Edward Feser's Blog, page 81

July 9, 2015

Aristotle’s four causes versus pantheism

For the Platonist, the essences or natures of the things of our experience are not in the things themselves, but exist in the Platonic “third realm.” The essence or nature of a tree, for example, is not to be looked for in the tree itself, but in the Form of Tree; the essence of a man is not to be looked for in any human being but rather in the Form of Man; and so forth. Now, if the essence of being a tree (treeness, if you will) is not to be found in a tree, nor the essence of being a man (humanness) in a man, then it is hard to see how what we ordinarily call a tree really exists as a tree, or how what we call a man really exists as a man. Indeed, the trees and men we see are said by Plato merely imperfectly to “resemble” something else, namely the Forms. So, what we call a tree seems at the end of the day to be no more genuinely tree-like than a statue or mirror image of a tree is; what we call a man seems no more genuinely human than a statue or mirror image of a man is; and so forth.The implication is that trees, men, and the like are not true substances. Only the Forms are true substances. The world of experience is insubstantial, Heraclitean, a realm of confused reflections and shadows of the true, Platonic world. When we add to this the Neo-Platonic/Augustinian thesis that the Forms are really just ideas in the divine intellect, then that divine intellect becomes the true substance. And the insubstantial world of our experience becomes a confused reflection or shadow of God. There is a thin line between such a view and pantheism.

For the Platonist, the essences or natures of the things of our experience are not in the things themselves, but exist in the Platonic “third realm.” The essence or nature of a tree, for example, is not to be looked for in the tree itself, but in the Form of Tree; the essence of a man is not to be looked for in any human being but rather in the Form of Man; and so forth. Now, if the essence of being a tree (treeness, if you will) is not to be found in a tree, nor the essence of being a man (humanness) in a man, then it is hard to see how what we ordinarily call a tree really exists as a tree, or how what we call a man really exists as a man. Indeed, the trees and men we see are said by Plato merely imperfectly to “resemble” something else, namely the Forms. So, what we call a tree seems at the end of the day to be no more genuinely tree-like than a statue or mirror image of a tree is; what we call a man seems no more genuinely human than a statue or mirror image of a man is; and so forth.The implication is that trees, men, and the like are not true substances. Only the Forms are true substances. The world of experience is insubstantial, Heraclitean, a realm of confused reflections and shadows of the true, Platonic world. When we add to this the Neo-Platonic/Augustinian thesis that the Forms are really just ideas in the divine intellect, then that divine intellect becomes the true substance. And the insubstantial world of our experience becomes a confused reflection or shadow of God. There is a thin line between such a view and pantheism.Avoiding such a result requires putting treenessback into trees, humanness back into men, and in general the forms or essences of things back into the things themselves. It requires, in other words, an Aristotelian rather than Platonic conception of form -- form as formal cause, and in particular as substantial form, an immanent or “built in” principle rather than an extrinsic one. Removing formal cause out of the world and putting it elsewhere removes substance out of the world and relocates it elsewhere.

I’ve discussed many times (e.g. here) how a similar result follows when efficient cause is entirely removed from the world and relocated in God, as in occasionalism. Since agere sequitur esse (“action follows being” or “activity follows existence”), if nothing in the world of our experience really does anything and God does everything, then nothing in the world really has any being, and only God has it. What we think of as the world is really just God in action. Again, pantheism.

I’ve also discussed many times (e.g. here) how removing final cause from the world and relocating it entirely in God -- as Paley-style design arguments essentially do -- has the same effect. For efficient cause (the Aristotelian-Thomistic metaphysician argues) presupposes final cause. Remove the latter and you thereby remove the former. And if you relocate them in God you’re implicitly back in an occasionalist position, with pantheism as the sequel -- whether or not you actually draw the inferences. (For further discussion of final causality, efficient causality, and occasionalism, see my essays “Between Aristotle and William Paley: Aquinas’s Fifth Way” and “Natural Theology Must Be Grounded in the Philosophy of Nature, Not in Natural Science, “ both available in Neo-Scholastic Essays .)

So, avoiding occasionalism and thus pantheism also requires affirmation of immanent causal power and immanent teleology -- again, Aristotelian efficient and final causes.

Entirely removing material cause from the world is the most obvious road to pantheism. The material cause of a thing is, to put it crudely, what it’s made of. When you say, as Spinoza and other pantheists do, that the things of our experience are really modes of God, you are in effect making God their material cause. Thus, if instead you say that things have a material cause that is distinct from God and internal to the things themselves, you are thereby rejecting pantheism.

To do that, though, you need (once again) to affirm the other three Aristotelian causes too. Matter without substantial form is pure potentiality, and thus in no way actual. So, for things really to have a material cause immanent to them, they also need an Aristotelian formal cause. They need, as well, immanent teleology or finality, since a potentiality (and thus matter) is always a potentiality forsome outcome or range of outcomes (an extremely wide one in the case of prime matter or pure potentiality for reception of form). And they need also immanent efficient causal power, since (again) agere sequitur esse, so that a material thing that could do nothing would benothing.

The bottom line is that the Aristotelian doctrine of the four causes is essential to avoiding pantheism and views which tend to approximate pantheism (such as Gnosticism).

Why is it important to avoid such views? Well, for one thing, they’re false. The arguments that show that God exists also show (we Aristotelian-Scholastic types claim) that he is utterly distinct from the world. And there are theological dangers in blurring this distinction. Such blurring tends, naturally, either to divinize the world or to secularize God. It divinizes the world to the extent that the blurring leads one to ascribe divine attributes to the world (e.g. ultimacy, holiness, perfect goodness, etc.). It secularizes God to the extent that it leads one to ascribe the world’s characteristics to God (e.g. changeability, temporality, composition of parts as opposed to simplicity). The proximate implication of both tendencies is idolatry; their remote implication is atheism.

Idolatry results either when one directs toward the world attitudes appropriately directed only toward God (as in the nature worship characteristic of extreme environmentalism), or when one’s conception of God is so deficient that one essentially makes of God a creature (as in theological views that attribute to the divine nature a material body, or changeability, or metaphysical parts, or ignorance of future events). (As I’ve argued before, some conceptions of God can be so deficient that even the believer who uses the language of classical theism may in fact be directing his worship toward something other than God.)

One way atheism can result is when the pantheistic “collapse” of God into the world goes so far that the characteristically divine elements of the picture drop out. If it is really the world that is the ultimate reality anyway, then why bother with the “God” stuff? It’s simpler just to speak of the world and leave it at that. Another way atheism can result is when God ends up seeming so creature-like that he ceases to seem God-like. If God is changeable, can learn things like we do, is made up of parts, etc., then he’s really different from us only in degree. He’s like a wizard, or an extraterrestrial, or a superhero, or a ghost or other spirit. And in that case he’s really just another part of the natural world broadly construed -- not really God at all, as traditionally understood -- and the question whether he exists is no more relevant to the truth of naturalism than is the question whether wizards or extraterrestrials exist. (As I’ve argued before, atheism can be a reasonable response to anthropomorphic and otherwise vulgarized conceptions of God.)

Given their theological dangers, then, it is no surprise that the Catholic Church condemns pantheism and related doctrines as heretical. There are also moral dangers. Recall the Scholastic doctrine that being is convertible with goodness. They are really the same thing considered from different points of view. (See my essay “Being, the Good, and the Guise of the Good,” also available in Neo-Scholastic Essays.) A view which denies the reality of some aspect of the world of our experience is thus bound to deny also its goodness.

