Martin Fone's Blog, page 89

April 20, 2023

Vending Machine Of The Week (2)

In 1867 Simeon Denham was awarded a British patent (no 706) for creating the first fully-automatic vending machine. It dispensed stamps. The range of goods that are now available from vending machines is gradually increasing. In 2019 I reported on German sausage vending machines and recently Penguin have announced the reintroduction of book vending machines, starting at Exeter station.

In November 2022 a vending machine with a difference was installed at Tazawako Station in Semboku, Japan, offering bear meat. The machine dispenses meat from wild bears “locally captured” in the mountains, thanks to the efforts of a local hunting club, and then processed in an abattoir. To secure a chunk weighing 250 grammes will cost 2,200 yen, about £13, and is proving popular with travellers alighting at the station, selling between ten and fifteen packs a week. Supplies often run out as the restaurant behind the idea, Soba Goro, struggles to meat demand.

Bear meat consumption is highest in northern Japan, where it is sold in cans and even as instant curry. It has a slightly gamey flavour that some have likened to venison, and is often served in stew. “Bear meat tastes clean, and it doesn’t get tough,” a Soba Goro spokesperson said.

Think I will give that one a miss.

April 19, 2023

The Man With The Dark Beard

A review of The Man with the Dark Beard by Annie Haynes – 20230330

Annie Haynes is a Golden Age detective fiction writer I have not come across before and, if the excellent introduction to this edition is to be believed, very few had until Dean Street Press decided to reissue her work in 2015. The Man with the Dark Beard was published a year before her death and introduced Inspector Stoddart to her reading public. There are four books in the series, two published posthumously, the last completed by an unknown fellow writer. It is hard to believe in this snap-happy era that there is no surviving photograph of her, and she lived a large part of her life as an invalid.

The book is part murder mystery and part romance with a peculiarly Victorian melodramatic feel about it. It was written at a time when the wearing of beards was not fashionable and so it seems an odd choice of disguise for someone determined to commit murder most foul. Haynes presents the reader with a moral dilemma that her murder victim is wrestling with; what should someone do if they discovered a crime that had been committed that had never been discovered and never even suspected?

Dr John Bastow in mentioning this professional and moral dilemma to Sir Felix Skrine K.C, the cleverest criminal lawyer in the country, sets off a chain events that leads to his murder and more. On the day that he is found murdered, shot inside his own locked office, he had already refused his assistant Basil Wilton’s request for the hand of his daughter, Hilary, dismissing him on the spot for his audacity. There are precious few clues, save for a letter Bastow was writing to Skrine about their conversation, a missing box in which the findings of his scientific research were held, and near the corpse a scrap of paper which bears the legend “it was the man with the dark beard”.

Wilton is the prime suspect, but before Stoddart has got much further with his investigation, the book lurches in a slightly unexpected direction, when Skrine, acting as Bastow’s executor and in loco parentis to Hilary and her invalid brother, Fee, sells the family home, uproots them to a village where his wife is buried, thwarts Hilary’s romantic aspirations as he has designs on her himself, and is reluctant to finance Fee’s treatment. In other words, he plays the wicked guardian so beloved of Victorian melodramas.

We get back on to the murder track when Hilary learns that Wilton has now married Bastow’s former secretary, who has mysteriously come into money. Within weeks of the marriage, his new wife is murdered, again Wilton being the last to see her alive. It looks black for Wilton especially as some evidence is found that seems to incriminate him. He stands trial but the jury cannot agree a verdict. A retrial is ordered which buys Stoddart, who was never convinced of Wilton’s guilt, to find the evidence he needs to bring the real culprit to justice.

The case revolves around theatrical beards, poison, a bit of blackmail, and a marriage that had gone sour. In truth, the culprit is easy to spot, but it is an enjoyable, light read from a writer that deservedly has been rescued from obscurity. The rest of her murder mysteries are on my ever-growing TBR pile.

