Adam Heine's Blog

November 18, 2025

Painting a Scene in the Reader's Mind

A common problem I come across when editing is something like the example below. As you read, try to imagine the scene, paying attention to how it changes in your mind:

"I really thought it would be harder than this," Donny said.

"Well, sure!" Amanda took a sip of her coffee. "People like you."

"You said that before, but I didn't believe it." Donny picked up the mug after the server refilled it. He passed it back to Frieda—she had passed it to him because the server was too far away.

Frieda reached down to grab her mug. "I don't know. People are still staring."

"What do you expect," Leo said, wiping the spill with his napkin. "We're giant talking turtles."

What's happening here? New characters appear without warning alongside new details about their environment. The reader has to jump back and forth, rereading parts in order to accurately imagine what's happening in the scene. It's draining for the reader, annoying even (and I'm sorry to have inflicted you with it to make a point).

When you're writing a scene, you're painting an image in the reader's mind. How and when you paint in the details matters. In a first draft, you're likely to make up details as you think of them, and that's fine, but when you go back to revise, you need the scene to read as though you had all those details worked out ahead of time.

Here are some tips to do that:

Ground the reader in the sceneWatch for confusing usage of the definite articleDescribe actions in chronological orderGround the Reader in the Scene

I talk about this in more detail here, but the simplest form of the idea is this: Set the scene before anything happens within that scene.

That's an oversimplification of course. I'm sure it might get old to spend a paragraph or two describing every single scene every time it changes. But in general, it's best to err on the side of clarity. A confused reader is going to stop reading.

To fix our example above, we might add this paragraph at the top of the scene:

Donny and Leo met their friends at Joe's Cafe—during the day, in public. Amanda sat at one of the outdoor tables wearing a light summer dress. The weather had turned cold already, but it didn't seem to bother her. She loved the chill in the air and the smell of crisp, fallen leaves. Frieda was up on a ladder, coffee in-hand, as she helped old Joe out by hanging a new sign above the door.

Customers and passersby kept glancing their way, but it wasn't as bad as any of them had expected. A few folks even smiled and waved.

This, by itself, solves nearly all of our problems. It sets the scene, describing who is there, where they are, and what they're doing as well as providing a few visuals and other sensory images to really place the reader in the moment. Now, when the action happens, the reader almost never has to revise their mental image of the scene. They just live in the story and enjoy it.

But we haven't fixed everything....

Confusing Usage of "The"

This seems like such a simple thing. Didn't we learn this in elementary school? But I still see it all the time—not because writers didn't learn grammar, but because it's hard to remember what you did and did not put on the page yet. There's always more in the author's head than what gets written down.

In the example above, we have the phrase "wiping the spill with his napkin." But what spill? When did it happen? It's confusing and possibly frustrating for the reader, making them feel like they missed something.

Fortunately, it's an easy fix. You can either change "the" to "a" or, if that still isn't clear, just describe the thing that's happening before referring to it with the definite article:

Frieda reached down to grab her coffee, spilling a bit in the process.

Describe Events in Chronological Order

This is a smaller problem but equally important to catch. When two events occur, describe them in the order that they happen, and when one event causes another, describe the cause before the effect. For example:

CAUSE: Frieda is too far away from the server.EFFECT: She passes her mug to Donny to get it filled.

CAUSE: The server refilled Frieda's mug.EFFECT: Donny picked it up and passed it back.

Keep these events in order, and your readers will thank you:

A server arrived. Frieda was too far away, so she passed her mug down to Donny.

Donny held the mug out toward the server until it was refilled.

Putting It All Together

Now, read and imagine the scene below, comparing how you felt the first time with now:

Donny and Leo met their friends at Joe's Cafe—during the day, in public. Amanda sat at one of the outdoor tables wearing a light summer dress. The weather had turned cold already, but it didn't seem to bother her. She loved the chill in the air and the smell of crisp, fallen leaves. Frieda was up on a ladder, coffee in-hand, as she helped old Joe out by hanging a new sign above the door.

Customers and passersby kept glancing their way, but it wasn't as bad as any of them had expected. A few folks even smiled and waved.

"I really thought it would be harder than this," Donny said.

"Well, sure!" Amanda took a sip of her coffee. "People like you."

A server arrived. Frieda was too far away, so she passed her mug down to Donny.

Donny held the mug out toward the server until it was refilled. "You said that before, but I didn't believe it.""I don't know." Frieda reached down to grab her coffee and spilled a bit in the process. "People are still staring."

"What do you expect," Leo said, wiping the spill with his napkin. "We're giant talking turtles."

