The Curious Tale Of The Mints With The Hole

Altoids were not sold in the United States until the twentieth century, by which time the Americans had their own curious mint, courtesy of an Ohioan chocolatier, Clarence Crane. Searching for an alternative to chocolate which would withstand the summer heat, he hit upon the idea of producing mints in 1912.

Crane’s mints were white in colour, round and peppermint flavoured, made using the same type of machine with which pharmacists produced their round, flat pills. To ensure that his mints stood out from the competition, he stamped a hole into the middle of each one. As their annular shape reminded him of life belts, Crane called his mints Life Savers, a name that was not without its irony as they were introduced in the year that the Titanic sank. They were advertised with the strap line of “For That Stormy Breath”.

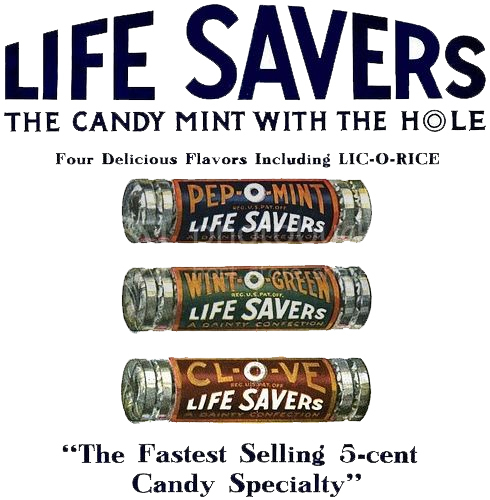

Crane sold his business to E J Noble the following year. A consummate salesman, Noble soon established Pep-O-Mint, the original version of Life Savers, as a household name, partly through the morally dubious method of recruiting youngsters to sell them on commission. Marketing them as “The Candy Mint with the Hole”, he replaced the original cardboard containers which got soggy with tin-foil wrappers to keep the mints fresh.

Life Savers were introduced to Britain in 1916 and manufactured here from 1923, reaching the peak of their popularity in 1931 when sales topped 2.28 million packets. During the Second World War Rowntree’s manufactured Life Savers under licence but the war and rationing saw sales dwindle to almost nothing by 1947.

For Rowntree’s, the 1930s were its golden age, the decade in which the marketing genius of George Harris came to the fore, launching such best-sellers as KitKat, Smarties, Aero, Black Magic, and Dairy Box. He intended to create a mint akin to the Life Saver in 1939, but the advent of war put paid to those ambitions. However, in 1948, judging the conditions to be right he launched what he called Polos, a name, derived from Polar to denote the mints’ cool freshness.

Peppermint flavoured, white in colour, round, approximately 1.9 centimetres in diameter and 0.4 centimetres thick, and with a trade mark 0.8-centimetre-wide hole, there were twenty-three in a packet, tightly wrapped in aluminium foil backed paper. They were even marketed as “The mint with the hole”, capitalising upon Life Savers’ failure to protect their annular shape with a patent. Nevertheless, Rowntree’s felt it necessary to protect their position further by clearly marking on the packaging that the mints were manufactured by them.

Unable to compete with the domestic brand strength of Rowntree’s, Life Savers were withdrawn from sale in the UK in 1956. Subsequent attempts to relaunch them have met with failure.

Now owned by Nestlé, the Polo plant in York can produce 22,000 sweets a minute or 1.37 million packs a day. For those who crunch rather than chew their Polos, it is worth remembering that each mint is put under 75 kilonewtons of pressure, the equivalent of the weight of two elephants jumping on it. And, yes, the mint is made with a hole already in it.

The hole was also responsible for an early outbreak of EU-scepticism. On April Fool’s Day, 1995, Nestlé Rowntree’s marketeers announced that “in accordance with EEC Council Regulations (EC) 631/95” they would no longer be producing mints with holes. Cue national outrage. The following April 1st, inevitably, they suggested they were launching Polo Holes, described as “the hole with the mint”.

With its unusual shape backed by quirky advertising, Polos have found the recipe for suck-cess, maintaining their position as one of the country’s best-selling mints. Their diamond anniversary cannot pass unnoticed.