Martin Fone's Blog, page 2

October 9, 2025

Sphygmomanometer

A visit to a doctor’s surgery often involves a check on blood pressure. To do that one of the patient’s arms is put inside an inflatable cuff which collapses and releases the artery under the cuff in a controlled manner and is attached to a mercury or aneroid manometer which measures the pressure. The machine is technically known as a sphygmomanometer.

The heart pumps blood to all parts of the body and as the blood flows through the arteries and veins, it presses up against the walls with varying degrees of strength. The strength or weakness of this pressure is what is known as blood pressure and readings comprise of two elements. The systolic measures the pressure when the heart squeezes blood through an artery and the diastolic the pressure when it relaxes after each contraction. The reading is represented as systolic over diastolic and the outcome can either produce a nod of approval from the doctor or a sharp intake of breath.

The ancient Chinese had recognized that blood flowed around the body through blood vessels and developed theories on how the blood system worked. Similarly, scholars in India had gleaned some knowledge of the circulatory system and, in particular, the importance of the pulse. However, a more systematic and, dare I say it, a more scientific understanding of circulation and the circulatory system had to wait until the early 17th century.

William Harvey, who began teaching about circulation in 1615 and published in 1628 his tome, Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus, which became the foundation stone of the study of circulation and is still widely regarded today. Having established the correlation between heart rate and pulse, it was possible to determine blood volume and blood pressure, which the Reverend Stephen Hales was the first to do, in 1733. He measured the blood pressure of a horse by inserting a long glass tube upright into an artery and noting the increase in pressure as blood was forced up the tube.

However, it was another 150 years before the first sphygmomanometer appeared. Devised by Samuel Siegfried Karl Ritter von Basch in 1881, it consisted of a rubber bulb that was filled with water to restrict blood flow in the artery and a mercury column, to which the bulb was attached, which translated the pressure required to obscure the pulse completely into millilitres of mercury. In 1896 Scipione Riva-Rocci added a cuff that would go round the arm to ensure that even pressure could be applied to the artery.

In 1905 Dr Nikolai Korotkoff discovered the intrinsic difference between systolic and diastolic blood pressure, which corresponded to the sounds within the arteries as pressure was applied and then released. Known as Korotkoff sounds, the use of systolic and diastolic sounds is now standard in blood pressure measurement.

So now we know!

October 8, 2025

Murder With Relish

A review of Murder With Relish by Guy Cullingford – 2508

I came across Guy Cullingford through a short story in Martin Edwards’ British Library Crime Classics collection Cyanide in the Sun, a tale that was both inventive and brought a smile to my face. Her, Guy Cullingford is the pseudonym of Constance Taylor, first novel was Murder With Relish, originally published in 1948 although set in the 1930s when there was no whiff of food rationing.

Revenge is a dish best served cold, they say, possibly with a lacing of Lea and Perrins Worcestershire Sauce or fish paste or salt. The ingredients for Cullingford’s tale may be familiar – impecunious children waiting for their mother to die to die and to inherit a share of her fortune which will ease their troubles and an overpowering desire for revenge – but in her hands she has come up with an unusual take.

Mrs Bonnet, although she is not actually married, has been the cook at the Everard’s household for fifty years and has formed an affectionate bond with her mistress to whom she is both devoted and will fearlessly defend. After an unhappy marriage to a wastrel Mrs Everard was left with six children, one of whom, a pretty, charming daughter called Judith had died young. Mrs Bonnet had seen them all grow up and held varying degrees of affection for them. Her favourite was the youngest, Arthur, who to the shock of the family was soiling his hands with manual labour, working as a partner in a local garage.

Of the rest, Dennis is a gambler and would-be writer, who was banished to South Africa for a time after attempting fraud to clear his debts. Now returned he is back to his old ways and is being pressed to pay his gambling debts. Randolph is ostensibly the most successful but his income does not match his and his wife’s expensive habits and tastes and the unpaid bills are mounting up. Helen has a chip on her shoulder, wanting both to free herself from her domineering mother and to settle a score for years of what she perceives as neglect. George, who is trying his hand as a farmer and is in an unhappy marriage, has resorted to drink to forget his mounting financial worries.

