Yanis Varoufakis's Blog, page 17

October 6, 2023

Interviewed by PoliticsJOE on my TECHNOFEUDALISM

The post Interviewed by PoliticsJOE on my TECHNOFEUDALISM appeared first on Yanis Varoufakis.

Channel 4’s Krishnan Guru-Murthy interviews me on my TECHNOFEUDALISM

The post Channel 4’s Krishnan Guru-Murthy interviews me on my TECHNOFEUDALISM appeared first on Yanis Varoufakis.

October 5, 2023

Στο ΚΟΝΤΡΑ-NEWS με τον Πάνο Χαρίτο – video

The post Στο ΚΟΝΤΡΑ-NEWS με τον Πάνο Χαρίτο – video appeared first on Yanis Varoufakis.

UNHERD interviews me on TECHNOFEUDALISM

For the UNHERD site, click here.

You can watch the full interview above.

The post UNHERD interviews me on TECHNOFEUDALISM appeared first on Yanis Varoufakis.

October 4, 2023

Long interview with Carole Cadwalladr, for the Observer/Guardian, on my Technofeudalism

eek to one part an episode of BBC series Holiday

from the Jill Dando era: blue skies, blue sea, maybe some plate breaking in a jolly taverna. What I’m not expecting is a wall of flames rippling across a hillside next to the highway from the airport and a plume of black smoke billowing across the carriageway.

Because even a modernist villa on a hillside on the island of Aegina – a fast ferry ride from the port of Piraeus and the summer bolthole of chic Athenians – is not the sanctuary from the modern world that it might once have been. The house is where Varoufakis and his wife, landscape artist Danae Stratou, live, year round since the pandemic, but in August 2023 at the end of a summer of heatwaves and extreme weather conditions across the world, it feels more than a little apocalyptic. The sun is a dim orange orb struggling to shine through a haze of smoke while a shower of fine ash falls invisibly from the sky. A month later, two years’ worth of rain will fall in a single day in northern Greece, causing a biblical deluge and never-before-seen levels of flooding.That the end of the world feels just a little bit nearer here than it does in some places may not be coincidental to Varoufakis’s having written a new book called Technofeudalism: What Killed Capitalism. Nor that the book comes to the conclusion that capitalism has been replaced with something even worse. Not the glorious socialist revolution that his hero Marx foresaw. Nor some new mutation of capitalism such as the one detailed by Shoshana Zuboff in her surprise 2019 bestseller, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism . We’re now in servitude, Varoufakis argues, to the fiefdoms of our new global masters, Lord Zuckerberg of Facelandia and Sir Musk of the rotten borough of X.When I arrive by taxi at the bottom of the dirt track up to his house, Varoufakis is there to meet me, folded inside a zippy red Mini. “I’m usually on my motorbike,” he says, and describes his “pristine commute” at speed via land and sea that gets him to the Greek parliament in just over an hour. It should also be mentioned that the motorbike and leather jacket didn’t hurt his image as a lefty bad boy, taking on the grey men of global capitalism. To put Varoufakis into context, he was the Greek equivalent of John McDonnell (a close friend) if Jeremy Corbyn (another close friend) had actually been voted into power and if John McDonnell had, in this scenario, been played by George Clooney.[image error]With Aléxis Tsípras, the former prime minister of Greece in February 2015. Photograph: Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

Because in 2015, at the height of the Greek debt crisis, Varoufakis was catapulted from academic obscurity to minister of finance. He said – loudly and repeatedly – that the punitive terms the banks wanted to impose on Greece would lead to catastrophic austerity. A majority of Greeks voted to back him, and for a short time his strategy of simply refusing to agree to the IMF and EU’s terms led to a tense standoff. Right until the moment prime minister Aléxis Tsípras, the man who appointed him, accepted them. Either the only possible action to prevent the country going bankrupt, or a treacherous betrayal, depending on who you choose to believe.

