Martin Fone's Blog, page 86

May 18, 2023

There’s Trouble Brewing

A review of There’s Trouble Brewing by Nicholas Blake – 230501

Another new author to me, Blake is the nom de plume of C. Day Lewis, who was later to become Poet Laureate in 1968. Crime fiction was a way to earn some money as he sought to make his name as a poet and his go-to amateur sleuth, Nigel Strangeways, is also someone who dabbles in poetry. This is his third outing, the book originally published in 1937. I usually follow a series in chronological order, but decided to sample this one to see if I liked his style. I did.

The set up appealed to me, with an unusual form of death. Eustace Bunnett is a sadistic, lecherous old man, who runs the local brewery with a rod of iron, refusing to modernise it until absolutely necessary and there are rumours that he is considering selling it to a larger rival. He leads his shrew-like wife a dog’s life as he does his dog, whose decomposed body is found boiled in the brewery’s copper boiler. Bunnett commissions Strangeways, to the sleuth’s amazement, to establish who it was that had done away with the dog in this particularly cruel manner.

Before Strangeways can make much progress in this unusual commission, although it does allow him to make the quip when seeking entry to the brewery that he is there to see a man about a dog, human remains are found in the very same copper boiler, the flesh boiled away so that its identity cannot be exclusively established but there is enough circumstantial evidence – false teeth, clothing, etc – to suggest that it is Bunnett himself. Was the death of the dog a dry run for the murder of his master?

While wandering around the brewery, Strangeways finds a small green object, resting above some frost in the refrigerating room, the significance of which escapes him at the time, but which proves to be crucial to the unravelling of the mystery. Whilst the focus of the enquiries is who would have sufficient motive to kill Bunnett, and there are a number, all of whose motives and alibis have to be checked, Strangeways is not entirely convinced that the murder had gone to plan. Why was it necessary to boil Bunnett’s body so that it was barely recognisable? And where was Bunnett’s brother, Joe, who was supposed to be on a sailing trip but neither hide nor hair had been seen of him or his boat?

Eventually, after an evening’s contemplation over a few bottles of beer – I hope they were Bunnett’s – all the pieces of an intriguing mystery fall into place and Strangeways has the answers. The culprit is apprehended in a dramatic penultimate chapter and Strangeways relates how he figured out what had really happened in the final chapter. Blake plays fair with his reader – all the clues are there – and I was on the right track but was struggling with the motivation.

Strangeways is an amiable companion, a little full of himself and apes his creator’s erudition by throwing in some literary allusions from time to time. As a Classics graduate, I particularly enjoyed his comments that solving a crime mystery was like tackling a Greek or Latin unseen, searching for the subject (victim), verb (motive), and object (culprit). There was no little humour in the book, Blake excellently portraying the pettiness and small-mindedness of close communities and the description of the brewery, its workers, and the brewing process struck me as convincing.

I enjoyed the book and there is yet another series to add to my ever-growing TBR pile, which will see me well into my seventies.

Statue Of The Week (7)

Creating waves in the southern Italian town of Monopoli is a statue recently created by students from the Luigi Ross art school and located near to a children’s playground, part of a €350,000 redevelopment of the Piazza Rita Levi-Montalcini. It is a mermaid, but no ordinary one.

Unlike Copenhagen’s famous mermaid which is demure and so unobtrusive it can be easily missed, the Monopolian version is big, brash, and bold, boasting two enormous silicone breasts and the largest posterior ever seen on a mermaid. What it would have done to the creature’s ability to swim gracefully under water is not clear, but in this age when diversity in all its shapes and forms is to be celebrated, it is bang on trend.

The statue, which has yet to be unveiled formally, has divided opinion, but might just put the Puglian town on the tourist trail!

May 17, 2023

The Devil’s Elbow

A review of The Devil’s Elbow by Gladys Mitchell – 230429

The Devil’s Elbow, originally published in 1951 and the twenty-fourth in her Mrs Bradley series, is one of the nearest to a conventional piece of crime fiction that you are likely to get from Gladys Mitchell. Even so, she does not make life easy for her readers, devising a murder mystery that at its height has thirty-one suspects with several of the principal characters bearing similar names. There are two Miss Tooleys, a Togg, a Miss Nordle, a Miss Durdle, not to mention a Pratt, a Parks, a Peel, and a Pew. The reader needs to keep their wits about them to remember who is who and not to mistake one for another. Added to that she intertwines another mystery, which takes place at the same time but has little to do with the murder.

