so…

The “so” part is where these sorts of views get into trouble, because the reductionist conclusions -- let alone Jabr’s eliminativist conclusion -- don’t follow, and even Jabr doesn’t really claim to have establishedthat there is no such thing as life (as opposed to merely putting it out there as a proposal). Indeed, if the line between the living and the non-living is as blurry as Jabr alleges, one might just as well argue that everything is alive, rather than that nothing is.

That either extreme conclusion equally well “follows” from Jabr’s premises shows that something has gone wrong here. But then, denying apparently obvious distinctions is typically a mark of imprecise rather than rigorous thinking. So too is the marketing of such denials as “liberating” (as Jabr claims the denial that life exists is). As always, the “épater la bourgeoisie” rhetorical force of bizarre claims is doing at least as much work as the philosophical and scientific considerations are.

The essence of life

But let’s look at the latter. Jabr begins by noting:

Since the time of Aristotle, philosophers and scientists have struggled and failed to produce a precise, universally accepted definition of life. To compensate, modern textbooks point to characteristics that supposedly distinguish the living from the inanimate, the most important of which are organization, growth, reproduction and evolution. But there are numerous exceptions: both living things that lack some of the ostensibly distinctive features of life and inanimate things that have properties of the living.

End quote. Now, while we Aristotelian-Scholastic philosophers can hardly deny that there is no “universally accepted” definition of life, we maintain that a “precise” definition of life is in fact possible. Living things, the Scholastic holds, are those which exhibit immanent causation as well as transeunt (or “transient”) causation; non-living things exhibit transeunt causation alone. Transeunt causal processes are those that terminate in something outside the cause. Immanent causal processes are those which terminate within the cause and tend to its good or flourishing (even if they also have effects external to the cause). For example, an animal’s digesting of a meal is a causal process that tends to the good or flourishing of the animal itself (though it also has byproducts external to the animal, such as the waste products it excretes). By contrast, one rock’s knocking into another is a transeunt causal process, in that it does not in any sense tend to the good or flourishing of the rock itself. (For recent exposition and defense of this characterization of life, see chapter 8 of David Oderberg’s Real Essentialism , and his paper “Synthetic Life and the Bruteness of Immanent Causation.”)

Now, Scholastics distinguish between the essenceof a thing and its properties, where both terms are used in a way that is crucially different from the way they are usually used by most contemporary philosophers. One way to think of the essence of a thing is as what we capture when we give its genus and specific difference (where a “specific difference” is what differentiates one species from others in the same genus, and where “genus” and “species” are to be understood in their traditional logical, rather than biological, senses). To take a traditional example for purposes of illustration, suppose we take a human being to be a rational animal (“animal” being the genus and “rational” the specific difference). The properties of a human being (as the Scholastic uses the term “properties”) are what flow or follow from this essence, and include things like the capacity for perceptual experience, the capacity for self-movement, the ability to form concepts, and so forth. Rational animality is not the cluster of these properties, but rather that by virtue of which a thing has them. And “properties” are not any old characteristics a thing has, but only those that flow from a thing’s essence -- that is to say, those that are proper to a thing. (For exposition and defense of the Scholastic conception of essence and properties, see chapter 4 of my book Scholastic Metaphysics: A Contemporary Introduction .)

From a Scholastic point of view, the problem with too much contemporary thinking about the nature of life is that it focuses on what are really properties of life (again, in the Scholastic sense of “properties”) and tries to characterize life in terms of one of these properties or a cluster of properties. Since an essence is not a property or cluster of properties (but is rather that from which properties flow), it is no surprise that the essence of life (or of anything else for that matter) comes to seem elusive. Growth, reproduction, and the like are key to understanding life, but they are not the essence of life. They are rather properties, which flow or follow from the essence. The essence is rather a matter of the capacity of a natural substance for immanent causation or self-perfective activity -- that is to say, the ability of a thing to act for the sake of its own good or flourishing.

Now one of the several reasons why we must distinguish essence and properties is that without this distinction we cannot make sense of the distinction between normal and defective instances of a kind. For example, cats are of their nature four-legged, but that does not mean that every single cat will in fact have four legs. For genetic defect or injury might deprive some cat of one or more of its legs. Four-leggedness is a property of cats in the sense that it flows from their essence, but the flow can be “blocked,” as it were. Now if instead we think of the essence of a cat as a cluster of attributes (as contemporary metaphysicians typically would), we might conclude that “being four-legged” must not really be essential to being a cat (since there are three-legged cats), and thus must not be one of the attributes in the cluster. But we would fail thereby to capture the way in which a cat’s lacking all of its four legs is abnormal in a way that (say) its failing to be grey is not. This can be captured only by seeing four-leggedness as a true property which flows from but is nevertheless distinct from the essence (which is why in aberrant cases it may not be manifested), whereas greyness is not a property of the cat at all (in the Scholastic sense) but rather what Scholastics would call a “contingent (as opposed to proper) accident” of the cat.

In the case of defining life in general, when we fail to distinguish between essence and properties we will make similar mistakes. We might conclude, for example, that the capacity for reproduction is not really essential to living things, since there are living things (e.g. mules, and organisms whose sexual organs have been damaged) which cannot reproduce. This would be to fail to see that reproduction could still be essential to life in the sense of being a property (again, something which flows from the essence) even if in some cases it doesn’t manifest itself (where such cases are to be understood as aberrant or abnormal). In general, looking for some feature that is present in absolutely every single instance -- and then concluding, when a feature isn’t always present, that it must not really be “essential” after all -- is just too crude a way of proceeding when trying to characterize life. From an Aristotelian-Scholastic point of view, contemporary metaphysicians (and contemporary biologists when wearing their metaphysician’s hats) are simply too conceptually impoverished correctly to approach questions about essence. (Obviously this raises many questions, but the usual questions are all answered in books like Oderberg’s, and mine, which were cited above.)

