Martin Fone's Blog, page 92

March 20, 2023

The LP – Side Two

In 1889 two competing recording formats emerged, the all-wax cylinder, used in Edison’s “Perfected Phonograph” and the Gramophone, the world’s first record player, patented by German-born US inventor, Emile Berliner. Both formats were able to reproduce about two minutes’ worth of professionally made pre-recorded songs, instrumentals, and monologues, and while the Phonograph allowed the owner to record their own music too, the Gramophone was louder.

Cylinders played at 120 revolutions per minute (rpm), later increasing to 200 rpm to improve volume and squeeze in more material, whereas Berliner’s hand-cranked seven-inch records made from vulcanised rubber operated at a statelier speed, between sixty and 75 rpm.

Despite its fragility, the introduction of shellac, a resin derived from female lac beetles, which allowed more grooves to be cut into the record, started to swing the pendulum in the gramophone’s favour, cemented by the launch of the Red Seal label in 1903 featuring ten-inch shellac records playing at 78 rpm. It was a format that was to serve music lovers for almost five decades. Cylinders were quietly dropped from around 1912, although Edison supported them until 1929.

Flexible plastic discs made from Polyvinyl chloride (PVC or vinyl) were sent to radio broadcasters in the 1930s as they were more robust and produced better, more consistent sounds than shellac records, but they were not commercially available, the aftermath of the Great Depression dampening down the appetite amongst companies and consumers alike for technological innovation. However, a combination of a shortage of shellac after the Second World War and the development of the microgroove system in 1947 by Peter Goldmark and his team at Columbia Records set the stage for the next revolution in record production.

In 1948 the engineers at Columbia had developed a twelve-inch long-playing record, spinning at 33 and 1/3 rpm and holding about twenty-three minutes’ worth of music on each side. The first demonstration disc, ML4001, featured Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto in E minor played by the Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra of New York (now known as the New York Philharmonic) under the baton of Bruno Walter.

Other early offerings included 12-inch discs featuring Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue and Greig’s Piano Concerto in A with Oscar Levant at the piano, Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, favourites from Bizet’s Carmen, and ballet suites from Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker and Khatchaturian’s Gayane. The collection was completed by two ten-inch records featuring a selection of Strauss waltzes and the music of Stephen Foster. Ten thousand of each of the albums were sent to Columbia’s distributors in readiness for the launch on June 21, 1948. The LP era had begun.

The Columbia Catalogue for 1949 waxed lyrical about its innovation, pointing out that their LP records played approximately six times more music than conventional shellac records allowing the listener to enjoy the world’s greatest music in one sitting, and that they were much more robust. “Each LP record”, it trilled, “consists of scores of microscopically fine grooves, precisely controlled channels capable of capturing the most subtle nuances or most magnificent fortissimi”.

Columbia Records, though, did not have everything their own way, with RCA Victor introducing their own LP format shortly afterwards, just seven inches in diameter and revolving at 45 rpm. Over the next two years the companies battled it out in what was dubbed “The War of the Speeds”, but eventually the twelve-inch revolving at 33 and 1/3 rpm settled down to become the predominant format for albums and the seven-inch 45 rpm disc for singles and extended play records (EPs).

The advent of stereophonic recordings in the 1960s and the phasing out of mono sound in 1968 heralded the heyday of the vinyl, allowing contemporary musicians, arguably, to push the boundaries of musical creativity.

Vinyl might have been eclipsed by other formats, but its flame has been kept alive by many including Britain’s vinyl collecting community, of whom, a recent Royal Mint survey into collecting habits revealed, 32% live in Glasgow[1]. The format’s renaissance suggests that their faith was justified, and plans are underway, in the year that the vinyl LP celebrates its diamond anniversary, to hold the world’s first festival designed purely for vinyl enthusiasts in Haarlem in the Netherlands[2].

The vinyl revolution is not over.