The Financial Times labelled Varoufakis “the most irritating man in the room” during the negotiations, so it’s not exactly a surprise to learn that Technofeudalism is a polemic, a controversialist’s take. And although in 2023 there’s nothing particularly novel or special about hating on tech – hating on Elon Musk is the only rational response to the situation in which we’ve found ourselves – nevertheless, Technofeudalism feels like an important new book.It’s a big-picture hypothesis rooted in a historical account of how capitalism came into being that describes what is happening in terms of an epochal, once-in-a-millennium shift. In some ways, it’s a relief to have a politician – any politician – talking about this stuff. Because in Varoufakis’s telling, this isn’t just new technology. This is the world grappling with an entirely new economic system and therefore political power.“Imagine the following scene straight out of the science fiction storybook,” he writes. “You are beamed into a town full of people going about their business, trading in gadgets, clothes, shoes, books, songs, games and movies. At first everything looks normal. Until you begin to notice something odd. It turns out all the shops, indeed every building, belongs to a chap called Jeff. What’s more, everyone walks down different streets, and sees different stores because everything is intermediated by his algorithm… an algorithm that dances to Jeff’s tune.”It might look like a market, but Varoufakis says it’s anything but. Jeff (Bezos, the owner of Amazon) doesn’t produce capital, he argues. He charges rent. Which isn’t capitalism, it’s feudalism. And us? We’re the serfs. “Cloud serfs”, so lacking in class consciousness that we don’t even realise that the tweeting and posting that we’re doing is actually building value in these companies.We’re in his airy open-plan living room where his wife intermittently appears offering water, coffee and snacks and shooing away a large, enthusiastically affectionate labrador. “He’s totally in love with Yanis,” she says. Stratou and Varoufakis are a striking couple, as glamorous as their house, a cool, luminous space featuring poured concrete and big glass windows overlooking a perfect rectangle of blue pool.“I have no issues with luxury,” he says at one point, which is just as well because the entire scene would give the Daily Mail a conniption, especially since Aegina seems to be Greece’s equivalent of Martha’s Vineyard, home to a highly networked artistic and political elite. Tsípras, the former prime minister and Varoufakis’s nemesis, used to live next door. “He was on the next hill. There’s a symbolically important ravine between us,” he says.[image error]Jeff Bezos doesn’t produce capital, he argues. He charges rent. Which isn’t capitalism, it’s feudalism

Varoufakis and his wife, Danae Stratou, at a concert in Athens, 2015. Photograph: Angelos Tzortzinis/AFP/Getty Images

And although Stratou is an accomplished artist, she’s also cursed with some niche internet fame. At the height of Varoufakis’s notoriety, a newspaper report claimed that she was the inspiration behind Pulp’s hit song Common People. “She came from Greece she had a thirst for knowledge,” runs the first line; “She studied sculpture at St Martin’s College,” is the second. As Stratou did, at the same time as Jarvis Cocker was there, though she gives me a “No comment!” when I inevitably bring it up. “It’s the first thing you see when you Google my name,” she says, with irritation, and “who knows where artists find their inspiration?” though Varoufakis seems to be enjoying my line of questioning just a little too much.Technofeudalism takes the form of a letter addressed to Varoufakis’s recently deceased father, Georgios. A Greek-Egyptian communist, he emigrated to Greece in the 1940s, in the middle of the country’s civil war, and was sentenced to five years’ “political re-education” for refusing to denounce his communism. He rose to become chairman of Greece’s biggest steel company. What Varoufakis valued most about him, he says in the book, was his father’s ability to see the “dual nature” of things.Technofeudalism is also partly a sequel to his previous book, Talking to My Daughter About the Economy , addressed to his then 11-year-old daughter Xenia, in which he tried to answer the question of why there’s so much inequality. Though even as he was writing it, he says, he felt end-of-an-era qualms about the future prospects of capitalism.“Even before it was published in 2017, I was feeling uneasy,” he says in the first chapter of Technofeudalism. “Between finishing the manuscript and holding the published book in my hands, it felt as if it were the 1840s and I was about to publish a book on feudalism; or, even worse, like waiting for a book on Soviet central planning to see the light of day in late 1989.” Was the entire concept of capitalism already out of date, he wondered?On the living room bookshelf, I spot a copy of Zucked by businessman Roger McNamee, one of the first investors in Facebook, who was responsible for introducing Mark Zuckerberg to Sheryl Sandberg. “That’s a great book,” says Varoufakis. I tell him that McNamee broadly agrees with his new ideas. I’d messaged a bunch of people to ask them what they would ask Varoufakis, including McNamee, and precised the book to him – that two pivotal events have transformed the global economy: 1) the privatisation of the internet by America and China’s big tech companies; and 2) western governments’ and central banks’ responses to the 2008 great financial crisis, when they unleashed a tidal wave of cash.I read him McNamee’s reply: “I buy the basic thesis. The US kept interest rates at near zero from 2009 to 2022. This encouraged business models that promised world-changing outcomes, even if they were completely unrealistic and/or hostile to the public interest (eg the gig economy, self-driving cars, crypto, metaverse, AI). This came at a time of no regulation of tech and an accepted culture in business that said executives should maximise shareholder value at expense of everything else (eg democracy, public health, public safety)… had rates been at 5% the past 14 years, I doubt very much that the gig economy, self-driving cars, crypto, metaverse or AI would have gotten even 10% as much funding.”It’s pretty remarkable, I point out, that a Marxist and a venture capitalist have reached the same economic conclusions. But then there are more and more people – outside politics – trying to understand these new power structures. Shoshana Zuboff tells me that she “explicitly rejects labels like technofeudalism because technology is not the independent variable nor are we feudal serfs”. But she also says that the argument has some similarities to one of her latest papers: “In big tech we face a totalising power that in key respects disqualifies itself from being understood as capitalism, but rather as a wholly new form of governance by the few over the many.”