Of course, there are still things missing. We haven't shown a lot about how Donny and Leo feel during this whole conversation, and that's equally critical. We'll talk about that more in a later post, but for now, this is a passable scene that paints a logical picture and doesn't force the reader to revise the image in their head.

(Well, not any more than is necessary at least. They are giant talking turtles, after all.)

October 26, 2025

Leaning in to Joy

If you're immersed in popular culture, you probably know Marie Kondo. I myself am only lampreyed on to most popular culture, but I still absorbed her basic tenet of ridding oneself of everything except things that spark joy.

I'm not really one for decluttering. I'm not terribly messy—actually, the areas I spend my most time in are aggressively organized—but I am a hereditary pack rat, and I will commit crimes before getting rid of some of my beloved junk.

But my time... well, that could use some decluttering.

I've tried rigorous schedules and journaling to track my time. But schedules are impossible with a family as large and chaotic as mine, and while journaling was helpful to gather information, it also fed the part of me that needs to be perfect. Trying to fix it felt like pressure.

Although therapy has helped me vastly improve how I deal with that pressure, I'm also a learning a new trick. You see, schedules and journaling were often about avoiding things I don't want to do.

But what if I just lean into the things I like.

It's basically the Marie Kondo method, but in reverse and applied to my time. What activities give me joy? Well, let's do more of those! It's not that scrolling social media is bad (or makes me a bad person), it's that reading books makes me feel good! And watching TV with my kids! And playing Silksong!

I'm also discovering that I really, really like playing tabletop RPGs. I actually think they might be my favorite form of game. (That's saying a lot for someone who used to think they sucked at improv and who gets nervous every time they run a session!)

The point is, what if instead of being afraid of the "bad" things, I chose to do more of the good?

The more I do this, the more I find that the joy I get from these activities will even carry me through periods where I don't get that joy—tedium from work, boredom on a long drive, even a brief period spent doomscrolling... The guilt of these has less claim over me when I feel good about how I spent the rest of my time. (And it turns out that joy is, you know, a great way to fight fascism.)

So, where do you find joy? How has seeking it out affected your own life?

October 12, 2025

The Algorithm Trap

There was a time when an infinite spool of information seemed like the coolest idea humanity had ever come up with. And honestly, it might be. I mean, through Google-fu alone, I've learned a ton more than anyone ever taught me about church history, quantum mechanics, tarot cards, or con-artist schemes (to name just a few).

Even social media can be pretty cool. We can connect with folks we might otherwise have never talked to again, make friends with people who share our nichest of hobbies, and even find unexpected but needed work.

The problem is the algorithms. The endless scroll. In the past, we chose who we followed and what we were interested in seeing, but then social media platforms began feeding us what they thought we wanted... or really what they wanted us to want. There's some merit in this too (discoverability being the main one), but there are a lot of downsides.

And personally, I hate it.

Here's the thing. We are evolutionarily designed such that exclusion and loneliness cause us actual, physical pain, and social media connects us to the largest community humanity has ever created. Heck, part of the dopamine we get from scrolling is a feeling of belonging and being informed and included.

But it's a trap. Because the algorithms don't actually give us the things our brains expect and need from real community. The endless scroll doesn't support us or validate us or feed us or help us survive. Dopamine tells us we're being fed, but we're actually being fed upon.

There is value in social media communities, and for some of us, our financial survival actually does depend on being connected, but when we're scrolling the algorithm, what are we actually gaining from it? Are the benefits worth the deep, deep costs of anxiety, depression, and increased division?

I don't think they are, at least not for me, and I've been trying to inoculate myself against scrolling for a long time. Here are some things that help:

Check the news in one trusted source (preferably one that aggregates multiple sources).Choose who to follow and seek out their posts.Use social media lists to focus on the content you want.Watch videos mainly from channels you subscribe to.Hang out in smaller communities, like forums or Discord servers devoted to topics you have a personal interest in, with people you actually enjoy talking to.Make plans with real people to do IRL things.If you must feed from the algorithm, set a time or criteria for when you'll stop.There is one common thread through all of these: CHOICE. Where the algorithms betray us is when we stop thinking, pick up our phone by reflex, open an app by muscle memory, check a notification and realize we're still scrolling an hour later.It's very hard, because our minds have been hacked, and we're actively working against our own evolution to unhack them. But it can be done, even if it means cutting back, deleting certain apps, or, for some folks, even getting off social media entirely.

And maybe there will come a day when we no longer want endless useless content, when the idea of 24-hour news channels sounds ridiculous, when monetizing our attention requires quality content instead of quantity.