After a meal to celebrate her birthday which all her children attend and prepared by Mrs Bonnet, Mrs Everard collapses in agony and despite being nursed by her faithful cook, she dies. The doctor puts it down to the consequences of a heavy and rich meal on a tender gastric system. Mrs Bonnet, though, suspects foul play – after all, the Everard brood have reason enough to want their mother dead – a suspicion strengthened when she realizes that the only point of difference between what her mistress had consumed and her children was Worcestershire sauce, a bottle of which she found discarded under the dining room window.

Mrs Everard’s last words were “No inquiry” and in respect for her employer’s desire for no adverse publicity to be brought on the family, Mrs Button carries out her own investigation into the death. She proves to be particularly adept at gathering vital clues but having the clues in front of you is one thing and being able to draw the right conclusion from them is another, especially when your mind is prejudiced. She hatches a plot to wreak revenge on the family with catastrophic results for nearly everyone.

The story is well told with enough and twists and red herrings to hold the interest, with an ironic denouement in terms of the survivors of the storm unleashed by the sleuthing cook. Structurally, though, the final chapters clearing up the mess do sit a little uneasily with the rest. Nevertheless, her characters are believable and Mrs Bonnet is a fascinating character study of a faithful servant, set in her ways, and determined to do what she believes is both her duty and what is for the best.

The book does not take itself too seriously, injected with a fair amount of humour, and offers a fascinating insight into life up and below stairs. Cullingford’s story must have made her contemporary readers long for the days when food was unrestricted and they could enjoy the pleasures of savoury eggs. She had on her hands the recipe for success!

October 7, 2025

Shrapnel

The technical definition of shrapnel is “an artillery projectile provided with a bursting charge, and filled with lead balls, exploded in flight by a time fuse”. It was a deadly and game-changing addition to the armaments of the British military and relects the name of its creator, Henry Shrapnel.

In the late 18th century cannons fired some form of exploding anti-personnel shell, known as canister and grape-shot, but they lacked the range that was often crucial in the heat of battle, rarely able to exceed 300 yards. Born in Bradford-on-Avon in 1761, Shrapnel entered the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich at the age of eighteen and began to conduct experiments to develop an effective long-range bursting shell that could be used against massed troops.

Initially, he tried to improve on existing ideas such as a hollow ball filled with explosive which was reliant upon the outer shell to shatter into jagged fragments, but none met his exacting requirements. Eventually, he decided to take a hollow sphere which he only partially filled with explosive, filling the rest of space with musket balls and adding a fuse to the filling hole. He then was able to develop a casing that was strong enough to withstand the forces from the initial propulsion but weak enough to be shattered by the bursting charge and produce a fuse that could be relied upon to explode at the requisite time.

After tours of duty abroad, Shrapnel was eventually able to demonstrate his “Spherical Case Shot” to the War Office, but they were slow to adopt it, the first recorded use of the shells being during the attack on Dutch Guyana and the capture of Surinam in 1804. It made Shrapnel the Georgian equivalent of an overnight success, earning him promotion to lieutenant colonel and the appointment of Assistant of artillery, a post which enabled him to carry out tests on his various inventions and innovations at the Carron iron foundry near Falkirk.

British gunners around the world soon attested to the deadly power of Shrapnel’s shell and the British Navy saw its potential to clear the decks of enemy ships in battle. Admiral Sir Sydney Smith was so impressed he even paid for a large order of the bursting shells out of his own pocket.

Shrapnel’s invention also helped thwart Napoleon’s sweep across Europe. It was first used in the battle of Vimeiro on August 21, 1808, and when Napoleon heard of the British success and the new weapon deployed, he ordered that the battlefield be swept in case there were any unexploded shells tat his experts could study and copy. At the battle of Waterloo, General Sir George Wood, Wellington’s artillery commander, was firmly of the opinion that “without Shrapnel’s shells, the reco very of the farmhouse at La Haye Sainte, a key position in the battle, would not have been possible.”