To be sure, and as I’ve indicated, if your emphasis is on the theme that the material world is really God, then you are bound to exaggerate the goodness of the material world, to the point of idolatry. However, if your emphasis is instead on the theme that the material world per se is unreal, then you are bound to minimize or even deny the goodness of the material world. (As I’ve noted before, views which collapse distinctions tend to be like this -- they can be taken in radically divergent directions.) Now, denigration of the material world is morally disastrous, since it is untrue to human nature. Notoriously, it tends to lead to excess either in the direction of rigorism or in the direction of laxity. For if matter, and thus the body, is unreal, then you might conclude that all indulgence of bodily appetites is gravely evil, since it locks you into unreality; but you might also conclude that all such indulgence is morally trivial, since what happens in the body -- which is unreal -- cannot affect the real you.

So, the implications of getting things wrong in metaphysics can be very far-reaching indeed, contra those fideists, nouvelle theologietypes and other opponents of Scholasticism who dismiss such concerns as just so much hair-splitting. As usual, the Scholastics knew what they were doing. And as usual, their critics do not.

Published on July 09, 2015 12:47

July 6, 2015

Caught in the net

Some of the regular readers and commenters at this blog have started up a Classical Theism, Philosophy, and Religion discussion forum. Check it out.

Some of the regular readers and commenters at this blog have started up a Classical Theism, Philosophy, and Religion discussion forum. Check it out. Philosopher Stephen Mumford brings his Arts Matters blog to an end with a post on why he is pro-science and anti-scientism. Then he inaugurates his new blog at Philosophers Magazine with a post on a new and improved Cogito argument for the reality of causation.

Speaking of which: At Aeon, Mathias Frisch discusses the debate over causation and physics.

The Guardian asks: Is Richard Dawkins destroying his reputation? And at Scientific American, John Horgan says that biologist Jerry Coyne’s new book “goes too far” in denouncing religion.More Catholics defend capital punishment: Moral theologian Fr. Thomas Petri, O.P. is interviewed by Catholic News Agency; and Matthew Schmitz argues, at National Review, that the death penalty is just and merciful.

New paper from Fred Freddoso: “Actus and Potentia: From Philosophy of Nature to Metaphysics.”

David Oderberg’s Philosophical Investigationspaper “All for the Good” is now available online. So is his American Philosophical Quarterly paper “Being and Goodness.”

And a new paper from Tuomas Tahko in Mind: “Natural Kind Essentialism Revisited.”

At Times Higher Education, Richard Smith argues that peer review is based on faith rather than evidence.

John Searle’s new book on perception is reviewed in the Los Angeles Review of Books.

They don’t make public intellectuals like they used to. P. J. O’Rourke on William F. Buckley, Jr. and Norman Mailer.

At Thomistica.net, Steven A. Long on the Supreme Court and “same-sex marriage.” Fr. James Schall on the same subject at Catholic World Report. And Ryan Anderson asks “What next?” in a new book.

At The New Criterion, Anthony Daniels reflects on To Kill a Mockingbird.

Is there a crisis at the edge of physics? Physicists Adam Frank and Marcelo Gleiser opine at The New York Times.

On the pope’s new encyclical: Fr. George Rutler at Crisis, Fr. James Schall at Catholic World Report, and William M. Briggs at The Stream.

Siris on Nigel Warburton’s list of the five greatest women philosophers. (As you’ll see, Warburton is a moron. But you knew that already.)

Philosopher Mark Anderson on Moby Dick as philosophy .

Published on July 06, 2015 11:16

June 29, 2015

Marriage and The Matrix

Suppose a bizarre skeptic seriously proposed -- not as a joke, not as dorm room bull session fodder, but seriously -- that you, he, and everyone else were part of a computer-generated virtual reality like the one featured in the science-fiction movie The Matrix. Suppose he easily shot down the arguments you initially thought sufficient to refute him. He might point out, for instance, that your appeals to what we know from common sense and science have no force, since they are (he insists) just part of the Matrix-generated illusion. Suppose many of your friends were so impressed by this skeptic’s ability to defend his strange views -- and so unimpressed by your increasingly flustered responses -- that they came around to his side. Suppose they got annoyed with you for not doing the same, and started to question your rationality and even your decency. Your adherence to commonsense realism in the face of the skeptic’s arguments is, they say, just irrational prejudice.No doubt you would think the world had gone mad, and you’d be right. But you would still find it difficult to come up with arguments that would convince the skeptic and his followers. The reason is not that their arguments are rationally and evidentially superior to yours, but on the contrary because they are so subversive of all rationality and evidence -- indeed, far more subversive than the skeptic and his followers themselves realize -- that you’d have trouble getting your bearings, and getting the skeptics to see that they had lost theirs. If the skeptic were correct, not even his own arguments would be any good -- their apparent soundness could be just another illusion generated by the Matrix, making the whole position self-undermining. Nor could he justifiably complain about your refusing to agree with him, nor take any delight in your friends’ agreement, since for all he knew both you and they might be Matrix-generated fictions anyway.

Suppose a bizarre skeptic seriously proposed -- not as a joke, not as dorm room bull session fodder, but seriously -- that you, he, and everyone else were part of a computer-generated virtual reality like the one featured in the science-fiction movie The Matrix. Suppose he easily shot down the arguments you initially thought sufficient to refute him. He might point out, for instance, that your appeals to what we know from common sense and science have no force, since they are (he insists) just part of the Matrix-generated illusion. Suppose many of your friends were so impressed by this skeptic’s ability to defend his strange views -- and so unimpressed by your increasingly flustered responses -- that they came around to his side. Suppose they got annoyed with you for not doing the same, and started to question your rationality and even your decency. Your adherence to commonsense realism in the face of the skeptic’s arguments is, they say, just irrational prejudice.No doubt you would think the world had gone mad, and you’d be right. But you would still find it difficult to come up with arguments that would convince the skeptic and his followers. The reason is not that their arguments are rationally and evidentially superior to yours, but on the contrary because they are so subversive of all rationality and evidence -- indeed, far more subversive than the skeptic and his followers themselves realize -- that you’d have trouble getting your bearings, and getting the skeptics to see that they had lost theirs. If the skeptic were correct, not even his own arguments would be any good -- their apparent soundness could be just another illusion generated by the Matrix, making the whole position self-undermining. Nor could he justifiably complain about your refusing to agree with him, nor take any delight in your friends’ agreement, since for all he knew both you and they might be Matrix-generated fictions anyway. So, the skeptic’s position is ultimately incoherent. But rhetorically he has an advantage. With every move you try to make, he can simply refuse to concede the assumptions you need in order to make it, leaving you constantly scrambling to find new footing. He will in the process be undermining his own position too, because his skepticism is so radical it takes down everything, including what he needs in order to make his position intelligible. But it will be harder to see this at first, because he is playing offense and you are playing defense. It falsely seems that you are the one making all the controversial assumptions whereas he is assuming nothing. Hence, while your position is in fact rationally superior, it is the skeptic’s position that will, perversely, appear to be rationally superior. People bizarrely give him the benefit of the doubt and put the burden of proof on you.

This, I submit, is the situation defenders of traditional sexual morality are in vis-à-vis the proponents of “same-sex marriage.” The liberal position is a kind of radical skepticism, a calling into question of something that has always been part of common sense, viz. that marriage is inherently heterosexual. Like belief in the reality of the external world -- or in the reality of the past, or the reality of other minds, or the reality of change, or any other part of common sense that philosophical skeptics have challenged -- what makes the claim in question hard to justify is not that it is unreasonable, but, on the contrary, that it has always been regarded as a paradigm of reasonableness. Belief in the external world (or the past, or other minds, or change, etc.) has always been regarded as partially constitutive of rationality. Hence, when some philosophical skeptic challenges it precisely in the name of rationality, the average person doesn’t know what to make of the challenge. Disoriented, he responds with arguments that seem superficial, question-begging, dogmatic, or otherwise unimpressive. Similarly, heterosexuality has always been regarded as constitutive of marriage. Hence, when someone proposes that there can be such a thing as same-sex marriage, the average person is, in this case too, disoriented, and responds with arguments that appear similarly unimpressive.

