Martin Fone's Blog, page 10

July 21, 2025

Death And The Dutiful Daughter

A review of Death and the Dutiful Daughter by Anne Morice – 250613

As someone who normally reads detective fiction from the inter war years or early post Second World War it pulls one up short to see a reference to the M4 and cars travelling at ninety miles per hour. But Anne Morice’s books are firmly planted in the 1970s, this, the fifth in her series featuring the sometime actress and amateur sleuth, Tessa Crichton, originally published in 1973 and reissued by Dean Street Press. Light, a quick read, laced with acerbic wit, sharp social observations and delicious turns of phrase, what might be missing in the intricacies of plotting is more than made up for by the sense of luxuriating in a hot, bubbly and heavenly scented bath.

The dutiful daughter in question is Betsy Craig, whose mother is the famous opera singer, Maud Stirling, who is elderly and in poor health. Betsy acts as housekeeper and while the invalid is attended to be two nurses operating twelve hour shifts, she takes upon herself to see to her every needs, allowing the night nurse, Maureen, to sleep undisturbed. Betsy dies unexpectedly, but given her age and health it is not too much of a shock, although there seems to be something odd with a thermos of milk which she drank just before her death, which Albert, the manservant was quick to wash out, and which was found under her bed.

The next shock is Betsy’s will which she amended into true murder mystery fashion just before her death. Instead of splitting her estate between her two daughters, Betsy and Margot, a daughter from her second marriage, she effectively cuts Margot out, giving the majority of her estate to Betsy. Betsy, though, does not have long to enjoy her good fortune as tragedy continues to bedevil the Rectory, firstly when Maud’s granddaughter-in-law, Sophie, falls to her death from a rickety balcony – it transpires that someone had sawn through the pillars – and then Betsy herself is killed, electrocuted in her bath.

Add into the mix the disappearance of some of some tape recordings and Maud’s jewellery, including the gem bequeathed by her to Tessa Crichton, who knows the family and uses the presence of her husband, Robin Price of the Yard, in the area as a pretext to attend Maud’s funeral, renew her friendship with Betsy, and, in loose association with her cousin, Toby Crichton, snoop around, you have the ingredients of an intriguing mystery.

Tessa wonders whether there is anything fishy about Maud’s death, who sought to benefit from the three deaths and whether there was any significance in the order in which they occurred or whether one or more could be considered collateral damage. Why was the nurse, Maureen, seemingly not on the scene at the time of Maud’s death and what was the significance of Margot’s hat found under the crumpled body of Sophie? And what of the strange behaviour of Albert and the disappearance of his wife?

There are a number of suspects who could plausibly have committed some or all of the murders, each of which could be done in absentia, but the familiar motives of avarice and thwarted love come to the surface and some helpful information provided by Maud’s masseuse and a garrulous taxi driver, Owen, – is there any other sort? – puts Tessa on the right trail and earns her another opportunity to impress the police with her perceptiveness and powers of deduction. Always suspect the least obvious character.

The plot might be a tad implausible but the book is great fun and highly entertaining. Good stuff.

July 20, 2025

The Perils Of Dog-Walking

There are around 8.5 million dogs in the UK and as any owner knows they need regular exercise. Of course, this has added benefits because it forces owners to engage in some physical exercise themselves, but at what cost?

Some research published recently in the journal, Injury Prevention, conducted by experts from Raigmore Hospital and Singapore’s Sengkang Hospital, reviewed around 500,000 dog-walking-related injuries. Three-quarters of the injuries were sustained by women and 31% of the cases were among the over-65s. While finger fractures were the most frequently reported injury, from a cost perspective distal radius fractures, wrist fractures, had the most economic impact.

Indeed, the researchers estimated that the cost of dog-walking-related wrist injuries to the NHS in the UK was in excess of £23 million a year, a figure that would rise significantly if loss of productivity arising from absence from work was taken into consideration.

The report recommended that preventative measures, such as safer leash practices and public safety guidance, should be implemented as well as teaching “optimal dog-walking practices” and proper dog training to minimize the chances of Fido hurting its owner.

July 19, 2025

Compendium Of Body Shapes

It is a truth universally acknowledged that human beings come in all shapes and sizes. One site that celebrates this diversity is The Photographic Height/Weight Chart which is trying to compile a photographic record of people of every height and weight combination.

The weight range runs along the x axis and heights run along the y. Members of the public are invited to send in photographs – there is also a video version – stating their particular dimensions and they are fitted into the appropriate slot, making it easier to visualize height/weight combinations.

