Edward Feser's Blog, page 79

October 19, 2015

Koukl responds (Updated)

Christian apologist Greg Kouklkindly sent me a response to my recent post about the discussion generated by his recent comments about atheism, natural theology, and Romans 1:18-20. With his permission, I post it here. I’ve been thinking of writing up a follow-up to my recent post anyway, and when I do I’ll comment on Greg’s remarks. But for the moment, here is Greg’s response, for which I thank him:

Christian apologist Greg Kouklkindly sent me a response to my recent post about the discussion generated by his recent comments about atheism, natural theology, and Romans 1:18-20. With his permission, I post it here. I’ve been thinking of writing up a follow-up to my recent post anyway, and when I do I’ll comment on Greg’s remarks. But for the moment, here is Greg’s response, for which I thank him: Feser’s concern, I think, is partly the result of taking general remarks made in a video blog about Romans 1 and asking of it the kind of precision not generally possible in that format. In a brief verbal summary of an issue there is little opportunity for nuance regarding the kinds of concerns brought up in Feser’s thoughtful 2,500 word blog, which may account for my own remarks appearing “glib."Maybe a few brief comments (versus a full-throated response) will add more clarity, though it probably will not alleviate all the disagreement. No worries. I can live with opposing views, even from people I respect (I thoroughly enjoyed what I’ve read of Feser’s The Last Superstition).

Feser faulted me for lack of argument, yet my purpose was not to make a case, but rather merely to articulate what I take to be Paul’s assessment of man’s condition.

As to the comment, “'The Bible says so' is, of course, not a good argument to give someone who doesn’t accept the authority of the Bible in the first place,” I agree wholeheartedly, as those familiar with my work know. My comments in the video blog, however, were directed to believers (just as Paul’s were), not atheists, so a straightforward appeal to the text seems legitimate.

As to whether or not my take on Romans 1 is an “extreme interpretation” or not, I can only commend you to Paul’s wording itself. I don’t think it is the least bit vague, ambiguous, or moderate. He says that certain of God’s attributes have been “clearly seen” and “understood” (1:20), and certain particulars about God are “known” being “evident within them,” since “God made it evident to them” (1:19). Yet men still "suppress” (katecho, "to hold down, repress," Wuest) these truths “in unrighteousness.” It’s difficult to see how a more moderate (vs. my “extreme”) understanding of the passage could actually be faithful to Paul’s words.

Further, if our knowledge of God is merely “general and confused” (Aquinas), it’s hard to see how God can hold us accountable for it (“without excuse” 1:20), making us properly subject to his “wrath” (orge, 1:18).

Even after reading Feser’s critique (et al), it still strikes me that, regarding man’s innate knowledge of God, Paul is saying something quite a bit stronger than that man has “a natural inclination of the weaker and inchoate sort." Thus, his unbelief is properly culpable.

For the record, I take this knowledge to be dispositional (known even if not currently or consciously aware of), not occurent (in mind and currently aware of) for the reasons that Feser (and others) pointed out. So man’s state of awareness of God, and his heart’s disposition towards rebellion against God are both sub-conscious.

Thus, though many atheists are not consciously aware of their rebellion (some are, of course) and may feel they have intellectual integrity in their atheism (some demonstrate a measure of integrity in their reasoned rejection of God), still, when all the cards are on the table in the final judgment, when men’s deepest and truest motives are fully revealed (Lk. 12:2), rebellion will be at the core. This rebellion-at-the-core, I think, is what Paul had in mind in Rom. 1—a fairly ordinary, run of the mill biblical point, it seems.

Regarding beleaguered Emil, I am inclined to agree with Feser: "A religious believer is not like someone trying to hold a beach ball underwater; rather, he is like someone trying to get a submerged beach ball with a leak in it to come back up to the surface." Nicely put.

Remember, Paul’s point is that fallen humans are in rebellion and unbelief. But regeneration changes that, does it not? Those who have come to Christ (e.g., “Emil”) are not the subject of his concern. Doubt may still crop up, but for completely different reasons, I think. So the alleged reductio simply does not apply here However, even deeply distressed Emil (and atheists with his same complaint) must account for the objective morality that was violated by the massacre, and no subjectivist account (biological or social) is going to be adequate. Ultimately, even man’s ubiquitous complaint about real Evil in the world (a complaint I share), ultimately and irrevocably (I think) points back to the God who alone grounds the Goodness necessary to make the problem of evil intelligible to begin with.

So, it seems to me that my general remarks about Romans 1 and atheists are defensible given the video’s intended audience and scope, and given the specific language of Romans 1. In the future when I address this issue, I will try to remember the “dispositional knowledge” qualification that might alleviate some confusion.

One final thought. Though I do not think it helpful to bandy this phrase about in the public dialog, the statement, “The fool has said in his heart there is no God,” is not mine, but God’s.

Greg Koukl

Stand to Reason

UPDATE: Greg Koukl’s response has now been posted also at the Stand to Reason blog. And Randal Rauser comments on Koukl’s response at his own blog.

Published on October 19, 2015 17:58

Koukl responds

Christian apologist Greg Kouklkindly sent me a response to my recent post about the discussion generated by his recent comments about atheism, natural theology, and Romans 1:18-20. With his permission, I post it here. I’ve been thinking of writing up a follow-up to my recent post anyway, and when I do I’ll comment on Greg’s remarks. But for the moment, here is Greg’s response, for which I thank him:

Christian apologist Greg Kouklkindly sent me a response to my recent post about the discussion generated by his recent comments about atheism, natural theology, and Romans 1:18-20. With his permission, I post it here. I’ve been thinking of writing up a follow-up to my recent post anyway, and when I do I’ll comment on Greg’s remarks. But for the moment, here is Greg’s response, for which I thank him: Feser’s concern, I think, is partly the result of taking general remarks made in a video blog about Romans 1 and asking of it the kind of precision not generally possible in that format. In a brief verbal summary of an issue there is little opportunity for nuance regarding the kinds of concerns brought up in Feser’s thoughtful 2,500 word blog, which may account for my own remarks appearing “glib."Maybe a few brief comments (versus a full-throated response) will add more clarity, though it probably will not alleviate all the disagreement. No worries. I can live with opposing views, even from people I respect (I thoroughly enjoyed what I’ve read of Feser’s The Last Superstition).

Feser faulted me for lack of argument, yet my purpose was not to make a case, but rather merely to articulate what I take to be Paul’s assessment of man’s condition.

As to the comment, “'The Bible says so' is, of course, not a good argument to give someone who doesn’t accept the authority of the Bible in the first place,” I agree wholeheartedly, as those familiar with my work know. My comments in the video blog, however, were directed to believers (just as Paul’s were), not atheists, so a straightforward appeal to the text seems legitimate.

As to whether or not my take on Romans 1 is an “extreme interpretation” or not, I can only commend you to Paul’s wording itself. I don’t think it is the least bit vague, ambiguous, or moderate. He says that certain of God’s attributes have been “clearly seen” and “understood” (1:20), and certain particulars about God are “known” being “evident within them,” since “God made it evident to them” (1:19). Yet men still "suppress” (katecho, "to hold down, repress," Wuest) these truths “in unrighteousness.” It’s difficult to see how a more moderate (vs. my “extreme”) understanding of the passage could actually be faithful to Paul’s words.

Further, if our knowledge of God is merely “general and confused” (Aquinas), it’s hard to see how God can hold us accountable for it (“without excuse” 1:20), making us properly subject to his “wrath” (orge, 1:18).

Even after reading Feser’s critique (et al), it still strikes me that, regarding man’s innate knowledge of God, Paul is saying something quite a bit stronger than that man has “a natural inclination of the weaker and inchoate sort." Thus, his unbelief is properly culpable.

For the record, I take this knowledge to be dispositional (known even if not currently or consciously aware of), not occurent (in mind and currently aware of) for the reasons that Feser (and others) pointed out. So man’s state of awareness of God, and his heart’s disposition towards rebellion against God are both sub-conscious.