Like the skeptic about the external world (or the past, or other minds, or change, etc.) the “same-sex marriage” advocate typically says things he has no right to say consistent with his skeptical arguments. For example, if “same-sex marriage” is possible, why not incestuous marriage, or group marriage, or marriage to an animal, or marriage to a robot, or marriage to oneself? A more radical application of the “same-sex marriage” advocate’s key moves can always be deployed by a yet more radical skeptic in order to defend these proposals. Yet “same-sex marriage” advocates typically deny that they favor such proposals. If appeal to the natural ends or proper functions of our faculties has no moral significance, then why should anyone care about whether anyone’s arguments -- including arguments either for or against “same-sex marriage” -- are any good? The “same-sex marriage” advocate can hardly respond “But finding and endorsing sound arguments is what reason is for!”, since he claims that what our natural faculties and organs are naturally foris irrelevant to how we might legitimately choose to use them. Indeed, he typically denies that our faculties and organs, or anything else for that matter, are really for anything. Teleology, he claims, is an illusion. But then it is an illusion that reason itself is really for anything, including arriving at truth. In which case the “same-sex marriage” advocate has no business criticizing others for giving “bigoted” or otherwise bad arguments. (Why shouldn’t someone give bigoted arguments if reason does not have truth as its natural end? What if someone is just born with an orientation toward giving bigoted arguments?) If the “same-sex marriage” advocate appeals to current Western majority opinion vis-à-vis homosexuality as a ground for his condemnation of what he labels “bigotry,” then where does he get off criticizing past Western majority opinion vis-à-vis homosexuality, or current non-Western moral opinion vis-à-vis homosexuality? Etc. etc.

So, the “same-sex marriage” advocate’s position is ultimately incoherent. Pushed through consistently, it takes down everything, including itself. But rhetorically it has the same advantages as Matrix-style skepticism. The “same-sex marriage” advocate is playing offense, and only calling things into doubt -- albeit selectively and inconsistently -- rather than putting forward any explicit positive position of his own, so that it falsely seemsthat it is only his opponent who is making controversial assumptions.

Now, no one thinks the average person’s inability to give an impressive response to skepticism about the external world (or about the reality of the past, or other minds, etc.) makes it irrational for him to reject such skepticism. And as it happens, even most highly educated people have difficulty adequately responding to external world skepticism. If you ask the average natural scientist, or indeed even the average philosophy professor, to explain to you how to refute Cartesian skepticism, you’re not likely to get an answer that a clever philosopher couldn’t poke many holes in. You almost have to be a philosopher who specializes in the analysis of radical philosophical skepticism really to get at the heart of what is wrong with it. The reason is that such skepticism goes so deep in its challenge to our everyday understanding of notions like rationality, perception, reality, etc. that only someone who has thought long and carefully about those very notions is going to be able to understand and respond to the challenge. The irony is that it turns out, then, that very few people can give a solid, rigorous philosophical defense of what everyone really knows to be true. But it hardly follows that the commonsense belief in the external world can be rationally held only by those few people.

The same thing is true of the average person’s inability to give an impressive response to the “same-sex marriage” advocate’s challenge. It is completely unsurprising that this should be the case, just as it is unsurprising that the average person lacks a powerful response to the Matrix-style skeptic. In fact, as with commonsense realism about the external world, so too with traditional sexual morality, in the nature of the case relatively few people -- basically, traditional natural law theorists -- are going to be able to set out the complete philosophical defense of what the average person has, traditionally, believed. But it doesn’t follow that the average person can’t be rational in affirming traditional sexual morality. (For an exposition and defense of the traditional natural law approach, see “In Defense of the Perverted Faculty Argument,” in Neo-Scholastic Essays .)

Indeed, the parallel with the Matrix scenario is even closer than what I’ve said so far suggests, for the implications of “same-sex marriage” are very radically skeptical. The reason is this: We cannot make sense of the world’s being intelligible at all, or of the human intellect’s ability to understand it, unless we affirm a classical essentialist and teleological metaphysics. But applying that metaphysics to the study of human nature entails a classical natural law understanding of ethics. And that understanding of ethics in turn yields, among other things, a traditional account of sexual morality that rules out “same-sex marriage” in principle. Hence, to defend “same-sex marriage” you have to reject natural law, which in turn requires rejecting a classical essentialist and teleological metaphysics, which in turn undermines the possibility of making intelligible either the world or the mind’s ability to understand it. (Needles to say, these are large claims, but I’ve defended them all at length in various places. For interested readers, the best place to start is, again, with the Neo-Scholastic Essays article.)

Obviously, though, the radically skeptical implications are less direct in the case of “same-sex marriage” than they are in the Matrix scenario, which is why most people don’t see them. And there is another difference. There are lots of people who believe in “same-sex marriage,” but very few people who seriously entertain the Matrix hypothesis. But imagine there was some kind of intense sensory pleasure associated with pretending that you were in the Matrix. Suppose also that some people just had, for whatever reason -- environmental influences, heredity, or whatever -- a deep-seated tendency to take pleasure in the idea that they were living in a Matrix-style reality. Then, I submit, lots of people would insist that we take the Matrix scenario seriously and some would even accuse those who scornfully rejected the idea of being insensitive bigots. (Compare the points made in a recent post in which I discussed the special kind of irrationality people are prone to where sex is concerned, due to the intense pleasure associated with it.)

So, let’s add to my original scenario this further supposition -- that you are not only surrounded by people who take the Matrix theory seriously and scornfully dismiss your arguments against it, but some of them have a deep-seated tendency to take intense sensory pleasure in the idea that they live in the Matrix. That, I submit, is the situation defenders of traditional sexual morality are in vis-à-vis the proponents of “same-sex marriage.” Needless to say, it’s a pretty bad situation to be in.

But it’s actually worse even than that. For suppose our imagined Matrix skeptic and his followers succeeded in intimidating a number of corporations into endorsing and funding their campaign to get the Matrix theory widely accepted, to propagandize for it in movies and television shows, etc. Suppose mobs of Matrix theorists occasionally threatened to boycott or even burn down bakeries, restaurants, etc. which refused to cater the meetings of Matrix theorists. Suppose they stopped even listening to the defenders of commonsense realism, but just shouted “Bigot! Bigot! Bigot!” in response to any expression of disagreement. Suppose the Supreme Court of the United States declared that agreement with the Matrix theory is required by the Constitution, and opined that adherence to commonsense realism stems from an irrational animus against Matrix theorists.

In fact, the current position of opponents of “same-sex marriage” is worse even than that. Consider once again your situation as you try to reason with Matrix theorists and rebut their increasingly aggressive attempts to impose their doctrine via economic and political force. Suppose that as you look around, you notice that some of your allies are starting to slink away from the field of battle. One of them says: “Well, you know, we have sometimes been very insulting to believers in the Matrix theory. Who can blame them for being angry at us? Maybe we should focus more on correcting our own attitudes and less on changing their minds.” Another suggests: “Maybe we’ve been talking too much about this debate between the Matrix theory and commonsense realism. We sound like we’re obsessed with it. Maybe we should talk about something else instead, like poverty or the environment.” A third opines: “We can natter on about philosophy all we want, but the bottom line is that scripture says that the world outside our minds is real. The trouble is that we’ve gotten away from the Bible. Maybe we should withdraw into our own faith communities and just try to live our biblically-based belief in external reality the best we can.”

Needless to say, all of this is bound only to make things worse. The Matrix theory advocate will smell blood, regarding these flaccid avowals as tacit admissions that commonsense realism about the external world really has no rational basis but is simply a historically contingent prejudice grounded in religious dogma. And in your battle with the Matrix theorists you’ll have discovered, as many “same-sex marriage” opponents have, that iron law of politics: that when you try to fight the Evil Party you soon find that most of your allies are card-carrying members of the Stupid Party.