April 18, 2023

Clouds Of Witness

A review of Clouds of Witness by Dorothy L Sayers – 20230330

Lord Peter Wimsey is not everybody’s cup of tea either as a character or an amateur sleuth, I am immediately taken back to Ian Carmichael’s portrayal of him whenever I come across him in print, but he does get involved in some entertaining, if somewhat improbable, escapades. Clouds of Witness is the second in Dorothy L Sayers’ series, originally published in 1926, and sees her amateur sleuth involved in a case that is too close to home for comfort.

Lord Peter cuts short his jaunt sur le continent when he hears the astonishing news that his brother, Gerald, the Duke of Denver, has been arrested, accused of the murder of Denis Cathcart at a shooting lodge in the wilds of Yorkshire which he had hired, as you do, for the season. To add to the intrigue Cathcart is the fiancé of Mary Wimsey, sister of Peter and Gerald, whom Gerald had just accused, based on information received in a letter that he can no longer find, that Cathcart was a card sharp. Gerald protests his innocence but will not give an explanation as to his whereabouts at the time of Cathcart’s death nor why he was up and about at 3am when he was discovered by the body.

Mary’s behaviour at the time of Cathcart’s demise also requires some explanation, which she is loathe to give. She too was fully dressed at 3am when she found her brother by the body. Why and why had she placed a suitcase in the conservatory?

Lord Peter Wimsey cannot resist the challenge of preserving the family’s honour by riding to the rescue of his brother. Aided and abetted by his police ally, Inspector Parker, Wimsey finds that in proving Gerald’s innocence he is likely to incriminate Mary and by establishing that Mary could not have killed her fiancé he is making Gerald’s ultimate fate more likely. He is on the horns of a dilemma, the only way out to save his siblings and the good name of the family is to find an alternative explanation to Cathcart’s death.

In doing so, Wimsey runs incredible and extraordinary risks. He is shot at and wounded, an injury from which he makes an astonishing recovery as shortly afterwards he is swallowed up by a bog and has to be hauled out by his ever-faithful valet, Bunter, and some farm hands, and then undertakes a perilous aeroplane journey across the Atlantic having secured some vital evidence. Wimsey’s sense of family honour is sorely tested.

One of the fascinating points of the set up is that a peer of the realm cannot be tried for murder in an ordinary court setting. They must be tried by a special court consisting of their peers and this allows Sayers to produce some fascinating scenes as the trial proceeds, establishing the court scene where passages of the speeches for the prosecution and defence and the judge’s summing up are transcribed almost verbatim as a staple feature of crime fiction for decades to come.

Inevitably, there are family secrets which come out into the open, an extra-marital affair and a planned elopement with a socialist, by gad, and the key clues are a piece of blotting paper and a letter that was wedged into a window frame in an unexpected property. Sayers keeps the tension going as first one suspect and then another seem to be in the frame for the murder and while justice is done, the reader might feel a little cheated at how Cathcart’s death is resolved. The final chapter is fast and furious, wrapping up most of the loose ends, including release for a woman trapped in a violent and loveless marriage, and an opportunity for his Lordship and Parker to let their hair down.

It might not be the most complex or sophisticated of mysteries, but it is terrific fun.

April 17, 2023

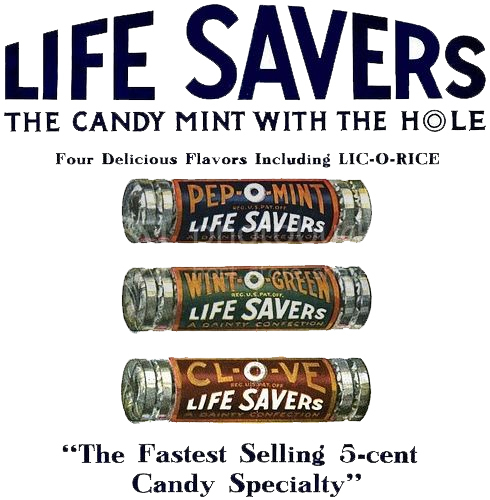

The Curious Tale Of The Mints With The Hole

Altoids were not sold in the United States until the twentieth century, by which time the Americans had their own curious mint, courtesy of an Ohioan chocolatier, Clarence Crane. Searching for an alternative to chocolate which would withstand the summer heat, he hit upon the idea of producing mints in 1912.