One of the fascinating aspects of the book is that the story is told from two principal perspectives, that of George Jefferies, the courier of a coach tour taking in the sights of Scotland, George Jefferies aka Dan Chaucer, and that of Mrs Bradley in a series of interviews she conducts with the members of the coach party. Jefferies is a lively and entertaining narrator, and we get a series of memorable pen pictures of the members of the coach party and the principal moments on what was an eventful perspective. These are contained in letters he dutifully sends to his fiancée, Em, who just so happens to be working on a temporary basis as Mrs Bradley’s secretary.

When Miss Pratt’s body is found on a boat that Commander Parks had hired without permission from the tour operator, her head stoved in with a single blow from a rock, Jefferies implores Em to prevail upon Mrs Bradley to assist in unveiling the identity of the killer. Of course, Mrs Bradley, assisted by Inspector Gavin who just happening to be on holiday in the area adds some Scotland Yard heft to the labours of the local police Inspector, naturally named McTaveesh and with a comedy Scottish vernacular accent, needs no second invitation.

Her interviews with the members of the coach party add flesh to the skeleton of Jefferies’ singular narrative and we can view events from their perspective and see whether the courier’s description of events and characters coincide with the recollections of others. One of the coach party, Miss Durdle, has kept her own idiosyncratic diary. The two narrative perspectives work well, and Mitchell writes with a light touch, extracting much humour from the characters and situations that she portrays.

With a murder amongst the party and an unauthorised boat trip, it is no surprise that Jefferies’ services are no longer required, although he is handsomely paid off, and he is roped in by Mrs Bradley to track down a motor caravan that was seen suspiciously near the spot where Miss Pratt was murdered. This leads to an amusing chase around eastern Scotland, culminating in Jefferies commandeering a boat which is taking part in a smuggling racket being observed by the naval authorities. This side plot, highly entertaining and amusing, turns out to be just that, but for me it was the highlight of the book, Jefferies being one of Mitchell’s more colourful and well-developed characters.

As for the identity of the murderer, this is derived by a lengthy elimination of the suspects. Mrs Bradley is an eminent psychoanalyst and the motivation behind the murder is jealousy and the fevered imaginings of a frustrated mind. I was not convinced that the feelings unleashed by the claustrophobic atmosphere of an organised coach tour would result in murder most foul, so the denouement was a little disappointing in my view. Nevertheless, like a coach trip there was much to admire along the way, even if the destination did not meet my high expectations.

The eponymous Devil’s Elbow is a pass of the Cairnwell on the route between Glen Shee and Braemar, one that was dreaded and tested the mettle and metal of many a charabanc at the time.

This is one of Mitchell’s more accessible novels and I raced through it.

May 16, 2023

Twice Round The Clock

A review of Twice Round the Clock by Billie Houston – 230427

This is a curiosity, originally published in 1935 and recently reissued as part of the excellent British Library Crime Classics series. This is the only work of crime fiction written by Billie Houston who was better known at the time as a performer and film star, part of a double act on stage with her sister, Renée. In modern parlance, it would be a book by a minor celebrity, Houston modestly acknowledging that her status was probably the principal reason for her finding a publisher. It is not a bad book, but classic it certainly isn’t.

Part of the problem is that it cannot quite make up its mind as to whether it is a murder mystery or a thriller and as a consequence, we get a bit of both, the larger part of the book concerning itself with who did away with the dastardly Horace Manning, and then suddenly, almost without warning, diving into spy thriller territory before trying to wrap all the loose ends with a twist or two before it finishes.

