Martin Fone's Blog, page 9

July 31, 2025

Safe Seat

Only one passenger survived the recent Air India plane crash near Ahmedabad and after the metaphorical dust had settled on this tragic event, one of the obvious questions was which seat was Vishwashkumar Ramesh sitting in? It turns out that it was 11A on the doomed Boeing 787-8 Dreamliner. Is there something about that seat that, statistically, that makes it safer than any other?

Spectacular as air crashes are and with the potential for significant numbers of casualties, air travel is one of the safest forms of transport, with a fatality rate, about 1 in 13.7 million for each flight in the US, a study in 2024 in the Journal of Air Transport Management found, far lower than that of driving a car. Also encouragingly, 94% of passenger plane crashes, according to data compiled between 2001 and 2017 by the National Transportation Safety Board, have a 100% survival rate.

There has not been a formal study into which seats are the safest in the event of a crash but based on past crashes and inferences drawn from aeroplane design, it is possible to hazard an opinion. A crash happening with low energy and a low angle of impact, for example when a plane loses control on landing, is likely to result in the plane breaking in two.

Most of the kinetic energy is in the front which will barrel forward, making the rear of the plane the safer. This supposition was given further credence by a TIME review of seventeen seating charts for aircraft involved in accidents between 1985 and 2000 where there were both fatalities and survivors. They found that the seats in the back third of the aircraft had a 32% fatality rate, compared with 39% in the middle third and 38% in the front third.

As for row position, the middle seats in the rear of the aircraft had the best outcomes (28% fatality rate). The worst-faring seats were on the aisle in the middle third of the cabin (44% fatality rate). After a crash, those sitting nearest to the exits were most likely to get out alive.

Seats which are next to or close to the wings are likely to be safer because that part of the plane has a lot of structural reinforcement, so it can withstand more force. That said, that part of the plane is also sitting above the fuel tanks.

That all said, the chances of dying in an aircraft accident have less to do with where you sit and more to do with the circumstances surrounding the crash. If the tail of the aircraft takes the brunt of the impact, the middle or front passengers may fare better than those in the rear. TIME found that survival was random in several accidents, where those who were killed were scattered irregularly between survivors.

Airline safety experts say there is no safest seat on a plane. It is just luck so do not despair if you miss out on seat 11A!

July 30, 2025

John Trudgen

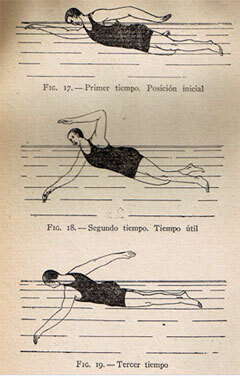

Readers of Joan Cowdroy’s Murder of Lydia may be mystified by a reference to a swimming stroke called the Trudgen. It was known as the racing stroke or the East Indian stroke and owes its origin to John Trudgen who, although born in Poplar in 1852, went out with his parents to Buenos Aires when he was eleven. There he noticed that the local children used an overarm action when swimming rather than the more customary breaststroke.

Returning to England in 1868, John developed a stroke based on what he had seen in Argentina for use in competitive swimming and the result was sensational. Reporting on Trudgen’s winning swim in a championship at Lambeth Baths in 1873 for the Swimming Record, R Watson wrote, “A surprising swimmer carried off the handicap; we allude to Trudgen ; this individual swam with both arms entirely out of the water, an action peculiar to Indians. His time was very fast, particularly for one who appears to know but little of swimming, and should he become more finished in style, we shall expect to see him take a position almost second to none as a swimmer.

I question, indeed, if the swimming world ever saw a more peculiar stroke sustained throughout a 160 yards race. I have seen many fast exponents retain the action for some distance, but the great exertion compels them to desist, very much fatigued. In Trudgen, however, a totally opposite state of things existed ; for here we had a man swimming apparently easy, turning very badly, and when finished, appearing as though he could have gone at least another 80 yards at the same pace. His action reminds an observer of a style peculiar to the Indians ,both arms are thrown partly sideways, but very slovenly, and the head kept completely above water”.

