Yanis Varoufakis's Blog, page 95

October 5, 2018

Ραδιοφωνική συνέντευξη: Οι θέσεις του ΜέΡΑ25 για τα κόκκινα δάνεια και το ελληνικό τραπεζικό σύστημα

Ραδιοφωνική συνέντευξη στο Πρώτο Θέμα, με τους Μπάμπη Κούτρα και Θανάση Τσεκούρα. Ο Γιάνης Βαρουφάκης μιλά για το ΜέΡΑ25, τα κόκκινα δάνεια και το ελληνικό τραπεζικό σύστημα.

October 4, 2018

DiEM Voice presents HERE & NOW: A CREATIVE VISION OF EUROPE, with Brian Eno, Srećko Horvat, Danae Stratou, Bobby Gillespie, Rosemary Bechler & Yanis Varoufakis. Wednesday 10th October 2018 (7pm), Platform Theatre, Central Saint Martins, London

On October 10, “Here and Now: A Creative Vision for Europe” will bring together Brian Eno, Srećko Horvat, Danae Stratou, Yanis Varoufakis, Bobby Gillespie and Rosemary Bechler at the Platform Theatre of Central Saint Martins to consider the role of culture in the fight for the future of Europe. With a range of performance, presentation, and discussion, the event will invite citizens to help shape a new politics of culture – in Europe and beyond.

The event will start with an aerial straps piece by Kit Hill which sees her indicate that perhaps the dystopian future already exists in the present and that the two might in fact be a mirror image of one another.

The event will be moderated by Mary Fitzgerald who is Editor-in-Chief of Open Democracy. Representing the DiEM Voice team, Igor Stokfiszewski will be presenting the cultural policy paper process.

The event is organised by DiEM25 + DiEM Voice, and supported by Creative Unions, a CSM initiative supporting artistic collaboration across borders.

Event details and tickets:

https://www.arts.ac.uk/colleges/central-saint-martins/whats-on-at-csm/platform-theatre

Support a Creative Vision for Europe

https://internal.diem25.org/donations/to/csm_event

DiEM Voice

From its beginning, DiEM25 has placed arts and culture at the heart of its vision of a democratic Europe. DiEM Voice takes this mission forward – dedicated to developing a new vision for culture in Europe and providing a platform for its expression.

Our Conversation

The fight for a democratic culture must address the key assumptions that define Europe’s current cultural regime.

The first is that culture actually means high culture: arts, theatre, opera, film, music that appear inaccessible to the vast majority of Europeans. Works produced at the grassroots, by social movements, and through neighbourhood associations are often dismissed or delegitimized.

The second is that the most appropriate model for sustainable culture is industry: from film and music to art auctions and private collections. Subordination to the market simultaneously cheapens culture — and makes it exorbitantly expensive.

The third: culture is not work. Europe’s cultural space remains highly precarious, both within institutions and outside of them. Artists in Europe are poor and powerless, with little to no social securities or pension support.

Fourth: there’s nothing worse for culture than democracy. Culture is individualistic, it’s irrational, it’s arbitrary. This assumption results in resistance to democratic governance within cultural institutions and organisations — as well as the tight control of cultural production by those with extensive resources.

How to overthrow those barriers? Which other barriers prevent the emergence of a genuinely democratic European culture?

To stimulate further discussion, we have formulated 10 questions that we present to DiEM25 members, experts, and the general public to reflect on the state of the culture war in Europe and what kind of solutions we can put forward to drive the democratisation of the continent.

We believe the above questionnaire can inspire a fruitful discussion on the future of culture and democracy in Europe. If the cultural conflicts on the street, in our homes, and across the internet present real dangers, they also present opportunities to reach people that have disengaged from traditional forms of politics – and to hear their voices in response.

Do you want to be informed of DiEM25’s actions? Sign up here.

October 3, 2018

The 5S-Lega Italian government is continuing the failed Renzi strategy of demanding the right to bend the fiscal rules without demanding a re-assessment of the fiscal rules – interviewed for AGI by Arcangelo Rociola

This is the English language (original) interview with Arcangelo Rociola, published on the AGI site in Italian, on the Italian government’s clash with Brussels over its budget deficit, the plans for a flat tax (that is not flat) and a universal income (that will never be universal), the 5S Movement’s claim to the mantle of the Italian Left, and my pronouncement that Mr Salvini has brought a Fascist Moment into Italy and into Europe.

The Italian government decided to take on Bruxelles deciding for a budget act that enlarges consistently the deficit/gdp ratio (2,4%). What is your opinion about it? Could it be enough to revitalize the Italian economy?

It won’t be enough to revitalize the Italian economy. For that to happen there has to be a major change at the level of the Eurozone, including a large scale investment program and a complete revision of the Fiscal Compact. What the government’s fiscal policy will do, besides igniting a confrontation with Brussels, is slightly to boost aggregate demand and (depending on how much of that deficit spending will be directed to poor families) arrest the decline in real average incomes.

The government is going to approve a budget act in which some of the previous austerity measures are going to be deleted (e.g. the pension reform), while a peculiar form of ‘basic income’ and a sort of flat-tax will be introduced. Some weeks ago you said the Italian economy isn’t supportable anymore. Are these the reforms the Italian economy needs in order to change the situation?