Borderline cases

The absence, from contemporary thinking about essence, of the distinction between substantial form and accidental form is, like the absence of the distinction between essence and properties, another source of confusion when thinking about life. Hence some readers are bound to think of computer viruses as examples of entities that are self-perfective or act for their own good or flourishing, and would thus (it might be supposed) be candidates for living things given the Scholastic account of life. But computer viruses have merely accidental forms rather than substantial forms. That is to say, unlike true substances, which have an inherent or “built-in” principle of activity (as e.g. an acorn is inherently directed toward becoming an oak), a computer virus has an externally imposed principle of operation (as e.g. the parts of a watch have no inherent tendency to tell time, but have that function only insofar as it is imposed on them externally by the watchmaker and the users of the watch). Now a living thing is a kind of substance, with a substantial form; it is inherentlydirected toward acting for its own good or flourishing rather than being so directed only by some external factor. Since computer viruses are not like that -- qua artifacts they have only accidental forms or externally imposed principles of operation -- they are not alive, even if they mimic some aspects of life. (Of course, talk of substantial form raises many questions, which I have dealt with many times. See chapter 3 of Scholastic Metaphysics for my most detailed discussion and defense of the distinction between substantial form and accidental form.)

What of real viruses? Are they alive or not? There is no such thing as “the” Aristotelian-Scholastic position on this question, since Scholastic metaphysics must be applied to such questions in conjunction with whatever the empirical facts turn out to be. (Criticisms to the effect that the Aristotelian thinks these matters can be settled from the armchair are simply aimed at a straw man.) Oderberg argues in Real Essentialism that viruses are not alive, but the Scholastic approach to the nature of life certainly doesn’t hinge on the question. In general, the significance of borderline cases is massively overstated where questions of essence are concerned.

As I argue in Scholastic Metaphysics, the reality of essences in general cannot coherently be denied, and anything that has a regular pattern of operation or activity must ipso facto have an essence. If for some substance we find it hard to determine whether it is of kind A or kind B, it will nevertheless in fact be either of kind A or B, or of some heretofore unknown kind C. It will, that is to say, in fact have an essence, whether or not we know its essence. Where natural substances are concerned, vagueness is always epistemological rather than metaphysical.

Obviously this requires argumentation -- again, see Scholastic Metaphysics, and also Oderberg’s Real Essentialism -- but the point is that for the biological reductionist merely to cite borderline or vague cases cuts no ice. Certainly it begs the question against the Scholastic -- who has independent metaphysical reasons for the claim that vagueness is epistemological rather than metaphysical -- to suggest that viruses and the like show that there is no fact of the matter about whether a thing is alive. Just as hard cases make bad law, obsession with borderline cases (which is rife in modern philosophy) makes for bad metaphysics.

Reductionism

A third element in Jabr’s position is the implicit assumption that since living and non-living things are made of the same particles, the former must differ from the latter only in degree rather than in kind. He writes:

All observable matter is, at its most fundamental level, an arrangement of atoms and their constituent particles. These associations range in complexity from something as simple as, say, a single molecule of water to something as astonishingly intricate as an ant colony. All the proposed features of life — metabolism, reproduction, evolution — are in fact processes that appear at many different regions of this great spectrum of matter. There is no precise threshold.

End quote. Now, the “no precise threshold” stuff is, like the appeal to viruses as borderline cases, an expression of the idea that the distinction between living and non-living things is inherently vague. But whereas the appeal to viruses has to do with considerations specific to that kind of entity, here the appeal is to more general metaphysical considerations. In particular, it is an appeal to the thesis that all natural objects are “really” “nothing but” fundamental particles. “Therefore” whatever is true of any natural object must (Jabr presumably holds) “really” be a truth about how fundamental particles are arranged.

We saw some time back how this assumption determines how Alex Rosenberg approaches the question of life in his book The Atheist’s Guide to Reality. We also saw, in the same post, how Rosenberg is led -- implicitly rather than explicitly in his case -- to just the sort of eliminative position vis-à-vis life that Jabr endorses. And we saw too that there are no good arguments whatsoever for that position. For there are no good arguments for the assumption that it rests on, viz. that whatever is real must “really” be “nothing but” particles and their arrangements. (See also this follow-up post on Rosenberg’s biological reductionism.)

To be sure, it is often claimed that “science shows” that this is the case, but science shows nothing of the kind. Rather, the view in question -- essentially a modern riff on the atomism of Democritus and Leucippus -- is read into science and then read back out again. The Aristotelian-Scholastic position is that there are irreducible natural substances wherever there are irreducible causal powers, and where there are irreducible substances the parts of such substances -- including the particles in question -- exist in them virtually rather than actually. In that sense, the substances are, metaphysically speaking, more fundamental than the particles, not less. (For the full story, see chapter 3 of Scholastic Metaphysics.)

Now, in the Aristotelian-Scholastic tradition, the fundamental divisions in the natural world are between the inorganic and the organic, between merely vegetative forms of life (in the technical Aristotelian sense of “vegetative”) and sentient forms of life, and between sentient forms of life and the rational sort of life characteristic of human beings. If atomism or its modern variants had in fact been proved by modern science, then we would expect that none of these divisions would be problematic for the contemporary naturalist. But in fact they all remain problematic. The difficulties facing reductive accounts of the “propositional attitudes” (beliefs, desires, etc.) are well-known to philosophers of mind, as are the difficulties facing attempts to give a reductive account of “qualia.” Yet the distinction between propositional attitudes (with their characteristic intentional content) on the one hand and merely qualitative mental states on the other is, essentially, the distinction between what Aristotelians would call intellective or rational powers and mere sentience; that is to say, it marks the third of the fundamental divisions in nature affirmed by the Aristotelian. And the distinction between creatures which possess qualia and those which do not is very close to the distinction the Aristotelian traditionally draws between sentient and non-sentient forms of life; that is to say, it marks the second of the fundamental divisions in nature affirmed by the Aristotelian.

Then there is the division between the inorganic and the organic. As the atheist and naturalist philosopher Alva Noë has acknowledged:

Science has produced no standard account of the origins of life.

We have a superb understanding of how we get biological variety from simple, living starting points. We can thank Darwin for that. And we know that life in its simplest forms is built up out of inorganic stuff. But we don't have any account of how life springs forth from the supposed primordial soup. This is an explanatory gap we have no idea how to bridge...

