Edward Feser's Blog, page 82

May 25, 2015

D. B. Hart and the “terrorism of obscurantism”

Many years ago, Steven Postrel and I interviewed John Searle for Reason magazine. Commenting on his famous dispute with Jacques Derrida, Searle remarked:

Many years ago, Steven Postrel and I interviewed John Searle for Reason magazine. Commenting on his famous dispute with Jacques Derrida, Searle remarked: With Derrida, you can hardly misread him, because he's so obscure. Every time you say, "He says so and so," he always says, "You misunderstood me." But if you try to figure out the correct interpretation, then that's not so easy. I once said this to Michel Foucault, who was more hostile to Derrida even than I am, and Foucault said that Derrida practiced the method of obscurantisme terroriste (terrorism of obscurantism). We were speaking French. And I said, "What the hell do you mean by that?" And he said, "He writes so obscurely you can't tell what he's saying, that's the obscurantism part, and then when you criticize him, he can always say, 'You didn't understand me; you're an idiot.' That's the terrorism part."

Now, David Bentley Hart is hardly as obscure as Derrida, and I would hardly call him a “terrorist.” (Foucault’s expression here is characteristically over-the-top.) Still, I can’t help but think of Searle and Foucault’s description of Derrida’s method of dealing with his critics when reflecting on the way Hart tends to respond to his critics.

First example: Take Hart’s now notorious attack on natural law theory of two years ago. As I showed in my initial reply to Hart, there are a number of serious problems with that piece. But as I have also by now pointed out many times, the most serious -- indeed, the fatal problem -- is that Hart relentlessly conflates “new natural law” theory and “old natural law” theory. His central thesis, which he not only presented in his original article but has reiterated in several follow-up pieces, is that natural law theorists both (a) appeal to formal and final causes inherent in nature but also (b) are blithely unaware of the fact (or at least downplay the fact) that most of the modern readers they are trying to convince firmly reject the very idea of formal and final causes. And the trouble is that there are no natural law theorists of which this is true. For (a) is not true of “new” natural law theorists, and (b) is not true of “old” natural law theorists. Hart is thus attacking a straw man.

Certainly Hart has, in the original piece, in three different follow-up pieces now, and in two further brief references to the debate, failed to offer a single example -- not one -- of a natural law theorist whose work actually fits his description of natural law theory. Indeed, he has explicitly refused to name any names, even though doing so would instantly defuse the main objection his critics have raised against him.

(For the record, these follow-up pieces are: Hart’s first reply to his critics in his column in the May 2013 First Things, to which I responded at Public Discourse; Hart’s lengthy further response to his critics in the letters pageof the same issue, to which I responded here at the blog; and what he characterized as his final response in his August 2013 column in First Things, to which I also responded here at the blog. Hart then briefly revisited the debate in his column in the March 2015 First Things, to which I responded here; and he briefly referred to it yet again in his June/July 2015 First Things column, to which I recently responded at Public Discourse.)

Even more bizarrely, though Hart has addressed other objections head on, he has, in those three lengthy follow-up pieces and two briefer remarks -- five occasions total -- not even acknowledged, much less directly responded to, the central objection just summarized, even though it has been repeatedly raised against him. He could very easily say: “I have been accused of conflating new and old natural law theory, but here is why that charge is mistaken…,” or: “Let me give you a specific example of a natural law theorist who is guilty of doing what I say natural law theorists in general are guilty of.” But he doesn’t. Why not? It can’t be because he has judged that answering his critics is somehow not worth his time; again, he has revisited the debate five times now. So, obviously he does want to try to answer his critics. And yet he never acknowledges or directly responds to their central criticism. Why is that?

Then there is the obscurity in what Hart doessay in reply to his critics. If you read my responses, linked to above, to his three lengthier attempts to reply to those critics, you will see that I there show -- documenting my analysis with many quotes from Hart -- how difficult it is to find a clear and consistent position in what he says. As I demonstrate in those pieces, just when you think you’ve finally nailed down what Hart means, he says something else that conflicts with that reading. Hart himself confesses in one place to some “obscurity,” and in another that he “may have been guilty of a few cryptic formulations” and “should have been clearer.”

And yet despite admitting himself to being sometimes “obscure” and “cryptic,” and despite failing repeatedly even to acknowledge much less answer the main objection leveled against him -- where, if only he would do so, he might finally clarify things in a single stroke -- Hart claims that it is my criticismsof his remarks on natural law that are “confused,” “simplistic,” and guilty of “fallacies,” and that our dispute over natural law “largely involved Feser furiously thrashing away at what he imagined I was saying” (where the latter remark was embedded in the larger context of ad hominemremarks about my purportedly robotic and dogmatic adherence to “The System” of “Baroque neoscholasticism,” “manualism,” “two-tier Thomism,” etc.).

Now that, I submit, comes pretty close to what Foucault and Searle call “the method of… [the] terrorism of obscurantism.”

Second example: Hart’s March 2015 column in First Things is primarily devoted to the question of the relationship between faith and reason. As I noted in my March 13 blog post commenting on that column:

Hart objects to the charge that he is a fideist, arguing that both fideism and rationalism of the seventeenth-century sort are errors that would have been rejected by the mainstream of the ancient and medieval traditions with which he sympathizes. With that much I agree.

I also noted several other things Hart says in the column with which I agree, and indeed I said that they are “points whose importance cannot be overemphasized.”

I also noted, however, that certain other things Hart says there seem, whatever his intentions, to imply a kind of fideism. For example, he says that even reason “arises from an irreducibly fiduciary movement of the will” (emphasis added), and indicates that he rejects the view that reason is “capable of discerning first principles and deducing final conclusions without any surd of the irrational left over” (emphasis added). That certainly makes it sound as if he thinks that in all our attempts rationally to justify our beliefs, there is always at bottom some “surd of the irrational” and that it is “the will,” in an “irreducibly fiduciary movement,” which decides upon first principles. And that is a view of the sort that would commonly be regarded as a kind of fideism. Still, I did not say that Hart is a fideist, full stop. I said that his position is ambiguous and can be read in different ways.

Incidentally, you’ll find a similar ambiguity in Hart’s recent book The Experience of God. On the one hand, he argues (quite rightly in my view), that any materialist account of our rational thought processes can be shown to be self-undermining, and that the very logic of explanation when pushed through consistently leads inevitably to affirming the existence of a divine necessary being as the only possible explanation of why the world of contingent things exists. That certainly evinces a very optimistic view of what reason can accomplish vis-à-vis the dispute between theists and philosophical naturalists.