Despite his shell’s prominent role in defeating Napoleon, Shrapnel remained an unsung hero, ironically because his invention was so important the government wanted it shrouded in secret. He was eventually awarded a pension of £1,200 but King William IV died before the baronetcy he was promised could be conferred upon him. He died in 1842 in Southampton and was buried in the family vault in Bradford-on-Avon.

Technology moved on and altered the shape of the shrapnel shell, although the central principle remained unaltered. Its deadly impact in the open led to the horrors of trench warfare in the First World War, used as a way to counter its effect. Henry Shrapnel may have been forgotten, but his legacy and his name lives on.

October 6, 2025

Cyanide In The Sun

A review of Cyanide in the Sun, edited by Martin Edwards – 250821

Cyanide in the Sun is the second collection of short stories with a holiday theme that Martin Edwards has curated for the British Library Crime Classics series, eighteen in all, some very short, others longer, some by familiar names, others by writers who have long faded into obscurity. A sequel to Resorting To Murder, it is fascinating to note how many were originally published in newspapers, reflecting a time when a newspaper was designed to be pored over at leisure and was willing to devote space to literature rather than pursue advertising revenue.

Holidays can be a time when people’s guard are down, when the usual routine is disturbed and when you rub shoulders with people you would not usually encounter in places you do not normally frequent. Even if the specific forms of murder can be limited, a fall or a drowning, in the right hands there are opportunities for an intriguing and thought provoking mystery. As with all collections some stories are more successful than others, although there was not one that made me throw the book down in despair.

Of course, the prospect of going on holiday can fill some people with dread, a theme that Celia Fremlin, an author I had not come across before, explores in The Summer Holiday, one that comes complete with a twist that took me by surprise. Perhaps the story that comes closest to straining the theme is Will Scott’s A Holiday by the Sea, which features the tramp, Giglamps, and his morose fellow traveller, Cheery. Believing themselves to be on the track of a notorious and wanted smuggler, The Admiral, the pair hide in a furniture van that takes them to Margate, where their adventures begin. It turns out to be a wild goose chase of sorts and, as Giglamps himself observes, they did not see the sea in their eight hours there and barely smelled it. Nevertheless, it was a funny and engaging story which made me want to read more of Scott.

The collection takes its title from the Christianna Brand’s contribution, one of the more familiar names in the collection, and features a serial killer who runs wild in a seaside resort but then gets a taste of their own medicine. It is a cleverly worked tale involving a simple but effective method of dispatching their victims. The biter bit as a theme is also explored in Michael Gilbert’s Even Murderers Take Holidays.

My particular favourites included Anthony Berkeley’s Mr Bearstow Says, a clever, twisty tale, long enough to explore the complexities of the situation, but crisp enough to maintain interest throughout. The Summer Holiday Murders by Julian Symons is the longest story and finishes the collection, and comes complete with a tangled plot involving murder and deception amongst a party on a coach tour around the resorts of southern England.

Other familiar names include Michael Innes whose series detective Appleby makes an appearance in the brief Two on a Tower while any contribution from Ethel Lina White is to be welcomed, especially if it is of the standard of the sinister but ultimately heart-warming, The Holiday.

For me, though, the joy of reading a collection like this is to discover writers that are new to me. I enjoyed the book’s opener, Guy Cullingford’s Kill and Cure, so much that, rather like Victor Kiam, I rushed out and bought her first novel. And where else are you likely to come across the mysterious Christopher Bobbett, about whom no one seems to know anything, according to the authoritative introductory notes to each story, but whose The Secret of the Mountain stands the test of time? For an aficionado of Christopher Bush it was a tad disconcerting to find a sleuth by the name of Travers who predates Bobbett’s incarnation by a couple of years.

This is a collection ideal to be read in a deckchair with most of the stories of a length to barely disturb a nap. The best thing since sliced bread, you might say!