[1] https://thevinylfactory.com/news/glasgow-uk-vinyl-collecting-capital/

[2] https://djmag.com/news/worlds-first-vinyl-focused-festival-launch-next-year

March 19, 2023

Lost Word Of The Day (20)

Even in my disreputable youth I managed to avoid the dubious pleasures of molrowing. A term used in the 19th century it was defined in John Camden Hotten’s A dictionary of modern slang, cant, and vulgar words, published in 1859 as to be “out on the spree” in the company of gay women, a euphemism as the time for sex workers. It was said to have owed its origins to “the amatory serenadings of London’s population of cats”.

March 18, 2023

Lost Word Of The Day (19)

As medical techniques improve, historic drastic and, probably, ineffective treatments have fallen into disuse, as well as the nouns describing them. Amongst the now lost medical terms from the 17th century are mochlic used to describe a drastic purgative medicine and panchymamogue, medicine which purged all the humours from the body.

From the same era was a rare, archaic and alternative adjective for hepatic, jecorary. Meaning “of the liver” it was derived from Latin jecur (liver) and the French adjective jécoraire. However, I always prefer a Greek root, given the choice.

One of my pet fears is to lose my sight. An archaic term for being blinded that was extant in the 17th century was occaecation, from the Latin noun caecus meaning blind. Let’s hope I do not have to use it.

March 17, 2023

The Loss Of The “Jane Vosper”

A review of The Loss of the “Jane Vosper” by Freeman Wills Crofts – 230224

One thing you can say about Freeman Wills Crofts is that you know what you are going to get – a logical, well-crafted puzzle which more than makes up for what it might lack in excitement in a satisfying whole. This is the case with the Loss of the “Jane Vosper”, originally published in 1936 and the fourteenth in his Inspector French, a tale of maritime disaster, fraud, and theft.

The highlight of the book is the opening chapter, a low-key but gripping description of a disaster at sea, the eponymous ship hit by four mysterious explosions in its No 2 hold and despite the calm and earnest endeavours of the crew, led by soon to retire captain James Hassell, it has to be abandoned and sinks to the bottom of the sea. The ship was behind schedule – a telling point – and amongst its cargo is a shipment insured by the Land and Sea Insurance Company for £105,000 (about £8 million at today’s values), the loss of which represents a major blow to the insurer’s balance sheet and dividend prospects.

Like all good underwriters, the insurers, whilst acknowledging their moral responsibility to meet the loss, look desperately for reasons to decline the claim. What had caused the explosions and why had this shipment exploded? The send their ace insurance investigator, John Sutton, to dig into the circumstances of the loss, but he mysteriously disappears without trace. It is at this point that Chief Inspector French of the Yard, who knew Sutton, is called in to find out what had happened to him.

What might have been a routine case of possible insurance fraud turns into a man hunt and French’s premonitions that Sutton had stumbled upon something for which he paid with his life prove well-founded. French is nothing if not diligent and thorough, no avenue too obscure to go down, no supposition too fanciful to ignore. It results in a lot of mind-numbingly tedious checking, double-checking, rifling through directories, visits, fruitless inquiries and much more, all of which Wills Crofts lovingly records in detail. It reads at times like a literary version of French’s investigative notes.

If there is one accusation that can be levied against French it is that he immerses himself so much in the detail that he occasionally cannot see the wood for the trees. He is full of enthusiasm over a new lead. One such, drawing inspiration from Conan Doyle’s The Red-Headed League, is that a workshop and a large quantity of timber was used to dig a tunnel over the Royal Mint. He obtains authority to excavate the workshop and while there is no tunnel, he does find the body of the unfortunate Sutton whose head had been bludgeoned in. As the investigation nears its conclusion French often has cause to castigate himself for missing a vital piece of information that was staring him in the face. There is no attempt on Wills Croft’s behalf to paint his detective as an infallible genius.