[W]e have large-scale phenomena in view (life, consciousness) and an exquisitely detailed understanding of the low-level processes that sustain these phenomena (biochemistry, neuroscience, etc). But we lack any way of making sense of the idea that the higher-level phenomena just come down to, or consist of, what is going on at the lower level…

A living cell is more than just a chemical compound, even if every part of the cell is composed of inorganic elements. A cell, after all, is alive. What we lack, as in the case of mind, is a way of understanding how life happens due to the mere combination of nonliving precursors.

End quote. In other words, how to reduce the organic to the inorganic is (hoopla over the Miller-Urey experiment and the like notwithstanding) no more evident now than it was when Galileo and Co. pushed the Aristotelian-Scholastic tradition to the margins of Western intellectual life. (I had reason to discuss Noë’s views at greater length hereand here, and questions about the origin of life at greater length here.)

So, the traditional Aristotelian divisions in nature are really no closer to being dissolved today than they ever were. And there is, I maintain, no argument to the contrary that doesn’t beg all the important questions. “We ‘know’ that the older, Aristotelian metaphysics is wrong and naturalist metaphysics correct because ‘science shows’ this; and we ‘know’ that this is the correct way to interpret ‘the science’ because we ‘know’ that the older metaphysics is wrong and that a naturalist metaphysics is better.” There really is nothing more to the contemporary consensus than this kind of circular reasoning.

In any event, I defend the radically anti-reductionist, Aristotelian hylemorphist approach to understanding the natural world at length in Scholastic Metaphysics (as does Oderberg in Real Essentialism). Reductionist appeals to arrangements of particles etc. that do not respond to Aristotelian arguments merely assume precisely what is at issue, since the Aristotelian would agree with the naturalist on the scientific facts but dispute the naturalist’s interpretation of those facts. You might say that the rumors of Aristotle’s death have been greatly exaggerated (as this, and this, and this, and this, and thisall indicate). And thus so too are rumors to the effect that “nothing is truly alive.”

Published on March 16, 2014 16:19

March 13, 2014

L.A. area speaking engagements

On Saturday, March 29, I’ll be the keynote speaker at the Talbot Philosophical SocietySpring Conference at Biola University in La Mirada, CA. The theme of the talk will be “The Scholastic Principle of Causality and the Rationalist Principle of Sufficient Reason.” Bill Vallicella will be the respondent. Come out and see the dueling philosophy bloggers.

On Saturday, March 29, I’ll be the keynote speaker at the Talbot Philosophical SocietySpring Conference at Biola University in La Mirada, CA. The theme of the talk will be “The Scholastic Principle of Causality and the Rationalist Principle of Sufficient Reason.” Bill Vallicella will be the respondent. Come out and see the dueling philosophy bloggers. On Friday, April 4, I’ll be speaking at Thomas Aquinas College in Santa Paula, CA. The theme of the talk will be “What We Owe the New Atheists.” More information here.As I’ve previously announced, summer speaking engagements outside the L.A. area include events in Newburgh, NY, Berkeley, and Princeton.

Published on March 13, 2014 10:39

March 8, 2014

Gelernter on computationalism

People have asked me to comment on David Gelernter’s essay on minds and computers in the January issue of Commentary. It’s written with Gelernter’s characteristic brio and clarity, and naturally I agree with the overall thrust of it. But it seems to me that Gelernter does not quite get to the heart of the problem with the computer model of the mind. What he identifies, I would argue, are rather symptomsof the deeper problems. Those deeper problems are three, and longtime readers of this blog will recognize them. The first two have more to do with the computationalist’s notion of matter than with his conception of mind.As I have emphasized many times, most participants in the debate between materialism and dualism, on both sides, simply take for granted a conception of matter inherited from Galileo, Descartes, Newton, and the other early moderns. On that conception, matter is essentially devoid both of teleology and of the qualitative features that common sense attributes to it. That is to say, there is, on this view of matter, nothing inherent to it that corresponds to the “directedness” toward an end (or “finality,” to use the Scholastic jargon) that the Aristotelian attributes to all natural substances. Nor are secondary qualities like color, sound, odor, etc. as common sense understands them (that is to say, as we “feel” them in conscious awareness) really out there in matter itself. What is there, on this view, is only color as redefinedfor purposes of physics (in terms of the surface reflectance properties of objects), sound as redefined (in terms of compression waves), and so forth. Matter on this conception is exhaustively describable in terms of the quantifiable categories to which physics confines itself.

People have asked me to comment on David Gelernter’s essay on minds and computers in the January issue of Commentary. It’s written with Gelernter’s characteristic brio and clarity, and naturally I agree with the overall thrust of it. But it seems to me that Gelernter does not quite get to the heart of the problem with the computer model of the mind. What he identifies, I would argue, are rather symptomsof the deeper problems. Those deeper problems are three, and longtime readers of this blog will recognize them. The first two have more to do with the computationalist’s notion of matter than with his conception of mind.As I have emphasized many times, most participants in the debate between materialism and dualism, on both sides, simply take for granted a conception of matter inherited from Galileo, Descartes, Newton, and the other early moderns. On that conception, matter is essentially devoid both of teleology and of the qualitative features that common sense attributes to it. That is to say, there is, on this view of matter, nothing inherent to it that corresponds to the “directedness” toward an end (or “finality,” to use the Scholastic jargon) that the Aristotelian attributes to all natural substances. Nor are secondary qualities like color, sound, odor, etc. as common sense understands them (that is to say, as we “feel” them in conscious awareness) really out there in matter itself. What is there, on this view, is only color as redefinedfor purposes of physics (in terms of the surface reflectance properties of objects), sound as redefined (in terms of compression waves), and so forth. Matter on this conception is exhaustively describable in terms of the quantifiable categories to which physics confines itself. Now for the Aristotelian, the point isn’t that the moderns’ conception of matter is wrong so much as that it is incomplete. The trouble is not with thinking of matter the way Galileo, Descartes, and their successors have, but with taking this to be an exhaustive conception, as something other than a mere abstraction from a much richer concrete reality. And if it is taken as an exhaustive conception, then a Cartesian form of dualism is hard to avoid. For to say that matter is essentially devoid of qualitative features like color, sound, taste, etc. and that these exist only as the qualia of conscious experience just is to make of qualia something essentially immaterial. And to say that matter is essentially devoid of anything like “directedness” or “finality” is ipso facto to make of the “directedness” or “intentionality” of desires, fears, and other such states also something essentially immaterial. Cartesian dualism was not a rearguard reaction against the early moderns’ new conception of matter, but on the contrary a direct consequence of that conception. (I addressed this issue at length in my series of posts on the critics of Thomas Nagel’s Mind and Cosmos, and it is a point Nagel himself has also emphasized.)

