Martin Fone's Blog, page 85

May 29, 2023

The May Bug – Britain’s Locust

Once so common and deemed a major agricultural pest, cockchafer numbers sometimes reached biblical proportions, as in Ireland in 1688. “When towards evening or sunset, they would arise, disperse and fly about, with a strange humming noise, much like the beating of drums at some distance; and in such vast incredible numbers, that they darkened the air for the space of two or three miles square”, the naturalist Thomas Molyneux observed. “The grinding of leaves in the mouths of this vast multitude altogether, made a sound very much resembling the sawing of timber”.

France was regularly ravaged by cockchafers. In 1320 the authorities in Avignon hit on a novel method of controlling them, summoning them to court and ordering them, on pain of death, to leave. Unsurprisingly, the stubborn cockchafers ignored the court’s strictures. In 1775 a farmer near Blois employed children and the poor to collect and destroy them, paying a bounty of two liards a hundred, and in a few days, they had collected fourteen thousand.

The Reverend Bingley noted, in Animal Biography (1813), that in 18th century Norfolk cockchafers were so rife that one farmer had collected eighty bushels of them and “the grubs had done so much injury that the court [of Norwich], in compassion to the poor fellow’s misfortune, allowed him twenty-five pounds”.

Well into the twentieth century the arrival of cockchafers en masse was a moment of marvel and dread for farmers and gardeners alike, as The Manchester Guardian’s Country Diary for May 31, 1922, graphically illustrates. Their North Oxfordshire correspondent wrote that “every evening the garden hums with cockchafers”, finding “something pleasantly poetical about their droning, plundering flight”. However, there was a sting in the tail. “They have great appetite and if this season suits their families as well as last would seem to have done, they bid fair to be as thick next year as Egypt’s locusts and will strip the trees; another reason for enjoying to the full this lovely verdure while it is here”.

With such an abundance of grubs and beetles, inevitably their culinary potential was explored. Molyneux recorded that the “poorer sort of Irish native had a way of dressing [cockchafer larvae] and lived upon them as food”. In France, according to Henri Miot’s Les Insectes Utiles (1870), handfuls of freshly harvested cockchafer grubs, seasoned with salt and pepper, rolled in a mix of flour and fine bread crumbs, and wrapped in liberally buttered baking paper or foil, were baked on the hot ashes of a wood fire or in the oven for twenty minutes. “On opening the envelope”, he wrote, “a very appetising odour exhales, which disposes one favourably to the delicacy, which will be more appreciated than snails, and will be declared one of the finest delicacies ever tasted”.

The French Society of Cultivators, keen to establish whether an unbiased palate would eat anything, decided, according to The Food Journal (1871), to experiment on cockchafer larvae. Steeped live in vinegar for twenty-four hours, they were then dipped in a light batter made of egg, milk, and flour, and fried until golden brown. Served hot and crisp, at the Society’s banquet held at the Café Corazza in the Palais Royal in Paris, “two were placed on each plate, and it is boastfully recorded that those who ate one ate the other. But more; there were eighty guests and 200 worms, so perhaps some might have had three”.

Approximately thirty adult cockchafers, with their legs and wings removed, fried in butter and then cooked in a chicken or veal broth, made a single serving of a soup, said to taste like crab. Strained and eaten as a bouillon, it was served with slices of veal liver or dove breasts and croutons.

Instead of eating adult cockchafers, children have for over two millennia used them as a seasonal toy. A long piece of thread was tied to one of its legs, which the child held while the beetle was thrown into the air, making it into a sort of kite. As the cockchafer tried to escape, its flight pattern made a pleasing spiral shape.

Cockchafer populations plummeted in the mid-20th century thanks to the industrial scale usage of agricultural pesticides, but since restrictions were imposed, numbers are slowly recovering. The cockchafer, with its loud buzzing and that eerie thud on the window, is once more becoming feature of our late Spring evening soundscape.

May 28, 2023

Lost Word Of The Day (40)

One of my (many) bugbears and enough to make me want to throw the TV controller at the secreen is the invasion of multiple into the English English language, when several or a more specific number would easily do. It is sloppiness, taking the easy way out when a more precise enumeration would give more sense to whatever is being described.

Of course, it does require there to be precise descriptors for each number. Perhaps it is time to revive words such as decuple, meaning groups of ten, or sedecuple, used in the 18th century to describe sixteen or sixteenfold. And don’t get me started on the use of the preposition “of” after myriad.

May 27, 2023

Lost Word Of The Day (39)

With between ten and twelve per cent of the world’s population being left-handed, it is appropriate that they should have their own International Day. August 13th, since you have asked. Left-handedness has long been associated in this right-hand dominated world with awkwardness, clumsiness, and misfortune.