October 5, 2025

H-Day

At 4.50am on September 3, 1967, drivers in Sweden were required to drive on the right side of the road rather than the left. This was the second time such a switch had been made: in 1718 such road users as there were, carts pulled by oxen or horses or horse riders, had used the right-hand side of tracks and roads but in 1734 the switch was made to the left.

Quite why, nobody really knows, but with the relatively low volume of traffic and the pace at which they travelled it presumably was accomplished without too much trouble, other than the occasional moan. With nigh on 2 million vehicles and a population of 7.8 million at the time of Högertrafikomläggningen (right-hand traffic diversion) or simply Dagen H (H-Day), it was much more of a logistical challenge, although one that made sense. Most vehicles produced in and imported into Sweden were left-handed and the move would align them with their Scandinavian and European neighbours.

However, since 1916 the requirement to drive on the left had been enshrined in law, even though it was discussed annually in parliament between 1920 and 1939. In 1955 there was even a national referendum held on the subject with the advocates of the right-hand side arguing that it would lead to safer overtaking while the “lefties” based their appeal on custom and emotion. 83% of the voters cast their ballot to stay on the left-hand side with only 15% wanting change.

Even after such a decisive decision, the lobbyists for the change would not go away. Eventually, in 1963 the Swedish parliament voted through legislation that meant that they would switch to driving on the right on September 3, 1967. And so began an enormous logistical exercise.

Roads, junctions, roundabouts, flyovers and all the other paraphernalia of road usage had to be redesigned and on the night before the change some 360,000 signs were changed. A major public information campaign had been run, informing people what was going to happen that day and around 130,000 reminder signs featuring a large H for Höger, which means right in Swedish, were erected along streets and roads. Drivers would have a H-sticker on their dashboard to reinforce the message and a speed limit of 30 kph in built-up areas and 50 kph on all other roads was imposed on the day.

The cost of the exercise was about SEK 628 million, about £60m. and the careful planning seemed to have paid off. Only around 150 minor accidents were reported that day and during the whole month of September 1967 59 people were killed in Swedish traffic accidents, down from 99 the previous year. The drop is probably due to drivers being more alert immediately after the switch over but casualty rates began to rise again as drivers relaxed, reverted to old habits, and, in an emergency, their natural instincts inculcated over years of driving on the left would kick in.

It would be a brave government to contemplate such a switch today.

October 4, 2025

A Bad Day At Work

This is not a story for cleithrophobes. If you think you are having a bad day at work, give a thought to Betty Lou Oliver, a lift attendant in the Empire State Building. On July 28, 1945 the twenty-year-old was on duty when at 9.40am a US Air Force B25-Mitchell bomber piloted by Lt Col William Smith flew straight into the building in poor visibility, killing three on board and eleven in the building.

Thrown from the lift that she was operating at the time of the impact, Betty suffered severe burns and broke several bones. Mercifully, she survived but that was not the end of her ordeal by any stretch of the imagination. After being bandaged up, she was stretchered into another lift, when, lo and behold, the extra weight caused its cables, already weakened by the crash, to snap.

Conscious and screaming, Betty plunged down seventy-five floors to the bottom, but, remarkably, she even survived that. A combination of the airtight shaft and the cables which had previously supported the lift piling up underneath it cushioned her fall.

Remarkably, she lived to survive the tale, earning herself a mention in Guinness World Records as the survivor of the longest lift fall, and lived to the ripe old age of seventy-four. She only visited the building once more, five months later, travelling in the same lift in which she made her unprecedented descent.

October 3, 2025

Maigret’s Holiday

A review of Maigret’s Holiday by Georges Simenon – 250817

Whatever is the French equivalent of a busman’s holiday, Maigret certainly had one when he and his wife took their annual vacation to the Atlantic coastal resort of Les Sables d’Olonne. Madame Maigret is almost immediately taken ill, initially thought to have been caused by the dodgy mussels they had both consumed but it was something more serious, requiring surgery and a stay in a convent hospital. Maigret dutifully phones up for an update at 11am each morning and visits for half an hour and seems strangely intimidated by the place.