This brings us to the first of the three deep problems with computationalism. Computationalists, like materialists in general but also like Cartesians (though unlike us Aristotelians), take for granted the broadly Galilean or Cartesian conception of matter. Hence they will never in principle be able to fit the qualia definitive of consciousness into their account of the mind, since they are operating with a conception of matter that implicitly excludes the qualitative from material processes from the get go. Their accounts of the qualitative will therefore always in effect either change the subject or amount to a disguised eliminativism. This result can be avoided by giving up the assumption that the Galilean/Cartesian conception of matter really captures all there is to matter, but this would amount to abandoning materialism in favor of one of its rivals (if not Aristotelianism, then neutral monism, panpsychism, or the like).

The second deep problem with computationalism is that on a Galilean/Cartesian conception of matter, there can be nothing inherentto the material world that corresponds to notions like “information,” “algorithm,” “symbols,” and the like. For these notions smack of the “directedness” or intentionality that the Galilean/Cartesian conception denies to matter. The notion of a material “symbol” could be relevant to explaining mental phenomena only if it is aboutsomething; the notion of “information” could be relevant to explaining thought only if it entails semantic content; and so forth. Yet there can be no such thing as aboutness, semantic content, or the like in a material world utterly devoid of “directedness” or “finality.” Hence the key notions of computationalism can on a Galilean/Cartesian conception of matter at best be regarded only as observer-relativefeatures of the material world rather than intrinsic to the material world, and are, accordingly, not available as ingredients in a scientific account of the mind. This is a point John Searle made in his 1990 article “Is the Brain a Digital Computer?” (in a line of argument that is distinct from, and deeper than, his better known “Chinese Room” argument). Similar arguments have been made by Saul Kripke, Karl Popper, and others. (I develop the point in The Last Superstition , and have discussed Searle’s and Popper’s arguments here, and Kripke’s argument here.)

Here too the problem can be avoided by abandoning the Galilean/Cartesian conception of matter. But to regard something like information and algorithmic processes as intrinsic to material substances is precisely to return to something like an Aristotelian conception of the world and its commitment to formal and final causes. (Rightly understood, that is -- not the crude caricatures of formal and final causality usually attacked in discussions of these matters.) As the neuroscientist Valentino Braitenberg once put it:

The concept of information, properly understood, is fully sufficient to do away with popular dualistic schemes invoking spiritual substances distinct from anything in physics. This is Aristotle redivivus, the concept of matter and form united in every object of this world, body and soul, where the latter is nothing but the formal aspect of the former. The very term ‘information’ clearly demonstrates its Aristotelian origin in its linguistic root.

Indeed, I would say that something at least likecomputationalism, if conjoined with an Aristotelian conception of matter, might shed considerable light on the mental lives of non-human animals. However, this would still leave untouched what is distinctive about human beings -- our capacity to form abstract concepts (as when we form the concepts man and mortal), to put them together into judgments (as when we judge that all men are mortal), and to reason from one judgment to another in a logical way (as when we conclude from all men are mortal and Socrates is a man that Socrates is mortal). This brings us to the third problem with computationalism, which is that the most a computational system can ever do is simulate conceptual thought, and never in principle actually carry it out.

The reason is that material symbols and processes cannot in principle have the universality of reference and determinacy of content that are characteristic of concepts. For example, the concept triangle of its nature applies to every single triangle without exception, whereas a material symbol either has no inherent connection to triangles at all (as in the case of the English word “triangle,” which applies to triangles merely by convention) or has an inherent connection but strictly applies only to some triangles but not all (as in a drawing of a triangle, which will always be either equilateral, isosceles, or scalene and thus strictly apply only to some of these but not all; will be of a specific color that not all triangles have; and so forth). There is also nothing in the material properties of any symbol or system of symbols that entails any determinate or exact representational content. For example, there is nothing in the symbol “triangle” that entails that it represents a specific triangle, or triangles in general, or the word “triangle” itself, or a person who calls himself “triangle,” or what have you. And merely adding further material symbols as interpretations of the first just kicks the problem up to a higher level, since these symbols themselves are, qua purely material, as indeterminate in their representational content as the one we started out with.

The basic point is as old as Plato and Aristotle and has been in recent years developed by James Ross, and I develop and defend Ross’s argument at length in my American Catholic Philosophical Quarterlyarticle “Kripke, Ross, and the Immaterial Aspects of Thought.” (I briefly sketched the argument in my review of Ray Kurzweil’s book How to Create a Mind in First Things, and had reason to discuss it in a recent series of blog posts, here, here, here, and here.)

Hence, from an Aristotelian point of view, even if qualia and some kinds of intentionality could be regarded as corporeal features of organisms on a “beefed up,” neo-Aristotelian conception of matter, conceptual thought could not be, and thus could not be captured even by a suitably updated computationalism. Conceptual thought -- which is distinctive of our rational or intellectual powers as Aristotelians understand them -- is essentially incorporeal.

When Gelernter rightly complains of the inability of computationalism to account for the subjectivity of conscious experience, then, I would argue that this inability is a symptom of the computationalist’s implicit commitment to a Galilean/Cartesian conception of matter, from which the qualitative has been extruded. It isn’t computationalism per se that is the problem, at least if the computationalist categories could be reinterpreted (as perhaps Braitenberg would interpret them) in an Aristotelian fashion. Subjectivity, in any case, isn’t for the Aristotelian the mark of the corporeal/incorporeal divide, since non-human animals (like Nagel’s famous bat) are entirely corporeal but nevertheless have subjective experiences of a sort.

Similarly, when Gelernter points out that “computers can be made to operate precisely as we choose; minds cannot,” I would argue that this is a consequence of the deeper point that the conceptual content of thought cannot be reduced to any set of relations between material symbols. There can in principle never be anything more than a very rough and general correlation between, on the one hand, the structure of corporeal states (whether in the brain, the organism as a whole, or the organism together with its environment), and, on the other hand, the conceptual content of our thoughts. Hence, even if we had total technological mastery of the relevant corporeal features of a human being, we would still never be able, even in principle, to predict and control the content of human thought with precision.