Crane’s mints were white in colour, round and peppermint flavoured, made using the same type of machine with which pharmacists produced their round, flat pills. To ensure that his mints stood out from the competition, he stamped a hole into the middle of each one. As their annular shape reminded him of life belts, Crane called his mints Life Savers, a name that was not without its irony as they were introduced in the year that the Titanic sank. They were advertised with the strap line of “For That Stormy Breath”.

Crane sold his business to E J Noble the following year. A consummate salesman, Noble soon established Pep-O-Mint, the original version of Life Savers, as a household name, partly through the morally dubious method of recruiting youngsters to sell them on commission. Marketing them as “The Candy Mint with the Hole”, he replaced the original cardboard containers which got soggy with tin-foil wrappers to keep the mints fresh.

Life Savers were introduced to Britain in 1916 and manufactured here from 1923, reaching the peak of their popularity in 1931 when sales topped 2.28 million packets. During the Second World War Rowntree’s manufactured Life Savers under licence but the war and rationing saw sales dwindle to almost nothing by 1947.

For Rowntree’s, the 1930s were its golden age, the decade in which the marketing genius of George Harris came to the fore, launching such best-sellers as KitKat, Smarties, Aero, Black Magic, and Dairy Box. He intended to create a mint akin to the Life Saver in 1939, but the advent of war put paid to those ambitions. However, in 1948, judging the conditions to be right he launched what he called Polos, a name, derived from Polar to denote the mints’ cool freshness.

Peppermint flavoured, white in colour, round, approximately 1.9 centimetres in diameter and 0.4 centimetres thick, and with a trade mark 0.8-centimetre-wide hole, there were twenty-three in a packet, tightly wrapped in aluminium foil backed paper. They were even marketed as “The mint with the hole”, capitalising upon Life Savers’ failure to protect their annular shape with a patent. Nevertheless, Rowntree’s felt it necessary to protect their position further by clearly marking on the packaging that the mints were manufactured by them.

Unable to compete with the domestic brand strength of Rowntree’s, Life Savers were withdrawn from sale in the UK in 1956. Subsequent attempts to relaunch them have met with failure.

Now owned by Nestlé, the Polo plant in York can produce 22,000 sweets a minute or 1.37 million packs a day. For those who crunch rather than chew their Polos, it is worth remembering that each mint is put under 75 kilonewtons of pressure, the equivalent of the weight of two elephants jumping on it. And, yes, the mint is made with a hole already in it.

The hole was also responsible for an early outbreak of EU-scepticism. On April Fool’s Day, 1995, Nestlé Rowntree’s marketeers announced that “in accordance with EEC Council Regulations (EC) 631/95” they would no longer be producing mints with holes. Cue national outrage. The following April 1st, inevitably, they suggested they were launching Polo Holes, described as “the hole with the mint”.

With its unusual shape backed by quirky advertising, Polos have found the recipe for suck-cess, maintaining their position as one of the country’s best-selling mints. Their diamond anniversary cannot pass unnoticed.

April 16, 2023

Lost Word Of The Day (28)

Pen is not technically a prefix but, according to The Oxford English Dictionary, is used in the formation of nouns and adjectives with the sense of nearly, almost, all but. The obvious example is penultimate which means almost last but not quite, the second to last.

A companion adjective but used in respect of centrality is penintime which was used in the late 17th and early 18th centuries to denote second to the innermost. An example of its usage would be “Venus is the penintime planet in the Solar system”.

One to lock away for future use, methinks.

April 15, 2023

Lost Word Of The Day (27)

Along with tying laces cleaning shoes with polish seems to be a lost art these days with shoes made of synthetic materials ruling the roost. However, when shoes were cleaned with polish, the owner of the pair, or probably the bootblack or a servant, would, like as not, wield a pannuscorium, a soft leather cloth. The derivation is quite straightforward, the amalgamation of two Latin nouns, pannus meaning cloth and corium, leather.