As a murder mystery Maigret’s Holiday, originally published in 1948 and also going by the alternative titles of A Summer Holiday and No Vacation for Maigret, is not the most mind boggling you are ever going to encounter and the culprit is easy to spot. There are three murders with the prospect of more without Maigret’s intervention and he is dragged into the case when, after a visit to the hospital, he finds that a note had been secreted into his pocket bearing the message “for pity’s sake, ask to see the patient in room 15”.

Initially, Maigret is more interested in how the note got into his pocket and by the time he bestirs himself to respond to the desperate request, he finds that the occupant of room 15, a young woman by the name of Lili Godreau, the sister-in-law of an eminent neurologist in the area, Philippe Bellamy. She had fallen out of Bellamy’s car as he was bringing her back from a concert in La Roche-sur-Yon.

At a loose end and unaccustomed to the sense of freedom that being released from the shackles of the routine of working life brings with it, Maigret had imposed upon himself an almost rigid routine which included each afternoon visiting a café to watch a group of men playing bridge, one of whom is Bellamy. Invited back to his house, Maigret notices that Bellamy is discomfited by the sight of a young girl leaving the bedroom of Odette, Bellamy’s wife who has not left her room for some days because of illness, and dashing down the stairs and leaving the house.

Maigret spends a frustrating evening trying to locate the girl and the next morning is horrified to learn from the local police the next morning that she, Lucile Duffieux, had been found strangled. He redoubles his efforts to discover what has been going on at the Bellamy menage, discovering an illicit love affair, the revenge of a jealous lover and the whereabouts of Lucile’s brother, Emile, who has supposedly gone off to Paris to take up a new job but has not arrived. A silver knife, which Lili had mentioned in her delirious ramblings in front of a nun before her death, proves to be significant as does a disused cistern. The denouement involves a battle of wills between Maigret and the culprit.

While there are few surprises or twists and turns in a story where we follow Maigret around almost hour by hour, immersing ourselves in his struggle to become accustomed to a life of leisure in a town where his fame has gone before him and then his interest in a mystery that turns into an obsession. Given his unofficial status, he is on holiday, after all, and refuses to lead the official investigation, much of the tension in the story comes from whether he has met his match and whether he will garner enough evidence to turn his well-founded suspicions into a case that would satisfy a court.

Simenon’s books are short and breezy, more atmospheric and light touch than most crime writers, but in Maigret he has developed a fine and complex character whom I never tire of.

October 2, 2025

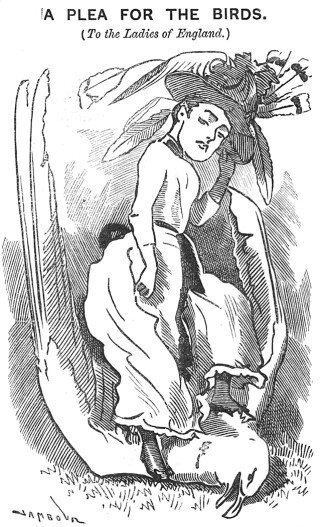

Another Feather In Your Cap

The practice of killing birds for their plumage was unsustainable and, for some, repulsive. Speaking in the House of Lords on May 19, 1908, Lord Avery opined that “it is evident that unless the slaughter is stopped, several species of birds will be in a few years be absolutely exterminated…it is not only the fact that several species will be utterly annihilated, but the victims are just he most beautiful; in fact, their beauty is their ruin. Moreover, birds’ feathers in hats are, I submit, not ornamental but, in the circumstances, repulsive”.

Lord Avery’s views were shared by Emily Williamson and her supporters who had, in 1889, founded the Society for the Protection of Birds, specifically to oppose the practice of using birds’ feathers for what they termed “murderous millinery”. Their campaigning eventually bore fruit with the passing of the Wild Birds Protection Act in 1908 and the Importation of Plumage (Prohibition) Act of 1921, the latter prohibiting the importation of certain types of feather.

