Martin Fone's Blog, page 7

August 20, 2025

Death Makes A Prophet

A review of Death Makes a Prophet by John Bude – 250712

The eleventh in John Bude’s William Meredith series, originally published in 1947 and reissued as part of the British Library Crime Classics series, Death Makes a Prophet is very much a book of two halves. It should appeal to those of us who like their murder laced with humour and an intriguing puzzle that resolves itself neatly at the end, even if there is a little legerdemain to make it all work.

Eustace Mildmann is the High Prophet of the Church of the Children of Osiris, known as Cooism, based in the Garden City of Welworth, a town with a growing reputation for eccentricity. Any hopes that he entertained that his church would bring him spiritual peace are sadly frustrated as it becomes the centre of a power struggle between the orthodox, Mildmann, and the more progressives, whose cause is enthusiastically pursued by the moneybags behind the cult, Mrs Hagge-Smith, and the eccentrically dressed, ambitious and somewhat unlikeable Peta Penpeti. Penpeti manoeuvres himself to be appointed Prophet-in-Waiting, a position which commands a stipend of £500 per annum, but clearly has his eyes on the major prize, appointment as High Priest with its £5,000 a year salary.

Penpeti seems to be tailed by and fearful of someone who goes by the name of Yacob and another shady character, Miss Minnybell, has him in her sights. On discovering Hansford Boot’s dark secret – he is one of the six of Cooism’s Inmost Priests – and to ease his difficulties with Yacob Penpeti resorts to blackmail, subverting one of Mildmann’s most fervent supporters. Penpeti’s path to the top is made even easier when he discovers some letters that Mildmann had sent to Penelope Parker. Add to all of this the fact that Mildmann’s son, Terence, is increasingly resentful of the tight rein that his father keeps him on. There are ingredients enough for murder most foul.

Bude, though, is in no rush to bring the affairs of Cooism to a crescendo, rather enjoying himself in satirizing British cults, developing the characters of his protagonists and examining the rivers of ambition and jealousy that course through their veins. It is only at around the halfway point when the action has moved away from Welworth to Old Cowdene, the estate of Mrs Hagge-Smith and the venue of the Cooist summer camp, that there is death, but not just one. The bodies of Penelope Parker and Eustace Mildmann are found, the latter disguised as Penpeti, both having ingested poison that was found in Parker’s room. The curious thing, though, is that Mildmann died sometime after Parker, although the poison should have killed them both at the same time, suggesting that he poisoned her and then committed suicide.

There is clearly something very dangerous about going around dressed as Penpeti as Mildmann’s chauffeur, Sidney Arkwright, had been shot at and wounded earlier while donning a Penpeti-like costume for a fancy dress ball and now Mildmann has died. It is a tricky case for Inspector Meredith of the Yard to investigate. He recognizes that Mildmann did not commit suicide but the obvious culprit, Penpeti, has a cast-iron alibi.

I could not help feeling that Meredith was a bit slow on unravelling the implications of the crime, failing to spot until later the significance of the attack on Arkwright and that the position of High Prophet commanded a significant salary. He is helped enormously when someone comes out of left field and provides some very useful information and when Boot, immediately before turning the gun on himself, kills someone he believes to be Penpeti. The manner by which the alibi is established seems to work, although it will offend the detective fiction purists, and I enjoyed the manner in which Mildmann was forced to ingest the poison. The glaring loose end was the role of Miss Minnybell.

Meredith might not have been on top form but this was a very enjoyable book, funny and the interest never waned, even if the culprit was obvious, because of the challenges that the sleuth had in bringing all the pieces together to make a convincing case.

August 19, 2025

A Taste Of Vanilla

Four hundred miles east of Madagascar lies the island of Réunion which was uninhabited when the Portuguese first set foot on it in the early 16th century. Claimed by the French in 1642 its dense forests were soon cleared to make way for coffee and sugar plantations, worked initially by enslaved captives and then indentured Indian and Chinese workers. By the early 19th century 70% of the island’s population was made up of enslaved people, one of whom was Edmond, born in 1829, and living on a small plantation, Bellevue, above the town of Suzanne on the north coast.

Vanilla, a member of the orchid family, an evergreen vine indigenous to the tropical forests, which relies on the native bees to fertilise its big, blooming white flowers to create seedpods. The sensational taste of vanilla extracted from the seedpods took Europe by storm once it was introduced to the continent from the Spanish colonies in the new world. Particular favourites were a cold cocoa drink flavoured with vanilla, which the Aztecs called chocolati, and a vanilla-flavoured frozen custard, introduced to France by Catherine de Medici, which we would recognize as ice cream.