Thus, though many atheists are not consciously aware of their rebellion (some are, of course) and may feel they have intellectual integrity in their atheism (some demonstrate a measure of integrity in their reasoned rejection of God), still, when all the cards are on the table in the final judgment, when men’s deepest and truest motives are fully revealed (Lk. 12:2), rebellion will be at the core. This rebellion-at-the-core, I think, is what Paul had in mind in Rom. 1—a fairly ordinary, run of the mill biblical point, it seems.

Regarding beleaguered Emil, I am inclined to agree with Feser: "A religious believer is not like someone trying to hold a beach ball underwater; rather, he is like someone trying to get a submerged beach ball with a leak in it to come back up to the surface." Nicely put.

Remember, Paul’s point is that fallen humans are in rebellion and unbelief. But regeneration changes that, does it not? Those who have come to Christ (e.g., “Emil”) are not the subject of his concern. Doubt may still crop up, but for completely different reasons, I think. So the alleged reductio simply does not apply here However, even deeply distressed Emil (and atheists with his same complaint) must account for the objective morality that was violated by the massacre, and no subjectivist account (biological or social) is going to be adequate. Ultimately, even man’s ubiquitous complaint about real Evil in the world (a complaint I share), ultimately and irrevocably (I think) points back to the God who alone grounds the Goodness necessary to make the problem of evil intelligible to begin with.

So, it seems to me that my general remarks about Romans 1 and atheists are defensible given the video’s intended audience and scope, and given the specific language of Romans 1. In the future when I address this issue, I will try to remember the “dispositional knowledge” qualification that might alleviate some confusion.

One final thought. Though I do not think it helpful to bandy this phrase about in the public dialog, the statement, “The fool has said in his heart there is no God,” is not mine, but God’s.

Greg Koukl

Stand to Reason

Published on October 19, 2015 17:58

October 16, 2015

Repressed knowledge of God?

Christian apologist Greg Koukl, appealing to Romans 1:18-20, says that the atheist is “denying the obvious, aggressively pushing down the evidence, to turn his head the other way, in order to deny the existence of God.” For the “evidence of God is so obvious” from the existence and nature of the world that “you’ve got to work at keeping it down,” in a way comparable to “trying to hold a beach ball underwater.” Koukl’s fellow Christian apologist Randal Rauser begs to differ. He suggests that if a child whose family had just been massacred doubted God, then to be consistent, Koukl would -- absurdly -- have to regard this as a rebellious denial of the obvious. Meanwhile, atheist Jeffery Jay Lowder agrees with Rauser and holds that Koukl’s position amounts to a mere “prejudice” against atheists. What should we think of all this?I would say that Koukl, Rauser, and Lowder are each partly right and partly wrong. It will be easiest to explain why by contrasting their views with what I think is the correct one, so let me first summarize that.

Christian apologist Greg Koukl, appealing to Romans 1:18-20, says that the atheist is “denying the obvious, aggressively pushing down the evidence, to turn his head the other way, in order to deny the existence of God.” For the “evidence of God is so obvious” from the existence and nature of the world that “you’ve got to work at keeping it down,” in a way comparable to “trying to hold a beach ball underwater.” Koukl’s fellow Christian apologist Randal Rauser begs to differ. He suggests that if a child whose family had just been massacred doubted God, then to be consistent, Koukl would -- absurdly -- have to regard this as a rebellious denial of the obvious. Meanwhile, atheist Jeffery Jay Lowder agrees with Rauser and holds that Koukl’s position amounts to a mere “prejudice” against atheists. What should we think of all this?I would say that Koukl, Rauser, and Lowder are each partly right and partly wrong. It will be easiest to explain why by contrasting their views with what I think is the correct one, so let me first summarize that. Do we have a natural tendency to believe in God? Yes, but in something like the way in which someone might have a natural aptitude for music or for art. You might be inclined to play some instrument or to draw pictures, but you’re not going to do either very well without education and sustained practice. And without cultivating your interest in music or art, your output might remain at a very crude level, and your ability might even atrophy altogether.

Or consider moral virtue. It is natural to us, but only in the sense that we have a natural capacityfor it. Actually to acquire the virtues still requires considerable effort. As Aquinas writes: “[V]irtue is natural to man inchoatively… both intellectual and moral virtues are in us by way of a natural aptitude, inchoatively, but not perfectly… (Summa Theologiae I-II.63.1, emphasis added), and “man has a natural aptitude for virtue; but the perfection of virtue must be acquired by man by means of some kind of training” (Summa Theologiae I-II.95.1).

Now, knowledge of God is like this. We are indeed naturally inclined to infer from the natural order of things to the existence of some cause beyond it. But the tendency is not a psychologically overwhelmingone like our inclination to eat or to breathe is. It can be dulled. Furthermore, the inclination is not by itself sufficient to generate a very clear conception of God. As Aquinas writes:

To know that God exists in a general and confused way is implanted in us by nature, inasmuch as God is man's beatitude… This, however, is not to know absolutely that God exists; just as to know that someone is approaching is not the same as to know that Peter is approaching, even though it is Peter who is approaching… (Summa Theologiae I.2.1, emphasis added)

In other words, without cultivation by way of careful philosophical analysis and argumentation, the knowledge of God we have naturally will remain at a very crude level -- “general and confused,” as Aquinas says, like knowing that someone is approaching but not knowing who -- just as even natural drawing ability or musical ability will result in crude work if not cultivated.

Moreover, few people have the leisure or ability to carry out the philosophical reasoning required, and even the best minds are liable to get some of the details wrong. This, in Aquinas’s view, is why for most people divine revelation is practicallynecessary if they are to acquire knowledge even of those theological truths which are in principle accessible via purely philosophical argumentation:

Even as regards those truths about God which human reason could have discovered, it was necessary that man should be taught by a divine revelation; because the truth about God such as reason could discover, would only be known by a few, and that after a long time, and with the admixture of many errors. (Summa Theologiae I.1.1)

Now, these theses -- that an inclination to believe in God is natural to us, but that without cultivation it results only in a general and confused conception of God -- are empirically well supported. Belief in a deity or deities of some sort is more or less a cultural universal, and is absent only where some effort is made to resist it (about which effort I’ll say something in a moment). But the content of this belief varies fairly widely, and takes on a sophisticated and systematic form only when refined by philosophers and theologians.

Even an atheist could agree with this much. Indeed, I believe Jeff Lowder would more or less agree with it. In the post linked to above, he opines that his fellow atheists need to answer the arguments of religious apologists rather than ignoring them because:

The scientific evidence suggests that humans have a widespread tendency to form beliefs about invisible agents, including gods… I can think of no reason to think such tendencies will go away with a contemptuous sneer.

Now, Jeff’s basis for this claim lies at least in part in evolutionary psychology rather than Aristotelian-Thomistic philosophical anthropology. (It wouldn’t be the first time that the two approaches led to similar conclusions.) But the bottom line is for present purposes the same: The belief toward which we are inclined is inchoate (“invisible agents, including gods”), but the inclination is a natural one. Indeed, the inclination goes deep enough in our nature that it takes some argumentation to overcome it (rather than the mere “contemptuous sneer” of the New Atheist).

An implicit acknowledgment of an inclination toward some kind of theism is arguably also to be found in some comments from atheist physicist Sean Carroll, recently quoted by Jerry Coyne in a post to which Jeff refers (and to which I recently replied). In the passage quoted by Coyne, Carroll says:

[T]he ultimate answer to “We need to understand why the universe exists/continues to exist/exhibits regularities/came to be” is essentially ‘No we don’t.’…

Granted, it is always nice to be able to provide reasons why something is the case. Most scientists, however, suspect that the search for ultimate explanations eventually terminates in some final theory of the world, along with the phrase “and that’s just how it is.” It is certainly conceivable that the ultimate explanation is to be found in God; but a compelling argument to that effect would consist of a demonstration that God provides a better explanation (for whatever reason) than a purely materialist picture, not an a priori insistence that a purely materialist picture is unsatisfying.