Pannuscorium, albeit separated into two words, was also a brand name for leather cloth boots and shoes for Ladies and gentlemen, the patent for which was held by Hall and Co of Wellington Street, off London’s Strand, boot and shoe makers to George IV.

An advertisement in The Freemasons’ Quarterly Advertiser of December 31, 1842 declared that “These articles have borne the test and received the approbation of all who have worn them. Such as are troubled with corns, bunions, gout, chilblains, or tenderness of feet from any other cause, will find the softest and most comfortable ever invented; they never draw the feet or get hard”. This wonder cloth was available to manufacturers, sold by the yard.

They were still being advertised in the mid-1890s. I wonder what happened to them.

April 14, 2023

Hamlet, Revenge!

A review of Hamlet, Revenge! By Michael Innes – 230326

In some senses this second outing for Michael Innes’ Scotland Yard sleuth, Inspector Appleby, is a classic country house murder mystery with a locked room element, but in reality it is as much a thriller. Originally published in 1937, I found the book difficult to get into with a first chapter containing a bewildering number of characters which, after a while, made it difficult to remember who was who as they all blurred into an amorphous mass. However, I fought off the temptation to put the book down and settle for an easier read and was rewarded with a clever, perhaps overly clever, puzzle that kept me guessing until the end.

The novel is set at Scamnum Court, seat of the Duke of Horton, where preparations are underway for a private performance of Hamlet. It is an elaborate affair, a special authentic stage is constructed, and the parts are played by some of the house party’s distinguished guests, including peers of the realm, Elizabethan scholars, doctors, a leading light of the London stage, and the Lord Chancellor, Ian Auldearn. To get us into a theatrical frame of mind, the text is laced with quotations, principally from Hamlet, and structurally the book is divided into four with a prologue, development, denouement, and epilogue.

There is an unsettling and apprehensive mood about the place, partly because of the gothic features of the building, a continuous leitmotif in the text, and partly because death threats in the form of quotations from the play have been sent to the Lord Chancellor. At a suitably dramatic moment in the play as Polonius cries out for help after being attacked, the Lord Chancellor, who is playing the part, is shot in front of the audience. It seems an incredibly rash and audacious murder and, although it was committed in front of an audience in a room where ingress and egress was prohibited, it is impossible to say whodunnit.

If the death of such a distinguished member of the government is not bad enough, the Lord Chancellor had a habit of taking state papers with him and had a particularly sensitive document, the leaking of which could destabilise international relations, on him. Were the papers safe and was the assassination the culmination of an espionage plot?

Appleby, on his way home from an evening at the ballet, arrives at his flat to find that the Prime Minister is there, and he is detailed to secure the papers and to catch whoever murdered the Lord Chancellor. On his arrival at Scamnum Court, Appleby finds an old friend, crime writer, academic and producer of the play, Giles Gott. Between the two, they set out to crack the mystery, but with up to 31 potential suspects, they have their work cut out.

What was the significance of the death threats? Were any clues to the motives and the dramatic nature of the murder contained in the plot of Hamlet? Was the murderer operating on their own or with a confederate and was the threat to the state papers a red herring or an integral part of the assassination? There is another murder, of a potential witness to the crime, and an assault on a scientist to muddle the picture further.

As befits a crime writer, Gott constructs a compelling explanation which seems to fit all the elements of the case and argues that it was the work of a solo avenger. His arguments are sufficient to convince the Chief Constable, with Appleby’s tacit consent, to make an arrest. Appleby, though, is uneasy and thanks to the sleuthing of two of the female guests, the real solution emerges, although, I have to say, it seems less convincing, especially around motivation, than Gott’s.