So, things look pretty bad. But like the defender of our commonsense belief in the external world, the opponent of “same-sex marriage” has at least one reliable ally on his side: reality. And reality absolutely always wins out in the end. It always wins at least partially even in the short run -- no one ever is or could be a consistent skeptic -- and wins completely in the long run. The trouble is just that the enemies of reality, though doomed, can do a hell of lot of damage in the meantime.

Published on June 29, 2015 15:30

June 23, 2015

There’s no such thing as “natural atheology”

In his brief and (mostly) tightly argued book

God, Freedom, and Evil

, Alvin Plantinga writes:

In his brief and (mostly) tightly argued book

God, Freedom, and Evil

, Alvin Plantinga writes:[S]ome theologians and theistic philosophers have tried to give successful arguments or proofs for the existence of God. This enterprise is called natural theology… Other philosophers, of course, have presented arguments for the falsehood of theistic beliefs; these philosophers conclude that belief in God is demonstrably irrational or unreasonable. We might call this enterprise natural atheology. (pp. 2-3)

Cute, huh? Actually (and with all due respect for Plantinga), I’ve always found the expression “natural atheology” pretty annoying, even when I was an atheist. The reason is that, given what natural theology as traditionally understood is supposed to be, the suggestion that there is a kind of bookend subject matter called “natural atheology” is somewhat inept. (As we will see, though, Plantinga evidently does not think of natural theology in a traditional way.)

Start with the “theology” part of natural theology. “Theology” means “the science of God,” in the Aristotelian sense of “science” -- a systematic, demonstrative body of knowledge of some subject matter in terms of its first principles. Of course, atheists deny that there is any science of God even in this Aristotelian sense, but for present purposes that is neither here nor there. The point is that a science is what theology traditionally claims to be, and certainly aims to be.

Take the Scholastic theologian’s procedure. First, arguments are developed which purport to demonstrate the existence of a first cause of things. Next, it is argued that when we analyze what it is to be a first cause, we find that of its essence such a cause must be pure actuality rather than a mixture of act and potency, absolutely simple or non-composite, and so forth. Third, it is then argued that when we follow out the implications of something’s being purely actual, absolutely simple, etc. and also work backward from the nature of the effect to the nature of the cause, the various divine attributes (intellect, will, power, etc.) all follow. Then, when we consider the character of the created order as well as that of a cause which is purely actual, simple, etc., we can spell out the precise nature of God’s relationship to that order. (For Aquinas this entails the doctrine of divine conservation and a concurrentist account of divine causality, as opposed to an occasionalist or deist account.) And so forth.

Even someone who doubts that this sort of project can be pulled off can see its “scientific” character. The domain studied is, of course, taken to be real, and its reality is defended via argumentation which claims to be demonstrative. Further argumentation of a purportedly demonstrative character is put forward in defense of each component of the system, and the system is very large, purporting to give us fairly detailed knowledge not only of the existence of God, but of his essence and attributes and relation to the created order. Moreover, the key background notions (the theory of act and potency, the analysis of causation, the metaphysics of substance, etc.) are tightly integrated into a much larger metaphysics and philosophy of nature, so that natural theology is by no means an intellectual fifth wheel, arbitrarily tacked on for merely apologetic purposes to an already complete and self-sufficient body of knowledge.

Rather, its status as the capstone of human knowledge is clear. The natural sciences as we understand them today (physics, chemistry, biology, etc.) are grounded in principles of the philosophy of nature, whose subject matter concerns what any possible natural science must take for granted. Philosophy of nature in turn rests on deeper principles of metaphysics, whose subject matter is being as such (rather than merely material or changeable being, which is the subject matter of philosophy of nature; and rather than the specific sort of material or changeable world that actually exists, which is the subject matter of natural science). Natural theology, in turn, follows out the implications of the fundamental notions of philosophy of nature and metaphysics (the theory of act and potency, etc.) and offers ultimate explanations.

Again, you don’t have to think any of this works in order to see that what it aspires to is a kind of science. By contrast, what Plantinga calls “atheology” could not possibly be any kind of science, and doesn’t claim to be. For the “atheologian” doesn’t claim to be studying some domain of reality and giving us systematic knowledge of it. On the contrary, his entire aim is to show that there is no good reason to think the domain in question is real. You can have a “science” only of what exists, not of what doesn’t exist. Otherwise “aunicornology” would be just as much a science as ichthyology or ornithology is. Ichthyology and ornithology are sciences because there are such things as fishes and birds, and there is systematic knowledge to be had about what fishes and birds are like. “Aunicornology” is not a science, because there is in the strict sense no such thing as a systematic body of knowledge of the nonexistence of unicorns, or of the nonexistence of anything else for that matter. Suppose someone denied the existence of fishes and tried to offer arguments for their nonexistence. It would hardly follow that he is committed to practicing something called “aichthyology” in the sense of a systematic body of knowledge of the nonexistence of fish.

Note that I am not saying anything here that an atheist couldn’t agree with. The claim is not that one couldn’t have solid arguments for atheism (though of course I don’t think there are any). The point is rather that even if there were solid arguments, they wouldn’t give you any kind of “science” in the sense of a systematic body of knowledge of some domain of reality. Rather, what they would do is to show that some purported domain of reality doesn’t really exist.

So, it is inept to think that if there is such a thing as theology, then there must be some bookend subject matter called “atheology” -- again, at least if we are using “theology” the way it has traditionally been understood. Now let’s turn to the “natural” part of natural theology. “Natural” as opposed to what? Well, the usual answer, of course, is “natural as opposed to revealed.” The idea is that whereas some knowledge about God and his nature is available to us because he has specially disclosed it to us through (say) the teachings of a prophet whose authority is backed by miracles -- where such knowledge constitutes “revealed theology” -- there is other knowledge about God and his nature that is available to us just by applying our natural powers of reason to understanding the world, say by reasoning from the existence of contingent things to a necessary being as their cause (or whatever). That’s where “natural theology” comes in.

So, if that’s what natural theology is, what would “natural atheology” be? “Natural” as opposed to what? As opposed to “revealed atheology”? But of course, the idea of “revealed atheology” would be absurd. It makes no sense to say that there is such a thing as knowledge of the non-existence of God which has been revealed to us by God. The “natural versus revealed” distinction simply doesn’t apply to anything an atheist might affirm, the way it does apply to what the theist would affirm. So, again, it is inept to suppose that if there is such a thing as natural theology, then there must be some bookend field of study we might label “natural atheology.”

To be sure, there is another possible reading of the “natural” in natural theology. We might think of it on analogy with the “natural” in natural law. The idea of natural law, of course, is the idea that what is good or bad and right or wrong for us is grounded in our nature, and that knowledge of good and bad and right and wrong can therefore be derived from the study of that nature. So, perhaps we might also think of natural theology as knowledge of God that is available to us given our nature. In particular, we might say that since the natural end or final cause of reason is to know the causes of things, and the ultimatecause of things is God, the ultimateend of reason is to know God. Indeed, Scholastic thinkers like Aquinas would say exactly this.

Could there be such a thing as “natural atheology” in some parallel sense? But that would entail that “atheology” -- denial of the existence of God -- is in some sense the natural end of reason. And certainly no Scholastic would say that. Plantinga himself, though he is no Scholastic, would not say that. Indeed, I can’t think of any proponent of natural theology or revealed theology who would say that denying God’s existence is or could be the naturalend of reason. (I suppose some of them might say that fallen reason tends toward atheism, but that’s a very different idea from the claim that the natural tendency of reason is toward atheism.) So, once again, it’s hard to see what it could mean to describe something as “natural” atheology.