End quote. Carroll is essentially acknowledging here that we have an inclination to think that “That’s just how it is” is not an appropriate terminus of explanation, and that we find it “unsatisfying” to leave things there rather than moving on to something which is not a mere unintelligible brute fact but exists of absolute necessity -- the God of Scholastic and rationalist theology. He just thinks we have good reason to resist this inclination. (As I’ve noted elsewhere, Carroll in fact does not have a good reason to think we should resist it, but that’s neither here nor there for present purposes. Even if he had an excellent reason, the point is that Carroll seems implicitly to acknowledge that some kind of inclination is there. To be sure, whether he’d say the inclination is natural, I don’t know.)

So, Koukl is, I think, correct to this extent: We do indeed have a natural tendency to infer from the natural world to a divine cause, and this tendency is strong enough that it takes some effort (in the form of philosophical reasoning) to get ourselves to conclude that we ought to resist it. And again, I think even an atheist could agree with that much (as Jeff and perhaps Carroll apparently do).

However, Koukl also seems to think that the existence of God is simply blindingly obvious, so that our inclination to believe in God is nearly overwhelming-- again, as difficult to keep down as a beach ball under water. And that, I think, is simply not the case. He also implies that nothing short of culpable irrationality and blatant self-deception could possibly lead one to resist this inclination. And that, I think, is simply not the case either. There is no good philosophical or theological reason to make either of these extreme claims. And the claims are, I think, pretty clearly empirically false. For one thing, there are lots of atheists who, though deeply mistaken, are nevertheless intellectually honest and do not have a difficult time resisting belief in God. (I used to be such an atheist, and I knew, and know, other such atheists.) For another thing, there are religious believers who have crises of belief -- who find themselves doubting even though they don’t want to doubt.

Obviously, such a religious believer is not like someone trying to hold a beach ball underwater; rather, he is like someone trying to get a submerged beach ball with a leak in it to come back up to the surface. And the intellectually honest atheist is like someone whose beach ball has completely popped and sunk to the bottom. What each person needs is, not to be told to stop holding the beach ball down, but rather help in repairing it.

Certainly Koukl does not give a good argument for his extreme interpretation of the thesis that a tendency toward theism is natural to us. The closest he comes is to appeal to Romans 1:18-20. But “The Bible says so” is, of course, not a good argument to give someone who doesn’t accept the authority of the Bible in the first place (as the atheist does not). Nor is it a good argument to give someone who thinks you are misinterpreting the passage in question. And the passage does not, I think, make the extreme claims Koukl seems to be attributing to it. For one thing, it need be interpreted as claiming merely that we have a natural inclination of the weaker and inchoate sort, rather than of the overwhelming sort (which is how Aquinas seems to understand St. Paul -- soon after the passage from Summa Theologiae I.2.1 quoted above, in Article 2 of the same Question, he quotes Romans 1:20).

For another thing, St. Paul need be understood as claiming merely that atheism and/or idolatry on the large scale, as mass phenomenaare maintained by a kind of sinful suppression of the natural inclination in question. And I think that’s true. As I argued in a recent post, the New Atheism -- not atheism in general, but the shallow, boorish, ill-informed atheism of Dawkins, Krauss, Coyne, et al., which has turned into something of a mass movement -- is maintained by intellectual dishonesty, and is fundamentally motivated, not by a genuine concern for truth and rationality, but rather by the pleasure New Atheists take in feeling superior to those they caricature as irrational and ignorant. It is intellectual pride that drives the New Atheism, and that is, of course, a grave vice. It is also obvious that many secularists (not all, but many) are motivated by hostility to the sexual morality upheld by traditional religious belief, and that such hostility is (as I argued in another recent post) often extreme and irrational. Certainly, from a Thomistic natural law point of view, sexual vice is another major component of the hostility to religion found in large sectors of the contemporary Western world.

However, it simply does not follow that every singleatheist is fundamentally motivated by pride, lust, or some other vice -- as opposed to simply making an honest intellectual error or set of errors -- and Romans 1:18-20 need not be read as asserting this. It is perfectly possible for someone mistakenly but sincerely to believe that there are good arguments for atheism, and thus good arguments for resisting our natural tendency to believe in some sort of deity. He might think that such a tendency is like our tendency to commit various common logical fallacies -- a kind of congenital cognitive defect. This is in my view completely wrongheaded, but that it is wrongheaded needs to be shown, not merely asserted or proof-texted.

So, while we do have a natural inclination toward an inchoatetheism, and while atheism as a massphenomenon is, I would agree, sustained by grave vices -- so that to that extent I concur with Koukl -- nevertheless, to dismiss all atheism as such as merely an intellectually dishonest refusal to admit the blindingly obvious would be a serious mistake. And to that extent I think Jeff is right to hold that the suppression thesis can amount to an unfair “prejudice” against atheists. (In my atheist days, I used to roll my eyes at the suggestion that all atheists are simply sinfully repressing what they know deep down to be true, and I can certainly understand why other atheists would roll their eyes too.)

What about Rauser’s remarks? Well, to the extent that he thinks Koukl’s position is too glib, I agree with him, for the reasons just given. However, in fairness to Koukl, I don’t think Rauser’s specific example is really a good counterexample. Rauser writes:

Koukl seems oblivious to the fact that his argument turns every failure to believe in God’s existence and nature with maximal conviction into an immoral instance of rebellion.

Think, for example, of fifteen year old Emil whose family was just massacred in a home invasion gone awry. As tears roll down his cheeks, Emil looks to heaven and cries out “God, are you really there? Do you really care?”

End quote. The trouble with this example is that it is not clear that someone like Rauser’s imagined Emil really doubts God’s existence so much as his goodness. Rauser imagines Emil asking God: “Do you really care?” -- and you can only ask such a thing of someone you believe exists. (No one who comes to doubt the existence of Santa Claus lets out an anguished cry like: “Santa, do you really care?”) Moreover, Rauser speaks of a lack of “maximalconviction,” which is not the same thing as atheism. So, Koukl could respond to Rauser: “I’m talking about someone who outright deniesthat there is a God. But you’re talking about someone who merely to some extent doubtsthe existence of God, or even just doubts God’s goodness rather than his existence. That’s very different.”

Published on October 16, 2015 13:00

October 9, 2015

Walter Mitty atheism

While writing up my recent post on Jerry Coyne’s defense of his fellow New Atheist Lawrence Krauss, I thought: “Why can’t these guys be more like Keith Parsons and Jeff Lowder?” (Many readers will recall the very pleasant and fruitful exchange which, at Jeff’s kind invitation, Keith and I had not too long ago at The Secular Outpost.) As it happens, Jeff has now commented on my exchange with Coyne. Urging his fellow atheists not to follow Coyne’s example, Jeff writes:

While writing up my recent post on Jerry Coyne’s defense of his fellow New Atheist Lawrence Krauss, I thought: “Why can’t these guys be more like Keith Parsons and Jeff Lowder?” (Many readers will recall the very pleasant and fruitful exchange which, at Jeff’s kind invitation, Keith and I had not too long ago at The Secular Outpost.) As it happens, Jeff has now commented on my exchange with Coyne. Urging his fellow atheists not to follow Coyne’s example, Jeff writes: If I were to sum up Feser’s reply in one word, it would be, “Ouch!” I think Feser’s reply is simply devastating to Coyne and I found myself in agreement with most of his points.

As Jeff also writes:

It shouldn’t come as a surprise, however, that often the same atheists who are so dismissive of theism tend to use such awful arguments and objections against it. In a sense, this is understandable. If you’ve concluded that belief X is not only false but stupid or even irrational, then you’re unlikely to spend much if any time trying to understand the best arguments for X.