In essence, what Trudgen had done was develop an early version of what was to become the front crawl which gave him incredible speed over sprint distances and because it worked the arms and legs simultaneously but differently instead of simultaneously and in the same way as with other strokes such as the breaststroke it was less fatiguing.

The new style enabled Trudgen to continue to dominate swimming events, winning an English championship at Edgbaston reservoir in 1875. But soon his rivals emulated his style, improving on it to gain extra speed, dominating sprint and middle distance competitions in the years up to the first modern Olympics. It was also used as the stroke of choice in Water Polo.

John Trudgen may have slipped into obscurity but his name lives on in swimming circles, the stroke morphing into the front crawl. The modern version involves the swimmer swimming on one side, making an overhand movement, lifting the arms alternately out of the water. When the left arm is above the head, the legs spread apart for a kick. As the left arm comes down, the legs extend and are then brought together with a sharp scissor kick.

The right arm is now brought forward over the water and as it comes down, the left arm is extended again. The scissor kick is deployed every second stroke and involves spreading the legs and then bringing them together with a sudden snap movement.

July 29, 2025

The Fever Tree

One of the reasons, it is said, for the popularity of mixing a gin with Indian tonic water is because of the presence of quinine in the latter, a known antidote to malaria.

Quinine comes from the cinchona, a large shrub or small tree indigenous to South America and its bark, also known as Peruvian Bark or Jesuit’s Bark, one of several alkaloids it produces, all of which, with the exception of sulphate of cinchonine, are known for their medicinal properties in reducing or preventing fever. However, the most valuable by far is quinine which, according to a report of the Commissioners of Medical Officers of the Government of India, possesses “more than any other that can be named the confidence of medical practitioners [in India]”.

The name cinchona was once thought to be derived from the Countess of Chinchona, wife of a Spanish envoy of Peru, who, whilst visiting the country in 1630, contracted “an attack of the fever”, from which she was cured by using cinchona bark. Sadly, this story is almost certainly apocryphal, not least because of the variance in spelling, although spelling conventions at the time were not as rigid as they are now. What is certain, though, is that the healing powers of cinchona were known to Jesuit missionaries, who had learned about it “from natives during the years 1620-1630”. By the middle of the 17th century it had arrived in Europe, being used in Jesuit colleges in Genoa, Lyon, Louvain, and Ratisbon.

The arrival of cinchona to Europe must have come as a great relief to those suffering from fever and, particularly, malaria as “treatments” at the time included amputation, purging, blood-letting, the administration of herbs, rest, massage, hydrotherapy, and the use of a controlled diet. More unconventional remedies were to wear amulets, applying split pickled herrings to the feet, placing the fourth book of Homer’s Iliad under the patient’s head, throwing them into a bush in the hopes that in exiting they would leave the fever behind, and “the embrace of bald-headed Brahmin woman at dawn”. As late as 1886 writing in The November issue of The Indian Medical Gazette a Dr J Donaldson reported that he found “orally administered cobwebs of greater value than quinine”.

The first detailed description of a species of the cinchona, Cinchona officinalis, was made by the astronomer, Charles de la Condamine, who visited Quito in 1735 on a mission to measure an arc of the meridian, although it was found to have little therapeutic value. The first living plants seen in Europe were from the Cinchona calisaya species, grown at the Jardin des Plantes from seeds collected by Hugh Weddell in Bolivia in 1846.

For almost two centuries supplies of cinchona bark were imported into Europe from the countries where the tree grew naturally. There were four methods of harvesting the bark – stripping and renewing, scraping, coppicing, and uprooting – the latter method being employed to such an extent in South America that it led to a serious depletion in the number of cinchonas. The bark was then dried, crushed into small pieces and turned into tinctures, Robert Talbor, the physician of Charles II, being credited with the “elaboration and spread of cinchona bark therapy” in England.

Initially, there was much prejudice against cinchona in Protestant western Europe, given its particular association with the Jesuits, but as Ignace Voullonne observed, writing in the early 18th century, “the promptness of its effect and its infallibility finally triumphed over the multiple reproaches that were heaped upon it…by ignorance, prejudice, the ignorance of sects [and] the hatred of the parties”.