The Italian economy is sophisticated, export-oriented and potentially strong. What I did say, and I am repeating here, is that the Italian economy is not sustainable within the existing Eurozone architecture and economic policies (i.e. the fiscal compact, the policy on bank resolution and reductions in non-performing loans etc.). Turning now to the policies of the government, let us first be frank about the facts: There is no proposal for either a universal basic income or a flat tax. These terms are used for propaganda purposes and have no basis in the reality of what is being proposed. 5S is proposing a minimum guaranteed income (that already exists in most northern European countries) while the Lega is proposing not a flat tax but a major tax rate reduction for those paying the higher rate and the abolition of a medium rate. Are these ‘reforms’ what the Italian economy needs? While the minimum guaranteed income is necessary for many poor families, and will help to some extent boost the economy, the tax cuts for the rich will enhance inequality without doing much to boost spending significantly. In short, the new government’s policies will do some good, a little harm but not have a substantial impact on Italy’s problems within a Eurozone whose rules and policies are not allowing your country to breathe.

Among Italian ministers many say their goal isn’t to undo the EU but to change it from the inside: from Euro to bureaucracy, but also migrants and sovereignty. Does your idea of change for the EU match with that of our government?

No, it does not. If the government wanted to help the EU change in a manner that is beneficial to Italians as well as to other Europeans, it would not be repeating Renzi’s ridiculous mistake. You will recall that Renzi too demanded that Italy be allowed to bend the rules of the Fiscal Compact without having the courage to call upon the EU Council, as the Italian Prime Minister had a right and an obligation, to convene in order to discuss a radical change of the Compact. This government is adopting Renzi’s spoilt-child strategy: Without proposing different rules, a new Compact, it is demanding that Italy is allowed to break the current rules.

As for migration and sovereignty, I am very much afraid that what Mr Salvini is doing – by treating flesh and blood fellow humans floating on the Mediterranean as bargaining chips against Brussels – is to promote strategic misanthropy as a legitimate negotiating tactic within Europe. This Italian government is, to put it bluntly, a clear and present danger for European civilisation.

In your latest book you write about what happened in Greece during the debt crisis describing Greece as an ‘evil experiment’ set up by Bruxelles. Do you see the same risk for Italy in the next years?

No, thankfully. While there are similarities, the differences are larger. Italy is too large to put into a troika-like program or to threaten with expulsion from the eurozone (since such a threat would end the eurozone itself).

Do you think that the Greek debt crisis is ended? Which lesson can we learn from it?

Of course it has not. The Greek state, the Greek banks, most Greek families and companies are bankrupt. Everyone owes money that they can never repay. All the EU authorities have done is to suspend repayments, until 2032, while imposing austerity that will ensure negligible growth in the incomes that must rise substantially for the debts to be repaid. The reason this is tragic is that, meanwhile, the best and brightest leave the country – a loss of irreplaceable human capital. As for the lesson, it is simple and sad: The EU is nowhere near even having the discussion we must have on how to render our common currency area sustainable.

Are there any Italian political parties which are ideologically close to your Diem25?

There are millions of Italians that are close to DiEM25 ideologically and programmatically. We learn this every day, up and down Italy, in the many DiEM25 events across the country. There are also many parties and movements that we talk with – and who are, indeed, close to DiEM25 politically and ideologically. However, we also learn that the Italian people are sick and tired of small parties of the left ‘uniting’ without a comprehensive, a coherent program that makes sense to them. This is why DiEM25 is working to create authentic unity on the basis of a common paneuropean program, rather than a sad attempt to get elected without one.

According to many Italian columnist The 5 Star Movement is the “new left” in Italy, as the Democratic Party is facing a deep crisis. Do you agree with this view?

That 5S has captured many politically homeless leftwing voters, there is no doubt. But, unfortunately, 5S is using those votes to deliver power to Mr Salvini who is bringing a new fascist moment in Italy and in Europe. From this perspective, 5S will go down in history as a reactionary party.

Do you think that Europe will be different after the next European election? How do you imagine it?

Europe is changing anyway, with or without us. Without us, left to the clueless establishment on the one hand and the racist nationalists on the other hand, Europe will fragment and become a reactionary, impotent Europe exactly as Donald Trump wants Europe to be. DiEM25 is active for the purpose of revitalising a humanist Europe that rejects both the austerian establishment and the xenophobic right.

October 1, 2018

Discussing the Labour Party’s fitness for government, Brexit et al – on BBC 2’s Politics Live

Yanis Varoufakis and Conservative MP Ken Clarke join Andrew Neil, along with Camilla Tominey from the Telegraph and Labour’s Rupa Huq. They discuss whether Labour is ready to govern, Jeremy Corbyn’s Brexit meeting with the EU’s Michel Barnier and the Salisbury poisoning suspect reported to be a Russian military officer.

