Edward Feser's Blog, page 83

April 3, 2015

The two faces of tolerance

What is proclaimed and practiced as tolerance today, is in many of its most effective manifestations serving the cause of oppression.

What is proclaimed and practiced as tolerance today, is in many of its most effective manifestations serving the cause of oppression. Herbert Marcuse

Democracy is the theory that the common people know what they want, and deserve to get it good and hard.

H. L. Mencken

Given current events in Indiana, I suppose it is time once again to recall a post first run on the old Right Reason blog in March of 2007, and reprinted on this blog in December of 2009. Here are the relevant passages, followed by some commentary:To the charge that liberals are (or, given their principles, should be) in favor of X [where X = legalizing abortion, liberalizing obscenity laws, banning smoking on private property, legalizing “same-sex marriage,” outlawing the public advocacy of traditional sexual morality, etc. etc.], the standard liberal response goes through about five stages (with, it seems, roughly 5-10 years passing between each stage, though sometimes the transition is much quicker than that). Here they are:

Stage 1: “Oh please. Only a far-right-wing nutjob would make such a paranoid and ridiculous accusation - I suppose next you’ll accuse us of wanting to poison your precious bodily fluids!”

Stage 2: “Well, I wouldn’t go as far as X. All the same, it’s good to be open-minded about these things. I mean, people used to think ending slavery was a crazy idea too…”

Stage 3: “Hey, the Europeans have had X for years and the sky hasn’t fallen. But no, I admit that this backward country probably isn’t ready for X yet.”

Stage 4: “Of course I’m in favor of X - it’s in the Constitution! Only a far-right-wing nutjob could possibly oppose it.”

Stage 5: “You have the right to remain silent. Anything you say can be used against you in a court of law…”

…

Fortunately, though, we can rely on conservatives to hold the line, and indeed to turn back liberal advances. Right?

Well, no, of course not. (You can stop rolling your eyes, I was being facetious.) For conservatives - or maybe I should say “conservatives” (since there’s very little that they ever actually manage to conserve, unless money is somehow involved) - seem to go through five stages of their own. Here they are:

Stage 1: “Mark my words: if the extreme left had its way, they’d foist X upon us! These nutjobs must be opposed at all costs.”

Stage 2: “Omigosh, now even thoughtful, mainstream liberals favor X! Fortunately, it’s political suicide.”

Stage 3: “X now exists in 45 out of 50 states. Fellow conservatives, we need to learn how to adjust to this grim new reality.”

Stage 4: “X isn’t so bad, really, when you think about it. And you know, sometimes change is good. Consider slavery…”

Stage 5: “Hey, I was always in favor of X! You must have me confused with a [paleocon, theocon, Bible thumper, etc.]. But everyone knows that mainstream conservatism has nothing to do with those nutjobs…”

End quote. Now, where X = curtailing the free exercise of religion, at the time I first wrote those words I estimated that liberals were at about stage 2. At this point it seems that many of them are at about stage 4, and a disturbing number of hotheads among them seem willing to push for stage 5 vigilantism. Conservatives, meanwhile, seem mostly to be at about stage 3 of their own progression, and I suspect that not a few are at least flirting with Stage 4.

And so here is where we find ourselves in the land of the free and the home of the brave in April of 2015:

Prominent conservative politicians and churchmen have all essentially caved in on the substance of the dispute over “same-sex marriage.” None of them will publicly express the slightest moral disapproval of homosexual behavior, and few even bother anymore with social scientific arguments supporting the benefits of children being raised by both a mother and a father. Indeed, all of them are eager to express their deep respect for their fellow citizens who happen to be homosexual, vigorously to condemn “homophobia” and discrimination, etc. Some of them are even happy to affirm “same-sex marriage.” All they ask is that religious believers who on moral grounds disapprove of “same-sex marriage” not be forced to cooperate formally or materially with it. The circumstances where this might occur are, of course, very rare. No one is proposing that business owners might refuse to serve a customer simply because he or she happens to be homosexual. What is in view are merely cases where a business owner who objects to “same-sex marriage” would be forced to participate in it, say by providing a wedding cake or wedding invitations. Nor would his refusal to participate inconvenience anyone, since there are plenty of business owners who have no qualms about “same-sex marriage.”

In short, what conservatives are proposing is not only extremely modest, but is being defended in the name of their opponents’ own principles, the most liberalof principles, viz. the Jeffersonian principle that it is tyrannical to force someone to act against his conscience, and the Rawlsian principle that a pluralistic society should strive as far as possible to respect and keep a just peace between citizens committed to radically different moral, philosophical and religious views.

And for taking this paradigmatically liberal position, they are widely and shrilly denounced by liberals as… “bigots,” “haters,” “intolerant,” comparable to the Ku Klux Klan and the upholders of Jim Crow.

Meanwhile, some liberal business owners fire employees who take this conservative position, while others refuse to do business in a state that adopts it. Other liberals routinely refuse even to discuss the merits of the conservative position but merely hurl insults and try to shout down and intimidate anyone who dares to disagree with them. And when a particular business owner affirms that customers who happen to be homosexual are welcome in her restaurant, but also says that she would not agree to cater a hypothetical “same-sex wedding,” she finds herself suddenly subjected to a nationwide Two Minutes Hate, with an online mob actively seeking to destroy her livelihood and reputation -- some of them even proposing to burn down the restaurant or kill its owners. Even some mainstream liberals, while not condoning such violence, suggest that the restaurant owner had invited this abuse.

And liberals have winked at or even embraced the ethos and tactics of the lynch mob in the name of… tolerance, freedom, and pluralism, of love and compassion and opposition to bigotry.

How have we descended into such Orwellian insanity?

It’s all about sexual equality

Part of it has to do with the fact that what is at issue here concerns sex. And make no mistake, it is sex in general, rather than homosexuality in particular, that is ultimately at issue. Consider that current liberal proposals to curb freedom of conscience where disapproval of “same-sex marriage” is concerned are of a piece with recent liberal proposals to curb freedom of conscience where contraception and abortifacient drugs are concerned. Consider also that only a small percentage of people, including a small percentage of liberals, have a homosexual orientation. But perhaps a majority of people in contemporary Western society, and certainly the overwhelming majority of liberals, have bought into the sexual revolution. In particular, they have bought into the idea that where sex is concerned, the only moral consideration, and certainly the only consideration that should have any influence on public policy, is consent. There can in their view be no moral objection, and perhaps no reasonable objection of any other sort, to sexual arrangements to which all parties have consented. There is in their view a presumption in favor of license, and thus a presumption against anyone who would object to license. The conclusion that there can be no reasonable objection to “same-sex marriage” follows naturally. It is merely one consequence among others of a generally libertine attitude about sex.

Now, here’s the thing about sex. The unique intensity of sexual pleasure, the central role that success in romantic and sexual relationships plays in our sense of fulfillment and self-worth, and the unpleasant feeling of shame that accompanies indulgence in sexual actions we suspect of being in some way wrong, makes it very difficult for people to think clearly or dispassionately about sex. We have a very strong bias in favor of trying to find ways of rationalizing indulgence, and a very strong bias against regarding some sexual behavior toward which we are attracted as wrong or shameful. These biases are only increased by sexual license. The more deeply you buy into the sexual revolution and act accordingly, the more reluctant you are going to be to want to listen to any criticism of it.