July 28, 2025

Cat And Mouse

A review of Cat and Mouse by Christianna Brand – 250620

Described as a melodrama and a thriller, I found Brand’s Cat and Mouse, originally published in 1950 and reissued as part of the British Library Crime Classics series, a bit of a difficult one to get into. In fact, after the first chapter I put it down, read something else, and then decided to give it a second chance. It was worth the perseverance, I think, but more than a tad melodramatic for my taste.

Part of my problem, I think, was its initial setting, the offices of a women’s magazine, Girls Together, where two of the hacks discuss a series of letters sent to the mag’s agony aunt, Miss Friendly-Wise, by a correspondent from Wales, Amista, who gives details of her personal life and her feelings for Carlyon. Due a holiday, Tinka Jones, the personification of Miss Friendly-Wise in human form, decides to go down to South Wales and look Amista up. The set up just did not get my juices flowing.

However, once Tinka gets to Wales, the story gets more interesting. Carlyon, with whom Tinka immediately falls in love, denies the existence of Amista and seems to resent the intrusion of this stranger into his remote sanctuary. The longer she stays on the scene, the more disturbing information Tinka unearths while at the same time being dogged by a strange man in a brown suit who claims he is a policeman, one of Brand’s series sleuths, Inspector Chucky, but whom she suspects to be a fellow journalist.

You could easily get a full house in a game of melodrama bingo as Brand throws in almost every trope for good measure. A remote house which is only accessible by boat because the river is in spate, a desperate bid for freedom in which the heroine dislocates her ankle, a ghostly visitation, the use of drugs to keep Tinka quiet and a captive, a horribly disfigured woman who is kept out of sight and prevented from using a mirror lest she sees the extent of her injuries.

Add to all of this the presence of a serial killer and a mountain precipice which claims at least three victims and a life and death struggle only resolved, at least partially so, by the timely appearance of Chucky and you have more than enough to go on with. After a painfully slow start the book picks up pace to become almost breathless at its conclusion. The mystery is the identity of Amiska and her fate and as we discover more about her we learn of more grisly and disturbing facts.

Brand does a good job in hiding the identity of the mastermind behind all of the events with lots of twists and turns which send the reader’s thoughts in one direction and then another. Perhaps the disappointment is that the solution is not as left field as this reader might have hoped.

There are three leitmotifs running through the story. Tinka is a mouse, being played with by the main three residents of the house, Carlyon, Mrs Love, and Dai Jones, who are personified as cats, although, of course, the Siamese cat rarely plays with its victim before the kill. Love should be like a chocolate box, where the contents are more important then the wrapping and love at first sight is like a rainbow, a moment of brilliance which rapidly fades. And for lovers of ring composition, of whom I am one, the book satisfyingly starts and ends in the offices of Girls Together.

Not the strongest of the Brand books that I have read, it is a bold variation on the usual murder mystery story.

July 27, 2025

Pressure Group Of The Week

Kufis off to the Drunkards Association, who recently staged a peaceful protest through the streets of Accra in Ghana in protest over the rising price of alcoholic beverages, fuelled in part by the unexpected appreciation in value of the national currency, the cedi. The association’s president, Moses Onyah, known as “Dry Bone”, claimed that the increasing cost of alcohol is making it difficult for the average Ghanaian to unwind, especially in challenging economic times.

The association, which seems to eschew the apostrophe, is no joke, claiming to have 6.6 million members across Ghana, its members including casual and regular drinkers as well as vendors. It has recently launched an E-Drink App, enabling members to order alcohol via Facebook or other GPS-enabled systems in a move to reduce alcohol-related accidents by discouraging drunk driving or walking under the influence. In 2021 it declared June 11th as National Drinking Day.

It has now given the government a three week ultimatum to reduce prices.

As their president says, we are not just drunkards…we are responsible citizens who demand fair treatment and affordable beverages.”

July 26, 2025

Spoilsports Of The Week (4)

One of the supposed attractions of an overnight stay at the Lehe Ledu Liangjiang Holiday Hotel in Pengshui in China was its unusual wake-up call service. For an additional charge guests could have one of four red pandas enter their room at the appointed time and clamber on to their bed. Then, according to their mood and perhaps their busy schedule, they would hang around for a while before leaving.