Maybe if enough of us start choosing what we consume, then eventually, that's what they'll have to give us.

September 28, 2025

I Have to Want to Write It

Ever since I dusted this thing off, I've been trying to figure out what it is and what it needs to be.

I need it to be a place potential clients can find me. (It has definitely worked for that.)I want it to be a place where people can find writing advice. (It does that... for some folks.)I need it to be a place bots crawl so my name comes up in search engines. (It definitely is that.)I want it to be something I enjoy creating. (That's been... harder.)In the last 15 months, what the blog has been most effective for is reminding Google and Bing and ChatGPT and all the other automatons that I exist. Based on what my clients tell me, they connect my name to concepts like editing, writing, game development, science fiction, fantasy, and genre-blending, which is fantastic. (They also think I do graphic novels? I mean, sure, I'll take it, but friendly reminder that AI will always hallucinate).Funny thing is I don't need to write much to get the automatons on my side. They just want to see recent content with the right keywords. That's easy.

It's also dumb. I hate writing content for content's sake.

As far as what I want this to be, I know people are reading, but outside of the few comments you all leave (and thank you SO MUCH to everyone who ever leaves one!), it's hard to tell who's reading and what they like. I want this to be a place for writing advice, and people are definitely reading those posts, but the posts that get the biggest response are often posts about, well... me.

So today, I was interrogating that part of me that's afraid to write. It's afraid that maybe nobody wants to read my writing advice or thoughts on world-building, but I realized something very important:

It doesn't matter if anyone wants to read it.

I have to want to write it.

What will that mean moving forward? Who knows! The blog has always been me, just with varying filters. But I think mostly this will mean less pressure on myself to write something specific for imaginary audiences. I'm gonna write what I want to write.

Heck, it's not like the automatons will care.

September 14, 2025

Goals, Motivations, and Stakes

One of the most common points of feedback I give to my clients is about goals, motivations, and stakes: in every chapter and every scene, the reader has to know what they are. Let me show you why.

First, a quick definition of terms:

Goal: What the character wants to accomplish or what they're trying to doMotivation: Why the character wants itStakes: What happens if the character succeeds (or what happens if they fail)These are the beating heart of fiction. Without them, you might have exciting things happening, but there will be no meaning behind it. The reader will be be bored—possibly without even knowing why.As an example, let's take the tropey in which we start a novel with the protagonist running through a dark forest (often used because we're taught to begin our novels in the middle of the action):

Jann pushed through the trees, heart pounding, each breath burning in her lungs. A branch slapped her from the darkness, nearly knocking her down. She shoved it out of her way and kept running—always running.

Exciting? Maybe, but we don't know anything about Jann or why she's in the forest let alone why she's running. We're starting in the middle of the action, but without these whys, it's difficult for the reader to care.

Compare that with this:

Jann pushed through the trees, heart pounding, each breath burning in her lungs. She had to find a way out, had to escape. A branch slapped her in the darkness, but it didn't matter. She had to keep running.

Now we have a goal: escape. Even with this small (predictable) change, there's a feeling of connection with this character that wasn't present in the first example. We know her a little more, and we want what she wants.

And we can take it further:

Jann pushed through the trees, heart pounding, each breath burning in her lungs. She had to find a way out, to escape whatever it was that chased her in the darkness. She'd only caught a glimpse of it, but that had been enough. Sheer terror did the rest. She could hear it breathing behind her, lurching through the trees in its search for her.

Here, we have added motivation. Why does she want to escape? Because something is chasing her. Because she's afraid. We're starting to paint the contours of what's going on, enabling the reader to immerse themselves in the action and to feel what she feels. The reader's beginning to lean in now, hoping she makes it.

Let's do one more...

Jann pushed through the trees, heart pounding, each breath burning in her lungs. She had to find a way out, to escape whatever it was that chased her in the darkness. She'd only caught a glimpse of it, but that had been enough. Sheer terror did the rest. She could hear it breathing behind her, lurching through the trees in its search for her.

It wanted the vial she'd stolen. But that vial was her son's only hope. If she didn't get to him in time, the disease would steal him from her forever.

Jann wasn't about to let that happen—slavering forest monster or no.

Now there are stakes. Jann isn't just running for her life; she's running to save her son, and if she doesn't succeed, she'll lose him forever. With this, the reader now has a reason to root for her and to find out what happens next—will she make it in time?

These three elements are absolutely vital to draw your reader in. The reader has to know what they are.