This is why Aquinas regards what he calls “blindness of mind,” “self-love,” and “hatred of God” as among the “daughters of lust” -- where by “lust” Aquinas means, not sexual desire, but rather sexual indulgence that is in some way or other disordered. Sexual immorality fosters “blindness of mind” in the sense that the one indulging in it tends to have greater difficulty than he otherwise would in thinking coolly and dispassionately about matters of sex. He tends toward “self-love” in that he is strongly inclined to make his own subjective feelings and desires the measure by which to judge any proposed standards of morality, rather than letting objective moral standards be the measure by which to judge his feelings and desires. He tends toward “hatred of God” insofar as the very idea that there is an objective moral law or lawgiver who might condemn his indulgence becomes abhorrent to him. (I recently discussed Aquinas’s analysis at length here.)

So, when a sexually libertine liberal activist shrieks “Bigot! Bigot! Bigot!” in your face at the top of his lungs as if he were putting forward a rational argument, or tries to destroy a person’s reputation and strip him of his livelihood in the name of compassion, or threatens to kill him or burn down his business in the name of tolerance, the manifest cognitive dissonance should not be surprising. It is only to be expected. Sexual libertinism is destructive of rationality.

It’s all about sexual equality

But it’s not just about sex. It’s about egalitarianism itself, which, as Plato argued in The Republic, is inherently destructive of moral, legal, and rational standards, and has tyranny as its natural sequel. The egalitarian regime insists, notionally, on tolerating every opinion and way of life, and refuses either to judge any one of them as morally or rationally superior to any other, or to favor any of them in its laws. Yet no regime can tolerate what would subvert it. And the very idea that some views and ways of life are simply objectively superior, rationally and morally, to others, is subversive of egalitarianism. Hence egalitarian societies tend in practice to be intolerant of views which maintain that there are objective standards by which some views and ways of life might be judged better or worse. That is to say, an egalitarian regime inevitably tolerates only those views which are egalitarian. Which means, of course, that it tolerates only itself.

Thus, in Plato’s own day, do we have the spectacle of Athens, which was democratic, pluralist, and egalitarian -- and killed Socrates, because it suspected that he was none of the above. Thus do we have the French Revolution, which murdered thousands in the name of liberty, equality, and fraternity. Thus do we have Stalinist Russia and Maoist China, each of which slaughtered tens of millions in the name of equality. If egalitarians have, historically, been able to convince themselves of the justifiability of all that, then burning down a pizzeria is a cinch.

Nor is it by any means only these more extreme forms of egalitarianism that practice intolerance in the name of tolerance. You will find the same tendency in John Locke, that most moderate of early modern liberals. Locke famously argued for religious toleration -- exceptfor Catholics, for atheists, or for anyone who rejects the doctrine of religious toleration. The reason was that Locke regarded the views of all such people as subversive of a tolerant, liberal society -- Catholics because their primary loyalty was to the pope rather than to the liberal state, atheists because they denied the theological foundations that the Protestant Locke thought essential to morality and politics, and deniers of religious liberty for the obvious reason that they rejected the whole idea of the tolerant liberal state. Locke went so far in the direction of insisting that only those religions which accepted his doctrine of toleration ought to be tolerated that he held “tolerationto be the chief characteristical mark of the true church.” In other words, a real religion is one which embraces Lockeanism. Hence the Lockean liberal regime tolerates only those views which accept the basic principles of Lockean liberalism. Which ultimately means, of course, that it too tolerates only itself. (See chapter 5 of my book Locke for further discussion of Locke’s doctrine on toleration.)

Things are in no way different with the contemporary liberalism of John Rawls. Rawls famously holds that a liberal society is one which is neutral between, and can be accepted as just on the basis of premises held by, all of the competing “comprehensive doctrines” -- that is to say, the religious, philosophical and moral worldviews -- that exist within a modern pluralistic society. Or at least, Rawls says, it is neutral between the “reasonable” comprehensive doctrines. And what makes a doctrine “reasonable,” as it turns out, is a willingness to endorse the principles of Rawls’s brand of liberalism. Which means that the Rawlsian regime tolerates only those views which endorse its underlying principles. And thus -- once again -- we have a form of egalitarianism which on analysis really only tolerates itself. (I’ve discussed the bogusness of Rawlsian neutrality elsewhere, e.g. here, here, and here.)

Now, how do you counter sexual libertinism and the totalitarian tendencies of egalitarianism? Naturally, by vigorously arguing for traditional sexual morality, and working for legal safeguards of the liberty of those who affirm traditional sexual morality to live in accordance with it. Easier said than done, needless to say. But there is no alternative, in the short term or, especially, in the long term. Rusty Reno, at First Things, seems to agree. He recommends two courses of action to conservative and religious leaders:

The first is obvious. We need to work for laws like the Indiana RFRA to provide some protection, however modest, to our communities from the coming onslaught of “anti-bigotry” laws.

The second is less obvious but perhaps even more important. We need to stand up and speak clearly about the biblical teaching on sex, marriage, and family. It’s the leaders of the Church who should be attacked in public as “homophobic,” not politicians like Mike Pence who are trying to do the right thing.

Yet some political leaders seem more inclined to cave in to the demands of the mob, and some religious leaders more inclined to hide under the covers and hope the problem goes away. Naturally, this will only embolden the mob. These political and religious leaders are asking for it, and they are going to get it from the “tolerance” crowd -- good and hard, as Mencken would say. Unfortunately, they won’t be the only ones to suffer the effects of their cowardice.

Published on April 03, 2015 16:07

Albertus Magnus Center summer program

The Albertus Magnus Center for Scholastic Studies is sponsoring a two-week summer program in Norcia, Italy, from July 12-25. The theme is Aquinas’s commentary on I Corinthians. Details can be found here.

The Albertus Magnus Center for Scholastic Studies is sponsoring a two-week summer program in Norcia, Italy, from July 12-25. The theme is Aquinas’s commentary on I Corinthians. Details can be found here.

Published on April 03, 2015 16:03

March 31, 2015

Was Aquinas a materialist?

Denys Turner’s recent book

Thomas Aquinas: A Portrait

is beautifully written and consistently thought-provoking. It is also a little mischievous, in a good-natured way. A main theme of the book is what Turner characterizes as Aquinas’s “materialism.” Turner is aware that Aquinas was not a materialist in the modern sense. And as I have emphasized many times (such as at the beginning of the chapter on Aquinas’s philosophical psychology in

Aquinas

), you cannot understand Aquinas’s position unless you understand how badly suited the standard jargon in contemporary philosophy of mind is to describe that position. Turner’s reference to Aquinas’s “materialism” is intended to emphasize the respects in which Aquinas’s position is deeply at odds with what many think of as essential to a “dualist” conception of human nature. And he is right to emphasize that. All the same, as I have argued before, if we are going to use modern terminology to characterize Aquinas’s view -- and in particular, if we want to make it clear where Aquinas stood on the issue that contemporary dualists and materialists themselves think is most crucially at stake in the debate between dualism and materialism -- then “dualist” is a more apt label than “materialist.”When philosophers and theologians whose formation is in classical and medieval thought and who lack much familiarity with contemporary analytic philosophy hear the word “dualism,” they tend automatically to think of Platonism. That is to say, they tend to associate “dualism” with the view that a human being is essentially an immaterial soul, that the body is not only extrinsic to human nature but even a kind of prison from which the soul needs to be liberated, and that the natural orientation of the soul’s cognitive powers is toward the realm of Platonic abstract ideas rather than concrete material reality. Now, Aquinas was definitely nota “dualist” in this sense. As Turner rightly emphasizes, Aquinas regarded animality and thus corporeality as no less a part of our nature than our intellectual powers are, and he took our cognitive faculties to be naturally oriented toward the material world. The body is not a prison but essential to us, so that without his body a human being is radically incomplete.