The case ultimately falls into two parts – the murder of Sutton and the interception of the cargo to be sold to another party, a remarkably accommodating Russian government, while the substitute cargo is fitted with explosives to ensure that the deception is not detected. It all hangs together and makes for a satisfyingly logical puzzle.

The pace of the book marginally increases as the case reaches it denouement, including a car chase conducted at a speed of between twenty-five and 29 mph. It rather fits the tone of the book, some thrills and spills but conducted at a pace that will not scare the horses. Look out for some fascinating glimpses of post-Depression Britain and Crofts’ love of all things maritime shines through in a book that is worth persevering with.

March 16, 2023

Discovery Of The Week (11)

To the consternation of pub quizzers the world over Japan has just announced that it has discovered it has 7,000 more islands than it had previously thought. The digital mapping exercise conducted by the Geospatial Information Agency of Japan revealed that there are 14,125 islands in Japanese territory, and not the figure of 6,852 that it has used since 1987.

The reason for the discrepancy is that the earlier technology used “was not able to distinguish between small clusters of islands and larger ones”, a spokesperson said, resulting in thousands of islands were counted as one, and not because they were hiding in the water waiting to discover that the war was over.

March 15, 2023

Ten Trails To Tyburn

A review of Ten Trails to Tyburn by Bruce Graeme – 230221

Ten Trails to Tyburn is the fifth in Bruce Graeme’s series featuring bookseller and library owner, Theodore Terhune, originally published in 1944 and reissued by Moonstone Press. A bibliomystery, Graeme once more experiments with the format of the crime fiction genre, producing an entertaining and engaging if somewhat overlong story.

A tramp known locally as Peter the Hermit is found dead in a shelter deep in the woods where he has scraped an existence for around ten years. The post mortem suggests that the years of poor diet led to a fatal weakening of his heart. No one can give him a positive identification. It seems as though the tramp’s death will remain in the police files as an unfortunate incident which requires no further investigation. Visiting the shelter Sergeant Murphy and Terhune find a Bulgarian newspaper from 1923 and an elaborately bejewelled comb hidden there, unusual keepsakes for a destitute tramp to keep, especially as the comb could have raised some much-needed cash.

Terhune’s investigative juices are set flowing as he and Murphy receive anonymous missives containing a series of short stories under the omnibus title of Ten Trails to Tyburn. They quickly deduce that the stories contain clues to the identity of Peter the Hermit, his backstory and, possibly, the reason why he dies. However, their task is made difficult because the stories are more cryptic than evidential, owing much to the style and humour of Guy de Maupassant. The fifth story they receive shows a marked change of style and suggests that they are barking up the wrong tree.

Terhune stops at nothing to unlock the mystery, developing elaborate theories from the hints dropped in the story and even travelling to France to establish the significance of the cutting from the Bulgarian newspaper. They discover a story of fraternal enmity, greed, and revenge. While the tramp had died a natural death the culprit had so arranged affairs that given his poor health and weak heart an unexpected surprise was likely to provoke a fatal cardiac arrest. It also becomes apparent that there are two authors of the stories, the first seeking to bring the person who contrived the tramp’s death to justice and the second to stymie the investigations.

Through a process of elimination Terhune has produced a character profile of the two writers and given the characters that we meet as the book progresses, it is surprising that he does not make the final leap. There is only one couple that fill the bill. When charges of murder cannot be laid, the aggrieved party takes matters into their own hands and obtain the satisfaction of settling an old score before fleeing. Terhune receives what is the tenth short story (six to nine are not included in the narrative) which reveals that his reconstruction of the reason for the writer to seek justice was wrong and that marital infidelity was at the heart of the matter.

This is another Graeme book which, while published during the Second World War, anticipates life after the war has ended. In one fascinating passage Terhune (Graeme) speculates about the attitude of the French to English tourists; will they regard them as heroes, representatives of a conquering nation, or will they be resentful that their country bore the brunt of the ravages of war? Another oddity is that Murphy seems to have become more idiomatically Irish in his speech. The Julia, Helena, Terhune love triangle rumbles on, although it seems nearer to resolution as Helena’s amatory attentions seem to be moving elsewhere.