On the other hand, Hart also says in that book that he has “begun to vest less faith in certain forms of argument” (p. 84), and that it is good to “let all complexities of argument fall away as often as one can” in favor of a “moment of wonder, of sheer existential surprise” (p. 150). He suggests that “our deepest principles often consist in nothing more -- but nothing less -- than a certain way of seeing things” and that “every form of philosophical thought is itself dependent upon a set of irreducible and unprovable assumptions” (p. 294). He wants to remind us of “the limits of argument, and of the degree to which our most cherished certitudes are inseparable from our own private experiences” (Ibid.).

Does this mean that all attempted rational justifications come down at the end of the day to “private experiences,” “moments of wonder,” or the like? Is there, after all, no common ground by which the theist might rationally demonstrate to the naturalist that the latter’s position is mistaken? Are there just irreducibly different possible “movements of the will,” any of which involves a “surd of the irrational”? If so, why wouldn’t this amount to fideism? Or is there some other way to read Hart’s remarks here? The problem is not the way Hart answers these questions. The problem is that Hart doesn’t even addressthem, much less answer them, at least not in The Experience of God or in the column on faith and reason. It just isn’t clear what he would say.

Now, a reader recently called my attention to a recent combox discussion at Eclectic Orthodoxy, to which Hart contributed and in the course of which he made the following remark:

[W]e are all so prone to thinking in the rather arid categories of (for want of a better word) analytic correspondence that we regard the entire tacit dimension of knowledge (which is the foundation of all knowledge) as somehow either merely inchoate or merely emotional. If one is not careful, one ends up with the barren dialectic of “rationalism” or “fideism,” and one ends up like a certain popular Thomist I know of, unable to think in any other terms than that.

Well, I’m sure we’re all wondering who the “popular Thomist” in question is. But one good reason for thinking that it isn’t me -- or rather, for thinking that it shouldn’tbe me -- is that my views simply don’t correspond to those attributed by Hart to this “popular Thomist.” For one thing, and as I explicitly said in my post on Hart’s faith and reason column, like him I reject what he called, in the column, “the Scylla and Charybdis of ‘rationalism’ and ‘fideism’ [which] seems like such a tarnished relic of the seventeenth century (or thereabouts).” For another thing, I have written quite a bit, and quite sympathetically, on the “tacit dimension of knowledge.” (See, for example, my defense of Burke’s and Hayek’s account of the indispensable role that tradition, habit, and inexplicit rules play in moral and social knowledge.) It’s just that I don’t think that this tacit knowledge has anything to do with “movements of the will,” a “surd of the irrational,” or the like.

Now, if some man assures us with vehemence that he is not a bachelor, but also denies with equal vehemence that he is or ever has been married, never explains to us how both these things can be true but also dismisses with contempt our suggestion that maybe he really is a bachelor after all (accusing us of applying “arid categories” and a “barren dialectic,” no less)… if someone does all that, then weare hardly the ones being unreasonable. Nor would it be reasonable for his defenders breathlessly to protest “But he said he’s not a bachelor! You’re not interpreting him charitably!”

Similarly, though Hart insists that he is not a fideist, but nevertheless also says things that would normally be taken to be fideistic positions, and does not explain how he can reconcile these claims while at the same time dismissing his critics as being simplistic and misunderstanding him… well, once again, that seems pretty close to what Foucault and Searle call “the method of… [the] terrorism of obscurantism.”

Diagnosis: So, just what is Hart’s deal, anyway? Why this resort to obscurantisme terroriste? Let’s consider the following:

Item one: As a stylist and a thinker, Hart’s strengths and predilections lie in rhetoric rather than rigor, and he has a clear animus against writers of the opposite tendency. Hence his confessionthat he “delight[s] in casual abuse of Thomists,” and his regular glib dismissals of anything he takes to smack of “neoscholasticism.” Hence his equally condescending remarks about analytic philosophers in The Experience of God. Hence his explicit refusal, in the same book, actually to set out and defend in any detail the arguments against materialism and for the existence of God that he endorses. Explicit, step-by-step arguments, the dispassionate weighing of lists of possible objections and possible replies to those objections, the making of fine distinctions and careful definitions of key terms, and so forth -- the sort of thing typical of a Scholastic or an analytic philosopher -- are not the sort of thing for which Hart seems to have much patience.

What Hart really likes are grandiloquent pronouncements and the big picture. A sense of his style and interests is given by the titles and subtitles you’ll typically find in a Hart book or article: “Being, Consciousness, Bliss,” “The Veil of the Sublime,” “The Mirror of the Infinite,” “A Glorious Sadness,” “The Practice of the Form,” “The Terrors of Easter,” “The Doors of the Sea,” “The Violence of Metaphysics and the Metaphysics of Violence”… that kind of stuff. The sort of thing sure to prompt an “Oooh!” or an “Aaaaah!” as you dip into Hart while sipping brandy. Grand Rhetoric and Grand Themes, and hold the argumentational minutiae please. That’s Hart’s shtick, and he’s shtickin’ with it. You can see how an analytical Thomist who posts comic book panels on his blog might get under his skin.

Item two: Whether or not you want to call it “fideism,” the view that what we take to be rational argument always comes down at the end of the day to “movements of the will,” “personal experiences,” “ways of seeing things,” “moments of wonder,” and the like tends inevitably to put the accent on the character of a person giving an argument rather than on the argument itself. If your conclusions are mistaken, perhaps that’s because you haven’t had a “moment of wonder,” or have had the wrong “personal experiences,” so that your overall “way of seeing things” is off kilter. Or perhaps the “movements of your will” are simply corrupt.

Of course, sometimes the problem really is with the character of the person giving an argument. Sometimes people really are arguing in bad faith. Furthermore, Hart’s view doesn’t entail that all errors are a consequence of some deficiency of character. It is consistent with some errors just being a result of mistaken inferences or getting the facts wrong.

Still, if you are someone who is inclined to emphasize “the limits of argument,” and the role that “movements of the will” and the having of the right “personal experiences” play in ensuring a sound overall “way of seeing things,” then there is bound to be a strong temptation to jump too quickly to the ad hominem, to look straightaway for a deficiency in your critics and not just in their criticisms.

And Hart does indeed sometimes suggest that deficiencies of background experience or personal motivation underlie his critics’ resistance to his views. Hence, in his most recent response to me in First Things, Hart laments that “Feser [was not] fortunate enough to be catechized into Orthodoxy rather than The System.” And rather than focusing on the actual arguments I gave against there being animals in Heaven (which was the subject of our dispute), he put the emphasis on what he alleged were my true motives for taking the view I did (viz. to uphold “The System”).

Kidding on the square, Hart also suggests in The Experience of God that a preference for analytic philosophy reflects “some peculiarity of temperament or the tragic privations of a misspent youth” (p. 344).