There are some oddities along the way. Firstly, there is no formal police investigation and what sleuthing is done in a pretty haphazard and amateurish way is accomplished by the book’s all-action hero, Bill Brent. Then Dr Henderson, who is one of the party, suddenly becomes an elderly man well into the second part of the book, old or elderly becoming inseparable Homeric epithets whenever he is referred to, although in the earlier parts of the book there is no specific reference to his age. His seniority is quite germane to the plot’s resolution, and it reads as if Houston had remembered just in the nick of time to make it clear. A sharper sub-editor might have smoothed the transition. And then there is one of the maids, Alice, whose change in character is both unexpected and unbelievable.

The set up for the story is full of hackneyed tropes – set in a gothic like country house where a house party has assembled to celebrate the engagement of Tony Fane to Manning’s daughter, Helen, but the weather intervenes, torrential rain of biblical proportions with copious amounts of deafening thunder thrown in, meaning that the guests cannot leave and even if they wanted to, their cars have been tampered with. The telephone line has either been cut or disabled so thy cannot summon outside help. What could possibly happen?

Written at the time that the situation in Europe is worsening and fears that Europe will be engulfed in another terrible war, it, like Moray Dalton’s later (1936) The Case of the Kneeling Woman has its heart a mad scientist, Manning in this case, who has developed a deadlier, more effective killer gas which other governments are desperate to get their hands on to gain a military advantage. Manning has just finished developing his gas and as a party piece treats his guests to a demonstration of its effectiveness by indulging in a spot of felixocide, to the horror of all who witness it and to the somnambulant housekeeper, who has taken the house’s cats under her wing.

This demonstration underlines the sadistic streak in Manning’s character, also evidenced by his treatment of Helen who is petrified of him. To no one’s surprise, Manning is found dead, slumped over a photograph album, with a carving knife plunged into just the right spot of his back to ensure instantaneous death. His butler, Strange, is found in the garden, crushed by a falling branch, and in his death throes vigorously denies that he killed Manning.

There are more than enough suspects to keep a sleuth occupied and to his credit Brent does identify the culprit, although it takes a quasi-deathbed confession to confirm the truth. In the twenty-four hours that the book covers, hence the title, there is still enough time for three masked intruders, aided and abetted by someone in the house, to break in, steal Manning’s formula, and tie up the guests who by this time think that this is a house party to end all house parties. Their dastardly act is thwarted and almost everyone gets to live happily ever after.

Booby traps, vitriol, sleepwalking, and an amazing feat of derring-do all add to the drama. There are some strong characters, not least Katy Fane who finds love and realises the error of her ways, but long-suffering Helen Manning is a drip who would not be out of place in the pages of Patricia Wentworth.

This is a book with many flaws but like a badly holed boat does manage to reach shore and deliver a mildly entertaining and certainly curious story.

May 15, 2023

Bluebell Glue

Bluebell bulbs are full of a viscid juice and are poisonous in their fresh state, at least for humans and most animals except, curiously, badgers. To consume them in large quantities could be fatal. Some folk traditions played on the flower’s inimical properties.

Bluebells were said to be used in witches’ potions. Nightmares could be warded off by placing bluebells under a pillow or hanging them above the bed. As faeries were said to hang their spells on the petals to dry, inadvertently brushing against them might unleash their magic or, at the very least, incur their wrath. So enchanting was a walk amongst bluebells that there was a risk of losing all sense of direction and being trapped in the woods.

Children who picked a bluebell were likely to be whisked away, never to be seen again, and many believed that picking the flowers and bringing them indoors was a harbinger of ill luck. Bluebells were used by faeries to summon meetings but to hear one ring was especially bad luck; it presaged your own death. Not for nothing were they known as Dead Men’s Bells.

They were also known, colloquially, as Wood Bell, Wild or Wood Hyacinth, Cuckoo’s Boots, Witches’ Thimbles, Lady’s Nightcap, Culverkeys, Fairy Flower, and Jacinth. Confusingly, as Margaret Baker pointed out in The Folklore of Plants (2013), “bluebell is the Scots’ name for harebell, while harebell is Shakespeare’s name for wild hyacinth and bluebell”.