Denys Turner’s recent book

Thomas Aquinas: A Portrait

is beautifully written and consistently thought-provoking. It is also a little mischievous, in a good-natured way. A main theme of the book is what Turner characterizes as Aquinas’s “materialism.” Turner is aware that Aquinas was not a materialist in the modern sense. And as I have emphasized many times (such as at the beginning of the chapter on Aquinas’s philosophical psychology in

Aquinas

), you cannot understand Aquinas’s position unless you understand how badly suited the standard jargon in contemporary philosophy of mind is to describe that position. Turner’s reference to Aquinas’s “materialism” is intended to emphasize the respects in which Aquinas’s position is deeply at odds with what many think of as essential to a “dualist” conception of human nature. And he is right to emphasize that. All the same, as I have argued before, if we are going to use modern terminology to characterize Aquinas’s view -- and in particular, if we want to make it clear where Aquinas stood on the issue that contemporary dualists and materialists themselves think is most crucially at stake in the debate between dualism and materialism -- then “dualist” is a more apt label than “materialist.”When philosophers and theologians whose formation is in classical and medieval thought and who lack much familiarity with contemporary analytic philosophy hear the word “dualism,” they tend automatically to think of Platonism. That is to say, they tend to associate “dualism” with the view that a human being is essentially an immaterial soul, that the body is not only extrinsic to human nature but even a kind of prison from which the soul needs to be liberated, and that the natural orientation of the soul’s cognitive powers is toward the realm of Platonic abstract ideas rather than concrete material reality. Now, Aquinas was definitely nota “dualist” in this sense. As Turner rightly emphasizes, Aquinas regarded animality and thus corporeality as no less a part of our nature than our intellectual powers are, and he took our cognitive faculties to be naturally oriented toward the material world. The body is not a prison but essential to us, so that without his body a human being is radically incomplete.However, when philosophers whose formation was in contemporary analytic philosophy hear the word “dualism,” what they tend automatically to think of is the view that the human mind is at least partially irreducible to or inexplicable in terms of anything corporeal. And when they hear the word “materialism,” they tend automatically to think of the view that the human mind is entirely reducible to or explicable in terms of the corporeal. So, the assertion that Aquinas was not a “dualist” but was more like a “materialist” is bound to sound, to the typical contemporary academic philosopher, like the claim that Aquinas thought that there is no incorporeal aspect to human nature -- that human beings are, like other animals, entirely corporeal. And that is certainly not what Aquinas thought. He puts forward many arguments purporting to show that the human intellect is incorporeal. So, given current usage, it is misleading to deny that Aquinas was a “dualist,” and extremely misleading to say that he was a “materialist.” He clearly was a kind of dualist, in the modern sense of “dualism,” and clearly was nota materialist, given the sense typically attached to “materialism.”

One reason this is not sufficiently clear from Turner’s discussion is that Turner gives the impression that the main difference between Aquinas and contemporary materialism is that Aquinas, unlike materialists, regarded all matter as conjoined with form. As Turner sums up what he takes to be the key issue, it is because material things have form that they can on Aquinas’s view be “alive with meaning,” whereas matter as the contemporary materialist conceives of it is “meaninglessly dumb” or devoid of any inherent meaning (p. 97). The impression Turner leaves the reader with is that as long as we beef up our conception of a material thing so that it includes the Aristotelian notion of form, then Aquinas’s position can plausibly be called “materialist.”

But that is simply not all there is to the difference between Aquinas and modern materialism, even if it is an important part of the story. To be sure, Aquinas does think that purely corporeal things can possess what Turner calls “meaning” by virtue of having the forms they do. For example, a bird is purely corporeal, and its bodily organs and activities have the “meanings” they do because the matter that makes up the bird has the substantial form of a bird rather than the form of some other thing. For example, the bird has visual experiences which represent objects in its environment, and its wings serve the function of allowing it to fly. Because Aquinas’s notion of matter is Aristotelian (rather than the desiccated notion of matter the modern materialist has inherited from Descartes and Co.) -- in particular, because he affirms immanent formal and final causes -- there is for him nothing mysterious about how a purely material substance could possess features like intentionality and teleology.

But in Aquinas’s view, the “meaning” of which rationalanimals are capable goes well beyond the “directedness” toward an end of which sub-rational animals, merely vegetative forms of life, and indeed even inorganic processes are capable. For rational animals possess mental states with conceptual content. This is what distinguishes intellect from the sensation and imagination of which non-human animals are capable. And in Aquinas’s view (as Turner himself notes), strictly intellectual activity does not have a bodily organ but is essentially incorporeal. That the human soul possesses this incorporeal activity alongside its corporeal activities is the reason why Aquinas thinks that the human soul can (unlike the souls of non-human animals) persist beyond the death of the body, and also why he thinks it cannot have been derived from our parents but must be specially created by God.

So, that he affirms that natural objects are composites of form and matter is by no means the only thing that sets Aquinas apart from modern materialists. That intellectual activity is essentially incorporeal or non-bodily, that the human soul survives the death of the body, and that it must be specially created by God are, needless to say, all theses that the contemporary materialist would also firmly reject. Meanwhile, contemporary dualists would affirm some or all of these theses. So, to say: “Aquinas thought the human soul was incorporeal, survives the death of the body, and must be specially created by God -- but he was a materialist, and not a dualist!”… to say that would, really, be beyondmisleading. To most modern readers, it cannot fail to sound utterly bizarre, indeed incoherent.

Part of the problem here is that Turner, like many others, treats Aquinas’s claim that the soul is the form of the body as if it were terribly mysterious. For how can the soul be the form of the body and yet persist beyond the death of the body? Some deal with this purported mystery by emphasizing the soul’s persistence beyond death, and interpreting Aquinas as if he were, at bottom, “really” a kind of Platonist or Cartesian. Turner, in effect, deals with it by emphasizing the soul’s status as the form of the body, and interprets Aquinas as if he were “really” a kind of materialist.

The error in both cases, I would suggest, is that when Aquinas says that:

(1) The soul is the form of the body

both sorts of readers at least implicitly interpret him as meaning that:

(2) The soul is the form of a substance which is entirely bodily or corporeal.

As a result they are puzzled when Aquinas goes on to say that the soul persists beyond the death of the body. For how, on an Aristotelian account, could the form of a corporeal substance persist when that substance is gone? Hence, they conclude, either Aquinas at bottom really thinks, or if he were consistent ought to think, that the soul is not the form of the body but rather a substance in its own right; or at bottom he really thinks, or if he were consistent ought to think, that the soul is the form of the body and thus that it does not persist beyond the death of the body; or Aquinas really thinks both things and is therefore just not consistent.