Furthermore, in one of his replies to critics of his article on natural law, Hart says:

I am in the end quite happy for believers in natural law theory to continue plying their oars, rowing against the current (so long as they do so in keeping with classical metaphysics), but I do not think they are going to get where they are heading; so I shall just watch from the bank for a while and then wander off to the hills (to look for saints and angels).

And in reply to one critic in particular, he says:

As to what “other approach” he should take to “modern moral life,” I encourage Mr. Kainz to pursue classical natural law theory (which was not the topic I addressed), if he likes. The Great Commission also comes to mind. (Do what you think best.)

The insinuation is obvious. If what motivates you is Christ’s Great Commission and if you value the teachings of saints and angels over those of worldly men, then you’ll agree with Hart. And if you don’t agree with Hart, well…

(I say more about these two passages in my analysis from two years ago of the piece from which they are quoted.)

So, with this in mind, consider the scenario in which Hart not infrequently finds himself. A Grand Man makes a Grand Point about a Grand Theme, in Grand Style. And then some yutz analytic philosopher or neoscholastic comes along logic-chopping and ruining the moment. The temptation is strong to conclude that there’s got to be something wrong with the critic and not just with whatever his silly criticism is. He just hasn’t got the character or education to see all the Grandness.

Conclusion: On the one hand, then, we have a strong predilection for rhetoric and an impatience with rigorous argumentation. That’s a recipe for the first half of obscurantisme terroriste. And on the other hand, we have a strong tendency to look for volitional, experiential, moral, and spiritual deficiencies -- personal deficiencies -- in those who have the wrong opinions. That’s a recipe for the second half of obscurantisme terroriste. Thus, a temptation to deal with critics via what Searle and Foucault call “the method of… [the] terrorism of obscurantism” is, I would suggest, bound to be an occupational hazard of the Hart style of theology.

And this is an analysis even Hart should love. “The Terrorism of Obscurantism” sounds just like a Hart chapter title, no?

Published on May 25, 2015 11:16

May 20, 2015

Stupid rhetorical tricks

In honor of David Letterman’s final show tonight, let’s look at a variation on his famous “Stupid pet tricks” routine. It involves people rather animals, but lots of Pavlovian frenzied salivating. I speak of David Bentley Hart’s latest contribution, in the June/July issue of First Things, to our dispute about whether there will be animals in Heaven. The article consists of Hart (a) flinging epithets like “manualist Thomism” and “Baroque neoscholasticism” so as to rile up whatever readers there are who might be riled up by such epithets, while (b) ignoring the substance of my arguments. Pretty sad. I reply at Public Discourse.Previous installments of my various exchanges with Hart can be found here.

In honor of David Letterman’s final show tonight, let’s look at a variation on his famous “Stupid pet tricks” routine. It involves people rather animals, but lots of Pavlovian frenzied salivating. I speak of David Bentley Hart’s latest contribution, in the June/July issue of First Things, to our dispute about whether there will be animals in Heaven. The article consists of Hart (a) flinging epithets like “manualist Thomism” and “Baroque neoscholasticism” so as to rile up whatever readers there are who might be riled up by such epithets, while (b) ignoring the substance of my arguments. Pretty sad. I reply at Public Discourse.Previous installments of my various exchanges with Hart can be found here.

Published on May 20, 2015 20:11

May 12, 2015

Lewis on transposition

C. S. Lewis’s essay “Transposition” is available in his collection

The Weight of Glory

, and also online here. It is, both philosophically and theologically, very deep, illuminating the relationship between the material and the immaterial, and between the natural and the supernatural. (Note that these are different distinctions, certainly from a Thomistic point of view. For there are phenomena that are immaterial but still natural. For example, the human intellect is immaterial, but still perfectly “natural” insofar as it is in our nature to have intellects. What is “supernatural” is what goes beyond a thing’s nature, and it is not beyond a thing’s nature to be immaterial if immateriality just is part of its nature.)By “transposition,” Lewis has in mind the way in which a system which is richer or has more elements can be represented in a system that is poorer insofar as it has fewer elements. The notion is best conveyed by means of his examples. Consider, for instance, the way that the world of three dimensional colored objects can be represented in a two dimensional black and white line drawing; or the way that a piece of music scored for an orchestra might be adapted for piano; or the way something said in a language with many words at its disposal might be translated into a language containing far fewer words, if the relevant latter words have several senses.

C. S. Lewis’s essay “Transposition” is available in his collection

The Weight of Glory

, and also online here. It is, both philosophically and theologically, very deep, illuminating the relationship between the material and the immaterial, and between the natural and the supernatural. (Note that these are different distinctions, certainly from a Thomistic point of view. For there are phenomena that are immaterial but still natural. For example, the human intellect is immaterial, but still perfectly “natural” insofar as it is in our nature to have intellects. What is “supernatural” is what goes beyond a thing’s nature, and it is not beyond a thing’s nature to be immaterial if immateriality just is part of its nature.)By “transposition,” Lewis has in mind the way in which a system which is richer or has more elements can be represented in a system that is poorer insofar as it has fewer elements. The notion is best conveyed by means of his examples. Consider, for instance, the way that the world of three dimensional colored objects can be represented in a two dimensional black and white line drawing; or the way that a piece of music scored for an orchestra might be adapted for piano; or the way something said in a language with many words at its disposal might be translated into a language containing far fewer words, if the relevant latter words have several senses.As these examples indicate, in a transposition, the elements of the poorer system have to be susceptible of multiple interpretations if they are to capture what is contained in the richer system. In a pen and ink drawing, black will have to represent not only objects that really are black, but also shadows and contours; white will have to represent not only objects that really are white, but also areas that are in bright light; a triangular shape will represent not only two dimensional objects, but also three dimensional objects like a road receding into the distance; and so on. In an orchestral piece adapted for piano, the same notes will have to stand for those that would have been played on a flute and those that would have been played on a violin. In a translation into a less rich language, words that have one meaning in one context will have to bear a different meaning in another context. In general, the relationship between the elements of a richer system and the elements of the poorer system into which it is transposed is not one-to-one, but many-to-one.

You cannot properly understand a transposition unless you understand something of both sides of it, as Lewis illustrates with a vivid example. He asks us to consider a child born to a woman locked in a dungeon, who tries to teach the child about the outside world via black and white line drawings. Through this medium “she attempts to show him what fields, rivers, mountains, cities, and waves on a beach are like” (p. 110). For a time it seems that she is succeeding, but eventually something the child says indicates that he supposes that what exists outside the dungeon is a world filled with lines and other pencil marks. The mother informs the child that this is not the case:

And instantly his whole notion of the outer world becomes a blank. For the lines, by which alone he was imagining it, have now been denied of it. He has no idea of that which will exclude and dispense with the lines, that of which the lines were merely a transposition… (Ibid.)