Keen to break the Spanish stranglehold over vanilla supply, the French planted vanilla in many of the tropical outposts of their empire, including Réunion, but while they often produced beautiful flowers, as was the case at Bellevue, the absence of natural pollinators meant that all attempts to produce beans failed. That is until 1841 when the by now 12-year-old Edmond made a chance discovery on the plantation of his master, Bellier-Beaumont.

Edmond peeled back the lip of the flower of a vanilla orchid and using a needle or a slither of wood nudged back the rostellum, the membrane separating the male anther from the female stigma, and pressed the two parts together. Several months later, Bellier-Beaumont wrote “walking with my faithful companion, I noticed on the only vanilla plant I still had, a well tied bean”, where the flower had been. “I was astonished and told him so. He said it was he who had pollinated the flower.”

Two or three days later he found another bean on the vine and got Edmond to show him how he had pollinated the plant. Today, the vast majority of the world’s commercially cultivated vanilla plants are hand-pollinated using le geste d’Edmond, as it is known in Réunion, a skilled grower able to pollinate around 1,500 flowers in a day. The process has yet to be mechanized and because it is so labour intensive it means that of the spices only saffron is more expensive than vanilla.

Edmond’s discovery was just what the French were looking for and it was quickly adopted amongst growers on Réunion. Then two growers, Ernest Loupy and David de Floris, discovered that they could accelerate the processing of fresh green vanilla beans by scalding them in hot water to prevent them from ripening further before drying rather than just leaving them out in the sun. Within 25 years Réunion had become the global leader in vanilla production.

August 18, 2025

Death Has No Tongue

A review of Death Has No Tongue by Joan Cowdroy – 250708

The third and final book in Joan Cowdroy’s Mr Moh series, originally published in 1938 and reissued by Dean Street Press, is on the face of it a simple enough and fairly conventional murder mystery. A spinster, Ellen Shields, who has a habit of collecting information and, therefore, knows too much, is murdered and is found in the garden of Lewis Hardwicke just as he returns home from abroad unexpectedly.

There are a number of peculiar features to the murder, Ellie’s body having been stripped save for the man’s jacket in which she has been draped, her beret with a curious cut and its feather missing found in the garage of the Hubberds, a house in which she is employed in a domestic capacity, and he disappearance and then subsequent injury to Miss Hyde’s dog, another occupant of the small row of houses in a lane in the village of Finnet. And shortly before, there had been the shocking vandalism of Miss Hyde’s garden next door to where the body is found, an act so senseless that it has outraged Mr Moh, working there as a gardener, to such an extent that he persuades his friend and host Inspector Gorham of the Yard to investigate.

There are a number of credible suspects with alibis resembling colanders and enough evidence, circumstantial or otherwise, for the two sleuths to get their teeth into, Gorham doing most of the legwork while Li Moh maintains an inscrutably discreet presence, observing and using his local knowledge to good effect. At some personal cost to his good looks he succeeds at the death to prevent a second murder and allow Gorham to get his hands on the culprit, a chain of events precipitated by an advert placed in the newspapers by the Inspector containing a passage in Chinese, presumably Mandarin, faithfully translated by Moh.

There is more than a little whiff of the Orient in this tale with several of the characters, Moh aside, who have spent time out there and are familiar with the language. The message was intended to advise one suspect that they were no longer in danger of arrest but Gorham had not reckoned on another being au fait with the language, tipping the real culprit the wink and almost ruining Gorham’s plans.

On the other hand this is a tale of two women who are trapped by circumstances. Ellie Shields is not particularly liked. She has a strong moral code, fuelled by her Christian beliefs, a collector of improving verses and maxims. She is clumsy and inefficient as a home help but is willing and is tolerated by her employers for that and because she is cheap. Working at the Hubberds she is treated like a skivvy but appalled by what she considers the loose morals and shameless behaviour that goes on under the roof, she has collected information enough to be valuable and dangerous to others. Ellie also got her hands on some interesting information during her spell working at the Hyde’s.