Χώρα Χαμηλών Προσδοκιών – EφΣυν 29 ΣΕΠ 2018

Ο ελληνικός παρασιτικός καπιταλισμός ηττήθηκε κατά κράτος μετά το 2008 χωρίς ποτέ η κατάρρευσή του να δημιουργήσει κάτι το νέο, το ελπιδοφόρο – έστω μια νέα δυναμική καπιταλιστικής συσσώρευσης για κάποια νέα τζάκια. Η πολιτική τάξη που εξέφραζε την ολιγαρχία της προσοδοφορίας στα χρόνια των παχιών (με δανεικά) αγελάδων, κυρίως η Ν.Δ. και το ΠΑΣΟΚ, διαχειρίστηκε όπως όπως την κατάρρευση, υπό τις υποδείξεις και εντολές της τρόικας. Το 2014 η απέλπιδα προσπάθειά της να δημιουργήσει νέα ερείσματα και ατμόσφαιρα ανάκαμψης (ποιος δεν θυμάται το Greekcovery των κ. Σαμαρά-Βενιζέλου;) δεν απέδωσε.

Καθ’ όλη εκείνη τη ζοφερή περίοδο, 2010-2014, όταν η Ελλάδα καταβαραθρωνόταν, είχε σημασία η ύπαρξη μιας οργανωμένης Αριστεράς που επέμενε ότι, ναι, υπάρχει ορθολογική εναλλακτική στη συνθηκολόγηση με τη μνημονιακή διαδικασία. Ακόμα και συντηρητικοί πολίτες, που το χέρι τους «δεν πήγαινε» να ψηφίσουν αριστερό κόμμα, υποσυνείδητα ανακουφίζονταν με τη σκέψη ότι υπάρχει μια οπισθοφυλακή, όσο και να τη φοβούνταν ή την αντιπαθούσαν.

Ηταν «κάτι» εκείνη η ιδέα ότι, αν το Μνημονιακό Τόξο καταρρεύσει, υπάρχει μια κυβέρνηση εν αναμονή που θα δοκιμάσει κάτι διαφορετικό. Εκείνη η προοπτική στο πίσω μέρος του μυαλού κεντρώων, απολιτίκ, ακόμα και συντηρητικών πολιτών ότι τελικά ίσως να υπάρχει εναλλακτική, βοήθησε την κοινωνία να διατηρήσει την αισιοδοξία της στα δύσκολα χρόνια.

Το 2014, το Μνημονιακό Τόξο έμεινε από εφεδρείες στο εσωτερικό την ώρα που έχανε την εμπιστοσύνη του Βερολίνου. Αποτέλεσμα ήταν η δική μας εκλογή τον Γενάρη του 2015. Καθ’ όλο το πρώτο εξάμηνο της χρονιάς εκείνης μας πλησίαζαν στον δρόμο άνθρωποι από όλες τις κοινωνικές τάξεις να μας πουν: «Δεν σας ψήφισα, είμαι δεξιός, αλλά μας επιστρέψατε την ελπίδα, την αξιοπρέπεια. Ευχαριστούμε». Η αντίδρασή τους δεν γεννήθηκε από το πουθενά. Απλά, η αντίσταση στην τρόικα έφερε στην επιφάνεια την προϋπάρχουσα υποψία στο μυαλό πολιτών που, ώς τότε, τα είχαν βρει με το καθεστώς, πως η αντικαθεστωτική Αριστερά μπορεί τελικά να ήταν η απαραίτητη οπισθοφυλακή.

Μια κοινωνία που την καταρρακώνει και πάνω της ασχημονεί ένα ολιγαρχικό καθεστώς έχει απόλυτη ανάγκη από μια αντικαθεστωτική Αριστερά που κρατά ένα μικρό κεράκι ελπίδας αναμμένο στην ψυχή ακόμα και των συμβιβασμένων με το καθεστώς.

Οταν, λοιπόν, το καλοκαίρι του 2015 η κυβερνώσα Αριστερά εντάχθηκε, και μάλιστα τόσο εντυπωσιακά γρήγορα, στη λογική της ρευστοποίησης της περιουσίας του κράτους και των φτωχότερων που απαιτούσε η ένταξη στο Μνημονιακό Τόξο –στον κύκλο δηλαδή των «σοβαρών» και «υπεύθυνων» πολιτικών– η Ελλάδα έχασε κάτι ακόμα πιο πολύτιμο από μια εξαιρετική ευκαιρία απόδρασης από τη Χρεοδουλοπαροικία: τη δυνατότητα να γεννά μεγάλες, ακόμα και μεσαίες, προσδοκίες.

Σήμερα, τρία χρόνια μετά, η παγιοποίηση της τετραπλής πτώχευσης (κράτους-τραπεζών-οικογενειών-επιχειρήσεων) οδήγησε στη μονιμοποίηση μιας μίζερης πάλης δύο τάξεων.

Από τη μία μεριά έχουμε ό,τι έμεινε από την παρασιτική, παρεοκρατική άρχουσα τάξη. Χτυπημένη κι αυτή από την κρίση και με προσόδους πολύ κατώτερες της προ του 2010 εποχής, η τάξη αυτή αποτελείται από κηφήνες που εξορύσσουν προσόδους από τις διαδικασίες ρευστοποίησης της κοινωνίας (π.χ. συμμετέχοντας σε εταιρείες που αγοράζουν κοψοτιμής «κόκκινα» δάνεια για να βγάλουν κατόπιν σπίτια και καταστήματα στο σφυρί, που συνεταιρίζονται με κερδοσκόπους οι οποίοι «χτυπούν» τα περιουσιακά μας στοιχεία που εκποιεί το ΤΑΙΠΕΔ) και, βέβαια, τις παραδοσιακές (αλλά πλέον λιγότερο επικερδείς, λόγω συρρικνωμένου προϋπολογισμού) σχέσεις με το Δημόσιο.