(Though Lewis does not note it, the parallel with Plato’s Allegory of the Cave is obvious.)

Now, transpositions in Lewis’s sense do not exist merely where we are trying to represent something (in words, drawings, music, or whatever). Lewis points out that a similar relationship holds between emotions and bodily sensations. The very same sensation -- a twinge of excitement felt in the abdomen around the diaphragm, say -- may in one context be associated with romantic passion and be taken to be pleasant, and in another context be associated with a feeling of distress and be taken to be unpleasant. Very different emotions can be transposed, as it were, onto one and the same bodily sensation in something like the way very different meanings might be associated with the same word. And as with the other sorts of transposition, you will not understand what is going on if you look to the lower medium alone. In this case, you will not know what emotion is being felt, or even what an emotion is, if you look to the bodily sensation alone.

As Lewis points out, the notion of transposition is useful for understanding the relationship between mind and matter and the crudity of the errors made by materialists. Lewis, like Aristotelians and Thomists, is happy to acknowledge that “thought is intimately connected with the brain,” but, also like them, he insists that the conclusion “that thought therefore is merely a movement in the brain is… nonsense” (p. 103, emphasis added). As I have argued many times (at greatest length and most systematically here), there is no way in principle that the conceptual content of our thoughts can be accounted for in materialist terms, because concepts have an exact or determinate content that no material representation or system of representations can have, and a universal reference that no material representation or system of representations can have. The relationship between thought and brain activity is accordingly somewhat analogous to the relationship between the meaning of a written sentence and the physical properties of the ink marks that make up that sentence. If the ink marks are damaged or destroyed, it will be difficult or impossible for the sentence to convey its meaning. But of course it doesn’t follow that the meaning of the sentence is reducible to or knowable from the physical properties of the ink marks alone. Similarly, if the brain is damaged, then thought is impaired, but it doesn’t follow that thought is reducible to brain activity. (I do not say that the analogy is perfect, only that it is suggestive.)

Now, suppose someone noted that sentences are always embodied in some physical medium or other -- ink marks, pixels, sound waves, etc. -- and concluded that the meaning of a sentence must therefore be reducible to or deducible from the physical and chemical properties of ink marks, pixels, sound waves, etc. alone. He would be conflating the two sides of a transposition, and in particular trying to reduce the richer system (the system of meanings) to the poorer system (the system of physical marks or noises). He would be like the child in the dungeon who thinks that the outside world must be “nothing but” what can be captured in black and white line drawings, or like someone who thinks that the richness of an emotional state can be reduced to a mere bodily sensation, or like someone who thinks that the most complex orchestral piece must really be “nothing but” whatever noises can be made on a piano.

Now, anyone who seriously thinks that thought can be reduced to brain activity, or who suggests (as an eliminative materialist, as opposed to a reductive materialist, would) that the notion of thought can be eliminated entirely and replaced by the notion of brain activity, is like that. Actually, he is much worse than that. He is not like the child in the dungeon who has never seen the outside world and thus makes an innocent, though egregious, error in supposing that it must be reducible to what can be captured in a line drawing. The materialist is more like the woman, if we imagine that for some bizarre reason she somehow talks herself into believing that the outside world contains nothing more than what is in a black and white pencil drawing -- even though she has actually seen the outside world and thus knows better. The materialist knows full well that thought is real, and that the conceptual content of thought is as different from the physical properties of brain activity -- electrochemical properties, causal relations, etc. -- as apples are from oranges. It is only an ideological fixation on one side of the transposition involved here that leads him to insist otherwise. Suppose the reason the woman fell into a delusion like the one in question is because she had spent so long a time in the dungeon that she came to love it, and could barely remember the outside world. The materialist has so fixated upon and fallen in love with the less rich side of the transposition (brain activity) that, at least in his philosophical moments, he can barely keep in mind what the richer side (thought) is really like.

This error of conflating the two sides of a transposition is rife within reductionist philosophical theorizing. Think, for example, of Hume’s claim that concepts are “nothing but” impressions or mental images, or Berkeley’s claim that physical objects are “nothing but” collections of the perceptions we have of them, or subjectivist theories of value that claim that judgments about what is good or bad are “nothing but” expressions of various sentiments. Whenever we consciously entertain some concept, we tend to form a mental image of some sort. For example, when we entertain the concept triangularity, we form a mental image of a triangle or of the written or spoken word “triangle.” But it doesn’t follow that the concept is to be identified with such mental images, and indeed (and contra Hume) it cannot be. The concept, being completely abstract and universal, is richer than any mental image or set of mental images, which are always concrete and particular. What the mind does when it makes use of mental imagery as an aid to thought is to transpose, in Lewis’s sense, the richer conceptual order into the poorer order of mental imagery. Similarly, in perception, the mind transposes the richness of physical substances (the full nature of which can be grasped only by the intellect and not by sensation or imagination) into the poorer medium of sense images. Berkeley’s idealism in effect collapses that richer order into the poorer one. And in conscious acts of moral judgment, our grasp of something as good is associated with a feeling of approval, while our judgment that something is bad is associated with a feeling of disapproval. The mind transposes the former, cognitive order into the latter, and very different, affective order. The subjectivist theorist of value makes the mistake of collapsing the former into the latter.

As Lewis notes, however, it isn’t just materialists and other reductionists who are guilty of confusion where transpositions are concerned. Religious believers are prone to it as well to the extent that they collapse the supernatural into the natural. For example, Lewis notes the danger of confusing one’s emotional state with one’s spiritual state. Obviously there is a rough and ready correlation here. Being close to God and morally upright is often associated with a feeling of well-being. But feelings are fickle things and subject to distortion. A scrupulous person takes his feelings of guilt to be a sign that he has sinned, when in fact he has not. A lax person takes the absence of any feelings of guilt as evidence that he has not sinned, when in fact he has. Highly emotional styles of worship seem to some to be evidence of genuine devotion, whereas more sedate forms of worship might seem spiritually arid. But the former sort of devotion can also be superficial and fleeting, and the latter deeper and more enduring. Pop spirituality tells us “Don’t think, feel!” but the reverse is much closer to the truth.

(Notice that I say only that it is closer to the truth, not that it is the truth, full stop. I do not for a moment deny that feelings have a role in the religious life, and I think Lewis would not deny it either. We are, after all, feeling creatures by nature, not bloodless Cartesian intellects trapped in bodies. The point is just that feelings are the lower, poorer side of the transposition, whereas the intellect -- which alone can ultimately judge one’s true spiritual state -- is the higher, richer side. Here as in every other aspect of life, the affective tail must not be allowed to wag the cognitive dog.)