Elvie Hyde, too, is trapped, working as a housekeeper and unpaid secretary and literary agent to her brother, Sydney, the renowned writer L V Hyde. However, she is clearly not happy and the shock of Ellie’s murder and a couple of seemingly trivial incidents are enough to decide her to sell the house from under her brother’s feet and move on, although to where she is not quite sure. In the week following the murder, she grows close to another and she finds her path to freedom and happiness through love. For poor Ellie, though, the information she had accumulated did not lead to freedom or happiness but her death at the hands of someone who had much more to lose.

Cowdroy has come up with a fascinating take on a murder mystery that requires the space she grants it to work.

August 17, 2025

Trend Of The Week (6)

These days, it seems, if there is a part of your body you are not happy with there is always someone somewhere who will be only too happy to inject something into it at a price to improve matters. Take the rising trend of what is euphemistically known as “bocox”, fillers injected into the male genitals, primarily to treat erectile dysfunction.

The procedure works by relaxing the muscles in the penile area and allowing for increased blood flow to the area, which allows a patient to obtain and maintain an erection. However the surgery is not without risk, as patients can experience irritation, swelling, priapism (prolonged erection) and infection.

One specialist commented that “there are very few specialist doctors who can perform cosmetic injection procedures on male genitals. It is not a procedure I would ever recommend to a patient, even if you went to a specialist, never mind a back-door pop-up clinic,”

In one particularly horrifying case, a man from the Glasgow area was recently forced to have his penis removed at a hospital in Glasgow after having a ‘vaseline-type substance’ injected into his manhood. A 2015 report in Der Urologe reported on a 43-year-old patient who had injected a petroleum jelly substance himself. The man was described as having “multiple fistulas, paraffinomas and bacterial superinfection” which requied to extensive surgery and penile reconstruction.

Meanwhile The Journal of Sexual Medicine in 2016 cited the case of a 49-year-old man who arrived at an hospital emergency department with skin necrosis after using petroleum injections for numerous years.

You have been warned!

August 16, 2025

Sporting Event Of The Week (34)

It is some time since I cast my eye over one of my favourite sporting competitions, the Wife-Carrying World Championships. Held annually in Sonkajärvi in Finland, it is run over a 253.5 metre course complete with a mix of land and water-based obstacles, the objective being for the nominated “male” to carry their “wife”, no marriage is necessary, as quickly as possible.

Competitors can choose their own style, whether it be the piggyback, the shoulder-ride, the Fireman’s Carry where ‘wife’ is carried across or over the shoulders, or the Estonian carry, where the ‘wife’ hangs upside-down on the carrier’s back, with their legs over the carrier’s shoulders and the wife’s head in the ‘danger zone,’ next to the carrier’s posterior.

History was made at this year’s championship held on July 4th and 5th 2025 when for the first time the crown went for the first time to an American couple, who are actually married. Caleb and Justine Roesler completed the course in a new record time of 1 minute and 1.17 seconds, some three and a half seconds faster than the runners up, Vytautas Kirkliauskas and Neringa Kirkliauskiene from Lithuania.

There were over 200 competitors from eighteen countries for the various events, another record, with around 2,000 spectators gathering to watch proceedings. A good time was had by all.

August 15, 2025

Black Agent

A review of Black Agent by Brian Flynn – 250705

The thirty-seventh in Flynn’s Anthony Bathurst series, originally published in 1950 and the second of the latest batch of five reissued by Dean Street Press, takes its title from a quote from Macbeth, “good things of the day begin to droop and drowse/ while night’s black agents to their preys do rouse”. As the title suggests the story concerns itself with mysterious things that happen in the night, notably the disappearance and murder of two young women, Barbara Marsden and Vera Ferris, both wearing the same bright yellow dress.

The story is set in Wavering where one of the social highlights of the year is the New Year Social and Dance, which curiously takes place on the evening of January 24th, from which Barbara disappears without trace. Four weeks later Vera Ferris, who has a bit part in a local am-dram production at the same venue when she wore the same dress, also disappears. Their bodies are found in an old bath tub in a disused sports pavilion.

There are some curious features about the bodies, both faces bear a scar and alongside them are a couple of wooden poles. The bodies have been smeared with the fat from two large bowls of dripping, stolen from the premises of the local butcher, Tidman. Vera, before her murder, had confided to her diary that a week earlier she had been pursued by someone dressed in the uniform of the local bus company. It is a tricky puzzle for our intrepid duo, Anthony Bathurst and Inspector MacMorran of the Yard, to investigate.