So, the expression “natural atheology” is inept. But is this a big deal? Well, I don’t know if it’s a big deal, and, if so, how big exactly. But it’s not insignificant. Because the problem is not just that the expression is, for the reasons given, semantically awkward. There is also a substantive issue implicit in what I’ve been saying. The expression “natural theology” is, as what I’ve said indicates, rich in meaning. Historically, it conveyed, and was meant to convey, something important about our knowledge of God -- again, that that knowledge is scientific in the sense described above, and that much of it can be had apart from revelation. Plantinga’s neologism obscures all that. Consider what else he says in the passage quoted earlier:

The natural theologian does not, typically, offer his arguments in order to convince people of God’s existence… Instead the typical function of natural theology has been to show that religious belief is rationally acceptable. (p. 2)

The idea here seems to be that natural theology is essentially a grab bag of moves one might make in order to counter atheist accusations to the effect that belief in God is irrational. Its point is essentially defensive, rather than something that makes a positive and fundamental contribution to human knowledge.

Now, this might be an accurate description of the Alvin Plantinga approach to natural theology. But it is most definitely notan accurate description of the approach taken to natural theology by pagan philosophers like Aristotle or Plotinus, medieval philosophers like Maimonides, Avicenna, and Aquinas, modern rationalists like Leibniz and Wolff, or most other proponents of natural theology historically -- who thought that the key arguments of natural theology could and should be convincing even to someone who does not initially believe that God exists, and who thought that natural theology does provide a positive, fundamental contribution to the body of human knowledge.

Now, if you think that “natural theology” is nothing more than a label for the religious believer’s unsystematic grab bag of apologetic arguments, then it is clear why you might also think that “natural atheology” is an apt label for an atheist’s own grab bag. But from the point of view of those who endorse the traditional and much more robust understanding of natural theology, you will thereby perpetuate a mistaken understanding of what natural theology is, and obscure that older conception. (You will also encourage the pop apologist in his bad habit of deploying any old argument he thinks might win converts, whether or not it’s actually a good argument at the end of the day -- thereby helping to perpetuate the mistaken idea that apologetics is essentially an intellectually dishonest form of rhetoric rather than genuine philosophy. I criticized this kind of apologetics in an earlier post.)

While I’m on the subject of God, Freedom, and Evil, I might as well note a couple of other peeves. In the introduction to the book, Plantinga alludes to:

supersophisticates among allegedly Christian theologians who proclaim the liberation of Christianity from belief in God, seeking to replace it by trust in “Being itself” or the “Ground of Being” or some such thing. (p. 1)

This appears to be a reference both to the then-trendy “Death of God theology” and to the existentialist theology of Paul Tillich. Naturally, like Plantinga, I am not a fan of either one. However, the derisive reference to “’Being itself’ or the ‘Ground of Being’ or some such thing” is telling. The “some such thing” makes it sound as if “Being itself” and related notions are flakey novelties introduced by modernist theologians. Nothing could be further from the truth. Indeed, that God is “Subsistent Being Itself” rather than merely one being alongside others is at the heart of classical theism as expressed by thinkers like Aquinas and other Scholastics. (As I discussed in an earlier post, while Tillich’s use of these notions is highly problematic, he is merely borrowing this language, perfectly innocent in itself, from the classical tradition.) In fact it is Plantinga’s own “theistic personalism” (to borrow Brian Davies’ label for Plantinga’s view), which rejects the core doctrines of classical theism, which is the novelty. (I’ve discussed the stark differences between classical theism and theistic personalism in a number of posts.)

Then there is Plantinga’s discussion in God, Freedom, and Evil of Aquinas’s Third Way. He is very critical of the argument, but in my view badly misunderstands it. Plantinga wonders whether, by a “necessary being,” Aquinas means one that exists in every possible world; puzzles over what it could possibly mean to say that something derives its necessity from another; accuses Aquinas of committing a quantifier shift fallacy; and so on. As I show at pp. 90-99 of my book Aquinas , when one reads the Third Way in light of the background Aristotelian-Scholastic metaphysics Aquinas is working with, it is clear that all of this is quite misguided. (Even J. L. Mackie’s discussion of the argument in The Miracle of Theismis in my view better than Plantinga’s treatment here. Though in fairness to Plantinga, he offers a more substantive treatment in God and Other Minds.)

None of this is meant to deny the importance of the central themes of God, Freedom, and Evil -- namely, Plantinga’s distinctive treatments of the ontological argument and of the problem of evil -- which are, of course, very clever and philosophically interesting. But even here, Thomists and other classical theists will find much to disagree with, and it cannot be emphasized too often that the basic philosophical assumptions that inform much contemporary philosophy of religion are radically different from those that guided the greatest philosophical theists of the past.

(See also my post on Plantinga’s ontological argument, my review of his book Where the Conflict Really Lies, and my remarks on his review of Thomas Nagel’s Mind and Cosmos.)

Published on June 23, 2015 16:44

June 18, 2015

Love and sex roundup

Current events in the Catholic Church and in U.S. politics being as they are, it seems worthwhile to put together a roundup of blog posts and other readings on sex, romantic love, and sexual morality as they are understood from a traditional natural law perspective.

Current events in the Catholic Church and in U.S. politics being as they are, it seems worthwhile to put together a roundup of blog posts and other readings on sex, romantic love, and sexual morality as they are understood from a traditional natural law perspective. First and foremost: My essay “In Defense of the Perverted Faculty Argument” appears in my new anthology Neo-Scholastic Essays . It is the lengthiest and most detailed and systematic treatment of sexual morality I have written to date. Other things I have written on sex, romantic love, and sexual morality are best read in light of what I have to say in this essay.A brief summary of its contents might be useful. The essay has five sections. After the first, which is the introduction, the second section provides an overview of traditional natural law theory and its metaphysical foundations. The third section spells out the general approach that traditional natural law theory takes toward sex and romantic love, and shows how the key claims of traditional sexual morality vis-à-vis adultery, fornication, homosexuality, etc. follow from that approach. As I also explain there, however, understanding certain specific aspects of traditional sexual morality (such as the absolute prohibition of contraception) requires an additional thesis, which is where the perverted faculty argument -- which is (contrary to the usual caricatures) not the whole of the traditional natural law approach to sex, but rather merely one element of it -- comes into play. Section four provides a detailed exposition and defense of that argument, answering all of the usual objections. Along the way, there is substantive discussion of questions about what is permitted within marital sexual relations, and it is shown that the perverted faculty argument is not as restrictive here as liberals and more rigorist moralists alike often suppose. Finally, in the fifth section, I argue that purported alternative Catholic defenses of traditional sexual morality -- personalist arguments, and “new natural law” arguments -- are not genuine alternatives at all. Invariably they implicitly presuppose exactly the traditional natural law “perverted faculty” reasoning that they claim to eschew. Moreover, the “new natural law” arguments have grave deficiencies of their own.

An excerpt from this essay appeared under the title “The Role of Nature in Sexual Ethics” in The National Catholic Bioethics Quarterly in 2013. A longer excerpt was presented under the title “Natural Law and the Foundations of Sexual Ethics” in the talk I gave at the Princeton Anscombe Society in April of this year. But those interested in seeing the complete essay should get hold of Neo-Scholastic Essays. (I also presented some of the relevant ideas in The Last Superstition, at pp. 132-53. But the new essay goes well beyond what I had to say there.)