The plot is not as complex as some, as though Graeme’s inventive energy has been spent in creating the literary pastiches rather than on the complexity of the story line. There are some interesting characters and not a little humour, parts of the book read like a love poem to the pastoral splendours of Britain and a stylistic oddity is Graeme’s penchant for listing items. As a mystery, though, it is disappointing as the culprit is too obvious. If you read the book, read the Introduction afterwards as, unfortunately, it gives the game away.

Graeme is always challenging the conventions of the genre, and on the whole this is one of his better efforts.

March 14, 2023

Death of Mr Dodsley

A review of Death of Mr Dodsley by John Ferguson – 230218

I had not read any of John Ferguson’s crime fiction before, but the recent reissue of Death of Mr Dodsley, originally published in 1937, as part of the British Library Crime Classics series prompted me to pick up a copy. It is sub-titled a London bibliomystery and is concerned with the murder of a second-hand bookseller, the eponymous Mr Richard Dodsley. Ferguson goes to great pains in the book’ epistolary dedication to point out that his narrative will be fairly clued and, to be fair to him, it is, perhaps too fairly as some readers will champ with impatience as the investigators dawdle towards a resolution. My take on this was perhaps influenced by having just read Brian Flynn’s The Case of the Faithful Heart which uses a similar device.

The best part of the book is the opening chapters. Surprisingly, we start in the Houses of Parliament where MPs are preparing for an important division upon which the Government’s future is at stake. It is a clever device to introduce us to an up-and-coming politician, David Grafton, who is leading the opposition to the bill and, through him, his daughter, Margery, who has just written a crime novel, Death at the Desk, which has been panned by the critics and, to her face, by her boyfriend, Dick Dodsley, the bookseller’s nephew, as being too unrealistic.

The focus then switches to the environs of Charing Cross Road where a rather slow policeman has to deal with a drunken man who detains him with a story of an open door in the street. When free from his limpet-like drunkard PC Roberts finds the door, pushes it open and finds the body of Mr Dodsley who has been shot. The only clues are three discarded cigarette butts, two spent matches, and a straight hair clip. Dodsley had been working late – he was murdered according to his smashed watch at 3.04am – to complete a catalogue of rare books which had to be delivered to the printers the next day. Clearly, someone was waiting for him and had removed some of the books to make a spyhole through the bookshelves to his desk.

Immediate suspicion falls upon the nephew, especially as there had been some rare books stolen during the previous few weeks, which amateur sleuth, Macnab, had been called in to investigate without success. Ferguson has fun in drawing Dodsley’s three assistants, the ambitious but impecunious Carter and two female assistants who have their claws into each other and one of whom is besotted by both the cinema and Dick Dodsley. To add to the mix there are striking similarities to Dodsley’s death and the murder in Margery Grafton’s novel.

Leading the police investigation are Inspector Mallett – yes, another Mallett, an officer sharing the same surname as Mary Fitt’s series detective – and Sergeant Crabb who represent the old and new schools of policing respectively. They make heavy weather of the case, convinced that there were a pair of accomplices, a man and a woman. Macnab, called in to protect Dick’s interests by Margery, fares little better initially but the pace of the book, which has almost slowed to a standstill, picks up as he gets his teeth into the problem.

A lock, a bus ticket, and an overly helpful unhelpful associate move Macnab nearer to the truth. In a scene in which all the suspects are assembled Macnab reveals his reconstruction of what happened that fatal night and reveals the culprit who is promptly arrested. However, there is a further twist in the tale at the end as in a private assignation at the bookshop Macnab hands over some documents to a grateful recipient which explain part of the motivation for a savage and senseless crime.