Flynn is never afraid to change the format of his stories and this one has a very florid, wordy feel about it, full of quotations and literary references, sporting heroes, though, notably absent, and no little humour and delightful wordplay. I particularly enjoyed his recasting of familiar idioms, such as “I’m a sight for the blepharitic” and “not everyone’s beaker of Orange Pekoe”, and, of course, he could not resist a retread of the Wodehousian “if not actually disgruntled you are far from being gruntled”. And if you are going to swear and curse, you should do it “coram publico”. Great stuff.

A notable change in Bathurst’s character is his reaction to working with Helen Repton. One of a growing breed of female detectives on the payroll of the Yard, we met her in Exit, Sir John (1947) and here her role is that of bait, wearing a copy of the fatal yellow dress, for a trap set by Bathurst to lure the culprit to strike again. She reduces Bathurst to a simpering wreck who falls weak at the knees at the sight of her, bewitched, you might say, a reaction that is more than reciprocated. Made of stern stuff, full of British pluck, nevertheless Helen is no feminist stormtrooper, content to play a subservient role at the behest of her supposed betters.

Bathurst is no infallible sleuth and pursues a number of false leads, intrigued initially by a couple of itinerant showmen and their performing bear, but eventually he gets on to the right path, helped immeasurably by his acquaintance, like in Men For Pieces, with an expert in their field, this time in witchcraft. Now able to put some of the peculiarities with the bodies into context, and noting the similarity of the name of a prolific 17th witch hunter with one of the leading lights of Wavering, he makes a deductive leap which leads to speedy unmasking of the culprit.

With 77% of British households now having access to a motor vehicle, it comes as a bit of a shock when Bathurst learns that of the 171 who attended both the New Year Social and the play, only five were owner-drivers of vehicles, another dead end in the investigation. A fascinating social detail nonetheless, which, along with the exuberance and joie de vivre of the book, makes it an enjoyable read.

My thanks to Victoria Eade for a review copy.

August 14, 2025

Ross Island

British imperial history is full of brutal moments which we now have found it convenient to forget, none more so than the role that Ross Island played in the subjugation of India. An island less than a third of a mile square, it is situated about 800 miles east of the Indian coast in the Bay of Bengal, one of the Andaman islands. It was named after the marine surveyor, Daniel Ross, but in December 2018 was renamed Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose Island after the Indian nationalist.

Archibald Blair established a hospital and sanatorium there sometime between 1789 and 1792 but its real claim to infamy came some six decades later after the Indian Mutiny of 1857. With mainland jails overcrowded, the British decided to establish a penal colony in the remote Andaman archipelago to provide extra capacity. Of the 576 islands that form the archipelago, Ross Island was selected as its strategic location offering safety from attack, and a party of 200 convicts under the control of a British doctor, James Walker, arrived in March 1858 to establish the colony.

For years, the convicts were forced to clear the island’s impenetrable vegetation to make space for an opulent colonial complex, including a luxurious commissioner’s bungalow with carved gables and shaded verandas and a Presbyterian church fitted with stained glass window panels imported from Italy. Colonials could make use of manicured gardens, tennis courts, and swimming pools. Although it seemed an idyllic setting and no expense had been spared, many of the British there felt isolated and bored, the posting resembling a form of punishment.

Their life was a bed of roses compared with that of the convicts who were packed close in makeshift barracks with leaking roofs and were overworked, disease-ridden, and emaciated. Malaria, cholera, and dysentery were ever present threats and to make matters worse the British force-fed thousands of prisoners with cinchona alkaloid, an unprocessed form of quinine with severe side effects such as nausea and depression, in illicit medical experiments.

As Indian demands for independence intensified, the British built a more permanent prison, Cellular Jail on nearby Port Blair, where for several decades until its closure in 1937 atrocities were perpetrated against those held there.

In 1941 the area was hit by an earthquake with a magnitude of 8.1 on the Richter scale, killing more than 3,000 people and damaging many buildings. The following year the Japanese invaded the Andamans, driving out the British and pillaging and vandalising Ross island for materials to build bankers. In 1945 the British recaptured the island, the penal colony was disbanded and administrative responsibility was passed to the newly created Indian government.

Today, the jungle has reclaimed the island with just the last lingering remains of the colonial past peeping through the vegetation, the last vestige of an island with a grim past.

August 13, 2025

Dover Two

A review of Dover Two by Joyce Porter – 250703

Perhaps he captures the zeitgeist perfectly. You know he is a despicable character, obnoxious, lazy, quick to claim the successes of others, rude, with a violent temper and only a passing acquaintance with the protocols of police interrogation, but the more you get to know him, the more fascinating Detective Chief Inspector Wilfred Dover becomes. It is astonishing how a prolonged exposure to the grotesque somehow normalizes it.