Over the years I’ve addressed various aspects of these issues here at the blog. Here are the main posts:

The metaphysics of romantic love [A discussion of sexual desire and romantic longing from the point of view of natural law and Catholic theology]

The metaphysics of Vertigo [A philosophical and theological reflection on the nature of romantic obsession, with Hitchcock’s Vertigo as a case study]

What’s the deal with sex? Part I [On three aspects of sex which clearly give it special moral significance, contra contemporary “ethicists” like Peter Singer]

What’s the deal with sex? Part II [A discussion of the effects of sexual vice on one’s character, whether the disorder be one of excess -- which results in what Aquinas calls the “daughters of lust” -- or one of deficiency, which involves what Aquinas calls a “vice of insensibility”]

Sexual cant from the asexual Kant [On the trouble with Kantian and personalist approaches to sex and sexual morality]

Alfred Kinsey: The American Lysenko [A 2005 article from the online edition of City Journal]

I’ve also written several posts over the years about controversies over sexual morality as they have arisen in the U.S. political context, and in the Catholic context:

Some thoughts on the Prop 8 decision [On the “same-sex marriage” controversy, its unavoidable connection to deeper disagreements about sexual morality, and the phoniness of liberal neutrality]

Contraception, subsidiarity, and the Catholic bishops [On the way in which the failure of Catholic bishops to uphold Catholic teaching on contraception and subsidiarity facilitated the U.S. federal government’s attempted contraceptive mandate]

Hitting Bottum [On the incoherence of conservative Catholic writer Joseph Bottum’s attempt to justify capitulating on “same-sex marriage”]

Nudge nudge, wink wink [How some churchmen’s ambiguous statements on homosexuality, divorce, etc. inevitably “send the message” that Catholic teaching on these matters can and will change, whether or not these churchmen intend to send that message]

The two faces of tolerance [On “same-sex marriage,” the sexual revolution more generally, and the totalitarian tendencies of egalitarianism]

Though the natural law defense of traditional sexual morality is the most fundamental defense, there are other approaches to defending it. One of these is the appeal to the wisdom embodied in tradition in general, as that idea has been spelled out by writers like Edmund Burke and F. A. Hayek. In my 2003 Journal of Libertarian Studiesarticle “Hayek on Tradition,” I expound and defend this approach to tradition and discuss how it applies to questions about sexual morality.

Finally, for you completists out there, some additional golden oldies. Ten years ago, at the long defunct Right Reason group blog, I wrote up a series of posts on natural law and sexual morality, which can still be accessed via archive.org:

Natural ends and natural law, Part I

Natural ends and natural law, Part II

The posts got a fair amount of attention. Andrew Sullivan politely and critically responded to them in his book The Conservative Soul, and I offered a reply to Sullivan here:

Reply to Sullivan on natural law

I wouldn’t now formulate some of the key metaphysical points exactly the way I did in those decade-old posts, however, so -- again -- see “In Defense of the Perverted Faculty Argument” in Neo-Scholastic Essays for an up-to-date treatment.

Published on June 18, 2015 11:22

June 15, 2015

Cross on Scotus on causal series

Duns Scotus has especially interesting and important things to say about the distinction between causal series ordered accidentally and those ordered essentially -- a distinction that plays a key role in Scholastic arguments for God’s existence. I discuss the distinction and Scotus’s defense of it in

Scholastic Metaphysics

, at pp. 148-54. Richard Cross, in his excellent book,

Duns Scotus

, puts forward some criticisms of Scotus’s position. I think Cross’s objections fail. Let’s take a look at them.First, a brief review of the distinction. As longtime readers are aware, the key difference between the two kinds of causal series has to do with whether their members have their causal power in a derived or underived way. Consider the causal sequence: x → y → z. The series is essentially ordered if, in the very act of causing z, y borrows from x the power to do so. Hence, in the stock example, the stick pushes the stone only insofar as it derives from the hand the power to push it. A series is accidentally ordered if, in the act of causing z, y does not borrow from x the power to do so. Hence, in the stock example, a son can beget a son of his own whether or not his own father is still alive. (I’ve discussed this distinction at greater length in earlier posts, such as this one, and in various books and articles. Again, see Scholastic Metaphysicsfor detailed discussion.)

Duns Scotus has especially interesting and important things to say about the distinction between causal series ordered accidentally and those ordered essentially -- a distinction that plays a key role in Scholastic arguments for God’s existence. I discuss the distinction and Scotus’s defense of it in

Scholastic Metaphysics

, at pp. 148-54. Richard Cross, in his excellent book,

Duns Scotus

, puts forward some criticisms of Scotus’s position. I think Cross’s objections fail. Let’s take a look at them.First, a brief review of the distinction. As longtime readers are aware, the key difference between the two kinds of causal series has to do with whether their members have their causal power in a derived or underived way. Consider the causal sequence: x → y → z. The series is essentially ordered if, in the very act of causing z, y borrows from x the power to do so. Hence, in the stock example, the stick pushes the stone only insofar as it derives from the hand the power to push it. A series is accidentally ordered if, in the act of causing z, y does not borrow from x the power to do so. Hence, in the stock example, a son can beget a son of his own whether or not his own father is still alive. (I’ve discussed this distinction at greater length in earlier posts, such as this one, and in various books and articles. Again, see Scholastic Metaphysicsfor detailed discussion.)Cross labels an essentially ordered series of causes an “E-series,” and an accidentally ordered series of causes an “A-series.” His main criticism of Scotus’s use of the notion of an E-series is contained in the following passage:

In the late Reportatio (closely paralleled in the Ordinatio) Scotus argues from the following premise: “In essentially ordered causes… each second cause, in so far as it is causing, depends upon a first.” Put in this way, it follows straightforwardly that there must be a first member of an E-series. But the premise is question-begging, and I can see no reason for wanting to accept it. It requires that a first cause is necessary as well as sufficient for any effect in an E-series. But this is not so… [I]n any causal series there is a sense in which the existence of earlier causes is necessary for the existence of later causes. But we cannot infer from this that a first cause is necessary for some effect. There are sometimes many different ways in which the same effect can be produced.

Taking account of this objection, we could loosely reformulate the premise as follows: “In essentially ordered causes, any later cause, in so far as it is causing, depends upon an earlier cause.” Put thus, the premise looks wholly plausible. But there would be no problem with an infinite E-series thus construed. Howsoever many prior causes there were, any one of them would be logically sufficient for any later effect. (p. 19)

There are several things to say about this. To begin with, note that there are two senses in which something might be characterized as “first.” We might mean that it comes at the head of some sequence. This is what we have in mind when we say that Fred was first in line for the movie, or that Ethel was the first to arrive at the party. We mean first as opposed to second, third, fourth, fifth, etc. Let’s use “firsts” when what is intended is this sequential sense of the word. But we might mean instead, when we characterize something as “first,” that it is in some way more fundamental or essential relative to other things, or that in some respect it has a higher status. This is what we have in mind when we characterize something as being “of the first rank,” when we describe someone as “first among equals,” or when we give the title “First Lady” to the wife of the President of the United States. We mean first in the sense of principal or primary as opposed to secondary. Let’s use “firstf” when what is intended is this sense of the word, which involves some kind of fundamentality or eminence.

Now, something can be firsts without being firstf, and something can be firstf without being firsts. The U.S. Army Chief of Staff would be the firstf soldier in the Army even if he were not the firststo join the Army, indeed even if he were the last to join. And in theory a certain Army private could be the firsts soldier insofar as he joined before any other living soldier did, even though he has never gotten any further in rank and thus is far from being firstf. The FirstfLady of the United States is obviously not the firsts lady ever to have lived in the United States. Descartes’ Meditations on First Philosophy is not concerned with the firsts philosophy ever devised by a philosopher (Thales, say) but rather with firstfphilosophy, i.e. that branch of philosophy which deals with the most fundamental philosophical issues. When First Comics was founded in the 1980s, the company was not claiming to be the firsts comic book company, but rather aspiring to be the firstf comic book company. And so forth.