Scaevity, a noun from the 17th century, brought these prejudices together into one word. Meaning not only left-handed but also unlucky. It was derived from the Latin adjective, scaevus, which had the same connotations. Unluckily for scaevity, it has long fallen out of use.

May 26, 2023

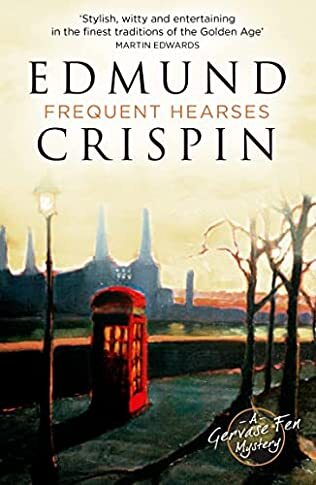

Frequent Hearses

A review of Frequent Hearses by Edmund Crispin – 230507

The seventh in Edmund Crispin’s Gervase Fen series, Frequent Hearses, which also goes by the alternative title of Sudden Vengeance, was originally published in 1950. Its titles come from a couplet from Pope’s Elegy to the Memory of an Unfortunate Lady; “on all the line a sudden vengeance waits,/ and frequent hearses shall besiege your gates”. In Pope’s poem a young lady commits suicide, and the poet calls for vengeance on all those whom he deemed responsible for her death. In Crispin’s novel, the young lady who calls herself Gloria Scott throws herself into the Thames and those who led her to this tragic moment of despair are one by one murdered.

Bruce Montgomery, Crispin’s alter ego, was an accomplished composer and wrote scores for films, including the Carry On series. He uses his knowledge of the film industry to good effect in an entertaining first half to his book, which satirises the rather laissez-faire way in which British films were made and the bitchiness and underlying tensions of those involved. Gervase Fen finds himself at a film studio in the role of a literary expert to advise on the plot for a life of Alexander Pope. As a professor of English Language and Literature at Oxford University he is well suited for the role, especially as it seems to involve little effort other than attending the odd script meeting and getting to the out of the way studio at Long Fulton.

As he arrives at the studio, he bumps into an old police associate, Inspector Humbleby who is there trying to shed some light on the true identity of Gloria Scott. Fen is drawn into the investigation, and soon three members of the Crane family, all involved in the film in which Gloria was to play a small part, are poisoned. Whodunit and why?

The why is telegraphed by the allusion to Pope’s poem. As is his wont Crispin is not shy in wearing his erudition in his text and there are the usual large helpings of literary allusions and direct quotations in the story. Aficionados of Conan Doyle will not fail to spot the Holmesian reference in the stage name of the young actress. The who aspect is trickier and, unlike in earlier stories, Fen plays a less central role in the solving of that mystery, although his role, like that at the film studio, is to advise, to point out, direct and give the benefit of his knowledge and expertise. Once the logistics and timings of the poisonings are clarified and mapped against the movements and alibis of each of the suspects, the identity of the culprit is obvious.

There is a distinct change of mood between the two halves of the book. The first is light and breezy, very funny in parts, bitingly satirical about post war Britain and the British film industry. The second part of the book has a much darker feel about it with a wonderfully atmospheric and thriller-like chase in a maze, a generous nod to a similar chase in one of M R James’ tales with a furtive glance to Greek mythology to boot. (Although Crispin loosely describes it as both a labyrinth and a maze, for a pedant like me it is clearly a maze).

As we get to know more about Gloria, the book takes an even darker twist. The girl has had an awful childhood and her hopes of making it in the film industry offer a route to better herself, only to have her aspirations toyed with to meet the lusts and jealousies of the Crane clan. In the modern argot, Gloria suffers extreme mental health issues as a consequence of workplace bullying. Her tale is tragic and this reader, at least, had growing sympathy with the individual who took it upon themselves to be her tormentors’ nemesis. I will never look on the autumn crocus in the same way again.

Although I did not think it matched some of his best, there is much to savour in the book.

May 25, 2023

Statue Of The Week (8)

Art has always had the ability to divide opinion. Take a new statue recently unveiled by Farnham Town Council, costing £19,500, and described as a “sensory, tactile, and interactive sculptural installation” symbolising “the enduring role of hands in craft for thousands of years”.

Some denizens of the town beg to disagree, comparing the arrangement of golden cones as resembling a “Dalek’s scrapyard” and “giant dunce hats”.

I will make my mind when I next pay the area a visit.

May 24, 2023

Conker Spirit RNLI Navy Strength Gin

A type of gin that I am enjoying exploring is Navy Strength Gin, a type not for the fainthearted or for those who blanche at paying more than £40 for a bottle. Still, it does the soul good to push the boat out now and again, especially when your purchase contributes to a good cause. Many distilleries spawned by the ginaissance are tripping over themselves to brandish their green and sustainability credentials, and while that is undoubtedly a good thing, you cannot but help thinking that unless there is a universally concerted effort, it is but a small drip in the vat of life.