But there is no inconsistency, because (1) simply does not entail (2), and Aquinas would reject (2). For in Aquinas’s view, the human soul is the form of a substance, that substance is a human being, and a human being has both corporeal and incorporealoperations. Hence the soul is not the form of a substance which is entirely bodily or corporeal. Rather, it is the form of a substance which is corporeal in some respects and incorporeal in others. Now, those corporeal respects are the ones summed up in the phrase “the body.” Hence the soul is, naturally, the form of the body. But it simply doesn’t follow that the soul is the form of a substance which is exhausted by its body, viz. by its bodily operations.

This is why there is nothing terribly mysterious about why the soul, as Aquinas understands it, can persist beyond the death of the body. For the substance of which the soul is the form does not go out of existence with the death of the body. Rather, the corporeal or bodily operations of that substance cease, while the incorporeal operations continue. To be sure, the substance in question has been severely reduced or damaged; that is why Aquinas thinks of the disembodied soul as an “incomplete substance.” But an incomplete substance is not a non-substance. Thus, to say that the soul persists beyond the death of the body is not to say that the form of a substance persists after the substance has gone out of existence (which certainly would be a very mysterious thing for an Aristotelian like Aquinas to say!)

That a human being is this unique, indeed very weird sort of substance -- corporeal in some respects and incorporeal in others -- is what makes us different from, on the one hand, non-human animals (which are entirely corporeal) and on the other hand, angels (which are entirely incorporeal). Platonists and Cartesians essentially assimilate human beings to angels, whereas materialists essentially assimilate human beings to non-human animals. Aquinas rejects both views. All the same, since to be a “dualist,” as that term is typically used today, it suffices to affirm that human beings have both corporeal and incorporeal features, there is obviously a clear sense in which Aquinas is a dualist. And since affirming that human beings have incorporeal features -- not to mention affirming that there are purely incorporeal substances, viz. angels -- would suffice to keep one from being a “materialist” on pretty much any construal of “materialism,” it seems no less clear that Aquinas was not a materialist.

So, it seems to me that Turner’s use of the term, though understandable in light of those aspects of Aquinas’s position he rightly wants to emphasize, is ill-advised. All the same, you cannot fail to learn from Turner’s book even when you disagree with him.

(For more on Aquinas’s philosophical psychology, see, among the many posts on the mind-body problem collected here, those devoted to the subject of Thomistic or hylemorphic dualism.)

Published on March 31, 2015 18:40

March 25, 2015

Web of intrigue

Analytical Thomist John Haldane has been appointedto the J. Newton Rayzor Sr. Distinguished Chair in Philosophy at Baylor University.

Analytical Thomist John Haldane has been appointedto the J. Newton Rayzor Sr. Distinguished Chair in Philosophy at Baylor University. At The Times Literary Supplement, Galen Strawson arguesthat it is matter, not consciousness, that is truly mysterious.

At Aeon magazine, philosopher Quassim Cassam investigates the intellectual character of those drawn toward conspiracy theories.

At Public Discourse, William Carroll defendsthe reality of the soul against Julien Mussolino, author of The Soul Fallacy.

Fr. C. John McCloskey puts forward a traditional defense of capital punishment at The Catholic Thing.

The “iThink”: Philosopher Charlie Huenemann on how to understand, and teach, the nature of Descartes’ philosophical revolution.

A new paper from James Franklin: “Uninstantiated Properties and Semi-Platonist Aristotelianism,” from the Review of Metaphysics.

Augustine's Confessions: Philosophy in Autobiography , a new anthology edited by William E. Mann, is reviewed at Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews. Also reviewedis another anthology, edited by Tad Schmaltz: Efficient Causation: A History .

Tuomas Tahko announces a new volume on the theme Aristotelian Metaphysics: Essence and Ground.

The University Bookman reviews two books arguing for the rehabilitation of the reputation of General Douglas MacArthur.

At Public Discourse, “new natural lawyers” John Finnis and Robert P. George reply to Gary Gutting’s recent criticisms of the natural law approach to sexual morality.

Aquinas and the Nicomachean Ethics , edited by Tobias Hoffmann, Jörn Müller, and Matthias Perkams is reviewed in the Claremont Review of Books.

Published on March 25, 2015 18:41

March 20, 2015

Pigliucci on metaphysics

At Scientia Salon, philosopher Massimo Pigliucci admits to “always having had a troubled relationship with metaphysics.” He summarizes the reasons that have, over the course of his career, made it difficult for him to take the subject seriously. Surprisingly -- given that Pigliucci is, his eschewal of metaphysics notwithstanding, a professional philosopher -- none of these reasons is any good. Or rather, this is not surprising at all, since there simply are no good reasons for dismissing metaphysics -- and could not be, given that all purported reasons for doing so themselves invariably embody unexamined metaphysical assumptions. Thus, as Gilson famously observed, does metaphysics always bury its undertakers.Pigliucci’s misgivings began, he tells us, when he first encountered the medieval Scholastics while in high school in Italy. Though he admits that “medieval logicians actually did excellent work,” he says that “as a teenager prone to (intellectual) rebelliousness… I couldn’t but reject the Scholastics.” He adds that “the Scholastics still have a bad reputation in philosophical circles.” Now of course, neither adolescent rebelliousness nor appeal to contemporary intellectual fashion constitutes a serious argument. So, does Pigliucci actually have any substantive grounds for rejecting Scholasticmetaphysics, specifically? He doesn’t tell us. Does Pigliucci even understand Scholastic metaphysics? For example, does he understand how it differs (profoundly!) from the kind of metaphysics one finds in rationalist philosophers like Leibniz and in the work of most contemporary metaphysicians? From other things he says in his post, it seems not.

At Scientia Salon, philosopher Massimo Pigliucci admits to “always having had a troubled relationship with metaphysics.” He summarizes the reasons that have, over the course of his career, made it difficult for him to take the subject seriously. Surprisingly -- given that Pigliucci is, his eschewal of metaphysics notwithstanding, a professional philosopher -- none of these reasons is any good. Or rather, this is not surprising at all, since there simply are no good reasons for dismissing metaphysics -- and could not be, given that all purported reasons for doing so themselves invariably embody unexamined metaphysical assumptions. Thus, as Gilson famously observed, does metaphysics always bury its undertakers.Pigliucci’s misgivings began, he tells us, when he first encountered the medieval Scholastics while in high school in Italy. Though he admits that “medieval logicians actually did excellent work,” he says that “as a teenager prone to (intellectual) rebelliousness… I couldn’t but reject the Scholastics.” He adds that “the Scholastics still have a bad reputation in philosophical circles.” Now of course, neither adolescent rebelliousness nor appeal to contemporary intellectual fashion constitutes a serious argument. So, does Pigliucci actually have any substantive grounds for rejecting Scholasticmetaphysics, specifically? He doesn’t tell us. Does Pigliucci even understand Scholastic metaphysics? For example, does he understand how it differs (profoundly!) from the kind of metaphysics one finds in rationalist philosophers like Leibniz and in the work of most contemporary metaphysicians? From other things he says in his post, it seems not. We’ll come back to that. First, consider the other factors which, Pigliucci tells us, deepened his suspicion of metaphysics. While in college, he says, he was impressed by the logical positivists’ famous verification principle, and their application of it to a critique of metaphysics. The basic idea, as is well known, is that any meaningful statement must (the verification principle claims) be either analytically true (like “All bachelors are unmarried”) or empirically verifiable. Yet metaphysical statements are (the argument continues) neither. Therefore they are strictly meaningless, not even rising to the level of falsehood.