Herbalists valued bluebells for their diuretic and styptic properties, using them to treat spider bites and, according to Tennyson, snake bites as well as for dealing with leprosy and tuberculosis. Although scientists have established that bluebells contain at least fifteen biological active compounds used to repel insect and animal pests, modern medicine has rather turned its back on their healing properties.

Tudor botanist William Turner’s New Herbal (1568) suggested that bluebell bulbs were put to other uses; “the boyes of Northumberlande”, he wrote, “scrape the roote of the herbe and glew theyr arrows and bokes wyth that slyme that they scrape of”. John Gerard also referred to this practice in his Herball (1597) when describing the “blew Harebels or English Jacinth…which spring up naked or bare stalks laden with many hollow blew flores of a strong sweet smell stuffing the head”. His description of the bulb noted that it was “full of slimy glewish juice, which will serve to set feathers upon arrows instead of glew or to paste books with; whereof is made the best starch next onto that of Wake robin roots”.

Geoffrey Grigson in A Herbal of All Sorts (1959) took an empirical approach to discovering whether bluebell glue was effective. In April 1945, finding that the covers of the notebook into which he had transcribed the passage from Turner were coming adrift, he “pasted in paper at each end with scrapings from a bluebell bulb; and then wrote inside the cover “REPAIRED WITH BLUEBELL GLUE: APRIL 1945””. Thirteen years later, after using the notebook “a good deal”, his “two paper hinges were as firm and fast as ever”.

Of course,” he concluded, “the bulb stores up starch; and the starch does the sticking”. However, such is the confusion over nomenclature that, as the Eternal Magpie points out in a post written in her blog after extensive archival research, it is far from clear whether Turner and Gerard were talking about the bluebell or the English Hyacinth. Grigson’s experiment, though, suggests that bluebells could well have been used.

That glue made from bluebells was used to bind books and attach feathers to arrows is now an established “fact” on the internet. Secondary sources also suggest that starch sourced from the bulbs was used in the 16th century to stiffen ruffs and by the Victorians to starch their collars.

When next I gaze upon a swathe of bluebells, I will remember that these beautiful flowers also played a small part in disseminating knowledge and maintaining the country’s military prowess, another reason, perhaps, why they are so closely associated with St George.

May 14, 2023

Lost Word Of The Day (36)

Serious and destructive fires seem to be becoming more frequent around the world, the result of changing climatic conditions, we are told, and, occasionally, human carelessness or stupidity. It struck me that the English language struggles to differentiate between the intensity of fires and we usually have to resort to explanatory phrases around the noun of fire to illustrate the degree of ferocity and the extent of damage it has caused.

It was not always thus. In the 17th century, when the construction and proximity of housing meant that fires were more of an everyday event, a seriously destructive fire or conflagration was known as a scathefire. Thomas Heywood, the Jacobean playwright, used it in 1611 thus; “Beneath their ruines: and these horrid sights / Lighted by scathe-fires, they that haue beheld…”

Might we need to resurrect it?

May 13, 2023

Lost Word Of The Day (35)

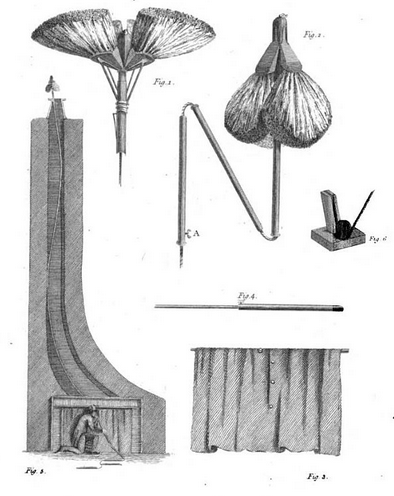

We no longer send small boys up chimneys to clean the hard to reach places, although, given half a chance, it is a practice that might appeal to certain sections of the current government. That the practice was deemed no longer necessary was due in part to a Camden timber merchant and carpenter, George Smart, who in 1802 came up with a Scandiscope.

It consisted of a series of hollow rods which could be attached to other and pushed up a chimney. When the first section reached the top of the chimney, pulling the cord opened out a brush which could then be pulled through the chimney to clean it.