The book is uneven, in parts like wading through treacle, in others brisk and breezy. There are some nice touches – the gun hidden in Yorick’s skull, the black box voice analysis machine – and some humour, albeit in the form of the stereotypical Scotsman with a thick accent, the only concession to the lower orders that Innes makes and the language that describes the token non-white character, Bose, would be deemed beyond the pale these days.

If you enjoy complex puzzles that keep you guessing until the end, this is a book for you. I could take it or leave it though. On to the next.

April 13, 2023

Ale And Not So Hearty

To qualify for the all-important ATP designation (authentic Trappist product), the beer has to be brewed by monks, or under the direct supervision of monks, within the grounds of a Trappist monastery. Monies raised from the sale of the beer goes to maintaining the monastery with all other profits being donated to charities and community projects.

Belgium’s number of accredited ATP breweries has just reduced from six to five after the last monk at St benedict’s Abbey in Achel, Prior Gaby, has had to move out to the mother abbey in Westmalle. The monastery, though, will continue to produce its pale and brown beers with ABVs of 8% and 9.5% respectively, just without the ATP accreditation.

It is only a matter of time before the five other remaining ATP accredited breweries lose their status as the number of monks taking holy orders has dropped dramatically and most of 100 Trappist monks left are getting on. Of the five remaining authentic Belgian Trappist beers, only one – Westvleteren – is actually brewed by monks from the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance. Lay brewers supervised by Trappists produce the others.

Although the tradition of monastic beer production is centuries old, the ATP accreditation was only introduced in 1997 to stop other breweries from misusing the Trappist name to cash in on the growing popularity of craft beers in general and small Belgian brews in particular.

It will be a sad day if the tradition dies out completely.

April 12, 2023

Everybody Always Tells

A review of Everybody Always Tells by E R Punshon – 230323

Surely one of the reasons that E R Punshon’s Bobby Owen series fell into undeserved obscurity is the poor choice of titles. Everybody Always Tells is not one that leaps off the book cover and demands that the reader invests some time in reading it. The title comes from Owen’s oft repeated, at least in this book, and somewhat optimistic view that eventually everybody tells the truth, but the auditor is to be alert enough to recognise when the truth is being told and about what.

This is the twenty-seventh outing for Bobby Owen, now an officer in the upper echelons of Scotland Yard, originally published in 1950 and now reissued by the inestimable Dean Street Press. It is remarkable to think that Punshon was in his late seventies when he wrote this and for that reason alone, he can be forgiven a certain formulaic feel to the structure of the book. There is the set-up, some detailed police procedural work, a review of the facts and theories garnered to date with Olive, Owen’s wife, operating as a sounding board and a more than diligent provider of direction, some more investigation, and then the denouement involving a dramatic set piece in which our hero puts himself in jeopardy to bring the case to its conclusion.

Bobby Owen will never be short of interesting cases while he is attached to the human crime magnet that is his wife. The book starts with the couple, Bobby more the reluctant bag carrier, bargain-hunting in a famous store when a necklace is placed in Olive’s handbag. The person who put the necklace there is identified as the eccentric aristocrat, Lord Newdagonby, and when Bobby visits him to find out why, he walks into a darker mystery. Newdagonby’s daughter, upon whom he dotes, has received several death threats. While Bobby is there, the alarm is raised and when the rescue party reach a room on the upper floor of a rabbit warren of an old pile, they find Newdagonby’s son-in-law, Ivor Findlay, in his death throes, having been stabbed. He dies soon afterwards. Why was he killed and not his wife?

This is a form of locked-room murder mystery and there are a bewildering number of clues and possible motives, some red herrings, but, in truth, precious few suspects. There is marriage infidelity, a splash of existentialism, a fixation on Byron, an invention that is likely to revolutionise the industrial process, the literal cutting edge of technology, thwarted ambitions, two peep holes cut at a certain height, a poker, and two missing guinea pigs, about which Bobby Owen is obsessed to the irritation of all he meets but which, rather like Holmes’ dog that did not bark, hold the clue to the mystery.