Conker Spirit, based in Bournemouth and established in 2014 as Dorset’s first gin distillery have decided to take a different approach with their Conker Spirit RNLI Navy Strength Gin. It follows their template of excellence in craftsmanship and the use of the best possible ethical ingredients but is dedicated to the courageous men and women who risk their lives to save the skins of seafarers who have got into trouble. The Royal National Lifeboat Institution, for that is that fine body of people, receives a donation of £5 for every bottle sold.

The bottle has a dumpy, squat shape with broad shoulders, a small neck, and a coppery coloured screwcap. On the shoulder is embossed in the glass “Conker Spirit” at the front and at the back “Dorset Est 2014”. The label at the front has a serrated bottle top look about it using navy blue, white, and copper to good effect. They proudly display the RNLI logo, not once but twice, although only once in colour. The labelling at the rear extols the virtues of the RNLI quite rightly, but there is precious little about the gin itself, save that my bottle is number 997 from batch ten. While I am happy to endorse the RNLI, it would be nice to know something about the spirit other than it has an ABV of 57%. Perhaps that’s just me.

Anyway, after some digging, I find that there are nine botanicals involved in the mix, a fairly conservative line up of juniper, coriander seed, angelica root, orris root, and cassia bark, with bitter orange peel and fresh lime peel providing the citric notes and marsh samphire and elderberry giving a distinctive twist.

On the nose the aroma is distinctively that of juniper and in the glass the spirit is remarkably clear retaining its clarity even with the addition of a premium tonic – no louching here. In the mouth the juniper makes its presence known loud and clear, but the spirit is balanced with the citrus elements and the herbaceous notes. There is a pepperiness that comes through which together with the spicier botanicals produces a long and pleasant warming aftertaste. It takes the best of a classic London Dry adding a bit of oomph and a slightly saline, nautical twist to present a very well-balanced, moreish tipple.

If you are looking to dip your toe in the water with Navy Strength gins, this is a good place to sart.

Until the next time, cheers!

May 23, 2023

A Case Of Books

A review of A Case of Books by Bruce Graeme – 230504

Bruce Graeme’s books, I have found, can be sometimes a bit of a hit or miss affair, but this, the sixth in his Theodore Terhune series, originally published in 1946 and reissued by Moonstone Press, is one of his more accessible and intriguing. It is a bibliomystery and Graeme’s reluctant amateur sleuth, bookseller Terhune, finds himself drawn into and imperilled by an international plot to secure one of the world’s rarest and most valuable books.

Often, the trajectory of a detective story is a distinctive U-shape – it starts off well, lags in the middle as the sleuth gets to grips with the minutiae of the case, whittling down the suspects, checking and cross-checking alibis, and the picks up again as the field is narrowed and the denouement hoves into view. Graeme’s tale is unusual in that it gets better as it goes along, with a major set piece in the middle in the form of an auction and the plot taking a darker and more international perspective as we near the resolution of the case. This is not a conventional piece of crime fiction, but the ending is a bit of a damp squib.

An interesting contemporary insight is provided by Terhune’s ruminations on the perils to civilisation if the Germans were allowed to rise to a position of strength for a third time, Graeme, whose earlier books had been confident of an Allied triumph, perhaps revealing a little of the neurosis at the time over whether the Nazi threat had really been extinguished. There is also a reflection, earlier in the book, on how the fruits of someone’s life-long labours can be destroyed at a stroke prompted by the decision to split up and sell a carefully curated book collection.

The start, though, is straight out of the burgeoning catalogue of crime fiction tropes, a body found in a library, although it is a well-stocked library, containing one of the world’s best collections of incunabula and owned by Arthur Harrison, one of Terhune’s wealthiest and more demanding clients. There is evidence that the books have been rifled through, but the early return of Harrison’s domestic staff might have disturbed the culprits. Terhune is engaged to compile a catalogue of Harrison’s collection for the forthcoming auction.

While he, and his female accomplice, Julia MacMunn, are working at night in the library, it is broken into a second time and, although Terhune disturbs them, forcing one to drop a distinctive knife, and overhears a conversation in a foreign language, they get away. The knife, the suspicion that they are foreigners – after all, stabbing someone in the back is not an English way of committing murder – and there are some mysterious crosses cut into the turf of a farmer’s field, later to be repeated on the ear of a horse showing signs of the early onset of meningitis, Terhune and his policeman sidekick, the comedic Irishman, Sergeant Murphy, have precious little to go on.