Now, suppose that when Scotus or some other Scholastic says that “in essentially ordered causes… each second cause, in so far as it is causing, depends upon a first,” what is meant is firsts. Then it is easy to see why Cross would raise the objections he does. For why should a second (or third, or fourth) cause require a firsts? If Scotus were just stipulating that you couldn’t have a second, third, fourth, etc. cause without a firstscause, then he would be begging the question (as Cross accuses him of doing), since Scotus’s critic doesn’t see why a firsts cause is needed and hasn’t been given a reason to change his mind. And if Scotus reformulates his position as the claim that “in essentially ordered causes, any later cause, in so far as it is causing, depends upon an earlier cause,” then (as Cross indicates) even if this is true, it will not entail that there is a firsts cause.

The problem, though, is that this is simply notwhat Scotus and other Scholastics mean. In the proposition that “in essentially ordered causes… each second cause, in so far as it is causing, depends upon a first,” what is mean is firstf, not firsts. In particular, the claim is that in essentially ordered causal series, causes which have their causal power in a merely secondary or derivative way require a cause which has its causal power in a primary or underivative way. And there is nothing question-begging about that, even if the point needs greater spelling out than Scotus gives it in that one quoted sentence considered in isolation.

When I point out that a stick cannot move a stone by itself but requires something else to impart to it the power to move stones and other things, I am not begging any questions but rather saying something that no one would deny, not only because we all know from experience that sticks don’t move stones by themselves but also because it is evident from the nature of sticks that the reason they don’t in fact move other things by themselves is that they can’t do so. For they simply don’t have the built-in power to do so. Neither am I begging any questions when I point out that the same thing is true of the arm which movies the stick. Like sticks, arms all by themselves not only never do move other things but couldn’t do so given their nature.

Nor am I begging any questions when I go on to conclude that such a series of causes requires something which imparts the power to move things without deriving it from anything else -- for example, a human being, who can use his arm to move the stick to move the stone, without the need for someone else to pick him up and move him while he does so. Here too I am saying something which is not only obvious from experience, but also evident from reflection on the natures of the causes involved. For one thing, human beings have by nature a built-in power of movement that sticks, stones, and arms do not. For another thing, in general what is derivative presupposes that from which it is derived. Even Scotus’s critic would have to admit that the stick’s movement of the stone cannot be accounted for unless we appeal to something from which the stick derives its causal power, such as the arm. And the critic would have to admit that accounting for the arm’s movement requires a similar appeal, for the same reason. But any further member we posit which, like the stick and the arm, lacks built-in power, will just raise the same problem all over again. So, we cannot account for the motion we started out with -- that of the stick as it moves the stone -- until we get to something which does have built-in or underivative causal power.

Positing an infinite regress of derivative causes is no alternative. Suppose I owe you money, you demand that I pay up immediately, and I offer you an IOU instead. Suppose you refuse to accept it on the grounds that you doubt I’ll ever be able to back it up with real money. Suppose that, in order to ease your doubts, I offer you a second IOU to back up the first. Naturally, you refuse that IOU too, and on the same grounds. Now it would be absurd to suppose that if I go on ( Dumb and Dumber style ) to offer you an infinite series of IOUs, each backing up the previous one, then you will suddenly have a reason to abandon your doubts and accept my IOUs. Similarly, it is absurd to suppose that positing an infinite regress of causes having merely derivative causal power somehow solves the problem that positing one, two, three, etc. derivative causes was unable to solve.

In any event, even if someone were for some reason to try to resist this line of argument, there is nothing question-begging about it, and neither does it fail to offer a reason for thinking that there must be a cause with built-in or underived causal power. So, Cross’s charge that Scotus either begs the question or fails to give any reason for supposing that an E-series requires a first member cannot be maintained, at least if what Scotus has in mind (as he surely does) is a firstfcause and not merely a firsts cause.

What about Cross’s point that “we cannot infer… that a first cause is necessary for some effect [since] there are sometimes many different ways in which the same effect can be produced”? The idea here seems to be that even if in the case of the stick moving the stone (say), the stick does so only because a person moves the stick with his arm, there are nevertheless other ways in which the stick might be moved. For example, it could be tied to some machine which moves it about, and by which it is able to move a stone. But the problem with this objection is that it shows only that, in the E-series in question, this or that particularfirstf cause is not necessary. It does not show that some firstfcause or other is not necessary in any E-series.

Cross raises a couple of further objections in an endnote. First, he suggests that:

We might be inclined to argue that, if there were no first cause to an E-series, we could not find the real cause of any effect… Richard Swinburne notes that this argument falls victim to what he labels the ‘compIetist fallacy’: if y causes z, then it really does explain the existence of z, even if y itself requires explanation. (pp. 161-62; Cross is referring to remarks made by Swinburne in the second edition of his book The Existence of God)

The trouble with this objection is that to say that something is not a “complete” cause is simply not the same thing as to say that it is not a “real” cause, and to say that something is not a “complete” explanation is simply not the same thing as saying that it is not a “real” explanation. Does the stick in our example reallymove the stone? Of course. Does its motion really explain the motion of the stone? Yes indeed. But is the stick the completecause of the motion of the stone? Of course not. And neither does its motion completely explain that of the stone, precisely because it would have no power to move the stone at all if it did not derive it from the person who uses it to move the stone.

Finally, Cross says:

Scotus's argument is made more complicated by his claim that even if per impossibile there were an infinite series of causes, each one would have to depend on some first cause that was outside the series… But this just blurs the distinction between an E-series and an A-series. On Scotus's initial definitions, an E-series will be self-sufficient; it will not depend on any cause outside itself. (p. 162)

The reason Cross thinks this blurs the distinction between an E-series and an A-series, it seems, is that Scotus and other Scholastics hold that an A-series need not have a first member, whereas an E-series must have one. But Scotus’s allowing for the sake of argument that an E-series might regress infinitely will seem to blur the distinction between an E-series and an A-series only if we fail to keep in mind the distinction between a firsts cause and a firstfcause. When Scotus allows for the sake of argument that an E-series might regress infinitely, he is not saying, even for the sake of argument, that an E-series might lack a firstfcause. Rather, he is allowing for the sake of argument that it might lack a firsts cause, and saying that even if it lacked one, it would still require a firstf cause.

For example, suppose the stone was being pushed by a stick, which was being pushed by another stick, which was being pushed by yet another stick, and so on ad infinitum. Such a series would not have a firstsmember. But there would still have to be a firstf member outside the series to impart motion to it, because of themselves a mere series of sticks, however long, would have no power to move at all.

So, Cross’s objections all fail. But someone might still wonder how all this supports an argument for God’s existence. For of course, Scotus, like Aquinas and other Scholastics, intends to argue for a single and divine first cause. Yet a person who moves a stone with a stick is only one firstf cause alongside many others, and a non-divine one at that.

But pointing out that an E-series must have a firstf member, and illustrating the idea with the stick example, is by no means the whole of a First Cause argument for God’s existence. It is only part of a much larger line of argument. For one thing, while a person who moves a stone with a stick is a firstf cause relative to that particular series, it does not follow that he is a firstf cause absolutely, full stop. Indeed, relative to other E-series, he will himself be an effect. For example, his existence at any moment depends upon the existence and proper configuration of his micro-level material parts. And in a metaphysically more fundamental way, it depends on his substantial form being conjoined with prime matter, and his essence being conjoined with an act of existence. The regress this entails will be vicious unless it terminates in a cause which is purely actual and thus need not be actualized by anything else. And a purely actual cause turns out on analysis to have the divine attributes.

But that’s a whole other story (for which see chapter 3 of Aquinas and several of the essays on natural theology in Neo-Scholastic Essays ).