Commercially, too, the practice of killing birds for their feathers was unsustainable, driving up prices as the providers of the plumage were driven ever closer to extinction. As ostriches were large, flightless birds, could they perhaps be domesticated, providing a plentiful supply of feathers through selective plucking in a way that left them unharmed and free to enjoy a happy and contented life, some mused?

The first serious attempts to farm ostriches for their plumage began in South Africa around 1865 with just eighty domesticated birds. By 1875 the number had increased to 32,000 and 154,000 in 1891 providing the vast majority of the 212,000 lbs of feathers the country was exporting at the time. South African farmers were reporting returns of 5000% on their initial investment in the birds.

Techniques improved. Anthony Trollope, writing in Illustrated London News in 1878, brought his readers news of a new South African process of sustainable feather harvesting. The bird was not denuded of feathers all at once but were selectively clipped near the body in small batches every seven months. The dry and shrivelled quill was then removed at a later date to minimise the bird’s discomfort.

Recognising the similarities between the climate of the South and West of the United States and the habitats enjoyed by wild ostriches and attracted by the profits made by South African farmers, it was not long before attempts were made to farm ostriches in America. However, it was not plain sailing.

Under the care of a South African ostrich farmer, Dr Charles Sketchley, a herd of two hundred ostriches were despatched from Cape Town via Buenos Aires to New York in 1882. By the time they had arrived in the Big Apple, 90% had died and after transportation to Anaheim by rail the survivors were so unwell that plucking had to be delayed.

E J Johnson, founder of the American Ostrich Company, had more success, not losing any of the twenty-three birds he brought over to New Orleans and then on to Fallbrook in California where they flourished over several decades. Ostrich farms gradually became established in America, offering a supply of feathers as well as tourist attractions with visitors offered the opportunity to ride on an ostrich or sit in a carriage drawn by one.

However, following the Wall Street Crash and the general economic downturn in the 1930s, the global appetite for feathers declined, becoming a niche luxury item, as they are today. With the rise in environmental awareness, there are also ethical concerns about live-plucking of ostrich feathers and, indeed, whether they should be domesticated at all.

The days of the ostentatious ostrich feather seem to be well behind us.

October 1, 2025

The Venner Crime

A review of The Venner Crime by John Rhode – 250815

The sixteenth book in the prolific John Rhode’s Dr Lancelot Priestley series, originally published in 1933, spins together an intriguing mystery from two seemingly disparate incidents albeit with a common pathological link. Usually the epitome of the classic armchair sleuth Priestly does actually bestir himself, travelling to amongst other places Barnsley, to sniff out clues. His interest in a case is as an abstract puzzle rather than anything with a human element, one in which the mathematics professor can exercise his formidable powers of deduction and logic and, unlike many, he will not rest until the solution has been discovered, no matter how unpalatable the truth.

A post prandial conversation between Priestley, Sir Alured Faversham, the country’s leading pathologist, and Superintendent Hanslet of the Yard’s CID turns to a consideration of the mysterious disappearance of Ernest Venner, who, according to his sister, Christine, simply walked out of the flat with an attaché case, saying that he would be back later, but has not been seen since. He had told his secretary at his business that he was going on a trip for a few days.

There had been more than a whiff of controversy over Venner earlier with the death of his uncle, Dennis Hinchcliffe, from what looked like strychnine poisoning but which Faversham asserts in his role as pathologist, after conducting a post mortem with no one else in attendance, to have been a case of tetanus poisoning sustained from a nasty wound on the victim’s hand. Such is Faversham’s eminence that his judgment is accepted nem con and the unfortunate Hinchcliffe’s death is ruled as accidental, enabling Venner to inherit the considerable sum of £100,000. Within two days of receiving the legacy Venner disappears, having used some of the money to bail out his ailing company.

The third section of the story introduces us to the strange story of the death of Charles Alcott whose frozen body is found in a snow drift close to Faversham’s country home of Markheys. The victim’s body has very little on it in the way of worldly possessions but there are two documents in his pocket and a laundry tag on his collar that identify him as Alcott. One carries the address of Faversham’s house and the great man is prevailed to come down from London – he has had to shut Markheys for the winter because of losses sustained in injudicious investments, both a source of great regret to the great man – and he immediately identifies the victim as a former employee of his, a laboratory assistant.