Some of Gelernter’s other points (such as that “computers can be erased; minds cannot”) are also important and deserve closer analysis than I have time to provide here. Still, they seem to me less fundamental than what I take to be the most basic problems with computationalism.

Gelernter also makes some suggestive remarks about emotions and experiences. He writes, for example, that “feelings are not information! Feelings are states of being… To experience is to be some way, not to do some thing.” This cries out for elaboration, which he does not have space to give in the article. What exactly does Gelernter have in mind here by the distinction between “being” and “doing”?

One way to read this might be in terms of what in recent analytic philosophy has been called the distinction between “categorical” and “dispositional” properties. A dispositional property would be one that a thing has when a certain conditional statement is true of it, namely a statement to the effect that if a certain kind of stimulus is present to the thing, then a certain kind of manifestation will follow. For example, brittleness is a dispositional property insofar as it involves the truth of a conditional to the effect that if a brittle thing is struck with a hard object, then it will shatter. Categorical properties, by contrast, would be those a thing simply has, unconditionally as it were. Shape is sometimes given as an example insofar as (it is sometimes held) a thing’s shape is something it simply has, unconditionally rather than merely as a manifestation in the presence of an appropriate stimulus.

Now whether the distinction holds up -- as opposed to purported categorical properties being ultimately reducible to dispositional ones, or purportedly dispositional ones being reducible to categorical ones -- is a matter of controversy in recent analytic metaphysics. (I discuss the controversy, and the relationship between the categorical/dispositional distinction and the Scholastic theory of act and potency, in Scholastic Metaphysics: A Contemporary Introduction .) But it is certainly relevant to the dispute in recent philosophy of mind over whether the qualia characteristic of emotional states and other conscious experiences can be explained in materialist terms. Functionalism -- of which computationalism is a variety -- essentially takes all mental phenomena to be describable in dispositional terms. The belief that it is raining or the experience of pain in one’s back, for example, would be characterized as internal states that will tend under appropriate conditions to manifest themselves by generating certain further internal states and/or certain kinds of overt behavior (grabbing an umbrella in the first case, say, or moaning in the second case). The critic of functionalism then objects that the feel or “quale” of the pain is something that the person or animal having it has, or at least might have, categorically, apart from any associated disposition. For the feel or quale of the pain could in principle exist (so the argument goes) even if it were associated instead with a disposition to laugh rather than moan, and the disposition to moan could exist even if it were associated with some quale other than the one we associate with pain, or indeed with no qualia at all (as in the case of a “zombie”).

Yet from an Aristotelian-Scholastic point of view such arguments are deficient, both because the categorical/dispositional distinction is too crude and fails to capture all the nuances enshrined in the theory of act and potency (as I discuss in Scholastic Metaphysics), and because “zombies” and related notions are dubious insofar as they reflect a Galilean/Cartesian conception of matter of the sort the Aristotelian would reject (a topic I discussed in a recent post).

But Gelernter might have something else in mind, and there may in any event be another way to elaborate his point.

Published on March 08, 2014 16:06

March 7, 2014

Can you explain something by appealing to a “brute fact”?

Prof. Keith Parsons and I have been having a very cordial and fruitful exchange. He has now posted a response to my most recent post, on the topic of “brute facts” and explanation. You can read his response here, and find links to the other posts in our exchange here. Since by the rules of our exchange Keith has the last word, I’ll let things stand as they are for now and let the reader imagine how I might respond.

Prof. Keith Parsons and I have been having a very cordial and fruitful exchange. He has now posted a response to my most recent post, on the topic of “brute facts” and explanation. You can read his response here, and find links to the other posts in our exchange here. Since by the rules of our exchange Keith has the last word, I’ll let things stand as they are for now and let the reader imagine how I might respond. Another one of my old sparring partners, Prof. Robert Oerter, raises an interesting objection of his own in the combox of my recent post, on which I will comment. I had argued that if we think of laws of nature as regularities, then no appeal to such laws can explain anything if the most fundamental such laws are regarded as inexplicable “brute facts.” Oerter writes:To change the example, consider: “The cause of the forest fire was the lightning that hit that tree.”

Suppose the lightning was a brute fact (a bolt out of a clear blue sky, as it were). How does its brute-fact-ness in any way decrease its explanatory power? It's still the cause of the forest fire, isn't it?

End quote. Now, let me first reiterate that my remarks in the earlier post were about, specifically, laws of nature understood as regularities. Even if Oerter’s example were a case of a brute fact serving as a genuine explanation, that wouldn’t affect the point that laws understood as regularities wouldn’t be true explanations if the fundamental level of laws were a brute fact. (And Oerter may well agree with that much, for all I know.)

But Oerter’s question is still a fair one. Whatever we think of the regularity view of laws, we might yet wonder whether other kinds of thing might be genuinely explanatory even if they were brute facts. Wouldn’t Oerter’s imagined bolt of lightning be a good example?

I would say that on analysis it would notbe. Consider first that we can distinguish a metaphysical sense in which something might be claimed to be a “brute fact” from an epistemological sense in which it might be. Something would be a brute fact in the epistemological sense if, after exhaustive investigation, we did not and perhaps even could not come up with a remotely plausible explanation for it. Something would be a brute fact in the metaphysical sense if it did not, as a matter of objective fact, have any explanation or intelligibility in the first place. With a metaphysical brute fact, it’s not merely that we can’t discover any explanation, it’s that there isn‘t one there to be discovered.

Now I do not deny that there could be epistemological “brute facts,” but only that there could be metaphysicalbrute facts. But it seems clear that whatever plausibility Oerter’s example has derives entirely from the possibility that a bolt of lightning of the sort he imagines might be an epistemological brute fact. For we can certainly imagine cases where a bolt of lightning strikes and causes a forest fire but where there was only clear blue sky and no storm clouds present, nor even some bizarre cause (a gigantic Tesla coil, say, or an angry Thor flying about). But that by itself is just to imagine unexplained lightning appearing. It does not amount to imagining lightning that as a matter of objective fact has no explanation suddenly appearing. (And as I have argued in several places, and at greatest length in Scholastic Metaphysics , in fact we cannot, contra Hume, coherently describe a case where this latter sort of thing happens.)