They'll change from scene to scene. For example, maybe Jann does escape the forest, but now she has to sneak into a hospital (because she's a fugitive or something, I dunno). Or maybe she gets the vial to her son but then learns that it has unexpected side effects or that the slavering forest monster is after him now instead of her.

Characters' goals, motivations, and stakes will change over time, but it is critical that the reader knows what they are in every scene. What is the POV character trying to accomplish? Why? What happens if they don't?

Clearly convey the answers to these three questions, and—even if nothing else changes—you'll suddenly have a much more compelling story.

August 17, 2025

Does This Support the Life I'm Trying to Create?

My wife has this Post-It on her desk, and I think about it all the time—every time I'm trying to figure out where to spend my time and effort. "Does this support the life I'm trying to create?"

I like it because it raises an even more interesting question (related to a previous post)—what is the life I'm trying to create?—and it doesn't leave that question in the realm of pie-in-the-sky dreaming. It forces me to think about what I want and what steps I can take right now to get there.

And I'm thinking about it even more lately because of, well... lots of recent and ongoing changes. I don't know what all the future holds, but I love to imagine a future where my work is all steady* private editing clients (very flexible and fulfilling), I'm able to write at a steady* pace, and I'm—I dunno—GMing tabletop RPGs or writing Twine games or something and playing games with friends and the diaspora that will be my family.

* The word "steady" is doing a lot of work here. I'll take what I can get, so long as my stress remains manageable.

That sounds like a lot of stuff, now that I write it all out like that. But then, that's the other point of the question: to examine things one step at a time.

This is why I started the blog (and continue to figure out a posting cadence that works for me) and why I am open to private clients even while I have a long-term contract. My answers to this question have instigated other stuff behind the scenes too—some of which might even show up here one day.

Why am I talking about this? Well, mostly because I'm thinking about it a lot, but also because I suspect you can benefit from it as well. In my experience, that's usually how this works.

So, what is the life you're trying to create, and what steps are you taking to support that? (And is there anything you're doing that doesn't support it?) I'd love to hear about your own decisions and dreams.

August 3, 2025

What If You Don't Make It?

I saw this comic by Katie Shanahan the other day, and it's really stuck with me, so I want to share it.

See, I'm 47 years old and have been writing professionally for a couple of decades. I've published some stories and helped ship some games, and I'm super proud of all of that. But, you know, I started this blog with bigger dreams and excitement than has been borne out thus far.

But this comic helped remind me that I'm not done yet—not if I don't want to be.

And if there's one thing I've learned in 17.2 years of active social media, it's that I am basically never alone in my feelings. So, this is for you, too:

Will I make it? I don't know.

But what does "making it" even mean? I get to paid to write sometimes (even making the occasional royalties). I've designed and written for multiple highly rated games (even enabling a record-breaking crowdfunding campaign). I've raised over a dozen really excellent humans (possibly saving the lives of some). I've streamed games, speedrunned (speedran?), and managed several TTRPG campaigns.

So... maybe I have "made it"? That question is what I'm actively working on, and have been for decades, and will be for as long as I write: Why do I do this? What do I hope to achieve? How will I know when I achieved it?

The answer used to be "get published!" Which I did. And that's still something I'm aiming for, but I don't want it to be my definition of "making it." There's no sense trying to find my value in something that's out of my control.

And that's why Katie's comic really speaks to me. Maybe I've made it. Maybe I haven't. But it doesn't matter. I write because I enjoy writing. Nothing else.

Maybe I've made it when I'm enjoying making a thing. Everything else is icing.

July 20, 2025

Preaching Well

Last week, I talked about being "preachy" in fiction and why it's maybe not as bad as people think it is. In particular, there are lots of examples of fiction that are not only super popular but arguably so because of their message.

So, the problem is not messaging in fiction. Fiction is messaging, and (whether you are aware of it or not) all fiction is political. People generally don't have a problem with preaching in fiction unless the message is something they disagree with.

Like I've said before, you aren't writing for those people.

But you do want your message to be written well and received well by those who are open to it. Here are a few tips to help with that:

1) Portray All Sides with Empathy

A common problem in fiction is when one group of people are portrayed as intelligent and sympathetic while another comes across as cardboard cut-out villains.

Religion is a common victim of this. The atheist and non-Christian analogues in Chronicles of Narnia—the folks who don't believe Aslan is real or who work against him—are often insufferable. Edmund and Eustace, for example, are simply the worst characters (until they believe).

Secular sci-fi isn't much better. I've lost track of how many stories I've read in which the protagonists are open-minded and intelligent while the villains are pompous religious jerks.