Απέναντι στους κηφήνες βρίσκεται ολόκληρη η υπόλοιπη κοινωνία η οποία διαιρείται σε τρεις κατηγορίες: Στους ακόμα κάπως βολεμένους (ΑΚΒ). Στους εγκλωβισμένους στον φόβο ότι θα χάσουν τα ελάχιστα που τους απομένουν. Και στους εξαγριωμένους.

Οι ΑΚΒ (οι «ακόμα κάπως βολεμένοι», συνήθως σαραντάρηδες και άνω) καταφέρνουν να αναπαράγουν μια επίφαση μεσοαστισμού μέσα από διαδικασίες προσοδοφορίας μικρού βεληνεκούς: ενοικίαση διαμερισμάτων μέσω Airbnb, έσοδα από τουριστικές επιχειρήσεις (σε μια περίοδο εκρηκτικής ανόδου των αφίξεων αλλά μείωσης της κατά κεφαλή δαπάνης), κάποιο μικρό μισθό από κάποιο πρόγραμμα χρηματοδοτούμενο μέσω ΕΣΠΑ κ.λπ.

Τα εισοδήματα αυτά έχουν αυξηθεί κάπως την τελευταία τριετία αλλά όχι αρκετά για να καλύπτονται νόμιμα οι αυξημένες φορο-εισφορές και να δημιουργούν την προοπτική που απαιτείται για την ελάχιστη αισιοδοξία για το μέλλον, ιδίως των παιδιών τους. Είναι όμως αρκετά για να αναπαράγονται, ταυτόχρονα, οι χαμηλές προσδοκίες και η μίζερη πραγματικότητα αυτής της κατηγορίας πολιτών.

Η δεύτερη κατηγορία αποτελείται από τη γενιά των 384 ευρώ (μισθός ακαθάριστος που εισπράττει το ένα τρίτο εργαζομένων) καθώς και οικογένειες που φυτοζωούν με βάναυσα κουτσουρεμένες συντάξεις και επιδόματα. Βομβαρδισμένοι με το αφήγημα του Μνημονιακού Τόξου (ιδίως τα τελευταία τρία χρόνια κατά τη διάρκεια των οποίων ενώθηκαν μαζί του οι φωνές του επίσημου ΣΥΡΙΖΑ), ότι ακόμα και αυτά τα ξεροκόμματα κινδυνεύουν αν υπάρξει νέα ανυπακοή προς τους δανειστές, παγώνουν, εγκλωβίζονται στις Συμπληγάδες της εξαθλίωσης και του φόβου, τον οποίο σιγοντάρει η θλιβερή προσδοκία ενός φιλοδωρήματος τον Δεκέμβρη από τα ματωμένα πλεονάσματα του υπουργείου Οικονομικών.

Οι εξαγριωμένοι αποτελούν την τρίτη κατηγορία. Ο θυμός τους διοχετεύεται διαφορετικά στον καθένα: αποτροπιασμός στον κοινοβουλευτισμό, ροπή προς τον ξενοφοβικό εθνικισμό, συνειδητά επιλεγμένη μοναξιά, ιδιώτευση κ.ο.κ. Πάνω απ’ όλα, ο θυμός τους, ό,τι μορφή και να παίρνει, συνεργεί αρμονικά με την έλλειψη προοπτικής, την απαισιοδοξία, την κατήφεια.

Κάπως έτσι καταλήξαμε με την Ελλάδα διαιρεμένη σε κοινωνικές τάξεις που τις ενώνουν οι χαμηλές προσδοκίες οι οποίες, με τη σειρά τους, αναπαράγουν τη διαδικασία ερημοποίησης – με τους νέους και τους δημιουργικούς, απλά, να μεταναστεύουν.

Οποιος έχει διαβάσει το «1984» του Τζορτζ Οργουελ θα θυμάται το θλιβερό τέλος εκείνης της ιστορίας αντίστασης στον Μεγάλο Αδελφό – θα θυμάται πως η ελπίδα πέθανε στην τελευταία σελίδα του βιβλίου όταν ο αντιστασιακός πρωταγωνιστής ανακάλυψε ότι, τελικά, αγαπούσε τον Μεγάλο Αδελφό. Επειδή όμως στην πραγματική ζωή, ευτυχώς, δεν υπάρχει τελευταία σελίδα, κάποιοι εξ ημών ιδρύσαμε το ΜέΡΑ25 για να εμφυσήσουμε στους πολίτες ξανά Μεγάλες Προσδοκίες και για να τους πούμε ότι η αντίσταση στον Μεγάλο Αδελφό είναι εδώ, είναι ανένδοτη κι είναι πανευρωπαϊκή.

*γραμματέας του ΜέΡΑ25

Is Neoliberalism destroying the world? A. Admati, S. Gindin, P. Mirowski & Y. Varoufakis interviewed by CBC Radio

The Trump administration is largely populated by people from the neoliberal thought collective and they are busily carrying out things that they wanted to do for years.– Philip Mirowski

The term “neoliberalism” is likely more used than understood. But if at its heart it’s the ideology that markets know better than humans, then its ascension into virtually every sector of society is nearly complete. At least that’s the view of economic historian, Philip Mirowski at the University of Notre Dame. For him, the presidency of Donald Trump represents textbook neoliberalism: privatizing education and health care, gutting the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) as well as health and safety, and food safety laws.