Following on from Joyce Porter’s Dover One, Dover Two, originally published in 1965, sees the unlikely duo of Dover and the long suffering DS MacGregor sent to Curdley in the north of England to investigate what the press dub the Sleeping Beauty case. Isobel Slatcher was shot in the head twice as she was leaving the vicarage after her usual Saturday evening meeting with the vicar, Mr Bonnington. Although she was not killed, she was left in a vegetative state and some eight or so months later she was found dead in her hospital bed, having been suffocated with a pillow.

Isobel’s boyfriend, Rex Purseglove, serving as an officer of the RAF away from Curdley, curiously was on the scene at both the time of Isabel’s initial attack and her subsequent murder. Her considerably older sister, Violet, is fiercely protective of her sister, as the story progresses we find out more about their relationship, and frustrated that the police have not brought the assailant to justice, persuades the local newspaper to print a story suggesting that Isabel was about to make a miracle recovery in the hope of spurring the attacker to reveal themselves by trying to finish the job off before Isabel can tell what she knows to the police.

Curdley is a town divided along sectarian lines, the police, except for the lower ranks, being Catholic, while the Slatchers are passionate if not maniacal Protestants and are only too ready to ascribe the police’s supposed inefficiency to their religious differences. Prior to the shooting of Isabel a Protestant meeting was raided by a mob of Catholics and a luger, which was used to shoot Isabel, was lost in the melee.

A constant theme of the book is the case of Bigamous Bertie, a notorious polygamist who also murdered some of his wives, who was recently hung after been brought to justice by one of Dover’s colleagues, whom the press, much to his chagrin, dub Super Percy. Super Percy’s rise to fame is not just a thorn in Dover’s side, as there is a connection between the polygamist and the case which he is investigating which only becomes apparent as the story unfolds.

Despite there being very few suspects for the original assault on Isabel, the escape route for the assailant being effectively blocked off at one end by Rex Purseglove and the other by the fish and chip shop owner, Alfred Dibbs, Dover, in his inimitable fashion, manages to charge in and recklessly accuse the wrong person of attempted murder not once, not twice but three times. His third error, though, does lead to the real culprit revealing their identity, which he has the audacity to claim as the result of his subtle ruse.

Dover, though, is astute enough when overhearing a child recite a snatch from The Owl and the Pussycat to release why Isabel had to be murdered in the hospital when she was and that her ultimate murderer was not necessarily her original assailant, a legal nicety over the time that can elapse between an assault and the consequent death for it to be counted as murder. This enables him to wrap that aspect of the case up fairly easily.

Dover, more by luck than judgment, does get there in the end, but not without causing much upset amongst the worthies of Curdley and one feels for the long-suffering and much put upon MacGregor. The book is extremely funny and if you like your crime laced with humour, then this is certainly a book to seek out.

August 12, 2025

The Fever Tree (3)

Improvements in the understanding of how to cultivate cinchona trees and the introduction of Ledgeriana cinchona, whose seeds and cuttings the Dutch East Indian Government were prepared to supply free of charge meant that it now became a viable proposition for private enterprises. This, however, coupled with the discovery of the Remija species in North Africa meant that by the 1890s production was exceeding demand.

There were wide variations in prices and with the Java planters concentrating on lowering the cost of production, many private plantations abandoned the cinchona, uprooting their plantations, in favour of tea, which was easier to grow and offered more certain profits. In 1913 an agreement was drawn up between the cinchona producers of Java and the quinine manufacturers in Java, the Netherlands, Britain, and Germany to put an end to the “great variation in price which jeopardised the security of the bark producers.”

By then Java controlled 97% of the world’s total production with British India supplying 2.5% and other parts of the world just 0.5%. Moreover, British India made no effort to supply to the rest of the Empire, the consequences of which were that, according to an article in Nature in 1929, “the direct loss sustained by the British Empire due to sickness and death caused by malaria is in the neighbourhood of £52 and £62 million per annum”.

Worse still, while the production of quinine “took into account the law of supply and demand” “millions of sufferers are [and continue to be] so poor that they would be unable to purchase quinine at even the approximate cost of production, a situation which led calls in 1931 for the League of Nations to take action on.