Even if you don't agree with a character's point of view, they do. Nobody thinks of themselves as evil, and as the author, it is your job to figure out why not and portray that sympathetically.

2) Leave Your Message Open-Ended

When you think of your story's theme or message, is it a moral to be prescribed or a question to be explored? Life is nuance and uncertainty, but if your story has easy answers, it can ring false. Exploring that uncertainty, however, is what makes good fiction great.

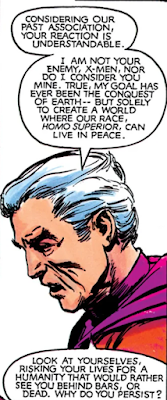

Take the X-Men. These stories explore themes of racial discrimination, and while there is a repeated moral (e.g., accept those different from you), there are also always difficult questions raised. The conflict between Professor X and Magneto is a prime example. Magneto believes that mutants are the next step in human evolution and should rule the world. Professor X, on the other hand, believes humans and mutants can co-exist as equals. The latter is obviously the stories' message, since Professor X is the "good guy," but he is frequently faced with challenges that throw that message into question. Can humans and mutants ever truly get along?

Their struggle is never-ending, and that's the point of phrasing your message as a question. The struggles we face are open-ended. If you paint your message as black and white, it will feel false to anyone who—like Magneto—has seen that the world isn't so amenable to pat answers.

3) Let the Reader Come to Their Own Conclusions

If you've ever tried to change someone's belief, you know it's practically impossible. A person can't be told what is true and simply believe it, not even if they are presented with irrefutable evidence. They will refute it! However, people can and do change their own beliefs by coming to their own conclusions over time.

Don't tell the reader what to think or believe, but show them different viewpoints. Explore different answers to very difficult questions. And then... do nothing. Let them think for themselves.

It's the most frustrating and rewarding part of being an author (or a parent, or a teacher, or a therapist, or...). As my mom tried to teach me my whole life, you have to let them be wrong.

The Bottom Line is Empathy

The gift of fiction—and a requirement to create it—is to be able to put ourselves in someone else's shoes, to see the world from another's perspective. Reading increases empathy. A reader without empathy will bounce of most stories altogether, and a writer who lacks it will struggle to connect with any reader unlike themselves.

So, say what you want to say. Explore difficult questions and even present your own answers through your characters. But be fair. Be open-minded. Be empathic.

You'll be surprised how many more people you can impact.

July 13, 2025

On "Preachy" Fiction

I think I learned a bad lesson when I was a brand new writer—or maybe it was a good lesson that I just took too far. The lesson was this: Don't use fiction to preach.

What people generally mean by that is they don't want authors to write fiction with the express goal of teaching a lesson. They want a good story. They don't want to be moralized to.

Or so they say...

But when the lesson is something the reader doesn't notice, it's not considered preachy at all. X-Men stories, for example, are hella preachy, but many fans either don't connect the themes of mutant discrimination to the real world or else identify with those themes in less controversial ways (e.g., some fans interpret X-Men's themes as discrimination against "misfits" or "outsiders," rather than racial prejudice).

And when the lesson is something the reader wants to hear, the audience often loves it! For example, the Chronicles of Narnia are a straight-up Christian allegory, beloved by Christians of all flavors. Andor is widely considered one of the best-written Star Wars stories to date, partially for being a straight-up anti-fascist manifesto.

It seems like it's not that people don't want messages in their fiction. It's that they don't want to be aware of messages they don't like. (You know, just like in real life.)

I started this post saying I learned a bad lesson. See, I spent a lot of my writing career trying to "say something without saying something"—trying to be subtle with my messages, trying not to piss anyone off or be accused of heavy-handed preaching. I ended up writing "fun" fiction but not necessarily the meaningful fiction I wanted to write.

My stories are fine, of course. Good, even. I've been published a few times. People have found meaning in my stories, and I'm thankful for that. Heck, I even have fans of stories that have never been published. But I was scared.

And I don't want to be.

And I don't need to be.

So, this is my encouragement to you: Write what you want to say. There will always be people who don't like what that is, and that's okay. You're not writing for them.

Will leaning into your message get you published and famous? Not by itself, no. It might even work against you at first as you figure out how to do it well. But it means that when someone does read your work, they are at least reading something that you want to say—and what you want to say matters.

So you do you, friends. Go ahead and...

July 6, 2025

Low on Creative Energy?

Sometimes, you're just doing so much creative stuff in a day or a week (or more!) that you don't have the creative resources you need to write something you might never be paid for.

And that's okay. Give yourself permission to not write for a bit...

...or to write something very short.