Indeed, it isn’t even quite right to say that what Oerter is describing is a case of a cause that is entirely epistemologically“brute,” let alone metaphysically brute. For of course, the reason why we’re willing to regard an unexplained instance of lightning as a cause of a forest fire is that we know a lot about lightning in general, such as that it can cause forest fires. So, whether or not we know the source of the lightning Oerter asks us to imagine, we know at least that it is lightning, and it is because we know that it is an instance of that general class of thing that we regard it as the sort of thing that could cause a forest fire. We know, in effect, its formal and material causes insofar as we know that it is lightning rather than (say) a hallucination or some atmospheric condition that merely superficially resembles lightning. And we know also its final cause insofar as we know that it has certain causal powers such as the power to ignite wood, where casual powers are “directed” toward their outcomes as toward an end. What we lack is, at most, merely knowledge of the lightning’s own efficientcause. Precisely for that reason, though, the lightning is not a “brute fact,” full stop, either metaphysically or epistemologically, even if there is an at least epistemologically “brute” aspect to it.

But we can say more. For the lightning causes the forest fire precisely insofar as (the Aristotelian will say) it actualizes the potentiality of whatever foliage it strikes to catch fire. But the lightning can do this only insofar as it is itself actualized (for, since the lightning is not a necessarily existing thing, it too has to go from potential to actual). And whatever is actualized (so the Aristotelian will also say) is actualized by something already actual. Now what we’ve got in any case where C is actualized by B only insofar as B is in turn actualized by A is an essentially ordered causal series, in which the action of the members lower down in the series is unintelligible apart from the impartation to them of causal power by members higher up in the series. This, of course, is the basis for Scholastic arguments to the effect that the lightning could not exist and operate at all even for an instant apart from a purely actual (and thus divine) conserving and concurring cause, who is first in the essentially ordered series in question. But that conclusion can be bracketed off for present purposes. What matters for the moment is just that on the Scholastic analysis, the lightning cannot intelligibly actualize without itself being actualized (whether or not this regress leads us to a divine first actualizer).

So, to conceive of the lightning as a cause of the fire, we ultimately cannot avoid thinking of it as having an efficient cause of its own -- at least to conserve in being, and concur in, its causal activity at the moment at which it actualizes the fire. Hence our grasp of its being a cause of the fire entails bringing in all of the four causes, in which case it is hardly an unintelligible “brute fact.” Of course, this analysis brings in specifically Aristotelian-Scholastic metaphysical notions, but there is nothing suspect about that. For in order to evaluate a claim like Oerter’s claim that a bolt of lightning can be a genuine explanation even if it had no explanation of its own, we need to ask ourselves what it is to be an explanation in the first place, and in particular what it is to be a causal explanation (since the lightning is in the case at hand claimed to provide a causal explanation of the fire). And the Scholastic holds, on independent grounds, that formal, material, final, and efficient causes are all part of a complete explanatory story.

If Oerter or anyone else wants to reject this metaphysical picture they are free to do so, but then they have to provide an alternativemetaphysical story about how explanation and causation work -- and it has to be a story on which the lightning could be a genuine explanation of the fire without having an explanation of its own. Merely suggesting that the fire would be an explanation even if it lacked an explanation of its own is not enough, for this either fails to describe the situation in sufficient metaphysical detail to allow us to conclude anything from it (if no account of explanation and causation is given) or it will beg the question (if some non-Scholastic account of explanation and causation is implicitly being presupposed).

I would say that what would clearly make Oerter’s case is an example where it is evident both (i) that A genuinely explains B, and yet (ii) that A has no formal, material, efficient, or final cause of its own. In such a case A itself would clearly be a “brute fact.” But I submit that no such example is forthcoming. For the more we peel away formal, material, final, and efficient causality from our conception of A, the more we, by that very fact, peel away anything in A that could make of it an explanation of B or of anything else. A cause is intelligible as a cause only insofar as it is intelligible in itself.

[For earlier posts on related matters, go hereand here.]

Published on March 07, 2014 14:54

March 2, 2014

An exchange with Keith Parsons, Part IV

Here I respond to Keith Parsons’ fourth post. Jeff Lowder’s index of existing and forthcoming installments in my exchange with Prof. Parsons can be found here.

Here I respond to Keith Parsons’ fourth post. Jeff Lowder’s index of existing and forthcoming installments in my exchange with Prof. Parsons can be found here. Keith, as we near the end of our first exchange, I want to thank you again for taking the time to respond to the questions I raised, and as graciously as you have. You maintain in your most recent post that explanations legitimately can and indeed must ultimately trace to an unexplained “brute fact,” and that philosophers who think otherwise have failed to give a convincing account of what it would be for the deepest level of reality to be self-explanatory and thus other than such a “brute fact.” Unsurprisingly, I disagree on both counts. I would say that appeals to “brute facts” are incoherent, and that the nature of an ultimate self-explanatory principle can be made intelligible by reference to notions that are well understood and independently motivated.Now, a number of philosophical issues come up in your post that are bound to arise in a discussion of this topic -- laws of nature, the principle of sufficient reason (PSR), the principle of causality (PC), Humean and other objections to PSR and PC, and so forth. Obviously we cannot address all this in any depth in a series of blog posts, especially given the word count Jeff has asked us to abide by. I have addressed all of these issues in detail in my new book Scholastic Metaphysics: A Contemporary Introduction . For the moment let me summarize a few key points.

First, I would say that appeals to laws of nature are far more problematic than most naturalists seem to realize. For what is a law of nature, and why does it operate? Like some contemporary philosophers of science and metaphysicians who have no theological or Scholastic axe to grind (e.g. Nancy Cartwright, Brian Ellis, Stephen Mumford) I would say that what we are describing when we talk of “laws of nature” are really just the ways a thing will tend to operate given its nature or essence. In that case, though, the existence of a law of nature presupposes, and thus cannot explain, the existence of the concrete physical things, with their distinctive natures, whose operations the law describes -- in which case laws of nature are not available to the naturalist as a terminus of explanation (“brute fact” or otherwise).