Lewis also notes how religious people are prone to mistake the earthly images of Heaven for the real thing, and sometimes feel let down when they are told that this is a mistake. How could Heaven be eternal bliss without eating, drinking, and (my example, not Lewis’s) playing Frisbee with Fido? Deleting such earthly pleasures from our picture of Heaven seems to leave nothing in its place. Heaven comes to seem arid, bleak, and boring. But this is precisely the wrong lesson to draw, comparable to the error the child in the dungeon makes when he is told by his mother that the world outside the dungeon lacks pencil lines. As Lewis writes:

The child will get the idea that the real world is somehow less visible than his mother’s pictures. In reality it lacks lines because it is incomparably more visible.

So with us. “We know not what we shall be”; but we may be sure we shall be more, not less, than we were on earth. Our natural experiences (sensory, emotional, imaginative) are only like the drawing, like pencilled lines on flat paper. If they vanish in the risen life, they will vanish only as pencil lines vanish from the real landscape, not as a candle flame that is put out but as a candle flame which becomes invisible because someone has pulled up the blind, thrown open the shutters, and let in the blaze of the risen sun. (pp. 110-11)

Descriptions of Heaven that make use of earthly images are transpositions of a higher, richer order into a lower, poorer one. The religious believer who cannot understand how Heaven can lack earthly delights is like the materialist who cannot understand how thought could be more than brain activity, or the subjectivist ethical theorist who cannot understand how judgments of moral goodness and badness can be anything more than the expression of feelings.

I would say that a similar mistake is made by many of those who resist classical theism in favor of the more anthropomorphic “theistic personalist” conception of God. When told by Thomists that we have to understand language about God in an analogical sense, they think that this entails thinking of God in a cold, abstract, and impersonal way. (One mistake they sometimes make is to think that the Thomist is saying that descriptions of God are merely “metaphorical.” That is notwhat the Thomist is saying. Not all analogical use of language is metaphorical. The Thomist takes talk about God’s power, knowledge, goodness, etc. to be literal, and thus not metaphorical. The claim is rather that such talk is not to be understood in a univocal way. For discussion of the Thomist theory of analogy, see pp. 256-63 of Scholastic Metaphysics .)

In fact, to think of the God of classical theism as cold, abstract, and impersonal is as clueless as the child in the dungeon thinking that the world outside must be very cold and abstract if it does not contain the pencil lines he sees in his mother’s drawings. Just as the world outside the dungeon is in fact far morewarm and concrete than the pencil drawings, so too is the God of classical theism infinitely more “personal” than the lame man-writ-large “God” of theistic personalism. The theistic personalist is like the boy who comes to prefer the drawings to ever leaving the dungeon, or the like the denizen of Plato’s cave who thinks it insane to believe tales of a world more real than the shadows on the wall. Or if you prefer a more earthy biblical analogy, he is like Esau, trading his birthright for a mess of pottage and thinking he’s gotten the better deal.

Published on May 12, 2015 14:17

May 8, 2015

A linkfest

My review of Charles Bolyard and Rondo Keele, eds.,

Later Medieval Metaphysics: Ontology, Language, and Logic

appears in the May 2015 issue of Metaphysica.

My review of Charles Bolyard and Rondo Keele, eds.,

Later Medieval Metaphysics: Ontology, Language, and Logic

appears in the May 2015 issue of Metaphysica. At Thomistica.net, Thomist theologian Steven Long defends capital punishment against “new natural lawyer” Chris Tollefsen.

In the Journal of the American Philosophical Association, physicist Carlo Rovelli defends Aristotle’s physics.

At Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews, Christopher Martin reviews Brian Davies’ Thomas Aquinas's Summa Theologiae: A Guide and Commentary .John Searle’s new book Seeing Things as They Are is reviewed in The Weekly Standard.

At The Critique, Graham Oppy on academic atheist philosophers of the last 60 years.

The Institute of Thomistic Philosophy will hold its first Aquinas Summer School in August of 2016. Details here.

What makes Pope Francis tick? Ross Douthat investigates at The Atlantic.

Irish atheists disassociate themselves from New Atheist buffoon P. Z. Myers.

James Franklin’s An AristotelianRealist Philosophy of Mathematics is reviewed in Philosophia Mathematica. (Full text here.) And there’s lots of content to be found at Franklin’s Academia.edu website as well as at his university website.

Conservative philosopher Roger Scruton is interviewed at The Spectator.

The New York Review of Books on F. A. Hayek on John Stuart Mill.

Philosopher Anthony McCarthy discusses gender ideology in a talk at the Pontifical University of John Paul II in Krakow.

The Washington Post reports on the indomitable Ryan T. Anderson’s fight against “same-sex marriage.” Predictably, the forces of reason and tolerance don’t want to reason with or tolerate him.

Philosopher of physics Tim Maudlin on why physics needs philosophy.

At The Stream, Catholic writer John Zmirak defends capital punishment.

At Vox, Alex Abad-Santos reports on how he attended the 29-hour Marvel movie marathon and emerged “a broken man.”

The European Conservative magazine has a website.

Some friends of this blog debate classical theism and theistic personalism. On the theistic personalist side there’s Dale Tuggy (hereand here), and on the classical theist side Bill Vallicella (here, here, and here) and Fr. Aidan Kimel (here, here, and here).

Bonus audio: Tuggy interviews Vallicalla in two parts, hereand here.

And on video: Fr. Robert Barron on Aquinas and why the New Atheists are right.

Published on May 08, 2015 11:42

May 3, 2015

Animal souls, Part II

Recently, in First Things, David Bentley Hart criticized Thomists for denying that there will be non-human animals in Heaven. I responded in an article at Public Discourse and in a follow-up blog post, defending the view that there will be no such animals in the afterlife. I must say that some of the responses to what I wrote have been surprisingly… substandard for readers of a philosophy blog. A few readers simply opined that Thomists don’t appreciate animals, or that the thought of Heaven without animals is too depressing.Do I really need to explain what is wrong with this? Apparently I do. First, for one to deny that there will be non-human animals in the afterlife simply doesn’t entail that one must not appreciate the beauty of a horse or the cleverness of a dolphin or be capable of affection for dogs, cats, or other pets. That’s a blatant non sequitur. Second, that some might find the thought of Heaven without animals upsetting simply doesn’t entail that there will be animals in Heaven. That’s a subjectivist fallacy -- a fallacy of mistaking one’s desire for something to be true for a reason to think it is true. Third, I gave arguments in defense the claims that there will not be non-human animals in Heaven, and that this won’t bother us in the least when we’re in Heaven. A rational and grown-up response would be to try to show what, if anything, is wrong with the arguments, rather than to pout and accuse Thomists of being mean.