When I message Mariana Mazzucato, another charismatic and influential economist, but one who, unlike Varoufakis, has been embraced by governments and financial institutions, her response suggests that some of Varoufakis’s ideas are not that new. She herself published on an adjacent concept, “algorithmic rents” (the idea that tech companies capture attention and resell it rather than creating long-term value) in 2018.But perhaps traditional distinctions between left and right don’t make sense any more. The right, Varoufakis says, “thinks of capitalism as like a natural system, a bit like the atmosphere”. Whereas the left “think of themselves as people created by the universe in order to bring socialism over capitalism. I am telling you: you know what, you missed it. You missed it. Somebody killed capitalism. We have something worse.”The early internet, he says, has given way to a privatised digital landscape in which gatekeepers “charge rent… The people we think of as capitalists are just a vassal class now. If you’re producing stuff now, you’re done. You’re finished. You cannot become the ruler of the world any more.”I wonder aloud if Varoufakis’s big-picture approach stems from the fact that authoritarianism – and the radical politics it produced in his own family – is still near-history in Greece. When he was six, the secret police raided his house and arrested his father. Do you remember it, I ask. “My God, yes, you don’t forget a thing like that. For two weeks, we didn’t know where he was.” And when Varoufakis started becoming interested in politics – this was when a military junta still ruled Greece – and he was picked up by the police as a teenager, his parents were adamant: he was going to Britain.As well as being a passionate European and an internationalist, he’s also an anglophile who writes in English and studied at Essex University, where he joined the Communist party of Great Britain. He is credited with persuading Jeremy Corbyn to back remain in the referendum and campaigned around the country for it. And when I ask him what his advice would be to Keir Starmer, he says: “He should try to do something he’s incapable of: being honest. He should say: ‘You know what? Brexit was a disaster. I want to bring back the UK into the EU. I’m not saying that I’m going to do it any time soon. But I’m going to work toward it. In the meantime, I will make Brexit work by doing A B C and D.’” (Coincidentally, Starmer said last week that he will seek to remake the deal with the EU for closer trade ties.)“He’s now adopting austerity. There’s no plan for the NHS to reverse the privatisation from within. You know, this is the one thing I miss about Thatcher. She was a conviction politician, right?”I say that the closest political analogues to Varoufakis in the UK might be Boris Johnson and Nigel Farage. “What?” he says.“You’re all anti-politicians,” I say.I ask him what his advice would be to Keir Starmer, he says: ‘He should try being honest. He should say: “You know what? Brexit was a disaster”’