Now, the irony of this situation is that in every attempt to justify their dismissive attitude toward theism, New Atheists like Coyne, Krauss, Dawkins and myriad others only ever succeed in demonstrating conclusively that that dismissive attitude is unjustified. For you cannot rationally reject a position, dismissively or not, unless you first understand what it is. And every time they open their mouths, these New Atheists show that they very badly misunderstand the central claims of, and arguments for, theism. Indeed, it is amazing how the very same crude misunderstandings recur again and again and again, even after they have been patiently, clearly, and repeatedly explained.

Consider, for example, that Coyne and I first had an exchange on the subject of cosmological arguments for God’s existence over four years ago. Coyne claimed at the time that he really wanted to know what the best arguments for theism are, and insisted that he was “dead serious here, and not looking for sarcastic answers.” I recommended that he study the arguments of Aquinas, with the help of some serious commentators who could explain the metaphysical background to the arguments. (Unsurprisingly, I recommended my own book Aquinas , though I also cited some other authors.) Coyne said he would do so. Very soon thereafter I posted an article explaining in detail the various common misunderstandings of cosmological arguments, including the versions of the argument presented by Aquinas. I explained, for example, why the argument does not rest on the premise that “everything has a cause”; why, accordingly, the argument does not make of God some arbitrary exception to a general rule; why the argument nevertheless does not make of God a brute fact who just exists without any explanation (since not all explanations are causes); why versions of the argument like the ones defended by Aquinas and Leibniz (and by me, for that matter) are not concerned to show that the universe had a beginning; and so forth. Coyne commented on that article. In the course of doing so, he accused me of “intellectual dishonesty” -- on utterly preposterous grounds, as I showed here. But if Coyne himself is as intellectually honest as he would like us to think, he presumably read the article before commenting on it. In which case he would know that the kind of cosmological arguments I defend do not argue for a temporal beginning of the universe, do not rest on the premise that “everything has a cause,” do not make of God a brute fact who just exists without explanation, etc.

Flash forward four years to our current exchange. As I noted in my recent response to Coyne, despite all the back and forth of four years ago, despite his purportedly “dead serious” intention to find out what the best arguments really say, despite his commitment to study Aquinas in particular -- despite all that, he still falsely attributes to me a version of the cosmological argument that “insist[s] that that world had to have a beginning,” and still falsely attributes to me the thesis that God is “just there” without explanation!

But it is worse even than that. Even after my recent response to Coyne appeared, he posted a further comment in his combox stillasserting -- wait for it -- that my “main argument… is that everything has a ‘cause’” and that I “rely on everything having a cause -- except God” (!) And he said this in reply to an atheist reader who complained about atheists like Coyne misrepresenting what theists really say!

Could it get worse even than that? Well, on Jerry Coyne’s blog it sure can, and it does. In yet another post two days later, Coyne claimed that the cosmological argument’s answer to the question “Why does God exist?” is: “He just does,” without explanation (!) This despite the fact that -- as I explained in my response to him just days before (and as I explained in my exchange with him four years ago) -- that is precisely the opposite of what Aristotelian, Thomist, Leibnizian, and other defenders of the argument actually say! And when a reader pointed out in Coyne’s combox that this is a caricature of the argument, Coyne banned him from posting any further (purportedly on the grounds that the reader was being rude)!

Needless to say, there is something truly pathological going on here. And that, by the way, is one reason Coyne, Krauss, and company are worth at least a little of our attention. Some readers have asked me why I bother replying to people who are so extremely irrational and dishonest, and therefore unlikely to respond well to serious criticism. Part of the reason is that though Coyne, Krauss, Dawkins, and many of their fans are indeed impervious to rational argumentation, there are onlookers who are not impervious to it. And those people are reachable and worth trying to reach. After all, Coyne, Krauss, Dawkins, and some of the other better known New Atheists are, though irrational and dishonest, not stupid. In their own fields, some of them even do interesting work. For that reason, some people who know as little about philosophy and theology as they do but who are rational and honest might falsely suppose that these New Atheists must have something important to say about those particular subjects. Hence it is useful now and again to expose Coyne et al. for the frauds that they are, so that well-meaning third parties will see that they are not to be taken seriously on philosophical and theological questions. The more they make fools of themselves, the more they shouldbe discussed rather than ignored, at least so long as there is any intellectually honest person who still somehow thinks the New Atheism is anything but a bad joke.

Another reason for paying them some attention, though, is that Coyne, Krauss, Dawkins, and company are simply genuine curiosities. Again, they are not stupid, and indeed have serious intellectual accomplishments to their credit. And yet on the subjects of religion and philosophy they are incapable of seeing that their self-confidence is laughably, cringe-makingly out of proportion to their actual competence. They exhibit exactly the sort of stubborn, bigoted closed-mindedness and ignorance that they smugly condemn when they perceive it in others. What exactly is going on here? What makes these weird people tick? That is a question of real intellectual interest.

The answer, I would suggest, is sentimentality. I use the word in a semi-technical sense, following the analysis offered in The Aesthetics of Music by Roger Scruton (who was in turn building on some ideas of Michael Tanner). A sentimental person, according to Scruton, tends to be quick to respond emotionally to a stimulus, will appear to be pained but will enjoy his pangs, will respond with equal violence to a variety of stimuli in succession, will nevertheless avoid following his emotional responses up with appropriate actions, and will respond more readily to strangers and to abstract issues than to persons known to him or to concrete circumstances requiring time, energy, or personal sacrifice. In short, a sentimental person is one whose emotional life becomes an end in itself and loses its connection both to the external circumstances that would normally shape it and to the behavior that it ought to generate. Feelings of moral outrage, romantic passion, and other emotional states become valued for their own sake to such an extent that the actual moral facts, the well-being of the beloved, etc. fade into the background.

For instance, someone who constantly chats up the plight of the homeless, but without any real interest in finding out why people become homeless or what ways of helping them are really effective, might plausibly be described as merely sentimental. “How awful things are for the homeless!” is not really the thought that moves him. What really moves him is the thought: “How wonderful I am to think of how awful things are for the homeless!” His feelings of compassion function, not to get him to do what is necessary to help those who are homeless, but rather to provide him with assurance of his superior virtue. His high dudgeon functions, not to prod him to find out whether the homeless are really being victimized by evildoers, but rather to reinforce his assurance of his superior virtue by allowing him to contrast himself with the imagined evildoers. This kind of onanistic moralism requires a fantasy world rich enough to sustain it. Poignant or dramatic images of suffering and of injustices inflicted are far more likely to foster such fantasies than are cold statistics or the actual, mundane details of the lives of homeless people. Hence someone who is merely sentimental about homelessness might prefer movies, songs, and the like to social scientific study as a source of “information” about homelessness and its causes.

Now, the New Atheism, I submit, is exactly like this. The New Atheist talks, constantly and loudly, about reason, science, evidence, facts, being “reality-based,” etc. Equally constantly and loudly, he decries dogmatism, ignorance, wishful thinking, whatever is merely “faith-based,” etc. And he relentlessly denounces “religious” people, whom, he imagines, are central casting exemplars of the latter vices. But it is not reason, science, etc. that really move him. What really moves him is the pleasure that the thought of being paradigmatically rational, scientific, etc. gives him. Nor is he really moved by what religious people actually think. After all, he not only doesn’t trouble himself to find out what they actually think, but often will expend great energy trying to rationalize his refusalto find out what they actually think. (Consider e.g. P.Z. Myers’ shamelessly question-begging “Courtier’s reply” dodge.) Rather, what moves him is the self-righteous delight he takes in his belief in his intellectual and moral superiority over “religious” people. His “rationalism” consists, not in actually being rational, but in constantly chatting up rationality and constantly badmouthing those who, at least in his imagination, are not as rational as he enjoys believing that heis.