There is something charmingly old school or retro about this site which also calculates Body Mass Index for each combination and Body Surface Area. The latter, calculated by taking the square root of the result of height in centimetres multiplied by weight in kilograms divided by 3600, ranges for adults from anywhere between 1.3 square metres and three.

Just what the internet was designed for!

July 18, 2025

The Mystery At Stowe

A review of The Mystery at Stowe by Vernon Loder – 250611

Originally published in 1928 The Mystery at Stowe is the first of twenty-two mystery novels written by Vernon Loder, one of the noms de plume of the prolific John Vahey, and is a classic country house murder with quite a pleasing twist at the end.

The story takes us to the country pile of Mr Barley who has, as was the custom at the time, a full complement of guests. The principal three for the purposes of the plot are Elaine Gurdon, an intrepid adventurer and traveller, who is planning her next expedition, Ned Tollard, who is funding the expedition, and his wife, Margery, who not only is the polar opposite of Elaine, a nervous, wan thing, but also is insanely jealous of the time that Ned spends closeted with Elaine over the finer points of the expedition. The tension is apparent to the other house guests and one day, after atrip out, Margery retires to her room with a “headache” and Ned drives off, claiming urgent business.

During the early hours of the following morning, Elaine hears a noise, enters Margery’s room and finds her dying. There is a sharp dart-like object and it is quite obvious that she had been poisoned by a dart. The police’s prime suspect is Elaine because not only is she proficient with a blowpipe – she had given a demonstration on the lawn a little earlier – and had sold one complete with a quiver full of darts to Mr Barley who had hung them up on the wall as an exhibit. Needless to say, there is a dart missing from the quiver.

A mystery with only one suspect would hardly be a mystery and so Tollard also enters into the reckoning, either having sneaked back to commit the murder or involved a third party to commit the dastardly deed. Conveniently, Margery’s bedroom window was open, she or at least a woman dressed in a red dressing gown had appeared at the window just at the time that the gamekeeper was wandering the grounds. Surprisingly, Elaine seems oblivious to the danger that she is in and Tollard seems reluctant to let anyone help him.

As the police, led by Superintendent Fisher, are girding their loins to arrest Elaine, Jim Carton arrives on the scene. He is an interesting character who not only spent several years in Africa in a role as Assistant District Commissioner that involved some elements of detective work but also carries a flame for Elaine. His basic premise for his enquiries is that his beloved Elaine could not possibly have committed murder and sets about not only to discover the truth but to play for time by throwing some enormous curve balls in the direction of the police.

Carton initially demonstrates his credibility as a sleuth by discovering a fact about the gamekeeper that had eluded the police, that he is red colour blind. He then persuades the somewhat sceptical Fisher to spend time investigating the blowpipe and whether someone on the outside, the gamekeeper for instance, could have shot the dart using an air pistol. Meanwhile despite the unnecessary obstructions imposed by Tollard, Carton concentrates his efforts on examining a stepladder that had been used to remove a dart from the quiver and finds a vital and very telling clue.

This is enough for both Carton and Fisher to realise what had really happened. It is both a surprising finale and, really, one full of pathos. The ending has divided opinion amongst readers, some viewing it as a bit of a cop out while others, this one included, see it as a logical, if somewhat melodramatic, conclusion to the psychological picture that Loder has painted of the prime suspects.

Either way, it was an enjoyable book. Loder has an easy style, there is little in the way of pretensions to producing a work of literature, just a thoroughly good story that the reader can immerse themselves for a few hours. Often that is all you want.

July 17, 2025

Planetary Seasons

Earth has four seasons of roughly similar length, the seasons below the equator being the opposite of those above. This is because it rotates at an angle of 23.5 degrees, so when Earth is on one side of the sun, the Northern Hemisphere is pointing towards the sun and the Southern is facing away. However, the seasons are more extreme in the southern hemisphere because the Earth’s orbit around the Sun is not perfectly circular, it is closer to the Sun in southern hemisphere summer than in southern hemisphere winter. It is more circular than the orbits of other planets, resulting in seasons that stay mainly consistent wherever you are.

Mars has a similar rotational tilt to Earth, 25.19 degrees, but that small difference coupled with its elliptical orbit means that there is a significant, one may say astronomical, seasonal variation. Spring is the longest in Mars’ northern hemisphere, lasting seven months, and winter the shortest a four. Its winters can be very cold, reaching temperatures of -153 Celsius, compared with the lowest ever recorded in Antarctica of -89.2C, cold enough for carbon dioxide to condense, forming clouds and snow around its pole.