There are various problems with the verification principle, the most notorious being that it is self-refuting, insofar as the principle itself is neither analytically true nor empirically verifiable. It is thus no less “meaningless” and indeed “metaphysical” (as verificationists conceived of metaphysics) as the claims it was deployed against. Alternative formulations of the principle have been attempted, but the trouble is that there is no way to formulate the principle in such a way that it both avoids self-refutation and still has the anti-metaphysical bite the positivists thought it had. These are such well-known points that it is unlikely that Pigliucci still regards verificationism as a serious challenge to metaphysics. So, even if it impressed Pigliucci as a student, what does that have to do with why he is still suspicious of metaphysics now, as a professional philosopher?

The third influence on his suspicions, he says, was “Hume’s Fork” -- David Hume’s famous doctrine that any proposition that concerns neither “relations of ideas” nor “matters of fact” can contain only “sophistry and illusion” and might as well be “commit[ed] to the flames.” Naturally, the suspect propositions included, in Hume’s view, those of traditional metaphysics, and Pigliucci tells us that on first encountering it he found Hume’s position “a neat and no nonsense kind of view.” The trouble, though, is that Hume’s Fork is an anticipation of the positivists’ verification principle, and has similar problems. In particular, it appears to be no less self-refuting, for Hume’s Fork is not itself either true by virtue of the relations of the ideas that enter into its formulation, or true by virtue of empirically discernible matters of fact. Hence it is no less “metaphysical” than the propositions it was used to criticize. And as with the verification principle, while one can attempt to reformulate Hume’s Fork in such a way as to keep it from being self-undermining, doing so also strips it of its anti-metaphysical bite. And again, Pigliucci presumably realizes this, since it is well-known.

So far, then, if Pigliucci intends to give us serious rational grounds for being suspicious of metaphysics, he’s 0 for 3. But he cites a fourth influence on his skepticism: James Ladyman and Don Ross’s book Every Thing Must Go , which, while it advocates a “scientific” or “naturalized” metaphysics, is hostile to traditional metaphysics. On what grounds? In Ladyman and Ross’s view, the trouble with any metaphysics that isn’t essentially just the book-keeping department for empirical science is that it is going to amount to mere “conceptual analysis.” And “conceptual analysis” is grounded in ordinary language, commonsense intuitions, and “folk” notions -- all of which often conflict with the picture of the world science gives us. The concepts the metaphysician analyzes and the intuitions to which he appeals thus may well float free of objective reality. Hence any metaphysics that isn’t essentially just the systematization of what the various sciences have to tell us lacks (so the argument goes) any solid foundation.

This might seem to be a more formidable challenge to metaphysics than either the Humean or the verificationist challenge. After all, Ladyman and Ross do not eschew metaphysics entirely, since they allow that metaphysics is respectable if suitably “naturalized” or made “scientific.” And many contemporary metaphysicians do indeed ground their arguments in “conceptual analysis,” “intuitions,” and the like. Hence, Ladyman and Ross might seem more sober than the likes of Hume, A. J. Ayer, and Co., neither directing their attacks at a straw man nor advocating an unreasonably extreme alternative position.

In fact, though, the Ladyman/Ross position is not only not a better argument than the Humean and verificationist arguments, it is on closer inspection really just the same argument superficially repackaged. For Hume’s “matters of fact” and the positivists’ “empirically verifiable propositions,” read “naturalized (or scientific) metaphysics.” And for Hume’s “relations of ideas” and the positivists’ “analytic statements,” read “conceptual analysis.” Hence the Ladyman/Ross thesis that if a proposition isn’t a claim of natural science/”naturalized” metaphysics, then the only other thing for it to be is “conceptual analysis,” is essentially just a riff on Hume’s Fork. And it has the same problem. For the Ladyman/Ross thesis is not itself either a claim of natural science/”naturalized” metaphysics, or knowable via “conceptual analysis.”

Of course, some “naturalized metaphysicians” might suggest that neuroscience or cognitive science supports the Ladyman/Ross thesis, but if so they are deluding themselves. For the actual empirical results of neuroscience or cognitive science would support the thesis only if interpreted in light of a naturalistic metaphysics, but not if interpreted in light of (say) an Aristotelian metaphysics, or an idealist metaphysics, or a panpsychist metaphysics, or a Cartesian metaphysics, or a Whiteheadian process metaphysics, etc. Hence any attempt to appeal to the results of neuroscience or cognitive science naturalistically interpreted, in order to support the Ladyman/Ross thesis, would be question-begging.

So, the fourth influence on Pigliucci’s skepticism about metaphysics really gives him no better a reason for his skepticism than the first three do. Nor is the self-refutation problem the only problem with the critiques of traditional metaphysics in question. Another problem is that the verificationist, Humean, and Ladyman/Ross objections all presuppose too narrow and parochial a conception of metaphysics. In particular, they tend unreflectively to frame the issues within a rationalist/empiricist/Kantian dialectic inherited from the early moderns. But the Aristotelian-Scholastic tradition -- against which these early modern positions reacted and defined themselves -- rejects the basic assumptions underlying them.

Like the rationalists, Aristotelian-Scholastic philosophers hold that there are metaphysically necessary truths which can be known with certainty, but they reject the rationalist view that such truths are innate or that metaphysics is an essentially a prioridiscipline. Like the empiricists, Aristotelian-Scholastic philosophers hold that our concepts and knowledge derive from experience, but they also reject both the empiricists’ desiccated conception of “experience” and the empiricist tendency to conflate the intellect and the imagination. They regard the intellect as capable of “pulling out” from experience far more than either the rationalist or the empiricist supposes. Hence they reject the assumption that if a proposition isn’t empirical in the thin empiricist (as opposed to thick Aristotelian) sense of “empirical,” then it must be a matter of “conceptual analysis,” with the only remaining question being whether “conceptual analysis” is to be understood in rationalist, Humean, Kantian, Wittgensteinian, Strawsonian, or Frank Jackson-style terms.

Thus, when Ladyman and Ross -- with, it seems, Pigliucci’s approbation -- describe contemporary “conceptual analysis” and “intuition”-based metaphysics as “neo-Scholastic,” they demonstrate thereby only their own utter ignorance of (or, worse, perhaps indifference to) what Scholastics themselves actually believe. For from an Aristotelian-Scholastic point of view, contemporary “conceptual analysis” and “intuition”-based metaphysics is essentially an anemic successor to early modern rationalist metaphysics -- a metaphysics which Scholastics would reject, and which defined itself in opposition to the Aristotelian-Scholastic tradition.

As an example of the sort of thing he regards with suspicion, Pigliucci cites the contemporary metaphysician’s appeal to “conceivability,” as in arguments to the effect that “if it is conceivable, say, that there could be a being that is made exactly like me, atom per atom, and who however doesn’t experience any phenomenal consciousness, then this is sufficient to show a lacuna in physicalism.” Writes Pigliucci: “I reject the very idea that conceivability is a reliable guide to metaphysics at all.”