Margery Grafton’s theory was that murderers always made one mistake. A careless but fatal mistake over a pile of books proved the undoing of Dodsley’s murderer. An enjoyable read, but it was too variable in its quality to be a true classic. Nevertheless, I will look up more of Ferguson’s work.

March 13, 2023

The LP – Side One

Ever since the release in Japan of Billy Joel’s 52nd Street on October 1, 1982, the first commercially available compact disc (CD), vinyl records have been locked in an existential struggle. Digital formats might offer a cleaner listening experience, be more convenient to store, and well-nigh indestructible, but for many audiophiles a vinyl record feels more tangible and “alive” and is better at picking up the subtle nuances that are often lost or muddied in compressed digital recordings. For the romantic each hiss, crackle, and scratch on a vinyl record evokes a memory.

In a surprising but welcome turn of fortunes, the sales of vinyl in the UK in 2022 exceeded those of CDs for the first time since 1988, a revival fuelled in part because some major artists, such as Taylor Swift and Harry Styles, have deliberately chosen to record in that format. It is timely too as 2023 marks the seventy-fifth anniversary of the long-playing record (LP).

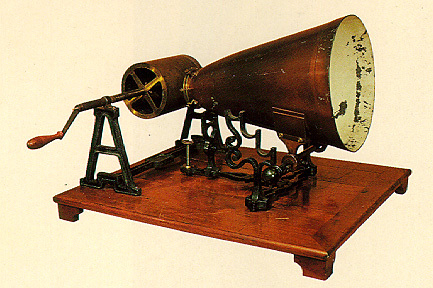

Inspired by some drawings of the human auditory system, French printer of scientific works, Edouard-Leon Scott, worked on a device designed to capture the human voice mechanically. He succeeded in 1853 by replacing the tympanum with an elastic membrane in the shape of a horn and the ossicle with a series of levers which moved a stylus backwards and forwards across a glass or paper surface blackened by smoke from an oil lamp.

Although Scott received a patent for his “phonautograph” on March 25, 1857, it was not a commercial success as the sound, rendered into a series of squiggles, could not be played back. It was not until 2008 when a team from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory succeeded in converting a phonautograph he had recorded on April 9, 1860, into a digital audio file that the true extent of his achievements was appreciated. Scott was heard singing, very slowly, a twenty-second snatch of Au clair de la Lune, predating Thomas Edison’s recording of Mary had a Little Lamb by some seventeen years.

Although Scott went to his grave convinced that Edison had wrested some of the glory that was rightfully his, the American inventor took the concept of voice recording forward by devising a system that played back sounds that had been recorded by transferring it to an embossing point and then, initially, on to paraffin paper and later a spinning cylinder wrapped in tin foil.

Scientific American, in its edition of December 22, 1877, reported that Edison had visited their office and “placed a little machine on our desk, turned a crank, and the machine enquired as to our health, asked how we liked the phonograph, informed us that it was very well, and bid us a cordial good night”. Edison’s patent (No 200,521), awarded on February 19, 1878, specified a particular method, embossing, for capturing sound on cylinders covered with tin foil. It was to prove to be his favourite invention.

March 12, 2023

Lost Word Of The Day (18)

As I advance in age ingeniculation gets increasingly more difficult.It was a noun used in the first half of the 17th century to describe the act of bending the knee, the sort of gesture a lover is supposed to make just ahead of making a proposal of marriage to his beloved. The gesture might have stood the test of time but the noun has not.

March 11, 2023

Lost Word Of The Day (17)

As with all prejudices, heightism is something to avoid. However, in descriptive prose it is sometimes necessary to describe the height of something. For the imaginative writer the rather prosaic “short” does not really cut it. An alternative, used in the mid-17th century but quickly falling into obscurity, is improcerous. Its origin is straight from the Latin lexicon, the prefix im- indicating a negative and procerus being an adjective meaning tall or long.

Perhaps it is due a renaissance.