Published on June 15, 2015 10:23

June 10, 2015

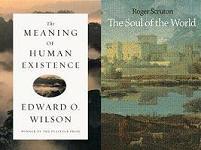

Review of Wilson and Scruton

In the Spring 2015 issue of the Claremont Review of Books, I review Edward O. Wilson’s

The Meaning of Human Existence

and Roger Scruton’s

The Soul of the World

.

In the Spring 2015 issue of the Claremont Review of Books, I review Edward O. Wilson’s

The Meaning of Human Existence

and Roger Scruton’s

The Soul of the World

.

Published on June 10, 2015 00:14

June 7, 2015

Neo-Scholastic Essays

I am pleased to announce the publication of

Neo-Scholastic Essays

, a collection of previously published academic articles of mine from the last decade, along with some previously unpublished papers and other material. Here are the cover copy and table of contents:

I am pleased to announce the publication of

Neo-Scholastic Essays

, a collection of previously published academic articles of mine from the last decade, along with some previously unpublished papers and other material. Here are the cover copy and table of contents: In a series of publications over the course of a decade, Edward Feser has argued for the defensibility and abiding relevance to issues in contemporary philosophy of Scholastic ideas and arguments, and especially of Aristotelian-Thomistic ideas and arguments. This work has been in the vein of what has come to be known as “analytical Thomism,” though the spirit of the project goes back at least to the Neo-Scholasticism of the period from the late nineteenth century to the middle of the twentieth.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Preface

Acknowledgments

Metaphysics and philosophy of nature

1. Motion in Aristotle, Newton, and Einstein

2. Teleology: A Shopper’s Guide

3. On Aristotle, Aquinas, and Paley: A Reply to Marie George

Natural theology

4. Natural Theology Must Be Grounded in the Philosophy of Nature, Not in Natural Science

5. Existential Inertia and the Five Ways

6. The New Atheists and the Cosmological Argument

7. Between Aristotle and William Paley: Aquinas’s Fifth Way

8. Why McGinn is a Pre-Theist

9. The Road from Atheism

Philosophy of mind

10. Kripke, Ross, and the Immaterial Aspects of Thought

11. Hayek, Popper, and the Causal Theory of the Mind

12. Why Searle is a Property Dualist

Ethics

13. Being, the Good, and the Guise of the Good

14. Classical Natural Law Theory, Property Rights, and Taxation

15. Self-Ownership, Libertarianism, and Impartiality

16. In Defense of the Perverted Faculty Argument

Published on June 07, 2015 16:39

June 2, 2015

Religion and superstition

The Routledge Handbook of Contemporary Philosophy of Religion

, edited by Graham Oppy, has just been published. My essay “Religion and Superstition” is among the chapters. The book’s table of contents and other details can be found here. (The book is very expensive. But I believe you should be able to read all or most of my essay via the preview at Google Books.)

The Routledge Handbook of Contemporary Philosophy of Religion

, edited by Graham Oppy, has just been published. My essay “Religion and Superstition” is among the chapters. The book’s table of contents and other details can be found here. (The book is very expensive. But I believe you should be able to read all or most of my essay via the preview at Google Books.)

Published on June 02, 2015 00:18

May 30, 2015

Aristotle watches Blade Runner

You can never watch Blade Runner too many times, and I’m due for another viewing. In D. E. Wittkower’s anthology

Philip K. Dick and Philosophy

, there’s an article by Ross Barham which makes some remarks about the movie’s famous “replicants” and their relationship to human beings which are interesting though, in my view, mistaken. Barham considers how we might understand the two kinds of creature in light of Aristotle’s four causes, and suggests that this is easier to do with replicants than with human beings. This is, I think, the reverse of the truth. But Barham’s reasons are not hard to understand given modern assumptions (which Aristotle would reject) about nature in general and human nature in particular.Barham suggests that, where replicants are concerned, a four-cause analysis would look something like this: their efficient cause is the Tyrell Corporation and its engineers; their material cause is to be found in the biological and mechanical constituents out of which they are constructed; their formal cause is the human-like pattern on which the Tyrell Corporation designed them; and their final cause is to function as human-like slave laborers.

You can never watch Blade Runner too many times, and I’m due for another viewing. In D. E. Wittkower’s anthology

Philip K. Dick and Philosophy

, there’s an article by Ross Barham which makes some remarks about the movie’s famous “replicants” and their relationship to human beings which are interesting though, in my view, mistaken. Barham considers how we might understand the two kinds of creature in light of Aristotle’s four causes, and suggests that this is easier to do with replicants than with human beings. This is, I think, the reverse of the truth. But Barham’s reasons are not hard to understand given modern assumptions (which Aristotle would reject) about nature in general and human nature in particular.Barham suggests that, where replicants are concerned, a four-cause analysis would look something like this: their efficient cause is the Tyrell Corporation and its engineers; their material cause is to be found in the biological and mechanical constituents out of which they are constructed; their formal cause is the human-like pattern on which the Tyrell Corporation designed them; and their final cause is to function as human-like slave laborers. With human beings, Barham says, things are different. Here, he thinks, the analysis looks like this: their efficient cause is, proximately, their parents, and remotely, evolution; their material cause is the biochemical matter out of which they are constituted; and their formal cause is the “blueprint” to be found in their DNA. But with human beings, Barham says, it’s not so clear what their final cause is.

Now, you might think that his reason for saying this has something to do with attributing our remote origin to evolution rather than divine creation. You might think, in other words, that he is supposing that if God didn’t make us, then we must not have a purpose or final cause. But that is not Barham’s reason -- and it’s a good thing, since that would not be a good reason for saying it. For Aristotelians, at least where true substances are concerned -- water, lead, gold, copper, trees, birds, spiders, human beings, etc. -- you don’t need to know anything about their remote origins in order to know their teleological features or final causes, any more than you need to know their remote origins in order to know their formal or material or (immediate) efficient causes.

For example, you don’t need to know whether God made acorns in order to know that they are “directed at” or “point toward” becoming oaks. You don’t need to know whether God made trees in order to know that their roots are “for” taking in water and nutrients and giving the tree stability. You don’t need to know whether God made spiders in order to know that their webs have the function of allowing them to catch prey. You don’t need to know whether God made copper in order to know that copper has a tendency to conduct electricity. Etc. All you need to do is to observe how birds and spiders tend to act when in their mature and healthy state, what acorns and copper tend to do under various circumstances, etc. The causal powers a thing exhibits are the key to understanding its finality or “directedness.” (Recall that, contrary to the standard caricature, most finality or teleology in nature involves nothing as fancy as biological function. It typically involves just a mere “directedness” or “pointing” toward a certain standard outcome or range of outcomes.)

Barham is aware that for Aristotle, to know a natural object’s teleological features, one needs to observe how it characteristically behaves, and that this is as true of human beings as it is of anything else. He is also aware that for Aristotle, what is characteristic of human beings is that they exhibit rational powers, so that living in accordance with reason is, for Aristotle, our final cause.

So far so good. But now comes Barham’s mistake. He thinks Aristotle’s answer faces the following difficulties. First, Barham thinks that there are alterative candidates for our final cause or natural end that are no less plausible than rationality. His examples are agency, the capacity for morality, and love. Second, he notes that we often act irrationally and suggests that replicants can be no less rational than human beings are -- in which case rationality is neither necessary nor sufficient for being a human being. Third, he seems to think that a problem with any proposed characteristic (rationality, moral behavior, love, or whatever) is that there are instances of human beings who don’t exhibit it -- so that (Barham seems to conclude) none of them can be the final cause of human beings as such. (In fairness to Barham, in some cases it’s not clear whether these are objections Barham himself endorses, or merely objections he thinks are implicit in Blade Runner.)

Longtime readers no doubt know already how I would respond to objections of this sort. (They will also be familiar with the Aristotelian and Scholastic notions to be deployed below -- notions I’ve spelled out and defended in many places, and most systematically in Scholastic Metaphysics .)