The example is ironic in two respects. First, Aristotelian-Scholastic metaphysicians would agree that conceivability doesn’t have the significance for metaphysical inquiry that many contemporary analytic metaphysicians suppose it to have. But second, it is quite comical for someone who thinks Hume a paradigm of “no nonsense” anti-metaphysical thinking to cite the appeal to conceivability, of all things, as an Exhibit A piece of metaphysical sleight of hand. For the principle that “whatever we conceive is possible, at least in a metaphysical sense,” is, as is extremely well known, a key component of Hume’s own method. (The quote is from the Abstract of Hume’s Treatise of Human Nature.) For example, this conceivability principle is central to Hume’s critique of the principle of causality, a key thesis of traditional metaphysics. To reject the conceivability principle is thus to reject precisely one of Hume’s key weapons against Scholastics and rationalists alike.

But it’s worse even than that. Hume conflates intellect and imagination, so that to “conceive” something is, for him, essentially to form a mental image of it. This “imagist” account of concepts has been widely regarded as a philosophical howler at least since Wittgenstein (though any Scholastic or rationalist could have told you what is wrong with it). The Humean thesis that we can read off sweeping metaphysical conclusions from the mental images we form is a thesis far more preposterous than any of those held up by Pigliucci for ridicule.

A further irony: Pigliucci (no surprise) makes some dismissive remarks about theology, a subject about which he seems to know as much as he knows about Scholastic metaphysics, viz. not much at all. In particular, he evidently knows nothing about the crucial role played historically by the theological voluntarism of Ockham and Nicholas of Autrecourt, the occasionalism of Malebranche, and the Cartesian and Newtonian replacement of substantial forms and causal powers with “laws of nature” understood as divine decrees, in setting the stage for the Humean conception of natural objects and events as “loose and separate.” Understood in light of its historical background, Hume’s philosophy can be seen to owe largely to bad theology.

In fact, when Hume’s various philosophical errors are exposed -- the assumptions inherited from bad theology, the conflation of intellect and imagination, the self-undermining character of Hume’s Fork, and so forth -- little is left in the way of actual argumentation to support the anti-metaphysical and anti-theological conclusions for which he is famous. His bloated reputation notwithstanding, Hume is exactly what Anscombe said he is: a “mere -- brilliant -- sophist.”

Why that reputation is as bloated as it is, everyone knows: Skeptics simply like Hume’s conclusions, and don’t care to investigate too carefully how plausible, at the end of the day, are the arguments by which he arrived at them. F. H. Bradley, though a metaphysician himself, famously characterized metaphysics as “the finding of bad reasons for what we believe on instinct.” Never was it more obvious than in the case of Hume and his fans how true this can be of opponentsof metaphysics.

As it needn’t be said, a lot more could be said. Since I say a lot more in Scholastic Metaphysics -- about the difference between Scholastic metaphysics and what passes for metaphysics in much contemporary philosophy, about scientism, about Hume’s foibles and intellectual forebears, about laws of nature and much else -- I direct the interested reader to that.

Published on March 20, 2015 11:31

March 13, 2015

Reasons of the Hart

A couple of years ago, theologian David Bentley Hart generated a bit of controversy with some remarks about natural law theory in an article in First Things. I and some other natural law theorists responded, Hart responded to our responses, others rallied to his defense, the natural law theorists issued rejoinders, and before you knew it the Internet -- or, to be a little more precise, this blog -- was awash in lame puns and bad Photoshop. (My own contributions to the fun can be found here, here, here, and here.) In the March 2015 issue of First Things, Hart revisits that debate, or rather uses it as an occasion to make some general remarks about the relationship between faith and reason.The natural law debate revisited

A couple of years ago, theologian David Bentley Hart generated a bit of controversy with some remarks about natural law theory in an article in First Things. I and some other natural law theorists responded, Hart responded to our responses, others rallied to his defense, the natural law theorists issued rejoinders, and before you knew it the Internet -- or, to be a little more precise, this blog -- was awash in lame puns and bad Photoshop. (My own contributions to the fun can be found here, here, here, and here.) In the March 2015 issue of First Things, Hart revisits that debate, or rather uses it as an occasion to make some general remarks about the relationship between faith and reason.The natural law debate revisitedI cannot help but comment briefly on Hart’s summary of his side of the debate of two years ago. He writes:

I took my general point to be not that natural-law theory is inherently futile, but rather that its proponents often fail to grasp just how nihilistic the late modern view of reality has become, or how far our culture has gone toward losing any coherent sense of “nature” at all, let alone of any realm of moral meanings to which nature might afford access. In our time, any argument from immanent goods to transcendent ends must be prepared for by an attempt to “recover the world,” so to speak: a deeper, wider tuition of sensibility, imagination, and natural reverence.

Well, I for one know full well that that is what Hart was saying. And as I pointed out many times two years ago, the problem with Hart’s criticism -- now, as it was then -- is that it rests on a fatal ambiguity. Is Hart’s target the “new natural law” theory of people like Germain Grisez, John Finnis, Robert P. George, and Chris Tollefsen? Or the “old natural law” theory of people like Ralph McInerny, Russell Hittinger, David Oderberg, and me? Hart’s criticism might seem to have force to someone who doesn’t know the difference between these two views. But once one disambiguates them, Hart’s criticism collapses entirely.

The problem is this. Hart’s point is that natural law theory, even if correct, rests on a classical (Platonic, Aristotelian, Scholastic) metaphysical conception of “nature” that is simply rejected, and indeed not even understood, by most of its modern critics. Hence there is little point in arguing for moral conclusions on the basis of that conception of nature until one has first done the hard work of showing, to a modern audience, that that conception of nature is still plausible. But this objection is aimed at a straw man. All natural law theorists are very well aware that the classical conception of nature is a tough sell for most contemporary readers. They deal with this problem in one of two broad ways.

The approach of the “new natural law” theory is to eschew any appeal to the traditional classical metaphysical conception of nature, and to ground its approach instead on an account of practical reason which, it is argued, should be intelligible and acceptable even to someone who does not accept the classical conception. (This is why the “new natural law” theory is new.) The approach of “old natural law” theorists, by contrast, is to reaffirm that natural law theory must be grounded in a classical metaphysical conception of nature (which is why the “old natural law” theory is old). But they recognize that, precisely because they are committed to this older conception, they have a lot of work to do in order to show that that conception is as defensible today as it was in Aquinas’s day. That’s one reason they write books like this one and this one.

What you don’t ever see is any natural law theorist who both (a) grounds his position in a classical metaphysical conception of nature while (b) blithely assuming that that conception is any less controversial today than the natural law conclusions he derives from it are. Certainly Hart has never been able to identify any specific natural law theorist, “new” or “old” -- not one-- who does this. Exactly who is actually guilty of the charge Hart raises against what he refers to as “most natural-law theory in today’s world”? Exactly who actually evinceswhat Hart calls “a boundless confidence in reason’s competency to extract moral truths from nature’s evident forms, no matter what the prevailing cultural regime”? Hart has persistently refused to tell us, persistently refused to explain whether he has “new” or “old” natural law theorists in mind, persistently refused to answer the objection that his charge rests entirely on the ambiguity in question. Hart laments that the controversy of two years ago indicates that it is “perilous to express doubts” regarding the persuasiveness of contemporary natural law theory. But he could have avoided peril had he simply refrained from attacking a straw man. Just sayin’.