Here too, we have a kind of moralistic onanism which requires a rich fantasy life to support it. Finding out what thinkers like Aquinas, Leibniz, et al. actually saidwould completely destroy the fantasy, because they simply don’t fit the New Atheist’s caricature of religion. Hence the New Atheist nourishes his imagination instead with made-up examples of purportedly theistic ideas and argumentation, which he typically derives from reading other New Atheist writers rather than by reading what religious thinkers themselves have written. He repeatedly calls these examples to mind when he wants to reassure himself of the stupidity of religious people and of his superiority over them -- especiallywhen he encounters some religious opponent who doesn’t seem to fit his stereotype. He thinks: “First cause arguments start from the premise that ‘everything has a cause’; all such arguments founder on their inability to answer the challenge ‘What caused God?’; theism is incompatible with science, or at least presupposes outdated science; theism always ultimately rests on appeals to faith, or the Bible, or emotion…” and so forth. None of this is true, and it is all easily refuted simply by consulting the actual writings of religious thinkers. But the New Atheist is able to keep himself from seeing this by translating everything an opponent says into something he pulls from his mental bag of clichés about “what theists think.”

Hence, in response to my recent articles about Krauss and Coyne, we have Coyne saying the Bizarro-world things cited above. We have an irate Krauss fan asking: “Why do you believe in God? Because the Bible told you to, right?” We have one of Coyne’s readers saying: “I'll admit I haven't read your entire response to Jerry here” -- and then going on nevertheless to attribute to me outdated scientific ideas I not only have never endorsed, but have many times explicitly rejected. We have other Coyne readers simply refusing to get over their fixation on the stupid “Everything has a cause” argument that no philosopher or theologian has ever defended, even in the face of other, more sober atheist readers’ begging them to stop attacking this straw man. We have Krauss, in the New Yorker article to which I replied in Public Discourse, deluding himself into thinking that it is his impoliteness, rather than his incompetence, that prompts other atheists to criticize him. We have the breathtaking chutzpah of Coyne accusing, not just critics of the New Atheism, but even atheist critics of the New Atheism, of “distortion” of the New Atheists’ views.

It is as if these people are so lost in their delusions that they literally cannot see what is really there on the page or the computer screen in front of them. All they can see is the New Atheist Fantasyland they’ve constructed, where every ticket is a scarlet-A-for-atheist ticket, and Coyne and Co. keep going on the same rides over and over and over again. The New Atheists like to think that they win every argument, and indeed they do, though only in the way Walter Mitty wins every battle.

Published on October 09, 2015 17:02

October 4, 2015

Why can’t these guys stay on topic? Or read?

Jerry Coyne comments on my recent

Public Discourse article about Lawrence Krauss

. Well, sort of. Readers of that article will recall that it focused very specifically on Krauss’s argument to the effect that science is inherently atheistic, insofar as scientists need make no reference to God in explaining this or that phenomenon. I pointed out several things that are wrong with this argument. I did not argue for God’s existence. To be sure, I did point out that Krauss misunderstands how First Cause arguments for God’s existence are supposed to work, but the point of the article was not to develop or defend such an argument. I have done that many times elsewhere. Much less was my article concerned to defend any specifically Catholic theological doctrine, or opposition to abortion, or any conservative political position. Again, the point of the essay was merely to show what is wrong with a specific argument of Krauss’s. An intelligent response to what I wrote would focus on that.Coyne, however, is all over the place. He devotes his first paragraph to informing his readers about the Witherspoon Institute -- which hosts Public Discourse -- and the “right-wing” political views with which it is associated. How is this relevant to evaluating the cogency of the arguments presented in my article? It is, of course, in no way relevant. So why does Coyne bring it up? Could it be to prompt his (mostly left-wing) readers automatically to discount anything I have to say before even hearing it? Nah, couldn’t be. That would be a blatant logical fallacy of poisoning the well. And Coyne is, after all, a New Atheist, and “therefore” a devotee of Logic, Science, Evidence, and all things Rational.

Jerry Coyne comments on my recent

Public Discourse article about Lawrence Krauss

. Well, sort of. Readers of that article will recall that it focused very specifically on Krauss’s argument to the effect that science is inherently atheistic, insofar as scientists need make no reference to God in explaining this or that phenomenon. I pointed out several things that are wrong with this argument. I did not argue for God’s existence. To be sure, I did point out that Krauss misunderstands how First Cause arguments for God’s existence are supposed to work, but the point of the article was not to develop or defend such an argument. I have done that many times elsewhere. Much less was my article concerned to defend any specifically Catholic theological doctrine, or opposition to abortion, or any conservative political position. Again, the point of the essay was merely to show what is wrong with a specific argument of Krauss’s. An intelligent response to what I wrote would focus on that.Coyne, however, is all over the place. He devotes his first paragraph to informing his readers about the Witherspoon Institute -- which hosts Public Discourse -- and the “right-wing” political views with which it is associated. How is this relevant to evaluating the cogency of the arguments presented in my article? It is, of course, in no way relevant. So why does Coyne bring it up? Could it be to prompt his (mostly left-wing) readers automatically to discount anything I have to say before even hearing it? Nah, couldn’t be. That would be a blatant logical fallacy of poisoning the well. And Coyne is, after all, a New Atheist, and “therefore” a devotee of Logic, Science, Evidence, and all things Rational. Then there is the title of his blog post. Coyne summarizes my response to Krauss as follows: “Feser to Krauss: Shut up because of the Uncaused Cause.” That implies that the reason I gave for saying that Krauss should stop mouthing off about philosophy and theology is that the cosmological argument for an Uncaused Cause is a successful argument and thus refutes atheism. Hence (it is insinuated) if I have failed to show in my article that that argument really does succeed, then I have also failed to show that Krauss should stop mouthing off about these subjects.

But of course, that’s not what I said. The reason Krauss should stop mouthing off, I said, is that he has repeatedly shown -- not just in the view of theologians, but even in the view of some people otherwise sympathetic to his position -- that he has a very poor understanding of the philosophical and theological ideas he routinely criticizes. Indeed, I noted that Coyne himself has said that the arguments in Krauss’s New Atheist book are of poor quality. Now, Krauss’s arguments would be of poor quality whether or notany version of the argument for an Uncaused Cause succeeds. And it is that consistently poor quality of his arguments that justifies his critics in saying that he ought to stop mouthing off about philosophy and theology until such time as he actually learns something about those subjects. Again, whether any First Cause argument succeeds is not what I was trying to establish in my article, and is simply irrelevant to the issues I actually was addressing in the article.

Next, Coyne claims that Krauss gives a good reason why scientists should (as Krauss claimed in the New Yorker piece I was responding to) be “militant atheists.” The reason is that science is incompatible with “authoritarianism,” with “suppression of open questioning,” or with treating any ideas as “sacred” or “beyond question.” But the trouble with this “argument” is that it is an obvious non sequitur. The proposition that we should not treat any idea as beyond questioning does not entail the proposition that there is no God, nor even the proposition that it is doubtful that there is a God. Indeed, it entails nothing one way or the other about God’s existence at all. And thus it does not give any support to atheism, militant or otherwise. The most it shows is that we shouldn’t be dogmatic about any argument for theism, but instead should always be open to hearing criticism of such arguments -- and I certainly agree with that, even though I am not an atheist. It also shows, though, that we shouldn’t be dogmatic about any argument for atheism either, but should always be willing to hear out criticisms of thosearguments too.

Indeed, if anything it is Krauss’s “militancy”which should trouble Coyne if he is really serious about not treating any idea as sacred or beyond question. How can someone be “militant” about atheism without exhibiting exactly the sort of dogmatism Coyne claims he rejects? Indeed, since Coyne himself has admitted that Krauss has given bad arguments for atheism, shouldn’t he also admit that Krauss is the last person to be recommending “militancy”?