Recently, in First Things, David Bentley Hart criticized Thomists for denying that there will be non-human animals in Heaven. I responded in an article at Public Discourse and in a follow-up blog post, defending the view that there will be no such animals in the afterlife. I must say that some of the responses to what I wrote have been surprisingly… substandard for readers of a philosophy blog. A few readers simply opined that Thomists don’t appreciate animals, or that the thought of Heaven without animals is too depressing.Do I really need to explain what is wrong with this? Apparently I do. First, for one to deny that there will be non-human animals in the afterlife simply doesn’t entail that one must not appreciate the beauty of a horse or the cleverness of a dolphin or be capable of affection for dogs, cats, or other pets. That’s a blatant non sequitur. Second, that some might find the thought of Heaven without animals upsetting simply doesn’t entail that there will be animals in Heaven. That’s a subjectivist fallacy -- a fallacy of mistaking one’s desire for something to be true for a reason to think it is true. Third, I gave arguments in defense the claims that there will not be non-human animals in Heaven, and that this won’t bother us in the least when we’re in Heaven. A rational and grown-up response would be to try to show what, if anything, is wrong with the arguments, rather than to pout and accuse Thomists of being mean.Did I really need to explain that?

But there were more serious objections too. For example, some readers pointed out that even if, as Thomists argue, the specific individual animals we know in this life cannot survive into the afterlife, it doesn’t follow that there will be no animals at all in heaven. Now, this is true as far as it goes, though it’s hard to see how it could satisfy the emotions that lead many to want to believe there will be animals in Heaven. If what you’re worried about is that you’ll never see your beloved dog Spot again, what does it matter if there’ll be some other dog in heaven, even one who looks and acts a lot like Spot? You’d still never see Spot himself again.

But leave that problem aside, for there is another problem with the objection in question. Even if there could in theory be non-human animals in Heaven, why should we suppose that there willin fact be any? Some readers appealed to biblical passages in support of this supposition. Hart did the same thing in his article, even accusing Thomists of placing the authority of Aquinas over that of scripture. What he had in mind are passages like the reference in Isaiah 11 to wolves lying down with lambs, etc.

But as Hart well knows, it is no use appealing to purported proof texts from biblical passages that are highly poetical in style, as that passage from Isaiah certainly is. Otherwise we’d have to say, absurdly, that God literally has eyes and eyelids (as Psalm 11:4 would imply on a literal reading), nostrils and lungs with which he breathes (Job 4:9), and so on. The same passage from Isaiah also speaks of babies and children frolicking with the animals. So are we to suppose that there will be babies born, and children raised, in Heaven? Yet as I pointed out in my Public Discourse article, Christ tells us that those in Heaven “neither marry nor are given in marriage” (Matthew 22:30). So where are all these babies and children supposed to come from? (I imagine Hart would agree that fornication wouldn’t be permissible in Heaven any more than it is in this life.)

Obviously, the biblical references to animals, no less than to babies, children, and divine eyelids and nostrils, are intended as merely poetical descriptions. They give us no reason to think that there will literally be animals in Heaven.

And what would be the point of there being non-human animals in Heaven? It can’t be that we will miss the animals otherwise, because if we’d miss any animals at all, it would be those to which we are especially attached in this life. And again, the Thomist argues on metaphysical grounds that those particular animals certainly can’t exist in the afterlife. Furthermore, as I pointed out in the Public Discourse article, Christ’s own teaching implies that we won’t miss romance, lovemaking, and the psychological and bodily pleasures that go along with them. Those are not only much more intense pleasures than those we get from interaction with animals, but they are much higher pleasures, because of their interpersonal character. Sexual love involves a unique fusion of our corporeal nature with our higher intellectual and social nature, by which the spiritual union of two rational souls can find an intimate bodily expression. If we won’t miss even that, then it is quite absurd to think we’ll miss playing Frisbee with Spot.

Some readers suggested that the reason there would have to be animals in the afterlife is that animals are good, and that God would not fail to preserve what is good. But there are a couple of serious problems with this argument. First, it would prove too much. In particular, it would entail that God will preserve forever anything that is good. But we know that that is not the case. Again, marriage is good, but we have it on Christ’s own authority that marriage will not exist in the afterlife. So, if this good will not be preserved in Heaven, why would a lower good like non-human animals be preserved?

Second, the supposition that non-human animals constitute a good too great not to exist in Heaven seems to rest on sentimentality borne of contemplating too selective a diet of examples. One meditates on the beauty of a horse or the faithfulness of a Labrador and asks “How could these creatures not exist in Heaven?” But suppose instead we meditate on a fly as it nibbles on a pile of fecal matter, or a tapeworm as it works its way through an intestine, or a botfly larva pushing its breathing tube through the human skin in which it has embedded itself, or lice or ticks or bacteria or any of the many other repulsive creatures that occupy our world alongside horses, dogs, and the like. These creatures are, in their own ways, no less good than the ones we are prone to sentimentalize. But one suspects that those who insist that horses and dogs will exist in Heaven would be less certain that these other creatures will make it. Flies munching on feces just doesn’t seem heavenly. But what principled reason could one give for the judgment that there will be dogs but not flies in Heaven, if the purported reason for supposing that the former will be there is that they are good and God will forever preserve whatever is good?

Nor is this merely a matter of competing intuitions about the relative goodness of different animals (and appeal to intuition is not an argument strategy I would ever recommend). Which brings me to a third point. Given their nature, the good of living things is achieved at the expense of the good of other creatures. It’s bad for the gazelle when the lion kills it, but it’s good for the lion. It’s bad for the lamb when a tapeworm gets into its intestines, but it’s good for the tapeworm. It’s bad for an animal when tuberculosis bacteria infect its lungs, but it’s good for the bacteria. And so forth.

Of course, some will appeal once again to the biblical passage about the wolf lying down with the lamb, arguing that God will miraculously cause creatures to survive without having to harm other creatures in the process. So, will the tapeworm also lie down with the lamb? Will the tubercle bacillus lie down with the lung? But what on earth will tapeworms and tuberculosis bacteria be doing for eternity if they can’t get themselves into any other creature’s intestines or lungs, respectively? What would be the point of forever keeping these things in existence when they would be prevented from acting in accordance with their nature and thus prevented from realizing what is good for them?

It is no good to respond that God will changethe natures of these things so that the activities in question won’t any longer be good for them. This is muddleheaded, because the nature of a thing is what makes it the kind of thing it is, so that if you “change” its nature, you’re changing the kind of thing it is. Hence if you “change the nature” of a tapeworm so that it no longer is naturally oriented toward invading intestines, you’re not really talking about tapeworms anymore, but some other kind of thing that only superficially resembles tapeworms. In which case it isn’t really tapeworms that God would be preserving forever after all -- which defeats the whole purpose of the argument that God will preserve whatever is good.