Fides et ratio

Anyway, the focus of Hart’s latest piece is the question of the relationship between faith and reason. Hart objects to the charge that he is a fideist, arguing that both fideism and rationalism of the seventeenth-century sort are errors that would have been rejected by the mainstream of the ancient and medieval traditions with which he sympathizes. With that much I agree. I agree too with his claim that the use of reason rests on the “metaphysical presupposition” that there is a natural fit between the intellect and that which the intellect grasps -- an “orientation of truth to the mind and of the mind to truth.” I agree with him when he argues that naturalism cannot account for this fit, that the best it can attribute to our rational faculties is survival value but not capacity to grasp truth, and that this makes it impossible for the naturalist rationally to justify his own position. And I agree with him when he argues that idealism in its various forms also cannot account for this fit -- that if naturalism emphasizes mind-independent truth to such an extent that it cannot account for the mind itself, idealism emphasizes mind to such an extent that it cannot account for mind-independent truth.

All well and good, and indeed a set of points whose importance cannot be overemphasized. What puzzles me, though, is the way Hart characterizes the position he would put in place of these errors -- a way that at least lends itself to a fideist reading, his rejection of the “fideist” label notwithstanding. In particular, he says that the metaphysical presupposition that there is a natural fit between the intellect and that which the intellect grasps is a matter of “trust,” that “there is a fiduciary moment within every act of reason,” and -- most significantly -- that “reason arises from an irreducibly fiduciary movement of the will” (emphasis added).

Now, what exactly is an “irreducibly fiduciary movement of the will”? That certainly sounds a helluva lot like a Jamesian “will to believe” that there is a natural fit between intellect and mind-independent reality, an act of will that is not itself susceptible of rational justification. For if it is susceptible of rational justification, why talk of “will” rather than intellect, and why call the “movement” of the will “irreduciblyfiduciary”? And if we must simply will to trust that there is this fit between mind and world without having a rational justification for doing so, why does this not count as a kind of fideism?

Then there is Hart’s characterization of the rationalism he rejects as holding that reason is “capable of discerning first principles and deducing final conclusions without any surd of the irrational left over” (emphasis added). So, is Hart saying that, in any attempt rationally to justify a position, there always is some “surd of the irrational left over”? Again, why wouldn’t this count as fideism?

On the other hand, the objections Hart rightly raises against naturalism and idealism themselves constitute rational grounds for maintaining that there is a natural fit between the intellect and mind-independent reality, a mutual orientation of the one to the other. For Darwinian naturalism, as Hart points out, gives us a view of the mind on which it floats entirely free of truth. Any belief or argument whatsoever could seem absolutely indubitable even if it were completely wrong, ifthis were conducive to survival. Idealism, meanwhile, tends toward the opposite extreme of tying truth so closely to the mind that it effectively collapses the former into the latter. What is true ends up being whatever the mind takes to be true, so that we save the mind’s capacity to know truth only by making truth trivial. As Hart indicates, it is no accident that in the history of continental thought the sequel to idealism was postmodernism, on which truth is entirely mind-relative.

Now, both of these extreme positions are incoherent. They are both defended by their proponents with arguments, yet each view undermines any argument that could be given for it. We cannot make sense of the practice of formulating and rationally justifying propositions unless we presuppose both that there is a distinction between the intellect and the truths which the intellect grasps, and also that the intellect is naturally “directed” or oriented toward the grasp of these truths. But so to argue just is to give a rational justification of these presuppositions; reductio ad absurdum is, after all, a standard argumentative strategy. In that case, though, the presuppositions do not rest on an “irreducibly fiduciary movement of the will” with a “surd of the irrational left over.” And Hart does indeed condemn postmodernism precisely for making of reason “the purest irrationality, a game of the will.”

So Hart’s position seems ambiguous. On the one hand, there is the emphasis on an “irreducibly fiduciary movement of the will,” skepticism about the rationalist attempt to eliminate “any surd of the irrational,” and talk of “reason’s faith.” On the other hand, there is the rejection of the “fideist” label and criticism of views which entail “irrationality, a game of the will.” So which is it?

One way to read Hart here is that he tends to sympathize more with the “voluntarist” (Scotus, Ockham) rather than “intellectualist” (Aquinas, Neo-Scholastic) strain in Christian thought, but still wants to resist the fideist and irrationalist tendencies of voluntarism. Another way to read him is that his view is at bottom an “intellectualist” one, but that he has merely expressed himself badly. I suspect that the former interpretation is the correct one. And I have, in recent posts (here, here, and here), given some of the reasons why intellectualism and “rationalism” of a sort (albeit not of a Cartesian or Leibnizian sort) are to be preferred to voluntarism.

Published on March 13, 2015 14:11

March 12, 2015

Anscombe Society event

On April 11, I’ll be giving the Princeton Anscombe Society 10th Anniversary Lecture, on the subject “Natural Law and the Foundations of Sexual Ethics.” Prof. Robert George will be the moderator. Details here.

On April 11, I’ll be giving the Princeton Anscombe Society 10th Anniversary Lecture, on the subject “Natural Law and the Foundations of Sexual Ethics.” Prof. Robert George will be the moderator. Details here.

Published on March 12, 2015 18:32

March 7, 2015

Capital punishment should not end (UPDATED)

Four prominent Catholic publications from across the theological spectrum -- Americamagazine, the National Catholic Register, the National Catholic Reporter and Our Sunday Visitor -- this week issued a joint statement declaring that “capital punishment must end.” One might suppose from the statement that all faithful Catholics agree. But that is not the case. As then-Cardinal Ratzinger famously affirmed in 2004, a Catholic may be “at odds with the Holy Father” on the subject of capital punishment and “there may be a legitimate diversity of opinion even among Catholics about… applying the death penalty.” Catholic theologian Steven A. Long has issued a vigorous response to the joint statement at the blog Thomistica.net. (See also Steve’s recent response to an essay by “new natural law” theorist and capital punishment opponent Christopher Tollefsen on whether God ever intends a human being’s death.)