Not anymore. While there is no denying that, photogenically at least, red pandas are rather cute, the Chongqing Forestry Bureau has clamped down on the practice, claiming that it was tantamount to animal abuse as the pandas are sensitive and their stress responses could endanger themselves or the humans.

A fair point and so It is back to the automated wake-up call, I suppose.

July 25, 2025

Murder Of Lydia

Murder of Lydia (1933) by Joan A Cowdroy – 250618

Originally published in 1933 and reissued by Dean Street Press, Cowdroy’s Murder of Lydia brings together her two sleuths, Chief Inspector Gorham of the Yard, and Mr Li Moh, an amateur detective who had spent some time as a detective in San Francisco. Characters of Chinese origin in Golden Age and earlier crime fiction tend to be the baddies with connections to the drug trade and practitioners of the martial arts and so Cowdroy’s decision to break the mould by making Li Moh not only a good guy but an instrument of justice is fascinating as it is bold. My only disappointment is that he plays a rather shadowy role, an intelligent and perceptive Watson to Gorham’s Holmes but, nevertheless, he is more than a stereotype, although her decision to make his diction markedly different is, I feel, a mistake, and has moments of inspiration which move the case along.

Like many a fictional sleuth, Mr Moh, while ostensibly on holiday at Whitesands Bay with his “relatives by marriage”, finds it is more of a busman’s, although he is grateful for any opportunity to escape them. He is imbued with the happy knack of being in the right place at the right time, striking up a friendship with the local bobby, James Bond, rescuing some clothing from a dog, being present when a party visit the local castle and witnessing an odd occurrence where Rosalind Torrington appears to deliberately push her sister Lydia on the stairs, causing her to stumble and Robin Tennant to shout in disapproval Rosalind’s name.

To say that the two sisters have a complex relationship is an understatement. Lydia, the elder, has a habit of stealing her sister’s fiancés and, having received the majority of her aunt’s inheritance, only allows her a small annuity, seemingly spending the rest on clothing, while Rosalind is renowned for a ferocious temper. Both are exceptionally strong swimmers able to deal with the strong currents in the bay and make a habit of bathing in the early morning.

It comes as no surprise that Lydia is found dead slumped over a buoy and the obvious culprit is Rosalind, especially as a wet swimming costume is found in her room. Although the evidence against her is circumstantial, the coroner’s court finds she is the culprit and she is arrested for murder. Gorham, who is brought into the case because the Chief Constable’s son, Robin, is engaged to Rosalind and he has had to recuse himself, does not agree and makes it his mission to find out what really happened.

As befits a story with a strong natational theme, there are a shoal of red herrings to work his way through, and what I enjoyed about the book is the way that Cowdroy drip feeds into her story little incidents and facts that begin to overturn the initial impressions that the reader has of the two sisters and their characters. How the murder was carried out is reconstructed, Moh having an important input due to his athleticism, requiring a prodigious feat of diving which means that the culprit was a skilled practitioner of the art or had severely injured themselves.

As the alibis are proven, one involving spending the night in question nursing a sick pig, even Gorham is beginning to think that Rosalind will carry the can after all. However, Moh, amongst others, had seen a couple of strangers at the Castle, one with a distinctive physical trait, and when Gorham tracks down Rosalind’s missing cousin, Hervey, that his theory comes together.

It is a case of blackmail, deceit, and a desperate attempt to end an ill-considered marriage and the identity of the culprit comes as no little surprise, although there are hints enough in Lydia’s backstory but ones that are easy enough to miss under the welter of all the other extraneous information that is swirling around in the eddies of the story.

It is a well worked story as well as being an entertaining read that keeps the reader’s attention through all its twists and turns, ending with quite a surprise. It is one that I would thoroughly recommend, but I just wish there had been a bit Moh-re Mr Moh!

July 24, 2025

Bobs, Shingles, And Waves

For the spirited and adventurous woman in the inter-war years one way to show their independence was to wear their hair short. A popular style was the bob cut, which typically fell just below the chin, framing the face. Introduced by the Polish hairdresser, Antoni Cierplikowski, in 1909 and inspired by accounts of Joan of Arc, it symbolized modernity and captured the essence of the Roaring Twenties.