“The fact you have a point is a source of sorrow,” he says. “Because I’m anti-establishment. But it’s true, you have these people taking over the anti-establishment mantle in a way that is functional to the interests of the establishment. I see no difference between Orbán, the Polish government, Trump, Farage, Johnson, Mussolini.”It formed part of his pitch to the EU at the height of the Greek debt crisis. “I told Wolfgang Schäuble [the former German finance minister]: ‘We’re both democrats. We believe in the Enlightenment.’ I said: ‘Give us austerity and we’ll turn to fascism.’ And I very much fear that is turning out to be the case.” The big winners in this year’s Greek elections were “The Spartans, they are the mutation of Golden Dawn [a banned Greek neo-Nazi party]. The Greek Solution. You only have to hear the names, right? And Niki, or Victory.”It’s a particularly sore point. Because these parties’ gains came at the expense of Varoufakis. After his stint as finance minister, he’d set up his own party, which won nine seats in the 2019 election. This year, it lost them all. “We don’t really know what happened. We were polling at 21% among young people.” The spring has gone out of his step, he admits. He’s been holed up in Aegina since, pondering his next move. Still, even with the ash raining from the skies, it’s not a bad place to be.This is a bracing conversation, which includes half an hour on Russia and Ukraine during which I politely disagree with everything he says. His views on the conflict are practically indistinguishable from Nigel Farage’s, rehearsing the same far right-meets-far left “horseshoe” rhetoric about doing a deal with Putin, and Crimea not really being Ukraine. But on the subject of technofeudalism, I could listen to him all day.Xenia, his daughter, wanders in. “Are you guys still going? I’ve had three naps since you got here.” A student in Australia, she’s been taking her classes online from Aegina and has been up half the night. The breakdown of his relationship with his first wife, Australian academic Margarite Poulos, and her decision to return to Australia with Xenia was, Varoufakis has written, one of the darkest periods of his life. Meeting Stratou is what saved him from “near oblivion”.In Technofeudalism, Varoufakis retells the story of the minotaur. It’s a myth that he returns to often. In his prescription, the minotaur is the global financial system. In the myth, the beast is eventually slain by an Athenian prince. This prince of Athens didn’t manage to bring down capitalism. But as he and Stratou walk me down to the taxi under an unnatural orange sunset, it strikes me that the beast may yet turn out to have mortally wounded itself, all on its own.Technofeudalism: What Killed Capitalism by Yanis Varoufakis is published by Bodley Head (£22). To support the Guardian and Observer order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may applyHis views on the conflict in Ukraine are practically indistinguishable from Nigel Farage’s

The post Long interview with Carole Cadwalladr, for the Observer/Guardian, on my Technofeudalism appeared first on Yanis Varoufakis.

September 28, 2023

The MONTHLY reviews my TECHNOFEUDALISM

The post The MONTHLY reviews my TECHNOFEUDALISM appeared first on Yanis Varoufakis.

September 27, 2023

Christine Lagarde’s Gifts to Populists – Project Syndicate

For Project Syndicate’s site, where this article was originally published, click here.

The post Christine Lagarde’s Gifts to Populists – Project Syndicate appeared first on Yanis Varoufakis.

September 26, 2023

The NATION (UAE) reviews TECHNOFEUDALISM

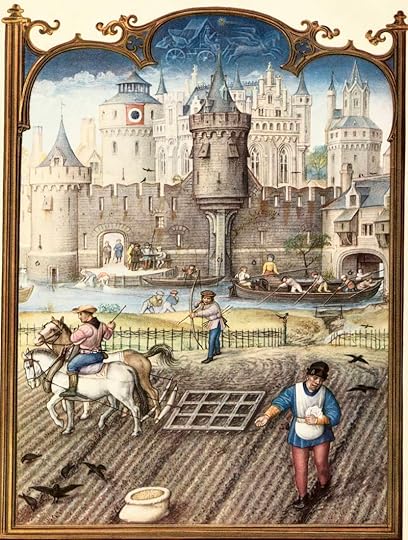

Painting from Breviarium Grimani depicts late 15th-century peasants working outside a town. Getty ImagesThe 2008 financial crisis “massively” accelerated the advent of technofeudalism. Varoufakis says the crisis became “stabilised” by printing money, but never really went away, terming it “socialism for the bankers, and austerity for everybody else”. The central bank’s continued intervention in the markets since 2008 has been popular among the very rich: “It was like having an ATM in their living room, keeps churning money out, without them being charged, that is what it was. At the very same time, in order to prevent inflation, they practised austerity on the majority of the people.”Modern serfdomVaroufakis stresses certain key distinctions between historic feudalism and modern technofeudalim. For one, unlike feudal lords, entrepreneurs such as Mark Zuckerberg worked hard to build their wealth, rather than being born “with a silver spoon in their mouth”. At the same time, he argues, unlike Uber and Deliveroo drivers or Amazon warehouse workers, 16th-century peasants were at least out in the clean air.“They had their own culture, they had their own access to the land, they could grow their own food in addition to what the lord took. So it is not necessarily an improvement, what you have now,” he says.