Four prominent Catholic publications from across the theological spectrum -- Americamagazine, the National Catholic Register, the National Catholic Reporter and Our Sunday Visitor -- this week issued a joint statement declaring that “capital punishment must end.” One might suppose from the statement that all faithful Catholics agree. But that is not the case. As then-Cardinal Ratzinger famously affirmed in 2004, a Catholic may be “at odds with the Holy Father” on the subject of capital punishment and “there may be a legitimate diversity of opinion even among Catholics about… applying the death penalty.” Catholic theologian Steven A. Long has issued a vigorous response to the joint statement at the blog Thomistica.net. (See also Steve’s recent response to an essay by “new natural law” theorist and capital punishment opponent Christopher Tollefsen on whether God ever intends a human being’s death.) Apart from registering my own profound disagreement with the joint statement, I will for the moment refrain from commenting on the issue, because I will before long be commenting on it at length. My friend Joseph Bessette is a professor of government at Claremont McKenna College. Joe and I have for some time been working together on a book on Catholicism and capital punishment, and we will complete it soon. It will be, to our knowledge, the most detailed and systematic philosophical, theological, and social scientific defense of capital punishment yet written from a Catholic perspective, and it will provide a thorough critique of the standard Catholic arguments against capital punishment.More on that before long. In the meantime, interested readers are directed to my previous writings on capital punishment. In 2005, at the old Right Reason group blog, I engaged in an exchange with Tollefsen on the subject of capital punishment, natural law, and Catholicism. My contribution to the exchange can be found here:

Catholicism, conservatism, and capital punishment

In a 2011 post I commented on the failure of some churchmen to present the entirety of Catholic teaching on the subject of capital punishment, and their resulting tendency to convey thereby the false impression that the Church’s attitude on this issue is “liberal”:

Deadly unserious

In 2011 I also engaged in a longer exchange with Tollefsen on the subject of capital punishment, both at Public Discourseand here at the blog. My side of the debate can be found at the following links:

In Defense of Capital Punishment

On rehabilitation and execution

Punishment, Proportionality, and the Death Penalty: A Reply to Chris Tollefsen

Tollefsen channels Rawls

Finally, in a 2012 post I addressed some common confusions about retributive justice and its relationship to revenge:

Justice or revenge?

Joe Bessette is also currently completing his own, separate book on capital punishment: Murder Most Foul: a Study and Defense of the Death Penalty in the United States. Some of his previous writings on capital punishment and criminal justice more generally are linked here:

Why the Death Penalty is Fair (with Walter Berns)

Shameless Injustice

In Pursuit of Criminal Justice

UPDATE 3/10: Canon lawyer Edward Peters, Carl Olson at Catholic World Report, and Matt Briggs have now also responded to the joint statement.

Published on March 07, 2015 15:08

Capital punishment should not end

Four prominent Catholic publications from across the theological spectrum -- Americamagazine, the National Catholic Register, the National Catholic Reporter and Our Sunday Visitor -- this week issued a joint statement declaring that “capital punishment must end.” One might suppose from the statement that all faithful Catholics agree. But that is not the case. As then-Cardinal Ratzinger famously affirmed in 2004, a Catholic may be “at odds with the Holy Father” on the subject of capital punishment and “there may be a legitimate diversity of opinion even among Catholics about… applying the death penalty.” Catholic theologian Steven A. Long has issued a vigorous response to the joint statement at the blog Thomistica.net. (See also Steve’s recent response to an essay by “new natural law” theorist and capital punishment opponent Christopher Tollefsen on whether God ever intends a human being’s death.)

Four prominent Catholic publications from across the theological spectrum -- Americamagazine, the National Catholic Register, the National Catholic Reporter and Our Sunday Visitor -- this week issued a joint statement declaring that “capital punishment must end.” One might suppose from the statement that all faithful Catholics agree. But that is not the case. As then-Cardinal Ratzinger famously affirmed in 2004, a Catholic may be “at odds with the Holy Father” on the subject of capital punishment and “there may be a legitimate diversity of opinion even among Catholics about… applying the death penalty.” Catholic theologian Steven A. Long has issued a vigorous response to the joint statement at the blog Thomistica.net. (See also Steve’s recent response to an essay by “new natural law” theorist and capital punishment opponent Christopher Tollefsen on whether God ever intends a human being’s death.) Apart from registering my own profound disagreement with the joint statement, I will for the moment refrain from commenting on the issue, because I will before long be commenting on it at length. My friend Joseph Bessette is a professor of government at Claremont McKenna College. Joe and I have for some time been working together on a book on Catholicism and capital punishment, and we will complete it soon. It will be, to our knowledge, the most detailed and systematic philosophical, theological, and social scientific defense of capital punishment yet written from a Catholic perspective, and it will provide a thorough critique of the standard Catholic arguments against capital punishment.More on that before long. In the meantime, interested readers are directed to my previous writings on capital punishment. In 2005, at the old Right Reason group blog, I engaged in an exchange with Tollefsen on the subject of capital punishment, natural law, and Catholicism. My contribution to the exchange can be found here:

Catholicism, conservatism, and capital punishment

In a 2011 post I commented on the failure of some churchmen to present the entirety of Catholic teaching on the subject of capital punishment, and their resulting tendency to convey thereby the false impression that the Church’s attitude on this issue is “liberal”:

Deadly unserious

In 2011 I also engaged in a longer exchange with Tollefsen on the subject of capital punishment, both at Public Discourseand here at the blog. My side of the debate can be found at the following links:

In Defense of Capital Punishment

On rehabilitation and execution

Punishment, Proportionality, and the Death Penalty: A Reply to Chris Tollefsen

Tollefsen channels Rawls

Finally, in a 2012 post I addressed some common confusions about retributive justice and its relationship to revenge:

Justice or revenge?

Joe Bessette is also currently completing his own, separate book on capital punishment: Murder Most Foul: a Study and Defense of the Death Penalty in the United States. Some of his previous writings on capital punishment and criminal justice more generally are linked here:

Why the Death Penalty is Fair (with Walter Berns)

Shameless Injustice

In Pursuit of Criminal Justice

Published on March 07, 2015 15:08

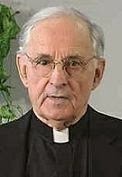

William Wallace, OP (1918-2015)

Fr. William A. Wallace has died. Wallace was a major figure in Aristotelian-Thomistic philosophy of nature and philosophy of science, and the author of many important books and academic articles. Still in print are his books

The Modeling of Nature: Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Nature in Synthesis

(a review of which can be found here), and

The Elements of Philosophy: A Compendium for Philosophers and Theologians

. Among his many other works are his two-volume historical study Causality and Scientific Explanation, the classic paper “Newtonian Antinomies Against the Prima Via” which appeared in The Thomist in 1956 (and is, unfortunately, difficult to get hold of if you don’t have access to a good academic library), and a collection of some of his essays titled From a Realist Point of View. An interview with Wallace can be found here, and curriculum vitae here. Here is the text of a series of lectures by Wallace on philosophy of nature, and here is a YouTube lecture. Some of Wallace’s articles are among those linked to here. RIP.

Fr. William A. Wallace has died. Wallace was a major figure in Aristotelian-Thomistic philosophy of nature and philosophy of science, and the author of many important books and academic articles. Still in print are his books

The Modeling of Nature: Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Nature in Synthesis

(a review of which can be found here), and

The Elements of Philosophy: A Compendium for Philosophers and Theologians

. Among his many other works are his two-volume historical study Causality and Scientific Explanation, the classic paper “Newtonian Antinomies Against the Prima Via” which appeared in The Thomist in 1956 (and is, unfortunately, difficult to get hold of if you don’t have access to a good academic library), and a collection of some of his essays titled From a Realist Point of View. An interview with Wallace can be found here, and curriculum vitae here. Here is the text of a series of lectures by Wallace on philosophy of nature, and here is a YouTube lecture. Some of Wallace’s articles are among those linked to here. RIP.

Published on March 07, 2015 09:49

Edward Feser's Blog

- Edward Feser's profile

- 329 followers

Edward Feser isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.