This is another book in which Punshon has created an intriguing female character. Mrs Findlay, Newdagonby’s daughter, is portrayed as a restless soul, who is in search of her real self. She spent eighteen months exploring being good but ultimately found that she was not getting anything out of religion and is now exploring her darker, wicked self. She is a character rich in potential and I felt that a more energetic Punshon from his earlier days might well have made more of her. Instead, he allows Owen to reveal to her her folly to dramatic effect. She rushes off only to find herself in a life-threatening predicament. Naturally, Bobby rushes to her rescue but the woman has undergone such a Damascene conversion that any hopes that our hero had of bringing the culprit to justice are smashed to smithereens.

This is a well-written, intriguing murder mystery, perhaps not Punshon at his very best, but a book that is worth a read.

April 11, 2023

The Murder Of Roger Ackroyd

A review of The Murder of Roger Ackroyd by Agatha Christie – 230320

I have not read, let alone reviewed, much of Agatha Christie’s books. If I was pressed to explain why it is because so many have appeared, in one form or another, on the silver or small screen that many of their plot lines are familiar, even if I could not immediately place one with any particular book. The other reason is that there are so many reviews of each of the books that it is hard to come up with anything original to say about them. Still, not with any sense of imminent mortality, I thought it was high time I sat down with one of her best, most famous and, certainly, notorious novels, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, originally published in 1926 and the fourth in her Hercule Poirot series.

I am not a great fan of detective fiction novels that are narrated in the first person. The have an air of artificiality about them as the narrator has either to be present at every critical moment or has to be brought up to speed with an account, which might as well have been given in the third person in the first place. A reader from Mars, who had not the faintest idea about the plot of this book, might have been put on their guard when Christie ditched the previous faithful but dense Hawkins, now improbably away in the Argentine, as narrator in favour of James Sheppard, the doctor at King’s Abbott.

The good doctor is there the evening that Ackroyd is murdered, one of the last people to see him alive. Ackroyd consulted him because Mrs Ferrars, who has just committed suicide, had told him that she had poisoned her husband and had sent him a letter explaining that she had been blackmailed and giving him the name of the blackmailer. However, Ackroyd stops short of reading who that is in Sheppard’s presence. Why did he do that? Was there something which, in retrospect, he did not want Sheppard to know?

Sheppard is on the scene when the door to Ackroyd’s study is broken down, having been summoned by an anonymous and mysterious phone call purporting to be from the butler, Parker, announcing that Ackroyd had been murdered. The account of the murder and the investigations of Poirot, who just happens to have retired to the village to grow marrows, that Sheppard produces is accurate as far as it goes, as Poirot concurs when he has read it, but is vague on certain particulars, not least on a crucial ten minutes and why a chair had been moved, a piece of evidence that the Belgian sleuth regards as crucial.

There is only a small and select group of suspects but each, as Poirot reveals, as the revolutions of his little grey cells begin to increase, has been less than honest in their accounts of their movements, status, and their motives. There is also some uncertainty as to the precise timing of the murder which could have a significant bearing on the cogency of some of the alibis. There are red herrings galore, some amusing if stereotypical characters, clandestine marriages, a bit of cocaine addiction, a convenient ship’s steward on their way back to Liverpool, a feather, a wedding ring, and an overwhelming sensation that things look bad for Ackroyd’s wayward nephew, Ralph Paton.

There is a remarkable twist at the end, which a diligent reading of the text might have prepared the reader for even if they were not aware of the controversy surrounding the book. It is rather effortlessly and seamlessly achieved, particularly when compared with the abruptness that Richard Hull was forced to employ in his The Murder of My Aunt, an effective piece of plotting that makes for a powerful ending.

I was particularly taken by the imaginative use of a piece of then modern technology, the Dictaphone. It made for a refreshing change from the usual gramophone or wireless playing in an empty room.

Christie is a master storyteller, writing in a deceptively simple style, an art in itself. Poirot is his usual annoying, omniscient self but, as he likes to remind us, nothing gets past him. It is easy to see why this book was voted the best crime novel ever by the British Crime Writers’ Association in 2013.