It was not always thus. A paper published in Earth and Planetary Science Letters in 2018 suggests that Mars’ tilt has varied from between ten and more than 40 degrees over billions of years. This has led to extreme fluctuations in the planet’s yearly cycle and it is merely a random chance that its tilt is currently almost identical to that of Earth. The stability of Earth’s tilt, though, has meant a fairly consistent yearly cycle throughout the planet’s existence.

The second closest planet to the Sun in our solar system and of a similar size and weight to Earth, Venus is the hottest planet with temperatures reaching up to 462 degrees Celsius. This is because its atmosphere traps UV radiation from the Sun’s rays, creating a huge greenhouse effect. With a rotational tilt of just 3.39 degrees, there are virtually no seasonal variations, a Venusian spring being almost indistinguishable from an autumn. Its slow rotation means that a day is the equivalent of 243 Earth days.

Jupiter has the shortest day in the solar system, taking just 9.9 hours to rotate, but its elliptical orbit around the Sun takes the equivalent of 12 Earth years. Its rotational tilt is just 3 degrees, meaning that its seasonal variations are not marked, although its temperatures can range from 24,000 degrees Celsius near its core to -145C towards the exosphere.

Mercury has virtually no tilt, just 0.03 degrees, but a highly elliptic orbit, creating an approximation of summer and winter as the planet slingshots away from the Sun. At its closest to the Sun, its surface can reach temperatures of 427°C during the day, plummeting to -127°C when it is furthest away. It also has a bizarre rotation, spinning three times (every 53 Earth days) over two rotations around the Sun, making it impossible to tell when one season begins and one ends.

Pluto, on the other hand, has a tilt of 119.5 degrees, which means that its north pole is almost upside down compared to Earth’s, so one half of the planet will experience months of the midnight sun and then months of darkness. However its seasons can last over a century, as it takes 248 Earth years to orbit round the Sun.

Uranus has four seasons similar to Earth – but the length and intensity of its seasons are far more extreme. For nearly a quarter of each Uranian year (84 Earth years), the Sun shines directly over each pole, which makes for a long hot summer lasting twenty-one years while the other half of the planet is plunged into a dark winter lasting just as long.

Neptune has an 165-year long orbit and 40-year-long winters, while Saturn with a larger tilt than Earth (27 degrees), a more circular orbit than Mars and a gas giant like Jupiter, has pretty consistent seasons lasting seven years.

July 16, 2025

Murder Is Easy

A review of Murder is Easy by Agatha Christie – 250609

Sometimes I read a Christie novel and wonder what all the fuss was about and occasionally I find one that hits the spot. Murder is Easy, which also goes by the alternative title of Easy to Kill, originally published in 1939, falls firmly into the latter category. It is a masterpiece in misdirection and wrongfooting the reader.

We are firmly in Christie territory with a charming English village populated by retired colonels, spinsters, an antique dealer with a fascination of the occult, and a self-made publisher who has pulled himself up by his bootstraps and returned to his home village as the self-proclaimed squire. However, beneath the picture postcard surface something sinister is lurking, a village that is both “so smiling and peaceful – so innocent – and all the time the crazy streak of murder running through it”.

By the time the book opens there have already been a spate of deaths, all of which look like accidents – the landlord of the Seven Stars toppling into the river in his cups, Mrs Horton from gastric pains, Amy Gibbs who mistook hat paint for a medicine, and a mischievous youth, Tommy Pierce, who falls to his death from a ladder – but Miss Pinkerton fears that not only is there more to these accidents than meets the eye but that at least one other villager, Dr Humbleby, is in grave danger and she is going to Scotland Yard to enlist their help.

Her travelling companion, to whom she opens her heart, is Luke Fitzwilliam, a retired policeman who has returned from duty from the Mayang Strait. He treats the information as the ramblings of an old, confused woman but he is then shocked to read that not only had Miss Pinkerton been killed, run over on her way to the Yard, but also that Dr Humbleby had died from septicaemia. Intrigued he decides to go down to the village and act as an amateur sleuth to find out what is behind all these deaths.

Luke is assisted by Bridget Conway, a cousin of one of Luke’s friends and the fiancé of Lord Whitfield, the self-made businessman. During his discussion with Miss Pinkerton she gave him some valuable clues as to the identity of the culprit, although he chooses to misinterpret their meaning. As a result much of his investigations are little more than deviations on a wild goose chase. By a process of elimination he convinces himself and us that the murderer can only be one certain person, a feeling reinforced by the death of Rivers, Lord Whitfield’s chauffeur, who is struck by a stone pineapple which falls of a gate post.

Bridget, however, cannot accept Luke’s conclusions as they do not fit the psychological make-up of the killer. Her suspicions are focused on an altogether different and surprising suspect, confirmed when she finds herself in a life-and-death struggle to prevent herself from being the seventh victim with the culprit, only for Luke to arrive in the nick of time to save her.