Suppose this neo-Aristotelian account of laws is rejected. What alternative views are there? None that help the naturalist who thinks laws provide an ultimate explanation. For example, early modern philosophers and scientists like Descartes and Newton regarded laws simply as divine decrees. (I do not accept this view myself, by the way; indeed, it was intended by the early moderns as an anti-Scholastic approach to understanding nature.) On this view, laws of nature cannot be ultimate explanations because they are merely the expression of something else, viz. God’s commands. That -- and, of course, the theological presuppositions of this view -- make it unavailable to the naturalist looking to make laws ultimate.

How about a Platonic view of laws? On this view laws are abstract objects that concrete physical phenomena “participate” in. But what is it that brings it about that the phenomena participate in the laws? And why is it these laws rather than some others that the phenomena participate in? On this view it is not the laws themselves, but rather whatever it is that answers these questions (a Platonic demiurge?), that will be the ultimate explanation of things. On this view too, then, laws are not available to the naturalist as an ultimate explanation (again, “brute” or otherwise).

How about a regularity view of laws? On this Humean view, to say that it is a law that A’s are followed by B’s is just to assert a regular correlation between A’s and B’s, perhaps together with something else (such as a counterfactual conditional to the effect that had an A been present a B would have been present as well). The trouble here is that laws so understood, whether “ultimate” or otherwise, don’t explain anything at all. If it is the case that A’s are always in fact followed by B’s and that a B would have been present had an A been present, then to call this a “law” merely re-describesthis fact, rather than making it intelligible.

Nor does it help to say that the “law” in question is a special case of some other law, because that just relocates the problem rather than solving it. If to say “It is a law that A’s are followed by B’s” doesn’t by itself explain anything, then it doesn’t help to say that this is a special case of a law relating C’s and D’s, if the statement “It is a law that C’s are followed by D’s” alsoby itself doesn’t explain anything. And this is true no matter how far down you go, as long as what you stop with is itself just some further “brute” regularity. The “bruteness” is not confined to the bottom level but exists all the way up and down the series. To suppose otherwise is like supposing that a set of IOU’s counts as real money as long as you stack them high enough. The IOU’s at the top of the stack are no more real money than the ones at the bottom are, and the higher level laws on a regularity theory are no more explanatory than the bottom “brute” level laws are.

Hence while the regularity theory might be claimed to provide an account of explanation alternative to those implied by the Aristotelian, Platonic, and theological accounts of laws, in fact it is not an account of explanation at all but, implicitly if not explicitly, the giving up of the possibility of explanation (ultimate or otherwise). And it is hard to see what motivation there could possibly be for a theorist of laws of nature to accept it, other than as an ad hoc way of avoiding commitment to an Aristotelian, Platonic, or theological view of laws. (Ockham’s razor is certainly not a good motivation, for Ockham’s razor is a principle of explanation, and the regularity view makes laws non-explanatory.)

So, Keith, it seems to me that your position has the following serious problem. You want to endorse a form of naturalism according to which real explanations are possible at levels of physical reality higher than the level of the fundamental laws of nature, yet where these explanations rest on a bottom level of physical laws that have no explanation at all but are “brute facts.” But this view is, I maintain, incoherent. For if you endorse a regularity view of laws, then you will have no genuine explanations at all anywhere in the system. All of reality, and not just the level of fundamental physical laws, will amount to a “brute fact.” Whereas if you endorse instead an Aristotelian, Platonic, or theological view of laws, then you would be acknowledging that all laws of nature, including even the fundamental laws, are dependent on something else and thus cannot provide ultimate explanations -- and you would also in each case be taking on other commitments incompatible with your naturalism.

Now that’s just one problem for your position. There are others. For example, I would also argue (and argue at length in the book) that Humean and other objections against PSR and PC all fail. For instance, when Humeans argue for the conceivability of something existing without a cause or explanation, and then take that to entail the real possibility of something existing without a cause or explanation, they are committing a very crude fallacy. The most that Humean arguments show is that we can conceive of a thing without conceiving of its cause or explanation, but to conceive of A without conceiving of B simply doesn’t entail that A can really exist without B. We can conceive of something’s being a triangle without conceiving of its being a trilateral, but any triangle must also be a trilateral; we can conceive of a man without conceiving of his height, but any actual man must have some height or other; and so forth. (Humean arguments are problematic in other ways too, as I show in the book.)

I would also argue that PSR, rightly understood -- that is, in its Scholastic version rather than in the Leibnizian rationalist versions usually considered in contemporary discussions of the subject -- cannot coherently be denied. Consider that whenever we accept a claim as rationally justified, we suppose not only that we have a reason for accepting it (in the sense of a rational justification), but also that our having this reason is the reason why we accept it (in the sense of being the cause or explanation of our accepting it). We suppose that our cognitive faculties track truth and standards of rational argumentation, and that it is because they do that we believe the things we do. But if PSR is false, then we can have no justification for supposing that any of this is really the case. We may in fact believe what we do for no reason whatsoever, and yet it might also falsely seem, again for no reason whatsoever, that we believe things for reasons. And our cognitive faculties may have the deliverances they do for no reason whatsoever -- rather than because they track objective truth and standards of logic -- and yet it might also falsely seem, for no reason whatsoever, that they do track the latter.

In short, either everything has an explanation or we can have no justification for thinking that anything does. No purported middle ground position, on which some things have genuine explanations while others are “brute facts,” can coherently be made out. If there really could be unintelligible “brute facts,” then even the things we think are not brute facts may in fact be brute facts, and the fact that it falsely seems otherwise to us may itself be yet another brute fact. We could have no reason to believe anything. Rejecting PSR entails the most radical skepticism -- including skepticism about any reasoning that could make this skepticism itself intelligible. Again, the view simply cannot coherently be made out.