Painting from Breviarium Grimani depicts late 15th-century peasants working outside a town. Getty ImagesThe 2008 financial crisis “massively” accelerated the advent of technofeudalism. Varoufakis says the crisis became “stabilised” by printing money, but never really went away, terming it “socialism for the bankers, and austerity for everybody else”. The central bank’s continued intervention in the markets since 2008 has been popular among the very rich: “It was like having an ATM in their living room, keeps churning money out, without them being charged, that is what it was. At the very same time, in order to prevent inflation, they practised austerity on the majority of the people.”Modern serfdomVaroufakis stresses certain key distinctions between historic feudalism and modern technofeudalim. For one, unlike feudal lords, entrepreneurs such as Mark Zuckerberg worked hard to build their wealth, rather than being born “with a silver spoon in their mouth”. At the same time, he argues, unlike Uber and Deliveroo drivers or Amazon warehouse workers, 16th-century peasants were at least out in the clean air.“They had their own culture, they had their own access to the land, they could grow their own food in addition to what the lord took. So it is not necessarily an improvement, what you have now,” he says.

Varoufakis says ‘capital has mutated into cloud capital’, as typified by firms like Amazon. PA

What about users who now get paid for their content on YouTube, or the recent monetisation introduced by X, formerly Twitter?“Feudalism is not all bad. There were market towns, there was a lot of trading, I mean think of the fantastic artworks that came out of feudalism. There were artisans who got paid, Michelangelo got very well paid by the feudal lords in order to do his masterpieces. That doesn’t mean it wasn’t feudalism.”Would large cloud-firms be directly hit if the central banks stop injecting money into the markets? “Well, I think history has already answered that because once the pandemic started waning, we had inflation,” he says, pointing out that for the first time since 2008, some of the printed money went to the masses during the lockdown “to keep them alive”.But inflation and the Ukraine war made matters worse, and central banks stopped printing money and increased interest rates.

Yanis Varoufakis’s latest book, Technofeudalism: What Killed Capitalism. Photo: Bodley Head

“Then Bezos lost a third of his wealth, Zuckerberg lost 60 per cent of his wealth overnight. But meanwhile they had already built up their cloud capital, they had the machinery, it was in place. We had paid for it, and they continued to extract rents from that.” The central banks also got really very “panicky”, he says, “from printing money to not printing money, suddenly all those banks started failing in the United States, Italy nearly went bankrupt. So behind the scenes they started printing again, to prevent insolvencies.”‘My politicisation came early’It was Varoufakis’s father who introduced him to capitalism at a very young age. A metallurgist who wrote a lot about ancient technologies, he was a “monumental influence” on him, along with other family members. The elder Varoufakis was born and raised in Cairo, Egypt, before moving to Greece in the 1940s. While a student at the University of Athens he was arrested by the secret police and spent several years imprisoned for refusing to sign a declaration denouncing communism.“My father was imprisoned in the late 1940s. Then he got out, struggled, managed to make a life for himself. Then when I was six, in 1967 we had a coup d’etat, right-wing dictatorship. My father was arrested again, just because he had a record with the police, so they picked him up. Because he was on the list.”

Yanis Varoufakis, pictured after his resignation as Greek finance minister in 2015, says his father introduced him to capitalism at an early age. AP

Then his maternal uncle, a businessman and “quite right wing”, turned against the regime and was tortured and imprisoned. As a young boy, Varoufakis found himself in and out of prison visiting members of his family. “That was a good way of starting early, when it comes to trying to understand what on Earth is going on here. My politicisation came early, but I have to say that these were very happy years.”He recalls it being “fascinating” going to prison. “My father was very angry with me for not being sad. But I thought it was an adventure. My father was a very strange man, in the nicest possible way. He was the opposite of a fanatic. He always managed to see the weaknesses, demerits, and the failings of his own side.”Although his father was on the left, Varoufakis recalls he was very critical of it. “In the 1970s, when he was still voting for the Communist Party, he said: ‘You know what Yanis, if we had won the civil war, I would be in the same prison with different guards. So beware of that. Our side are not angels.’ This capacity to be nuanced, and see both sides of the story, on whatever matter, is always very important. And he taught me that.”For The Nation’s site, click here.

The post The NATION (UAE) reviews TECHNOFEUDALISM appeared first on Yanis Varoufakis.

September 14, 2023

Bill Black and Yanis Varoufakis discussing corruption in finance – video

The post Bill Black and Yanis Varoufakis discussing corruption in finance – video appeared first on Yanis Varoufakis.

Why can’t the EU power ahead with green subsidies like Biden’s? It isn’t just political procrastination – THE GUARDIAN

For The Guardian’s site, where this op-ed was originally published, please click here.

The post Why can’t the EU power ahead with green subsidies like Biden’s? It isn’t just political procrastination – THE GUARDIAN appeared first on Yanis Varoufakis.

Yanis Varoufakis's Blog

- Yanis Varoufakis's profile

- 2447 followers