Embraced by the likes of Coco Chanel, Queen Marie of Romania and American film stars such as Clara Bow and Louise Brooks, it soon became the dominant hairstyle. It also had a practical advantage over earlier fashions for long hair as it was easier to maintain. However, as early as 1922 the fashion correspondent of The Times was intimating that bobbed hair was passé and by the middle of the decade it had been replaced in popularity by shingled hair.

Shingling was an even shorter style and was a very involved process to achieve the required effect. It required each curl to be separated and smoothed and then the application of a styling product such as curl cream, gel, or leave-in conditioner to each curl to create a bouncy, defined coil. The process helped smooth the cuticle, creating ultimate definition and making the curls last longer.

The complexity of the process meant that the wearer had to undergo frequent and extensive treatments in a beauty salon which offered other services such as manicures to keep the customer amused and entertained. The wearing of shingled hair was also a class statement. Whereas the bob was achievable for working-class women, shingled hair denoted someone who had the time and money to devote to its maintenance.

The correct response to bobbed and shingled hair vexed employers as a newspaper article from November 1924 reveals. “Recently Lyons and Company, the London caterers, decided that their tea shop girls, who had previously not been allowed to show their hair, may do as they like now”. However, “Romford Board of Guardians decided that no member of the nursing staff will be allowed to bob or shingle, and that women now having short hair must allow it to grow”. The decision was by no means unanimous, one female board member arguing that short hair was hygienic and that no one wanted hair in their food while others wondered whether the board proposed to ban face power and high heels.

Fashions, though, wax and wane and by the 1930s hair was being worn longer again and waved, the Marcel wave being particularly popular. Waves were produced using electric waving irons, which allowed the temperature of the iron to be regulated, and a comb. Initially, the irons only came in one of four sizes – A, B, C, or D – but in 1933 an adjustable iron was developed.

The application of heated tongs could fill the customer with dread, as E M Delafield memorably records in The Provincial Lady Goes Further (1932). “Undergo permanent wave, with customary interludes of feeling that nothing on earth can be worth it, and eventual conviction that it was. The hairdresser (…) assures me that I shall not be left alone whilst the heating is on, and adds gravely that no client ever is left alone at that stage – which has a sinister sound, and terrifies me. However, I emerge safely, and my head is also declared to have come up beautifully – which it has”.

You have to suffer for your fashion, seemingly. Travelling up from rural Devon to have her hair waved, the Provincial Lady sees it as a London thing which will mark out as a fashionista back home. As someone who reads a lot of literature from the period and come across bobs, shingles, and waves it is nice to clarify one’s understanding of the various fashions.

July 23, 2025

Dover One

A review of Dover One by Joyce Porter – 250616

I first came across Detective Chief Inspector Wilfred Dover of the Yard in one of Martin Edwards’ anthologies for the British Library Crime Classics series, Lessons in Crime. It was one of the weaker stories, not least because the sleuth was an unspeakably vile, irascible, lazy slob with no redeeming features. Nevertheless, I was sufficiently intrigued by Porter’s creation to wonder whether in a full-length novel the character would become more rounded. Dover One, originally published in 1964, is the first in a series of eleven books in which he features.

The answer is a resounding no and if anything he is an even more unappealing character, six foot two tall “draped in seventeen and a quarter stone of flabby flesh”, with underarm dandruff, a Hitler moustache, and a bowler rammed down on his head. His long-suffering colleague, Sergeant MacGregor, has much to put up with as he has to do much of the work while his boss spends much of his time in contemplation aka sleeping. It is no wonder that the Yard are keen to send him to the remotest parts of the country to get him out of their hair.

And so he finds himself despatched to darkest Creeshire to investigate the disappearance of Juliet Rugg, a young woman who in her own right is as unappealing, a nymphomaniac, a single mother with, horror of horrors, a young child of mixed race, and prone to the odd spot of blackmail. Despite her size, sixteen stones, there is no sign of a body and even if he exerted a scintilla of effort Dover would have found himself with precious little to go on.