During the early part of the 20th century quinine was losing its preferred status amongst medical practitioners because of its unpleasant side effects, prompting efforts to produce synthetic antimalarials such as Atrabine and Chloroquine, the need for which was exacerbated by the outbreak of the Second World War. The major quinine producer, Java, fell to the Japanese and the majority of European quinine reserves, stored in Amsterdam, were taken over by the Nazis.

While synthetic antimalarials have improved by leaps and bounds, the World Health Organisation reported that in 2006 over 247 million people were affected by malaria, of whom almost a million died and recommended that “all countries facing shortages increase procurement of their second-line antimalarial treatment, which is generally quinine”.

For all our advances, it seems we are still reliant upon the medicinal properties of the bark of the cinchona tree to ward off malaria.

August 11, 2025

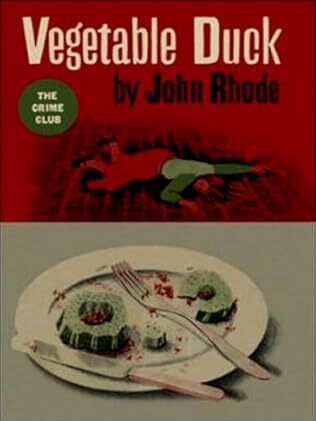

Vegetable Duck

A review of Vegetable Duck by John Rhode – 250701

At the risk of sounding like Julian Clary, I love a stuffed marrow but I did not know that the vegetable stuffed with meat was known as a vegetable duck, at least in the 1940s. This is the key to understanding the curious title of the fortieth book in John Rhode’s long-running Dr Lancelot Priestly series, originally published, and recently reissued in a Kindle version which is riddled with typos. The dish also makes for an ingenious murder weapon with the poison digitalis evenly distributed throughout the vegetable by threading a piece of string through its stem attached to a jar with the deadly substance mixed in the water.

Vegetable Duck, widely regarded as one of Rhode’s finest, is based on a real life crime, the murder of Julia Wallace, who was found by her husband, William, on his return after he had been urgently summoned away to go to an address which did not exist. Was the summons an attempt to give William an alibi or if it was genuine, who made it and were they responsible for killing Julia? Wallace was acquitted and no one has satisfactorily solved the case, making it a fascinating source of inspiration for crime writers.

Just before he was to sit down for his evening meal, Charles Fransham was called away by a phone call and left the flat on what turned out to be a wild goose chase. On his return he met a neighbour, Walter Nunney, and when the two went into the flat, they found Letty, Frensham’s wife, dead, having been poisoned after tucking into the vegetable duck. Was Fransham’s departure an attempt to create an alibi? Inspector Jimmy Waghorn of the Yard is set the task of making sense of it all.

Poor old Jimmy Waghorn. Not only does he have to solve a fiendish puzzle but he also has to subject his findings to a regular Saturday night review at Dr Priestly’s home, during which the eminent professor delights in pouring scorn on his latest theory and providing helpful directions as to how he might more profitably bring the case to a conclusion.

Initially, it seems pretty clear that Fransham is the murderer, especially as he was on the scene when his brother-in-law, Harry Beccles, was killed in a shooting accident. The police believed that Fransham was to blame but could not prove it conclusively. Fransham had been receiving anonymous letters threatening revenge on behalf of the dead man and there was a letter to Letty which had been inexplicably delayed in the post – we are talking of a time when the post was far more reliable than it is now – which had she received it in time would have meant that she would have been out and Charles would have eaten the vegetable duck. Perhaps Charles was the intended victim after all, a feeling intensified when he too is murdered.

Then there is Fransham’s son from his first marriage, Paul, who disapproved of his father’s drinking and disliked his step-mother. Was that motive enough to put him in the frame? Add in the mystery of how the marrow delivered to the flat and by whom, a mysterious visitor, several young men in varying guises and names who crop up from time to time including the mysterious Corpusty, and the insouciant distant relation, Dimsdale, and you have the ingredients for an intriguing mystery.

In essence, it is a story of revenge and greed. Most of what the reader needs to make sense of it all is provided in the early chapters and for the most part the story is fairly clued. The way Rhode leads his reader up the garden path time and time again only to remind them of an awkward fact that does not quite fit in is masterly. It all hangs together in the end, the only loose end being the fate of Beccles.

Priestley’s role is pared back to almost the bare minimum, becoming just the catalyst for moving the story on in different directions. For those who find him a bit rich, that might just be the perfect balance in what is a thoroughly enjoyable story. Pity about the typos, though.