So, the biblical passages in question, which are highly poetical anyway, should not be taken to be literal descriptions of the afterlife, any more than talk of God’s breath or nostrils should be taken literally. And thus there simply are no good scriptural arguments, any more than there are good philosophical arguments, for judging that non-human animals will exist in the afterlife.

Published on May 03, 2015 10:51

April 27, 2015

Animal souls, Part I

Here’s a postscript, in two parts, to my recent critique in Public Discourse of David Bentley Hart’s case for there being animals in heaven. In this first part, I discuss in more detail than I did in the original article Donald Davidson’s arguments for denying that animals can think or reason in the strict sense. (This material was originally supposed to appear in the Public Discourse article, but the article was overlong and it had to be removed.) In the second part, I will address some of the response to the Public Discourse article. Needless to say, those who haven’t yet read the Public Discoursearticle are urged to do so before reading what follows, since what I have to say here presupposes what I said there.For the Thomist, it is because human beings are rational animals that our souls can survive the deaths of our bodies, since (as the Thomist argues) rational or intellectual powers are essentially incorporeal. Non-rational animals lack these incorporeal powers, so that there is nothing in them that can survive the deaths of their bodies. That is why there is not, and cannot be, any afterlife for non-human animals.

Here’s a postscript, in two parts, to my recent critique in Public Discourse of David Bentley Hart’s case for there being animals in heaven. In this first part, I discuss in more detail than I did in the original article Donald Davidson’s arguments for denying that animals can think or reason in the strict sense. (This material was originally supposed to appear in the Public Discourse article, but the article was overlong and it had to be removed.) In the second part, I will address some of the response to the Public Discourse article. Needless to say, those who haven’t yet read the Public Discoursearticle are urged to do so before reading what follows, since what I have to say here presupposes what I said there.For the Thomist, it is because human beings are rational animals that our souls can survive the deaths of our bodies, since (as the Thomist argues) rational or intellectual powers are essentially incorporeal. Non-rational animals lack these incorporeal powers, so that there is nothing in them that can survive the deaths of their bodies. That is why there is not, and cannot be, any afterlife for non-human animals.The telltale mark of the difference between a rational animal and a non-rational animal is language. Here some distinctions need to be made, because the term “language” is often used indiscriminately to refer to very different sorts of phenomena. Karl Popper distinguished four functions of language: the expressive function, which involves the outward expression of an inner state; the signaling function, which adds to the expressive function the generation of a reaction in others; the descriptive function, which involves the statement of a complete thought of the sort that might be expressed in a declarative sentence; and the argumentativefunction, which involves the statement of an inference from one thought to another. Some non-human animals are capable of the first two functions, and in that sense might be said to have “language.” But the latter two functions involve the grasp of concepts, and human beings alone posses language of the sort which expresses concepts, thoughts, and arguments.

You don’t have to be a Thomist to see this. Donald Davidson presented an influential set of arguments to the effect that thought and language go hand in hand, so that no creature which lacks language (in the relevant sense of “language”) can be said to think or reason in the strict sense. (See Davidson’s essays “Thought and Talk” and “Rational Animals.”) Hence, suppose a dog hears someone jangling some keys outside the door and starts wagging its tail and jumping about excitedly. A natural way to describe what is going on is to say that the dog thinks that its master is home. If what this amounts to is (say) merely that the sound of the keys jangling triggers in the dog’s consciousness a visual image of the master walking in the door, which in turn generates a feeling of excitement, then the Thomist (and, presumably, Davidson) are happy to agree. But what the dog does not have is a thought in the sense in which a human being might have the thought that the master is home. That is to say, the dog does not have the concept “master” or the concept “home,” and thus lacks any mental state with the conceptual contentof the thought that “The master is home.”

Davidson puts forward a number of considerations in support of this judgment. (What follows is my own way of stating Davidson’s points -- perhaps he would not agree with every aspect of my formulations.) Consider first that for the dog to have a thought in the sense of an internal state with conceptual content, there must be some specificcontent that the thought has. For example, it will be a thought with the content that the master is home -- as opposed, say, to a thought with the content that the man who is the father of the children who live in this house is home, or a thought with the content that the man who goes to work for eight hours every weekday is home. Now if the dog had language, there would be a way to make sense of his thought’s having the first content rather than the others. The dog might utter the sentence “The master is home” but not the sentences corresponding to the other thought contents, or it might assent to the sentence “The master is home” but not to the others (if, for example, it knew that the man in question is his master, but did not know either that this man is the father of the children or that he goes to work when he is away from the house). In the absence of such a linguistic criterion, though, it is hard to see how there could be a fact of the matter about which specific content the dog’s thought has. And thus it is hard to see how it really could have a thought with a specific conceptual content.

A second consideration is this. Crucial to having the capacity for thought is having the capacity for believing something -- for taking it to be true that the world is this way rather than that. There are other kinds of thoughts, such as desires and intentions, but they presuppose belief. For example, you can intend to have pizza for dinner only if you believe that there is, or at least could be, such a thing as pizza. Now, to have a belief, in Davidson’s view, entails having the concept of belief. For you cannot believe that it is raining outside without also believing that it is not the case that it is not raining outside. That is to say, to believe that it is raining outside entails believing that the belief that it not raining outside is false. But to know the difference between true belief and false belief presupposes having the concept of believing something.

Now, Davidson argues further that to have the concept of believing something entails having language. For, again, to have the concept of believing something is to have the concept of a state which could represent the world either truly or falsely. That entails being able to distinguish between a content of a belief which represents things correctly and a content which represents them falsely. For instance, what makes the belief that the earth is spherical a true belief and the belief that the earth is flat a false belief is that the content of the former represents things accurately and the content of the latter represents things falsely. But to be able to grasp the difference between these contents is just to grasp the difference between, on the one hand, the statement we might express linguistically in a sentence like “The earth is spherical” and, on the other, the statement we might express in a sentence like “The earth is flat.”

Now, if to be capable of thought entails having beliefs, and if having beliefs entails having the concept of believing something, then to be capable of thought entails having the concept of believing something. And if having the concept of believing something entails having language, then being capable of thought entails having language. In that case, Davidson concludes, any creature that lacks language also lacks the capacity for thought.

Of course, it is sometimes claimed that some apes have been taught to use language as well as very young children can use it. But as linguist Noam Chomsky has noted, “that's about like saying that Olympic high jumpers fly better than young birds who've just come out of the egg -- or than most chickens. These are not serious comparisons.” From a Thomistic point of view, what matters in determining whether a creature possesses language is not whether we can get it to mimic certain superficial aspects of language under artificial circumstances, but rather how it naturally tends to act when left to its own devices. And in their natural state, no animals other than human beings ever get beyond what Popper calls the expressive and signaling functions of language. But even if there were real evidence of ape language, that would not prove that thought doesn’t require language. Rather, it would show only that there are more kinds of thinking (and thus language-using) creatures than we thought.