Coyne does finally say a little about the actual arguments I gave in my Public Discourse article, but unfortunately the quality of his reply doesn’t improve. Recall that, in my piece, I had said that the main traditional arguments for God’s existence don’t begin with facts of the sort that fall within the domain investigated by science. Rather, they begin with facts of a more fundamental kind -- facts about what any possible science must itself presuppose(such as facts about the nature of causality as such, facts about what it is to be a law of nature in the first place, the fact that there exists anything contingent at all -- including whatever the fundamental physical laws turn out to be -- and so forth). Coyne replies:

But if in fact one construes science broadly, as a combination of reason, empirical study, and verification, yes, existence of God should show up in “scientific” inquiry. Since it doesn’t, religionists use the word “reason” to encompass a brew of dogma, scripture, and personal revelation.

There are two problems with this. First, I have myself, of course, never defined “reason” in a way that “encompass[es] a brew of dogma, scripture, and personal revelation.” Neither does Aristotle, Plotinus, Maimonides, Avicenna, Aquinas, Scotus, Leibniz, Clarke, or any other philosopher who thinks that the existence of God can be rationally demonstrated. This is merely a straw man entirely of Coyne’s own invention, as anyone who actually knows something about the history of philosophical theology is aware.

Second, Coyne defines “science” so broadly that the arguments of writers of the kind I just cited would in fact count as “scientific” even by Coyne’s criteria, even though they would not be arguments of physics, chemistry, biology, or the like, but instead arguments of a sort that appeal to deeper features of reality than any of those specific sciences do.

Consider, to take just one example, the Aristotelian argument for an Unmoved Mover. It begins with the fact of change, which we know via experience -- and is thus “empirical” and “verifiable” -- and argues that we cannot coherently deny that at least some sorts of change really do occur, without at the same time denying the reality of experience itself (where experience is the precondition of the observation and experiment upon which empirical science rests). The argument proceeds from there to reason to conclusions about the preconditionsof there being change of any sort at all. For instance, it argues that change could not occur without there being a distinction in reality between a thing’s actualitiesand its potentialities. It argues that a potentiality can only be actualized by something already actual. It argues that something’s being actualized at any moment presupposes something actualizing it at that moment, and that the specific sort of regress of causes that this generates cannot in principle proceed to infinity. And so forth.

Note that I am not actually giving the argument here, because for one thing, like any argument about such a fundamental aspect of reality, it is not the sort of thing that could be summarized in a couple of paragraphs in a blog post. And for another thing, I’ve stated and defended the argument at length several times in other places, such as in my book Aquinas . The point for present purposes is just that since Coyne defines “science” as broadly as he does, this argument would count as “scientific” given his criteria. Hence even if he wanted to reject the argument, he could not do so on the grounds that it is “unscientific.” He’d have to find some othergrounds for doing so. And the same thing is true of the arguments of writers like Aquinas, Leibniz, and others of the sort I’ve mentioned.

That, however, would require Coyne seriously to studythese arguments and find out what they actually say -- rather than glibly dismissing them a priori on the grounds that they are allegedly “unscientific.” And that is something Coyne has consistently refused to do. To be sure, longtime readers will recall that, in the course of an earlier exchange I had with him, Coyne declared that he would make the effort to study the arguments of Aquinas. However, over four years later, he has still not followed this up with any announcement about what he learned. And that he never bothered actually to do what he said he would do is obvious from the fact that when he does comment on what Aquinas and Thomists like myself think, he succeeds in showing only that -- like Krauss -- he has absolutely no idea what he is talking about. For example, in this latest post of his he says:

To Feser, the existence of the natural world is itself evidence for God, for he keeps insisting that that world had to have a beginning, and if that beginning was the Big Bang, or even if the Big Bang had a natural origin and there are universes that spawn other universes, well, those, too must have a causal chain that, in the end terminates in God.

But as anyone who’s ever actually bothered to read what I’ve written on this subject knows, in fact I have not argued that the “world had to have a beginning” at the “Big Bang” or at any other point. And neither Aquinas, nor Leibniz, nor any of the other philosophers whose arguments I have endorsed make that claim either when arguing for a divine First Cause. Whether the universe had a temporal beginning is completely irrelevant to arguments like Aquinas’s Five Ways, Leibniz’s cosmological argument, Neo-Platonic arguments, or any of the other arguments I favor. Aquinas explicitly denies -- at the length of a short book -- that this is something a good argument for a First Cause should focus on. And it is a point that I’ve repeatedly emphasized myself. I’ve pointed this out, oh, maybe about 1,234 times. It’s about as well known a fact about my views as any. Saying that “Feser… keeps insisting that that world had to have a beginning” is like saying “Coyne keeps insisting that New Atheists ought to treat theology with greater respect.” It’s about as incompetent a summary of an opponent’s position as can be imagined.

The same refusal to do one’s homework is manifest in some of Coyne’s other remarks. For example, he writes:

[T]heists like Feser face their own Ultimate Questions: Why is there a God rather than no God? How did God come into being, and what was He doing before he created Something out of Nothing? To answer those, some people might point to scripture or revelation, but that’s unsatisfying, for different scriptures and different revelations say different things. In the end, Feser must resort to the same answer physicists give. When told by rationalists that we need to understand where God Himself came from, Feser would have to respond, “No we don’t. He was just There.” What I don’t understand is how God can just be there, but the universe and its antecedents, or the laws of physics, cannot just be there.

Coyne writes as if I have never addressed such questions, when in fact, and as anyone who is actually familiar with my work knows well, I have addressed them many times and at length. First, the answers to these questions have nothing to do with “scripture or revelation,” but rather with philosophical argument. Second, anyone who’s actually bothered to make even a cursory investigation of the relevant arguments would know the answers to Coyne’s other questions. For example, Leibnizian cosmological arguments claim that things that require a cause require one because they are contingent, and thus could in principle have been otherwise, and in particular could have been non-existent. But that which exists in an absolutely necessary or non-contingent way not only need not have a cause but could not have had one, precisely because it could not have been otherwise. Its explanation lies in its own nature rather than in something else. Aristotelian arguments hold that things that require a cause require one because they have potentialities that need to be actualized if they are to exist at all. But that which is purely actualor devoid of potentiality not only need not have a cause but could not have had one, precisely because it lacks any potentiality that could be actualized. Its explanation lies in its own nature as something that is always “already” actual. Neo-Platonic arguments hold that things that require a cause require one because they are composite or made up of parts of some sort, so that those parts must be combined in order for the thing to exist. But that which is absolutely simple or non-composite not only need not have a cause but could not have had one, precisely because it has no parts that could be combined in the first place. And so forth.

The reason why God can be “just there” while a material universe governed by the basic laws of physics cannot, then, is that the former is absolutely necessary while the latter is contingent, that the former is purely actual while the latter is a mixture of actual and potential, that the former is absolutely simple or non-composite while the latter is composed of parts, and so on.

Of course, someone might want to raise various objections against such arguments, but to think that Coyne’s questions are serious objections is like thinking that the question “How could one biological species give rise to another biological species?” is a devastating objection to Darwinism. For of course, the whole point of Darwinism is to show how that question can be answered, so that to raise this question is to missthe whole point rather than to pose a challenge to Darwinism. But in the same way, the whole point of arguments like those put forward by Leibnizians, Aristotelians, Neo-Platonists, Thomists, and others is precisely to answer questions like the ones Coyne raises, so that to raise such questions is merely to miss the whole point rather than to pose a challenge to those theistic arguments.

Coyne’s other objections are equally feeble. He asks:

Where from these regularities can one derive a Beneficent Person without Substance—one who not only loves us all, but demands worship under threat of immolation, and opposes abortion as well?