Finally, as to your claim, Keith, that the accounts Scholastics and others give of something’s being self-explanatory make use of “obscure” notions, I would deny that there is any good reason for this charge. Take the Aristotelian theory of actuality and potentiality, on which is based the Scholastic thesis that God is pure actuality. When you say that such claims “sound… like verbal formulas devised to obviate a problem rather than solve it,” that gives the impression that they are spun out of whole cloth in an ad hoc way in order to give the theist something to say in response to his critic -- as if the theist were saying: “How can something be self-explanatory? Hmm, er, well now, let me think… Oh, wait! How about this: A self-explanatory terminus of explanation would be one that is pure actuality! Yeah, that’s the ticket…”

But of course that’s not at all what is going on. The theory of actuality and potentiality was originally developed for reasons that have nothing to do with natural theology, but rather as a way of responding to Parmenidean arguments against the possibility of genuine change. It is also a theory that is recapitulated in other contexts having nothing to do with natural theology. For example, the revival of interest in the notions of active and passive causal powers in contemporary metaphysics and philosophy of science is largely a recapitulation of the ancient theory of actuality and potentiality (in ways I discuss in my Scholastic Metaphysics book). If the jargon seems “obscure,” it is obscure only in the way the jargon of any philosophical or scientific theory is “obscure” -- obscure when considered in isolation and outside the context of the theory, but not at all obscure once one has studied the ideas and arguments and seen how the terminology works in its theoretical context.

Now, the same thing is true of other notions made use of to account for what would make something self-explanatory -- the essence/existence distinction, the notion of being simple or non-composite, etc. They are not at all obscure or ad hoc but have a worked-out theoretical justification independent of their application to natural theology, though when unpacked they turn out to have theological implications. (Scholastics would not agree, by the way, that all necessity boils down to logical necessity. Rather, logical necessity itself presupposes metaphysical necessity.)

Anyway, I thank you again, Keith, for a very useful and civil exchange. As per the agreed format, the last word in this first round is yours. I will brace myself!

Published on March 02, 2014 11:35

February 28, 2014

An exchange with Keith Parsons, Part III

Here I respond to Keith Parsons’ third post. Jeff Lowder’s index of existing and forthcoming installments in my exchange with Prof. Parsons can be found here.

Here I respond to Keith Parsons’ third post. Jeff Lowder’s index of existing and forthcoming installments in my exchange with Prof. Parsons can be found here. I’d like to respond now, Keith, to your comments about Bertrand Russell’s objection to First Cause arguments. Let me first make some general remarks about the objection and then I’ll get to your comments. Russell wrote, in Why I Am Not a Christian:

If everything must have a cause, then God must have a cause. If there can be anything without a cause, it may just as well be the world as God, so that there cannot be any validity in that argument. (pp. 6-7)The context makes it clear that Russell is presenting this as a knock-down refutation of the First Cause argument. For example, he immediately goes on to say that that argument “is exactly of the same nature as” and “really no better than” the view that the world rests on an elephant which rests on a tortoise, where the question what the tortoise rests on is left unanswered.

Now, this might be a knock-down refutation of a First Cause argument if such an argument either rested on the premise that absolutely everything without exception has a cause, or made a sudden, unexplained exception to this general rule in the case of God. For in the first case the argument would be guilty of contradicting itself, while in the second case it would be guilty of special pleading.

The trouble is that none of the major proponents of First Cause arguments (Avicenna, Maimonides, Aquinas, Scotus, Leibniz, Clarke, et al.) actually ever gave an argument like the one Russell appears to be attacking. For none of them maintain in the first place that absolutely everything has a cause; what they say instead is that the actualization of a potential requires a cause, or that what comes into existence requires a cause, or that contingent things require a cause, or the like. Nor do they fail to offer principled reasons for saying that God does not require a cause even though other things do. For they say, for example, that the reason other things require a cause is that they have potentials that need actualization, whereas God, being pure actuality, has no potentials that could be actualized; or that the reason other things require a cause is that they are composite and thus require some principle to account for why their parts are conjoined, whereas God, being absolutely simple or non-composite, has no metaphysical parts that need conjoining; or that while a contingent thing requires a cause insofar as it has an essence distinct from its act of existence (and thus has to acquire its existence from something other than its own nature), a necessary being, which just is existence or being itself, need not acquire its existence from anything else; and so forth.

So, in the actual arguments of proponents of the idea of God as First Cause, there just is no self-contradiction or special pleading of the sort Russell’s objection requires. The arguments may or may not be open to other objections, but Russell’s objection seems either aimed at a straw man or simply to miss the point.

Now you suggest reading Russell’s objection as directed at the sort of argument in which “cause” means something like “explanation” (where the notion of an explanation is broader than the notion of an efficient cause, which is what is usually meant by “cause” these days). Thus read, Russell’s objection becomes:

If everything must have [an explanation], then God must have [an explanation]. If there can be anything without [an explanation], it may just as well be the world as God, so that there cannot be any validity in that argument.

But the trouble with this is that it does not save Russell from the charge that he was either attacking a straw man or missing the point. At best it just makes him guilty of attacking a different straw man or of missing a different point. For this reconstructed objection would be a good one only if proponents of First Cause arguments either insisted that everything has an explanation but then suddenly made an exception in the case of God, or if they denied that everything has an explanation but nevertheless arbitrarily insisted that the universe must have one while God need not. For in the first case they would be contradicting themselves while in the second case they would be engaged in special pleading.

But in fact defenders of First Cause arguments like the thinkers I named are doing no such thing. In fact they would agree that everything has an explanation, and they would not make any exception in the case of God. In their view, neither God’s existence nor the world’s existence is a “brute fact.” But the explanation of God’s existence, they would say, lies in his own nature, whereas the explanation of the existence of other things lies in their having an efficient cause. Nor is there any arbitrariness in their saying that God’s existence is explained by his own nature whereas the existence of other things requires an explanation in terms of some efficient cause distinct from them. For they would say, for example, that the reason other things require such a cause is that they are mixtures of actuality and potentiality, and thus need something to actualize their potentials, whereas God, being pure actuality, has no potentials needing actualization, and exists precisely because he just is actuality itself; or they would say that since other things have an essence distinct from their acts of existence, they need something outside their essence to impart existence to them, whereas God, whose essence just isexistence, need not derive existence from anything else but exists precisely because being itself is what he is; and so forth.

Now, other objections might be raised against these sorts of arguments and the metaphysics that underlies them. But they are simply not guilty either of contradicting themselves, or of making an arbitrary exception in God’s case to a general demand that things must have explanations, or of failing to give a reason for saying that God has a kind of explanation that other things do not. So, they are simply not at all subject to Russell’s objection even as you suggest we read it.