“People don’t pay any attention to this because they’re so fascinated by the buffoonery of Trump himself,” Mirowsky says. “The Trump administration is largely populated by people from the neoliberal thought collective and they are busily carrying out things that they wanted to do for years.”

Trump’s government is simply the visible part of the ideological iceberg that is neoliberalism. Brexit, the rise of extreme right-wing nationalism and anti-globalization, the Euro crisis, austerity, consumer debt and economic anxiety — these are all arguably byproducts of neoliberalism’s ideology.

TO LISTEN TO THE HOUR LONG PROGRAM, CLICK HERE

Roots of Neoliberalism

British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and U.S. President Ronald Reagan share a laugh during a break from a session at the Ottawa Summit on July 21, 1981, at Government House in Ottawa. (AP)

Some believe neoliberalism was ushered in with the rise of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan in the 1980s when they promised to roll back the so-called “welfare state” and clip the wings of organized labour. Thatcher and Reagan said government had to get out of the way of business, claiming that regulations, taxes and tariffs were preventing corporations from meeting their potential. Yet the ideology’s roots go much further back than the Reagan-Thatcher moment.

According to Mirowski, one of the world’s leading scholars on the topic, it’s not rooted in the traditional conservatism of Edmund Burke, the 18th-century Anglo-Irish statesman and intellectual, who felt governments must be neutral in guiding the economy. “(Neoliberals) don’t believe in laissez-faire,” explains Mirowski, “and this is the other big mistake that people make. They don’t believe in libertarianism. They don’t believe that markets will just operate wonderfully on their own. That’s why they have to engage in various kinds of political intervention to make the world more like a market society.”

Neoliberalism’s origins begin with Frederick Hayek, an Austrian-born British economist (1899-1992), known most for his 1944 book The Road to Serfdom. Hayek was famous for his opposition to the Keynesian school of economics, which called for massive government intervention during the Great Depression to alleviate the cataclysmic poverty and unemployment that defined the era. Keynesian economics, named after the British economist John Maynard Keynes, held that governments should introduce social programs like unemployment insurance and labour reforms that benefit average workers, and that they should place controls on banks and stock markets.

But Hayek felt that any such efforts to control market forces were pure folly.

Birth of Neoliberalism

Neoliberals believe they have to build a certain kind of government and economy. Their key doctrine is that the market is an information processor more powerful than any human being.– Philip Mirowski

In 1947, Hayek organized a meeting that would change the course of economic history. He invited thirty-nine scholars from ten countries to meet at Mont Pèlerin, on Lake Geneva in the Swiss Alps. This was the beginning of the Mont Pèlerin Society, a group of economists who conceived of the ideological tenets of neoliberalism and whose influence would come to dominate in the coming decades. Many of the attendees later found positions at think tanks in the U.S. and Europe, and especially at the University of Chicago, earning themselves the label the “Chicago Boys”.

Whatever disagreements they may have had, they were united in one central belief, according to Mirowski: “Neoliberals believe they have to build a certain kind of government and economy. Their key doctrine is that the market is an information processor more powerful than any human being.”

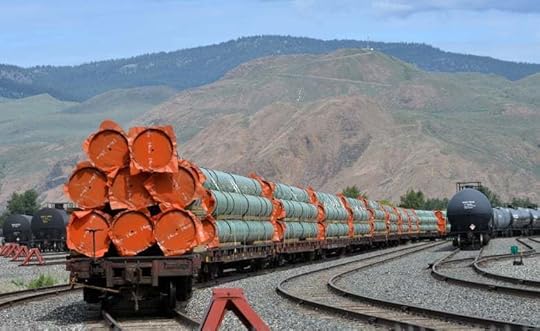

Neoliberals believe government must be involved in the economy, but solely on the side of business and the wealthy. A recent example is Prime Minister Trudeau’s decision to purchase the Trans Mountain pipeline in 2018 on behalf of the oil industry — a move traditional conservatives would never have countenanced.

Steel pipe to be used in the oil pipeline construction of Kinder Morgan Canada’s Trans Mountain Expansion Project sit on rail cars at a stockpile site in Kamloops, British Columbia. The plan to twin the existing 1,150 kilometre-long pipeline has been indefinitely suspended. (Dennis Owen/Reuters)

More general examples are bilateral investment treaties, contained in free trade agreements like NAFTA, which allow corporations to sue governments if local communities impose policies that interfere with their right to make profits. Canada has paid out $160 million to U.S. corporations which challenged public decisions, including ones made on environmental policy.

So is neoliberalism ultimately anti-democratic?

Mirowski thinks so. “They are very suspicious of democracy but that doesn’t mean that they’ll never participate in a democracy,” he remarks. “What they’ll try to do is they’ll try to bend some democratic procedures.” Neoliberals are comfortable “making it way harder to vote,” says Mirowski, “and that’s why you get so much voter suppression in the United States. They want to make it so it’s very hard to pass legislation. And that’s why for them when the Congress doesn’t do very much, that’s a win. They love that.”