Recognising that there is a book or something in Harrison’s collection that is worth committing murder for, Terhune and Murphy hatch a cunning plan to execute at the auction. To say all does not quite go as it should is a bit of an understatement in a gloriously funny and surprisingly suspenseful bidding war which Terhune engages with a man, obviously foreign, with a droopy moustache.

Terhune and Murphy appear to have reached the end of the road until Inspector Sampson arrives on the scene. Now seconded to an international operation to retrieve and repatriate art works looted by the Nazis, the attempts to steal something from Harrison’s collection takes on a more sinister, international perspective and the crosses, a Gaucho practice, begin to have special significance. Terhune’s shop is broken into, he and Julia are forced off the road and hospitalised after Terhune makes an impromptu visit to London to follow a theory of his own, and as he lies staring at the ward’s ceiling, he makes sense of it all.

As he is hors de combat, the physical resolution of the case is out of Terhune’s hands and while most of his reconstruction of what had happened turns out to be correct, the book ends on a rather flat note. Structurally, Sampson’s arrival, role, and revelations are so important to an investigation that seems to have run out of oomph that it has a deus ex machina feel about it and I was left wondering whether that aspect would have been better hinted at or gradually introduced earlier.

Nevertheless, this is an enjoyable and humorous book, with a welcome return of many of Terhune’s gloriously eccentric and annoying customers, and certainly one of the highlights of the series so far. Graeme has shown what can be done with the most conventional of set ups with a bit of imagination. If you have not discovered him, I recommend you start with this.

May 22, 2023

The Cockchafer Beetle

Melolontha melolontha; also known as: May bug, Mitchamador, Billy witch and Spang beetle.

Melolontha melolontha; also known as: May bug, Mitchamador, Billy witch and Spang beetle.A large, powerful winged object, about two to three inches long and half an inch wide, emerges out of the evening gloom, its progress heralded by a loud drone as it rapidly beats its wings. On a mission to feed and mate, it makes a bee line for a source of light, open windows or doors often proving irresistible. Sometimes a window pane is in the way, which it strikes with a dull thud, occasionally so hard that it lies upside down on the ground helpless, unable to right itself.

With a black head and first joint of its body, brown ridged wing cases, a hairy body, and a long, slender tail, its appearance does nothing to allay any sense of alarm. However, it neither bites nor stings. At close quarters, its most eye-catching feature is the row of orange, fan-like structures at the end of their antennae that can be opened at will. Males have seven and females six, used to locate breeding partners by detecting pheromones, for mating displays and combat, and for finding food, identifying dangers, and, possibly, navigation.

The clue to its identity lies in the time of year when it is most visible, late spring and May especially. It is Melolontha melolontha, a cockchafer beetle or a May bug, a type of scarab beetle. It has an impressively long list of regional nicknames, including spang beetle, billy witch, dumbledary, mitchmador, and bummler.

Often found near arable or open grassland, wooded parks, and gardens, May bugs rest during the day and fly to feed at dusk, their voracious appetite and penchant for roots and young leaves causing damage to crops, trees, and plants alike. After a week or so of feeding, they mate, the females laying batches of around twenty eggs in grassland soil, often lawns or fields, at a depth of between ten and 20 centimetres. Most females die after laying their first batch, but some lay up to eighty eggs in several batches.

The adult May bug’s life span lasts little more than five to six weeks, but it is the culmination of a life cycle lasting four to five years. Creamy-white larvae emerge from the eggs about a month after laying and live underground on a diet of roots, growing to about four to 4.5 centimetres in length. Known as rookworms, blackbirds extract them from my lawn with relish. If disturbed, they adopt a crescent-like posture.

After living underground for three to four years, in the autumn before they surface the mature larvae pupate, becoming beetles about six weeks later. They winter underground, often at depths of up to metre, before emerging when the soil warms up. Aside from the cockchafer’s individual life cycle, cockchafer populations seem to be particularly abundant every four years and appear in unusually large numbers every thirty or forty years.

May 21, 2023

Lost Word Of The Day (38)

Some words are so wonderful that you wonder why they ever sank into obscurity. One such is the adjective speustic which was used to denote something made, done, or especially cooked hastily as in I made a speustic meal to satisfy our unexpected guests. Perhaps the first syllable’s homophonic similarity to the consequences of partaking of an under-prepared meal led to its decline.

Nonetheless, I look forward to seeing some speustic food joints popping up in the not too distant future.

May 20, 2023

Lost Word Of The Day (37)

For the fissiparous by nature there is nothing like a good schism, but what do you call someone who founds or leads a schism? A schismarch, of course, a word that has fallen out of use since its heyday in the 17th century.

One of the features never to be associated with a schismarch is mediocrity. They are either wildly successful or their movement is a damp squib. Opinion is divided as to whether that is a good thing.