Revenge is a dish best served cold, they say, and what we have here is an elaborate plot to frame someone for a slight delivered many years before. It almost succeeds but Miss Pinkerton’s clue about a look that seems almost manic is telling.

There is a distinct feel of eugenic theory in the discussion between Luke and Dr Thomas as to whether some people to deserve to die and Lord Whitfield’s belief that he is somehow “an instrument of a higher power” who delivers death to those who cross him. Given the book’s publication date and what was happening in Nazi Germany at the time, this strikes quite a disturbing chord.

Taxonomically, this is the fourth in the Superintendent Battle series, if you include Cards on the Table, which is also a Poirot story, but, in truth, Battle only features in the last two chapters. He does have the sense to consider Luke’s evidence afresh and save the Yard the embarrassment of arresting the wrong person.

A quick and light read with much to admire, this is one of Christie’s best.

July 15, 2025

Manila Envelopes

In the days before emails and PDF attachments and when I was working for an insurance company – yes, I know, we are talking about the last century – documents of any import were sent around the building and externally in heavy tan-coloured envelopes known as Manila envelopes. They were so durable that even when it was not fashionable to recycle, they were continually reused until they were almost falling apart. So imbued into the office culture were they that I never really considered why they were so distinctive and how they got their name.

In the 1830s when American stationery companies were experiencing supply shortages in the materials usually used to make paper pulp, cotton and linen rags, and began to turn their attention to Manila rope. Used on ships, it was made from Manila hemp, an extremely strong and durable material derived from the abacá or Manila plant found in the Philippines. It takes its name from the country’s capital and produced high-tensile material which was used for everything from shirt collars to ships’ sails.

The early Manila folders were much heavier than their modern counterparts and were more like cardboard than paper. One sheet could be folded into two to make a folder and as it was waterproof, it was ideal for transporting important documentation. As the plant fibres that the paper was made from were yellowish-brown in colour, it had a distinctive golden hue.

Even when supplies of the more traditional sources of paper manufacturing were restored, manila was still used as manila paper could be made from old frayed ropes, cheap and an early form of recycling. It took almost sixty years, though, for the term Manila envelope to catch on, the Oxford English Dictionary citing the first instance in an advert from a printer, Barnum and Co, in 1889 claiming to “make a specialty of large Manilla…envelopes”.

Sitting on such a useful and valuable natural commodity should have been a welcome boost to the Filipino economy but they became the victims of imperialism, the American government taking over the control of the exports after they had colonized the territory.

With wood pulp becoming more readily available and far less expensive than manila, manila was phased out of paper manufacturing over time. Nevertheless, such was its reputation for durability that paper manufacturers continued to make a yellow, unbleached paper to make large envelopes, which carried the “Manila” designation, even though they were not made from the fibres of the abacá. They are also nowhere near as durable as the originals.

So, now we know!

July 14, 2025

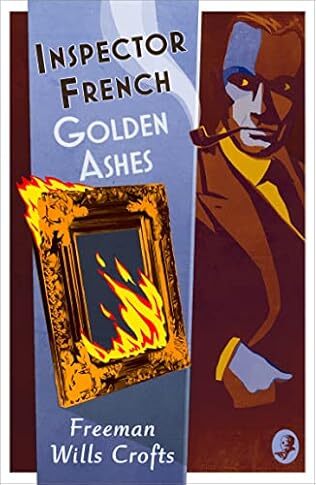

Golden Ashes

A review of Golden Ashes by Freeman Wills Crofts – 250607

I do not think I am being unduly unfair if I describe the twentieth novel in Freeman Wills Crofts’ long-running Inspector French series, originally published in 1940, as distinctly one-paced. In truth, you do not pick up one of his books for a thrill a minute but rather a well-plotted ingenious murder mystery and a painstaking investigation in which French, after many wrong turns and dead ends, finally pieces together the jigsaw and comes up with motive, method, and culprit. Most of those ingredients are to be found here although it reads more like an inverted mystery as we have a pretty shrewd suspicion whodunit.

This is another story where French hops across the channel and seeks the collaboration of the Sûreté in the form of Inspector Dieulot several times as he tries to crack the alibis of his prime suspects, finding an ingenious passport stamping fraud along the way, much to the embarrassment of the French border officials, and also allows Crofts to compare and contrast the thoroughness and determination of the British police compared with their foreign counterparts.