Smart’s invention was a commercial success and even spawned a campaign group, snappily entitled the “Society for Superseding the Necessity of Climbing Boys, by Encouraging a New Method of Sweeping Chimnies, and for Improving the Condition of Children and Others Employed by Chimney Sweepers”. Amongst its supporters was William Wilberforce. Their campaign posters included this piece of doggerel; “some wooden tubes, a brush, a rope, / are all you need to employ; / pray order, maids, the Scandiscope, / and not the climbing boy”.

In 1805 Smart was awarded a gold medal by the Society for Arts for the greatest number of chimneys cleaned by mechanical means. As the 19th century progressed, more chimney sweeps adopted Smart’s extendible brush, the design improved by the likes of Joseph Glass. A variation of Smart’s original Scandiscope is still used today.

Small boys have a lot to thank Smart’s Scandiscope for.

May 12, 2023

The Crime At Tattenham Corner

A review of The Crime at Tattenham Corner by Annie Haynes – 230425

Originally published in 1929 and reissued by Dean Street Press, The Crime at Tattenham Corner is the second in Haynes’ Inspector Stoddart series. The story starts on the eve of the Epsom Derby, the race in which Sir John Burslem’s horse, Peep O’Day, is the bookies’ favourite. The horse does not run to the dismay of many who have put their shirt on the animal as Burslem’s body is found in a ditch near Tattenham Corner, a village and railway station near the racecourse. Under the rules of the race, if the owner is dead, the horse has to scratch.

The second favourite, Perlyon, wins the race and Burslem’s death – he was shot but not at close range – immediately puts suspicion on its owner, Charles Stanyard, who was not only in the area at the time but also was engaged to Burslem’s much younger wife, Sybil. Needless to say, the plot is a lot more complicated than that. We are treated to lashings of spiritualism, thanks to the ludicrously preposterous Mrs Jimmy Burslem, wife of the explorer, Burslem’s brother James, who is believed to be in Tibet, a disappearing head valet, Ellerby, and a number of physical clues, a handbag, a cigarette case, and a revolver found near the scene that turns out not to have been used in the murder.

Just before his death, Burslem, a successful financier, had time to make an unexpected return to his home and changed his will, handing over all his wealth and assets to his wife, Sophie, and cutting his daughter, Pamela, out completely. It is not long after his death that Peep O’Day is surprisingly sold to Argentinia and Sophie is in cahoots with an Argentinian secretary who is assisting her with administering Burslem’s former affairs.

There are a number of suspects, each of whom has their moment under the spotlight and Haynes’ best moments in this rather sprawling novel that she seems at times to barely control is to shift the reader’s suspicions from one to the other. For me the highlight of the book is the working relationship between Stoddart and his assistant, Alfred Harbord, who are amiable companions and work well, although they have slightly differing views as to what really happened to Harbord. Stoddart adopts a slightly patronising attitude to his junior, allowing him the room to show initiative and develop his own theories only to gently puncture the theory by pointing out some clue or inference that does not fit into the explanation.

Stoddart, though, is no inspired detective whose brilliant intellect sees through the cunning plans of the murderer. He too struggles to fit all the facts, clues, and inferences into a coherent case and when he steels his nerve to make an arrest in an amusing episode that involves him assuming a disguise to gain entry to the suspect’s suite – disguise and misidentification is a running theme through the book – it is clear to the reader that the case for the prosecution has so many holes in it that a competent defence lawyer would drive a coach and horses, never mind a thoroughbred, through it.

Nevertheless, to court it goes and the trial is a society sensation. That Stoddart has backed the wrong horse is revealed by a death bed confession, the true culprit having been involved in what turns out to be a fatal road accident but still, like all good Catholics should, has time to unburden their soul before meeting their maker. I always feel that these death bed confessions are a bit of a cop out on the part of the writer, and everything is wrapped up a little too tidily with more than an unhealthy dollop of “and they lived happily ever after” for my taste.

The book has more than a touch of the melodramatic potboiler about it, but it is entertaining and kept me guessing until the end.