Again, Faverham’s repute puts an end to the matter and as there are no obvious signs of injury on the body, Alcott’s death is put down to exposure. However, Priestley cannot get past in his mind the seeming coincidence of the disappearance of one man into the blue and the sudden emergence of another, who had left no trace of his movements, again out of the blue. Was there a link and, if so, what was it?

The clues are all there in a narrative that leads us through an examination of the circumstances of Hinchcliffe’s death, Venner’s disappearance, his business affairs, Christine’s possible motives given she was displaced as beneficiary to the uncle’s estate, and her association with the somewhat disconcerting lawyer, Coleforth, until Priestley is in a position to draw the only logical conclusion from the facts before him. The final chapter, a tad melodramatic for my taste, sees the professor in a deadly duel with the culprit with two phials of poison, almost his Reichenbach Falls moment.

The culprit is fairly easy to spot, a case of the perils of bowing and scraping to your alleged betters, but this does not spoil the enjoyment of what is an unusual and entertaining story. Shame about the typos in the e-book edition. One of Rhode’s better efforts.

September 30, 2025

The Chadburn

Such is the market saturation or pre-eminence of a company’s product that its brand often becomes a portmanteau word to describe the device irrespective of its actual manufacturer. The description of a vacuum cleaner as a Hoover is a case in point and another example is a ship’s Engine Order Telegraph (EOT), often referred to as a Chadburn.

The EOT was the brainwave of an engineer, medical doctor and serial inventor, Charles Page, in the 1850s. It was a device that facilitated communication between the bridge of a ship and the engine room, comprising of a dial of various “ahead” and “astern” commands with a lever atop a pedestal made of a metal or alloy, usually brass. There would be one in the bridge and another in the engine room.

A black arrow at the centre of the dial shows what the other sration’s telegraph handle is set at. When the pilot calls an order, the black arrow on the EOT in the engine room moves to that position and a bell rings to signify that an order has been given. The crew in the engine room respond to the command by moving their handle to match the arrow which, in turn, causes the arrow on the bridge to match the handle’s position, thereby acknowledging the command.

Chadburn Brothers of Liverpool were producers of optics, marine instruments, and scientific gauges, even describing themselves as “opticians etc to HRH Prince Albert”. In 1870 William Chadburn submitted an application for a patent on a communication device to be used as a means of transferring navigational signals from the bridge to the engine room.

By 1875, Chadburn & Son were producing their brass EOTs. With a range of commands such as Full Ahead, Half Ahead, Slow Ahead, Dead Slow Ahead ,Stop, Dead slow astern, Slow Astern, Half Astern and Full Astern on a dial, it was operated by moving the lever in the required direction, which rang the telegraph bell in both the bridge and the engine room.

As luck would have it William lived two doors away from Thomas Ismay, founder of the prestigious White Star Line. Their friendship developed into a business relationship and soon Chadburn was producing instruments for the line including the EOTs and steam whistles on the ill-fated RMS Titanic. Chadburn advertised themselves as manufacturers of telegraphs used in vessels of various navies and mercantile marines with over 3,000 using a Chadburn & Son telegraph by 1884.

Nowadays, on most modern vessels with direct combustion engines or electric propulsors, the main control handle on the bridge acts as a direct throttle with no intervening engine room personnel.

As for Page, in a groundbreaking experiment he demonstrated the presence of electricity in an arrangement of a spiral conductor, advocating its use for medical treatment, an early form of electrotherapy. By heightening the electrical tension or voltage, he produced what he called the Dynamic Multiplier.

Page’s experiments led to the invention of the induction coil, an important step in the development of the telephone, and he invented many other electromagnetic devices. He went on to contribute to the adoption of suspended wires using a ground return, designed a signal receiver magnet and tested a magneto as a source of substitute for the battery and even invented an electromagnetic locomotive.

The plaudits for the EOT, though, went to the Chadburns.