The plot is simple enough. Geoffrey Buller, an office worker, unexpectedly inherits a title and a country pile, Forde Manor, which houses a collection of paintings, some of which are priceless masterpieces. Sadly though, death duties and Buller’s predecessor’s mismanagement has depleted the cash reserves and the would-be lord of the manor has barely two halfpennies to rub together. However, he has a plan which involves having the paintings and the house revalued for insurance purposes, putting Forde Manor up for sale – no one, though, wants to take on such a ruinous pile – and, controversially and to the consternation of his housekeeper, Betty Stanton, having some of the paintings “cleaned”. They come back somewhat brighter and distinctly odder.

Buller, who is a social failure and whiles away the lonely hours working away in his workshop – a telling point – decides then to shut the house up and go abroad. While he is away, the house goes up in flames along with the collection of paintings. It was lucky he had sorted out the insurance, or was it?

The fly in the ointment is an art expert, Charles Barke, who has decided views about cleaning paintings and had been invited down at Betty’s prompting to view the collection. Unbeknown to Buller, Barke had made a second visit to view the cleaned paintings the day before the fire. Buller’s discovery of the second visit coincides with Barke’s disappearance, having seemingly checked into a hotel in Paris and then vanished into thin air.

The combination of the possibility of insurance fraud and the disappearance of Barke which might or might not be murder allows French to join forces with a former police colleague and now insurance assessor, Thomas Shaw of the Thames and Tyne Insurance Company. Between them they find the cause of the fire, a rather ingenious device which was triggered by an innocent party. It was good to see, in inimitable Crofts’ style, Molesworth’s Pocket-Book of Engineering Formulae put to good use to calculate the amount of material and equipment was needed to produce the required result.

The fate of Barke is a tougher nut to crack, the resolution of which would probably have been swifter had Betty Stanton not, for some inexplicable reason, held on to some vital information and, despite all the cross-Channel jaunts, lies closer to home. All the clues are there for the reader to piece together the plot as Crofts challenges us to do just before the end, but in the end all he has done is produce a thoroughly readable book which is as exciting as watching paint dry.

July 13, 2025

The Spirit Of Wowbagger

In Douglas Adams’ Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy Bowerick Wowbagger the Infinitely Prolonged became immortal after an accident involving a few rubber bands and a particle accelerator. The rub was that he had lived so long that he had run out of things to do so to keep himself amused he decided to insult everyone in the entire universe in alphabetical order. He is only put out of his misery in the sixth book when Thor hit him so hard that he lost his immortality.

Bowerick Wowbagger might have been grateful for a database that The Population Project, a non-profit organization, is compiling. Its seemingly impossible challenge is to record the full name and place and date of birth of every living human on the planet. At the time of writing they have recorded 695,027,128 of us, around 8.49% of the world’s total population. Unsurprisingly, this has never been attempted before but the driving force behind the project is to give every person an identity.

The challenges are enormous with around 300,000 babies born a day, not all births are registered, and data sources needing to be checked and often erroneous. Undaunted, though, they carry on.

There is something mildly disturbing about the project, smacking a little of Big Brother, although I am sure it is done with the best of intentions. I could not resist checking to see whether I have made it on to the database and, lo and behold, I have. Curiously, I share my name with only one other person, someone considerably younger than me, from Manchester.

The spirit of Wowbagger lives on

July 12, 2025

Pencil Of The Week

In May 2017, a sudden and violent windstorm swept through the Lakes rgions of Minneapolis blowing over many massive trees including an 180-year-old bur oak at the Higgins’ family home at 2217, East Lake of the Isles Parkway. All that was left of it was a large standing stump known as a snag. Instead of chopping it up into firewood, it was decided that something special should be done with the remains of the tree to extend its life.

Minneapolis has made a thing of large, prominent sculptures featuring everyday objects. There was already a statue of a half-peeled banana sited in the garden of a private residence in the lakes area. Very quickly the Higgins thought that the shape leant itself to the creation of a pencil and so spent several months in cahoots with chainsaw artist, Curtis Ingvoldstad, to come up with the perfect design complete with yellow shaft and pink rubber.

Standing twenty feet tall and with a 32-inch diameter it was carved in 2022 in about a month and a half. It has proved a hit with the local community becoming the focal point for Halloween celebrations and festive light displays. However, there was one problem; over the course of a year the rain, snow, and wind would blunt the once sharp point.

So every year on the first Saturday of June, the Higgins family host a pencil sharpening ceremony which is attended by about 1,000 people, some of whom dress as pencils or rubbers. Ingvolstad brings a custom-made sharpener which is carried up to the point on scaffolding and between three and ten inches are removed. Eventually, of course, the sculpture will end up just a stub but, hey, that is how most pencils end up.

Creative recycling at its best.