One problem with this is that Coyne simply assumes that arguments for a First Cause fail to explain why such a cause would have to have the various divine attributes, such as omnipotence, omniscience, perfect goodness, and all the rest. And that is simply false. All the writers I’ve alluded to give arguments that claim to show that such a cause must have various attributes like these, and I have given such arguments myself in many places. (Again, see my book Aquinas, for example.) Coyne offers no reply at all to such arguments, because he is so extremely ignorant of the ideas he is dismissing that he is unaware that the arguments even exist. Second, what on earth do abortion, eternal damnation, etc. have to do with the question of whether a First Cause argument works? Suppose someone proves that there is a First Cause who is omnipotent, omniscient, perfectly good, etc. but does not prove that this First Cause sends anyone to hell or commands us not to have abortions. How exactly would this fail to constitute a refutation of atheism? Atheism, after all, is not merely the thesis that there is no God who damns people eternally or forbids abortion. Atheism is the thesis that there is no God at all. So, to prove that there exists a God of some sort suffices to disprove atheism, even if it does not suffice to prove the truth of some particular religion.

Furthermore, it is quite ridiculous to pretend that any argument for the existence of God has, all by itself, to prove absolutely everythingthat some particular religion has to say. That’s like saying that we shouldn’t accept Darwinian arguments unless they somehow establish the truth of (say) quantum mechanics. Why on earth should anyone suppose that Darwinian arguments should prove that, since they are not even concerned in the first place with the phenomena addressed by quantum theory? And in the same way, why on earth should anyone suppose that a successful First Cause argument should tell us something about abortion, when that isn’t the sort of issue a First Cause argument is addressing in the first place? (And of course, opponents of abortion, and defenders of the claim that there is such a thing as eternal damnation, have other arguments for these claims. They aren’t trying to do everything when giving a First Cause argument, but are merely addressing one specific issue, namely the existence of God.)

Coyne misses the point yet again when, in response to my claim that arguments for God’s existence begin with what science assumes, he writes: “As far as ‘laws governing the world,’ well, that’s a result of science, not an assumption.” Well, yes, the claim that the laws of quantum mechanics (say) govern the world is a result of science, not an assumption. But I wasn’t denying that. The point is rather that when we ask questions like “Why is the world governed by any laws at all rather than no laws?” or “What exactly is it for something to be a law of nature? Is a law of nature a mere regularity? Is it something like a Platonic Form, in which physical things participate? Is it a shorthand description of the way a physical object will operate given its essence?” -- when we ask questions like that, we are asking philosophical or metaphysical questions rather than scientific questions. And those, rather than scientific questions, are the sorts of questions that the main traditional arguments for God’s existence start with.

Finally there is Coyne’s remark that:

For a response to the “Uncaused Cause” argument, and the outmoded notion of Aristotelian causality in modern physics, I refer you to the writings of Sean Carroll… and Carroll’s debate with Feser here.

What can one say to that? Well, first, since whether “Aristotelian causality” really is “outmoded” is, of course, precisely part of what is at issue between Coyne and me, this remark simply begs the question. (And I have written a whole book showing not only that the Aristotelian analysis of causality is not outmoded, but that many contemporary thinkers with no theological or Thomistic axe to grind are returning to it.) Second, I replied to Carroll’s (very poor) arguments in a post over a year ago. Third, I was quite surprised to hear that I had once debated Carroll, since to my knowledge I never have. But if you click on the link Coyne himself provides, you’ll see that it wasn’t me that Carroll debated, but rather William Lane Craig.

So, not only does Coyne not bother to read books and articles of his opponents before commenting on them, it seems he doesn’t even bother to read web pages before linking to and summarizing them.

But hey, don’t let any of the overwhelming evidenceof his actual record as a critic of theology lead you to conclude that Coyne is not in fact very Rational, Evidence-Based, etc. He’s a New Atheist, after all, so he simply must be all those wonderful things. Take it on faith!

[For some previous journeys in the Coyne Clown Car, see “The pointlessness of Jerry Coyne” and “Jerry-built atheism.”]

Published on October 04, 2015 16:33

September 28, 2015

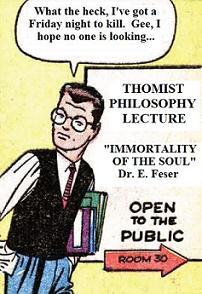

Harvard talk

This Friday, October 2, I will be giving a talk at Harvard University, sponsored by the Harvard Catholic Student Association and the John Adams Society. The topic will be “The Immortality of the Soul.” The event will be in Sever Hall, Room 113, at 8pm.

This Friday, October 2, I will be giving a talk at Harvard University, sponsored by the Harvard Catholic Student Association and the John Adams Society. The topic will be “The Immortality of the Soul.” The event will be in Sever Hall, Room 113, at 8pm.

Published on September 28, 2015 23:14

September 27, 2015

All Scientists Should Beg Lawrence Krauss to Shut the Hell Up Already

In The New Yorker, physicist and professional amateur philosopher Lawrence Krauss calls on all scientists to become “militant atheists.” First club meeting pictured at left. I respond at Public Discourse.For earlier trips in the Krauss Klown Kar, go here, here, and here.

In The New Yorker, physicist and professional amateur philosopher Lawrence Krauss calls on all scientists to become “militant atheists.” First club meeting pictured at left. I respond at Public Discourse.For earlier trips in the Krauss Klown Kar, go here, here, and here.

Published on September 27, 2015 23:09

September 22, 2015

Poverty no, inequality si

Philosopher Harry Frankfurt is famous for his expertise in detecting bullshit. In a new book he sniffs out an especially noxious instance of the stuff: the idea that there is something immoral about economic inequality per se. He summarizes some key points in an excerpt at Bloomberg View and an op-ed at Forbes.

Philosopher Harry Frankfurt is famous for his expertise in detecting bullshit. In a new book he sniffs out an especially noxious instance of the stuff: the idea that there is something immoral about economic inequality per se. He summarizes some key points in an excerpt at Bloomberg View and an op-ed at Forbes.The basic idea is very simple and not really original (I’ve made it before myself, e.g. here) but cannot be restated too often given that so many people appear to lack a grasp of the obvious. It is that equality as such is not a good thing and inequality as such is not a bad thing. Suppose everyone was so poor that it was difficult for anyone even to secure basic needs like food, shelter, and clothing, but no one had any more than anyone else. It would be ridiculous to say “Well, at least there’s a silver lining here for which we can be grateful: Everyone’s equal.” Or suppose everyone had a standard of living at least as good as that of the average millionaire, but some were multi-billionaires. It would be ridiculous to say “It is unjust that so many have to make do with mere millions while a few get to enjoy billions.”

When people complain about economic inequality, this can make sense from a moral point of view only if talk of inequality is really a proxy for something else. Most obviously, it certainly makes sense to lament that some people live in poverty, and it makes sense to call on those who have wealth (and indeed in some cases and to some extent to require those who have wealth) to help those who live in poverty. But the problem here is not that the poor have less than others. The problem is that they have less than they need. The problem, that is to say, is poverty, not inequality.

Similarly, it makes sense to be concerned that some wealthy people have massively greater influence over the political process than other citizens do. And of course it is their greater wealth that accounts for this greater influence. But as Frankfurt says, such influence can be countered “by suitable legislative, regulatory and judicial oversight,” and even if it could not be, it is not the inequality as such that is the problem, but rather something contingently associated with it.

Moreover, it very definitely makes sense to say that there are certain moral hazards associated with being wealthy. A rich man can, if he is not careful, become too absorbed in business and other worldly affairs, too interested in acquiring fine material possessions and insufficiently interested in higher things, and thereby can gain the world at the expense of his soul. Thus did Christ teach that it is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God. But that is not because there is anything wrong with being rich per se, but rather because there is everything wrong with being complacent, materialistic, and this-worldly. And there are many rich people who are none of these things. More to the present point, the problem has nothing to do with inequality.

And yet many people constantly harp on about inequality as such, and not just self-described socialists. For example, liberal political philosopher John Rawls’s famous “difference principle” is not about mitigating poverty or undue political influence per se. While the principle allows for certain inequalities, it also rules out others, not because they entail poverty or undue political influence, but rather simply becausethey are inequalities.