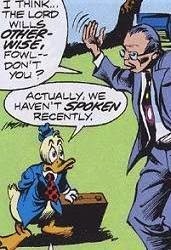

In any event, dogs, cats, and the other domesticated animals Hart and others would evidently like to think go to heaven certainly don’t have language. And it would be ridiculous to suggest that they have it but (like the dog in the comic book panel above) have been determined to hide the fact from us. Agere sequitur esse (“action follows being” or “activity follows existence”) is a basic principle of Scholastic metaphysics. The way a thing acts or behaves reflects what it is. If dogs, cats, and the like had language in the third and fourth of Popper’s senses, then at some time, somewhere, evidence of this would show up in the way they behave. Since it never has, we must conclude that they lack language in the relevant sense.

But if Davidson is right (and I think he is) then it follows that these animals lack rationality. And if they lack rationality, they lack anything that might survive the deaths of their bodies. In which case there is no afterlife for dogs, cats, and the other non-human animals to which we sometimes become sentimentally attached.

Published on April 27, 2015 19:09

April 21, 2015

Review of Mele

Over at the online edition of City Journal, I review Alfred Mele’s recent book

Free: Why Science Hasn't Disproved Free Will

.

Over at the online edition of City Journal, I review Alfred Mele’s recent book

Free: Why Science Hasn't Disproved Free Will

.

Published on April 21, 2015 15:33

April 16, 2015

Toner and McInerny on Scholastic Metaphysics

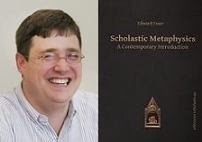

Two new reviews of Scholastic Metaphysics: A Contemporary Introduction. First, in the Spring 2015 issue of the American Catholic Philosophical Quarterly, Prof. Patrick Toner (pictured at left) kindly reviews the book. From the review:

Two new reviews of Scholastic Metaphysics: A Contemporary Introduction. First, in the Spring 2015 issue of the American Catholic Philosophical Quarterly, Prof. Patrick Toner (pictured at left) kindly reviews the book. From the review: This is an excellent little survey of scholastic metaphysics, written more or less from the perspective of “analytic Thomism”…

The refutation of scientism is elegant and thoroughly successful…

Feser explains the rationale behind [the] principle [of causality], distinguishes it from the Principle of Sufficient Reason, and defends it against many objections, including a standard from Hume, as well as more recent worries, from Newton, and from quantum mechanics. Very useful material.Feser next tackles the doctrine of substance, beginning with form and matter, and explaining the difference between substantial and accidental form, among other things. This chapter’s main contribution, in my estimation, is the fine way in which it shows that these notions are not anti-scientific throwbacks only acceptable to the hopelessly medieval…

As an analytic metaphysician, I found the book to be very good. Feser usually does an outstanding job of giving just the right sort of coverage to each topic he treats…

This would be an excellent book to use as a text in an undergraduate or graduate course in metaphysics or natural philosophy…

To sum up: highly recommended. Anyone working in metaphysics, the philosophy of nature, or the philosophy of mind would be well advised to read through this book…

Prof. Toner also has some criticisms. First, he suggests that my treatment of scientism might have been improved by responding to the approach represented by Thomas Hofweber in his essay in the Chalmers, Manley, and Wasserman volume Metametaphysics . That is a good suggestion, and I will plan to write up something on Hofweber. Toner also thinks the treatment of analogy is too brief. In my defense I’d say that here as with other topics it would have been difficult to say more without getting deep into issues lying outside the boundaries of metaphysics proper. For example, to say much more about the metaphysics of biological phenomena would have required an excursus in philosophy of biology and philosophy of nature; and to say much more about analogy would have required an excursus in philosophy of language and logic. But as Toner acknowledges, this is a “judgment call.”

In The Review of Metaphysics, Prof. D. Q. McInerny also very kindly reviews Scholastic Metaphysics. From the review:

One would be hard pressed to find a better introduction to scholastic metaphysics than that provided by Edward Feser. The book is excellently organized, treats its various topics with remarkable thoroughness and depth, and is written in an always clear, precise, and vibrant style. The book could only have been written by someone who has a complete command of the fundamental concepts of scholastic metaphysics, as well as an impressive knowledge of the main currents of modern philosophy. The book is argumentative in the best sense: conclusions are always supported by sturdy premises. Very effective use is made of concrete examples. The book comes accompanied with an ample and informative bibliography. For anyone who seeks a substantive and sound introduction to scholastic metaphysics, this is the book with which to begin.

Published on April 16, 2015 18:05

April 13, 2015

Back from Princeton

This past Saturday, I gave the Princeton Anscombe Society’s 10th Anniversary Lecture, on the subject “Natural Law and the Foundations of Sexual Ethics.” Prof. Robert George was the moderator. The Daily Princetonian covered the event, and the Anscombe Society has posted some pictures. Video of the lecture has also been posted at YouTube.I suppose I ought to warn the scrupulous that parts of the talk are explicit, albeit tastefully so. This is unavoidable when addressing this topic in any depth, though I suppose some would prefer I gave those portions of the talk in Latin!

This past Saturday, I gave the Princeton Anscombe Society’s 10th Anniversary Lecture, on the subject “Natural Law and the Foundations of Sexual Ethics.” Prof. Robert George was the moderator. The Daily Princetonian covered the event, and the Anscombe Society has posted some pictures. Video of the lecture has also been posted at YouTube.I suppose I ought to warn the scrupulous that parts of the talk are explicit, albeit tastefully so. This is unavoidable when addressing this topic in any depth, though I suppose some would prefer I gave those portions of the talk in Latin!

Published on April 13, 2015 21:55

April 7, 2015

Hart jumps the shark

In the April issue of First Things, David Bentley Hart takes Thomists to task for denying that some non-human animals posses “irreducibly personal” characteristics, that they exhibit “certain rational skills,” and that Heaven will be “positively teeming with fauna.” I respond at Public Discourse, in “David Bentley Hart Jumps the Shark: Why Animals Don’t Go to Heaven.”

In the April issue of First Things, David Bentley Hart takes Thomists to task for denying that some non-human animals posses “irreducibly personal” characteristics, that they exhibit “certain rational skills,” and that Heaven will be “positively teeming with fauna.” I respond at Public Discourse, in “David Bentley Hart Jumps the Shark: Why Animals Don’t Go to Heaven.”

Published on April 07, 2015 18:58

Edward Feser's Blog

- Edward Feser's profile

- 332 followers

Edward Feser isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.