In the 1970s, neoliberal economists from University of Chicago school, particularly Milton Friedman, began advising the Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet on how to “liberalize” the Chilean economy. Pinochet’s reforms, including opening the economy to foreign competition, led to widespread poverty and protests, and they in turn helped destabilize his regime.

Rise of Neoliberalism

[It’s] capitalism working without a working class opposition. I think that’s a fairly accurate description of what it is. – Sam Gindin

Another major target of neoliberals are unions, which emerged in the post-war era as powerful counter-balances to the power of corporations.

Sam Gindin, former research director of the Canadian Auto Workers Union (now called Unifor), and adjunct professor of political science at York University, explains the dynamics of neoliberalism: “[It’s] capitalism working without a working class opposition. I think that’s a fairly accurate description of what it is.”

Gindin says neoliberalism destroyed class opposition by “changing labor laws, making it harder to organize. But it especially meant letting unemployment rise.” Gindin had a front row seat to the assault on organized labour, joining the staff of the auto workers’ union in the early 1970s, just as the post-war boom was running out of steam and neoliberalism began replacing Keynesianism.

But the first real shot in this ideological war was the 1981 firing of striking air traffic controllers. Soon corporations were demanding wage concessions and other rollbacks that unions had won. In the UK, there was a bitter strike that went on for more than a year between the Thatcher government and militant mine workers union — which the union lost.

Gindin says labour’s defeat has meant workers have in effect internalized neoliberal values, as they’ve been compelled to compete as individuals in the marketplace. “They change the overtime laws so that you can work more overtime,” he says. “They increase the availability of debt so you can go into debt to solve your problem. These were all problems that you could solve individually. That’s why that kind of individualistic ideology could work, because it was materially the only thing a lot of people saw they could do.”

Fallout of Neoliberalism

But what happens when the neoliberalism recipe is applied to entire countries — do you end up with a debilitated country like Greece?

The neoliberal mantra was utilized in order to [create a] tsunami of capital that came to Greece in the form of loans that created bubbles.– Yanis Varoufakis

Prior to the 2008-2009 credit crisis, Greece had borrowed heavily from bankers and the European Union, despite having a weak economy and very little prospect of paying off its debts.So when their recession struck, the EU and banks wanted their money back, pressuring Greece to sell off state assets like airports, land, and even the national broadcaster, all in return for more loans. The civil service was gutted and government spending chopped. Unemployment rose to a staggering 25 per cent.

“Consider the fact that between 2010 and 2015 we lost more than one fifth of our national income,” Yanis Varoufakis, a former finance minister of Greece, told Ideas. “It was the worst episode in history at least since the Great Depression of the 1930s. You only have to take into consideration the fact that one in two families had no one working. Three and a half million Greeks out of a population of something like six and a half million adults were either unemployed or bankrupt.”

Pensioners waiting outside a closed National Bank branch and hoping to get their pensions, argue with a bank employee (L) in Iraklio on the island of Crete, Greece June 29, 2015. Greeks struggled to adjust to shuttered banks, closed cash machines and a climate of rumours and conspiracy theories on Monday as a breakdown in talks between Athens and its creditors plunged the country deep into crisis. (Stefanos Rapanis/Reuters)

In 2015, the left-wing Syriza party swept to power on an anti-austerity, anti-EU platform. Varoufakis, a charismatic Marxist economist, was appointed finance minister. He immediately challenged the EU and its bankers, demanding debt relief and better terms for loans. The EU and the bankers refused.

In a referendum that year, Greeks voted against further austerity measures. But the prime minister, Alex Tspiras, folded to pressure from the EU, fired Varoufakis and embraced a new package of austerity and privatization. The country has been mired in crisis ever since.

Varoufakis — who has since formed a new political party — argues that “neoliberalism is not an economic model. Neoliberalism is an ideology. Imagine we were in the 1970s in the Soviet Union and we’re talking about the Soviet economy in terms of Marxist ideology. There was no relationship between the policies implemented in the Soviet Union with Marx or Marxism.”

Instead, Varoufakis argues, European bankers embrace neoliberalism only when it suits them. “The neoliberal mantra was utilized in order to [create a] tsunami of capital that came to Greece in the form of loans that created bubbles. They gave most Greeks a false sense of prosperity and, of course, when the bubbles burst, being a deficit country, the burden of adjustment in the form of austerity fell upon the Greeks.”

The loans to Greece were so large, he says, that there is no chance of ever paying them off, leaving Varoufakis with a bleak view of Greece’s future: “Very soon, we’re going to witness the building of splendid facilities for pensioners from all over northern Europe by the sea in the warm climate, while Greek pensioners, and whomever is left of the Greek population, will be eating out of garbage bins.”

Guests in this episode:

Philip Mirowski is a historian and philosopher of economic thought at the University of Notre Dame.

Sam Gindin is the former research director for the Canadian Auto Workers union (now called Unifor) and an adjunct professor of political science at York University, and co-author of “The Making of Global Capitalism: The Political Economy of American Empire, (2012).

Yanis Varoufakis is a Greek politician, economist and author, and former finance minister of Greece

Anat R. Admati is a professor of finance and economics at Stanford University and author of “The Bankers New Clothes: What’s Wrong with Banking and What to do About It, (2013).