Barack Obama certainly sounded like it is inequality as such that bothers him during a 2008 presidential candidates’ debate. Questioner Charles Gibson noted cases where government tax revenues actually increased when capital gains tax rates went down, and decreased when the rates went up, and asked why, in that case, Obama would favor raising rates. Obama answered:

I would look at raising the capital gains tax for purposes of fairness.

We saw an article today which showed that the top 50 hedge fund managers made $29 billion last year -- $29 billion for 50 individuals. And part of what has happened is that those who are able to work the stock market and amass huge fortunes on capital gains are paying a lower tax rate than their secretaries. That's not fair.

End quote. Now, Obama didn’t challenge Gibson’s factual claims. Even when Gibson pressed him later to justify his answer in light of the fact that dropping the rates might actually increase revenue, Obama simply said: “Well, that might happen, or it might not,” depending on circumstances. But if it did happen, what would be “unfair” about the hedge fund managers making so much more than their secretaries -- given that, by hypothesis, the government would in that case have more tax money to spend on programs which might benefit the secretaries? It is hard to see what Obama could say other than that he thinks the inequality in question is in itself unfair.

From a natural law point of view, we have a grave duty to help those who are in poverty. But we are also obliged to recognize that inequality is simply part of the natural order of things. The two things -- poverty and inequality -- simply have nothing essentially to do with one another. Pope Leo XIII expressed this position eloquently in his 1878 encyclical on socialism, Quod Apostolici Muneris , which vigorously reaffirms the duty of the rich to aid the poor, but also vigorously condemns socialism, which he calls “evil,” “depraved” and a “plague.” And one of the problems he has with it is precisely its egalitarianism:

[W]hile the socialists would destroy the “right” of property, alleging it to be a human invention altogether opposed to the inborn equality of man, and, claiming a community of goods, argue that poverty should not be peaceably endured, and that the property and privileges of the rich may be rightly invaded, the Church, with much greater wisdom and good sense, recognizes the inequality among men, who are born with different powers of body and mind, inequality in actual possession, also, and holds that the right of property and of ownership, which springs from nature itself, must not be touched and stands inviolate. (Emphasis added)

Similarly, in Rerum Novarum (1891), Leo argued that under socialism:

The door would be thrown open to envy, to mutual invective, and to discord; the sources of wealth themselves would run dry, for no one would have any interest in exerting his talents or his industry; and that ideal equality about which they entertain pleasant dreams would be in reality the leveling down of all to a like condition of misery and degradation…

Socialists may in that intent do their utmost, but all striving against nature is in vain. There naturally exist among mankind manifold differences of the most important kind; people differ in capacity, skill, health, strength; and unequal fortune is a necessary result of unequal condition. Such unequality is far from being disadvantageous either to individuals or to the community. Social and public life can only be maintained by means of various kinds of capacity for business and the playing of many parts; and each man, as a rule, chooses the part which suits his own peculiar domestic condition…

But although all citizens, without exception, can and ought to contribute to that common good in which individuals share so advantageously to themselves, yet it should not be supposed that all can contribute in the like way and to the same extent. No matter what changes may occur in forms of government, there will ever be differences and inequalities of condition in the State. Society cannot exist or be conceived of without them…

[N]either justice nor the common good allows any individual to seize upon that which belongs to another, or, under the futile and shallow pretext of equality, to lay violent hands on other people's possessions. (Emphasis added)

Note that the pope was writing at a time when the standard of living of the poor in the Western world was much worse than it is now. And note that he says these things while also reminding us in Quod Apostolici Muneris that the Church:

is constantly pressing on the rich that most grave precept to give what remains to the poor; and she holds over their heads the divine sentence that unless they succor the needy they will be repaid by eternal torments.

and affirming in Rerum Novarum that:

those whom fortune favors are warned that riches do not bring freedom from sorrow and are of no avail for eternal happiness, but rather are obstacles; that the rich should tremble at the threatenings of Jesus Christ -- threatenings so unwonted in the mouth of our Lord -- and that a most strict account must be given to the Supreme Judge for all we possess.

This insistence on sharply distinguishing concern for the poor from any concern for equality as such is just the sort of clear and careful thinking you’d expect from the man who also wrote Aeterni Patris and thereby revived the Scholastic tradition within Catholic intellectual life.

Anyway, it is good to see some clarity on this issue coming also from within mainstream contemporary academic philosophy. Complaining about economic inequality is at best a gigantic time waster that can only promote muddleheaded thinking about poverty and other moral and political issues. At worst, it is a mask for envy, which is evil.

Published on September 22, 2015 19:46

September 16, 2015

Risible animals

Just for laughs, one more brief post on the philosophy of humor. (Two recent previous posts on the subject can be found here and here.) Let’s talk about the relationship between rationality and our capacity to find things amusing.

Just for laughs, one more brief post on the philosophy of humor. (Two recent previous posts on the subject can be found here and here.) Let’s talk about the relationship between rationality and our capacity to find things amusing. First, an important technicality. (And not exactly a funny one, but what are you gonna do?) Recall the distinction within Scholastic metaphysics between the essenceof a thing and its properties or “proper accidents” (where the terms “essence” and “property” are used by Scholastics in a way that is very different from the way contemporary analytic metaphysicians use them). A property or collection of properties of a thing is not to be confused with the thing’s essence or even any part of its essence. Rather, properties flow or follow from a thing’s essence. For example, being four-legged is not the essence of a cat or even part of its essence, but it does follow from that essence and is thus a property of cats; yellowness and malleability are not the essence or even part of the essence of gold, but they flow from that essence and are thus properties of gold; and so forth. A property is a kind of consequenceor byproduct of a thing’s essence, which is why it can easily be confused with a thing’s essence or with part of that essence. But because it is not in fact the same as the essence, it can sometimes fail to manifest if the manifestation is somehow blocked, as injury or genetic defect might result in some particular cat’s having fewer than four legs. (See pp. 230-35 of Scholastic Metaphysics for more detailed discussion.)Now, a stock Scholastic example of a property or proper accident is risibility or the capacity for laughter, which is a property of human beings insofar as it flows from rational animality, which is our essence. (Note that the capacity in question here is not merely the capacity to make a certain laughter-like noise, as a hyena might. Rather, it is the capacity to react with that noise to something regarded as funny.)

Again, it is not our essence or nature to be risible. Rather, our essence is to be rational animals. Still, we exhibit risibility because we are rational. Risibility is a consequence or byproduct of our rational animality. Hence it is because man is a rational animal that he is also a risible animal. The fact that humor does not exist in other, non-rational animals lends credence to this judgment.

Suppose we accept this standard Scholastic view (which is expressed by thinkers like Aquinas). It naturally raises the question of why risibility follows upon rationality. What exactly is the connection between them?

Here it seems to me that the incongruity theoryof humor has an advantage over its rivals, additional to the other advantages which (as I indicted in the earlier posts) I think speak in its favor. The basic idea of the incongruity theory, you’ll recall, is that we find something funny when we detect in it some kind of anomalous juxtaposition or combination of incompatible elements (though as I’ve also noted, this idea requires various qualifications).

Now, notice that, in order to detect such an incongruity, you need to be able to grasp concepts. For example, to see the humor in something like (to take a pretty random example) the “Gandhi II” sequence in the otherwise forgettable “Weird Al” Yankovic movie UHF, you have to grasp the concept of nonviolence, its association with Gandhi, the concept of an action movie, the concept of a movie sequel, etc., and the anomalousness of these being combined in just the way they are in that sequence. But the grasp of concepts is the core of distinctively intellectual or rational capacities. (See this article, reprinted here.) So, the incongruity theory explains the link between rationality and risibility.

Other theories of humor arguably fail in this regard. For example, the release theoryof humor holds that finding something funny involves the release of tension or pent-up feelings. But non-rational animals can experience a kind of tension -- think of a trapped horse panicking in the face of danger, or a frustrated dog trying to get to some food or to the mailman’s leg -- yet exhibit no risibility upon its release.