May 11, 2023

Invitation Of The Week

The postal delivery service is so intermittent around Blogger Towers, now down to once a week and I have taken to recording each one on a calendar, that I am not sure whether I was invited to the Penny Mordaunt Trial of Strength show held at Westminster Abbey last Saturday or not. I rather assumed (and hoped) not.

Someone who did receive one was Olena Zelenska, the first lady of Ukraine. It always surprises me that a war-torn country seems to have functioning infra-structure services and a plentiful supply of fresh fruit and vegetables, but that is another story. So proud was she that she took to social media with a photograph of said invite.

Eagle-eyed observers spotted a massive error in the beautifully calligraphed invitation – her country’s r had been omitted. As if the country had not suffered enough. Someone will be spending the rest of their days in the Tower of London, methinks.

May 10, 2023

The Ivory Dagger

A review of The Ivory Dagger by Patricia Wentworth – 230422

The Ivory Dagger, the eighteenth in Patricia Wentworth’s Miss Silver series, originally published in 1950, falls into three parts. The first seems to come straight out of a Victorian melodrama where a unfeeling guardian, Lady Sybil, is railroading her weak but beautiful ward, Lila Dryden, into an unsuitable marriage to a rich older man, Sir Herbert Whitall. Then it morphs into a version of Sir Walter Scott’s Bride of Lammermoor as shortly before the nuptials Lila is found over Sir Herbert’s body, an ivory dagger by her side bearing her fingerprints and her white dress smeared with his blood. In the third part is a conventional murder mystery as Miss Silver, brought in by Lady Sybil, and the ever-adoring Inspector Abbott, later joined by the curmudgeonly Chief Superintendent Lamb, get to grips with solving the case.

This was the first of three novels that Wentworth published in 1950 and the book bears the hallmarks of a rushed job to meet a deadline. The book is written as a standalone novel rather than as part of a series, an approach that allows her to cut and paste sections from earlier works describing Miss Silver’s house, her dress, and her relationship with Abbott, to name just three areas. There is also a major omission in the conclusion to the book. She never satisfactorily explains why Lady Sybil, who had grounds enough to murder Sir Herbert, was never considered to be a suspect and why she was forcing Lila into marriage. Were the suggestions that she had run through Lila’s inheritance and that Sir Herbert knew and playing that knowledge to his advantage well founded?

Sir Herbert Whitall is another in a long line of characters in detective fiction whom a motley crew of suspects would rather see dead. Rather conveniently he assembles them all at his country home, Vineyard, for a dinner party and, surprise, surprise, he is murdered later that evening, found dead in his study with an ivory dagger, one over which he and a fellow collector, Professor Robinson, had argued over its authenticity. The prime suspect is the somnambulist, Lila, found on the spot red-handed, but no one in the house can believe that such a painfully weak character could summon up the courage to commit murder.

Among the other suspects is Bill Waring, with whom Lila was unofficially engaged and whom we meet in the opening chapter, lying in an American hospital after a railroad accident. When he returns to Blighty he learns that Lady Sybil has taken advantage of his absence and enforced silence to secure her ward’s future elsewhere. He rushes to Vineyard to rescue her and is on the scene when the body is found. Or was it Withall’s impecunious cousin, who was due to inherit his fortune under a will that was about to be changed due to the forthcoming wedding? Or was it the long-suffering secretary with whom Sir Herbert had an affair and a child who bears a grudge now that he is marrying someone else? Or is it the bumptious Professor whose magnifying glass was found at the murder scene?

Miss Silver and Inspector Abbott have their work cut out as they piece together the clues, each interview with a suspect throwing new light on the case and gently leading the reader to change their mind as to whodunit. It is Miss Silver, naturally, who spots that the butler’s assistant, Frederick, is the key to the mystery and it is through his evidence that the culprit is unmasked.

To my mind, the book only really gets going in the third section, the first two parts being a little to leisurely for my taste, as much intent on ensuring that there is enough love interest to keep the romance fans happy as moving the plot along. Nevertheless, for all the signs of rush and some straggly loose ends that even Miss Silver would struggle to knit something out of, Wentworth is a consummate storyteller and this reader was happy enough to switch his mind off and enjoy the ride.

My takeaway is that someone who seems to be doing their job might just not be.