In a sense the plot is a variation of a locked room mystery as the disappearance of Juliet occurred in what is effectively a gated community, run with a rod of iron by Sergeant Major Bondy. Mind you, he might have got to the solution a lot quicker had he listened to Amy Freel, a well-meaning busybody with a passion for detective fiction, whom Dover cavalierly dismisses as an interfering amateur without whose input seasoned professionals from the Yard can do without.

It is also very much of a police procedural but eventually even Dover gets on to the right track, vital clues being green nail varnish, a message given by Simkins to a registered drug addict, Boris Bogolepov, and the recently oiled wheels of a wheelchair. There is even a hint of cannibalism and experience in the lifestyles of indigenous people in the tropics helps to explain how the murder was committed.

There are some delightful characters, Porter cleverly pulling the rug from under all of our feet when she introduced Colonel Bing, and the book is funny with a number of memorable comedic episodes, especially involving Dover’s fraught relationship with the Colonel’s dog, Peregrine. Dover is not one to play by the tried and tested rules of engagement with suspects and the level of physical violence not only extracts the confession he needs but leads to a messy, comic, and violent denouement. There is a dark strain of humour running through the book and it is easy to see why the stories found success in the 1960s when adapted for television.

That said, for the modern reader it is a plentiful source for a game of unpolitically correct bingo. It is racist, sexist, fat shaming, antisemitic, homophobic, xenophobic amongst a multitude of other sins. It comes from an era when we were happy to laugh with Alf Garnett rather than at him and to enjoy the company of The Black and White Minstrels on a Saturday evening. It is very much a creature of its time.

There are so many reasons why I should hate this book but there is something strangely fascinating about a character that is truly obnoxious and a story that challenges all our current preconceptions. Perhaps it taps into the zeitgeist perfectly.

July 22, 2025

Caffeine, Decaffeinated Or Caffeine-Free?

My rule of thumb is coffee before one o’clock and tea after, a self-imposed regime to reduce the impact of caffeine on my body. Caffeine blocks a chemical in the brain called adenosine which normally makes you feel sleepy, giving the pleasant high of being alert and energetic. Of course, it is all delusional as tea also contains caffeine, the leaves containing more caffeine by weight than coffee beans. However, because coffee is brewed at higher temperatures and with a higher concentration of solids, there is more caffeine in the drink.

Typically, black tea has more caffeine than other types of tea. After harvesting black tea leaves undergo full oxidation, a process that darkens the leaves and enhances their flavour profile. It also breaks down cellular structures in the leaves, making caffeine more soluble and easier to extract during brewing. Often brewed at higher temperatures and for longer durations further increasing caffeine extraction in black tea compared with less oxidized teas like green or white tea.

Other factors influencing caffeine levels in black tea include leaf size (smaller leaves release caffeine faster), and growing conditions such as altitude and soil composition. While black tea generally contains more caffeine, variations can occur based on specific blends, brewing methods, and environmental factors.

Other factors that influence the caffeine level of teas include the physical size and processing that tea leaves have undergone. Broken or crushed leaves, which are typically used in tea bags, have a larger surface area exposed to water, leading to faster and higher caffeine extraction compared to whole leaves.

Obviously, the amount of tea used can affect the caffeine levels as does brewing time. Longer brewing times extract more caffeine, with up to 92% extracted within ten minutes, although they also increade the bitterness of the drink. Water temperature also has an effect, brewing at almost boiling point can extract almost all the available caffeine in a matter of minutes whereas cooler water slows the process.

Decaffeinated tea is tea which has caffeine present in its leaves but which has been subjected to a process that removes as much caffeine as possible. Manufacturers typically do this by using one of four solvents, methylene chloride, ethyl acetate, carbon dioxide, or water. The important point to remember, though, that irrespective of the process used, the leaves will still have traces of caffeine in them.

Caffeine-free tea is another kettle of boiling water as teas such as mint, rooibos, chamomile, hibiscus, and ginger tea are made from herbs and flowers which are caffeine-free and do not have to go through a decaffeination process. Technically, they are tisanes and not teas at all.

So if you want to drink tea, whether caffeinated or decaffeinated, you will be ingesting some level of caffeine, otherwise you should drink herbal teas which are caffeine-free but not teas.

All clear?