ATHENS – As deadlines approach and red lines are redrawn...

ATHENS – As deadlines approach and red lines are redrawn in the United Kingdom’s impending withdrawal from the European Union, it is imperative for the people of Britain to regain democratic control over a process that is opaque and ludicrously irrational. The question is: How?

Democracy can never aspire to being more than a work in progress. Decisions made collectively must constantly be reappraised collectively in the light of new evidence. Yet, in the UK’s current circumstances, nothing would be more poisonous to democracy than revisiting Brexit by means of a second referendum.

Both sides, Leavers and Remainers, feel betrayed. Even though Brexit was meant to restore its sovereignty, Parliament has no real say in a process that will mark Britain for decades to come. The Scots and the people of Northern Ireland are hostages to a distinctly English feud that could do them serious damage. The young feel the old have hijacked their future, while the old feel that their accumulated wisdom and legitimate concerns are being ignored by insiders striking bad deals behind closed doors on behalf of vested interests. In short, British democracy is failing its latest and most stringent test.

September 24, 2018

Η απαραίτητη ρήξη με το 4ο Μνημόνιο και η εκλογική πρόταση του ΜέΡΑ25: Συνέντευξη του Γ. Βαρουφάκη, ΤΑ ΝΕΑ, 22/9/2018

Πώς περιγράφετε τη ρήξη με τους δανειστές που προτείνατε στη συνέντευξή σας στη ΔΕΘ;

Το ΜέΡΑ25 καταθέτει τα βασικά νομοθετήματα που απαιτούνται για να ανακάμψει η χώρα (π.χ. μείωση του ΦΠΑ και του συντελεστή μικρομεσαίων επιχειρήσεων στο 18%). Σημειώνουμε ότι οι δανειστές θα πουν «όχι» εφόσον ερωτηθούν. Θα τα νομοθετήσουμε χωρίς πρότερη συζήτηση στο Eurogroup. Δεν θα προτείνουμε, ούτε θα απειλήσουμε με Grexit. Ομως φοβόμαστε τη σημερινή ερημοποίηση της Ελλάδας πιο πολύ από το Grexit. Αν το Βερολίνο αποφασίσει να προχωρήσει στην αποπομπή μας από το ευρώ, ας το τολμήσει.

Αλήθεια, αν η ρήξη απέτυχε όταν υποτίθεται είχατε και μεγάλο μέρος του κόσμου μαζί σας επί πρώτου κυβερνητικού πενταμήνου ΣΥΡΙΖΑ, πώς θα την επιτύχετε σήμερα;

Κάτι που δεν έγινε ποτέ δεν μπορεί να απέτυχε. Το 2015 ζητήσαμε από τον ελληνικό λαό εντολή: (α) να καταθέσουμε μετριοπαθή πρόταση προς τους δανειστές (τις προτάσεις μου για αναδιάρθρωση χρέους, δραστική μείωση στους φορολογικούς συντελεστές με παράλληλο αλγοριθμικό κυνήγι των φοροφυγάδων, δημόσια εταιρεία διαχείρισης κόκκινων δανείων κλπ.), και (β) να μην υπογράψουμε καμία συμφωνία στο Eurogroup αν δεν εξασφαλιζόταν άμεσα η βιωσιμότητα του χρέους και ο τερματισμός της λιτότητας (δηλαδή πρωτογενή πλεονάσματα κάτω του 1,5% του ΑΕΠ). Ο ελληνικός λαός μάς έδωσε αυτή την εντολή δις: την 25η Ιανουαρίου και την 5η Ιουλίου του 2015. Δυστυχώς, ο κ. Τσίπρας από τα τέλη Απριλίου ενέδωσε ως προς τη λιτότητα και, λίγο μετά, συνθηκολόγησε για το χρέος. Η ρήξη, λοιπόν, δεν έγινε ποτέ και, φυσικά, ακολούθησαν τα «ναι σε όλα». Ρωτάτε πώς θα επιτύχει η ρήξη σήμερα. Απαντώ: Τολμώντας την!

Βιώνουμε ήδη τη μεταμνημονιακή εποχή ή βλέπετε κάτι πιο ζοφερό για την ελληνική οικονομία;

Βιώνουμε το 4ο Μνημόνιο της περιόδου 2018-2032, ενόψει ενός 5ου (2032-2060). Τι σημαίνει Μνημόνιο; Δεν σημαίνει επιτήρηση από τις Βρυξέλλες – όλες οι χώρες της ΕΕ τελούν υπό επιτήρηση. Σημαίνει κάτι άλλο, πολύ συγκεκριμένο. Σημαίνει συνδυασμό: (α) ευκολιών αποπληρωμών του χρέους μας στην τρόικα, οι οποίες όμως επιβαρύνουν το συνολικό χρέος μακροπρόθεσμα, με (β) σκληρή λιτότητα στο διηνεκές (πρωτογενή πλεονάσματα 3,5% μέχρι το 2021 και 2,2% μέχρι το… 2060).

Δηλαδή;

Μια ματιά στη συμφωνία κυβέρνησης Τσίπρα με τους δανειστές επιβεβαιώνει ότι εισήλθαμε στο 4ο Μνημόνιο, το οποίο βέβαια, για προπαγανδιστικούς λόγους, αποφάσισαν – σε μια οργεουλιανή έκρηξη – να ονομάσουν «ενισχυμένη επιτήρηση». Η μόνη διαφορά του 4ου από τα προηγούμενα Μνημόνια είναι ότι οι ευκολίες αποπληρωμών πλέον βασίζονται λιγότερο σε νέα δανεικά και περισσότερο σε αναβολές αποπληρωμών (που όμως τοκίζονται και μεταφέρονται στο μέλλον).

Κατά τη γνώμη σας πού οδεύει ο σημερινός ΣΥΡΙΖΑ; Διεξάγεται μια συζήτηση αν θα αποτελέσει πόλο ενός προοδευτικού μετώπου, ενώ υπάρχει και κουβέντα αν θα είναι μέρος ηγεμονικό μιας νέας Κεντροαριστεράς…

Η πασοκοποίηση του ΣΥΡΙΖΑ έχει ολοκληρωθεί. Το ίδιο και η επί της ουσίας προσχώρησή του στο τέως σοσιαλδημοκρατικό μπλοκ, το οποίο όμως έχει απονομιμοποιηθεί στα μάτια των ψηφοφόρων πανευρωπαϊκά.

Εχετε πολλές επαφές έξω, μιλάτε συχνά και συναντάτε κόσμο σε πολλές χώρες. Το επίδικο σήμερα είναι η μάχη κατά της Ακροδεξιάς; Θα μπαίνατε σε ένα κοινό μέτωπο ως MέΡΑ25 και ως Diem25 με άλλες δυνάμεις;

Δεν έχουμε απλά «επαφές». Εχουμε ήδη συμπράξει σε κοινό, διεθνικό, πανευρωπαϊκό και παγκόσμιο μέτωπο εναντίον της ξενοφοβικής Δεξιάς αλλά και, παράλληλα, εναντίον του αυταρχικού βαθέος κατεστημένου. Για τις ευρωεκλογές το κοινό μέτωπο με έντεκα κόμματα και κινήματα ανά την Ευρώπη είναι γεγονός, και ονομάζεται Ευρωπαϊκή Ανοιξη. Πρόσφατα, σε δημόσια εκδήλωση με τον Τζέρεμι Κόρμπιν, τον αρχηγό του Εργατικού Κόμματος, ανακοινώσαμε την κοινή μας βούληση να πάμε πέραν των ευρωπαϊκών συνόρων δημιουργώντας Προοδευτική Διεθνή. Την περασμένη εβδομάδα, μέσα από τις σελίδες της βρετανικής «Guardian», ανακοινώσαμε με τον Μπέρνι Σάντερς ότι προχωράμε μαζί προς την ίδρυση της Προοδευτικής Διεθνούς, με επόμενο σταθμό κοινή μας εκδήλωση στο Βερμόντ στα τέλη Νοεμβρίου. Οπως βλέπετε, το ΜέΡΑ25 και η πανευρωπαϊκή του ομπρέλα, το DiEM25, συνδημιουργεί το κοινό μέτωπο στο οποίο αναφέρεστε.

Μήπως πριν από τη νέα σας εκλογική κάθοδο, πρέπει να σταθείτε αυτοκριτικά στον ελληνικό λαό για το επτάμηνο της διακυβέρνησης του 2015 και το όλο κόστος των διαπραγματεύσεων;

Οποιος αρνείται την αυτοκριτική είναι επικίνδυνα φανατικός. Ομως, το ερώτημά σας πρέπει να απευθυνθεί κατ” αρχάς σε εκείνους που κατέστρεψαν τη χώρα, δηλαδή στην ολιγαρχία και την τρόικα – όχι στον μόνο υπουργό Οικονομικών που δεν δανείστηκε ούτε ευρώ (ενώ αποπλήρωνε το χρέος), που δεν έκοψε ούτε ένα ευρώ συντάξεων (ενώ βελτίωσε, έστω και λίγο, τα ταμειακά του κράτους), και που τίμησε τη λαϊκή εντολή πλήρως. Κόντρα στις μανιώδεις προσπάθειες του μνημονιακού τόξου, να μεταθέσουν το δικό τους κόστος σε εκείνους που τους είπαν «όχι», η αυτοκριτική μου είναι σαφής: Δεν έπρεπε να εμπιστευτώ τον Αλέξη Τσίπρα. Και δεν έπρεπε να δείξω καλή πίστη συμφωνώντας με τους δανειστές την επέκταση της δανειακής συμφωνίας.

Θα κατέβετε στις εθνικές εκλογές ή μόνο στις ευρωεκλογές και με ποιο σύνθημα;

Θα κατέβουμε στις εθνικές και στις ευρωεκλογές. Τα συνθήματα είναι ξεπερασμένα. Εμείς θα βασιστούμε στο ολοκληρωμένο μας πρόγραμμα, τόσο για την Ελλάδα όσο και για την Ευρώπη, που αποτελεί προαπαιτούμενο ώστε να πάψει η Ελλάδα να ασφυκτιά σε μια Ευρώπη που αποδομείται.

http://www.tanea.gr/print/2018/09/22/...

Yanis Varoufakis's Blog

- Yanis Varoufakis's profile

- 2451 followers